Submitted:

16 May 2024

Posted:

16 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- What are the preferences for elements of visual identity?

- What impact do visual identity elements have on consumer perception?

- What impact do visual identity elements have on consumer attitudes?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

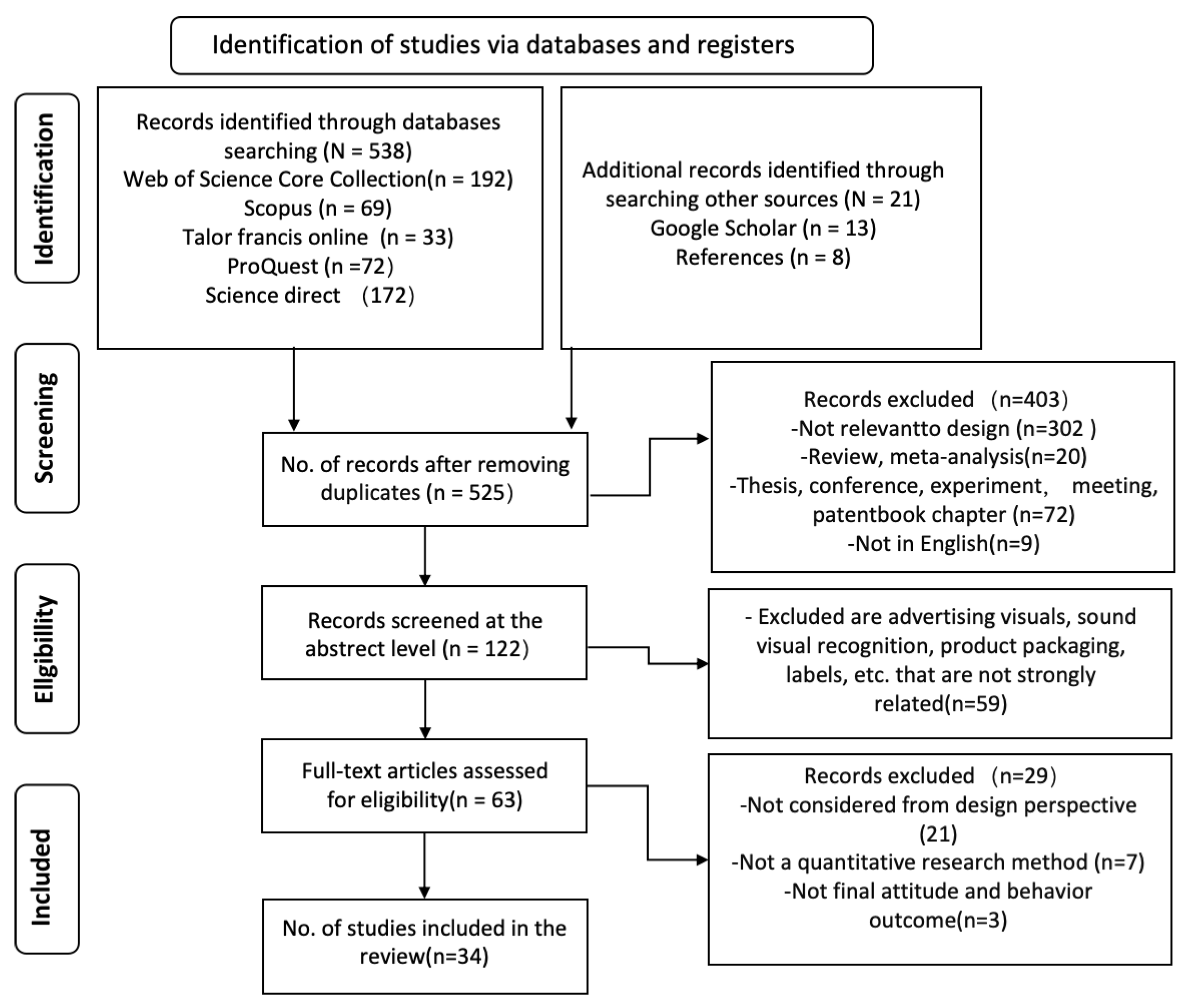

- On April 16, 2024, the authors used a comprehensive approach to search for articles related to our research topic. First, we used four electronic databases, including Web of Sciences, ProQuest, Scopus, and Elsevier, to conduct searches. The search strategy was based on recommendations from previous relevant reviews [50] and was guided by experienced librarians and academics. We used the following terms and operators for the abstract search: (brand visual identity OR Corporate visual identity OR visual identity OR brand visual OR logo) AND (consumer perception OR Consumer cognition OR Consumer conception OR Consumer experience OR consumer attitude OR perception OR attitude). The detailed search strategy can be found in the Supplementary Online Materials (see Appendix B). To identify studies that might be included in this systematic review, we carefully reviewed relevant review articles published before April 16, 2024. We then extensively searched all identified articles, utilising Google Scholar and reference lists to ensure all relevant articles were included [54]. In addition, we screened the reference lists of all identified articles for any publications that the initial computer search failed to detect. We ensured comprehensive field coverage and minimised possible biases and omissions [55].

