Submitted:

28 April 2024

Posted:

30 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Gem/Doce Instillation

2.3. Surveillance

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Patient Demographics

3.2. Survival Outcomes

Test statistic = 1.518, p=0.129

3.3. Progression and Survival

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- European Cancer Information System. https://ecis.jrc.ec.europa.eu/explorer.php (accessed 2023-05-30).

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R. L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71 (3), 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Burger, M.; Catto, J. W. F.; Dalbagni, G.; Grossman, H. B.; Herr, H.; Karakiewicz, P.; Kassouf, W.; Kiemeney, L. A.; La Vecchia, C.; Shariat, S.; et al. Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Urothelial Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol 2013, 63 (2), 234–241. [CrossRef]

- Semeniuk-Wojtaś, A.; Poddębniak-Strama, K.; Modzelewska, M.; Baryła, M.; Dziąg-Dudek, E.; Syryło, T.; Górnicka, B.; Jakieła, A.; Stec, R. Tumour Microenvironment as a Predictive Factor for Immunotherapy in Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother 2023, 72 (7), 1971–1989. [CrossRef]

- Hurst, C. D.; Knowles, M. A. Mutational Landscape of Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2022, 40 (7), 295–303. [CrossRef]

- Flaig, T. W.; Spiess, P. E.; Agarwal, N.; Bangs, R.; Boorjian, S. A.; Buyyounouski, M. K.; Chang, S.; Downs, T. M.; Efstathiou, J. A.; Friedlander, T.; et al. Bladder Cancer, Version 3.2020, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 2020, 18 (3), 329–354. [CrossRef]

- Magers, M. J.; Lopez-Beltran, A.; Montironi, R.; Williamson, S. R.; Kaimakliotis, H. Z.; Cheng, L. Staging of Bladder Cancer. Histopathology 2019, 74 (1), 112–134. [CrossRef]

- Minoli, M.; Kiener, M.; Thalmann, G. N.; Kruithof-de Julio, M.; Seiler, R. Evolution of Urothelial Bladder Cancer in the Context of Molecular Classifications. IJMS 2020, 21 (16), 5670. [CrossRef]

- Alfred Witjes, J.; Max Bruins, H.; Carrión, A.; Cathomas, R.; Compérat, E.; Efstathiou, J. A.; Fietkau, R.; Gakis, G.; Lorch, A.; Martini, A.; et al. European Association of Urology Guidelines on Muscle-Invasive and Metastatic Bladder Cancer: Summary of the 2023 Guidelines. European Urology 2024, 85 (1), 17–31. [CrossRef]

- Babjuk, M.; Böhle, A.; Burger, M.; Capoun, O.; Cohen, D.; Compérat, E. M.; Hernández, V.; Kaasinen, E.; Palou, J.; Rouprêt, M.; et al. EAU Guidelines on Non-Muscle-Invasive Urothelial Carcinoma of the Bladder: Update 2016. Eur Urol 2017, 71 (3), 447–461. [CrossRef]

- David, K. A.; Mallin, K.; Milowsky, M. I.; Ritchey, J.; Carroll, P. R.; Nanus, D. M. Surveillance of Urothelial Carcinoma: Stage and Grade Migration, 1993-2005 and Survival Trends, 1993-2000. Cancer 2009, 115 (7), 1435–1447. [CrossRef]

- Hall, M. C.; Chang, S. S.; Dalbagni, G.; Pruthi, R. S.; Seigne, J. D.; Skinner, E. C.; Wolf, J. S.; Schellhammer, P. F. Guideline for the Management of Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer (Stages Ta, T1, and Tis): 2007 Update. J Urol 2007, 178 (6), 2314–2330. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S. S.; Boorjian, S. A.; Chou, R.; Clark, P. E.; Daneshmand, S.; Konety, B. R.; Pruthi, R.; Quale, D. Z.; Ritch, C. R.; Seigne, J. D.; et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer: AUA/SUO Guideline. J Urol 2016, 196 (4), 1021–1029. [CrossRef]

