Submitted:

08 May 2024

Posted:

09 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. AIM

3. Methodology

Determination of pH

Determination of °Brix

Determination of Buffer Capacity

Participants and Oral Examination Procedure

- 0.

- Sound crown: A crown considered to be sound when it doesn’t show evidence of treated or untreated caries. In the absence of positive criteria, a crown with following defects is coded as sound:

- White or chalky spots: When we touch the tooth with probe even it is discoloured or rough spots those aren’t soft

- Stained pits or fissures: in the enamel there isn’t any visual sign of cavities or enamel damage.

- Dark shiny, hard and pitted areas that shows signs of fluorosis.

- Lesions that based on visual examination appear to be due to abrasion.

- 1.

- Decayed Crown: Caries is recorded as present when there was a lesion in pit or fissure wich has an unmistakable cavity. In cases of tooth with a temporary filling a tooth wich is sealed [code 6] will be included in this category. When there is only the root, because the crown has been destroyed by caries is scored as a decayed crown.

- 2.

- Filled crown, with decay: A crown considered filled with decay, when the tooth have one or more permanent restoration but there is also one or more areas that are decayed. Between primary and secondary caries isn’t made any distinction.

- 3.

- Filled Crown, with no decay: When a crown has one or more permanent restoration present but there is no evidence of caries anywhere on the crown.

- 4.

- Missing tooth: It’s used for permanent dentition for the teeth that have been extracted as a result of caries. as a result of caries.

- 5.

- Permanent tooth missing, for different reason: This was used for teeth that considered to be absent for congenitally problems, or that have been extracted due to orthodontic reasons, trauma, any other periodontal disease etc.

- 6.

- Fissure sealant: This code was used for permanent teeth in which on the occlusal surface have been placed a fissure sealant or has been placed a composite material.

- 7.

- Bridge abutment, crown or veneer: This code is used under coronal status and can also be used for crowns.

- 8.

-

Unerupted crown: This code included unerupted permanent teeth without a primary teeth, and for congenitally reasons the tooth is missing or due to traumatic reasons the tooth have been lost.T. Trauma (fracture): A fractured crown is scored when a crown is missing some of its surface.

- 9.

- Not recorded: This classification is used for erupted permanent tooth that for any reason cannot be examined. The following reasons are: severe to moderate hypoplasia, orthodontic bands etc. The surface with dental plaque was evaluated by Quigley and Hein index5 modified6 also findings of bleeding were recorded separately for each of the index teeth (DD 16, 11,26,36,31 and 46). Gingival health status was assessed, data collected by Chi-square test and statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS software.

