Submitted:

30 April 2024

Posted:

01 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Galenic Question

3. The Likely Writings of Galen–1

3.1. De Sanitate Tuenda (Text 21)

3.2. De Placitis Hippocratis et Platonis (text 15) and Administrationes Anatomicae (Text 17)

3.3. De Naturalibus Facultatibus (Text 18)

3.4. De Usu Partium (Text 7)

3.5. De Atra Bile (Text 28)

3.6. De Elementis Secundum Hippocratem and De Temperamentis (Texts 26 and 27)

3.7. In Hippocratis Librum Primum Epidemiarum Commentarii (Text 54)

3.8. Protrepticus (Text 3)

3.9. De Theriaca ad Pisonem (text 4)

3.10. De Methodo Medendi (Text 8)

3.11. De Sectis (Text 20)

3.13. Conclusion

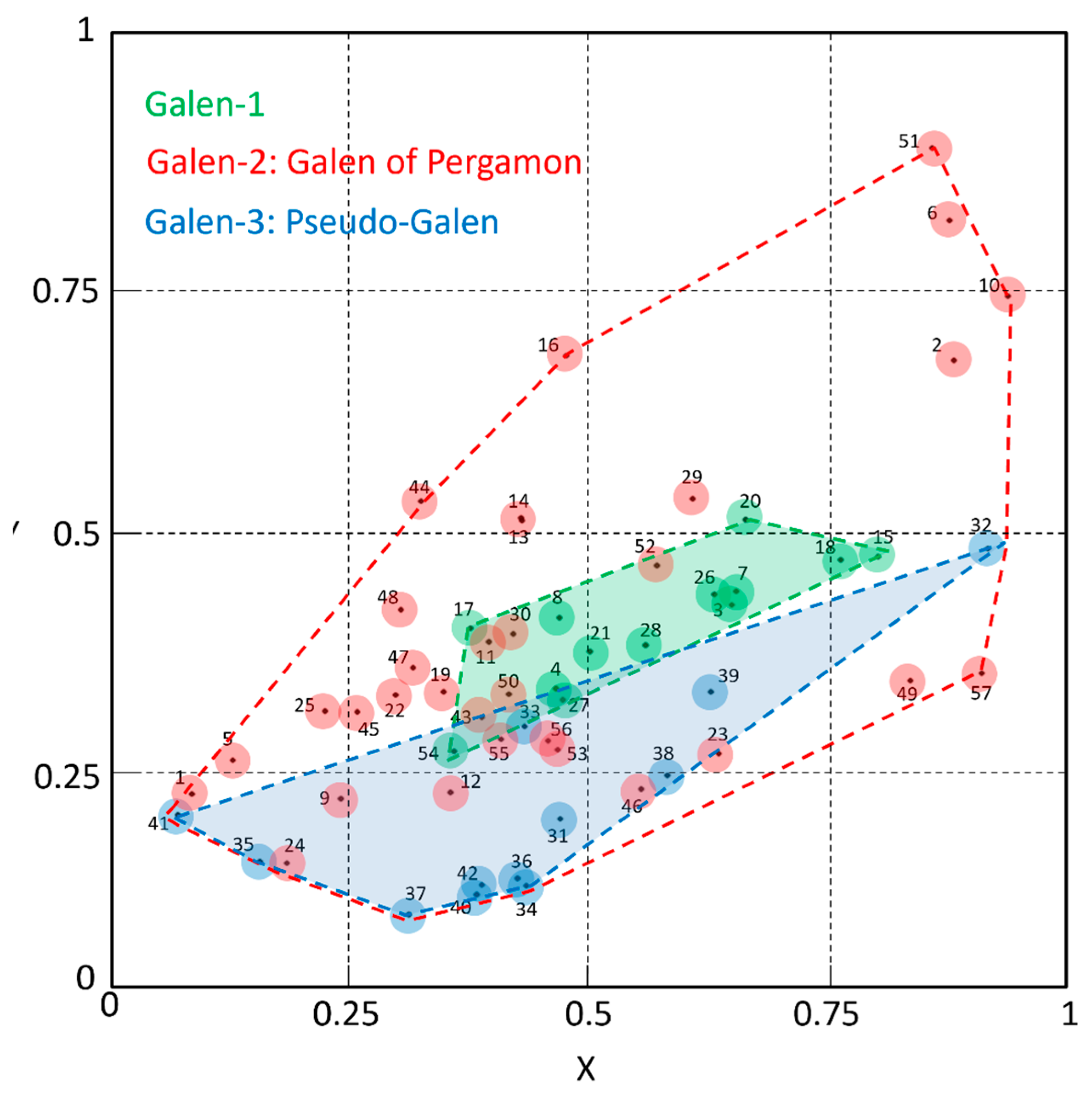

4. Deep−Language Parameters and Vector Representation of Texts

- a)

- The texts allegedly attributed to Galen–1 fall into the region delimited by the dashed green line.

- b)

- The texts attributed to Galen–2 fall into the region delimited by the dashed blue line.

- c)

- The texts allegedly attributed to Galen–3 (Pseudo Galen) fall in the large region delimited by the red dashed line which includes all texts.

