Submitted:

13 May 2024

Posted:

14 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Sampling and Participants

2.3. Inclusion / Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Procedure and Data Collection

2.5. Data Analysis and Thematic Development

3. Results

3.1. Perceptions of the Three Primary Exercises

3.2. Sources of Stress

3.3. Sources of Empowerment and Disempowerment

4. Discussion

Implications for Practice

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kaplan, S. L., Coulter, C., & Sargent, B. (2018). Physical therapy management of congenital muscular torticollis: A 2018 evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the APTA Academy of Pediatric Physical Therapy. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 30(4), 240–290. [CrossRef]

- Stellwagen, L., Hubbard, E., Chambers, C., & Jones, K. L. (2008). Torticollis, facial asymmetry and plagiocephaly in normal newborns. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 93(10), 827–831. Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Book Title, 3rd ed.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2008; pp. 154–196. [CrossRef]

- Bashir, A., Amjad, F., Ahmad, A., Arooj, A., & Gilani, S.A. (2022). Effect of physical therapy treatment in infants treated for congenital muscular torticollis- a narrative review. Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association. [CrossRef]

- Sargent, B., Kaplan, S. L., Coulter, C., & Baker, C. (2019). Congenital muscular torticollis: Bridging the gap between research and clinical practice. Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatrics, 144(2). [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, K. C. R., Jacobson, R. P., & Kaplan, S. L. (2020). Associations between congenital muscular torticollis severity and physical therapy episode. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 32(4), 314. [CrossRef]

- Greve, K. R., Sweeney, J. K., Bailes, A. F., & Van Sant, A. F. (2022). Infants with congenital muscular torticollis: Demographic factors, clinical characteristics, and physical therapy episode of care. Pediatric Physical Therapy, Publish Ahead of Print. [CrossRef]

- Fenton, R., & Gaetani, S. A. (2019). A pediatric epidemic: Deformational plagiocephaly/brachycephaly and congenital muscular torticollis. Contemporary Pediatrics, 36(2), 10–18.

- Schertz, M., Zuk, L., Zin, S., Nadam, L., Schwartz, D., & Bienkowski, R. S. (2008). Motor and cognitive development at one-year follow-up in infants with torticollis. Early Human Development, 84(1), 9–14. [CrossRef]

- Speltz, M. L., Collett, B. R., Stott-Miller, M., Starr, J. R., Heike, C., Wolfram-Aduan, A. M., King, D., & Cunningham, M. L. (2010). Case-control study of neurodevelopment in deformational plagiocephaly. Pediatrics, 125(3), e537–e542. [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, A., Büğüşan Oruç, S., Erdoğan, D., & Mutlu, A. (2022). Analysis of spontaneous movements in infants with torticollis. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 34(1), 17–21. [CrossRef]

- Öhman, A., Nilsson, S., Lagerkvist, A.-L., & Beckung, E. (2009). Are infants with torticollis at risk of a delay in early motor milestones compared with a control group of healthy infants? Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 51(7), 545–550. [CrossRef]

- Collett, B. R., Kartin, D., Wallace, E. R., Cunningham, M. L., & Speltz, M. L. (2020). Motor function in school-aged children with positional plagiocephaly or brachycephaly. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 32(2), 107–112. [CrossRef]

- Schertz, M., Zuk, L., & Green, D. (2013). Long-term neurodevelopmental follow-up of children with congenital muscular torticollis. Journal of Child Neurology, 28(10), 1215–1221. [CrossRef]

- Hattangadi, N., Cost, K. T., Birken, C. S., Borkhoff, C. M., Maguire, J. L., Szatmari, P., & Charach, A. (2020). Parenting stress during infancy is a risk factor for mental health problems in 3-year-old children. BMC Public Health, 20(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Cousino, M. K., & Hazen, R. A. (2013). Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: A systematic review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 38(8), 809–828. [CrossRef]

