1. Introduction

The steadily growing proportion of those over the age of 60 from 12% to 22% by 2050 [

1] makes ageism a problematic social issue [

2]. Older persons are often stereotyped as incompetent, boring, slow, and fragile [

3]. Age segregation in many life domains (i.e., education, family, employment, and retirement) between young and older generations is considered a prominent cause for such views [

4].

In response to the devastating outcomes of age segregation, intergenerational encounters for bridging the gap between generations are constantly being constructed [

5]. While these encounters demonstrate effectiveness, they seem to be more efficient among adolescents and young adults than among older adults [

6]. Moreover, not all interventions correspond with the requirements that the interventions will be individualized, based on equal status relations, and on in-person intergenerational contact [

5], and include shared tasks [

7,

8]. In the present study we implemented these requirements and aimed to assess whether the shared performance of synchronized dance movements in dyads improves social bonding (interpersonal level) and intergenerational closeness (social level).

What are the social benefits of synchronous human movements? Interpersonal synchrony is defined as “coordinated temporal movements between two or more individuals” [

9](p. 123). To test the social effects of interpersonal synchrony, researchers manipulate auditory stimuli while comparing synchronous and asynchronous conditions. Synchronous dancing movements increased social bonding between participants, compared to asynchronous dancing [

10]. A common paradigm for the creation of asynchronous dancing movements, is the silent disco paradigm [

11]. In the current study this paradigm has been used and dancing movements were modified to a sitting position to ensure the safety of the older participants.

The application of synchronous manipulation, however, extends beyond dancing movements. Prior research demonstrated its effectiveness in fostering social bonding during mere walking and finger tapping. Participants directed to walk in synchrony felt more connected and trusted each other more than those who walked asynchronously [

12]. Tapping in synchrony with others resulted in higher ratings of affiliation with the experimenter compared to asynchronous tapping [

13]. Moreover, synchronized series of movements fostered various prosocial attitudes (such as closeness, perceived similarity, liking, affiliation, and trust), encouraged prosocial behaviors (such as cooperation; [

14], and increased social bonding with ingroup [

15] and out-group members [

16,

17]. Additionally, walking in synchrony with an out-group member decreased prejudice towards that out-group [

18]. Finally, qualitative research [

19] suggested that dance between adult granddaughters and their grandmothers can contribute to stronger intergenerational bonds.

Building on the established literature regarding the synchrony-bonding effect [

9,

20,

21,

22] we posit Hypothesis 1 (H1): Synchronized dyads will be associated with higher levels of social bonding with the dyadic partner in comparison to asynchronized dyads.

Openness, the trait of intellectual curiosity, imagination, and seeking out new experiences and new ideas [

23] is decreasing in older age [

24,

25,

26], and may be depicted by the shrinking social networks of family, friends, neighbors, and community members in old age [

27]. Social networks reach a peak at the age of 25 and decrease steadily after the age of 55 [

28]. Older persons are less likely to develop new relationships [

29], and focus on family and on fewer but deeper close relationships [

30,

31]. In contrast, young persons are more open to new experiences and diverse perspectives, often forming numerous social connections compared to older persons [

23]. Older persons, in contrast, also demonstrate decreased openness, potentially leading them towards appreciation for traditional norms [

32].

Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 2 (H2): Following any social encounter (whether with the in-age-group or with the out-group, whether synchronized or asynchronized), young adults, as compared with older adults, will report greater increase in perceived closeness between age groups.