2.2. Study Selection

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Quality Assessment

2.5. Data Items

3. Results

3.1. General Details and Study Design

3.2. Validated Research Hypotheses and Data Analysis

3.3. Findings and Practical Implications

4. Discussion

4.1. Brand Visual Identity Element Preference

4.2. Brand Visual Identity and Consumer Perception

4.3. Visual Identity and Consumer Attitude

4.4. Findings of Brand Managerial Implications

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

References

- Melewar, T. C.; Saunders, J. Global Corporate Visual Identity Systems: Using an Extended Marketing Mix. European Journal of Marketing 2000, 34, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Melewar, T. C.; Gupta, S. Linking Corporate Logo, Corporate Image, and Reputation: An Examination of Consumer Perceptions in the Financial Setting. Journal of Business Research 2014, 67, 2269–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, B.; Morais, R.; de Lima, E. S. The Personality of Visual Elements: A Framework for the Development of Visual Identity Based on Brand Personality Dimensions. International Journal of Visual Design 2024, 18, 67–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van den Bosch, A. L. M.; Elving, W. J. L.; de Jong, M. D. T. The Impact of Organisational Characteristics on Corporate Visual Identity. Eur. J. Market. 2006, 40, 870–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C.; Saunders, J.; Balmer, J. M. T. Cause, Effect and Benefits of a Standardised Corporate Visual Identity System of UK Companies Operating in Malaysia. Eur. J. Market. 2001, 35, 414–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C.; Saunders, J. Global Corporate Visual Identity Systems: Standardization, Control and Benefits. International Marketing Review 1998, 15, 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B. J.; McQuarrie, E. F.; Griffin, W. G. How Visual Brand Identity Shapes Consumer Response. Psychology & Marketing 2014, 31, 225–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjansola, A.-M.; Lipponen, J.; Vehkalahti, K.; Aula, H.-M.; Pirttilä-Backman, A.-M. From the Brand Logo to Brand Associations and the Corporate Identity: Visual and Identity-Based Logo Associations in a University Merger. J Brand Manag 2021, 28, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bosch, A. L. M.; De Jong, M. D. T.; Elving, W. J. L. How Corporate Visual Identity Supports Reputation. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 2005, 10, 108–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. J.; Balmer, J. M. T. Visual Identity: Trappings or Substance? European Journal of Marketing 1997, 31, 366–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Gong, X.; Wang, J. Simple = Authentic: The Effect of Visually Simple Package Design on Perceived Brand Authenticity and Brand Choice. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butcher, J.; Pecot, F. Visually Communicating Brand Heritage on Social Media: Champagne on Instagram. Journal of Product &Amp; Brand Management 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Ma, J. The Effectiveness of the Destination Logo: Congruity Effect between Logo Typeface and Destination Stereotypes. Tourism Manage. 2023, 98, 104772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirby, A.; Kent, A. Architecture as Brand: Store Design and Brand Identity. Journal of Product &Amp; Brand Management 2010, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X. Business Model Evolution: In Search of Dynamic Consistency. Long Range Planning 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C. Measuring Visual Identity: Amulti-construct Study. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 2001, 6, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Chen, S.; Chen, L. Effect of clothing brand image on consumer purchase and communication willingness on WeChat platform. Fangzhi Xuebao/J. Text. Res. 2020, 41, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C.; Hussey, G.; Srivoravilai, N. Corporate Visual Identity: The Re-Branding of France Télécom. J Brand Manag 2005, 12, 379–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P. Influence of Brand Signature, Brand Awareness, Brand Attitude, Brand Reputation on Hotel Industry’s Brand Performance. International Journal of Hospitality Management 2019, 76, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, Y.; Lee, H. A Sound Brand Identity Design: The Interplay between Sound Symbolism and Typography on Brand Attitude and Memory. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2022, 64, 102724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buschgens (, M.; Figueiredo (, B.; Blijlevens (, J. Designing for Identity: How and When Brand Visual Aesthetics Enable Consumer Diasporic Identity. European Journal of Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Meyvis, T. Effects of Brand Logo Complexity, Repetition, and Spacing on Processing Fluency and Judgment. Journal of Consumer Research 2001, 28, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmon-Kizer, T. The Role of Logo Recoloring on Perceptual Fluency in Cause-Related Marketing Campaigns. Journal of Promotion Management 2019, 25, 959–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A. Y.; Labroo, A. A. The Effect of Conceptual and Perceptual Fluency on Brand Evaluation. Journal of Marketing Research 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; Yoon, M.; Lee, J. The Influence of Brand Color Identity on Brand Association and Loyalty. JPBM 2019, 28, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, H. Ethnic Restaurants’ Outdoor Signage: The Effect of Colour and Name on Consumers’ Food Perceptions and Dining Intentions. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkibay, S.; Ozdogan, F. B.; Ermec, A. Corporate Visual Identity: A Case in Hospitals. Health Mark Q 2007, 24, (3–4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Wu, Z.; Hu, L.; Jia, Q. The Visual Naturalness Effect: Impact of Natural Logos on Brand Personality Perception. International Journal of Consumer Studies 2023, 47, 1351–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwankwo-Ojionu, C. E.; Adzharuddin, N. A.; Waheed, M.; Khir, A. M. Impact of Strategic Ambiguity Tagline on Billboard Advertising on Consumers Attention. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Childers, T. L.; Jass, J. All Dressed Up with Something to Say: Effects of Typeface Semantic Associations on Brand Perceptions and Consumer Memory. Journal of Consumer Psychology 2002, 12, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kaur, K. R. Investigating the Effects of Consistent Visual Identity on Social Media. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2021, 13, 236–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muellner, B.; Kocher, B.; Crettaz, A. The Effects of Visual Rejuvenation through Brand Logos. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, F. M.; Osgood, C. E. A Cross-Cultural Study of the Affective Meanings of Color. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 1973, 4, 135–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wänke, M. , Herrmann, A., & Schaffner, D. Brand name influence on brand perception. Psychology and Marketing. [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P. , Nazarian, A., Ziyadin, S., Kitchen, P., Hafeez, K., Priporas, C., & Pantano, E. (2020). Co-creating brand image and reputation through stakeholder’s social network. Journal of Business Research, 2020,114, 42-59. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Kelley, G. E.; O’Donnell, K. A. An Investigation of Consumer Reactions to the Use of Different Brand Names. Journal of Product & Brand Management 1998, 7, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, R. Consumer Brand Enmeshment: Typography and Complexity Modeling of Consumer Brand Engagement and Brand Loyalty Enactments. Journal of Business Research 2015, 68, 1953–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, C. L. The Connotative Dimensions of Selected Display Typefaces. Information Design Journal 1982, 3, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengyao Yu; Yue Ma; Changhua He; Jun Zheng. Research on Tourist Satisfaction with Lijiang’s Ancient City Image Based on the IPA Analysis Method. In Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Economic Management and Cultural Industry (ICEMCI 2022); Atlantis Press, 2022; pp 1201–1209. [CrossRef]

