Core tip

Mycotic aneurysms are usually caused by infections in the vital organs. Although typically solitary, we present a case of peripheral mycotic aneurysm associated with multiple aneurysms in the lower extremities. The patient eventually developed infective endocarditis and contained abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture, which were managed successfully.

1. Introduction

A mycotic aneurysm, also referred to as an infected aneurysm, is a rare but fatal disease when it ruptures. Since mycotic aneurysms are usually found only at autopsy in the absence of symptoms, their true incidence is often underestimated and difficult to determine [

1]. In a previous study that analyzed autopsy results, mycotic aortic aneurysms constituted 3.3% of all aneurysms [

2]. Even when a mycotic aneurysm is diagnosed and treated, mortality is reported in approximately 31% of cases; when it ruptures, mortality is reported in approximately 75% of cases [

3]. The cause of mycotic aneurysms is unclear, and several theories have attempted to explain it through the analysis of a large number of cases [

4].

We report a unique case of a peripheral mycotic aneurysm discovered incidentally and associated with multiple mycotic aneurysms that eventually developed infective endocarditis and a contained rupture of the mycotic aneurysm in the abdominal aorta.

2. Case Presentation

A 63-year-old-male presented to the emergency room with a fever of unknown origin that had not responded to antibiotic treatment for two weeks. In the nursing hospital, pneumonia and urinary tract infections, which commonly occur in hospitalized patients, were excluded during the examination, and the patient was diagnosed as having an unknown fever. A combination of 4.5 g of Piperaciilin and tazobactam was administered intravenously every 6 hours as a broad-spectrum antibiotic. The patient had been bedridden due to a traumatic subdural hemorrhage and a left corona radiata infarction. The patient also suffered a myocardial infarction that required aspirin administration. In the emergency room, the patient had no pain or tenderness in the body, and the lung sound was clear. The patient presented with mild leukocytosis, elevated C-reactive protein levels, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Rheumatoid diseases were excluded because of low complement levels, low immune antibody levels, and the absence of any related symptoms when examined by a rheumatologist. Five days after admission to the infection department,

Candida albicans was cultured from the blood, and fluconazole was administered. Despite the administration of antifungal agents and antibiotics, a spiking fever of more than 40°C, occurring 2–3 times a day, persisted. Echocardiography was performed to determine the cause of the fever and to rule out infective endocarditis. A cardiologist performed transthoracic echocardiography; however, no vegetation was observed. The following day, transesophageal echocardiography was performed; however, vegetation was still not observed. After receiving conservative treatment for two weeks, the patient suddenly complained of pain in the right arm and localized swelling on the antecubital fossa during the third week of hospitalization.

