1. Introduction

Investment decisions are largely affected by investors' choices and actions based on available information. These have strong impacts on companies’ performances which in turn shape economic narratives Barberis and Odean (1998). The economic theory suggests that rationality based on symmetric information are prerequisite for optimal investment decisions. Nevertheless, in real life, investors’ psychology may contradict these theoretical assumptions. Perhaps, some social factors and emotions explain this contradiction in the form of market bubbles Thaler and Sunstein (2008). Indeed, this directly affects capital allocation and investment choices (Barberis and Odean, 1998; Thaler and Sunstein, 2008).

The theory of behavioural finance suggests that social influence plays a significant role in herding which arises from various psychological factors (e.g., the desire to conform, fear of missing out; FOMO, and reliance on heuristics) (Bikhchandani et al., 1992; De Long et al., 1990). Concequently, herding affects investor decision-making. According to Gervais and Odean (2001), herding arises when investors blindly follow the crowd, neglecting individual analysis and potentially leading to suboptimal decisions. This can be driven by a desire to conform to social norms or a belief in the collective wisdom of the crowd De Long et al. (1990). Banerjee (1992) argued that individuals make decisions based on the choices of others without fully investigating the underlying information.

Furthermore, herding can lead to severe fluctuations in financial market performance, as investors may rush toward hot risky assets Hirshleifer & Sushkin (2003). Some empirical studies support this argument. For example, Gervais and Odean (2001) find that investors tend to chase past winners and underperform the market. In this regard, some studies suggest a negative correlation between herding and financial markets performance. Precisely speaking, organizations that attract herding investors often witness excessive volatility and suboptimal returns (Hwang & Kim, 2009; Graham et al., 2012). On the other hand, some studies highlight the potential benefits of herding (e.g., reduced information costs and mitigated short-term risks) Hirshleifer & Welch (1999).

A recent surge in research highlights a growing trend in investment towards environmentally sustainable investments (i.e., green investment) (Buchholz, 1993; Wang et al., 2020) and shifting from traditional, purely profit-driven strategies. Green investments can also include stocks in companies with a proven track record of environmental responsibility or those actively transitioning towards more sustainable practices. Roos et al. (2024) recently added that companies potentially invest specifically in cultivating a "green" image to attract investors. Also (Bauer et al. 2005; Renneboog et al., 2012) suggest that ethical and environmental considerations play a significant role in investment decisions. (Pelova, 2012; Hahn et al., 2015) stated that investors may seek alignment with their values by investing in organizations committed to positive environmental practices.

The recent emphasis on mandatory sustainability practices has created a novel investment landscape for Egyptian organizations In the contemporary financial landscape, Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) investing has emerged as a dominant trend (Krueger & Sautner, 2022). It represents a shift in investment analysis, incorporating non-financial factors alongside traditional financial metrics to assess a company's overall value and potential Kellner (2022). An ESG index is a stock market index that tracks the performance of companies that consider environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors alongside financial factors.

The environmental dimension evaluates a company's impact on the planet, encompassing factors such as climate change mitigation, resource use efficiency, pollution control, and waste management Flammer (2021). The social aspect focuses on a company's relationships with stakeholders, including employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities it operates within. Labor practices, diversity, inclusion, and data privacy are all crucial considerations Eccles et al. (2011). The Governance, this component assesses a company's leadership structure, executive compensation, board composition, shareholder rights, and overall transparency. Strong governance practices minimize risk and promote long-term sustainability Chapple et al. (2011). In other words, this index aims to capture the performance of companies that are not only profitable but also sustainable and responsible. By integrating these factors into the investment decision-making process, the ESG index aims to create a more comprehensive picture of a company's value proposition and future prospects.

Some studies found a positive correlation between ESG performance and firm value (Chen et al., 2020; Luo & Xu, 2017). On the other hand, other studies found insignificant impact or even a negative correlation (Friede et al., 2015; Lins et al., 2017). Market capitalization (market cap ) and investor behavior are intricately linked. The market cap provides a universal method for valuing companies. As defined by Damodaran (2018) market cap is calculated by multiplying the current market price per share by the total number of outstanding shares. This formula allows investors to easily compare companies regardless of industry or specific financial metrics. This point is further emphasized by (Fernandes et al. (2017) who argue that market cap offers a standardized measure for size comparison across different sectors.

This research investigates the impact of herding behavior on market capitalization within ESG indexes, with a specific focus on Egyptian-listed firms in EGX30, by examining this under-explored area in behavioral finance in Egypt. This research aims to achieve two key objectives. Firstly, understanding the Influence of Herding behaviour and how investors' decisions are swayed by the actions of others and its impact on market capitalization. Secondly, Evaluate the changes in market capitalization of EGX 30 companies before and after the adoption of ESG practices.

The research offers a comprehensive approach, integrating insights from psychology and finance.The study's contribution lies in shedding light on the impact of herding behavior and ESG disclosure on market capitalization, providing insights for investors, policymakers, and companies on the importance of these factors in valuation and decision-making processes. It also adds to the existing literature on behavioral finance, corporate governance, and sustainable investing.The initial stage establishes the theoretical foundation through a literature review encompassing behavioral finance theory, herding theory, and stakeholder theory moving to herding behaviour and factors that affect herding behaviour then its measurement, ESG in Egypt, market capitalization then the relationship between herding and market capitalization finally ESG and investor behaviour. Subsequently, the methodology details the data collection process from the Egyptian Stock Exchange (EGX30) over six years (2018-2023). This is followed by data analysis, discussion, conclusions, limitations, and future areas of research.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Behavioural Finance Theory

Investing inherently involves undertaking calculated risks with the expectation of reaping greater returns in the future. This fundamental relationship between investment, risk, and return is unidirectional, as posited by Agyemang and Ansong (2016). Higher potential returns are typically associated with a greater degree of risk, while lower risks are accompanied by more modest returns Martin, 2014. However, optimal investment decision-making requires investors to consider a diverse array of factors beyond just the risk-return relationship. This includes both psychological considerations and a comprehensive analysis of financial and non-financial data (Mutswenje et al., 2014; Hoang, 2020).

The traditional view of investors is purely rational actors making purely logical decisions however this is challenged by the field of behavioral finance. This multifaceted discipline, drawing from disciplines like finance, psychology, and sociology Muradoglu & Harvey (2017) acknowledge the influence of emotions and psychological biases on investor behavior. As Ackert 2014 suggests, investors exhibit a blend of both logical (financially driven) and illogical (emotionally driven) behaviors. While rational investors meticulously analyze information to optimize their choices Areiqat (2019), Irrational investors are susceptible to psychological biases that can lead to suboptimal decisions as mentioned by Sedaghati (2016).

Behavioural finance emphasizes the influence of psychology and cognitive biases on individual and market-wide financial behaviour. Investors are not perfectly rational, they are susceptible to cognitive biases that lead to errors in judgment and suboptimal financial decisions Shefrin & Statman (2000).

2.2. Herding Bias Theory

Herding bias, a well-established cognitive bias, describes the tendency of individuals to adopt the beliefs or behaviours of a majority group, even if they have doubts about the group's correctness. This inclination often stems from a fear of isolation or a desire to conform to established social norms. Despite its potential benefits (e.g., reduced decision-making effort), herding bias can significantly impact individual and group decision-making, leading to both positive and negative outcomes. The roots of herding bias can be traced back to Keynes (1936) who argued that individuals often follow the crowd in situations of uncertainty, believing the majority possesses better information.

