1. Introduction

Socially withdrawn children tend to remove themselves from opportunities for peer interactions and frequently perform solitary behaviors in social contexts [

1]. Although social withdrawal was generally linked to children’s social, emotional, and academic maladjustment [

2], subtypes with different social approach and social avoidance motivations appear to be differentially associated with individuals’ adjustment outcomes [

3,

4]. As a subtype of social withdrawal, unsociability is characterized by low social approach (i.e., the desire to look for social interactions) and low-to-average social avoidance motivations (i.e., the desire to avoid social interactions) [

5,

6], which increases the risk of children’s socio-emotional malfunctioning in social situations [

3,

4]. However, researchers also have found that unsociability does not appear to be directly linked to psychological maladjustment in Western cultures [

7,

8].

Although there are common associations between social withdrawal and maladjustment, cultural values play an important role in determining the meanings and implications of different types of social withdrawal [

9]. Therefore, the associations between unsociability and peer problems are suggested to be largely shaped by socio-cultural contexts [

10,

11]. The large-scale social changes in China in last decades has led to the co-junction of characteristics from different values in Chinese context, providing a unique view to understand the role of culture on unsociable children's peer problems [

12]. In contrast to findings from Western societies [

13], a series of empirical studies have manifested the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese context. For example, unsociable Chinese children experience increased peer problems [

14,

15]. However, there is a lack of systematic review to understand the impact of unsociability on peer problems in China. Accordingly, the aim of the present study was to conduct a meta-analysis of unsociability and peer problems in Chinese context.

1.1. Conceptualizations of Unsociability

Unsociability refers to the social disinterest and non-fearful preference for solitary activities, being indicative of a motivation to be alone that reflects the positive appeal that solitude and solitary activities hold for individuals [

13]. It underscores the important notion that unsociable individuals have an intrinsic motivation for spending alone [

16]. Specifically, unsociable children perform withdrawn behaviors due to their preference and enjoyment of solitary activities [

13,

17]. The conceptualization of unsociability still lacks lucidity in the extant literature [

13]. A number of terms have been conducted overlapping with unsociability, including preference for solitude [

18,

19], affinity for solitude [

20], social disinterest [

21], solitropic orientation [

22], and affinity for aloneness [

23,

24]. The above terms belong to various aspects of solitude [

25], and all sharing a common underlying theme of a non-fearful preference for spending time alone [

13]. Since the current study focused on the motivational aspects of solitude, the above terms were all considered as conceptually equivalent and are used to discuss the associations between unsociability and peer problems.

1.2. Associations between Unsociability and Peer Problems in China

Peer group plays an important and unique role in children’s social, emotional, cognitive, and moral development [

26]. Children involved in infrequent social interactions may ‘miss out’ on those benefits from peers, possibly leading to difficulties in social adjustment [

2,

27]. There are several indices of peer problems reflecting different processes of negative peer relationships, including peer rejection and peer victimization [

28,

29]. Peer rejection is constructed as encompassing peer behaviors to thwart one’s overtures [

29], whereas peer victimization can be defined as being the target of intended peers’ hurtful behaviors [

28]. A line of work has found that peer problems in childhood and adolescence may have strong associations with internalizing problems, which may turn out to be the risk factors of their socio-emotional adjustment in emerging adulthood [

15,

30,

31,

32]. For example, Xiao and colleagues also found that unsociability was negatively associated with subsequent loneliness through the mediating effect of peer rejection [

14].

The meaning and adaptive value of certain social behavior may vary across cultural contexts [

33], unsociability is viewed as a relatively benign form of solitary behavior in Western societies [

7,

8,

17,

27,

34,

35,

36]. Solitary behaviors may reflect a personal choice, self-assertiveness, and autonomous action, which are conformed to their self-oriented or individualistic culture values [

37]. In addition, unsociable children and adolescents show social disinterest and non-fearful preference for solitude [

3]. Therefore, spending time alone may provide more opportunities to improve self-identification and self-construction [

23] and attenuate the development of peer difficulties and help those children and adolescents to be adaptive [

13]. Unlike the emphasis on expressing personal choice in self-oriented culture, Chinese culture is a typical group-oriented society that encourage social interdependence and group harmony [

38,

39,

40]. Chinese children are encouraged to participate in group activities and contribute to collective wellbeing and the disengaging behaviors from peer groups in unsociable children and adolescents may be considered as anti-group, selfish, and abnormal [

11]. Indeed, children who are not interested in group interaction and prefer to spend time alone are often viewed as deviant and criticized by adults and disliked by peers [

38], which in turn may contribute to the development of adjustment difficulties [

41].

It should be noted that empirical studies found inconsistent evidence on the associations between unsociability and peer problems across different cultural contexts. A number of studies in Western societies indicated that unsociability was not necessarily associated with peer problems [

7,

8,

17,

27,

34,

35,

36]. However, unsociability in childhood and adolescence was found to be significantly associated with peer problems in Chinese context, both concurrently and longitudinally [

41,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46]. A cross-cultural study directly compared the implications of unsociability among Chinese and Canadian children and adolescents, and revealed a stronger association between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children, as compared to their Canadian counterparts [

47].

