1. Introduction

Sustainable music learning has a unique educational system that is different from other professional education systems. Its uniqueness lies in the influence of multiple subjective factors, such as emotions, personality, personal habits, etc. This inclusion reflects the recognition of the holistic benefits of music in cognitive development and overall music education. However, while there is a plethora of research on sustainable music learning system, and most of them are concentrated in the field of pedagogy, which is mostly from the perspective of teachers [

1,

2,

3]. And these research that addresses the learning issues more theoretically based on the category of knowledge taught by teachers [

4,

5]. However, unlike other disciplines, where sustainable music learning system involves performance and skill training, which is different with other disciplines that only requires knowledge. Psychological factors play a very important role in performance and skill training, which will directly affect students' subjective feelings and learning efficiency [

6]. Music learning system, as a category of art teaching, is directly constrained by the complex psychological system and behavioral activities of individuals. This requires researchers to analyze the psychological complex activities in music learning systems, in order to provide more research materials to the field of sustainable music education [

7]. In a lot of Chinese musicians’ opinion, sustainable music learning experiences are always full of struggle and frustration. There are some studies focused on why the children and adolescents in ceased or continued playing musical instruments. The reasons are mostly concentrated in factors such as "repetitive training” and” dealing with mistakes” [

2,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Furthermore, students have their own practical experiences and feelings towards sustainable learning music. In addition, there is a certain difference between the actual learning outcomes and their own feelings that students receive through systematic education. In previous studies, this difference has been overlooked, and there have been few theoretical analyses from the perspective of quantitative model system.

It has been shown in some study that fear of making mistakes is likely to be an important factor influencing negative learning experiences. Focusing on the field of public education, in The Fearless Classroom: A Practical Guide to Experiential Learning Environments, Joli Barker stresses that teachers should create a fearless atmosphere for students and allow mistakes to happen in the classroom [

8,

26]. A similar point is made in the area of mathematics; teacher Stanley P. Izen also claims that making mistakes is a necessary step in the learning process, and that teachers should guide students in how to learn from mistakes [

27]. In the music field, as William Westney proposes in his book The Perfect Wrong Note, mistakes are valuable, and we need to cherish the information that mistakes are trying to impart. During the process of dealing with mistakes, he states that we need to pay attention on how our body feels [

28,

29,

30]. Once we feel the physical freedom, it will lead us to the breakthroughs [

31,

32]. In the other words, when our body feels free, we can achieve effortless playing without fear. For reaching fearless and free performance, Mildred Portney Chase presented several approaches in her timeless book Just Being at the Piano. One of the significant perspectives according to Chase is to bypass the self-conscious barrier by creating a harmony of mind and body [

33]. This was also mentioned in jazz pianist Kenny Werner’s book Effortless Mastery, in which he describes finding a quiet inner space where we can relax and have an open-minded focus; this leaves no room for fear, and flow appears [

5,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. These views match with Timothy Gallwey’s understanding of the mental side. Through the book Inner Game of Tennis, tennis pro Timothy Gallwey reveals his own unique understanding of the concept for reaching peak performance by balancing the physical and mental sides in the process of coaching tennis [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45]. This book has become a phenomenon and has been used in a variety of fields. Unlike most studies, in the quasi-autobiographical book Never Too Late, public education visionary John Holt described the effect of fear on his studies through his own experience as an adult amateur studying the flute: he loses his learning ability at the moment when he feels fear [

46,

47,

48,

49]. " This experience resonates with a significant number of Chinese students whom I have encountered, underscoring the prevalence of similar situation related to fear in the learning experience within this demographic. Universality of these issues suggests a broader concern that extends beyond individual cases, emphasizing the need for a comprehensive psychology analysis study [

50].

This study aims to explore the factors that influence music learning system from a psychological perspective, and innovatively constructs a combination of qualitative and quantitative approaches. Firstly, a questionnaire survey was conducted to obtain some representative influencing factors of students on the psychological level of music learning system. Secondly, a quantitative model system was established; Furthermore, establish a quantitative model for the actual learning outcomes of students, in order to comprehensively and quantitatively analyze weight ratio of specific influencing factors in influencing personal sustainable music learning system.

The objective of this paper is to study the effect of psychological emotions and academic performance on music learning system based on stochastic nonlinear system. The main contributions of this paper include the following:

1. The most prominent innovation of this study lies in the construction of a quantitative model system for psychological influencing factors of sustainable student music learning system and a quantitative model system for actual learning effect. Through quantitative analysis of the model, the weight values of several negative emotions on music learning system are obtained. This research model system has never been seen in previous studies and is a breakthrough in this study.

2. Existing research mainly looks at several factors that affect fragmented music learning system from perspective of teachers' teaching rules, emphasizing phased teaching state and learning goals of teachers as main body, thus ignoring sustainable music education and students, who are a large group of music learning objects. The research fills gap in this type of research object, focusing on sustainable music learning system from an emotional perspective and students who occupy a dominant position in music learning system, so as to more accurately explore impact of their emotional influencing factors on music learning system.

3. The aim of research is to introduce the concept of stochastic nonlinear system into the level of psychological analysis [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62,

63], achieve interdisciplinary integration, and promote a deeper understanding of the impact of psychological factors on sustainable music learning system. This is more effective and innovative than traditional social surveys and research methods.

This study emphasis on the " sustainable music learning system" signals a student-centric approach. Understanding how students perceive, engage with, and navigate their music education journey is a valuable angle that complements existing research, which may sometimes focus more on pedagogical methods or institutional structures. Also, this study uniquely narrows its focus to college-level students. The factors influencing music learning system at collegiate level may differ significantly from those at other educational stages. The purpose is to identify the factors that influence the music learning experience of Chinese college students and to seek out some strategies that can help the students enjoy the music learning process. By identifying influential factors, the study can contribute in-sights that are directly applicable in refining music teaching methods, curriculum design, and support systems for college students. This targeted approach adds a distinctive dimension to the existing body of literature. it likely addresses contemporary issues and trends in the field of music education in a specific cultural and educational context. The research stands out due to its specific focus on college students in China, its comprehensive examination of diverse factors shaping sustainable music learning experience, and its potential to contribute contextually relevant insights with practical applications for music educators. These characteristics collectively position the study as a unique and valuable contribution to the existing body of research in music learning system.

2. Methodology of Survey

2.1. Participants

Based on previous research findings in music learning system [

10,

15,

20,

21,

22,

30,

41,

42,

43,

44,

45], as well as papers from various aspects of psychology and education [

35,

36,

37,

38,

42], this study has developed this survey questionnaire, which includes several representative questions in the field of music learning system. It is particularly noteworthy that it focuses on psychological and emotional aspects of music learners, drawing on relevant questionnaire forms in the field of psychology, and striving to truly reflect the actual psychological activities of music learners.

The target sample consisted of 100 individuals who participated in the research in 2023. The participants are studying in Hangzhou Normal University and Wuhan University of Communication in China, representing a range of Chinese college music students. There were 74(76.3%) females and 23 (23.7%) males. All the students already have more than 5 years music learning experiences and some of them have more than 10 years music learning experiences. The concept of psychological needs was used as a theoretical framework for the pre-sent investigation. A psychological needs perspective is a concise way to unify the findings and conclusions of music learning system research, as well as to explain the findings of the current study.

2.2. Data Collection and Procedure

All participants were recruited within one week and administered questionnaires over the following two weeks. The importance of the study was communicated to participants, emphasizing the voluntary and anonymous of their participation.

This study developed the questionnaire outline through a comprehensive process of internal testing and external review. Subsequently, a psychologist was involved to review the interview outline and provide valuable feedback. Several music students who did not participate in the follow-up questionnaire study were invited to provide feedback. Then the questionnaire survey was established.

The questionnaire mainly adopts the form of open-ended questions. It mainly covers four aspects: (1) Basic personal information, including gender and grade of the participant; (2) Participants briefly describe their own sustainable music learning experience and give scores (3) Reasons for positive or negative music learning experience (4) How to overcome difficult times. All the data collection through online anonymous questionnaire system.

2.3. Questionnaire

1. What is your gender?

2. What grade are you?

3. Briefly describe your sustainable music learning experience and rate it from 1 to10. (1 means extremely enjoyed;10 means extremely painful.)

4. What are the elements may affect your sustainable positive learning experience?

5. What are the elements may affect your negative learning experience?

6. How did you overcome the difficulties in the process?

2.4. Data Analysis

We have got 97 answers back from 100 participants. There were 74(76.3%) females and 23 (23.7%) males. 90 Undergraduate and 7 graduate students.

The questionnaire results indicate that half of the students surveyed reported negative experiences in sustainable music learning journey. It's interesting to note that, based on the feedback we got, there doesn't seem to be a clear difference in the distribution of participants across different academic levels in the undergraduate students. Considering that the number of graduate students participating is small (only 7 students), the conditions for grade-based differentiation analysis are not met.

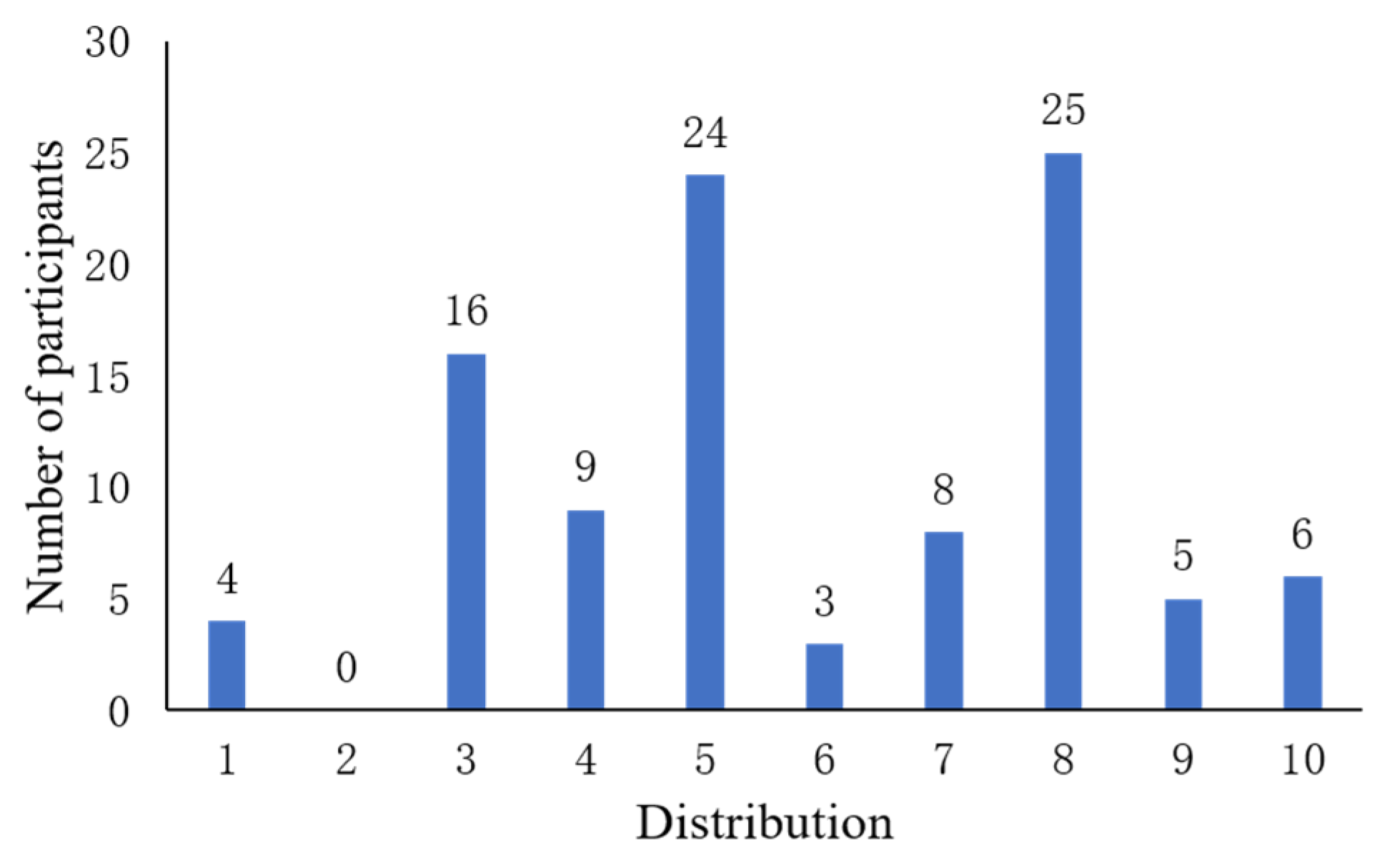

By collecting the results of the questionnaire survey, the distribution of all scores was obtained, and

Figure 1 reflects this distribution.

