Submitted:

29 April 2024

Posted:

30 April 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Study Population and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. The Final Questionnaire Consisted of the Following Sections

- Sociodemographic characteristics: age, gender, marital status, residence, academic year, socioeconomic status, and monthly income.

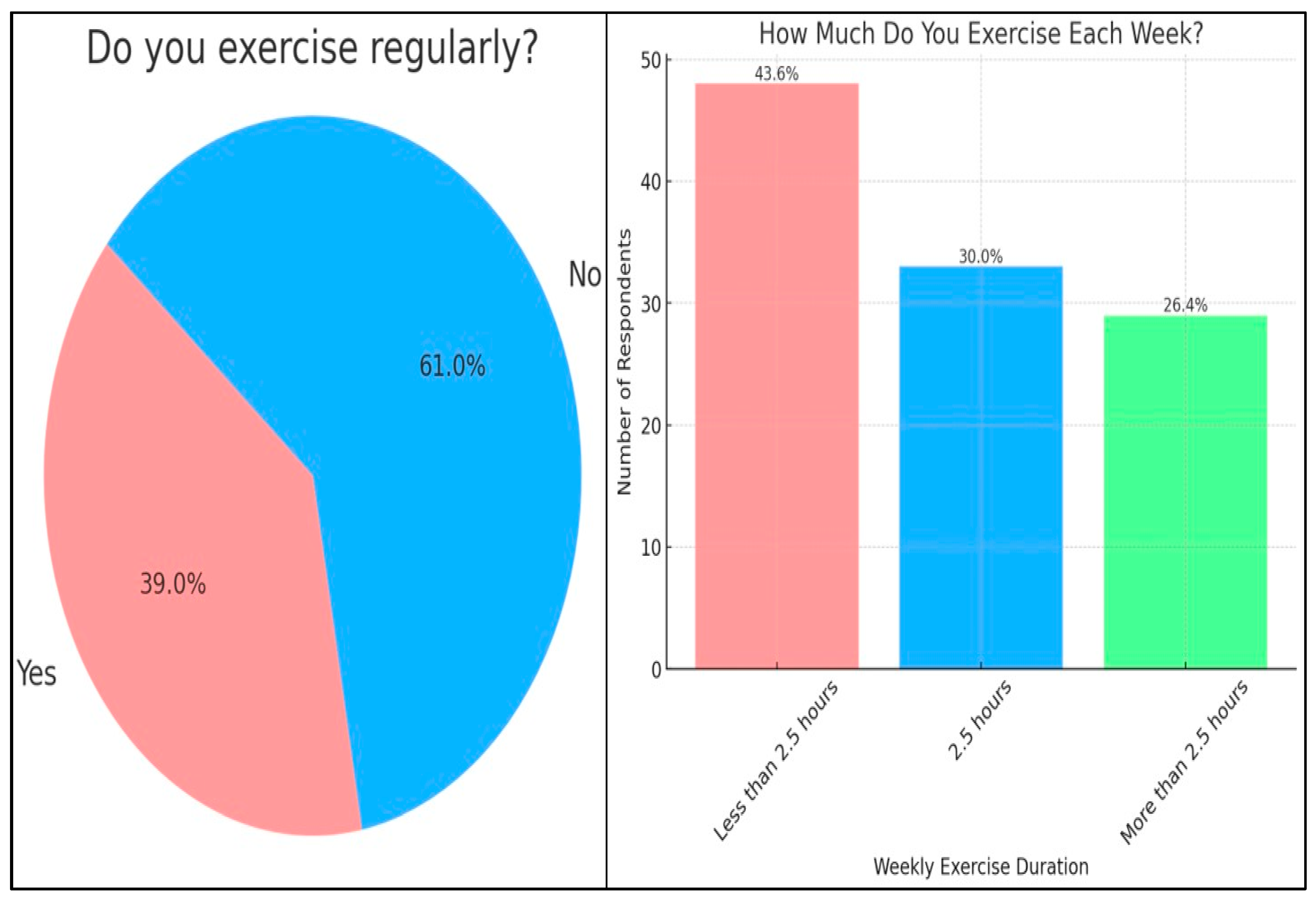

- Physical activity: regular exercise, type, and intensity of physical activity.

