1. Introduction

Phytopathogenic fungi are causal agents of plant diseases and represent probably the most diverse group of ecologically and economically relevant threats to plants [

1]. Depending on the species, they parasitize almost all parts of the plant, especially when they find themselves in favorable conditions for development. Chemical or biological fungicides are used to control pathogenic fungi which can cause enormous losses in agricultural products. Fungicides are widely used, highly regulated, legitimate and useful tools that can provide significant benefits to agriculture. They can be effective in protecting crops, but at the same time can also have negative impacts on the environment (soil, water and air contamination) because many of them are organic pollutants [

2]. To maximize fungicide benefits we need to use them safely and efficiently; misuse can cause negative ecological effects.

Despite the wide range of commercial fungicide products on the market, there is a clear need for new and innovative fungicides, due to the development of resistant fungal strains to fungicide active ingredients, regulatory limitations, increasing customer expectations, new diseases and their spread, and new environmental protection policies. The introduction of nanotechnology into agriculture can improve crop production by developing nano fertilizers and nano treatments for plant diseases [

3,

4], however, there is not enough data in the literature on the efficacy and environmental impact of nano agrochemicals under field conditions [

5].

Nowadays, a considerable number of phytochemical companies offer numerous and different classes of fungicides, where copper-based fungicides play an important role due to their antifungal and antibacterial effects [

6]. The major benefits of copper-based compounds are the relatively high toxicity to plant pathogens, low cost, and low mammalian toxicity of the Cu compounds as well as their chemical stability and prolonged residual effects [

7]. Copper is an essential micronutrient for plants and is an important component of fungicide and bactericide formulations on a global scale. Copper fungicides belong to the group of few fungicides that can be used in organic farming and still play an almost inevitable role in organic production, sustainable use of pesticides, and integrated pest management [

8]. Copper compounds are protectant fungicides, which remain on the surface of the plant and are only effective before the pathogens infect the plant. They create a protective barrier on the surface of the plant, inhibiting the development of pathogens before penetrating the tissue. Copper ions interact with biochemical pathways in the pathogen in a non-specific manner, affecting many biochemical steps. Foliar application of copper fungicides enables the contact of copper ions with germinating spores, creating enzyme systems that cause metabolic collapse and prevent further development of fungal cells [

9]. The successful use of copper-containing agents for the control of phytopathogenic plant diseases dates back more than 100 years, which can result in the accumulation of copper in the soil and negative ecological effects. Although copper is a very important nutrient for living cells, as it is an integral part of many metalloenzymes, such as cytochrome c oxidase [

10], it is known that it is phytotoxic at higher concentrations. In addition to phytotoxicity, the disadvantages are the development of copper-resistant strains, soil accumulation and negative effects on soil biota as well as food quality parameters and regulatory pressure in agriculture worldwide, high concentrations of copper salts in preparations, instability in field conditions and solubility in water [

11]. To overcome the mentioned disadvantages, it is necessary to apply a new approach to the production of copper fungicides, such as encapsulation. Encapsulation is an advanced technology by which solids, liquids, or gases may be loaded into a carrier matrix (usually biopolymeric microparticles within micro- or nano-scale) and allows controlled release. Microparticles loaded with an active substance (microparticle formulation) increase the stability of encapsulated active substance and reduce the amount required for application, but the most important role is the possibility of targeted and controlled release.

Numerous studies have pointed out that microparticles formed from sodium alginate (abbreviation ALG) serve as valuable materials for encapsulating agents for various applications. Alginate is a linear polysaccharide that easily forms a gel in the presence of multivalent cations under mild conditions due to the presence of alternating blocks of β-D-mannuronic acid (M units) and α-L-guluronic (G units) linearly linked by 1,4-glycosidic linkages [

12]. The addition of divalent or trivalent cations to an aqueous solution of alginate causes immediate cross-linking and formation of an alginate hydrogel. The ability of alginate gel formation is widely used both in academia and industry for several applications. The encapsulation of bioactive components in microparticles of alginate is a valuable tool in agriculture, especially in the nutrition and protection of plants [

13,

14].

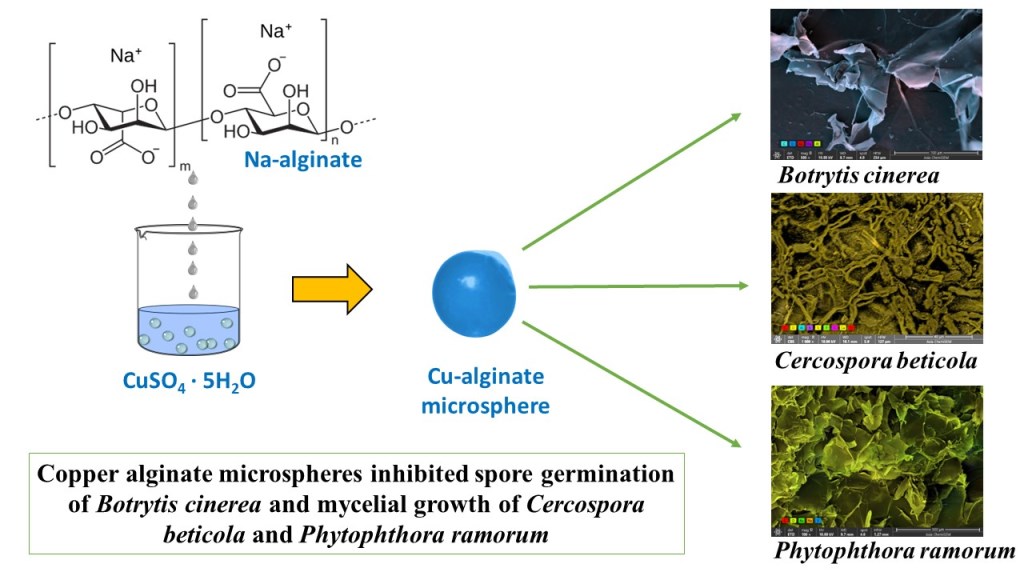

In this work, copper alginate microspheres (abbreviation ALG/Cu) were prepared by alginate ionic gelation and their potential as an ecological fungicide was evaluated. A preliminary set of experiments was performed to study the antifungal effect on selected phytopathogenic fungi (Botrytis cinerea and Cerospora beticola Sacc.) and the oomycete (fungus-like microorganism) Phytophthora ramorum.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Low viscosity sodium alginate (CAS Number: 9005-38-3; Brookfield viscosity 4 - 12 cps (1% in H2O at 25°C) purchased from Sigma Aldrich (USA) and copper sulfate pentahydrate (CAS Number: 7758-99-8) purchased from Gram-Mol d.o.o. (Croatia) were used for microsphere preparation. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and used as received without further purification.

2.1.1. Copper alginate Microsphere Preparation

Copper alginate microspheres (ALG/Cu) were prepared by the ionic gelation as was previously described [

13]. 100 mL of sodium alginate solution (1.5%) was dropped into an equal volume of copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate solution (2, 3 or 4%) through a size 120 μm nozzle at a vibration frequency of 2000 Hz and a pressure of 555 mbar (Encapsulator Büchi-B390, BÜCHI Labortechnik AG, Switzerland). During preparation, the emerging microspheres (abbreviated as Sample 1, Sample 2 and Sample 3 prepared at different initial Cu

2+ concentrations

cCu = 8, 12 or 16 mmol dm

-3, respectively) were mixed on a magnetic stirrer (IKA topolino, USA). Microspheres were formed in the cross-linking solution under mechanical stirring (MSH-300, Biosan; MM-540, Tehtnica, Železniki, Slovenia; Hei-Tec, Heidolph, Germany) for about 30 minutes to harden further, then filtered through a single-layer muslin and washed 3x with distilled water to wash away excess CuSO

4 x 5H

2O and stored at 4°C until further studies.

2.1.2. Preparation of Pathogens

The effect of copper alginate microspheres was assessed on three pathogens: Botrytis cinerea, Cercospora beticola and Phytophthora ramorum. Isolates, BC/7/19 (B. cinerea), CB/16/19 (C. beticola), PR/1/18 (P. ramorum), were obtained from the mycological collection of the Centre for Plant Protection (CAAF, Zagreb). For each isolate, separate plates were inoculated with a plug of mycelia cut from actively growing cultures. B. cinerea and C. beticola were inoculated on PDA (Potato dextrose agar, Biolife) while for P. ramorum carrot-pieces agar was used (CPA - 50 g of cut carrot root pieces and 15 g of agar (Select Agar, Sigma-Aldrich). Plates were incubated in separate growth chambers at 20°C (B. cinerea, C. beticola) and 15°C (P. ramorum) for seven to ten days. Prepared isolates were used further in the experiment.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy Coupled with Attenuated Total Reflectance (FTIR-ATR)

Samples were analyzed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) coupled with Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) recording technique. FTIR-ATR spectra of the samples were acquired using the Cary 660 FTIR spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) and the Golden Gate single-reflection diamond ATR accessory (Specac). Spectra were recorded in the mid-infrared region (spectral range: 4000 – 400 cm-1) and transmission mode. Before the spectral analysis, samples were pulverized into finer homogenates with a porcelain mortar. Approximately 10 mg of the sample was pressured on a diamond ATR plate using a self-leveling sapphire anvil to obtain the FTIR-ATR spectrum of a thin uniform layer of each sample. Two replicate spectra (32 scans/spectrum) of each sample were recorded using different aliquots. Spectra were acquired at a nominal resolution of 4 cm-1 and room temperature (24±2°C). Raw spectral data were stored and pre-analyzed using the Agilent Resolutions Pro version 5.3.0 software package (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA), while further spectral data analysis and processing were carried out using optical spectroscopy software Spectragryph (version 1.2.16.1) and Origin 8.1 (Origin Lab Corporation).

2.2.2. Physicochemical Characterization of Copper Alginate Microspheres

2.2.2.1. Encapsulation Efficiency (EE), Loading Capacity (LC) and Swelling Degree (Sw)

(a) The encapsulation efficiency (EE) was calculated from the initial concentration of copper ions (

ctot) and of the content of copper ions in dry microspheres (

cload) by the method of Xue et al. [

15]. Encapsulation efficiency is expressed as a percentage of total copper (

ctot) and is calculated by the equation:

where c

𝑙𝑜𝑎𝑑 = c

𝑡𝑜𝑡 − 𝑐

𝑓, and 𝑐

𝑓 is the concentration of copper ions in the filtrate.

(b) Copper content or copper loading capacity (LC) in microspheres prepared at different initial copper concentrations was determined by dispersing 4 g of dry microspheres in 25 mL of a mixture of 16.80 g (0.2 mol dm

-3) NaHCO

3 and 17.65 g (0.06 mol dm

-3) Na

3C

6H

5O

7·2H

2O at pH 8. The dispersion was mixed at 400 rpm on a magnetic stirrer (IKA topolino) until all the microspheres were completely dissolved. The resulting solution was filtered through double muslin, and the concentration of copper ions in the filtrate was determined. The loading capacity is expressed as the amount of Cu

2+ in mmol per 1 g of dry microspheres and calculated by the equation:

where cCu is the concentration of copper ions in the sample, V is the volume of the sample, and wc is the weight of the microspheres. The concentration of copper ions in the filtrate was determined by UV-VIS spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-1700, Japan) at λmax = 795 nm.

(c) Samples for swelling degree determination were prepared by dispersion of dry microspheres (0.1 g) in a glass vial containing 10 mL of deionized water and allowed to swell at room temperature for 3 hours. The wet weight of the swollen microspheres was determined by blotting them with filter paper to remove moisture adhering to the surface, immediately followed by weighing [

16]. The swelling degree (S

w/%) was calculated using the equation:

where

wt is the weight of the swollen microspheres, and

w0 is their initial weight. The measurements were replicated 3 times.

2.2.2.2. In Vitro Release of Cu2+ Ions from Copper Alginate Microspheres

In vitro, the release of Cu

2+ ions from microspheres was studied by dispersing 4 g of microspheres in 200 mL of deionized water and left to stand without stirring during experiments at room temperature. At appropriate time intervals, the dispersion was stirred for 60 s, aliquots were withdrawn and the concentration of Cu

2+ ions was determined by UV/VIS spectrophotometer (λ

max = 795 nm). Measurements were performed in triplicates. Results are presented as the fraction of released copper ions (Cu

2+) using the equation:

where f represents the fraction of released Cu

2+, R

t is the amount of Cu

2+ released at time t and R

tot is the total amount of Cu

2+ in microspheres.

