1. Introduction

Sex and gender have a wide range of effects on the susceptibility, prevalence, presentation (clinical and laboratory) and outcomes of various clinical disorders [

1,

2]. For instance, autoimmune diseases effect females much more than males [

3]. Conversely, cardiovascular and brain disorders are more common among males [

4]. The source of such differences are not completely elucidated. Several factors contribute to the variability including genetic and hormonal factors [

5], differences in immune responses and immune activation states [

6], different drug metabolism rates [

7] as well as educational and socioeconomic factors [

1].

Women account for 52% of people living with HIV worldwide [

8].

Females, especially in Sub- Sahara Africa, are highly affected by the HIV pandemic. About 50-60% of all people living with HIV in low and middle-income countries are females while their proportion in western, high income countries is much lower [

9]. Females are at increased risk, compared to males, for HIV acquisition via heterosexual intercourse. The male to female transmission of HIV was shown to be more efficient than female to male HIV transmission [

10,

11]. Furthermore, several studies have suggested that the usage of hormonal contraception increases the risk of female HIV acquisition [

12]. As for the course and outcome of females and males with HIV infection the results of the studies are controversial. Several studies reported rapid progression to AIDS with a worse outcome in females compared to males with HIV [

13,

14]. Contrary, better outcome with less mortality rates among HIV infected females compared to males were reported by other studies [

15,

16]. The above results may originate from an invalid comparison of different cohorts of female and male HIV patients (e.g. males who have sex with males – MSMs to heterosexual females including sex workers). Differences in educational and socioeconomic status as well as disparity in access to care and treatment contribute to bias results as does the under representation of females in clinical trials [*], rather than a real gender differences. Consequently, it is still unknown whether gender influences the presentation, course and outcome of HIV infection.

In our HIV/AIDS centers (Kaplan medical center, Rehovot and Haddasa medical center, Jerusalem, both in Israel) we take care of many HIV patients, females and males who immigrated to Israel from Ethiopia. These patients have the same genetic background and a similar educational and socioeconomic status with equal access to healthcare and modern antiretroviral medications (free of charge). All these patients acquired HIV via heterosexual contacts. This enables us to assess the real influence of gender on HIV infection at the time of diagnosis (disease presentation), course (clinical, virologic and immunological) and outcome of the disease.

2. Patients and Methods

The study is a retrospective cohort study of all HIV/AIDS patients of Ethiopian origin who were diagnosed with HIV during the years 2000-2015 in Neve Or (Kaplan medical center Rehovot) and Haddasa (Haddasa medical center, Jerusalem Israel) HIV/AIDS centers. Patients who were under 18 years of age at the time of diagnosis and patients with less than one year of follow up were excluded from the study .The study was approved by the Kaplan and Haddasa medical centers ethic committees. The Ethics Committee approval number is 0036-10-KMC.

HIV was diagnosed by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) and confirmed by Western Blot analysis. Cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) cell counts were determined by fluorescence- activated cell sorting using fluorescein iisothiocyanate-conjugated monoclonal antibodies (IQ Products,Groningen, Netherlands). HIV viral load (VL) was determined by COBAS Ampliprep/COBAS AMPLICOR HIV-1 MONITOR Test, version 1.5 (CAP/CA;Roche Molecular System, Branchburg,NJ) . HIV-1 subtypes were determined by the REGA HIV-1 subtyping tool (

www.hivdb.sanford.edu/hiv). AIDS was defined according to the CDC criteria [

17]

For each enrolled patient we obtained all epidemiological and socioeconomic data (gender, mode of acquisition, age at diagnosis, age at the end of the study, marital status, and employment status), virological (VL) and immunological status (CD4 cell counts) at diagnosis and thereafter every 1-4 months till the end of the study according to the patients' clinical status. VL below 400 copies/ml until 2007, below 40 in the years 2007-2011 and below 20 copies/ml from November 2011 were defined as lower detection limit (LDL).

Treatment (HAART) was based on a backbone of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTI) either with non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTI), integrase inhibitors (I) or boosted protease inhibitors (PI). Compliance to HAART was graded as high (>90% adherence) or low (<90% adherence) depending on the impression of the caregivers (physicians or nurses). Clinical and laboratory follow up data for each patient were obtained from clinical and hospital records including attendance to clinical visits in the last year of follow up, concomitant illness (malignancy, myocardial infarction/ischemic heart disease, transient ischemic attack/cerebrovascular accident, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, renal impairment defined as creatinine >1.4mg% and/or urinary microalbumin/creatinine ratio above 100 µg/mg creatinine in 2 consecutive assays and liver disease), hospitalizations (defined as ≥24 hours admission to a hospital department) and AIDS. End of follow up was defined as the last documented clinical visit for alive patients or the date of death for patients who died throughout the years of study.