1 point: 4 participants

2 points: 0 participants

3 points: 16 participants

4 points: 9 participants

5 points: 24 participants

6 points: 3 participants

7 points: 8 participants

8 points: 25 participants

9 points: 5 participants

10 points: 6 participants

2.5. Distribution Analysis:

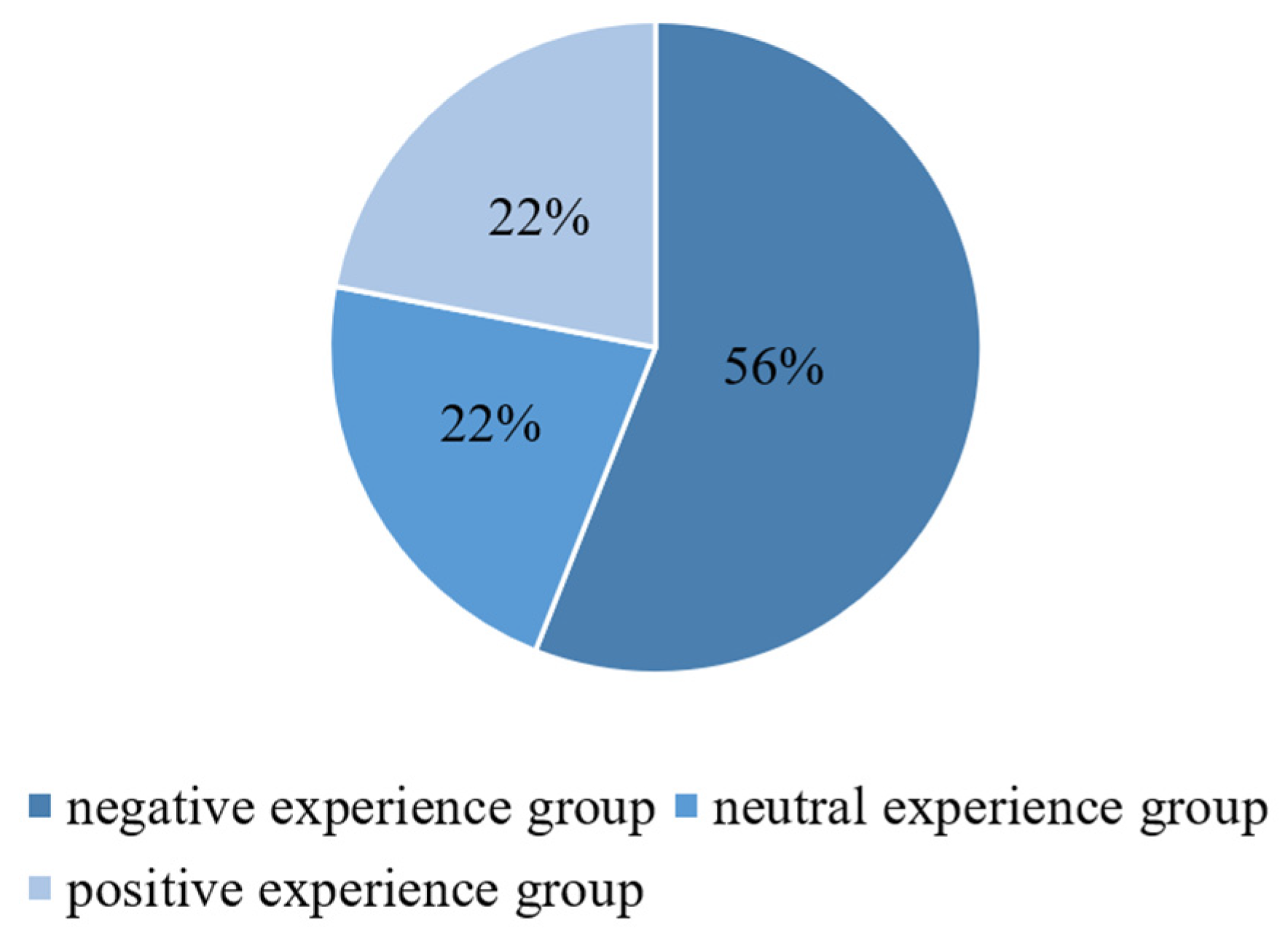

There are a large number of participants clustered around three specific rating, it may indicate a common sentiment within the group, which are 3 points,5 points and 8 points. If we divide the scores into three groups, negative experience group (below score 5) 29 students, neutral experience group (at score 5) 24 students, and positive experience group (above score 5) 47 students (see

Figure 2). we can easily tell nearly half of the students rated their music learning experience as positive, however, there is still almost 1/3 participants thought their learning experience is negative.

Although the numerical summaries provide valuable information, understanding context and personal perspectives is crucial to a full analysis of participants' sustainable music learning system. Considering open ended questions can provide insight into the reasons behind certain ratings, we methodically analyzed all answers and refined the factors that appeared frequently in participants' answers as influencing their sustainable music learning experiences and their corresponding adjectives and nouns. The most effective representative reasons all have undergone rigorous statistical and classification analysis in order to conduct a more comprehensive and in-depth discussion.

3. Exploration of Quantitative Model System for Emotional Factors

In previous studies, scholars have mostly quantitatively analyzed the research objects and data from a statistical perspective. Statistical analysis can certainly yield certain research results, but it lacks the core elements that fundamentally explain the problem being studied.

This paper creatively investigates the quantitative impact of emotional factors on music learning system from the perspective of constructing a quantitative model system. Through the construction of a quantitative model system, the study strives to explain the results of the collected survey questionnaire from multiple emotional dimensions. By comparing data with actual music learning effects, a real sustainable music learning model system is fitted to provide a relatively quantitative range of key parameters that affect music learning and education.

Based on the analysis of the survey questionnaire results, the reasons for the negative experiences described by the participants were all very similar. Even among the score 8 group with the largest number of people, the reasons that caused them to feel frustrated during the learning process were surprisingly consistent with the negative group and the neutral group. The primary reasons emerged as potential contributors to these negative experiences: fear of making mistakes and judgement from instructors, and high expectations leading to frustration.

We conduct a quantitative model system analysis on the three emotional factors mentioned above. Firstly, it is necessary to assign certain values to each factor and set corresponding value ranges based on actual research conditions and logical characteristics o music learning system. Through quantitative analysis, reveal the causes of negative experiences and learning gaps in music learning system, explore influencing factors and solutions.

3.1. Parameter Setting of Emotional Factor Quantification Model System

Setting a value range can combine the emotional quantification model system with the final results of the survey questionnaire for data-driven matching. This approach cleverly transforms the scoring strategy of the questionnaire into an analysis of the quantitative model, which helps to identify the underlying emotional logic that influences music education. This study fits the emotional model obtained through scoring into a nonlinear state space system. By synthesis and linear fitting of independent and dependent variables, a set of linearized quantitative system models can be obtained as follows

where

, set

to represent feel proportions of fear,

to represent feel proportions of expectation, and

to represent feel proportions of purposeful practice.

and

are the system states of sustainable music learning model system, the control input and the measurable output of the system;

is the high-order of the systems, and

is defined as in (1);

is the unmeasurable state vector.

represents the emotional score result of the survey questionnaire and range of values (output negative factors) is

,

represents the model errors caused by other reasons (Other factors beyond the three). Meanwhile, we set

as the actual music learning score of a certain student. And through proportional operation, its value range is also controlled within the range of 0 to 1, which helps in the construction of emotional quantification models. Finally, the comprehensive score

is obtained by fitting the emotional score

and academic performance score

by using the least squares method.

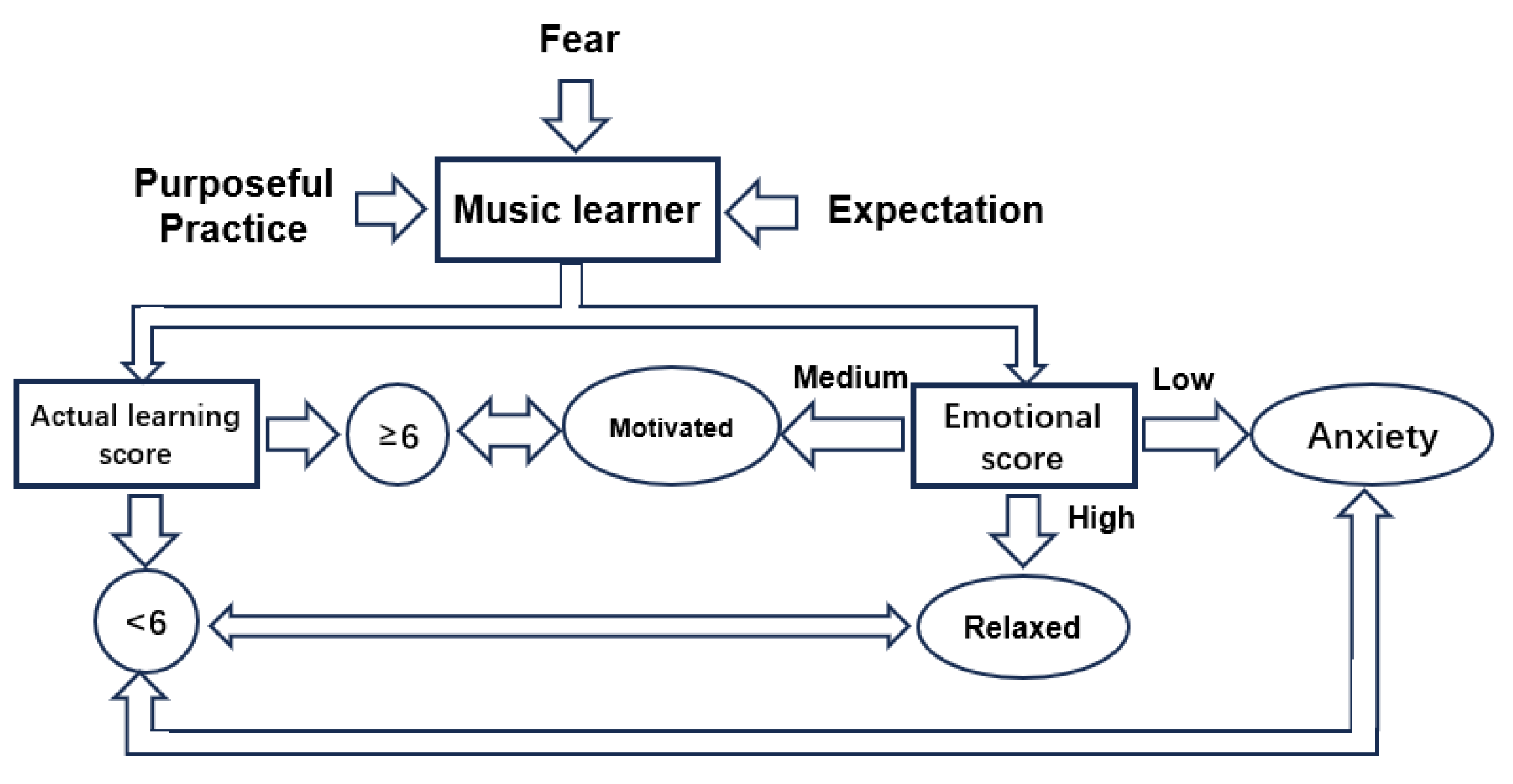

4. Design of a Quantitative Model System for Emotional Factors

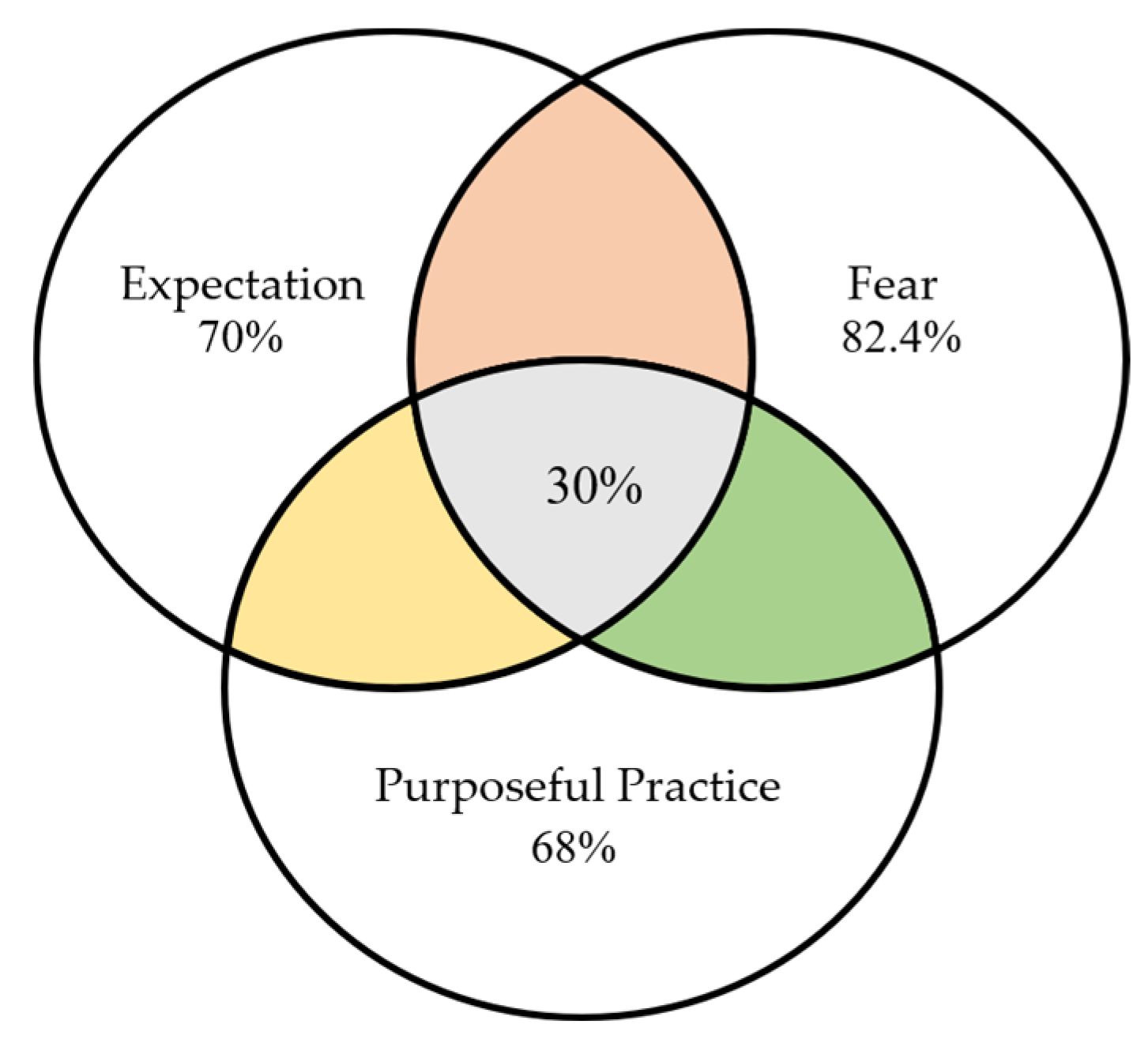

According to the survey results, the most frequently cited factors influencing a sustainable positive learning experience were practicing effectively, gaining a sense of accomplishment. This corresponds exactly to the three factors of negative experiences. High efficiency in practicing piano against fear of making mistakes, a sense of accomplishment corresponds to frustration at not meeting expectations (see

Figure 3).