2.2.2.3. Rheological Measurements

The rheological characteristics of microspheres were analyzed through oscillatory rheology. The storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli were determined using a mechanical rheometer (Anton Paar MCR 302, Stuttgart, Germany) with a sandblasted steel plate−plate geometry (PP25/S, Anton Paar, Graz-Austria) and a gap of 2 mm. The instrument was equipped with a true-gap system, and data were collected using RheoCompass software. Sandpaper was attached to the surface of the base plate to prevent the microspheres from slipping during the measurements. Sample temperature was regulated using a Peltier temperature control located at the base of the geometry, along with a Peltier-controlled hood (H-PTD 200). During the experiment, a sample was positioned on the rheometer’s base plate, and the plate was adjusted using the true-gap function of the software. After allowing 2 minutes at 25 °C, measurements of G′ and G″ moduli were consistently taken within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). The yield stress was determined by conducting a strain (γ) sweep between 0.01% and 100% at a constant frequency of 5 rad/s. The rheological properties of the sample were found to be strain-independent up to the yield strain. Beyond the yield strain, the rheological behavior became nonlinear. Subsequent frequency sweeps (0.1–100 rad/s) were carried out at 25 °C, maintaining a strain value of 0.1% within the LVR to explore the time-dependent deformation behavior of the sample.

2.2.3. Microscopic Observations

The morphology of copper alginate microspheres was analyzed by scanning electron microscope (SEM) (FE-SEM, model JSM-7000F, Jeol Ltd., Japan)) and atomic force microscope (AFM) (Nanosurf CoreAFM, Nanosurf AG, Switzerland)).

Samples for SEM analyses were placed on high-conductive graphite tape. FE-SEM was connected to an EDS/INCA 350 (energy dispersive X-ray analyzer) manufactured by Oxford Instruments Ltd. (UK).

AFM images were taken using Nanosurf CoreAFM under ambient conditions. The non-contact mode was used for acquisition with a setpoint of 55 % with Tap300Al-G tip with a nominal spring constant of 40 N/m, a tip radius less than 10 nm and a nominal resonant frequency of 300 kHz on a 10 × 10 μm surface with 0.78 s acquisition time. Images were processed with Nanosurf software.

Surface roughness (Rq) is obtained by squaring each value of Z (height) in the sample and rooting the arithmetic mean of these values. Thus, the roughness is calculated as the arithmetic average of the absolute heights in the entire height line of the sample, so the presence of a smaller number of larger deviations can affect the roughness. Surface roughness was calculated on three different locations of the samples for better accuracy. Images were processed using the

Gwyddion program [

17].

Fungal spore morphology was analyzed by optical microscope (OM) (Leica MZ16a stereo microscope, Leica Microsystems Ltd., Switzerland)) and SEM. Spores of B. cinerea, C. beticola and P. ramorum were dispersed in distilled water before observation under OM and dried before examination under SEM. The average diameter of spores was determined by OM using Olympus Soft Imaging Solutions GmbH (version E_LCmicro_09Okt2009).

2.2.4. The Electrostatic Charge and Size of Fungal Spores Suspended in Water and Copper Ions Solutions

A photon correlation spectrophotometer equipped with a 532 nm green laser (Zetasizer Nano ZS, Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK) was used for the determination of the size distribution and zeta potential of fungal spores suspended in water or copper ions solutions. The concentration of copper ions in suspension was 0, 8, 12, or 16 mmol dm-3.

The zeta potential (ζ/mV) was calculated from the electrophoretic mobility using a Smoluchowski approximation (f(κa) = 1.5). The hydrodynamic diameter (d/nm) was determined from the peak maximum of the volume size function. The hydrodynamic radius values were reported as an average value of 10 measurements, while the zeta potential values were reported as an average of 5 independent measurements. The data processing was carried out using Zetasizer Software 7.13 (Malvern Instruments LTD, Malvern, Worcestershire, UK). All measurements were made at room temperature.

2.2.5. Testing the Antifungal Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres

2.2.5.1. Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres on B. cinerea Conidia Germination

1 g of copper alginate microspheres (Sample 1, Sample 2 or Sample 3) was suspended in a 10 mL Falcon tube filled with sterile water. Conidia were scraped from sporulating colonies of B. cinerea isolates with a sterile toothpick and transferred to a prepared Falcon tube. 1 mL of suspension was evenly poured onto PDA plates in three replicates and placed in a growth chamber at 20°C and 60% relative humidity for incubation. PDA plates with 5% of the commercial fungicide Neoram® (copper oxychloride 37.5% wettable granules) and distilled water were used as a reference for comparison. Suspension with distilled water was used as an untreated control.

Germination and elongation of the germ tube (30 germ tubes were measured for each sample) have been monitored and measured with an Olympus BX53 optical microscope 18 h after incubation. Measurements were performed using the CellSens Dimension program (Olympus). Analysis of variance (ANOVA, Microsoft Excel) compared the average values of the length of the germ tubes between the control and those incubated with copper alginate samples or commercial fungicide.

2.2.5.2. Antifungal Effect of Alginate Copper Microspheres on Mycelium Growth of C. beticola

A suspension of copper alginate microspheres and C. beticola conidia was prepared as described for B. cinerea. 1 mL of a suspension was evenly poured onto PDA plates in three replicates and placed in a growth chamber at 28°C and 80% relative humidity for incubation.

After 7 days of incubation, the number of developed colonies was read using a millimeter grid divided into 4 squares. The relative percentage of developed colonies was calculated as the relationship between the number of colonies on the control and those with copper alginate microspheres.

2.2.5.3. Antifungal Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres on Infestations of Rhododendron sp. Leaves by P. ramorum

10 g of copper alginate microspheres were placed in Petri dishes with a diameter of 120 mm. 100 mL of spring water, two pieces of mycelial disc of P. ramorum and two leaves of Rhododendron sp. were added to each Petri dish. The control Petri dishes contained 100 mL of spring water, two mycelial discs of P. ramorum and two leaves of Rhododendron sp. The experiment was set in two replicates at room temperature to encourage the formation of sporangia. Visual observations and results were read after two weeks. The presence of sporangia and zoospores in the water and on the Rhododendron leaves was examined with an Olympus BX53 microscope. Symptoms of leaves infection were also recorded by visual observation.

The relative percentage of developed colonies (inhibition percentage) was calculated based on the ratio between control and copper alginate microspheres. The percentage of inhibition (I %) was calculated according to Abbott [

18].

2.2.5.4. Data Analysis

All experiments were repeated three times, and the data was presented with mean values and standard deviations. Data corresponding to a normal distribution were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (One-way ANOVA).

3. Results

The results are presented and discussed in two sections. In the first section, the important copper alginate microsphere properties/performance are analyzed. In the second part, the potential of antifungal activity of copper alginate microspheres against pathogens (B. cinerea, C. beticola and P. ramorum) is evaluated.

3.1. Copper Alginate Microsphere Properties/Performance

3.1.1. Identification of Interactions between Microsphere Constituents

The functional groups characterizing the bulk chemistry of the copper alginate microspheres were identified by FTIR. The spectra of sodium alginate as well as copper alginate microspheres prepared at lower concentrations of copper ions were described previously [

19]. Characteristics of sodium alginate spectrum is a strong broadband assigned to the stretching modes of hydroxyl groups (–OH) around 3300 cm

-1, pyranoid ring C–H stretching at 2925 cm

-1, very sharp stretching at 1595 cm

-1 and medium sharp stretching at 1405 cm

-1 corresponding to vibrations of asymmetric and symmetric carboxylate groups (COO

-), weak broad stretching vibration at 1295 cm

-1 assigned to C–O group. Bands situated around 1026 cm

-1 are attributed to the ALG saccharide structure. The characteristic peaks of copper sulfate pentahydrate are at 3200, 1667, 1067 and 860 cm

-1. A broad stretching frequency at 3200 cm

-1 and a band of medium intensity at 1667 cm

-1 represent the bending modes of the hydroxyl group, while frequencies at 1067 and 860 cm

-1 are characteristic bands of inorganic sulfates ((SO

4)

2- stretching region [

20]. The comparison between spectra of sodium alginate and copper alginate showed the most significant changes in the alginate functional groups region: hydroxyl (OH), ether (COC) and carboxylate (COO

-). The intensities of the main alginate peaks in the spectrum of copper alginate microspheres are reduced and shifted towards lower or slightly higher wave numbers. Shifting of the alginate broad band around 3300 cm

-1 indicates copper ions’ interaction with hydroxyl groups while shifting the peaks of carboxylate stretching vibrations arose from the copper ions binding to oxygen atoms from negatively charged and uncharged carboxyl groups [

21]. In comparison with calcium ions [

22], the band assigned to the asymmetric elongation vibration of COO

- was more downshifted with copper ions, thus confirming that the alginate chains interacted more effectively with copper(II) ions [

19]. The affinity of Cu

2+ to alginate chains is ten times higher than that of Ca

2+ [

23].

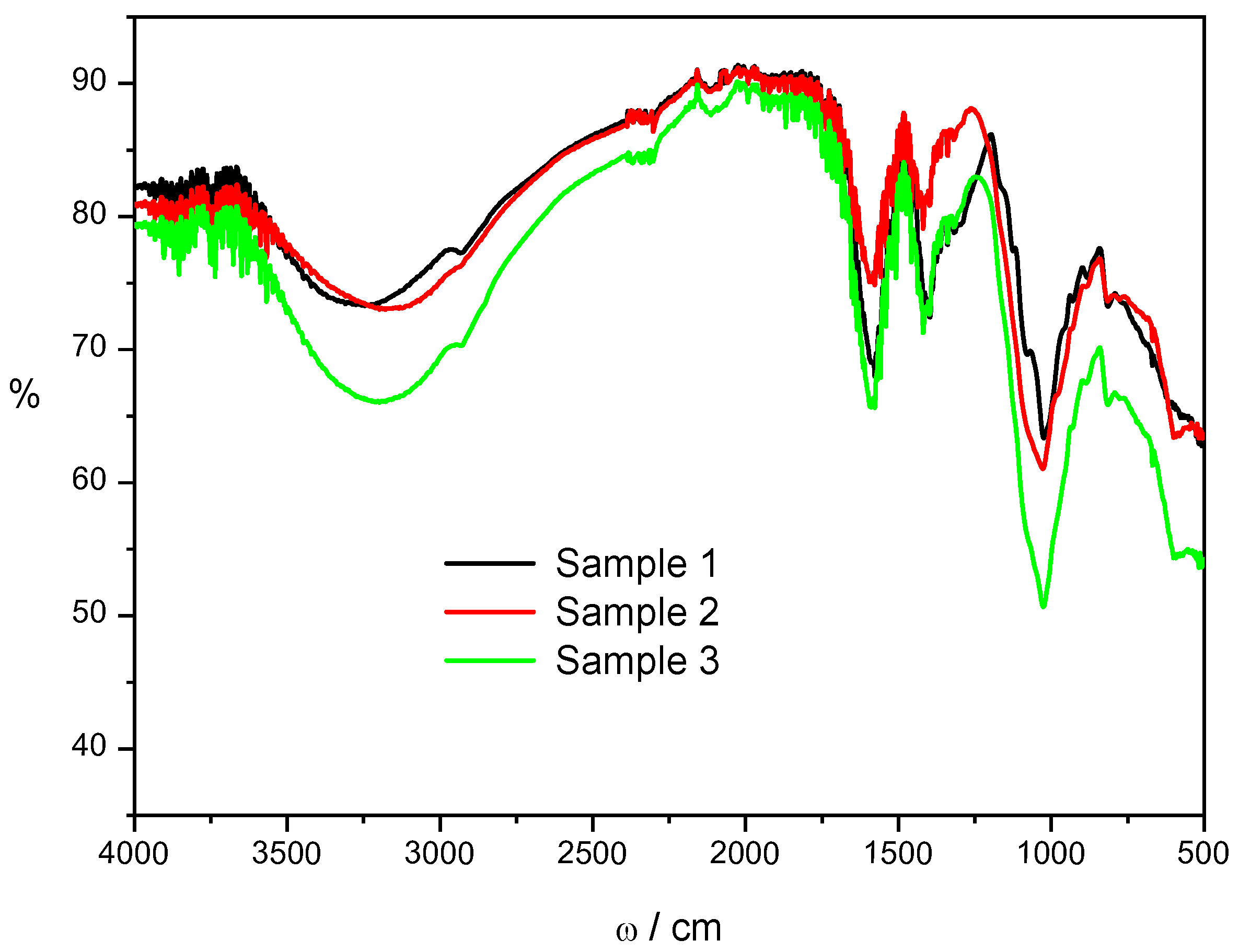

Figure 1 shows the effect of copper ion concentrations on the spectrum of copper alginate. There are no significant changes in the intensity of the absorption band around 3300 cm

-1 between Samples 1 and 2, however, Sample 3 spectrum shows broadening and more intense stretching vibrations suggesting enhanced intermolecular hydrogen bonds.

