1. Introduction

Oral features of CCD include delayed exfoliation of primary teeth, multiple impacted permanent and supernumerary teeth [

3] combined with severe malocclusion as inverted incisor positions, crossbites, and crowding of teeth [

8].

The permanent first and second molars are rarely affected, but spontaneous eruption is usually delayed. Disturbances of normal tooth eruption can manifest as tooth ankylosis (10,15). Fusion of bone and tooth root leads to a vertical stagnation of tooth eruption resulting in an infraposition or impaction of the respective tooth. Usually, the apical third of the root is affected in CCD patients. The treatment of patients with CCD requires exposition mobilization and orthodontic traction of the ankylotic tooth. [

1]

Mild cases are frequently underdiagnosed. Accurate and early determination of the diagnosis [

4] and correct timing of surgical interventions is crucial [

2,

6] Diagnosis is based on clinical and radiographic findings [

8,

10] and his condition and by the triad of delayed closure of cranial sutures, hypoplastic or aplastic clavicles and dental anomalies [

8,

20] The panoramic x-ray examination is very useful, but when there a lot of supernumerary teeth present in the mouth, Cone Beam Computed Tomography examination helps the most to set the proper diagnosis [

8,

10,

11].

Our CCD patient was an 8 years 5 months old boy, and he had been multidisciplinary treated for more than ten years, in three departments at the same time. The Department of Pediatric Dentistry supervised oral hygiene and carried out any restoration of the teeth if needed. The Surgical Department performed surgical procedures both in local and general anesthesia. The Orthodontic Department was responsible for the timing and correct ordering of individual interventions and orthodontic treatment. The key to accurately timing of individual steps iwas dental age. For this purpose we used the Demirjan method. The aim of the treatment was to correctly time the removal the supernumerary teeth that interfered with spontaneous eruption of permanent successors, and to include as many of his own permanent teeth as possible in the arch. The patient is 19 years and 2 months old now. No implant or bridge had to be planned, the extraction of two first premolars in the upper dental arch was performed due to upper frontal crowding. The patient underwent 3 surgical interventions under general anesthesia and 2 under local anesthesia. It was necessary to expose and load 5 teeth in the upper and 2 teeth in the lower dental arch. The number of extracted supernumerary teeth was 4 in the lower dental arch and 5 in the upper. One surgical procedure remains to complete the case, under local anesthesia to expose and mobilize the 37 which unfortunately remained impacted.

2.1. Case Report

In April 2013 an 8 years 5 month old boy was referred to the Department of Dentistry, Charles University, Faculty of Medicine and University in Hradec Králové. The chief complaint was despite the age - full deciduous dentition, no permanent teeth emerged into the mouth.

His mother was 30, father 35, he was one of 3 children, He was the oldest of three children and two sisters had no signs of similar affection. The father was affected, he had diagnosed with CCD in early childhood. The mother was unaffected.

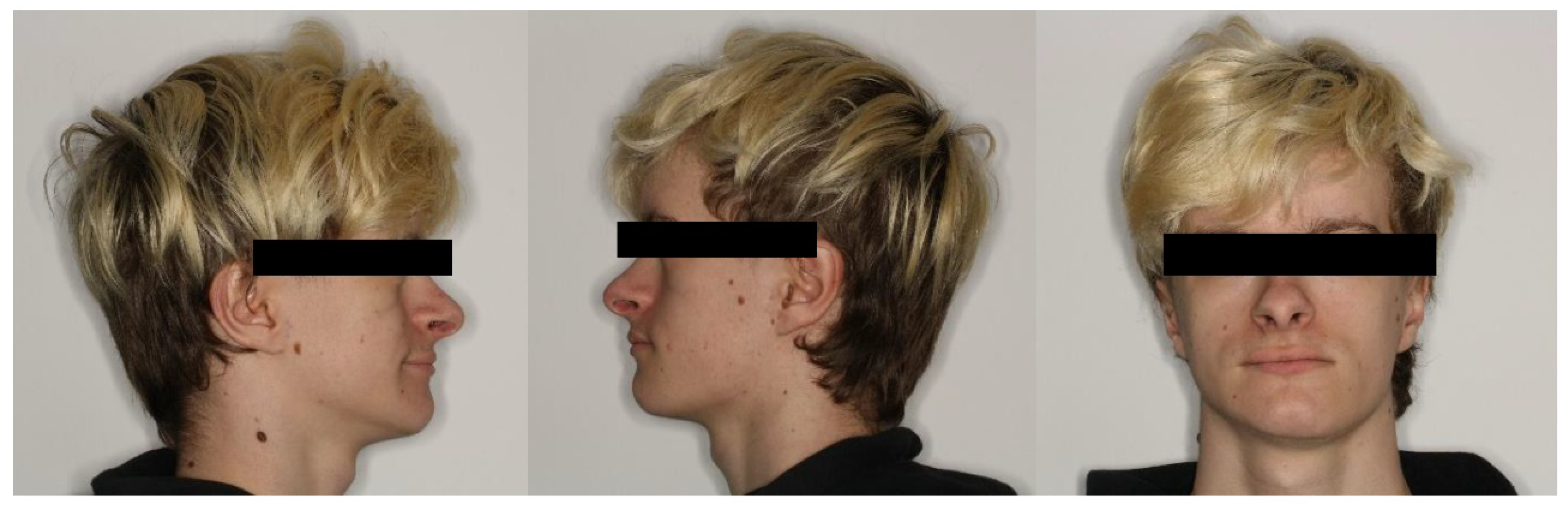

The extraoral clinical examination revealed the reduced height of the lower third of the face and underdevelopment of the midface. There was a clinical pseudoprogenia and depressed nasal bridge present. The shape of the zygomatic arch was within normal ranges. The patient has a moderately short stature and a history of slow growth. Cognitive development was entirely within normal limits.

The intraoral clinical findings revealed no eruptions of permanent successors, carious deciduous molars, and poor oral hygiene level. No permanent first molars were present in the oral cavity. The mother reported delayed eruption of deciduous teeth, which first emerged later than at the age of 1 year. Full deciduous dentition was affected with several carious lesions on deciduous molars 55, 75, and 84. Teeth No 54, 65, and 74 were broken down by deep carious affections. The patient was referred for panoramic radiography (orthopantomography – OPG) and Cone Beam Computed Tomography (CBCT) examinations.

