Submitted:

20 May 2024

Posted:

21 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fly Stocks and Culture

2.2. Chemical Feeding

2.3. Observation of GFP and RFP Fluorescence

2.4. Survival Rate of Larvae Fed the Diet Supplemented with Drugs

2.5. Quantitative Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

2.6. Quantitation of GFP or RFP-Positive Area in CNS

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

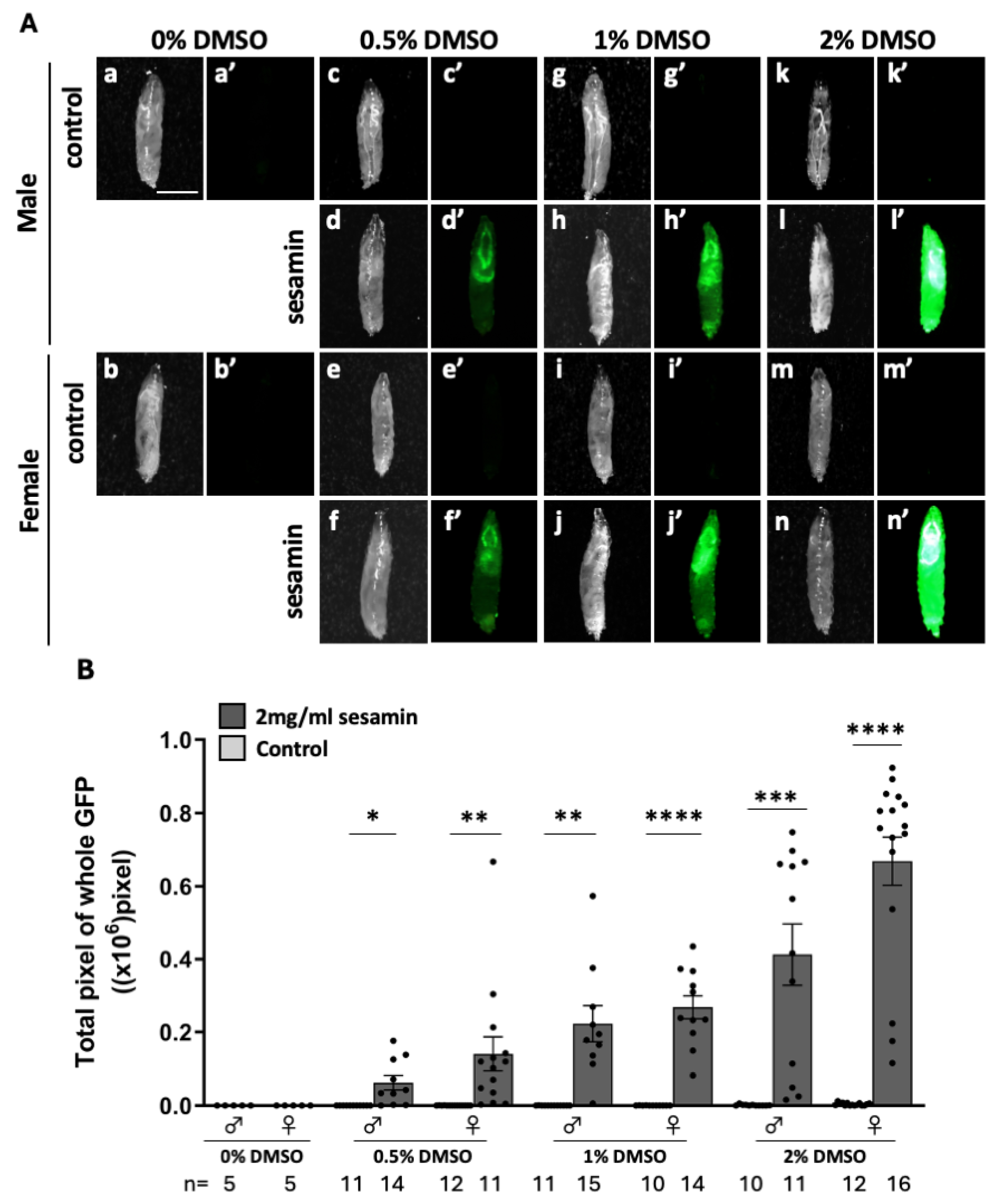

3.1. Sesamin Consumption Activated Nrf2/Cnc in Specific Tissues of Drosophila Larvae

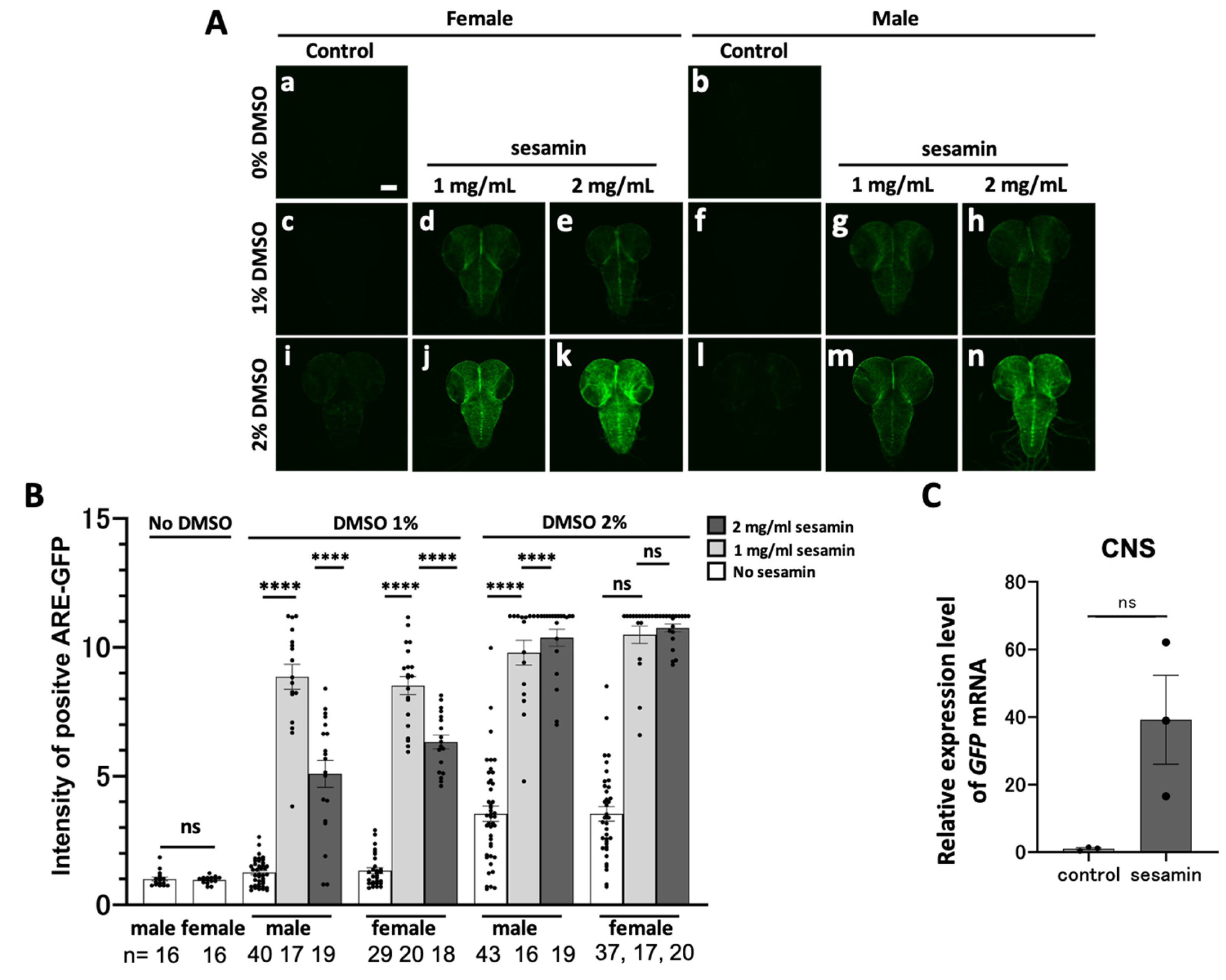