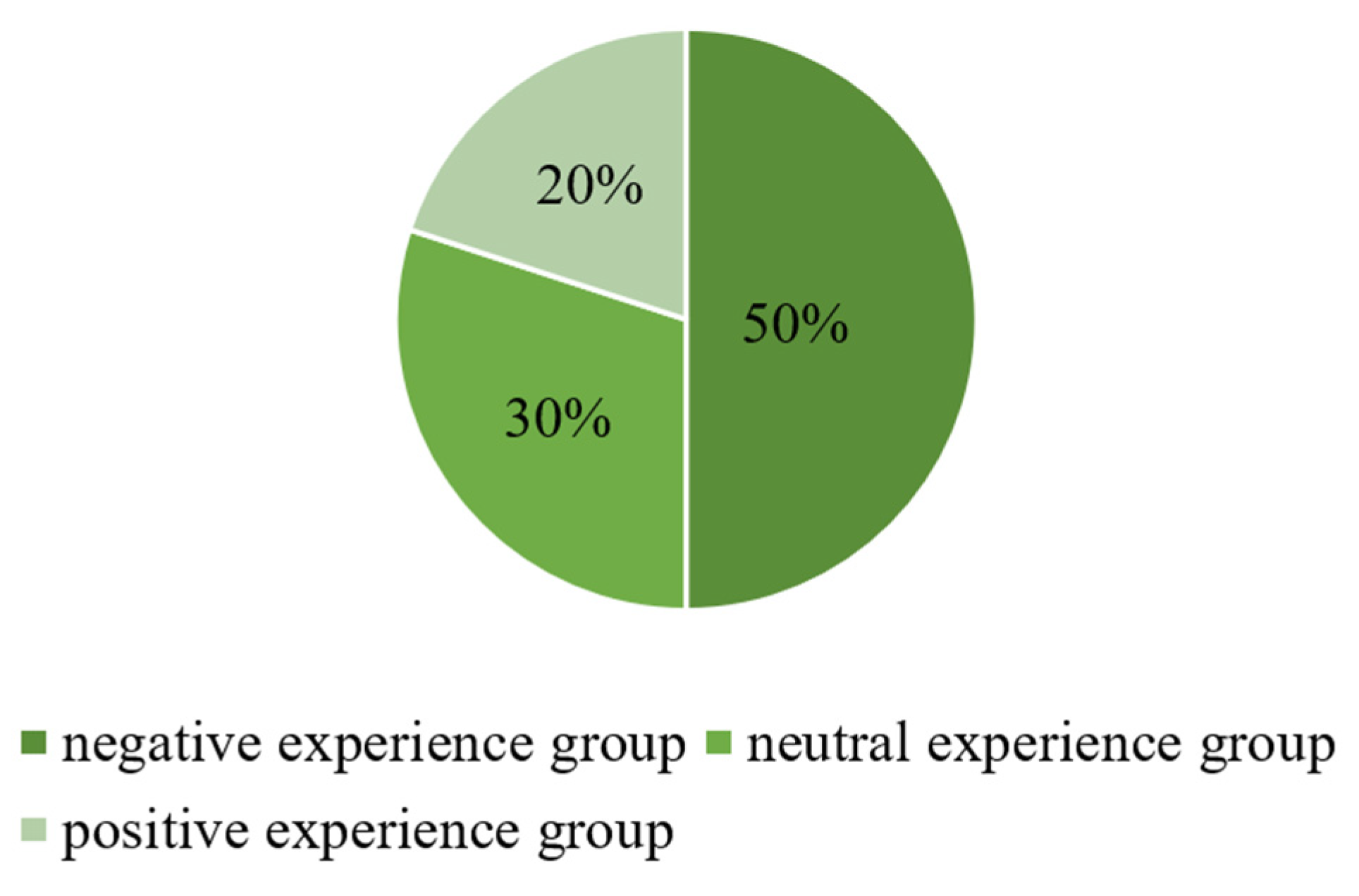

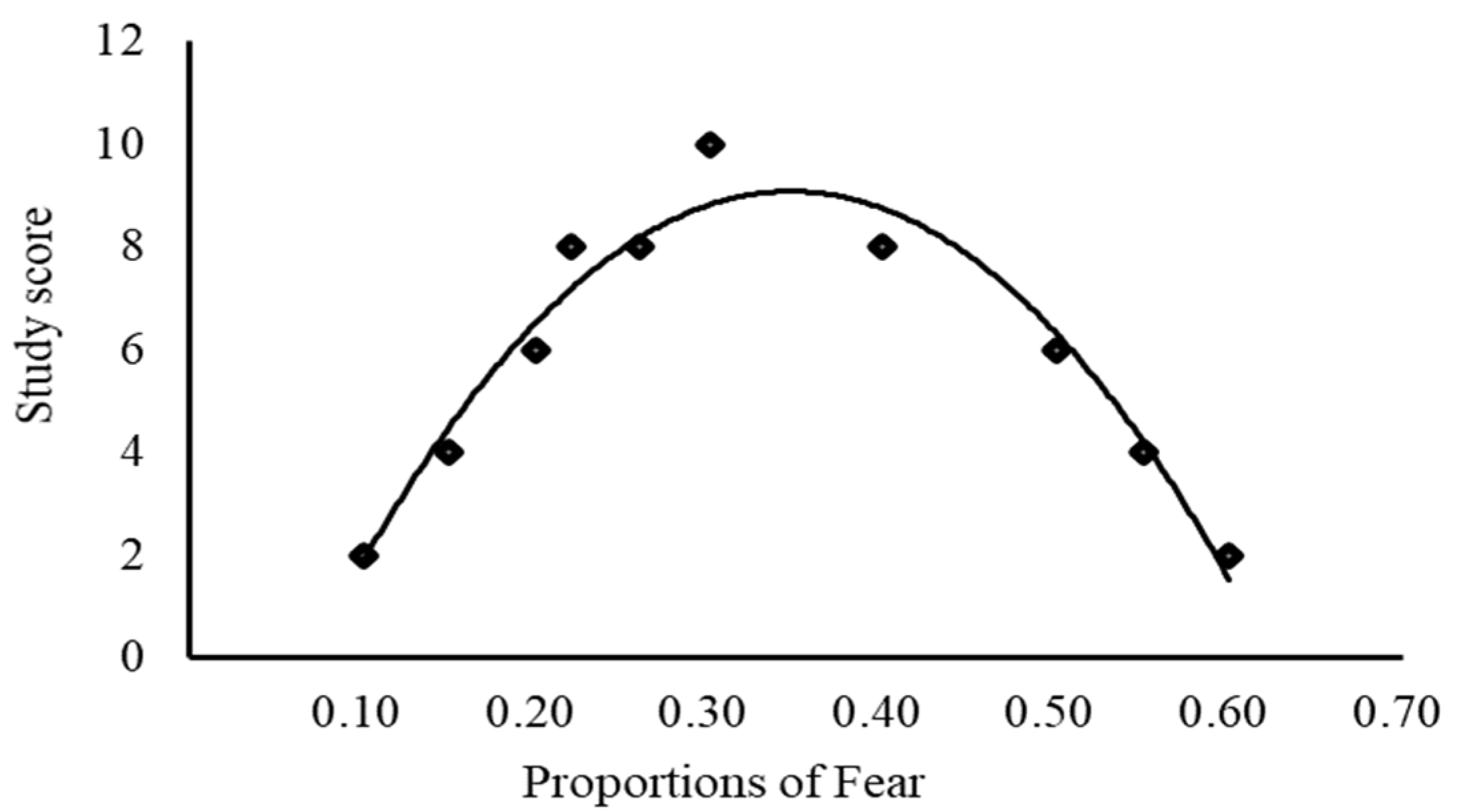

4.1. Fear

A significant proportion of students expressed a fear of making mistakes and the associated judgment from their peers or instructors. The word “fear” appeared in the descriptions of 82.4% students; 87.5% students from negative experience group consider the fear is the biggest obstacle in sustainable music learning. This fear may hinder their willingness to take risks, explore new techniques, or express themselves freely in their musical pursuits. By analyzing the questionnaire results data of each student one by one, we can easily obtain the following data distribution results (see

Figure 4).

According to the principle of proportionality in data analysis, and based on specific emotional factors, we have selected several representative students to answer and express in proportion.

Negative experience group:

S2: I do not like playing the piano because I'm afraid of making mistakes.

S47: I'm afraid of playing the wrong note. I stop a lot during the playing and it's hard to enjoy.

S71: I’m afraid of having lessons, and I’m afraid that I’ll be criticized by the teacher if I don’t make progress. I hate practicing, and practicing is so tiring.

S93: Always making mistakes, cannot practice well, hate practicing, and afraid of being criticized.

Neutral experience group:

S24: Afraid to having lesson because I’m afraid of playing something wrong in the lesson.

S59: Frequent mistakes made my fingers stiff, and I was afraid to have a lesson with teacher.

Positive experience group:

S35: I am afraid of learning new piece because I’ll make a lot of mistakes. But once I have learned piece, I will start enjoying playing it.

S67: I do not like making mistakes, I hope I can play the piece perfectly, but I know that is impossible.

According to the principle of proportional expansion, this article fits a scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Fear) on emotional score

as follows (see

Figure 5)

Dealing with mistakes is a necessary part of learning experience. Unfortunately, many students and musicians are trying to avoid making mistakes even the students from the positive experience group, because they feel bad and ashamed when they make mistakes. In the other words, they refuse to accept where they are in the learning process and are not being honest with themselves. In the book The Perfect Wrong Note, William Westney discusses the positive value of mistakes: “Honest mistakes are not only natural, they are immensely useful [

26,

27,

28,

50]. Truthful and pure, full of specific information, they show us with immediate, elegant clarity where we are right now and what we need to do next. This is why a particular wrong note can indeed be thought of as perfect.” [

3,

24,

25,

26,

27]

To understand how to deal with mistakes is crucial to musicians. Cognitive psychology plays a significant role in understanding how individuals perceive and respond to the fear of making mistakes, several cognitive processes contribute to the experience of this fear, such as: cognitive appraisal, cognitive distortions, and self-efficacy beliefs and attribution processes. Children learning to walk fall down repeatedly. However, there is no feeling of embarrassment or negativity, and no one laughs or passes judgments. The understanding prevails that failing is an essential step in the learning process, requiring time for children to master this new skill. As adults, judgment tends to arise for momentary failures or simple mistakes. The forgetting of the time learning takes and the necessity of failing initiates self-blame before the final moment of success. Once judgment begins, a vicious cycle starts, worsening the situation. Timothy Gallwey, the author and developer of a new success model, emphasizes that establishing a self-identity based on negative judgments leads to role-playing that hides true potential. In short, individuals become what they think.

Individuals engage in cognitive appraisal, where they assess situations and their own abilities. In the context of music education, cognitive appraisal in-volves evaluating the significance of making a mistake during a performance or practice session. Negative appraisal, such as viewing mistakes as catastrophic or indicative of personal failure, can intensify the fear. Cognitive distortions are irrational thoughts or beliefs that contribute to negative emotions. In the context of music education, individuals may engage in cognitive distortions such as overgeneralization (e.g., believing one mistake ruins the entire performance), catastrophizing (imagining the worst possible outcome), or personalization (attributing mistakes to personal inadequacy). These distortions amplify the fear of making mistakes. Individuals with low self-efficacy may perceive mistakes as indicative of their lack of competence, intensifying the fear. Musicians may experience moments of self-doubt, feeling not smart or skilled enough. This doubt often stems from a single mistake. On stage, performers might think a mistake destroys the beauty of the entire piece, although the audience usually forgives such errors immediately. The exaggeration of one's mistakes, compared to others, is attributed to a judgmental mindset distorting the fact. The simple fact is playing a wrong note; additional self-doubt and judgment are self-created. Gallwey argues that ending judgment means neither adding nor subtracting from the facts. Starting self-judgment distorts facts and adds questionable meanings to events.