2. The Present Study

Although previous studies found the positive associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese culture [

48,

49,

50], the strength and direction of these associations were mixed and no study has synthesized the previous findings to examine the associations in Chinese sample. Ran and colleagues conducted a meta-analysis to assess the associations between three subtypes of social withdrawal and peer problems in Chinese and North American youth to detect the mixed results in Western countries and China [

51]. Despite the significant and positive associations suggesting social withdrawal was a risk factor for social adjustment in both Chinese and North American youth, this meta-analysis neglected the motivational and cultural specificity of unsociability. Considering the low approach motivation, unsociability and social avoidance fall under the broader construct of preference for solitude, but it ignores the intrinsic motivation of unsociability [

6]. Therefore, the previous meta-analysis on the associations between social withdrawal and peer problems is not able to understand how unsociability is related to peer problems in Chinese culture further. Accordingly, the present study aimed to address this issue by performing a meta-analysis of studies involving unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents. As aforementioned, considering the positive associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents, we hypothesize that unsociability would be significantly and positively associated with peer problems, that is, children with higher level of unsociability would have more peer problems.

Moreover, whether there are moderating factors among the associations between unsociability and peer problems were also examined in the present study. Preference for solitude has become increasingly adaptive and provides a context for more independence and behavioral autonomy from childhood to adolescence [

13], thus age group may buffer the negative effect of unsociability on peer problems. In addition, the progress of urbanization in China in the past four decades has narrowed the gap between people in urban and suburban areas and they have to face the changes of living conditions and challenge of values, which may lead them to be more maladjustment [

41]. It should be also noted that multiple informants were used to measure unsociability and peer problems, including self-reports, peer-nominations, parent-ratings, and teacher-ratings. However, most of the previous studies rely on one informant solely, which may influence the strength of the associations between unsociability and peer problems. Therefore, these potential moderators (e.g., age group, living areas, informants) should be examined in the present meta-analysis. It is expected that the associations between unsociability and peer problems would be stronger for children and people living in suburban area, and when unsociability and peer problems were measured by themselves.

3. Method

3.1. Study Selection

To retrieve relevant research on the associations between unsociability and peer problems interested in the present study, a systematic search was performed at the initial stage of study selection in various electronic databases: EBSCO, Sage, Science Direct, Springer Online Journals, Willey, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), China Master’s Theses Full-text Database (CMFD), China Doctoral Dissertations Full-text Database (CDFD). Then, we manually checked the reference lists of selected studies and review articles to reduce the likelihood of missing relevant studies.

To identify publications according to the following criteria, the screening process was underdone, and identified papers were initially examined by two authors. The third independent author conducted a final decision and the coding process. Considering unsociability and solitude share common construct of non-fearful preference for spending time alone, we searched the published articles on the electronic databases mentioned above with the following combination of keywords in Chinese and English: (“social withdrawal” OR “unsociability” OR “solitude” OR “preference for solitude”) AND (“peer problems” OR “peer rejection” OR “peer victimization”).

All studies were included in the present meta-analysis if fulfilling the following criteria: (a) the study design was quantitative and empirical; review articles, qualitative studies, and case studies were excluded; (b) the studies investigated the associations between unsociability and peer problems; (c) the studies were written in English and Chinese (i.e., team members are fluent in both languages); (d) the studies included participants who were identified as school-aged children and adolescents with mean age between 0 and 18 years from China; and (e) the studies reported statistical information to obtain or calculate at least one effect size (e.g., Pearson’s r).

