1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic prompted a rapid shift from in-person to virtual learning in dental education. While virtual education has been considered a reasonable alternative to traditional in-person learning, the post-pandemic era has witnessed a temporary transition to what was initially referred to as “Emergency Remote Learning” [

1]. As we reflect on the post-pandemic utilization and the lasting impact of this forced transition, a need is to reimagine the effectiveness of this current makeshift learning platform.

Some healthcare institutions continue to adopt virtual clinical teaching and identify effective ways to improve student engagement and interactivity [

2]. For example, a qualitative study of virtual learning among 45 medical trainees from Harvard Medical School, revealed high satisfaction with virtual learning during the pandemic [

3]. Specifically, the majority of respondents were satisfied with virtual read-outs/virtual interdisciplinary rounds and expressed a desire to maintain key elements of virtual education in the post-pandemic period [

3]. A survey among 2,721 UK medical students across 39 institutions investigated the influence of online delivery modalities on facilitating medical education [

4]. Survey results showed a significant increase in study time, with flexibility and interactivity being the top benefits and distractions (poor internet connection, family distractions and the timing of the tutorials) as the main challenges [

4]. Similarly, results from a global survey assessing participant preferences for virtual online orthodontic learning sessions concluded that accessibility of post videos was instrumental in optimizing learning by improving memory retention [

5]. However, engaging learners’ interests was mainly associated with the acquisition of new learning styles, knowledge, and social networking [

5].

First introduced by Higgins, et al. in 1997, Regulatory Focus Theory (RFT) explained how people’s motivation towards positive outcomes (promotion focus) or away from negative outcomes (prevention focus) affects human behavior and goal achievement [

6]. Participants’ responses to RFT questionnaires were used to compute scores to predict their self-regulatory orientations [

7]. Li’s study on Chinese adolescents explored the relationship between regulatory focus and learner engagement and concluded that promotion focus orientation was more predictive of learner engagement when compared with preventive focus [

8]. Subjects with a high promotion focus and low preventive focus exhibited higher academic self-efficacy, lower depression, greater learner engagement, and more positive adolescent development [

8]. These studies suggested that RFT can offer useful insights and predictions to enhance our understanding of how students perceive motivation in dental education, however, currently, no studies have employed RFT to assess the engagement of trainees in dental education, regardless of in-person or virtual modalities.

Furthermore, healthcare professionals have a higher rate of burnout than the general population [

9]. During the residency period, particularly, the stress level is elevated in terms of training duration and intensity, and insufficient time to adjust, leading to burnout or psychobiological exhaustion [

10]. In worst cases, burnout affects healthcare providers’ clinical judgments, the ability to communicate, and the quality of care delivery [

11,

12]. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, insomnia, and burnout syndrome among healthcare providers raised a heated discussion in the healthcare studies [

13,

14,

15,

16].

Since limited research has been conducted to assess the perception of virtual learning among dental residents and faculty during COVID-19, and the burnout of the residents, this study was designed to a) assess the perceptions and effectiveness of virtual learning among dental residents and faculty in Upstate New York and b) employ RFT to understand the impact of motivational orientations on virtual learning outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

From June to August 2021, 46 dental residents and 10 faculty members from an Upstate New York institute participated in a study. These participants, involved in the Advanced Education in General Dentistry (AEGD) program and the Department of General Dentistry, experienced both virtual and in-person classes. The AEGD program included five learning modalities: didactic lectures, research presentations, case presentations, literature reviews, and faculty-resident meetings. The study was approved by the University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board #STUDY00007023.

2.2. Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire comprised four sections: demographics, preferred online learning devices and perceptions of virtual education in Section A; regulatory focus types in Section B; and burnout levels in Section C. Section A included five questions on virtual learning experiences, 1) overall feeling about virtual learning modalities; 2) effectiveness of residents’ virtual learning experience; 3) engagement of residents during virtual learning; 4) interactions between residents and instructors in virtual learning; 5) future preference format. In Questions 1-4, each is rated on a 1-5 scale, with higher scores indicating a more favorable view of virtual learning. Question 5 asked participants to choose their preferred future learning format: in-person, virtual, or hybrid.

Section B utilized a Likert scale ranging from “definitely untrue” to “definitely true” to assess regulatory focus types with Fellner et al.’s validated 10-item Regulatory Focus Scale (RFS) questionnaire [

17]. RFS is composed of two sub-scales with five questions measuring promotion focus (e.g., “I prefer to work without instructions from others”) and five questions measuring prevention focus (e.g., “Rules and regulations are helpful and necessary for me”) [

18]. Scores for each scale ranged from 5 to 35 with higher scores indicating a stronger focus for the respective scale. A prevention or promotion score (continuous) was generated for each participant.

