1. Introduction

During the last two decades, concerns have arisen about the intense environmental degradation generated by the emission of toxic substances (Nguyen et al., 2023), waste of hazardous materials (Yusoff et al., 2020), and the rapid depletion of ecological resources of firms’ harmful processes from worldwide (Ahmad, 2015). Given the growing environmental crisis, governments have attempted to establish various measures to protect and mitigate adverse ecological effects on the environment (Kim & Kim, 2022). Hence, firms have embraced going green in an effort not to violate environmental measures (Margaretha & Saragih, 2013).

The Green concept is an operational relating to the environment (Razab et al., 2015) aimed at designing and implementing green strategies and policies (Jabbar & Abid, 2015) to reduce the firms’ negative environmental effects and promote eco-conscious utilising of natural resources (Dumont et al., 2017).

One of the most critical green strategies for promoting Environmental performance (EP) and sustainability is Green Human Resource Management practices (Green HRM) (Nasir et al., 2023). The Green HRM concept is primarily developed by merging HRM practices with environmental management (Jackson et al., 2011). Green HRM refers to “the use of HRM policies, philosophies, and practices to promote sustainable use of resources and prevent harm arising from environmental concerns within business organisations” (Zoogah, 2011). Therefore, the literature asserts that the effective adoption of Green HRM addresses environmental concerns to a great extent (Renwick et al., 2013).

Mainly, scholars contend that putting the Green HRM practices into action is influential in enhancing the EP (Roscoe et al., 2019), which, in turn, leads to the enhancement of Sustainability (Baral et al., 2023) and further promotes Employee Health Orientation (EHO) (Dutta, 2012).

The Green HRM literature shows that Green HRM practices are relatively new concepts that generate increased concern among management scholars and practitioners with enormous theoretical as well as empirical research gaps to address (Nawangsari & Sutawidjaya, 2019). Hence, there is a call for further research to examine how EP is affected by Green HRM practices as a bundle (Obeidat et al., 2020; Úbeda-García et al., 2021; Yusoff et al., 2020). In particular, Paillé et al. (2020) highlight that scarce studies exist concerning how environmental consequences are influenced by Green HRM practices.

The current literature is still debatable and ambiguous on whether sustainability can be achieved through Green HRM practices (Ahmed et al., 2019). In particular, there is still a lack of understanding of whether Green HRM practices improve sustainability, more specifically when considering developing economies (Amjad et al., 2021).

Given the limitations in the previous EP studies, there is a lack of focus on testing EP's role in achieving sustainability (Nguyen et al., 2021). Accordingly, there is a need to further identify whether EP has any impact on sustainability (Baral et al., 2023).

Recent studies argue that analysing the effects of implementing green practices and policies should be based on investigating their role in improving EHO (Alam et al., 2023). However, to our knowledge, there is no evidence that Green HRM leads to improving EHO and whether the firms’ efforts to improve EP will lead to improving EHO. Further, whether EP may play a mediating role in the Green HRM-EHO link.

Drawing on both RBV and the theory of stakeholders, the current study adds four contributions to the existing body of Green HRM literature by bridging the above-mentioned gaps. First, it analyses the direct impact of Green HRM practices on both EP and sustainability. Second, it establishes the relationship between Green HRM practices and EHO. Third, it examines the potential mediating role of EP between Green HRM practices and sustainability relationship. finally, it explores the potential mediating role of EP between Green HRM and EHO relationship. In line with the abovementioned contributions, this study is significant and relevant.

The paper begins by introducing the theoretical framework. The following sections present the hypotheses, methodology, and study results. The next section includes discusses the findings. The concluding section offers the practical implications, highlights limitations, and outlines directions for further studies.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypotheses Development

2.1. The Study Context

In India, the service, manufacturing and agriculture sectors are the main pillars of the economy (Gupta et al., 2022). They contribute to the country's GDP while committing to eco-friendly practices (Amrutha & Geetha, 2020). The service sector contributes approximately 24.63 % of the total GDP (Sahoo, 2022), manufacturing accounts for around 16% of the total GDP, and renewable energy contributes approximately 7% of the total GDP (Tiwari & Sharma, 2022).

According to the World Bank, the GDP of India will be reduced by climate change by approximately 3%. It will impact roughly half of its population by 2050 if the government does not impose restrictions (Srivastava et al., 2022). In response to the environmental challenges, the government of India has launched a series of initiatives and policies to achieve a greener economy (Bansal et al., 2023), such as the National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC) and the National Green Tribunal. These initiatives and policies aim to increase renewable energy expansion and energy efficiency of manufacturing and service firms by encouraging them to adopt eco-friendly technologies (Rani, 2023). Consequently, the renewable energy industry has witnessed remarkable growth by making India the fourth-largest producer of wind power and the fifth-largest producer of solar power worldwide (Kumar et al., 2023).

2.2. Green HRM and EP

EP refers to “the commitment of organizations to protect the environment and to demonstrate measurable operational parameters that are within the prescribed limits of environmental care” (Paillé et al., 2014). The literature has argued that Green HRM practices’ crux is to promote EP (Nawangsari & Sutawidjaya, 2019). For instance, green training provides opportunities for firms to enlighten employees, from the leadership to the front-line staff (Paillé et al., 2014) on how to become green (Razab et al., 2015) and also how to engage in solving environmental issues (Zoogah, 2011). In addition, improving EP requires a green reward and compensation system (Arulrajah et al., 2015) to motivate employees to participate effectively in green initiatives (Jabbar & Abid, 2015).

The empirical evidence on the Green HRM practices-EP link is mixed. Some studies reveal positive effects of Green HRM practices on EP, either in the manufacturing firms’ context (Ghouri et al., 2020; Roscoe et al., 2019; Singh et al., 2020; Zaid et al., 2018) or the service firms’ setting (Anwar et al., 2020; Gilal et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Mousa & Othman, 2020; Paillé et al., 2020; Rawashdeh, 2018; Shafaei et al., 2020).

Conversely, some studies reveal that EP is not significantly affected by the practices of Green HRM (Pham et al., 2020). For example, recent research by Elshaer et al. (2021) reported no direct effect of Green HRM practices on EP.

However, this study follows the evidence that Green HRM positively impacts EP because environment management is incorporated into HRM practices purposely to help firms improve EP (Renwick et al., 2008). Building upon the above-cited literature, the current study develops the following hypothesis:

H1. Green HRM practices have a positive and significant effect on EP.

2.3. Green HRM and Sustainability

Sustainability refers to “the capacity to sustain the economy, society and environment” (Malik et al., 2020). It is mainly measured through “The triple bottom line” model coined by Elkington (2006), involving three dimensions: economic, social, and environmental sustainability (Scalia et al., 2018).

Scholars have emphasised the contribution of Green HRM practices to sustainability (Jerónimo et al., 2020). For instance, Ren et al. (2018) contend that Green HRM practices enhance the awareness and commitment of firms’ employees toward achieving sustainability.

Although few empirical studies have investigated the impact of Green HRM practices on sustainability, the results present mixed evidence. On the one hand, studies have reported that sustainability is impacted positively by Green HRM practices (Ahmed et al., 2019). For instance, a recent study by Amjad et al. (2021) report that Green HRM practices, namely, training, appraisal, and compensation, significantly impact sustainability.

