Submitted:

13 May 2024

Posted:

14 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Crisis Management

2.2. Crisis Management and Mobile Government

2.3. Moderating Effect (Role) of Techno-Skepticism

2.3.1. Techno-Skepticism

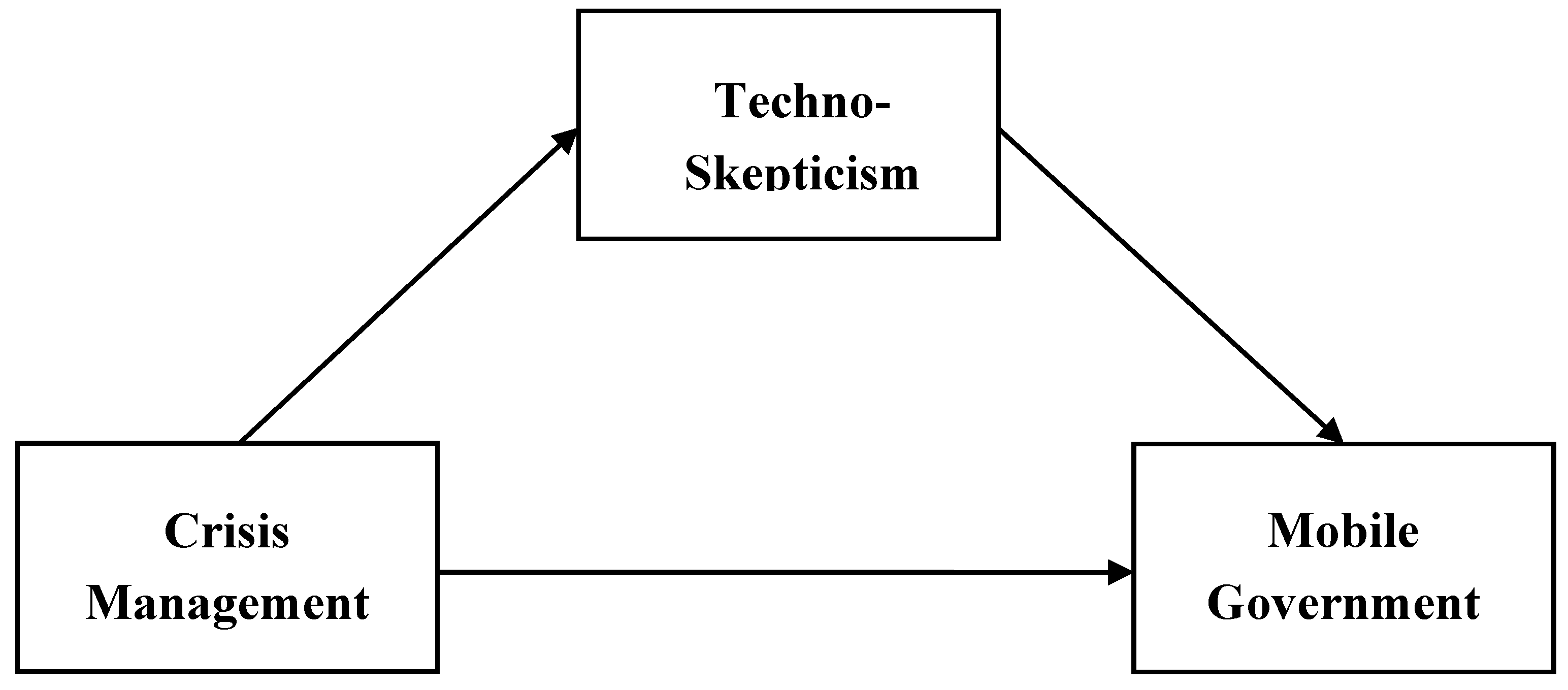

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Research Questions

3.2. Research Model

3.3. Measurement Scale

3.4. Pilot Test

3.5. Data Collection

3.6. Measures

3.7. Measurement Tools

3.8. Crisis Management

3.9. Mobile Government

3.10. Techno-Skepticism

4. Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusion and Future Directions

