Introduction

Since its establishment, the Macau Special Administrative Region has undergone rapid economic development. According to statistical data from the Statistics and Census Service (DSEC) of Macau, 1999–2018, Macao's GDP grew from 6.55 billion to 55.3 billion. With the increase in the income of Macao residents, the demand for financial services and financial products, including wealth management, has become increasingly important. As one of the most well-developed financial sectors in Macau, the banking industry has played an important role in its economic development.

Meanwhile, with the continuous innovation and development of technology, such as the rapid rise of fintech, the financial environment in Macau has undergone tremendous changes over the past few years, and the structure and needs of the banking user base are constantly changing. These changes have led to the upgrading of financial services, disrupting the traditional banking business model, and driving the transformation of financial services into digitalization. To open up a new financial digitalization landscape, the Bank of China introduced the concept of self-service banking to Macau for the first time, following the opening of self-service banking in many provinces and cities in Mainland China. Compared with traditional ATMs where money can only be withdrawn and deposited, the Bank of China's self-service banking machine has an easy-to-understand touch operation interface and provides over 170 financial services in 20 categories, including card opening, activation, contract signing, financial management, RMB remittance, cross-border remittance, loss of funds, printing of bank slips, and balance inquiries, realizing instant processing of non-cash business at the bank branches. Internet Plus integration is another major feature of self-service banking. It introduces an e-commerce shopping model into the wealth management business, making the purchase of wealth management products more intuitive and easier. Self-service banking machines enhance customer experiences. Academic research has also found that the introduction of self-service banking technology saves time and costs for banks, increases productivity and efficiency, and enhances customer loyalty and satisfaction (Shamdasani, Mukherjee, and Malhotra 2008)

Although self-service banking has already emerged in Macau, studies on the determinants of consumer decisions on whether to use self-service banking technologies have not been conducted. Although studies on e-banking have been conducted in other countries and regions, the results may vary due to different statistical populations and cultural differences. Thus, it is essential to study the effects of Macau’s self-service banking system.

Numerous studies conducted in other countries and regions have shown that customer satisfaction is one of the key drivers of user acceptance of information systems (Chen and Chen 2009). Therefore, it is important to identify the factors that influence customer satisfaction. If customers are completely satisfied with the organization or its products, they share their experiences with others and become a channel for word-of-mouth advertising, thus reducing the cost of attracting new customers (Pooya, Khorasani, and Ghouzhdi 2019). Furthermore, satisfaction can influence customers’ attitudes and intentions to repurchase (Oliver 1980). In the e-services sector, excellent service quality is essential to be successful as well as to gain customer satisfaction; providing high-quality services will continue to create a competitive advantage for the services industry. Simultaneously, for users, the state of readiness for a new technology affects the outcome of their experience with self-service banking, which, in turn, affects customer satisfaction (Boon-itt 2015). Little research has been conducted on the impact of customer-specific attributes, especially technology readiness, on the quality of self-service banking services and customer satisfaction. Therefore, it is important to explore the impact of technology readiness on quality of and satisfaction with self-service banking.

The purpose of this study is to explore the factors influencing the satisfaction level of self-service banking based on the demographics and cultural characteristics of Macao, to provide appropriate strategies for bank managers to improve customer satisfaction with self-service banking, and to provide a reference for further research work for anyone interested in this area.

Literature Review and Hypotheses

Technology Readiness

Technology readiness is related to a person's tendency to adopt new technologies and has an impact on the perception of service quality through self-service technologies. Highly technology-ready consumers are optimistic about the impact of technology, have high levels of innovation, are comfortable using technology, and have low levels of insecurity about technology (El-Gohary and Eid 2013). According to Parasuraman (2000), technological readiness is people’s propensity to adopt and use new technologies in their private and professional lives to achieve their goals. In this study, four dimensions–optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity–were used to test customers’ technology readiness. The first dimension, optimism, means that people have a positive attitude toward technology as it provides more control, flexibility, and efficiency in their lives. In the second dimension, innovation, people have a positive attitude toward using new technology and have a desire to use it. The third factor, discomfort, is a customer's negative feeling of being controlled. Fourth, insecurity comes from a lack of confidence in technology and its actual capabilities, and represents negative customer feelings. Parasuraman (2000) found that the higher the customers’ scores on the Technology Readiness Index, the more willing they were to buy or sell stocks online, use machines to buy air or train tickets, and have cell phone and Internet access. Similar results were obtained by Westjohn et al. (2009), who found that technology readiness is positively related to technology usage.

