1. Introduction

In 2019, the Corporation for National and Community Service (CNCS) reported that approximately 30% of the U.S. population, or about 77.95 million people, engaged in volunteer service, contributing 5.8 billion hours valued at approximately $147 billion; addi-tionally, volunteers under the U.S. Administration for Community Living (ACL) contrib-uted $1.7 billion that same year. Australian Bureau of Statistics data from 2021 shows that around 14.6 million Australians (44.2% of the population) engage in volunteer work at least once a week, with a total economic value of AU$29 billion, accounting for 1.6% of the GDP. In Taiwan, the Ministry of Health and Welfare reported that in 2022, over 1.04 mil-lion volunteers provided approximately 128 million hours of service, with a total eco-nomic value exceeding NT$23.3 billion.

Volunteers provide significant economic value to society, yet Forner’s research based on Self-Determination Theory has identified a global decline in the number of volunteers, leading to intensified competition for volunteer resources and challenges in retaining volunteers. Poor leadership is identified as a crucial factor in volunteer turnover [

1]. From the perspective of general organizational management practices, it is more advantageous to expect an organization to establish ‘good mechanisms’ to retain volunteers rather than hoping for a wise leader. Nguyen et al.‘s study suggests the adoption of systems thinking as a driving factor in policy-making. Systems thinking is an interdisciplinary approach that integrates diverse perspectives and stakeholders into the policy-making process. A systematic leadership style facilitates internal organizational change and innovation, enhancing the organization’s ability to tackle complex challenges [

2]. To integrate different viewpoints, leaders must possess extensive knowledge, innovative thinking, strategic vision, and leadership capabilities. Such leaders can drive organizational innovation, altering organizational structures, management styles, and processes to improve organizational efficiency, flexibility, and innovative capacity, thereby propelling overall business development and competitiveness [

3].

From the perspective of volunteer management, traditional methods of using motivation and satisfaction to predict volunteers’ organizational commitment are due for a change. Warner, Newland, & Green applied the Kano method developed in the early 1980s to improve volunteer systems. They argue that merely measuring motivation and satisfaction might not provide sufficient insights to enhance volunteer systems. While understanding volunteers’ levels of motivation and satisfaction is important, these metrics may not predict key outcomes such as commitment to the organization, willingness to volunteer again, or encourage others to volunteer [

4]. Zievinger & Swint suggest that to in-crease volunteer motivation and retention, organizations need to implement different methods and strategies. This includes providing appropriate training, recognition, and feedback, enhancing communication, offering support and assistance, and creating a positive working environment [

5].

These studies demonstrate that exploring factors to enhance volunteer organizational commitment is feasible. Psychological ownership is an intriguing element in the organizational domain. Kim & So’s research highlights that psychological ownership is a concept that has attracted extensive attention in the business sector, significantly impacting organizational and individual behavior and outcomes. From the early theoretical foundations of psychological ownership to contemporary research on its application and impact within organizations, the concept of psychological ownership has been extensively explored and developed. Studies indicate that fostering a sense of psychological ownership can enhance employee engagement, teamwork, innovation capabilities, satisfaction, and loyalty, thereby improving organizational performance and competitive advantage. Therefore, organizations should recognize the importance of psychological ownership and incorporate it into their management strategies to achieve better performance and employee satisfaction [

6].

However, research on the application of psychological ownership to volunteer organizational commitment is scant. Therefore, this study aims to discuss the impact of volunteers’ psychological ownership and functional motivation on organizational commitment, bringing a new perspective on psychological ownership to volunteer managers to enhance innovative thinking in promoting volunteer organizational commitment.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Volunteer Motivation

From 1927 to 1932, George Elton Mayo, a psychology professor at Harvard University, developed the theory of the Hawthorne Effect, which paved the way for various motivation theories. Clary et al. (1988) introduced the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI), a tool for assessing volunteer motivations, identifying six volunteer functions: enhancement, understanding, protective, social, value, and career. These dimensions have become essential scales in volunteer research and heavily relied upon as a survey tool [

7].

Suandi highlighted that most studies on motivation utilize factor analysis or content analysis to categorize volunteer motivations into: (1) egoism, which refers to motivations for enhancing personal benefits; (2) altruism, which describes the behavior of helping others without expecting rewards; and (3) social obligation, where volunteers feel a duty to ‘give back to society,’ which inspires their participation [

8].

Newton et al. noted the increasing dependency on volunteers in Australia, emphasizing learning and development opportunities (LDOs) as a means to retain volunteers. They revealed that LDOs play a significant role in retaining volunteers, particularly those volunteering to build self-esteem (enhancement motivation), who are most likely to re-main and show higher organizational commitment and intent to stay. Conversely, those volunteering for career purposes, once they gain the desired skills, often transition to paid positions. Social motivations were not predictive of volunteer retention [

9].

Chaddha & Rai synthesized various studies to develop a conceptual model of volunteer motivation, acknowledging that volunteer service is a multifaceted structure. Factors include recognition, social interaction, reciprocity, responsiveness, self-esteem, societal involvement, values, understanding, protection, and career development, aligning closely with the VFI [

10].

Zievinger & Swint studied volunteers at festival events in the hospitality industry, identifying factors affecting volunteer retention such as lack of recognition and feedback, inadequate training, insufficient communication, and lack of support. They stressed the importance of volunteer management, ensuring that organizations provide adequate support, training, communication, and recognition to maintain volunteers’ enthusiasm and participation [

4].