Objective dealing with mistakes and problems is possible without self-judgment. This lack of emotional distress enables better concentration and faster problem-solving. Making and feeling positive changes during play and achieving sub-goals inspire a willingness to spend time addressing problems in the learning process. In Effortless Mastery, Kenny Werner asserts that a musical life translates into fearless expression: moving from one note to another, seeking unity with one's inner self, and unlocking an ocean of music for others to replenish their spirits. The entire learning process becomes a joyful game when the student observes without attachment to results but with one-pointed focus.

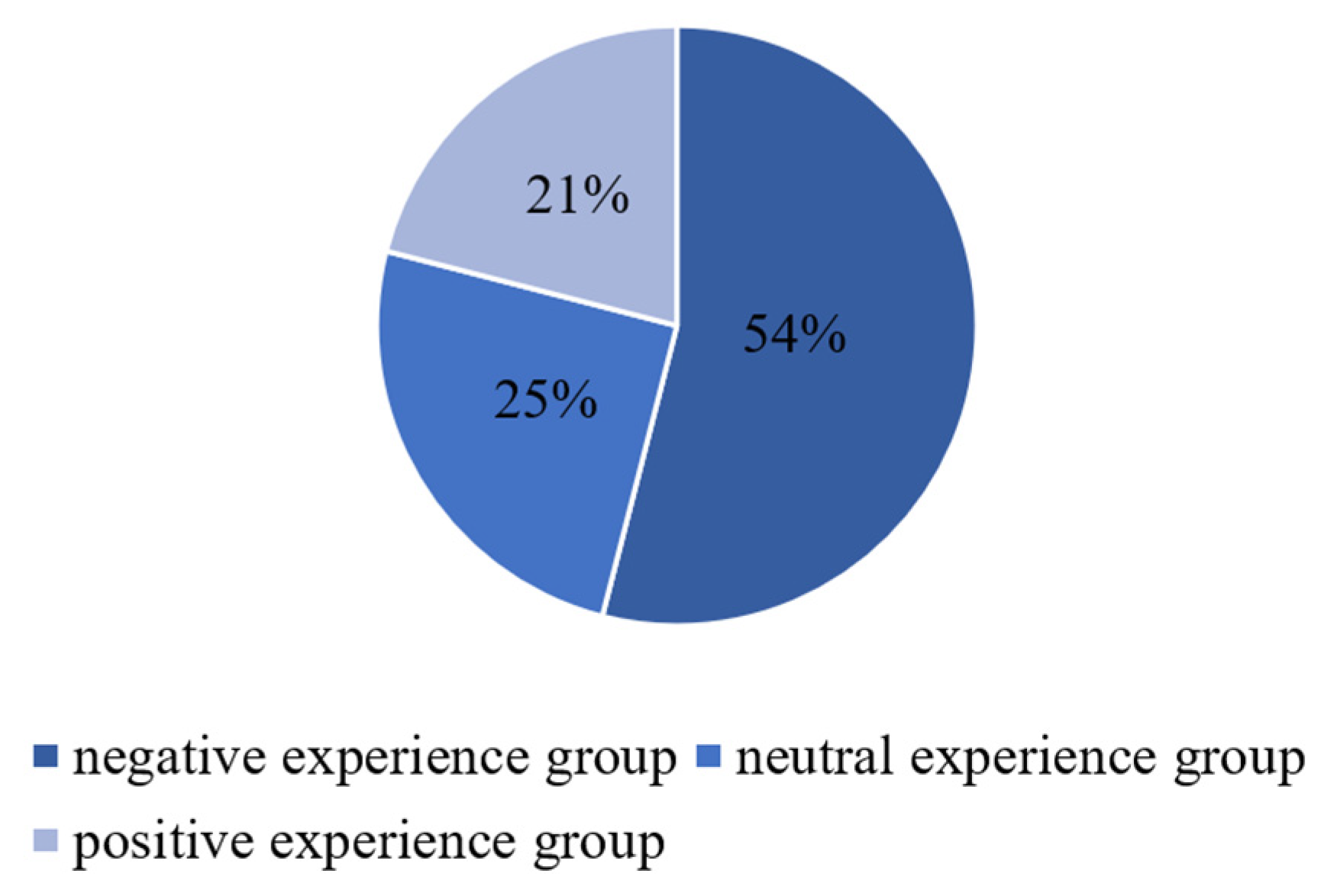

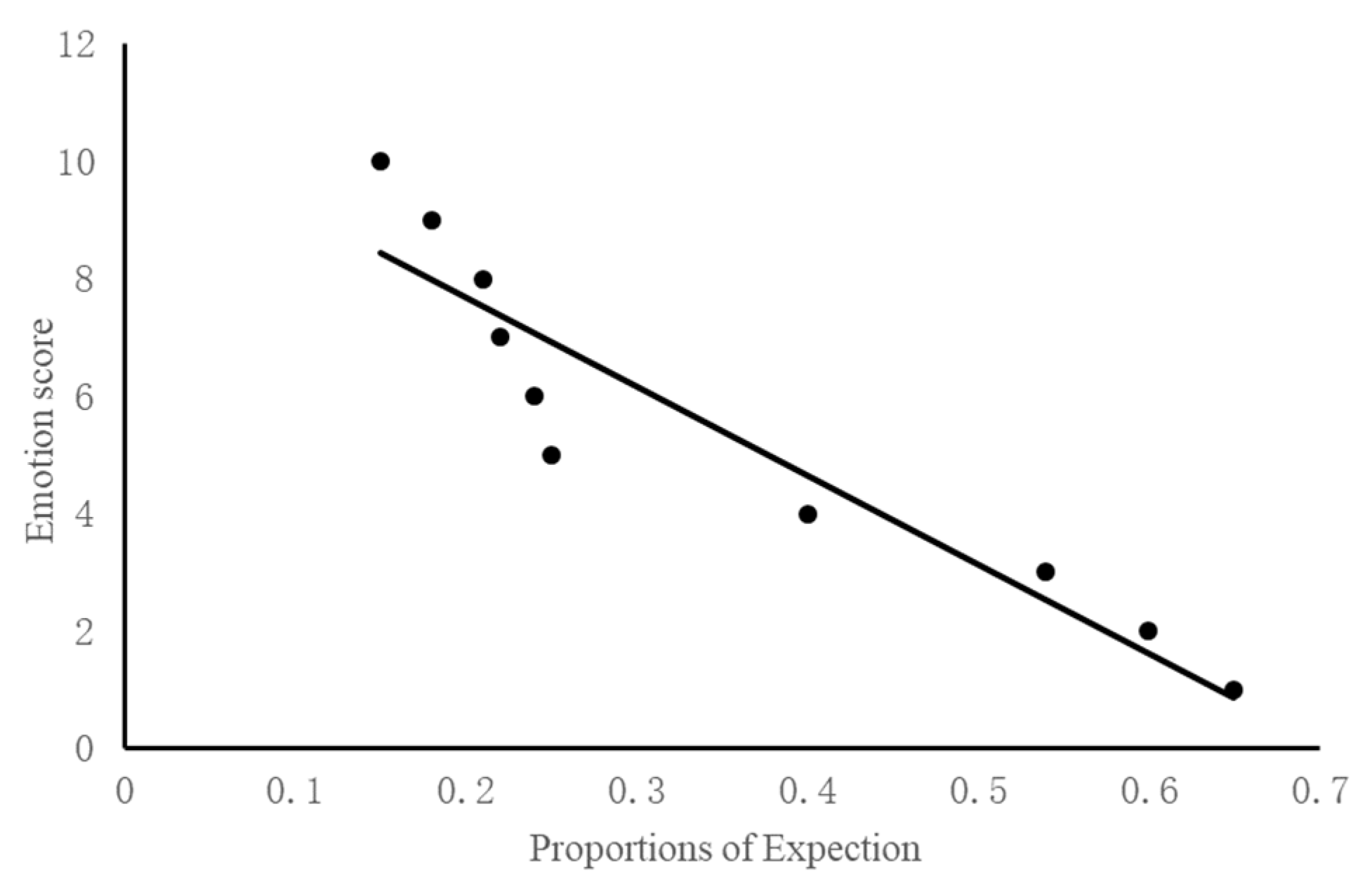

4.2. Expectation

Another prevalent factor contributing to negative experiences is the high expectations students have set for themselves. The data suggests that when students fall short of their self-imposed goals, they experience frustration. By analyzing the questionnaire results data of each student one by one, we can easily obtain the following data distribution results (see

Figure 6).

According to the principle of proportionality in data analysis, and based on specific emotional factors, we have selected several representative students to answer and express in proportion.

Negative experience group:

S4: I am always a slow learner, and I always make mistakes, unable to meet the goal.

S19: There has been no progress for a long time. I am always very slow in reading music and cannot master new skills.

S53: My progress in practicing piano is slow, I always fall behind other students.

S82: I practiced each measure seriously for a long time but still couldn't get it right. My fingers couldn't keep up with my brain, and my muscles weren't flexible enough to meet the requirements of the piece.

Neutral experience group:

S12: The early stage of learning music is a bit difficult, but it gets better later.

S76: Reading music is painful.

Positive experience group:

S51: I always play poorly in front of the teacher, and I feel like I will fail when I go on stage.

S84: It’s disappointing when you can’t play it well no matter how hard you practice.

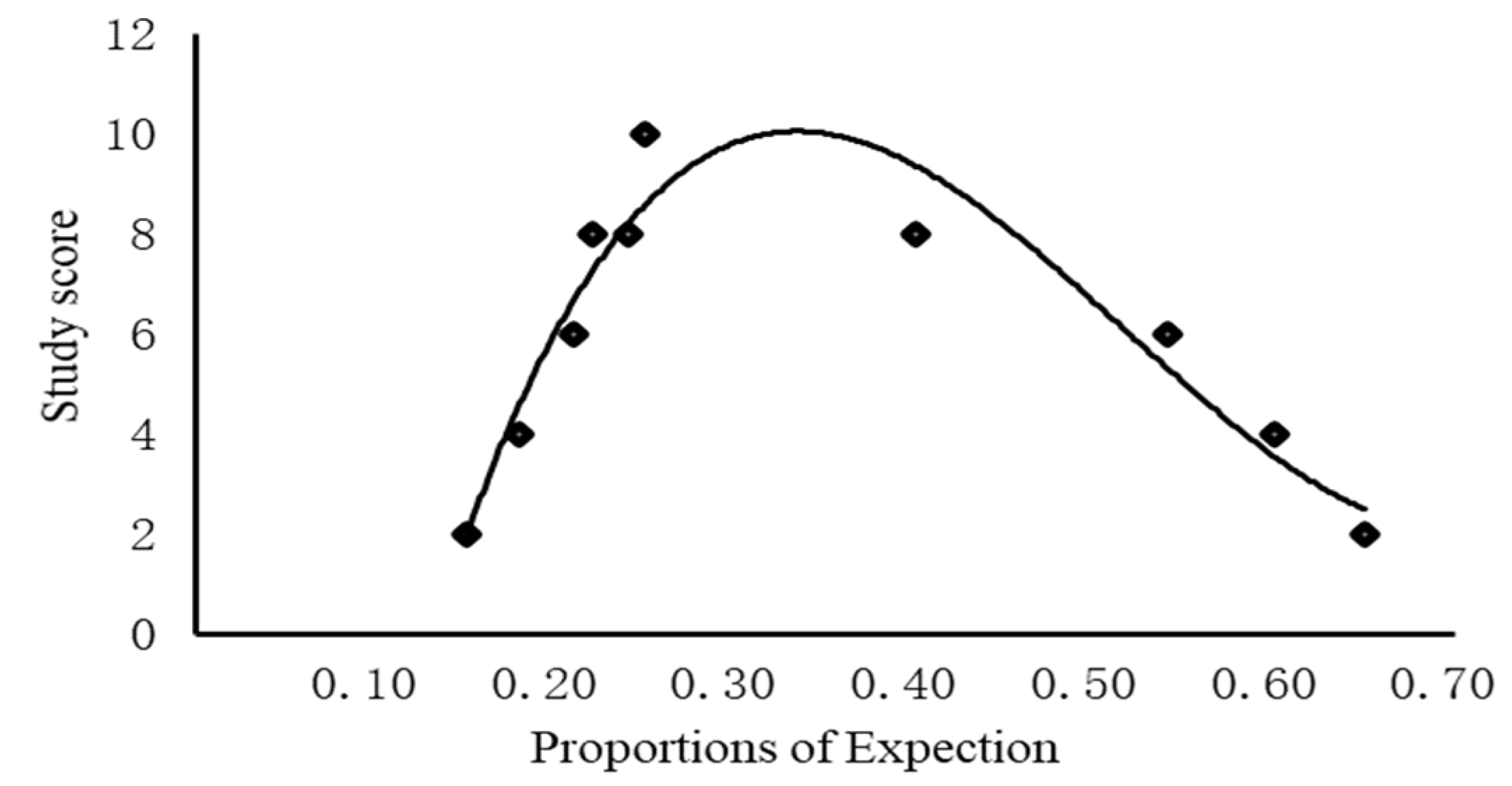

According to the principle of proportional expansion, this article fits a scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Expectation) on emotional score

as follows (see

Figure 7).