Relationship between Technology Readiness and Service Quality

Boon-itt (2015) predicts e-satisfaction in the context of digital banking in Thailand by testing a comprehensive model that integrates self-service technology adoption and technology acceptance models. In this study, technology readiness (TR) was found to influence the perceived service quality of self-service technology (SQ-SST): the higher the level of technology readiness of customers, the higher their perception of the quality of self-service operations. As an antecedent, customer technology readiness increases e-satisfaction. Vize et al. (2013) also pointed out that technology readiness is an important contributor to the eventual achievement of service quality and satisfaction, and that customers with a higher level of technical readiness perceive a higher quality of service from their network solution provider. Zeithaml, Parasuraman, and Malhotra (2002) found a positive association between technology readiness and e-service quality. Mummalaneni, Juan, and Kevin (2016) further indicated that consumer technology readiness positively influences the perceived efficiency, system availability, fulfilment, and privacy dimensions of e-service quality. Lin and Hsieh (2006) state that customer technology readiness is the most influential factor in self-service quality, and that technology readiness affects the perceived service quality of self-service technology (SST). The perceived service quality of SST positively affects customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions toward SST. Vize et al. (2013) develop and examine a model that measures the role of technology readiness (TR) in a business-to-business (B2B) context. This study found that service quality and satisfaction were outcomes of TR.

Hence, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Customers’ technology readiness positively affects their perceived service quality.

Relationship between Self-Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction

Amin (2016) shows that a higher level of Internet banking service quality significantly impacts e-customer satisfaction and consequently leads to e-customer loyalty and a lower intention to leave the relationship with the bank. Lin and Hsieh (2011) show that customer satisfaction has a significant positive relationship, both directly and indirectly, with service quality, loyalty, and behavioral intentions. Kao and Lin (2016) investigate the relationships between e-service quality, trust, satisfaction, loyalty, and brand equity in Taiwanese online banking. Their results indicate that the perceived quality formed through interaction with an online banking service positively affects customer trust and satisfaction, which, in turn, influences loyalty and brand equity. Felix (2017) finds a significant and positive relationship between service quality and customer satisfaction when comparing dimensions such as customer loyalty with reliability, responsiveness, and assurance. Robertson et al. (2016) find the impact of different self-service technologies (SSTs) on customer satisfaction and the continued use of SSTs. In this study, five antecedent constructs–reliability, ease of use, enjoyment, perceived control, and perceived speed–were identified as the main factors affecting customer satisfaction with SSTs. These factors affect customers’ willingness to repeat SST use. A study of travel technology found that service quality was a strong predictor of satisfaction with technology-enabled services (Wang, So, and Sparks 2017). Udo, Bagchi, and Kris (2010) show that system and information quality positively impact user satisfaction. Ting et al. (2016), whose aim was to better understand the e-service quality, e-satisfaction, and e-loyalty of online shoppers in the business-to-consumer market, indicated that all dimensions of e-service quality had a significantly positive impact on the e-satisfaction of online shoppers.

Based on these findings in literature, we hypothesize as follows:

H2. Self-service quality is positively related to customer satisfaction.

Relationship between Technology Readiness and Customer Satisfaction

Previous studies have shown that perceived service quality plays an important role in banking services by having a direct impact on customer satisfaction, while simultaneously being a consequence of technology readiness. Considering the hypothesized relationship between technological readiness and customer satisfaction, exploring whether and how service quality mediates this relationship would also be instructive. Lin and Hsieh (2006) point out that although some existing studies suggest that technology readiness has a positive association with satisfaction, these studies have only investigated simple links between technology and satisfaction without developing a more complete framework capable of exploring the causal relationships between the main constructs. Lin and Hsieh (2006) suggest that the impact of technological readiness on customer satisfaction is mediated by service quality. In addition, Wang, So, and Sparks (2017) indicate that technology readiness is unlikely to directly influence a traveler’s overall satisfaction with a trip. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3. Customers’ technology readiness affects their satisfaction through perceived service quality.