Finally, in line with the previous research which demonstrated greater cooperation and social connection following synchronous vs asynchronous movements with out-group members [

16,

17,

33] we propose Hypothesis 3 (H3): Highest reported closeness between generations is expected among participants dancing in synchrony with an out-age-group member. A lesser degree of reported closeness between generations is expected among participants dancing in synchrony with an in-age-group member. The lowest level of reported closeness between generations is expected among participants dancing asynchronously, with an in-age-group or an out-age-group member.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample

A convenience sample, using a snowball sampling method via social media (e.g., Facebook, WhatsApp), of 168 community-dwelling Jewish Israeli older adults (M=72.33, age range: 65-90 years) and young adults, i.e., university students (M=27, age range: 20-45 years) from central and southern Israel was recruited. While there is some variation in the definition of young adulthood, it generally encompasses individuals between 18 and 45 years old [

34]. Although debated, in Western societies, 65 years is frequently used as the starting point of old age [

35]. Therefore, the present study focused on these two age ranges. Inclusion criteria were age, proficiency in Hebrew, and lack of physical and cognitive limitations (participants reported if they were diagnosed with physical or cognitive impairments). Twelve participants who did not meet these criteria were excluded. The final sample included 80 older adults, (M=72.33, SD = 5.83, 72.5 % women), and 88 young adults, (M=27, SD = 5.77, 70.5% women). In terms of education, 41.7% had less than full high school education, 17.3 % had full high school education, and 41.1% had higher education. In terms of marital status, 46.4% were married. Most of them reported good (41.1%) and very good health (47.6%), and the rest reported pretty good health (9.5%) and bad health (1.8%). One third (36.9%) defined their economic status as average, while over a half (54.2%) stated that their economic status is above-average, and the rest (9.5%) reported below-average economic status. In terms of religiosity, levels were almost evenly distributed between secular, traditional or religious (33.3%, 29.2%, 28% respectively), whereas the rest (9.5%) defined themselves as ultra-orthodox.

After recruitment, the participants were randomly assigned to one of six dyadic conditions, according to age-group affiliation (in-age-group vs. out-age-group) and synchrony (synchronous movements vs. asynchronous movements). Condition 1: young and older adult synchronous movements (N = 26); Condition 2: young and older adult asynchronous movements (N = 30); Condition 3: young and young synchronous movements (N = 34); Condition 4: young and young asynchronous movements (N = 32); Condition 5: older and older synchronous movements (N = 26) and Condition 6: older and older asynchronous movements (N = 20). The research received approval by Research Ethical Committee at the authors’ university (no. XXXX).

2.2. Procedure

Data was collected from March 2022 till February 2023 by the first author. A week after filling out a pre-questionnaire, using the Qualtrics survey platform, two participants, new to each other, met in the lab for an 11-minute joint activity. First, they watched an instruction video clip in which a dancer sitting on a chair performed four hands movements (adapted from [

10]). They were asked to mimic and memorize the sequence of the movements. Afterwards, they were seated on two chairs facing each other one-and-a-half-meter apart and listened separately to recorded instructions through individual earphones. Then they were requested to start moving according to the required sequence of the movements in response to the music on the earphones. The music, composed by the first author was a syncopated upbeat of percussion and drums. Participants were instructed to look at their partner and move their hands according to the recorded instructions and to the beat. At the synchronous condition both participants listened to a music at the same pace (110 Beats Per Minute) whereas at the asynchronous condition, they listened to the same music, but at a different pace (90/110BPM). The use of a different pace did not allow the movements of the participants to be aligned and thereby created asynchronous movements. The specific tempi were selected, following previous studies which estimated that the optimal tempo for the experience of groove is within a range of 107 to 126 BPM [

36,

37]. The lower tempo range was chosen to avoid participants’ hands fatigue. Afterward participants completed questionnaires and were debriefed. They were thanked and granted 15

$ for their time and effort.

2.3. Instruments

2.3.1. Social Bonding

Social bonding was assessed using items adapted from previous research [

12,

13,

14]. Participants rated their level of bonding with their dance partner on a scale ranging from 1="not at all" to 7="very much", in response to six questions (i.e., how enjoyable was dancing with the partner? how close did you feel? how much did you like the partner? how similar did you feel to the partner? how much did you trust the partner? how much would like to know the partner?). Items were averaged, with higher scores depicting higher social bonding. Overall reliability of the scale was very good (Cronbach’s alpha = .86).