Many research in expectation field is focused on explore the origins and nature of these high expectations, as they might stem from external pressures or internal perfectionism. However, from the data collected, students are still feeling frustrated even they are not chasing the perfection. Bandura's Social Cognitive Theory emphasizes the role of self-efficacy, the belief in one's ability to succeed in specific situations [

66]. High expectations may be linked to high self-efficacy, but unrealistic expectations can lead to a mismatch between perceived ability and actual performance, resulting in frustration. Implementing strategies to manage expectations, providing realistic goal-setting guidance, and promoting a growth mindset could mitigate frustration and enhance the overall learning experience.

Goal setting is a well-established area in educational psychology. Locke and Latham's Goal Setting Theory posits that specific and challenging goals lead to higher performance than vague or easy goals [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

45]. From the data mentioned above, students’ expectations are often simple or vague, and according to their description, such as “I am always a slow learner.”” My progress in practicing piano is slow.” “My fingers couldn't keep up with my brain, and my muscles weren't flexible enough to meet the requirements of the piece.” Emphasizes the importance of setting clear and specific goals. Specific goals provide individuals with a clear direction and a well-defined target to aim for. They offer clarity about what needs to be achieved, reducing ambiguity, such as: “To be able to play this phrase in tempo 72 without stop.” In addition, just setting clear goals is not enough for students to get rid of frustration during the learning process. In the process of completing this goal, students should also pay attention to simplifying each small goal so that they can only focus on one thing at once. This refers to the term “implementation intention,” which research shows has a strong positive impact on goal achievement and only occurs when a person is focused on a single goal. Peter M. Gollwitzer pointed out in the article "Implementation Intentions" that "Implementation intentions are formed to facilitate the conversion of goal intentions into actions. Goal intentions can be defined as instructions that people give themselves to perform specific behaviors or achieve certain desired results." Students can Completing each step naturally and effortlessly instead of getting frustrated and struggling with multitasking; this increases their self-esteem and will motivate them to complete more and more challenges.

Understanding what to expect from the learning process is crucial to the musicians. Expectations have to be rational. Setting a goal is important in the learning process, but expectation of success in every moment is not necessary. During the learning process, students definitely need to deal with mistakes and problems, and they might fail or succeed. Focusing on the result itself all the time will make us emotional and cause obstructions to learning. Therefore, instead of having a high expectation for the result, students need to have an open mind ready to accept whatever happens in the moment, without judgment. It is honest feedback of playing that shows where the players truly are in the learning process. Only when the students are honest with themselves and accept the facts, they can clearly see how much they need to improve and what the real problems are (along with their solutions). Curiosity and good feedback help them figure out how can they make it better than last time. Mildred Portney Chase wrote, “You may come to a learning situation with expectations but without self-acceptance.” She goes on to say, “If we do not expect to have knowledge at the outset, we are open to the desire to know and explore and discover and grow. If we can simply accept where we are for the moment, then we are freed from self-condemnation. [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38]”

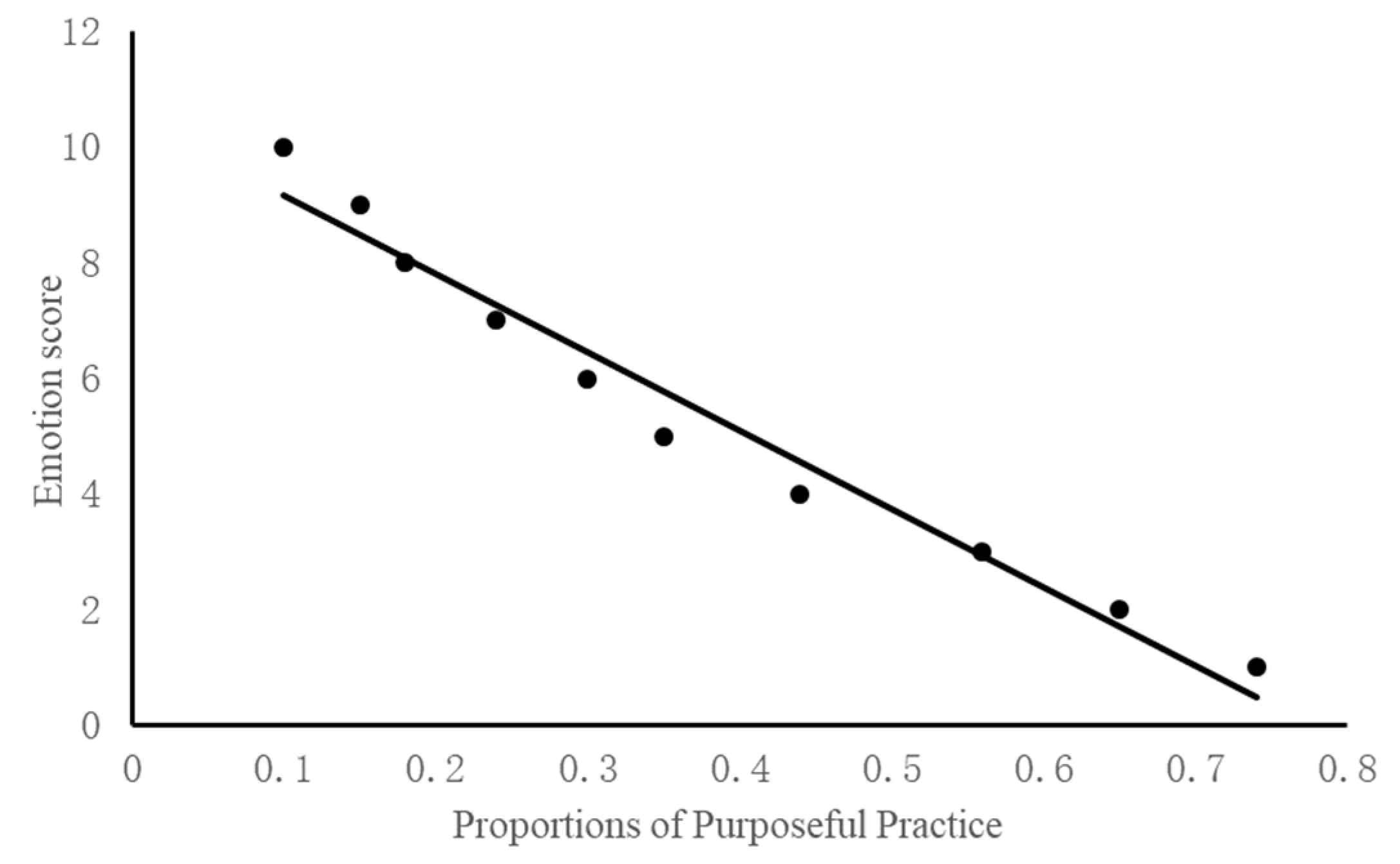

4.3. Purposeful Practice

In the data, 86.2% students from negative experience group shows they thought practicing is boring and requires a lot of time, 70.8% students from the neutral experience group and 55.3% students from positive experience group express that they also struggled during practice time. Musicians are often inundated with the importance of practice, yet the elusive question of how to practice effectively remains largely unaddressed. The paradox arises when students, grappling with uninspiring and time-consuming practice sessions, question the very essence of this crucial aspect of musical mastery. The misconception that practice is a tedious and arduous endeavor has led to a lack of enthusiasm and engagement among many aspiring musicians. The concept of purposeful practice emerges as a beacon of transformative learning—a method that not only demystifies the art of practice but also infuses it with intention, focus, and efficiency. By analyzing the questionnaire results data of each student one by one, we can easily obtain the following data distribution results (see

Figure 8).

According to the principle of proportionality in data analysis, and based on specific emotional factors, we have selected several representative students to answer and express in proportion.

Negative experience group:

S6: Practicing is so boring.

S28: It always takes a long time to practice piano and I feel very tired.

S42: The progress of practicing is very slow. It has been a long time, but the progress is not obvious.

S64: I always get distracted when practicing the piano.

S89: Sometimes, even if you practice a few measures for a long time, you won't be good at it, and even you did it in the end it may not keep the same at next day.

Neutral experience group:

S22: Practicing takes a lot of time, and I would not practice when I’m busy.

S49: Practicing piano is always very hard.

Positive experience group:

S31: Practicing is always difficult when you can't find a way.

S67: Practicing is inherently boring, so it’s understandable that you just have to endure it.

According to the principle of proportional expansion, this article fits a scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Purposeful Practice) on emotional score

as follows (see

Figure 9).

Many participants think practicing means spending a huge amount of time in the practice room; however, quantity is not the main factor that can help students achieve effective practice both quality and efficiency are crucial for this purpose. Achieving effective practice requires that every step in the learning process be purposeful. Purposeful practice, a concept popularized by psychologist Anders Ericsson, refers to a specific type of practice that is focused, intentional, and aimed at improving performance. This form of deliberate and structured practice has implications for students' learning experiences. Purposeful practice emphasizes efficiency. Students are encouraged to identify weaknesses, set specific goals, and work on targeted exercises to address those areas. This efficiency in practice can lead to more significant improvements in a shorter amount of time, positively impacting students' perceptions of their music learning experience.

As students experience tangible progress through purposeful practice, their confidence in their abilities is likely to grow. Success in targeted areas reinforces a positive self-perception, creating a sense of competence and mastery. This, in turn, contributes to a more positive and fulfilling learning experience.

As mentioned above at expectation section, setting clear and achievable goals also important to the purposeful practice. This process of goal setting provides students with a roadmap for their musical development. Attaining these goals becomes a source of motivation and accomplishment, shaping a positive learning environment. Purposeful practice encourages adaptability by focusing on addressing specific challenges. As students encounter new difficulties or areas for improvement, they learn to adapt their practice strategies to meet evolving needs. This adaptability contributes to a dynamic and responsive learning experience. By incorporating purposeful practice into the practice routine, students can enhance the effectiveness and meaningfulness of their learning experiences, ultimately contributing to their growth as musicians.

In "Intelligent Music Teaching," Robert A. Duke delineates crucial aspects for music educators, including what to teach, assessment, sequencing instruction, feedback, and more [

26,

27,

28,

50]. An exploration of teaching approaches within the book unveils numerous strategies suitable for purposeful practice, as practice inherently embodies a process of self-teaching. Duke's chapter titled "What to Teach" expounds on setting goals for learners, positing goal setting as an effective means to enhance practice. Within the domain of piano learning, two goal categories emerge: long-term and short-term goals. A long-term goal, such as playing a sonata's first movement smoothly, can be optimally approached by breaking it down into manageable short-term goals, promoting a more achievable practice routine. The alignment of appropriate goals becomes imperative, as inappropriate goals can render practice monotonous or fraught with challenges. Therefore, the ability to set judicious goals facilitates efficient time management and pacing in our practice sessions. Goals, as dynamic entities, are subject to adjustment during practice sessions, and assessment becomes a pivotal tool for understanding our current standing in the learning process. Assessments, conducted at any practice point, necessitate honesty and acceptance of observed facts. Monitoring progress through feedback allows us to gauge whether problems persist or have been resolved, as succinctly stated by Duke: "assessment is 'finding out.' Feedback and grading are 'communicating what you’ve found out.'" Post-assessment, crucial decisions arise, particularly regarding the alteration of goals, especially short-term ones. Adjusting goals prompts the creation of a plan, equivalent to Duke's concept of "sequencing instruction," a familiar practice for music teachers guiding students step by step. In purposeful practice, this responsibility falls on the individual, necessitating meticulous planning to ensure each step leads cohesively to the final goal. The strategic adjustment of steps, whether advancing, skipping, or revisiting, becomes paramount to avoiding unnecessary detours and optimizing progress toward our objectives. In essence, every move within this self-guided process serves the ultimate purpose, emphasizing the avoidance of time wastage on steps incongruent with the goals.

4.4. Emotional Quantification Model System Results

According to the fitting results of the three independent emotional variables on the emotional score

, Choosing Lyapunov function

, applying

,

,

, it can be concluded that

This indicates that the model has a high degree of fit, and

-tests were conducted on each variable, with

-values all less than zero, indicating a significant impact. Finally, the fitted emotional quantification model is

5. Design of a Quantitative Model System for Actual Music Learning

The emotional analysis results based on the questionnaire certainly reflect some factors that affect sustainable music learning and education, but these analyses are based on the subjective answers of each student, which is full of uncertainty. In order to reveal the essential logic of how emotions affect sustainable music learning at a deeper level, we searched for the actual sustainable music learning scores of each surveyed student, which are relatively easy to obtain.

It should be emphasized that the emotional score obtained by a student through a survey questionnaire does not show a progressive relationship with their actual music learning performance. For example, a student's self-rating for emotional factors in music learning is 10, but their actual academic performance is very irrational, only 4.