- Sylvester, R. J.; Rodríguez, O.; Hernández, V.; Turturica, D.; Bauerová, L.; Bruins, H. M.; Bründl, J.; van der Kwast, T. H.; Brisuda, A.; Rubio-Briones, J.; et al. European Association of Urology (EAU) Prognostic Factor Risk Groups for Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer (NMIBC) Incorporating the WHO 2004/2016 and WHO 1973 Classification Systems for Grade: An Update from the EAU NMIBC Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol 2021, 79 (4), 480–488. [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, A.; Gunjur, A.; Weickhardt, A.; Papa, N.; Bolton, D.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Perera, M. Adjuvant Therapies for Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Advances during BCG Shortage. World J Urol 2022, 40 (5), 1111–1124. [CrossRef]

- Zlotta, A. R.; Fleshner, N. E.; Jewett, M. A. The Management of BCG Failure in Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: An Update. Can Urol Assoc J 2009, 3 (6 Suppl 4), S199-205. [CrossRef]

- Sfakianos, J. P.; Kim, P. H.; Hakimi, A. A.; Herr, H. W. The Effect of Restaging Transurethral Resection on Recurrence and Progression Rates in Patients with Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer Treated with Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin. J Urol 2014, 191 (2), 341–345. [CrossRef]

- Kamat, A. M.; Colombel, M.; Sundi, D.; Lamm, D.; Boehle, A.; Brausi, M.; Buckley, R.; Persad, R.; Palou, J.; Soloway, M.; Witjes, J. A. BCG-Unresponsive Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Recommendations from the IBCG. Nat Rev Urol 2017, 14 (4), 244–255. [CrossRef]

- Oddens, J.; Brausi, M.; Sylvester, R.; Bono, A.; Van De Beek, C.; Van Andel, G.; Gontero, P.; Hoeltl, W.; Turkeri, L.; Marreaud, S.; et al. Final Results of an EORTC-GU Cancers Group Randomized Study of Maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guérin in Intermediate- and High-Risk Ta, T1 Papillary Carcinoma of the Urinary Bladder: One-Third Dose Versus Full Dose and 1 Year Versus 3 Years of Maintenance. European Urology 2013, 63 (3), 462–472. [CrossRef]

- Lamm, D. L.; Blumenstein, B. A.; Crissman, J. D.; Montie, J. E.; Gottesman, J. E.; Lowe, B. A.; Sarosdy, M. F.; Bohl, R. D.; Grossman, H. B.; Beck, T. M.; et al. Maintenance Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Immunotherapy for Recurrent TA, T1 and Carcinoma in Situ Transitional Cell Carcinoma of the Bladder: A Randomized Southwest Oncology Group Study. J Urol 2000, 163 (4), 1124–1129.

- Askeland, E. J.; Newton, M. R.; O’Donnell, M. A.; Luo, Y. Bladder Cancer Immunotherapy: BCG and Beyond. Advances in Urology 2012, 2012, 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Yokomizo, A.; Kanimoto, Y.; Okamura, T.; Ozono, S.; Koga, H.; Iwamura, M.; Tanaka, H.; Takahashi, S.; Tsushima, T.; Kanayama, H.; et al. Randomized Controlled Study of the Efficacy, Safety and Quality of Life with Low Dose Bacillus Calmette-Guérin Instillation Therapy for Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. Journal of Urology 2016, 195 (1), 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Rezaee, M. E.; Ismail, A. A. O.; Okorie, C. L.; Seigne, J. D.; Lynch, K. E.; Schroeck, F. R. Partial Versus Complete Bacillus Calmette-Guérin Intravesical Therapy and Bladder Cancer Outcomes in High-Risk Non-Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer: Is NIMBUS the Full Story? Eur Urol Open Sci 2021, 26, 35–43. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, M.; Chislett, B.; Perera, M.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Bolton, D.; Jack, G. Critical Shortage in BCG Immunotherapy: How Did We Get Here and Where Will It Take Us? Urol Oncol 2022, 40 (1), 1–3. [CrossRef]

- American Urological Association. https://www.auanet.org/bcg-shortage-notice (accessed 2023-05-21).

