1. Introduction

Pain is a stressor that signals immediate danger or

threat to our physical and mental functionality [1,2].

In contrast to acute pain, which plays a protective role, chronic pain has a destructive

role and profoundly impacts various aspects of an individual's life and society

[3,4]. For this reason, in recent years,

researchers have focused their interest on finding ways to manage the factors

involved in the development and maintenance of chronic pain [4–6].

The experience of pain is formed under the

influence of three interconnected and interdependent aspects—sensory,

emotional, and cognitive [7]. Cognitive

processes in assessing the pain situation determine the individual's emotional

response. Usually, pain is associated with negative emotions such as fear,

depression, and anxiety, driven by sensory aspects (nociception) [8]. These form the basis of suffering during pain,

prompting individual’s to seek help [9]. Therefore,

a person's ability to effectively regulate their emotions provoked by acute

pain determines the extent of their suffering and pain resilience [10].

Perceiving acute pain as a threat (catastrophizing

pain) provokes fear and anxiety, which are significant predictors for increased

pain intensity and future disability in patients [11,12].

In most theoretical models of maladaptive behaviors in chronic pain, anxiety is

a major mediator in cognitive constructs such as catastrophizing,

hypervigilance, and avoidance of situations that could provoke pain [13,14]. The reinforcement of these behaviors over

time is associated with prolonged psychological stress, which becomes a

prerequisite to the development of depression, further amplifying the intensity

of pain and the suffering of the patient. Breaking this vicious cycle is a

cornerstone in pain management [15].

The depressive episode is a common comorbidity in

chronic pain, characterized by the presence of anxiety symptoms that can

sometimes escalate to a level of agitation (agitated depression). Even mild

symptoms of anxiety affect the depressive episode negatively and determine its

more severe course [16,17]. This clinical

picture indirectly demonstrates that stress is a fundamental link between pain

and depression [18]. According to Woo et al.

(2010), depression and pain should not be considered as separate dimensions due

to their interactive nature. We would add a third dimension – anxiety, as it

participates in every moment of pain, and its severity determines the evolution

of pain [16].

Although depression is often perceived as a normal

reaction to prolonged and debilitating pain, its underestimation carries risks

of future disability and auto-aggression [19,20].

Therefore, when evaluating patients with chronic pain, it is important to

examine not only the physical characteristics of pain, but also the emotional

ones – depression and anxiety – as they are interdependent variables of a

common phenomenon. A thorough study of the relationships between the sensory

and affective aspects of pain would contribute to the search for effective

approaches to manipulate them in the management of chronic pain. The aim of the

study is to determine whether there are correlations between depression,

anxiety (state and trait) and pain intensity in patients with chronic pain and

whether these interrelationships change with the addition of a depressive

episode.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a phase study, that proceeded in two

stages, during which data were collected using quantitative methods for

assessing patients with chronic pain, both with and without depressive episode.

2.1. Participants

The aim of the study was to recruit 120 patients

with chronic non-malignant pain using a random sampling method. The research

was conducted for a period of one year (from August 2019 to July 2020). The

participants were hospitalized patients undergoing treatment for chronic pain

in the clinics of neurology, rheumatology and psychiatry at UMBAL „St. Marina”

– Varna, Bulgaria. Two groups of patients between the ages of 24 and 75 were

included. The selection of participants was carried out according to the established

inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study. The inclusion criteria were: 1)

patients with chronic non-malignant pain and depression with a duration of pain

symptoms longer than three months and diagnosed with a depressive episode

according to the International classification of diseases tenth revision

(ICD-10) criteria; 2) patients with chronic non-malignant pain without clinical

data of depressive episode; and 3) signed informed consent for participation in

the study by the patient. All patients under the age of 18 and over 75,

pregnant women, patients with chronic malignant pain and patients who did not

sign an informed consent were excluded from the study.

All participants were previously informed about the

study procedures and signed an informed consent. The study was approved by the

Research Ethics Committee at the Medical University „Prof. Dr. Paraskev

Stoyanov“ – Varna, with Protocol/Decision № 85/26.07.2019.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

Several data collection methods were selected to

fulfill the research objectives. A working card was developed to collect: 1)

the demographic characteristics of the participants; 2) localization and

diagnostic category of chronic pain and the ongoing pain treatment; 3) data on

psychiatric comorbidity – diagnostic category, duration of illness and

treatment. The following tools were selected for the evaluation of the sensory

and affective aspects of pain: Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D-17),

Spielberger‘s State – Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and Visual analog pain

scale (VAS).