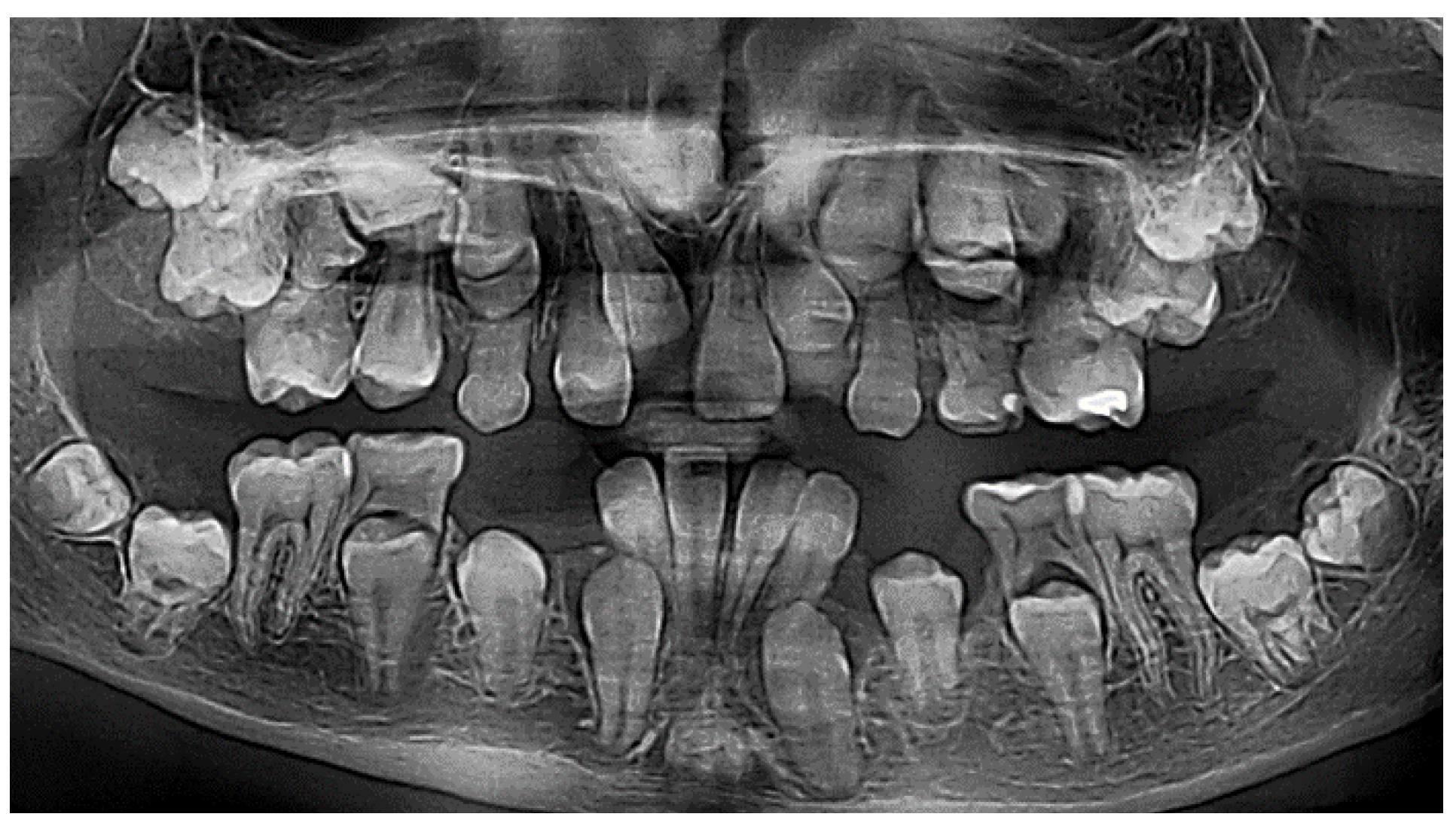

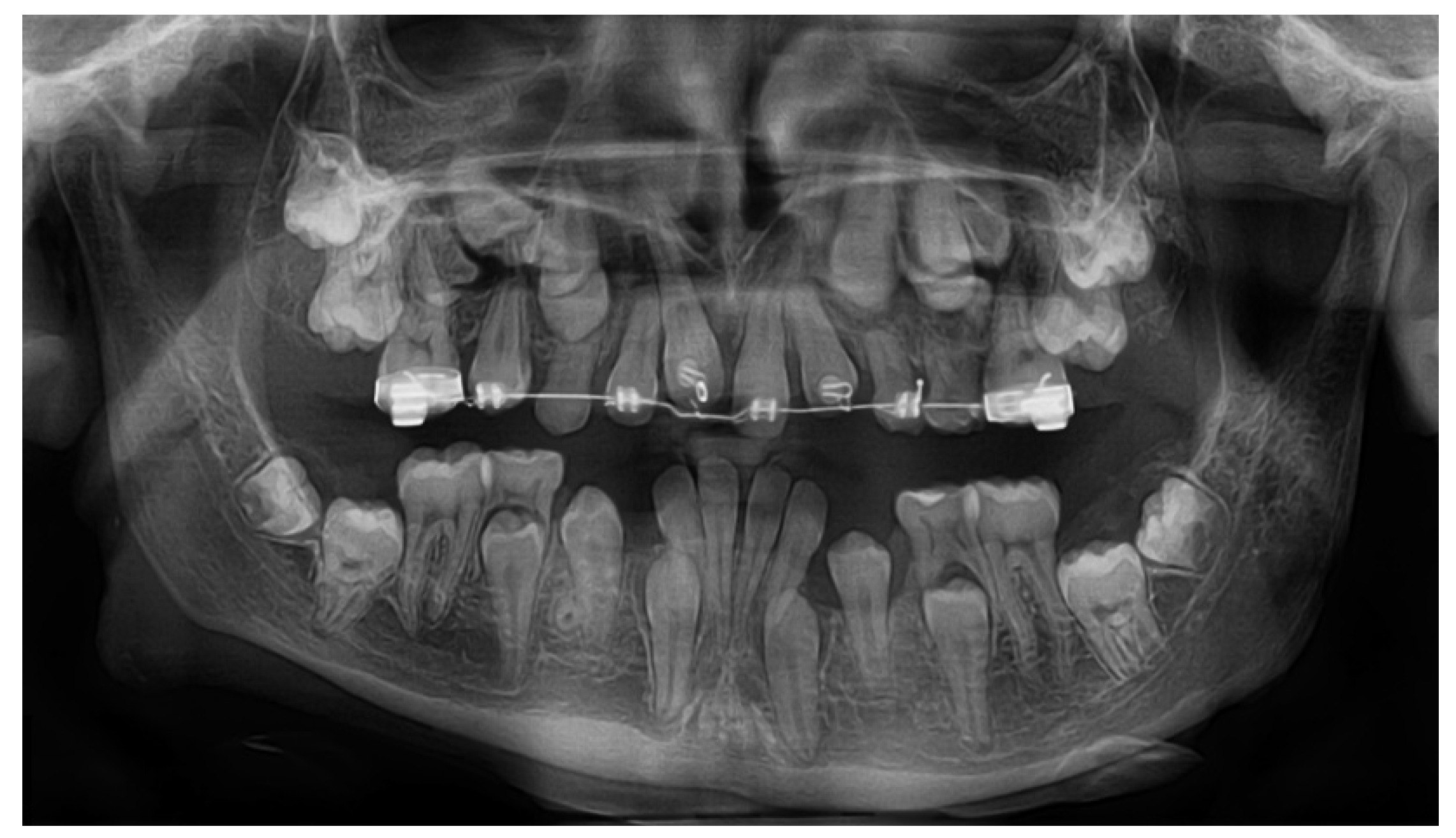

On the panoramic radiographic image (OPG) taken in April 2013 (

Figure 1.) there was a finding of over-retained deciduous teeth with unresorped roots. The dental age was estimated according to the Demirjan method, 4,6 years in the upper dental arch and 6,9 in the lower. Three supernumerary teeth were present in the upper jaw, and two in the lower, displacing the developing permanent teeth and obstructing their eruption. All regular permanent teeth buds were in place, some of them were retarded in eruption also because of a lessened eruptive potential. There was a serious (approximately 3 years) delay in the root development of the permanent teeth. The dental age was estimated according to the developmental stages of the roots of permanent teeth and resorption stages of deciduous predecessors – the Demirjan method [

19,

22].

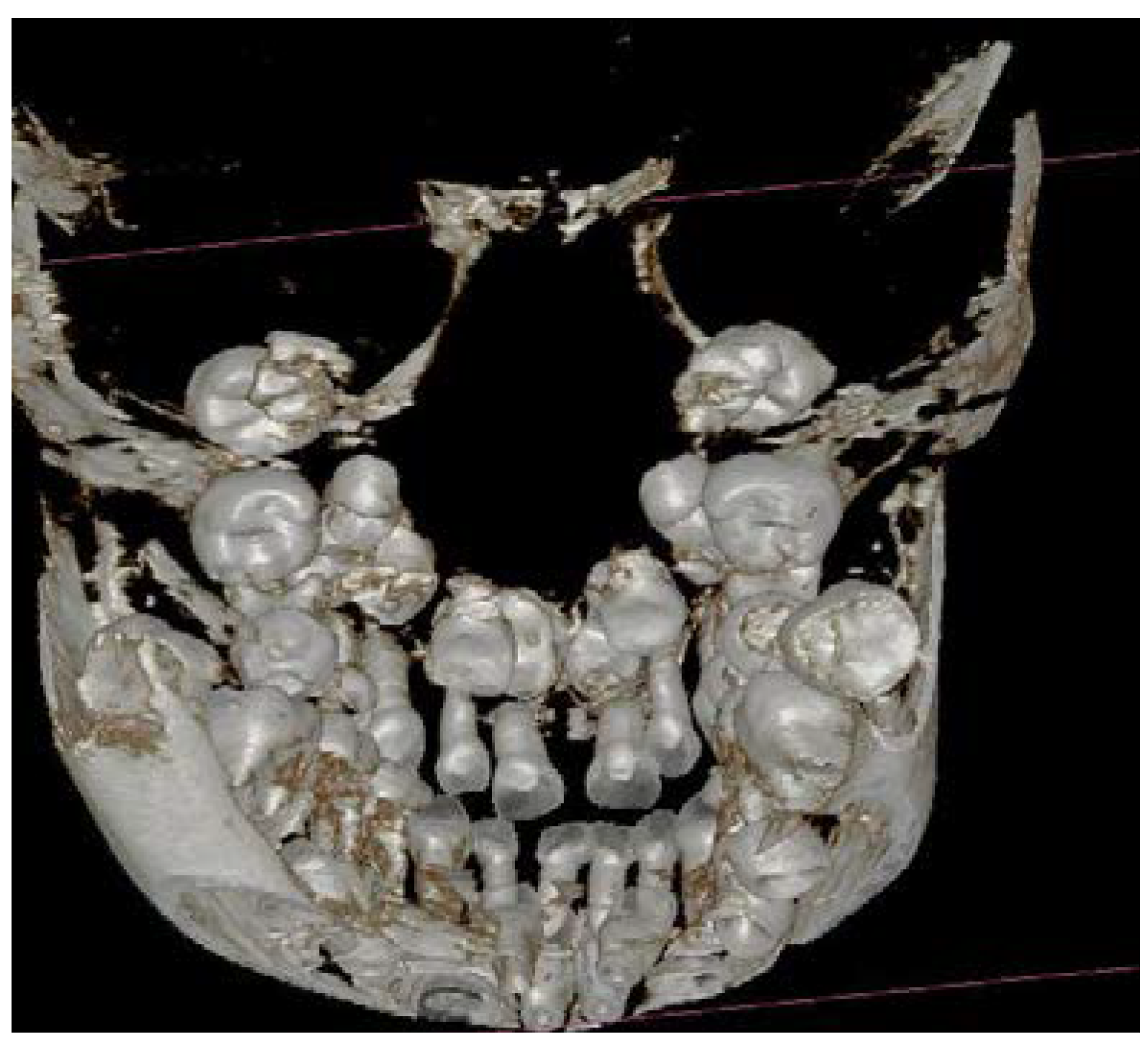

The three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction of the CBCT x-ray, taken in May 2013 revealed three more supernumerary empty tooth crypts in the upper jaw and proved the two supernumerary teeth in the lower. The patient had had 8 supernumerary teeth at that time. (Figure 1.,6.,7.)