2.3.2. Ingroup – Outgroup Overlap

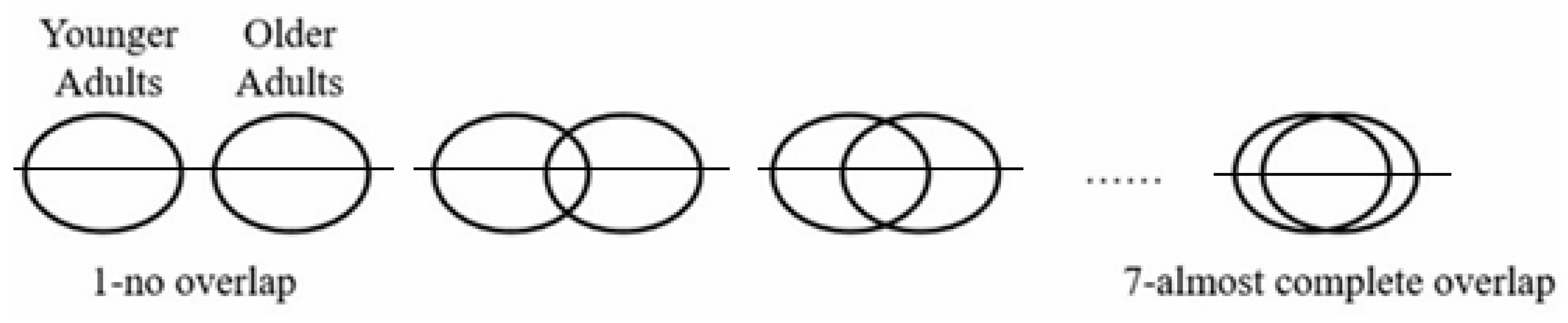

Ingroup - Outgroup Overlap [

38]: The scale is based on the Inclusion of the Other in the Self (IOS) [

39] which depicts two equal circles with increasing areas of overlap. It was designed as a way to depict perceived closeness between groups and also considers components such as teamwork and time together [

40]. These qualities of the IOS made it appropriate for measuring the level of perceived closeness between young and older adults (see also [

41]), who participated in a joint effort to synchronize their movements according to pace of music during an 11 min. interaction. The overlapping levels between the two groups which indicate closeness level were coded from 1 (no overlap) to 7 (highest overlap) between the two groups. Participants provided their evaluations twice (a week before and after the intervention). Higher scores depicted greater intergenerational closeness as shown in

Figure 1. They also completed three cover items: The overlap on the same scale of “secular” vs “religious”, “non-European origin” vs “European origin” ( “Mizrachi” vs “Ashkenazi” in Israeli terms), and “left” vs “right” (political stance).

2.4. Data Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed by SPSS 28. Preliminary comparisons of background characteristics were examined. Prior to testing the hypotheses, we examined differences across participants by means of age-group affiliation. Specifically, we applied the two-independent sample t-test for continuous or ordinal measurements, and the Chi-Square test of frequency distribution for the categorical or nominal variables. We found as expected higher health condition among the younger adults in comparison to the older adults (Mdifference=0.28, t(135.87)=2.15, p=.013, ES=.39), higher economic status among the older adults (Mdifference=0.28, t(166)=-7.30, p<.001, ES=-1.13), and higher religiosity level (Mdifference=0.28, t(142.45)=-2.22, p=.014, ES=-.34), among older adults. We did not find education differences between the older and the younger adults. In addition, the mean of the three baseline social closeness items was compared (IOS-social groups) and no difference was found between young and older adults (Mdifference=.28, t(166)=1.46, p=.15, ES=.19). Moreover, no difference was found when comparing the item measuring age-group social closeness between young and older adults (Mdifference=.114, t(166)=.53, p=.34, ES=.21). These comparisons resulted in no age group differences on average. In other words, both young and older participants showed similar perceived differences on average, see further explanation of these closeness measures in the next section. Altogether, these preliminary comparison results confirmed the random design of the experiment. We found women-men ratio to remain similar in both age groups (Pearson’s X(1)2=0.086, p=.769), and so was in-relationship versus not-in-relationship frequency difference (Pearson’s X(1)2=1.43, p=.232). These results led to minimizing further modeling framework to necessary background variables to control for possible confounding effects. Specifically, we kept health condition, economic status, religiosity, and perceived closeness, beyond synchronization, congruency (i.e., in/out-age-group), and age-group affiliation (i.e., 20-45/65-90), as controls. Note that all comparisons were applied on the pre-intervention data. Additionally, the research data did not consider the gender composition of the dyads, as the limited sample size did not allow control over this variable.