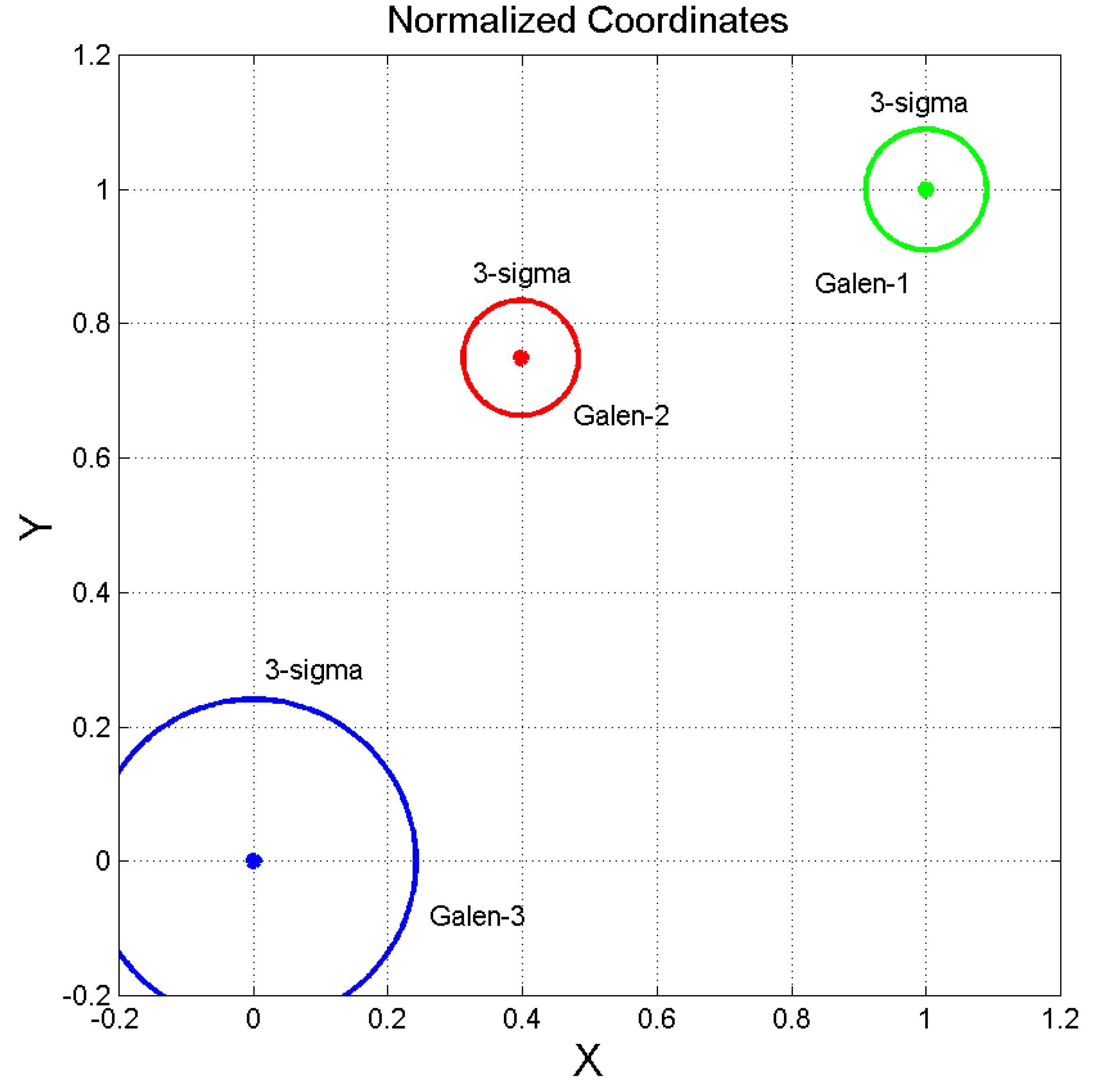

5. Deep−Language Parameters of Galen–1, Galen–2 and Galen–3

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fichtner, G. Corpus Galenicum. Verzeichnis der galenischen und pseudogalenischen Schriften, Erw. und verb. Ausg., Tübingen 2010.

- Scarborough, J. The Galenic Question. Sudhoffs Archiv 1981, 65, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Matricciani, E. Deep Language Statistics of Italian throughout Seven Centuries of Literature and Empirical Connections with Miller’s 7∓ 2 Law and Short-Term Memory. Open Journal of Statistics 2019, 9, 373–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E.; De Caro, L. A Deep-Language Mathematical Analysis of Gospels, Acts and Revelation. Religions 2019, 10, 257–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Capacity of Linguistic Communication Channels in Literary Texts: Application to Charles Dickens’ Novels. Information 2023, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Linguistic Communication Channels Reveal Connections between Texts: The New Testament and Greek Literature. Information 2023, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argenterio, G. Ioannis Argenterii Pedemontani in artem medicinalem Galeni, commentarii tres. Ex Officina Torrentiniana: in Monte Regali, 1566.

- Tiraquellus, A. (Tiraqueau, A.). Commentarii de nobilitate et iure primigeniorum. Apud Gulielmum Rovillium: Lugduni, 1584.

- Migne, J.P. Patrologiae Graecae Tomus CXV, Parisiis, 1899.

- Sordi, M. I ‘nuovi decreti’ di Marco Aurelio contro i Cristiani. Studi Romani 1961, 9, 365–378. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli, A. Galen’s Early Reception (Second-Third Centuries). In Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Galen; Bouras-Vallianatos, P. and Zipser, B., Eds. Brill: Leiden-Boston, 2019; 11-37.