A diagnosis of CCD of the patient was proposed due to family history, based on the bilateral hypoplasia of the clavicles, the presence of several supernumerary teeth in the jaws, delayed root maturation, and eruption of permanent teeth. The x-ray examination (OPG and (CBCT) confirmed the status of the jaws and skull. The craniofacial findings included delayed closure of cranial fontanels and sutures.

There was an agreement on an initial surgical intervention under general anesthesia. Informed consent for pedostomatologic, surgical, and orthodontic interventions was signed by the mother of the patient.

2.2. Procedure

In May 2013 the patient was admitted to the Maxillofacial Surgical Department of the Clinic of Stomatology, Teaching Hospital of Charles University in Hradec Králové. During the first phase, the child was placed under pedostomatologic follow-up consisting of professional cleaning and behavior management.

The surgical treatment plan followed the Toronto-Melbourne strategy. This method advocates a series of surgical procedures, initially involving the removal of the deciduous teeth under general anesthesia, with its timing dependent on the appropriate root development of the permanent successors. This method was selected for the young age of the patient and to facilitate the spontaneous eruption of impacted permanent teeth. Due to the initial oral hygiene level of the patient, it was recommended to extend the time without active orthodontic appliances on teeth.

Two surgical interventions in general anesthesia were planned in the upper jaw, provided that no more supernumerary teeth develop from empty, non-mineralized supernumerary dental crypts, which are usually difficult to localize on early CBCT scans. One surgical intervention under general anesthesia was planned in the lower arch to extract the two supernumerary teeth in the premolar area. (

Figure 1)

The first intervention was to extract all carious deciduous teeth and those hindering the spontaneous eruption of permanent successors with root developmental stages corresponding with the actual dental age.

2.2.1. Surgical Intervention 1 (General Anesthesia)

In June 2013, the patient was 8 years 7 months old, under general anesthesia (GA), and in cooperation with a pediatric dentist 4 deciduous (51,61,62 and 65) and 3 supernumerary teeth were extracted from the upper dental arch and one tooth (74) from the lower. The deciduous molars were extracted due to deep carious lesions, which did not allow proper restoration. No permanent teeth at this early phase were exposed – extractions were to encourage spontaneous eruptions of first molars and permanent incisors. (

Figure 2.)

2.2.2. Pediatric Dentistry Intervention

During the next approximately 3 years period the patient´s teeth eruption sequence was observed, and the patient was examined once in a half year. They followed the 6-month pediatric dental prophylaxis recall In the following dental visits the patient was encouraged and instructed to improve oral hygiene level and resin-modified glass ionomer restorations were made on teeth 55, 75, and 84.

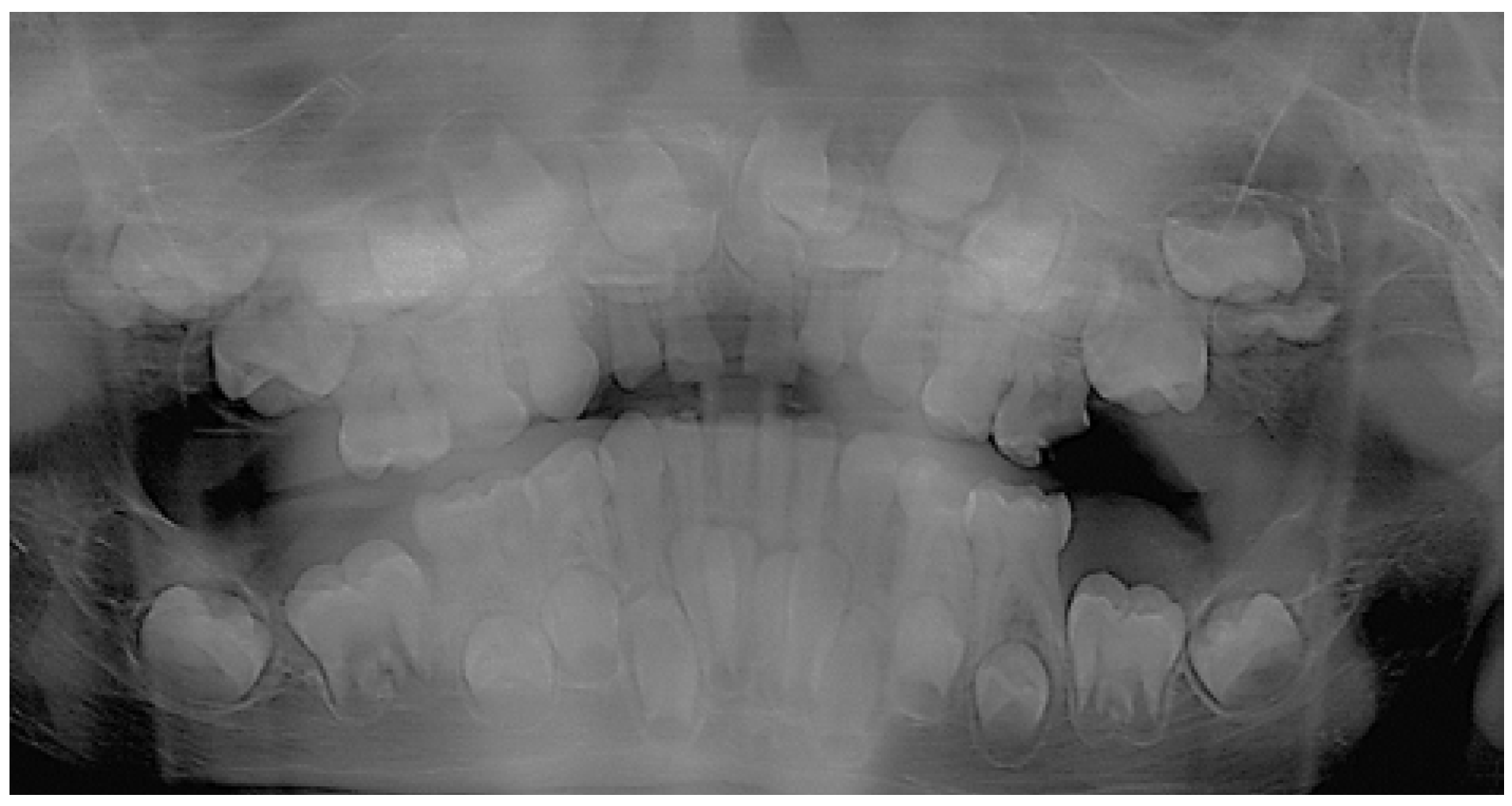

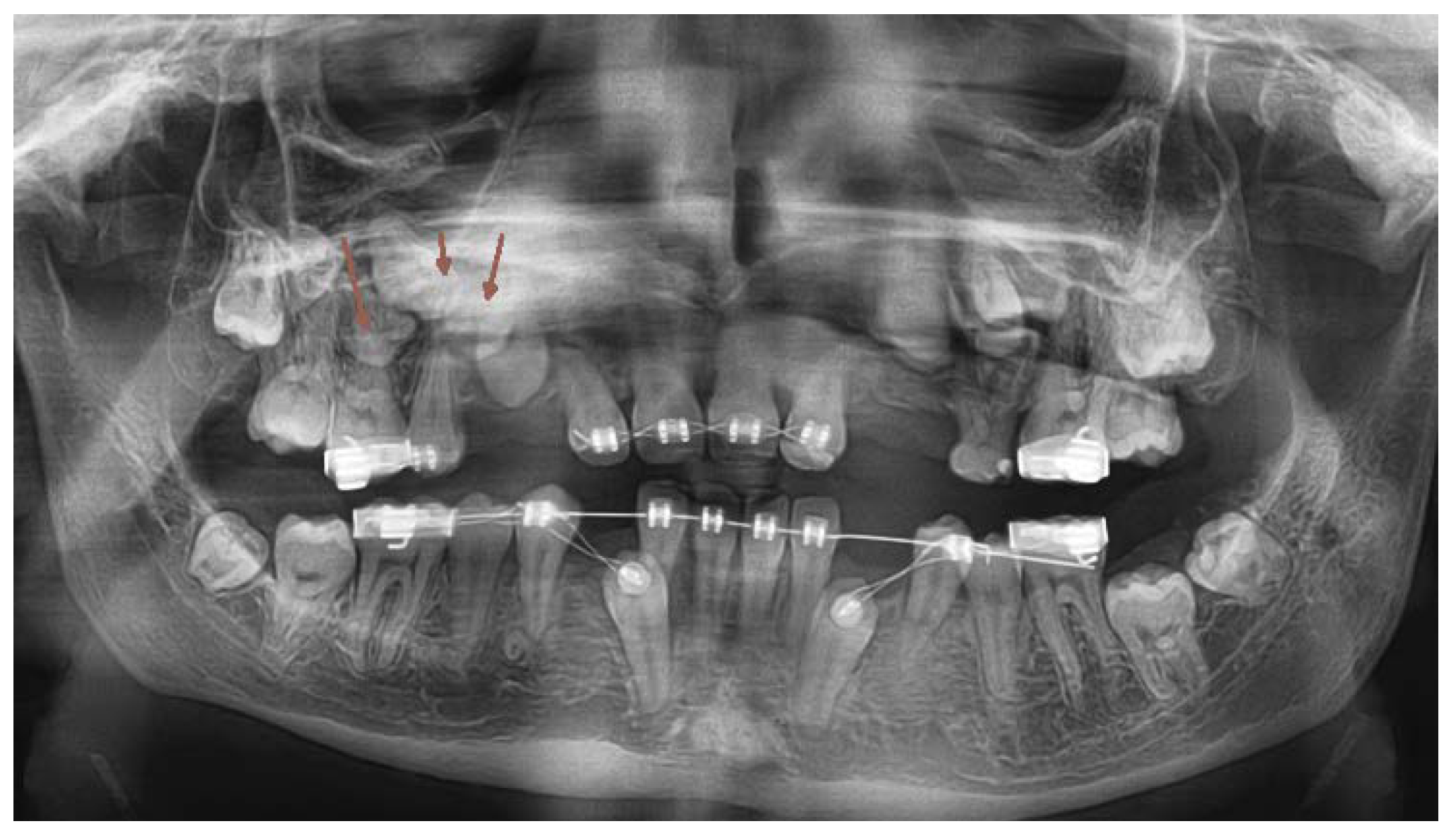

The first panoramic x-ray (OPG) after the surgery was taken in October 2014. (

Figure 3). The dental age (DA) was 7 years in the upper and 7,7 in the lower dental arch. The patient´s chronologic age (CA) was 9 years 10 months. This revealed spontaneous eruption of both upper and lower first molars. The subsequent OPG was taken in November 2015, (