However, modern interpretations delve deeper, exploring various psychological and sociological mechanisms driving this behaviour. As Bikhchandani et al. (1992) mentioned Individuals rely on the observed decisions of others as informational cues, leading to a cascade where the initial decision, regardless of its accuracy, gains momentum. Asch (1951) argued that fear of disapproval or exclusion motivates individuals to align their behaviour with the perceived majority opinion. However Gigerenzer & Goldstein (2009) stated that Individuals utilize mental shortcuts, such as imitating successful others, to simplify decision-making, potentially leading to herding behaviour.

2.3. Stakeholder Theory

Stakeholder theory, a business ethics and corporate governance theory, challenges the usual focus on shareholders. According to Freeman (1984), businesses must consider the interests of more stakeholders affected by their operations than only shareholders. These stakeholders may include consumers, workers, suppliers, investors, operating communities, and the environment, according to Strand and Freeman (2015).

Three approaches to stakeholder theory were identified by Freeman (1984). First, a descriptive approach studies enterprise-stakeholder relationships. This perspective recognizes the interrelated nature of stakeholders and their impact on organizational performance Freeman (1984). Happy, motivated employees are more likely to provide excellent customer service, which increases customer loyalty and satisfaction Crane et al. (2014). Strong supplier relationships assure a steady supply of goods, which affects production and financial success.

The second approach, instrumental, emphasizes the practical benefits of involving stakeholders in organizational performance. Businesses may achieve stakeholder trust, loyalty, and sustainability by addressing their demands. An environmentally responsible firm that adopts sustainable practices may attract environmentally concerned investors and consumers, giving it a competitive edge Crane et al. (2014). Ethical treatment also increases employment retention, improved productivity, and lower turnover.

The third approach, normative, emphasizes firms' moral and ethical duties to stakeholders. Phillips (2003) believes that corporations should prioritize stakeholder well-being over shareholder profitability. This approach emphasizes the social compact between society and enterprises, arguing that firms must actively enhance their communities.

2.4. Herding Behavior

Herding behavior can streamline decision-making, particularly when individual information is limited, or situations are ambiguous Surowiecki (2004). This efficiency can be valuable in fast-paced environments. Aligning with popular opinions, it can also enhance an organization's reputation and legitimacy while fostering trust and acceptance Deephouse & Suchman (1990). Additionally, herding serves as a risk-reduction strategy by allowing individuals to avoid potential blame for deviating from the group decision Whyte (1952). Furthermore, it can provide comfort and reduce anxiety, especially in complex or ambiguous situations Bikhchandani et al. (1992). By following the majority, individuals may perceive less risk and gain confidence in their choices.

Several studies suggest that herding behaviour can restrain innovation by encouraging conformity and discouraging the consideration of unconventional ideas (Gruenfeld & Schweiger, 2005; Paulus & Dzindolet, 2002). According to (Kerr et al., 1992; Whyte, 1952), Herding can lead to biased decision-making, as individuals overlook potentially important information that contradicts the dominant opinion which may result in costly mistakes and missed opportunities. When herding becomes extreme, it can morph into groupthink, where the pursuit of unanimity overrides critical thinking and dissent Janis (1972).

Herding can lead to group thinking, where critical thinking and dissent are suppressed, this can result in flawed decisions, ignoring valuable information, or overlooking potential problems. Janis (1972). As noted by, Nishikawa & Ornstein (2010). Individual knowledge and diverse perspectives may be neglected when everyone follows the same path, leading to missed opportunities and reduced innovation.

2.4.1. Factors That Affecting Herding Behaviour

2.4.1.1. Financial Analyst Recommendations and Herding Behaviour:

Investors typically use expert suggestions to make decisions. Investment analysts are vital to investment decisions. Their suggestions may be influenced by herding bias, as analysts follow others without sufficient independent investigation. This can cause overvaluations, undervaluations, and missed sustainable investment possibilities. Research shows that investors buy or sell assets like the majority Bikhchandaniet al. (1998).

Hong et al. (2000) found that buy recommendations affect stock prices more than sell recommendations. Their analysis showed that mispriced stocks follow expert recommendations, implying market overreaction. Another study by Reiner et al. (2022) found that expert financial advisers are more likely to steer client decisions in a specific direction than to encourage investors to forge their path.

Hong et al. (2000) and Scharfstein & Stein (1990) found that analysts converge their recommendations around popular stocks even when the data is weak. Organizations can profit from analyst optimism through a bandwagon effect. Although incorrect, negative analyst recommendations can cause an unjustifiable sell-off.

2.4.1.2. Social Influence and Herding Behaviour

Investors can be prone to herding behavior due to a lack of information, cognitive limitations, and the desire to conform. This can lead to uninformed investment driven more by hype and popularity than by a genuine understanding of their sustainability performance.

Social influence refers to the unintended alteration of an individual's thoughts, feelings, or behaviors due to the presence of others Bikhchandani et al. (1992). This influence can manifest through two primary mechanisms. Firstly, informational influence involves relying on the actions and opinions of others as a source of information, particularly in situations of ambiguity or uncertainty Cialdini & Goldstein (2009). Secondly, normative influence, on the other hand, arises from the desire to conform to the social norms and expectations of the group to avoid social disapproval or rejection Asch (1951). This suggests that investors may be prioritizing social proof and following the crowd rather than conducting thorough research on the actual impact of their investments.

2.4.1.3. Lack of Information and Herding Behaviour

A further significant reason for herding is the lack of information on investment decision-making. According to Ciarreta and Zarraga (2010), when investors are less confident about their private information or less aware of others' investment activities, it is more likely that they will imitate the investment behaviour of others. In other words, the less information or confidence they have, the more likely that their investment behaviour will be influenced by others, leading to herding. This explanation also sheds light on why novice or inexpert investors are more likely to rely on the opinion of others and to imitate the investment behaviour of others Froot et al. (1992).

2.4.2. Herding Behavior Measurement

Researchers rely on the Cross-sectional Absolute Deviation (CSAD) model, introduced by Chang et al. (2000), to gauge herding behavior in financial markets. This model analyzes how individual stock returns deviate from the average market return. However, a key limitation of CSAD is its inability to definitively pinpoint the reasons behind specific investment decisions. Directly interviewing all investors to confirm herding is impractical, making it difficult to establish a clear cause-and-effect relationship.

Despite this limitation, CSAD has proven useful in studying herding across European markets. Caporale et al. (2008) employed CSAD to analyze the Athens Stock Exchange during market downturns, while Economou et al. (2011) applied it to investigate herding in Portugal, Italy, Spain, and Greece. Additionally, Caparrelli et al. (2004) used CSAD on the Italian Stock Exchange, finding evidence that herding intensifies during volatile periods, aligning with observations by Christie and Huang (1995).

While some researchers like Schmitt and Westerhoff (2017) and Yamamoto (2011) suggest a correlation between herding and volatility clustering (periods of high volatility followed by more volatility), it remains unclear which phenomenon truly drives the other. CSAD might primarily measure volatility, with herding behavior being an assumed cause.

Despite this uncertainty about causality, the popularity of CSAD gives us confidence that it at least provides a general indication of herding behavior in the stock market.