On the other hand, Yong et al. (2019) reveal that green recruitment, as well as green training, positively impact sustainability as opposed to “green analysis and job description, green selection, green performance assessment, and green reward”, which have no impact on sustainability. In addition, Owino and Kwasira (2016) report that green occupation health and safety and green performance management influence environmental sustainability, but green training does not. Based on the above literature, we develop the following hypothesis:

H2. Green HRM practices have a positive and significant impact on sustainability.

2.4. Green HRM and EHO

EHO refers to “a strategic and operational coordination of policies, programs, and practices designed to simultaneously prevent work-related injuries and illnesses and enhance overall workforce health and well-being” (Sorensen et al., 2013). As emphasised by Beehr and Newman (1978), firms prioritise improving the orientation towards employees’ health and safety over conventional considerations like employee motivation, attitudes, and job performance because employee health and safety is an essential good that firms strive to maintain (Wright & Wright, 2002).

So far, the body of Green HRM literature lacks studies addressing the nexus between Green HRM and EHO, particularly whether Green HRM leads to improving the EHO.

Firms address employee health and safety risks by developing strategies like non-polluting green factories and green zones (Rubel et al., 2021). Further, they embrace Green HRM practices as one of the green strategies to contribute to employee health and safety (Mahdy et al., 2023). Green HRM practices include health programs to promote good nutrition and fitness, avoid health diseases (Arulrajah et al., 2015) and improve overall employees’ health and safety (Dutta, 2012). In addition, Shaikh (2010) and Siyambalapitiya et al. (2018) claim that the policies and practices of Green HRM enhance EHO. Besides, a recent study by Amrutha and Geetha (2020) proposes that implementing Green HRM practices such as “green hiring, green training, green appraisal, green rewards, and green employee involvement” will contribute to the overall EHO. Therefore, we propose that adopting the practices of Green HRM will promote the EHO. Based on the logic and previous studies, we hypothesise the following:

H3. Green HRM practices will have a positive and significant effects on EHO.

2.5. EP and Sustainability

Scholars have addressed the importance of EP to sustainability in two different ways. On the one hand, firms seek to improve EP as a means to achieve sustainability, expand their competitive advantage and increase economic profitability (Koo et al., 2014). On the other hand, firms improve EP to avoid the risk of legal accountability, sales loss, and reputation decline (Wang et al., 2014). Therefore, the interaction between the firms and their environment is seen as a pillar of improving social, economic and environmental sustainability (Úbeda-García et al., 2021). EP is a crucial predictor of sustainability since reducing air emissions, material waste, use of hazardous and toxic materials, and environmental accidents contribute to the EP of firms (Awan et al., 2023).

Empirically, Amjad et al. (2021) report that EP has a significant effect on organisational sustainability in the textile industrial sector of Pakistan. Similarly, Baral et al. (2023) present that EP positively affects sustainability. Based on the above literature, we posit the following hypothesis:

H4. EP has a positive and significant effect on sustainability.

2.6. EP and EHO

Improving employee health is one of the critical concerns of firms (Hilsdorf et al., 2017). Moreover, firms seek to minimise the risks that are associated with employees by identifying environmental issues that present a challenge to the health and safety of employees (Chen et al., 2022; Geng et al., 2023; Han & Huo, 2020; Suharti & Sugiarto, 2020) and mitigate them to create a healthy working environment for them (Gouda & Saranga, 2020). Further, Li et al. (2023) and Gu (2023) found that EP reduces health benefit costs by improving the employees’ health. Based on the above discussion and also on the stakeholder’s theory, we propose that EP will affect EHO. Hence, we hypothesise the following:

H5. EP has a positive and significant effect on EHO.

2.7. The Mediating Role of EP in the Link between Green HRM and Sustainability

Scholars argue that firms adopt Green HRM to strengthen environmental practices by improving their employees' commitment and behaviour to protect the environment (Masri & Jaaron, 2017). This, in turn, promotes achieving sustainability (Nasir et al., 2023).

No studies were identified that examined the mediating role of EP in the link between Green HRM and the three dimensions of sustainability, namely social, economic and environmental sustainability. Nevertheless, an empirical attempt has been conducted by Amjad et al. (2021) to investigate the mediating role of EP in the relationship between Green practices of HRM and environmental sustainability. The researchers observed that EP partially mediates the link between practices of HRM and environmental sustainability. Building on the above literature, we propose that:

H6. EP mediates the relationship between Green HRM practices and sustainability.

2.8. The Mediating Role of EP in the Link between Green HRM and EHO

Alam et al. (2023) argue that the effective implementation of green strategies supports the association between the workforce and the environmental process of firms, which in turn leads to improving employees' health and well-being. In addition, the literature indicates that firms adopt Green HRM practices as a means to protect the environment and simultaneously make a positive contribution to the health, safety and well-being of employees (Al-Hawari et al., 2021; Kuuyelleh et al., 2021; Saeed et al., 2019). Given the dual objectives of Green HRM practices of helping firms improve EP (Siyambalapitiya et al., 2018) and employees' health and well-being (Mahdy et al., 2023), this study proposes that EP will play a mediating role between Green HRM and EHO. Based on the above-mentioned discussion, we put forward the following hypothesis.

H7. EH will mediate the relationship between Green HRM and EHO.

3. Theoretical Base

This study uses the resource-based view (RBV) and the theory of stakeholders to explain how Green HRM practices help firms enhance their EP and achieve sustainability and also in order to explain how the EP assists firms in improving sustainability and EHO.

The RBV theory explains the relationship between a firm’s resources and its performance (Barney, 1991), where the resources of the firm determine its performance (Barney, 2001). The recent literature explains how RBV can be used to identify the effect of Green HRM practices on EP (Awan et al., 2023) and also the influence of EP on sustainability (Amjad et al., 2021). Guided by the assumptions of RBV theory, this study investigates the effect of Green HRM practices on EP and sustainability.

Environment, employee health and safety issues have become critical concerns for stakeholders of any firm (Freeman, 1984; Ikram et al., 2019). Stakeholders demand that firms must use the resources efficiently and minimise hazardous environmental effects in order to conserve the environment, achieve sustainability and enhance employees’ health and safety in the workplace and society (Zighan et al., 2023).

To fulfil the stakeholders’ demands, firms have engaged in green practices (Ayayi & Wijesiri, 2022) to improve their EP (Umrani et al., 2020) and protect the employees’ health and well-being (Li et al., 2023) and achieve sustainability (Awan et al., 2023). Drawing on the stakeholders’ theory, which posits that firms engage in environmentally friendly activities in order to improve their EP for fulfilling and balancing the interests of their different stakeholders (Nguyen et al., 2021), the present study uses this theory in the role of a theoretical foundation in order to determine the effect of EP on sustainability and EHO.

4. Methodology

A quantitative research design was adopted for the study using an E-survey questionnaire. To ensure the sample is more representative of the total population, data was collected from both service and manufacturing firms across India. The sample included respondents who had knowledge about the study's constructs and were at the level of Deputy General Manager or higher in the organisational hierarchy.