Kim, Kim, & Lee assessed altruistic and egoistic motivations through value and enhancement motivations respectively, exploring their relationship with volunteer motivation, value internalization, and retention. They found that altruistic motivation negatively correlated with participation rates, whereas egoistic motivation showed a positive correlation. Value internalization also positively explained participation rates. The study suggests that recruitment should consider the alignment between volunteer motivations and the nature of the volunteer activities, and that enhancing value internalization during training can improve volunteer engagement and retention rates [

11].

Merrilees, Miller, and Yakimova pointed out key determinants for volunteer retention, including job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and altruistic motivations. The importance of these factors may vary at different stages of a volunteer’s lifecycle, but altruistic motivation plays a significant role in the later stages of continued involvement [

12].

Zhou & Kodama conducted a meta-analysis using the Volunteer Functions Inventory to examine the predictors of volunteer satisfaction, commitment, and behavior. Their findings indicate that different volunteer motivations significantly influence commitment, with all six motivations predicting positive outcomes, among which values emerged as the strongest predictor [

13].

2.2. Organizational Commitment

The concept of organizational commitment originated from Whyte’s “The Organization Man,” which portrayed organizational members not merely as employees but as individuals whose ultimate personal need is ‘belonging to the organization’—a notion that involves an emotional attachment and a sense of belonging [

14]. Grusky in “Career Mobility and Organizational Commitment” initiated the trend of applying the concept of organizational commitment in practice. His research indicated that organizational commitment is closely related to the concepts of identification, centripetal force, and loyalty, and is intricately linked to organizational development; additionally, he noted that re-wards provided by organizations significantly enhance commitment [

15].

Mowday and colleagues expanded the concept of organizational commitment, turning it into a significant subject within the field of management science and a crucial direction for organizational behavior studies [

16]. The theoretical development of the concept aimed to explain the phenomenon of participation in social organizations [

17,

18,

19], with factors influencing organizational commitment including motivation. Al-Madi et al. con-firmed that employee motivation significantly impacts affective and continuance commitments within an organization [

20]. Altindis also established a positive relationship between the level of organizational commitment and work motivation among healthcare professionals [

21].

Studies on organizational commitment have also extended into organizational psychology and behavior [

22]. Employee commitment is vital as it necessitates the alignment of employees’ interests, goals, and needs with those of the organization to facilitate efficient work [

23]. Pi, Chiu, & Lin investigated the impact of job stress, job satisfaction, and work values on organizational commitment among employees of different job types in an airline, finding divergent perspectives among employee categories on job satisfaction, work values, and organizational commitment. Employees with higher job accomplishment and self-fulfillment or those who experience professional knowledge tend to exhibit stronger organizational commitment [

24].

Asaloei et al. found significant positive correlations between job stress, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction with organizational commitment among healthcare workers, indicating a substantial impact on their commitment to the organization [

25]. In discussing organizational behavior, it is essential to consider non-profit organizations (NPOs), which play a crucial role in the modern economic system, especially as governance in NPOs has increasingly become a focus of organizational studies. Cornforth [

26] noted that few studies focus on key stakeholders in NPOs such as donors, funders, beneficiaries, and volunteers. The governance relationship between NPOs and internal stake-holders, such as volunteers, particularly regarding the role volunteers might play in implementing sustainable and effective strategies, has been underexplored [

27,

28].

Van Vuuren et al. compared paid and unpaid workers in non-profit organizations, finding that volunteers exhibited significantly higher levels of emotional commitment but lower levels of continuance commitment. Volunteers also demonstrated higher levels of normative commitment compared to paid workers [

29]. A study on volunteers from Filipino educational partners elucidated the stages experienced in addressing their commitment to organizational services, resulting in the development of a selfless theory, concluding that organizational commitment involves an individual’s psychological attachment, participation, and identification [

30].

Engelberg et al. studied three commitment targets among volunteers at a sports center: the organization (sports center), the volunteer work team, and the volunteer role, using Mowday et al.‘s conceptualization of the organizational commitment inventory. Data indicated that affective items had higher loadings than normative items from other structures, suggesting that sports volunteers are perceived as strongly committed to both sports and a type of community involvement [

31].

Juaneda-Ayensa et al. examined the human and organizational commitment: internal customer connections within non-profit organizations, analyzing the nature of the links between individuals and organizations from an organizational psychology perspective. Evidence highlighted distinctions between a sense of identity and the connections arising from a sense of pride [

32].

Harmon-Darrow & Xu compared predictive variables of burnout, exploring strategies to retain volunteer mediators. They discovered that enhancing lateral associations among mediators could be an effective and pragmatic management strategy, serving well the participants, volunteer mediators, and programs, and preventing job burnout [

33].

2.3. Psychological Ownership

The exploration of psychological ownership dates back to early studies, such as those by Kline & France, who investigated the origins and nature of instincts and motivations in the process of property accumulation. They further attempted to thoroughly describe the psychopathologies triggered by the awareness of possession, highlighting the role of property in mental development [

34]. Pierce, Rubenfeld, and Morgan defined psychological ownership as a psychological state where employees feel that specific targets within the organization, such as items, the organization itself, jobs, or technology, are ‘Mine’ or ‘Ours’ [

35].