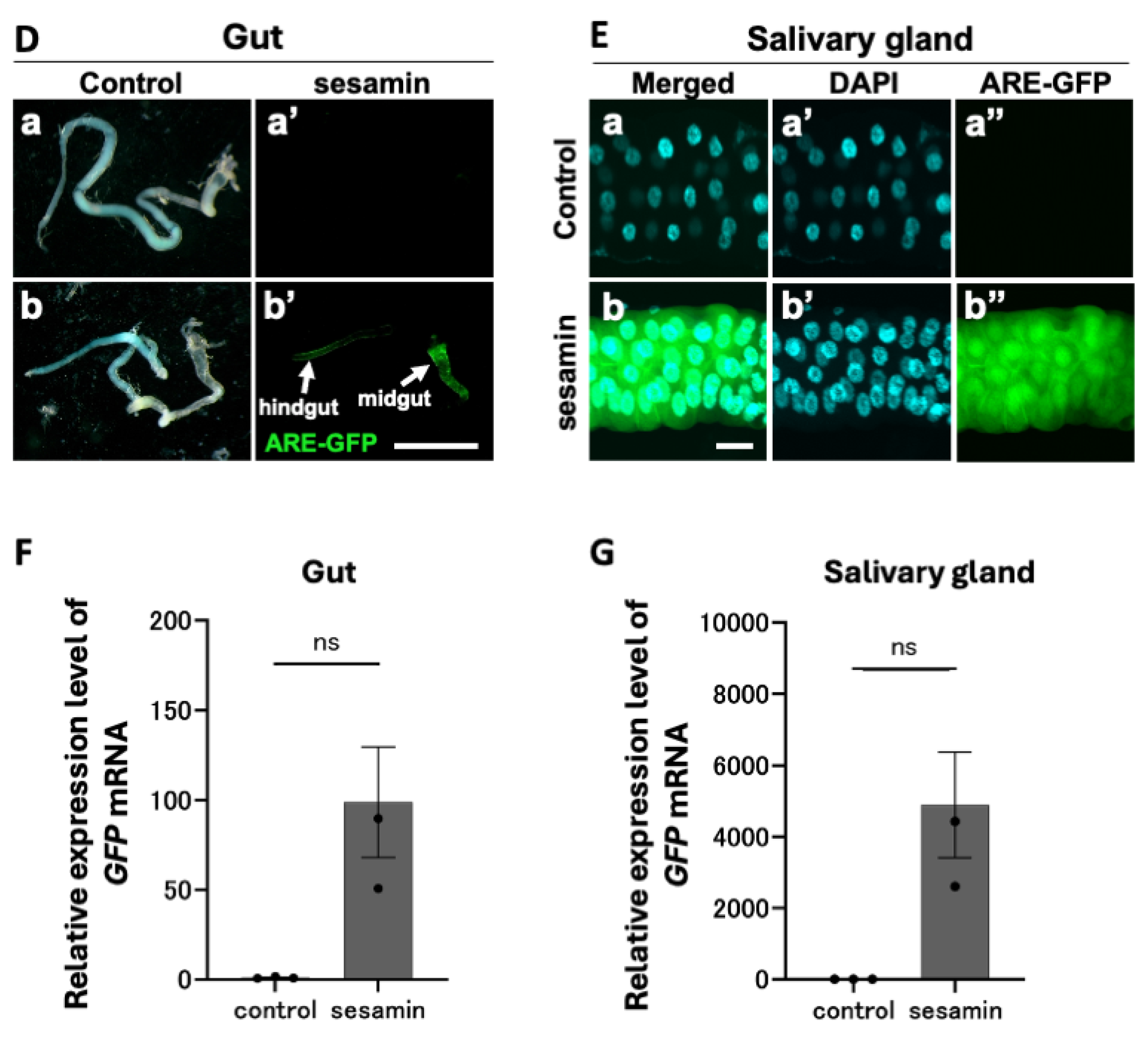

3.2. Sesamin-Consumption Activated Nrf2/Cnc in the CNS and Digestion-related Tissues of Drosophila Larvae

3.3. Activation of Nrf2/Cnc in Glial Cells of the Larval CNS Following Sesamin Consumption

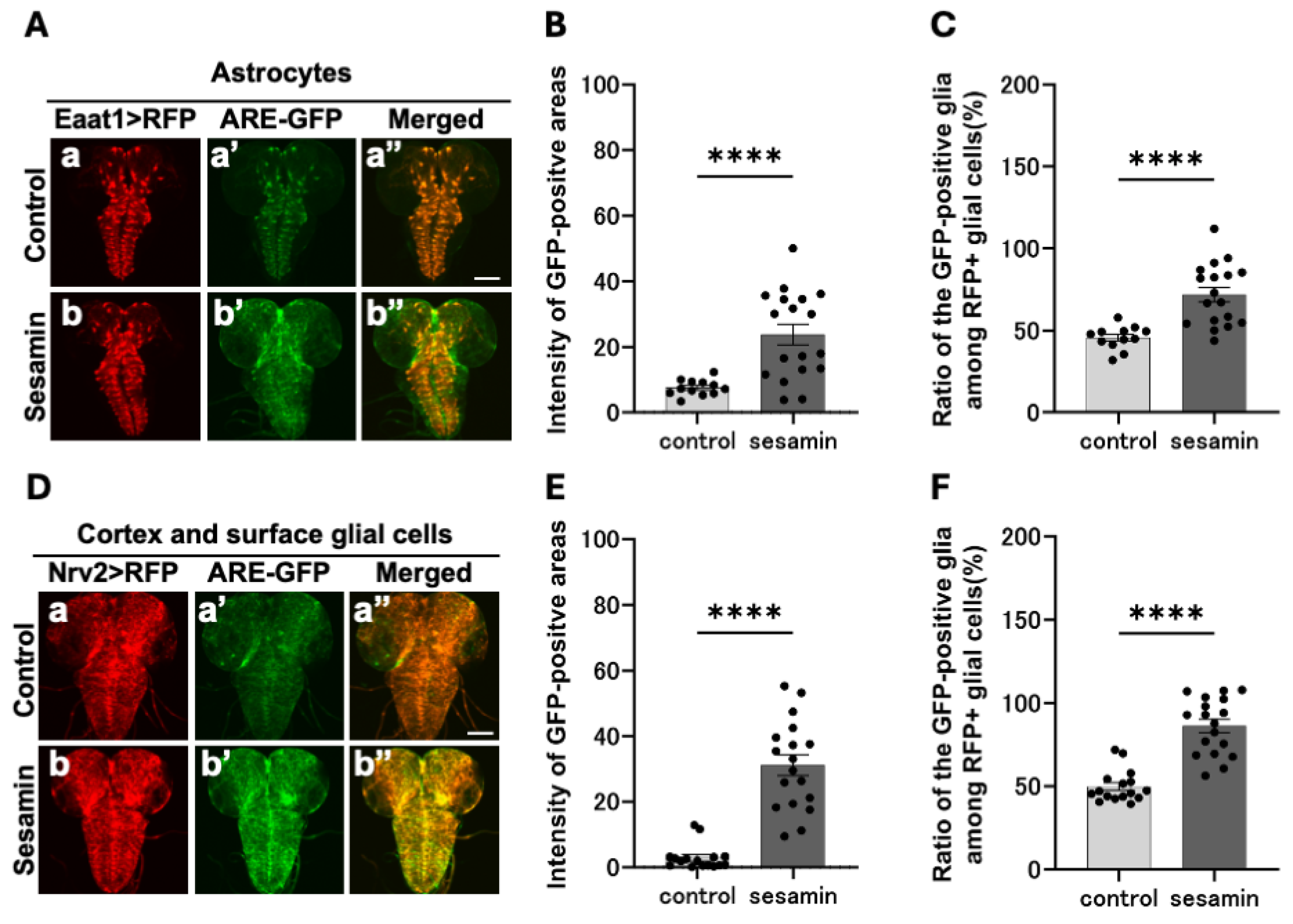