In the Section C, participants were asked evaluate their level of burnout, with options ranging from ‘having no symptoms and enjoying work’, to ‘feeling completely burned out’. Higher scores indicated a higher level of burnout.

2.3. Data Analysis

A descriptive analysis was first employed to understand the perceptions of virtual learning among dental residents and faculty members. The findings were presented through a data summary, utilizing percentages and mean ± standard deviation (SD) for a comprehensive overview. Study participants’ self-reported burnout levels were categorized into three groups based on the severity. To explore factors (demographics, where they obtained dental degree, years of practice, age groups, type of program enrollment) associated with the perceptions of virtual learning, a Pearson chi-square or Fischer’s exact test was used for categorical data, and a Kruskal-Wallis test was conducted for numerical data without normal distribution.

The primary outcomes were perception of virtual learning, including overall attitude, effectiveness, engagement, interaction, and future preference. We employed a multiple logistic regression analysis to examine factors associated with these five outcomes. For these outcomes, we first combined the residents’ responses into two levels. For the overall attitude outcome, the first level was defined “Above average” which included responses of ‘excellent’ and ‘good’. The second level was defined as “Below average & average” which included responses of ‘average’, ‘below average’ and ‘poor’. For effectiveness, the five levels scale was also combined to two categories: “Not effective to effective” and “More effective”. For interaction, the five levels scale was merged into two categories: “Not interactive to interactive” and “More interactive”. Similarly, for engagement and interaction, the five-level scales were integrated into two categories each: “Not engaged to engaged” and “More engaged” for engagement, and “Not interactive to interactive” and “More interactive” for interaction, respectively.

For the regression models of engagement and interaction, we included the following independent covariates: RFT scores (numerical) as independent variables and other factors including gender (female vs male), location of DDS received (outside of the US/Canada vs US/Canada), years of practice, and the participants’ age (20-30yrs, 31-40yrs, and 41-50yrs). For the regression models of overall attitude, effectiveness and preference of future learning modalities, we included the variables mentioned above but excluded the regulatory focus score.

In addition, we used multiple logistic regression model to assess factors related to Burnout. The covariates included were: gender (female vs male), location of DDS received (outside of the US/Canada vs US/Canada), years of practice, and the participants’ age (20-30yrs, 31-40yrs, and 41-50yrs). The statistical significance level was set at 5% for all analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

A total of 46 AEGD dental residents and 10 faculty members participated in the study. In summary, the demographics of study subjects include age group, gender, type of dental school attended, years of practice, enrolled residency programs, year of graduation, and preferred devices (

Table 1). Among the residents, 41.4% were female, primarily in the 31-40 year age group (43.5%), followed by the 41-50 year age group (34.8%). In contrast, 30% of the faculty were female, with half over 60 years old and 40% of them between 41-50 years old. Most residents (82.6%) attended dental schools outside the US/Canada, while 40% of faculty attended schools in the US/Canada. Residents were mainly enrolled in 2-year or 3-year AEGD + MS programs. The majority of residents graduated in 2021, with the fewest (6.5%) set to graduate in 2024. For virtual learning, 97.8% of residents used desktop computers, whereas 60% of faculty preferred laptops.