2.5. ESG in Egypt

Egypt's approach to environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure has undergone a significant transformation in recent years. Initially, it relied on voluntary initiatives. A key example of this was the launch of the S&P ESG Index by the Egyptian Exchange (EGX) in 2007. This pioneering initiative assessed the environmental performance of leading listed companies, aiming to raise awareness about ESG factors among both businesses and investors (Elsayed & Kirkpatrick, 2018).

Further incentive for ESG adoption came from the government's "Vision 2030" strategy, which emphasized sustainable development (The Presidency of the Arab Republic of Egypt, 2016). Additionally, the Egyptian Corporate Responsibility Center (ECRC), established in 2007, played a crucial role. This joint initiative between the UNDP 2007 (United Nations Development Programme) and the Industrial Modernization Center (IMC) supported businesses in implementing the UN Global Compact's principles, which align with environmental responsibility and sustainable development goals.

A significant turning point in 2022 with the Financial Regulatory Authority's (FRA) decree mandating ESG disclosure for specific companies (Financial Regulatory Authority, 2022). This shift towards mandatory reporting signifies a strong commitment from the Egyptian authorities towards greater transparency and sustainable practices within the country's businesses.

- ▪

The launch of the S&P ESG Index by the EGX (2007)

- ▪

The Egyptian government's "Vision 2030" emphasizes sustainability (2016)

- ▪

The establishment of the ECRC to promote UN Global Compact principles (2007)

- ▪

The introduction of mandatory ESG disclosure regulation by the FRA (2022)

The Egyptian Stock Exchange (EGX) has emerged as a leader in promoting ESG practices among listed companies.

- ▪

Implementing rigorous disclosure requirements, including mandatory ESG reporting.

- ▪

Promoting specific reporting standards like GRI (Global Reporting Initiative) and TCFD (Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures).

- ▪

Establishing the S&P/EGX ESG Index and publishing annual sustainability reports.

- ▪

Co-founding international sustainability initiatives.

This leadership is further acknowledged by the Arab Federation of Capital Markets (AFCM), highlighting EGX's commitment to sustainability reporting, mandatory ESG disclosure, and support for various disclosure frameworks. Looking ahead, Decree No. 108 of 2021 mandates ESG disclosure for companies listed on the EGX. This further solidifies Egypt's commitment to sustainable development within its business sector.

Table 1.

| Initiative |

Year |

Description |

Regulatory Body |

| Launch of S&P ESG Index |

2007 |

Voluntary environmental performance assessment for leading listed companies |

Egyptian Exchange (EGX) |

| Establishment of ECRC |

2007 |

Supports businesses in implementing UN Global Compact principles |

UNDP & Industrial Modernization Center (IMC) |

| "Vision 2030" Strategy |

2016 |

Government strategy emphasizing sustainable development |

The Presidency of the Arab Republic of Egypt |

| Mandatory ESG Disclosure Decree |

2022 |

Mandates ESG disclosure for specific companies |

Financial Regulatory Authority (FRA) |

| Mandatory ESG Disclosure for EGX Listed Companies |

2021 (Decree No. 108) |

Applies to all companies listed on the Egyptian Stock Exchange |

Financial Regulatory Authority (FRA) |

2.5.1. Motivations for ESG Investing

Investors are increasingly cognizant of the long-term health of the environment and society. ESG investing allows them to align their portfolios with sustainable practices and contribute to positive societal change Azeez & Omotehinwa (2022).

On the other hand Companies with poor ESG practices face significant risks, such as regulatory fines for environmental transgressions, labor unrest stemming from unfair practices, or reputational damage from data breaches. ESG investing helps investors mitigate these risks by prioritizing companies with strong ESG performance Nguyen et al. (2015).

Furthermore, a growing body of research suggests a positive correlation between strong ESG practices and financial performance. Companies that prioritize ESG factors may demonstrate superior risk management, attract and retain top talent, and benefit from a positive brand image, potentially leading to long-term outperformance Luo & Tian (2019).

2.6. Market Capitalization

Market capitalization (market cap) is a fundamental metric used by investors and analysts to gauge the relative size and value of publicly traded companies. In the evolving world of finance, investors constantly seek reliable indicators to assess the worth of potential investments. Market capitalization (market cap) emerges as a prominent tool for gauging the relative size and market value of a publicly traded company (Investopedia, 2023). Market cap refers to the total dollar market value of a company's outstanding shares of common stock Horne & Wachtel (2012). Furthermore, it represents the total worth of a company from the perspective of the stock market. It is calculated by multiplying the current market price per share of the company's common stock by the total number of outstanding shares.

2.7. Herding Behaviour and Market Capitalization

As previously mentioned, the Market cap is a crucial metric for companies and investors. It reflects investor confidence and a company's overall financial health Aswath (2012). However, market psychology can significantly influence market capitalization. Herding behavior, where investors follow the actions of others irrespective of fundamental analysis, can distort market efficiency and impact market capitalization Bikhchandani & Sharma (2000). Herding can have significant consequences for market capitalization.

According to a study conducted by Haigh et al. (2005), during times of low market uncertainty or high information availability, the impact of herd behavior can be quite significant in leading to illiquidity in the stock market. This is similar to the findings of Bikhchandani et al. (1992) who also suggested that in uncertain times, herding has more effects than at times of high market uncertainty.

Herding can inflate asset prices beyond their intrinsic value, creating bubbles. When the herd mentality reverses, bubbles can burst, leading to sharp declines in market capitalization Shiller (2005). In addition, Herding can distort prices away from their fundamental value, hindering efficient allocation of capital Grinblatt & Shleifer (2008). Furthermore, Herding can amplify market swings, leading to increased volatility in market capitalization Barberis et al. (1998).

Several studies have explored the link between herding and market capitalization. Some studies, such as Antoniou, Fokas and Grammenos (2008), find evidence that herding is more prevalent during periods of market uncertainty. Others, like Changet al. (2014), suggest it can occur even in relatively stable markets. Siestat and Albuquerque (2008) find a positive correlation between herding and market capitalization, suggesting that herding can inflate the valuations of larger companies. Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated.

H1: There is a significant impact of herding behaviour on market capitalization.

2.8. ESG Integration and Investor Behavior

The inclusion of ESG factors in investment decisions has gained significant traction in recent years. Studies suggest that ESG integration may lead to more rational and long-term-oriented investment strategies (Flammer & Sewerin, 2018; Krueger & Saxton, 2020). This could potentially mitigate herding behavior as investors focus on company fundamentals rather than solely following market trends.

Some Potential Impacts of ESG on the Herding behaviour and Market Capitalization Relationship. Robust ESG disclosure can improve transparency and information asymmetry, potentially reducing reliance on herding for information gathering Boulton et al. (2018).In addition, Companies with strong ESG practices may be perceived as less risky, potentially attracting more sophisticated investors less prone to herding Eccles et al. (2012). Furthermore, ESG integration often emphasizes long-term sustainability, potentially leading investors to focus on company fundamentals rather than short-term market movements that might trigger herding behavior Genschel et al. (2013). Therefore, the following hypotheses are formulated.

H2:ESG has a positive impact on the relationship between herding behaviour and market capitalization

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample and Data Collection

To examine the impact of herding behavior on market capitalization in the Egyptian stock market before and after the disclosure of environmental-social-governance scores (ESG Score Index). We used the data from Appendix (1) from two data sources, namely, (Bloomberg) financial databases and Mobasher. The study sample was drawn from listed companies in EGX30 in Egypt. Panel data was collected for the years 2018-2023. Whereas from 2018 to 2020 ( before disclosing ESG) and then from 2021 to 2023 (After disclosing ESG). The final sample consists of 22 organizations according to the SP/EGX ESG index This study excludes firm-years that miss the necessary data for the variables used in this analysis.