Research Methodology

Data Collection

Data were collected using a structured questionnaire as measurement tool. The interviewers distributed the questionnaires online and asked respondents to help disseminate them to friends, relatives, or colleagues. We chose online field surveys instead of traditional paper-based surveys because the Internet is believed to be the most effective way to ensure respondent variety and quantity (Chang, Wang, and Yang 2009). However, various control and filter questions were used to ensure the quality of the survey. The purpose of the filter questions was to ensure that the respondents fit the basic restriction of using a self-service banking machine.

Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire comprised 60 questions on perceived service quality, technological readiness, and customer satisfaction. These questions are based on a comprehensive literature review.

The questionnaire has three parts dealing with independent, intermediate, and dependent variables. Additionally, one section was designed to collect demographic variables. The first part of the questionnaire concerned customer satisfaction (the dependent variable of this study) with reference to Amin (2016) and had five questions.

Perceived service quality is considered an intermediate variable determined by seven dimensions: functionality, enjoyment, security/privacy, assurance, design, convenience, and customization. These were measured using 20 items refined from the original 37 items of Lin and Hsieh (2011). Among them, functionality contained five items, enjoyment contained four items, security/privacy contained two items, assurance contained three items, design contained two items, convenience contained two items, and customization contained three items.

The independent variable in this study was technology readiness, measured using 18 items derived from Parasuraman (2000). It comprises four dimensions: optimism, innovativeness, discomfort, and insecurity.

The questionnaire was written in Chinese and English. The content of the questionnaire (wording and meaning) was carefully checked for clarity, validity, and non-repetition of the questions. Pre-testing was then conducted before the actual research to check the viability of the research instrument and improve its structure and content. The questionnaire was then distributed to bank customers with experience using self-service banking machines in Macao. Responses from the pilot tests were not used for further analysis. A seven-point Likert scale was used to measure e-customer satisfaction, self-service quality, and technology from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (7).