Figure 4) (DA 7,3 and 8 years, the CA 10 y 11 mths) spontaneous eruptions of 21 and 12 happened. All four lower permanent incisors erupted as well.

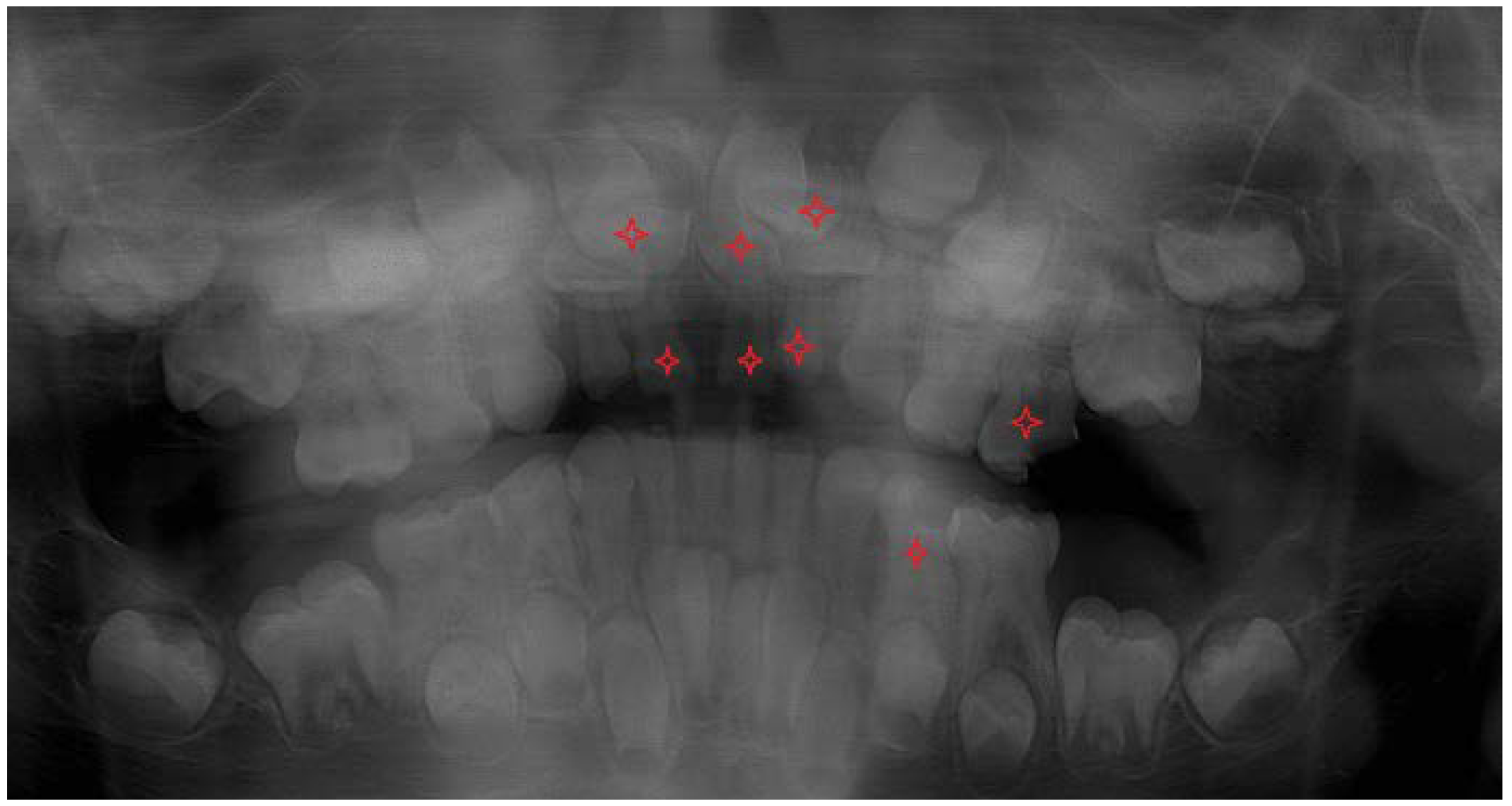

The next two OPG x-rays were taken after 11 months. On the latter (2017) (

Figure 5) it became clear, that 22 and 11 were inhibited in eruption. ( DA 9,1 and 9,3, CA 12 y 11 mths) The patient was referred to the second CBCT scan image reproduction to make clear the underlying surgical situation. (Figure8). The CBCT scan revealed the position of supernumerary teeth also in the lower dental arch. (

Figure 8.,9.)

Figure 5.

The follow-up OPG x-ray – taken in 2017.

Figure 5.

The follow-up OPG x-ray – taken in 2017.

Figure 6.

Seven supernumerary teeth in the upper arch before the 1st surgical intervention in 2013. 3D reconstruction.

Figure 6.

Seven supernumerary teeth in the upper arch before the 1st surgical intervention in 2013. 3D reconstruction.