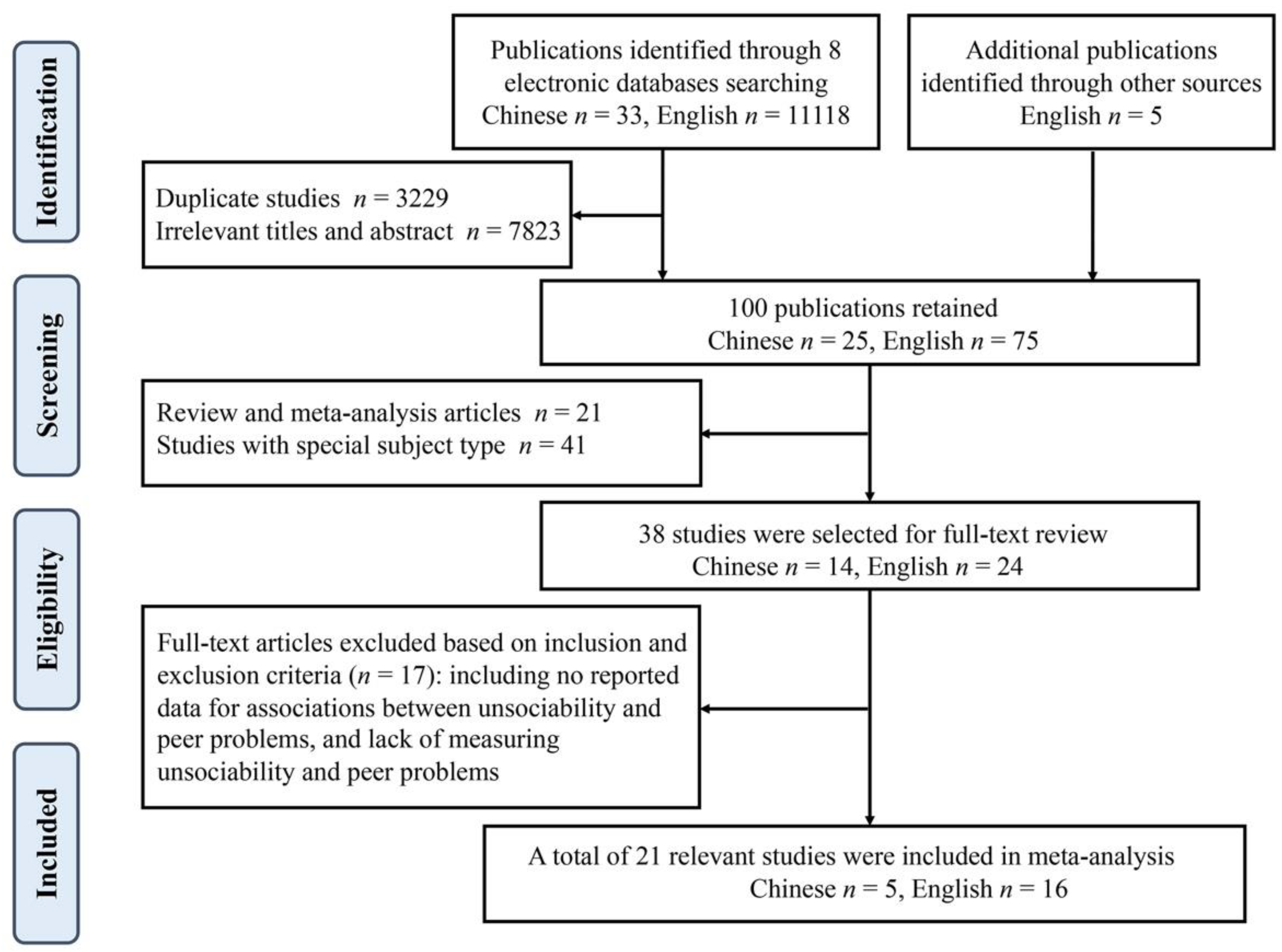

Figure 1 shows a flow chart of the search procedure. A total of 21 relevant publications were included in the final meta-analysis.

3.2. Coding of Variables

To synthesize the results from primary studies, each study was coded and extracted based on the following characteristics, including 43 effect sizes (see

Table 1): (a) first author and year of publication; (b) number of participants (i.e.,

N); (c) study design (i.e., cross-sectional or longitudinal); (d) gender (i.e., percentage of boys); (e) age group (i.e., children who are in kindergarten and elementary school or adolescents who are in middle and secondary school); (f) areas where participants live (i.e., urban, suburban, or rural regions with different industrialization and population size); (g) informants of unsociability (i.e., self-reports, peer nominations, or parent ratings); (h) informants of peer problems (i.e., self-reports, peer nominations, or teacher ratings); (i) effect size (i.e., Pearson’s r). If the studies have more than one sample, effect sizes for each sample were included in the present meta-analysis. If the studies reported effect sizes for different subgroups, only effect sizes reported for the subgroups were included to reduce the likelihood of redundancy. If the studies reported multiple outcomes (such as peer rejection and peer victimization), or assessed unsociability and peer problems by multiple measures, all eligible effect sizes were included and coded. If different studies were reported on duplicate samples, only one study was included and coded. Three authors coded selected studies independently, and all discrepancies between the coders were reviewed again, after which errors were corrected by consensus.

3.3. Statistical Analysis

The correlation coefficient (r) was chosen as the index of effect size in the present meta-analysis. In cases some studies did not report the correlation coefficients, the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software would compute Pearson’s r using the available statistical data reported in each study. We first estimated the overall associations between unsociability and peer problems. The positive r value indicates that a high level of unsociability is associated with a high level of peer problems. According to Cohen’s guidelines (Cohen, 1977), the magnitude of the correlation was interpreted as small (0.10), medium (0.30), or large (0.50). Then, we conducted bivariate moderation analyses by using random-effects models to examine the potential moderators on the associations between unsociability and peer problems.

Publication bias is a common concern for meta-analytic research [

52], which means studies reporting significant findings are more likely to be published than those reporting non-significant findings. In order to correctly evaluate the publication bias, we visually inspected the funnel plots of effect sizes, and conducted Egger’s regression tests and the Begg and Mazumdar rank correlation test [

53,

54]. The significant p-value in both tests indicates that the publication bias may be detected. Additionally, Fail Safe N was calculated to the number of unpublished studies needed to change the effect size to non-significant [

55]. All meta-analytic calculations were conducted using Version 3.0 of Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software [

56].

4. Results

4.1. Heterogeneity Analyses and Publication Bias

A total of 21 published articles met the inclusion criteria, including 43 effect sizes (i.e., total

k = 43) among 12,696 children and adolescents (i.e., total

N = 12696). The authors, publication years, sample sizes, and effect sizes of these studies are presented in

Table 1, along with other important study characteristics (i.e., percentage of boys, living areas, age group, study design, informants). According to Higgins and Thompson, the values of I2 around 25%, 50%, and 75% can be interpreted as low, medium, and high heterogeneity, respectively [

57]. Thus, a heterogeneity analysis indicated a significant and high degree of heterogeneity with 96.98% of the observed variability attributable to systematic between-study differences (

I2 = 96.98%), and the hypothesis that the effect was estimated the same underlying population value could be rejected (

Q (

df = 42) = 1391.52,

p < 0.001), which further suggested our dataset should be analyzed through random-effects models.