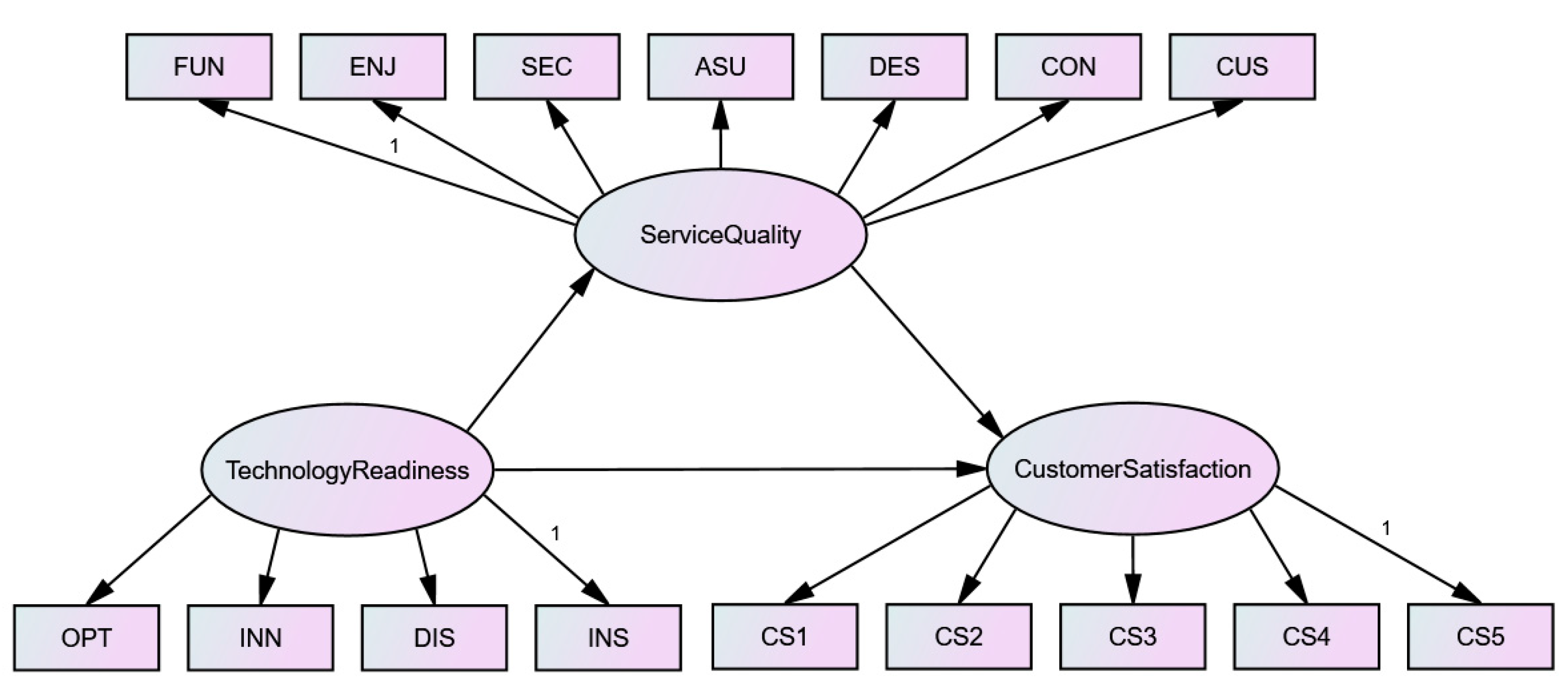

Conceptual Framework

The structural model used to explore the relationships among technology readiness, service quality, and customer satisfaction is illustrated in

Figure 1. The hypotheses were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM), a collection of statistical techniques that allows the study of the relationship between one or more continuous or discrete independent variables (IV) and one or more dependent variables (DV) (Ullman and Bentler 2013), using AMOS version 24 software and SPSS version 26.

Results and Discussion

Descriptive Analysis

For the final survey, 207 questionnaires were collected, seven incomplete questionnaires were eliminated, and 200 were retained for analysis. All participants were Macau residents who used the self-service banking system of the Bank of China (Macau). The response rate was 96.6%. The respondents’ demographic characteristics are listed in

Table 1.

Among these respondents, 64% were female and the majority of the sample ranged in age from 25 to 35 years (50%). It is also worth noting that 89% of the respondents had an educational degree of college or above, and most of the participants spent more than 14 hours per week (55%). Of the respondents, 10% were students and the rest were employed, with the highest proportions working in transportation (12%), government (10%), finance/insurance (10%), and casino/tourism (8%).

Principal Components Analysis

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted to analyze the underlying factor structure of technology readiness and service quality. Factor analysis using Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was used to extract the underlying factors and minimize the number of variables with high loadings. All items with loading coefficients less than 0.4 or any items exhibiting cross-loadings above 0.30 were removed (Hankin, 1995; Lin and Hsieh, 2011). In addition, modification indices (MI) were used to select indicator variables and were removed if the variable had an MI of more than 3.84 (Chen and Chen 2009). Next, a new principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the remaining items. The results of the EFA and CFA are presented in

Table 2.

Table 2 summarizes the items included in each dimension suggested by the EFA results and shows that all the EFA and CFA loading coefficients are greater than 0.4 in absolute value. The cumulative percentage of variance explained by these components was close to 77.69%, indicating good fit (Lin and Hsieh 2006).

Reliability and Validity Test

A reliability test was performed using Cronbach’s α coefficient to examine the reliability and accuracy of the responses to the quantitative data. If the Cronbach’s α coefficient is higher than 0.8, it indicates excellent reliability; if the coefficient is between 0.7 and 0.8, it indicates good reliability; if the value is between 0.6 and 0.7, it indicates acceptable reliability; and if the value is less than 0.6, it indicates poor reliability.

A validity test was used to analyze whether the research items were reasonable and meaningful. A validity analysis was conducted using KMO values and communality to verify the validity of the data.

The KMO value was used to determine the suitability of the information extracted, and the communality value was used to exclude unreasonable research items.

Table 3 shows the Cronbach’s α coefficient, and KMO values for the measurements.