- Oyetunji, A., & Chandra, P. (2020). Postpartum stress and infant outcome: A review of current literature. Psychiatry Research, 284, 112769. [CrossRef]

- de Cock, E. S. A., Henrichs, J., Klimstra, T. A., Janneke B. M. Maas, A., Vreeswijk, C. M. J. M., Meeus, W. H. J., & van Bakel, H. J. A. (2017). Longitudinal associations between parental bonding, parenting stress, and executive functioning in toddlerhood. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(6), 1723–1733. [CrossRef]

- Khalsa, A. S., Weber, Z. A., Zvara, B. J., Keim, S. A., Andridge, R., & Anderson, S. E. (2022). Factors associated with parenting stress in parents of 18-month-old children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48, 521-530. [CrossRef]

- Sun, X., Seeley, J. R., & Allen, N. B. (2020). Parental internalizing disorder and the developmental trajectory of infant self-regulation: The moderating role of positive parental behaviors. Development and Psychopathology, 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Oledzka, M. M., Sweeney, J. K., Evans-Rogers, D. L., Coulter, C., & Kaplan, S. L. (2020). Experiences of parents of infants diagnosed with mild or severe grades of congenital muscular torticollis. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 32(4), 322–329. [CrossRef]

- Genna, C. W. (2015). Breastfeeding infants with congenital torticollis. Journal of Human Lactation, 31(2), 216–220. [CrossRef]

- Rabino, S. R., Peretz, S. R., Kastel-Deutch, T., & Tirosh, E. (2013). Factors affecting parental adherence to an intervention program for congenital torticollis. Pediatric Physical Therapy, 25(3), 298–303. [CrossRef]

- Bassi, G., Mancinelli, E., Di Riso, D., & Salcuni, S. (2021). Parental stress, anxiety and depression symptoms associated with self-efficacy in paediatric type 1 diabetes: A literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), Article 1. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, M. L., Duncan, C. L., Stokes, Jocelyn O., & Pereira, D. (2014). Association of caregiver health beliefs and parenting stress with medication adherence in preschoolers with asthma. Journal of Asthma, 51(4), 366–372. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H., Sefcik, J. S., & Bradway, C. (2017). Characteristics of qualitative descriptive studies: A systematic review. Research in Nursing & Health, 40(1), 23–42. [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J., & Poth, C. (2018). Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among the Five Approaches (6th ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Amaral, D. M., Cadilha, R. P. B. S., Rocha, J. A. G. M., Silva, A. I. G., & Parada, F. (2019). Congenital muscular torticollis: Where are we today? A retrospective analysis at a tertiary hospital. Porto Biomedical Journal, 4(3), e36. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, C. F., Rindler, D., & Leverone, B. (2019). Moving into tummy time, together: Touch and transitions aid parent confidence and infant development. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40, 277–278. [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, L., Kerr, Stanley, & Okely. (2020). Tummy time and infant health outcomes: A systematic review. Pediatrics, American Academy of Pediatrics, 145(6). e20192168. [CrossRef]

| Parent Characteristics | |||||||||

| Participant | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 |

| Single or couple interview | Single * |

Single | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single | Single |

| 1st child? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Comment on Labor & Delivery | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| Concern for reflux | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Infant Characteristics | |||||||||

| Participant | P1 | P2 | P3 | P4 | P5 | P6 | P7 | P8 | P9 |

| Gender | Male | Male | Female | Male | Female | Female | Female | Male | Male |

| Age at Diagnosis in weeks | 4 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 11 | 12 | 16 |

| Age at 1st PT session (weeks) |

7 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 11 | 12 | 21 |

| Severity Classification | Mild | Mild | Mild | Mod. | Mild | Mod. | Mod. | Mild | Mod. |