7. Implications

7.1. Theoretical Implications

7.2. Political Implications

7.3. Practical Implications

8. Limitations

Conflicts of Interest

References

- C. ZAFER and P. VARDARLIER, “Toplumsal Gürültüden Toplumsal Hareketlere Sosyal Medyanın Rolü: Arap Baharı ve Gezi Parkı Olayları Örneği,” Afyon Kocatepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 379–390, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.32709/akusosbil.472857. [CrossRef]

- N. M. Ochara and T. Mawela, “Enabling Social Sustainability of E-Participation through Mobile Technology,” Inf Technol Dev, vol. 21, no. 2, pp. 205–228, Apr. 2015, doi: 10.1080/02681102.2013.833888. [CrossRef]

- H. Chourabi et al., “Understanding smart cities: An integrative framework,” in Proceedings of the Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, IEEE Computer Society, 2012, pp. 2289–2297. doi: 10.1109/HICSS.2012.615. [CrossRef]

- S. Bilimi, K. Yönetimi, A. Dalı, B. Dalı, and U. T. Curaci, “Hacettepe Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü E-DEVLET ARAŞTIRMA MERKEZLERİNİN İNCELENMESİ: TÜRKİYE İÇİN BİR MODEL ÖNERİSİ.”.

- M. Moore, “Promoting Good Government by Supporting Institutional Development?,” IDS Bull, vol. 26, no. 2, pp. 89–96, 1995, doi: 10.1111/j.1759-5436.1995.mp26002010.x. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Talbot, “Competing Public Values and Performance,” 2017. [Online]. Available: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/314686976.

- M. H. Moore, “Managing for Value: Organizational Strategy in ‘For-Profit,’ ‘Non-Profit’ and Governmental Organizations.”.

- N. E. Üniversitesi et al., “SİYASET, EKONOMİ ve YÖNETİM ARAŞTIRMALARI DERGİSİ G-7 ve G-20 Ülkelerinde İyi Yönetişim Nasıl Olmalı?: Teorik Bir Değerlendirme How Should Good Governance Be In The G7 and G20 Countries?: A Theoretical Review Mine IŞIK,” vol. 6, no. 5, p. 5, 2018, [Online]. Available: www.siyasetekonomiyonetim.org.

- H. Gül and F. Çelebi, “Koronavirüs (Covid-19) Pandemisinde Başlıca Gelişmiş ve Gelişmekte Olan Ülkelerde Kriz Yönetiminin Değerlendirilmesi”, [Online]. Available: https://rega.kuleuven.be.

- D. K. Ahorsu, C. Y. Lin, V. Imani, M. Saffari, M. D. Griffiths, and A. H. Pakpour, “The Fear of COVID-19 Scale: Development and Initial Validation,” Int J Ment Health Addict, vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 1537–1545, Jun. 2022, doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00270-8. [CrossRef]

- Kushchu, “Positive Contributions of Mobile Phones to Society.” [Online]. Available: www.mgovernment.org.

- D. Ishmatova and T. Obi, “m-Government Services: User Needs and Value,” I-WAYS, Digest of Electronic Commerce Policy and Regulation, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 39–46, 2009, doi: 10.3233/iwa-2009-0163. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang and T. S. H. Teo, “Online service quality and perceived value in mobile government success: An empirical study of mobile police in China,” Int J Inf Manage, vol. 52, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102076. [CrossRef]

- “[ Hakemsiz Yazılar J Freelance Articles.”.

- “Bilgi Teknolojileri ve Haberleşme Kurumu | BTHK.” Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.bthk.org/tr.

- M. Akdağ, “HALKLA İLİŞKİLER VE KRİZ YÖNETİMİ *.”.

- “17”.