With an increase in the concentration of copper ions, the intensities of asymmetric and symmetric carboxylate stretching vibrations follow the order of Sample 2 < Sample 1 < Sample 3 indicating a change in the intensity of interaction between alginate carboxylate groups and copper ions. Small changes in the intensity of carboxylate stretching vibrations, as well as a certain irregularity of changes about the increase in the concentration of copper ions, indicate a complex change in the cross-linking of alginate chains. During gelation of sodium alginate, copper cations interact with the functional groups forming a cross-linked network of alginate chains. Unlike calcium ions, which crosslink alginate chains only electrostatically, crosslinking with copper ions occurs mainly by coordination of covalent bonds and partially by ionic bonds [

24].

The weak bands at 1080 cm

-1 and strong peaks at 1026 cm

-1 are assigned to the C=O and C-C bonds of guluronic and mannuronic units, respectively [

25]. It can be seen that the intensity of the strong peak at 1026 cm

-1 assigned to mannuronic units increases significantly with the amount of copper cations loaded in the microspheres. Unlike calcium-induced gelation of alginate, which is mainly based on cross-linking between ions and uronates, copper ions bind to mannuronic and guluronic alginate units [

26]. The weak band at 1080 cm

-1 assigned to guluronic units can be seen only for Sample 1 and disappeared at higher concentrations of copper ions. Papageorgiou et al. [

27] proposed in the metal-alginate complexes a “pseudo-bridged” unidentate coordination with intermolecular hydrogen bonds in polyguluronic regions and the bidentate bridging coordination in the polymannuronic region.

Changes in spectra clearly show small structural differences in microspheres prepared at different concentrations of copper ions. Similarly was observed by Omidian et al. [

28] who suggested that bands concerning carboxylate groups can be used to follow structural changes of different alginate gels.

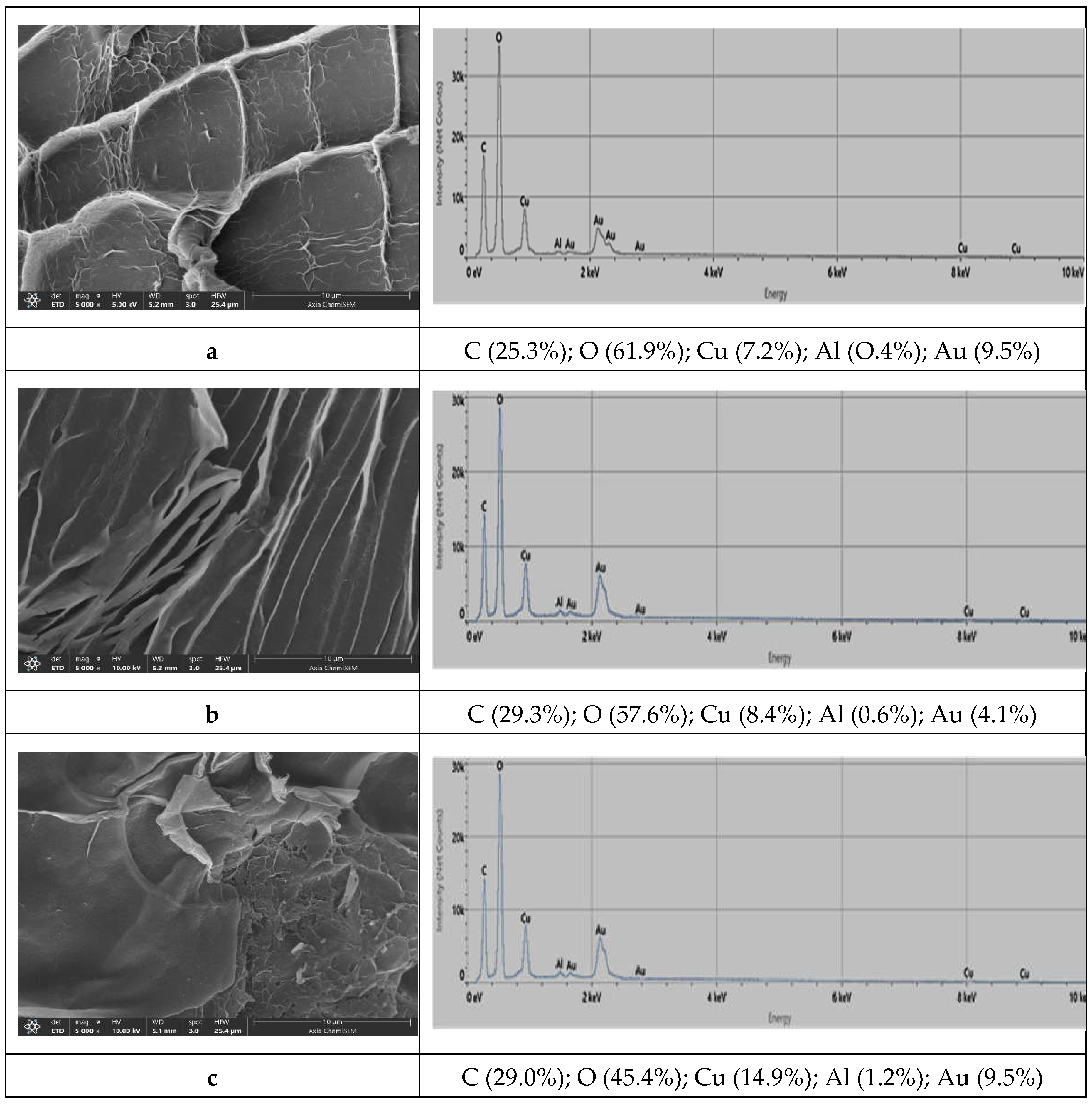

3.1.2. Morphology of Copper Alginate Microspheres

Prepared microspheres were almost spherical and colored blue due to the presence of copper ions. After drying to a constant mass, the shape and size of the microspheres changed significantly, they became irregular and smaller. The surface morphology of microspheres prepared at different initial concentrations of copper ions is presented in

Figure 2. The surfaces became wrinkled with the appearance of more or less intertwined threads due to the loss of water and moisture associated with the stress relaxation processes of biopolymers [

29]. Different morphologies seen in

Figure 2 are a reflection of structural differences in the gel network. The smoothest surface of Sample 3 points to weaker intermolecular forces with a fewer number of crosslinking points between two alginate molecules [

30]. The crosslinking density influences how much water the gel can absorb. Lower crosslinking density generally leads to higher swelling [

31]. In the investigated concentration range of copper ions, S

w increased from 35, 60 to 90% indicating a decrease in crosslinking density from Sample 1 to 3.

EDS spectral analysis of the surface layers (the electron probe can penetrate to a depth of about 1 µm) is shown in

Figure 2 on the right side next to the corresponding image of microspheres. The major elements are oxygen, carbon, and copper. The amount of copper on the surface increases (from 7.2, 8.4 to 14.3%) following the increase in the amount of copper ions used during the preparation of microspheres. The samples do not contain a sodium atom due to complete ion exchange with copper ions during the cross-linking process. Detected amounts of aluminum and gold are probably residues of compounds used during the sample preparation for analysis.

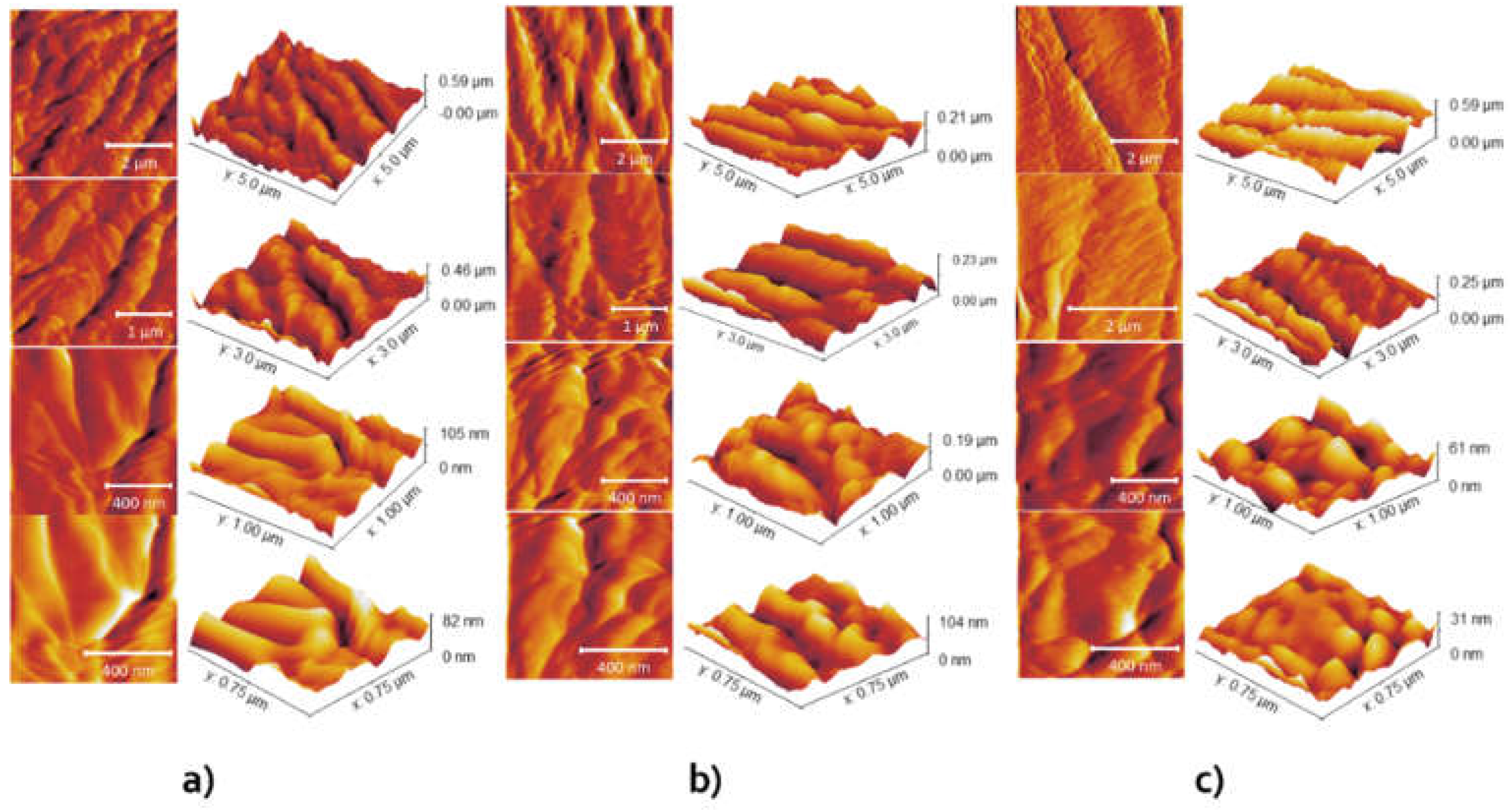

AFM imaging was done at a few different regions of each microsphere to ensure the accuracy of the obtained results. In

Figure 3, the topography of each sample can be seen, along with a 3D topography view with a corresponding Z-axis scale (i.e., height). As can be seen, the surfaces consist of stacked granular particles. By increasing the content of copper ions in the microspheres, the grains become smaller, but the overall surface becomes less rough. The grain height was between 30 and 100 nm, which could be seen in the smallest images (lowest row in

Figure 3). As can be seen in

Figure 3, the grains at Sample 1 were the largest and elongated, forming a rougher surface. Determined surface roughness values are presented in

Table 1. The values are observed by calculating the average of five roughness values obtained at different locations on the sample.

An important step in the foliar application of copper-based fungicides is adhesion to the plant surface due to the possible blowing of microspheres from the leaves by wind or rain. Surface roughness is an important property of microspheres due to their ability to adhere to other substrates [

32]. It was shown that higher surface roughness reduces adhesion in real contact [

33], which indicates some advantages of Sample 3 over Sample 1 or Sample 2 (

Table 1). The smallest roughness parameters of Sample 3 indicated a better adhesion ability in comparison with other samples. Adhesion enables the contact of copper ions with germinating spores and creates enzyme systems that prevent the further development of cells and mycelium [

34].

3.1.3. Rheological Properties of Copper Alginate Microspheres

The rheological properties of microspheres correlate with their microstructures providing useful information for maintaining their stability during processing and application. The results of the dynamic oscillation test gave information concerning the influence of copper ion concentrations on the structure and mechanical properties.