3.2. Perceptions of Virtual Learning

3.2.1. Residents’ Overall Feeling about Virtual Learning Modalities

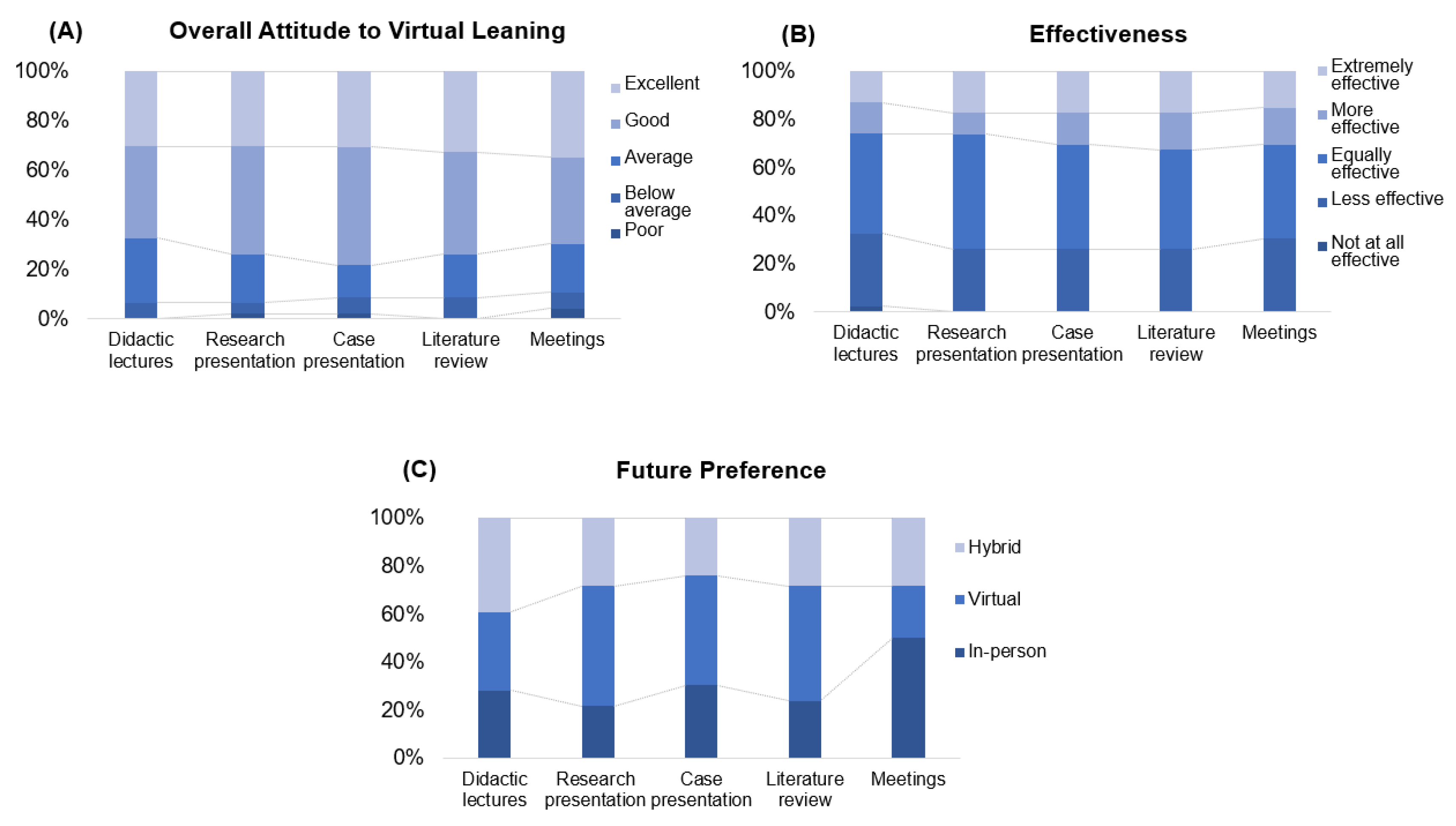

Overall, over 70% of participants were satisfied with virtual learning, rating their experience as above average across all five modalities (

Figure 1A). Case presentations were most favored, with 78.2% receiving “Good” and “Excellent” ratings. Research presentations and literature reviews each had 73.9% above average ratings, while didactic lectures had a balance of “Good” and “Excellent” ratings and few lower ratings. Only 4.4% rated virtual meetings as “Poor”.

Statistical analysis revealed that residents with more years of practice were less likely to favor virtual case presentations and literature reviews (

Table 2). Specifically, more experienced dental practitioners showed less enthusiasm for these modalities, with odds ratios indicating decreasing preference with increasing years of practice (OR 0.80 for case presentations and OR 0.85 for literature reviews, with respective

p-values of 0.027 and 0.047).

3.2.2. Effectiveness of Residents’ Virtual Learning Experience in Comparison to the In-Person Learning Experience

According to the survey, 86.5% of the participating residents indicated a positive perception of virtual learning’s effectiveness across five virtual educational modalities, with preferences varying by where they obtained the dental degree, age, and years of practice (

Figure 1B). More than 73% of participants viewed research presentations, case presentations and literature review sessions are “More effective” and “Extremely effective”. Meetings were also viewed favorably, with no participants considering them “Not at all effective”. Didactic lectures have the highest percentage of “Less effective” and “Not at all effective” ratings, indicating a relative weakness compared to other virtual learning components.

