Submitted:

26 April 2024

Posted:

28 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- To inquire about students’ experiences with physical education during their school trajectory through the autobiographical analysis of their best and worst memories.

- -

- To find out the beliefs and previous concepts on Physical Education that students, future Primary teachers, bring with them.

- -

- To compare the students’ perceptions of the components of the Didactics of Physical Education before and after taking the course.

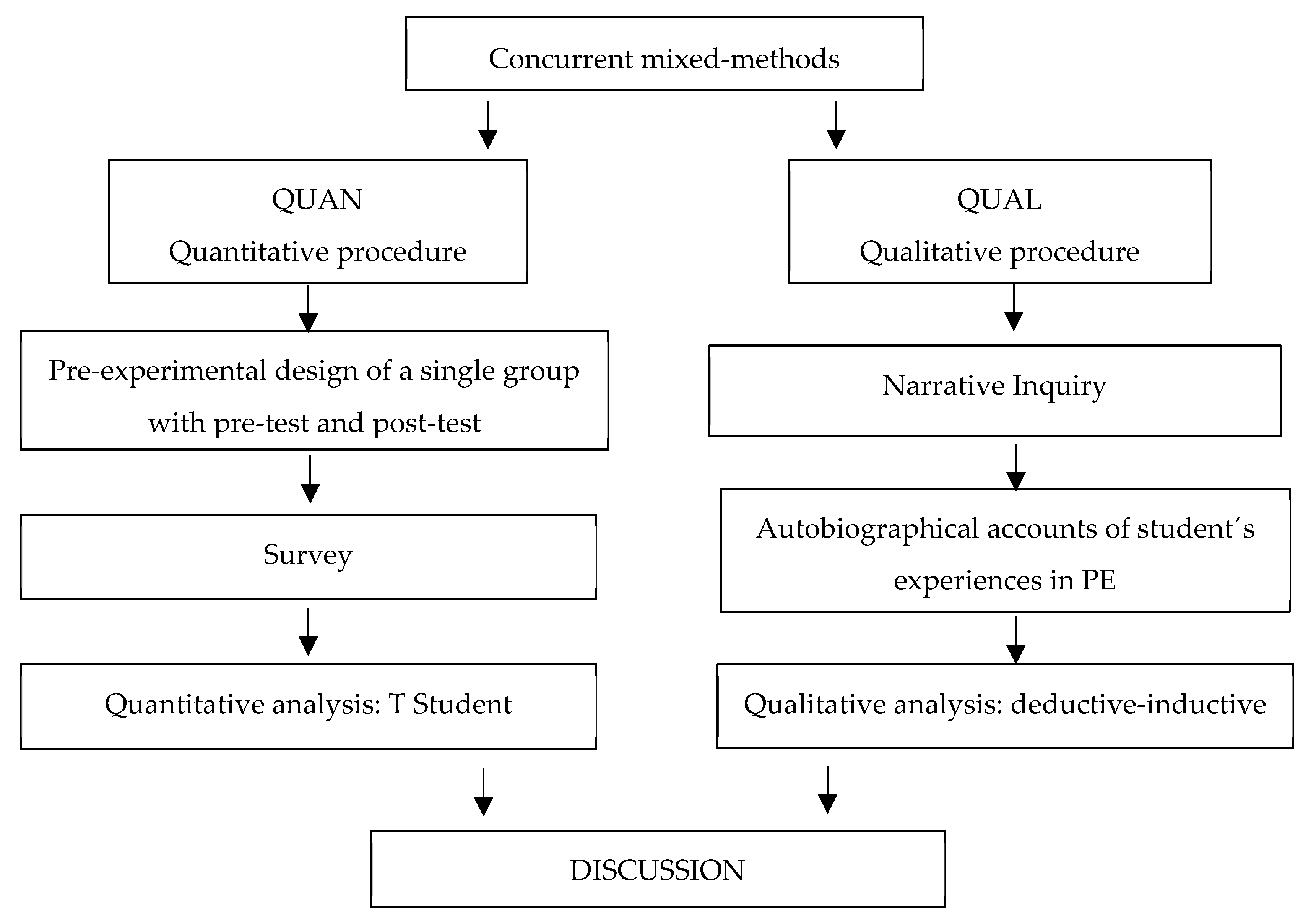

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Quantitative Procedure (QUAN)