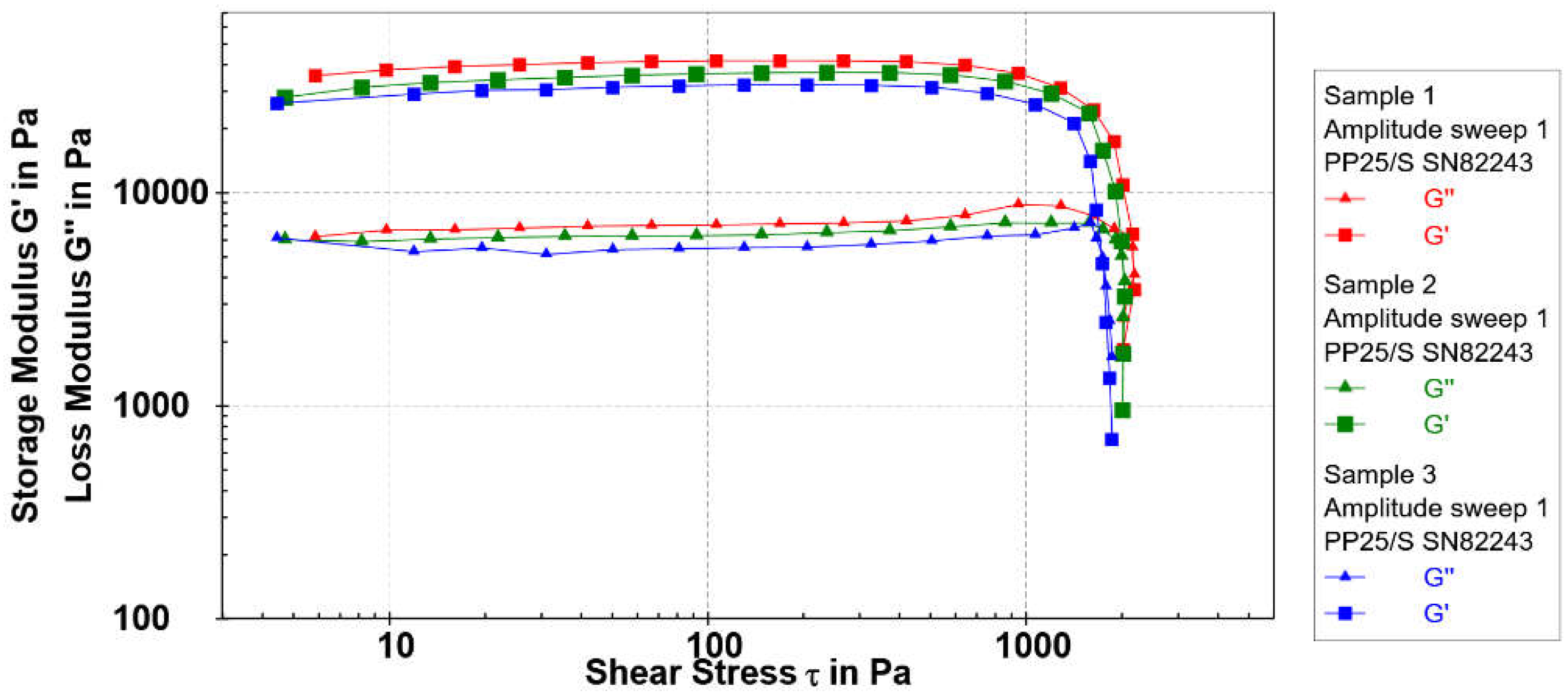

3.1.3.1. Amplitude Sweep

The viscoelastic properties of the microspheres were described using oscillatory rheology. The storage modulus G′ (Pa) represents the elastic segment of viscoelastic behavior, characterizing the solid-state properties of the sample. Typically, the elastic component (G′) predominates over the loss modulus or viscous component (G″) under low applied shear, reaching a plateau within the linear viscoelastic region (LVR). The linear viscoelastic region encompasses the range where applied stress minimally influences the 3D structure of the material. The point at which the linear relationship between stress and strain is disrupted is known as the yield point, signaling a change in the material’s structure. During the amplitude test, the frequency is held constant and the shear strain is varied. Strain (γ) sweep tests were conducted in the strain range from γ = 0.01 to 100% at an angular frequency ω = 5 rad s

−1 at 25 °C. The G′ and G″ values remained nearly unaffected by the applied strain up to 0.8%. Amplitude sweep results are depicted in

Figure 4.

The rheological behavior of the microspheres prepared with different Cu

2+ concentrations exhibited similar viscoelastic properties. As the concentration of Cu

2+ in microspheres increased the elastic modulus decreased in the order Sample 1 > Sample 2 > Sample 3 (

Table 2). Following the decrease of the elastic modulus, the shear stress has also decreased in the same order. Yield point values of Samples 1, 2 and 3 were 1334 Pa, 1249 Pa and 1173 Pa, respectively. As the yield stress values decreased the yield strain values increased in the same order from 3.5% to 5.2 %. Data obtained indicate a somewhat softer but still well-organized structure of Sample 3. This is particularly noticeable in the assessment of the loss factor.

The quantity loss factor, tan(δ) = G″/G′, determines the relative elasticity of viscoelastic materials. The material with a value of tan(δ) lower than 1 is in the solid state. The material with a value of tan(δ) = 0.1 belongs to a stiff one and is indicative of well-ordered systems. The loss factor values determined in the examined cases were 0.17-0.18. The flow transition index represents a measure of the yielding zone, a valley between a yield point and a flow point. The value of the flow transition index is similar for Sample 1 and 2, and somewhat lower for Sample 3.

The storage modulus values, yield point, flow point, and flow transition index follow a decreasing order from Sample 1 > Sample 2 > Sample 3. However, it is noteworthy that despite the variation in Cu2+ concentration, all investigated samples demonstrated high elastic modulus (G’) values in the order of 104 Pa. This suggests the formation of a well-ordered and elastic structure, even at the microspheres prepared at 16 mmol dm-3 Cu2+ concentration.

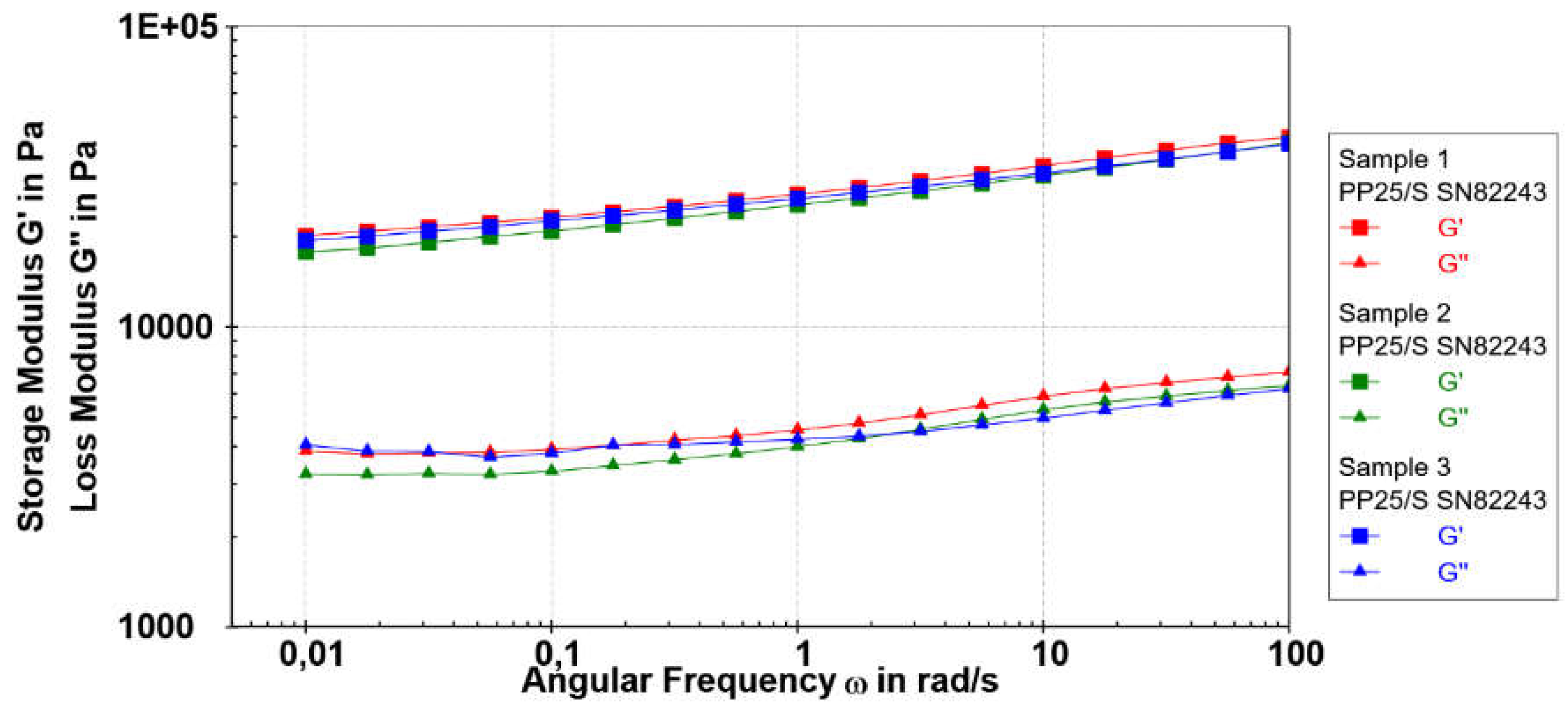

3.1.3.2. Frequency Sweep

Frequency sweep analysis characterizes the time-dependent response of a sample within a non-destructive deformation range, providing insights into the behavior and internal structure of polymers. Conducting frequency sweep studies (ω = 0.1−100 rad/s at 0.2% strain, LVR) on the examined samples at 25 °C revealed that throughout the frequency range, the storage modulus (G′) values consistently exceeded the loss modulus (G″) values (G` > G``). This indicates a prevailing elastic nature rather than a viscous character for the samples, as shown in

Figure 5. The frequency-dependent evolution of G’ and G’‘ for all investigated samples was observed. At higher frequencies, the investigated samples showed higher rigidity reflected in higher G` values. The gradual rise in elastic modulus with frequency suggests the presence of relaxation processes, potentially induced by the release of reversible entrapped entanglements or the opening of intermolecular junctions [

35]. In general, the elastic modulus of alginate polymer depends on the number of cross-links, length, and stiffness of the chains between cross-links [

36]. Since the storage modulus dependence of frequency is very similar for all investigated samples prepared at different Cu

2+ concentrations we assume a similar structural microsphere arrangement, although a slightly lower value of the elastic modulus of Sample 3 indicated a somewhat looser network structure.

It is considered that a low angular frequency (ω) region is considerably sensitive to a polymer network structural change. In the higher frequency range, Samples 1 to 3 exhibited a range of loss factor (tan δ) values from 0.15 to 0.17, while in the low-frequency range, the tan δ values were slightly higher, ranging from 0.18 to 0.21. Notably, only Sample 3, showed a subtle change in tan δ from 0.15 to 0.21 at very low frequencies. Although the structural strength and rigidity of cross-linked polymers are slightly influenced by the Cu2+ concentration, the relative elasticity (tan δ) is well-maintained across the entire frequency range. The frequency sweep measurements showed that the microspheres were stable for a prolonged period independent of the Cu2+ concentration.