HAM-D-17 was used for assessing the symptoms of

depression. Nine of the symptoms (depressive mood, feelings of guilt,

suicidality, retardation in daily activity and work activity, agitation,

psychic anxiety, somatic anxiety, hypochondriacs) were estimated from 0 to 4.

The other eight symptoms (sleep disturbances, disturbances of sleep duration,

early awakening, gastrointestinal somatic symptoms, genital symptoms, general

somatic symptoms, weight loss, awareness of disease) – from 0 to 2. The total

score of the 17 items (range 0-52) reflects the severity of depression (0 to 7

– absence of depression; 8 to 16 – mild depression; 17 to 23 – moderate

depression and over 24 – severe depression) [21].

STAI was applied for the evaluation of anxiety. We

used an adapted form for Bulgarian conditions by D. Shtetinski and I.

Paspalanov. The questionnaire consists of two self-assessment scales, each of

which contains 20 statements. The Scale (S) for state anxiety (STAI – form Y1)

evaluates the emotional state and the reactions that arise in the individual

when perceiving a given situation as threatening, regardless of objective

reality like bad presentiments, a sense of danger, tension, nervousness and anxiety.

The Scale (T) for assessment of anxiety as a personal predisposition (STAI –

form Y2) evaluates how the person surveyed „feels overall.” The subjects

evaluate these statements by describing the intensity of their feelings on a

scale from 1 to 4 (likert scale). The total score for the both scales varies

from 20 to 80, where a score of up to 30 is considered for mild, 31 to 44 –

moderate, and over 45 as severe state or trait anxiety [22].

VAS is a 10-centimeter horizontal line with an

outline only at the beginning and at the end of the scale. At the beginning of

the scale there is no pain, and at the end – the strongest pain a person can

imagine. The participants mark their pain sensation, and the investigator

measures the distance from the beginning of the scale in centimeters or

millimeters. Thus, a digital expression of the intensity of pain is given. When

determining the degree of pain intensity, we use the following gradation: 0 - 0.4

cm - no pain, 0.5 - 4.4 cm - mild pain; 4.5 - 7.4 cm – moderate and 7.5 - 10 cm – severe pain [23].

2.3. Organization of the Study

The sample of 120 patients was divided into two

groups according to the presence of a depressive episode. The mental state of

the participants was assessed according to the ICD-10 criteria for a depressive

episode. During the first stage, all participants were examined using the

following methods: 1) filling in the work card; 2) HAM-D-17 to assess

depression severity; 3) Scale (S) for assessing state anxiety (STAI - form Y1)

and scale (T) for assessing trait anxiety (STAI - form Y2) from the Spielberger

questionnaire and 4) VAS for assessing pain intensity.

The second stage of the study was conducted three

months after the first. Both groups of patients were examined with the same

quantitative methods, except for the Spielberger’s scale (T) because we assume

that anxiety as a personality trait (trait anxiety) does not change during time

and remains constant characteristic.

2.4. Data Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS

software, version 22.0. The results were obtained through three analyses: 1)

descriptive statistics; 2) correlation analysis – to search for correlations

between the studied indicators in the two stages of the study; and 3) T – test

(Student’s T-test) to determine differences in the mean values between

indicators in different measurements.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

We studied 120 patients with chronic pain with a

minimum age of 24 years and a maximum age of 76 years. The mean age of the

participants was 51.90± 11.94. The gender distribution was uneven – the share

of women surveyed was 81.7% (n=98), and that of men – 18.3% (n=22).

Depending on the presence of clinically manifest

symptoms of depression according to the criteria for a depressive episode of

the ICD-10, the total sample was divided into two groups: 1) a group of 59

patients with chronic pain and no clinical data of a depressive episode and 2)

a group of 61 patients with chronic pain and symptoms within a depressive

episode. Both groups included patients with chronic pain of different origins:

chronic headache, chronic neuropathic pain, chronic visceral pain, chronic musculoskeletal