Based on the above analysis, this article sets

as the actual sustainable music learning score of each surveyed student, and converts it into a value range between 0 and 1 through proportional quantification. Similar to the method in the third and fourth sections, we can also fit the scatter plot of individual factors on the learning score

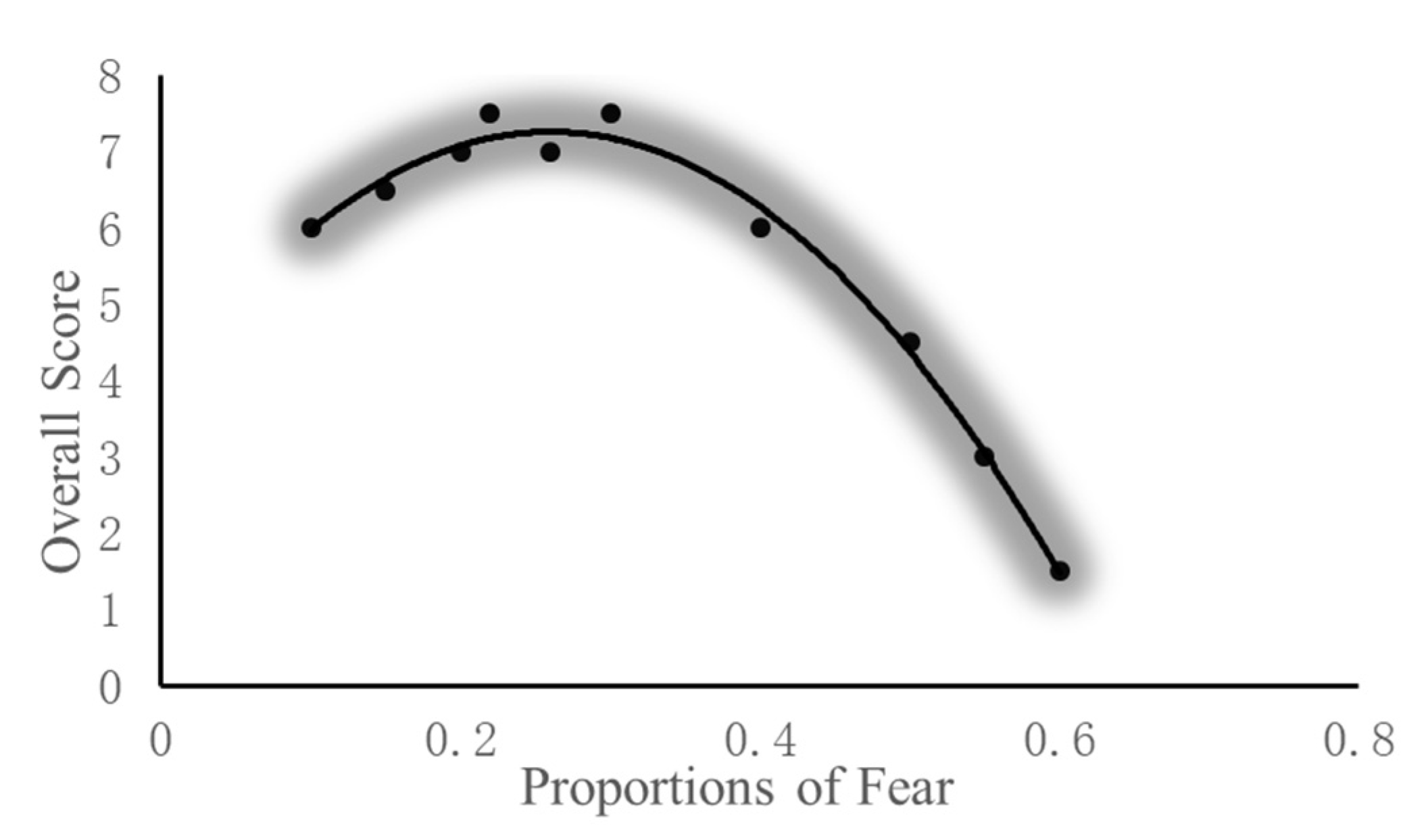

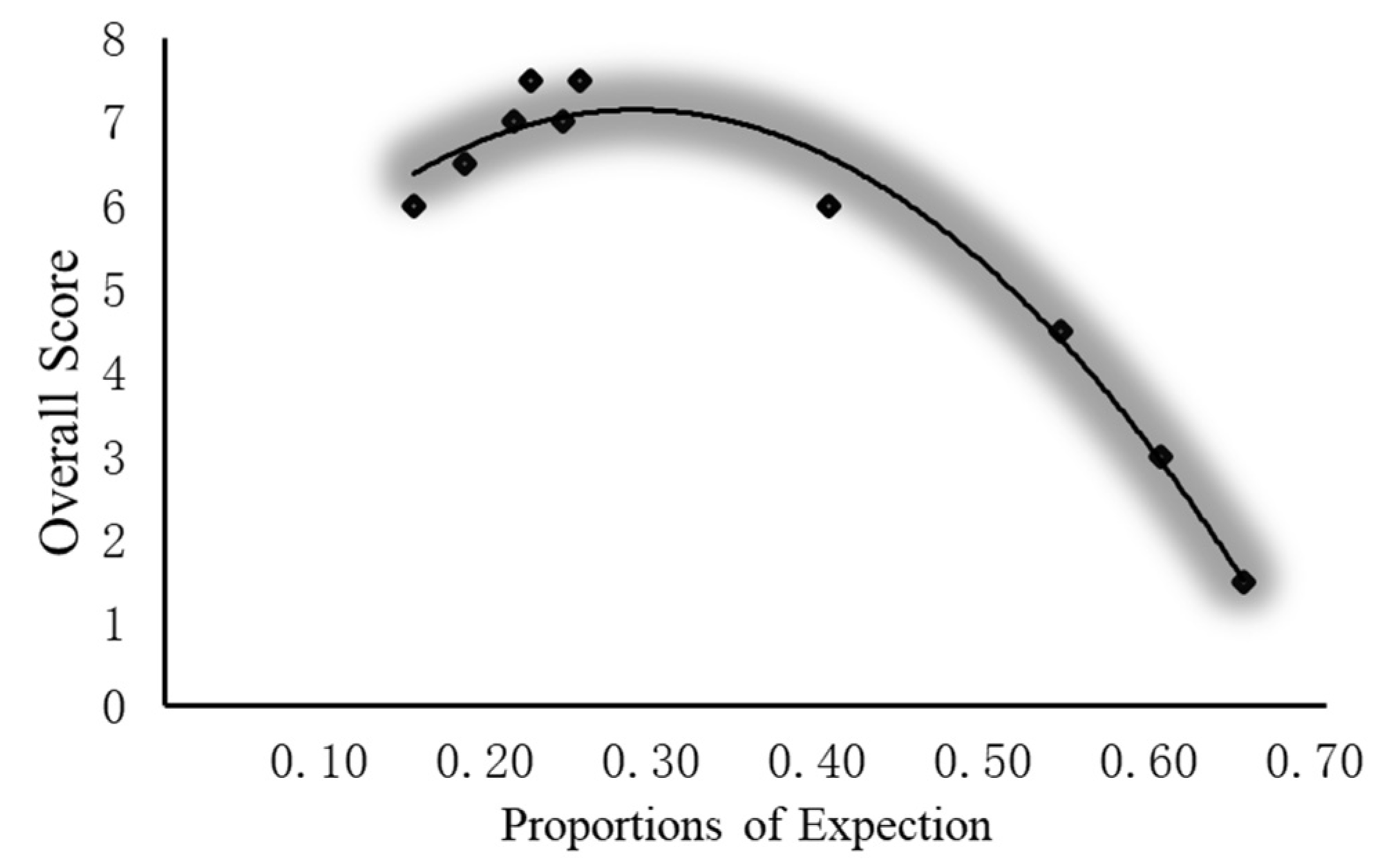

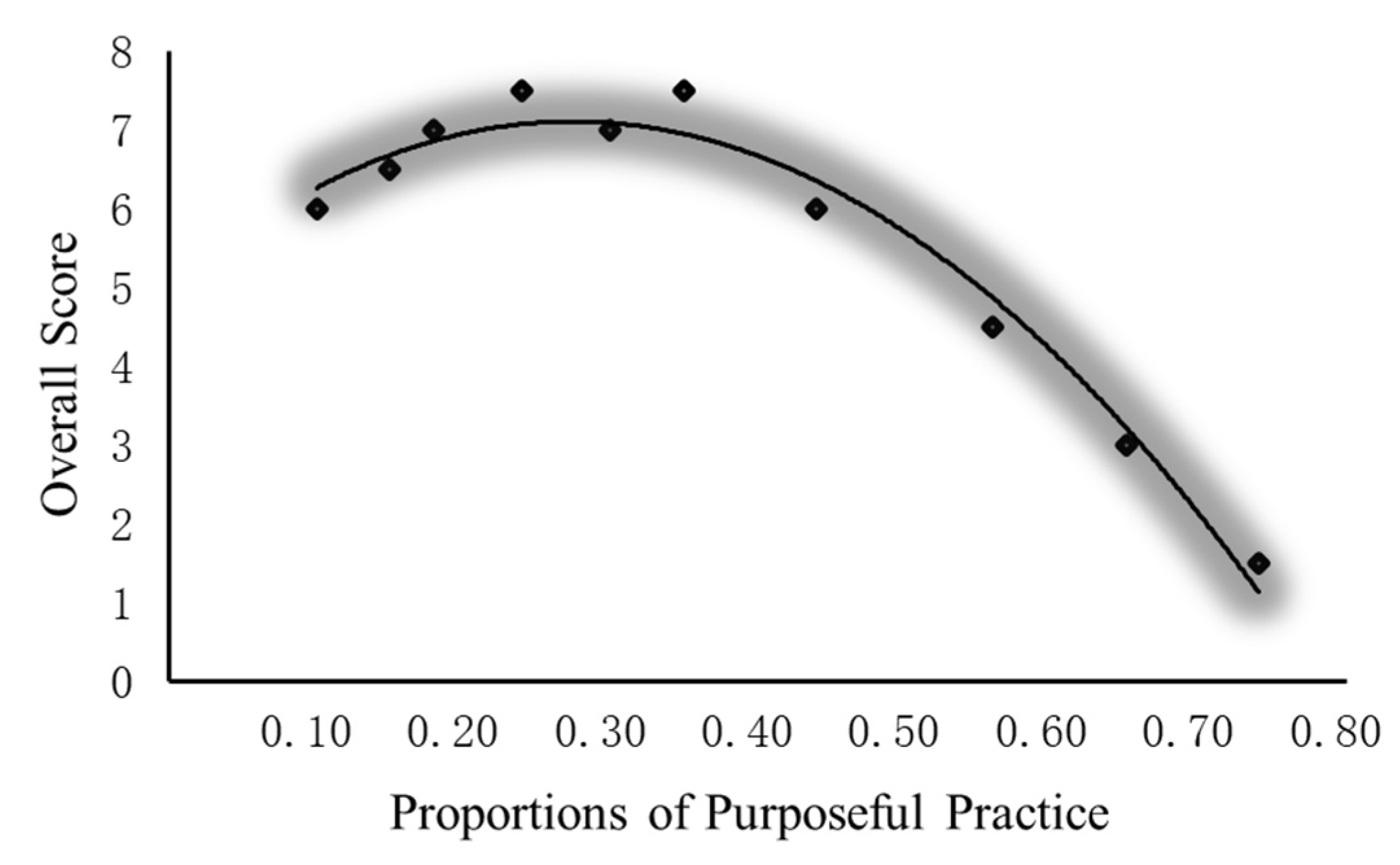

. Due to the continuation of the mathematical methods and logic in Chapter 4, the fitting process will not be elaborated here. The scatter plot of individual factors on learning scores can be obtained as follows (see

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

According to the fitting results of the three independent emotional variables on the emotional score

, Constructing the 2nd Lyapunov function:

. It can be concluded that

This indicates that the model has a high degree of fit, and

-tests were conducted on each variable, with

-values all less than 0.05, indicating a significant impact. Finally, the fitted emotional quantification model is

6. Design of a Comprehensive Score Quantification Model System

The comprehensive score is obtained by fitting the emotional score and academic performance score . is multiple nonlinear regression model which is still includes three emotional parameters: feel the proportions of fear ; feel the proportions of expectation , feel the proportions of purposeful pratice ; errors caused by other reasons .

We conduct nonlinear regression analysis by combining independent and dependent variables, with the variable set as a quadratic equation. The final nonlinear regression model is preliminarily determined as:

By using nonlinear regression mathematical tools to fit the data obtained from the questionnaire survey with actual music school grades, the final nonlinear model is obtained as follows:

Similarly, the scatter plot of a single factor's impact on the comprehensive score nonlinear model

can be obtained as follows (see

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15).

7. Discussion

This study constructs quantitative model system for emotional factors and actual learning effectiveness factors in music learning system, and then obtains an overall quantitative model through data fusion technology. This research method has been rarely used in previous studies, which is also a novelty and originality of this study. Its characteristic lies in explaining from a data perspective how certain emotional factors affect the actual effectiveness of music learning system.