4.2. Variables

After conducting an in-depth literature review, the determinants and the variables used for model estimation were identified Table (2) lists the determinants and the variables.

Table 2.

Research variables.

Table 2.

Research variables.

| Variable |

Description |

Source |

Literature source |

| Dependent Variable |

Mcap |

Market capitalization (total value of all a company's shares) |

Horne & Wachtel (2012) |

| Control Variable |

Nincome |

Firm net income |

Brigham, E. F., & Houston, J. F. (2006) |

| Control Variable |

Fsize |

Firm size (natural logarithm of total assets) |

Ehrhardt, R. A., & Brigham, E. S. (1990) |

| Control Variable |

Fage |

Firm age (time between initial creation and present time) |

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984) |

| Independent Variable |

ESG |

ESG Combined Score (overall company score based on environmental, social, and corporate governance) |

Egypt publishing annual sustainability reports |

| Independent Variable |

CSAD |

Herding behavior methodology (cross-sectional absolute deviation of returns) |

Chang et al. (2000) |

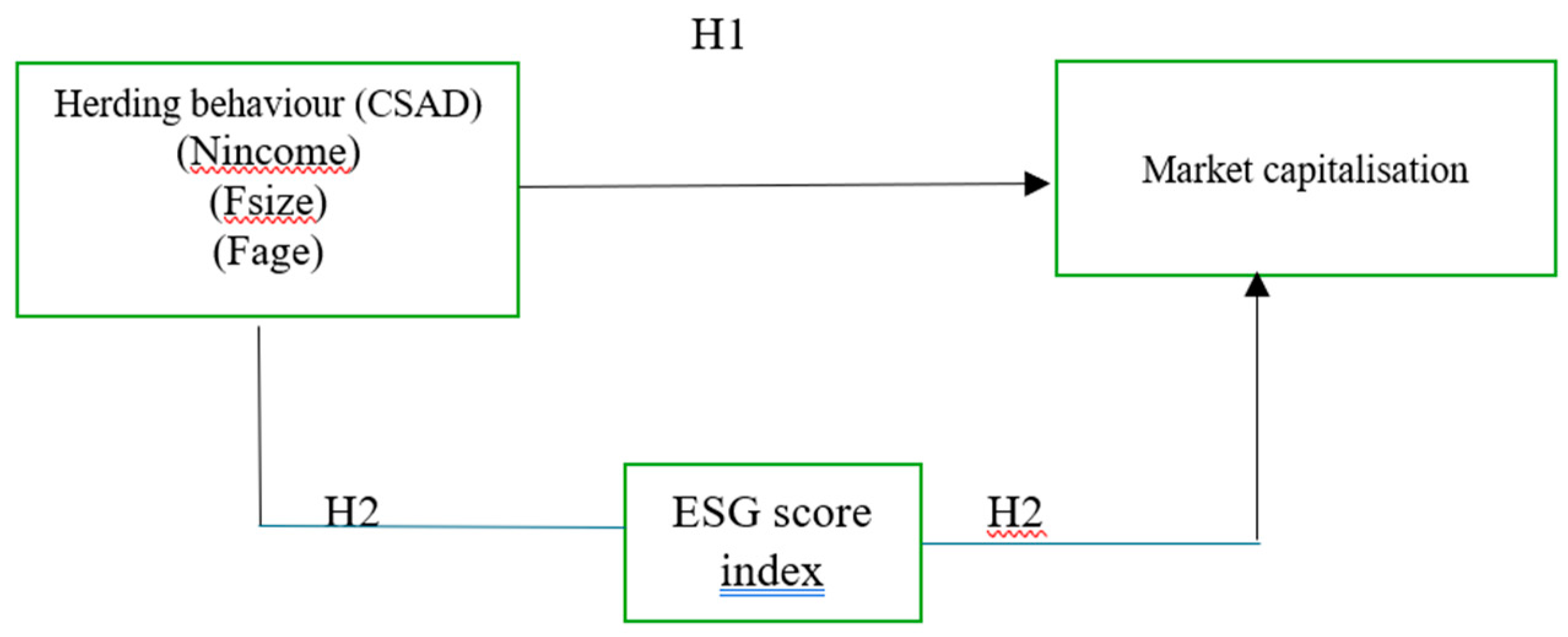

Figure 1.

conceptual model.

Figure 1.

conceptual model.

4.3. Model Estimation

The empirical model was developed by applying panel data regression. To determine the impact of herding behavior on market capitalization in the Egyptian stock market before and after the disclosure of environmental-social-governance scores (ESG Score Index) considering heterogeneity across variables, panel data regression was applied (Baltagi 2008). The study controls for various factors that may affect market capitalization, based on previous studies; including Net income (Nincome), Firm size (Fsize), and Firm age (Fage). By including these control variables in the analysis, the study enhances the robustness of the findings and provides a more comprehensive understanding of the factors influencing market capitalization. The dependent variable is market capitalization (Mcap) and the independent variable is herding behaviour (CSAD).

The regression equation can be presented as follows:

The first model measures the impact of herd behavior on the firm's performance

before disclosing ESG.

Where the dependent variable (LMcap) is the market cap (market capitalization) which is the logarithm of the total value of shares, It is calculated by multiplying the price of a stock by its total number of outstanding shares. The control variables include (Nincome) firm net income, (Fsize) firm size (the natural logarithm of total assets), and (Fage) firm age (the time between the initial creation of a firm and the present time in years). β1, β2, β3, and β4 are the coefficients of the independent variables (CSAD, Nincome, Fsize, Fage), indicating the expected change in market capitalization associated with a one-unit change in each respective variable.ε represents the error term, accounting for unexplained factors.

The second model measures the impact of herd behavior on the Firm's performance

After disclosing ESG.

The additional term β5 * ESG represents the coefficient of the ESG score variable, indicating the expected change in market capitalization associated with a one-unit change in the ESG score. ESG Combined Score is an overall company score based on the reported information in the environmental, social, and corporate governance pillars (ESG Score)

1. All other terms (β1, β2, β3, β4) have the same interpretations as in Model (1). The regression analysis for Model 2 provides estimates of the coefficients (β), including the coefficient for the ESG score, to examine the relationships between the independent variables and market capitalization after considering the impact of ESG disclosure. Overall, the regression models aim to quantify the impact of herding behavior, ESG disclosure, and other control variables on market capitalization. By estimating the coefficients and assessing their significance, the models provide insights into the relationships and contribute to understanding the factors influencing market valuation.

CSAD Methodology of herding behavior, cross-sectional absolute deviation of returns

Where, Ri,t is the return of the stock on the day, Rm,t is the market return on the same day, and N is the number of stocks in the index used. Researchers rely on the Cross-sectional Absolute Deviation (CSAD) model, introduced by Chang et al. (2000), to gauge herding behavior in financial markets. This model analyzes how individual stock returns deviate from the average market return.