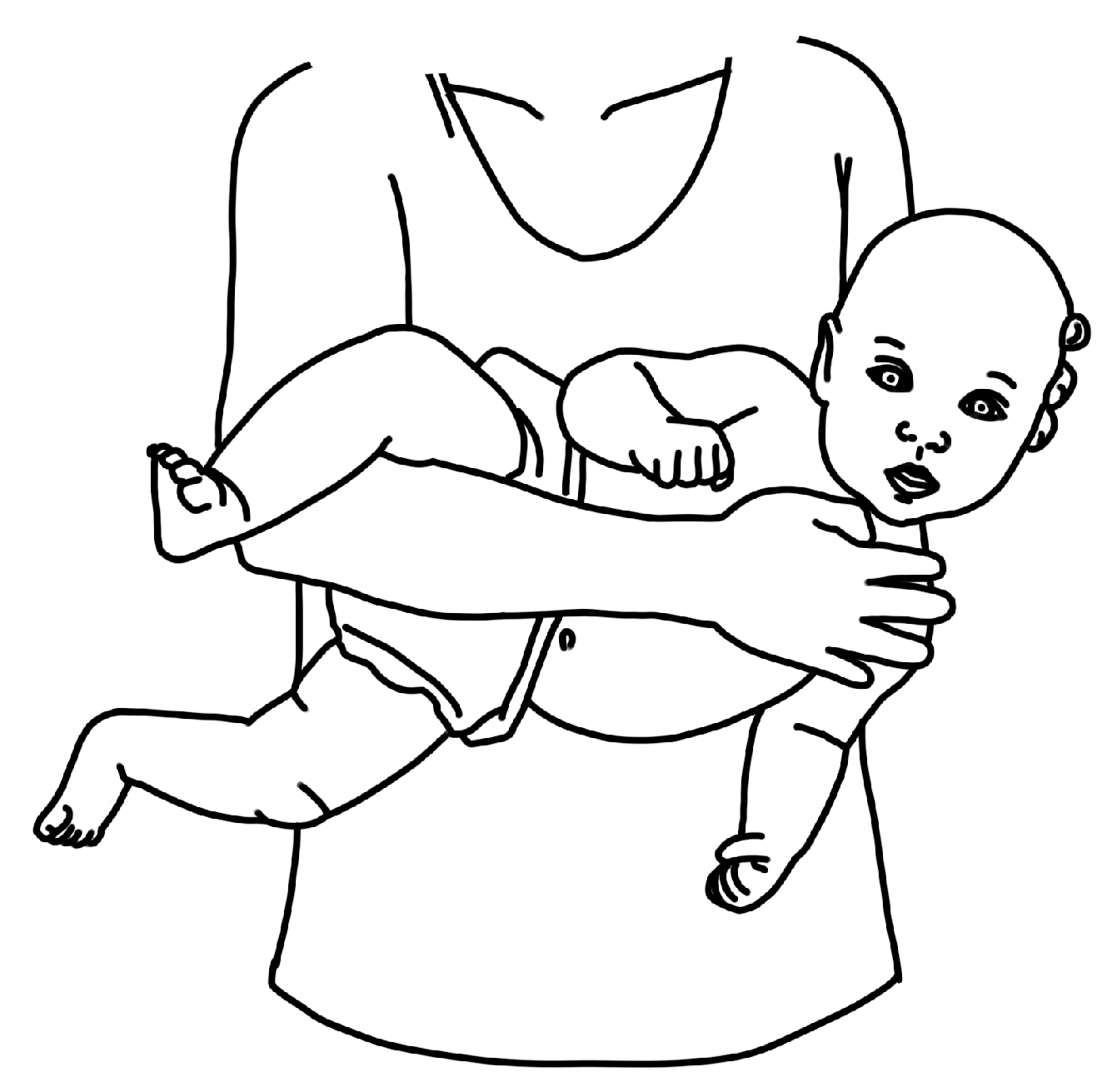

| Theme 1: Tummy time: The fast favorite | ||

| Exemplar data support: I feel like tummy time has become … we’re just playing with her as a baby. I think the other two stretches really feel… different than play time. (P1) | ||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes |

| T1 | Tummy time wasn’t very happy time initially … but overtime she has become stronger. (P6) | Familiar activity Better over time |

| T2 | Tummy time is going significantly better since we started the PT. In the beginning he literally hated it, and now I have so many pictures of him on his belly. (P8) | Intuitive Success with tummy time gives hope |

| T3 | When we play, we do tummy time. (P1) | Play time Natural |

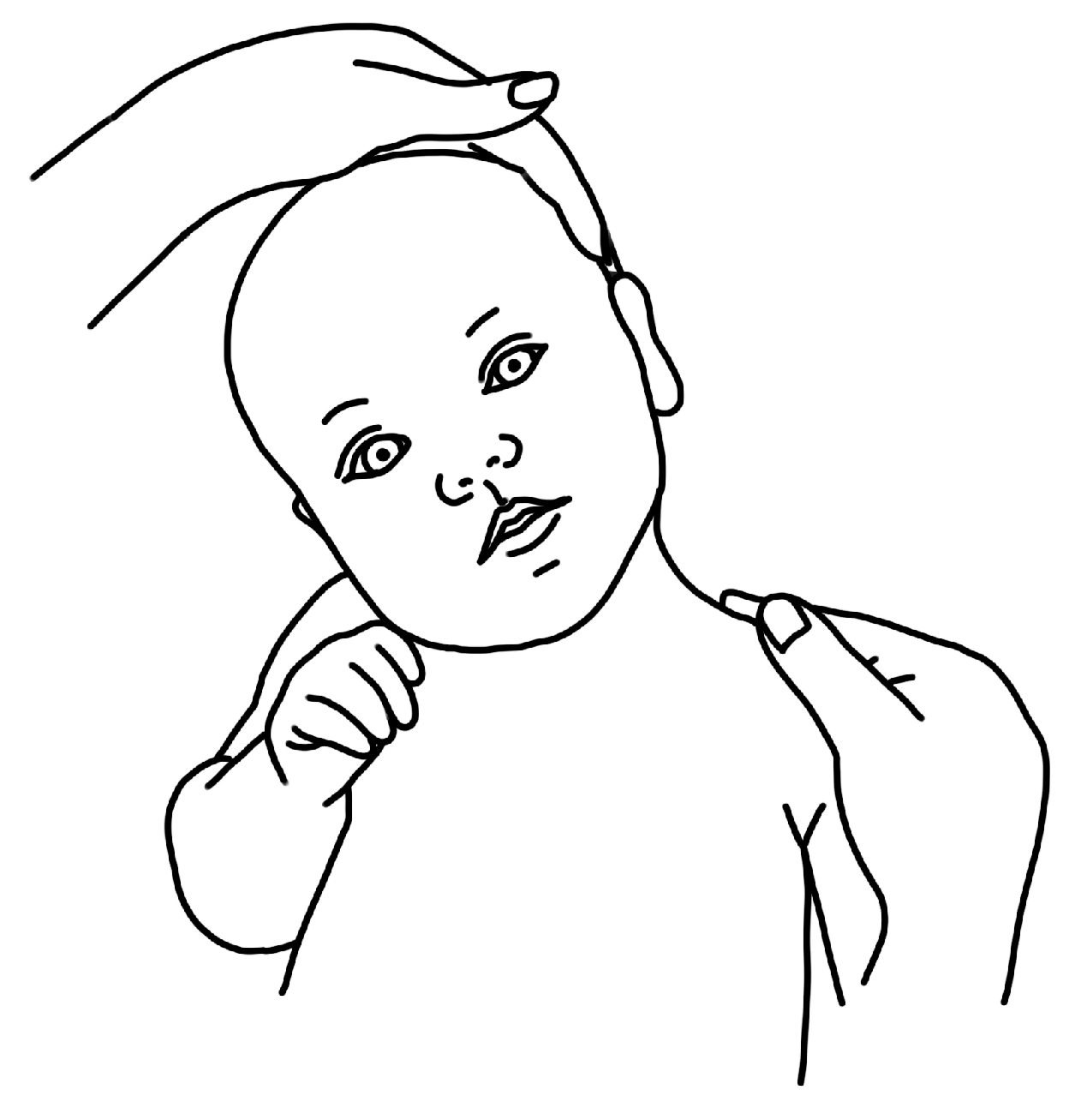

| Theme 2: Ipsilateral Cervical Rotation: More stress than play | ||

| Exemplar data support: It’s easier to get her to do it in different ways; you don’t have to just hold her head. She could follow a toy or follow my face, so you can do it while playing versus having to make her do it (P3) | ||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes |

| T1 | Well, my baby gets really angry when I turn her head…she doesn’t care for stretching, she just gets annoyed. (P5) | Stressful Baby hates it Possible to incorporate into play |

| T2 | It definitely feels less forceful and more motivating. I think being able to make eye contact or use the toy feels like a big difference. With a three-week old you can’t encourage them, it’s only your hand. (P4) | Still forced Using strategies (ie. toys) to accomplish motion |

| T3 | I’d rather do the stretching her arms overhead, those feel a little more functional, a little more movement going on. (P1) | Low priority Progress with head turns = less urgency to do exercise |