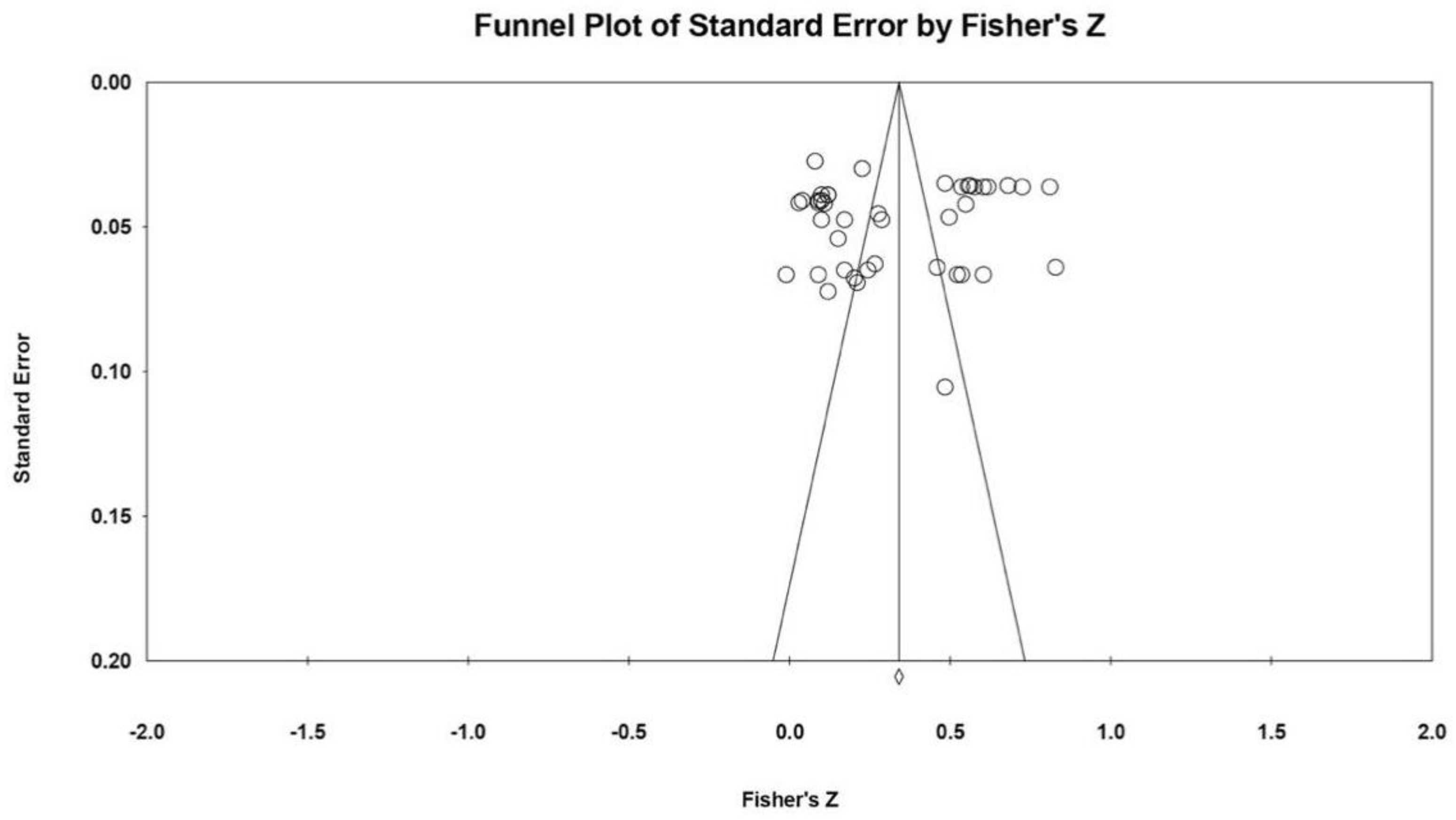

In order to assess whether there was publication bias, the visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed an absence of publication bias (see

Figure 2). In addition, the regression coefficient of Egger’s test (

b = -1.97,

SE = 3.36, 95% CI = [-8.76, 4.81],

t(41) = 0.59,

p = 0.560) and the rank correlation coefficient of Begg’s test (

Z = 0.36,

p = 0.722) were non-significant, and the Fail Safe N test showed that 26,233 additional studies of the associations between unsociability and peer problems would be required to change the significant overall effect size in the present meta-analysis, which was larger than the 5k+10 limit [

55]. Thus, there was no statistically significant publication bias in the selected studies.

4.2. Overall Effect Sizes

The overall random effects estimate showed that the correlations between unsociability and peer problems were r = 0.32, 95% CI = [0.248, 0.384], p < 0.001. Thus, among Chinese children and adolescents, unsociability was positively and moderately associated with their peer problems.