A significant difference was observed between the virtual method of didactic lectures and those dental residents who received their dental degree outside of the U.S. or Canada (

Table 2). Residents with degrees from outside the U.S./Canada found virtual didactic lectures notably less effective [OR 0.07 (0.007, 0.65),

p=0.02], with a strong inclination towards in-person formats. Those aged 31-40 viewed virtual sessions as less effective [ORs 0.08 and 0.14 for case presentations and literature reviews, respectively, p<0.05]. In contrast, among residents aged 20 to 30, 50% of them preferred virtual case presentations over in-person ones. This highlights how age can impact preferences in learning modalities. Lastly, years of experience also affect attitudes toward virtual learning. Residents with more years of experience favored in-person learning over a virtual format for both case presentations (

p<0.05) and literature review sessions (

p<0.05).

3.2.3. Engagement of Residents during Virtual Learning in Comparison to In-Person Learning

Residents reported that their learning through five virtual learning modalities were as engaged as when courses were delivered via in-person modalities.

3.2.4. Interactions between Residents and Instructors in Virtual Learning in Comparison to In-Person Learning

Residents reported no difference in their interactions with instructors across five virtual learning modalities compared to in-person settings.

3.2.5. Preferred Learning Format of the Residents for the Upcoming Years

Approximately 69% of residents clearly prefer incorporating virtual or hybrid elements into most learning modalities as their future learning format (

Figure 1C). Among the five modalities, virtual research presentations and virtual literature review sessions are the most preferred learning methods. Notably, 50% of participants preferred in-person meetings, underscoring the importance of direct interaction in these types of meetings and classes.

A significant difference exists between the virtual method of literature review and where they received their dental degrees. The results indicated a strong preference for literature review among the participating residents [OR (95% CI) 12.04 (1.04, 139.5),

p=0.047] (

Table 2). Even though the results did not reveal a significant difference in any of the other learning modalities, an interesting consistency emerged within foreign-trained residents. All foreign-trained participants expressed a preference for hybrid research presentations, case presentations, and literature review sessions.