4.1. Participants and Procedures

1200 participants were requested by email to participate in the study's survey. Initial cover letters involving a hyperlink to access the survey's questions were emailed to the respondents, explaining the aim of the current research. Reminder emails were sent after a week, followed by another reminder after another week. After three months of data collection, 318 responses were returned, resulting in a response rate of 26.50% (see

Table 1).

Concerning the firms' types, manufacturing firms constituted 69.5% of the sample, while service firms comprised 30.5% of the sample. About ownership, 67.9% were family businesses, followed by collaboration with international firms 19.6%, Public Limited 7.5%, and Private Limited 0.5%. For annual turnover, 16.4% of firms gained less than 5 Crores, 19.8% between 5-75 Crores, 30.2% between 75-250 Crores, and 33.6% above 250 Crores (See, Table.1).

4.2. The Measurement Instruments

The authors adopted the questionnaire items from previous studies that are reliable and validated measures. All of the model’s constructs were estimated on a five-point Likert scale.

Green HRM practices were measured by 14 items-scale distributed on four dimensions: “job analysis and descriptions, recruitment and selection, training, and appraisal and reward”, which was taken from (Jabbour et al., 2010). EP was measured by 7 items derived from Melnyk et al. (2003) and Daily et al. (2007) studies.

A set of 9 items was adopted from Gericke et al. (2019) to measure sustainability; 3 items to measure each dimension of sustainability that are “social, economic, and environmental sustainability”. Finally, the scale to estimate EHO was derived from Della et al. (2008), which contains 12 items distributed on 4 dimensions: awareness, business alignment, leadership support and worksite practices.

Table 2 details the measurement items that measure each construct and sub-construct.

4.3. Common Method Bias

As Podsakoff et al. (2003) highlighted, Common method bias (CMB) is a potential threat to conducting social studies using a cross-sectional questionnaire technique. In response to that, Kock and Lynn (2012) propose the full collinearity test (FCT), which is based on the variance inflation factor (VIF) for assessing the potential of CMB existence in the PLS-SEM model. The results demonstrate that the values of VIF for all model constructs of this study were below the cut-off value of 3.3. This suggests the absence of CMB in the model of this study (Kock, 2015).

5. Data Analysis and Results

In order to investigate the study model, the partial least square structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM) is applied. Since Green HRM, EHO, and Sustainability constructs are multidimensional constructs which involve some sub-constructs/dimensions, PLS-SEM was chosen as a suitable statistical technique because it allows analysis of complex models, including Second-order constructs (SOCs) (Sarstedt et al., 2019).

In light of this, the two-stage approach was used, including the measurement model assessment and the structural model assessment. The measurement model assessment includes the study's model's internal consistency reliability and convergent and discriminant validity. Meanwhile, the structural model assessment involves testing the study's hypotheses and predictive power (Hair et al., 2019). The Smart-PLS 4 software was used for the study's analysis (Ringle et al., 2022).

5.1. Assessment of Measurement Model

5.1.1. First-Order Measurement Model Assessment

In the initial step, Cronbach’s Alpha (α), Composite Reliability (RC), Dijkstra and Hensler’s rho_A (rho_A), Average Variance Extracted (AVE), and Factor loadings were employed as metrics to assess the study's model's internal consistency reliability and convergent and discriminant validity of the first-order constructs (FOC) (Hair et al., 2019).

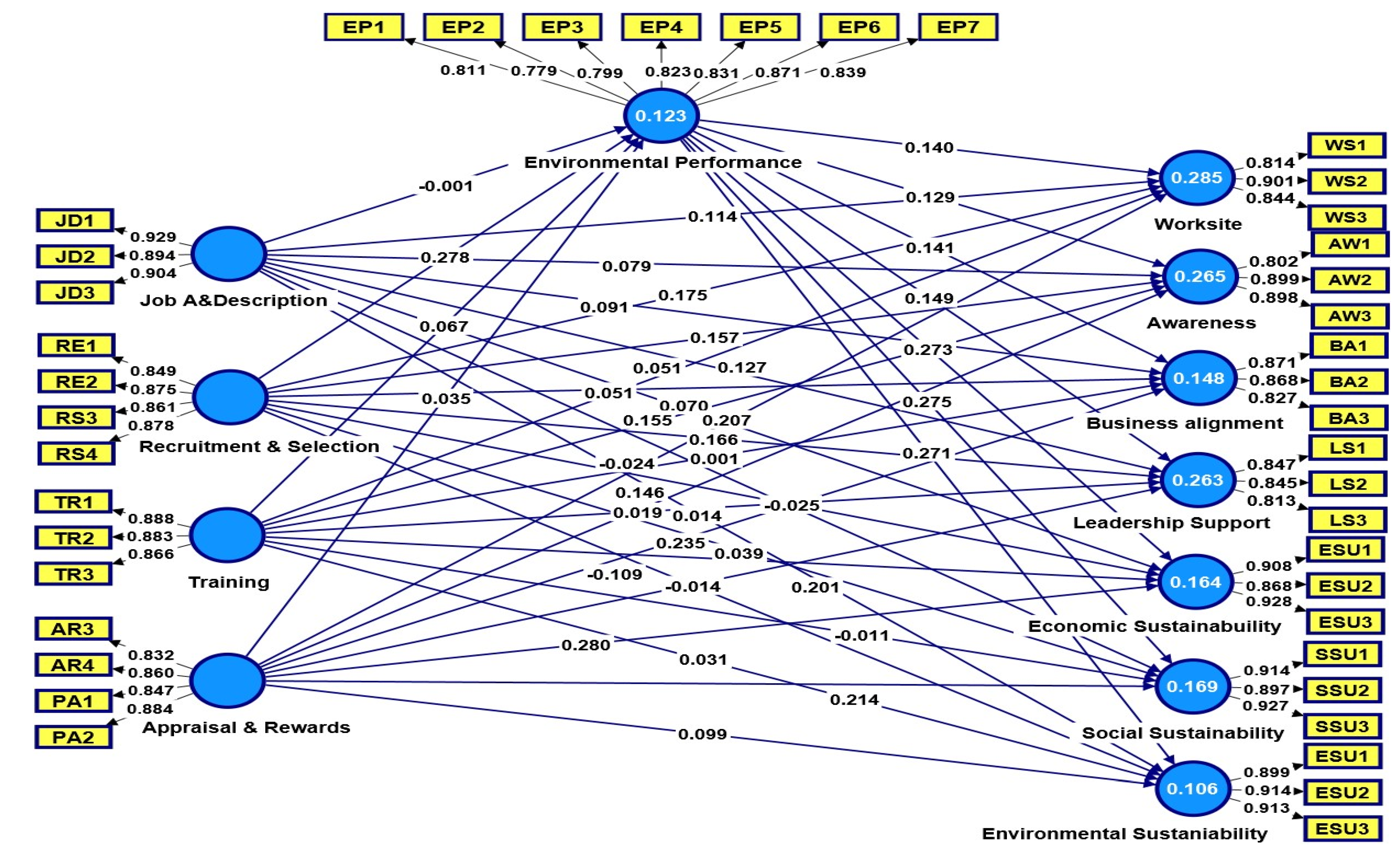

As seen in

Table 3 and Figure 1, the findings demonstrated that the values of α, CR, and rho-A values are higher than the cut-off value of 0.70. (Hair et al., 2021). In addition, The AVE’s values for all constructs are greater than the critical minimum value of 0.50. At the same time, the items’ loading values are higher than the minimum cut-off value of 0.70. Based on this, it can be concluded that the internal consistency and convergent reliability of the FOC are sufficiently established.