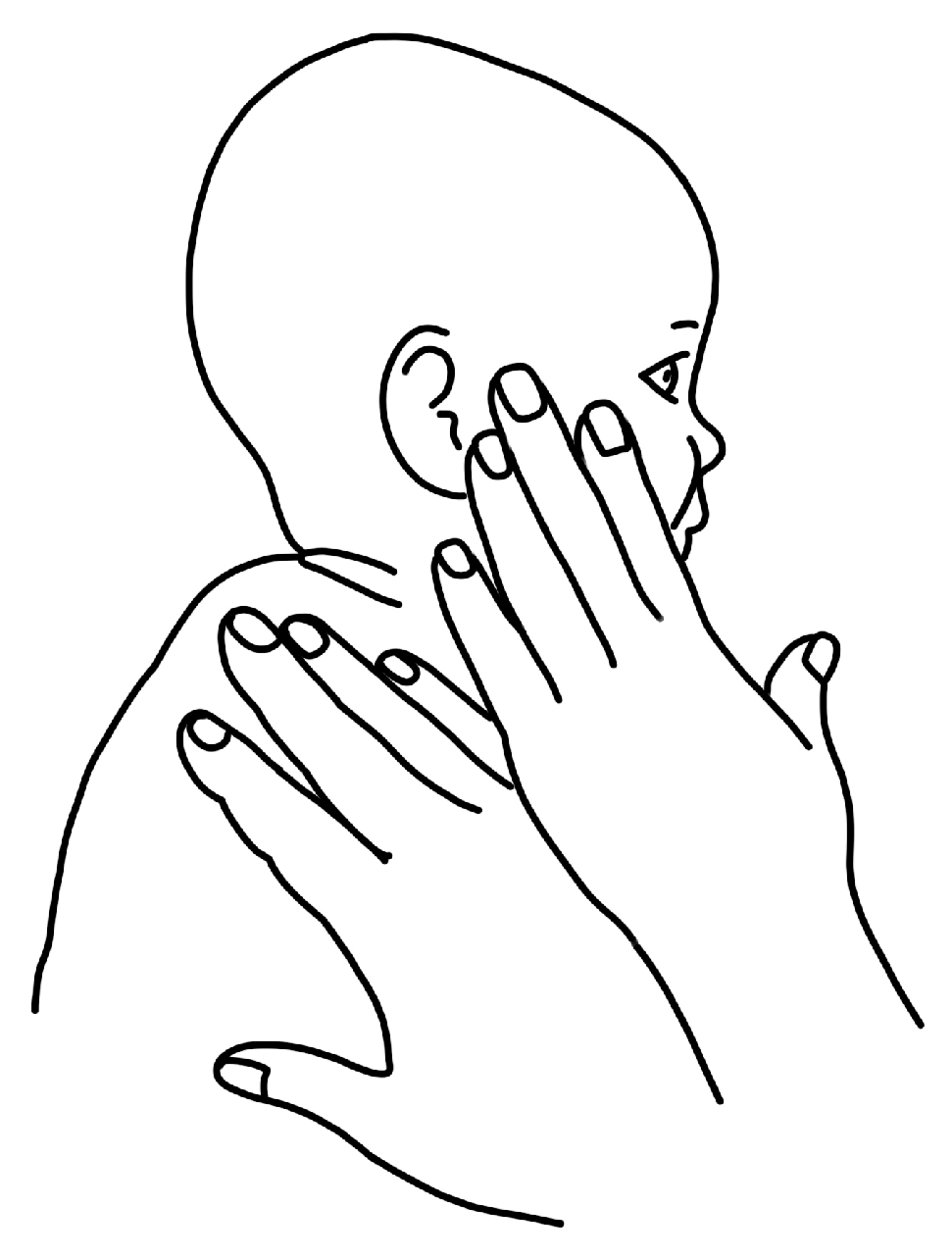

| Theme 3: Contralateral Cervical Lateral Flexion: Deliberate and Uncomfortable | ||

| Exemplar data support: …it’s the only exercise that feels like “PT” …I guess it’s not always the one we rushed to do. (P1) | ||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes |

| T1 | Ear to shoulder is definitely more awkward to do because you have to do it holding her up. It’s more intentional… I mean you can get her to turn her head with a toy, but you can’t get her to put her ear to her shoulder with a toy. (P3) | Awkward Intentional |

| T2 | It’s not my favorite, and she doesn’t like it, so that doesn’t make it any better. (P5) | Not becoming play Not natural |

| T3 | Ear to shoulder is just not a natural movement like when she’s playing. (P3) | Not performed |

| Theme 1: Guilt and uncertainty as internal sources of stress | ||

| Exemplar data support: I think just the overall stressor is that we feel like we just want to enjoy him being a baby, and we’re constantly like, ‘oh, he’s lying on his back, we should pick him up or we should do the exercise.’ If we have any down time, I know we both feel like we can’t just play with him because we’re constantly thinking about, ‘well what should he be doing?’ (P2) | ||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes |

| T1 | …birth is something that my body is supposed to know how to do, but I wasn’t able to do, and in not being able to ‘do,’ I hurt my baby. (P8) So we went home and tried to do it a few times after that appointment, and she wasn’t as upset or anything so we thought we weren’t doing it right and we were worried… are we hurting her by not making her cry? (P1) |