- Pizzi, G.; Scarpi, D. The Effect of Shelf Layout on Satisfaction and Perceived Assortment Size: An Empirical Assessment. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2016, 28, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, A. S.; Son, S.; Walsh, P.; Park, J. The Influence of Logo Change on Brand Loyalty and the Role of Attitude Toward Rebranding and Logo Evaluation. Sport Marketing Quarterly 2021, 30, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiq, M. R.; Rai, I. H.; Hussain, S. The Impact of Logo Shapes Redesign on Brand Loyalty and Repurchase Intentions through Brand Attitude. International Review of Management and Marketing 2020, 10, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, A.; Kinsey, D. F. An Examination of Consumers’ Subjective Views That Affect the Favorability of Organizational Logos: An Exploratory Study Using Q Methodology. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2019, 22, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, J. D. A Study of Multi-Sensory Experience and Color Recognition in Visual Arts Appreciation of People with Visual Impairment. Electronics 2021, 10, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, T.; Wu, J.; Meng, H. The Effect of Digital Fashion Visual Symbol Perception on Consumer Repurchase Intention: A Moderated Chain Mediation Model. J. Fash. Mark. Manage. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Calvo, A.; Serrano-Montes, J. L. Influence of Logos on Social Attitudes toward the Landscape of Protected Areas: The Case of National and Natural Parks in Spain. Land 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnardel, V.; Séraphin, H.; Gowreesunkar, V.; Ambaye, M. Empirical Evaluation of the New Haiti DMO Logo: Visual Aesthetics, Identity and Communication Implications. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management 2020, 15, 100393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewer, J. B.; Zhao, Z.; Desmond, J. E.; Glover, G. H.; Gabrieli, J. D. E. Making Memories: Brain Activity That Predicts How Well Visual Experience Will Be Remembered. Science 1998, 281, 1185–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y. Research on the Best Visual Search Effect of Logo Elements in Internet Advertising Layout. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science 2019, 2, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, M. K.; Johansen, T. S. Organizational-Level Visual Identity: An Integrative Literature Review. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 2021, 27, 441–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C.; Mulrow, C. D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J. M.; Akl, E. A.; Brennan, S. E.; Chou, R.; Glanville, J.; Grimshaw, J. M.; Hróbjartsson, A.; Lalu, M. M.; Li, T.; Loder, E. W.; Mayo-Wilson, E.; McDonald, S.; McGuinness, L. A.; Stewart, L. A.; Thomas, J.; Tricco, A. C.; Welch, V. A.; Whiting, P.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, N.; Soh, K. G.; Abdullah, B.; Huang, D. Effects of Plyometric Training on Measures of Physical Fitness in Racket Sport Athletes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. PeerJ 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, N.; Soh, K. G.; Abdullah, B. B.; Huang, D. Does Motor Imagery Training Improve Service Performance in Tennis Players? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Behavioral Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, A. W.; Paul, J.; Trott, S.; Guo, C.; Wu, H. H. Two Decades of Research on Nation Branding: A Review and Future Research Agenda. International Marketing Review 2019, 38, 46–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H. Factors Determining City Brand Equity—A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative Research Synthesis: Methodological Guidance for Systematic Reviewers Utilizing Meta-Aggregation. JBI Evidence Implementation 2015, 13, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munn, Z.; Aromataris, E.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; Porritt, K.; Farrow, J.; Lockwood, C.; Stephenson, M.; Moola, S.; Lizarondo, L.; McArthur, A.; Peters, M.; Pearson, A.; Jordan, Z. The Development of Software to Support Multiple Systematic Review Types: The Joanna Briggs Institute System for the Unified Management, Assessment and Review of Information (JBI SUMARI). JBI Evidence Implementation 2019, 17, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Górska-Warsewicz, H.; Kulykovets, O. Hotel Brand Loyalty—A Systematic Literature Review. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majer, J. M.; Henscher, H. A.; Reuber, P.; Fischer-Kreer, D.; Fischer, D. The Effects of Visual Sustainability Labels on Consumer Perception and Behavior: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Literature. Sustainable Production and Consumption 2022, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.; Yang, H. Ethnic Restaurants’ Outdoor Signage: The Effect of Colour and Name on Consumers’ Food Perceptions and Dining Intentions. Br. Food J. 2023, 125, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H. The Shape of Premiumness: Logo Shape’s Effects on Perceived Brand Premiumness and Brand Preference. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2023, 75, 103516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S. W. (Sean); Williams, A. Visual Congruity in Jersey Sponsorship: The Effect of Created Brand-Color Congruity on Attitude toward Sponsor. Sport Marketing Quarterly 2023, 32, 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, H. Alignment of Images and Text in Tourism Logos: Influence on Attitude toward Tourist Destinations. Social Behavior and Personality 2022, 50, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, L.; Wang, Q. Uppercase Premium Effect: The Role of Brand Letter Case in Brand Premiumness. Journal of Retailing 2022, 98, 335–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Attri, R. Physimorphic vs. Typographic Logos in Destination Marketing: Integrating Destination Familiarity and Consumer Characteristics. Tourism Management 2022, 92, 104544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinitha, V. U.; Kumar, D. S.; Purani, K. Biomorphic Visual Identity of a Brand and Its Effects: A Holistic Perspective. J. Brand Manag. 2021, 28, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, F.; Jin, X.; Wu, B.; Zhao, T.; Ma, T. Shape-Trait Consistency: The Matching Effect of Consumer Power State and Shape Preference. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 615647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septianto, F.; Paramita, W. Cute Brand Logo Enhances Favorable Brand Attitude: The Moderating Role of Hope. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2021, 63, 102734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meiting, L.; Hua, W. Angular or Rounded? The Effect of the Shape of Green Brand Logos on Consumer Perception. Journal of Cleaner Production 2021, 279, 123801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joana, C. M.; Fonseca, B.; Martins, C. Brand Logo and Brand Gender: Examining the Effects of Natural Logo Designs and Color on Brand Gender Perceptions and Affect. Journal of Brand Management 2021, 28, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koentjoro, M. S. The Effects of The New Logo on People’s Brand Awareness and Perception of Quality of Indonesia’s Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises. Journal of Marketing Development and Competitiveness 2021, 15, 29–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, E.; Yang, S.; Romaniuk, J.; Beal, V. Building a Unique Brand Identity: Measuring the Relative Ownership Potential of Brand Identity Element Types. J Brand Manag 2020, 27, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. Q.; Choi, S.; Mattila, A. S. Love Is in the Menu: Leveraging Healthy Restaurant Brands with Handwritten Typeface. Journal of Business Research 2019, 98, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P. Influence of Brand Signature, Brand Awareness, Brand Attitude, Brand Reputation on Hotel Industry’s Brand Performance. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 76, 271–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rihn, A.; Wei, X.; Khachatryan, H. Text vs. Logo: Does Eco-Label Format Influence Consumers’ Visual Attention and Willingness-to-Pay for Fruit Plants? An Experimental Auction Approach. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 2019, 82, 101452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Kaur, K. Connecting the Dots between Brand Logo and Brand Image. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Adm. 2019, 11, 68–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, N.; Lurie, N. H. The Case for Compatibility: Product Attitudes and Purchase Intentions for Upper versus Lowercase Brand Names. J. Retail. 2018, 94, 393–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Del Ponte, P. New Brand Logo Design: Customers’ Preference for Brand Name and Icon. J Brand Manag 2017, 24, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Grinsven, B.; Das, E. Logo Design in Marketing Communications: Brand Logo Complexity Moderates Exposure Effects on Brand Recognition and Brand Attitude. Journal of Marketing Communications 2016, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, J. C.; de Carvalho, L. V.; Torres, A.; Costa, P. Brand Logo Design: Examining Consumer Response to Naturalness. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2015, 24, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavanagh, K. V.; Forestell, C. A. The Effect of Brand Names on Flavor Perception and Consumption in Restrained and Unrestrained Eaters. Food Quality and Preference 2013, 28, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Rodriguez, L.; Sar, S. The Influence of Logo Design on Country Image and Willingness to Visit: A Study of Country Logos for Tourism. Public Relat. Rev. 2012, 38, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagtvedt, H. The Impact of Incomplete Typeface Logos on Perceptions of the Firm. Journal of Marketing 2011, 75, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bresciani, S.; Del Ponte, P. New Brand Logo Design: Customers’ Preference for Brand Name and Icon. J. Brand Manag. 2017, 24, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Z.; Plocher, T.; Kiff, L. Touch Screen User Interfaces for Older Adults: Button Size and Spacing; Stephanidis, C., Ed.; Springer, Berlin (2007; Vol. 4554. [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M. F.; Page Winterich, K.; Mittal, V. Do Logo Redesigns Help or Hurt Your Brand? The Role of Brand Commitment. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2010, 19, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varieties of Memory and Consciousness: Essays in Honour of Endel Tulving; Roediger, H. L., Craik, I., Fergus, Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Yu, F.; Ding, X. Circular-Looking Makes Green-Buying: How Brand Logo Shapes Influence Green Consumption. Sustainability 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundar, A.; Noseworthy, T. J. Place the Logo High or Low? Using Conceptual Metaphors of Power in Packaging Design. Journal of Marketing 2014, 78, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, O. Photography and Travel Brochures: The Circle of Representation. Tourism Geographies 2003, 5, 305–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y. (Lisa); Wu, L.; Shin, J.; Mattila, A. S. Visual Design, Message Content, and Benefit Type: The Case of A Cause-Related Marketing Campaign. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research 2020, 44, 761–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, O. C. S.; Trung, N. T.; Rieber, R. W. Cross-Cultural Comparisons on Psychosemantics of Icons and Graphics. International Journal of Psychology 1990, 25, 77–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labrecque, L. I.; Patrick, V. M.; Milne, G. R. The Marketers’ Prismatic Palette: A Review of Color Research and Future Directions. Psychology & Marketing 2013, 30, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luffarelli, J.; Mukesh, M.; Mahmood, A. Let the Logo Do the Talking: The Influence of Logo Descriptiveness on Brand Equity. Journal of Marketing Research 2019, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T. J.; Hewett, K.; Roth, M. S. Managing Images in Different Cultures: A Cross-National Study of Color Meanings and Preferences. Journal of International Marketing 2000, 8, 90–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Xu, F.; Jiang, Y. The Colorful Company: Effects of Brand Logo Colorfulness on Consumer Judgments. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1610–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, R.; Ghoneim, A.; Irani, Z.; Fan, Y. A Brand Preference and Repurchase Intention Model: The Role of Consumer Experience. Journal of Marketing Management 2016, 32, 1230–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Zhu, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, L. Vividly Warm: The Color Saturation of Logos on Brands’ Customer Sensitivity Judgment. Color Research &Amp; Application 2021, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, E.; Han, Y.; Nam, M. How You See Yourself Influences Your Color Preference: Effects of Self-construal on Evaluations of Color Combinations. Psychology &Amp; Marketing 2020, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. Reflecting on Nation Image and Perceptions of Nation Brand: Scottish-Themed Pubs, Bars and Restaurants Outside of Scotland. Journal of Consumer Culture 2024, 24, 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregersen, M. K.; Johansen, T. S. Corporate Visual Identity: Exploring the Dogma of Consistency. CCIJ 2018, 23, 342–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, P. W.; Cote, J. A.; Leong, S. M.; Schmitt, B. Building Strong Brands in Asia: Selecting the Visual Components of Image to Maximize Brand Strength. International Journal of Research in Marketing 2003, 20, 297–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govers, P.; Schoormans, J. Product Personality and Its Influence on Consumer Preference. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2005, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Sun, Q.; Grewal, R.; Li, S. Brand Name Types and Consumer Demand: Evidence from China’s Automobile Market. Journal of Marketing Research 2018, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamantopoulos, A.; Balabanis, G. Brand Origin Identification by Consumers: A Classification Perspective. Journal of International Marketing 2008, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salciuviene, L.; Ghauri, P. N.; Streder, R. S.; Mattos, C. D. Do Brand Names in a Foreign Language Lead to Different Brand Perceptions? Journal of Marketing Management 2010, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L. Analysis of the Value of Brand Equity from the Perspective of Consumer Psychology. Open Journal of Social Sciences 2018, 06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajardo, T. M.; Zhang, J.; Tsiros, M. The Contingent Nature of the Symbolic Associations of Visual Design Elements: The Case of Brand Logo Frames. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 43, 549–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu Lo, C. K. Y.; Burton, S.; Lam, R.; Nesbit, P. Which Bag? Predicting Consumer Preferences for a Luxury Product With a Discrete Choice Experiment. Australasian Marketing Journal 2021, 29, 329–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, W.-S.; Oh, J.-H.; Park, H.-J.; Ahn, S.-W.; Hong, S.-Y.; Kim, N.-I. Historical Difference between Traditional Korean Medicine and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Neurological Research 2007, 29 (sup1), 5–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fransen, M. L.; Fennis, B. M.; Pruyn, A. T. H. Matching Communication Modalities: The Effects of Modality Congruence and Processing Style on Brand Evaluation and Brand Choice. Communication Research 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Huang, S.; Hallak, R.; Mao, L. Chinese Consumers’ Brand Personality Perceptions of Tourism Real Estate Firms. Tourism Management 2016, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, M. F.; Kim, H.-S.; Jung, J. The Effects of Facial Image and Cosmetic Usage on Perceptions of Brand Personality. Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal 2008, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, L.; Li, J.; Mizerski, D.; Soh, H. Self-congruity, brand attitude, and brand loyalty: a study on luxury brands. European Journal of Marketing 2012, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, N. Luxury Implications of Showcasing a Product with Its “Cast” Shadow. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2016, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lieven, T.; Grohmann, B.; Herrmann, A.; Landwehr, J. R.; van Tilburg, M. The Effect of Brand Design on Brand Gender Perceptions and Brand Preference. European Journal of Marketing 2015, 49, 146–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrão, C. M. The Psychology of Colors in Branding. Latin American Journal of Development 2022, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Xu, J.; Chen, Y. Food Interactive Packaging Design Method Based on User Emotional Experience. Scientific Programming 2022, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suham-Abid, D.; Vilà, N. Airline Service Quality and Visual Communication. The TQM Journal 2019, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Melewar, T. C.; Gupta, S. Corporate Logo: History, Definition, and Components. International Studies of Management & Organization 2017, 47, 176–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnurr, B.; Stokburger-Sauer, N. The Effect of Stylistic Product Information on Consumers’ Aesthetic Responses. Psychology &Amp; Marketing 2016, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloch, P.; Brunel, F. F.; Arnold, T. J. Individual Differences in the Centrality of Visual Product Aesthetics: Concept and Measurement. Journal of Consumer Research 2003, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Gunn, F. The Impact of Image Dimensions toward Online Consumers’ Perceptions of Product Aesthetics. Human Factors and Ergonomics in Manufacturing &Amp; Service Industries 2016, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevener, Z. A Semantic Differential Study of the Influence of Aesthetic Properties on Product Pleasure. Proceedings of the 2003 International Conference on Designing Pleasurable Products and Interfaces 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roosens, B.; Dens, N.; Lievens, A. Effects of Partners’ Communications on Consumer Perceptions of Joint Innovation Efforts. International Journal of Innovation Management 2019, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroudi, P.; Melewar, T. C.; Gupta, S. Linking Corporate Logo, Corporate Image, and Reputation: An Examination of Consumer Perceptions in the Financial Setting. Journal of Business Research 2014, 67, 2269–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, M. F.; Winterich, K. P.; Mittal, V. How Re-designing Angular Logos to Be Rounded Shapes Brand Attitude: Consumer Brand Commitment and Self-construal. Journal of Consumer Marketing 2011, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luffarelli, J.; Stamatogiannakis, A.; Yang, H. The Visual Asymmetry Effect: An Interplay of Logo Design and Brand Personality on Brand Equity. Journal of Marketing Research 2018, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Fu, S.; Huan, T.-C. (T. C.). Exploring the Influence of Tourists’ Happiness on Revisit Intention in the Context of Traditional Chinese Medicine Cultural Tourism. Tourism Management 2023, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Jiang, Z. Chinese Cultural Element in Brand Logo and Purchase Intention. Marketing Intelligence &Amp; Planning 2022, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yang, M. Color Image Knowledge Model Construction Based on Ontology. Color Research &Amp; Application 2019, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, J.; Fang, M.; Tang, L.; Pan, Y. A Study and Analysis of the Relationship between Visual-Auditory Logos and Consumer Behavior. Behav Sci (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fetscherin, M.; Diamantopoulos, A.; Chan, A. K. K.; Abbott, R. T. How Are Brand Names of Chinese Companies Perceived by Americans? Journal of Product &Amp; Brand Management 2015, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Kandampully, J. The Role of Emotional Aspects in Younger Consumer-brand Relationships. Journal of Product & Brand Management 2012, 21, 98–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melewar, T. C.; Bassett, K.; Simões, C. The Role of Communication and Visual Identity in Modern Organisations. Corporate Communications: An International Journal 2006, 11, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittard, N.; Ewing, M.; Jevons, C. Aesthetic Theory and Logo Design: Examining Consumer Response to Proportion across Cultures. International Marketing Review 2007, 24, 457–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M.; AlShebil, S.; Bishop, M. Cognitive and Emotional Processing of Brand Logo Changes. JPBM 2015, 24, 745–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, B. J.; McQuarrie, E. F.; Griffin, W. G. The Face of the Brand: How Art Directors Understand Visual Brand Identity. Journal of Advertising 2014, 43, 318–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Article | Year | Authors | Q1 | Q2 | Q3 | Q4 | Q5 | Q6 | Q7 | Q8 | Q9 | Q10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | 2024 | Andrade et al. | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [60] | 2023 | Song & Yang | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [61] | 2023 | R. Li et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [13] | 2023 | F. Li & Ma, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [28] | 2023 | T. Chen et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [62] | 2023 | Son & Williams, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [63] | 2022 | Y. Chen et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [64] | 2022 | Yu et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [65] | 2022 | Roy & Attri, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [66] | 2021 | Vinitha et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [67] | 2021 | Yao et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [68] | 2021 | Septianto& Paramita, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [69] | 2021 | Meiting & Hua, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [41] |

