1. Introduction

Breast cancer is one of the most prevalent cancers worldwide. In 2020, it was estimated that 2.3 million women were diagnosed with breast cancer and caused 685,000 deaths worldwide [

1]. While certain factors including biological sex, age, and family history of breast cancer increase the risk of breast cancer, there are also numerous genetic mutations associated with breast cancer. Mutations in

BRCA1 and

BRCA2 are observed in approximately 25% of breast cancer cases [

2]. Other high-penetrance genes that are predisposing to breast cancer include

PTEN,

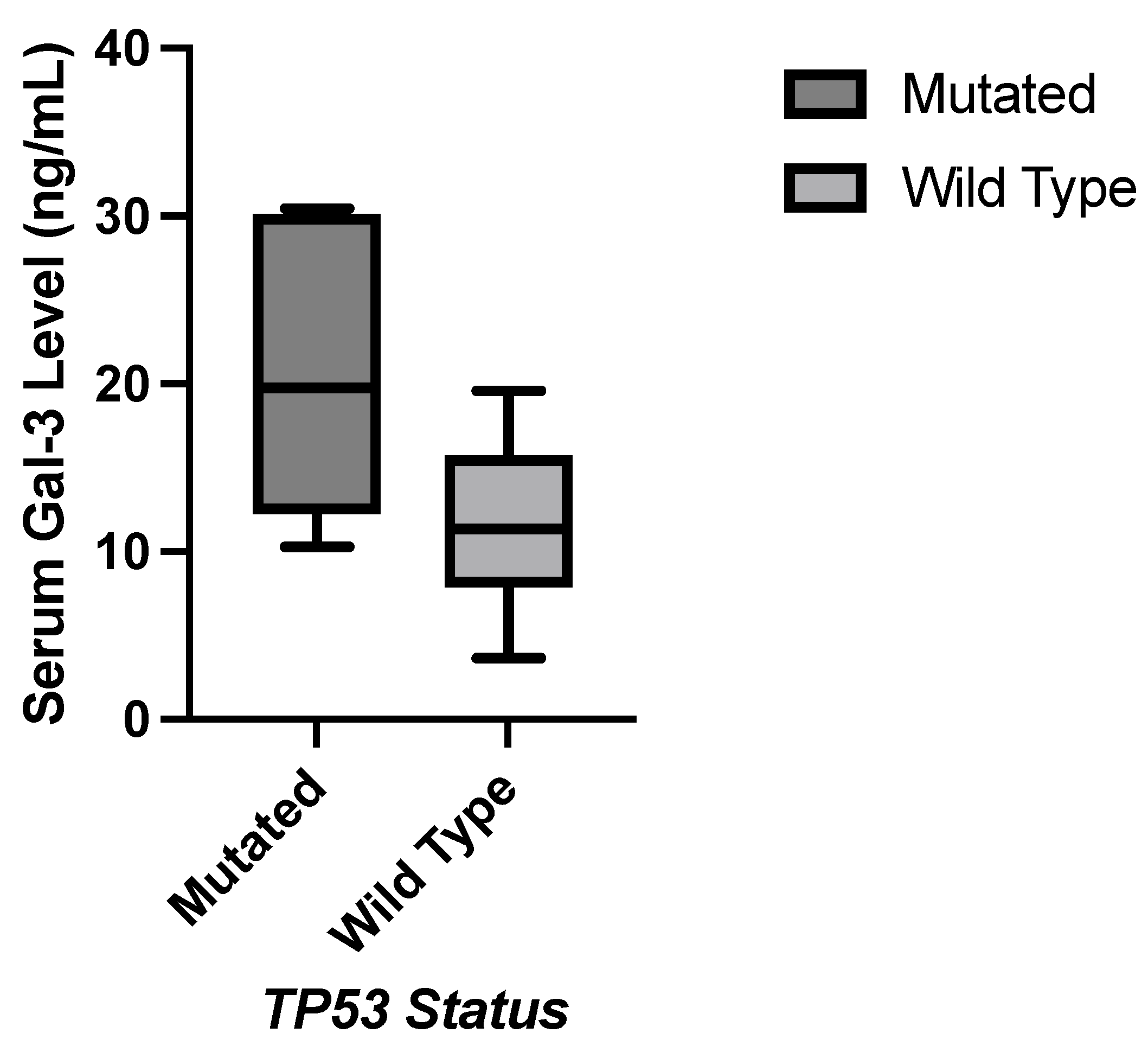

TP53,

CDH1, and

STK11, though mutations in these genes are more rare compared to

BRCA1 and

BRCA2. There are also multiple DNA repair genes that interact with the

BRCA genes such as

ATM,

CHEK2, and

BRIP1 that further increase the risk of breast cancer when mutated. For instance,

CHEK2 is a protein kinase and G2 cell cycle regulator, that stabilizes p53 when DNA damage occurs and interacts with

BRCA1. The 1100delC mutation in

CHEK2 has been found to increase the risk of breast cancer two-fold in women and ten-fold in men. Many of the mutated genes analyzed in this study including