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Chi-square tests, Mann-Whitney and Person Correlation were used for statistical analysis. P≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. For multiple comparisons, we used alpha adjustments. Backward stepwise logistic regression analysis was conducted to identify association between the independent variables (sex, age at diagnosis, CD4 count at diagnosis, VL at diagnosis) and the dependent variables (death, AIDS).

3. Results

Five hundred fifty seven, 223 (40%) males and 334 (60%) females, HIV patients were included in the present study. all patients were immigrants from Ethiopia (Africa) diagnosed with HIV in Neve-Or or Hadassah HIV/AIDS centers during the years 2000-2015. The ratio between females and males (60/40) HIV patients did not change significantly along the years of the study. All patients were infected with type C virus via heterosexual contacts.

Most of the patients, females as well as males, immigrated to Israel from small rural villages with low levels (<8 years) of formal education. The socioeconomic status of the females and males in our study was similar. Only 40% of our patients worked at the time of the study (40% and 38% for males and females, respectively; P=NS). 55% of the males were married compared to 36% of the females (p=0.0001). About 35% of the patients were divorced (P=NS between males and females). Interestingly, significantly more females than males (16% vs. 5%; P=0.0002) were widowers. Partners of 41% of our male and 36% of our female patients (P=NS) were known to be also infected with HIV.