Dawkins et al. reviewed 40 studies focusing on employee psychological ownership, synthesizing theoretical trends and distinguishing between organization-based and job-based psychological ownership. They discussed the premises of psychological ownership and its moderating effects [

36]. Liu et al. found that employees’ power distance mediated by organization-based psychological ownership, can lessen the impact of participative decision-making and a self-managing team atmosphere on job outcomes, based on organizational esteem and effective organizational commitment [

37].

Muhammad and Rashid explored how employees’ psychological ownership of their jobs affects their organizational commitment. The findings indicate a correlation between psychological ownership and organizational commitment, with employees’ psychological ownership influencing their level of commitment to the organization. They recommended that managers should employ strategies to motivate employees, emphasize collective roles, and implement reward systems to enhance employees’ sense of psychological ownership, which in turn affects their organizational commitment [

38].

Boonsiritomachai et al., focusing on employees of a state-owned telecommunications company, found that psychological ownership had a significant impact on organizational commitment, primarily through ‘sense of belonging’ and ‘sense of job responsibility’. The study indicated that an employee’s sense of belonging to the organization and responsibility towards their job significantly influences the enhancement of organizational commitment [

39].

From a psychological and spiritual perspective, research on psychological ownership has expanded from the individual to the societal level, starting from ‘home’ to ‘organization’; from psychological motives to behaviors; from management to marketing, forming an important research orientation across disciplines. Renz and Posthuma provided a comprehensive review of the development of psychological ownership theory, emphasizing the evolution over the past 30 years, including: individual psychological ownership and its formative and influencing factors on organizations or jobs. The impact of psycho-logical ownership at team and organizational levels, how to manage and promote its perception, psychological ownership feelings across different cultural backgrounds, international comparisons, and how leaders and managers can influence employees’ feelings of psychological ownership and apply the theory in management practices [

40].

While psychological ownership has established its significance in studies of employee organizations, its exploration in the critically impactful domain of volunteerism is sparse. Ainsworth shifted focus towards organizational volunteers, attempting to under-stand the relationship between feelings of ownership and volunteer service, examining how the ownership consciousness of providers in non-profit organizations affects volunteers’ attitudes and motivations. The study suggested that psychological ownership is a factor in retaining volunteers in community-based non-profit organizations. Results indicated that volunteer service indeed increases the feeling of ownership, and volunteers’ sense of ownership positively affects volunteer behavior. However, time pressure is a significant moderator in these relationships, with different volunteer behaviors observable among volunteers under high and low time pressures [

41].

3. Research Hypotheses and Methods

3.1. Research Hypotheses

Volunteer utilization is now a crucial aspect of organizational management. Based on the literature, this study focuses on volunteers at national primary schools, examining the relationship between psychological ownership and volunteer motivation, and organizational commitment. The hypotheses are set as follows:

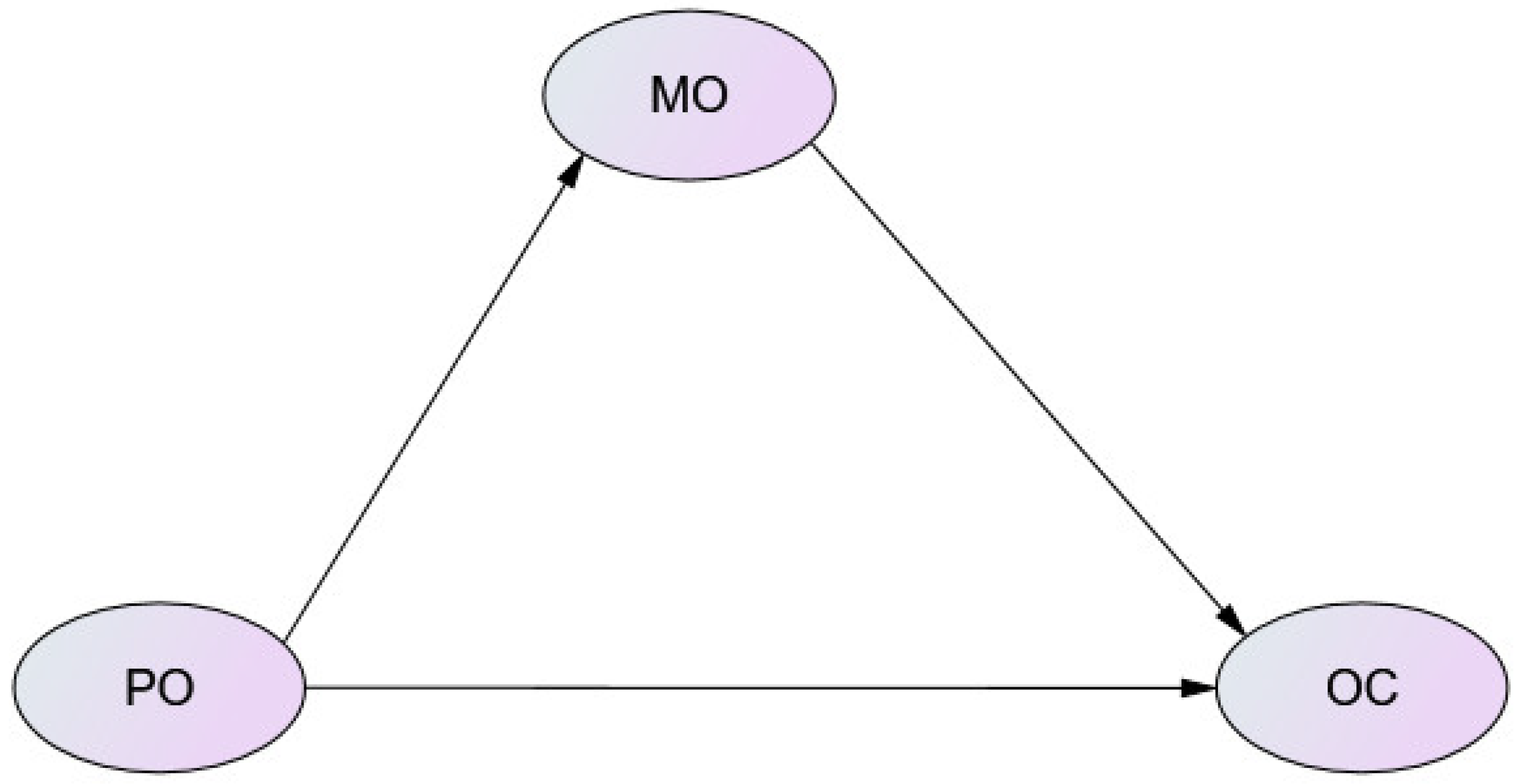

H1. Psychological ownership has a positive significant effect on volunteer motivation.

H2. Volunteer motivation has a positive significant effect on organizational commitment.

H3. Psychological ownership has a positive significant effect on organizational commitment.

H4. Psychological ownership significantly positively influences organizational commitment through volunteer motivation.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

Figure 1.

Research framework.

3.2. Questionnaire Development

The scale for psychological ownership in this study is based on a 16-item measure developed by Avey et al. [

42], adapted into Chinese after semantic verification by CHEN, HUI, & XI [

43]. Given the target population of volunteers, four items related to the dimension of Territoriality, which are less applicable to volunteers, were omitted. Volunteer motivation was measured using the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI), which comprises 30 items across six indices developed by Clary et al. [

6], and translated into Chinese by Ho et al. [

44], referencing Lee’s [

45] questionnaire used in studies on volunteers in Hong Kong. Organizational commitment was based on the concepts of Buchanan [

46]; Mowday [

47], and Meyer & Allen [

48], covering three dimensions: value commitment, retention commitment, and effort commitment, with an 18-item scale developed in Chinese for this study.

3.3. Sample

Surveys were distributed among volunteer service management units at 13 primary schools in Taichung City, randomly administered to the schools’ volunteers. A total of 227 questionnaires were collected, with 212 valid responses used for data analysis.

3.4. Instruments

3.4.1. Reliability and Convergent Validity

All constructs demonstrated robust composite reliability and average variance extracted (AVE), meeting the recommended standards [

49,

50,

51]. Please refer to

Table 1, which details the standard deviations and composite reliabilities ranging from 0.724 to 0.982. These results confirm the acceptable convergent validity as shown in

Table 1.

3.4.2. Item Parceling

In structural equation modeling, this study employs the maximum likelihood (ML) estimation method, which necessitates a large sample size and multivariate normal distribution of data. However, achieving multivariate normality is nearly impossible in latent model analysis due to constructs needing to be measured by multiple items, and a prerequisite is that the measurement items must be moderately to highly correlated with each other. Thus, Hair et al. recommend that item parceling has several advantages for the measurement model, including enhancing stability, reducing violations of the normal distribution assumption, reducing the number of estimated parameters, increasing the item-to-sample ratio, more stable parameter estimates, reducing uniqueness in measurement issues, and simplifying model interpretation. Item parceling can be defined as an aggregate level indicator composed of the mean (or sum) of two or more construct items [

52].

With a total of 212 samples, this study qualifies as a small sample size in the context of structural equation modeling. To achieve stability in the survey results, the method of item parceling is used to simplify the research structure [

53].

3.4.3. Discriminant Validity

Discriminant validity was assessed following the method proposed by Fornell and Larcker [

49]. The results show that the square root of most AVEs exceeds the correlation coefficients (see

Table 2), except for the square root of AVE for MO, which is slightly less than the correlation coefficient between MO and OC. Given that the discrepancy is less than 0.1, this difference is considered negligible [

54], hence the model still possesses adequate discriminant validity.

4. Results

4.1. Sample profile

The research encompasses a sample size of 212 individuals. The sample a majority of female (94.3%). Most of the academic qualifications are from college or university (67.5%). Most of the marriages are married with spouse (85.4%). Half of the participants in volunteer training participate occasionally (50.5%). About half of the respondents have no religious affiliation. More than 70% of people decide to volunteer on their own (70.3%), as shown in the

Table 3.

The research encompasses a sample size of 212 individuals. The average values of age is 48.59. The average values of seniority is 92.07. The average values of working hours per week is 6.396, as shown in the

Table 4.

4.2. Model Fit

Tiffany and Schumacker recommend reporting nine widely accepted fit indices to assess model fit. A good model fit is typically indicated by a chi-square to degrees of freedom ratio less than 3 [

55]. Additionally, Hu and Bentler suggest independently evaluating each fit index while using stricter model fit criteria for control, such as Comparative Fit Index (CFI) > 0.90, Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) < 0.08, and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.08 [

56].

