Submitted:

17 May 2024

Posted:

17 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Method

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Measures

2.4. Data Analyses

2.4.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.4.2. Between-Group Comparisons

2.4.3. Psychometric Properties of CASQ-R

2.4.4. Clusters Estimation

2.4.5. Clusters Characteristics

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Between-Group Comparisons

3.3. Psychometric Properties of CASQ-R

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- 1. Buchanan GM, Seligman MEP. Explanatory style. 1995.

- 2. Seligman MEP, Kaslow NJ, Alloy LB, Peterson C, Tanenbaum RL, Abramson LY. Attributional style and depressive symptoms among children. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 3. Rasmussen HN, Scheier MF, Greenhouse JB. Optimism and physical health: A meta-analytic review. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. [CrossRef]

- 4. Mark G, Smith, AP. Effects of occupational stress, job characteristics, coping, and attributional style on the mental health and job satisfaction of university employees. Anxiety, Stress & Coping. [CrossRef]

- Gordon, RA. Attributional style and athletic performance: Strategic optimism and defensive pessimism. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. [CrossRef]

- 6. Cheng H, Furnham A. Attributional style and personality as predictors of happiness and mental health. Journal of Happiness Studies. [CrossRef]

- 7. Dweck CS, Chiu CY, Hong YY. Implicit theories and their role in judgments and reactions: A word from two perspectives. Psychological Inquiry. [CrossRef]

- 8. Dweck CS, Leggett EL. A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review. [CrossRef]

- 9. Anderman EM, Anderman LH, Griesinger T. The relation of present and possible academic selves during early adolescence to grade point average and achievement goals. The Elementary School Journal.

- 10. Bickett LR, Milich R, Brown RT. Attributional styles of aggressive boys and their mothers. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Houston, DM. Revisiting the relationship between attributional style and academic performance. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 12. McQuade JD, Hoza B, Murray-Close D, Waschbusch DA, Owens JS. Changes in self-perceptions in children with ADHD: A longitudinal study of depressive symptoms and attributional style. Behavior Therapy. [CrossRef]

- 13. Rodríguez-Naranjo C, Cano A. Development and validation of an attributional style questionnaire for adolescents. Psychological Assessment. [CrossRef]

- 14. Erdley CA, Loomis CC, Cain KM, Dumas-Hines F. Relations among children's social goals, implicit personality theories, and responses to social failure. Developmental Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 15. Abela JR, Sarin S. Cognitive vulnerability to hopelessness depression: A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Cognitive Therapy and Research. [CrossRef]

- Muris, P. , Schmidt, H., Lambrichs, R., & Meesters, C. (2001). Protective and vulnerability factors of depression in normal adolescents. ( 39(5), 555–565. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1993; 102(1): 20-28. [CrossRef]

- 18. Voelz ZR, Haeffel GJ, Joiner JTE, Wagner KD. Reducing hopelessness: the interation of enhancing and depressogenic attributional styles for positive and negative life events among youth psychiatric inpatients. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 1183. [CrossRef]

- 19. Bell-Dolan D, Wessler AE. Attributional style of anxious children: Extensions from cognitive theory and research on adult anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. [CrossRef]

- 20. Schleider JL, Vélez CE, Krause ED, Gillham J. Perceived psychological control and anxiety in early adolescents: The mediating role of attributional style. Cognitive Therapy and Research. [CrossRef]

- 21. Caffo E, Forresi B, Strik Lievers L. Impact, psychological sequelae and management of trauma affecting children and adolescents. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. [CrossRef]

- 22. Joiner JTE, Wagner KD. Attributional style and depression in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. [CrossRef]

- 23. Sweeney PD, Anderson K, Bailey S. Attributional style in depression: a meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 24. Lo CS, Ho SM, Hollon SD. The effects of rumination and depressive symptoms on the prediction of negative attributional style among college students. Cognitive Therapy and Research. [CrossRef]

- 25. Scaini S, Caputi M, Ogliari A, Oppo A. The relationship among attributional style, mentalization, and five anxiety phenotypes in school-age children. Journal of Research in Childhood Education. [CrossRef]

- 26. Luo Y, Wu Y. The Relationship Between Self/Value Discrepancies and Anxiety: The Mediation Effect of Depressogenic Attributional Style. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. [CrossRef]

- 27. Abramson LY, Seligman ME, Teasdale JD. Learned helplessness in humans: critique and reformulation. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 28. Gladstone TR, Kaslow NJ. Depression and attributions in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Thompson M, Kaslow NJ, Weiss B, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Children's Attributional Style Questionnaire—Revised: Psychometric examination. Psychological Assessment 1998; 10(2): 166-170. [CrossRef]

- 30. Kaslow NJ, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire—Revised. 1991.