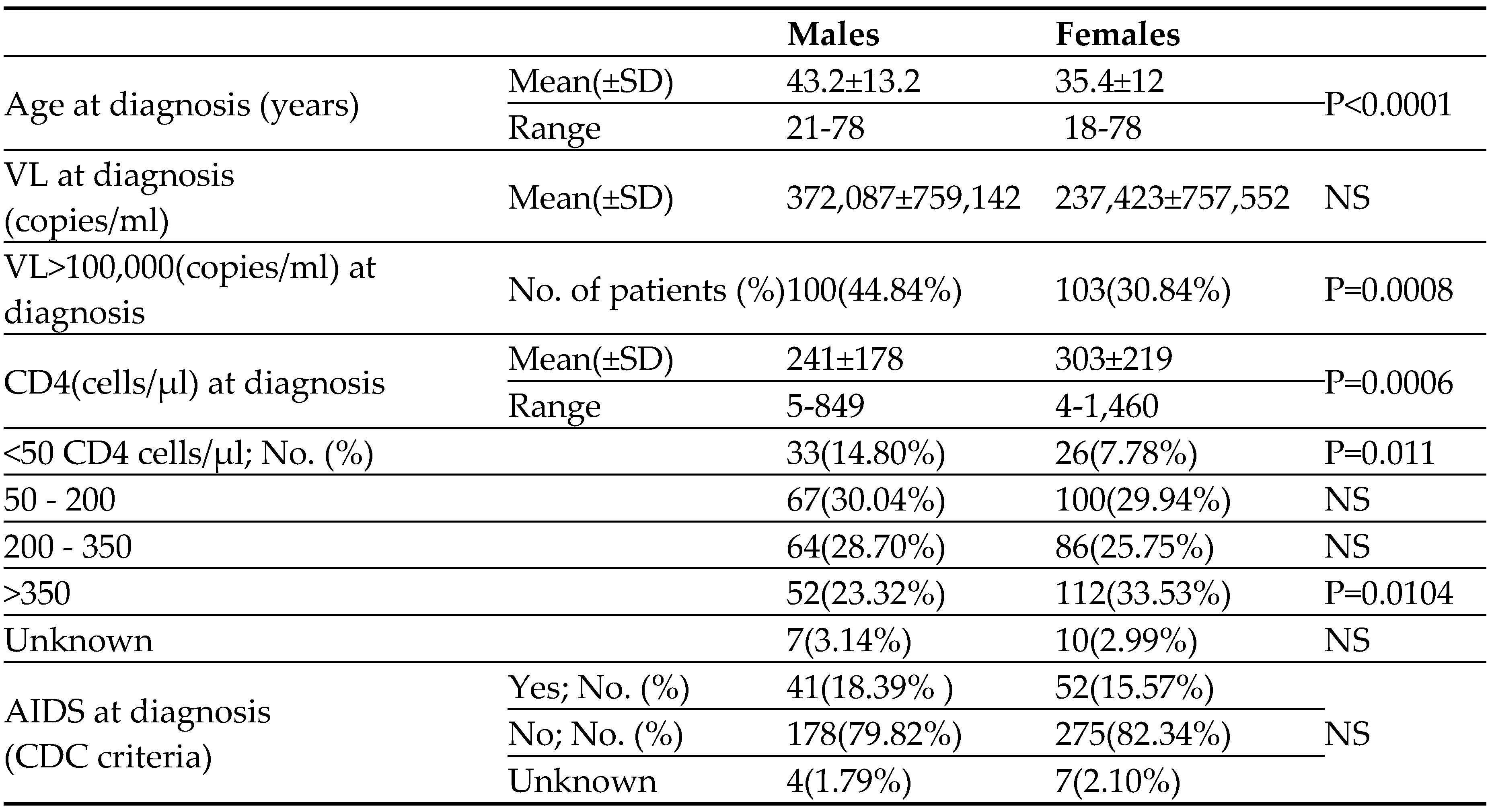

As can be seen in

Table 1, at the time of HIV diagnosis the male patients were significantly older (43.2±13.2 years) compared to the female patients (35.4±12; P<0.0001). HIV male patients were presented with higher VL, compared to females. 45% of our male patients presented with high VL (>100,000 copies/ml) as compared to 31% of the HIV female patients (P=0.0008) (

Table 1). At the time of HIV diagnosis, the immune system of the males was more impaired than that of the female patients; the mean CD4 cells count of the males was significantly lower compared to the females (241±178 vs. 303±219 cells/µl; P=0.0006). Moreover, fewer males than females presented with high (>350cells/µl) CD4 cell counts whereas the proportion of males in the lower range of CD4 cell counts (<50 cells/µl) was much higher (15% vs. 8% for males and females, respectively; P=0.011) (

Table 1). Since the immune system of patients firstly diagnosed with HIV at older age (>50 years) was shown to be less functional (↓CD4) than that of the younger patients [

18], we compared the CD4 cell counts of our older males and females (diagnosed above the age of 50 years). As was shown for the entire group of patients (

Table 1), the CD4 cell counts of the older males at the time of HIV diagnosis was significantly lower compared to the counts of the older HIV female patients (195±155 vs. 316±273 cells/µl for older males and older females, respectively ; P=0.0046). The rate of AIDS at the time of HIV diagnosis was significantly higher among our male patients (

Table 1).