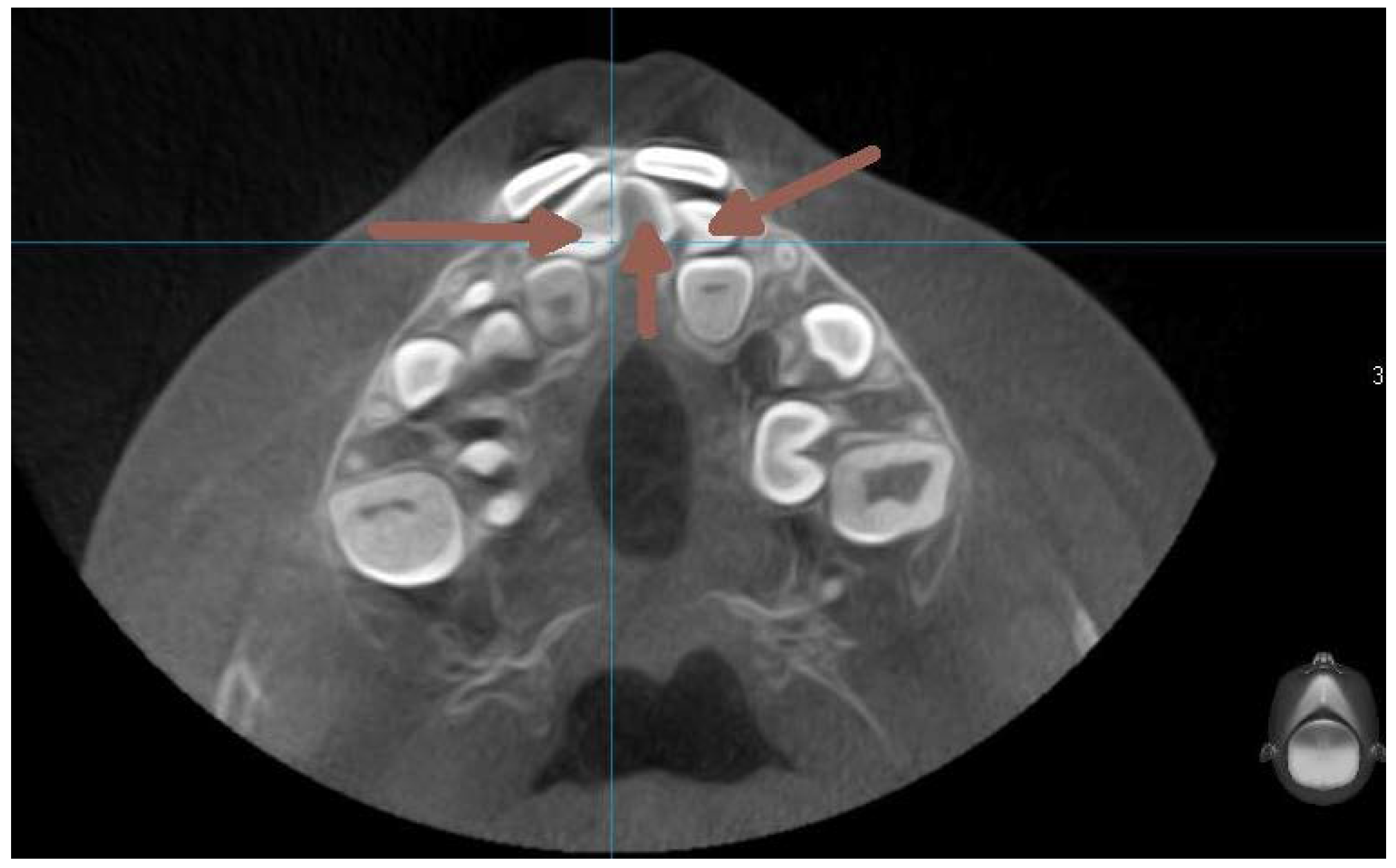

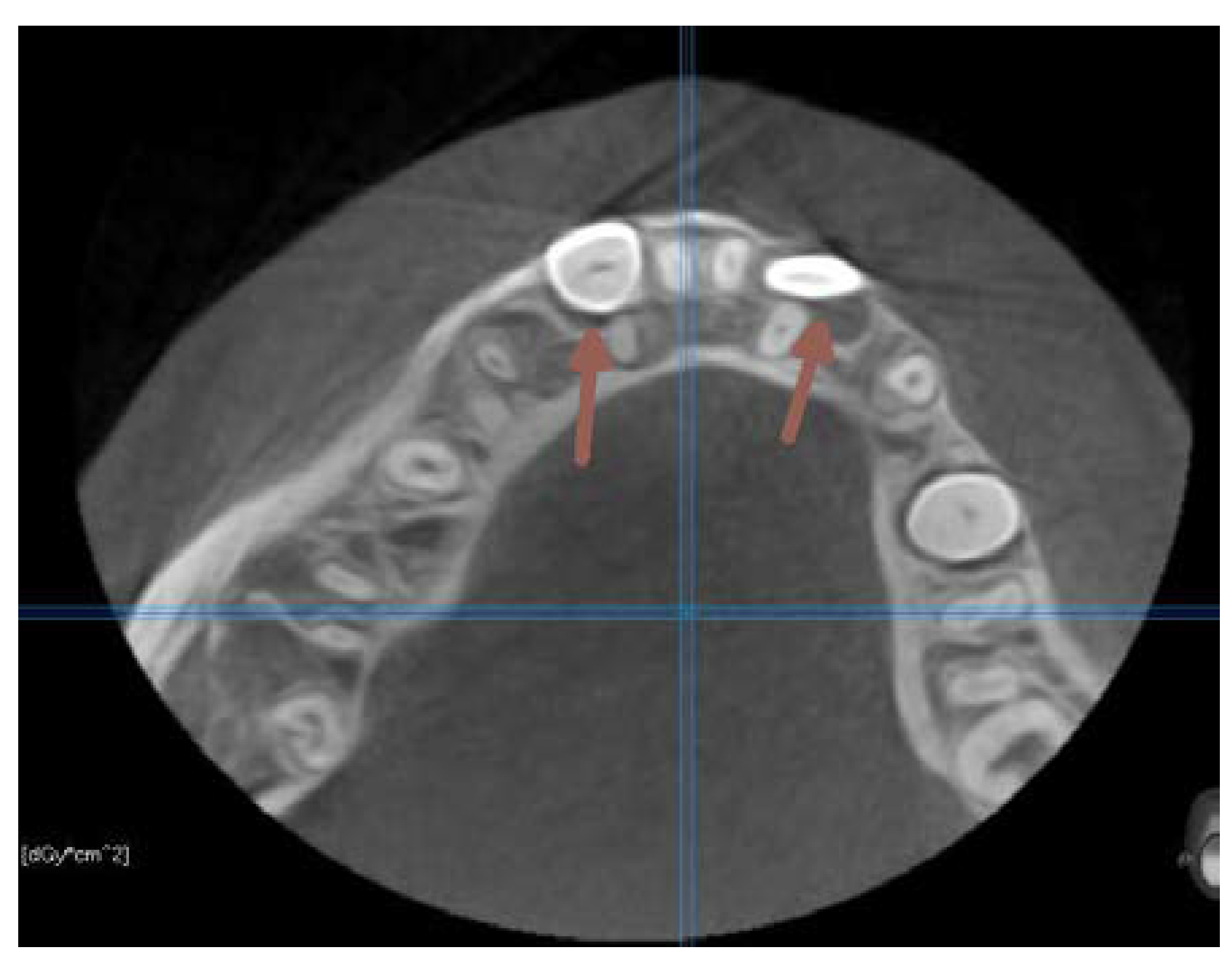

Figure 7.

CBCT transverse section of the maxilla on the level of the upper incisors. (2013) Supernumerary teeth are pointed by arrow.

Figure 7.

CBCT transverse section of the maxilla on the level of the upper incisors. (2013) Supernumerary teeth are pointed by arrow.

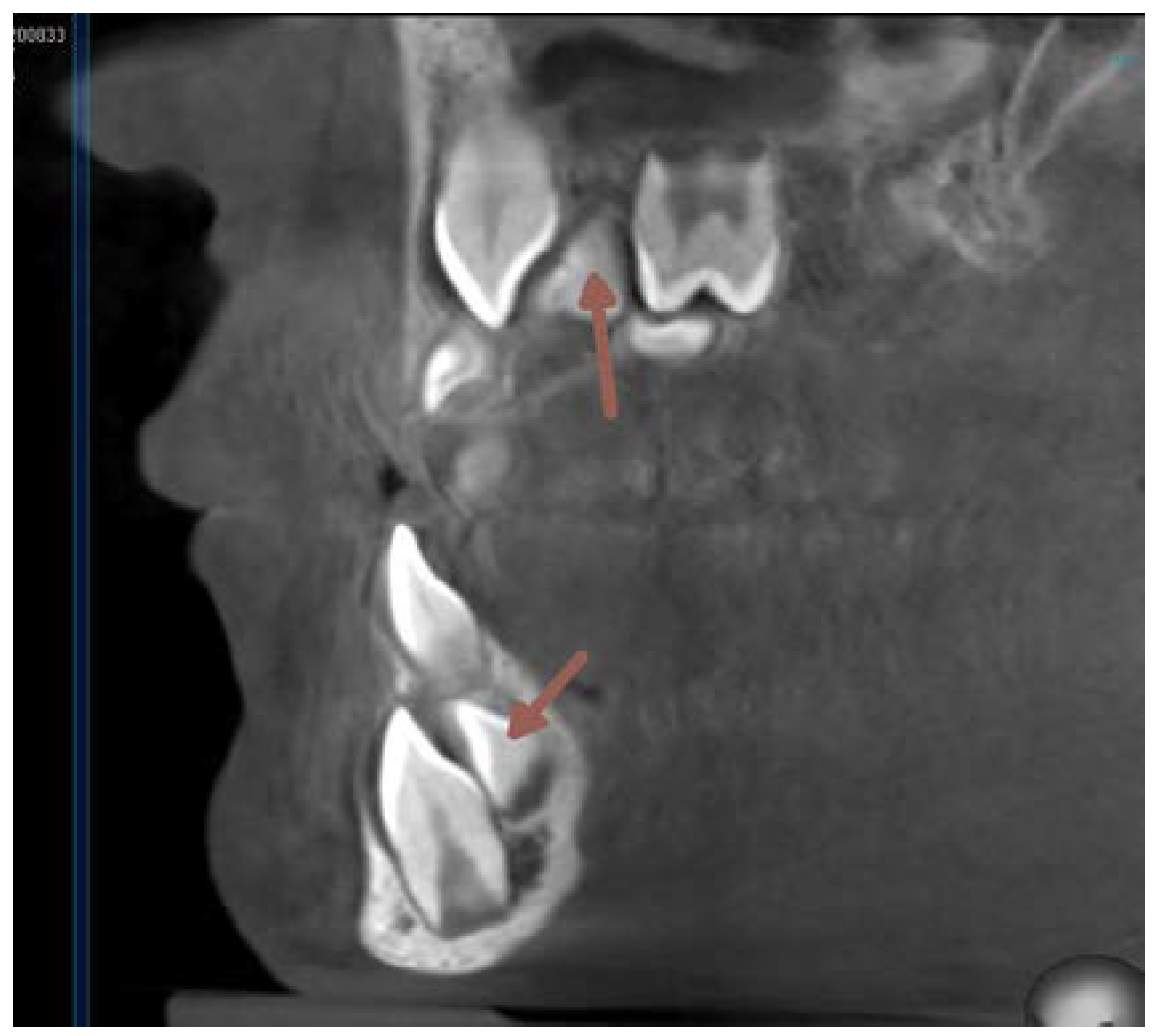

Figure 8.

CBCT vertical section perpendicular to the alveolar ridge on the level of the incisors. (2017).

Figure 8.

CBCT vertical section perpendicular to the alveolar ridge on the level of the incisors. (2017).