Table 5.

Model fit.

| Model fit |

Criteria |

Model fit of research model |

Model fit of Bollen-Stine |

| χ2

|

The small the better |

414.444 |

86.174 |

| DF |

The large the better |

62 |

62 |

| Normed Chi-sqr (χ2/DF) |

1<χ2/DF<3 |

6.685 |

1.390 |

| RMSEA |

<0.08 |

0.164 |

0.043 |

| SRMR |

<0.08 |

0.053 |

0.053 |

| TLI (NNFI) |

>0.9 |

0.864 |

0.991 |

| CFI |

>0.9 |

0.892 |

0.993 |

| GFI |

>0.9 |

0.771 |

0.974 |

| AGFI |

>0.9 |

0.663 |

0.968 |

4.3. Path Analysis

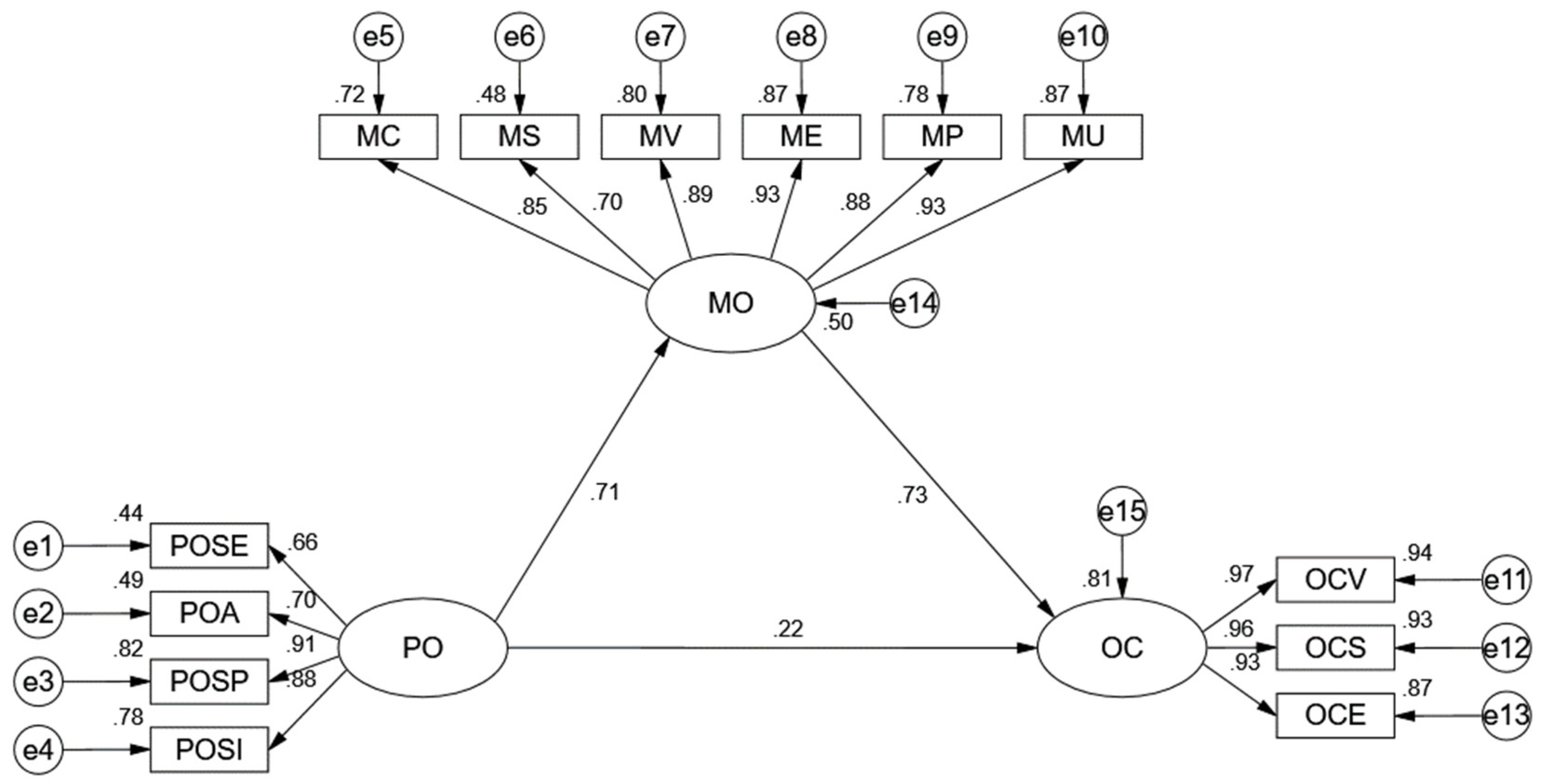

As shown in

Table 6, the results of the path analysis indicate significant relationships between the constructs. Psychological Ownership (PO) significantly affects Motivation (MO) with a coefficient (b = 1.032, p < 0.001), explaining 50.2% of the variance in MO.

Both Motivation (MO) (b = 0.793, p < 0.001) and Psychological Ownership (PO) (b = 0.347, p < 0.001) have significant effects on Organizational Commitment (OC). The combined effect of these values explains 80.8% of the variance in OC.

Figure 2.