Guilt Blame Uncertainty |

| T2 | He loves to lay on his back and kick around. He loves it so much, but every time he’s doing it, I’m like, ‘I need to pick him up and re-position to be on his back’ or ‘he’s looking the wrong way.’ (P2) I don’t do it as… regularly as I should… I know it’s only hurting [baby], and I feel terrible about that. But I’m also like ‘I can only do what I can do.’ (P9) |

Guilt for not doing enough Diagnosis anxiety |

| T3 | Like ‘oh am I doing this right? Is this the way it’s supposed to go?’ (P5) Sometimes we’re scared to advocate for ourselves, but I cannot be scared to advocate for him. (P8) |

Uncertainty Advocacy for baby Recognition of need for early mitigation of guilt |

| Theme 2: Work, family, and Google as external sources of stress | ||

| Exemplar data support: … we’re flying by the seat of our pants trying to figure out what will work best. (P5) | ||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes |

| T1 | “We Googled it—big mistake … the images on Google are really scary. No, Googling didn’t make me feel better. Googling freaked me out.” (P2) | Overwhelmed |

| T2 | Between trying to introduce solids and the bedtime routine I’m just like, “oh we have to do these stretches,” and I try to squeeze them in and they’re just a little bit more of an afterthought. (P9) My [partner] actually lost a family member to SIDS [sudden infant death syndrome]… So going into anything about repositioning and flipping and turning and pillows and anything felt very scary (P8) |