- Malmström, P. U.; Wijkström, H.; Lundholm, C.; Wester, K.; Busch, C.; Norlén, B. J. 5-Year Followup of a Randomized Prospective Study Comparing Mitomycin C and Bacillus Calmette-Guerin in Patients with Superficial Bladder Carcinoma. Swedish-Norwegian Bladder Cancer Study Group. J Urol 1999, 161 (4), 1124–1127.

- Steinberg, G.; Bahnson, R.; Brosman, S.; Middleton, R.; Wajsman, Z.; Wehle, M. Efficacy and Safety of Valrubicin for the Treatment of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Refractory Carcinoma in Situ of the Bladder. The Valrubicin Study Group. J Urol 2000, 163 (3), 761–767.

- Barlow, L. J.; McKiernan, J. M.; Benson, M. C. Long-Term Survival Outcomes with Intravesical Docetaxel for Recurrent Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer After Previous Bacillus Calmette-Guérin Therapy. Journal of Urology 2013, 189 (3), 834–839. [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. C.; Goldman, B.; Sakr, W. A.; Petrylak, D. P.; Lenz, H.-J.; Lee, C. T.; Wilson, S. S.; Benson, M.; Lerner, S. P.; Tangen, C. M.; et al. SWOG S0353: Phase II Trial of Intravesical Gemcitabine in Patients with Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer and Recurrence after 2 Prior Courses of Intravesical Bacillus Calmette-Guérin. Journal of Urology 2013, 190 (4), 1200–1204. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, R. L.; Thomas, L. J.; O’Donnell, M. A.; Nepple, K. G. Sequential Intravesical Gemcitabine and Docetaxel for the Salvage Treatment of Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. Bladder Cancer 2015, 1 (1), 65–72. [CrossRef]

- McElree, I. M.; Steinberg, R. L.; Martin, A. C.; Richards, J.; Mott, S. L.; Gellhaus, P. T.; Nepple, K. G.; O’Donnell, M. A.; Packiam, V. T. Sequential Intravesical Gemcitabine and Docetaxel for Bacillus Calmette-Guérin-Naïve High-Risk Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. J Urol 2022, 208 (3), 589–599. [CrossRef]

- McElree, I. M.; Steinberg, R. L.; Mott, S. L.; O’Donnell, M. A.; Packiam, V. T. Comparison of Sequential Intravesical Gemcitabine and Docetaxel vs Bacillus Calmette-Guérin for the Treatment of Patients With High-Risk Non–Muscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2023, 6 (2), e230849. [CrossRef]

- Milbar, N.; Kates, M.; Chappidi, M. R.; Pederzoli, F.; Yoshida, T.; Sankin, A.; Pierorazio, P. M.; Schoenberg, M. P.; Bivalacqua, T. J. Oncological Outcomes of Sequential Intravesical Gemcitabine and Docetaxel in Patients with Non-Muscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. Bladder Cancer 2017, 3 (4), 293–303. [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, R. L.; Thomas, L. J.; Brooks, N.; Mott, S. L.; Vitale, A.; Crump, T.; Rao, M. Y.; Daniels, M. J.; Wang, J.; Nagaraju, S.; et al. Multi-Institution Evaluation of Sequential Gemcitabine and Docetaxel as Rescue Therapy for Nonmuscle Invasive Bladder Cancer. J Urol 2020, 203 (5), 902–909. [CrossRef]

- Pareek, T.; Parmar, K.; Sharma, A. P.; Kumar, S. Quality of Life, Efficacy, and Safety of Sequential Intravesical Gemcitabine + Docetaxel versus BCG for Non-Muscle Invasive Urinary Bladder Cancer: A Pilot Study. Urol Int 2022, 106 (8), 784–790. [CrossRef]

