Submitted:

08 May 2024

Posted:

09 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Study Design

Data Extraction

Statistical Analyses

3. Results

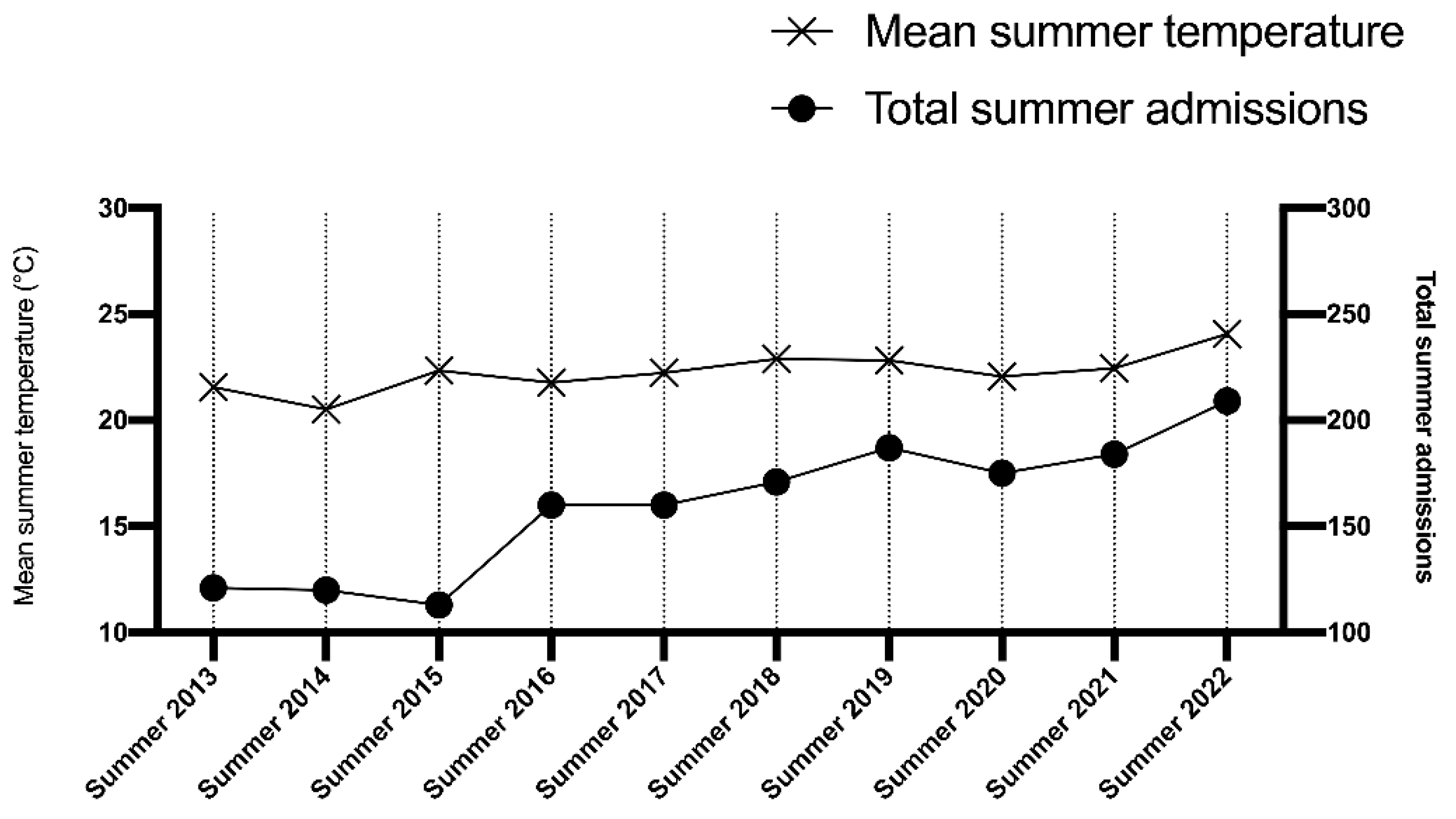

3.1. Sample Characteristics and DESCRIPTIVE statistics

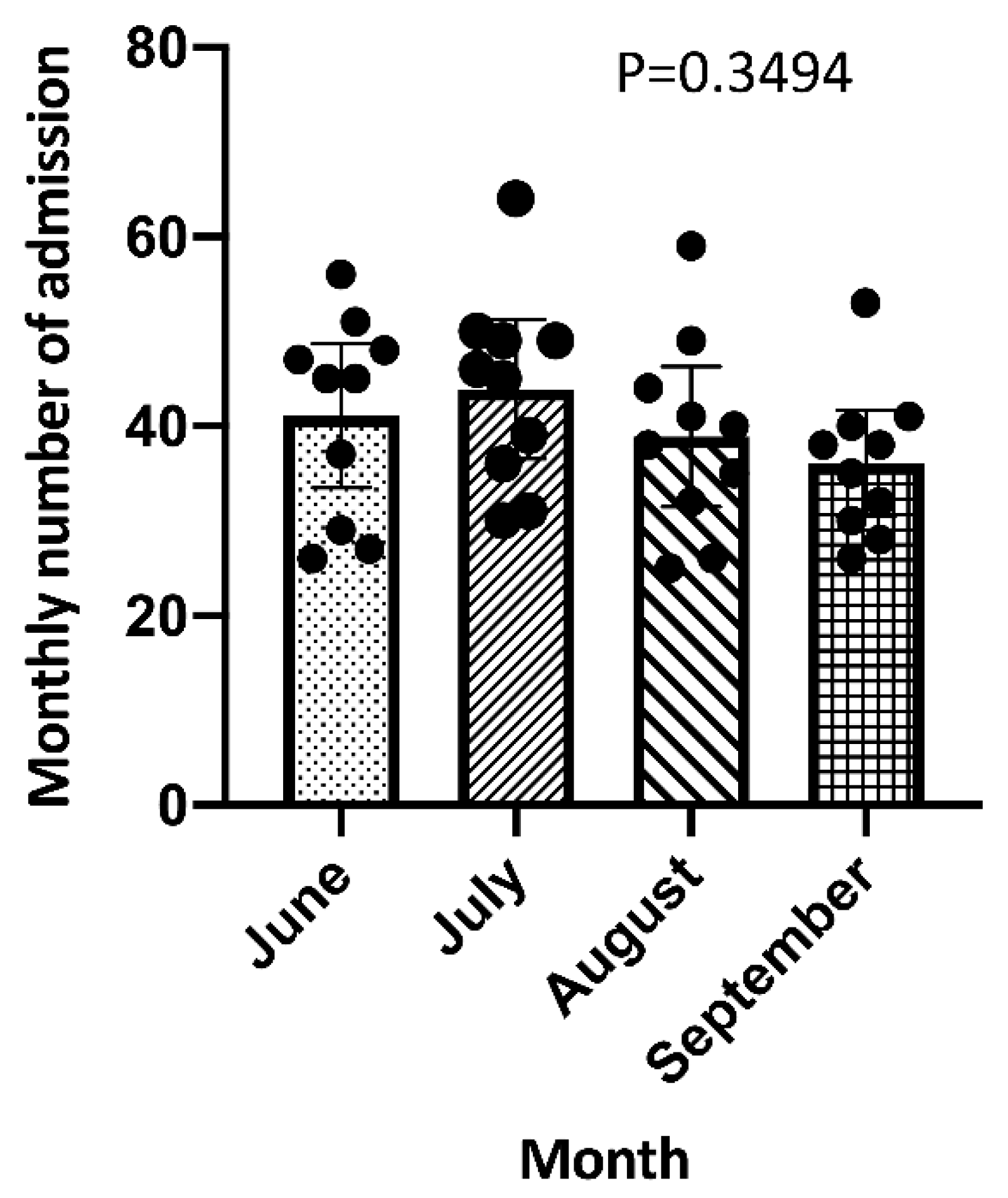

