Submitted:

09 May 2024

Posted:

09 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Korean Medicine Intervention for anxiety

2.4. Outcome Measurement Variables

2.5. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics and Clinical Outcomes in Patients

3.2. Relationships between Anxiety-Relevant Measurement Scales

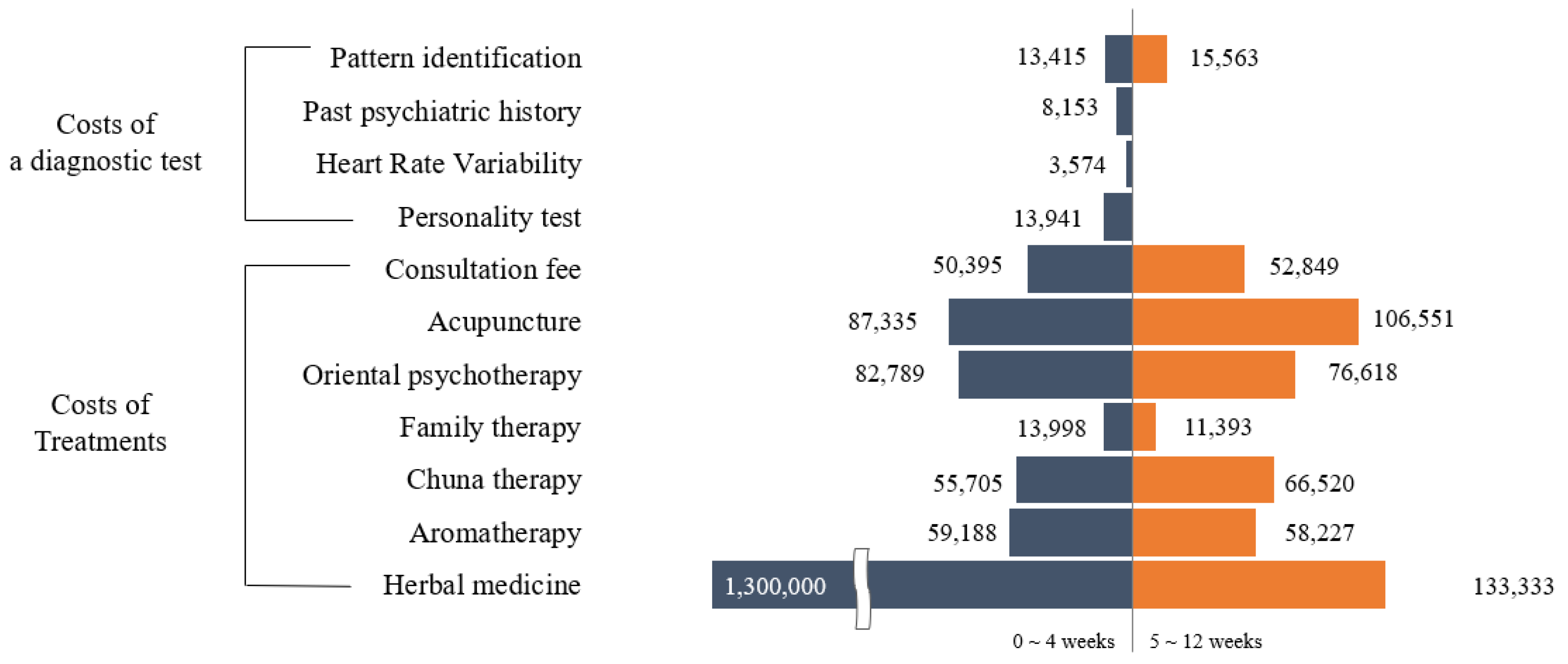

3.3. Costs of Traditional Korean Medicine Treatment for Patients with Anxiety

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV; Washington, DC: 1994; Volume 4.

- Bandelow, B.; Michaelis, S. Epidemiology of anxiety disorders in the 21st century. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015, 17, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepon, J.; Belik, S.L.; Bolton, J.; Sareen, J. The relationship between anxiety disorders and suicide attempts: Findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Depress Anxiety 2010, 27, 791–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry 2022, 9, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dattani S; Rodés-Guirao L; Ritchie H; M, R. Mental Health. Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/mental-health (accessed on May 8).