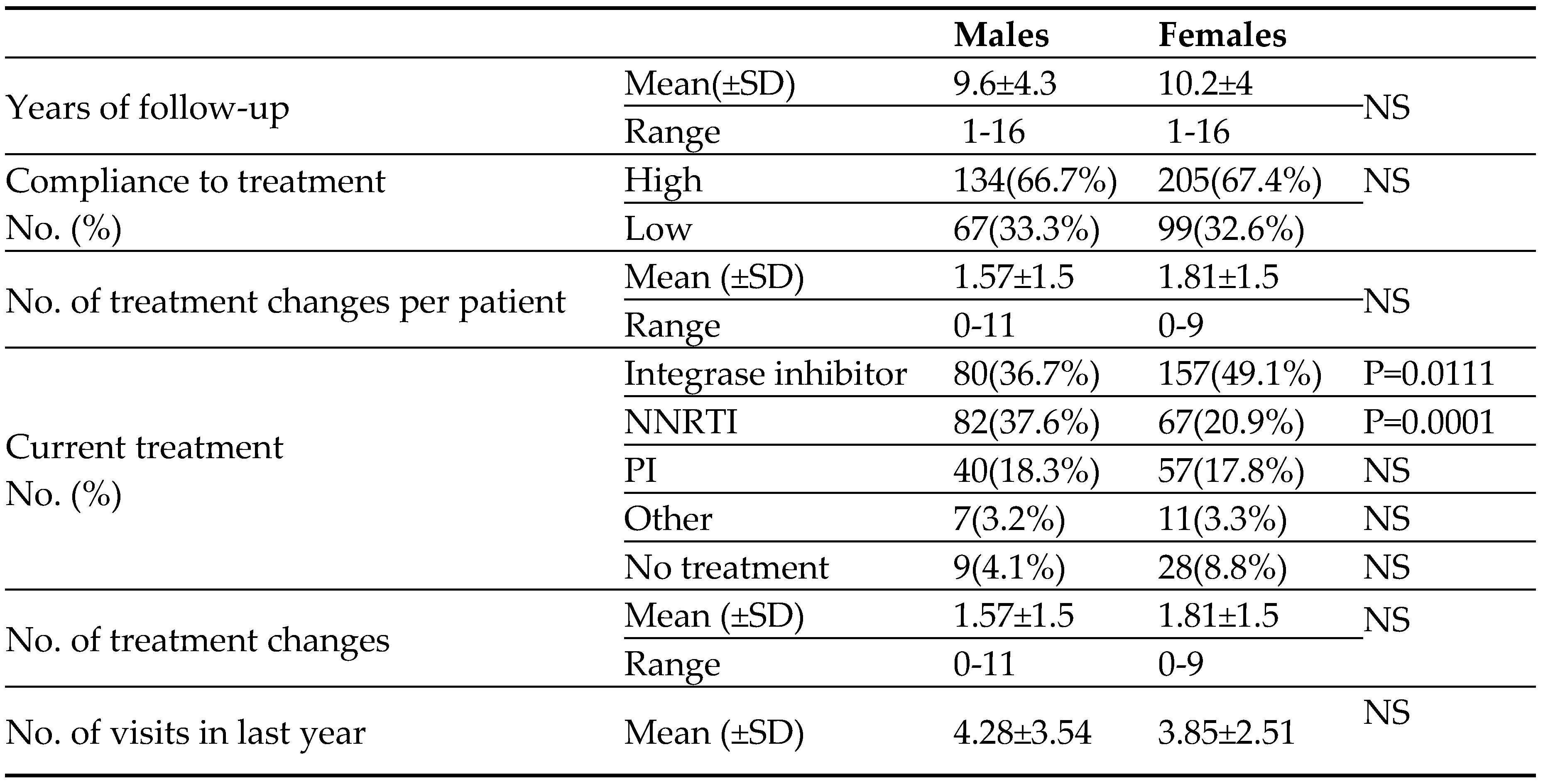

The mean follow-up period from the time of HIV diagnosis was similar in the two groups of patients (9.6±4.3 years for males and 10.2±4 years for females). Overall about 6000 patients' years. As can be seen in

Table 2, there were no differences in compliance to treatment, the number of HAART medication switches (per patient) and the number of clinical visits (per patient) during the last year of the study between male and female HIV patients. Not surprisingly, the portion of HIV females (mainly at the child bearing age) treated with NNRTI HIV medication was significantly lower than that of males (

Table 2).