- 31. Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Seligman ME. Learned helplessness in children: a longitudinal study of depression, achievement, and explanatory style. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Seligman ME. Predictors and consequences of childhood depressive symptoms: a 5-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 1992; 101(3): 405-422. [CrossRef]

- 33. Lewis SP, Waschbusch DA, Sellers DP, Leblanc M, Kelley ML. Factor structure of the Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire–Revised. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue, 1: sciences du comportement 2014; 46(2), 2014. [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, M. Children’s depression inventory. Toronto Ontario; 1985.

- 35. Camuffo M, Cerutti R, Lucarelli L, Mayer R. Children’s Depression Inventory, 1988.

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (Version 27.0) [Computer software]. IBM Corp; 2020.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; 2022. URL https://www.R-project.org/.

- 38. Scrucca L, Fop M, Murphy TB, Raftery AE. mclust 5: clustering, classification and density estimation using Gaussian finite mixture models. The R Journal.

- 39. Ciarrochi J, Heaven PCL, Davies F. The impact of hope, self-esteem, and attributional style on adolescents’ school grades and emotional well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 1178. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, EG. Psychometric properties of the children’s attributional style questionnaire. Psychological Reports. [CrossRef]

- 41. Roberts CM, Kane R, Bishop B, Cross D, Fenton J, Hart B. The prevention of anxiety and depression in children from disadvantaged schools. Behaviour Research and Therapy. [CrossRef]

- 42. Salama-Younes M, Zadeh HM, Cunningham E. A Preliminary Validation of a French Version of the Children’s Attributional Style Questionnaire. International Journal of Psychology.

- 43. Sheikh HI, Hayden EP, Singh SM, Dougherty LR, Olino TM, Durbin C, … Klein DN. An examination of the association between the 5-HTT promoter region polymorphism and depressogenic attributional styles in childhood. Personality and Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- 44. Waschbusch DA, Sellers DP, LeBlanc MM, Kelley ML. Helpless attributions and depression in adolescents: The roles of anxiety, event valence, and demographics. Journal of Adolescence. [CrossRef]

- Bar-Tal, D. Attribution analysis of achievement-related behaviour. Review of Educational Research. [CrossRef]

- Beyer, S. Gender differences in causal attributions by college students of performance on course examinations. Current Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 47. Dweck CS, Goetz TE, Strauss NL. Sex differences in learned helplessness: IV. An experimental and naturalistic study of failure generalization and its mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 48. Dweck CS, Mangels JA, Good C. Do high-achieving female students underperform in private? The implications of threatening environments on intellectual Processing. Journal of Educational Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 49. Nelson LJ, Cooper J. Gender differences in children’s reactions to success and failure with computers. Computers in Human Behavior. [CrossRef]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS, Seligman MEP. Sex differences in depression and Explanatory style in children. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 1991; 20: 233-245. [CrossRef]

- 51. Yeo LS, Tan K. Attributional style and self-efficacy in Singaporean adolescents. Journal of Psychologists and Counsellors in Schools. [CrossRef]

- Blanchard-Fields, F. Causal attributions across the adult life span: The influence of social schemas, life context, and domain specificity. Applied Cognitive Psychology. [CrossRef]

- Hess, TM. Adaptive aspects of social cognitive functioning in adulthood: age–related goal and knowledge influences. Social Cognition. [CrossRef]

- 54. Abramson LY, Metalsky GI, Alloy LB. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review. [CrossRef]

- 55. Wang J, Wang X, McWhinnie CM, Xiao, J. Depressogenic Attributional Style and Depressive Symptoms in Chinese University Students: The Role of Rumination and Distraction. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. [CrossRef]

- Dweck, CS. Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 57. Alatorre AI, DePaola RV, Haeffel GJ. Academic achievement and depressive symptoms: Are fixed mindsets distinct from negative attributional style? Learning and Individual Differences. [CrossRef]

- 58. Jiang X, Mueller CE, Paley N. A Systematic Review of Growth Mindset Interventions Targeting Youth Social–Emotional Outcomes. School Psychology Review. [CrossRef]