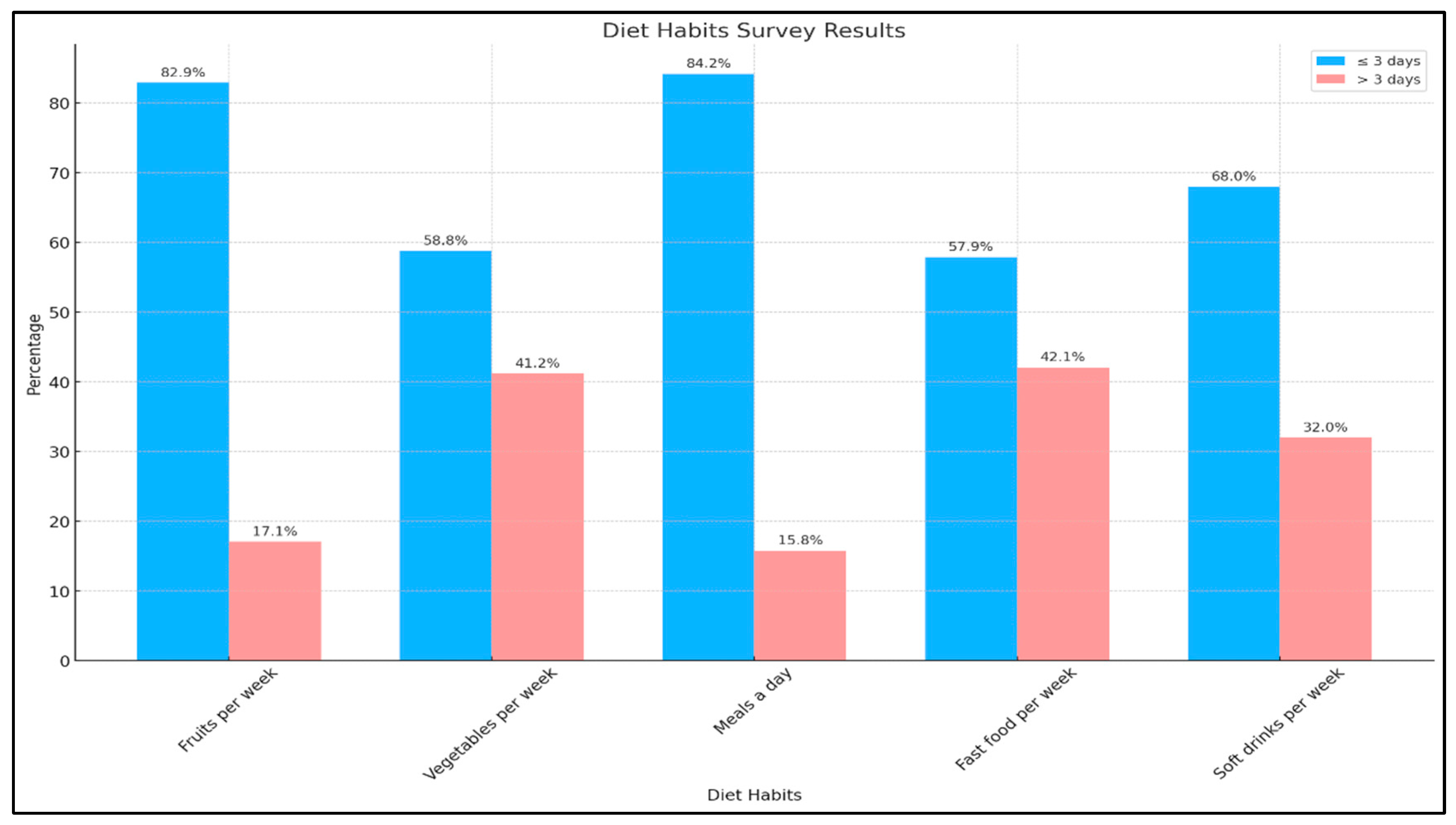

- Dietary habits: fruit and vegetable consumption, meal frequency, fast food intake, and sugar-sweetened beverage consumption.