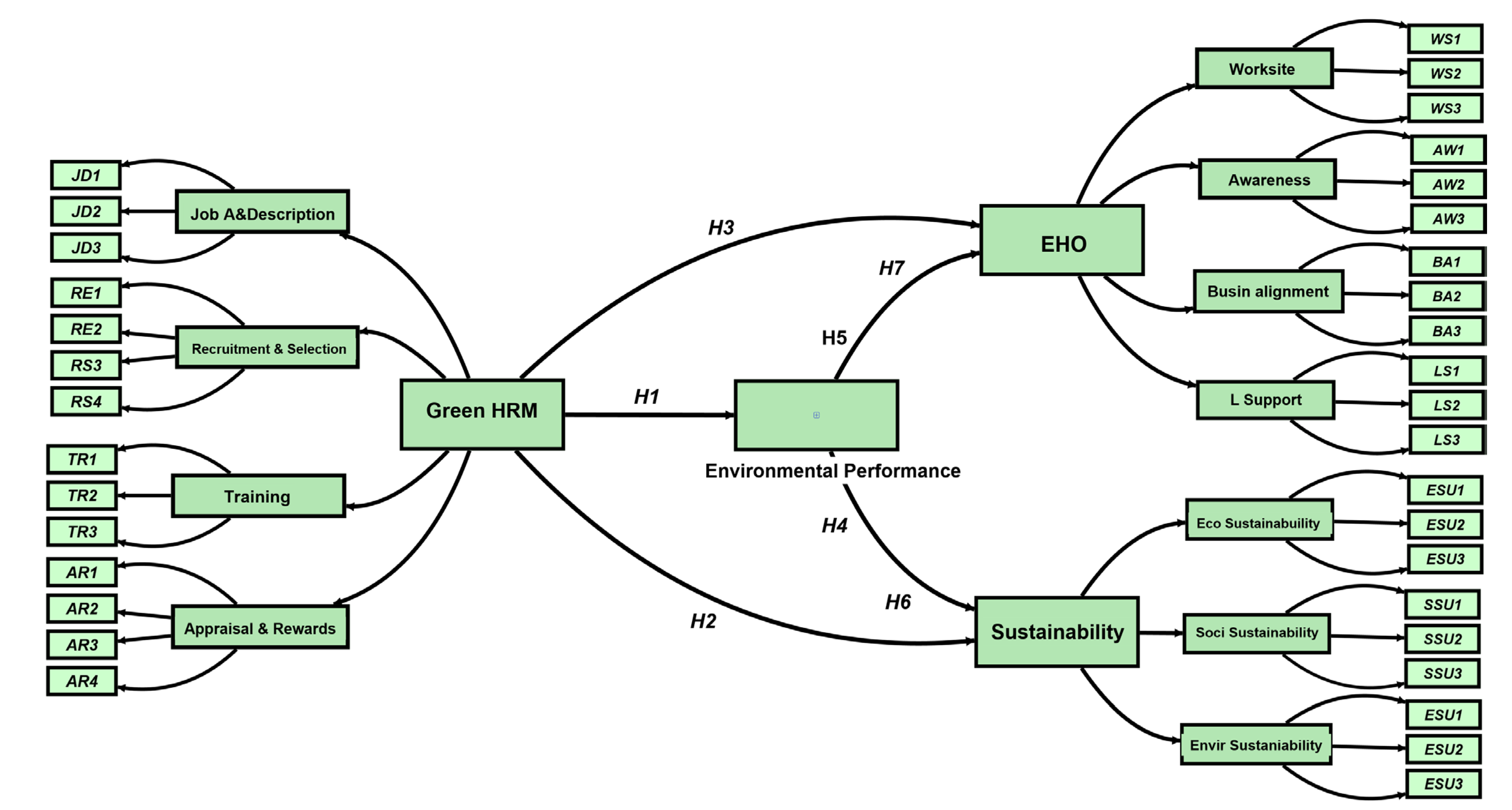

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

Figure 1.

The conceptual framework.

In the second step, the discriminant validity was assessed by employing Fornell and Larcker (1981) criteria as well as the Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) (Henseler et al., 2015). As seen in Table. 3 the findings exhibit that AVE’s square root values for all constructs located in the diagonal place are higher than their correlations with relevant constructs. Also, as seen in Table. 4, the values of the HTMT for the model’s constructs are lower than the 0.85 critical value. This implies that discriminant validity is established for the FOC (Hair et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

The measurement model of the FOC.

Figure 1.

The measurement model of the FOC.

5.1.2. Second-Order Measurement Model Assessment

Similar to assessing the FOCs’ internal consistency reliability and convergent and discriminant validity, the second-order model was evaluated. As shown in

Table 5 and Figure 2, the statistics values α, CR and rho-A overreach the cut-off value of 0.70. Moreover, all AVE's values overreach the minimum critical value of 0.5. In addition, the loading values of the SOCs’ indicators are higher than the cut-off value of 0.70. Based on this, it can be concluded that the internal consistency and convergent reliability of the SOC are established.

In the second step, the discriminant validity for the SOC was assessed. As seen in

Table 6, the AVE’s square root values were found to be higher than the relevant correlations of the constructs. In addition, the results of HTMT show that all its values are less than the cut-off value of 0.85 (See

Table 7). This suggests that discriminant validity is established for the SOCs.

Figure 1.

The measurement model of the SOC.

Figure 1.

The measurement model of the SOC.

5.2. The Structure Model

In order to test the current study’s hypotheses, the bootstrapping technique was employed based on dividing the study sample into 10,000 subsamples and running the same analysis to assess the significance of the relationships in the model (Ringle et al., 2020).