2.2. Qualitative Procedure (QUAL)

2.3. Participants

2.4. Data Collection and Information Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Beliefs and Previous Concepts about Physical Education

3.2. Characteristics and Purpose of Physical Education Didactics

3.3. Contributions of “Didactics of Physical Education” to Teaching Professional Competencies:

3.4. Positive and Negative Memories Regarding Physical Education

“I have very fond memories; I couldn’t highlight any in particular. I remember having a great time in almost every session, mostly when we played dodgeball; I loved that game. Also, I remember that during Halloween, the Physical Education department organized outdoor games that were very entertaining and enjoyed by everyone” (S10).

“How much fun I had during the sessions with my classmates, especially in the Primary Education stage; I have better memories because the teacher organized very fun games...” (S12).

“The best stage in Physical Education for me was in Primary school. We played entertaining and fun games while learning at the same time” (S27).

“I also liked the atmosphere in the classroom, much more relaxed than in other subjects, where we could socialize with all classmates and get to know each other better” (S25).

“A different class, transcending the limits of the classroom and its classic rules, conducted standing, in motion, dynamically (...) with the playful touch they almost always had” (S38).

“The best memories of Physical Education are the moments and anecdotes I shared with my classmates; it was the time to disconnect from other subjects” (S39).

“... thanks also to the teacher we had because we learned new things and had fun playing” (S5).

“The innovations by the teachers, taking advantage of seasons like autumn to do what we called ‘The chestnut games’” (S6).

“In primary school (...) the teacher tried to make us learn by playing with everyone” (S15).

“... we had an excellent teacher with whom we played a lot of games...” (S23).

“The best experiences in PE that I remember are related to the teacher we had in the third cycle of Primary school. His concern for us to learn and have a good time in class was evident” (S31).

“The endurance tests, speed, strength, etc. Since we were only valued based on the results we achieved without taking into account our effort and abilities” (S7).

“When some teachers made us do somersaults as an exam in front of the whole class, without practicing much beforehand, as if everyone should know how to do them. And until you did something, you were there in front of everyone” (S9).

“The worst memory I have of Physical Education could be the physical endurance tests, like the Cooper test, which I never saw any usefulness in since many people struggled with it” (S25).

“When activities were carried out that did not adapt to each person’s abilities” (S62).

“... comparisons between classmates, competitiveness, or activities related to performance in physical tests” (S8).

“The atmosphere of competitiveness that was created with my classmates, the low self-esteem it generated in me for not being ‘good’ in the subject, always being the last person chosen for teams, always at a lower competitive level than my class” (S35).

“... we had a teacher who conducted classes in the traditional method, focusing on high-demand exercises, and if you didn’t reach the expected level, it influenced our grade negatively” (S27).

“... my worst memories in Physical Education are related to the teacher who taught the subject in the second cycle” (S31).

“My worst memories are with a teacher who barely got involved in teaching practice...” (S40).

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Loughran, J. J.; Hamilton, M. L.; LaBoskey, V. K.; & Russell, T. L. (Eds.). International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices, 2007, Vol. 12. Springer.

- Pérez, S.; Aburto, R.; Poblete, F.; Aguayo, O. The school as a space to become a teacher: experiencies of Physical Education teachers in training. Retos, 2022, 43, 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korthagen, F.A.J.; Nuijten, E.E. Core reflection: Nurturing the human potential in students and teachers. In International Handbook of Holistic Education, J.P. Miller, K. Nigh, M.J. Binder, B. Novak, & S. Crowell, New York/London: Routledge, 2022; pp. 89-99.

- Coe, R.; Aloisi, C.; Higgins, S.; & Elliot Major, L. What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research. Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring. Durham University, 2014. What-Makes-Great-Teaching-REPORT.pdf (suttontrust.com).

- Twomey-Fosnot, C.; Stewart-Perry, R. , Constructivism: A Psychological Theory of Learning, in Constructivism: theory, perspectives, and practice (2nd ed), C. Twomey Fosnot, editor. Teachers College Press. 2005.

- Lortie, D. C. Schoolteacher: A Sociological Study. Chicago, IL, University of Chicago Press, 1975.