2021 | Williams et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [70] | 2021 | Joana et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [71] | 2021 | Koentjoro, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [42] | 2020 | Rafiq et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes |

| [72] | 2020 | Ward et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [73] | 2019 | Liu et al. | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [43] | 2019 | Chung & Kinsey, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes |

| [74] | 2019 | Foroudi, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [75] | 2019 | Rihn et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes |

| [23] | 2019 | Harmon-Kizer, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [25] | 2019 | Jin et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [76] | 2019 | Kaur & Kaur, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [77] | 2018 | Wen & Lurie, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [78] | 2017 | Bresciani & Del Ponte, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | No | Yes | Yes |

| [79] | 2016 | van Grinsven & Das, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes |

| [80] | 2015) | Machado et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [2] | 2014 | Foroudi et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [32] | 2013 | Muellner et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [81] | 2013 | Cavanagh & Forestell, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [82] | 2012 | S. Lee et al. | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| [83] | 2011 | Hagtvedt, | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Article | Type of study | Independent variables | mediating variable | Dependent variables | Sample Population | Element |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | Survey | Personality of Visual Elements (POVE) | Brand Personality (BP) | Visual Identity (VI) | Participant: 127 | Logo(shape) typography color |

| [60] | experiment | Signage colour (SC) Restaurant name (RN) |

consumers perceived (CP) Food tastiness (FT) Food healthiness (FH) |

Dining intentions (DI) | Participant: 24 English university students | Brand color Brand logo |

| [61] | Experiment | Logo shape (LS) | psychological distance (PD) Perceived brand status (PBS) consumption goals (GS) |

brand premiumness(BP) favorable attitude (FA) |

Participant1: 120 Participant2: 200 Participant13: 444 |

Logo shape (angle, circle, combination) |

| [13] | Experiment | Logo typeface (LT) Destination stereotype (DS) -warm stereotype (WS) -competent stereotype (CS) |

Processing fluency (PF) Need for cognition (NFC) Attitude towards destination (ATD) |

Travel intention (TI) | Participant1a: 263 Chinese Participant2a: 228 Participant2b: 197 Participant3: 300 |

typeface |

| [28] | Experiment | brand logo naturalness (BLN) | Perception of Logo’s authenticity (POLA) Product Type (PT) |

sincere personality perception (SPP) | Participant1: 72 (beijing wuhan) Participant2: 176 (beijing wuhan) Participant3: 184 non-student Participant4: 216 (17-55 years old) |

Logo Naturalness |

| [62] | Experiment | color congruity(C) team identification (TI) |

perceived sponsor support (PPS) | attitude toward sponsor brand (ATSB) | Participant: 383 (MTurk) | brand-color |

| [63] | Experiment | Alignment logo (AL) | Information Processing Fluency (IPF) Personal need for structure (PNFS) |

attitude toward tourist destination (ATTD) | Participant1: 120 (72 women, 48 men; 0age = 27.16 years, 6’ = 7.01, range = 18–40) Participant2: 120 (80 women and 40 men; 0age =24.12 years, 6’=6.65, range=18–40) Participant3: 120 (72 women, 48 men; 0age =21.35 years, 6’=2.83, range=18–27) |