3.2. Total Number of Admissions According to Month

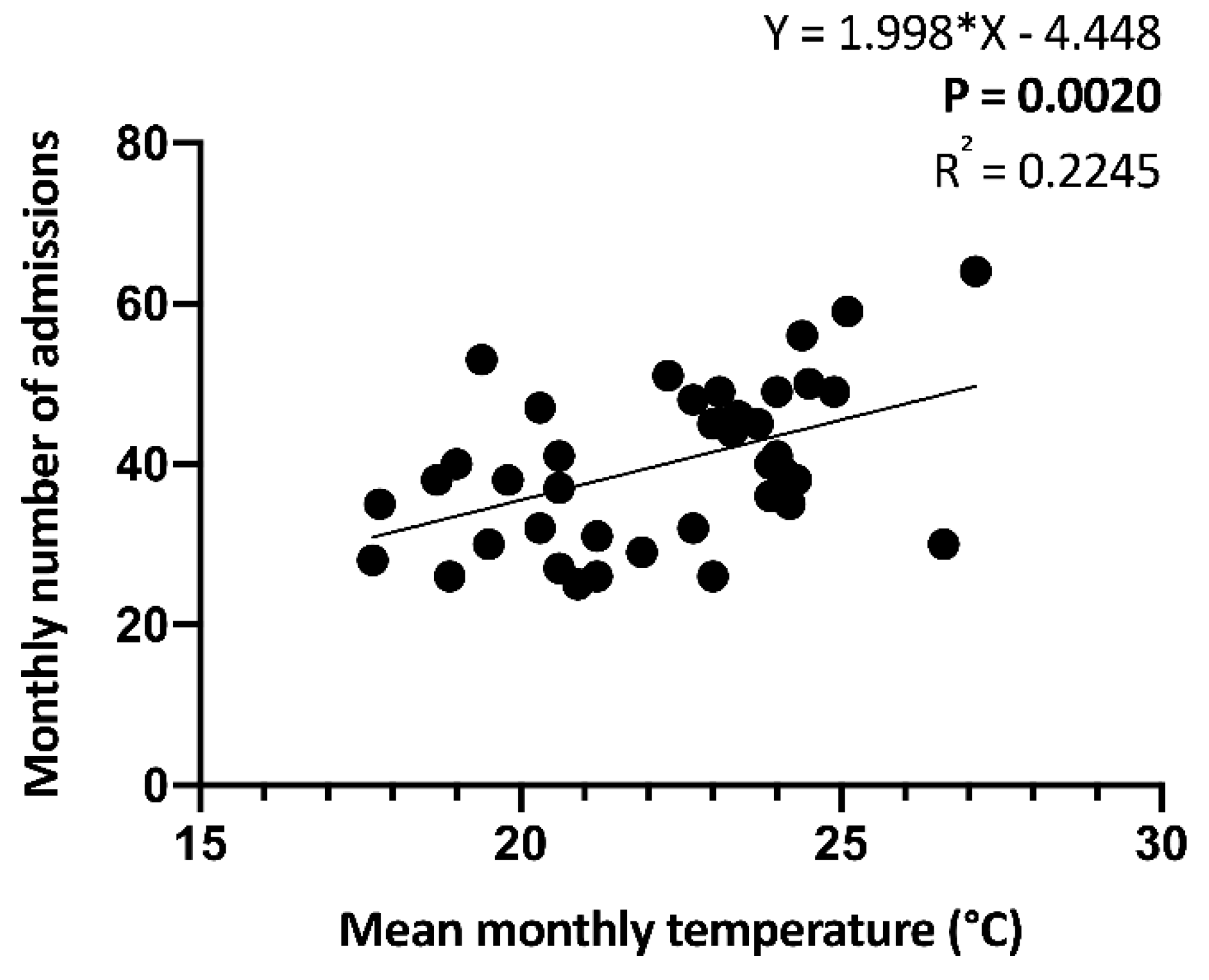

3.3. Temperature and Number of Admissions

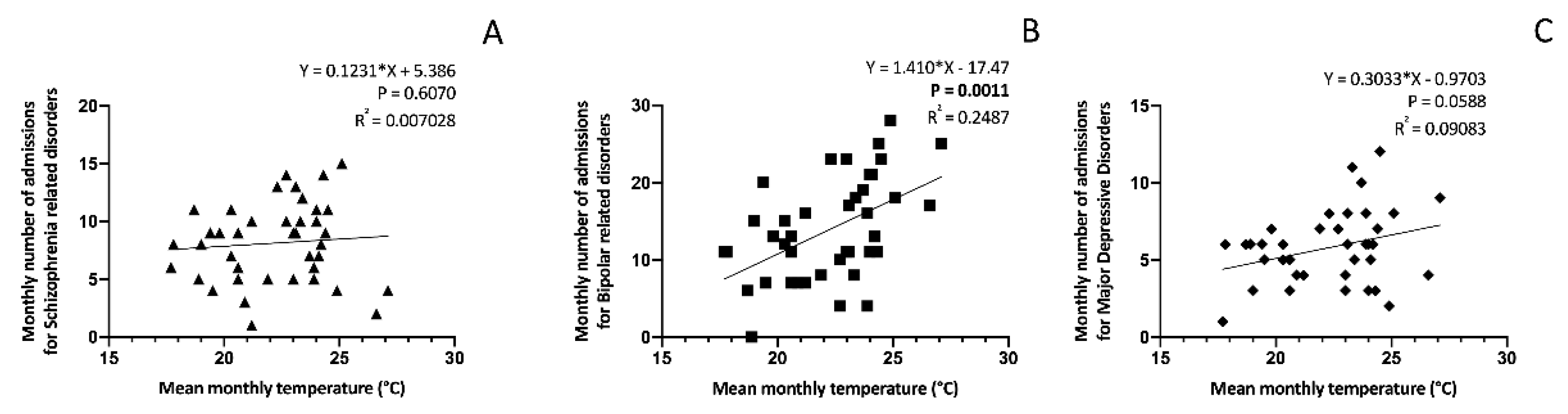

3.4. Temperature and Number of Admissions According to Diagnosis

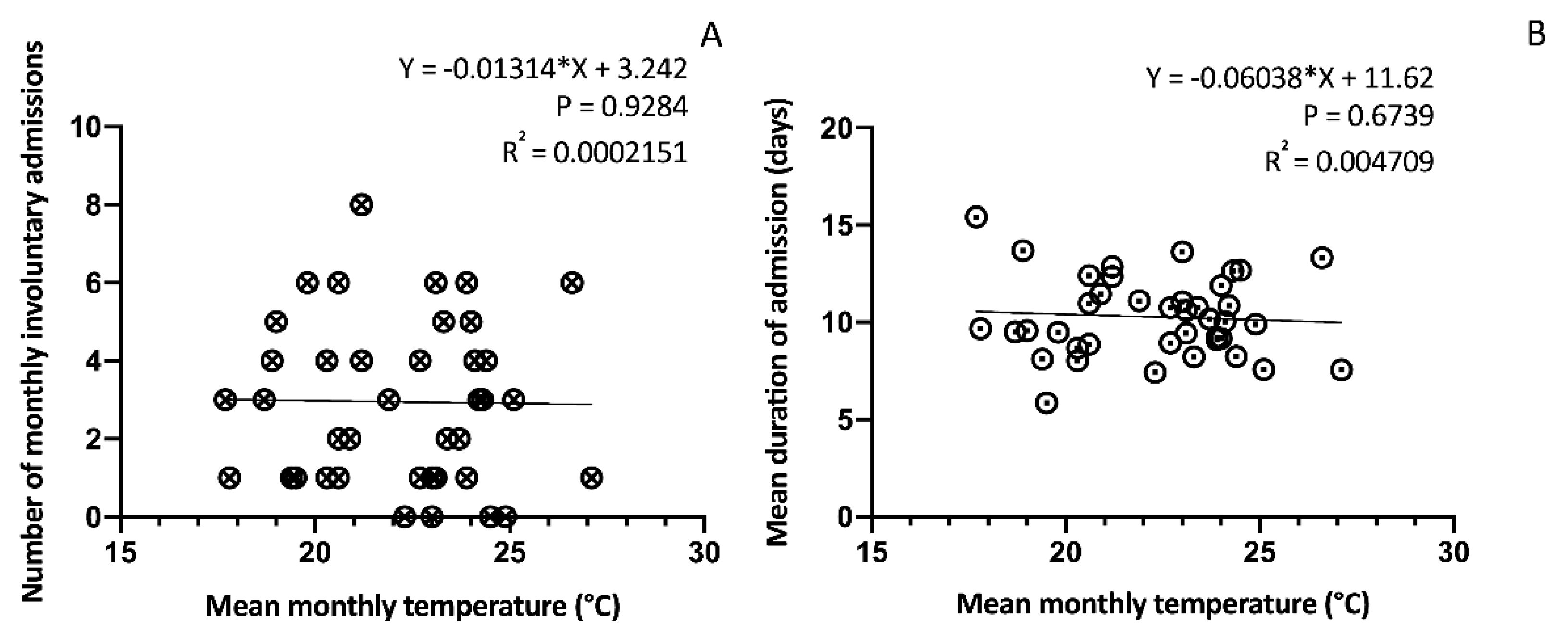

3.5. Temperature and Involuntary Admissions

3.6. Temperature and Length of Stay

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Baronetti A, Dubreuil V, Provenzale A, Fratianni S. Future droughts in northern Italy: high-resolution projections using EURO-CORDEX and MED-CORDEX ensembles. Clim Change [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 22];172(22). [CrossRef]

- Global Climate Highlights 2023 | Copernicus [Internet]. [cited 2024 Feb 22]. Available from: https://climate.copernicus.eu/global-climate-highlights-2023.