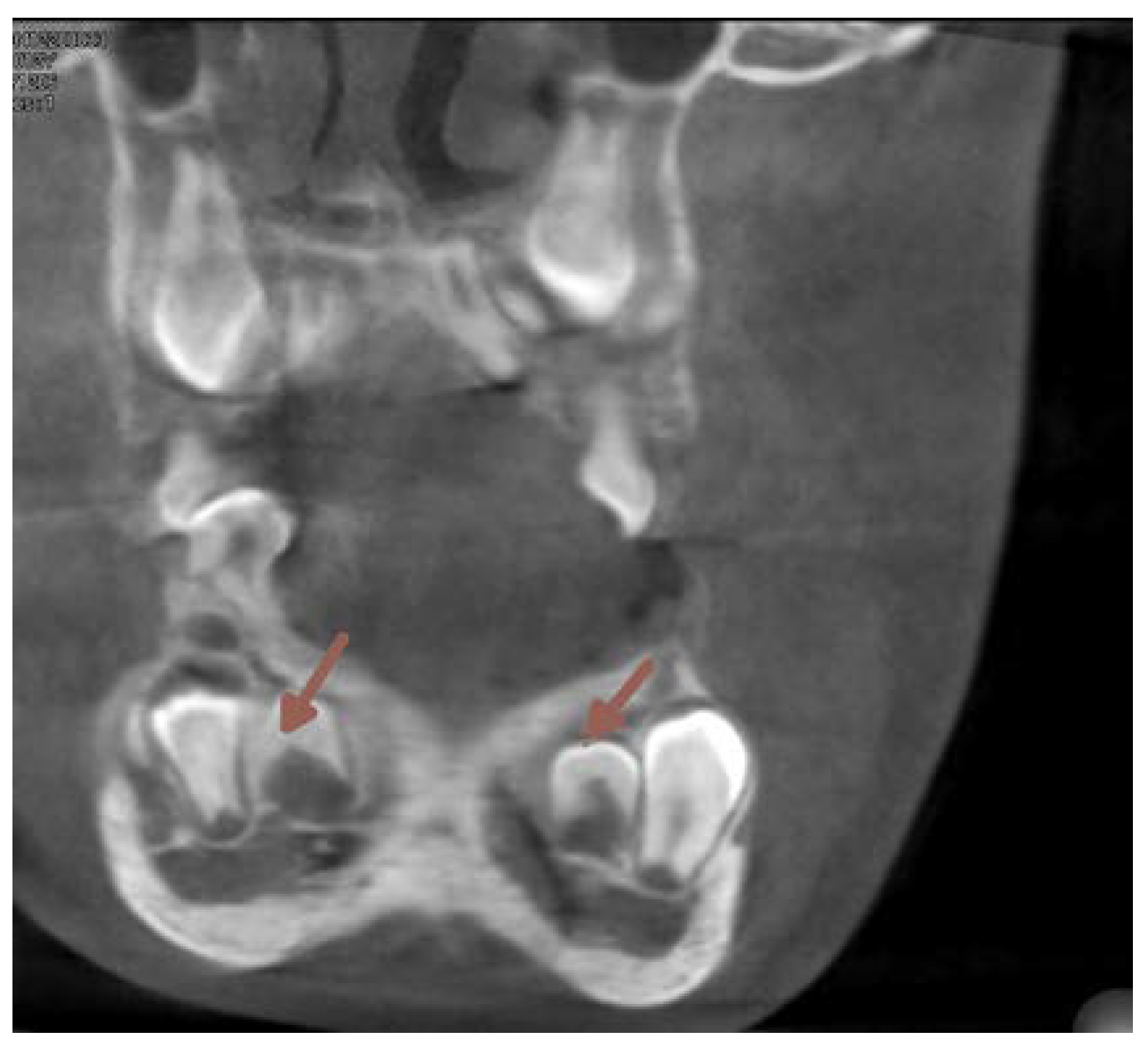

Figure 9.

The CBCT taken in 2017. Axial section on the level of premolars .

Figure 9.

The CBCT taken in 2017. Axial section on the level of premolars .

2.2.3. Surgical Intervention 2 (GENERAL anesthesia)

In April 2018, the patient´s age was 13 years 5 months, the dental age was 8 years. Under general anesthesia, two supernumerary teeth in the lower right and one in the lower left quadrant were extracted. (

Figure 5.,10.) 3 primary teeth were extracted as well (73,83 and 84). This cleared the way for the anticipated spontaneous eruption of lower canines and first premolars. (

Figure 10.) One supernumerary tooth with an underdeveloped root in the area of 35 was subsequently extracted from the chair under local anesthesia. (

Figure 10.) Unfortunately the path of eruption of the 33 and 43 was too close to the apical area of the 42 and 32, (

Figure 10, 11.), so an additional surgical intervention was planned, in local anesthesia, to expose the lower canines and redirect their eruption. This required already a fixed orthodontic appliance placement to anchor proposed lower canine traction.

Figure 10.

OPG x-ray after the 2nd surgical intervention under general anesthesia. (2018).

Figure 10.

OPG x-ray after the 2nd surgical intervention under general anesthesia. (2018).

Figure 11.

Situation in 2019, orthodontic treatment planning.

Figure 11.

Situation in 2019, orthodontic treatment planning.

2.2.4. Orthodontic-Surgical Treatment

Approximately one year later the oral hygiene level, spontaneous changes in the intraoral environment, and eruptional activity of some permanent teeth fulfilled the following conditions, which make efficient orthodontic force application possible :

a) A sufficient number of erupted anchor teeth.

b) Adequate root developmental stage of those teeth to apply extraneous force to bring them into the dental arch due to adequate eruption potential.

c) Possibility to create adequate space for the unerupted teeth.

Figure 12.

Cast model. Anterior crossbite.

Figure 12.

Cast model. Anterior crossbite.

Figure 13.

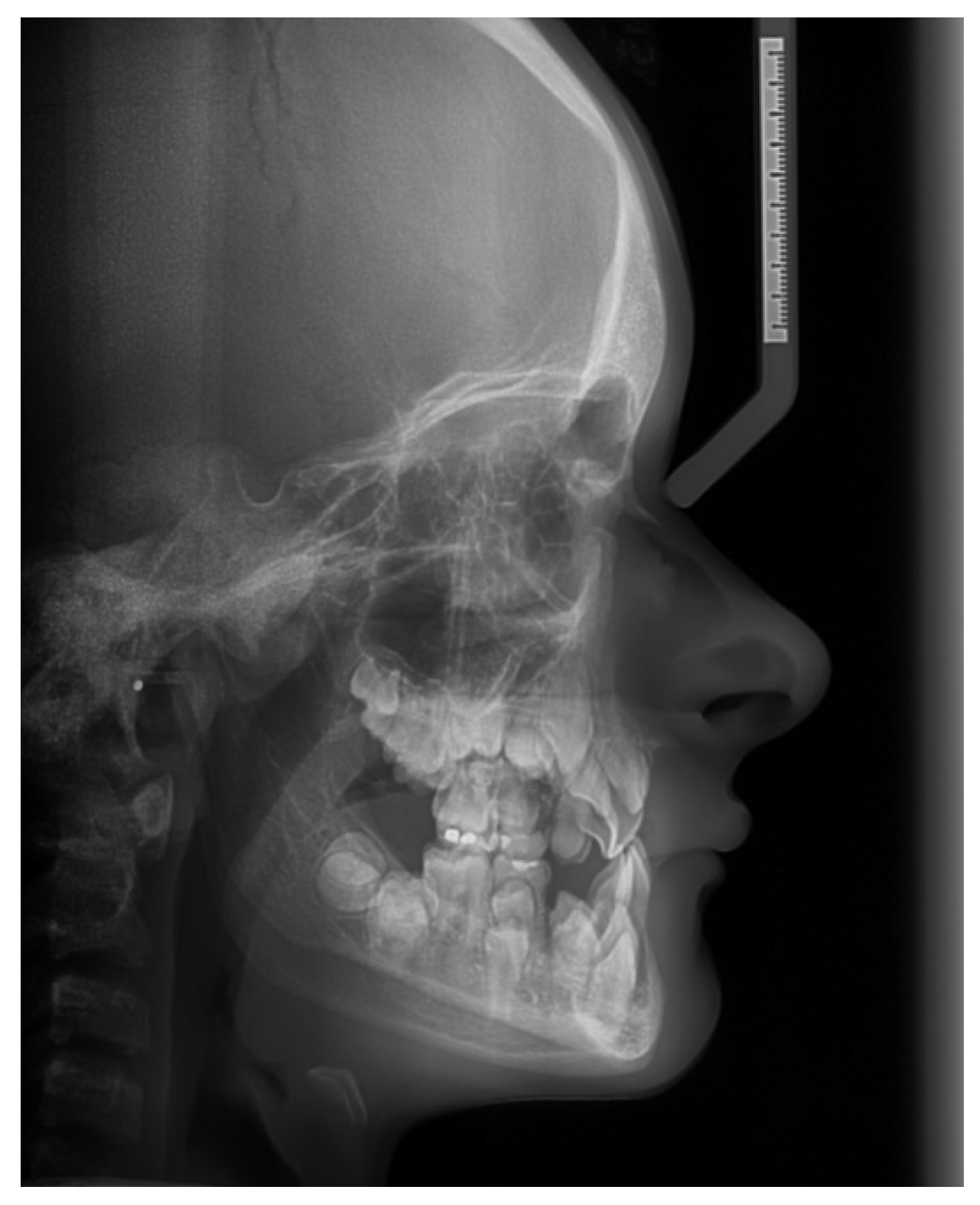

Pretreatment lateral cephalometric radiograph. The analysis of the cephalometric x-ray revealed. a normal saggital relationship of the jaws. Note the delayed fusion of fontanels.

Figure 13.

Pretreatment lateral cephalometric radiograph. The analysis of the cephalometric x-ray revealed. a normal saggital relationship of the jaws. Note the delayed fusion of fontanels.