Typography logo |

| [64] | Experiment | letter case (LC) product’s social visibility (PSV) |

perceived conspicuousness (PC) | perceptions premiumness (PP) | Participant1a: 52 university students Participant1b: 154 university students Participant2a: 270 Participant2b: 253 Participant3: 39 Participant4: 108 |

letter |

| [65] | Experiment | physimorphic logos (PL) typographic logo (TL) |

destination familiarity (DF) Processing fluency (PF) cognitive style (CS) |

attitudes towards destination (ATD) visit intentions (VI) |

Participant1: 172 (18 and 45 years) (approximately 40 respondents per cell; 45% female; mean age = 32 years). Participant2: 153 (approx. 75 per cell; 47% female; mean age = 31 years) Participant3 : 262(46% female; mean age = 33 years). |

logo |

| [66] | Experiment | Biomorphic Visual Identity (BVI ) type of product (TOP) |

perceived sustainability (PS) perceived credibility (PI) |

brand likability (BL) PI |

Participant1: 30 undergraduates Participant2: 33 students Participant3: 309 |

brand names logo, taglines, imagery, and color schemes |

| [67] | Experiment | Consumer power state (CPS) |

Perceived competence and warmth (PCAW) | shape preference (SP) | Participant1a: 311 workers Participant1b: 233 adult consumers Participant2a: 149 workers Participant2b: 166 undergraduates Participant3: 288 workers Participan4: 112 Participant5: 246 undergraduates |

Logo Shape |

| [68] | Experiment | Cute brand logo (CBL) | experiencing hope (EP) potential growth (PG) |

Brand attitude (BA) | Participant1: 299 U.S Participant2: 200 U.S |

virtual brand logos |

| [69] | Experiment | Shape feature (SF) | gender perception (GP) Warm perception (WP) |

green perceptiongg (GP) | Participant: 156 |

Logo Shape |

| [41] |

Experiment | Logo Change (LC) | Brand Loyalty and Repurchase Intentions through Brand Attitude | BL Attitude Toward Rebranding (ATR) Logo Evaluation (LE) |

Participant: 494 (M-Turk) 193 women, 301 men: 18 and 44 years old | Logo |

| [70] | Survey | Logo design (LD) Logo color (LC) |

logo masculinity (LM) logo femininity (LF) consumer’s femininity (CF) consumer’s masculinity (CM) |

affective toward logo (ATL) | Participant: 240 | Logo Color |

| [71] | Survey | Logo intrinsic properties (LIP) Logo entrensic properties (LEP) |

Ministry brand awareness (MBA) | Ministry perceived quality (MPQ) | Participant: 200 | Logo |

| [42] | Survey | Logo shape redesign (LSR) |

BA | BL Repurchase intention (RI) |

Participant: 518 | Color combination Font size Graphic icon |

| [72] | Survey | brand identity element types (BIET) | Competitive Intensity (CI) | consumer memory (CM) | Participant: 26,755 | Character Logo Logotype Product form Pack Image on pack Taglines Colour |

| [73] | Experiment | handwritten typeface (HT) | human touch (HT) love |

consumer responses (CR) | Participant: 185 U.S Participant: 191 U.S |

handwritten typeface |

| [43] | Survey |

Bright Colors (BC) Living Creatures (WL) Perception of Movement (POM) |

attractive | Brand Favorability (BF) | Participant: 40 |

Logo (color, living creatures , Movement) |

| [74] | Survey | Brand signature (BS) BL |

BA Awareness of consumers (AOC) Brand reputation (BR) |

Brand performance (BP) | Participant: 520 | Brand name Typeface Design Color |

| [75] | Experiment | eco-labels | valuation of eco-labeled products (VOLP) visual attention (VA) |

consumer behavior (CB) | Participant1: 82 Participant2: 53 |

Text Logo |

| [23] | Survey | Brand Logo Recoloring (BLR) | Conceptual Fit (CF) Brand Logo Evaluation (BLE) |

CRM Effectiveness (CRME) | Participant: 452(21-24 years old) | Color |

| [25] | Survey | brand’s color identity (BCI) | brand association (BA) brand self-identification (BSIÅ) |

brand loyalty (BL) | FGI:3 Color experts and 15 college students Participant: 781 (406 men and 375 women) |

Brand color |

| [76] | Survey | Brand logo (BL) | Brand Personality (BP) brand familiarity (BF) |

Brand image (BI) |

Participant: 816 | logo |

| [77] | Experiment | Uppercase Brand Names (UBN) Lowercase Brand Names (LBN) |

gender benefit (BG) | Product Attitudes (PA) Purchase Intentions (PI) |

Participant1: 127 U.S. Participant2: 172 undergraduates Participants3: 123female Participant4: 130 MTurk Participant5: 524 undergraduates |

Uppercase Brand name Lowercase Brand Name |

| [78] | Experiment | brand name (BN) brand icon (BI) |

customers’ preference (CP) | logo attractiveness (LA) | Participant: 93 | brand name brand icon |

| [79] | Experiment | Brand logo complexity (BLC) | moderates’ exposure (ME) | brand recognition (BR) BA |

Participant1: 68 (42.6% male, Mage ¼ 30.22, SDage ¼ 13.49, range: 16 – 60) Participant2: 164 (38.5% men and 61.5% women) |

Brand logo complexity |

| [80] | Experiment | natural logo (NL) abstract designs (AD) organic logo (OL) cultural designs (CD) |

emotional response (ER) | Participant1: 113 (18 and 60 years, M = 34.7, SD = 9.6) Participant2: 107 (18 and 73 years, M = 37.6, SD = 12.7) |

logo | |

| [2] | Survey | Corporate logo (CL) -Corporate logo Name (CN) Corporate logo Typeface (ClT) Corporate Logo Design (CLD) Corporate Logo Color (CLC) |

Attitude towards Advertisements (ATA) Company Familiarity (CF) Company Recognizability (CR) |

Corporate Image (CI) Corporate Reputation (CR) |

Participant: 1352 | Logo Name Typeface Design Color |

| [32] | Experiment | -Logo attravtiveness (LA) Logo complexity (LC) Logo appropriateness (LA) Logo familiarity (LF) |

Logo attitude (LA) brand modernity (BM) brand attitude (BA) |

brand loyalty (BL) | Participant: 385 | Logo |

| [81] | survey | Brand name (BN) | food choice (FC) food intake (FI) |

flavor perception (FP) |

Participant: 99(18 and 23 years) | Brand name |

| [82] | Survey | people’s evaluation (PE) |

students’ pre-existing knowledge (SEK) | country image (CI) visit country (VC) |

Participant: 466 undergraduate students | logo |

| [83] | Experiment | incomplete typeface logo (ITL) | Consumers perceived (PC) -logo Interestingness (LI) -logo clarity (LC) |

favorable attitude (FA) | Participant1: 206(1a : 71, 1b: 67 and 1c : 69,) (44% men, Mage = 45 years) Participant2: 135 (Qualtrics panel: 59% men, Mage = 46 years) Participant3: 120 (Qualtrics panel: 56% men, Mage = 45) |

logo |

| Article | Hypotheses | Measurement Items | Data Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| [3] | / | 10 VI (a scale of 1 (most associable) to 5 (least associable))— 17tems | ANOVA |

| [60] | SC→ FT SC →FH SC →DI RN→ FT RN →FH SC→ DI FT →DI FH →DI |

12 tems (7-point semantic scale) FT) — 4tems; FH) — 5 tems; DI) — 3 tems | Two-way analysis of covariance confirmatory factor analysis PROCESS |

| [61] | LS→PD→BP (+) angular logo→ FA (+) |

14 items (7-point Likert scale) LS—3 items; BP—4 items; 2items; PD—1 items GS—4 items |

archival dataset analysis one-way ANOVA |

| [13] | LT match DS →ATD (+) (WS) HT→ATD (+) (CS) machine-written→ATD (+) LT and DS→DS (+) (WS) HT→TI (+) (CS) machine-written→TI (+) LT→PF→DS→TI DS and LT →PF and TAT→TI DS and LT→PF→will be stronger NFC (-) than NFC(+) |