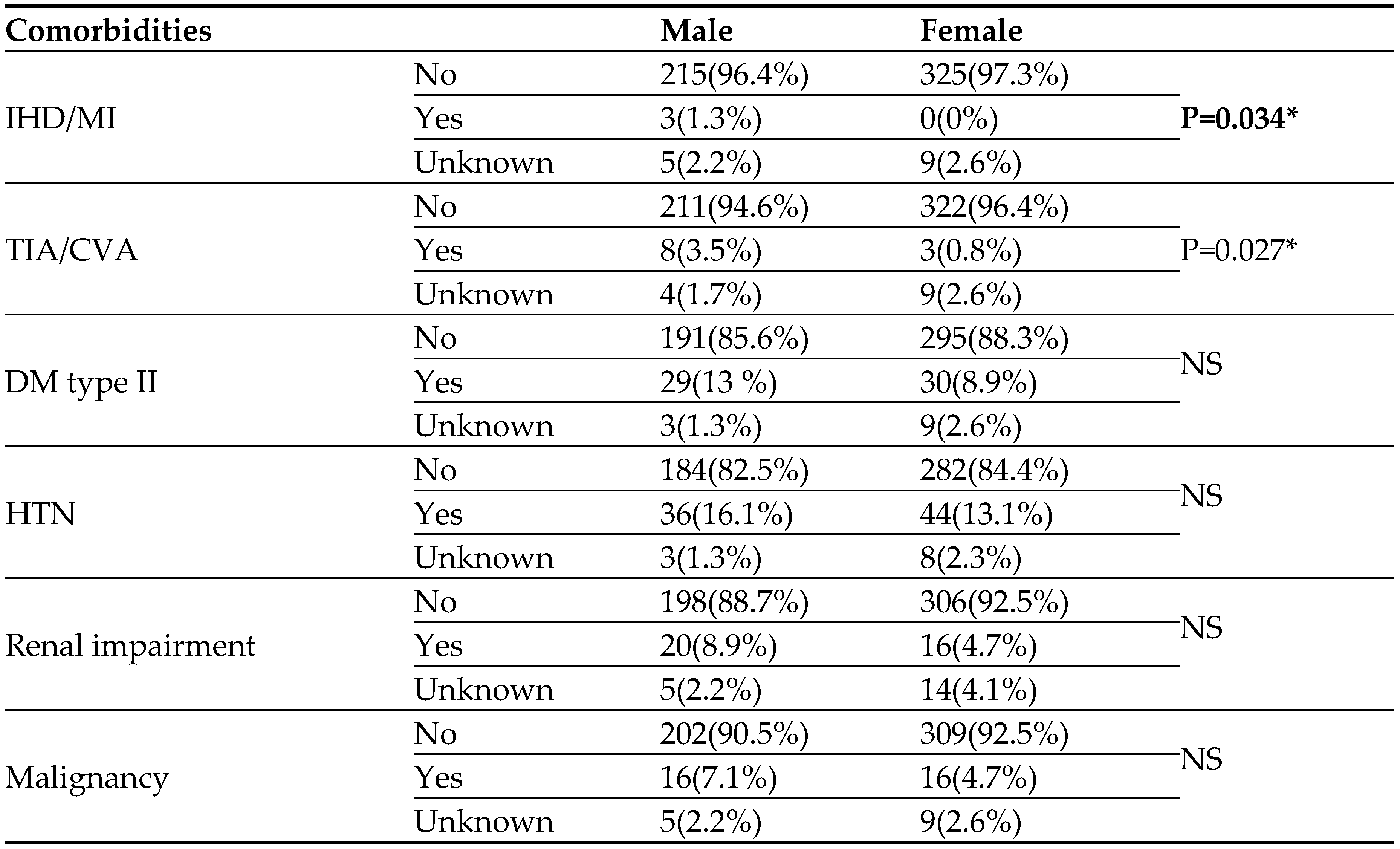

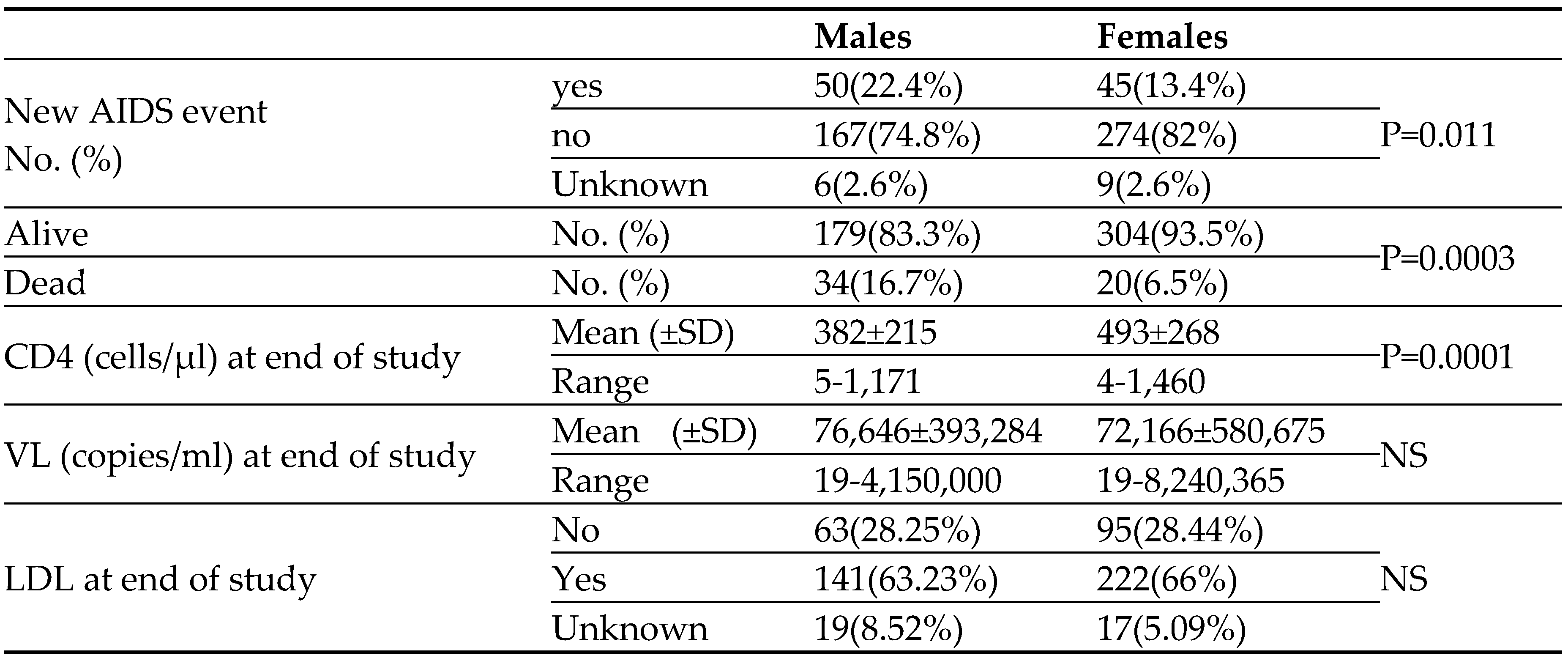

As can be seen in

Table 3, the rate of comorbidities observed in our cohort along the follow up period was low. The males had significantly more ischemic heart disease, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accidents or transient ischemic attacks than females, though the rate was quite low (

Table 3). The rates of the other morbidities, Diabetes mellitus (type II), Hypertension, renal impairment and malignancy were similar in the two groups of patients. Clinical liver diseases were not observed in our cohort. It should be noted that the prevalence of HBV (12%) and HCV (1%) among our males and females HIV patients is very low.

In addition to the patients who were presented with AIDS at the time of HIV diagnosis (

Table 1), 95 patients developed new AIDS during the years of the study. As can be seen in

Table 4, this occurred in males (23%) significantly (P=0.011) more than in the female HIV patients (14%). The main new AIDS defining clinical conditions were infections. The mean CD4 cell counts, at the end of the study was significantly higher in the female HIV patients (493±268 vs. 382±215 cells/µl for females and males, respectively; P=0.0001). Similar significant differences in CD4 cell counts at the end of the study were observed among the younger patients (498±244 vs. 311 ±190 cells/µl for females and males younger than 50 years, respectively; P=0.0006) and the older patients (480±244 vs 311±190cells/µl for females and males older than 50 years, respectively; P=0.0001). Furthermore, CD4 cell counts at the end of the study were significantly higher in females than in the male patients regardless of their CD4 cell counts at the time of HIV diagnosis (403±250 vs. 287±171 cells/µl P= 0.001, 509±269 vs.422±223 cells/µl P=0.03, 566±254 vs.486±211 cells/µl P=0.04 for females and males presented at the time of HIV diagnosis with CD4 cell counts below 200, between 200-350 and above 350cells/µl, respectively). At the end of the study the mean VL as well as the rate of patients (65%) achieving LDL were similar between the females and males HIV patients.