SEM model. Note: PO, Psychological Ownership; MO, Motivation; OC, Organizational Commitment.

Figure 2.

SEM model. Note: PO, Psychological Ownership; MO, Motivation; OC, Organizational Commitment.

4.4. Mediation Effects

The most commonly employed method to assess the indirect effects of mediating variables is the bootstrapping method. Compared to the causal steps approach and the Sobel test, bootstrapping has the advantage of not requiring the assumption of normal distribution, making it suitable for situations with small sample sizes or skewed data distributions. Additionally, by repeatedly sampling randomly from the original dataset, calculating statistics, and repeating this process 1,000 times or more, a sampling distribution of the indirect effects can be generated. This method produces confidence intervals that are more robust than those generated by traditional methods [

57,

58].

The confidence intervals (C.I.) obtained through the bootstrapping method are statistically robust, and it is preferable to use the bias-corrected bootstrapping approach. A significant mediating effect is indicated when zero is not found between the lower and upper limits of the confidence interval [

58,

59].

As shown in

Table 7, the analysis reveals that zero is not present between the confidence intervals, indicating a significant mediating effect. The total indirect effect demonstrates the mediating role of PO→MO→OC (C.I. [0.513 to 1.125]), supporting the four re-search hypotheses.

5. Discussion and Future Research Recommendations

5.1. Discussion and Findings

Numerous past studies have utilized the Volunteer Functions Inventory (VFI) as a means to assess the motivational underpinnings of volunteer commitment, consistently finding that motivations influence organizational commitment [

8,

12]. Even when categorizing the VFI into the most frequently discussed altruistic and egoistic motives, it was found that altruism significantly impacts organizational commitment [

10,

11]. Studies concerning psychological ownership among corporate employees have also demonstrated that psychological ownership affects organizational commitment [

35,

36,

37,

38].

This study examined the relationship between psychological ownership, motivation, and organizational commitment among educational volunteers, also comparing the relative impact strengths of psychological ownership and motivation on organizational commitment. The findings reveal significant effects: psychological ownership significantly influences volunteer motivation; volunteer motivation positively impacts organization-al commitment; and psychological ownership positively influences organizational commitment. Psychological ownership was found to indirectly influence organizational commitment through volunteer motivation, demonstrating a mediating effect of volunteer motivation between psychological ownership and organizational commitment. Comparatively, the total effect of psychological ownership (1.165) was greater than its direct effect on organizational commitment (0.347), indicating that besides the direct impacts, psychological ownership also indirectly influences organizational commitment through motivational pathways. Moreover, the indirect effect of motivation on organizational commitment (0.818) highlights its mediating role between psychological ownership and organizational commitment.

The research findings support the notion that ‘psychological ownership among volunteers is a significant factor influencing organizational commitment.’ This equates to recommending a new method to volunteer managers for enhancing volunteer organizational commitment by leveraging the concept of psychological ownership. Expanding the mindset and knowledge of leaders about fostering volunteer commitment provides the first pathway to organizational innovation: leadership transformation. When leadership knowledge is diversified, as Yang and Wang suggest in their recommendations for cross-sectoral collaboration in sustainable contexts, trust can achieve better information sharing, collaboration, and problem-solving. An innovatively assembled team with di-verse viewpoints and expertise can foster creativity and innovative solutions [

3].

5.2. Management Implications

Given that psychological ownership is a significant factor affecting organizational commitment, managers can contemplate the development of psychological ownership concepts starting from “property rights.” To promote organizational commitment, the objective would be to enable volunteers to physically possess an item, thereby stimulating innovative thinking among managers. This can involve incorporating new elements of psychological ownership within the organizational system to innovate volunteer management.

For instance, practical measures could include providing volunteers with a designated workspace or rest area equipped with fixed furniture, establishing a ‘home base’ that fosters a sense of ownership. Alternatively, supplying volunteers with ‘uniforms’ can offer clear identification and symbolism during service. These tangible assets, such as the physical ‘home base’ or uniforms, can then be imbued with value or symbolic meaning, transitioning into ‘psychological ownership’. For example, empowering volunteers to personalize the home base as their ‘second home’ and conveying that wearing the uniform signifies sharing the organization’s honor and disgrace. Upon completing assigned tasks, volunteers might receive small tokens of appreciation or badges that signify their contributions at various stages, recognized and celebrated by other volunteers who articulate the value and meaning of these awards, thereby enhancing the volunteers’ perception of their own value and increasing their commitment to continue serving.

In the context of educational volunteers at national schools, volunteers conceptually assist school staff in advancing educational work, with actual tasks including guiding students safely to and from school, telling moral stories during morning self-study sessions, providing after-school homework help for children whose parents are still at work, assisting with school recycling initiatives, and organizing library resources and lending. School volunteers constitute an effective operational system within the school: students receive education reassured by the volunteers, while teachers and staff gain deeper in-sights into students’ backgrounds and individual needs through interactions with parent volunteers.

When a principal integrates resources, centering psychological ownership at the axis of the volunteer system’s operation, and merges the volunteer system with the school staff system through a decentralized decision-making structure, empowering the volunteer system represents an organizational innovation. By granting decision-making authority to more individuals, the organization can enhance member participation and a sense of responsibility, increase organizational flexibility and responsiveness, and encourage active employee engagement, new ideas, and ongoing innovation and improvement [

60].