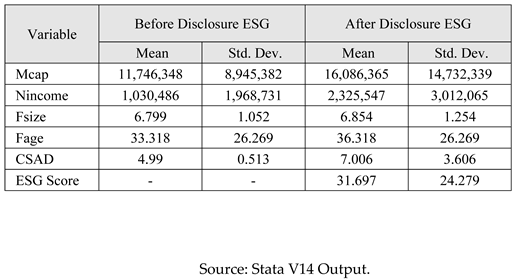

5. Descriptive Statistics

This section includes the descriptive statistics and correlation coefficient results of all variables of the whole sample period. Table (3) includes the descriptive analysis for the dependent and independent variables results before ESG disclosure indicating that the arithmetic mean of the market capitalization variable (Mcap) reached 11 million pounds for the firms during the period from 2018 to 2020, with a standard deviation of 8.9. The herd behavior (CSAD) mean is almost 5, with a standard deviation of 0.51. In addition, the mean for control variables, net income (Nincome), company size, and company age, is (1,030 - 6.7 - 33.3), respectively, with a standard deviation of (1.9 - 1.05 - 26.02).

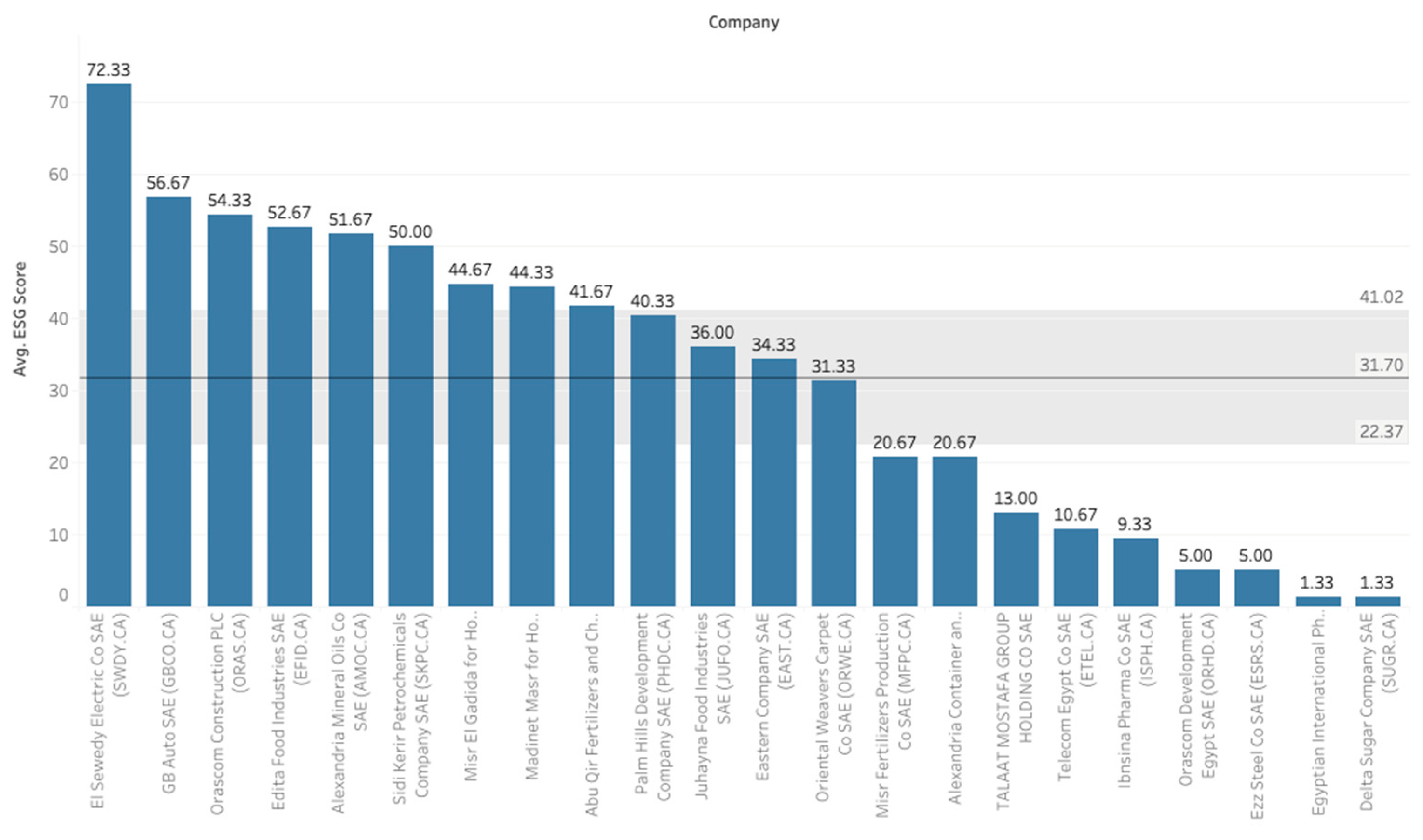

However, descriptive analysis after ESG disclosure indicates that the arithmetic mean of the market capital (Mcap) increased to 16 million pounds, the herd behavior (CSAD) mean reached 7 with a standard deviation of 3.6, and the ESG Score mean reached 31.6 with a standard deviation of 24.2, by comparing the results of the descriptive analysis before and after the ESG disclosure, we found the following:

The market capitalization of the companies under study ranged from 1.16 million Egyptian pounds to 39.2 million Egyptian pounds during the period from 2018 to 2020. After the ESG disclosure, the market capitalization increased, ranging from 2.04 million Egyptian pounds to 39.2 million Egyptian pounds during the period from 2021 to 2023. Additionally, the ESG Score ranged from 0 to 84 for the companies under study during the period from 2021 to 2023 net income also improved after disclosing the ESG Score for these companies.

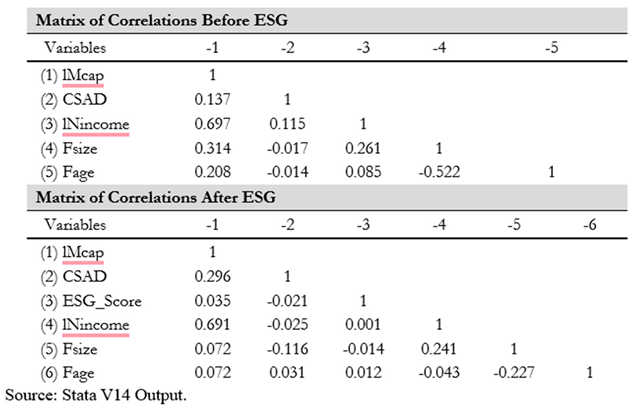

After conducting a descriptive analysis of the study variables, a correlational analysis was conducted to understand and clarify the relationship between the variables for the companies under study. The results of Table No. (4) show the results of the correlation test between the dependent variable market capitalization (Mcap) and the independent variables before and after the disclosure of the ESG Score.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics Before & After Disclosure ESG.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics Before & After Disclosure ESG.

Table (4) shows the results of the correlation coefficient test before and after the ESG Score disclosure

Table 4.

Results of correlation test before and after ESG Score disclosure.

Table 4.

Results of correlation test before and after ESG Score disclosure.

The correlation test results before disclosing the ESG Score show a positive relationship between the independent variable herd behavior (CSAD) and the dependent variable market capitalization with a value of 0.13. There is also a positive relationship between the control variables net income, company size, company age, and the dependent variable capital market value (0.697, 0.31, 0.20). After disclosing the ESG Score, the results show a positive relationship between the independent variable herd behavior (CSAD) and the dependent variable market capitalization with a value of 0.29. There is also a positive relationship between the ESG Score and the dependent variable market capitalization with a value of 0.035. Additionally, there is a direct relationship between the control variables net income, company size, company age, and the dependent variable market capitalization, with values of 0.691, 0.072, and 0.072 respectively. The relationship between herd behavior (CSAD) and market capitalization after disclosing the ESG Score increased from (0.13 to 0.29). Before estimating study models, there are several tests available to examine the validity of the proposed study model. The following are the most important tests that were used to evaluate the study model.