Study 1a (7-point Likert scale) ATD—8 tems Study 2a (9-point scale) LT—3 tems Study 2b (7-point Likert scale) ATD—8 tems Study 3 (7-point Likert scale) ATD—6 tems |

variance analysis conditional moderated mediation analysis |

| [28] | (high vs. low) BLN→BP (+) (high vs. low) BLN→SPP (+) (high vs. low) BLN→PT (natural vs. human-made) →BP (+) (high vs. low) BLN →LA→PT →SPP (+) |

Study1 high BLN — 4 tems;low BLN — 4 tems Study2 high vs. low Correlation and BLN — 4 tems Study3 (high vs. low) BLN and PT (natural vs. human-made) — 4 tems Study4 BL and PT naturalness— 4 tems |

one-way ANOVA mediation analysis |

| [62] | CC→ATSB (+) CC→PPS (+) PPS→ATSB (+) CC→ PPS→ATSB (+) TI→CC→PPS TI→CC→ATSB |

Study1-3 TI (7-point Likert scale)— 4 tems PPS (7-point Likert scale)— 3 tems CC (7-point Likert scale)— 2 tems ATSB (seven-point semantic)— 3 tems |

CFA PROCESS |

| [63] | AL→ATTD (+) AL→PNFS→ATTD PNFS→ATTD (+) AL→IPF→ATTD |

Study1-3 ATTD (9-point Likert scale)— 20 tems | ANOVA |

| [64] | Uppercase brand names (UBN) →PC (+)→PP (+) PSV→ LC→PC UBN→conspicuous perceptions (CP) (+)→PP (-) |

Study 1a arget —7tems and attribute stimuli—5 tems Study 1b PP—5 tems; Study 2a (7-point Likert scale) PP—11 tems Study 2b (7-point Likert scale) PP—4 tems Study 3 (nine-point scale) PP—4 tems Study 4 (7-point Likert scale) PP—3 tems |

one-way ANOVA meta-analysis |

| [65] | PL → TL→ ATD and VI PL→ DF→ ATD and VI PL→ PF→ ATD and VI CS→ PF→ ATD and VI |

Study1: (5-point Likert scale) ATD— 4tems; VI— 4tems Study2: (five-point semantic differential scales (PF— 5tems Study2: (7-point Likert scale) AD and VI— 6tems |

MANOVA |

| [66] | BVI→ PS→ BL (+) BVI→ PS→PI (+) BVI→ PC→ BL (+) BVI→ PC→PI (+) TOP→BL, PI |

8 items (7-point semantically differential HED-UT scale) Study 1 consumers’ hedonic and utilitarian attitudes— 4-items Study 2 (7-point Likert scale) PC— 6 items; PS—3 items Study 3 (7-point Likert scale) BL—3 items; PI—1 item |

ANCOVA Mediation analyses |

| [67] | Consumers experiencing higher power respond differently to angular vs. rounded shapes. PCAW play a mediating role between CPS and SP |

(7-point Likert scale) Study 1 general sense of power—8 items Study 2 abjective social status—3 items Study 3 sense of power—3 items Study 4 5 characteristic—3 items |

ANOVA Mediation analyses |

| [68] | CBL→ EP→BA CBL→ PG→BA |

7items (7-point Likert scale) EP — 4 items; BA — 3 items |

two-way ANOVA Mediation analyses |

| [69] | SF→GP SF→GP→GP SF→WP→GP SF→GP→WP→GP |

(7-point Likert scale) GP—1 item |

regression analysis |

| [41] |

LC→ BL LC→LE →BL LC →ATR →BL LC →ATR →LE |

(7-point Likert scale) LC— 3tems; ATR— 4tems; BL— 4 tems; LE (7-point semantic scale)— 5 tems |

ANCOVA PROCESS |

| [70] | LD→ CM LD→ CF LC →CM LC →CF LD combination LC →LM LD combination LC→ LF BL→LM →ATL (+) BL→LF →ATL (+) CF→ LF →ATL CM→ LM→ATL |

28 tems (7-point Likert scale) LM — 6 tems LF — 6 tems CF — 5 tems CF — 5 tems ATL— 6 tems |

CFA MANOVA SEM AMOS. |

| [71] | LIP and LEP positively correlated LIP and MBA positively correlated. LEP and MBA (positively correlated LIP and MPQ positively correlated. LEP and MPQ positively correlated. MBA and MPQ positively correlated |

(7-point Likert scale) LK — 4 tems BA — 4 tems PQ — 2 tems MBA — 7 tems |

Linear Regression analysis |

| [42] | LSR →BA (+) LSR→ BL (+) LSR→ RI (+) BA→BL (+) BA→RI (+) LSR →BA →BL (+) LSR→ BA →RI (+) |

tems (7-point Likert scale) BA — 5 tems BL — 3 tems RI — 3 tems LSR — 13 tems |

Mediation Analysis Analysis of Structural Model |

| [72] | BI→ET→CI BIET→CI →CM |

drawing on over 60 different studies in 19 countries, across 13 categories and including over 1200 individual measurements of brand identity element uniqueness. | RSD HHI |

| [73] | HT→ HT →love → CR HT→CR (+) |

15 items (7-point Likert scale) HT—5 items; CR—7 items; Love—3 items |

two-way ANOVA Mediation analyses |

| [43] | BC →attractive→BF (+) WL →attractive→BF (+) POM →attractive→BF (+) |

9 items (most unappealing [− 5] and most appealing [5] scale) BC—3 items; WL—3 items; POM—3 items |

correlation and factor analysis. (CFA) SEM |

| [74] | BS, BL→BA association and belief →BR→BA BN, BL→AOC BA→BR BA→BA BR→BP |

77 tems (7-point Likert scale) BN—10 tems;BL—23 tems;BA—8 tems BA—13 tems; BR—9 tems; BP—14tems |

EFA CFA |

| [75] | logos → VA (+) graphic (logo) more than text more than VA to the eco-label text→utility and WTP (+) |

6 tems (7-point Likert scale) eco-label—3 tems VA—3 tems |

Econometric analysis |

| [23] | BLR, CF→CRME BLR, CF →BLE→CRME stronger for high fit brands than low fit brands. |

Attitude ad (5-point semantic differential scale— 5 tems BA (7-point semantic) — 3 tems Partnership credibility (7-point scale) — 3 tems BLE (7-point Likert scale)— 5 tems PI (7-point semantic scale) — 3 tems CF (7-point semantic scale)— 3 tems |

MANOVA |

| [25] | BCI→ BA (+) BA →BSI (+) BSI →CBL (+) |

BCI — 20tems CBL (CI, BA, BA: brand attribution, BB: brand benefit; BSI, CBL) — 6tems |

Descriptive analysis EFA factor analysis SEM |

| [76] | BL→ BP (+) BL→ BI (+) BL →BF (+) BF →BI (+) BL→BP→BI (+) BL→BF →BI (+) |

42 tems (7-point semantic scale) (3 brands) BL —11tems BP — 19tems BI — 7tems BF — 5tems |

SEM |

| [77] | UBN→ (BG)→PA (+) LBN←→GB→PI (+) |

Study 1 Participants were randomly assigned to two groups and randomly selected gender. Study2 17 items (nine-point scales) gendered brand personality scale—12 items brand friendliness-authority scale—5 items Study 3 (seven-point scales) attitudes—4 items Study 4 (seven-point scales) Attitudes—3 items Study 5 (seven-point scales) Attitudes—3 items |

logistic regression ANOVA GLM repeated measures analysis |

| [78] | How do clients describe the characteristics of the logo? logo typology→LO logo color→LO |

Study1: The 15 logos are divided into two groups for cluster classification. Study2: 30 tems |

Cluster analysis |

| [79] | BLC→ME(+)→BR(+) MB→LC→ BR |

Study1:6 BL and 4ME (7-point semantic scale) — 1 tem Study2: BR (4-point recognition scale) BA (7-point Likert scale) — 3 tems |

Comparative analysis |

| [80] | OL greater than affect CD. NL OL greater than affect AD. Females OMales CD age NL(+) |

VI— 11ems | MANOVA |

| [2] | CLN →CL (+) CLT→ CL (+) CLD →CL (+) CLC→ CL (+) CL → CI (+) CI →CR (+) CL →ATA (+) ATA→ CI (+) CL→ CF (+) CF →ATA (+) CL→ CR (+) CR →CI (+) |