5.3. Research Limitations and Suggestions

Although this study underscores the potential of psychological ownership as a tool to promote organizational commitment, it is limited by the focus on educational volunteers, necessitating further verification among different types of volunteers to avoid overly broad conclusions. Additionally, as a preliminary study using a small sample, its explanatory power is limited. Future researchers interested in exploring volunteer psychological ownership could expand the categories and number of volunteers to potentially establish more convincing conclusions.

References

- Forner, V. Reducing Turnover in Volunteer Organisations: A Leadership Intervention Based on Self-Determination Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, School of Management, Operations and Marketing, University of Wollongong, Wollongong, Australia, 2019; Available online: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses1/692 (accessed on 20 April 2024).

- Nguyen, L.K.N.; Kumar, C.; Shah, M.B.; Chilvers, A.; Stevens, I.; Hardy, R.; Sarell, C.J.; Zimmermann, N. Civil Servant and Expert Perspectives on Drivers, Values, Challenges and Successes in Adopting Systems Thinking in Policy-Making. Systems 2023, 11, 193. [CrossRef]

- Juracka, D.; Nagy, M.; Valaskova, K.; Nica, E. A Meta-Analysis of Innovation Management in Scientific Research: Unveiling the Frontier. Systems 2024, 12, 130. [CrossRef]

- Warner, S.; Newland, B.L.; Green, B.C. More Than Motivation: Reconsidering Volunteer Management Tools. J. Sport Manag. 2011, 25, 391–407. [CrossRef]

- Zievinger, D.; Swint, F. Retention of festival volunteers: Management practices and volunteer motivation. Res. Hosp. Manag. 2018, 8, 107–114. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Li, J.; So, K.K.F. Psychological ownership research in business: A bibliometric overview and future research directions. J. Bus. Res. 2024, 174. [CrossRef]

- Clary, E.G.; Snyder, M.; Ridge, R.D.; Stukas, A.A.; Copeland, J. Understanding Volunteer Motivation: A Functional Approach. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 589–599.

- Suandi, A. A Study of Factors Influencing Volunteerism in Indonesia. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1991.

- Newton, J.; Smith, R.; Smith, D. The Role of Learning and Development Opportunities in Volunteer Retention: An Australian Study. Aust. J. Volunt. 2014, 25, 108–122.

- Chaddha, M.; Rai, R.S. Volunteer Motivation: A Conceptual Framework and Empirical Examination. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 137, 651–667.

- Kim, B.J.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, J. The Relationships Among Altruism, Egoism, Value Internalization, and Volunteer Retention: A Structural Equation Modeling Analysis. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 50, 286–309.

- Merrilees, B.; Miller, A.; Yakimova, L. Understanding Volunteer Retention: A Review of the Literature. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2020, 25, 228–246.

- Zhou, M.; Kodama, C. Meta-Analysis of Volunteer Motives Using the Volunteer Functions Inventory to Predict Volunteer Satisfaction, Commitment, and Behavior. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2023, 52, 9–24. [CrossRef]

- Whyte, W.H. The Organization Man. Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1956.

- Grusky, O. Career Mobility and Organizational Commitment. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1966, 31, 487–498.

- Mowday, R.T.; Porter, L.W.; Steers, R.M. Employee Organization Linkage: The Psychology of Commitment, Absenteeism, and Turnover. Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974.

- Kelman, H.C. Compliance, Identification, and Internalization: Three Processes of Attitude Change. J. Confl. Resolut. 1958, 2, 51–60.

- Etzioni, A. A Comparative Analysis of Complex Organizations. Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1975.

- Kanter, R.M. Commitment and Social Organization: A Study of Commitment Mechanisms in Utopian Communities. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1968, 33, 499. [CrossRef]

- Al-Madi, F.N.; Assal, H.; Shrafat, F.; Zeglat, D. The Impact of Employee Motivation on Organizational Commitment. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 9, 134–145.

- Altindis, S. Job Motivation and Organizational Commitment Among the Health Professionals: A Questionnaire Survey. Afr. J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 5, 8601.

- Meyer, J.P.; Stanley, D.J.; Herscovitch, L.; Topolnytsky, L. Affective, Continuance, and Normative Commitment to the Organization: A Meta-analysis of Antecedents, Correlates, and Consequences. J. Vocat. Behav. 2002, 61, 20–52. [CrossRef]

- Macmahon, M.J. An Investigation of the Relationship Between Organizational Commitment and Employee Turnover. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 143–156.

- Pi, C.; Chiu, S.; Lin, J. The Influence of Work Stress, Job Satisfaction, and Work Values on Organizational Commitment: An Empirical Study of Airline Employees. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1830–1848.

- Jim, E.L.; Pio, R.J.; Asaloei, S.I.; Leba, S.M.R.; Angelianawati, D.; Werang, B.R. Work-Related Stress, Emotional Exhaustion, Job Satisfaction, and Organizational Commitment of Indonesian Healthcare Workers. Int. J. Relig. 2024, 5, 308–316. [CrossRef]

- Cornforth, C. The Role of Volunteers in Nonprofit Governance: A Critical Review of the Literature. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2012, 41, 644–665.

- Zollo, M.; Aggeri, F.; DeNisi, A.S. The Role of Volunteers in Nonprofit Organizations: A Multilevel Analysis of Antecedents and Consequences. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2016, 45, 494–511.