- July 2023 is set to be the hottest month on record. 2023.

- Alifu H, Hirabayashi Y, Imada Y, Shiogama H. Enhancement of river flooding due to global warming. Sci Rep [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 22];12:20687. [CrossRef]

- Christidis N, Mitchell D, Stott PA. Rapidly increasing likelihood of exceeding 50 °C in parts of the Mediterranean and the Middle East due to human influence. npj Clim Atmos Sci [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2024 Feb 22];6(45). [CrossRef]

- Hajek OL, Knapp AK. Shifting seasonal patterns of water availability: ecosystem responses to an unappreciated dimension of climate change. New Phytol. 2022 Jan 1;233(1):119–25. [CrossRef]

- Ye X, Wolff R, Yu W, Vaneckova P, Pan X, Tong S. Ambient Temperature and Morbidity: A Review of Epidemiological Evidence. Environ Health Perspect [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2024 Feb 19];120(1):19. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3261930/. [CrossRef]

- Tani M, Shinzaki S, Asakura A, Tashiro T, Amano T, Otake-Kasamoto Y, et al. Seasonal variations in gut microbiota and disease course in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS One [Internet]. 2023 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Feb 23];18(4):e0283880. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0283880.

- Celius EG, Grothe M, Gross S, Süße M, Strauss S, Penner IK. The Seasonal Fluctuation of Fatigue in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Neurol | www.frontiersin.org [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 23];1:900792. Available from: www.frontiersin.org.

- Jahan S, Cauchi JP, Galdies C, England K, Wraith D. The adverse effect of ambient temperature on respiratory deaths in a high population density area: the case of Malta. Respir Res [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Feb 23];23:299. [CrossRef]

- Gostimirovic M, Novakovic R, Rajkovic J, Djokic V, Terzic D, Putnik S, et al. The influence of climate change on human cardiovascular function. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2020 Oct 2;75(7):406–14.

- Zilbermint M. Diabetes and climate change. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect [Internet]. 2020 Sep 2 [cited 2024 Feb 26];10(5):409. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7671730/.

- Segal TR, Giudice LC. Systematic review of climate change effects on reproductive health. Fertil Steril [Internet]. 2022 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Feb 23];118(2):215–23. Available from: http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015028222003831/fulltext.

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2022 Feb 1;9(2):137–50. [CrossRef]

- Barratt H, Rojas-García A, Clarke K, Moore A, Whittington C, Stockton S, et al. Epidemiology of Mental Health Attendances at Emergency Departments: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PLoS One [Internet]. 2016 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Feb 22];11(4). Available from: https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.bibliopass.unito.it/27120350/.

- Sacchetti E, Valsecchi P, Tamussi E, Paulli L, Morigi R, Vita A. Psychomotor agitation in subjects hospitalized for an acute exacerbation of Schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2018 Dec 1;270:357–64. [CrossRef]

- Weiss AJ, Barrett ML, Heslin KC, Stocks C. Trends in Emergency Department Visits Involving Mental and Substance Use Disorders, 2006–2013. Healthc Cost Util Proj Stat Briefs [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2024 Feb 22]; Available from: https://www-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.bibliopass.unito.it/books/NBK409512/.

- Aguglia A, Moncalvo M, Solia F, Maina G. Involuntary admissions in Italy: the impact of seasonality. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract [Internet]. 2017 Oct 1 [cited 2024 Feb 19];20(4):232–8. Available from: https://iris.unito.it/handle/2318/1634552.