- Daniels, M. J.; Barry, E.; Milbar, N.; Schoenberg, M.; Bivalacqua, T. J.; Sankin, A.; Kates, M. An Evaluation of Monthly Maintenance Therapy among Patients Receiving Intravesical Combination Gemcitabine/Docetaxel for Nonmuscle-Invasive Bladder Cancer. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2020, 38 (2), 40.e17-40.e24. [CrossRef]

- Kastelan, Z.; Lukac, J.; Derezić, D.; Pasini, J.; Kusić, Z.; Sosić, H.; Kastelan, M. Lymphocyte Subsets, Lymphocyte Reactivity to Mitogens, NK Cell Activity and Neutrophil and Monocyte Phagocytic Functions in Patients with Bladder Carcinoma. Anticancer Res 2003, 23 (6D), 5185–5189.

- Marchetti, A.; Wang, L.; Magar, R.; Barton Grossman, H.; Lamm, D. L.; Schellhammer, P. F.; Erwin-Toth, P. Management of Patients with Bacilli Calmette-Guérin-Refractory Carcinoma in Situ of the Urinary Bladder: Cost Implications of a Clinical Trial for Valrubicin. Clinical Therapeutics 2000, 22 (4), 422–438. [CrossRef]

- Chappidi, M. R.; Kates, M.; Stimson, C. J.; Johnson, M. H.; Pierorazio, P. M.; Bivalacqua, T. J. Causes, Timing, Hospital Costs and Perioperative Outcomes of Index vs Nonindex Hospital Readmissions after Radical Cystectomy: Implications for Regionalization of Care. Journal of Urology 2017, 197 (2), 296–301. [CrossRef]

| Valid N | Mean | Median | Minimum | Maximum | SD | |

| Age (yrs) | 52 | 69.27 | 68.20 | 44.70 | 93 | 11.45 |

| BMI | 52 | 27.55 | 26.78 | 19.15 | 41.97 | 5.09 |

| TURBT to 1st therapy (months) | 52 | 1.55 | 1.23 | 0.73 | 6.57 | 1.07 |

| SD – standard deviation; BMI – body mass index; TUR – transurethral resection of bladder cancer. | ||||||