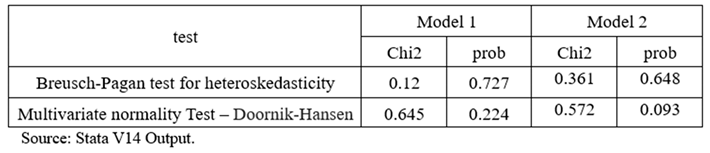

We also run the heteroskedasticity test to check whether the variance of the errors from regression is dependent on the values of the independent variables. In addition to the Multivariate normality test which examines the null hypothesis that the data are multivariate normally distributed. It measures the degree of multivariate skewness and kurtosis in the data and compares it to the expected values under the assumption of multivariate normality. Table (5)

Table 5.

heteroskedasticity and Multivariate normality test.

Table 5.

heteroskedasticity and Multivariate normality test.

Table (5) shows the difference between the variance tests (heteroskedasticity model 1 = 0.12, model 2 = 0.361), and the p-values for both models are 0.727 and 0.648, which are greater than 0.05. This indicates that the study models do not have a problem with variance. Also, the Doornik-Hansen test results indicate that chi2 is 0.645 and 0.572, with a significant probability between 0.297 and 0.093. They are greater than 0.05, so the residuals follow a normal distribution. The Variance Inflation Factor results range between 1 and less than 5, indicating that the regression models do not have a multicollinearity problem. Additionally, the mean Variance Inflation Factor for the models is 1.319 and 1.053, which is less than 5, indicating that the models are suitable for regression analysis.

6. Empirical Results

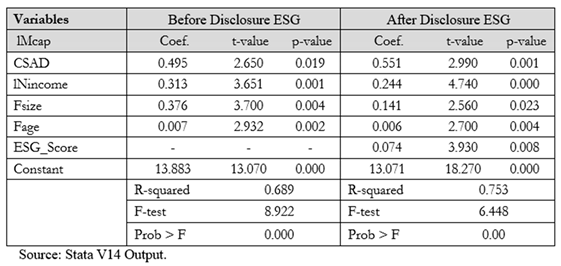

As shown in Table (6), we test the two hypotheses of the research H1: There is a significant impact of herding behaviour on market capitalization. H2:ESG has a positive impact on the relationship between herding behaviour and market capitalization.

Table 6.

Test herding behavior impact on market capitalization.

Table 6.

Test herding behavior impact on market capitalization.

The results show that the value of the F-test for the two models was 8.92 and 6.44, with a statistical significance value of 0.00 at a significance level of 5%, indicating the significance of the estimated study models. The coefficient of determination R2 for the first model was 0.689, meaning 68.9% of the change in market capitalization before ESG disclosure is due to herd behavior (CSAD) and the control variables in the first model. The herd behavior (CSAD) variable and control variables in the second model also explain 75.3% of the changes in market capitalization after ESG disclosure.

The results of the first model, which is before ESG disclosure, also indicate a positive effect of herd behavior (CSAD) on the logarithm of market capitalization with a coefficient of 0.495 and a statistically significant value of 0.019 at a 5% significance level. This suggests that a one-unit increase in herd behavior (CSAD) results in a 0.495 increase in market capitalization.

It is also clear from the results that there is a positive effect of the control variables of the logarithm of net income, company size, and company age on the dependent variable of the logarithm of market capital with values (0.13 - 0.37 - 0.007), and with a statistical significance value (0.001 - 0.004 - 0.002) at a significance level of 5%. This indicates that increasing the control variables by one unit will lead to an increase in market capitalization by values of 0.13, 0.37, and 0.007, respectively. From these results, the regression rate for the first model can be derived as follows:

While the results of the second model after adding the ESG variable indicate that the herd behavior variable (CSAD) positively affects the variable logarithm of market capitalization with a value of 0.551, and a statistical significance value of 0.01 at a 5% significance level, which indicates that increasing herd behavior (CSAD) by one unit leads to an increase in market capitalization by 0.551

In addition, the ESG score variable also has a positive effect on the market capitalization variable with a coefficient of 0.074 and a statistical significance value of 0.008 at a 5% significance level. This indicates that increasing the ESG score by one unit leads to an increase in market capitalization by 0.074 units. There is also a positive effect of the control variables, including the logarithm of net income, company size, and company age, on the dependent variable of the logarithm of market capitalization. The coefficients for these variables are 0.24, -0.14, and 0.006, respectively, with statistical significance values of 0.00, 0.023, and 0.004 at a 5% significance level. This suggests that increasing the control variables by one unit will lead to an increase in market capitalization by the corresponding coefficients. Based on these results, the regression equation for the second model can be formulated as follows:

Figure 2.

Average ESG Score for research company sample (2021 – 2023).

Figure 2.

Average ESG Score for research company sample (2021 – 2023).

7. Conclusions

This research investigated the impact of herding behavior on market capitalization in the Egyptian stock market before and after the disclosure of environmental-social-governance scores (ESG Score Index) in the Egyptian stock market EGX 30 companies. The final sample consisted of 22 organizations according to the SP/EGX ESG index. We use Panel data analysis from 22 Egyptian Stock Exchange EGX 30 companies' financial statements from 2018-2023. The study employs regression analysis to examine the relationships between variables and tests the models for variance, normal distribution of residuals, and multicollinearity. By conducting these tests, the study ensures the reliability and validity of the results and contributes to the methodological rigor of the research.

We found that both models are statistically significant. The first model, before ESG disclosure, shows a positive effect of herding behavior (CSAD) on market capitalization (Mcap) with a coefficient of 0.495 and a statistically significant value of 0.019. The control variables (net income, firm size, firm age) also have positive effects on market capitalization with coefficients of 0.376, 0.007, and 0.313, respectively. The study contributes to the existing literature by providing empirical evidence of the positive relationship between herding behavior and market capitalization. This finding suggests that when investors exhibit herding behavior, it can have a significant impact on the valuation of companies in the market. This is supported by previous research by Siestat & Albuquerque (2008). This suggests that investor sentiment and herding can significantly impact company valuations, potentially leading to over or undervaluation.

The second model, after adding the ESG variable, demonstrates a positive effect of herding behavior (CSAD) on market capitalization (Mcap) with a coefficient of 0.551 and a statistically significant value of 0.01. The ESG score variable also positively affects market capitalization with a coefficient of 0.074 and a statistically significant value of 0.008. The control variables (net income, firm size, firm age) continue to have significant effects on market capitalization. The results indicate that after disclosing the ESG score, there is a positive effect on market capitalization. This finding suggests that investors consider ESG factors when valuing companies, and companies with higher ESG scores are rewarded with higher market capitalization. This is aligned with some prior research suggesting ESG integration might have a positive impact on market capitalization (Flammer & Sewerin, 2018; Krueger & Saxton, 2020)

According to the research outcomes, although ESG disclosure enhances transparency, it may not completely eradicate herd mentality in nascent economies such as Egypt. Particularly when assessing firms that adhere to robust environmental, social, and governance (ESG) practices, investors may continue to depend on herding. This underlines the necessity for additional investor education regarding the long-term financial implications of ESG factors. The research also has significant ramifications for policymakers and investors. The study emphasizes the impact of herding behaviour on market dynamics and the potential advantages of incorporating environmental, social, and governance (ESG) factors into investment decision-making for investors. The research provides policymakers with valuable insights regarding the influence of ESG practices on market valuations and underscores the significance of advocating for sustainable investment practices.