- Asimakopoulos LO, Koureta A, Benetou V, Lagiou P, Samoli E. Investigating the association between temperature and hospital admissions for major psychiatric diseases: A study in Greece. J Psychiatr Res. 2021 Dec 1;144:278–84. [CrossRef]

- Lee HC, Tsai SY, Lin HC. Seasonal variations in bipolar disorder admissions and the association with climate: A population-based study. J Affect Disord. 2007 Jan 1;97(1–3):61–9. [CrossRef]

- Aguglia A, Cuomo A, Amerio A, Bolognesi S, Di Salvo G, Fusar-Poli L, et al. A new approach for seasonal pattern: is it related to bipolarity dimension? Findings from an Italian multicenter study. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract [Internet]. 2021 [cited 2024 Feb 23];25(1):73–81. Available from: https://www-tandfonline-com.bibliopass.unito.it/doi/abs/10.1080/13651501.2020.1862235.

- Aguglia A, Borsotti A, Maina G. Bipolar disorders: is there an influence of seasonality or photoperiod? Brazilian J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2018 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Feb 19];40(1):6. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6899423/.

- Aguglia A, Serafini G, Escelsior A, Canepa G, Amore M, Maina G. Maximum Temperature and Solar Radiation as Predictors of Bipolar Patient Admission in an Emergency Psychiatric Ward. Int J Environ Res Public Heal 2019, Vol 16, Page 1140 [Internet]. 2019 Mar 29 [cited 2024 Feb 19];16(7):1140. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/16/7/1140/htm.

- Suzuki M, Dallaspezia S, Locatelli C, Uchiyama M, Colombo C, Benedetti F. Does early response predict subsequent remission in bipolar depression treated with repeated sleep deprivation combined with light therapy and lithium? J Affect Disord. 2018 Mar 15;229:371–6. [CrossRef]

- Pjrek E, Friedrich ME, Cambioli L, Dold M, Jäger F, Komorowski A, et al. The Efficacy of Light Therapy in the Treatment of Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Psychother Psychosom [Internet]. 2020 Jan 14 [cited 2024 Feb 23];89(1):17–24. [CrossRef]

- Sarzetto A, Cavallini MC, Fregna L, Pacchioni F, Attanasio F, Barbini B, et al. Sleep architecture modifications after double chronotherapy: A case series of bipolar depressed inpatients. Psychiatry Res. 2022 Oct 1;316:114781. [CrossRef]

- Benedetti F, Dallaspezia S, Melloni EMT, Lorenzi C, Zanardi R, Barbini B, et al. Effective Antidepressant Chronotherapeutics (Sleep Deprivation and Light Therapy) Normalize the IL-1β:IL-1ra Ratio in Bipolar Depression. Front Physiol [Internet]. 2021 Sep 1 [cited 2024 Feb 19];12:740686. Available from: www.frontiersin.org.

- Fountoulakis KN, Yatham LN, Grunze H, Vieta E, Young AH, Blier P, et al. The CINP Guidelines on the Definition and Evidence-Based Interventions for Treatment-Resistant Bipolar Disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2024 Feb 23];23(4):230–56. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ijnp/article/23/4/230/5658435.

- Niu L, Girma B, Liu B, Schinasi LH, Clougherty JE, Sheffield P. Temperature and mental health–related emergency department and hospital encounters among children, adolescents and young adults. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci [Internet]. 2023 Apr 17 [cited 2024 Feb 19];32. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC10130844/.

- Aguglia A, Serafini G, Escelsior A, Amore M, Maina G. What is the role of meteorological variables on involuntary admission in psychiatric ward? An Italian cross-sectional study. Environ Res. 2020 Jan 1;180:108800. [CrossRef]

- Page LA, Hajat S, Sari Kovats R, Howard LM. Temperature-related deaths in people with psychosis, dementia and substance misuse. Br J Psychiatry [Internet]. 2012 Jun [cited 2024 Feb 19];200(6):485–90. Available from: https://www-cambridge-org.bibliopass.unito.it/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/temperaturerelated-deaths-in-people-with-psychosis-dementia-and-substance-misuse/77BB0669DFD55C4A717B25DFA0E6EAAC.

- McWilliams S, Kinsella A, O’Callaghan E. The effects of daily weather variables on psychosis admissions to psychiatric hospitals. Int J Biometeorol [Internet]. 2013 Jul 2 [cited 2024 Feb 19];57(4):497–508. Available from: https://link-springer-com.bibliopass.unito.it/article/10.1007/s00484-012-0575-1.