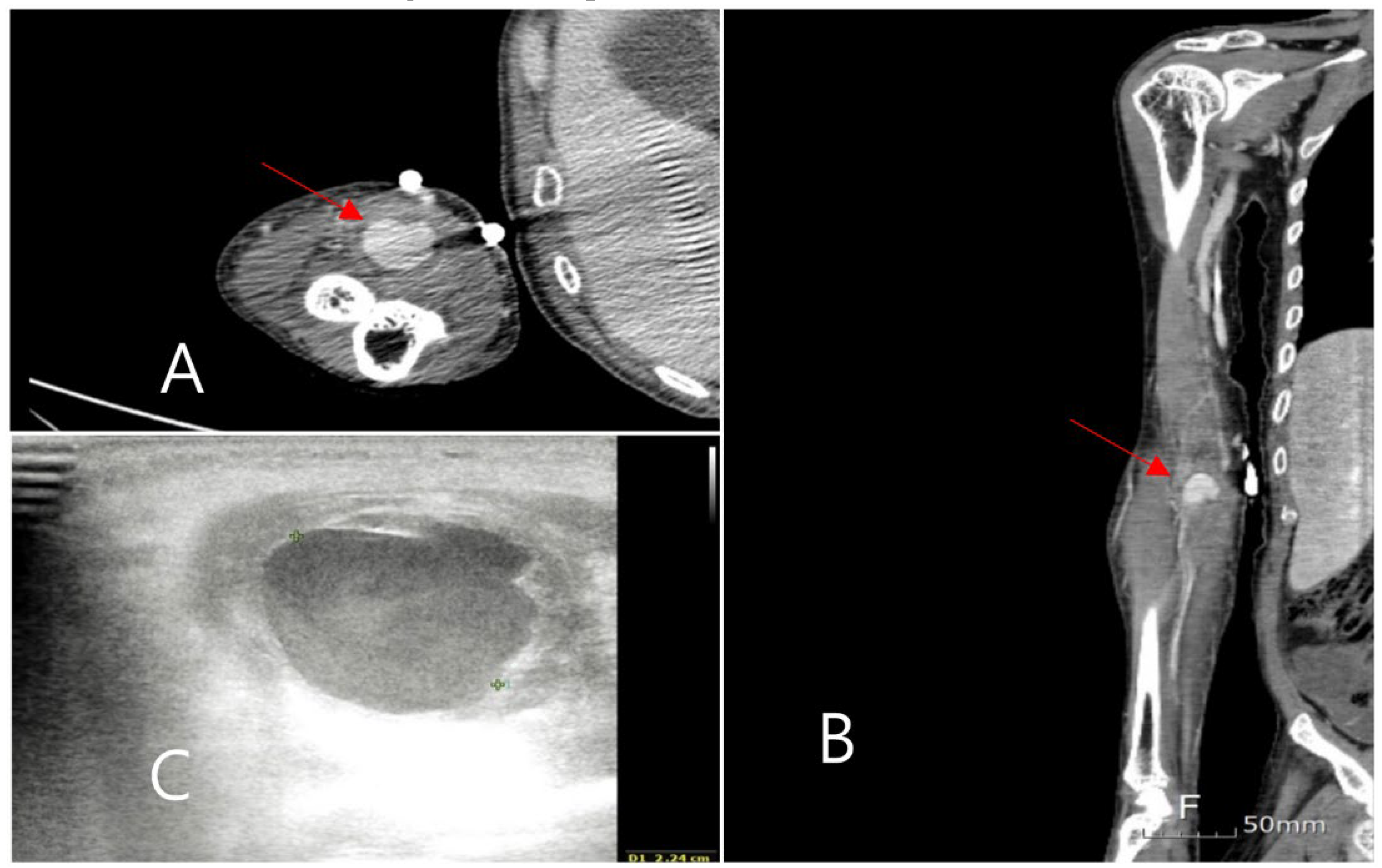

The pain was not accompanied by hyperemia or skin redness, but a tender, rigid, fixed, and palpable pulsatile mass was observed. Computed tomography (CT) of the upper limb was performed, revealing an aneurysm of the right brachial artery (Figure 1). Vascular ultrasonography revealed that the aneurysm contained a thrombus at the brachial bifurcation. Its maximum diameter was approximately 2.3 cm. The septic focus was determined to be a mycotic aneurysm of the brachial artery, and emergency surgery was performed. The mycotic aneurysm was completely removed, and bypass surgery was performed from the brachial artery to the radial and ulnar arteries using a bovine patch.