- Mewaldt, J. Galenos über echte und unechte Hippocratica. Hermes 1909, 44, 111–134. [Google Scholar]

- Walzer, R. Galen on Jews and Christians. Oxford University Press: London, 1949.

- Nutton, V. Galen ad multos annos. Dynamis. Acta Hisp. Med. Sci. Hist. Illus. 1995, 15, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mattern, S. P. Galen and the Retoric of Healing. Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore, 2008.

- Gill, C., Whitmarsh, T. and Wilkins J. (Eds.). Galen and the World of Knowledge. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2009.

- Clivaz, C. Peut-on parler de posture littéraire pour un auteur antique ? Paul de Tarse, Galien et un auteur anonyme. Contextes 2011, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Totelin, L.M.V. And to end on a poetic note: Galen’s authorial strategies in the pharmacological books. Studies in History and Philosophy of Science 2012, 43, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbou Hershkovits, K.; Hadromi-Allouche, Z. Divine Doctors: The Construction of the Image of Three Greek Physicians in Islamic Biographical Dictionaries of Physicians. Al-Qantara 2013, 34, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Favaretti Camposampiero, M. and Scribano, E. Eds. Galen and the Early Moderns. Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, 2022.

- Vegetti, M. Historiographical Strategies in Galen’s Physiology. In Van Der Eijk, P. J. Ancient Histories of Medicine. Brill: Leinden - Boston - Köln, 1999, 383-395.