4.3. Moderator Analysis

The results of categorical moderator analysis were present in

Table 2. Results indicated a significant moderating effect of the living areas (urban vs. suburban vs. rural),

Q(

df = 2) = 30.13,

p < 0.001. Specifically, the associations between unsociability and peer problems were larger in suburban samples (

r = 0.50) than in urban (

r = 0.23) and in rural (

r = 0.46) samples. Also, informants of unsociability,

Q(

df = 2) = 123.77,

p < 0.001, and informants of peer problems,

Q(

df = 2) = 13.48,

p = 0.001, moderated the associations between unsociability and peer problems significantly. Specifically, the effect size of the associations was larger when unsociability was measured via peer nominations (

r = 0.51) than via self-reports (r = 0.14) and parent ratings (

r = 0.23). In addition, the effect size of the associations was larger when peer problems were measured via self-reports (

r = 0.39) than via peer nominations (

r = 0.34) and teacher ratings (

r = 0.17). Study design and age group did not significantly moderate the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese sample. Moreover, meta-regression analysis showed that the percentage of boys was a trending significant moderator of the effect size,

b = 0.004,

SE = 0.002, 95% CI = [-0.0007, -0.0088],

Z = 1.67,

p = 0.096.

5. Discussion

The present study conducted a meta-analysis to systematically examine the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents. Overall, unsociability was found to be positively and moderately associated with peer problems in Chinese culture. In addition, there were significant moderating effects of living areas, informants of unsociability, and informants of peer problems among the associations, with stronger correlation coefficients in the subgroup of participants living in suburban areas, unsociability reported by peers, and peer problems reported by self.

5.1. Overall Associations between Unsociability and Peer Problems in Chinese Culture

The present meta-analysis found significant and positive associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents, which is consistent with previous empirical findings in Chinese culture [

44,

46,

48,

49,

50,

58]. Compared to the cross-cultural meta-analysis regarding the associations between social withdrawal and peer problems [

51], the strength of the correlation coefficient was higher in the present study. This further reflects the motivational and cultural specificity of unsociability, especially in Chinese culture. Although unsociability is conceptualized as the combination of low social approach motivations and low social avoidance motivations at the same time [

5], and the preference and enjoyment of solitary activities may exert positive influence on peer difficulties during adolescence [

13], traditional Chinese culture that emphasizing interdependence and social affiliation may still exacerbate the maladaptive value caused by unsociability [

38].

Especially, the positive associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese sample suggested that unsociable children may suffer adverse peer reactions and social difficulties in social interactions. This suggested that dropping out of social activities for a long time may give rise to social exclusion by peers [

59]. From the perspective of cultural values, spending time alone violates the conventions of interdependence and social harmony and leads to more negative peer reactions [

38]. The high sensitivity to interpersonal relationships within the group makes unsociable behaviors as anti-collective, selfish, and deviant [

38]. Thus, in Chinese culture, unsociable children and adolescents are usually faced with more peer problems.

5.2. Moderators in the Associations between Unsociability and Peer Problems

To further explore the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese culture, we conducted a series of moderation analysis to examine the moderating effect of study design, age group, gender, living areas, and informants of unsociability and peer problems. Inconsistent with our hypotheses, no significant moderating effects of age group and gender were found. Some researchers speculated that peer pressure would be weakened from childhood to adolescence and solitude would be viewed as more positive and normative by adolescents [

13,

20,

37]. However, in comparison to internalizing problems, peer problems seem to be a more direct negative outcome influenced by unsociability in Chinese culture. It has brought an extensive influence on the positive associations between unsociability and peer problems among Chinese children and adolescents, that is, both unsociable children and adolescents tend to have more peer problems. Moreover, the previous meta-analysis found the moderating effect of gender in the associations between social withdrawal and peer problems, which implied social withdrawal was more harmful in Chinese boys than in girls [

51]. Although no significant moderating effect of gender was found in the present meta-analysis, there is a trend toward stronger associations between unsociability and peer problems among Chinese boys. These results indicated less likelihood of tolerance for unsociable boys [

12], as unsociability may be regarded as violating gender norms of male social assertion and dominance [

45,

48].

A notable finding in the present meta-analysis was that the living areas moderated the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese culture. Specifically, the correlation coefficient was stronger among those who live in suburban areas than in urban and rural areas. In the past several decades, there have been various socio-cultural changes influencing human behaviors and values, along with the globalization process, which has effects on Chinese culture and psychology as well [

60]. When the financial and business center in urban areas started to be expanded into suburban areas, people living in suburban areas have been exposed to new cultural values. The cultural and living gap between urban and suburban areas create more challenges for unsociable children and adolescents to adapt for the new cultural values, which may make them more vulnerable to maintain peer relationships in the process of urbanization [

41].

In addition, we found that the informants of unsociability and peer problems significantly moderated the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents. The correlation coefficient was higher when unsociability was measured via peer nominations and peer problems were measured via self-reports. Generally, unsociability was measured by the Revised Class Play [

61,

62], which supplies an “inside perspective” to report one’s engaging in peer interactions from the perspective of peers themselves [

63]. This finding revealed that there is a higher likelihood of rejection or victimization when peers consider their classmates to be more unsociable, because they may be particularly regarded as failure to meet social expectations for group affiliation in the Chinese context. Self-reported peer problems were measured with different scales, such as the Pathways Project [

64], and the multidimensional peer-victimization scale [

65]. Self-reports have direct access to their subjective experience of being rejected, victimized, and excluded by peers and avoid bias from other possible informants. The results showed that children and adolescents who reported more experiences of peer problems had a higher level of unsociability, as the negative peer relationship may keep them from being involved in social interactions.