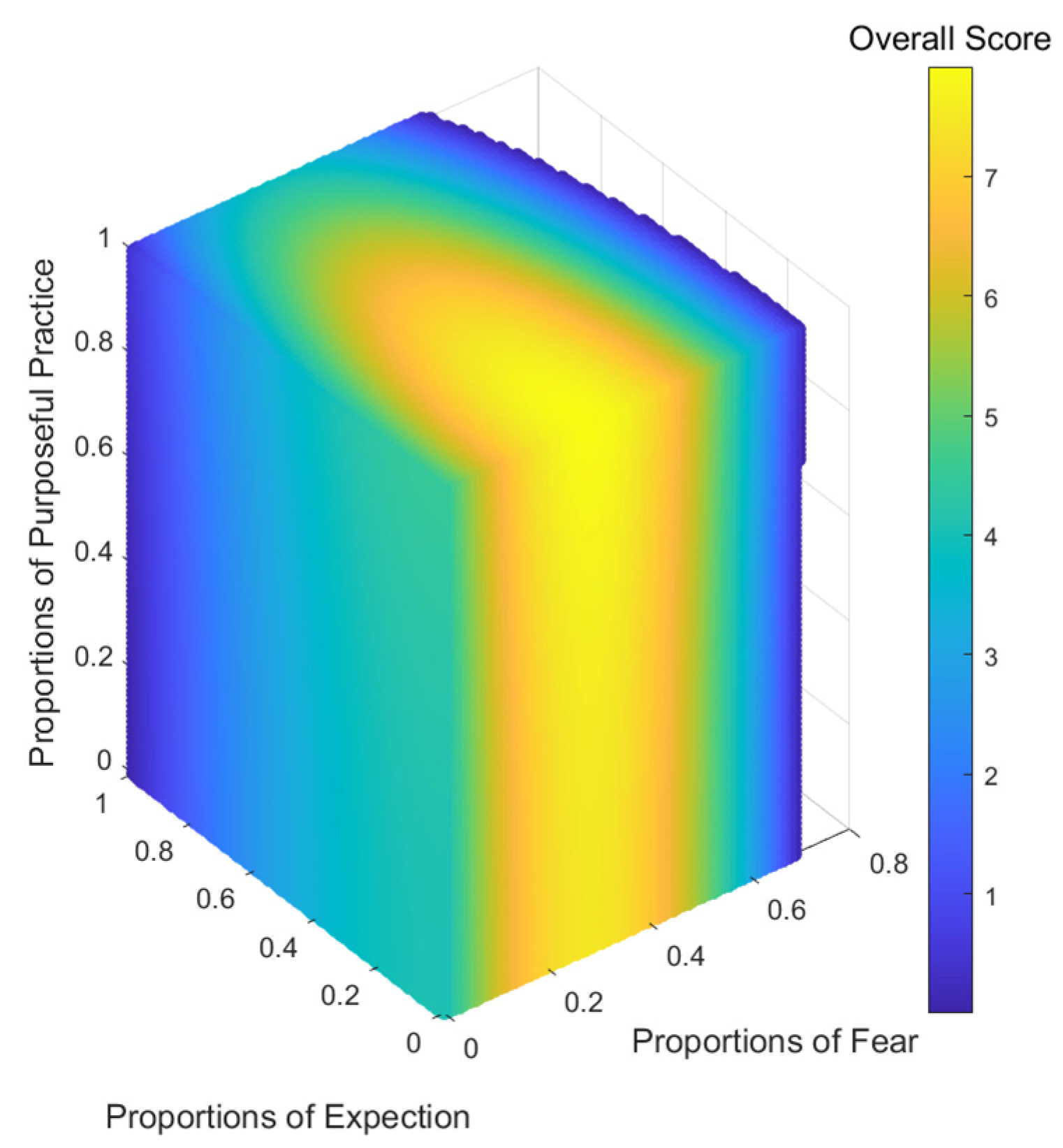

Based on the model simulation results of the overall fusion system, determine the comprehensive impact of three factors on the comprehensive score model system. For the consideration of data reliability, this study used data model system simulation techniques to obtain the different effects of multiple factors in different intervals on the comprehensive sustainable music learning score, and quantitatively analyzed them.

The quantitative model of the data presents a distribution chart of interval scores between different scores range, as shown in the following

Figure 16,

Figure 17 and

Figure 18. It presents the quantitative impact of three main emotional factors on music learning system.

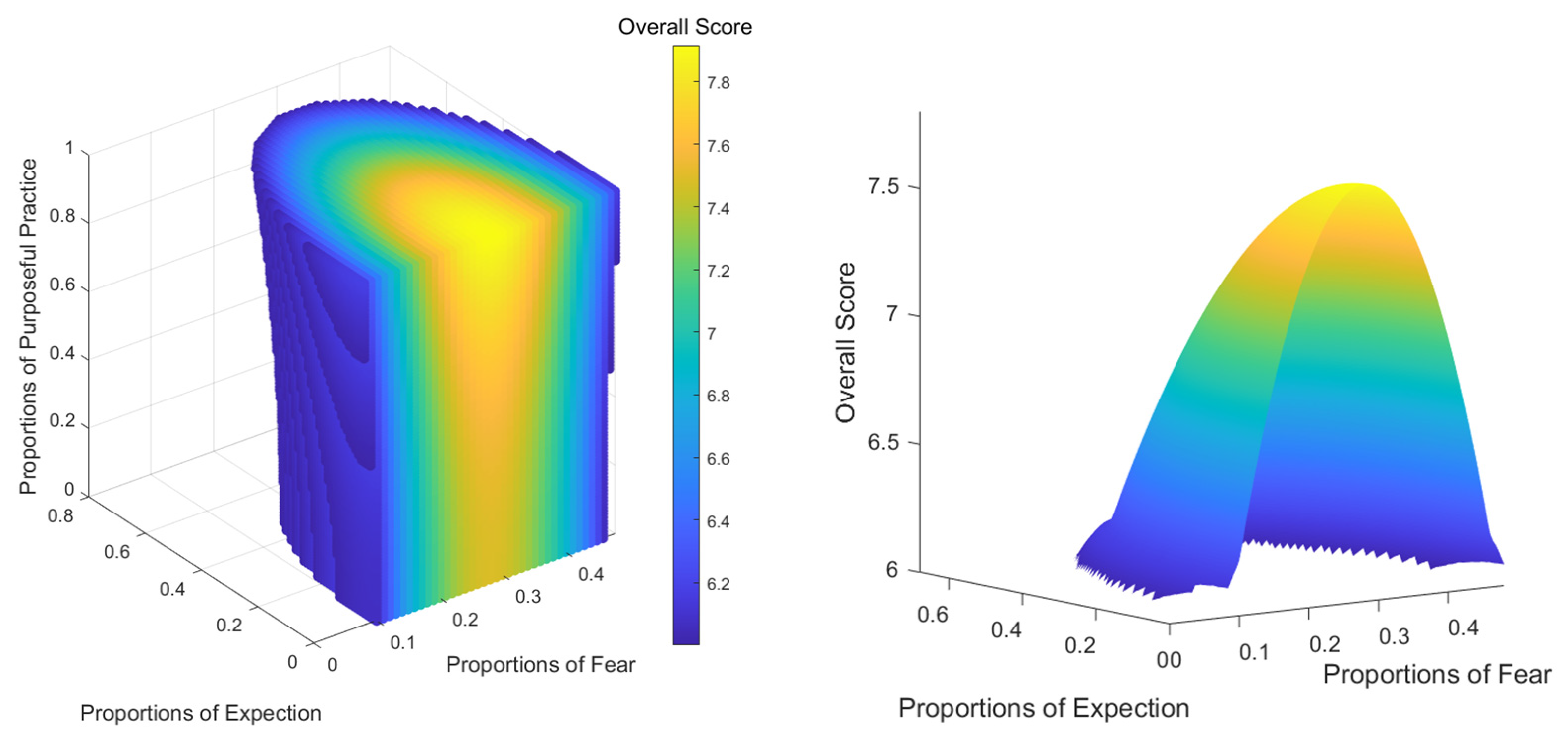

Figure 16 shows the different quantitative effects of three emotional factors within a larger range on the overall score of integrated music learning system. It can be intuitively observed that the three emotional factors have different degrees of impact on learning, while the factor of " purposeful practice " has no significant impact on the overall score of music learning system, while the other two have some significant differences in the impact on individual music learning. Based on the above analysis, it is necessary for this study to narrow the range of score values and focus on the subtle effects of emotional factors “fear” and “expectation” on music learning system. It separated two factors that have a significant impact on sustainable music learning system and quantitatively analyzed their impact on music learners in a relatively small area (see

Figure 17 and

Figure 18).

It considers a comprehensive score greater than 6 as qualified [

7,

39,

48]. Analyzing the research results of previous research, this study quantitatively assigns values to ideal music learning system, which helps to extract relevant ideal innovations from the data results. Based on the simulation results of model system, we can determine the comprehensive impact of emotional factors on the overall score. Furthermore, we can analyze the proportion of the three emotions within the optimal range of qualified scores. The model graph shows that expectations and fears have a significant impact on overall scores. When the influence range of these two factors is kept between 0.1 and 0.4, the overall comprehensive score is higher, which can ensure both emotional stability and continuous improvement of one's own music level. As a source of emotional factor scores, this study obtained them through a questionnaire survey, and this method is particularly reasonable and universal, which has been confirmed by various previous studies. The concept of psychological needs was used as a theoretical framework for the present investigation. A psychological needs perspective is a concise way to unify the findings and conclusions of music learning experience research, as well as to explain the findings of the current study. This study effectively integrated emotional survey results with actual learning outcomes, and obtained a series of factors that affect sustainable music learning through weighting methods. Furthermore, the interrelationships between different factors and the weight impact values on the overall fusion score were obtained (see

Figure 19).

Fear, expectation and misunderstanding of the practice are the main elements affects learning system. Musicians probably have plenty of chances to feel fear, such as performing on the stage, playing for teachers, facing their weaknesses, etc. However, if they can dig into it and find out the real reasons that causes that fearful feeling, they may find methods to overcome it. Everyone deserves to experience joy in a sustainable learning process and to play freely. As students, adequate and solid preparation is the most important part of overcoming the fear. During our preparation, locating the problems is a top priority. Setting a non-judgmental mind is a precondition to finding out where we truly are in the learning process. Once we have a goal, targeted, focused practice can help us enjoy the problem-solving game, instead of suffering from feeling upset and frustrated in mindless practice sessions.

The above data quantifies the subtle relationship between emotional factors and actual music learning system, and this study models system and analyzes them in the form of data, further obtaining the impact results. The data and analysis above show that creating a supportive and non-judgmental learning environment is critical to alleviating this fear and fostering a more positive music learning experience. As teachers, modeling the physical and mental processes help students to understand the instructions more deeply. Increasing students’ self-awareness enables them to transfer the knowledge into skills. Creating a safe atmosphere for students to show their weaknesses and expose their mistakes without feeling fearful and embarrassed is of utmost importance. Also, building a trusting relationship has a positive effect on communication between teachers and students. Teachers ‘reliability depends on whether their words and actions are consistent. In sustainable piano teaching, when teachers’ own behaviors do not match the instructions they give, they can lose the students’ trust easily. Students will no longer believe the instruction from teachers that do not follow the instruction themselves. The purpose of all these strategies is to help students experience fearless playing and moments of true joy in learning system process.

8. Conclusions

In the field of music learning research, the diversified processing mode system of data ultimately serves to support educational theories. Furthermore, it provides necessary practical support and solid theoretical basis for proposing new sustainable educational system theories. This research contributes valuable insights into the nuanced dynamics shaping music learning system landscape for college students in China, paving the way for targeted interventions and improved pedagogical practices and further provides opportunities for cross-cultural comparisons. The findings underscore the importance of addressing psychological factors influencing music learning experiences. Strategies to reduce the fear of making mistakes,judgment from instructors, manage expectations, and promote focused, can be incorporated into music learning system. Additionally, implementing mentorship programs, providing emotional support, and fostering a culture of collaboration rather than competition could contribute to a more inclusive and positive learning environment. By addressing these factors, educators and institutions can enhance the overall well-being and satisfaction of their students in the pursuit of musical excellence.

This study holds significant value in shedding light on the intricate interplay of psychological factors in the realm of music learning experiences, particularly among college students in China. The insights gained from this research provide a nuanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities in music learning system, paving the way for more effective and student-centric teaching methods. The identification of fear, expectations, and misconceptions as central elements influencing learning experiences offers a foundation for targeted interventions and improvements in educational practices. The practical applications of this study are manifold. Educators and institutions can leverage the findings to tailor their teaching approaches, incorporating strategies that specifically address the psychological aspects identified. For instance, designing fear-reducing initiatives, providing mentorship programs, and fostering a collaborative culture can significantly contribute to creating a positive and inclusive learning environment. Moreover, the emphasis on purposeful practice and the management of expectations offers actionable insights for refining curriculum design and teaching methodologies. As a steppingstone for future research, this study opens avenues for exploring additional psychological factors and their impacts on music learning. Subsequent investigations could delve deeper into the efficacy of specific interventions, potentially leading to the development of evidence-based frameworks for optimizing the sustainable music learning experience. Comparative studies across different cultural contexts or educational settings could further enrich our understanding of the universality or specificity of these psychological factors.

In conclusion, the value of this study lies not only in its immediate application to enhance sustainable music system but also in its potential to inspire and guide future research endeavors. The quest to unravel the complexities of psychological influences in music learning system is an ongoing journey, and this study provides a solid foundation for further exploration and refinement of educational practices in the evolving landscape of music learning system.