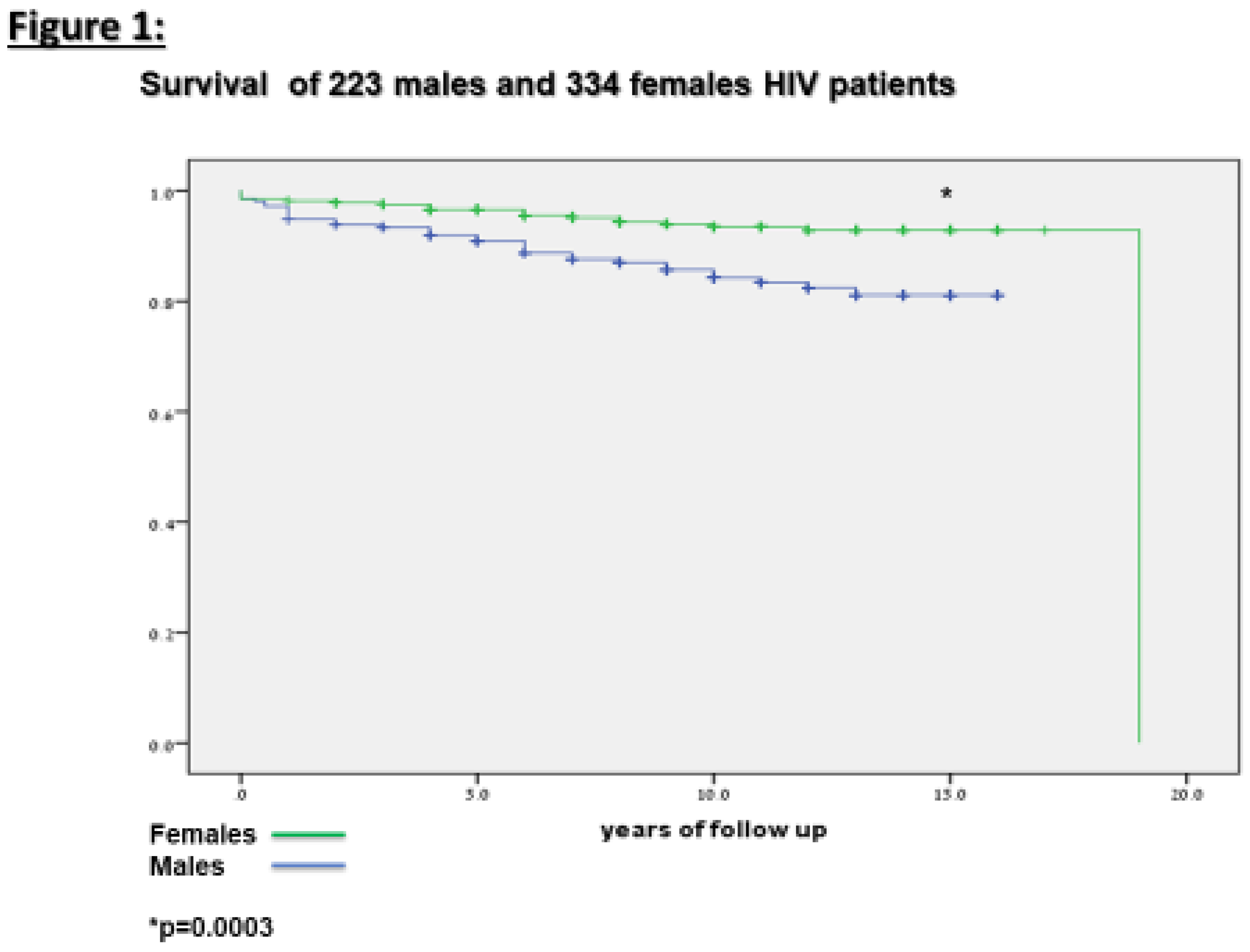

Fifty seven (10%) of or patients died throughout the years of the study. as can be seen in

Table 4 and

Figure 1, mortality was significantly higher among the males (16.7%) compared to the female (6.5%) HIV patients.

4. Discussion

The main finding of our study is that gender has an effect on the course of HIV. At the time of HIV diagnosis females presented at younger age with higher CD4 cell counts compared to HIV male patients. Furthermore, females with HIV had a better outcome than males with less new AIDS events, enhanced reconstitution of their immune system (higher CD4 cell counts) and higher survival rates .These significant advantages were preserved when comparing males and females at the same age groups.

The results of previous studies aimed to compare differences in the course of HIV between females and males are controversial [

13,

14,

15,

16]. This probably due to differences between the male and female groups of HIV patients in those studies, regarding the route oh HIV acquisition, socioeconomic and educational status and access to healthcare and treatment. Those differences have a major effect on the course of HIV infection. Therefore we chose to study a homogenous group of females and males HIV patients. All patients immigrated to Israel from Ethiopia, thus they have similar genetic background. The females and the males in our study have similar educational and socioeconomic status, they have similar good access to healthcare and treatment and all were infected with type C HIV virus via heterosexual contacts. This enabled us to study the real effect of gender on the course of HIV infection.

Our study has several limitations. First all our patients were infected via heterosexual contacts with type C HIV virus. In patients with other HIV subtypes the gender effect may be different. Second, we studied a specific group of patients regarding their background and socioeconomic status. Our results may not apply to other groups of patients. The study's advantages include a specific cohort that enabled us to isolate and to investigate the real effect of gender on HIV. This study is relevant to the large HIV population in sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, the follow up period is quit long (mean of 10 years), longer follow up studies may be needed in order to define the effect of gender on the outcome of HIV.

To conclude, in our cohort we showed that the presentation, clinical course and outcome of HIV males is less favorable, compared to females, with higher rates of immunological impairment, AIDS and mortality.