As we can see from the

Table 3, the Cronbach’s α coefficient of the technology readiness, self-service quality, and customer satisfaction are 0.901, 0.963, and 0.927, respectively, which are greater than 0.9, thus indicating that the reliability of the research data is of excellent quality. In summary, all data were highly reliable and could be used for further analyses.

The KMO values for all dimensions except security/privacy, design, and convenience were greater than 0.7, indicating that the data could be extracted effectively. In addition, the three dimensions of security/privacy, design, and convenience have only two research items and, therefore, have a KMO value of 0.5. However, all items have a communality value greater than 0.4, which means that information on the items can be extracted effectively.

Mean, Standard Deviation and Correlation between Variables

To provide a precondition for structural equation modeling, the correlation between the research variables was obtained. Because the scale of the variables in the research is an interval, the Pearson correlation is employed to serve as the basis for finding the relationship among variables. The correlation coefficients of the main variables of the study as well as their means and standard deviations are presented in

Table 4. All the correlation coefficients were significantly different from zero.

Hypotheses Test Results and Discussion

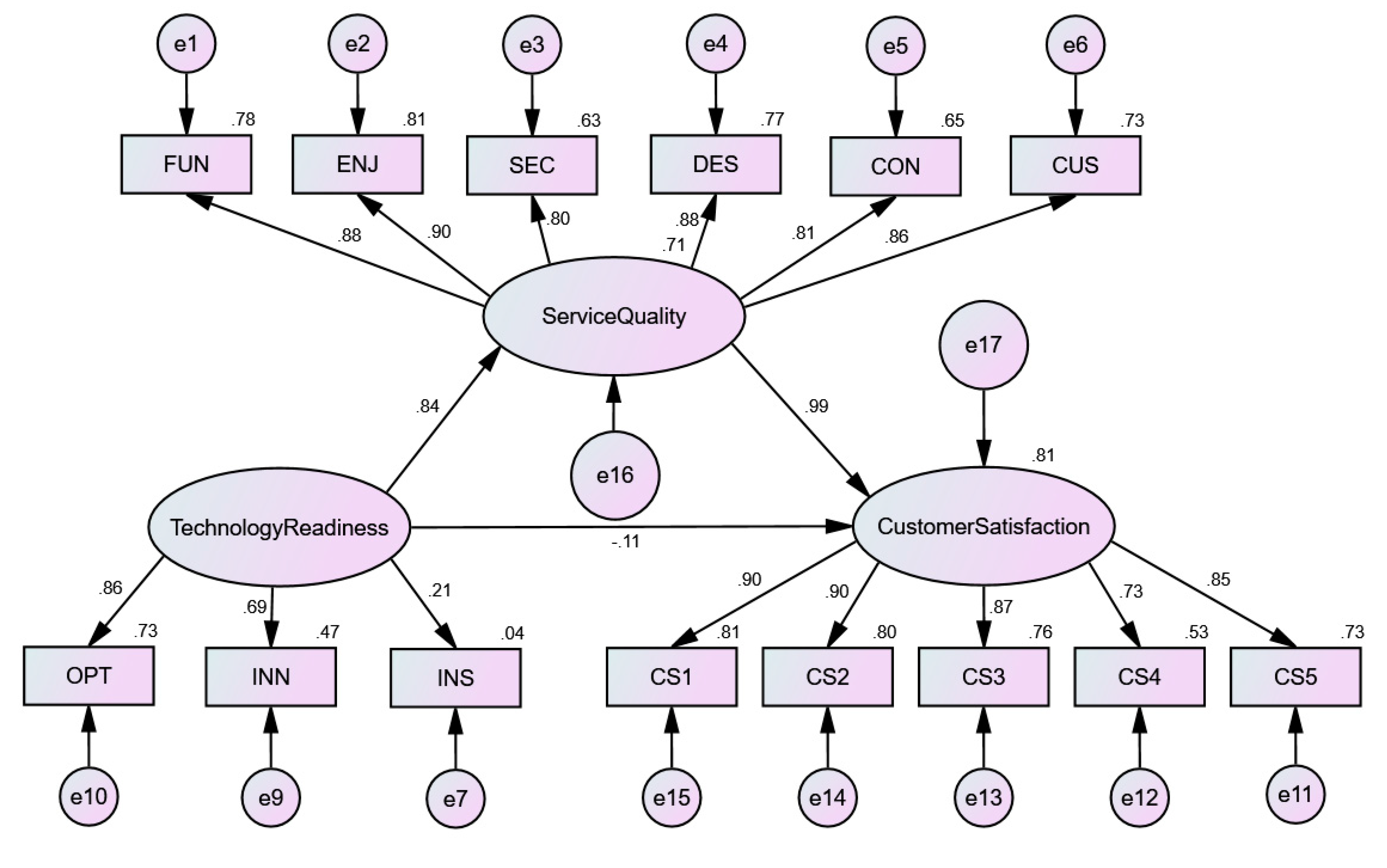

For all prescribed hypotheses, path coefficients and p-values were obtained (

Table 6). This table summarizes the confirmation and rejection of the defined hypotheses.

As predicted, technology readiness had a direct positive influence on self-service quality (path coefficient=0.837, p<0.01), while there was no statistically significant direct effect between technology readiness and customer satisfaction (path coefficient=−0.108, p=0.353). Thus, H1 and H3 are confirmed. The proposed effect of self-service quality on customer satisfaction is also found to be significantly positive (path coefficient=0.988, p<0.01), thereby supporting H2. These results highlight the importance of technology readiness and self-service quality in predicting customer satisfaction.

First, technology readiness, including the optimism, innovation, and insecurity dimensions, is an important factor in self-service quality, which is consistent with previous studies (Boon-itt 2015; Chen and Chen 2009; Lin and Hsieh 2006; Pooya 2019). This means that the higher the level of technological readiness of the customer, the higher the perceived service quality of the customer when using self-service banking. In other words, when customers are ready to embrace and use new technology, their evaluation of service quality may be high. Simultaneously, optimism, innovation, and insecurity were significant predictors of technology readiness, consistent with previous findings (Parasuraman 2000; Pooya 2009). Of these, optimism had the greatest impact on technology readiness, followed by innovation; insecurity had the weakest relationship with technology readiness. Our results also suggest that, while people are generally optimistic about technology (mean = 5.74), they experience considerable insecurity about their roles (mean = 4.79). This implies that even techno-optimists and innovators experience technology-related anxiety, which is consistent with Parasuraman (2000).