- Tupinier Martin F, Boudreault J, Campagna C, Lavigne É, Gamache P, Tandonnet M, et al. The relationship between hot temperatures and hospital admissions for psychosis in adults diagnosed with schizophrenia: A case-crossover study in Quebec, Canada. Environ Res [Internet]. 2024 Apr 1 [cited 2024 Feb 19];246:118225. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0013935124001294.

- Qiu X, Wei Y, Weisskopf M, Spiro A, Shi L, Castro E, et al. Air pollution, climate conditions and risk of hospital admissions for psychotic disorders in U.S. residents. Environ Res. 2023 Jan 1;216:114636. [CrossRef]

- Jahan S, Wraith D, Dunne MP, Naish S, McLean D. Seasonality and schizophrenia: a comprehensive overview of the seasonal pattern of hospital admissions and potential drivers. Int J Biometeorol [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2024 Feb 23];64(8):1423–32. [CrossRef]

- Dumont C, Haase E, Dolber T, Lewis J, Coverdale J. Climate Change and Risk of Completed Suicide. J Nerv Ment Dis [Internet]. 2020 Jul 1 [cited 2024 Feb 23];208(7):559–65. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jonmd/fulltext/2020/07000/climate_change_and_risk_of_completed_suicide.6.aspx.

- Obradovich N, Migliorini R, Paulus MP, Rahwan I. Empirical evidence of mental health risks posed by climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A [Internet]. 2018 Oct 23 [cited 2024 Feb 26];115(43):10953–8. Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6205461/.

- Thompson R, Hornigold R, Page L, Waite T. Associations between high ambient temperatures and heat waves with mental health outcomes: a systematic review. Public Health. 2018 Aug 1;161:171–91. [CrossRef]

- Oosthuizen J, Hime NJ, Bi P, Mathieson A, Natur S, Damri O, et al. The Effect of Global Warming on Complex Disorders (Mental Disorders, Primary Hypertension, and Type 2 Diabetes). 2022 [cited 2024 Feb 23]. [CrossRef]

- Abreu T, Bragança M. The bipolarity of light and dark: A review on Bipolar Disorder and circadian cycles. J Affect Disord. 2015 Oct 1;185:219–29. [CrossRef]

- Linares C, Culqui D, Carmona R, Ortiz C, Díaz J. Short-term association between environmental factors and hospital admissions due to dementia in Madrid. Environ Res. 2017 Jan 1;152:214–20. [CrossRef]

- García FM, Boada SS i, Collsamata AX, Joaquim IG, Pérez YA, Tricio OG, et al. Meteorological factors and psychiatric emergencies. Actas Españolas Psiquiatr [Internet]. 2009 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Apr 7];37(1):34–41. Available from: https://actaspsiquiatria.es/index.php/actas/article/view/822.

- Saccaro LF, Crokaert J, Perroud N, Piguet C. Structural and functional MRI correlates of inflammation in bipolar disorder: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023 Mar 15;325:83–92. [CrossRef]

- Valvassori SS, Bavaresco D V., Feier G, Cechinel-Recco K, Steckert A V., Varela RB, et al. Increased oxidative stress in the mitochondria isolated from lymphocytes of bipolar disorder patients during depressive episodes. Psychiatry Res. 2018 Jun 1;264:192–201. [CrossRef]

- Kamintsky L, Cairns KA, Veksler R, Bowen C, Beyea SD, Friedman A, et al. Blood-brain barrier imaging as a potential biomarker for bipolar disorder progression. NeuroImage Clin. 2020 Jan 1;26:102049. [CrossRef]

- McAllister MS, Olagunju AT. Revisiting the unmet mental health needs in Canada: Can PAs be part of the solution? J Am Acad Physician Assist [Internet]. 2023 Dec 1 [cited 2024 Feb 27];36(12):42–5. Available from: https://journals.lww.com/jaapa/fulltext/2023/12000/revisiting_the_unmet_mental_health_needs_in.11.aspx.

| Total number of admissions | 1600 |

| Age, mean (+/-SD) | 45.74 (+/-15.51) years |

| Gender, n(%) |

878 (54.87) 722 (45.13) |

| Male Female | |

| Main diagnosis, n(%) |

556 (34.75) 231 (14.44) 325 (20.31) |

| BD MDD SCZ | |

| Type of admission, n (%) |

1482 (92.62) 118 (7.38) |

| Voluntary Involuntary | |

| Duration of admission, mean (+/- SD) | 9.99 (+/-8.95) days |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).