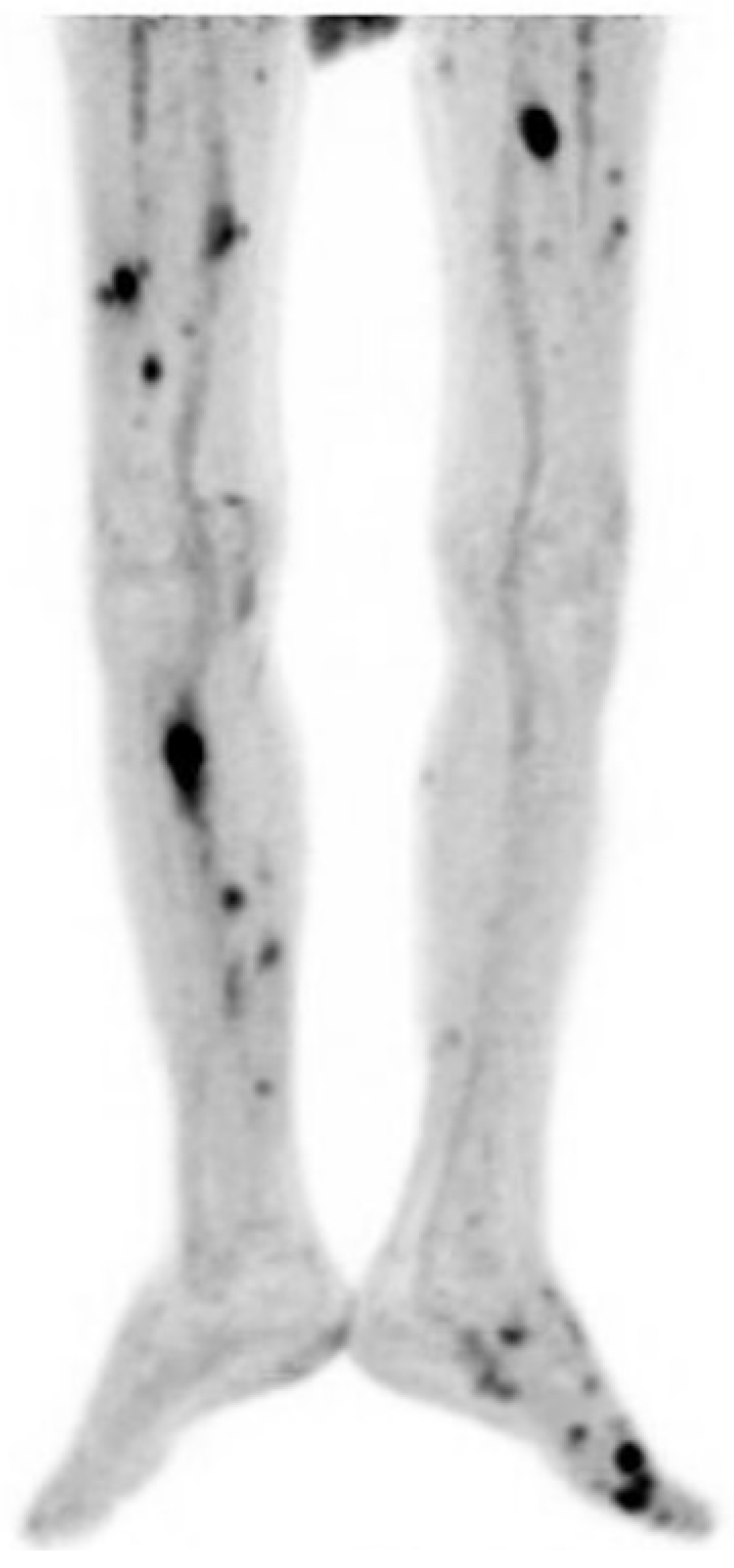

Although the symptoms in the arm disappeared, the spiking fever persisted. To evaluate the other origins of fever, a positron emission tomography (PET) scan of the entire body was performed (

Figure 2). It showed high uptake in multiple aneurysms in the abdomen and both lower extremities with normal aorta. A lower extremity CT scan was performed, wherein several aneurysms occluded by a thrombus were observed. A multidisciplinary meeting was held to determine the treatment strategy. Echocardiography was repeatedly performed by another cardiologist. The vegetation in the heart, which was not seen in the previous examination, was observed.

3. Final Diagnosis

The patient received a primary diagnosis of peripheral mycotic aneurysm followed by one of infected endocarditis before receiving a final diagnosis: multiple mycotic aneurysms of the brachial artery and lower extremities with associated infective endocarditis.

4. Treatment

The patient declined to undergo additional surgical treatment for personal reasons, the systemic condition and fever improved with continuous administration of antibiotics and antifungal agents until discharge to a nursing home.