3.4. Sesamin Activated Nrf2 in the Astrocytes, Cortex, and Surface Glia

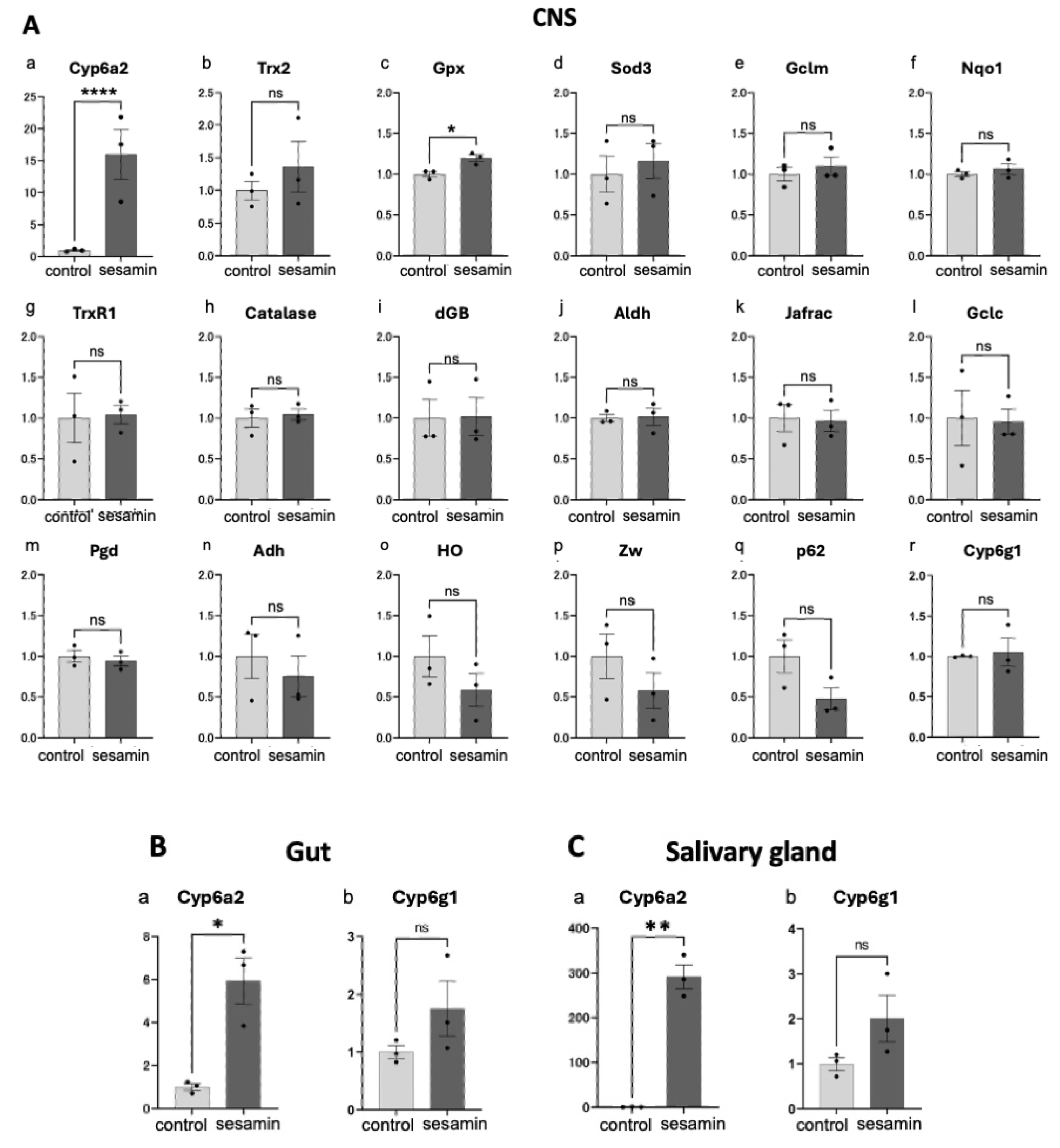

3.5. Sesamin-Consumption in Larvae Elevated the mRNA Levels of Several Genes Encoding Enzymes in Cytochrome P450

3.6. Resistance to the Neonicotinoid Insecticide Imidacloprid Was not Observed in Sesamin-Fed Larvae

4. Discussion

4.1. Activation of Nrf2/Cnc in Specific Larval Tissues by Sesamin

4.2. Activation of Nrf2/Cnc in Larval Glial Cells in CNS by Sesamin

4.3. Induction of Cytochrome P450 Drug-Metabolizing Gene Expression in the Larval CNS and Digestion-Related Tissues by Sesamin and Its Effects on the Organism