To test the three hypotheses, we performed a Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) modeling approach to integrate the dyadic structure of the experiment. Specifically, participants operated the various assignments in pairs, thus, assigning two sources to the total variance: variation across individuals’ measurements (level one data) and variation across dyads (level two data), where the latter was expressed in the dyadic random intercept (the working correlation matrix; [

42]. The Wald's X

2 test was used to assess between-dyad significant differences, e.g., synchronized versus asynchronized dyads, in-age-group versus out-age-group dyads. Predicted marginal means, i.e., sub-group means were calculated and compared. To complete the model, personals’ characteristics were added to the model, e.g., health condition, economic status, religiosity, and perceived closeness.

3. Results

To test the first hypothesis, a GEE model was constructed with social bonding as the post-intervention outcome. The explanatory set included the dyadic synchronous versus asynchronous dyads and the in-age-group versus out-age-group dyads. Other individual’s level indicators were age-group and health condition, economic status, and religiosity. The synchronization condition was found to affect social bonding (b = 0.51,

p = .014), such that the synchronized cases were associated with higher levels of social bonding with the dyadic partner in comparison to asynchronized cases (predicted means: Msync = 3.52, 95%CI [3.19,3.85]; Masync = 3.01, 95%CI =[2.78,3.25]). No other independent effects were found to be significant. These model results lend support to the first hypothesis (

Table 1).

A similar GEE model was built to analyze the change in intergeneration closeness from pre-intervention to post-intervention.

Table 2 provides GEE model results for the H2 test. We looked at the age- group effect on the change in perceived age closeness, controlled by the perceived closeness at pre-intervention. Results lend clear support to H2, that is, younger adults experience greater and positive change in age closeness perception in comparison to older adults (b=0.69,

p < .001; Myounger = 0.62, se = 0.13, 95%CI =[0.36, 0.88]; Molder = -0.07, se = 0.16, 95%CI =[-0.37, 0.24]). In addition, the pre-intervention closeness was negatively associated with the change, regardless participant’s age (b = -0.56,

p < .001), representing a regression to the mean as explained above.

To test the moderation hypothesis (H3), we tested a series of two-way interactions as well as a composite three-way interaction. These interaction effects were tested beyond the main effects of the above factors, and the other covariates that were included in the previous model.