pain, chronic postoperative pain, chronic posttraumatic pain, and dysfunctional

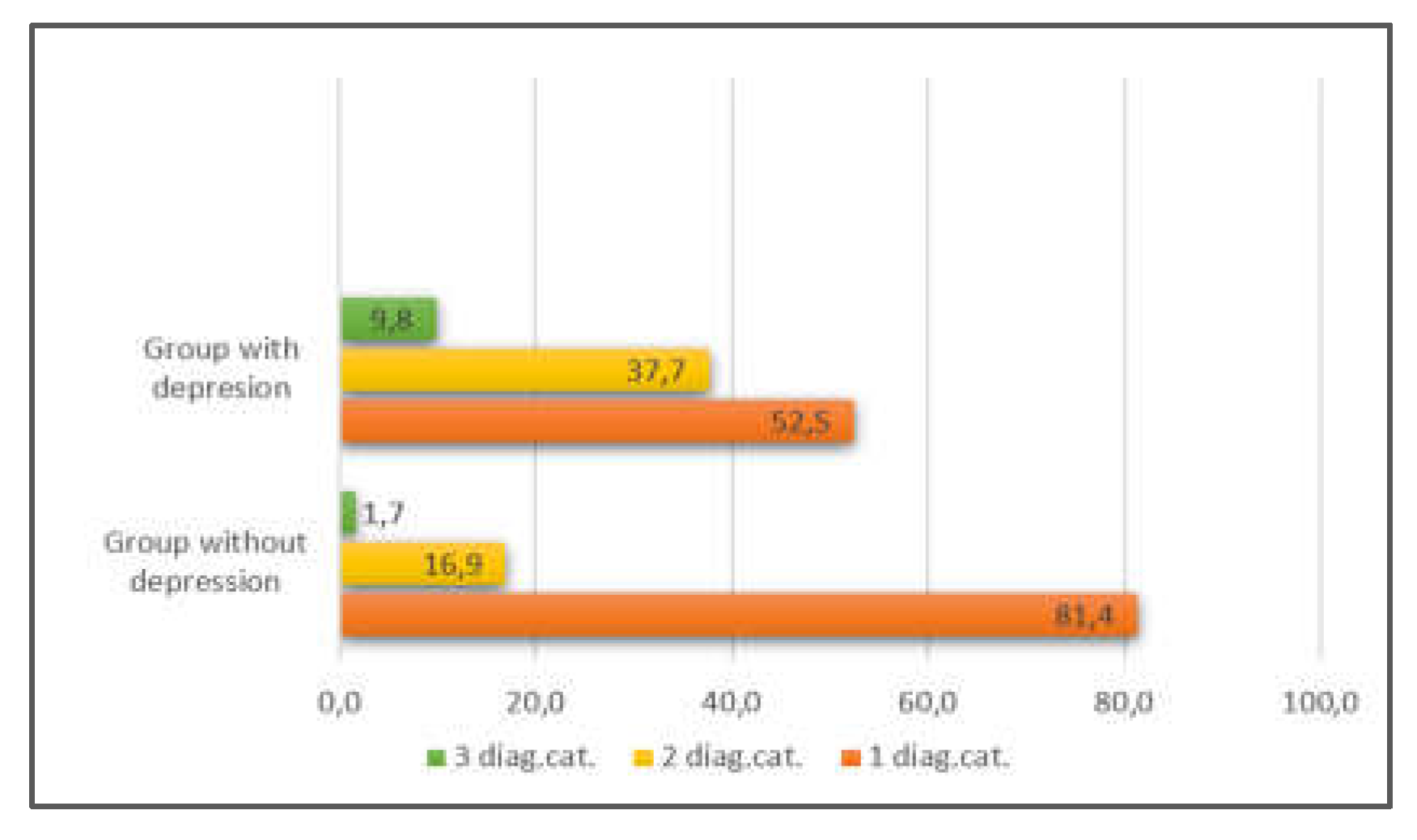

pain. The studied groups were distinguished by a different distribution in

terms of the number of localizations and the number of diagnostic categories of

chronic pain. The proportion of patients with more than one diagnostic category

was greater in the group with depression (47.5%) than in the group without

depression (18.6%) (

Figure 1).

The group distribution according to the number of

pain localizations showed that the proportion of patients with depression with

only one localization (49,2%) was greater compared to those without depression

(29,5%) (

Figure 2).

The results of the distribution of the group with

depression at the first stage according to antidepressant treatment showed that

73.78% (n=45) of them were on maintenance treatment, 18.03% (n=11) had

discontinued treatment for any reason, and 8.19% (n=5) never took

antidepressants. Within the study, all patients conducted maintenance treatment

with antidepressants.