KIT,

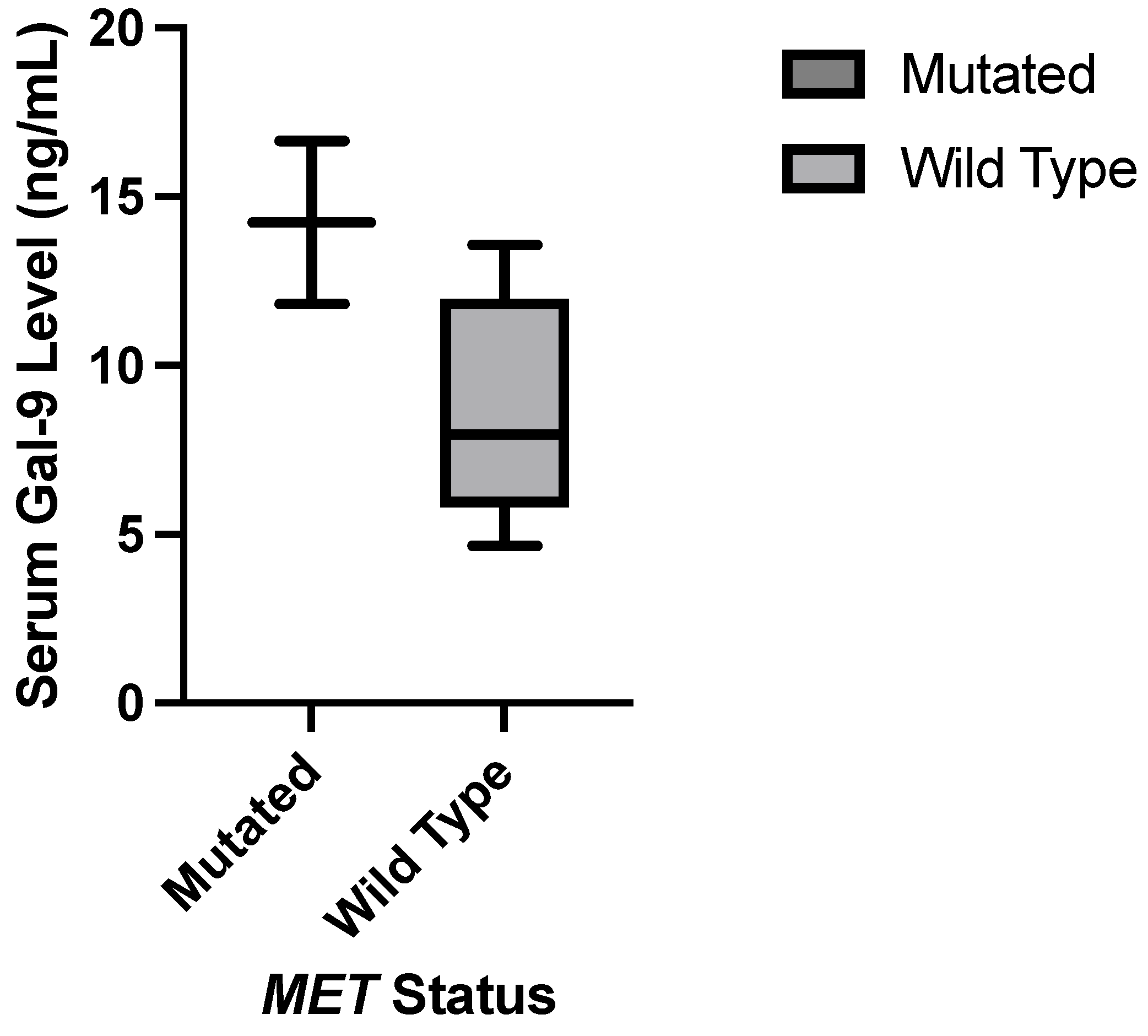

MET, and

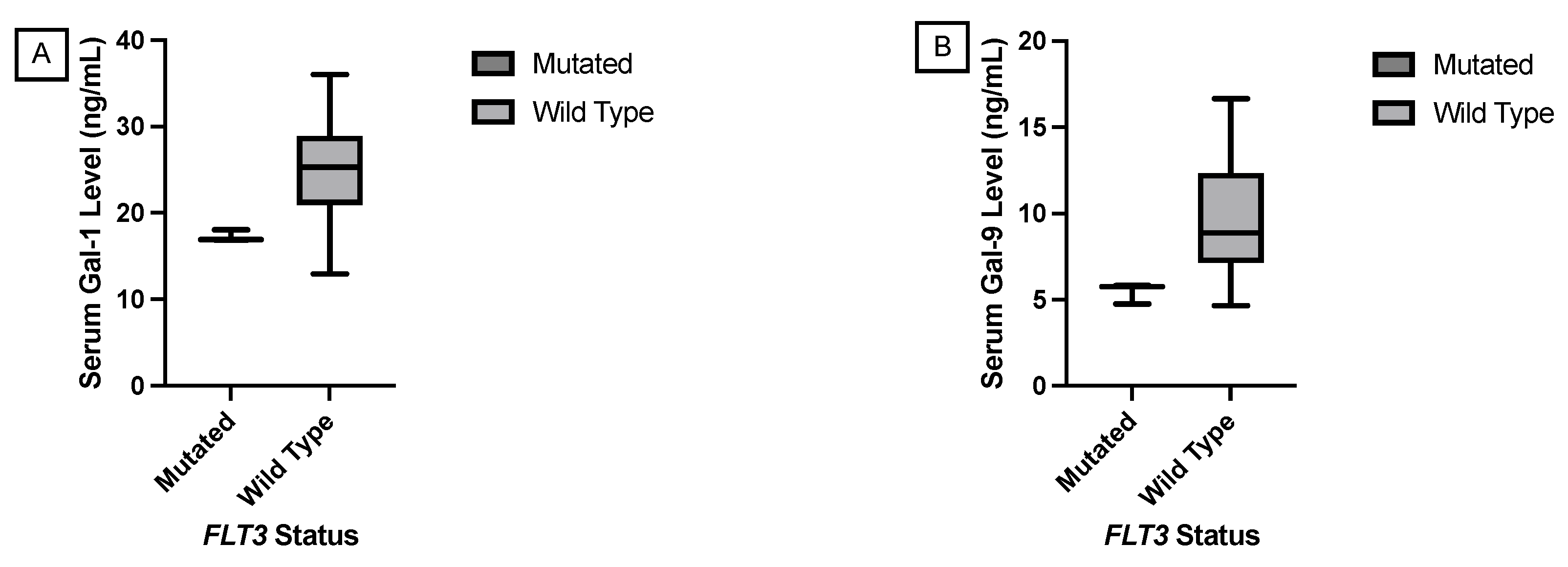

FLT3 play a role in the receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) and RAS pathway. Most RTKs possess a heavily glycosylated extracellular N-terminal binding site and an intracellular tyrosine kinase domain [

3]. These kinases can activate upon interactions with multiple different types of ligands, including galectins. Often in cancer, mutations of genes encoding RTKs result in a gain of function, thereby facilitating cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration [

4].

The most common treatment options for breast cancer include surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy drugs such as anthracyclines, taxanes, and alkylating agents [

5]. Current strategies for personalized treatments are based on the molecular subtype of breast cancer, Luminal A, B, HER2, and Triple Negative (TNBC), and its expression of Hormone Receptor (HR). For instance, trastuzumab is an antibody that targets HER2 receptors, however, this drug would not be effective against TNBC. Therapies against TNBC must target other tumor markers such as VEGF with bevacizumab or EGFR with cetuximab. Since many of these drugs are broad-acting, damaging healthy cells in the process and causing various adverse effects, it is desired to develop therapies that are capable of targeting cancer cells. One such target that has gained attention in research is galectins.

Galectins are a family of soluble proteins that are expressed across various cell types and participate in numerous cellular processes including regulation of cell growth, apoptosis, cell migration, and immune evasion for tumors [

6]. For instance, galectin-1 has been shown to increase the frequency of Foxp3+ T

reg cells in the microenvironment of breast cancer cells, contributing to tumor evasion of the immune system [

7]. Similarly, another study found Gal-1 to interact strongly with N-glycosylated neuropilin-1 on PDGFR and TGF-

R. This induced TGF-

and PDGF signaling, promoting migration and activation of hepatic stellate cells [

8]. Looking at other galectins, galectin-3 has demonstrated the ability to prevent nitric oxide-induced apoptosis in human breast carcinoma cells [

9]. Zhang et al. found that galectin-3 knockdown breast cancer cells treated with the apoptotic inducer arsenic trioxide increased its apoptotic effects compared to galectin-3 positive breast cancer cells; demonstrating the role of galectin-3 in inhibiting apoptosis [

10]. Additionally, galectin-3 can disrupt N-cadherin cell-cell junctions, demonstrating a mechanism for galectin-3 to promote tumor cell motility and metastasis [