- Wrench, A.; Garrett, R. Identity work: stories told in learning to teach physical education. In Sport, Education and Society, 2012, 17(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Goodson, I. F. Hacia un desarrollo de las historias personales y profesionales de los docentes. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 2003, 8(19), 733–758.

- Bolívar, A. Las historias de vida del profesorado. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 2014, 19(62), 711–734. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1405-66662014000300004.

- Elías, M. La construcción de identidad profesional en los estudiantes del profesorado de Educación Primaria. Profesorado. Revista de Currículum y Formación de Profesorado, 2016, 20(3), 335-365. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/567/56749100012.pdf.

- González-Calvo, G.; Arias-Carballal, M. A. Teacher´s personal-emotional identity and its reflection upon the development of his professional identity. The Qualitative Report, 2017, 22(6), 1693-1709. [CrossRef]

- Hortigüela, D.; & Hernando, A. “Dedícate a otra cosa”: estudio autobiográfico del desarrollo profesional de un docente universitario de Educación Física. Qualitative Research in Education, 2017, 6(2), 149-178. [CrossRef]

- Abreu, S. M. B. de; Nóbrega-Therrien, S. M.; & Silva, S. P. Experiência com narrativas autobiográficas na (auto)formação para a pesquisa de licenciandos em educação física. Revista Educaçao e Formaçao, 2017, 2(5), 183–194. [CrossRef]

- O’Bryant, Camille P.; Mary O’Sullivan; & Jeanne Raudensky. Socialization of Prospective Physical Education Teachers: The Story of New Blood. Sport, Education and Society, 2000, 5(2), 177–93. [CrossRef]

- Arnon, S.; Reichel, N. Who is the ideal teacher? Am I? Similarity and difference in perception of students of education regarding the qualities of a good teacher and of their own qualities as teachers. Teachers and Teaching: theory and practice, 2007, 13(5), 441-464. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, P. K.; Delli, L. A. M.; Edwards, M. N. The good teacher and the good teaching: comparing beliefs of second grade students, preservice teachers, and inservice teachers. The Journal of Experimental Education, 2004, 72(2), 69-92. [CrossRef]

- Harford, J.; Gray, P. Emerging from somewhere: Students teachers, professional identity and the future of teacher education research. In Overcoming fragmentation in teacher education policy and practice, B. Hudson, Ed., Cambridge University Press, 2017, pp. 27-48.

- Carter, A. Carter review of initial teacher training (ITT). London: DfE, 2015. Carter_Review.pdf (publish-ing.service.gov.uk).

- Gomez-Zwiep, S. Elementary teachers’ understanding of students’ science misconceptions: Implications for practice and teacher education. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 2008, 19 (5), 437–454. [CrossRef]

- Kambouri, M. Investigating early years teachers’ understanding and response to children’s preconceptions. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 2016, 24(6), 907–927. [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J. A.; Lederman, N. G. Science teachers’ diagnosis and understanding of students’preconceptions. Science Education, 2003, 87(6), 849–867. [CrossRef]

- Lerum, Øystein; Bartholomew, John; McKay, Heather; Resaland, Geir Kåre; Tjomsland, Hege E.; Anderssen, Sigmund Alfred; Leirhaug, Petter Erik; Moe, Vegard Fusche. Active Smarter Teachers: Primary School Teachers’ Perceptions and Maintenance of a School-Based Physical Activity Intervention. Translational Journal of the ACSM, 2019, 4(17), p 141-147. [CrossRef]

- Österling, L.; Christiansen, I. Whom do they become? A systematic review of research on the impact of practicum on student teachers’ affect, beliefs, and identities. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 2022, 17(4). [CrossRef]

- Grub, A. S.; Biermann, A.; Brünken, R. Process-based measurement of professional vision of (prospective) teachers in the field of classroom management. A systematic review. Journal for educational research online, 2020, 12(3), 75-102. [CrossRef]

- Chróinín, D. N.; O’Sullivan, M. Elementary Classroom Teachers’ Beliefs Across Time: Learning to Teach Physical Education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 2016, 35(2), 97–106. [CrossRef]

- Matanin, M.; Collier, C. Matanin, M.; Collier, C. Longitudinal Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Beliefs about Teaching Physical Education. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 2003, 22(2), 153–168. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, S.; O’Donovan, T. M. Pre-service physical education teachers’ beliefs about competition in physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 2013, 18(6), 767–787. [CrossRef]

- Del Valle, S.; De la Vega; R.; Martínez-Almira, M. M. Primary and Secundary School Physical Education Teacher´s Beliefs. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de La Actividad Física y Del Deporte, 2015, 15(59), 506–526.