- M. Abdalla, L. Alarabi, and A. Hendawi, “Crisis management art from the risks to the control: A review of methods and directions,” Information (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 1. MDPI AG, pp. 1–13, Jan. 01, 2021. doi: 10.3390/info12010018. [CrossRef]

- M. Akdağ, “HALKLA İLİŞKİLER VE KRİZ YÖNETİMİ *.

- C. Lemonakis and A. Zairis, “Crisis Management and the Public Sector: Key Trends and Perspectives.” [Online]. Available: www.intechopen.com.

- “21”.

- “22”.

- U. Rosenthal and A. Kouzmin, “1993); international and domestic disruptions in the delivery of 2771,” 1997. [Online]. Available: http://jpart.oxfordjournals.org/.

- S. Erten, G. Bebek, and M. Koyutürk, “Vavien: An algorithm for prioritizing candidate disease genes based on topological similarity of proteins in interaction networks,” Journal of Computational Biology, vol. 18, no. 11, pp. 1561–1574, Nov. 2011, doi: 10.1089/cmb.2011.0154. [CrossRef]

- “25”.

- “KKTC e-Devlet Kapısı.” Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://edevlet.gov.ct.tr/.

- V. Burksiene, J. Dvorak, and M. Duda, “Upstream social marketing for implementing mobile government,” Societies, vol. 9, no. 3, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.3390/soc9030054. [CrossRef]

- E. Goyal and S. Purohit, “Using moodle to enhance student satisfaction from ICT,” in Proceedings - IEEE International Conference on Technology for Education, T4E 2011, 2011, pp. 191–198. doi: 10.1109/T4E.2011.37. [CrossRef]

- H. Sheng, F. Hall, S. Trimi CBA, H. Sheng, and S. Trimi, “XXXX Electronic Government.”.

- I. Almarashdeh and M. K. Alsmadi, “How to make them use it? Citizens acceptance of M-government,” Applied Computing and Informatics, vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 194–199, Jul. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.aci.2017.04.001. [CrossRef]

- M. Mpinganjira, “Online Store Service Convenience, Customer Satisfaction and Behavioural Intentions: A Focus on Utilitarian Oriented Shoppers,” Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies, vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 36–49, 2015.

- S. K. Saha, P. Duarte, S. C. Silva, and G. Zhuang, “The Role of Online Experience in the Relationship Between Service Convenience and Future Purchase Intentions,” Journal of Internet Commerce, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 244–271, 2023, doi: 10.1080/15332861.2022.2045767. [CrossRef]

- H. S. Al-Hubaishi, S. Z. Ahmad, and M. Hussain, “Assessing M-Government Application Service Quality and Customer Satisfaction,” Journal of Relationship Marketing, vol. 17, no. 3, pp. 229–255, Jul. 2018, doi: 10.1080/15332667.2018.1492323. [CrossRef]

- F. Shahzad, G. Y. Xiu, I. Khan, and J. Wang, “m-Government Security Response System: Predicting Citizens’ Adoption Behavior,” Int J Hum Comput Interact, vol. 35, no. 10, pp. 899–915, Jun. 2019, doi: 10.1080/10447318.2018.1516844. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Sharma, A. Al-Badi, N. P. Rana, and L. Al-Azizi, “Mobile applications in government services (mG-App) from user’s perspectives: A predictive modelling approach,” Gov Inf Q, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 557–568, Oct. 2018, doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2018.07.002. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Shareef, V. Kumar, U. Kumar, and Y. K. Dwivedi, “E-Government Adoption Model (GAM): Differing service maturity levels,” Gov Inf Q, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 17–35, Jan. 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.05.006. [CrossRef]

- ““Embedding Neoliberalism: Global Health and the Evolution of the Global Intellectual Property Regime,” 1995.