11]. Galectin-9 is peculiar in that studies demonstrate its ability to act as a tumor-promoting and anti-tumor protein. Morishita et al. demonstrated the ability of galectin-9 to promote apoptosis in colon cancer, which they suspected is through increased phosphorylation of the RTKs ALK, DDR1, and EphA10 [

12]. Meanwhile, galectin-9 has also been shown to bind to Tim-3, a cell surface molecule on Th1 cells that suppresses their immune functions and induces apoptosis [

13]. Considering the variety of galectins and their numerous processes in promoting cancer development, the concept of galectin inhibitors sparks interest as a potential therapy.

The development of galectin inhibitors began decades ago when the role of galectins in cancer progression and tumor development was discovered. There are currently two main types of galectin inhibitors in trials: carbohydrate-based and non-carbohydrate-based [

14]. Thiodigalactoside, a carbohydrate-based galectin-1 inhibitor, has been shown to prevent angiogenesis and tumor growth while preventing metastasis and inducing apoptosis of tumor cells in breast cancer samples in tumor mouse models [

15]. Anginex is a peptide-based galectin-1 inhibitor that shows promising evidence for inhibiting tumor growth, proliferation, and angiogenesis [

16]. Modified citrus pectin is a carbohydrate-based galectin-3 inhibitor that has also shown antimetastatic properties as well as promise in inhibiting tumor growth and restoring T-cell surveillance [

17]. Many studies and early-phase clinical trials are investigating the efficacy of galectin inhibitors with and without other chemotherapies or monoclonal antibodies. These include gene-specific targeted therapies, which have been in practice since the development of imatinib to target

BCR-ABL in 2001. FDA-approved therapies specific to breast cancer include Olaparib, which targets

ATM,

BRCA1/2, and

CHEK2 mutations, as well as alpelisib, which targets

PIK3CA mutations [

18]. In a phase I trial, GM-CT-01, a galectin-1 and -3 inhibitor, is being tested with and without 5-fluorouracil in patients with advanced-stage solid tumor cancers, including breast cancer to study the effects of galectin inhibitors on disease progression and their ability to improve chemotherapy response in patients who have not responded well to previous treatments [

19]. Another study found that combining a galectin-9 inhibitor with AZD1930, an

ATM inhibitor, led to decreased tumor growth and significantly longer survival for mouse models [

20]. In addition, genetic profiles of cancer patients are commonly used to guide chemotherapy decisions based on inherent risk and prognosis associated with specific mutations.