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andargie, M.; Vinas, M.; Rathgeb, A.; Möller, E.; Karlovsky, P. Lignans of sesame (Sesamum indicum L.): A Comprehensive Review. Molecules 2021, 26, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimoto, K.; Kitagawa, Y.; Akamatsu, T.; Hirose, N.; Sugano, M.; Shimizu, S.; Yamada, H. Protective effects of sesamin against liver damage caused by alcohol or carbon tetrachloride in rodents. Ann. Nutr. Metab. 1993, 37, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashakumary, L.; Rouyer, I.; Takahashi, Y.; Ide, T.; Fukuda, N.; Aoyama, T.; Hashimoto, T.; Mizugaki, M.; Sugano, M. Sesamin, a sesame lignan, is a potent inducer of hepatic fatty acid oxidation in the rat. Metabolism: Clinical and Experimental 1999, 48, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Gao, Y.; Li, S.; Yang, J. Effect of sesamin on pulmonary vascular remodeling in rats with monocrotaline-induced pul monary hypertension. China journal of Chinese materia medica 2015, 40, 1355–1361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le, T.D.; Nakahara, Y.; Ueda, M.; Okumura, K.; Hirai, J.; Sato, Y.; Takemoto, D.; Tomimori, N.; Ono, Y.; Nakai, M.; Shibata, H.; Inoue, Y.H. Sesamin suppresses aging phenotypes in adult muscular and nervous systems and intestines in a Drosophila senescence-accelerated model. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019, 23, 1826–1839. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le, T.D.; Inoue, Y.H. Sesamin Activates Nrf2/Cnc-dependent transcription in the absence of oxidative stress in Drosophila adult brains. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawanishi, S.; Hiraku, Y.; Oikawa, S. Mechanism of guanine-specific DNA damage by oxidative stress and its role in carcinogenesis and aging. Mutat. Res. 2001, 488, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glei, M.; Schaeferhenrich, A.; Claussen, U.; Kuechler, A.; Liehr, T.; Weise, A.; Marian, B.; Sendt, W.; Pool-Zobel, B.L. Comet fluorescence in situ hybridization analysis for oxidative stress–induced DNA damage in colon cancer relevant genes. Toxicol. Sci. 2007, 96, 279–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandrasekaran, A.; Idelchik, M.d.P. S.; Melendez, J.A. Redox control of senescence and age-related disease. Redox Biol. 2016, 11, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hedge, M.; Lortz, S.; Drinkgern, J.; Lenzen, S. Relation between antioxidant enzyme gene expression and antioxidative defense status of insulin-producing cells. Skelet. Muscle 1997, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman, H.N.; Rolfo, M.; Ferraris, A.M.; Gaetani, G.F. Mechanisms of protection of catalase by NADPH: KINETICS AND STOICHIOMETRY. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 13908–13914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirotsu, Y.; Katsuoka, F.; Funayama, R.; Nagashima, T.; Nishida, Y.; Nakayama, K.; Engel, J.D.; Yamamoto, M. Nrf2-MafG heterodimers contribute globally to antioxidant and metabolic networks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, 10228–10239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moi, P.; Chan, K.; Asunis, I.; Cao, A.; Kan, Y.W. Isolation of NF-E2-related factor 2 (Nrf2), a NF-E2-like basic leucine zipper transcriptional activator that binds to the tandem NF-E2/AP1 repeat of the beta-globin locus control region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1994, 91, 9926–9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venugopal, R.; Jaiswal, A.K. Nrf1 and Nrf2 positively and c-Fos and Fra1 negatively regulate the human antioxidant response element-mediated expression of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996, 93, 14960–14965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Itoh, K.; Chiba, T.; Takahashi, S.; Ishii, T.; Igarashi, K.; Katoh, Y.; Oyake, T.; Hayashi, N.; Satoh, K.; Hatayama, I.; Yamamoto, M.; Nabeshima, Y. An Nrf2/Small Maf heterodimer mediates the induction of phase II detoxifying enzyme genes through antioxidant response elements. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 236, 313–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, M.; Swift, S.R.; Hayes, J.D. Zinc-binding triggers a conformational-switch in the cullin-3 substrate adaptor protein KEAP1 that controls transcription factor NRF2. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2018, 360, 45–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kobayashi, A.; Kang, M.-I.; Watai, Y.; Tong, K.I.; Shibata, T.; Uchida, K.; Yamamoto, M. Oxidative and electrophilic stresses activate Nrf2 through inhibition of Ubiquitination activity of Keap1. Mol.Cell. Biol. 2006, 26, 221–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, N.; Bohmann, D. A versatile ΦC31 based reporter system for measuring AP-1 and Nrf2 signaling in Drosophila and in tissue culture. PLoS One 2012, 7, e34063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Holtzclaw, W.D.; Cole, R.N.; Itoh, K.; Wakabayashi, N.; Katoh, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Talalay, P. Direct evidence that sulfhydryl groups of Keap1 are the sensors regulating induction of phase 2 enzymes that protect against carcinogens and oxidants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2002, 99, 11908–11913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furukawa, M.; Xiong, Y. BTB protein Keap1 targets antioxidant transcription factor Nrf2 for ubiquitination by the Cullin 3-Roc1 ligase. Mol Cell Biol. 2005, 25, 162–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartenstein, V.; Tepass, U.; Gruszynski-Defeo, E. Embryonic development of the stomatogastric nervous system in Drosophila. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994, 350, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakurai, T.; Kanayama, M.; Shibata, T.; Itoh, K.; Kobayashi, A.; Yamamoto, M.; Uchida, K. Ebselen, a seleno-organic antioxidant, as an electrophile. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2006, 19, 1196–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rachakonda, G.; Xiong, Y.; Sekhar, K.R.; Stamer, S.L.; Liebler, D.C.; Freeman, M.L. Covalent modification at Cys151 dissociates the electrophile sensor Keap1 from the ubiquitin ligase CUL3. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2008, 21, 705–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shih, P.-H.; Yen, G.-C. Differential expressions of antioxidant status in aging rats: The role of transcriptional factor Nrf2 and MAPK signaling pathway. Biogerontol. 2007, 8, 71–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidlin, C.J.; Dodson, M.B.; Madhavan, L.; Zhang, D.D. Redox regulation by NRF2 in aging and disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2019, 134, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ikeda, T.; Nishijima, Y.; Shibata, H.; Kiso, Y.; Ohnuki, K.; Fushiki, T.; Moritani, T. Protective effect of sesamin administration on exercise-induced lipid peroxidation. Int. J. Sports Med. 2003, 24, 530–534. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nakai, M.; Harada, M.; Nakahara, K.; Akimoto, K.; Shibata, H.; Miki, W.; Kiso, Y. Novel Antioxidative Metabolites in Rat Liver with Ingested Sesamin. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 1666–1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiso, Y. Antioxidative roles of sesamin, a functional lignan in sesame seed, and it’s effect on lipid- and alcohol-metabolism in the liver: A DNA microarray study. BioFactors 2004, 21, 191–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, W.J.; Ou, H.C.; Wu, C.M.; Lee, I.T.; Lin, S.Y.; Lin, L.Y.; Tsai, K.L.; Lee, S.D.; Sheu, W.H.H. Sesamin mitigates inflammation and oxidative stress in endothelial cells exposed to oxidized low-density lipoprotein. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2009, 57, 11406–11417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takemoto, D.; Yasutake, Y.; Tomimori, N.; Ono, Y.; Shibata, H.; Hayashi, J. Sesame lignans and vitamin E supplementation improve subjective statuses and anti-oxidative capacity in healthy humans with feelings of daily fatigue. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2015, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen, T.M. Oxidative Stress, Redox Imbalance, and the Aging Process. Antioxid. Redox Sign. 2003, 5, 503–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stevenson, R.; Samokhina, E.; Rossetti, I.; Morley, J.W.; Buskila, Y. Neuromodulation of glial function during neurodegeneration. Front. cell. neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.A.; Krantz, D.E. Drosophila melanogaster as a genetic model system to study neurotransmitter transporters. Neurochem. Int. 2014, 73, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lessing, D.; Bonini, N.M. Maintaining the brain: Insight into human neurodegeneration from Drosophila melanogaster mutants. Nature Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nichols, C.D. Drosophila melanogaster neurobiology, neuropharmacology, and how the fly can inform CNS drug discovery. Pharmacol. Therapeut. 2006, 112, 677–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rera, M.; Clark, R.I.; Walker, D.W. Intestinal barrier dysfunction links metabolic and inflammatory markers of aging to death in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 21528–21533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oka, S.; Hirai, J.; Yasukawa, T.; Nakahara, Y.; Inoue, Y.H. A correlation of reactive oxygen species accumulation by depletion of superoxide dismutases with age-dependent impairment in the nervous system and muscles of Drosophila adults. Biogerontol. 2015, 16, 485–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, M.; Kurihara, M.; Kinoshita, S.; Awane, R.; Sato, T.; Ohkawa, Y.; Inoue, Y.H. Anti-tumour effects of antimicrobial peptides, components of the innate immune system, against haematopoietic tumours in Drosophila mxc mutants. Dis. Model Mech. 2019, 12, dmm037721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Q. Role of Nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Ann. Rev. Pharmacol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fusetto, R.; Denecke, S.; Perry, T.; O’Hair, R.A.J.; Batterham, P. Partitioning the roles of CYP6G1 and gut microbes in the metabolism of the insecticide imidacloprid in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano, D.; Kwak, C.J.; Fujii, K.; Ikemura, K.; Satake, A.; Ohkita, M.; Takaoka, M.; Ono, Y.; Nakai, M.; Tomimori, N.; Kiso, Y.; Matsumura, Y. Sesamin metabolites induce an endothelial nitric oxide-dependent vasorelaxation through their antioxidative property-independent mechanisms: possible involvement of the metabolites in the antihypertensive effect of sesamin. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2006, 318, 328–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuruoka, N.; Kidokoro, A.; Matsumoto, I.; Abe, K.; Kiso, Y. Modulating effect of sesamin, a functional lignan in sesame seeds, on the transcription levels of lipid- and alcohol-metabolizing enzymes in rat liver: A DNA microarray study. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2005, 69, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartenstein, V.; Tepass, U.; Gruszynski-Defeo, E. Embryonic development of the stomatogastric nervous system in Drosophila. J. Comp. Neurol. 