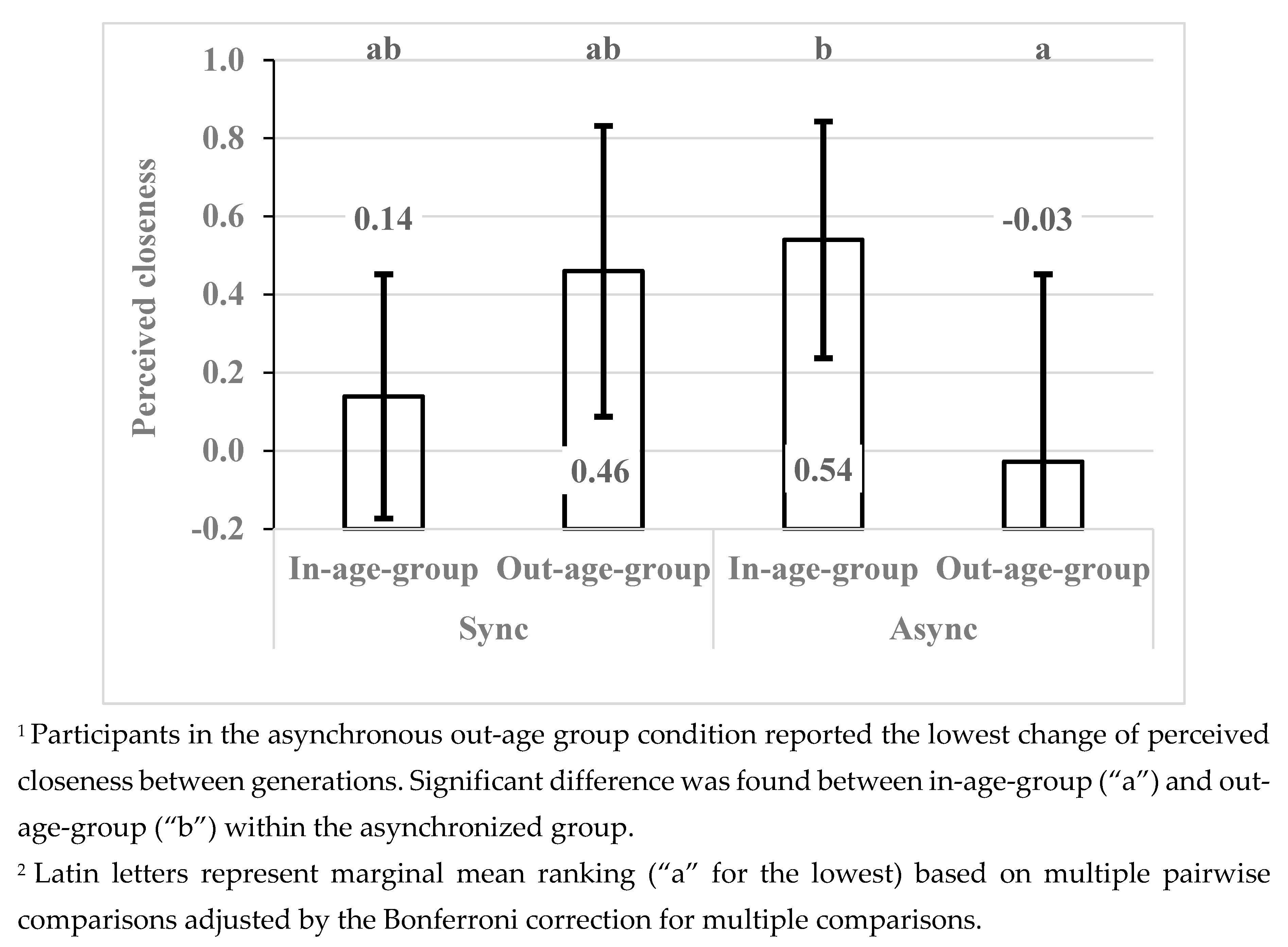

Table 3 shows that synchronization interacted with age-congruency to affect the change in perceived closeness (Wald=5.40,