References

- Arnold AP. Promoting the understanding of sex differences to enhance equity and excellence in biomedical science. Biol Sex Differ. 2010 Nov 4;1(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Nicolson TJ, Mellor HR, Roberts RR. Gender differences in drug toxicity. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010 Mar;31(3):108-14. [CrossRef]

- Whitacre CC, Reingold SC, O'Looney PA. A gender gap in autoimmunity. Science. 1999 Feb 26;283(5406):1277-8.

- Appelman Y, van Rijn BB, Ten Haaf ME, Boersma E, Peters SA. Sex differences in cardiovascular risk factors and disease prevention. Atherosclerosis. 2015 Jul;241(1):211-8. [CrossRef]

- Morrow EH. The evolution of sex differences in disease. Biol Sex Differ. 2015 Mar 13;6:5. [CrossRef]

- Griesbeck M, Scully E, Altfeld M. Sex and gender differences in HIV-1 infection. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016 Aug 1;130(16):1435-51. [CrossRef]

- Sramek JJ, Murphy MF, Cutler NR. Sex differences in the psychopharmacological treatment of depression. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2016 Dec;18(4):447-457.

- Shringar Rao. Sex differences in HIV-1 persistence and the implications for a cure. Front Glob Womens Health. 2022 Sep 23;3:942345. [CrossRef]

- WHO (2014) Global Summery of the AIDS epidemic 2014, WHO-Department, UNAIDS.

- Patel P, Borkowf CB, Brooks JT, Lasry A, Lansky A, Mermin J. Estimating per-act HIV transmission risk: a systematic review. AIDS. 2014 Jun 19;28(10):1509-19. [CrossRef]

- Nicolosi A, Corrêa Leite ML, Musicco M, Arici C, Gavazzeni G, Lazzarin A. The efficiency of male-to-female and female-to-male sexual transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus: a study of 730 stable couples. Italian Study Group on HIV Heterosexual Transmission. Epidemiology. 1994 Nov;5(6):570-5.

- Ralph LJ, Gollub EL, Jones HE. Hormonal contraceptive use and women's risk of HIV acquisition: priorities emerging from recent data. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Dec;27(6):487-95. [CrossRef]

- Bozzette SA, Berry SH, Duan N, Frankel MR, Leibowitz AA, Lefkowitz D, Emmons CA, Senterfitt JW, Berk ML, Morton SC, Shapiro MF. The care of HIV-infected adults in the United States. HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study Consortium. N Engl J Med. 1998 Dec 24;339(26):1897-904.

- Stewart KE, Ross D. Severe adverse life events and depressive symptoms among women with or at risk of HIV infection. AIDS. 1999 Dec 3;13(17):2477-8.

- Maskew M, Brennan AT, Westreich D, McNamara L, MacPhail AP, Fox MP. Gender differences in mortality and CD4 count response among virally suppressed HIV-positive patients. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2013 Feb;22(2):113-20. [CrossRef]

- Cornell M, Schomaker M, Garone DB, Giddy J, Hoffmann CJ, Lessells R, Maskew M, Prozesky H, Wood R, Johnson LF, Egger M, Boulle A, Myer L; International Epidemiologic Databases to Evaluate AIDS Southern Africa Collaboration. Gender differences in survival among adult patients starting antiretroviral therapy in South Africa: a multicentre cohort study. PLoS Med. 2012;9(9):e1001304. Epub 2012 Sep 4.

- Schneider E, Whitmore S, Glynn KM, Dominguez K, Mitsch A, McKenna MT; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Revised surveillance case definitions for HIV infection among adults, adolescents, and children aged <18 months and for HIV infection and AIDS among children aged 18 months to <13 years--United States, 2008. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008 Dec 5;57(RR-10):1-12.

- Asher I, Guri KM, Elbirt D, Bezalel SR, Maldarelli F, Mor O, Grossman Z, Sthoeger ZM. Characteristics and Outcome of Patients Diagnosed With HIV at Older Age. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016 Jan;95(1):e2327. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of 223 males and 334 females at the time of HIV diagnosis.

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory characteristics of 223 males and 334 females at the time of HIV diagnosis.

Table 2.

Follow up and treatment regimens of 223 males and 334 females HIV patients.

Table 2.

Follow up and treatment regimens of 223 males and 334 females HIV patients.

Table 3.

Comorbidities of 223 male and 334 female HIV patients along the follow up period.

Table 3.

Comorbidities of 223 male and 334 female HIV patients along the follow up period.

Table 4.

Clinical and laboratory outcome of 223 males and 334 females HIV patients.

Table 4.

Clinical and laboratory outcome of 223 males and 334 females HIV patients.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).