- S. Moon, “WHO’s role in the global health system: What can be learned from global R&D debates?,” Public Health, vol. 128, no. 2. pp. 167–172, Feb. 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.014. [CrossRef]

- R. Online, A. Aloudat, K. Michael, J. Yan, and A. Aloudat, “Location-Based Services in Emergency Management-from Government to Location-Based Services in Emergency Management-from Government to Citizens: Global Case Studies Citizens: Global Case Studies Location-Based Services in Emergency Management-from Government to Location-Based Services in Emergency Management-from Government to Citizens: Global Case Studies Citizens: Global Case Studies Location-Based Services in Emergency Management-from Government to Citizens: Global Case Studies,” 2007. [Online]. Available: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers.

- T. Isagah and M. A. Wimmer, “Mobile government applications: Challenges and needs for a comprehensive design approach,” ACM International Conference Proceeding Series, vol. Part F128003, pp. 423–432, Mar. 2017, doi: 10.1145/3047273.3047305. [CrossRef]

- “Thinking through Technology: The Path between Engineering and Philosophy - Carl Mitcham - Google Kitaplar.” Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com.cy/books?hl=tr&lr=&id=0uF-EAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=thinking+through+technology+the+path+between+&ots=Md74BkVsyr&sig=yW-LAXl5pMG5UtpTsamWIxdNehY&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=thinking%20through%20technology%20the%20path%20between&f=false.

- D. Burston, “Remembering The Sane Society: An American Lament,” Psychoanalytic Inquiry, vol. 44, no. 1. Routledge, pp. 116–123, 2024. doi: 10.1080/07351690.2023.2296385. [CrossRef]

- “Love and Its Disintegration,” 1956.

- I. I., “Tools for Conviviality.

- C. Kerschner and M. H. Ehlers, “A framework of attitudes towards technology in theory and practice,” Ecological Economics, vol. 126, pp. 139–151, Jun. 2016, doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.02.010. [CrossRef]

- K. R. Solomon et al., “Ecological risk assessment of atrazine in North American surface waters,” Environ Toxicol Chem, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 31–76, Jan. 1996, doi: 10.1002/etc.5620150105. [CrossRef]

- W. N. Evans and J. D. Graham, “Risk Reduction or Risk Compensation? The Case of Mandatory Safety-Belt Use Laws,” 1991. [Online]. Available: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41760616.

- J. P. Bound and N. Voulvoulis, “Pharmaceuticals in the aquatic environment - A comparison of risk assessment strategies,” Chemosphere, vol. 56, no. 11, pp. 1143–1155, Sep. 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.05.010. [CrossRef]

- H. P. Segal, “Technology, Pessimism, and Postmodernism: Introduction,” Technology, Pessimism, and Postmodernism, pp. 1–10, 1994, doi: 10.1007/978-94-011-0876-8_1. [CrossRef]

- J. Ellul, “The Technological System Translated from the French by Joachim Neugroschel,” 1980.

- A. Feenberg, “Marcuse or Habermas: Two Critiques of Technology 1.

- T. W. Luke, “Citation Classics and Foundational Works ONE-DIMENSIONAL MAN A Systematic Critique of Human Domination and Nature-Society Relations,” 2000.

- “53”.

- A. R. Drengson, “Four Philosophies of Technology.

- P. Ariès, “Décroissance ou barbarie.

- B. G. Baykan, “From limits to growth to degrowth within French green politics,” Env Polit, vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 513–517, Jun. 2007, doi: 10.1080/09644010701251730. [CrossRef]

- G. Kallis, C. Kerschner, and J. Martinez-Alier, “The economics of degrowth,” Ecological Economics, vol. 84. pp. 172–180, Dec. 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.017. [CrossRef]

- S. 1940- Latouche, “Sobrevivir al desarrollo : de la descolonización del imaginario económico a la construcción de una sociedad alternativa,” 2007, Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://icariaeditorial.com/mas-madera/3781-sobrevivir-al-desarrollo-de-la-descolonizacion-del-imaginario-economico-a-la-construccion-de-una-sociedad-alternativa.html.