- Comorbidities included hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia.

- Medication use: corticosteroids, beta blockers, antidiabetics, antipsychotics, and antidepressants.

- Family history: obesity, diabetes mellitus, and hypertension.

- Lifestyle factors: Smoking (cigarettes or shisha) and khat chewing.

- Academic Performance: Current Grade Point Average (GPA).

2.5. Data Management and Analysis

2.6. Ethical Considerations

3. Results:

| Factors | N | % | |

| Do you suffer from high blood pressure? |

Yes | 8 | 3.5% |

| No | 220 | 96.5% | |

| Do you suffer from diabetes? | Yes | 10 | 4.4% |

| No | 218 | 95.6% | |

|

Do you suffer from high blood fat levels? |

Yes | 22 | 9.6% |

| No | 206 | 90.4% | |

| Are you currently using a medication that belongs to any of the following drug classes? (Corticosteroids, B-blockers, antidiabetics, antipsychotics, antidepressants) | Yes | 14 | 6.1% |

| No | 214 | 93.9% | |

| Do you have a family (first-degree relative) history of obesity? | Yes | 72 | 31.6% |

| No | 156 | 68.4% | |

| Do you have a family history (diabetes) of first-degree relatives? | Yes | 96 | 42.1% |

| No | 132 | 57.9% | |

| Do you have a family history (blood pressure) of first-degree relatives? | Yes | 107 | 46.9% |

| No | 121 | 53.1% | |

| Do you smoke (cigarettes or shisha)? | Yes | 14 | 6.1% |

| No | 214 | 93.9% | |

| Do you chew (use) khat? | Yes | 3 | 1.3% |

| No | 225 | 98.7% | |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of interest

Appendix A. The Questionnaire

References

- Hruby, A.; Hu, F.B. The Epidemiology of Obesity: A Big Picture. PharmacoEconomics 2015, 33, 673–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laine, C.; Wee, C.C. Overweight and Obesity: Current Clinical Challenges. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 699–700, Erratum in: Ann Intern Med. 2023 Jul;176(7):1016. PMID: 36913692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wee, C.C. Using Body Mass Index to Identify and Address Obesity in Asian Americans: One Size Does Not Fit All. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1606–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obesity and overweight. Accessed: March 28, 2024. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Defining Adult Overweight & Obesity | Overweight & Obesity | CDC. Accessed: March 28, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/basics/adult-defining.html.