5. Outcome and Follow-up

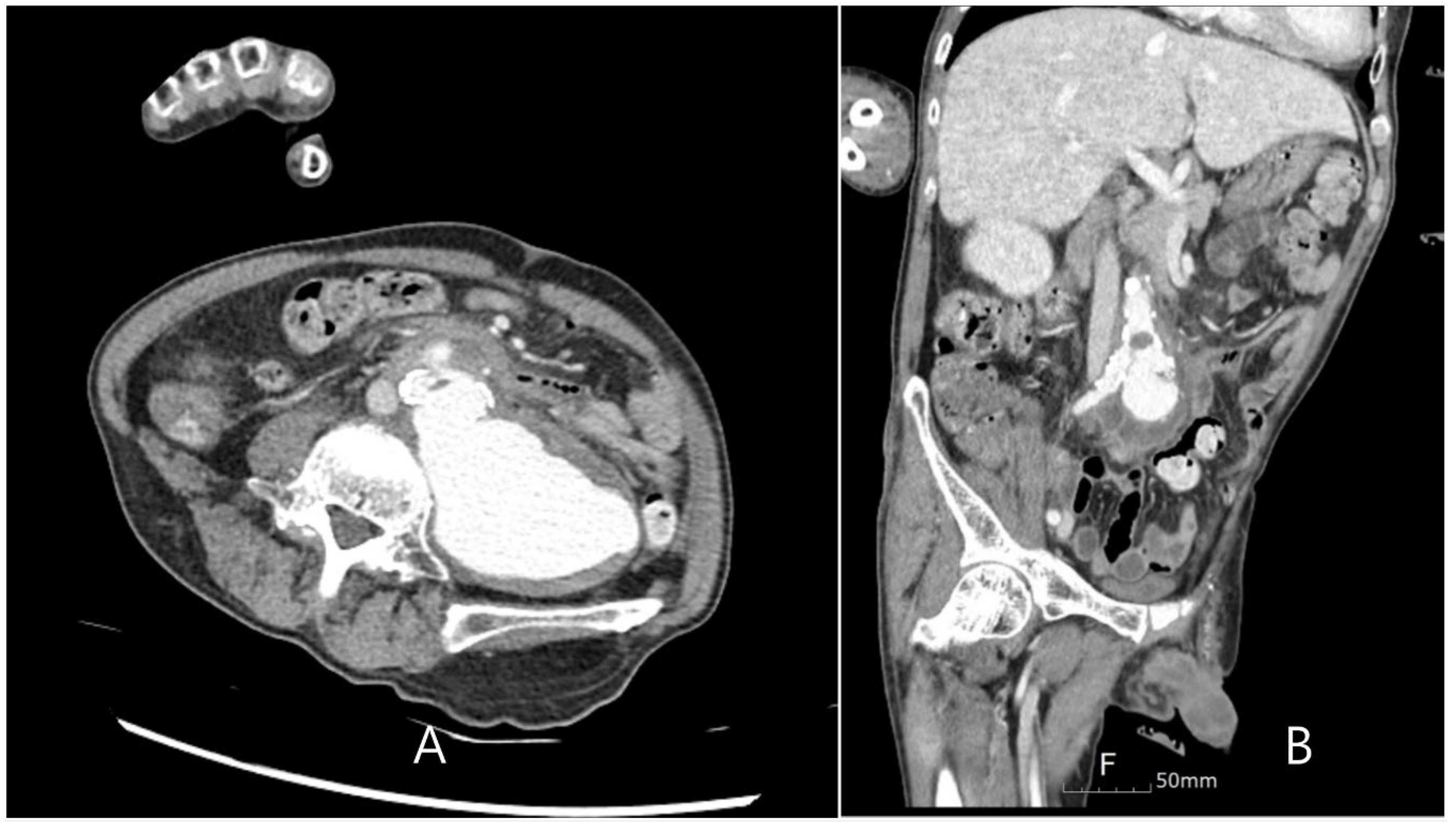

Five months later, the patient was readmitted to the emergency room for a recurrence of a fever of unknown origin. Leukocytosis was observed, but other laboratory examinations revealed no specific findings. To evaluate the focus of the fever, chest and abdominal CT scans were performed, as shown in