Second, our results support the hypothesis that perceived self-service quality has a significant positive association with customer satisfaction (Boon-itt 2015; Lin and Hsieh 2006; Parasuraman 2000; Pooya 2009). Self-service quality dimensions include functionality, enjoyment, security/privacy, design, convenience, and customization, all of which play important roles in determining self-service quality. Improving the quality of self-service banking can, in turn, lead to higher customer satisfaction, resulting in behavioral outcomes such as commitment, customer retention, a two-sided rewarding connection between service providers and customers, better customer tolerance of service delivery errors, and positive word-of-mouth for the bank (Arasli, Katircioglu, and Smadi 2005; Lin and Hsieh 2006).

Third, the relationship between technology readiness and customer satisfaction was not significantly positive, echoing Lin and Hsieh (2006). Our results show that the effect of technological readiness on customer satisfaction is mediated by self-service quality. In other words, customers with a more positive attitude towards technology, the ability to use it, and their willingness to adopt it are more likely to appreciate self-service banking, and thus have a higher perception of service quality, which in turn increases customer satisfaction. Therefore, banks should focus more on improving the perceived quality of self-service banking to satisfy customers with high technology readiness, which has a direct influence on customer satisfaction.

Practical Implications

Our results have practical implications for banks that use self-service technology. First, bank managers should drive customer perceptions of the quality of self-service banking by improving their technological readiness through various measures. For example, appealing to customers with ease of use, sufficient quantity, convenient location, and user-friendly interface designs to cater to their needs will invariably stimulate optimism and innovation in new technology, and an increase in drivers can have a more positive impact on customers' service experiences and perceptions of quality. Customer perception of self-service banking can be improved through user training and seminars. This will not only improve their understanding of how self-service banking works but also convince them that self-service technology is controllable, flexible, convenient, and effective for banking services, thereby reducing the negative impact of technology perceptions.