Overwhelming Fear of past trauma/SIDS Time commitment Return to work |

| T3 | … when we were both sleep deprived, I think that was probably the toughest part, but now that we’re getting a little more sleep, it’s starting to get a little easier. (P7) But the past two weeks especially I’ve just been like ‘there’s not enough time, we gotta do this bedtime routine, and we got to get you to sleep’ (P9) |

Work as a barrier Lack of sleep Need for flexibility |

| Theme 1: Sources of Parental Empowerment | |||

| Category 1: PT = Relief | |||

| Exemplar data support: “I think it was a big leap after PT because we had a plan, and we got the proper care for her… So I think that the PT visit was definitely a big ‘OK, we can do this.’ (P1) | |||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes | |

| T1 | …you watch and if it doesn’t feel right this way, you can do it that way to modify… all sorts of information that we never got with the pediatrician. With the PT we don’t feel any unease about how this works. (P5) …for me at least, having those [instructions] “these are the three to five things that you can do for this amount of time this many times a day,” having that concrete instruction alleviates some of the stress for me. (P9) |

PT education PT plan = reassurance Positive therapeutic alliance |

|

| T2 | … and he has loosened up so much it really has helped even in the two weeks that we’ve been in PT it’s just been helpful to identify something that we can do that feels like it’s actually helping and being able to see immediate improvement. (P8) It’s kind of nice to have someone who knows some of the things that you don’t, and not to be paranoia-ing-ly Googling things all the time…which is just a bad idea…it’s nice to have a resource. (P3) |

Belief in PT PT as an information filter |

|

| T3 | I knew what to expect in PT sessions which was so nicely consistent and then as we watched [baby] master certain things we moved on to ‘oh this week you’re going to work on this,’ so I knew we were getting better. (P5) | Being listened to Consistent information Matter-of-fact guidance Confidence to scale back from PT |

|

| Category 2: Seeing the bigger picture | |||

| Exemplar data support: Seeing her rolling really shows you how important it is for her to be able to look in both directions. So that was like “oh I’m not just doing this to stretch your neck out.” (P3) | |||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes | |

| T1 | …And flat spots … I hate to say it but there’s a cosmetic aspect that motivates me. … the other thing that is highly motivating is that [the PT] mentioned that sometimes these children can fall back developmentally so I became really committed to the PT regimen. (P5) | Seeing a difference Increasing confidence |

|

| T2 | In dealing with this, we know that she will recover, and she will be OK. (P7) | Advantageous for general development Normalizing CMT difficulties with parent support groups |

|

| T3 | Well, she started to be able to sit…And when she mastered that, I felt really good about it but perhaps most importantly, when she started to reach for toys at her midline I thought, ‘OK we’re good.’ (P5) | “It’s curable” Hitting milestones Baby = strong |

|

| Theme 2: Sources of Parental Disempowerment | |||

| Category 1: Medical Community chaos | |||

|

Exemplar data support: Before I met with the PT and really understood how to do the exercises – what I should be doing, how I should be doing them, and for how long and how often – I just was like OK we’re supposed to be doing these stretches, but I didn’t really know what that meant … so that lack of understanding made it harder for me to remember to actually do it. (P9) | |||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes | |

| T1 | [the pediatrician] was showing the exercise …. It was very stressful. She was very … heavy-handed, I mean, I know that babies aren’t fragile, they are getting poked and prodded and everything, but it’s her neck. So, we felt kind of unsettled, and she started to cry and turn bright red and I wanted to know: if you want her neck to be strengthened, we have to do this? (P1) For us, I feel like the physician said one thing about how long it should take, and the PT said another, and the [other provider] said something else. (P4) [From the pediatrician], we didn’t get a lot of instruction of how to do the exercises. At the time I thought I knew what I was doing and then when I went to the PT visit and worked through the exercises and the stretches with [the PT], I definitely was like “Oh, I was not doing this effectively.” (P9) |