- Boudon-Millot, V. Galeno di Pergamo. Un medico greco a Roma. Carocci Editore: Firenze, 2016 (First Edition Paris, 2012).

- Temkin, O. Galenism. Rise and Decline of a Medical Philosophy. Cornell University Press: Ithaca and London, 1973.

- Pietrobelli, A. (ed.) Contre Galien. Critiques d’une autorité médicale de l’Antiquité à l’âge moderne. Honoré Champion: Paris, 2020.

- Ibn Juljul. Libro de la explicación de los nombres de los medicamentos simples tomados del Libro de Dioscórides. Ed. y trad. de I. Garijo Galán. Universidad de Córdoba: Córdoba, 1992.

- Vanoli, A. Le philosophe et le volcan. La mémoire des savants de l’Antiquité dans la Sicile musulmane. Cahiers de Civilisation médiévale 2012, 55, 245–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musitelli, S. Da Parmenide a Galeno. Tradizioni classiche e interpretazioni medievali nelle biografie dei grandi medici antichi. Atti della Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, Classe di Scienze Morali, Memorie 1984, 28, 215–276. [Google Scholar]

- Nutton, V. Galen in the Eyes of his Contemporaries. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 1984, 58, 3–315. [Google Scholar]

- Carandini, A. L’economia italica fra tarda repubblica e medio impero considerata dal punto di vista di una merce: il vino. In Amphores romaines et histoire economique : dix ans de recherche ; Actes du Colloque de Sienne. École Française de Rome: Roma, 1989; 505-521.

- Jacob, C. Ateneo, o il dedalo delle parole. In I Deipnosofisti - I dotti a banchetto; Ateneo; Salerno Editrice: Roma, 2001; Volume 1, XI-CXVI.

- Manetti, D. Galenus. In Commentaria et Lexica Graeca in Papyris Reperta. Pars I Vol. 2 Fasc. 6 Galenus-Hipponax. De Gruyter : Berlin, 2019 ; 3-4.

- Manetti, D. Un nuovo papiro di Galeno. In Studi di Letteratura Greca. Ricerche di Filologia Classica I. AA.VV. Giardini: Pisa 1981, pp. 115–123.

- Groag, E. s.v. “Flavius Boethus”, in Prosopographia Imperii Romani saec. I. II. III, pars III, De Gruyter: Berolini et Lipsiae, 1943, p. 140, n. 229.

- Solin, H. Die Griechischen Personennamen in Rom. Ein Namenbuch, I-II. De Gruyter: Berlin-New York, 2003.

- Alexandru, S. Critical Remarks on Codices in which Galen Appears as a Member of the Gens Claudia. Mnemosyne 2021, 74, pp. 553–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marasco, G. I medici di corte nell’impero romano: prosopografia e ruolo culturale. Prometheus 1998, 24, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Vegetti, M. Nuove prospettive su Galeno. Méthexis 2011, 24, pp. 185–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparetti, D. (a cura di). Papiri Greco-Egizi. Vol. II. Papiri Fiorentini. Papiri Letterari ed Epistolari. Hoepli: Milano, 1908; pp. 34–38.

- Manfredi, M. P. Flor. 115. Studi Italiani di Filologia Classica 1974, 46, pp. 154–184. [Google Scholar]

- Manetti, D. Tematica filosofica e scientifica nel papiro fiorentino 115. Un probabile frammento di Galeno In Hippocratis De Alimento. In Studi su papiri greci di logica e medicina. Olschki Editore: Firenze, 1985, pp. 173–212.

- Abdullah Abou-Aly, A. M. The medical writings of Rufus of Ephesus. Thesis of Ph.D., University College: University of London 1992.

- Kühn, K. G. Claudii Galeni Opera Omnia, Voll. I-XX, Officina Libraria Car. Cnoblochii, Lipsiae, 1821-1833.

- Fabricius, J. A. Bibliothecae Graecae volumen tertium decimum quo continetur Elenchus Medicorum Veterum… Sumptu Th. Ch. Felgineri: Hamburgi, 1726; pp. 163–167.