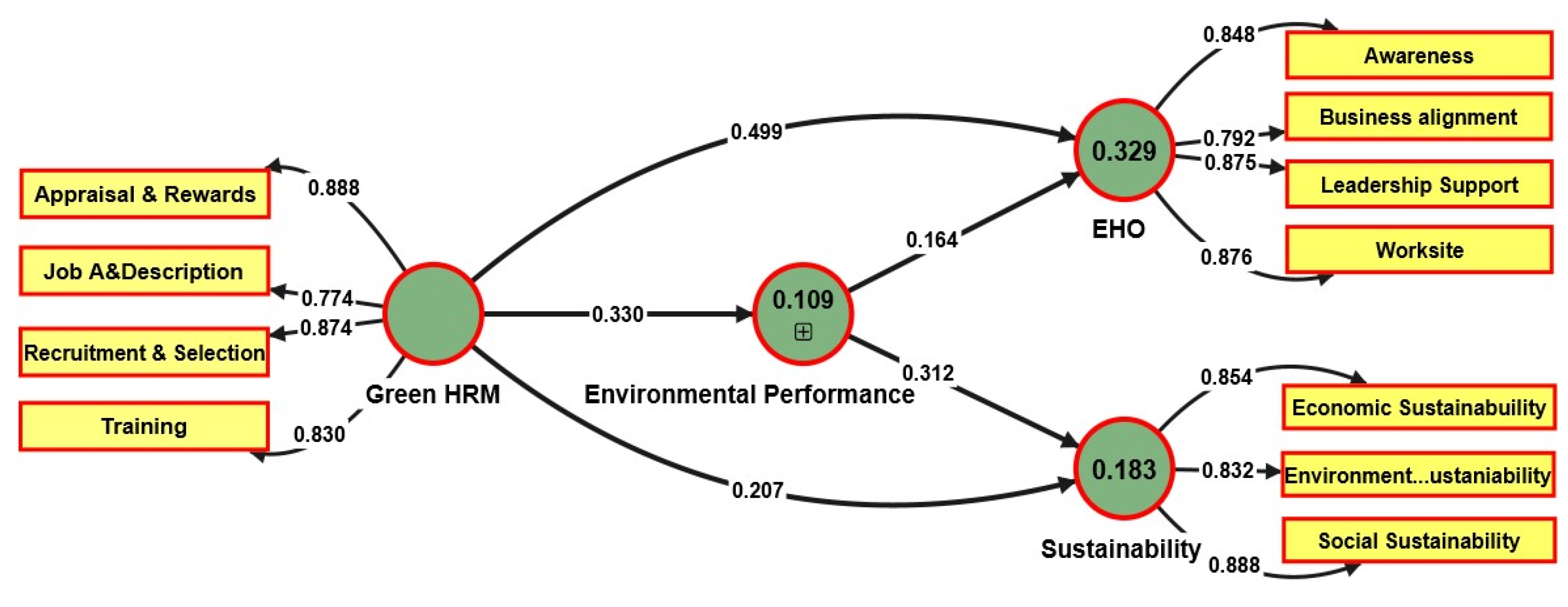

As depicted in

Table 8 and

Figure 3, it is observed that Green HRM practices have positive and significant effects on EP (β=0.330, t-value=6.402, p< 0.000), leading to support the first hypothesis (H1). Furthermore, it was found that Green HRM practices have positive and significant effects on sustainability (β=0.207, t-value=3.229, p< 0.001), leading to support the second hypothesis (H2). Moreover, it was reported that Green HRM practices have positive and significant effects on EHO (β=0.499, t-value=9.766, p< 0.000), supporting the third hypothesis (H3). This leads to the conclusion that Green HRM practices are influential factors among firms concerning EP, sustainability, and EHO.

In addition, it was found that EP has a positive and significant effect on sustainability (β=0.312, t-value=5.133, p< 0.000) and also on EHO (β=0.164, t-value=2.203, p< 0.001) leading to supporting the fourth and fifth hypotheses (H4, H5).

5.3. Mediation Analysis

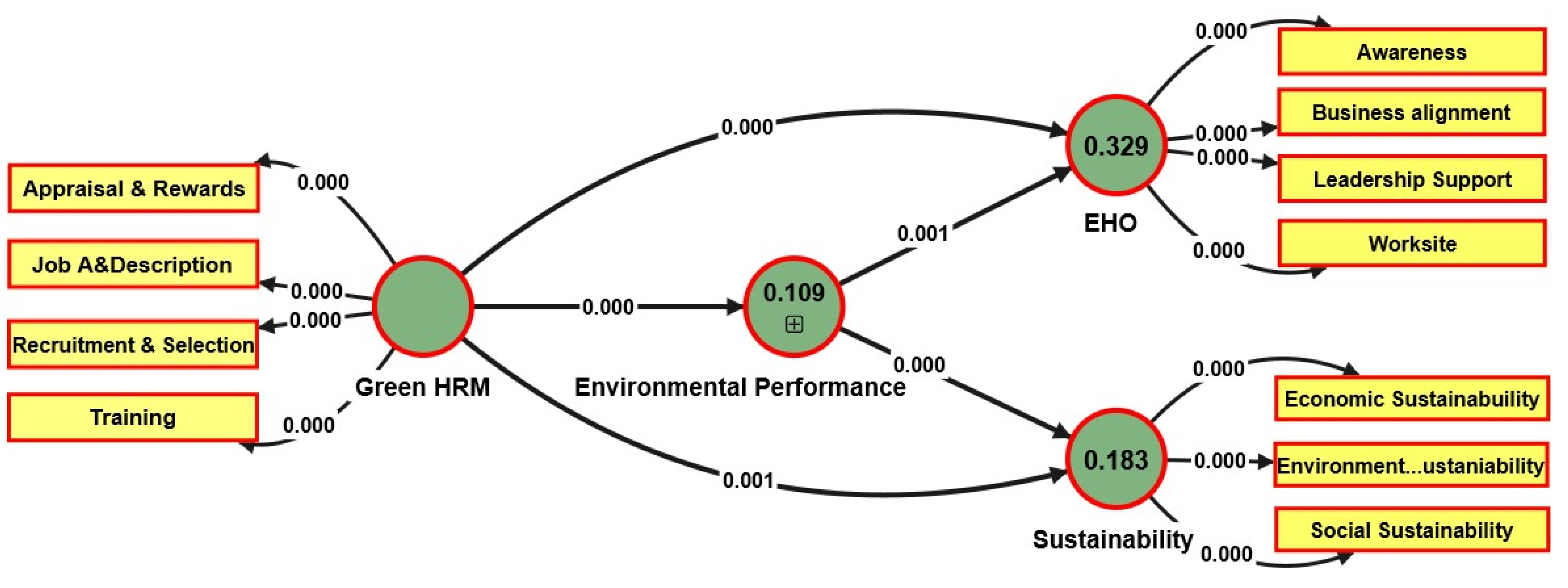

As noticed in

Table 8, the indirect effects of Green HRM practices on sustainability through EP were found to be positive and significant (β=0.103, t-value=3.695, p < 0.000). Moreover, it was seen that the practices of Green HRM have positive and significant indirect effects on EHO through EP (β=0.054, t-value=2.656, p < 0.008). This indicates that the mediating effect of EP exists partially in Green HRM and sustainability and EHO relationship.

Since Green HRM practices affect sustainability and EHO significantly directly, it indicates a partial mediating effect of EP in the link between the practice of Green HRM and EHO and also Sustainability. Thus, H6 and H7 were supported.

5.4. The Explanatory Power of the Model

The explanatory power of the current study model is assessed via the coefficient of determination (R2) (Henseler et al., 2009) for the key endogenous construct in model.

As seen in

Table 10, the results revealed that the R

2value of sustainability is (0.183), indicating weak explanatory power concerning sustainability. Also, the R

2value of EHO is (0.329). This indicates a moderate explanatory power of the study model concerning EHO.

5.5. The Predictive Power of the Model

In order to estimate the model parameter and test the predictive power of the current study model, the PLS

predict procedure was employed via training and holdout samples (Shmueli et al., 2019). As seen in

Table 11, the results revealed that values of Q

2predict for all indicators are found to be positive (>0). Since the key endogenous construct’s prediction error distribution is not symmetric, PLS-SEM mean absolute error (MAE) was used over PLS-SEM, and the root mean squares error (RMSE) was used to compare the key endogenous construct’s prediction errors. The results indicate that PLS-SEM- MAE< LM- MAE for all of the model indicators, which implies a high predictive power of the current study’s model (see

Table 11).