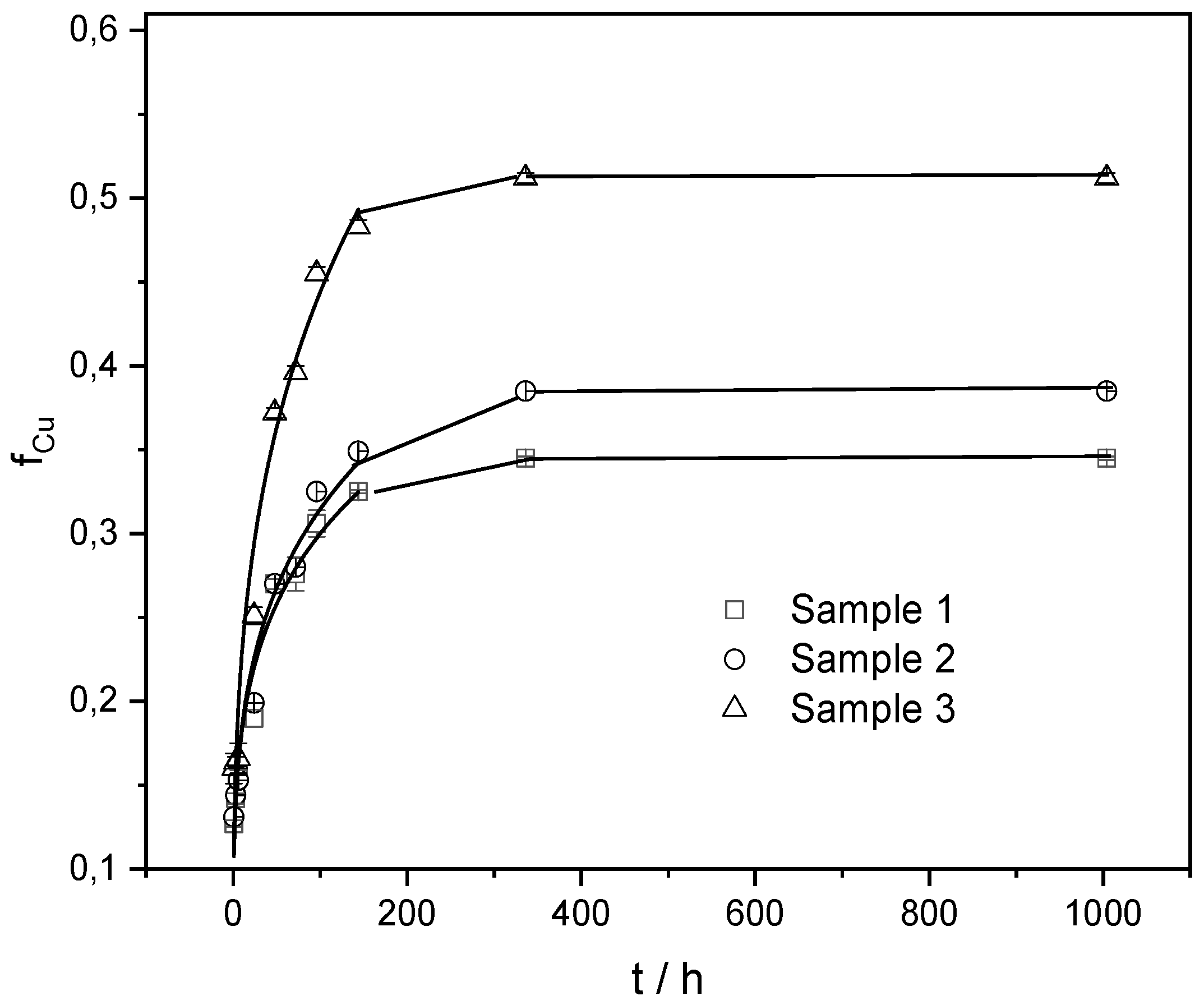

3.1.4. In Vitro Copper Ions Release from Copper Alginate Microspheres

The release of a bioactive component from a hydrophilic microparticle may involve different types of physicochemical processes, including wetting, swelling (penetration of solution into the matrix), polymer stress relaxation (transition from glassy to rubbery state), diffusion through the matrix, disintegration, dissolution, or erosion of the structure, or their combination [

37]. Understanding the mechanism and kinetics of bioactive components released from microspheres is critical for the optimal development of formulations for a specific application. Bearing in mind the main factors (concentration of biopolymer and gelling cation, microsphere preparation technique, chemical composition and geometry of microspheres) that influence the release of bioactive components, [

13,

38] we prepared copper alginate microspheres at a constant concentration of sodium alginate and different concentrations of copper ions. The release profiles of copper ions from all three types of copper alginate microspheres are presented in

Figure 6.

All release profiles are characterized by a rapid initial release followed by a slower release obeying the power law equation. The highest amount of released copper was detected in Sample 3. This may simply be attributed to the fact that microspheres have higher copper loading capacity (LC values ranged from 2.1 to 2.3 to 2.8 mmol for 1.0 g of microsphere prepared with copper concentration from 8, 12 to 16 mmol dm

-3, respectively) as well as the weakest crosslinking density between alginate strands. Results were analyzed using a simple empirical Korsmeyer-Peppas model [

39]

where f

Cu is a fraction of released copper ions,

k is a kinetic constant characteristic of a specific system taking structural and geometrical aspects into account,

n is the release exponent representing the release mechanism, and t is the release time.

Table 3. represents variations of the release constant, exponent

n and correlation coefficient of copper ions released from microspheres prepared at different initial concentrations of Cu

2+.

According to the used model

, n values lower than 0.45 revealed that the process of copper ions release is controlled by diffusion and is closely related to the process of swelling. Thanks to the extremely strong copper-alginate affinity, an incomplete Cu

2+ dissolution profile occurs over a time range longer than 24 h. Because of the hydrophilic nature of copper cross-linked alginate microspheres, processes such as dissolution, diffusion and erosion also play a role in the release of copper ions [

40]. The increase in the release constant

k with the initial concentration of copper cations is related to the differences in the structure of the microspheres, i.e., with the cross-linking density. A higher degree of swelling indicates a lower cross-linking density, which causes a higher rate of copper ions release, and is consistent with previous research [

13]. It can be concluded that Sample 3 not only has a higher copper loading but also releases a larger amount of copper ions at a faster rate.

3.2. Antifungal Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres on B. cinerea C. beticola and P. ramorum

3.2.1. Effects of Copper Ions Addition on B. cinerea, C. beticola and P. ramorum

Botrytis cinerea is a filamentous fungal pathogen that causes gray mold disease [

41]. It is a destructive and ubiquitous plant pathogen and parasitizes a large number of host plants (vegetables, fruits, ornamental flowers) causing severe economic losses in crops before and after harvest. Due to its high genetic variability [

42]

B. cinerea develops resistance to some chemical fungicides [

43].

Cercospora beticola typically infects plants of Amaranthaceae family (mainly sugar beet, spinach and swiss chard) causing Cercospora leaf spot (CLS) disease [

44]. This pathogen is the most destructive foliar beet disease in warm and humid [

45]. CLS can be managed by using fungicides, however, after repeated exposure,

C. beticola becomes resistant to some active ingredients of fungicides [

46].

Phytophthora ramorum is a filamentous, diploid oomycete, belonging to a group of organisms often known as ‘water moulds’. It is an invasive pathogen that can cause extensive damage to more than 150 plant species, including some valuable forest trees [

34]. Depending on the host, symptoms vary from leaf spot, blight, death of twigs, cancer and, finally, the death of a plant [

47]. In coastal California and southern Oregon,

P. ramorum causes sudden oak death, a disease that has killed millions of trees, primarily tanoak and coast live oak [

48]. The most important host of

P. ramorum in Europe is rhododendron.

All three pathogens have developed resistance to important classes of fungicides in recent years. It should be emphasized that copper-based compounds, although used for a long time, can be still effective in pathogen suppression [

49]. Copper ions have a wide range of activity against bacteria, oomycetes and fungi interacting with nucleic acids, interfering with energy transport, disrupting enzyme activity, and affecting the integrity of cell membranes of pathogens. The primary mechanism of the antifungal effect of copper ions is their uptake and physical deterioration of the membrane, which leads to the influx of copper [

50]. Following absorption into the fungus or bacterium, the copper ions will link to various functional groups present in many proteins and disrupt their functions.

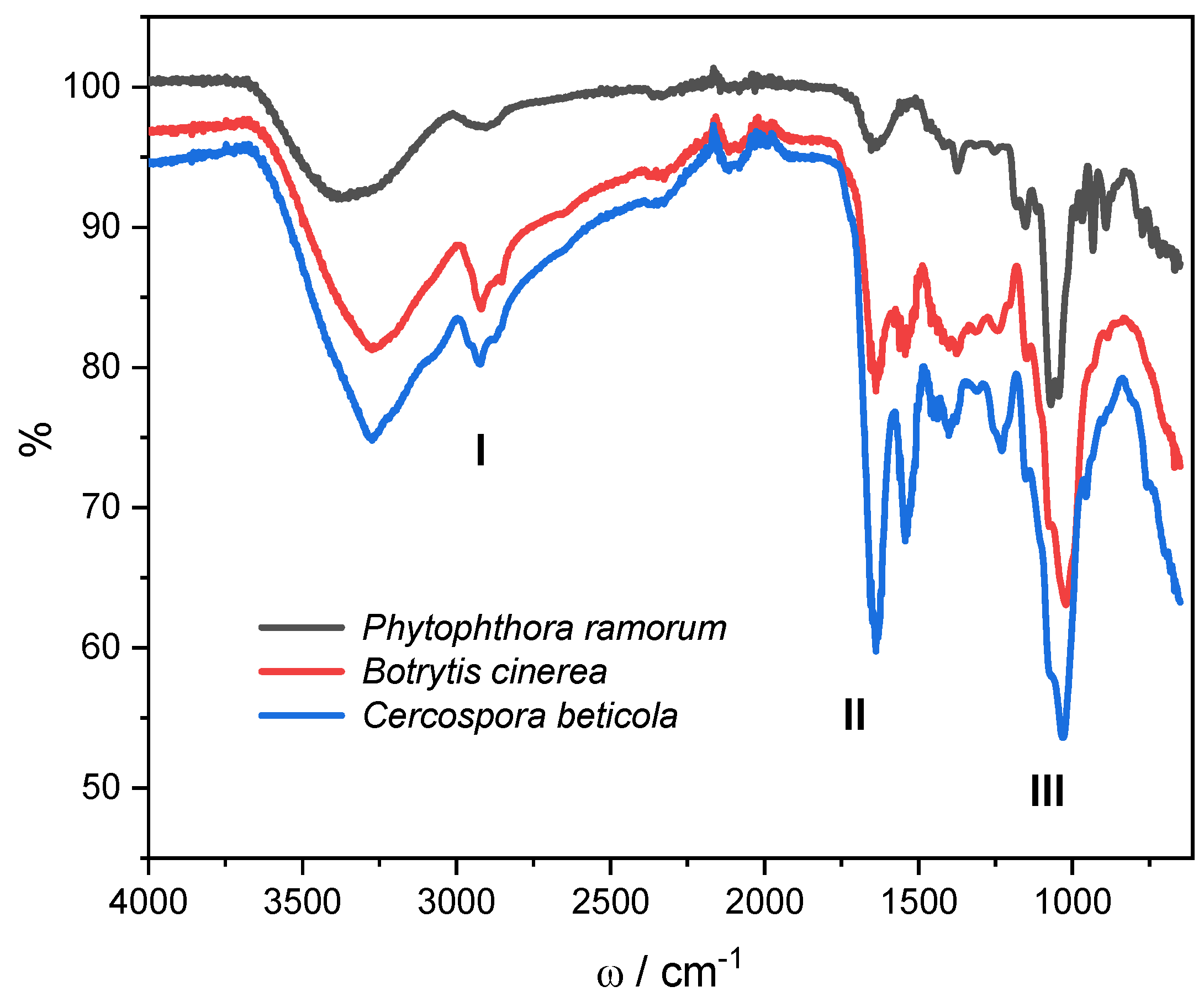

3.2.1.1. Fourier Transformed Infrared (FTIR-ATR) Spectroscopy of B. cinerea, C. beticola and P. ramorum Mycelium

Figure 7 shows a typical fungal spectrum: broad absorption band between 3000 to 2800 cm

-1, characteristic bands for fatty acid, amide I and II (1700-1500 cm

–1), polysaccharides (1200-900 cm

–1) and the range between 700-900 cm

–1 specific for the identification of microorganisms (the fingerprint region). Fungi infrared spectra reveal bands that are unique to particular functional groupings of biological origins as was shown by Mularczyk-Oliwa et al. [

51]. In all spectra, the peak intensities decrease in the order

C. beticola < B. cinerea < P. ramorum with a small shift towards higher or lower wave numbers. Peaks of broad bands appearing between 3000 to 3500 cm

-1 consistent with O-H bond stretching are shifted in the same order; from 3269 to 3275 to 3362 cm

-1. This range might be caused by water molecules in the cytoplasm or extracellular water, such as moisture in the air.

The region between 3000 and 2800 cm

-1 shows the C-H stretching vibrations of CH

3 and CH

2 functional groups in fatty acid chains of various membranes. The spectra of

C. beticola and B. cinerea are similar with peaks at 2926 cm

-1, while the peak of

P. ramorum is shifted to 2905 cm

-1. The stretching vibrations of C=O, C-N, and the bending mode of NH in amide I are shown in the next area, from 1800 to 1500 cm

-1, as are the C-N stretching vibrations and bending mode of NH in amide II [

52]. Sharp stretching and medium sharp stretching at 1640 and 1539 cm

-1 (

C. beticola) and at 1631 and 1540 cm

-1 (

B. cinerea) correspond to protein vibrations as well as vibrations of other fungal constituents [

53]. In this region,

P. ramorum shows only stretching at 1650 cm

-1.