- Petit, C. Galien de Pergame ou la Rhétorique de la Providence. Médecine, littérature et pouvoir à Rome. Brill: Leiden - Boston, 2018.

- Groag, E. “C. Calpurnius Piso”, in Prosopographia Imperii Romani saec. I. II. III, pars II, De Gruyter: Berolini et Lipsiae, 1936, pp. 55–56, n. 284.

- Hölzel-Ruggiu H. (Ed.). Der Wolfenbütteler “Rapularius”. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Quellen zur Geistesgeschichte des Mittelalters, Band 17. Hahnsche Buchhandlung: Hannover, 2002; pag. 360.

- Kibre, P.; Kelter, I.A. Galen’s Methodus medendi in the Middle Ages. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences 1987, 9, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Matricciani, E. A Mathematical Structure Underlying Sentences and Its Connection with Short-Term Memory. AppliedMath 2024, 4, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricciani, E. Readability Indices Do Not Say It All on a Text Readability. Analytics 2023, 2, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papoulis, A. Probability & Statistics; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1990.

| Latin title of text written in Greek | Date of writing (AD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Ars medica | 16171 | 755 | After 193 |

| 2. Quod animi mores | 8532 | 180 | After 193 |

| 3. Protrepticus = Adhortatio ad artes addiscendas | 5143 | 151 | After 193 |

| 4. De theriaca ad Pisonem | 13069 | 509 | Either 145–150 or 204–211 |

| 5. De constitutione artis medicae | 11977 | 519 | After 193 |

| 6. De libris suis | 6246 | 125 | After 193 |

| 7. De usu partium | 194,985 | 5845 | First book in 162–166; All others in 169–176 |

| 8. De methodo medendi | 157,730 | 5199 | Books I–VI after 173; Books VII–XIV after 193 |

| 9. De ossibus ad tirones | 6930 | 316 | 169–180 |

| 10. De victu actenuante | 6496 | 127 | 169–180 |

| 11. De symptomatum causis | 29412 | 964 | 169–180 |

| 12. De simplicium medicamentorum | 133,996 | 6452 | Books I–VIII in 169–180; Books IX–XI in 193 |

| 13. De foetum formatione | 7714 | 210 | After 193 |

| 14. De differentiis febrium | 20905 | 585 | 169–180 |

| 15. De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis | 95059 | 2707 | Books I–VI in 162–166; Books VII–X 169–176 |

| 16. De locis affectis | 69870 | 1548 | After 193 |

| 17. Administrationes anatomicae, books 1–9 = De anatomicis administrationibus | 80244 | 2577 | Second version after 189 |

| 18. De naturalibus facultatibus | 32603 | 927 | 169–180 |

| 19. De uteri dissectione | 3248 | 114 | In 145–149; re–elaborated in 166 |

| 20. De sectis | 6264 | 165 | 165 ca |

| 21. De sanitate tuenda | 67315 | 2259 | 169–186 |

| 22. De pulsuum differentiis = De differentia pulsuum | 42810 | 1593 | 176–192 |

| 23. De alimentorum facultatibus | 44930 | 1854 | Either in 169–180 or in 180–192 |

| 24. De pulsibus | 5975 | 331 | 162–166 |

| 25. De motu musculorum | 14719 | 552 | 169–180 |

| 26. De elementis secundum Hippocratem = De elementis ex Hippocrate | 13463 | 420 | 169–180 |

| 27. De temperamentis | 27715 | 1008 | 169–180 |

| 28. De atra bile | 6275 | 209 | After 180 |

| 29. De animi cuiuslibet peccatorum dignotione et curatione | 6451 | 167 | 179–189 |

| 30. De propriorum animi cuiuslibet affectuum dignotione et curatione | 8346 | 272 | 179–189 |