6. Discussion

This study investigates Green HRM practices’ effects on both sustainability and EHO through the mediating effect of EP based on a survey of 318 service and manufacturing firms in India. The results add to the existing body of Green HRM literature by revealing a new relationship between the above-mentioned constructs. In addition, it provides a new understanding of the inconsistency of previous empirical studies' findings concerning the study's constructs.

First, the results of this study are consistent with prior empirical studies, which revealed that the EP is enhanced by the practices of Green HRM (Anwar et al., 2020; Ghouri et al., 2020; Gilal et al., 2019; Mousa & Othman, 2020; Roscoe et al., 2019; Shafaei et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2020; Umrani et al., 2020; Zaid et al., 2018).

Second, this study found that sustainability is impacted by the practices of Green HRM positively and significantly. This is consistent with previous studies (Amjad et al., 2021; Wen et al., 2022), which have found positive and significant effects of the practices of Green HRM on Sustainability. However, the results of this study are not consistent with scholars who have found mixed results where only some dimensions of Green HRM practices affect Sustainability (Jamal et al., 2021; Yong et al., 2020).

Third, this study proposes an important contribution by exploring how Green HRM practices can positively affect EHO. However, our empirical results have established the significant role of Green HRM practices in enhancing EHO. These results are consistent with Shaikh’s (2010) view that Green HRM practices can contribute to EHO. Hence, implementing Green HRM practices can have positive practical consequences on EHO.

Finally, this study explored the mediating effect of EP as an underlying instrument to explain Green HRM practices and sustainability and EHO relationships. The results of the current study revealed that EP mediates Green HRM practices and sustainability relationships. This is consistent with recent research by Amjad et al. (2021). Likewise, the results established the mediating effect of EP in Green HRM practices and the EHO relationship.

7. Practical Contribution

In addition to the theoretical contributions, the empirical findings of the current study present some managerial insights for policy-makers and practitioners to formulate and implement new policies and strategies. this study suggests that manufacturing and service firms need to design, integrate and execute Green HRM practices to orient and foster employees’ mindset towards conserving the environment leading to improving the EP. Moreover, it suggests that active engagement in Green HRM practices ensures that employees are trained and encouraged in sustainable behaviours in the long term. In addition, this study proposes that integrating Green HRM practices into jobs can have a positive impact on EHO as they enable firms to design better policies and align them with overall business strategies in an effort to increase the awareness of employees about their health and safety. Theis leads to improving employee health and safety and reducing healthcare costs, and further performing better in terms of productivity and become preferred employers for talented workers. Additionally, to achieve a better level of sustainability and EHO, it is imperative for firms to improve EP.

8. Research Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Despite this study’s contributions, it has a number of limitations that could be addressed in future studies.

First, this study was based on cross-sectional, which limits the capacity to establish causality in the links among its constructs. Therefore, to achieve precise results, a longitudinal study is recommended. Second, the sample of this study focused on Indian manufacturing and service organisations. The findings, therefore, cannot be generalised to organisations in other regions and cultures. Hence, scholars can validate the findings of this study in different organisations in any part of the world. Finally, a comparative study between service and manufacturing organisations could also be conducted.

References

- Ahmad, S. Green human resource management: Policies and practices. Cogent Business & Management 2015, 2, 1030817. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, U.; AlZgool MR, H.; Shah, S.M.M. The impact of green human resource practices on environmental sustainability. Polish Journal of Management Studies 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S.; Zhang, J.; Shehzad, M.U.; Boamah, F.A.; Wang, B. The inclusive analysis of green technology implementation impacts on employees age, job experience, and size in manufacturing firms: Empirical assessment. Environment, Development and Sustainability 2023, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hawari, M.A.; Quratulain, S.; Melhem, S.B. How and when frontline employees’ environmental values influence their green creativity? Examining the role of perceived work meaningfulness and green HRM practices. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 310, 127598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amjad, F.; Abbas, W.; Zia-UR-Rehman, M.; Baig, S.A.; Hashim, M.; Khan, A.; Rehman, H. Effect of green human resource management practices on organizational sustainability: the mediating role of environmental and employee performance. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2021, 28, 28191–28206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amrutha, V.N.; Geetha, S.N. A systematic review on green human resource management: Implications for social sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 247, 119131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, N.; Mahmood NH, N.; Yusliza, M.Y.; Ramayah, T.; Faezah, J.N.; Khalid, W. Green Human Resource Management for organisational citizenship behaviour towards the environment and environmental performance on a university campus. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 256, 120401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulrajah, A.A.; Opatha, H.; Nawaratne, N.N.J. Green human resource management practices: A review. 2015.

- Awan, F.H.; Dunnan, L.; Jamil, K.; Gul, R.F. Stimulating environmental performance via green human resource management, green transformational leadership, and green innovation: a mediation-moderation model. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 2958–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayayi, A.G.; Wijesiri, M. Is there a trade-off between environmental performance and financial sustainability in microfinance institutions? Evidence from South and Southeast Asia. Business Strategy and the Environment 2022, 31, 1552–1565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, S.; Mani, S.P.; Gupta, H.; Maurya, S. Sustainable development of the green bond markets in India: Challenges and strategies. Sustainable Development 2023, 31, 237–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baral, M.M.; Rao UV, A.; Rao, K.S.; Dey, G.C.; Mukherjee, S.; Kumar, M.A. Achieving Sustainability of SMEs Through Industry 4.0-Based Circular Economy. International Journal of Global Business and Competitiveness 2023, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management 1991, 17, 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Is the resource-based “view” a useful perspective for strategic management research? Yes. Academy of Management Review 2001, 26, 41–56. [Google Scholar]

- Beehr, T.A.; Newman, J.E. Job stress, employee health, and organizational effectiveness: A facet analysis, model, and literature review 1. Personnel Psychology 1978, 31, 665–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-M.; Kuo, T.-C.; Chen, J.-L. Impacts on the ESG and financial performances of companies in the manufacturing industry based on the climate change related risks. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 380, 134951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daily, B.F.; Bishop, J.W.; Steiner, R. The mediating role of EMS teamwork as it pertains to HR factors and perceived environmental performance. Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 2007, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.C.; Singh, R.K. Green HRM and organizational sustainability: An empirical review. Kegees Journal of Social Science 2016, 8, 227–236. [Google Scholar]

- de Castro Hilsdorf, W.; de Mattos, C.A.; de Campos Maciel, L.O. Principles of sustainability and practices in the heavy-duty vehicle industry: A study of multiple cases. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 141, 1231–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della, L.J.; DeJoy, D.M.; Goetzel, R.Z.; Ozminkowski, R.J.; Wilson, M.G. Assessing management support for worksite health promotion: psychometric analysis of the leading by example (LBE) instrument. American Journal of Health Promotion 2008, 22, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, J.; Shen, J.; Deng, X. Effects of green HRM practices on employee workplace green behavior: The role of psychological green climate and employee green values. Human Resource Management 2017, 56, 613–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutta, D. Greening people: A strategic dimension. ZENITH International Journal of Business Economics & Management Research 2012, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Elkington, J. Towards the sustainable corporation: Win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. California Management Review 1994, 36, 90–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. Governance for sustainability. Corporate Governance: An International Review 2006, 14, 522–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elshaer, I.A.; Sobaih AE, E.; Aliedan, M.; Azazz AM, S. The effect of green human resource management on environmental performance in small tourism enterprises: mediating role of pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. (1984). Strategic management: a stakeholder approach, Pitman. Boston, MA.