- Seo, S.I.; Choi, S.Y.; Kim, E.J.; Koo, B.S.; Hyo, W.J.; Lee, G.H.; Kim, G.W. Patterns of Integrative Korean Medicine Practice for Anxiety Disorders: A Survey among Korean Medicine Doctors (KMDs) in Korea. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020, 2020, 3140764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unützer, J.; Klap, R.; Sturm, R.; Young, A.S.; Marmon, T.; Shatkin, J.; Wells, K.B. Mental disorders and the use of alternative medicine: Results from a national survey. Am J Psychiatry 2000, 157, 1851–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Soukup, J.; Davis, R.B.; Foster, D.F.; Wilkey, S.A.; Van Rompay, M.I.; Eisenberg, D.M. The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 2001, 158, 289–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.; Shih, C.C.; Cheng, H.C.; Kwon, S.H.; Kim, H.M.; Lim, B.M. A comparative study of the traditional medicine systems of South Korea and Taiwan: Focus on administration, education and license. Integr Med Res 2021, 10, 100685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.S.; Koo, M.S. Modern psychiatric understanding of the psychopathology of psychosis in oriental medicine. J Korean Neuropsychiatric Assoc 2010, 508–515. [Google Scholar]

- Herman, P.M.; Poindexter, B.L.; Witt, C.M.; Eisenberg, D.M. Are complementary therapies and integrative care cost-effective? A systematic review of economic evaluations. BMJ open 2012, 2, e001046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natioanl Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. Complementary, Alternative, or Integrative Health: What’s In a Name? Available online: https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/complementary-alternative-or-integrative-health-whats-in-a-name (accessed on May 9).

- Leichsenring, F.; Steinert, C.; Rabung, S.; Ioannidis, J.P.A. The efficacy of psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies for mental disorders in adults: An umbrella review and meta-analytic evaluation of recent meta-analyses. World Psychiatry 2022, 21, 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Kang, M.J.; Lim, J.H.; Seong, W.Y. A review study in treatment for anxiety disorder in traditional chinese medicine. J Orient Neuropsychiatry 2012, 23, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenes, G.A. Anxiety, depression, and quality of life in primary care patients. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2007, 9, 437–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Reheiser, E.C. Assessment of emotions: Anxiety, anger, depression, and curiosity. Appl Psychol Health Well Being 2009, 1, 271–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilmer, M.T.; Anderson, K.; Reynolds, M. Correlates of quality of life in anxiety disorders: Review of recent research. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2021, 23, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, G.M. The overlap between anxiety, depression, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Dialogues Clin Neurosci 2015, 17, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deschênes, S.S.; Dugas, M.J.; Fracalanza, K.; Koerner, N. The role of anger in generalized anxiety disorder. Cogn Behav Ther 2012, 41, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, D.M.; Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.C.; Kang, W.C.; Lee, S.R.; Jung, I.C. The comparative clinical study of efficacy of Gamisoyo-San (Jiaweixiaoyaosan) on generalized anxiety disorder according to differently manufactured preparations: Multicenter, randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 158, 11–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.Y.; Yang, N.B.; Huang, F.F.; Ren, S.; Li, Z.J. Effectiveness of acupuncture on anxiety disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Annals of general psychiatry 2021, 20, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marteau, T.M.; Bekker, H. The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State—Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Br J Clin Psychol. 1992, 31, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, A.T.; Epstein, N.; Brown, G.; Steer, R.A. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1988, 56, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spielberger, C.D. State-Trait anger expression inventory. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology 2010, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chon, K.K.; Hahn, D.W.; Lee, C.H.; Spielberger, C.D. Korean adaptation of the state-trait anger expression inventory: Anger and blood pressure. The Korean journal of health psychology 1997, 2, 60–78. [Google Scholar]

- Arnau, R.C.; Meagher, M.W.; Norris, M.P.; Bramson, R. Psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II with primary care medical patients. Health Psychol. 2001, 20, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bastianello, M.R.; Pacico, J.C.; Hutz, C.S. Optimism, self-esteem and personality: Adaptation and validation of the Brazilian version of the Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R). Psico-USF 2014, 19, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H. The relationship between life satisfaction/life satisfaction expectancy and stress/well-being: An application of motivational states theory. The Korean Journal of Health Psychology 2007, 12, 325–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarow, J.P.; LaVange, L.; Woodcock, J. Multidimensional evidence generation and FDA regulatory decision making: Defining and using “real-world” data. JAMA 2017, 318, 703–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ainur, S.; Herawati, L.; Widyawati, M.N. The benefits of holistic therapy for psychological disorders in postpartum mother: A systematic review. STRADA Jurnal Ilmiah Kesehatan 2020, 9, 1708–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentala, S.; Lau, B.H.P.; Aladakatti, R.; Thimmajja, S.G. Effectiveness of holistic group health promotion program on educational stress, anxiety, and depression among adolescent girls–A pilot study. J Family Med Prim Care 2019, 8, 1082–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, B.J. A holistic approach to anxiety and stress. Am J Psychoanal 1976, 36, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papathanasiou, I.; Sklavou, M.; Kourkouta, L. Holistic nursing care: Theories and perspectives. Am J Nurs Sci 2013, 2, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Center for Mental Health. National Mental Health Survey 2021. Available online: https://mhs.ncmh.go.kr/front/en/infographic.do?category=1&%20category_en%20=%20The%20Survey%20of%20Mental%20disorder%20in%20Korea%202021 (accessed on August 8).