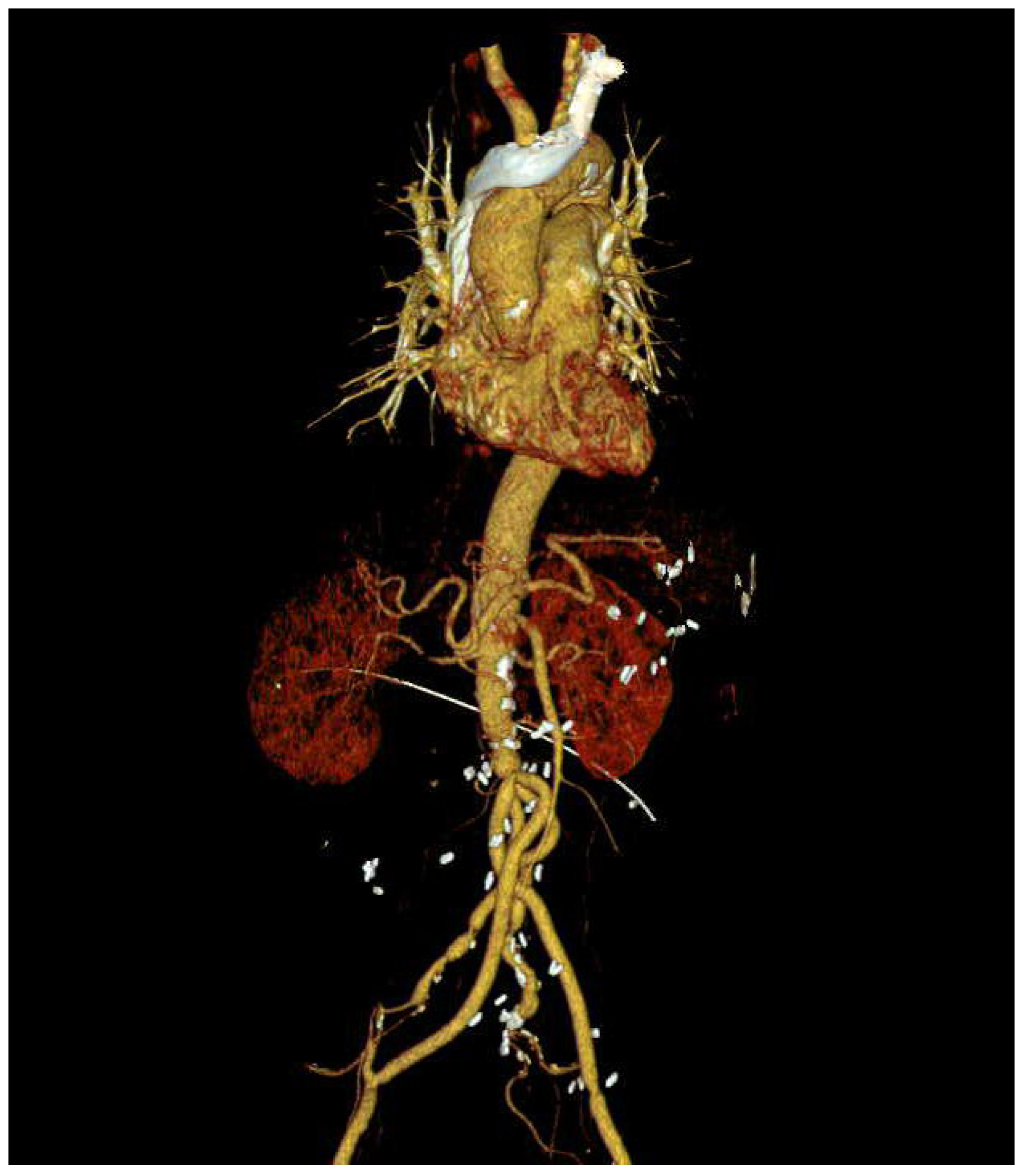

Figure 3. The findings revealed a contained rupture of the mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA). The patient underwent emergency AAA repair using an antibiotic-soaked graft. No complications were observed on the CT scan performed six months after surgery (

Figure 4), and the patient has been living without complaints of other symptoms in 1 year follow-up.