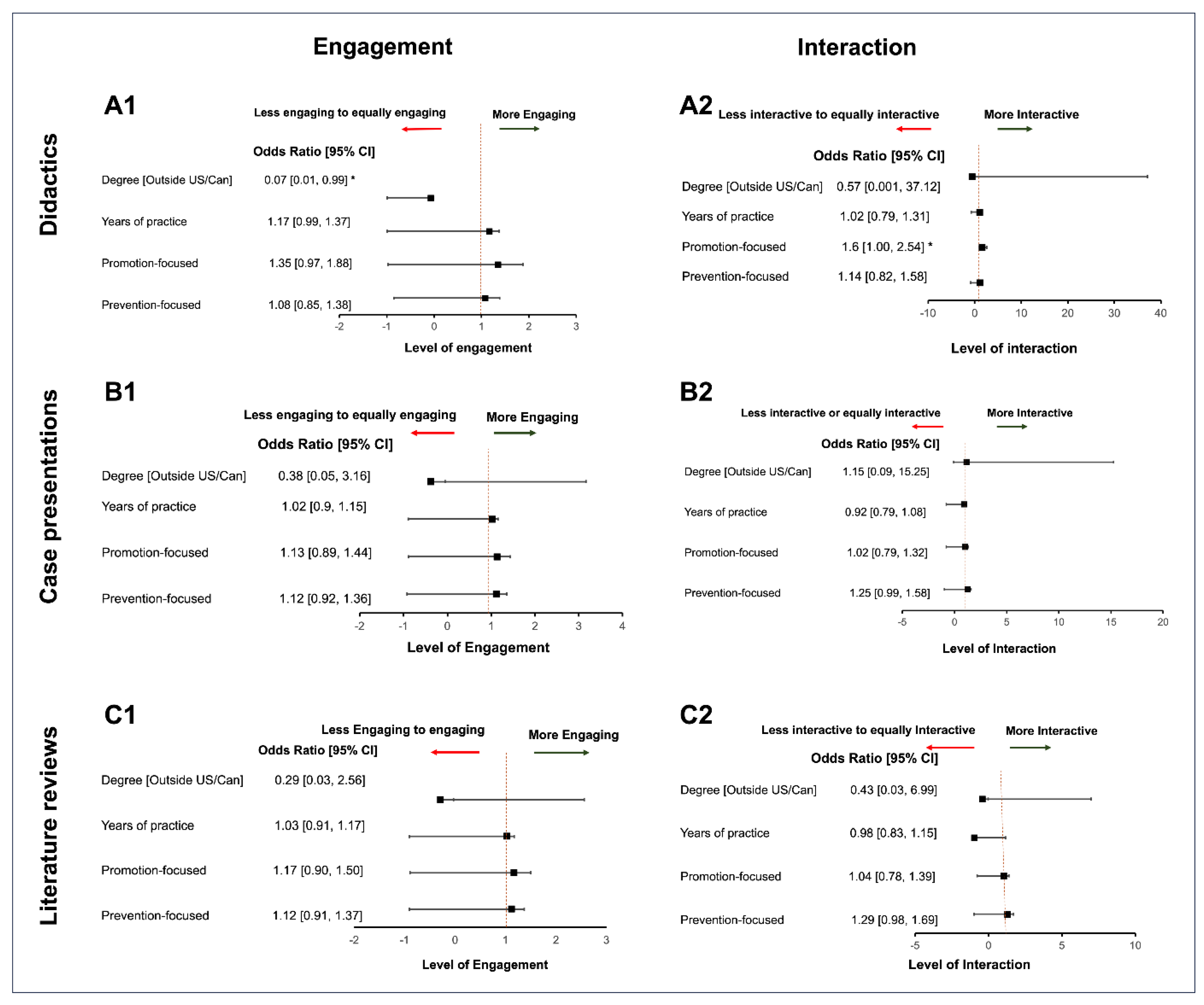

Figure 3 depicts a forest plot examining factors and significant differences were mainly observed in how respondents interpreted effectiveness and interactions with online didactic dental courses. Dental residents with dental degrees from outside the US/Canada have a significantly lower likelihood of engaging virtual didactic lectures compared to their counterparts with US/Canadian dental degrees. [OR (95%CI) 0.07 (0.01, 0.09,

p<0.05)] (

Figure 3A1).

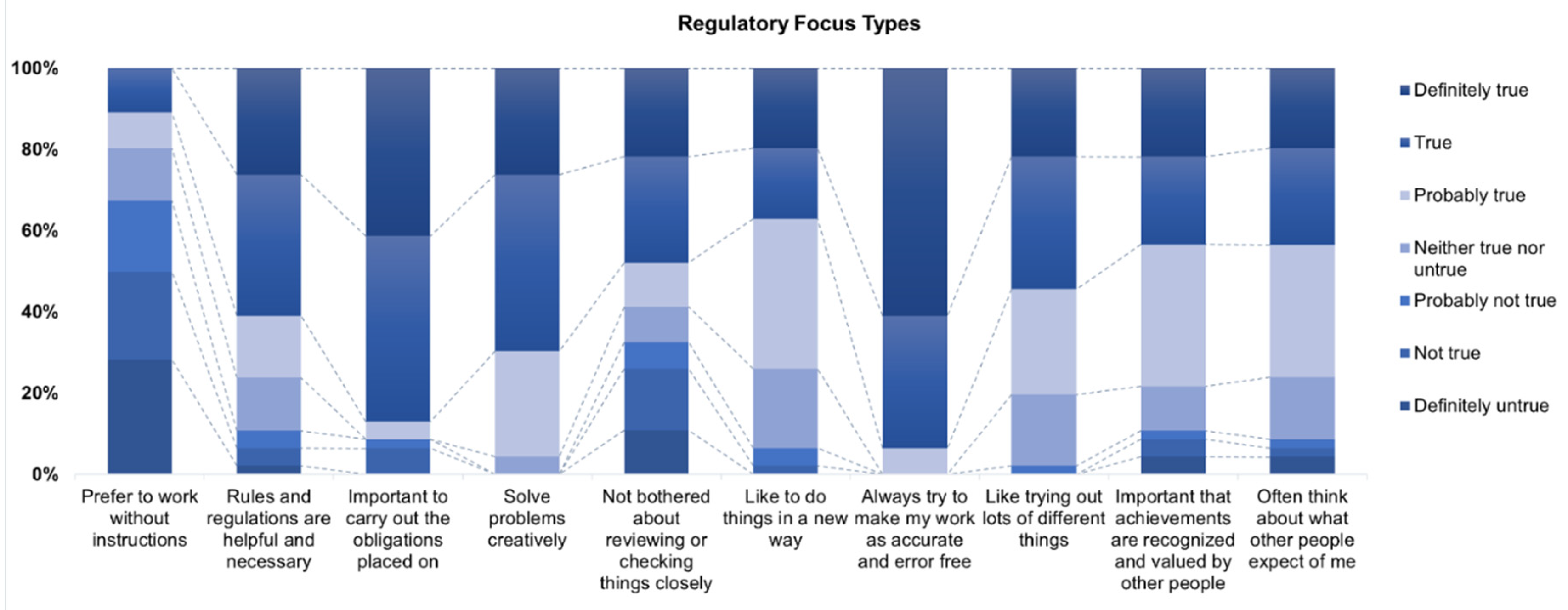

3.3. Regulatory Focus Theory

Each participant had a score for both prevention and promotion focus (continuous). The promotion scores ranged from a low of 15 to a high of 32, and prevention scores ranged from 19 to 35. The survey results present a view of respondents’ preferences for 10 statements in the RFS questionnaire.