- Gutiérrez Sánchez, M.; Romero Sánchez, E.; Izquierdo Rus, T. Creencias del profesorado de Educación Física en Educación Primaria sobre la educación en valores. Educatio Siglo XXI: Revista de La Facultad de Educación, 2019, 37(3), 83–110. [CrossRef]

- González-Calvo, G; Gerdin, G.; Philpot, R.; Hortigüela-Alcalá, D. Wanting to become PE teachers in Spain: connections between previous experiences and particular beliefs about school Physical Education and the development of professional teacher identities. Sport, Education and Society, 2021, 26(8), 931–944. [CrossRef]

- Latorre Medina, Mª. J.; Pérez García, Mª. P.; Blanco Encomienda, F. J. Análisis de las creencias que sobre la enseñanza práctica poseen los futuros maestros especialistas en Educación Primaria y en Educación Física. Un estudio comparado. REIFOP, 2009, 12 (1), 85-105.

- Rivera García, E.; Trigueros Cervantes, C.; Doña, A. M. The Big Bang Theory o las reflexiones finales que inician el cambio. Revisando las creencias de los docentes para construir una didáctica para la Educación Física Escolar (The Big Bang Theory or the final reflections that trigger change. Reviewing teacher. Retos, 2020, 37, 652–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Álvarez, J. L.; Velázquez-Buendía, R.; Martínez, M. E.; Díaz del Cueto, M. Creencias y perspectivas docentes sobre objetivos curriculares y factores determinantes de actividad física. Revista Internacional de Medicina y Ciencias de La Actividad Física y El Deporte, 2010, 10(38), 336–355. http://cdeporte.rediris.es/revista/revista38/ artcrencias160b.htm.

- Alonso, M. C.; Gómez-Alonso, M. T.; Pérez-Pueyo, Á.; Gutiérrez-García, C. Errores en la intervención didáctica de profesores de Educación Física en formación: perspectiva de sus compañeros en sesiones simuladas. Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 2016, 29, 229-235. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=345743464044.

- Eirín-Nemiña, R. Reconstruyendo la materia de Didáctica de la Educación Física desde la perspectiva autobiográfica del alumnado (Reconstructing the subject of Didactics of Physical Education from students’ autobiographical perspective). Retos, 2020, 37, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, R.; Fernández, C.; Baptista, P. Metodología de la investigación, 6ª edición, McGrawHill Education, México. 2014.

- Hernández-Sampieri, R. & Mendoza, C. (2018). Metodología de la investigación. Las rutas cuantitativa, cualitativa y mixta. México, Mc Graw Hill Education, 2018.

- Onwuegbuzie, A. J.; Johnson, R. B.; & Collins, K. M. Call for mixed analysis: A philosophical framework for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. International Journal of Multiple Research Approaches, 2009, 3(2), 114–139. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. Mapping the Field of Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 2009, 3 (2), 95-108.

- Teddlie, C.; & Tashakkori, A. Foundations of Mixed Methods Research: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches in the Social and Behavioral Sciences. Sage, London, 2009.

- Torrado, M. Estudios tipo encuesta. In Metodología de la investigación educativa, R. Bisquerra, Coord. Ed. La Muralla, Madrid, 2004, pp. 130-147.

- McMillan, J.H.; Schumacher, S. Investigación educativa, 5ª edición. Ed. Pearson. 2005.

- Fowler, F.J.; Cosenza, C. Writing Effective Questions. In International Handbook of Survey Methodology, E.D. Leeuw, J.J. Hox, and D.A. Dillman; Taylor and Francis Group, New York. 2008, pp. 136-160.

- Sabariego, M.; Massot, I.; & Dorio, I. Métodos de investigación cualitativa. In R. Bisquerra (Coord.). Metodología de la investigación educativa, 285-320. La Muralla, 2016.