This study enhances the existing body of literature on behavioural finance and ESG practices in the Egyptian context by concentrating on the Egyptian stock market. Contributing to the comprehension of market dynamics in the region, this provides market participants and policymakers in Egypt with valuable insights.

Appendix

Appendix (1).

sample companies used in the research

Appendix (1).

sample companies used in the research

| Number |

Company Name |

| 1 |

El Sewedy Electric Co SAE |

| 2 |

GB Auto SAE |

| 3 |

Edita Food Industries SAE |

| 4 |

Sidi Kerir Petrochemicals Company SAE |

| 5 |

Madinet Masr for Ho.. |

| 6 |

Palm Hills Development Company SAE |

| 7 |

Juhayna Food Industries SAE |

| 8 |

Oriental Weavers Carpet Co SAE |

| 9 |

Talaat Moustafa Group Holding Co SAE |

| 10 |

Telecom Egypt Co SAE |

| 11 |

Ibnsina Pharma Co SAE |

| 12 |

Orascom Development Egypt SAE |

| 13 |

Ezz Steel Co SAE |

| 14 |

Egyptian International Pharmaceutical Co SAE |

| 15 |

Orascom Construction PLC |

| 16 |

Alexandria Mineral Oils Co SAE |

| 17 |

Misr El Gadida for Housing and development |

| 18 |

Abu Qir Fertilizers and Chemical Industries Co |

| 19 |

Eastern Company SAE |

| 20 |

Misr Fertilizers Production Co SAE |

| 21 |

Alexandria Container and Cargo Handling Co SAE |

| 22 |

Delta Sugar Company SAE |

References

- Ackert, R. F. (2014). Behavioral finance: Practical insights for investors. John Wiley & Sons.

- Agyemang, S. K., & Ansong, D. K. (2016). The relationship between risk and return in the Ghanaian stock market. International Journal of Finance & Economics, 21(1), 78-93.

- Antoniou, A., Fokas, E., & Grammenos, C. (2008). Herding and return predictability in emerging stock markets. The Financial Review, 43(2), 229-250.

- Areiqat, A. S. (2019). The role of information asymmetry in listed companies' financial performance: Evidence from Jordan. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 11(12), 118-127.

- Asch, S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. Psychological Monographs: General and Applied, 65(9), (Whole No. 332).

- Aswath Damodaran, A. (2012). Investment valuation: Tools and techniques for determining the intrinsic value of any asset. John Wiley & Sons.

- Azeez, B. A., & Omotehinwa, O. E. (2022). ESG investing and investor perceptions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 1-22. doi.org.

- Baltagi, B. H. (2008). Econometric analysis of panel data. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons.

- Banerjee, A. V. (1992). A Simple Model of Herd Behavior. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 107(3), 797-817.

- Barberis, N., & Odean, T. (1998). "Behavioral finance: A review and prospectus." Journal of Economic Literature, 36(1), 1-55.

- Barberis, N., Shleifer, A., & Sun, Y. (1998). No consensus on noise. The Journal of Finance, 53(5), 1667-1687.

- Bauer, R., Derwall, J., & Otten, R. (2005). Foreign direct investments and corporate social responsibility: A meta-analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 62(4), 367-382.

- Bikhchandani, S., & Sharma, S. (2000). Herd behavior in financial markets. IMF Staff Papers, 47(3), 85-118. [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1992). A theory of fads, fashion, custome, and cultural change as informational cascades. Journal of Political Economy, 100(5), 992-1026. [CrossRef]

- Bikhchandani, S., Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1998). Learning from the behavior of others: Conformity, cascades, and informational equilibria. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 113(1), 59-92. [CrossRef]

- Boulton, P., Faure-Champallier, A., & Trottet, J. L. (2018). ESG disclosure and herding behavior. Journal of Corporate Finance, 52, 209-227.

- Brigham, E. F., & Houston, J. F. (2006). Fundamentals of financial management (11th ed.). South-Western College Pub.

- Buchholz, R. K. (1993). Theories of environmental ethics and the concept of sustainability. Business Ethics Quarterly, 3(1), 5-26.

- Caparrelli, A., Cappiello, L., & Leone, A. (2004). Herding behavior in the Italian stock exchange. Applied Financial Economics, 14(1), 75-83.

- Caporale, G. M., Cipollini, A., & Spagnolo, N. (2008). Herding and market volatility in the Athens Stock Exchange. The European Journal of Finance, 14(7-8), 903-922.

- Chang, L., Keim, S., & Schaumburg, E. (2000). Measuring herd behavior. The Journal of Finance, 55(5), 1941-1963.

- Chang, L., Liu, W., & Moulton, C. (2014). Does herding behavior affect stock return predictability? Evidence from China's A-share market. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 26(2), 316-336.

- Chang, L., Liu, W., & Moulton, C. (2014). Does herding behavior affect stock return predictability? Evidence from China's A-share market. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 26(2), 316-336.

- Chapple, A., Moon, J., & Winn, M. (2011). Corporate governance and carbon performance. Strategic Management Journal, 32(8), 887-918.

- Chen, P., Huang, B., & Liu, Z. (2020). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) disclosure and firm value: A meta-analysis. Business & Society, 59(1), 1-33.

- Christie, W. G., & Huang, R. (1995). *Following the leader: Evidence from expert stock recommendations. The Journal of Finance, 50(2), 881-901.

- Cialdini, R. B., & Goldstein, N. J. (2009). Influence: The psychology of persuasion. Allyn & Bacon. (Informational Influence).

- Ciarreta, P., & Zarraga, M. (2010). Herding behavior in professional stock selection. The Financial Review, 45(1), 127-153.

- Crane, A., Matten, D., & Spence, L. (2014). Business ethics: Managing corporate citizenship and sustainability in the global economy. Oxford University Press.

- Damodaran, A. (2012). Investment valuation: Tools and techniques for determining the intrinsic value of any asset. John Wiley & Sons.

- Damodaran, A. (2018). Investment valuation: Tools and techniques for determining the intrinsic value of any asset. John Wiley & Sons.

- De Long, J. B., Shleifer, A., Summers, L. H., & Waldmann, R. J. (1990). Noise trader risk in financial markets. Journal of Political Economy, 98(4), 703-738. [CrossRef]

- Deephouse, D. L., & Suchman, L. A. (1990). The symbolic organization of work. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 15(1), 243-262.

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2011). The impact of corporate sustainability on investor confidence. Journal of Investing, 20(3), 78-89.

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). The investor revolution. Harvard Business Review, 90(5), 62-72.

- Economou, G., Georgopoulos, D., & Philippas, P. (2011). Herding behavior in European stock markets. Economic Modelling, 28(2), 682-692.

- Elsayed, K., & Kirkpatrick, I. (2018). ESG in MENA: An overview. The Fletcher School Working Paper Series, (FLS18-C008).

- Fernandes, M., Ferreira, A., & Matos, J. (2017). Market capitalization and firm performance: A review and synthesis of the evidence. Journal of Business Research, 99, 149-163.