A significant portion of respondents (67.4%) did not prefer to work without instructions, while only a small percentage (10.8%) agreed rules and regulations are helpful and necessary (

Figure 2). 59% of them did not like being reviewed and checked their work closely by others. More than 90% of respondents valued creativity in problem-solving, and many participants are open to innovation. All of the respondents agreed that they always try to make work accurate and error-free. The majority of participants thought social recognition and expectations from others were important to them (78.20% and 76.10%, respectively).

Figure 3A2 showed that residents with higher score of promotion RFT considered virtual didactic courses were more interactive than in-person learning during COVID-19 [OR (95%CI) 1.6 (1.00, 2.54,

p<0.05)]. However, for other learning modalities such as research presentations, case presentations, literature review sessions, and faculty-resident meetings, RFT scores in either promotion-focus or prevention-focus were not found to be significantly associated with the residents’ perceptions of virtual learning.

3.4. Burnout Level among the Residents

Out of 46 respondents, 43.5% reported no burnout, 52.2 % experienced occasional burnouts to some symptoms, and 4.4% felt completely burned out and frustrated at work. Gender was found to be associated with perceived burnout by residents and the burnout rate among female residents showed statistically significant [OR (95% CI) 3.8 (1.03, 13.7),

p=0.044] (

Table 2). Where residents received dental degree, practicing years, and residents’ age were not associated with burnout (p>0.05).

4. Discussion

4.1. Factors Associated with Residents’ Perceptions of Virtual Learning

Statistically significant differences in perceptions of virtual learning and effectiveness were observed in the results and three factors are associated, including where dental residents obtained dental degrees outside of the U.S./Canada, the number of years of practice, and the participants’ age.

4.1.1. Residents Obtained Dental Degrees outside of the U.S./Canada

A key finding is that overall feeling about virtual learning modalities and perceived effectiveness of virtual learning are substantially influenced by where they received their dental degrees. Foreign-trained dentists are more likely to choose traditional in-person learning formats over virtual ones than their peers.

One of the primary reasons for their reluctance toward virtual learning is the differences in educational systems and pedagogical methods [

19]. Many countries’ dental educational systems emphasize in-person lecture-based learning and hands-on clinical experience. The shift to virtual learning could deviate from students’ familiar learning environment, and negatively influence their levels of engagement. Another notable reason is the technology familiarity [

20]. Foreign-trained residents might come from countries where digital infrastructure is less developed, so they may have fewer online learning experiences in their home countries and the transition to online learning would be more challenging for them as they need additional time to be familiar with online learning tools. Lastly, for many foreign-trained residents, creating a new professional community in a new country is as important as learning knowledge [

21]. In-person interactions can provide opportunities for real and valuable engagement with peers and faculty in networking, mentorship, and intercultural communication. The finding suggests that virtual learning modalities should adapt to foreign-trained learners’ preferences and backgrounds, incorporating diverse teaching methods to enhance engagement. Another possible reason for the international trained residents is that they have practiced longer before entering the program compared to the U.S. or Canada trained residents.

4.1.2. Years of Practice and Age

Residents’ views on virtual learning varied by age and years of practice. Younger, less experienced residents preferred virtual formats, while older ones with more experience favored in-person learning, particularly for literature reviews and case presentations. This finding reflects generational differences in learning styles and aligns with what the existing literature mentioned. Younger learners, born and raised in a digital age, naturally have a fluency with digital tools that enhances their adaptability to virtual learning environments and educational innovations [

22]. To accommodate this, educators should help older residents adapt by offering tech workshops, encouraging peer support, and providing materials in both digital and physical formats to create an inclusive learning environment.

Our study suggests that residents found virtual education methods like case presentations and literature reviews more effective than in-person learning (

p<0.05). This aligns with the preference for flexible virtual curricula on platforms such as Osmosis, Bite Medicine, Becoming A Doctor, and Sustaining Medical Education in a Lockdown Environment (SMILE) are preferred by students because of their virtual and flexible curriculum [

4]. However, residents still favored in-person over virtual meetings for their interactivity, supporting findings that in-person meetings are seen as more engaging than online ones [

23] and are unlikely to be replaced post-pandemic [

24].