Statistical Analysis

4. Results

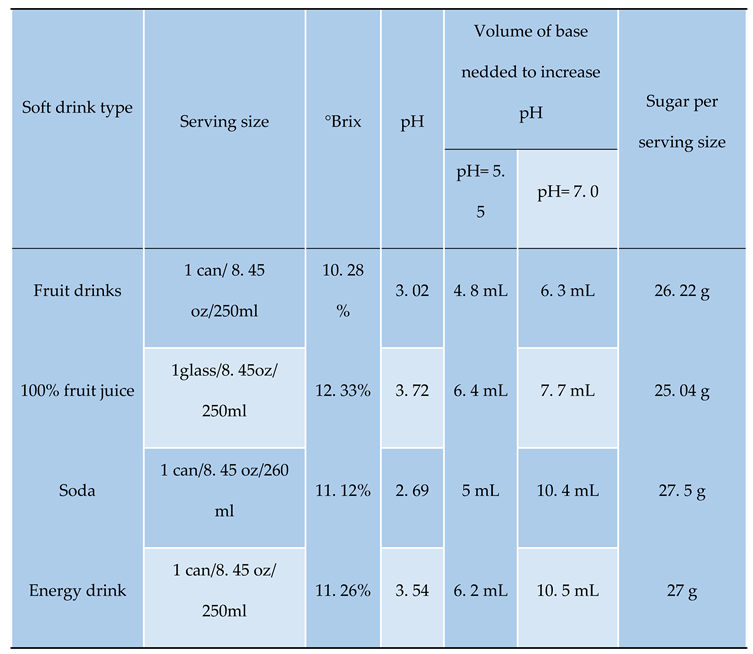

Soft Drinks and Its Physico-Chemical Characteristics

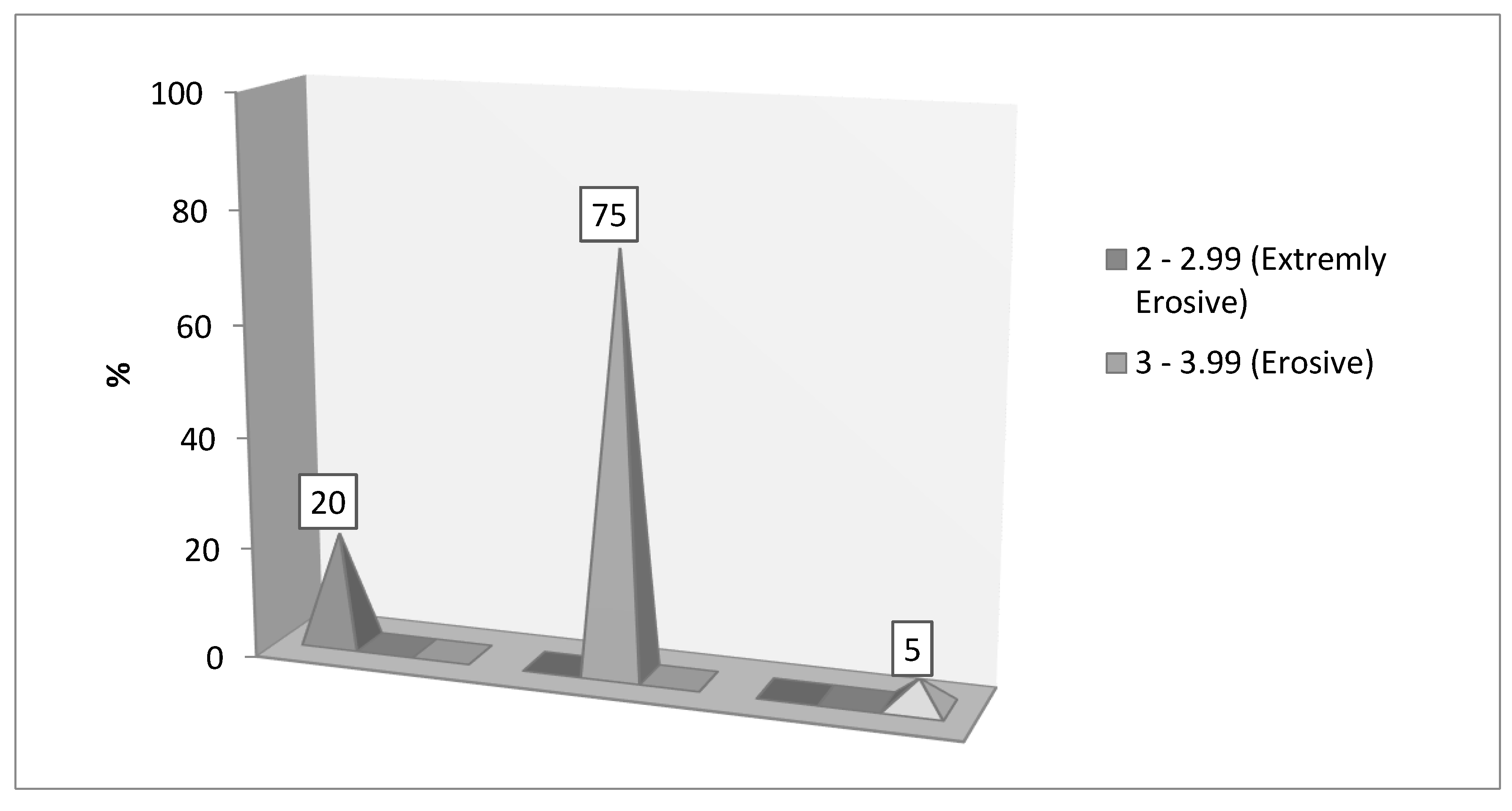

pH Measurements

Brix Measurements

Buffer Capacity Measurements

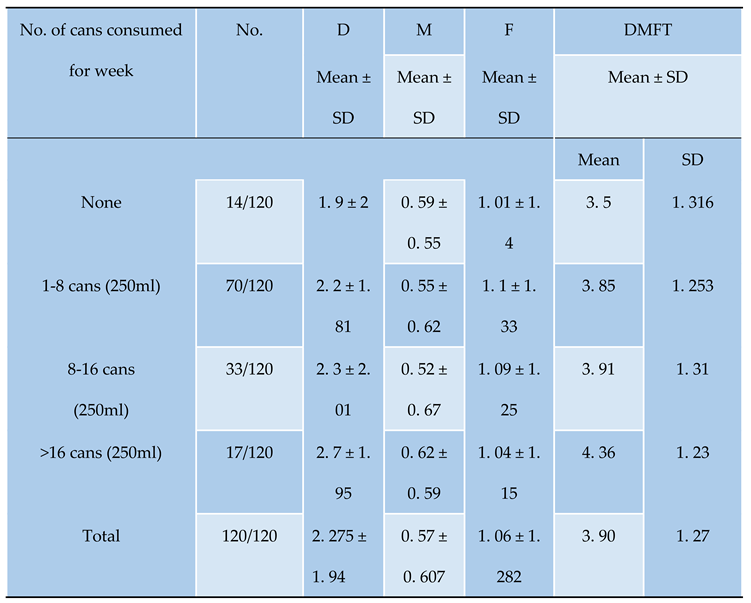

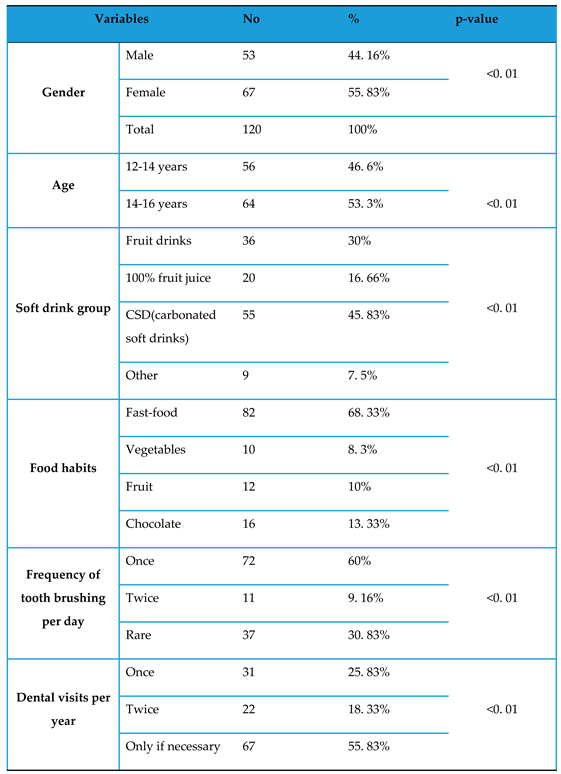

Demographic and Oral Health

Soft Drinks Frequency and Food Habits

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion

References

- Lussi, A.; Schlueter, N.; Rakhmatullina, E.; Ganss, C. Dental Erosion – An Overview with Emphasis on Chemical and Histopathological Aspects. Caries Res. 2011, 45, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kregiel, D. Health Safety of Soft Drinks: Contents, Containers, and Microorganisms. BioMed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harnack, L.; Stang, J.; Story, M. Soft Drink Consumption Among US Children and Adolescents. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1999, 99, 436–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenkin, J.D.; Heller, K.E.; Warren, J.J.; Marshall, T.A. Soft drink consumption and caries risk in children and adolescents. Gen Dent. 2003, 51, 30–6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Tahmassebi, J.; Duggal, M.; Malik-Kotru, G.; Curzon, M. Soft drinks and dental health: A review of the current literature. J. Dent. 2006, 34, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meurman, J.H.; Gate, J.M.T. Pathogenesis and modifying factors of dental erosion. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1996, 104, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Gate, J.M.; Imfeld, T. Dental erosion, summary. European J Oral Sciences 1996, 104, 241–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcântara, P.M.; Barroso, N.F.F.; Botelho, A.M.; Douglas-De-Oliveira, D.W.; Gonçalves, P.F.; Flecha, O.D. Associated