The mean values of the studied indicators –

severity of depression (D), state anxiety (SA), trait anxiety (TA) and pain

intensity (PI) are represented in

Table 1.

The frequency distributions on the main scales were close to normal. In the

group with depression, there was a reduction in the mean values of all

indicators of the second stage of the study, the most pronounced being in the

indicator severity of depression (stage I: 16.15±5.87 – moderate; Stage II:

13,36±6,96 – mild). This group was characterized by high degrees of trait

(49.23±11.39) and state anxiety (50.15±13.90), the latter remaining high at the

second stage of the study (49.23±16.03). The pain intensity was moderate for

both stages of the study (stage I: 5.77±2.73; stage II: 5,26±2,58). The group

without depression had mild pain intensity and moderate degree of state and

trait anxiety at both stages. At the second stage, an increase in the severity

of depression and a decrease of the pain intensity were reported (Table 1).

3.2. Reliability of the Scales Used in the Study

The reliability factor Cronbach's alpha was calculated.

The coefficient was not calculated for HAM-D-17 as it does not imply a normal

distribution. It is clear from

Table 2

that the scales used during the two stages of the study had a high reliability

coefficient.

3.3. T-Test

In order to search for significant differences

between the pairs of indicators at the two stages of the study, a T-test

analysis was performed by groups. The indicator trait anxiety was not included

in the analysis, because it was examined only during the first stage. The

difference was significant only in the pair of indicators severity of

depression (t=3,323, p=,002) for the group with depression. For the group

without depression, the difference was significant only in the pair of

indicators of pain intensity (t=2,174, p=,034) (

Table 3).

3.4. Correlation Analysis

For the first stage of the study, the indicators are insignificantly related to each other in the group without depression (

Table 4). This tendency was preserved for the second stage of the study, except for the identified correlation between the severity of depression and the degree of state anxiety (

Table 5).

The correlation analysis of the scales in the group with depression differed significantly from that of the group without depression. There were significant correlations between all indicators (p < 0.01) at the first stage of the study. The highest was the correlation between depression severity (D) and pain intensity (PI), followed by the correlations between state (SA) and trait (TA) anxiety, between pain intensity (PI) and state anxiety (SA), between depression severity (D) and trait anxiety (TA), between depression severity (D) and state anxiety (SA) (

Table 6).

The analysis for the second stage of the study again showed significant correlations between all indicators, of which the highest was between depression severity and state anxiety, followed by that between depression severity and pain intensity and between pain intensity and state anxiety (

Table 7).

4. Discussion

4.1. Interrelations between Sensory and Affective Aspects of Pain

The age and gender distribution in the study sample of patients with chronic pain was uneven. The majority of them were between 45 and 66 years old, with the predominant share of women. Our results correspond with the literature data according to which the prevalence of chronic pain is greatest among the adult population after 40 years of age [

24]. Women report more severe pain, a higher number of pain conditions and depression, than men [

25].

The results of the study showed the presence of undiagnosed patients with a depressive episode, as well as those who discontinued their antidepressant therapy. Similar results were found in other authors' studies, which reveals the need for systematic monitoring of the mental state and treatment of patients with chronic pain [

26]. The group was distinguished by a high degree of state and trait anxiety, moderate severity of the depressive episode, and moderate pain intensity. After three months of treatment with antidepressants, the mean values of all indicators were reduced in the second stage, but this reduction was statistically significant only for the severity of depression.

In the group without depression, patients had moderate mean values of state and trait anxiety at both stages. At the second stage, the mean values of the indicators of severity of depression and pain intensity changed, but statistically significant was the reduction in pain intensity. This proved the effectiveness of the pain treatment.

The results revealed that anxiety symptoms accompanied both groups of patients. Tension, anxiety, and premonitions of impending danger were found to occur more frequently in patients with chronic pain and depression than without depression [

27,

28]. Some authors accept state anxiety as a prognostic factor in pain manifestation and related disability [

29,

30]. High trait anxiety was defined as a nonspecific measure of the development of negative affectivity (depressive and anxiety symptoms) [

31]. Other authors associate high trait anxiety with more intense symptoms of anxiety and pain. They proved that degrees of state and trait anxiety have a cumulative effect on the subjective sensation of pain [

32].