In June 2019 the patient was first examined at the Orthodontic department of the Clinic of Stomatology of Teaching Hospital in Hradec Králové. A cephalometric x-ray was taken and an up-to-date panoramic x-ray -OPG. Orthodontic impressions were taken and both a cephalometric x-ray and a cast model analysis were executed.

Cephalometric Analysis

The results of the cephalometric picture analysis were promising. (

Figure 13.) The relationship in the saggital position of the jaws was in the Ist Class, (ANB 1,4° and the Wits appraisal – 0,9 mm ) against our expectations. The CCD patients frequently have underdeveloped maxilla in all directions. The saggital position values of the anterior border of the maxilla and mandible (A and B) were enlarged, due to the underdevelopment of the sutures of the skull – the reference point N lies on the nasofrontal suture. The pronounced anterior crossbite was due to the very steep interincisal angle, (1+1- 166,5°) and the upper incisors were severely palatally inclined (1-NS 89,2°). The lower incisors were in correct position (1-ML 85,6°). There was a significant anterior rotational tendency of growth of the lower jaw (SGo/NMe 80% and the NS-ML 18,7°). (

Table 1)

Cast Model and Panoramic X-ray Picture Analysis

There was a ClassI relationship in the molars on both sides, but mild crossbite was present on the left lateral area. The overjet was – 1 mm, but the overbite was +6 mm. The dental age was 9-10 years, but there were missing 11 and 22, and one erupted premolar in the right upper quadrant. There were only permanent incisors and permanent first molars present on the upper cast model. (

Figure 12.) On the OPG x-ray it had been verified that the lower canines´ root developmental stages comply with the dental age 9-10. The 11 and 22 were delayed in eruption. All second and third molar teeth buds were present. (

Figure 11.)

Orthodontic Treatment Plan

1. Full lower fixed appliance – for expansion of sufficient space for the teeth 33,43 and after spontaneous elimination of the 75 and 85 for the 35 and 45.

2. Surgical exposure of 33 and 43 and attachment of brackets on them.

3. Full upper fixed appliance – to anchor forces to pull the 11 and 22 into the arch.

4. Surgical exposure of 11 and 22.

5. Alignment of the upper incisors into correct overjet and overbite. Transversal expansion of the upper arch. Attachment of brackets on the 45 and 35 and alignment.

6. If necessary – a third surgical intervention under general anesthesia to extract newly formed supernumerary teeth in the upper alveolar bone.

7. Two regular premolar extractions to provide sufficient space for upper canines.

8. The aim of the treatment was IInd Class in molars, correct overjet and overbite relationships in the incisor area, and alignment of the lateral crossbite on the left side.

9. No implant placement was considered.

The orthodontic treatment plan was communicated to the parents one week later.

Placement of fixed orthodontic appliances first in the upper dental arch was necessary, (bands on the first molars and brackets 018´´ Roth description) on 21 and 12, 14 and to enhance the anchorage segment deciduous teeth of 63 and 65 were included to the appliance. This phase of the treatment aimed to align upper permanent teeth to provide sufficient anchorage for the orthodontic pull of ankylotic 11 and 22, (

Figure 10.) and to create adequate transversal width of the upper dental arch, which was performed by an individually prepared bihelicoid transpalatal arch. To align the anterior crossbite in the incisor area, and to prevent unwanted interference of teeth from the lower dental arch, the patient received a lower removable splint.

Surgical Intervention 3 (Local Anesthesia)

In June 2020, the incisors 22 and 11 were palpable under the vestibular mucosa. In local anesthesia (LA) the patient underwent a surgical exposure of 22 and 11, it was fixed a hook-shaped attachment on both teeth immediately and the incisors were placed under immediate load. (

Figure 14). In December 2020 regular orthodontic brackets Roth prescription 018´´ were attached to the surface of 22 and 11.

Orthodontic Treatment with Fixed Appliance – Phase 1

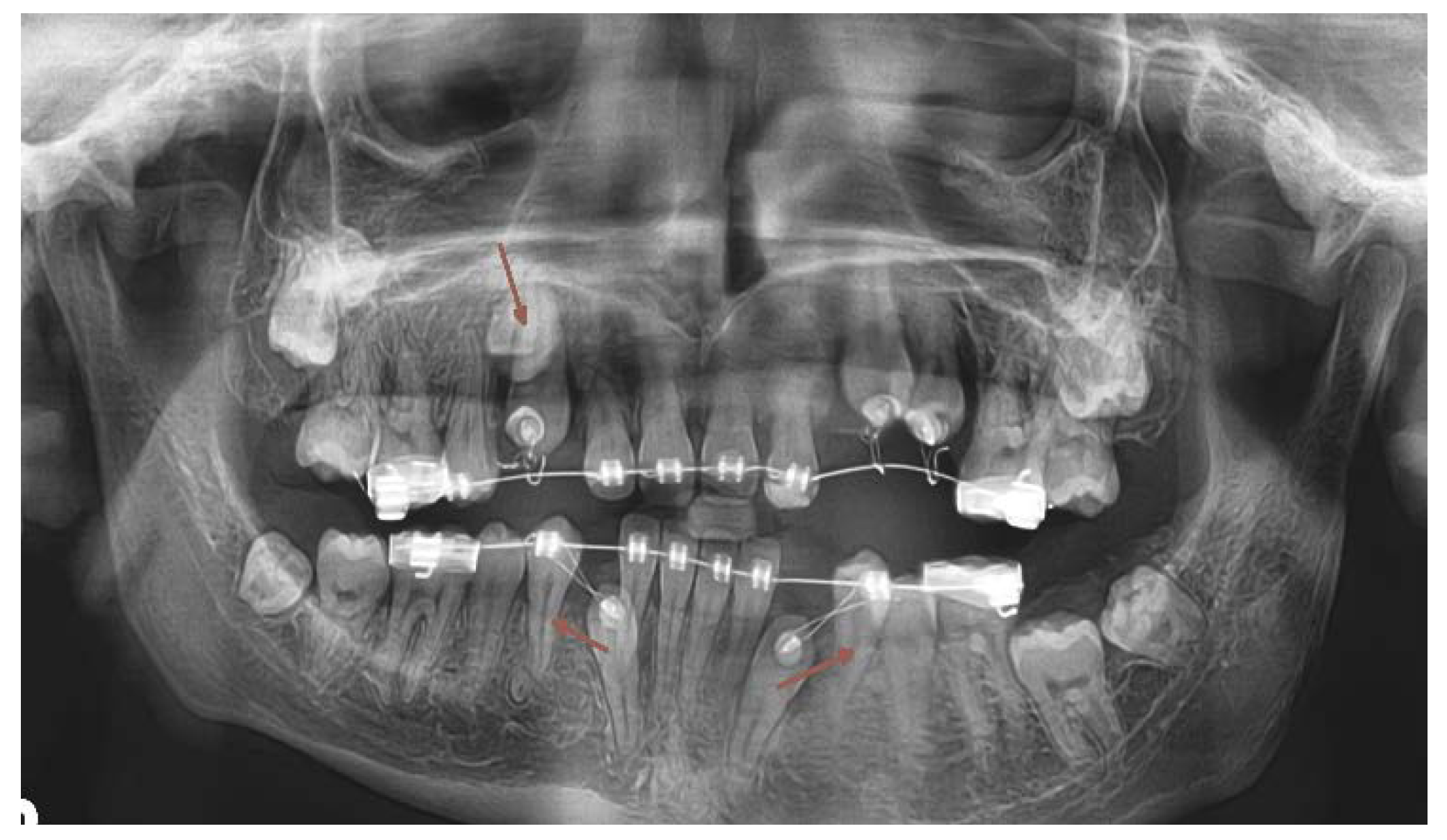

A follow-up OPG x-ray was taken in January 2021 (

Figure 14) . According to the image analysis, the 45 and 35 roots were mature enough and revealed satisfactory activity to erupt spontaneously. Placement of lower fixed appliance followed. Orthodontic bands on the teeth 36 and 46, brackets to the 34, 44 and to the lower incisors, (018´´, prescription Roth) were attached. A space had been forming for the 45 and 35. According to the superimposition of the last two OPG x-rays, the 45 and 35 were erupting spontaneously.

At this time the 33 and 43 were slowing down their eruption, therefore another surgical intervention was needed. Another CBCT scan image was necessary to prove the proximity of the crowns of the lower canines to the apical area of the lower lateral incisors. (

Figure 15).

Surgical Intervention 4 (Local Anesthesia)

In January 2022 a surgical exposure in local anesthesia of 33 and 43 was provided, and the attachment was bonded immediately. The canines were encumbered with light distal forces to avoid interference of the canine crowns with the roots of the lower incisors. (

Figure 16)

Fixed Appliance Orthodontic Treatment- Phase 2

A new OPG x-ray was taken in November 2022 (

Figure 17). The upper incisors were in place and their roots were fully matured. The 45 was already in the correct position, the 35 was in a slightly crowded position, but the lower canines cooperate well with the orthodontic forces. But at this time was already clear, that newly formed supernumerary teeth started to mineralize their crowns in the upper alveolus, two in the upper right and one in the upper left quadrant. (

Figure 17). It was necessary to plan a third surgical intervention under general anesthesia.