| 31. PG De causa affectionum | 3341 | 164 | After Galen of Pergamum’s death |

| 32. PG An animal sit quod est in uter | 3717 | 102 | “ |

| 33. PG De fasciis liber | 8063 | 319 | “ |

| 34. PG In Hippocratis de humoribus liber | 1682 | 112 | “ |

| 35. PG Introductio sive medicus | 18851 | 1066 | “ |

| 36. PG Prognostica de decubitu | 6455 | 382 | “ |

| 37. PG De urinis | 3824 | 246 | “ |

| 38. PG De urinis ex Hippocrate | 2962 | 131 | “ |

| 39. PG De victus ratione in morbis acutis | 5534 | 200 | “ |

| 40. PG De historia philosophica | 11150 | 716 | “ |

| 41. PG De optima secta ad Thrasybulum | 17448 | 863 | “ |

| 42. PG De affectuum renibus insidentium = De renum affectibus | 8183 | 474 | “ |

| 43. De causis morborum | 6081 | 228 | 169–180 |

| 44. De plenitudine | 11079 | 295 | 169–180 |

| 45. De tremore | 9108 | 351 | 169–180 |

| 46. De tumoribus | 4225 | 188 | 169–180 |

| 47. De inaequali intemperie | 3157 | 114 | 162–166 |

| 48. De difficultate respirationis | 31860 | 1026 | 169–180 |

| 49. De crisibus | 33729 | 1190 | 169–180 |

| 50. De diebus decretoriis | 27296 | 987 | 169–180 |

| 51. Institutio logica | 8571 | 150 | After 193 |

| 52. In Hippocratis de natura hominis commentarii | 24536 | 727 | 180–192 |

| 53. In Hippocratis prorrheticum commentari | 45654 | 1875 | 180–192 |

| 54. In Hippocratis librum primum epidemiarum commentarii | 38842 | 1645 | 169–180 |

| 55. In Hippocratis librum III epidemiarum commentarii | 41315 | 1715 | 180–192 |

| 56. In Hippocratis librum VI epidemiarum commentarii | 76820 | 3087 | 180–192 |

| 57. De musculorum dissectione | 14763 | 510 | 169–180 |

| 3. Protrepticus. 4. De Theriaca ad Pisonem. 7. De usu partium. 8. De methodo medendi. 15. De placitis Hippocratis et Platonis. 17. Administrationes anatomicae, books 1–9. 18. De naturalibus facultatibus. 20. De sectis. 21. De sanitate tuenda. 26. De elementis secundum Hippocratem. 27. De temperamentis. 28. De atra bile. 54. In Hippocratis librum primum epidemiarum commentarii. |

| 1. Ars medica 2. Quod animi mores 5. De constitutione artis medicae 6. De libris suis 9. De ossibus ad tirones 10. De victu actenuante 11. De symptomatum causis 12. De simplicium medicamentorum 13. De foetum formatione 14. De differentiis febrium 16. De locis affectis 19. De uteri dissectione 22. De pulsuum differentiis = De differentia pulsuum 23. De alimentorum facultatibus 24. De pulsibus 25. De motu musculorum 29. De animi cuiuslibet peccatorum dignotione et curatione 30. De propriorum animi cuiuslibet affectuum dignotione et curatione 43. De causis morborum 44. De plenitudine 45. De tremore 46. De tumoribus 47. De inaequali intemperie 48. De difficultate respirationis 49. De crisibus 50. De diebus decretoriis 51. Institutio logica 52. In Hippocratis de natura hominis commentarii 53. In Hippocratis prorrheticum commentari 55. In Hippocratis librum III epidemiarum commentarii 56. In Hippocratis librum VI epidemiarum commentarii 57. De musculorum dissectione |

| Reference number of Table 1 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 22.34 | 6.05 | 4.99 | 3.74 |