p = .020). An interaction decomposition is presented in

Figure 2. Each bar represents the marginal mean of a subgroup, where Latin letters are assigned for marginal group ranking. The lowest level of change in perceived closeness was found among participants from the asynchronized-out-age-group condition (Mincongruency = -0.03, 95%CI= [-0.50, 0.45]; “a”). However, both in-age-group vs out-age-group means within the synchronized category did not differ from the lowest subgroup mean as well as from the asynchronized in-age-group, on average. The main difference was found between in-age-group and out-age-group within the asynchronized groups, on average (Mcongruency = 0.54, 95%CI= [0.23, 0.84]; “b”). On average, a negative or an overall mean reduction of perceived closeness was found among the out-age-group asynchronized subgroup, while the means value of perceived closeness was positive for the rest of the research respondents. H3 was supported by the interaction but findings are contradictory. Only the out-age-group asynchronized subgroups had a negative change, in comparison to the other three subgroups, which improved their closeness perceptions.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to examine a way to increase intergenerational social bonding and intergenerational closeness through dance movements. The intervention consisted of a short movement activity (11 minutes), in synchrony or in asynchrony, between two partners who had no prior acquaintance, in which 84 dyads (old with young, young with young or old with old) took part. The study examined the effect of synchronicity, age-group, and the age structure of a dyad (in- or out-age-group) on the social bonding toward the partner (interpersonal level), and on the degree of perceived closeness between generations (social level). Synchronous dance movements resulted in greater social bonding with the partner. Young adults (aged 20-45) reported a greater increase in closeness between generations, compared to older adults (aged 65-90). Unexpectedly, increase in closeness between generations was reported among participants who danced out of sync with the in-age-group, compared to those who danced out of sync with the out-age-group.

The first finding of the study resonates with numerous research studies which established the social benefits arising from the performance of synchronized movements (e.g., [

9]). Synchronized movements created a sense of camaraderie both within in-groups and out-groups ([

15,

16,

17,

18], which was termed “social glue”. Synchrony promoted social bonds among toddlers [

43], children [

44], adolescents [

45], adults [

10], and even toward virtual avatars [

46]. Yet, our study is the first to explore the influence of movement synchronization on social bonding in an intergenerational context. Participants allocated in the in-age-group dyads (young-young, old-old) and in the out-age-group dyads (young-old) reported greater social bonding with their dancing partners when the dyadic movements were synchronized. It is important to note that the score of social bonding was based on the mean of items for each dyad. Dyads who performed synchronized as opposed to asynchronized dance movements reported greater social bonding because they enjoyed, felt closer, found similarity, liked, trusted their partner, and were keen to know the partner. Such an interpretation can be supported by a study which found that a ‘mirror game’, in which dyads mimicked each other’s movements, increased the level of attention, enjoyment, and responsiveness to the partner [

47]. Moreover, this effect of 11-min. synchronous movements on social bonding was so robust that it included both in-age-group and out-age-group dyads. In other words, the mere synchronous movements while sitting for 11 minutes strengthened interpersonal bonding within and across age groups.

Such processes, which includes perception-action coupling, are described as breaking down the ‘boundaries’ of the self and enhancing the sense of overlap between self and the partner, so that the perception of similarity between the two increases [

48]. In this context, it can be reiterated that walking synchronously with a member of an outgroup (belonging to a socially marginalized group) led to a decrease in prejudice towards the outgroup as a whole, compared to walking asynchronously [

18]. The strong impact of synchronized movement on the individual suggests that future studies will examine if synchronized movements can also reduce age stereotypes and decrease ageism.

As to the effect of asynchronized movement on social bonding, it is possible that the ‘boundaries’ of the self and the partner among dyads who moved out of synchrony became thicker. When participants noticed that despite their efforts, their movements are still not coordinated, they gave up, stopped investing their attention in mimicking their partner and started to focus on their own movements. Thus, non-synchronized participants demonstrated less social bonding to the partner. Later, upon discussing hypothesis 3, we will elaborate more about the psychological experience of these participants.

Our findings also confirm the second research hypothesis regarding the propensity of young adults to increase perceived closeness between generations, which was not expected from the older adults. Following the intervention, young adults probably exhibited positive ‘social flexibility’ regardless of the synchrony condition or the age composition of the dyad and reported feeling greater closeness between young and older adults. Why, then, did young people demonstrate greater social flexibility? It should be noted that the average age of the young adults who participated in the experiment was 27, and most of them were university students, whose lifestyle invites exposure to many people and to new and diverse ideas. This finding is also consistent with a systematic review that examined the effectiveness of 63 intergenerational intervention programs of over 6100 participants and found them more effective for young adults [

6]. As to the lack of change in intergenerational closeness among older adults, it may be attributed to the decline in social networks [

29], and in openness which appear with advanced age [

24].