6. Discussion

Mycotic aneurysms have a high risk of rupture, leading to morbidity and mortality [

3,

5]. The most common site of mycotic aneurysm is the abdominal aorta, particularly the renal artery. The second most prevalent sites of mycotic aneurysms are the femoral and brachial arteries because they are common injection sites for drug abusers [

4]. However, our patient was bedridden, not immunocompromised, nor a drug abuser. Direct seeding from adjacent sources of infection or trauma and septic emboli from infective endocarditis can cause mycotic aneurysms of the peripheral arteries [

4].

It has previously been reported that 50–70% of blood cultures have identified the following infectious agents:

Salmonella species,

Staphylococcus aureus,

Bacteroides fragilis,

Escherichia coli, and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa [

3,

6,

7]. Contrary to other reports,

C. albicans was identified in our patient, and broad-spectrum antibiotics were administered prophylactically along with antifungal agents.

The brachial artery was an unusual location for the development of mycotic aneurysms [

6], given that the patient was not a drug abuser or an immunocompromised individual. Moreover, the patient had no history of surgery or infective endocarditis during the early stages of evaluation. According to previous literature, mycotic aneurysms have a primary infectious source, such as trauma, psoas abscess, osteomyelitis, or endocarditis [

3]. In the present case, the origin of the mycotic aneurysm was not confirmed. Adjacent sources of infection, such as lytic destruction or osteomyelitis [

8], were not identified. In addition, endocarditis was initially excluded using transthoracic and transesophageal echocardiography. We speculated that the mycotic aneurysm of the brachial artery might not have initially arisen alone but might be one of several mycotic aneurysms of the extremities. Septic emboli from several incompletely treated peripheral mycotic aneurysms were thought to have eventually induced the vegetation in the heart, which may have contributed to the delayed rupture of the mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm.

Treatment of a peripheral mycotic aneurysm involves in situ reconstruction or extra-anatomic bypass after removal of the mycotic aneurysm, along with long-term antibiotic treatment [

9]. Most reported cases were solitary mycotic aneurysms, and complete resection of the mycotic aneurysm could be achieved. However, our patient had multiple mycotic aneurysms, and his condition was not ideal for extensive surgical removal of all; therefore, long-term antibiotic treatment was administered after surgical resection of the most symptomatic aneurysm. Several peripheral aneurysms suspected of being mycotic were controlled using antibiotics; however, the patient’s abdominal aortic aneurysm seemed to have deteriorated, resulting in a contained rupture. The patient underwent AAA repair using a rifampin-soaked graft.

Several case reports have documented cerebral mycotic aneurysm caused by infective endocarditis. However, this case differs from other reports in that infective endocarditis developed while treatment for multiple peripheral mycotic aneurysm was underway, and was followed by a mycotic abdominal aortic aneurysm rupture.

7. Conclusions

According to previous reports, mycotic aneurysms are caused by a primary infectious source, such as trauma, osteomyelitis, or endocarditis. In this case, the mycotic aneurysms, which occurred in various peripheral arteries without any other causative infectious lesions, had catastrophic consequences and eventually led to the contained rupture of the abdominal aortic aneurysm. Fatal consequences might be inevitable when mycotic aneurysms are not completely treated.

Author Contributions

KCY : Data curation; investigation; writing – original draft; DHK : Script review LCJ : Supervision.

Institutional Review Board Statement

We obtained approval from the ethics committee to present the case for publication of this report and accompanying images (IRB File No. 2020-11-014-001).