- Resolución del 19 de febrero de 2015, de la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela, por la que se publica el plan de estudios de Graduado en Maestro de Educación Primaria. Boletín Oficial del Estado, nº 70, 25316-25320. https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2015-3086.

- Moreno, J. A. & Hellín, M. G. El interés del alumnado de Educación Secundaria Obligatoria hacia la Educación Física. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 2007, 9(2), 1-20.

- Valencia-Peris, A. & Lizandra, J. Cambios en la representación social de la educación física en la formación inicial del profesorado. Retos. Nuevas Tendencias en Educación Física, Deporte y Recreación, 2018, 34, 230–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina Soria, M.; Pascual Arias, C. & López Pastor, V.M. El uso de sistemas de evaluación formativa y compartida en las aulas de educación física en Educación Primaria. Educación Física y Deporte, 2020; 39, 47–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monforte, J. & Pérez-Samaniego, V. O medo em Educaçao Física: uma história reconhecível. Movimento. Revista de Educaçao Física da UFRGS,. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, J. E.; Quinn, F.; Miller, J. A. Teacher Biography: SOLO Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Reflections of their Experiences in Physical Education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 2020; 45, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Key concepts | Pre-test (mean1) |

Post-test (mean1) |

Student´s test T value |

Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitiveness | 3.51 | 2.88 | 4,159 | 0.001** |

| Effort / Endeavour | 3.97 | 4.19 | -1,785 | 0.040* |

| Physical fatigue | 3.29 | 2.83 | 2,812 | 0.003** |

| Participation | 4.19 | 4.80 | -5,046 | 0.001** |

| Fun | 3.98 | 4.68 | -6,093 | 0.001** |

| Socializing | 4.03 | 4.69 | -5,403 | 0.001** |

| Learning | 3.69 | 4.78 | -10,791 | 0.001** |

| Play | 4.08 | 4.68 | -5,612 | 0.001** |

| Characteristics | Pre-test (mean1) |

Post-test (mean1) |

T value | Sig. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| It is a means of social interaction which facilitates participation with others | 4.51 | 4.76 | 3.089 | 0.002** |

| It is a way of learning while having fun, it has a playful and motivating component for student participation | 4.61 | 4.90 | 3.585 | 0.001** |

| It represents a challenge, understood as something to overcome within learners’ possibilities | 3.69 | 4.22 | 3.881 | 0.001** |

| It favours motor skills, in terms of individual improvement in accordance with his/her own possibilities | 4.28 | 4.53 | 2.264 | 0.014* |

| It is socially relevant learning | 4.07 | 4.59 | 4.186 | 0.001** |

| It is relevant learning in cognitive terms | 4.10 | 4.42 | 3.021 | 0.002** |

| It facilitates moments of pleasure and enjoyment | 4.44 | 4.64 | 2.188 | 0.016* |

| It favours the development of decision-making skills | 3.97 | 4.59 | 5.097 | 0.001** |

| It favours the development of autonomy in students | 4.24 | 4.59 | 3.708 | 0.001** |

| It allows students to reflect on the meaning of their experiences in the subject | 4.16 | 4.53 | 2.692 | 0.005** |

| Competences | Mean1 | Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|

| To know the curricular area of Physical Education in Primary Education | 4.27 | 0.611 |

| Acquire teaching-learning procedures | 4.53 | 0.626 |

| To facilitate disciplinary interrelation between different curricular areas of Primary Education | 3.97 | 0.742 |

| Encourage the design and regulation of teaching-learning environments in contexts of diversity | 4.22 | 0.750 |

| Stimulate gender equality, equity and respect of human rights, which make up the values of citizenship education | 4.22 | 0.767 |

| Improve the coexistence both inside and outside the classroom, paying attention to the peaceful resolution of conflicts | 4.46 | 0.597 |

| Stimulate and value effort, perseverance and personal discipline in students | 4.53 | 0.504 |

| To favour the acquisition of habits and skills for autonomous and cooperative learning among students | 4.63 | 0.488 |

| To help reflect on classroom practices inside the classroom in order to innovate and improve teaching work | 4.56 | 0.565 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).