61 tems (7-point Likert scale) CL — 15tems; CLT — 8tems; CLD — 9tems; CLN — 10tems; CI — 5tems; CR— 8tems; CAD — 10tems |

EFA SEM CFA |

| [32] | BL→LA→BA→BL BL→LA→BM→BL BL→LA→BM→BA→BL |

26 items (7-point Likert scale) BA—3 items; BM—6 items; BF—2 items; BL—5 items. LA—3 items; LF—2 items; LC—2 items; LA—3 items |

ANCOVA tructural equation model Comparative analysis |

| [81] | BN→ FI →FP BN→FC →FP |

14tems (7-point Likert scale) VAS — 3tems; TFEQ — 3tems; BESC— 8tems | ANOVA ANCOVA |

| [82] | PE→ SPK→ CI PE→SPK → VC |

8 tems(5-point Likert scale);BL—3tems;CI—1 tem;PE—6tems; SPK—2tems | |

| [83] | ITL→ PC ITL→ LI →PC ITL→ LC ITL →LC→ LC ITL vs. TL→BA |

Study1: (7-point semantic scale) (3 brands) BA — 3tems Study2: (7-point Likert scale) BA — 2tems Study3: (7-point Likert scale) BA — 5tems |

NOVA |

| Article | Findings Related to BVI | BVI Managerial Implications |

|---|---|---|

| [3] | The proposed framework effectively generates the desired brand personality perception based on the visual identity elements. | Brand design plays a crucial role in shaping brand personality perception, even before consumers can deepen their knowledge about a brand through any other type of engagement with it. |

| [60] | The colour of signage significantly impacts consumers’ perceptions of food healthiness and purchase intentions, while the restaurant name significantly influences these intentions. The significant role of national colour in influencing consumer perception and behaviour within the ethnic restaurant industry. This study reveals two interaction effects of signage colour and restaurant name on consumers’ perceptions of food healthiness and dining intentions. |

Restaurants can manipulate outdoor signage to enhance consumers’ perceptions of food healthiness, tastiness, and purchase intentions. Ethnic restaurants are advised to incorporate the national symbol into their names to boost consumer interest in dining. Restaurants can manipulate outdoor signage to enhance consumers’ perceptions of food healthiness and dining intentions. |

| [61] | The logo shape significantly influences consumers’ perception of a product’s suitability based on its perceived brand premiumness. an angular (vs. circular) brand logo increases the perceived premiumness of a brand. |

An angular brand logo can enhance consumers’ perception of brand status by extending their psychological distance from the masses. |

| [13] | The congruity effect between logo typeface and destination stereotype was influenced by tourists’ cognitive needs. A potential tourist’s high cognitive needs can mitigate the congruity effect, thereby moderating their cognitive needs. |

DMOs should acknowledge the role of the destination logo. DMOs can create logos in machine- and handwritten typefaces for tourists with competence or warmth stereotypes, considering cultural differences in destination stereotypes. |

| [28] | Natural and representative logos are more memorable than those with abstract design elements. The naturalness of brand logos significantly influences consumers’ perceptions of brand personality, as they naturally create brand-related images through logo perception and association. |

When logo authenticity perception is crucial to consumers’ brand expectations, it is advisable to prioritise high natural logos. Brand managers should choose logos with naturalness levels according to product type. well-established firms to occasionally modify their logos. |

| [62] | The team-coloured sponsor logo on the jersey positively impacted perceived sponsor support and attitude towards the sponsor. Visual congruity, like other types of congruity, can be advantageous for favourable sponsorship responses, indicating that congruity can be intentionally created. |

A jersey sponsor with low brand awareness can benefit from creating brand-colour congruity. Low-profile brands, like local ones, should focus on brand-colour congruity to receive more positive feedback from fans. A team jersey is a highly valued iconic symbol among sports enthusiasts. |

| [63] | Consumers’ cognitive tendencies align with processing methods when a logo in the form of ILTR is viewed, leading to a more positive attitude towards the tourist destination. The horizontal alignment of images and text in a tourism logo significantly influences consumers’ attitudes towards the destination, largely due to the fluency of information processing. |

Tourist attractions should design logos in a specific order to align with consumer reading order and information-processing mode. Tourist attractions can influence consumers’ information processing fluency by altering the visual effects and presentation forms of tourism logos. |

| [64] | Consumers tend to prefer more capitalised brands for status motivations rather than saving money. Letter cases can strengthen consumers’ purchase intentions and brand choices through premiumness inferences. |

Our findings provide practical instructions for brand designers and marketers in brand letter case selection. Retailers should also consider product type when selecting brand letter cases. |

| [65] | The physimorphic logos possesses elements that serve as cues, influencing the formation of more favourable attitudes and visit intentions. Higher processing fluency is linked to a positive attitude towards advertisements. The study found that physimorphic logos had a higher intention to visit compared to typographic logos, moderating influenced by cognitive styles (visualizers vs. verbalizers). |

For the destination marketer, it would be a safer bet to market a destination using a physimorphic logo against a typographic/regular logo. A marketer may be able to achieve a higher impact on the prospective tourist with less exposure while using a physimorphic logo. The marketer may design the logo in such a manner that the logo has some textual information to cater to both visualizers and verbalizers. |

| [66] | BVI leads to positive brand outcomes, such as purchase intentions and brand likability. Biophilic appeals increase brands’ perceived authenticity. Product type (hedonic vs. utilitarian) does not have a significant impact on BVI’s influence on perceived sustainability and credibility. The type of product (hedonic vs. utilitarian) does not significantly influence the perceived sustainability and credibility of BVI. |

Managers need to realise that simply following sustainable practices may not be adequate; BVI is expected to lead to long-lasting attitudinal shifts in consumer behaviour, influenced by perceived sustainability and credibility. |

| [67] | Consumers in different power states respond differently to angular and rounded shapes. Consumers with higher power-value competence tend to prefer angular shapes over rounded ones due to lower power value competence over warmth. |

Marketers can segment consumers based on their sense of power, shifting their current state of power based on their product and brand characteristics. The angular shape reflects more on competence, while rounded shape reflects more on warmth. |

| [68] | The cute logo as having higher levels of cuteness than the non-cute logo Participants in the hope condition reported a more favourable attitude towards a brand with a cute appearance, but not in the happiness condition. |

The importance of brands and companies communicating their potential to grow and develop to their consumers. They should pair such cute appeals with the emotion of hope in which they can elicit using advertising messages. |

| [69] | Aounded logos are considered warmer, more feminine, and more appropriate for green brands than angular logos. The shape of brand logos indirectly influences consumers’ green perception through gender perception, but through multiple mediation effects of gender perception and warm perception. Aounded brand logos are more appropriate for green brands. |

Green companies can prioritise rounded brand logos when selecting a logo shape. The strategy of using shape to convey indirect meanings can be widely used for international brands. Marketers should select distinctive shapes for brand logos to showcase greenness to different types of companies, consumers, and products. For low-involvement green products, using brand logos to convey greenness can be especially effective. |

| [41] |

Respondents’ attitudes towards rebranding significantly influenced the relationship between logo change and brand loyalty. Logo change significantly influenced logo evaluation, while logo evaluation was a significant predictor of brand loyalty. Attitude towards rebranding would mediate the relationship between logo change and logo evaluation, as well as the relationship between logo change and brand loyalty. Colour modification significantly influenced the brand loyalty of the fans with a negative rebranding attitude. |

Sport marketers need to comprehend the distinct characteristics and effects of both evolutionary and revolutionary rebranding. Revolutionary rebranding is a strategy that involves a complete logo redesign, often being more suitable for brands with low brand equity or undergoing management or personnel changes. Sport organisations should involve their fans in the rebranding process, or at least seek their feedback. |

| [70] | The colour plays a significant role in shaping brand gender perceptions, with dark blue logos indicating masculinity and light pink logos indicating femininity, emphasising the brand’s visual identity. Logos with a clear brand gender positioning trigger a more favourable affective response. The use of cultural logo designs enhances masculinity perceptions, and the use of organic logo designs effectively shapes femininity perceptions. |

Characters, logos, and logotypes offer the best chance to create distinctive associations, while colours are more likely to be shared with competitors. To achieve their desired brand gender positioning, brands should design their logos using appropriate gender cues. |

| [71] | The Ministry’s statements during the launch of the new logo confirmed its effectiveness in fulfilling its function. A logo can have a positive influence on brand awareness and the public’s perception of its quality. |