In the region 1500-1200 cm-1, the total absorbance is lower, although several different peaks are visible. This region is a mixed region that exhibited C=O symmetric stretching vibrations of COO- functional groups of amino acid side chains or free fatty acids, CH2 bending mode of lipids and proteins, and P=O asymmetric stretching vibrations in phospholipid head groups.

In the meanwhile, the symmetric stretching vibration of PO

2− groups in nucleic acids and the C-O-C, C-O, and C-O-P stretching vibrations of different oligo and polysaccharides are proven in the area between 1200 and 900 cm

−1 [

54]. The strongest peaks corresponding to chitin vibrations are at 1032 cm

-1 (

C. beticola), 1026 cm

-1 (

B. cinerea) and 1031 cm

-1 (

P. ramorum) [

55]. In the fingerprint region (700-900 cm

-1) [

56]

Cercospora beticola and B. cinerea show similar spectra with lower total absorbance. Spectrum of

P. ramorum mycelium exhibits several peaks corresponding to β-glucans (vibrations at 891 and 773 cm

-1) [

57].

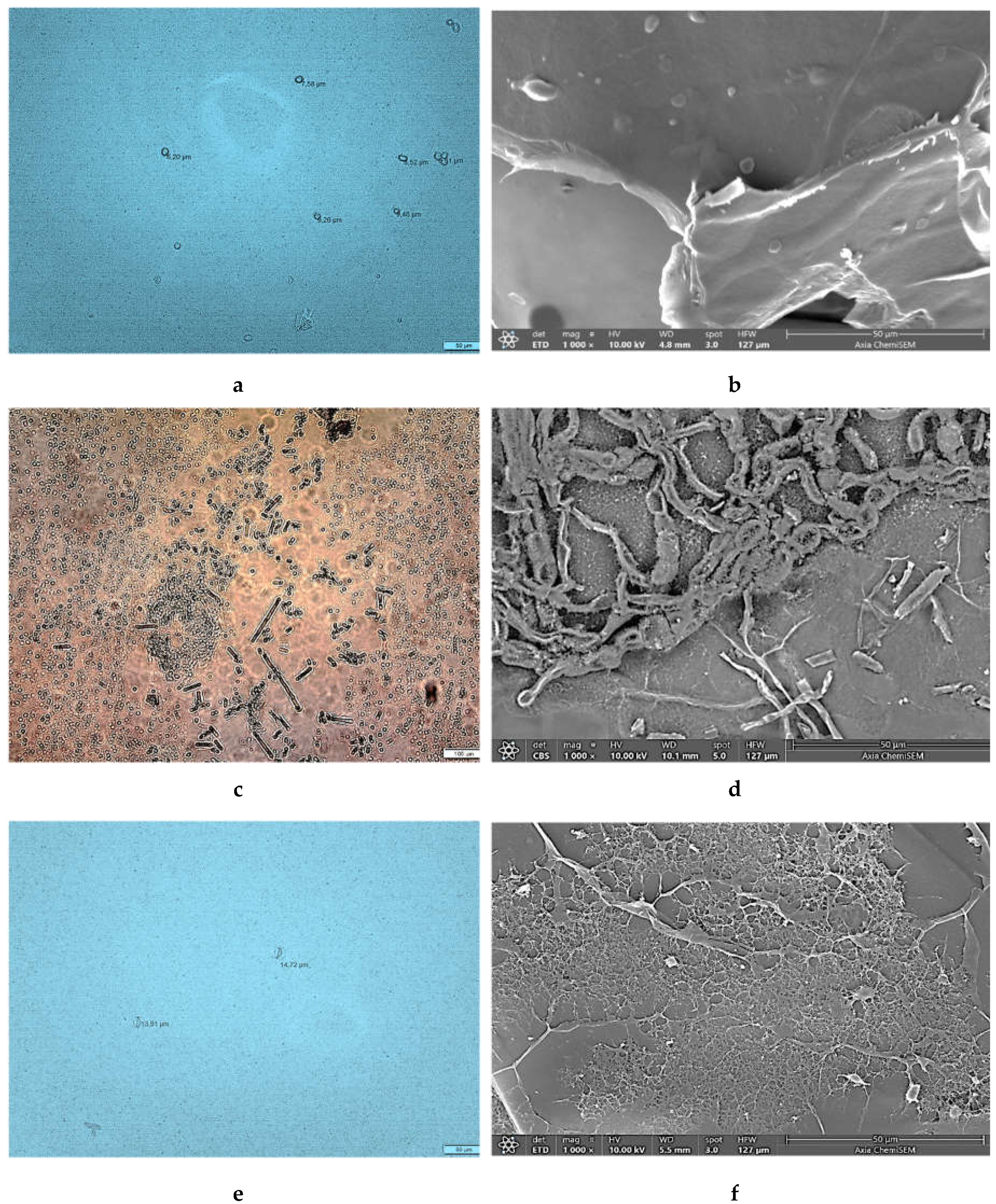

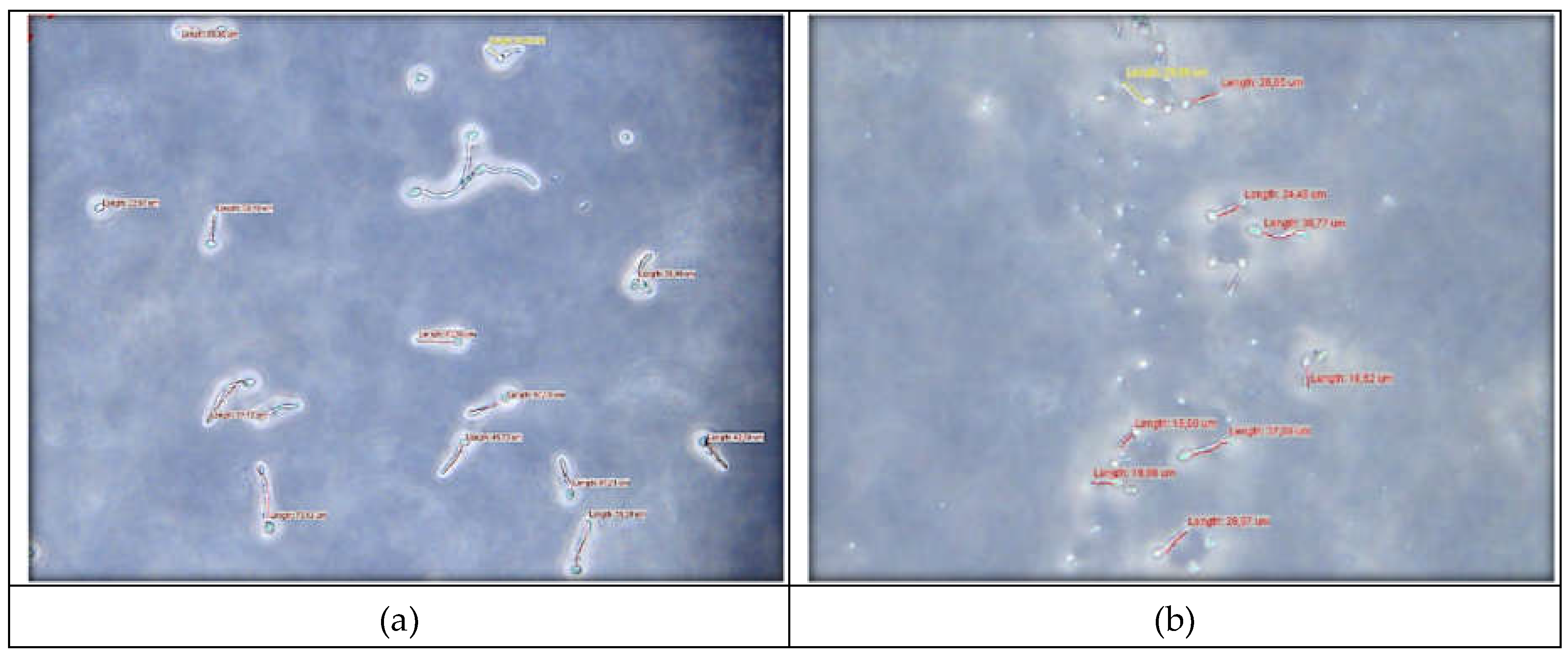

3.2.1.2. Morphological Properties of B. cinerea, C. beticola and P. ramorum Spores and Mycelium

Optical microphotographs of pathogen spores suspended in distilled water and SEM images of dryed spores are presented in

Figure 8. The conidia of

B. cinerea are ellipsoidal to ovoid with an approximate size of 15 µm (

Figure 8a) which is consistent with literature data [

58]. Microphotograph of

C. beticola (

Figure 8c) reveals a needle-like and colorless conidia approximately 43 µm in size which is consistent with previous descriptions [

59].

P. ramorum sporangia are approximately 23 µm in size and ellipsoid (

Figure 8e) which is consistent with literature data [

60].

SEM characterization revealed noticeable microstructural differences between three plant pathogenic species. Microphotograph of

B. cinerea shows a tapered apical dome of hypha with a smooth surface, ellipsoidal conidia, conidiophore and hyphae (

Figure 8b). SEM characterization revealed noticeable microstructural differences between

C. beticola and

P. ramorum.

C. beticola shows the presence of straight to flexuous conidia, and loosely arranged hyphae (

Figure 8d). Pseudo-fungi

P. ramorum exhibit thinner but densely packed hyphae (

Figure 8f) compared to those of

C. beticola forming a network structure.

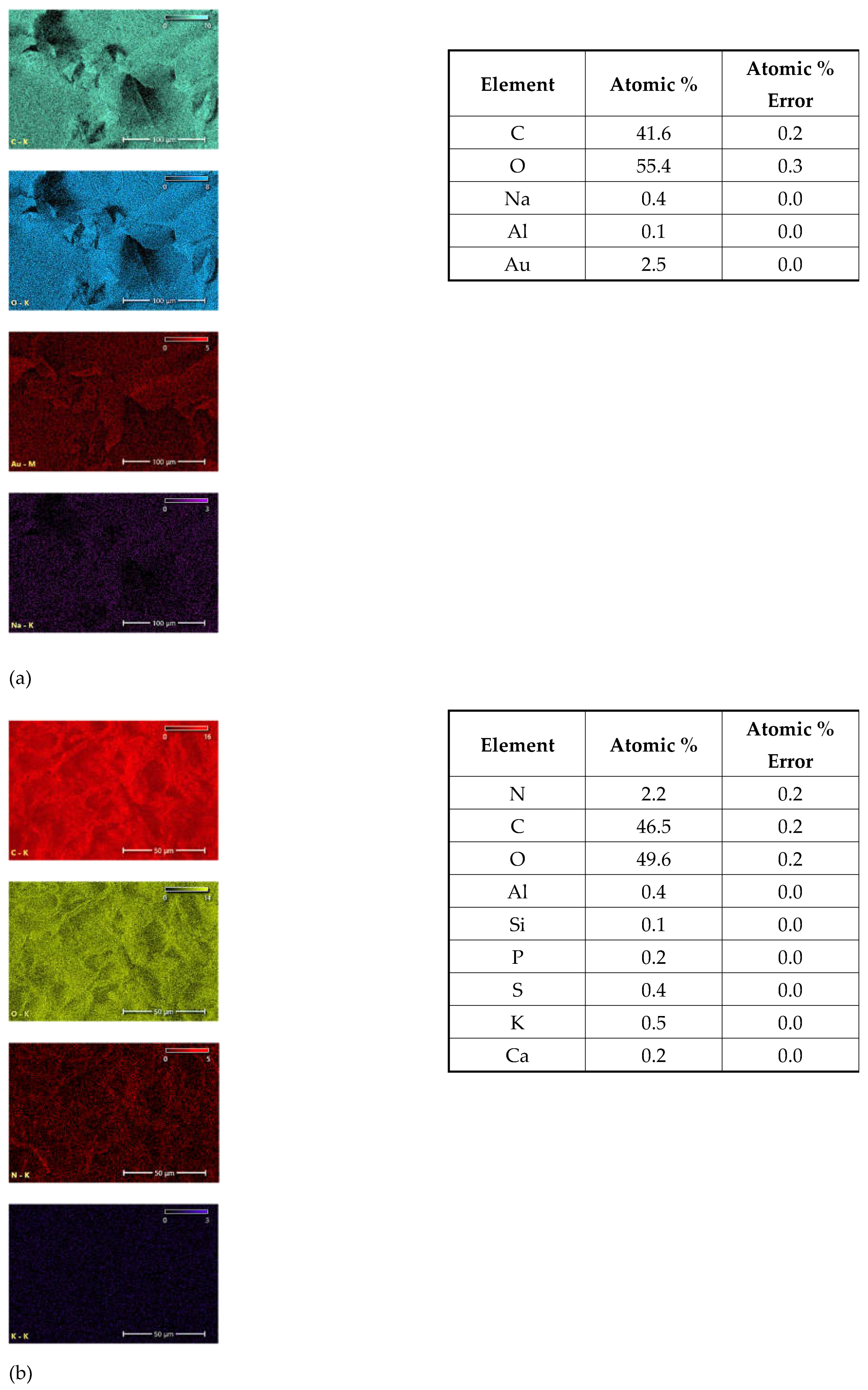

EDS elemental mapping of the investigated plant parasites provides spatial distribution and elemental composition on the surface of mycelia (

Figure 9). The spatial distribution of the most abundant elements in the surface layer is presented in the left colon. All identifiable elements are listed in the tables to the corresponding images. The detected amount of Au is probably a residue after sample preparation for analysis.