Trait anxiety is defined as the stable tendency to perceive a wide range of situations as dangerous or threatening, which provokes the manifestation of negative emotions (fears, worries and anxiety). It is part of the personality bipolar dimension neuroticism versus emotional stability and is associated with a tendency to worry about health and often complaint somatic symptoms. The greatest influence on the degree of state anxiety is the less real danger associated with the situation, but the way one perceives the situation [

22]. Results from a study by S. Kadimpati et al. (2015) revealed that neuroticism as a personality trait was independently associated with pain-related anxiety and catastrophizing [

33]. A tendency to catastrophize pain has been thought to influence the increase of state anxiety and lower pain tolerance [

34]. These data reveal the need for more evidence for the prognostic role of high trait anxiety in the manifestation of depression in patients with chronic pain.

Interrelations between the sensory and affective components of pain were established by correlation analysis. The correlation only showed that variations in one variable were accompanied by variations in another. The analysis of the studied indicators in the group without depression showed non-significant relationships at the both stages of the study. In other words, single depressive symptoms that did not reach the degree of depressive episode did not show relationships with mild intensity of pain and with moderate anxiety. The correlation analysis of the studied indicators showed significant correlations between all indicators during the two stages of the study i.e. the presence of a depressive episode changed the relationships between the indicators. For example, Rogers et al. (2015) also found correlations between the three indicators, but found the link between pain and depression was unique [

35]. A meta-analysis of studies of patients with chronic osteoarthritis pain sharing symptoms of depression and anxiety demonstrated a significant correlation between pain and severity of depression and anxiety [

36]. Different results are presented by other authors who found that changes in the level of anxiety or depression had a low to moderate impact on pain reduction. They examined a sample of patients with fibromyalgia treated with pregabalin alone. They link reduced pain mostly to the direct effect of treatment, rather than an indirect effect mediated by improving symptoms of anxiety or depression [

37]. Given that fibromyalgia is often accompanied by a depressive episode, the reduction of pain intensity would not be a sufficient factor to reduce depression, but a treatment aimed at it [

38]. Correlations with different measures and polarity were found by Linton and Götestam (1985). They examined psychological factors (anxiety and depression) and objective characteristics of pain for each of the 16 patients in the study, suggesting that the relationship between these variables may not be as strong [

39]. This indicates a high degree of individual variability in correlations for each patient, emphasizing the need for a tailored approach in managing depression, anxiety, and pain intensity factors.

Our results demonstrate the applicability of the scales used to monitor sensory and affective aspects of pain in comorbid patients with chronic pain and depressive episode. The HAM–D–17 scale is a tool for assessing the severity of depression in patients with a depressive episode. The results showed that in the group without a depressive episode there were patients with single depressive symptoms (score between 1 to 6), whose expression did not reach the degree of a mild episode. The presence of subthreshold symptoms of depression could not be assessed with the chosen scale, which may be the reason for a lack of correlations with the other indicators. Subthreshold symptoms alone represent a risk for a depressive episode [

40,

41]. Therefore, it is necessary to apply screening tools to search for depressive symptoms with a high degree of sensitivity, including subthreshold ones. Their research and analysis are part of the assessment of suicidal risk, which depends more on psychosocial factors than physical aspects of pain [

42].

4.2. Scientific Relevance

Our research is further evidence of the strong interrelationships between affective and sensory aspects of pain in patients with chronic pain and depression. It also reveals the need to actively search for symptoms of depression given the high suicidal risk in these patients. It presents perspectives in the following directions 1) to seek correlations between subthreshold levels of depression and pain intensity; 2) to investigate the influence of high trait anxiety on the evolution of acute pain into chronic pain and 3) to investigate the specific correlations between affective and sensory aspects of pain in different diagnostic categories of chronic pain. This data can be beneficial for the effective management of chronic pain.

4.3. Limitations

This study has several shortcomings. The sample size was not large enough to form more groups of patients with similar clinical characteristics of chronic pain. The etiopathogenesis of different categories of chronic pain are differentially related to depression. We suggest that for the different diagnostic categories of chronic pain, differences in the correlations between the affective and sensory aspects of pain would also be found. The social factors (support, working environment, employment, etc.) and the occurrence of another additional stressor between the two stages of the study, which would have an impact on the mental state of the patients and respectively on the pain. Another limitation concerns the time frame of the study, which applies to both stages and does not apply beyond the specific moment of the study.