- National Institute for Korean Medicine Development. Manual for developing Evidence-based Clinical Practice Guideline of Korean Medicine. Available online: https://nikom.or.kr/board/boardFile/download/24/23541/28224.do (accessed on August 8).

- Yin, C.S.; Ko, S.G. Introduction to the history and current status of evidence-based Korean medicine: A unique integrated system of allopathic and holistic medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2014, 2014, 740515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Pham, D.D. Sasang constitutional medicine as a holistic tailored medicine. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2009, 6, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, R.C.; Wang, P.S. The descriptive epidemiology of commonly occurring mental disorders in the United States. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2008, 29, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunner, D.L. Management of anxiety disorders: The added challenge of comorbidity. Depress Anxiety 2001, 13, 57–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etkin, A.; Schatzberg, A.F. Common abnormalities and disorder-specific compensation during implicit regulation of emotional processing in generalized anxiety and major depressive disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2011, 168, 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, J.S.; Schmidt, N.B. The role of anxiety sensitivity in anger symptomatology: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J Anxiety Disord 2021, 83, 102462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamers, F.; van Oppen, P.; Comijs, H.C.; Smit, J.H.; Spinhoven, P.; van Balkom, A.J.; Nolen, W.A.; Zitman, F.G.; Beekman, A.T.; Penninx, B.W. Comorbidity patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders in a large cohort study: The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA). J Clin Psychiatry 2011, 72, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gould, R.A.; Ball, S.; Kaspi, S.P.; Otto, M.W.; Pollack, M.H.; Shekhar, A.; Fava, M. Prevalence and correlates of anger attacks: A two site study. J Affect Disord 1996, 39, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamani-Benito, O.; Esteban, R.F.C.; Castillo-Blanco, R.; Caycho-Rodriguez, T.; Tito-Betancur, M.; Farfán-Solís, R. Anxiety and depression as predictors of life satisfaction during pre-professional health internships in COVID-19 times: The mediating role of psychological well-being. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Health Insurance Review & Assessment Service. Healthcare bigdata Hub. Available online: https://opendata.hira.or.kr/op/opc/olapHumanResourceStatInfoTab1.do (accessed on May 4).

| Range |

Baseline mean (SD) |

After 4 weeks mean (SD) | Improvement from baseline (%) | p-value | |

| Anxiety | |||||

| STAI X-1# | 20–80 | 59.24 (9.55) | 50.48 (12.67) | 14.6 | <0.001*** |

| STAI X-2# | 20–80 | 57.33 (9.98) | 51.57 (11.77) | 9.6 | <0.001*** |

| BAI# | 0–63 | 28.15 (12.74) | 18.72 (13.47) | 22.5 | <0.001*** |

| Anger | |||||

| STAXI-S# | 10–40 | 16.39 (7.28) | 15.33 (7.43) | 3.5 | 0.135 |

| STAXI-T# | 10–40 | 20.30 (7.22) | 19.48 (6.79) | 2.7 | 0.237 |

| AXI-K-I# | 8–32 | 18.22 (5.29) | 17.01 (5.28) | 5.0 | 0.012*** |

| AXI-K-O# | 8–32 | 14.31 (5.17) | 13.58 (5.48) | 3.0 | 0.047*** |

| AXI-K-C | 8–32 | 21.70 (5.12) | 21.61 (4.78) | -0.4 | 0.817 |

| Depression | |||||

| BDI II # | 0–63 | 25.78 (12.04) | 18.6 (13.8) | 11.4 | <0.001*** |

| Optimism | |||||

| LOT-R | 6–30 | 11.81 (4.04) | 12.63 (3.70) | 3.4 | 0.016*** |

| Satisfaction | |||||

| LSMS | 5–35 | 30.24 (3.97) | 30.25 (4.20) | 0.1 | 0.975 |

| SWLS | 5–35 | 15.31 (5.89) | 15.58 (5.72) | 0.9 | 0.556 |

| LSES | 5–35 | 21.63 (7.15) | 23.48 (7.32) | 6.2 | 0.003*** |

| Quality of life | |||||

| EQ-5D | 0–1 | 0.75 (0.17) | 0.83 (0.14) | 8.4 | <0.001*** |

| EQ-VAS | 0–100 | 49.54 (22.96) | 61.39 (21.11) | 11.9 | <0.001*** |

| Medical expenditure | Quality of life | QALY | ACER (KRW/QALY) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insured | Paid by patients | ΔEQ-5D | ||

| 679,000 | 1,632,000 | 0.10 | 0.0938 | 24,629,000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).