With the increasing interest in galectins as a target in cancer therapy, this paper seeks to explore the relationship between cancer-driving mutations in breast cancer patients and serum galectin levels. Additionally, tumor characteristics including stage and metastasis were analyzed in relation to galectin levels and mutations. The results of our research could provide new insights into the correlations between specific breast cancer mutations and certain galectins. As galectin inhibitors are employed in conjunction with existing therapies, understanding the relationships between certain mutations and galectins could help produce more personalized therapeutic regimens that improve responsiveness and patient outcomes. Additionally, the correlation between specific genetic mutations and galectin levels will provide crucial insights into ideal candidates for galectin-modulated therapies.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. PRISMA Biorepository

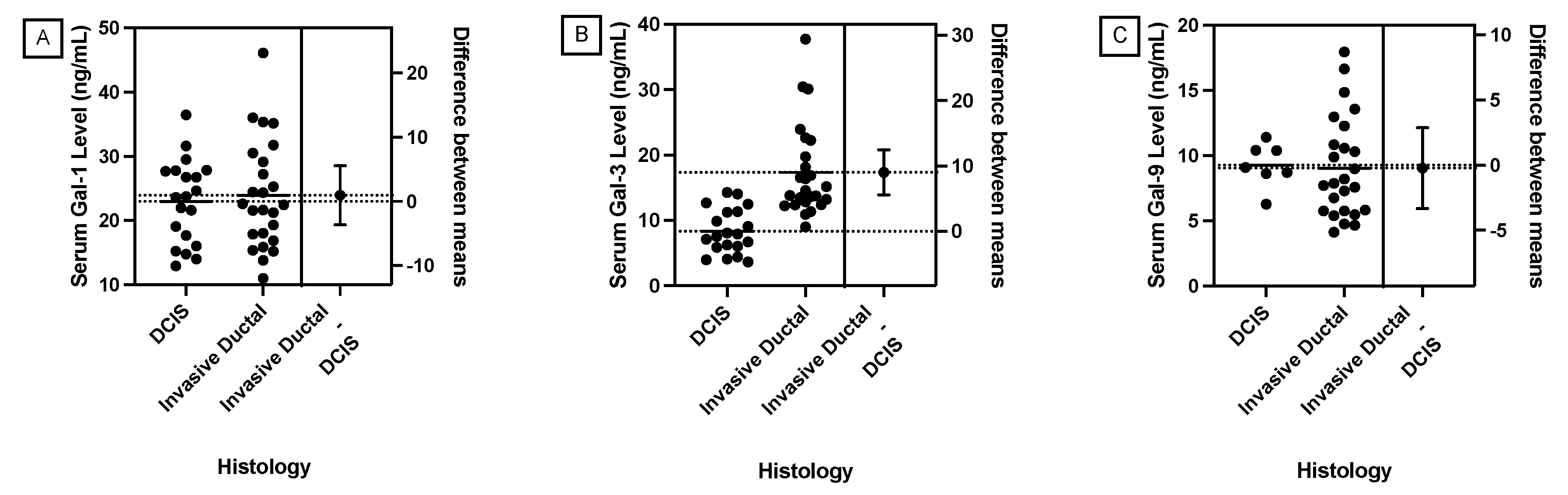

Seventy-one Breast Cancer Patient Samples were obtained from PRISMA Health Cancer Institute’s Biorepository (PHCI) based on specimen and gene panel availability. All patient samples are serum samples and patients signed a consent form when the tissue was procured. Patient sample data is included in the Supplementary Materials section.

Thirty-six of the samples were obtained from patients with the Luminal A subtype (50.7%), nine were from patients with the Luminal B subtype (12.7%), six were from patients with the Luminal A HER2 Hybrid subtype (8.5%), two were from patients with the Luminal B HER2 Hybrid subtype (2.8%), two were from the HER2 Positive subtype (2.8%), twelve were from patients with the Triple Negative subtype (16.9%), and the molecular subtypes of four patients were unknown (5.6%).

Twenty-four of the samples were from patients with breast cancer classified as stage I (33.8%), twenty-eight of the samples were from patients with breast cancer classified as stage II (39.4%), thirteen of the samples were from patients with breast cancer classified as stage III (18.3%), and six of the samples were from patients with breast cancer classified as stage IV (8.45%). Fifty-nine of the samples were from patients with primary breast cancer (83.1%), eight of the samples were from patients with metastatic breast cancer (11.3%), and four of the samples were from patients with recurrent breast cancer (5.6%).

2.2. ELISA for Galectin Profiling

The galectin levels of patients’ sera were analyzed using enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA). ELISA kits from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) were used to measure the concentrations of galectins-1, -3, and -9. The serum concentrations of galectins-1 and -3 were effectively obtained in all seventy-one samples and the serum concentration of galectin-9 was obtained in fifty samples.

2.3. HotSpot Panel for Cancer-Critical Genetic Mutations

Genetic Mutation Data for 65 samples was obtained by Precision Genetics as described in "KIT Mutations Correlate with Higher Galectin Levels and Metastasis in Breast and Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer" [

21].