Informed Consent Statement

Individual informed consent was not considered mandatory due to the retrospective nature of this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Wilson WR, Bower TC, Creager MA, Amin-Hanjani S, O’Gara PT, Lockhart PB et al. Vascular graft infections, mycotic aneurysms, and endovascular infections: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2016;134:e412–60. [CrossRef]

- Sommerville RL, Allen EV, Edwards JEJM. Bland and infected arteriosclerotic abdominal aortic aneurysms: A clinicopathologic study. Medicine (Balt) 1959;38:207–21. [CrossRef]

- Reddy DJ, Shepard AD, Evans JR, Wright DJ, Smith RF, Ernst CB. Management of infected aortoiliac aneurysms. Arch Surg 1991;126:873–8; discussion 878–9. [CrossRef]

- Raman SP, Fishman EK. Mycotic aneurysms: a critical diagnosis in the emergency setting. Emerg Radiol 2014;21:191–6. [CrossRef]

- Huang JS, Ho AS, Ahmed A, Bhalla S, Menias CO. Borne identity: CT imaging of vascular infections. Emerg Radiol 2011;18:335–43. [CrossRef]

- Macedo TA, Stanson AW, Oderich GS, Johnson CM, Panneton JM, Tie ML. Infected aortic aneurysms: imaging findings. Radiology 2004;231:250–7. [CrossRef]

- Müller BT, Wegener OR, Grabitz K, Pillny M, Thomas L, Sandmann W. Mycotic aneurysms of the thoracic and abdominal aorta and iliac arteries: experience with anatomic and extra-anatomic repair in 33 cases. J Vasc Surg 2001;33:106–13. [CrossRef]

- Lin WC, Lui CC, Lee CH, Wang HC. Unusual femoral artery mycotic aneurysm complicated by infective spondylitis. Emerg Radiol 2008;15:207–10. [CrossRef]

- Tshomba Y, Sica S, Minelli F, Giovannini S, Murri R, De Nigris F et al. Management of mycotic aorto-iliac aneurysms: a 30-year monocentric experience. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2020;24:3274–81. [CrossRef]

- Kakodkar P, Kaka N, Baig MN. A comprehensive literature review on the clinical presentation, and management of the pandemic coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Cureus 2020;12:e7560. [CrossRef]

- Hubaut JJ, Albat B, Frapier JM, Chaptal PA. Mycotic aneurysm of the extracranial carotid artery: an uncommon complication of bacterial endocarditis. Ann Vasc Surg 1997;11:634–6. [CrossRef]

- John S, Walsh KM, Hui FK, Sundararajan S, Silverman S, Bain M. Dynamic angiographic nature of cerebral mycotic aneurysms in patients with infective endocarditis. Stroke 2016;47. [CrossRef]

- Salgado AV, Furlan AJ, Keys TF. Mycotic aneurysm, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and indications for cerebral angiography in infective endocarditis. Stroke 1987;18:1057–60. [CrossRef]

- Jara FM, Lewis JF, Magilligan DJ. Operative experience with infective endocarditis and intracerebral mycotic aneurysm. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1980;80:28–30. [CrossRef]

- Oohara K, Yamazaki T, Kanou H, Kobayashi A. Infective endocarditis complicated by mycotic cerebral aneurysm: two case reports of women in the peripartum period. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1998;14:533–5. [CrossRef]

- Alfredo JM, Grinberg M, Leão PP, Chung C, Noedir A, Stolf G et al. Extracranial mycotic aneurysms in infective endocarditis. Clin Cardiol 1986; 9: 65–72 [PMID, Grinberg M, Leão PP, Chung CV, Stolf NA, Pileggi F. Clin Cardiol 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoru K, Yoshida K, Suzuki K, Matsumura R, Okuda A. Successful surgical management for multiple cerebral mycotic aneurysms involving both carotid and vertebrobasilar systems in active infective endocarditis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1994;8:508–10. [CrossRef]

- Kadowaki M, Hashimoto M, Nakashima M, Fukata M, Odashiro K, Uchida Y, et al. Radial mycotic aneurysm complicated with infective endocarditis caused by Streptococcus sanguinis. Intern Med 2013;52:2361–5. [CrossRef]

- Yuan S, Wang G. Cerebral mycotic aneurysm as a consequence of infective endocarditis: A literature review. Cor Vasa 2017;59:e257–65. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).