5.3. Limitations and Future Directions

The present meta-analysis systematically examined the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents, and further explored the potential moderators among these associations. However, the findings should be interpreted with some limitations. First, the present study is unable to comprehend and elucidate the causal relationships between unsociability and peer problems. With increasing studies measuring unsociability and peer problems via longitudinal design, future meta-analysis could gain a more thorough understanding of the associations. Second, although attention has been paid to the moderating effects of various informants of unsociability and peer problems, different measurements of these variables were not examined as the moderator in this meta-analysis, as the number of the studies that used various measurements were relatively limited and unbalanced. Future studies could examine whether the measurements of unsociability and peer problems moderate the associations between them. Third, we found high heterogeneity of the effect sizes, suggesting there were other potential factors need to be tested. Future meta-analysis could find more related empirical studies to enlarge the number of effect sizes, and consider more moderators (e.g., children’s personality, socioeconomic status, parenting style) to explore the psychological mechanisms of the associations between unsociability and peer problems. Finally, the majority of existing findings have utilized questionnaires to examine the associations and its potential psychological processes [

44,

48,

49,

50,

58]. However, some studies have tried to examine social withdrawal with neural techniques. For example, Deng and colleagues discussed the links between social avoidance (i.e., another subtype of social withdrawal) and frontal alpha asymmetry when processing emotional facial stimuli, providing cognitive neuroscience evidence for socially withdrawn individuals [

66]. Future meta-analysis could focus on studies of unsociability and peer problems with neuroimaging techniques (e.g., EEG, fMRI, fNIRS) to identify the common and unique neural mechanisms across different studies.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, the present meta-analysis summarizes the existing evidence from 21 publications examining the associations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children and adolescents. In general, unsociability was moderately and positively associated with peer problems. Hence, Chinese unsociable children and adolescents are particularly at risk of experiencing peer problems (e.g., peer rejection, peer victimization, peer exclusion) during peer interactions. Moreover, the strength of the associations was moderated by living areas, informants of unsociability and peer problems in Chinese culture. In particular, the associations between unsociability and peer problems were stronger among participants living in suburban areas, unsociability measured by peer nominations, and peer problems measured by self-reports. Findings indicate unique differences in the pattern of the associations between unsociability and problems, and provide a more nuanced understanding of how living areas and informants influence adjustment outcomes at different conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Ding. X. and Zheng. H.; methodology, Hu. N. and Zhang. W.; software, Zhang. W.; validation, Haidabieke. A., Wang. J. and Ding. X.; formal analysis, Hu. N. and Zhang. W.; investigation, Haidabieke. A. and Wang. J.; resources, Ding. X.; data curation, Zhang. W.; writing—original draft preparation, Hu. N. and Zhang. W.; writing—review and editing, Ding. X., Zheng. H. and Zhou. N.; supervision, Ding. X.; project administration, Ding. X. and Zheng. H.; funding acquisition, Ding. X. and Zheng. H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32000756); The Changning District Health of Medical Specialty (20232005); The Medical Master's and Doctoral Innovation Talent Base Project of Changning District (RCJD2022S07); Shanghai Normal University Youth Interdisciplinary Innovation Team Cultivation Project (310-AW0203-23-005407).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Rubin, K. H., & Chronis, T. A. Perspectives on social withdrawal in childhood: Past,present, and prospects. Child Development Perspectives 2021, 15(3), 160–167. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K. H., Coplan, R. J., & Bowker, J. C. Social withdrawal in childhood. Annual Review of Psychology 2009, 60(1), 141–171. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Armer, M. A “multitude” of solitude: A closer look at social withdrawal and nonsocial play in early childhood. Child Development Perspectives 2007, 1(1), 26–32. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R. J.; Ooi, L. L.; Nocita, G. When one is company and two is a crowd: Why some children prefer solitude. Child Development Perspectives 2015, 9(3), 133–137. [CrossRef]

- Asendorpf, J. B. Beyond social withdrawal: Shyness, unsociability, and peer avoidance. Human Development 1990, 33, 250–259. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Rubin, K., Laursen, B., Booth-LaForce, C., & Rose-Krasnor, L. Preference-for-solitude and adjustment difficulties in early and late adolescence. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2013, 42(6), 834–842. [CrossRef]

- Bowker, J. C.; Raja, R. Social withdrawal subtypes during early adolescence in India. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2011, 39, 201–212. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Rose-Krasnor, L.; Weeks, M.; Kingsbury, A.; Kingsbury, M.; Bullock, A. Alone is a crowd: Social motivations, social withdrawal, and socioemotional functioning in later childhood. Developmental Psychology 2013, 49(5), 861–875. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; French, D.C.; Schneider, B.H. Culture and peer relationships. In Peer relationships in cultural context; Chen, X., French, D.C., Schneider, B.H., Eds.; Cambridge University Press, 2006; pp. 154–196.

- Bowker, J. C.; Sette, S.; Ooi, L. L.; Bayram-Ozdemir, S.; Braathu, N.; Bølstad, E.; Castillo, K. N.; Dogan, A.; Greco, C.; Kamble, S.; Kim, H. K.; Kim, Y.; Liu, J.; Oh, W.; Rapee, R. M.; Wong, Q. J. J.; Xiao, B.; Zuffianò, A.; Coplan, R. J. Cross-cultural measurement of social withdrawal motivations across 10 countries using multiple-group factor analysis alignment. International Journal of Behavioral Development 2023, 47, 190–198. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S., Liu, M., Chen, X., Li, D., Liu, J., & Liu, S. Unsociability and psychological and school adjustment in Chinese children: The moderating effects of peer group cultural orientations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2023, 54(2), 283–302. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.B.; Santo, J.B. The relationships between shyness and unsociability and peer difficulties: The moderating role of insecure attachment. International Journal of Behavioral Development 2016, 40(4), 346–358. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R. J.; Ooi, L. L.; Baldwin, D. Does it matter when we want to be alone? Exploring developmental timing effects in the implications of unsociability. New Ideas in Psychology 2019, 53, 47–57. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B., Bullock, A., Liu, J., & Coplan, R. Unsociability, peer rejection, and loneliness in Chinese early adolescents: Testing a cross-lagged model. The Journal of Early Adolescence 2021, 41(6), 865–885. [CrossRef]