- Shah, N.S.; Luncheon, C.; Kandula, N.R.; Khan, S.S.; Pan, L.; Gillespie, C.; Loustalot, F.; Fang, J. Heterogeneity in Obesity Prevalence Among Asian American Adults. Ann. Intern. Med. 2022, 175, 1493–1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kriaucioniene, V.; Raskiliene, A.; Petrauskas, D.; Petkeviciene, J. Trends in Eating Habits and Body Weight Status, Perception Patterns and Management Practices among First-Year Students of Kaunas (Lithuania) Universities, 2000–2017. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Rethaiaa, A.S.; Fahmy, A.-E.A.; Al-Shwaiyat, N.M. Obesity and eating habits among college students in Saudi Arabia: a cross sectional study. Nutr. J. 2010, 9, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelan, S.M.; Burgess, D.J.; Puhl, R.; Dyrbye, L.N.; Dovidio, J.F.; Yeazel, M.; Ridgeway, J.L.; Nelson, D.; Perry, S.; Przedworski, J.M.; et al. The Adverse Effect of Weight Stigma on the Well-Being of Medical Students with Overweight or Obesity: Findings from a National Survey. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2015, 30, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harding, J.L.; Backholer, K.; Williams, E.D.; Peeters, A.; Cameron, A.J.; Hare, M.J.; E Shaw, J.; Magliano, D.J. Psychosocial stress is positively associated with body mass index gain over 5 years: Evidence from the longitudinal AusDiab study. Obesity 2013, 22, 277–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Li, H. Obesity: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutics. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 706978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čadek, M.; Täuber, S.; Lawrence, B.J.; Flint, S.W. Effect of health-care professionals’ weight status on patient satisfaction and recalled advice: a prospective cohort study. EClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamseh, M.E.; Emami, Z.; Iranpour, A.; Mahmoodian, R.; Amouei, E.; Tizmaghz, A.; Moradi, Y.; Baradaran, H.R. Attitude and Belief of Healthcare Professionals Towards Effective Obesity Care and Perception of Barriers; An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 26, 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peltzer, K.; Pengpid, S.; Samuels, T.A.; Özcan, N.K.; Mantilla, C.; Rahamefy, O.H.; Wong, M.L.; Gasparishvili, A. Prevalence of Overweight/Obesity and Its Associated Factors among University Students from 22 Countries. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2014, 11, 7425–7441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Nakeeb, Y.; Lyons, M.; Collins, P.; Al-Nuaim, A.; Al-Hazzaa, H.; Duncan, M.J.; Nevill, A. Obesity, Physical Activity and Sedentary Behavior Amongst British and Saudi Youth: A Cross-Cultural Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2012, 9, 1490–1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musaiger, A.O.; Al-Kandari, F.I.; Al-Mannai, M.; Al-Faraj, A.M.; Bouriki, F.A.; Shehab, F.S.; Al-Dabous, L.A.; Al-Qalaf, W.B. Perceived barriers to weight maintenance among university students in Kuwait: the role of gender and obesity. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 2014, 19, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haneef, S.; Almuammar, S. Prevalence and Associations of Night Eating Syndrome Among Medical Students in Saudi Arabia. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2024, ume 17, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, S.H.; Malik, A.A.; Bashawri, J.; Shaheen, S.A.; Shaheen, M.M.; Alsaib, A.A.; Mubarak, M.A.; Adam, Y.S.; Abdulwassi, H.K. Health-promoting lifestyle profile and associated factors among medical students in a Saudi university. SAGE Open Med. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad A, Elbadawi NE, Osman MS, Elmandi EM: The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Obesity among Medical Students at Shaqra University, Saudi Arabia. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2020, 10:903+.

- Younis, J.; Jiang, H.; Fan, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Jebril, M.; Ma, M.; Ma, L.; Ma, M.; Hui, Z. Prevalence of overweight, obesity, and associated factors among healthcare workers in the Gaza Strip, Palestine: A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Heal. 2023, 11, 1129797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oo, A.M.; Al-Abed, A.-A.A.A.; MarLwin, O.; Kanneppady, S.S.; Kanneppady, S.K. PREVALENCE OF OBESITY AND ITS ASSOCIATED RISK FACTORS AMONG POST- BASIC RENAL CARE NURSING STUDENTS. Malays. J. Public Heal. Med. 2019, 19, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamada, T.; Kimura-Koyanagi, M.; Sakaguchi, K.; Ogawa, W.; Tamori, Y. Obesity and risk for its comorbidities diabetes, hypertension, and dyslipidemia in Japanese individuals aged 65 years. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos-Arellano, L.E.; Matia-Garcia, I.; Marino-Ortega, L.A.; Castro-Alarcón, N.; Muñoz-Valle, J.F.; Salgado-Goytia, L.; Salgado-Bernabé, A.B.; Parra-Rojas, I. Obesity, dyslipidemia, and high blood pressure are associated with cardiovascular risk, determined using high-sensitivity C-reactive protein concentration, in young adults. J. Int. Med Res. 2020, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell-Wiley, T.M.; Poirier, P.; Burke, L.E.; Després, J.-P.; Gordon-Larsen, P.; Lavie, C.J.; Lear, S.A.; Ndumele, C.E.; Neeland, I.J.; Sanders, P.; et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation 2021, 143, e984–e1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, S.; Raiber, L.; Serodio, K.J.; Lee, J.; Christensen, R.A. Medications that cause weight gain and alternatives in Canada: a narrative review. Diabetes, Metab Syndr Obes. 2018; 11, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayabandara, M.; Hanwella, R.; Ratnatunage, S.; Seneviratne, S.; Suraweera, C.; de Silva, V. Antipsychotic-associated weight gain: management strategies and impact on treatment adherence. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. Treat. 2017, ume 13, 2231–2241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tirthani E, Said MS, Rehman A: Genetics and Obesity. 2024.