- T. F. H. Allen, J. A. Tainter, and T. W. Hoekstra, “Supply-Side Sustainability,” Supply-Side Sustainability, Dec. 2003, doi: 10.7312/ALLE10586/HTML. [CrossRef]

- J. A. Tainter, “Problem Solving: Complexity, History, Sustainability.

- A. H. Sorman and M. Giampietro, “The energetic metabolism of societies and the degrowth paradigm: Analyzing biophysical constraints and realities,” J Clean Prod, vol. 38, pp. 80–93, Jan. 2013, doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.11.059. [CrossRef]

- S. Llorens Gumbau, M. Salanova Soria, and M. Ventura Campos, “Efectos del tecnoestrés en las creencias de eficacia y el burnout docente: un estudio longitudinal,” Revista de orientacion educacional, ISSN-e 0719-5117, ISSN 0716-5714, No. 39, 2007, págs. 47-65, no. 39, pp. 47–65, 2007, Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2347007.

- “63”.

- A. Naralan, “E-DEVLET’E ETKĐ EDEN FAKTÖRLER.

- “65”.

- J. A. G. M. van Dijk, “Digital divide research, achievements and shortcomings,” Poetics, vol. 34, no. 4–5, pp. 221–235, Aug. 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.poetic.2006.05.004. [CrossRef]

- X. Cai, “ Jan A. G. M. van Dijk. The Deepening Divide: Inequality in the Information Society . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005, 240 pp., ISBN 141290403X (paperback) ,” Mass Commun Soc, vol. 11, no. 2, pp. 221–224, Apr. 2008, doi: 10.1080/15205430701528655. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Stern, A. E. Adams, and S. Elsasser, “Digital inequality and place: The effects of technological diffusion on internet proficiency and usage across rural, Suburban, and Urban Counties,” Sociol Inq, vol. 79, no. 4, pp. 391–417, Nov. 2009, doi: 10.1111/j.1475-682X.2009.00302.x. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Witte, “The Internet and Social Inequalities.

- J. A. G. M. Van Dijk, “Digital Divide: Impact of Access,” in The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects, Wiley, 2017, pp. 1–11. doi: 10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0043. [CrossRef]

- M. Milakovich and J.-M. Wise, Digital Learning. Edward Elgar Publishing, 2019. doi: 10.4337/9781788979467. [CrossRef]

- G. Watts, “COVID-19 and the digital divide in the UK,” Lancet Digit Health, vol. 2, no. 8, pp. e395–e396, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.1016/s2589-7500(20)30169-2. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Amosun, J. Chu, O. H. Rufai, S. Muhideen, R. Shahani, and M. K. Gonlepa, “Does e-government help shape citizens’ engagement during the COVID-19 crisis? A study of mediational effects of how citizens perceive the government,” Online Information Review, vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 846–866, Aug. 2022, doi: 10.1108/OIR-10-2020-0478. [CrossRef]

- Ali. Balcı, Sosyal bilimlerde araştırma : yöntem, teknik ve ilkeler. Pegem A Yayıncılık, 2001.

- M. Tarafdar, Q. Tu, B. S. Ragu-Nathan, and T. S. Ragu-Nathan, “The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity,” Journal of Management Information Systems, vol. 24, no. 1, pp. 301–328, 2007, doi: 10.2753/MIS0742-1222240109. [CrossRef]

- J. Pablo Hernández-Ramos, ; Fernando Martínez-Abad, F. J. García Peñalvo, ; M Esperanza, H. García, and M. José Rodríguez-Conde, “Teacher Attitude Scale Regarding the Use of ICT. Reliability and Validity Study.” [Online]. Available: http://bit.ly/valoracion_escala.