- Yip, V. T., Ang, R. P., Ooi, Y. P., Fung, D. S. S., Mehrotra, K., Sung, M., & Lim, C. G. The association between attention problems and internalizing and externalizing problems: The mediating role of peer problems. Child & Youth Care Forum 2013, 42(6), 571–584. [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T. T., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 2018, 44(1), 92–106. [CrossRef]

- Coplan, R.J.; Prakash, K.; O’Neil, K.; Armer, M. Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Developmental Psychology 2004, 40(2), 244–258. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. M. Preference-for-solitude and depressive symptoms in Chinese adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences 2016, 100, 151–156. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, K., Coplan, R. J., Teng, Z., Liang, L., Chen, X., & Bian, Y. How does interparental conflict affect adolescent preference-for-solitude? Depressive symptoms as mediator at between- and within-person levels. Journal of Family Psychology 2023, 37(2), 173–182. [CrossRef]

- Hu, N., Xu, G., Chen, X., Yuan, M., Liu, J., Coplan, R. J., Li, D., & Chen, X. A parallel latent growth model of affinity for solitude and depressive symptoms among Chinese early adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 2022, 51(5), 904–914. [CrossRef]

- Kopala-Sibley, D. C., & Klein, D. N. Distinguishing types of social withdrawal in children: Internalizing and externalizing outcomes of conflicted shyness versus social disinterest across childhood. Journal of Research in Personality 2017, 67, 27–35. [CrossRef]

- Leary, M. R., Herbst, K. C., & McCrary, F. Finding pleasure in solitary activities: Desire for aloneness or disinterest in social contact? Personality and Individual Differences 2003, 35(1), 59–68. [CrossRef]

- Goossens, L. Affinity for aloneness in adolescence and preference for solitude in childhood: Linking two research traditions. In R. J. Coplan & J. C. Bowker (Eds.), The handbook of solitude: Psychological perspectives on social isolation, social withdrawal, and being alone. Wiley Blackwell 2014, pp. 150–166.

- Daly, O.; Willoughby, T. A longitudinal person-centered examination of affinity for aloneness among children and adolescents. Child Development 2020, 91(6), 2001–2018. [CrossRef]

- Borg, M. E.; Willoughby, T. A latent class examination of affinity for aloneness in late adolescence and emerging adulthood. Social Development 2022, 31, 587–602. [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K. H.; Bukowski, W. M.; Bowker, J. C. Children in peer groups. In Bornstein, M. H.; Leventhal, T.; Lerner, R. M. (Eds.) Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Ecological settings and processes; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: 2015; pp. 175–222.

- Coplan, R.J.; Weeks, M. Unsociability in middle childhood: Conceptualization, assessment, and associations with socioemotional functioning. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly: Journal of Developmental Psychology 2010, 56(2), 105–130. https://doi.org/www.jstor.org/stable/23098037.

- Adams, R. E.; Santo, J. B.; Bukowski, W. M. The presence of a best friend buffers the effects of negative experiences. Developmental Psychology 2011, 47, 1786–1791. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C. J., Kim-Spoon, J., & Deater-Deckard, K. Linking executive function and peer problems from early childhood through middle adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2016, 44(1), 31–42. [CrossRef]

- Bowes, L.; Joinson, C.; Wolke, D.; Lewis, G. Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: Prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016, 50, 176–183. [CrossRef]

- Lorijn, S. J., Engels, M. C., Huisman, M., & Veenstra, R. Long-term effects of acceptance and rejection by parents and peers on educational attainment: A study from pre-adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Youth & Adolescence 2022, 51(3), 540–555. [CrossRef]

- Stapinski, L. A., Bowes, L., Wolke, D., Pearson, R. M., Mahedy, L., Button, K. S., Lewis, G., & Araya, R. Peer victimization during adolescence and risk for anxiety disorders in adulthood: A prospective cohort study. Depression & Anxiety (1091-4269) 2014, 31(7), 574–582. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Culture, temperament, and social and psychological adjustment. Developmental Review 2018, 50(Part A), 42–53. [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G. W., Kochenderfer, L. B., Eggum, N. D., Kochel, K. P., & McConnell, E. M. Characterizing and comparing the friendships of anxious-solitary and unsociable preadolescents. Child Development 2011, 82(5), 1434–1453. [CrossRef]

- Nelson, L. J. Going it alone: Comparing subtypes of withdrawal on indices of adjustment and maladjustment in emerging adulthood. Social Development 2013, 22(3), 522–538. [CrossRef]

- Sette, S., Zava, F., Baumgartner, E., Baiocco, R., & Coplan, R. Shyness, unsociability, and socio-emotional functioning at preschool: The protective role of peer acceptance. Journal of Child & Family Studies 2017, 26(4), 1196–1205. [CrossRef]