The significant interaction effect of age-group X synchronicity on intergenerational closeness was in opposite to hypothesis 3. It indicated that participants who danced with their in-age-group partner asynchronously reported increased closeness between generations (see the positive value in column “b”;

Figure 2) compared to those who danced with their out-age-group partner asynchronously. Ostensibly, asynchronous movement may cause increased social distancing, since it demonstrates unsuccessful social interaction, that creates a kind of ‘psychological buffer’ between the participants. Yet, intergroup dynamics theories may provide an explanation for the findings. Social Identity Theory [

49] posits that individuals seek positive distinctiveness for their in-groups by comparing them favorably with other groups, a phenomenon termed the ingroup favoritism. Individuals tend to favor their ingroup due to the motivation to maintain positive self-esteem in an intergroup context (“we are better than them”). In the context of the present study, it is possible that the asynchronous movements with an in-age-group partner (young with young and old with old) reduced the favoritism for the in-age-group, because it was frustrating. When participants noticed that in spite of their efforts, their movements are still not aligned with members of their in-age-group, the effect of perceived similarity to people of their age-group diminished which led to a mitigation of the ingroup favoritism bias. Thus, the decrease in the ingroup favoritism bias maintained the positive value of the out-age group, which was reflected in the report of increased closeness between generations.

As expected, asynchronous movements with the out-group increased the perceived distance between generations (the negative value in column “a”;

Figure 2). It is possible that movement limitations which were apparent among older adults, who according to the instructions, tried in vain in the asynchronous situation to synchronize with their young partner, led the young participants to focus on negative aging cues. Due to their failure to achieve synchronous movements in the asynchronous condition, older persons could be portrayed by young adults as clumsy and disabled. The older persons in these asynchronous dyads may have sensed the discomfort that their young partners could experience due to the asynchrony of the dance movements and felt frustrated because they had troubles in adjusting to their young partners and could attribute these difficulties to their advanced age. In sum, it is possible that intergenerational dancing with the out-group that was not synchronized led all participants to perceive intergenerational distance, whereas asynchronized intergenerational dancing with the in-age-group could mitigate ingroup favoritism. To further elucidate these findings, future research should replicate this study with additional outcome measures. In order to support the explanation of bodily inferiority in the asynchronized condition, a measure of body image can be used. To validate the argument that an asynchronized intergenerational dancing with the in-age-group can mitigate ingroup favoritism and thereby create intergenerational closeness, a measure of in-age group closeness (e.g., in-generational closeness measured by inclusion of the ingroup in the self; [

50]) can be used. Moreover, in order to examine the effect of greater intergenerational closeness among younger adults, future studies can also add a measure of openness.

The findings of the current study should be discussed while considering its limitations. First, since it was done in the lab it lacks general validity. Future studies should examine intergenerational dance in communities or in ceremonial contexts (e.g., weddings or festivals), using changes of tempo or dynamics that may produce creative physical interactions (e.g., XXX). Second, future studies need to recruit larger, homogeneous, and random samples. In this regard, the relatively small number of participants in each of the six experimental conditions, and the high percentage of women, did not allow to examine the effect of the dyad structure in terms of gender. However, this problem also appears in other studies (see [

10,

12,

13]). Third, due to the complexity of the study design in similar to other studies it did not measure the effect of alternative activities within dyads (e.g., conversations, working together on a shared cooperative task; see [

10,

12,

13]). Fourth, the study did not examine the stability of the effects over time (e.g.,[

51]). Finally, measuring physiological measures which signify synchronization (e.g., inter-beat intervals of heartbeats to test synchronization between participants, see [

52]) or closeness (e.g., saliva samples to measure oxytocin secretion) can add understanding to the mediating physiological mechanisms of synchronization leading to intergenerational closeness.