- D. Abdullah ÇALIŞKAN Toros Üniversitesi, “Türk Sosyal Bilimler Araştırmaları Dergisi /Journal of Turkish Social KRİZ YÖNETİMİ: BİR ÖLÇEK GELİŞTİRME ÇALIŞMASI”.

- R. H. Green, “Sampling design and statistical methods for environmental biologists,” p. 257, 1979, Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com/books/about/Sampling_Design_and_Statistical_Methods.html?hl=tr&id=_psJ7PlyJ_wC.

- E. Deutskens, K. De Ruyter, and M. Wetzels, “An assessment of equivalence between online and mail surveys in service research,” Journal of Service Research, vol. 8, no. 4. pp. 346–355, May 2006. doi: 10.1177/1094670506286323. [CrossRef]

- D. J. Solomon, “Recommended Citation Recommended Citation Solomon,” Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, vol. 7, no. 19, 2000, doi: 10.7275/404h-z428. [CrossRef]

- M. Goodman, “Future Crimes,” 2017. [Online]. Available: http://www.sanantoniobookreviews.com/.

- “Snowball sampling in management research: a review,... - Google Akademik.” Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.gr/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=.+Snowball+sampling+in+management+research%3A+a+review%2C+analysis%2C+and+guidelines+for+future+research.+In%3A+Annual+Meeting+of+the+Southern+Management+Association&btnG=.

- “İstatistik Kurumu > ANASAYFA.” Accessed: May 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://stat.gov.ct.tr/.

- John. Gill and Phil. Johnson, “Research Methods for Managers,” pp. 1–288, 2010.

- L. SÜRÜCÜ and A. MASLAKÇI, “VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY IN QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH,” Business & Management Studies: An International Journal, vol. 8, no. 3, pp. 2694–2726, Sep. 2020, doi: 10.15295/bmij.v8i3.1540. [CrossRef]

- “Regression Analysis and Linear Models: Concepts, Applications, and ... - Richard B. Darlington, Andrew F. Hayes - Google Kitaplar.” Accessed: May 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://books.google.com.cy/books?hl=tr&lr=&id=YDgoDAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=darlington+and+hayes&ots=8iF_wSeDuF&sig=gavsNtCcyBPo6x775OXR4kZ26tE&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q=darlington%20and%20hayes&f=false.

- S. Gürbüz and F. Şahin, Sosyal bilimlerde araştırma yöntemleri : felsefe - yöntem -analiz.

- “darlington and hayes 2017 - Google Akademik.” Accessed: May 06, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://scholar.google.gr/scholar?hl=tr&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=darlington+and+hayes+2017&btnG=.

- A. Pardo and M. Román, “Reflexiones sobre el modelo de mediación estadística de baron y kenny,” Anales de Psicologia, vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 614–623, 2013, doi: 10.6018/analesps.29.2.139241. [CrossRef]

- V. Burksiene, J. Dvorak, and M. Duda, “Upstream social marketing for implementing mobile government,” Societies, vol. 9, no. 3, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.3390/soc9030054. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Choi, C. H. Chiu, and H. K. Chan, “Risk management of logistics systems,” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, vol. 90. Elsevier Ltd., pp. 1–6, Jun. 01, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.tre.2016.03.007. [CrossRef]

- J. Choudrie, E. D. Zamani, E. Umeoji, and A. Emmanuel, “Implementing E-government in Lagos State: Understanding the impact of cultural perceptions and working practices,” Gov Inf Q, vol. 34, no. 4, pp. 646–657, Dec. 2017, doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2017.11.004. [CrossRef]

- B. E. Asogwa, “Electronic government as a paradigm shift for efficient public services: Opportunities and challenges for Nigerian government,” Library Hi Tech, vol. 31, no. 1, pp. 141–159, 2013, doi: 10.1108/07378831311303985. [CrossRef]

- S. Basu, “E-government and developing countries: an overview,” International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 109–132, Mar. 2004, doi: 10.1080/13600860410001674779. [CrossRef]

- U. Myint, “CORRUPTION: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND CURES,” 2000.