- Financial Regulatory Authority. (2022). Decree No. (141).[Decree No. (141) for the year 2022 regarding the governance rules for companies listed on the Egyptian Stock Exchange] (In Arabic). Retrieved from the Financial Regulatory Authority website: [link to the decree in Arabic, if available].

- Flammer, C. (2021). Finance and sustainability. Routledge.

- Flammer, C., & Sewerin, A. (2018). Heterogeneity and persistence of ESG effects. Financial Management, 47(1), 217-242.

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. Pitman Publishing.

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG (environmental, social and governance) factors in corporate finance – A survey of the literature. Business & Society, 54(1), 167-220.

- Froot, K. A., Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (1992). Herd behavior: Learning from long-term trends in profitability. The Journal of Finance, 47(5), 1663-1692.

- Genschel, P., Michaelis, L., & Mock, E. (2013). Sustainable investment: Performance and trends. Finance Research, 1(1), 22-49.

- Gervais, S., & Odean, T. (2001). Learning from mistakes: Fifty years of contrarian investment experience. Journal of Finance, 56(4), 1129-1158.

- Gigerenzer, G., & Goldstein, D. T. (2009). Fast and frugal heuristics: The adaptive mind in expert and everyday decision-making. Oxford University Press.

- Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., & Kim, E. H. (2012). When does herding hurt? Investor sophistication and stock market crashes. The Review of Financial Studies, 25(1), 1-30.

- Grinblatt, M., & Shleifer, A. (2008). Information and herding: A theory of aggregate behavior in financial markets. The Journal of Political Economy, 116(5), 1009-1030.

- Gruenfeld, D. H., & Schweiger, D. M. (2005). Voice: Influencing workplace decisions through speaking up. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hahn, T., Pinkse, J., Preuss, L., & Figge, F. (2015). Tensions in corporate sustainability: Towards an integrative framework*. Journal of Business Ethics, 128(1), 297-316. [CrossRef]

- Haigh, D., LeBaron, D., & Yao, V. (2005). Agent-based simulation of the impact of herding on asset price volatility. The Review of Financial Studies, 18(2), 709-740.

- Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49(2), 149-164. [CrossRef]

- Hirshleifer, D., & Sushkin, A. (2003). Waves of rationality and waves of emotion in financial markets. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 127-157.

- Hirshleifer, D., & Welch, I. (1999). Liquidity, information aggregation, and market efficiency. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 1-44.

- Hoang, M. H. (2020). Investor sentiment and stock market returns: A review of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 30(3), 820-843.

- Hong, H., Kubik, J. D., & Stein, J. C. (2000). The flight of the quality spread. The Review of Financial Studies, 13(1), 67-100.

- Horne, J. C., & Wachtel, S. M. (2012). Fundamental analysis: The essential guide to company valuation and stock selection. John Wiley & Sons.

- Hrhardt, R. A., & Brigham, E. S. (1990). The effect of merger size on shareholder wealth. Financial Management, 19(1), 79-88.

- Hwang, S. O., & Kim, L. (2009). Herd behavior and stock price volatility. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(10), 1900-1910.

- Investopedia. (2023, April 18). Market capitalization. Investopedia: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/m/marketcapitalization.asp.

- Janis, I. L. (1972). Victims of groupthink. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Kerr, N. L., MacDougall, M., & Winkler, R. C. (1992). Social psychology. HarperCollins College Publishers.

- Keynes, J. M. (1936). The general theory of employment, interest and money. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

- Krueger, P., & Sautner, D. (2022). ESG investing: From niche to mainstream. The Review of Financial Studies, 35(8), 3665-3700. [CrossRef]

- Krueger, P., & Saxton, B. (2020). ESG integration and risk-adjusted performance. The Review of Financial Studies, 33(5), 2086-2131.

- Lins, K. V., Servaes, H., & Tamayo, A. (2017). Social capital, corporate governance and firm performance. Journal of Financial Economics, 125(2), 283-311.

- Luo, X., & Tian, G. (2019). The evolving landscape of ESG integration in financial markets. Financial Analysts Journal, 75(4), 79-94.

- Luo, X., & Xu, P. (2017). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investment: Performance and impact. Ecological Economics, 140, 83-102.

- Martin, J. C. (2014). Investment analysis and portfolio management. John Wiley & Sons.

- Muradoglu, G., & Harvey, C. R. (2017). Behavioral finance: A critical review. International Review of Financial Analysis, 55, 1-16.

- Mutswenje, L., Matsika, A., & Makochekanwa, A. (2014). The role of financial literacy in investment decision-making. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, 6(8), 342-351.

- Nguyen, P. A., Hoang, M. H., & Phan, D. H. (2015). *Do good to do well? ESG integration and risk-return performance in Vietnam. Sustainability, 7(1), 748-773. doi.org.

- Nishikawa, G., & Ornstein, S. (2010). How the power of the crowd can sabotage success: The case of escalating commitment. Academy of Management Journal, 53(1), 183-205.

- Paulus, P. B., & Dzindolet, M. T. (2002). Social influence in creative teams: The effects of collaboration climate on individual creativity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 58.

- Pelova, V. (2012). The impact of corporate social responsibility on consumer behavior in a utilitarian and deontological context. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(3), 381-394.

- Reiner, I., Roulstone, A., & Williamson, R. (2022). Robo-advisors versus human advisors: A nudge theory perspective. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 36, 100409.

- Renneboog, L., TerWeduwe, J., & Baur, D. G. (2012). Corporate governance and investor sentiment. Journal of Banking & Finance, 36(4), 1377-1388.

- Roos, M., Rondorf, H., & Seidl, D. (2024). Greenwashing for attracting investors: An experimental study. Journal of Business Ethics.

- Scharfstein, D. S., & Stein, J. C. (1990). Herd behavior and cascading in information markets. The American Economic Review, 80(3), 505-522.

- Schmitt, L. M., & Westerhoff, F. O. (2017). Volatility clustering and herding behavior in a non-linear econometric model. The North American Journal of Economics and Finance, 39, 600-612.

- Sedaghati, S. (2016). Investor sentiment and stock market volatility: Evidence from the GCC stock markets. Research in International Business Finance, 37, 23-37.

- Shefrin, H., & Statman, M. (2000). Behavioral risk aversion and the pricing of risky assets. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(4), 1045-1085.

- Shiller, R. J. (2005). Irrational exuberance. Princeton University Press.

- Siestat, R. D., & Albuquerque, P. P. (2008). Herding and market capitalization. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 48(3), 425-438.

- Strand, R., & Freeman, R. E. (2015). Identifying and classifying stakeholders. Business Ethics Quarterly, 25(2), 265-296.

- Surowiecki, J. (2004). The wisdom of crowds: Why the many are smarter than the few. Little, Brown and Company.

- Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2008). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness. Yale University Press.

- The Presidency of the Arab Republic of Egypt. (2016). Egypt Vision 2030. Strategic Planning Unit of the Cabinet of Ministers. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Egypt_Vision_2030.

- Wang, J., Liu, C., Wei, S., & Fan, J. (2020). Green finance for green development: An international perspective. Management and Organizational Studies, 8(4), 142-155.

- Whyte, W. F. (1952). Dissenters: A study of relations between working class and middle class. The Free Press.

- Yamamoto, T. (2011). Herding and volatility clustering in emerging stock markets. Emerging Markets Review, 12(3), 320-337.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).