- Albuquerque, D.; Nóbrega, C.; Manco, L.; Padez, C. The contribution of genetics and environment to obesity. Br. Med Bull. 2017, 123, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarwer, D.B.; Polonsky, H.M. The Psychosocial Burden of Obesity. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2016, 45, 677–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- K, I.J.; Asharaf, H.; Thimothy, G.; George, S.; Jose, J.; Paily, R.; Josey, J.; Sajna, S.; Radhakrishnan, R. Psychological impact of obesity: A comprehensive analysis of health-related quality of life and weight-related symptoms. Obes. Med. 2024, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, K.M.; Alonazi, W.B.; Vinluan, J.M.; Almigbal, T.H.; Batais, M.A.; Al Odhayani, A.; Alsadhan, N.; Tumala, R.B.; Moussa, M.; Aboshaiqah, A.E.; et al. Health promoting lifestyle of university students in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional assessment. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sociodemographic characteristics | N | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 18-22 years old | 139 | 61.0% |

| 23-26 years old | 82 | 36.0% | |

| Above 26 years | 7 | 3.1% | |

| Gender | Male | 102 | 44.7% |

| Female | 126 | 55.3% | |

| Marital status | Married | 16 | 7.0% |

| Unmarried | 212 | 93.0% | |

| Residence | Rural area | 114 | 50.0% |

| Urban Area | 114 | 50.0% | |

| Academic level | 2nd year | 68 | 29.8% |

| 3rd year | 58 | 25.4% | |

| 4th year | 21 | 9.2% | |

| 5th year | 43 | 18.9% | |

| 6th year | 38 | 16.7% | |

| Monthly family income (in riyals) | Less than 4,000 | 19 | 8.3% |

| 4,000-7,999 | 25 | 11.0% | |

| 8,000-14,999 | 53 | 23.2% | |

| 15,000-24,999 | 61 | 26.8% | |

| More than 25,000 | 70 | 30.7% | |

| Monthly income of the student (in riyals) | Less than 2,000 | 180 | 78.9% |

| More than 2,000 | 48 | 21.1% | |

| What is your current GPA? | Less than 3 | 11 | 4.8% |

| 3-4.5 | 76 | 33.3% | |

| More than 4.5 | 141 | 61.8% | |

| BMI | Less than 18.5 | 39 | 17.3% |

| 18.5-24.9 | 123 | 54.4% | |

| 25-29.9 | 30 | 13.3% | |

| 30-34.9 | 20 | 8.8% | |

| 35-39.9 | 9 | 4.0% | |

| 40 and above | 5 | 2.2% | |

| waist circumference | Less than 80cm | 94 | 41.2% |

| 80-88cm | 73 | 32.0% | |

| More than 88cm | 28 | 12.3% | |

| Less than 90cm | 22 | 9.6% | |

| 90-102cm | 5 | 2.2% | |

| More than 102cm | 6 | 2.6% | |

| Weight(kg); Mean and SD | 63.39 ± 18.93 | ||

| Length (in cm); Mean and SD | 163.48 ± 9.78 | ||

| Sociodemographic factors | Obesity | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Obese | Obese | |||||