- M. C. Lio, M. C. Liu, and Y. P. Ou, “Can the internet reduce corruption? A cross-country study based on dynamic panel data models,” Gov Inf Q, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 47–53, Jan. 2011, doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2010.01.005. [CrossRef]

- R. Kumar Shakya, “PROCUREMENT GOVERNANCE FRAMEWORK: SUCCESS TO E-GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT (E-GP) SYSTEM IMPLEMENTATION.”.

- A. Neupane, J. Soar, K. Vaidya, and J. Yong, “Willingness to adopt e-procurement to reduce corruption Results of the PLS Path modeling”, doi: 10.1108/TG-03-2014-0007. [CrossRef]

- K. J. Bwalya and S. Mutula, “A conceptual framework for e-government development in resource-constrained countries: The case of Zambia,” Information Development, vol. 32, no. 4, pp. 1183–1198, Sep. 2016, doi: 10.1177/0266666915593786. [CrossRef]

- N. Nkwe, “E-Government: Challenges and Opportunities in Botswana,” 2012. [Online]. Available: www.ijhssnet.com.

- M. A. Sarrayrih and B. Sriram, “Major challenges in developing a successful e-government: A review on the Sultanate of Oman,” Journal of King Saud University - Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 230–235, 2015, doi: 10.1016/j.jksuci.2014.04.004. [CrossRef]

- W. Li and L. Xue, “Analyzing the critical factors influencing post-use trust and its impact on Citizens’ continuous-use intention of E-Government: Evidence from Chinese municipalities,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 14, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.3390/su13147698. [CrossRef]

- S. Park, M. Graham, and E. A. Foster, “Improving Local Government Resilience: Highlighting the Role of Internal Resources in Crisis Management,” Sustainability 2022, Vol. 14, Page 3214, vol. 14, no. 6, p. 3214, Mar. 2022, doi: 10.3390/SU14063214. [CrossRef]

- F. Kong and S. Sun, “Better understanding the catastrophe risk in interconnection and comprehensive disaster risk defense capability, with special reference to China,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 1–11, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.3390/su13041793. [CrossRef]

- Saylam and M. Yıldız, “Conceptualizing citizen-to-citizen (C2C) interactions within the E-government domain,” Government Information Quarterly, vol. 39, no. 1. Elsevier Ltd., Jan. 01, 2022. doi: 10.1016/j.giq.2021.101655. [CrossRef]

- M. Molino et al., “Wellbeing costs of technology use during Covid-19 remote working: An investigation using the Italian translation of the technostress creators scale,” Sustainability (Switzerland), vol. 12, no. 15, Aug. 2020, doi: 10.3390/SU12155911. [CrossRef]

- B. Cavusoglu, “Knowledge Economy and North Cyprus,” Procedia Economics and Finance, vol. 39, pp. 720–724, 2016, doi: 10.1016/s2212-5671(16)30285-4. [CrossRef]

- M. Penado Abilleira, M. L. Rodicio-García, M. P. Ríos-de Deus, and M. J. Mosquera-González, “Technostress in Spanish University Teachers During the COVID-19 Pandemic,” Front Psychol, vol. 12, Feb. 2021, doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.617650. [CrossRef]

- J. Wang, W. Bao, L. Sun, X. Zhu, B. Cao, and P. S. Yu, “Private Model Compression via Knowledge Distillation.” [Online]. Available: https://github.com/jwanglearn/Private.

- M. E. Milakovich, “The Internet and Increased Citizen Participation in Government”, [Online]. Available: http://www.jedem.orgCC:CreativeCommonsLicense,2010.