- Geng, L.; Lu, X.; Zhang, C. The Theoretical Lineage and Evolutionary Logic of Research on the Environmental Behavior of Family Firms: A Literature Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 4768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gericke, N.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Berglund, T.; Olsson, D. The Sustainability Consciousness Questionnaire: The theoretical development and empirical validation of an evaluation instrument for stakeholders working with sustainable development. Sustainable Development 2019, 27, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghouri, A.M.; Mani, V.; Khan, M.R.; Khan, N.R.; Srivastava, A.P. Enhancing business performance through green human resource management practices: an empirical evidence from Malaysian manufacturing industry. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilal, F.G.; Ashraf, Z.; Gilal, N.G.; Gilal, R.G.; Channa, N.A. Promoting environmental performance through green human resource management practices in higher education institutions: A moderated mediation model. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2019, 26, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, S.K.; Saranga, H. Pressure or premium: what works best where? Antecedents and outcomes of sustainable manufacturing practices. International Journal of Production Research 2020, 58, 7201–7217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Y. (2023). Environmental performance and employee welfare: Evidence from health benefit costs. International Review of Finance.

- Gupta, V.; Santosh, K.C.; Arora, R.; Ciano, T.; Kalid, K.S.; Mohan, S. Socioeconomic impact due to COVID-19: An empirical assessment. Information Processing & Management 2022, 59, 102810. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult GT, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Sage publications. 2021.

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; Kuppelwieser, V.G. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. European Business Review. 2014.

- Hair, J., Jr.; Hult, F.; GTM, R.C.; Sarstedt, M. (2017). A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM)(ed.) Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks.

- Han, Z.; Huo, B. The impact of green supply chain integration on sustainable performance. Industrial Management & Data Systems 2020, 120, 657–674. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. (2009). The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New challenges to international marketing. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Ikram, M.; Zhou, P.; Shah, S.A.A.; Liu, G.Q. Do environmental management systems help improve corporate sustainable development? Evidence from manufacturing companies in Pakistan. Journal of Cleaner Production 2019, 226, 628–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q. The era of environmental sustainability: Ensuring that sustainability stands on human resource management. Global Business Review 2020, 21, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbar, M.H.; Abid, M. A study of green HR practices and its impact on environmental performance: A review. Management Research Report 2015, 3, 142–154. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, C.J.C.; Santos, F.C.A.; Nagano, M.S. Contributions of HRM throughout the stages of environmental management: methodological triangulation applied to companies in Brazil. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2010, 21, 1049–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, S.E.; Renwick, D.W.S.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Muller-Camen, M. State-of-the-art and future directions for green human resource management: Introduction to the special issue. German Journal of Human Resource Management 2011, 25, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamal, T.; Zahid, M.; Martins, J.M.; Mata, M.N.; Rahman, H.U.; Mata, P.N. Perceived green human resource management practices and corporate sustainability: multigroup Analysis and major industries perspectives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerónimo, H.M.; Henriques, P.L.; de Lacerda, T.C.; da Silva, F.P.; Vieira, P.R. Going green and sustainable: The influence of green HR practices on the organizational rationale for sustainability. Journal of Business Research 2020, 112, 413–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, S. Bringing power and time in: How do the role of government and generation matter for environmental policy support? Energy Strategy Reviews 2022, 42, 100894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.J.; Kim, W.G.; Choi, H.-M.; Phetvaroon, K. The effect of green human resource management on hotel employees’ eco-friendly behavior and environmental performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2019, 76, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common method bias in PLS-SEM: A full collinearity assessment approach. International Journal of E-Collaboration (Ijec) 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N.; Lynn, G. Lateral collinearity and misleading results in variance-based SEM: An illustration and recommendations. Journal of the Association for Information Systems 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, C.; Chung, N.; Ryoo, S.Y. How does ecological responsibility affect manufacturing firms’ environmental and economic performance? Total Quality Management & Business Excellence 2014, 25, 1171–1189. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, C.M.S.; Singh, S.; Gupta, M.K.; Nimdeo, Y.M.; Raushan, R.; Deorankar, A.V.; Kumar, T.M.A.; Rout, P.K.; Chanotiya, C.S.; Pakhale, V.D. Solar energy: A promising renewable source for meeting energy demand in Indian agriculture applications. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2023, 55, 102905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuuyelleh, E.N.; Ayentimi, D.T.; Ali Abadi, H. Green People Management, Internal Communications and Employee Engagement. Green Marketing and Management in Emerging Markets: The Crucial Role of People Management in Successful Implementation 2021, 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Chen, S.; Gao, Z.; Chen, X. (2023). Assessing the impact of corporate environmental performance on efficiency improvement in labor investment. Business Strategy and the Environment.

- Mahdy, F.; Alqahtani, M.; Binzafrah, F. Imperatives, Benefits, and Initiatives of Green Human Resource Management (GHRM): A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2023, 15, 4866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.Y.; Cao, Y.; Mughal, Y.H.; Kundi, G.M.; Mughal, M.H.; Ramayah, T. Pathways towards sustainability in organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management practices and green intellectual capital. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Margaretha, M.; Saragih, S. Developing new corporate culture through green human resource practice. International Conference on Business, Economics, and Accounting 2013, 1.

- Masri, H.A.; Jaaron, A.A.M. Assessing green human resources management practices in Palestinian manufacturing context: An empirical study. , 143, 474–489. Journal of Cleaner Production 2017, 143, 474–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melnyk, S.A.; Sroufe, R.P.; Calantone, R. Assessing the impact of environmental management systems on corporate and environmental performance. Journal of Operations Management 2003, 21, 329–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, S.K.; Othman, M. The impact of green human resource management practices on sustainable performance in healthcare organisations: A conceptual framework. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 243, 118595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mtembu, V. Does having knowledge of green human resource management practices influence its implementation within organizations?

Problems and Perspectives in Management 2019, 17, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Asad, N.; Hashmi, H.B.A.; Fu, H.; Abbass, K. Analyzing the pro-environmental behavior of pharmaceutical employees through Green HRM practices: The mediating role of green commitment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 7886–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawangsari, L.C.; Sutawidjaya, A.H. (2019). How the Green Human Resources Management (GHRM) Process Can Be Adopted for the Organization Business? 1st International Conference on Economics, Business, Entrepreneurship, and Finance (ICEBEF 2018), 463–465.