4.2. Faculty Perceptions

Our study found no significant differences in dental faculty’s perceptions of virtual learning, indicating that the transition to virtual platforms did not impact their teaching quality. However, future qualitative research through faculty interviews could offer deeper insights.

4.3. Regulatory Focus Types

Kluger and Dijk noted that medical learners often emphasize prevention, focusing on error avoidance and safety [

25]. In contrast, those with a promotion focus prioritize growth and achievements [

26]. Our study found no clear preference for either regulatory focus, but residents with higher promotion scores were more interactive in virtual courses than in-person ones.

4.4. Burnout Among Residents

The study found a significant correlation between gender and burnout, with female residents experiencing higher burnout rates and greater work-life dissatisfaction compared to their male counterparts. This finding aligns with previous research on gender-specific burnout issues among

physicians [

16,

28,

29]

. Women are expected to be “superwomen” [

30]

, where managing time between professional responsibilities and personal life can be difficult.

Several factors contribute to burnout in female residents, such as lack of supportive mentors, dual-career challenges, limited childbearing years, salary inequity, fewer promotion opportunities, and higher rates of sexual harassment in the workplace [

31]

.

To combat burnout, particularly among female dental residents, it’s suggested that comprehensive wellness support, mentorship, and orientation programs be implemented [

32]. Orientation programs for incoming residents should include work expectations, stress-coping skills, and resources for managing stress. A formal mentorship program could focus on topics about professional development, work-life balance, well-being, and family-related challenges, rather than just work-related matters. Institutions should foster a supportive culture and enhance the well-being of women residents.

The study has limitations including its cross-sectional data from a single institution, which may affect generalizability. Self-reported data may also introduce bias, and different participant backgrounds could alter question interpretation. Future studies should incorporate qualitative data to fully capture the perceptions and experiences related to virtual learning

5. Conclusions

Our study enhances understanding of virtual learning in dental education post-pandemic, focusing on the influence of Regulatory Focus Theory (RFT) and burnout rates. It underscores the need for developing inclusive, effective virtual learning environments beyond emergency responses, using RFT to understand learner engagement and motivation. Additionally, addressing resident well-being to reduce burnout is crucial.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lockee, BB. Online education in the post-COVID era. Nature Electronics. 2021;4(1):5-6. [CrossRef]

- Wilcha, RJ. Effectiveness of Virtual Medical Teaching During the COVID-19 Crisis: Systematic Review. JMIR Med Educ. 2020;6(2):e20963. Epub 20201118. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larocque N, Shenoy-Bhangle A, Brook A, Eisenberg R, Chang YM, Mehta P. Resident Experiences With Virtual Radiology Learning During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Acad Radiol. 2021;28(5):704-10. Epub 20210215. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dost S, Hossain A, Shehab M, Abdelwahed A, Al-Nusair L. Perceptions of medical students towards online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national cross-sectional survey of 2721 UK medical students. BMJ Open. 2020;10(11):e042378. Epub 20201105. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mheissen S, Almuzian M, Wertheimer MB, Khan H. Global survey to assess preferences when attending virtual orthodontic learning sessions: optimising uptake from virtual lectures. Prog Orthod. 2021;22(1):47. Epub 20211221. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins ET, Shah J, Friedman R. Emotional responses to goal attainment: strength of regulatory focus as moderator. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1997;72(3):515-25. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang L, Cui Y, Wang X, Wang J, Du K, Luo Z. Regulatory Focus, Motivation, and Their Relationship With Creativity Among Adolescents. Front Psychol. 2021;12:666071. Epub 20210520. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li R, Liu H, Yao M, Chen Y. Regulatory Focus and Subjective Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Coping Styles and the Moderating Role of Gender. J Psychol. 2019;153(7):714-31. Epub 20190424. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-85. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt, T. D., Sinsky, C. A., Cipriano, P. F., Bhatt, J., Ommaya, A., West, C. P., & Meyers, D. Burnout among health care professionals: A call to explore and address this underrecognized threat to safe, high-quality care. National Academy of Medicine [Internet]. 2017. Available from: https://nam.edu/burnout-among-health-care-professionals-a-call-to-explore-and-address-this-underrecognized-threat-to-safe-high-quality-care/.