Data for an additional six samples was obtained by University of South Carolina College of Pharmacy Functional Genomics Core Facility. Genomics DNA had been purified from frozen tumor samples with QIAGEN DNA Blood & Tissue Kit (#69506, QIAGEN, Carlsbad, CA), Genomics DNA from FFPE tumor samples had been purified with Quick-DNA FFPE MiniPrep Kit (D3067, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Cancer hot-spot mutation regions were amplified with CleanPlex OncoZoom Cancer Hot-spot Panel (SKU:916001 Paragon Genomics, Hayward, CA). The panel includes 601 amplicons, covering 65 genes.

The amplicons were sequenced with Illumina Novoseq 6000 in a partial lane of the S4 flow cell, PE150, with a sequencing depth of 2 million reads per sample. The sequences had been aligned to Paragon Genomics amplicons reference sequences and the variants were called with GATK pipeline (PMID: 25431634). The biologically and clinically relevant tumor-specific alternation had been determined with the Cancer Genome Interpreter (PMID: 29592813) and NCBI ClinVar database (PMID: 29165669)).

2.4. Data Analysis

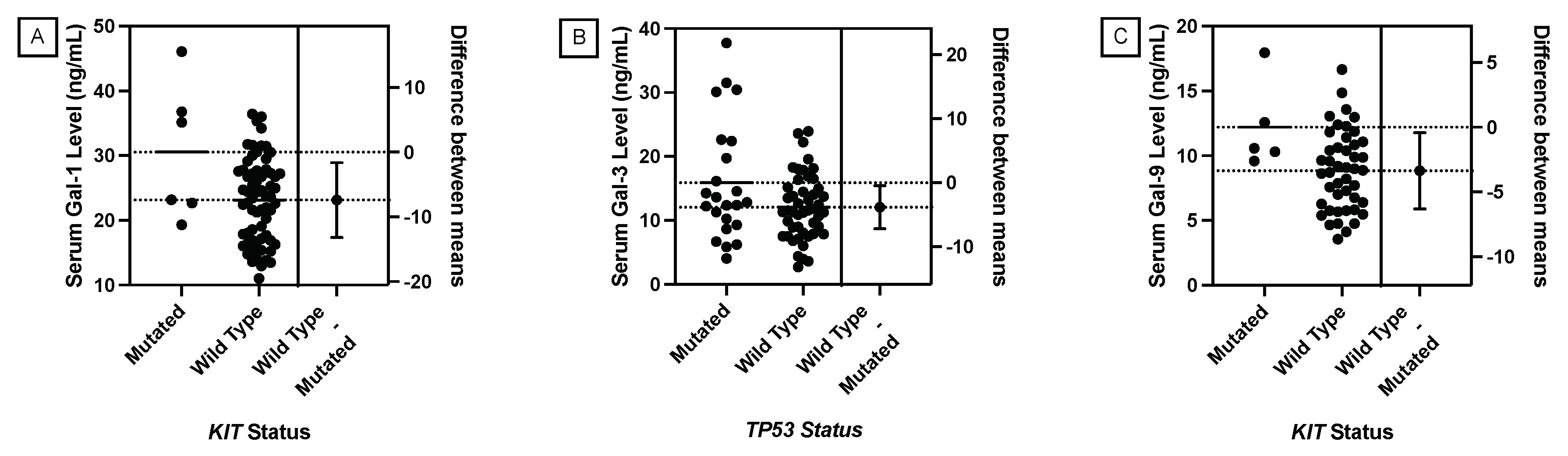

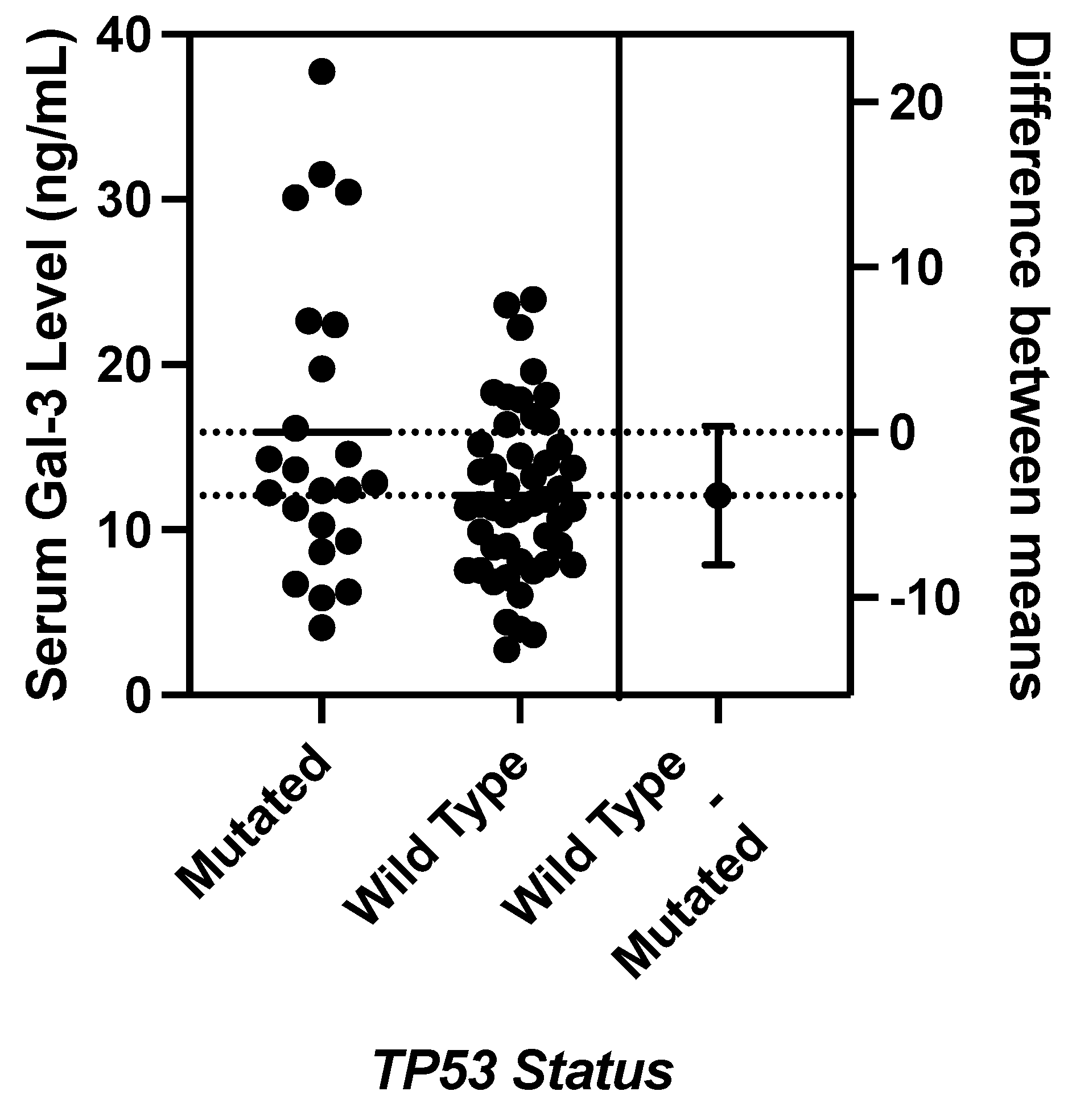

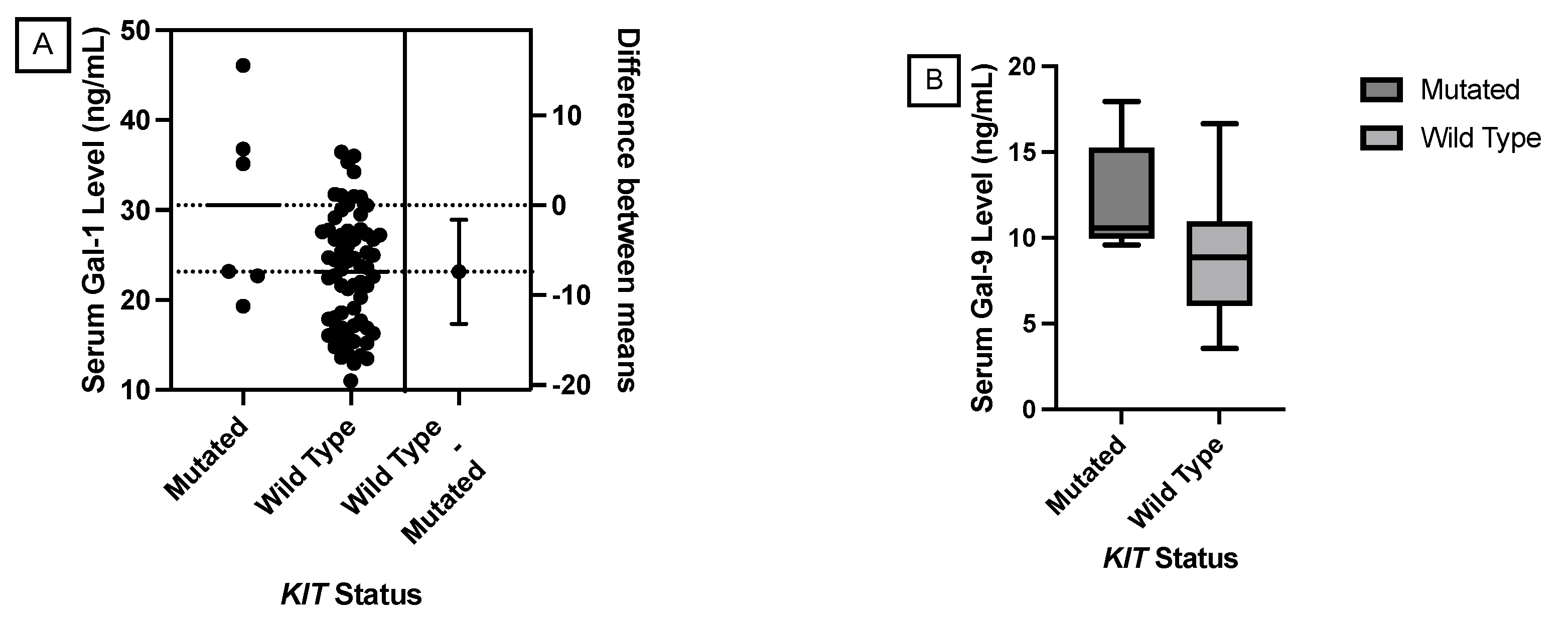

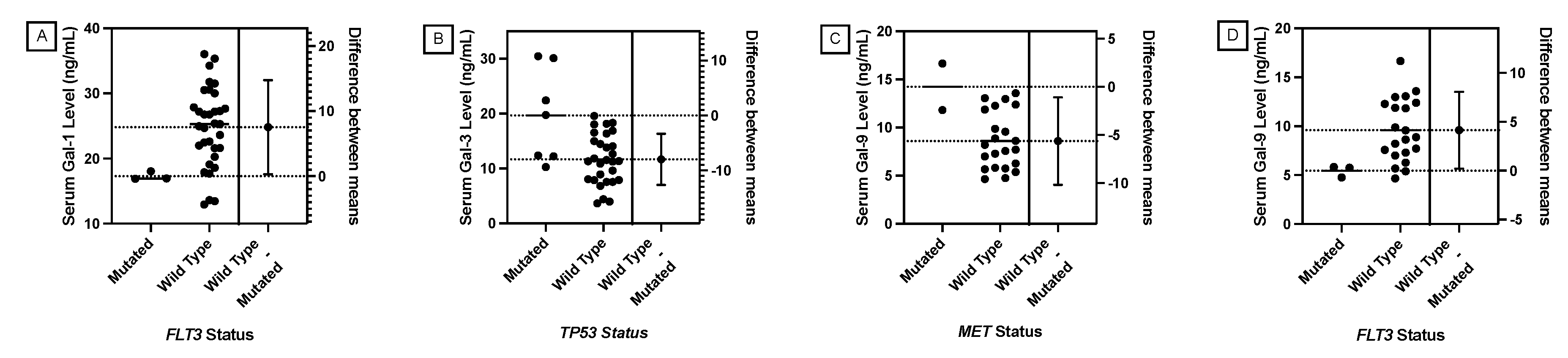

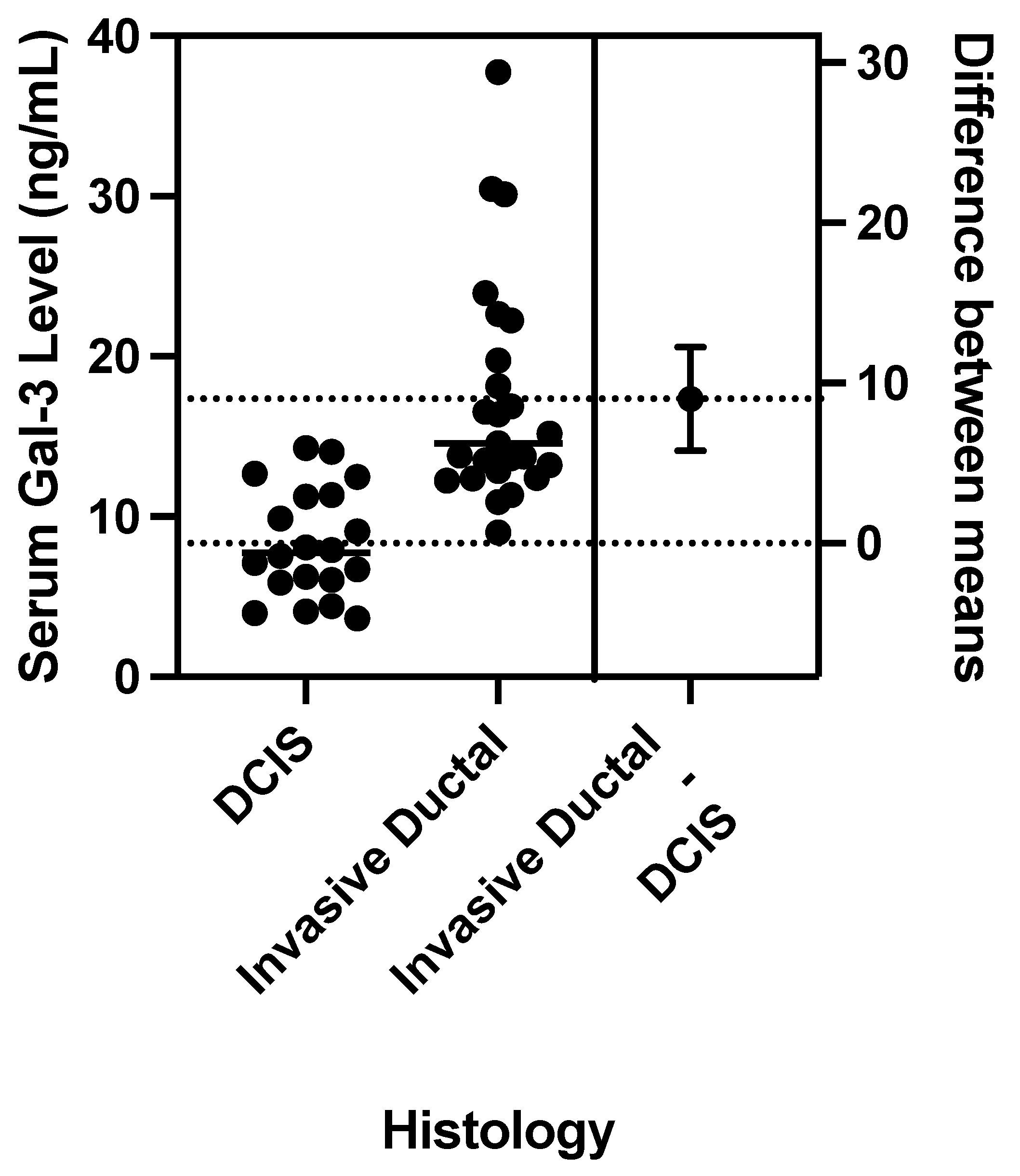

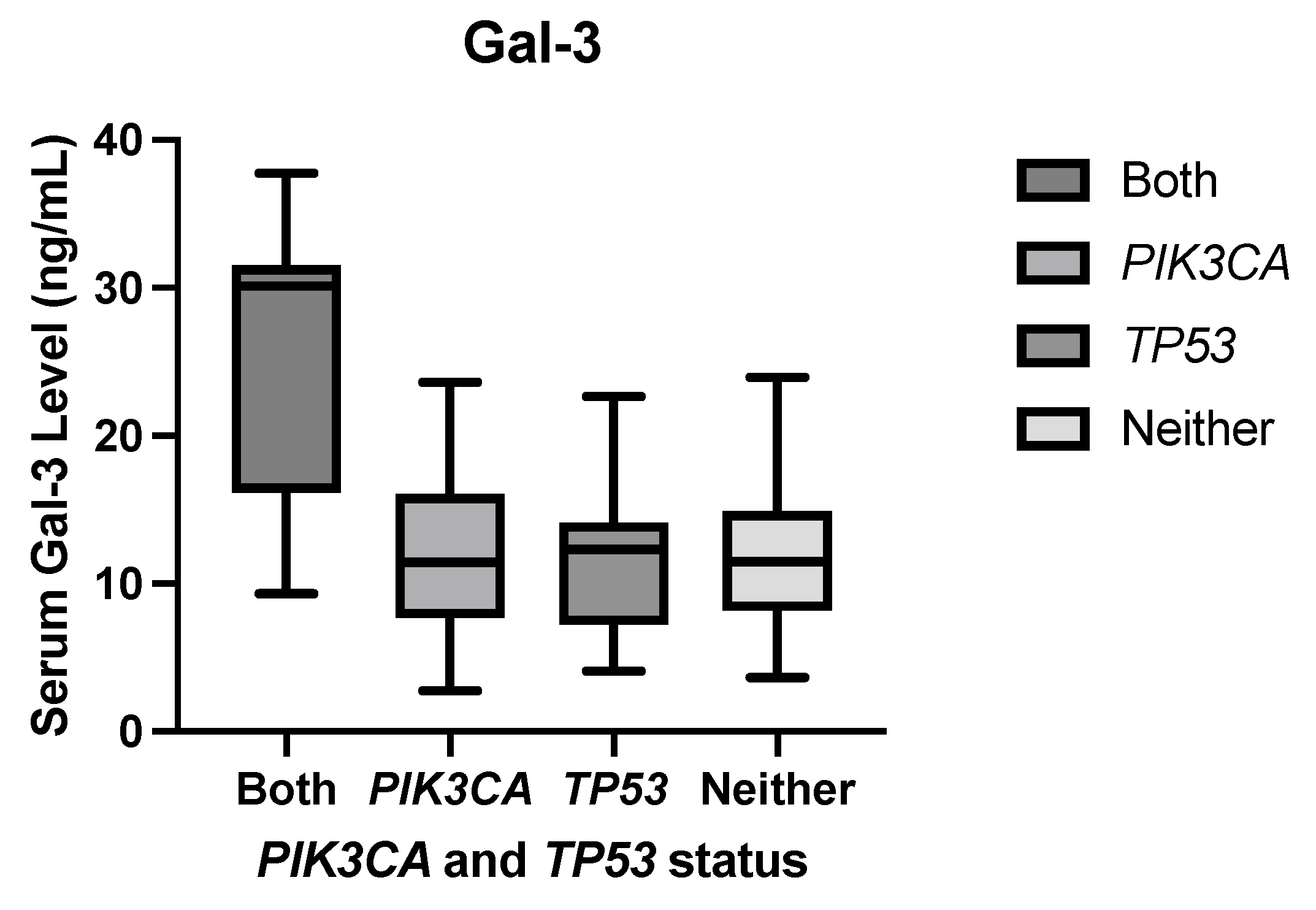

JMP was used to generate statistical analyses. JMP is a software by the SAS Institute (Cary, NC, USA). Prism was used to generate the figures