Surgical Intervention 5 (General Anesthesia)

In March 2023 the patient underwent his 5

th surgical intervention, it was the 3

rd in general anesthesia. Two supernumerary teeth and one regular premolar were extracted from the upper right quadrant and one erupted deciduous tooth and one regular premolar was extracted from the left upper quadrant. Both upper canines and the 24 were exposed, and the orthodontic attachments were immediately bonded. (

Figure 18) One supernumerary tooth was left in the upper right quadrant due to unfavorable anatomical conditions with risk of alveolar bone loss. (

Figure 18)

2.2.5. Further Treatment Planning

The last OPG x-ray was taken in September 2023 (

Figure 18), the patient´s chronological age was 17 years 10 months, dental age was 13. The upper 13,23 and 24 react to the orthodontic forces very well, the 17,27, and 47 show spontaneous eruptional activity of adequate speed. But he 37 remained on its level without any progress in eruptional activity. Another local anesthesia surgical intervention is needed, to mobilize the tooth 37 and to expose it. (

Figure 18) The treatment has not finished yet, it remains to align all the canines and the 24, also surgically to expose, mobilize, and align the 37. The patient has all four 3

rd molar teeth buds, which are spontaneously erupting.

Table 2.

The number of extracted and exposed teeth during the 5 surgical interventions.

Table 2.

The number of extracted and exposed teeth during the 5 surgical interventions.

| Exposed teeth for orthodontic traction |

Permanent extractions |

Primary extractions |

Supernumerary extractions |

|

| 0 |

0 |

4 |

3 |

1st surgery (GA) June 2013 |

| 0 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

2nd surgery (GA) April 2018 |

| 2 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

3rd surgery (LA) June 2020 |

| 2 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

4th surgery (LA) January 2022 |

| 2 |

2 |

1 |

2 |

5th surgery (GA) March 2023 |

3. Discussion

Cleidocranial dysplasia is characterized by a general dysplasia with various skeletal and dental deformities. Dental anomalies are a characteristic feature of CCD. The most significant dental anomalies are multiple supernumerary teeth emerging often in successive waves. Other typical features are ankylosed permanent successors and delayed dental age. [

10]. Remnants of the imperfectly or late disintegrated Hertwig ´s sheath can appear mineralization activity and give an option for newly formed supernumerary teeth. [

15] Therefore sometimes additional surgical procedures under general anesthesia may be necessary.

Craniofacial abnormalities are expressed in over 80% of the cases including skeletal Cass III tendency and mandibular prognathism and short anterior cranial base. [

5] Thus it is important to critically analyze the appropriateness of using standard cephalometric values. [

13] Despite hypoplastic maxilla, the cephalometric values have been contradictory normal, showing SNA angles close to 90°. The error emerges from the incorrectinterpretation of the point N (Nasofrontal suture) which is a basic reference point in the majority of cephalometric analyses. Provided that there is limited growth of the cranial base and depressed nasal bridge, the position of the Nasofrontal suture point is unusual and it is misleading to compare the position of both points A and B to it. [

12] Thus it´s reasonable not to overestimate the results of SNA and SNB measurements and better interpret the ANB angle, and Wits appraisal. [

12] Our patient had 1,4°of ANB angle, which is within normal ranges as well as the Wits which was -0,9°. This sign that there was no sign of Class III tendency, patient is saggitally well in Class I.

Although maxillary hypoplasia has been commonly described in CCD patients, cephalometric values have been contradictory, showing normal SNA angles. [

5,

12] The interincisal angle is usually significantly larger in CCD patients compared to unaffected individuals. There are marked lingual inclinations of lower incisors confirming the skeletal Class III tendency. [

12]

Regarding the mandible, cephalometric analysis [

12] results support the presence of a prognathic mandible. Clinically evident pseudoprogenia is due to marked midface hypoplasia rather than mandibular hyperplasia [

12]. The anterior cranial base is short, leading to a posterior position of the nasofrontal suture. The whole midface of these patients is usually poorly developed. Reduced vertical development of the midface may lead to significant anterior rotation of the mandible. The vertical facial growth may be impaired due to reduced alveolar bone development. [

5]

Beside the assessment of antero-posterior relationships, the mandibular hypodivergency has been consistently reported, where counter-clockwise (CCW) mandibular rotation was typical. Such forward rotation might be caused by a reduced vertical development of the midface, hypoplasia of facial bones, and underdevelopment of paranasal sinuses. Our patient manifested 80% of SGo/NMe angle which signs purely CCW rotational tendency, as well the NS-ML 18° angle.

The interincisal angle of CCD patients is usually larger than control groups. Our patient had 166,5° which corresponds with the findings of the CCD patients. [

12] The lower incisors were almost in the correct position (1-ML 86,5°), so the reversed bite was almost entirely result of poor upper incisor inclination (1-NS 89,2°). After we have orthodontically aligned the upper incisor inclination, the correct overjet situation is established.

Treatment options include removal of retained deciduous and supernumerary teeth, exposure, and orthodontic traction of impacted and ankylosed permanent teeth. [

1,

16,

23] Correct timing of extractions of milk predecessors and supernumerary teeth was essential to make the most of the spontaneous activity of permanent successors. [

19,

22] Panoramic x-ray images were thus taken on a regular basis and proper dental age assessment [

22] was conducted.

Dental age estimation was conducted on panoramic X-rays subsequently taken once in 6-9 months. The dental age was calculated through the mineralization phases of the roots and crowns of permanent successor teeth and their age of eruption using the Demirjan method [

31] . This method recently is not considered accurate enough [

25] but it is sufficient for our CCD patients [

26,

28]. There are several supernumerary teeth in various degrees of maturation and also missing teeth visible on the panoramic picture [

17] thus the estimate loses its accuracy so it is reasonable to specify the developmental stage of every individual tooth separately, especially those that will be orthodontically pulled to the dental arch. In CCD patient it is essential to realize, that the dental age is usually delayed to the chronological age of the patient to average 3 years [

30]. In addition the skeletal age of the patient is also often delayed to the chronological age but to different extent. Yet we have been using the Demirjan approach to determine approximately the dental age of the patient assessing separately the upper and the lower dental arches. Than we specify the timing of the intervention by assessing the developmental phase of the root of the tooth to be exposed or which tooth eruption is to be accelerated by premature deciduous extraction. It is impossible to use the chronological age as a guide to accurately time the surgical interventions especially those under general anesthesia. n some questionable situations, the panoramic view does not provide enough information, and it was better to provide CBCT. [

8] Surgical exposition, mobilization of impacted successors, and immediate attachment bonding were a rule, the force load followed the latest in one week. The anchorage of tractions was provided on teeth, tooth borne anchor segments were amplified by including overretained immobile milk predecessors to the arch involving them for a necessary period. The traction force level was rather low so, as not to overload the anchor segments. Provided that the surgical mobilization of the impacted teeth was correct, this force level was sufficient and allowed the use of lighter wirework mechanotherapy to facilitate vertical bone regeneration [

18]. Descending teeth caused reposition of missing alveolar bone lost by supernumerary extractions.

Dental management of individuals with CCD is challenging and involves orthodontic and surgical treatments. The four main therapeutic approaches published in the literature are the Toronto-Melbourne, Belfast-Hamburg, Jerusalem, and Bronx methods [

2,

5,

6]. The Toronto-Melbourne approach [

6] offers a series of several extensive and minor surgical procedures over a long period. This approach is based on age. The best period for treatment begins at the dental age of 5-6 years. The timing of serial extraction of primary teeth depends on the extent of the root length developed in permanent teeth [

2]. Supernumerary teeth are often extracted with the alveolar bone covering the impacted teeth. The rationale of this approach is to facilitate the spontaneous eruption of impacted permanent teeth [

2] and where needed, orthodontic traction is applied. [

2,

6]. Our patient underwent 3 surgical interventions under general anesthesia, but these were of minor extent, operated on only one of the jaws at one time. Provided that new supernumerary teeth can emerge into the jaws by time [

11,

17], early general anesthesia surgery can appear later as unsatisfactory, and the patient has new superfluous teeth in his jaw as he matures. Minor oral surgical interventions were also conducted with local anesthesia in case of those teeth which were ankylosed, but palpable under the oral mucosa, or in case of spontaneously erupting supernumerary tooth.

With this approach as much as possible regular teeth were pulled into the arch, and no prosthetic or implant replacement is needed in the future.

4. Limitations of the Case

We have been treating the patient for 10 years now, the patient underwent 3 interventions under general anesthesia and 2 under local anesthesia. It was necessary to expose and load 5 teeth in the upper and 2 teeth in the lower dental arch. The number of extracted supernumerary teeth was 4 in the lower dental arch and 5 in the upper. It was necessary to extract two regular premolars in the upper arch from orthodontic reasons, to align the crowded canines. There was no need to extract all upper deciduous teeth in one operation, we preserved one primary canine and 2 lower second primary molars to serve as an anchor unit. TAD (Temporary Anchorage Device) insertion was not considered, due to the lack of height and thickness of the alveolar bone. All permanent teeth (except the 14 and the 24) anterior to the second molars were successfully brought into the dental arch, either by orthodontic traction or by spontaneous eruption. The tooth 37 probably remains impacted.

After we analyzed the cephalometric x-ray in 2019, we revealed, that fortunately no orthognathic surgery of the maxilla is needed for this patient. Two surgical procedures remain to complete the case, one procedure under local anesthesia to expose and mobilize the 37, and the other is optional – orthognathic surgery under general anesthesia to correct the moderate asymmetric shape of the mandible. As the patient is newly 18 years old, he will give consent for this last phase of therapy by himself.