- Wood, K. R., Coplan, R. J., Hipson, W. E., & Bowker, J. C. Normative beliefs about social withdrawal in adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2022, 32(1), 372–381. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X. Culture and shyness in childhood and adolescence. New Ideas in Psychology 2019, 53, 58–66. [CrossRef]

- Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin 2002, 128(1), 3–72. [CrossRef]

- Tamis, L. C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. Parents’ goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development 2008, 17(1), 183–209. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Chen, X., Zhou, Y., Li, D., Fu, R., & Coplan, R. J. Relations of shyness–sensitivity and unsociability with adjustment in middle childhood and early adolescence in suburban Chinese children. International Journal of Behavioral Development 2017, 41(6), 681–687. [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A.; Xiao, B.; Xu, G.; Liu, J.; Coplan, R.; Chen, X. Unsociability, peer relations, and psychological maladjustment among children: A moderated-mediated model. Social Development 2020, 29, 1014–1030. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Weeks, M.; Liu, J.; Sang, B.; Zhou, Y. Relations between unsociability and peer problems in Chinese children: Moderating effect of behavioural control. Infant and Child Development 2015, 24(1), 94–103. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Chen, X.; Fu, R.; Li, D.; Liu, J. Relations of shyness and unsociability with adjustment in migrant and non-migrant children in urban China. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2020, 48(2), 289–300. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Coplan, R. J., Chen, X., Li, D., Ding, X., & Zhou, Y. Unsociability and shyness in Chinese children: Concurrent and predictive relations with indices of adjustment. Social Development 2014, 23(1), 119–136. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B., Bullock, A., Liu, J., & Coplan, R. J. The longitudinal links between marital conflict and Chinese children’s internalizing problems in mainland China: Mediating role of maternal parenting styles. Family Process 2022, 61(4), 1749–1766. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., Chen, X., Coplan, R. J., Ding, X., Zarbatany, L., & Ellis, W. Shyness and unsociability and their relations with adjustment in Chinese and Canadian children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2015, 46(3), 371–386. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, W.; Ooi, L. L.; Coplan, R. J.; Zhang, S.; Dong, Q. Longitudinal relations between social avoidance, academic achievement, and adjustment in Chinese children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 2022, 79, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Ding, X., Zhang, W., Ooi, L. L., Coplan, R. J., Zhu, X., & Sang, B. Relations between social withdrawal subtypes and socio-emotional adjustment among Chinese children and early adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence 2023, 33(3), 774–785. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Zhang, Z., Xu, P., Huang, K., & Li, Y. Unsociability and social adjustment of Chinese preschool migrant children: The moderating role of resilience. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1074217. [CrossRef]

- Ran, G., Liu, J., Niu, X., & Zhang, Q. Associations between social withdrawal and peer problems in Chinese and North American youth: A three-level meta-analysis. Journal of Child & Family Studies 2022, 31(11), 3140–3151. [CrossRef]

- Schleider, J. L., Abel, M. R., & Weisz, J. R. Implicit theories and youth mental health problems: A random-effects meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 2015, 35, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Begg, C. B.; Berlin, J. A. Publication bias: A problem in interpreting medical data. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (Statistics in Society) 1988, 151, 419. [CrossRef]

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal 1997, 315, 629–34. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, H. R.; Sutton, A. J.; Borenstein, M. Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis: Prevention, Assessment and Adjustments. Wiley, 2006.

- Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta Analysis Version 3. Biostat 2013.

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in Medicine 2002, 21(11), 1539–1558. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Liu, M., Shu, X., Xiang, S., Jiang, Y., & Li, Y. The moderating effect of marital conflict on the relationship between social avoidance and socio-emotional functioning among young children in suburban China. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13, 1009528. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., Gao, F., Xu, Y., Sun, Y., & Han, L. The relationship between shyness and aggression: The multiple mediation of peer victimization and security and the moderation of parent–child attachment. Personality and Individual Differences 2020, 156. [CrossRef]

- Cai, H.; Huang, Z.; Jing, Y. Living in a changing world: The change of culture and psychology. In D. Matsumoto, H. C. Hwang (Eds.), The Handbook of Culture and Psychology 2019, 786–817. Oxford University Press.

- Chen, X.; Rubin, K.H.; Sun, Y. Social reputation and peer relationships in Chinese and Canadian children: A cross-cultural study. Child Development 1992, 63(6), 1336–1343. [CrossRef]

- Masten, A. S., Morison, P., & Pellegrini, D. S. A revised class play method of peer assessment. Developmental Psychology 1985, 21(3), 523–533. [CrossRef]

- Spangler, T., & Gazelle, H. Anxious solitude, unsociability, and peer exclusion in middle childhood: A multitrait–multimethod matrix. Social Development 2009, 18(4), 833–856. [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G. W. Risk and protective factors and school adjustment: The pathways project (report of research findings for the period 1997-2001). National Institute of Mental Health. 2002.4.

- Mynard, H., & Joseph, S. Development of the multidimensional peer-victimization scale. Aggressive Behavior 2000 26(2), 169–178. [CrossRef]

- Deng, X., Zhang, S., Chen, X., Coplan, R. J., Xiao, B., & Ding, X. Links between social avoidance and frontal alpha asymmetry during processing emotional facial stimuli: An exploratory study. Biological Psychology 2023, 178, 1–9. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).