- J. Ignacio Criado, G. Martínez-Fuentes, and A. Silván, “Social Media for Political Campaigning. The Use of Twitter by Spanish Mayors in 2011 Local Elections,” Public Administration and Information Technology, vol. 1, pp. 219–232, 2012, doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-1448-3_14. [CrossRef]

- J. Scott, “Creative cities: Conceptual issues and policy questions,” J Urban Aff, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 1–17, Jan. 2006, doi: 10.1111/j.0735-2166.2006.00256.x. [CrossRef]

- S. Ling, G. Pan, and P. R. Devadoss, “E-Government Capabilities and Crisis Management: Lessons from E-Government Capabilities and Crisis Management: Lessons from Combating SARS in Singapore Combating SARS in Singapore,” 2005. [Online]. Available: www.who.int/csr/sars/en/.

- D. Agostino, M. Arnaboldi, and A. Lampis, “Italian state museums during the COVID-19 crisis: from onsite closure to online openness,” Museum Management and Curatorship, pp. 362–372, 2020, doi: 10.1080/09647775.2020.1790029. [CrossRef]

- L. G. Kun and D. A. Bray, “F ollowing the anthrax events of October-Information Infrastructure Tools for Bioterrorism Preparedness Building Dual-or Multiple-Use Infrastructures Is the Task at Hand for State and Local Health Departments,” 2001.

- “116”.

- C. Pelau, D. C. Dabija, and I. Ene, “What makes an AI device human-like? The role of interaction quality, empathy and perceived psychological anthropomorphic characteristics in the acceptance of artificial intelligence in the service industry,” Comput Human Behav, vol. 122, Sep. 2021, doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2021.106855. [CrossRef]

- F. Bélanger and L. Carter, “The impact of the digital divide on e-government use,” Commun ACM, vol. 52, no. 4, pp. 132–135, Apr. 2009, doi: 10.1145/1498765.1498801. [CrossRef]

| Count (n) | Rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 172 | 42.8 |

| Female | 220 | 54.7 |

| Not-specified | 10 | 2.5 |

| Age Group | ||

| 18-20 | 15 | 3.7 |

| 21-30 | 104 | 25.9 |

| 31-40 | 113 | 28.1 |

| 41-50 | 94 | 23.4 |

| 51-60 | 69 | 17.2 |

| 61 and over | 7 | 1.7 |

| Educational Status | ||

| Primary School Graduate | 18 | 4.5 |

| High School Graduate | 197 | 49.0 |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 164 | 40.8 |

| Postgraduate | 23 | 5.7 |

| Sector Occupied | ||

| Private Sector | 271 | 67.4 |

| Public Sector | 101 | 25.1 |

| Not-specified | 30 | 7.5 |

| Nationality | ||

| NORTHERN CYPRUS | 336 | 83.6 |

| NORTHERN CYPRUS + TR | 2 | 0.5 |

| Other | 64 | 15.9 |

| Total | 402 | 100.00 |

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Average | Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crisis Management | 402 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 3.411 | 0.835 |

| Mobile Government | 402 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.691 | 0.844 |

| Techno-Skepticism | 402 | 1.00 | 5.00 | 2.940 | 0.846 |

| NORTHERN CYPRUS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| 1. Crisis Management | 3.412 | 0.835 | 1 | ||

| 2. Techno-Skepticism | 2.940 | 0.846 | 0.332** | 1 | |

| 3. Mobile Government | 2.691 | 0.844 | 0.495** | 0.522** | 1 |

| Path | Coeff | SE | t | p | LLCI | ULCI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM → MG | 0.3653 | 0.0420 | 8.7059 | 0.000 | 0.2828 | 0. 4478 |

| CM→ TS | 0.3368 | 0.0478 | 7.0509 | 0.000 | 0.2429 | 0. 4308 |

| TS → MG | 0.4008 | 0.0414 | 9.6774 | 0.000 | 0. 3194 | 0. 4822 |

| Mediating Effect (Indirect effect) | ||||||

| Coeff | SE | LLCI | ULCI | |||

| CM →TS →MG | 0.1974 | 0.1974 | 0.1974 | 0.1974 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).