| N | N% | N | N% | |||

| Age group |

18-22 years old | 114 | 82.0% | 25 | 18.0% | 0.247 |

| 22-26 years old | 73 | 89.0% | 9 | 11.0% | ||

| Above 26 years | 5 | 71.4% | 2 | 28.6% | ||

| Gender |

Male | 83 | 81.4% | 19 | 18.6% | 0.290 |

| Female | 109 | 86.5% | 17 | 13.5% | ||

| Marital status |

Married | 14 | 87.5% | 2 | 12.5% | 0.755 |

| Unmarried | 178 | 84.0% | 34 | 16.0% | ||

| Residence |

Rural area | 98 | 86.0% | 16 | 14.0% | 0.468 |

| Urban Area | 94 | 82.5% | 20 | 17.5% | ||

| Academic level |

2nd year | 58 | 85.3% | 10 | 14.7% | 0.746 |

| 3rd year | 46 | 79.3% | 12 | 20.7% | ||

| 4th year | 18 | 85.7% | 3 | 14.3% | ||

| 5th year | 36 | 83.7% | 7 | 16.3% | ||

| 6th year | 34 | 89.5% | 4 | 10.5% | ||

| Monthly family income (in riyals) |

Less than 4,000 | 13 | 68.4% | 6 | 31.6% | 0.273 |

| 4,000-7,999 | 21 | 84.0% | 4 | 16.0% | ||

| 8,000-14,999 | 44 | 83.0% | 9 | 17.0% | ||

| 15,000-24,999 | 55 | 90.2% | 6 | 9.8% | ||

| More than 25,000 | 59 | 84.3% | 11 | 15.7% | ||

| Monthly income of the student (in riyals) |

Less than 2,000 | 148 | 82.2% | 32 | 17.8% | 0.111 |

| More than 2,000 | 44 | 91.7% | 4 | 8.3% | ||

| Do you exercise regularly? | Yes | 76 | 85.4% | 13 | 14.6% | 0.695 |

| No | 116 | 83.5% | 23 | 16.5% | ||

| Dietary habits | Obesity | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Obese | Obese | |||||

| N | N% | N | N% | |||

| How often do you consume fruits per week? |

Less than or equal to 3 days | 159 | 84.1% | 30 | 15.9% | 0.939 |

| More than 3 days | 33 | 84.6% | 6 | 15.4% | ||

| How often do you consume vegetables per week? |

Less than or equal to 3 days | 112 | 83.6% | 22 | 16.4% | 0.756 |

| More than 3 days | 80 | 85.1% | 14 | 14.9% | ||

| How many meals do you eat a day? |

Less than or equal to three days | 162 | 84.4% | 30 | 15.6% | 0.875 |

| More than 3 days | 30 | 83.3% | 6 | 16.7% | ||

| How many days do you usually eat fast food each week? |

Less than or equal to 3 days | 113 | 85.6% | 19 | 14.4% | 0.498 |

| More than 3 days | 79 | 82.3% | 17 | 17.7% | ||

| How many days a week do you drink sugar-sweetened soft drinks? |

Less than or equal to 3 days | 130 | 83.9% | 25 | 16.1% | 0.838 |

| More than 3 days | 62 | 84.9% | 11 | 15.1% | ||

| Do you have a family (first-degree relative) history of obesity? | Yes | 60 | 83.3% | 12 | 16.7% | 0.805 |

| No | 132 | 84.6% | 24 | 15.4% | ||

| Factors | Obesity | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not Obese | Obese | |||||