At the same time, it is clear that the path coefficients of optimism and innovation have a greater positive impact on technological readiness than on insecurity. Therefore, in terms of increasing users’ technology readiness, increasing optimism and innovation had a more significant impact on technology readiness than reducing customers’ insecurity. For example, banks can promote the positive sensory features that self-service banking can bring to people, such as significantly reducing queuing time and providing 24×7 services, through TV commercials and the Internet. In terms of innovation, younger generations, especially millennials and Generation Z, are more willing to accept and challenge new things than older groups, so banks can highlight their trendy and youthful characteristics when promoting.

Second, this study shows that self-service quality plays a mediating role in the relationship between technological readiness and customer satisfaction. This is the key mechanism through which firms can improve customer satisfaction. Therefore, managers should consider the self-service quality when providing self-service technologies in the banking sector. A key factor in the use of self-service banking is the quality of service as perceived by customers. When both technological readiness and perceived self-service quality are high, banks experience high levels of customer satisfaction. Banks may spend too much time improving customers’ technology readiness. Based on the mediating effect of self-service quality, we find that banks achieve higher customer satisfaction when customers have a certain level of technology readiness, and the bank's e-service quality is high compared to when customers have a higher level of technology readiness but the bank offers lower e-service quality. Therefore, banks must be aware that improving service quality can enhance customer satisfaction and maintain a competitive advantage. Our study shows that each dimension (functionality, enjoyment, security/privacy, design, convenience, and customization) contributes differently to customer service quality, with enjoyment having the greatest impact on service quality. Therefore, self-service banking providers should promote a pleasant experience by involving customers in the design process and responding to their needs earlier than their competitors to enhance the quality of self-service banking.

Conclusions

In recent years, self-service banking has become increasingly common in Macau, with banks actively providing this medium of service because of its significant cost savings. While self-service banking is growing rapidly, customer perceptions and behaviors when using this technology have been explored in developed economies but not yet been done locally in Macao. Based on the existing literature (Lin and Hsieh 2006; Lin and Hsieh 2011; Pooya 2019), this study constructs, refines, and tests a multi-item SEM that can be used to measure the quality of self-service, technology readiness, and customer satisfaction of self-service banking simultaneously. An antecedent-consequence model of technology readiness for customer satisfaction was also developed, incorporating self-service quality as a mediator. Our results demonstrate the mediating role of self-service quality in the technology readiness–customer satisfaction relationship in self-service banking. Furthermore, no literature is available in the banking field regarding the impact of technology readiness on customer satisfaction when e-service quality acts as a mediator. Thus, this study contributes not only to the existing models in the literature but also to the current knowledge of the Macau population’s technology behavior in banking services.

This study focuses on the impact of technology readiness and service quality on customer satisfaction, and it is recommended that the scope of this study be expanded to include the influence of other variables, such as customer trust and customer loyalty, which could help bank managers better understand how to improve customer retention.

Although our study indicates that e-service quality has an important positive impact on customer satisfaction, we also need to recognize that the human aspects of service quality can play an important role in customer satisfaction. Lenka, Suar, and Moha (2009) found that the human aspects of service quality had a greater impact on customer satisfaction than the technical aspects of bank branches. Further studies are needed to determine the relationships among e-service quality, human service quality, and customer satisfaction.

Finally, delivery quality and outcome quality are integrated into service quality. However, some studies have shown that delivery and outcome qualities may have different impacts on customer satisfaction. Delivery quality refers to the customer’s interaction phase during the use of e-services, whereas outcome quality refers to the satisfaction of the e-customer after the service delivery process (Kao and Lin 2016). Therefore, it would be interesting to conduct further research to examine the impact of different service qualities on customer satisfaction.