factors to cervical dentin hypersensitivity in adults: a transversal study. BMC Oral Heal. 2018, 18, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davari, A.; Ataei, E.; Assarzadeh, H. Dentin Hypersensitivity: Etiology, Diagnosis and Treatment; A Literature Review. J. Dent. 2013, 14, 136–145. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.; Creanor, S.L.; Foye, R.H.; Gilmour, W.H. Buffering capacities of soft drinks: the potential influence on dental erosion. J. Oral Rehabilitation 1999, 26, 923–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, B.M. The potential effects of pH and buffering capacity on dental erosion. Gen Dent. 2007, 55, 527–31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Zwaylif, L.H.; O'Toole, S.; Bernabé, E. Type and timing of dietary acid intake and tooth wear among American adults. J. Public Heal. Dent. 2018, 78, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azeredo, D.R.; Alvarenga, V.; Sant'Ana, A.S.; Srur, A.U.S. An overview of microorganisms and factors contributing for the microbial stability of carbonated soft drinks. Food Res. Int. 2016, 82, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matar, M.; Darwish, S.S.; Salma, S.R. Erosive potential of some beverages on the enamel surface of primary molars. IOSR-JDMS. 2021, 20, 43–6. [Google Scholar]

- Touger-Decker, R.; Van Loveren, C. Sugars and dental caries. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2003, 78, 881S–892S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Touyz, L.Z.; Silove, M. Increased acidity in frozen fruit juices and dental implications. ASDC J Dent Child. 1993, 60, 223–5. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, editor. Oral health surveys: basic methods. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1997. 66 p.