5. Conclusions

The interrelationships between sensory and affective aspects of pain are stronger when a depressive episode occurs. The strength in correlations depend on the change in the severity of the depressive episode, which also determines their dynamics. Further research is required to understand the role of subthreshold depressive symptoms in predicting the prognosis of patients with chronic pain. In-depth study of the correlations between the sensory and affective aspects of pain and their dynamics may provide clues on how to reduce the burden of the chronic pain patient.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the Medical University „Prof. Dr. Paraskev Stoyanov“ – Varna, with Protocol/Decision № 85/26.07.2019.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to their private nature, and our ethical approval prevents us from sharing data beyond named collaborators. Further inquiries can be directed to the author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Panerai, A.E. Pain emotion and homeostasis. Neurol. Sci. 2011, 32, S27–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmers, I.; Quaedflieg, C.W.E.M.; Hsu, C.; Heathcote, L.C.; Rovnaghi, C.R.; Simons, L.E. The interaction between stress and chronic pain through the lens of threat learning. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2019, 107, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grichnik, K. P.; Ferrante, F. M. The difference between acute and chronic pain. Mt. Sinai. J. Med. 1991, 58, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mills, S.E.E.; Nicolson, K.P.; Smith, B.H. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e273–e283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şentürk, İ.A.; Şentürk, E.; Üstün, I.; Gökçedağ, A.; Yıldırım, N.P.; İçen, N.K. High-impact chronic pain: evaluation of risk factors and predictors. Korean J Pain. 2023, 36, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armstrong, R.A.; Fayaz, A.; Manning, G.L.P.; Moonesinghe, S.R.; Peri-operative Quality Improvement Programme (PQIP) delivery team; Oliver, C. M.; PQIP collaborative. Predicting severe pain after major surgery: a secondary analysis of the Peri-operative Quality Improvement Programme (PQIP) dataset. Anaesthesia. 2023, 78, 840–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moayedi, M.; Davis, K.D. Theories of pain: from specificity to gate control. J. Neurophysiol. 2013, 109, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, A.H.; Farris, S.G. A meta-analysis of the associations of elements of the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain with negative affect, depression, anxiety, pain-related disability and pain intensity. Eur. J. Pain. 2022, 26, 1611–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loeser, J.D. Pain and suffering. Clin. J. Pain. 2000, 16, S2–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Aranda, D.; Salguero, J.M.; Fernández-Berrocal, P. Emotional regulation and acute pain perception in women. J. Pain. 2010, 11, 564–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swinkels-Meewisse, I.E.J.; Roelofs, J.; Oostendorp, R.A.B.; Verbeek, A.L.M.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S. Acute low back pain: pain-related fear and pain catastrophizing influence physical performance and perceived disability. Pain. 2006, 120, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, R.K.; Kneeland, E.T.; Edwards, R.R.; Jamison, R.; Weiss, R.D. Pain catastrophizing and distress intolerance: prediction of pain and emotional stress reactivity. J. Behav. Med. 2020, 43, 623–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zale, E.L.; Ditre, J.W. Pain-related fear, disability, and the fear-avoidance model of chronic pain. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 5, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrini, L.; Arendt-Nielsen, L. Understanding Pain Catastrophizing: Putting Pieces Together. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 603420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meda, R.T.; Nuguru, S.P.; Rachakonda, S.; Sripathi, S.; Khan, M.I.; Patel, N. Chronic pain-induced depression: a review of prevalence and management. Cureus. 2022, 14, e28416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, A.K. Depression and Anxiety in Pain. Rev. Pain. 2010, 4, 8–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De La Rosa, J.S.; Brady, B.R.; Ibrahim, M.M.; Herder, K.E.; Wallace, J.S.; Padilla, A.R.; Vanderah, T.W. Co-occurrence of chronic pain and anxiety/depression symptoms in U.S. adults: prevalence, functional impacts, and opportunities. Pain. 2024, 165, 666–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Epel, E.S.; Crosswell, A.D.; Mayer, S.E.; Prather, A.A.; Slavich, G.M. , Puterman, E.; Mendes, W.B. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Front. Neuroendocrinol. 2018, 49, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meints, S.M.; Edwards, R.R. Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018, 87, 168–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chytas, V.; Costanza, A.; Mazzola, V. , Luthy, C.; Bondolfi, G.; Cedraschi, C. Demoralization and Suicidal Ideation in Chronic Pain Patients. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 611–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, M. A rating scale for depression. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1960, 23, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press: Palo Alto, CA, 1983, pp. 24–36.