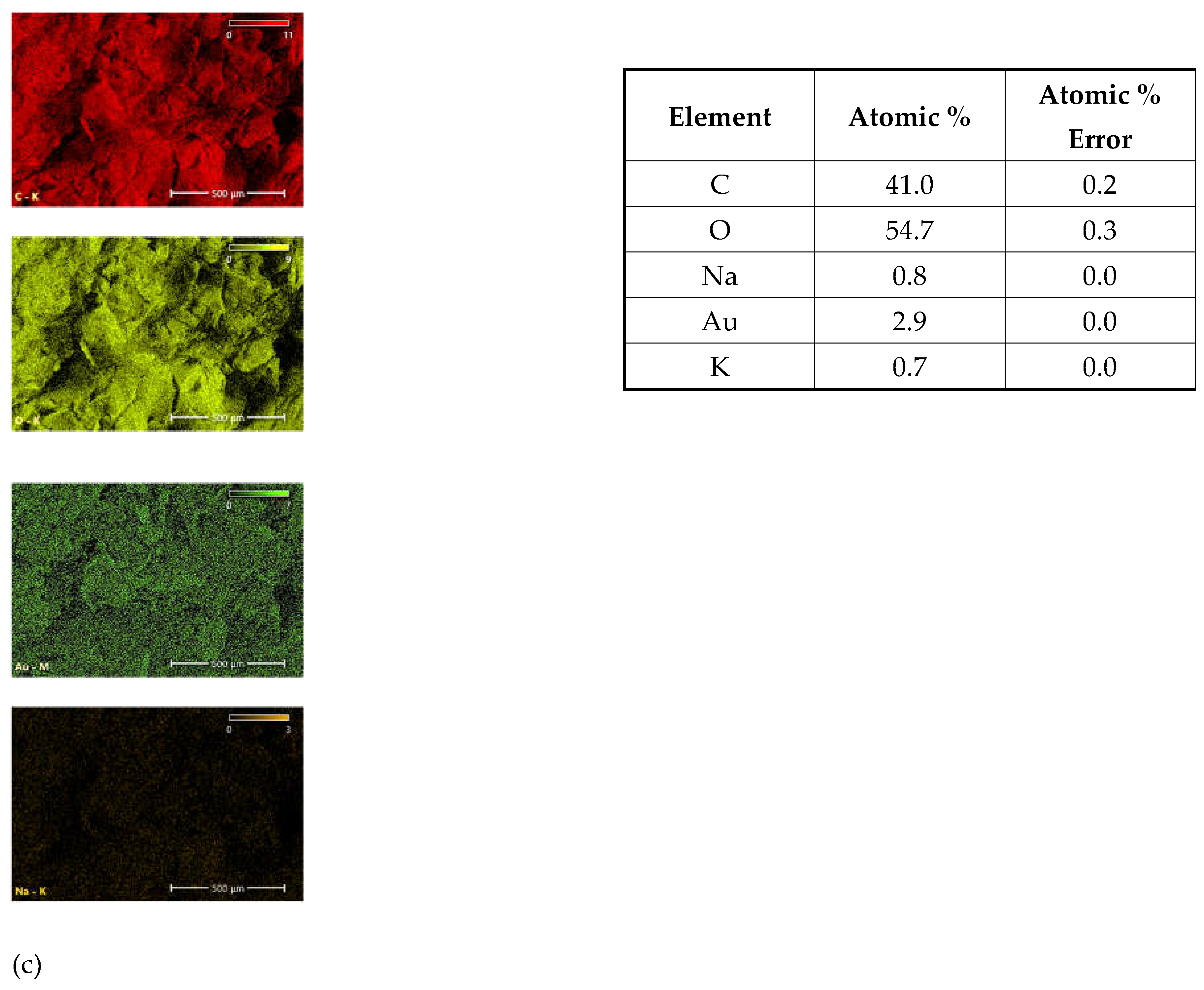

3.2.1.3. Influence of Copper Ion Concentrations on the Electrostatic Charge and Size of Fungal Spores

The microbial cell is the natural adsorbent for metal ions due to its nature and the composition of the cellular membrane. The cell walls of fungi are generally composed of chitin, chitosan, β-glucans and mannan [

61]. In addition, cell walls may contain lipids, protein, acid phosphatase, α-amylase, protease, melanin, and inorganic ions such as phosphorus, calcium, and magnesium [

62]. The cell wall of oomycetes is different than in fungi, containing polysaccharides such as cellulose and other β-glucans [

63]. Filamentous fungi accumulate metal ions into their mycelium and spores via mechanisms involving the fungal cell wall (intracellular/biosorption and extracellular/adsorption processes), which is also important for their survival and performance, as well as energetic uptake and valence conversion [

64,

65]. The influence of different concentrations of copper cations on spores suspended in water was examined with a microscope, as well as by measuring the spore size, charge and zeta potential. The microscopic observation (not shown) clearly shows the effects of copper ions concentration on the number of single spores, that is the increase in copper ions concentration resulted in their aggregation. Aggregation in submerged cultures of filamentous fungi depends on the surface charge of spores [67]. An important parameter describing the behavior of the solid-liquid interface charge is zeta potential. It is the electric potential of the shear plane in the electric double layer of a moving particle, and it is related to the particle surface charge. The surface charge of the fungal spore wall depends on the available functional groups. The relatively high negative zeta potential of all spores suspended in distilled water (-26 mV for

B. cinerea; -29 mV for

C. beticola; -23 mV for

P. ramorum)) is in line with FTIR data and analysis of the relationship between relative surface hydrophobicity and surface electric charge [67]. The surface coating on top of the cell wall plays a crucial part in the electrostatic nature of the investigated species. The negative charge arises from various functional groups such as carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine and phosphate [68]. With increasing copper ions concentration, fungal spores became less negatively charged due to the electrostatic binding of copper cations (

Figure 10a). The negative value of the zeta potential decreased as the concentration of copper ions increased. All spores maintained their negative charge even at greater copper cation concentrations. Zeta potential is often used to explain the aggregation of microbial cells. At a lower concentration where the greatest changes in the zeta potential were observed, the size of measured particles was significantly changed (

Figure 10b). The increase of copper cation concentration resulted in the aggregation of spores.

3.2.2. Antifungal Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres on B. cinerea, C. beticola and P. ramorum

3.2.2.1. Antifungal Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres on B. cinerea

Conidial germination of

B. cinerea was verified if the germ tube length was equal to or greater than the conidia length [69]. After incubation, the lengths of the germ tubes were measured. Germ tube length measurement data are listed in

Table 3.

Figure 11 shows the length of germ tubes measured in the control and in Sample 3.

The results showed that three tested copper alginate samples inhibited conidial germination (

Table 4). The percentage of inhibition was calculated as follows [70],

where L

c is the average length of the germ tube in control and L

Cu is the average length of the germ tube in treatment.

The inhibitory effect of copper alginate microspheres on B. cinerea increased with increasing concentration of Cu2+ incorporated in copper alginate microspheres. The smallest germ tube length measured with Sample 3 reveals 48% inhibition which is even higher than with the commercial fungicide, Neoram® (inhibition 22 %).

Copper alginate microspheres prepared with different initial concentrations of Cu2+ were used to evaluate the antifungal effect on B. cinerea isolates. In addition to the easy formation of microspheres the advantage of alginate is its antimicrobial effect against various bacteria [71]. The results showed that copper alginate microspheres affect the length of the germ tube of B. cinerea and have the potential to control disease in the early stages of crop growth. This is consistent with the finding that Cu2+ binds to the surface of B. cinerea spores during germination and slows it down [72].

3.2.2.2. Antifungal Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres on C. beticola

The number of

C. beticola colonies in the control and samples treated with copper alginate microspheres was counted. Data are listed in

Table 5.

The relative percentage of developed colonies (inhibition percentage) was calculated based on the ratio between control and copper alginate microspheres. The percentage of inhibition was calculated as follows:

where X is the average number of colonies on the control sample and Y is the average number of colonies on samples treated with copper alginate microspheres. Inhibition percentages of 61 % for Sample 1 and 72 % for Sample 2 revealed they are effective in preventing the development of

C. beticola colonies. The Cu

2+ release inhibits the activity of fungal spores to prevent germination and provide a protective barrier against plant pathogens by covering plant surfaces [73].

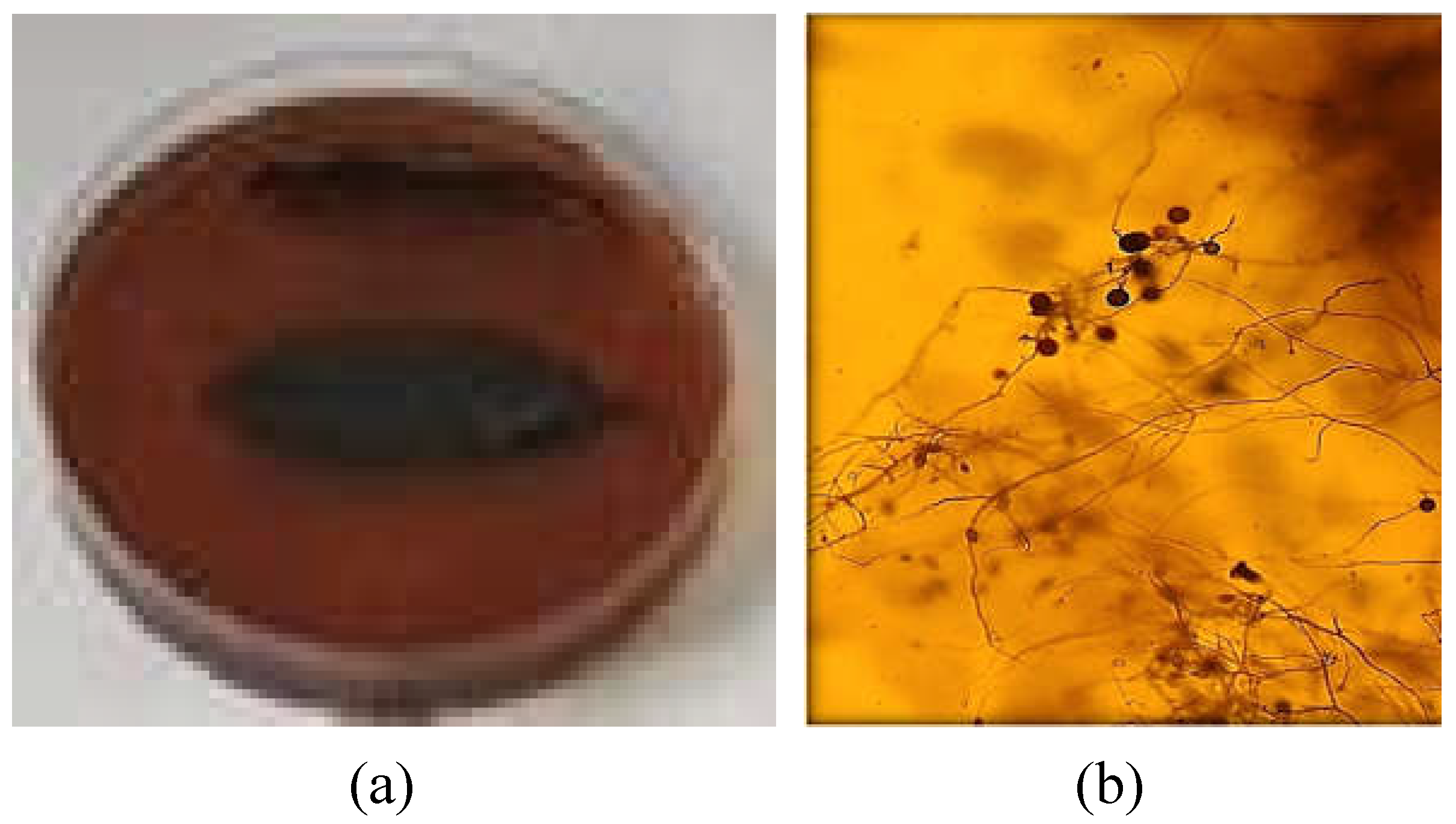

3.2.2.3. Antifungal Effect of Copper Alginate Microspheres on P. ramorum

The effectiveness of copper alginate microspheres on

P. ramorum was evaluated by visual observation of color changes in control solutions and solutions with samples treated with copper alginate, as well as by examination of infection symptoms characteristic of

P. ramorum on rhododendron leaves. Visual inspection revealed the most pronounced color change in the control Petri dishes (

Figure 12a). The presence of mycelia was confirmed by microscopy (

Figure 12b). In Petri dishes with copper alginate microspheres, the color change was weaker indicating slower mycelial growth (not shown).