included in this paper. Prism is a part of GraphPad Software (Boston, MA, USA). The distributions of serum galectin levels of samples with specific genetic mutations were compared using a t-test for the difference of means. A Levene’s test for equality of variances was used to determine whether a pooled two-sample t-test, which assumes equal variances between the populations, or Welch’s test, which assumes unequal variances between populations, is more appropriate. For tests with small sample sizes (n<10), a Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test was performed to compare medians was performed because normality of residuals could not be assumed. For tests comparing more than two samples, ANOVA, Tukey’s Range Test, and Steel Dwass test were used for parametric and nonparametric comparisons. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.B; methodology, A.V.B., E.G.M., A.T.F. and M.S.; validation, E.G.M., A.T.F., and D.H.A.; formal analysis, E.G.M., A.T.F., and D.H.A.; investigation, E.G.M., A.T.F., D.H.A., M.S., W.J.E. and A.V.B.; resources, A.V.B., M.S., J.C.M. and W.J.E.; data curation, E.G.M., A.T.F., D.H.A. and J.C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.G.M. and D.H.A.; writing—review and editing, E.G.M., D.H.A., A.T.F., M.S. and A.V.B.; visualization, E.G.M., D.H.A. and A.T.F.; supervision, A.V.B.; project administration, A.V.B.; funding acquisition, A.V.B., M.S., J.C.M. and W.J.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.