1994, 350, 367–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiess, R.; Schoofs, A.; Heinzel, H.-G. Anatomy of the stomatogastric nervous system associated with the foregut in Drosophila melanogaster and Calliphora vicina third instar larvae. J. Morphol. 2008, 269, 272–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cognigni, P.; Bailey, A.P.; Miguel-Aliaga, I. Enteric neurons and systemic signals couple nutritional and reproductive status with intestinal homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2011, 13, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yasuda, K.; Ikushiro, S.; Kamakura, M.; Ohta, M.; Sakaki, T. Metabolism of sesamin by cytochrome P450 in human liver microsomes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2010, 38, 2117–2123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardridge, W.M. Blood-brain barrier drug targeting: the future of brain drug development. Mol. Interv. 2003, 3, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hindle, S.J.; Bainton, R.J. Barrier mechanisms in the Drosophila blood-brain barrier. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014, 8, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ullian, E.M.; Sapperstein, S.K.; Christopherson, K.S.; Barres, B.A. Control of synapse number by glia. Science 2001, 291, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Constantinescu, C.S.; Tani, M.; Ransohoff, R.M.; Wysocka, M.; Hilliard, B.; Fujioka, T.; Murphy, S.; Tighe, P.J.; Das Sarma, J.; Trinchieri, G.; Rostami, A. Astrocytes as antigen-presenting cells: Expression of IL-12/IL-23. J. Neurochem. 2005, 95, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgar, J.M.; Garbern, J. The myelinated axon is dependent on the myelinating cell for support and maintenance: Molecules involved. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004, 76, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edenfeld, G.; Stork, T.; Klämbt, C. Neuron-glia interaction in the insect nervous system. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2005, 15, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, Q.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Smith, W.W.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Z. Activation of Nrf2 in astrocytes suppressed PD-Like phenotypes via antioxidant and autophagy pathways in rat and Drosophila models. Cells 2021, 10, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungvari, Z.; Orosz, Z.; Labinskyy, N.; Rivera, A.; Xiangmin, Z.; Smith, K.; Csiszar, A. Increased mitochondrial H2O2 production promotes endothelial NF-κB activation in aged rat arteries. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2007, 293, H37–H47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liddelow, S.A.; Guttenplan, K.A.; Clarke, L.E.; Bennett, F.C.; Bohlen, C.J.; Schirmer, L.; Bennett, M.L.; Münch, A.E.; Chung, W.-S.; Peterson, T.C.; Wilton, D.K.; Frouin, A.; Napier, B.A.; Panicker, N.; Kumar, M.; Buckwalter, M.S.; Rowitch, D.H.; Dawson, V.L.; Dawson, T.M.; … Barres, B.A. Neurotoxic reactive astrocytes are induced by activated microglia. Nature 2017, 541, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakano-Kobayashi, A.; Canela, A.; Yoshihara, T.; Hagiwara, M. Astrocyte-targeting therapy rescues cognitive impairment caused by neuroinflammation via the Nrf2 pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2023, 120, e2303809120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joußen, N.; Heckel, D.G.; Haas, M.; Schuphan, I.; Schmidt, B. Metabolism of imidacloprid and DDT by P450 CYP6G1 expressed in cell cultures of Nicotiana tabacum suggests detoxification of these insecticides in Cyp6g1-overexpressing strains of Drosophila melanogaster, leading to resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daborn, P.; Boundy, S.; Yen, J.; Pittendrigh, B.; French-Constant, R. DDT resistance in Drosophila correlates with Cyp6g1 over-expression and confers cross-resistance to the neonicotinoid imidacloprid. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2001, 266, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pedra, J.H.F.; McIntyre, L.M.; Scharf, M.E.; Pittendrigh, B.R. Genome-wide transcription profile of field- and laboratory- selected dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT)-resistant Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004, 101, 7034–7039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amichot, M.; Tarès, S.; Brun-Barale, A.; Arthaud, L.; Bride, J.M.; Bergé, J.B. Point mutations associated with insecticide resistance in the Drosophila cytochrome P450 Cyp6a2 enable DDT metabolism. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004, 271, 1250–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura-Kuroda, J.; Komuta, Y.; Kuroda, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Kawano, H. Nicotine-Like Effects of the neonicotinoid insecticides acetamiprid and imidacloprid on cerebellar neurons from neonatal rats. PLOS ONE 2012, 7, e32432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cocco, P.; Blair, A.; Congia, P.; Saba, G.; Flore, C.; Ecca, M.R.; Palmas, C. Proportional mortality of dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT) workers: A preliminary report. Arch. Environ. Health 1997, 52, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, J.R.; Roy, A.; Shalat, S.L.; von Stein, R.T.; Hossain, M.M.; Buckley, B.; Gearing, M.; Levey, A.I.; German, D.C. Elevated serum pesticide levels and risk for Alzheimer disease. JAMA Neurol. 2014, 71, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).