- 59. Bruder-Mattson SF, Hovanitz CA. Coping and attributional styles as predictors of depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology. [CrossRef]

- 60. Rueger SY, George R. Indirect effects of attributional style for positive events on depressive symptoms through self-esteem during early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. [CrossRef]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CDI total | - | -.314*** | .339*** | -.408*** |

| 2. CASQ-R positive | -.331*** | - | -.280*** | .803*** |

| 3. CASQ-R negative | .167* | -.139 | - | -.797*** |

| 4. CASQ-R total | -.330*** | .753*** | -.756*** | - |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. CDI total | - | -.329*** | .233** | -.366*** |

| 2. CASQ-R positive | -.337*** | - | -.173* | .753*** |

| 3. CASQ-R negative | .266*** | -.243** | - | -.779*** |

| 4. CASQ-R total | -.383*** | .796*** | -.781*** | - |

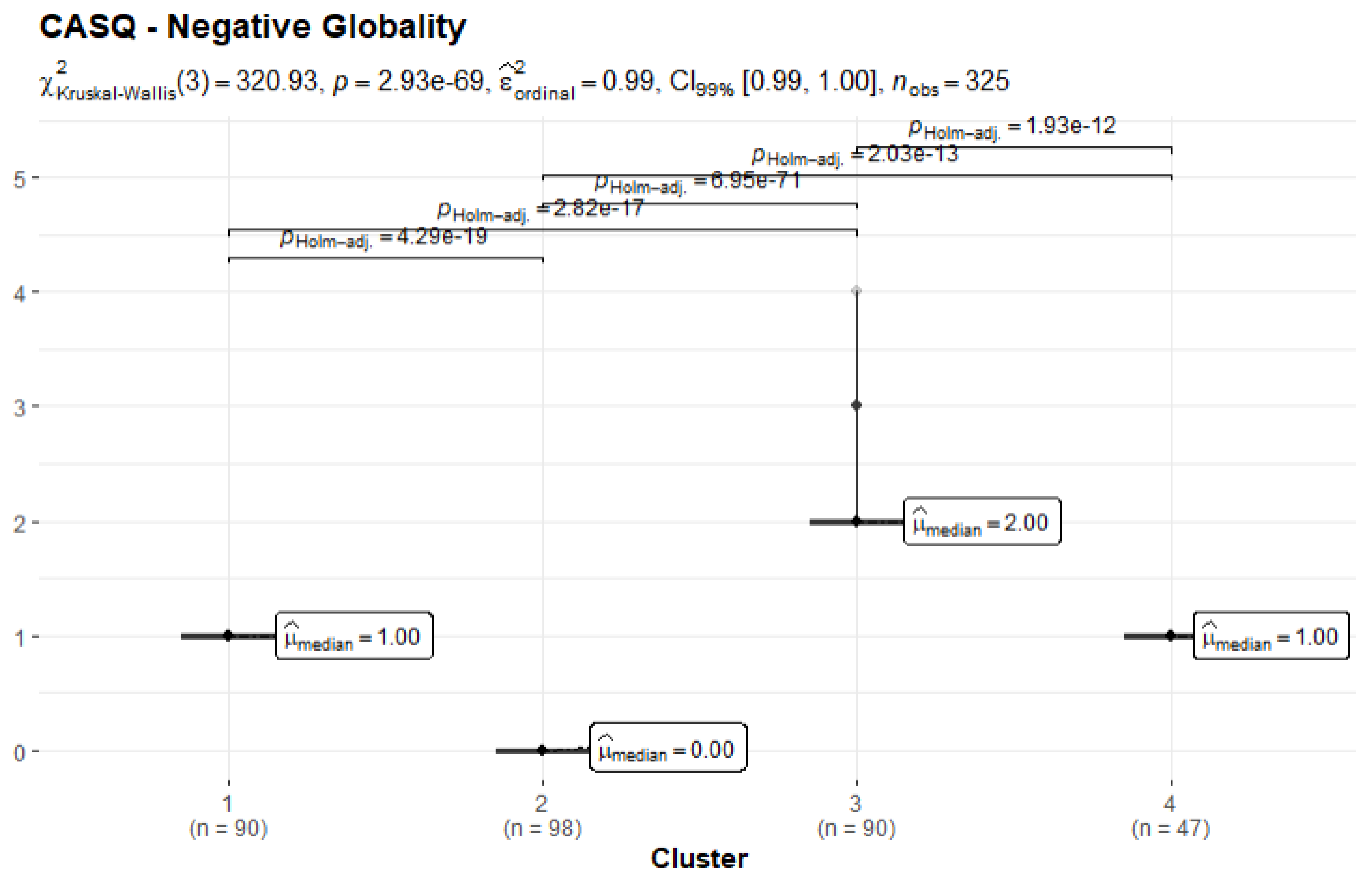

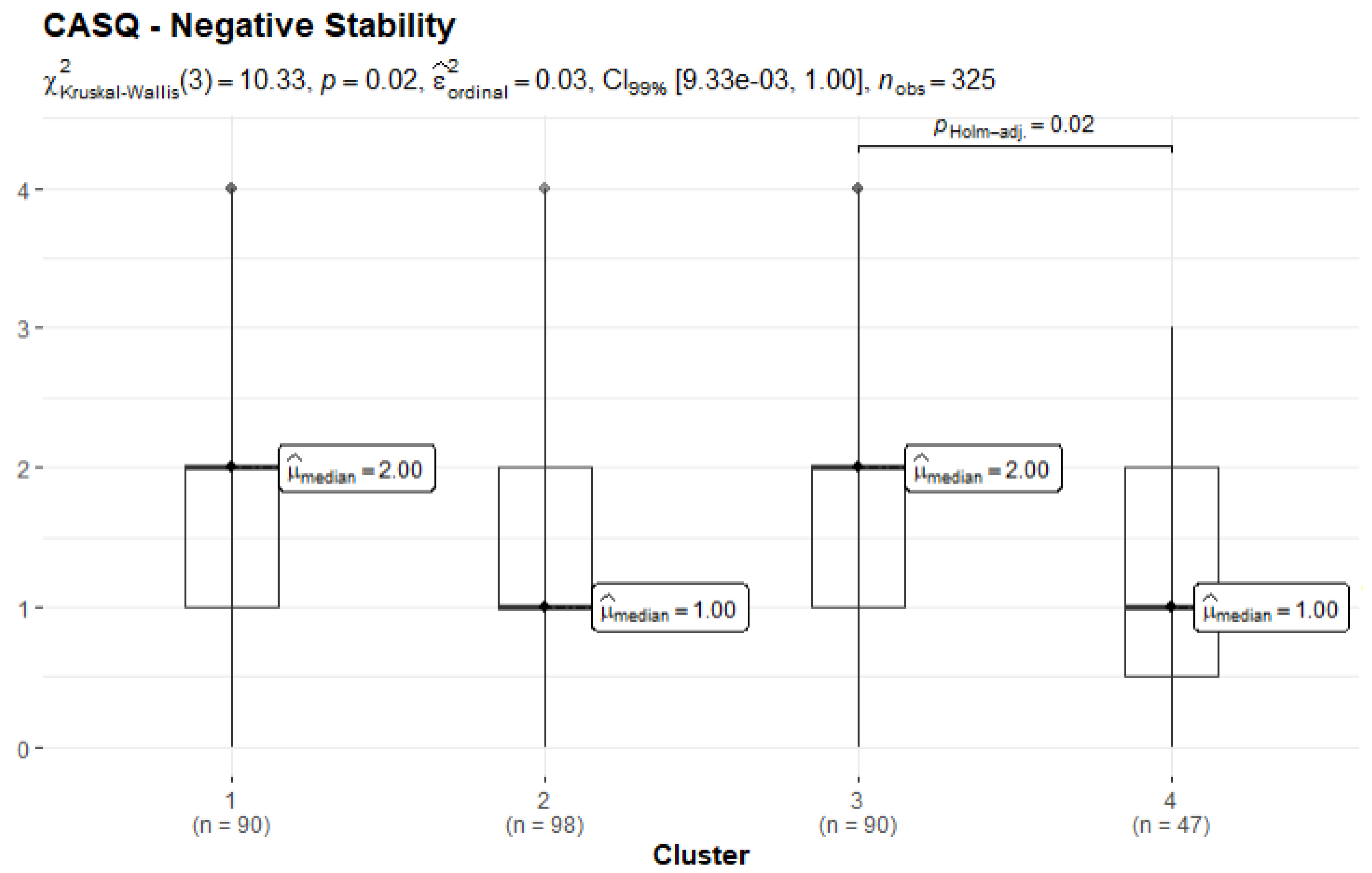

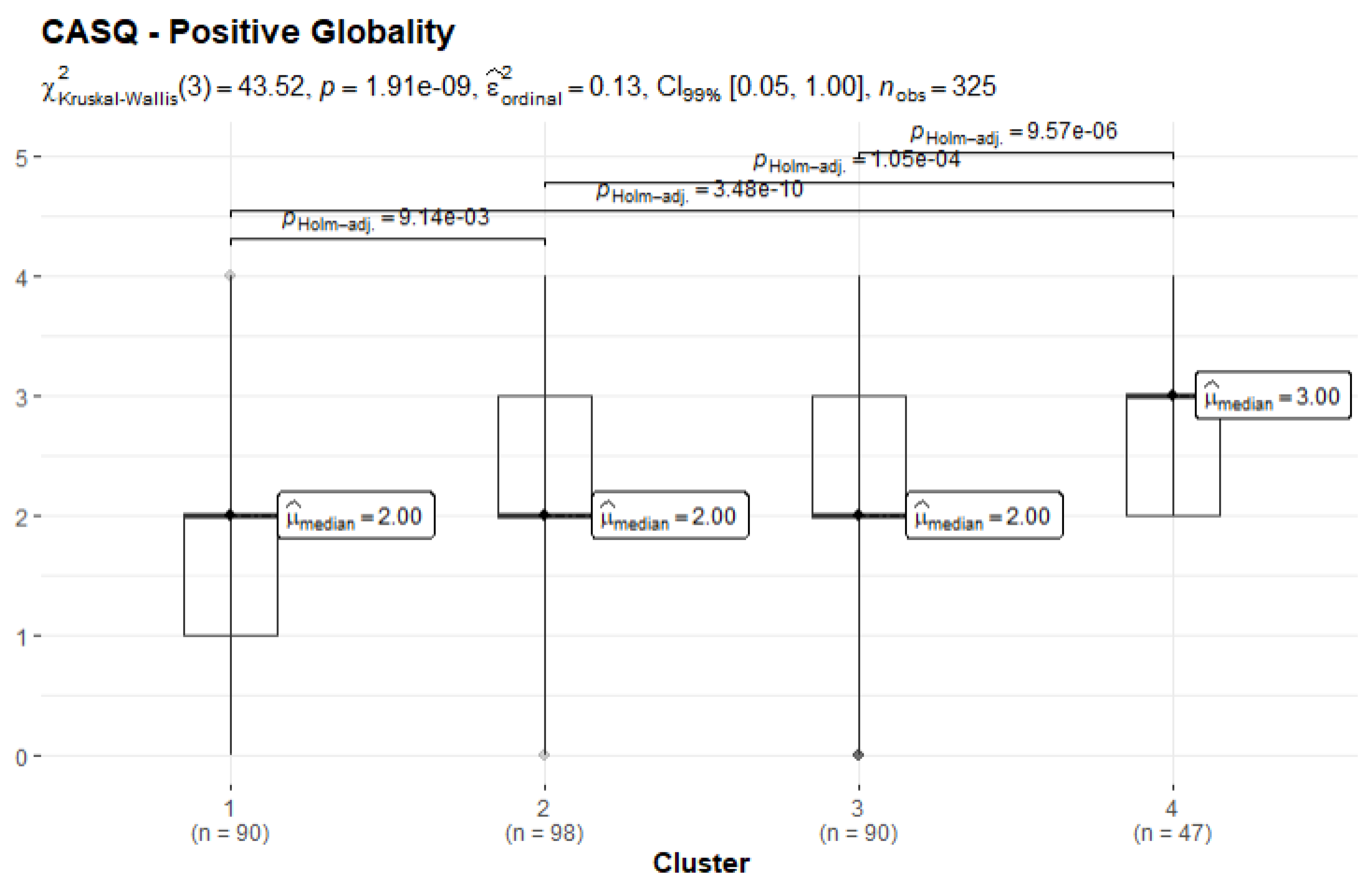

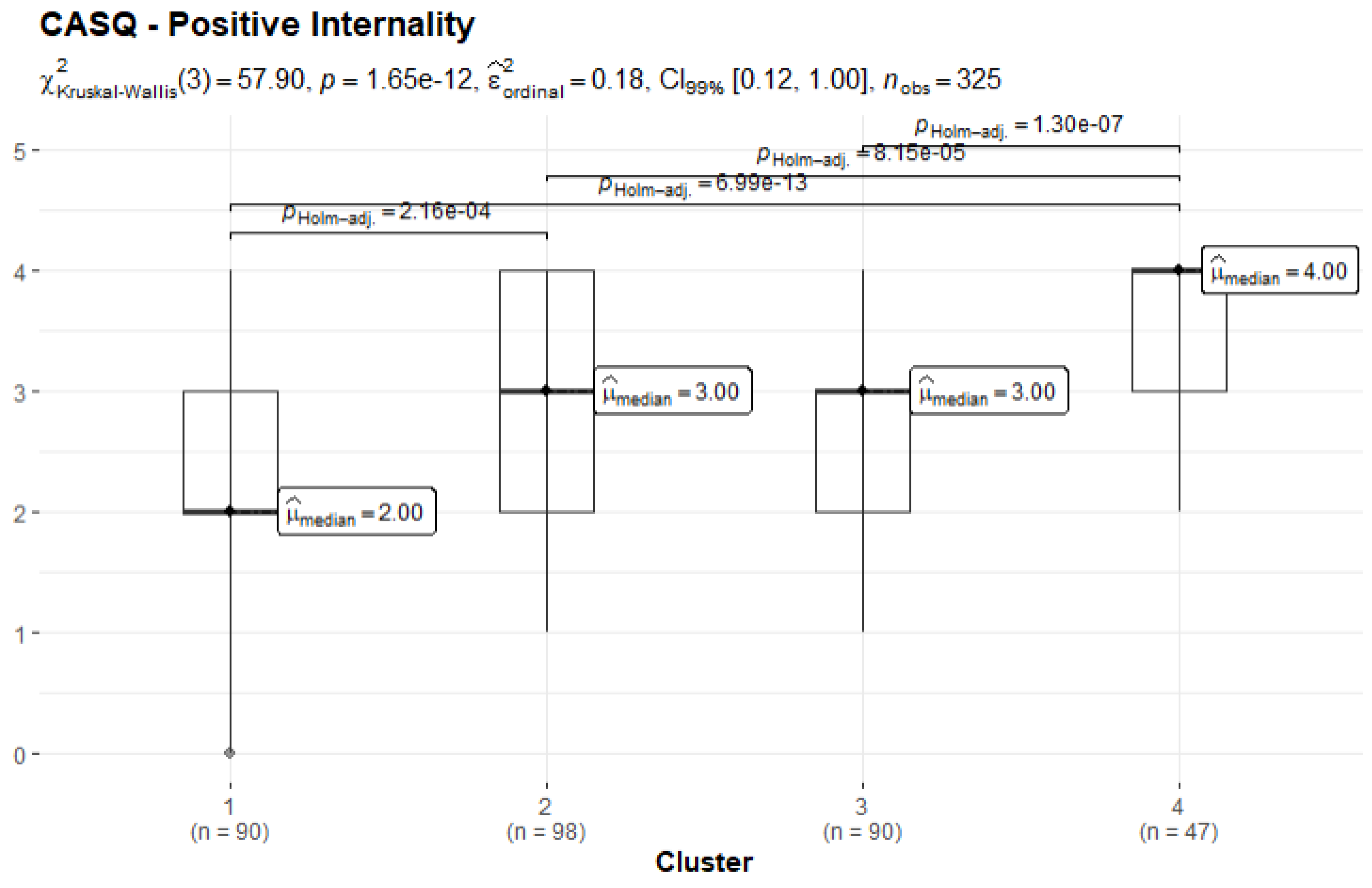