- Zollo, L.; Faldetta, G.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Ciappei, C. Reciprocity and gift-giving logic in NPOs. J. Manag. Psychol. 2017, 32, 513–526. [CrossRef]

- Van Vuuren, M.; de Jong, M.D.; Seydel, E.R. Commitment with or without a Stick of Paid Work: Comparison of Paid and Unpaid Workers in a Nonprofit Organization. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 2008, 17, 315–326.

- Agoncillo, R.N.L.; Borromeo, R.T. Becoming Selfless: A Grounded Theory of Commitment to Service. Grounded Theory Rev. 2013, 12(2).

- Engelberg, T.; Zakus, D.H.; Skinner, J.L.; Campbell, A. Defining and Measuring Dimensionality and Targets of the Commitment of Sport Volunteers. J. Sport Manag. 2012, 26, 192–205. [CrossRef]

- Juaneda-Ayensa, E.; Emeterio, M.C.S.; González-Menorca, C. Person-Organization Commitment: Bonds of Internal Consumer in the Context of Non-profit Organizations. Front. Psychol. 2017, 8, 1227–1227. [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Darrow, C.; Xu, Y. Retaining volunteer mediators: Comparing predictors of burnout. Confl. Resolut. Q. 2018, 35, 367–381. [CrossRef]

- Kline, L.W.; France, C.J. The Psychology of Ownership. Pedagog. Semin. 1899, 6, 421–470. [CrossRef]

- Pierce, J.L.; Rubenfeld, S.A.; Morgan, S. Employee Ownership: A Conceptual Model of Process and Effects. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 121–144.

- Dawkins, S.; Tian, A.W.; Newman, A.; Martin, A. Psychological ownership: A review and research agenda. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 38, 163–183. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wang, H.; Hui, C.; Lee, C. Psychological Ownership: How Having Control Matters. J. Manag. Stud. 2011, 49, 869–895. [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, I.J.; Rashid, A.G. The Impact of Psychological Ownership at Work on Organizational Commitment, an Exploratory and Analytical Study at the Union Food Industries Company LTD. Sugar and Oil Industry / Babylon Governorate. Seybold Rep. 2022, 17.

- Boonsiritomachai, W.; Sud-On, P.; Sudharatana, Y. The Effect of Psychological Ownership on Organizational Commitment. Kasetsart J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 43, 523–530.

- Renz, F.M.; Posthuma, R. 30 years of psychological ownership theory: a bibliometric review and guide for management scholars. J. Manag. Hist. 2022, 29, 179–204. [CrossRef]

- Ainsworth, J. Feelings of ownership and volunteering: Examining psychological ownership as a volunteering motivation for nonprofit service organisations. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101931. [CrossRef]

- Avey, J.B.; Avolio, B.J.; Crossley, C.D.; Luthans, F. Psychological ownership: theoretical extensions, measurement and relation to work outcomes. J. Organ. Behav. 2009, 30, 173–191. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Hui, Q.-s.; Xi, J. The Revision of Avey’s Psychological Ownership Questionnaire and Relationship with the Related Work Attitudes. Soc. Work Manag. 2012, 12, 31–38.

- Ho, Y.W.; You, J.; Fung, H.H. The moderating role of age in the relationship between volunteering motives and well-being. Eur. J. Ageing 2012, 9, 319–327. [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K. Promotion of Volunteerism among Hong Kong Retirees: An Intervention Study. Public Policy Research Funding Scheme, Hong Kong, 2016.

- Buchanan, B. Government Managers, Business Executives, and Organizational Commitment. Public Adm. Rev. 1974, 339–347.

- Mowday, R.T.; Steers, R.M.; Porter, L.W. The measurement of organizational commitment. J. Vocat. Behav. 1979, 14, 224–247. [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J.P.; Allen, N.J. A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 1991, 1, 61–89. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388.

- Chin, W.W. Commentary: Issues and Opinion on Structural Equation Modeling. Manag. Inf. Syst. Q. 1998, 22, 7–16.

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage: Boston, MA, USA, 2019.

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. PLS-SEM: Indeed a Silver Bullet. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2011, 19, 139–152. [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H.W.; Hau, K.T.; Balla, J.R.; Grayson, D. Is More Ever Too Much? The Number of Indicators per Factor in Confirmatory Factor Analysis. Multivar. Behav. Res. 1998, 33, 181–220. [CrossRef]

- Schober, P.; Boer, C.; Schwarte, L.A. Correlation Coefficients: Appropriate Use and Interpretation. Anesth. Analg. 2018, 126, 1763–1768. [CrossRef]

- Tiffany, A.W.; Schumacker, R.E. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed.; Newgen Publishing: UK, 2022.

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [CrossRef]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Lockwood, C.M.; Williams, J. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivar. Behav. Res. 2004, 39, 99–128. [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.; MacKinnon, D.P. Resampling and Distribution of the Product Methods for Testing Indirect Effects in Complex Models. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J. 2008, 15, 23–51. [CrossRef]

- Briggs, N.E. Estimation of the Standard Error and Confidence Interval of the Indirect Effect in Multiple Mediator Models. Ph.D. Thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA, 2006.

- Lee, J.; Min, J.; Lee, H. The Effect of Organizational Structure on Open Innovation: A Quadratic Equation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 91, 492–501. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).