- Mello, T.; Antunes, J.; Waldman, E.; Ramos, E.; Relvas, M.; Barros, H. Prevalence and severity of dental caries in schoolchildren of Porto, Portugal. Community Dent Health. 2008, 25, 119–25. [Google Scholar]

- Punitha, V.C.; Amudhan, A.; Sivaprakasam, P.; Rathanaprabu, V. Role of dietary habits and diet in caries occurrence and severity among urban adolescent school children. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2015, 7 (Suppl. 1), 298–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skinner, J.; Byun, R.; Blinkhorn, A.; Johnson, G. Sugary drink consumption and dental caries in New South Wales teenagers. Aust. Dent. J. 2015, 60, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chau, A.M.; Lo, E.C.; Chu, C.-H. Dental caries and erosion status of 12-year-old Hong Kong children. BMC Public Heal. 2014, 14, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damle, S. The Effect of Consumption of Carbonated Beverages on the Oral Health of Children: A Study in Real Life Situation. 11, 40. [CrossRef]

- Hasheminejad, N.; Mohammadi, T.M.; Mahmoodi, M.R.; Barkam, M.; Shahravan, A. The association between beverage consumption pattern and dental problems in Iranian adolescents: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Heal. 2020, 20, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palacios, C.; Rivas-Tumanyan, S.; Morou-Bermúdez, E.; Colon, A.M.; Torres, R.Y.; Elías-Boneta, A.R. Association between Type, Amount, and Pattern of Carbohydrate Consumption with Dental Caries in 12-Year-Olds in Puerto Rico. Caries Res. 2016, 50, 560–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, A.; Norris, D.F.; Momeni, S.S.; Waldo, B.; Ruby, J.D. The pH of beverages in the United States. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2016, 147, 255–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nassar, M.; Islam, S.; Hasan, N.; Al-Khazraji, A.; Maki, H. Erosive Potential of Various Beverages in the United Arab Emirates: pH Assessment. Dubai Med J. 2023, 6, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, C.; Shahnawaz, K.; P, D.K.; Chowdhury, A.; Gootveld, M.; Lynch, E. Highly acidic pH values of carbonated sweet drinks, fruit juices, mineral waters and unregulated fluoride levels in oral care products and drinks in India: a public health concern. Perspect. Public Heal. 2019, 139, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arhakis, A.; Mavrogiannidou, Z.; Boka, V. An Overview of the Types of Soft Drinks and Their Impact on Oral Health: Review of Literature. World Journal of Dentistry. 2023, 14, 648–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambarakova, V.; Panova, O. Dental Caries Experience among 15-years Old Children in the Southeast Region of the Republic of Macedonia. Oral Health and Dental Management. 2015, 14, 336–73. [Google Scholar]

- Laganà, G.; Abazi, Y.; Beshiri Nastasi, E.; Vinjolli, F.; Fabi, F.; Divizia, M.; et al. Oral health conditions in an Albanian adolescent population: an epidemiological study. BMC Oral Health. 2015, 15, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.A.; El Moshy, S.; Rady, D.; Radwan, I.A.; Abbass, M.M.S.; Al Jawaldeh, A. The effect of unhealthy dietary habits on the incidence of dental caries and overweight/obesity among Egyptian school children (A cross-sectional study). Front. Public Heal. 2022, 10, 953545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenoy, V.U.; Shaikh, S.; Venkatasubramanyam, S.M.; Verma, J.; Chavan, P.; Gawali, S. To evaluate the buffering capacity of various drinks commonly available in India. MGM J. Med Sci. 2020, 7, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferizi, L.; Bimbashi, V.; Kelmendi, J. Dental Caries Prevalence and Oral Health Status among 15-Year- Old Adolescents in Kosovo. Acta Stomatol. Croat. 2022, 56, 42–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.M.; Mani, S.A.; Doss, J.G.; Danaee, M.; Kong, L.Y.L. Pre-schoolers’ tooth brushing behaviour and association with their oral health: a cross sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2021, 21, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqi, F.A.; Khabeer, A.; Moheet, I.A.; Khan, S.Q.; Farooq, I.; ArRejaie, A.S. Prevalence of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth and its relation with tooth brushing habits among schoolchildren in Eastern Saudi Arabia. SMJ. 2015, 36, 737–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mallineni, S.K.; Alassaf, A.; Almulhim, B.; Alghamdi, S. Influence of Tooth Brushing and Previous Dental Visits on Dental Caries Status among Saudi Arabian Children. Children. 2023, 10, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, W.M.; Williams, S.M.; Broadbent, J.M.; Poulton, R.; Locker, D. Long-term Dental Visiting Patterns and Adult Oral Health. J Dent Res. 2010, 89, 307–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).