- Jensen, M.P.; Chen, C.; Brugger, A.M. Interpretation of visual analog scale ratings and change scores: a reanalysis of two clinical trials of postoperative pain. J. Pain. 2003, 4, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansfield, K.E.; Sim, J.; Jordan, J. L.; Jordan, K.P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of chronic widespread pain in the general population. Pain. 2016, 157, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munce, S.E.; Stewart, D.E. Gender differences in depression and chronic pain conditions in a national epidemiologic survey. Psychosomatics. 2007, 48, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Choi, E.J.; Nahm, F. S.; Yoon, I.Y.; Lee, P.B. Prevalence of unrecognized depression in patients with chronic pain without a history of psychiatric diseases. Korean J. Pain. 2018, 31, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnan, R.R.K.; France, R.D.; Pelton, S.; McCann, U.D. , Davidson, J.; Urban, B.J. Chronic pain and depression. II. Symptoms of anxiety in chronic low back pain patients and their relationship to subtypes of depression. Pain. 1985, 22, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poleshuck, E.L.; Bair, M.J.; Kroenke, K.; Damush, T.M.; Tu, W.; Wu, J.; Krebs, E.E.; Giles, D.E. Psychosocial stress and anxiety in musculoskeletal pain patients with and without depression. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry. 2009, 31, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feeney, S.L. The relationship between pain and negative affect in older adults: anxiety as a predictor of pain. J. Anxiety Disord. 2004, 18, 733–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegraeff, J.M.; Kan, R.; van Trijffel, E.; Reneman, M.F. State anxiety improves prediction of pain and pain-related disability after 12 weeks in patients with acute low back pain: a cohort study. J. Physiother. 2020, 66, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knowles, K.A.; Olatunji, B.O. Specificity of trait anxiety in anxiety and depression: Meta-analysis of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2020, 82, 101928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Gibson, S.J. A psychophysical evaluation of the relationship between trait anxiety, pain perception, and induced state anxiety. J. Pain. 2005, 6, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadimpati, S.; Zale, E.L.; Hooten, M.W. , Ditre, J.W.; Warner, D.O. Associations between Neuroticism and Depression in Relation to Catastrophizing and Pain-Related Anxiety in Chronic Pain Patients. PloS one. 2015, 10, e0126351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cimpean, A.; David, D. The mechanisms of pain tolerance and pain-related anxiety in acute pain. Health Psychol. Open. 2019, 6, 2055102919865161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, H.L.; Brotherton, H.T.; de Luis, A.; Olivera-Plaza, S.L.; Córdoba-Patiño, A.F.; Peña-Altamar, M.L. Depressive symptoms are independently associated with pain perception in Colombians with rheumatoid arthritis. Acta Reumatol. Port. 2015, 40, 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca-Rodrigues, D.; Rodrigues, A.; Martins, T.; Pinto, J.; Amorim, D.; Almeida, A.; Pinto-Ribeiro, F. Correlation between pain severity and levels of anxiety and depression in osteoarthritis patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021, 61, 53–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, L.M.; Leon, T.; Whalen, E.; Barrett, J. Relationships among pain and depressive and anxiety symptoms in clinical trials of pregabalin in fibromyalgia. Psychosomatics. 2010, 51, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yepez, D.; Grandes, X.A.; Talanki Manjunatha, R.; Habib, S.; Sangaraju, S.L. Fibromyalgia and depression: a literature review of their shared aspects. Cureus. 2022, 14, e24909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linton, S.J.; Götestam, K.G. Relations between pain, anxiety, mood and muscle tension in chronic pain patients. A correlation study. Psychother. Psychosom. 1985, 43, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juruena, M.F. Understanding subthreshold depression. Shanghai Arch. Psychiatry. 2012, 24, 292–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Stockings, E.A.; Harris, M.G.; Doi, S.A.R.; Page, I.S.; Davidson, S.K.; Barendregt, J.J. The risk of developing major depression among individuals with subthreshold depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies. Psychol. Med. 2019, 49, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racine, M. Chronic pain and suicide risk: а comprehensive review. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018, 87, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).