- Shah A, Wyatt M, Gourneau B, Shih G, De Ruyter M. Emotional exhaustion among anesthesia providers at a tertiary care center assessed using the MBI burnout survey. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24(5):620-4. Epub 20181119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanfilippo F, Noto A, Foresta G, Santonocito C, Palumbo GJ, Arcadipane A, et al. Incidence and Factors Associated with Burnout in Anesthesiology: A Systematic Review. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:8648925. Epub 20171128. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chi DL, Randall CL, Hill CM. Dental trainees’ mental health and intention to leave their programs during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2021;152(7):526-34. Epub 20210312. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkpatrick H, Wasfie T, Laykova A, Barber K, Hella J, Vogel M. Emotional Intelligence, Burnout, and Wellbeing Among Residents as a Result of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Am Surg. 2022;88(8):1856-60. Epub 20220408. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappa S, Ntella V, Giannakas T, Giannakoulis VG, Papoutsi E, Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901-7. Epub 20200508. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cevik H, Ungan M. The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and residency training of family medicine residents: findings from a nationwide cross-sectional survey in Turkey. BMC Fam Pract. 2021;22(1):226. Epub 20211115. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellner B, Holler M, Kirchler E, Schabmann A. Regulatory Focus Scale (RFS): Development of a scale to record dispositional regulatory focus. Swiss Journal of Psychology / Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Psychologie / Revue Suisse de Psychologie. 2007;66(2):109-16. [CrossRef]

- Sanders M, Fiscella K, Hill E, Ogedegbe O, Cassells A, Tobin JN, et al. Motivation to move fast, motivation to wait and see: The association of prevention and promotion focus with clinicians’ implementation of the JNC-7 hypertension treatment guidelines. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23(9):1752-7. Epub 20210810. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han Y, Chang Y, Kearney E. “It’s Doable”: International Graduate Students’ Perceptions of Online Learning in the U.S. During the Pandemic. J Stud Int Educ. 2022;26(2):165-82. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafar K, Ananthpur K, Venkatachalam L. Digital divide and access to online education: new evidence from Tamil Nadu, India. J Soc Econ Dev. 2023:1-21. Epub 20230320. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Achkar M, Dahal A, Frogner BK, Skillman SM, Patterson DG. Integrating Immigrant Health Professionals into the U.S. Healthcare Workforce: Barriers and Solutions. J Immigr Minor Health. 2023;25(6):1270-8. Epub 20230421. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tejedor S, Cervi L, Pérez-Escoda A, Jumbo FT. Digital Literacy and Higher Education during COVID-19 Lockdown: Spain, Italy, and Ecuador. Publications. 2020;8(4):48. PMID:. [CrossRef]

- Raby CL, Madden JR. Moving academic conferences online: Understanding patterns of delegate engagement. Ecol Evol. 2021;11(8):3607-15. Epub 20210215. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopec KT, Stolbach A. Transitioning to Virtual: ACMT’s 2020 Annual Scientific Meeting. J Med Toxicol. 2020;16(4):353-5. Epub 20200824. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui WL, Ye ML. An Introduction of Regulatory Focus Theory and Its Recently Related Researches. Psychology. 2017;8:837-47. [CrossRef]

- Kluger AN, Van Dijk D. Feedback, the various tasks of the doctor, and the feedforward alternative. Med Educ. 2010;44(12):1166-74. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watling C, Driessen E, van der Vleuten CP, Vanstone M, Lingard L. Understanding responses to feedback: the potential and limitations of regulatory focus theory. Med Educ. 2012;46(6):593-603. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMurray JE, Linzer M, Konrad TR, Douglas J, Shugerman R, Nelson K. The work lives of women physicians results from the physician work life study. The SGIM Career Satisfaction Study Group. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15(6):372-80. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Templeton K, C. Bernstein, J. Sukhera, L. M. Nora, C. Newman, H. Burstin, C. Guille, L. Lynn, M. L. Schwarze, S. Sen, and N. Busis. Gender-Based Differences in Burnout: Issues Faced by Women Physicians. National Academy of Medicine [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://nam.edu/gender-based-differences-in-burnout-issues-faced-by-women-physicians/.

- Murphy, B. Why do women resident physicians report more burnout Listen up American Medical Association2023. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/medical-residents/medical-resident-wellness/why-do-women-resident-physicians-report-more-burnout#:~:text=One%20contributor%20to%20burnout%20among,to%20prove%20that%20you%20belong.

- Verweij H, van der Heijden F, van Hooff MLM, Prins JT, Lagro-Janssen ALM, van Ravesteijn H, Speckens AEM. The contribution of work characteristics, home characteristics and gender to burnout in medical residents. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2017;22(4):803-18. Epub 20160920. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norvell J, Unruh G, Norvell T, Templeton KJ. Addressing Burnout Among Women Residents: Results from Focus Group Discussions. Kans J Med. 2023;16:83-7. Epub 20230424. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).