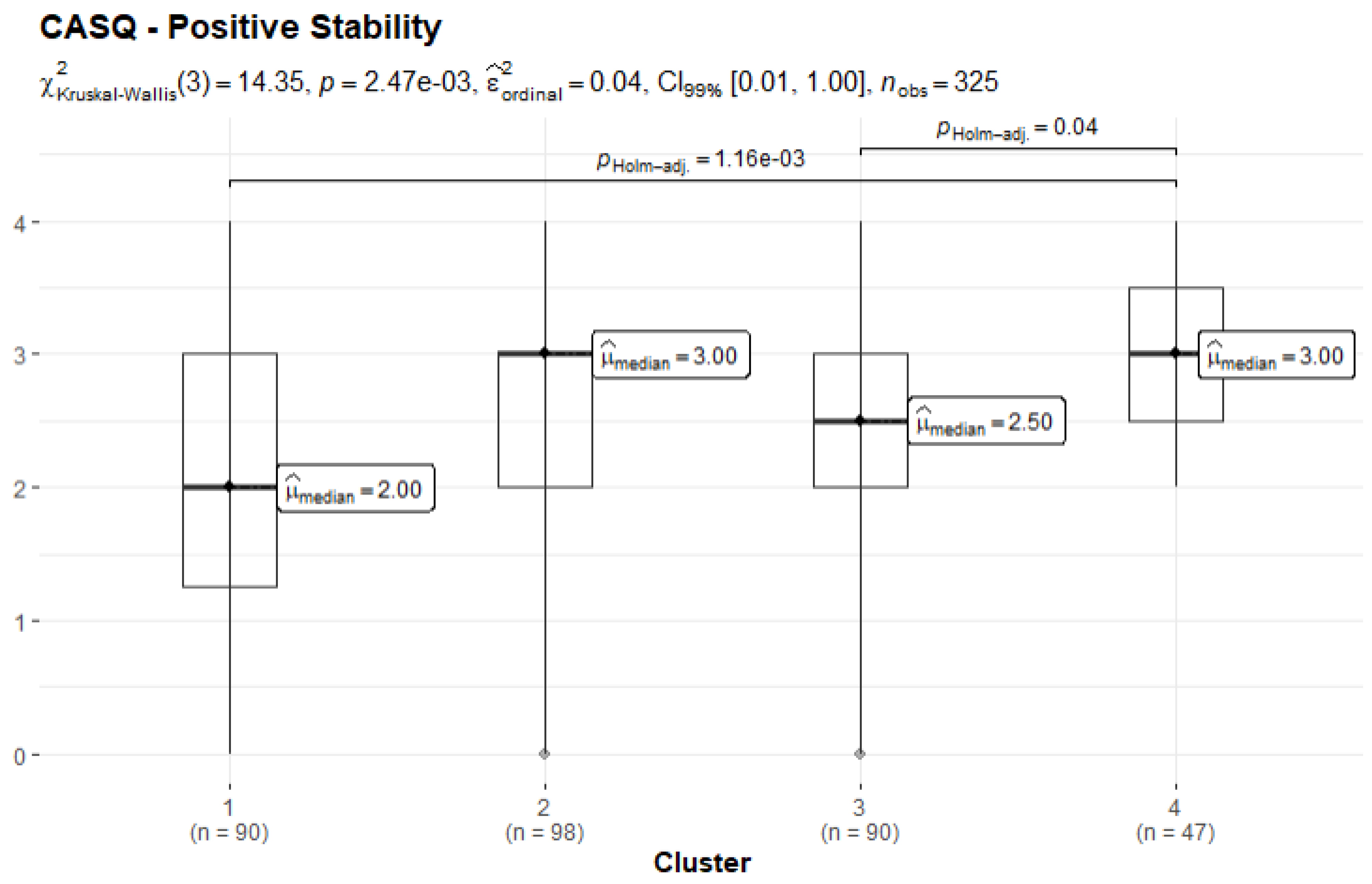

| Cluster | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects (%) | 90 (27%) | 98 (30%) | 90 (27%) | 47 (16%) |

| m ± sd | m ± sd | m ± sd | m ± sd | |

| CASQ-R Negative Globality | 1.00±0.13 | 0.00±0.13 | 2.16±0.21 | 1.00±0.10 |

| CASQ-R Negative Internality | 1.91±0.97 | 1.64±0.97 | 1.80±1.52 | 0.91±0.76 |

| CASQ-R Negative Stability | 1.58±0.98 | 1.35±0.97 | 1.66±1.54 | 1.07±0.76 |

| CASQ-R Positive Globality | 1.80±0.81 | 2.21±0.81 | 2.08±1.27 | 2.83±0.63 |

| CASQ-R Positive Internality | 2.23±0.84 | 2.78±0.83 | 2.52±1.31 | 3.36±0.65 |

| CASQ-R Positive Stability | 2.26±0.96 | 2.60±0.96 | 2.51±1.50 | 2.99±0.75 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).