- Nguyen, H.T.T.; Bui, L.T.B.; Tran, K.T.; Tran, M.D.T.; Nguyen, K.V.; Bui, H.M. The toxic waste management towards corporates’ sustainable development: A causal approach in Vietnamese industry. Environmental Technology & Innovation 2023, 103186. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T.H.H.; Elmagrhi, M.H.; Ntim, C.G.; Wu, Y. Environmental performance, sustainability, governance and financial performance: Evidence from heavily polluting industries in China. Business Strategy and the Environment 2021, 30, 2313–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, T. The impact of green recruitment, green training and green learning on the firm performance: conceptual paper. International Journal of Applied Research 2015, 1, 951–953. [Google Scholar]

- Obeidat, S.M.; Al Bakri, A.A.; Elbanna, S. Leveraging “green” human resource practices to enable environmental and organizational performance: Evidence from the Qatari oil and gas industry. Journal of Business Ethics 2020, 164, 371–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owino, W.A.; Kwasira, J. Influence of selected green human resource management practices on environmental sustainability at Menengai Oil Refinery Limited Nakuru, Kenya. Journal of Human Resource Management 2016, 4, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé, P.; Chen, Y.; Boiral, O.; Jin, J. The impact of human resource management on environmental performance: An employee-level study. Journal of Business Ethics 2014, 121, 451–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paillé; P. ; Valéau, P.; Renwick, D.W. Leveraging green human resource practices to achieve environmental sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020, 260, 121137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.T.; Thanh, T.V.; Tučková, Z.; Thuy, V.T.N. The role of green human resource management in driving hotel’s environmental performance: Interaction and mediation analysis. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2020, 88, 102392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P.M.; MacKenzie, S.B.; Lee, J.-Y.; Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 2003, 88, 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, S. (2023). Initiatives on Climate Change Mitigation. In Climate, Land-Use Change and Hydrology of the Beas River Basin, Western Himalayas (pp. 177–202). Springer.

- Rani, S.; Mishra, K. Green HRM: Practices and strategic implementation in the organizations. International Journal on Recent and Innovation Trends in Computing and Communication 2014, 2, 3633–3639. [Google Scholar]

- Rawashdeh, A. The impact of green human resource management on organizational environmental performance in Jordanian health service organizations. Management Science Letters 2018, 8, 1049–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razab, M.F.; Udin, Z.M.; Osman, W.N. Understanding the role of GHRM towards environmental performance. Journal of Global Business and Social Entrepreneurship (GBSE) 2015, 1, 118–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; Tang, G.; EJackson, S. Green human resource management research in emergence: A review and future directions. Asia Pacific Journal of Management 2018, 35, 769–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renwick, D.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green HRM: A review, process model, and research agenda. University of Sheffield Management School Discussion Paper 2008, 1, 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Renwick, D.W.S.; Redman, T.; Maguire, S. Green human resource management: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Management Reviews 2013, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Mitchell, R.; Gudergan, S.P. Partial least squares structural equation modeling in HRM research. The International Journal of Human Resource Management 2020, 31, 1617–1643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roscoe, S.; Subramanian, N.; Jabbour, C.J.C.; Chong, T. Green human resource management and the enablers of green organisational culture: Enhancing a firm’s environmental performance for sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment 2019, 28, 737–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubel, M.R.B.; Kee, D.M.H.; Rimi, N.N. Green human resource management and supervisor pro-environmental behavior: The role of green work climate perceptions. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 313, 127669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed BBin Afsar, B.; Hafeez, S.; Khan, I.; Tahir, M.; Afridi, M.A. Promoting employee’s proenvironmental behavior through green human resource management practices. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 2019, 26, 424–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, S. Lean practices and operational performance: the role of organizational culture. International Journal of Quality & Reliability Management 2022, 39, 428–467. [Google Scholar]

- Scalia, M.; Barile, S.; Saviano, M.; Farioli, F. Governance for sustainability: A triple-helix model. Sustainability Science 2018, 13, 1235–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafaei, A.; Nejati, M.; Yusoff, Y.M. Green human resource management: A two-study investigation of antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Manpower. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, M. Green HRM: A requirement of 21st century. Journal of Research in Commerce and Management 2010, 1, 122–127. [Google Scholar]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using PLSpredict. European Journal of Marketing. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Del Giudice, M.; Chierici, R.; Graziano, D. Green innovation and environmental performance: The role of green transformational leadership and green human resource management. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 2020, 150, 119762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siyambalapitiya, J.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Green human resource management: A proposed model in the context of Sri Lanka’s tourism industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 201, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, G.; McLellan, D.; Dennerlein, J.T.; Pronk, N.P.; Allen, J.D.; Boden, L.I.; Okechukwu, C.A.; Hashimoto, D.; Stoddard, A.; Wagner, G.R. Integration of health protection and health promotion: rationale, indicators, and metrics. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine/American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2013, 55, S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Dharwal, M.; Sharma, A. Green financial initiatives for sustainable economic growth: a literature review. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 49, 3615–3618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suharti, L.; Sugiarto, A. A qualitative study OF Green HRM practices and their benefits in the organization: An Indonesian company experience. Business: Theory and Practice 2020, 21, 200–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujatha, R.; Basu, S. Human resource dimensions for environment management system: evidences from two Indian fertilizer firms. European Journal of Business and Management 2013, 5, 2222–2839. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, R.; Sharma, Y. Public policies to promote renewable energy technologies: Learning from Indian experiences. Materials Today: Proceedings 2022, 49, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, V.; Jham, J. Corporate environmental performance and stock market performance: Indian evidence on disaggregated measure of sustainability. Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance 2020, 31, 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Úbeda-García, M.; Claver-Cortés, E.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Zaragoza-Sáez, P. Corporate social responsibility and firm performance in the hotel industry. The mediating role of green human resource management and environmental outcomes. Journal of Business Research 2021, 123, 57–69. [Google Scholar]

- Umrani, W.A.; Channa, N.A.; Yousaf, A.; Ahmed, U.; Pahi, M.H.; Ramayah, T. Greening the workforce to achieve environmental performance in hotel industry: A serial mediation model. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2020, 44, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, S.; Sueyoshi, T. DEA environmental assessment on US Industrial sectors: Investment for improvement in operational and environmental performance to attain corporate sustainability. Energy Economics 2014, 45, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, J.; Hussain, H.; Waheed, J.; Ali, W.; Jamil, I. Pathway toward environmental sustainability: mediating role of corporate social responsibility in green human resource management practices in small and medium enterprises. International Journal of Manpower 2022, 43, 701–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wendling, Z.A.; Jacob, M.; Esty, D.C.; Emerson, J.W. Explaining environmental performance: Insights for progress on sustainability. Environmental Development 2022, 44, 100741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, T.A.; Wright, V.P. Organizational researcher values, ethical responsibility, and the committed-to-participant research perspective. Journal of Management Inquiry 2002, 11, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards sustainability in manufacturing organizations: Empirical evidence on the role of green human resource management. Business Strategy and the Environment 2020, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.-Y.; Fawehinmi, O.O. Green human resource management: A systematic literature review from 2007 to 2019. Benchmarking: An International Journal.

- Yusoff, Y.M.; Nejati, M.; Kee, D.M.H.; Amran, A. Linking green human resource management practices to environmental performance in hotel industry. Global Business Review 2020, 21, 663–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaid, A.A.; Bon, A.T.; Jaaron, A.A. Green human resource management bundle practices and manufacturing organizations for performance optimization: a conceptual model. International Journal of Engineering & Technology 2018, 7, 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch Jr, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research 2010, 37, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zighan, S.; Abuhussein, T.; Al-Zu’bi, Z.; Dwaikat, N.Y. (2023). A qualitative exploration of factors driving sustainable innovation in small-and medium-sized enterprises in Jordan. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy.

- Zoogah, D.B. The dynamics of Green HRM behaviors: A cognitive social information processing approach. German Journal of Human Resource Management 2011, 25, 117–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).