| N | N% | N | N% | |||

| Do you suffer from high blood pressure? |

Yes | 6 | 75.0% | 2 | 25.0% | 0.615 |

| No | 186 | 84.5% | 34 | 15.5% | ||

| Do you suffer from diabetes? |

Yes | 7 | 70.0% | 3 | 30.0% | 0.197 |

| No | 185 | 84.9% | 33 | 15.1% | ||

| Do you suffer from high blood fat levels? |

Yes | 16 | 72.7% | 6 | 27.3% | 0.129 |

| No | 176 | 85.4% | 30 | 14.6% | ||

| Are you currently using a medication that belongs to any of the following drug classes? (Corticosteroids, B-blockers, antidiabetics, antipsychotics, antidepressants) | Yes | 14 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.134 |

| No | 178 | 83.2% | 36 | 16.8% | ||

| What is your current GPA? | Less than 3 | 9 | 81.8% | 2 | 18.2% | 0.975 |

| 3-4.5 | 64 | 84.2% | 12 | 15.8% | ||

| More than 4.5 | 119 | 84.4% | 22 | 15.6% | ||

| Variable | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 18-22 years (Reference category) | |||||

| 22-26 years | -.863 | .637 | 1.834 | 1 | .176 | .422 |

| >26 years |

.650 | 1.140 | .325 | 1 | .569 | 1.915 |

| Gender | Male (Reference Category) | |||||

| Female |

-.693 | .425 | 2.651 | 1 | .103 | .500 |

| Marital status | Married (reference category) | |||||

| Unmarried |

.716 | .937 | .583 | 1 | .445 | 2.046 |

| Residence | Rural area (Reference category) | |||||

| Urban area |

.348 | .402 | .750 | 1 | .387 | 1.416 |

| Academic level | 2nd year (Reference category) | |||||

| 3rd year | .539 | .514 | 1.101 | 1 | .294 | 1.715 |

| 4th year | -.036 | .767 | .002 | 1 | .962 | .964 |

| 5th year | .440 | .736 | .358 | 1 | .550 | 1.553 |

| 6th year |

-.005 | .874 | .000 | 1 | .996 | .995 |

| Monthly family income (in riyals) | Less than 4,000 riyal (Reference category) | |||||

| 4,000-7,999 riyal | -.662 | .838 | .623 | 1 | .430 | .516 |

| 8,000-14,999 riyal | -.658 | .701 | .880 | 1 | .348 | .518 |

| 15,000-24,999 riyal | -1.469 | .733 | 4.019 | 1 | .045 | .230 |

| More than 25,000 riyal |

-.836 | .714 | 1.372 | 1 | .241 | .433 |

| Monthly income of student | Less than 2,000 riyal (Reference category) | |||||

| More than 2,000 riyal |

-.858 | .598 | 2.057 | 1 | .152 | .424 |

| Do you exercise regularly? | Yes (Reference category) | |||||

| No | .276 | .417 | .436 | 1 | .509 | 1.317 |

| Risk factors | B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| How often do you consume fruits per week? | Less than or equal to three days (Reference category) | |||||

| More than 3 days |

.008 | .580 | .000 | 1 | .989 | 1.008 |

| How often do you consume vegetables per week? | Less than or equal to three days (Reference category) | |||||

| More than 3 days |

-.127 | .411 | .095 | 1 | .758 | .881 |

| How many meals do you eat a day? | Less than or equal to three meals per day (Reference category) | |||||

| More than 3 meals |

.078 | .563 | .019 | 1 | .890 | 1.081 |

| How many days do you usually eat fast food each week? | Less than or equal to three days (Reference category) | |||||

| More than 3 days |

.314 | .405 | .600 | 1 | .439 | 1.368 |

| How many days a week do you drink sugar-sweetened soft drinks? | Less than or equal to three days (Reference category) | |||||

| More than 3 days |

-.211 | .432 | .239 | 1 | .625 | .810 |

| Do you have a family (first-degree relative) history of obesity? | Yes (Reference category) | |||||

| No | -.107 | .392 | .074 | 1 | .785 | .899 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).