Delayed referral Physician prescribed exercise Not feeling heard Conflicting or ambiguous information (from providers, internet, and family) |

|

| T2 | Having the appointment felt stressful because we weren’t sure what was going to happen, and finding providers… Do you go to PT… the chiropractor … myofascial? And you’ve been given so many suggestions, so sorting through all of that while trying to adjust to everything else is really stressful. (P4) They [PT and another provider] both said they were trying to reach the same goal, but one was a stretch with the muscle and the other was a stretch against… so we were like it doesn’t make sense to do both because how will we ever know if we are keeping it from progressing by doing both…. (P4) |

Lack of shared decision making Non-EBP practices Negativity from other providers |

|

| T3 | We just weren’t meshing well … I feel like she [healthcare provider] was using scare-tactics. I was feeling very overwhelmed every time we left because it was like there were a million things wrong with my baby. (P2) | Lack of alliance with healthcare provider (non-PT) | |

| Category 2: Feeling overwhelmed | |||

| Exemplar data support: “when the PT gave us handouts of the exercises, it was showing a lot of different ways to do it, but I did get overwhelmed looking at all the images, like I would have just rather seen three different things to do without all the options. (P2) | |||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes | |

| T1 | Without PT we would not have been able to learn about his specific type of flat head, and so we would have been overwhelmed and internalizing a lot of guilt…. (P8) So then trying to think about an additional appointment to another provider, and then sift through that information felt overwhelming. It was like, do we have to do this? Should we do it now? You know, when your baby is like 2 and ½ weeks old. No one could tell us for sure. (P4) |

Overwhelmed Frequency & variations of exercises Finding pertinent information about diagnoses: CMT/PP |

|

| T2 | I think my stress is not so much about not knowing what’s going on with her now, but more making sure I’m doing enough with her all day. When you do PT I think it makes you a little more aware of ‘OK am I putting her down too much? Is she in this chair too long? … So I’m just stressed about what to do all day every day. (P2) But the flatness of the head and knowing that there is the potential for cognitive issues was really stressing me out because … I don’t know what I can do about this other than just get him the helmet…. (P9) |

Am I doing enough Resignation to do uncomfortable exercise Increased number of exercises Concern for cranial molding peaking |

|

| T3 | … he also had brachycephaly, which was a direct result of his positioning in my womb. So, we have been working on the back of his head but also the side of his head, which is overwhelming, …but being able to talk through the trauma of my birth with the PT and him being stuck really helped…. (P8) | Work schedule v child’s schedule | |

| Category 3: Challenges of time management | |||

| Exemplar data support: … so early detection is useful. Even if we figured this out at, let’s say, six months age, by that time both of us would be working again full-time…so if you can catch something early on that is probably better. (P6) | |||

| Timepoint | Additional participant quotes | Codes | |

| T1 | When I am at home we generally split up … I basically give a few hours in the morning, some hours in the evening. … if I’m going to the office then [spouse] plays with her and she does activities with her at home. (P6) … between all the things in our life, all the different stuff, it’s been harder to find the right time to do it. (P4) |

Division of labor (parent dyad) Managing new life routine |

|

| T2 | Especially since the first month, when we only had 3 exercises to do and now we have a lot more. It’s a full-time job. The time commitment is incredible, and then there’s more stress because of the added things to do. (P2) | Sleep routine Return to work Juggling act |

|

| T3 | I don’t feel like the PT part was stressful. It’s more time management and figuring out schedules and getting sleep. (P7) I’m sure if I was working, or if my partner - he’s very busy at work - I imagine if he had to be trying to do what I’m doing for this part of it then it would feel overwhelming, so we divide and conquer. (P4) |

Work schedule = less focused attention on exercises Daycare |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).