| Sex | n | Percent | ||||

| M | 44 | 84.6 | ||||

| F | 8 | 15.4 | ||||

| Total | 52 | 100.0 | ||||

| M – male; F – female. | ||||||

| DM | n | Percent | ||||

| No | 38 | 73.1 | ||||

| Yes | 14 | 26.9 | ||||

| Total | 52 | 100.0 | ||||

| DM – diabetes mellitus. | ||||||

| LUTS | n | Percent | ||||

| No | 37 | 71.2 | ||||

| Yes | 15 | 28.8 | ||||

| Total | 52 | 100.0 | ||||

| LUTS – lower urinary tract symptoms. | ||||||

| Histopathology | n | Percent |

| T1HG | 25 | 48.1 |

| CIS | 10 | 19.2 |

| T1HG+CIS | 17 | 32.7 |

| Total | 52 | 100.0 |

| Histopathology | Relapse in total | Median time to relapse (months) |

| T1HG | 3 (12%) | 11 |

| CIS | 2 (20%) | 10.5 |

| T1HG+CIS | 5 (29.4%) | 8.8 |

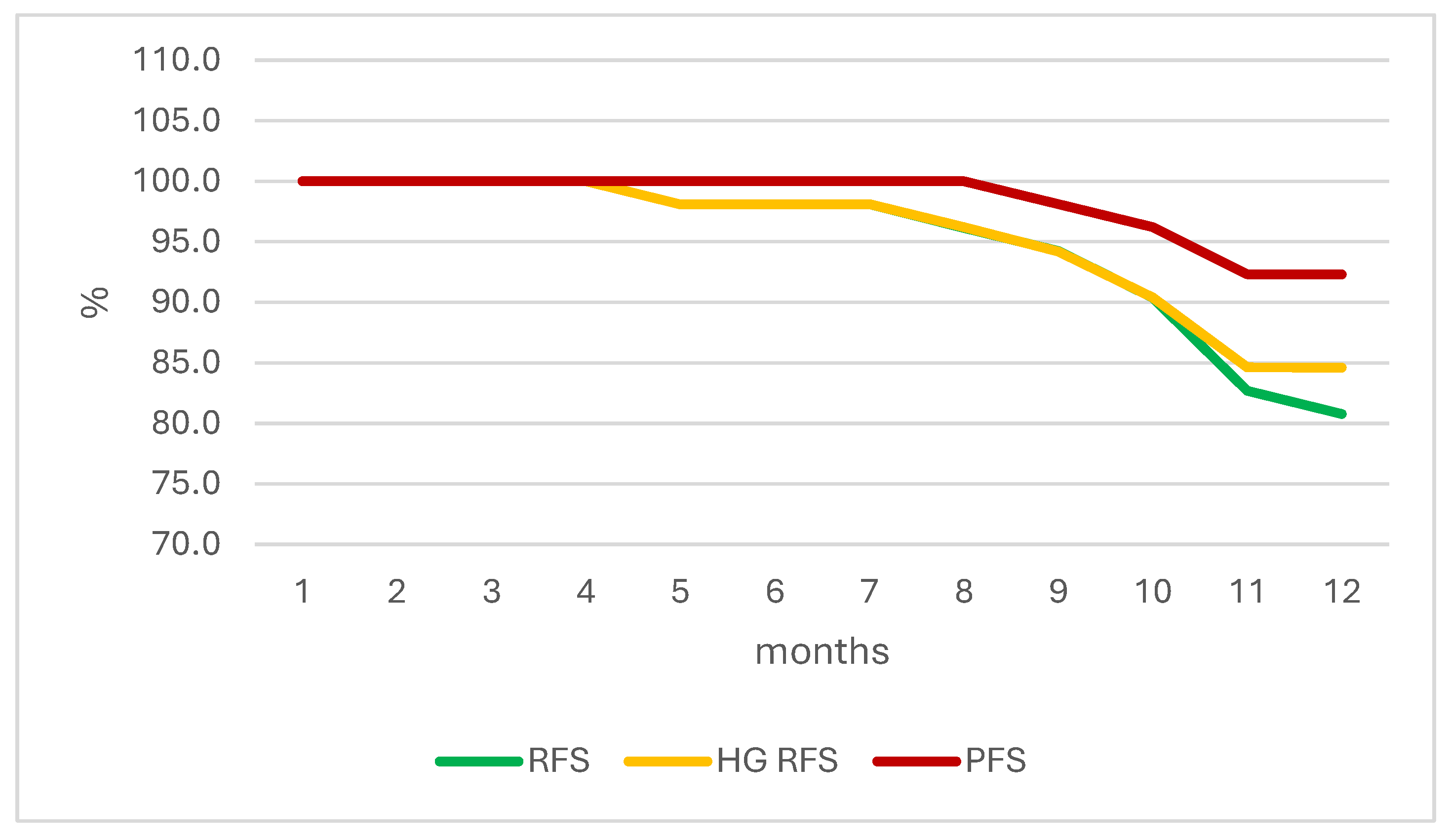

| Month of Therapy | RFS | HG RFS | PFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 2 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 3 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 4 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 5 | 98.1 | 98.1 | 100.0 |

| 6 | 98.1 | 98.1 | 100.0 |

| 7 | 98.1 | 98.1 | 100.0 |

| 8 | 96.2 | 96.2 | 100.0 |

| 9 | 94.2 | 94.2 | 98.1 |

| 10 | 90.4 | 90.4 | 96.2 |

| 11 | 82.7 | 84.6 | 92.3 |

| 12 | 80.8 | 84.6 | 92.3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).