| 2 | 48.94 | 10.87 | 4.99 | 4.57 |

| 3 | 34.20 | 9.60 | 5.14 | 3.62 |

| 4 | 29.01 | 8.41 | 5.20 | 3.53 |

| 5 | 24.27 | 6.20 | 5.04 | 4.00 |

| 6 | 56.85 | 10.29 | 5.22 | 5.75 |

| 7 | 35.05 | 9.68 | 5.02 | 3.70 |

| 8 | 33.11 | 8.32 | 5.10 | 4.07 |

| 9 | 22.45 | 7.28 | 4.95 | 3.12 |

| 10 | 52.82 | 11.15 | 5.00 | 4.78 |

| 11 | 31.58 | 7.86 | 5.08 | 4.09 |

| 12 | 22.98 | 8.00 | 5.09 | 2.88 |

| 13 | 38.72 | 7.75 | 5.08 | 5.05 |

| 14 | 38.53 | 7.70 | 5.16 | 5.06 |

| 15 | 37.32 | 10.69 | 5.01 | 3.55 |

| 16 | 47.97 | 7.53 | 5.18 | 6.42 |

| 17 | 32.41 | 7.79 | 4.93 | 4.22 |

| 18 | 37.13 | 10.47 | 4.94 | 3.59 |

| 19 | 28.82 | 7.89 | 4.78 | 3.68 |

| 20 | 39.28 | 9.62 | 5.00 | 4.11 |

| 21 | 31.27 | 8.65 | 5.12 | 3.66 |

| 22 | 28.37 | 7.29 | 5.07 | 3.95 |

| 23 | 25.58 | 9.91 | 5.05 | 2.60 |

| 24 | 18.66 | 6.97 | 5.08 | 2.69 |

| 25 | 27.30 | 6.83 | 5.00 | 4.05 |

| 26 | 34.93 | 9.68 | 4.82 | 3.67 |

| 27 | 28.52 | 8.73 | 4.90 | 3.32 |

| 28 | 31.75 | 9.04 | 5.18 | 3.49 |

| 29 | 40.13 | 8.86 | 5.37 | 4.59 |

| 30 | 32.14 | 8.02 | 5.11 | 4.03 |

| 31 | 21.68 | 9.01 | 4.91 | 2.40 |

| 32 | 38.00 | 11.52 | 4.99 | 3.29 |

| 33 | 26.81 | 8.32 | 5.13 | 3.32 |

| 34 | 17.77 | 8.84 | 5.05 | 1.96 |

| 35 | 18.60 | 6.65 | 5.18 | 2.91 |

| 36 | 18.13 | 8.77 | 4.99 | 2.10 |

| 37 | 15.96 | 8.13 | 4.91 | 2.01 |

| 38 | 24.26 | 9.59 | 5.02 | 2.60 |

| 39 | 29.13 | 9.63 | 5.17 | 3.05 |

| 40 | 17.00 | 8.24 | 5.39 | 2.08 |

| 41 | 21.02 | 5.86 | 5.19 | 3.63 |

| 42 | 17.72 | 8.52 | 5.00 | 2.12 |

| 43 | 27.27 | 8.01 | 5.11 | 3.43 |

| 44 | 39.20 | 6.80 | 5.09 | 5.88 |

| 45 | 27.34 | 7.08 | 5.03 | 3.88 |

| 46 | 23.39 | 9.39 | 5.10 | 2.51 |

| 47 | 29.91 | 7.33 | 5.04 | 4.23 |

| 48 | 33.12 | 7.00 | 5.13 | 4.79 |

| 49 | 30.05 | 11.13 | 5.07 | 2.75 |

| 50 | 28.70 | 8.18 | 5.06 | 3.56 |

| 51 | 61.17 | 10.19 | 4.98 | 6.19 |

| 52 | 36.44 | 9.06 | 4.96 | 4.10 |

| 53 | 25.47 | 8.51 | 5.32 | 3.04 |

| 54 | 25.22 | 7.79 | 5.24 | 3.28 |

| 55 | 26.04 | 8.13 | 5.23 | 3.22 |

| 56 | 26.05 | 8.56 | 5.13 | 3.07 |

| 57 | 30.65 | 11.72 | 4.96 | 2.63 |

| Author | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Galen–1 | 33.521 (0.213) | 9.333 (0.043) | 5.032 (0.005) | 3.6621 (0.024) |

| Galen–2 | 30.246 (0.251) | 8.180 (0.035) | 5.104 (0.004) | 3.7866 (0.032) |

| Galen–3 | 21.377 (0.464) | 7.761 (0.124) | 5.149 (0.017) | 2.8518 (0.059) |

| Author | 1–sigma radius | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Galen–1 | 41.724 | ||

| Galen–2 | |||

| Galen–3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).