Author Contributions

Author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received funding from Hangzhou Normal University Talent Introduction Initiation Fund, No. 4195C50221204106.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the survey conducted in the public education environment and not involving human experiments.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this research are included in this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Simmons, Amy L., and Robert A. Duke. 2006. Effects of Sleep on Performance of a Keyboard Melody. Journal of Research in Music Education 54: 257–69. [CrossRef]

- Colzato, Lorenza S., Ayca Ozturk, and Bernhard Hommel. 2012. Meditate to Create: The Impact of Focused-Attention and Open-Monitoring Training on Convergent and Divergent Thinking. Frontiers in Psychology 3. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, H. and Damasio, A. R. 2003. Role of the amygdala in decision-making. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 985: 356-369. [CrossRef]

- Duke, Robert A. 2015. Intelligent Music Teaching: Essays on the Core Principles of Effective Instruction. Austin, TX: Learning and Behavior Resources.

- Allen, P. A., Kaut, K. P., Baena, E., Lien, M.-C. and Ruthruff, E. 2011. Individual differences in positive affect moderate age-related declines in episodic long-term memory. Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 23: 768-779nitive Psychology. 23: 768-779. [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition and Personality, 9(3), 185-211.S, Lorenza, Hommel, and Bernhard. 2012. Meditate to Create: The Impact of Focused-Attention and Open-Monitoring Training on Convergent and Divergent Thinking. Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00116/full.

- Roediger, H. L., & Pyc, M. A. 2012. Inexpensive techniques to improve education: Applying cognitive psychology to enhance educational practice. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, 1(4), 242-248. [CrossRef]

- Todorov, A. 2008. Evaluating faces on trustworthiness: An extension of systems for recognition of emotions signaling approach/avoidance behaviors. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1124: 208 – 224. [CrossRef]

- Panksepp, J. 1995. The emotional sources of "chills" induced by music. Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 13(2), 171-207. [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M. M., Greenwald, M. K., Petry, M. C. and Lang, P. J. 1992. Remembering pictures: Pleasure and arousal in memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition18: 379 – 390. [CrossRef]

- Doidge, N. 2007. The Brain That Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science. Viking.

- Evans, K. C., Wright, C. I., Wedig, M. M., Gold, A. L., Pollack, M. H. and Rauch, S. L. 2008. A functional MRI study of amygdala responses to angry schematic faces in social anxiety disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 25: 496 – 505. [CrossRef]

- Amaral, D. G., Pric, J. L., Pitkanen, A. and Carmichael, S. T. 1992. The amygdala: Neurobiological aspects of emotion, memory, and mental dysfunction, New York, NY: Wiley-Liss.

- Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. T., & Tesch-Römer, C. 1993. The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100(3), 363–406. [CrossRef]

- Levitin, D. J. 2006. This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession. Plume.

- Timpe, J. C., Rowe, K. C., Matsui, J., Magnotta, V. A. and Denburg, N. L. 2011. White matter intensity, as measured by diffusion tensor imaging, distinguishes between impaired and unimpaired older adult decision makers. Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 23: 760 – 767. [CrossRef]

- Chokrovert, Sudhansu. 2017. Sleep Disorders Medicine: Basic Science, Technical Considerations and Clinical Aspects. New York, NY: Springer New York.

- Jäncke, L. 2008. Music, memory and emotion. Journal of Biology, 7(6), 21.

- Walker, Matthew P., and Robert Stickgold. 2005. Its Practice, with Sleep, That Makes Perfect: Implications of Sleep-Dependent Learning and Plasticity for Skill Performance. Clinics in Sports Medicine 24: 301–317. [CrossRef]

- Bishop, S. J. 2009. Trait anxiety and impoverished prefrontal control of attention. Nature Neuroscience, 12: 92 – 98. [CrossRef]

- Coyle, Daniel. 2009. The Talent Code: Greatness Isn't Born. It's Grown. Here's How. New York: Bantam Books.

- Dolcos, Florin, Alexandru D. Iordan, and Sanda Dolcos. 2011. Neural Correlates of Emotion–Cognition Interactions: A Review of Evidence from Brain Imaging Investigations. Journal of Cognitive Psychology 23: 669–94. [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. 1990. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row.

- Moore, Adam, and Peter Malinowski. 2009. Meditation, Mindfulness and Cognitive Flexibility. Consciousness and Cognition 18: 176–86. [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice-Hall.

- Bishop, S. J., Duncan, J. and Lawrence, A. D. 2004. State anxiety modulation of the amygdala response to unattended threat-related stimuli. Journal of Neuroscience, 24: 10364 – 10368. [CrossRef]

- Walker, David L., and Michael Davis. 2002. The Role of Amygdala Glutamate Receptors in Fear Learning, Fear-Potentiated Startle, and Extinction. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior 71: 379–92. [CrossRef]

- Brooks, David. 2019 Students Learn From People They Love. The New York Times.

- Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., & Wegner, D. M. 2011. Psychology (2nd ed.). Worth Publishers.

- Hanson, Rick. 2013. Be Benevolent: Liking Feels Good, It Encourages Us to Approach and Engage the World. Psychology Today, https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/your-wise-brain/201309/be-benevolent.

- Amygdala. 2020. ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/terms/amygdala.htm.

- Gallwey, W. Timothy. 1974. The Inner Game of Tennis. New York: Random House.

- Pink, D. H. 2009. Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. Riverhead Books.

- James Clear. 2020. The Scientific Argument for Mastering One Thing at a Time. James Clear. https://jamesclear.com/master-one-thing.

- Werner, Kenny. 1996. Effortless Mastery. New Albany: Jamey Aebersold Jazz.

- Clear, James. 2016. The Scientific Argument for Mastering One Thing at a Time. Lifehacker, https://lifehacker.com/the-scientific-argument-for-mastering-one-thing-at-a-ti-1783872506.

- Ewbank, M. P., Lawrence, A. D., Passamonti, L., Keane, J., Peers, P. V. and Calder, A. J. 2009. Anxiety predicts a differential neural response to attended and unattended facial signals of anger and fear. Neuroimage, 44: 1144 – 1151. [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R. J., & Salimpoor, V. N. 2013. From perception to pleasure: Music and its neural substrates. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(Supplement 2), 10430-10437. [CrossRef]

- Eugene, F., Levesque, J., Mensour, B., Leroux, J. M., Beaudoin, G. Bourgouin, P. 2003. The impact of individual differences on the neural circuitry underlying sadness. Neuroimage, 19: 354 – 364. [CrossRef]

- Talmi, D., Schimmac, U., Paterson, T. and Moscovitch, M. 2007. The role of attention and relatedness in emotionally enhanced memory. Emotion, 7: 89 – 102. [CrossRef]

- Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H. and Anderson, S. W. 1994. Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition, 50: 7-15. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Richard J., and Antoine Lutz. 2008. Buddhas Brain: Neuroplasticity and Meditation [In the Spotlight]. IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 25: 176–74. [CrossRef]

- Harvey, Kristin Emilia. 2013. Tracking the Longitudinal Effects of Student-Teacher Trust on Mathematics SelfEfficacy for High School Students.

- Tulving, E. 1985. Memory and consciousness. Canadian Psychology, 26: 1 – 12. [CrossRef]

- Dingman, Marc. 2014. Know Your Brain: Amygdala. Neuroscientifically Challenged. https://www.neuroscientificallychallenged.

- Tessitore, A., Hariri, A. R., Fera, F., Smith, W. G., Das, S. Weinberger, D. R. 2005. Functional changes in the activity of brain regions underlying emotion processing in the elderly. Psychiatry Research, 139: 9 – 18. [CrossRef]

- Hannon, E. E., & Trainor, L. J. 2007. Music acquisition: Effects of enculturation and formal training on development. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(11), 466-472. [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, Anders, and Robert Pool. 2017. Peak: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. Boston: Eamon Dolan.

- Dalton, Amy N., and Stephen A. Spiller. 2012. Too Much of a Good Thing: The Benefits of Implementation Intentions Depend on the Number of Goals. Journal of Consumer Research 39: 600–614. [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S. 2014. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 15(3), 170-180. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lin, Y. Global adaptive stabilisation of feedforward systems by smooth output feedback. IET Control. Theory Appl. 2012, 6, 2134–2141. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, Q.; Baron, L.; Boukas, E.K. Feedback stabilization for high order feedforward nonlinear time-delay systems. Automatica 2011, 47, 962–967. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Na, J.; Ren, X. RISE-Based Asymptotic Prescribed Performance Tracking Control of Nonlinear Servo Mechanisms. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2018, 48, 2359–2370. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Yu, H.; Yu, J.; Na, J.; Ren, X. Neural-Network-Based Adaptive Funnel Control for Servo Mechanisms with Unknown Dead-Zone. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 1383–1394. [CrossRef]

- Na, J.; Wang, S.; Liu, Y.J.; Huang, Y.; Ren, X. Finite-Time Convergence Adaptive Neural Network Control for Nonlinear Servo Systems. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2020, 50, 2568–2579. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, K.D. An adaptive controller for uncertain nonlinear systems with multiple time delays. Automatica 2020, 117, 108976. [CrossRef]

- Pai, M. RBF-Based Discrete Sliding Mode Control for Robust Tracking of Uncertain Time-Delay Systems with Input Nonlinearity. Complexity 2015, 21, 194–201. [CrossRef]

- Krishnamurthy, P.; Khorrami, F. Feedforward systems with ISS appended dynamics: Adaptive output-feedback stabilization and disturbance attenuation. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2008, 53, 405–412. [CrossRef]

- Koo, M.S.; Choi, H.L.; Lim, J.T. Global regulation of a class of uncertain nonlinear systems by switching adaptive controller. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2010, 55, 2822–2827. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ju, H.P.; Hua, C.; Liu, G. Distributed adaptive output feedback containment control for time-delay nonlinear multiagent systems. Automatica 2021, 127, 109545. [CrossRef]

- Bringeldal, B.; Storkaas, E.; Dalsmo, M.; Aarset, M.; Marius, H. Recent developments in control and monitoring of remote subsea fields. In Proceedings of the SPE Intelligent Energy Conference and Exhibition, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 23–25 March 2010; p. 128657.

- Zhang, X.; Baron, L.; Liu, Q.; Boukas, E.K. Design of stabilizing controllers with a dynamic gain for feedforward nonlinear time-delay systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2011, 56, 692–697. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Zhang, C. Global asymptotic stabilization of feedforward nonlinear systems with a delay in the input. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2006, 37, 141–148. [CrossRef]

- Jo, H.W.; Choi, H.L.; Lim, J.T. Observer based output feedback regulation of a class of feedforward nonlinear systems with uncertain input and state delays using adaptive gain. Syst. Control. Lett. 2014, 71, 44–53. [CrossRef]

- Shubo, W.; Xuemei, R.; Jing, N.; Tianyi, Z. Extended-State-Observer-Based Funnel Control for Nonlinear Servomechanisms with Prescribed Tracking Performance. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2017, 14, 98–108. [CrossRef]

- Manhas, N.; Anbazhagan, N. A mathematical model of intricate calcium dynamics and modulation of calcium signalling by mitochondria in pancreatic acinar cells. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2021, 145, 110741. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Distribution of Ratings.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Ratings.

Figure 2.

Number of people in the crowd.

Figure 2.

Number of people in the crowd.

Figure 3.

The proportion of each reason in the total.

Figure 3.

The proportion of each reason in the total.

Figure 4.

Fear in the proportion of the population.

Figure 4.

Fear in the proportion of the population.

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Fear).

Figure 5.

Scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Fear).

Figure 6.

Expectation in the proportion of the population.

Figure 6.

Expectation in the proportion of the population.

Figure 7.

Scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Expectation).

Figure 7.

Scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Expectation).

Figure 8.

Purposeful Practice in the proportion of the population.

Figure 8.

Purposeful Practice in the proportion of the population.

Figure 9.

Scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Purposeful Practice).

Figure 9.

Scatter plot of the impact of a single factor (Purposeful Practice).

Figure 10.

Scatter plot of “Fear” factor on learning scores.

Figure 10.

Scatter plot of “Fear” factor on learning scores.

Figure 11.

Scatter plot of “Expection” factor on learning scores.

Figure 11.

Scatter plot of “Expection” factor on learning scores.

Figure 12.

Scatter plot of “Purposeful Practice” factor on learning scores.

Figure 12.

Scatter plot of “Purposeful Practice” factor on learning scores.

Figure 13.

Scatter plot of a single “Fear” factor's impact on comprehensive score.

Figure 13.

Scatter plot of a single “Fear” factor's impact on comprehensive score.

Figure 14.

Scatter plot of “Expection” factor's impact on comprehensive score.

Figure 14.

Scatter plot of “Expection” factor's impact on comprehensive score.

Figure 15.

Scatter plot of “Purpose Practice” factor's impact on comprehensive score.

Figure 15.

Scatter plot of “Purpose Practice” factor's impact on comprehensive score.

Figure 16.

Results with an overall score between 0 and 8.

Figure 16.

Results with an overall score between 0 and 8.

Figure 17.

Results with an overall score between 0 and 6(The right figure represents the effect of separating two factors).

Figure 17.

Results with an overall score between 0 and 6(The right figure represents the effect of separating two factors).

Figure 18.

Results with an overall score between 6 and 8(The right figure represents the effect of separating two factors).

Figure 18.

Results with an overall score between 6 and 8(The right figure represents the effect of separating two factors).

Figure 19.

Diagram of quantitative models that affect music learning system.

Figure 19.

Diagram of quantitative models that affect music learning system.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).