References

- Amin, M. (2016), “Internet banking service quality and its implication on e-customer satisfaction and e-customer loyalty.” International Journal of Bank Marketing 34(3), 280–306. [CrossRef]

- Arasli, H., S. T. Katircioglu, and S. M. Smadi. A comparison of service quality in the banking industry some evidence from Turkish- and Greek-speaking areas in Cyprus. International Journal of Bank Marketing 2005, 23, 508–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boon-itt, S. (2015), “Managing self-service technology service quality to enhance e-satisfaction.” International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences 7(4), 373–391. [CrossRef]

- Chen, S and H. Chen. (2009), “Determinants of satisfaction and continuance intention towards self-service technologies.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 109 (9), 1248–1263. [CrossRef]

- Chang, H. H., Y. H. Wang, and W. Yang. (2009), “The impact of e-service quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty on e-marketing: Moderating effect of perceived value.” Total Quality Management 20(4), 423–443. [CrossRef]

- Felix, R. (2017), “Service quality and customer satisfaction in selected banks in Rwanda.” Journal of Business & Financial Affairs 6(1), 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Hankin, T. R. A review of scale development practices in the study of organizations. Journal of Management 1995, 21, 967–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao,T., and W. T. Lin. (2016), “The relationship between perceived e-service quality and brand equity: A simultaneous equations system approach.” Computers in Human Behavior 57(3), 208–218. [CrossRef]

- Lenka, U., D. Suar, and P. K. J. Moha. (2009), “Service quality, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty in Indian commercial banks.” The Journal of Entrepreneurship 18(1), 47–64. [CrossRef]

- Lin J., C. , and P. Hsieh. The role of technology readiness in customers’ perception and adoption of self-service technologies. International Journal of Service Industry Management 2006, 17, 497–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin J., C. , and P. Hsieh. Assessing the self-service technology encounters: Development and validation of SSTQUAL scale. Journal of Retailing 2011, 87, 194–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mummalaneni, V., M. Juan, and E. M. Kevin. Consumer technology readiness and e-service quality in e-tailing: What is the impact on predicting online purchasing? Journal of Internet Commerce 2016, 15, 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R. A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parasuraman, A. Technology readiness index (Tri): A multiple-item scale to measure readiness to embrace new technologies. Journal of Service Research 2000, 2, 307–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooya, A., M. A. Khorasani, and S. G. Ghouzhdi. (2019), “Investigating the effect of perceived quality of self-service banking on customer satisfaction.” International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 13(2), 263–280. [CrossRef]

- Purani, K. , and S. Sahadev. (2013), “Exploring the role of technology readiness in developing trust and loyalty for e-service.” In E-Marketing in Developed and Developing Countries: Emerging Practices, edited by H. El-Gohary and R. Eid, 291–303, Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Robertson, N, H. McDonald, C. Leckie, and L. McQuilken. (2016), “Examining customer evaluations across different self-service technologies.” Journal of Services Marketing 1(30), 88–102. [CrossRef]

- Shamdasani, P., A. Mukherjee, and N. Malhotra. (2008), “Antecedents and consequences of service quality in consumer evaluation of self-service internet technologies.” The Service Industries Journal (1), 117–138. [CrossRef]

- Ting, O. S., M. S. M. Ariff, N. Zakuan, Z. Sulaiman, and M. Z. M. Saman. (2016), “E-Service Quality, E-Satisfaction and E-Loyalty of Online Shoppers in Business to Consumer Market: Evidence form Malaysia.” In Materials Science and Engineering. Symposium conducted at the meeting of the 242nd Electrochemical Society, chaired by M.S. Whittingham, Atlanta, US. [CrossRef]

- Udo, G. J., K. K. Bagchi, and P. J. Kris. An assessment of customers’ e-service quality perception, satisfaction and intention. International Journal of Information Management 2010, 30, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, J. B. , and P. M. Bentler. (2003), ”Structural equation modelling.” Handbook of Psychology, 607–634.

- Vize, R., J. Coughlan, A. Kennedy, and F. E. Chadwick. (2013), “Technology readiness in a B2B online retail context: An examination of antecedents and outcomes.” Industrial Marketing Management 42, 909–918. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., K. K. F. So, and B. A. Sparks. (2017), “Technology readiness and customer satisfaction with travel technologies: A cross-country investigation.” Journal of Travel Research 56(5), 563–577. [CrossRef]

- Westjohn. S. A., M. J. Westjohn. S. A., M. J. Arnold, P. Magnusson, S. Zdravkovic, and X. J. Zhou. (2009), “Technology readiness and usage: A global-identity perspective.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 37, 250–265. [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V. A., A. Parasuraman, and A. Malhotra. (2002), “Service quality delivery through web sites: A critical review of extant knowledge.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 30(4), 362–375. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).