This research provides a basis from a managerial perspective for practitioners in using visual communication to manage how their message can be viewed. Government institutions should utilise branding efforts to enhance their internal identity, promote long-term social goals, and enhance their brand image, rather than for promotion purposes. |

| [42] | The brand’s attitude had a strong, optimistic impact on brand loyalty. The significant positive impact of the brand attitude, as opposed to our hypothesis, mediates between logo shape redesign and repurchase intention. |

The logo redesign has been positively reacted to by weakly loyal customers, requiring a more complex strategy to appeal to both classes. Marketers should prioritise perceived quality, emotions, moods, and emotions, while also focusing on the value proposition of any product. |

| [72] | The logotype, which includes typeface, colour, and pictogram, can enhance a brand’s identity and perceptual fluency. Based on the HHI* values, character, logo, and logotype have the highest average concentration of uniqueness. Colour, with its low uniqueness concentration and high within-type variation, is the most challenging element to obtain on average. |

Characters, logos and logotypes provide the best opportunity to develop unique associations, whilst colours are significantly more likely to be shared with competitors. The HHI offers a practical measure to assess the uniqueness potential of brand identity elements, which could guide brand managers in their selection. |

| [73] | Handwritten typeface evokes human associations and perceptions of love and passion in menu dishes, boosting consumer responses to the restaurant brand. The handwritten typeface effect extends to social media engagement based on the notion of “social reciprocity.” |

The study offers crucial managerial insights on marketing healthy restaurant brands effectively through visual design and menu psychology. Handwritten typefaces can provide brands with similar advantages in marketing communications. |

| [43] | People preferred logos that use bright colours, such as yellow, pink, or blue. The logos were preferred to feature living creatures like birds, giraffes, or elephants. People preferred logos that suggested dynamic movement. The three factors greatly affect the favorability of logos. |

The study’s findings offer crucial insights for managers in designing, selecting, or modifying logos. |

| [74] | Consumers’ perceptions of a brand’s favourable signature significantly influence their brand awareness, increasing the recognizability and familiarity of products and services. The brand name’s construct has the most significant influence on consumers’ perceptions, followed by design, typeface, and colour. A comprehensive understanding of the concept of the ‘favourable brand signature’ and its consequences |

This study may provide actionable guidelines for international tourism practitioners. The emotional aspect of a brand signature is crucial for corporate identity, rather than solely focusing on fashion and modernity. Consumers’ attitudes towards brands have a positive impact on their perceptions of brand reputation. |

| [75] | Logos capture more visual attention than text eco-labels. Additional visual attention to the logos increases participants’ bids, while visual attention to the text decreases their bids. |

Investing in a recognisable logo that attracts visual attention is critical to improving consumer valuation of the products. Firms can benefit from utilising eco-labels that are already well-established and positively perceived in other product categories. The importance of branding and promoting eco-labels lies in enhancing consumer and firm awareness of these eco-labels. |

| [23] | Previous research indicates that brands with high conceptual congruence tend to have enhanced attitudes. The firm’s reputation may be damaged if the partnership is perceived as being as extremely incongruent; establishing perceptual congruence is not successful. |

Brand managers can enhance their brand and cause attitudes by enhancing conceptual and perceptual alignment with the cause. Marketers can exploit negative perceptions of brands that lack conceptual coherence. |

| [25] | Colour identity significantly impacts brand attitude, surpassing brand attribution or benefit, as it significantly influences the formation of brand attitudes. Brand associations may enhance brand self-identification, be influenced by brand attribution, benefit, and attitude, and positively impact corporate brand loyalty. Progressiveness, oriental beauty, and fashionableness, which are sub-factors of airline colour identity, |

A company’s brand trust can be achieved through a consistent presentation of its colour and image. A company’s brand trust can be achieved through a consistent presentation of its colour and image. Corporate brand colour identity, including logos, trademarks, symbols, and products, significantly influences brand differentiation and competitive advantage. Brand managers should focus on creating authentic and ideal consumer identities, including programmes that maintain brand loyalty. |

| [76] | The study emphasises the significance of a brand logo in enhancing its brand image, with brand personality dimensions and brand familiarity playing a significant role. We confirm and extend these studies by exhibiting that brand logos positively influence brand personality dimensions (except competence). This study shows the mediating role of brand personality dimensions and brand familiarity in the relationship between brand logo and brand image. |

Managers can enhance brand image by incorporating logos, personality dimensions, and brand familiarity to create a strong brand identity. This study provides managerial insights for graphic designers and design makers to understand consumer perceptions of a brand logo. Managers are responsible for designing promotional strategies and brand communication to ensure the desired brand personality. Managers should make efforts to improve their familiarity with the brand. |

| [77] | Lowercase brand names are associated with feminine traits, while uppercase brand names are associated with masculine traits. The greater congruity between brand case and the gender of consumption benefits increases product evaluations and purchase intentions. |

This study enhances marketing practice by demonstrating the impact of brand cases on consumer attitudes and intentions. The study enhances the comprehension of brand gender and brand personality. |

| [78] | The study confirms the significant impact of logo colour on brand perception. Customers value secondary logo design characteristics such as outline, shape, letter composition, and abstract versus descriptive logos, in addition to colour and design elements. |

We propose a straightforward method for entrepreneurs, managers, and logo designers to enhance the appeal of their new logos by incorporating both an icon and the brand name. |

| [79] | Well-established brand logos are recognised faster than less-established brand logos when logo design is not considered. Well-established logos: here, complex logos were faster recognised than simple logos. Exposure led to an increase in brand recognition for complex brand logos but not for simple brand logos. Complex brand logos are recognised faster than simple brand logos. |

Brand recognition through brand logos is a crucial component of market success. Graphic designers simplify brand logos by reducing the number of colours, lines, and shapes. For a company to introduce a new product or brand through a sustainable advertising campaign, complex brand logos are recommended. |

| [80] | The study found no significant differences between male and female respondents in any dimensions, except for the known organic logos. The study suggests a potential positive correlation between age and a person’s perception of logos, especially in relation to cultural designs. Age may positively correlate with affect towards various logo categories, with individuals exhibiting greater affect towards various logo designs as they age. |

Managers are advised to opt for logos with natural designs for maximum positive impact. The chosen logo design can significantly replace brand awareness, a crucial source of brand equity, at no cost to the firm. |

| [2] | The corporate logo serves as a powerful marketing tool, fostering strong perception-based relationships with consumers across various demographics. There is no mediation or indirect effect between the corporate logo and corporate image. The construct of the corporate name has the greatest influence, followed by design and then typeface due to this fact. |

The company prioritises its corporate logo in its efforts to establish a positive corporate image and reputation. The study aims to comprehend the intricate connection between a favourable corporate logo and its antecedents, including corporate name, typeface, and design, from the consumer’s perspective. Managers strive to create favourable and reliable communication of their corporate identity to the market. |

| [32] | Higher brand modernity when respondents evaluate the new logo rather than the old version. Respondents show a higher attitude towards the new logo compared to the old version. The attitude towards a logo is significantly influenced by its attractiveness and familiarity. Logo attitude positively influences brand modernity and brand attitude. |

Logo familiarity and attractiveness may be of utmost importance for brand managers. Companies can offer a price premium to their loyal customers, thereby enhancing their advertising efficiency. Managers should focus on the perceived modernity of their brand. |

| [81] | Brand names influence flavour perception and predict food intake. Participants rated the food with the healthful label as having a better taste and flavour. |

/ |

| [82] | People’s evaluation of the country’s logos significantly impacts their image of the country, even after accounting for pre-existing knowledge and attitudes. The research aims to explore how people’s perceptions of a country’s image influence their intention to visit the country, considering pre-existing knowledge and attitudes. |

The research aims to explore how people’s perceptions of a country’s image influence their intention to visit the country, considering pre-existing knowledge and attitudes. |

| [83] | Logo interest and clarity mediate the impact of incomplete typeface logos on perceived firm innovativeness and trustworthiness, respectively. | Managers should avoid incomplete typeface logos to create a trustworthy firm perception. Managers of firms with incomplete typeface logos may intentionally use advertising copy and promotional materials to encourage a pro-motion focus in their consumers. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).