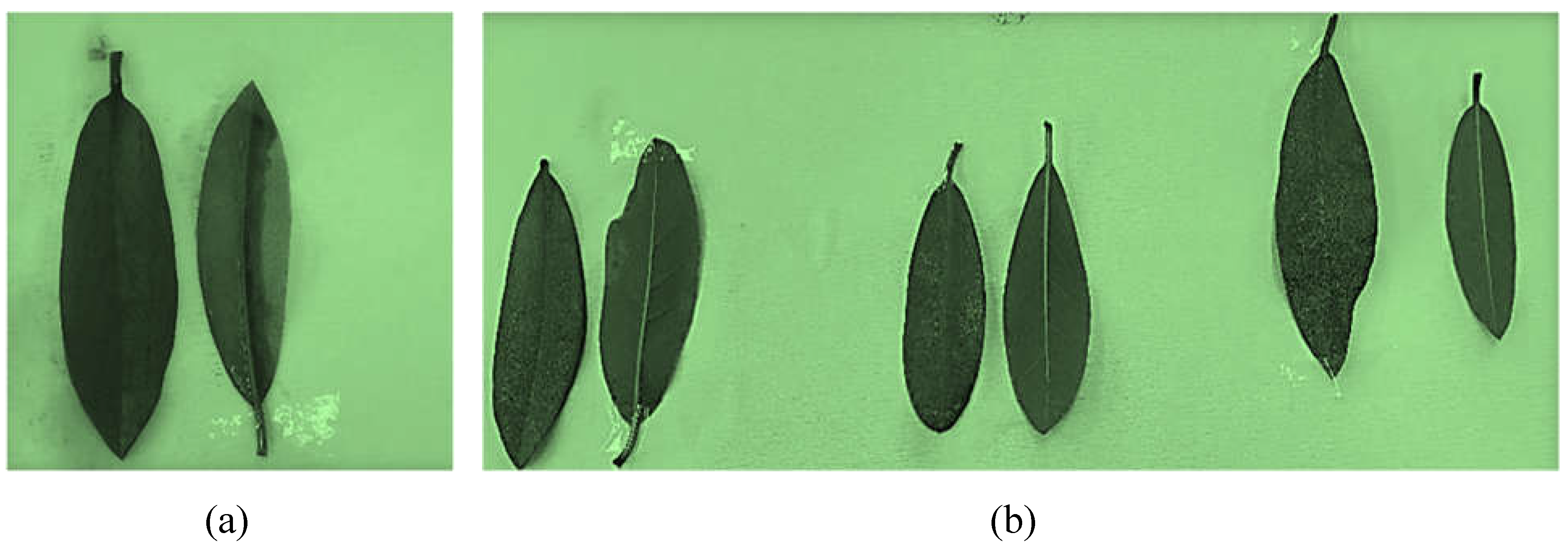

The presence of mycelia and a large number of sporangia and zoospores on the control leaves was confirmed with a microscope (

Figure 13a). Mycelia, sporangia, and zoospores did not develop on most leaves treated with copper alginate microspheres, although some leaves showed infection symptoms characteristic of

P. ramorum (

Figure 13b). Only a few and mostly empty and deformed sporangia were observed.

The obtained results revealed that copper alginate microspheres inhibited the development of P. ramorum mycelium. As already mentioned with the fungus B. cinerea and C. beticola, the microspheres can be used alone or as an addition to other fungicides.

4. Concluding Remarks

We have used a multi-technique approach to investigate copper alginate microsphere properties/performance prepared at various copper ion concentrations and their antifungal potential.

Molecular interactions between copper and alginate, microspheres morphology and topography, copper amount in microspheres, swelling behavior and copper ions release from microspheres depend on copper ions concentration.

Rheological tests showed the formation of well-ordered and elastic structures that are stable for a long time regardless of the concentration of copper ions. All microspheres have a similar structural arrangement, although the slightly lower value of the elastic modulus of those prepared with the highest concentration of copper indicates a slightly looser network structure.

Microspheres prepared at the highest copper concentration have the highest copper loading, the smoothest surface, the highest swelling ability, and the weakest crosslinking density between alginate strands, and release a larger amount of copper ions at a faster rate.

The prepared microspheres are designed to deliver copper ions at a specific time and place providing longer protection against fungal infections. The targeted application of microspheres reduces the total amount of copper ions needed. The mechanism that controls the release rate from microspheres is Fickian diffusion.

Copper alginate microspheres can persist on plant surfaces which is an important step in the foliar application of copper-based fungicides. The smallest roughness parameters indicated a better adhesion ability of microspheres prepared at the highest concentration of copper ions compared to other samples.

The morphological analysis of the selected pathogens followed literature descriptions (conidias of B. cinerea are ellipsoid to ovoid, C. beticola needle-like, and sporangia of P. ramorum ellipsoidal).

FTIR analysis of B. cinerea, C. beticola and P. ramorum revealed a typical fungal spectrum with characteristic functional groups (fatty acids, amide I and II, polysaccharides and specific fingerprint region).

The negative charge of the fungal spore wall arises from various functional groups (carboxyl, hydroxyl, amine and phosphate). The addition of copper ions reduced the negative value of zeta potential and induced the aggregation of spores.

In vitro experiments revealed new microspheres as potential fungicides against phytopathogenic fungi. The copper ions release affected conidial germination of B. cinerea and the mycelial growth of C. beticola and P. ramorum.

Among the advantages of copper alginate microspheres compared to traditional fungicides in the control of plant diseases are an environmentally acceptable and cost-effective production method, but the most important advantages are the slow release of copper ions and a potentially longer duration of action. The periods between treatments and the number of treatments can be shortened, and the protection can be longer. With further research, the new copper alginate microspheres can be used as natural, ecological fungicides in the process of protecting plant crops from several important fungal diseases.

Author Contributions

M.V.: conceptualization, methodology, writing original draft, project management and funding acquisition, K.V.K.: formal analysis, S.J.: conceptualization, supervision, and editing; I.D. and A.N. review and editing. L.H.: formal analysis, A.B. formal analysis, N.Š.V. formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Doehlemann, G.; Ökmen, B.; Zhu, W.; Sharon, A. Plant pathogenic fungi. Microbiol. Spectrum. 2017, 5(1), FUNK-0023-2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tudi, M.; Li, H.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Lyu, J.; Yang, L.; Tong, S.; Yu, Q.J.; Ruan, H.D.; Atabila, A.; Phung, D.T.; Sadler, R.; Connell, D. Exposure Routes and Health Risks Associated with Pesticide Application. Toxics. 2022, 10, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Lombi, E.; Zhao, F.J.; Kopittke, P.M. Nanotechnology: A New Opportunity in Plant Sciences. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21(8), 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pariona, N.; Mtz-Enriquez, A.; Sanchez-Rangel, D.; Carrion, G.; Paraguay-Delgado, F.; Rosas-Saito, G. Green-synthesized copper nanoparticles as a potential antifungal against plant pathogens. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kah, M.; Kookana, R.S.; Gogos, A.; Bucheli, T.D. A critical evaluation of nanopesticides and nanofertilizers against their conventional analogues. Nat. Nanotechn. 2018, 13(8), 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rusjan, D. Copper in Horticulture. In: Fungicides for Plant and Animal Diseases. Dhanasekaran, D.; Thajuddin, N.; Panneerselvam, A. (eds.) Intec Open. 2012, Ch. 13, pp. 257-278. [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, J.R.; Osdaghi, E.; Behlau, F.; Kohl, J.; Jones, J.B.; Aubertot, J.N. Thirteen decades of antimicrobial copper compounds applied in agriculture. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2018, 38, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La, T.A.; Iovinom, V.; Caradonia, F. Copper in plant protection: current situation and prospects. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 2018, 57, 201–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plante, S.; Normant, V.; Ramos-Torres, K.M.; Labbé, S. Cell-surface copper transporters and superoxide dismutase 1 are essential for outgrowth during fungal spore germination. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292(28), 11896–11914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Jiang, Y.; Shi, H.; Peng, Y.; Fan, X.; Li, C. The molecular mechanisms of copper metabolism and its roles in human diseases. Pflugers Arch. – Eur. J. Physiol. 2020, 472, 1415–1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, M.; Liu, L.; Wang, Q.; Saleem, M.H.; Bashir, S.; Ullah, S.; Peng, D. Copper environmental toxicology, recent advances, and future outlook: a review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 18003–18016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varaprasad, K.; Jayaramudu, T.; Kanikireddy, V.; Toro, C.; Sadiku, E.R. Alginate-based composite materials for wound dressing application. A mini review. Carbohydr. Polym., 2020, 236, 1–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceković, M.; Jalšenjak, N.; Topolovec-Pintarić, S.; Đermić, E.; Bujan, M.; Jurić, S. Encapsulation of Biological and Chemical Agents for Plant Nutrition and Protection: Chitosan/Alginate Microcapsules Loaded with Copper Cations and Trichoderma viride. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2016, 64, 8073–8083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceković, M.; Jurić, S.; Vlahovićek-Kahlina, K.; Martinko, K.; Šegota, S.; Marijan, M.; Krčelić, A.; Svečnjak, L.; Majdak, M.; Nemet, I.; Rončević, S.; Rezić, I. Novel Zinc/Silver Ions-Loaded Alginate/Chitosan Microparticles Antifungal Activity against Botrytis cinerea. Polymers 2023, 15, 4359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.M.; Yu, W.T.; Liu, X.D.; He, X.; Wang, W.X.; Ma, J. Chemical method of breaking the cell-loaded sodium alginate/chitosan microcapsules. Chem. J. Chin. Univ. 2004, 25, 1342–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Mokale, V.; Jitendra, N.; Yogesh, S.; Gokul, K. Chitosan reinforced alginate controlled release beads of losartan potassium: design, formulation and in vitro evaluation. J. Pharm. Investig. 2014, 44, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nečas, D.; Klapetek, P. Gwyddion: an open-source software for SPM data analysis. Centr. Eur. J. Phys. 2012, 10, 181–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, W.S. A Method of Computing the Effectiveness of an Insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925, 18, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceković, M.; Topolovec Pintarić, S.; Jurić, S.; Viskić, M.; Jalšenjak, N.; Bujan, M.; Đermić, E.; Žutić, I.; Fabek, S. Release of Trichoderma viride Spores from Microcapsules Simultaneously Loaded with Chemical and Biological Agents. Agri. Consp. Sci. 2017, 82(4), 395–401. [Google Scholar]

- Gamo, I. Infrared Absorption Spectra of Water of Crystallization in Copper Sulfate Penta- and Monohydrate Crystals. BCSJ. 1961, 34, 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Lu, W.; Mata, A.; Nishinari, K.; Fang, Y. Ions-induced gelation of alginate: Mechanisms and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 177, 578–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, S.; Đermić, E.; Topolovec-Pintarić, S.; Bedek, M.; Vinceković, M. Physicochemical properties and release characteristics of calcium alginate microspheres loaded with Trichoderma viride spores. J. Integr. Agric. 2019, 18(0), 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haug, A.; Smidsrod, O.A.; Högdahl, B.; Øye, H.A.; Rasmussen, S.E.; Sunde, E.; Sörensen, N.A. Selectivity of Some Anionic Polymers for Divalent Metal Ions. Acta Chem. Scand. 1970, 24, 843-854. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, J.F.; Aquino, T.F.; Nascimento, J.E.; Jacob, R.G.; Fajardo, A.R. Alginate-copper microspheres as efficient and reusable heterogeneous catalysts for the one-pot synthesis of 4-organylselanyl-1H-pyrazoles. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 3918–3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedy, S.H.; Abd El Hafez, M.S.M.; Dar, M.A.; Cotas, J.; Pereira, L. Evaluation and Characterization of Alginate Extracted from Brown Seaweed Collected in the Red Sea. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Liu, X.; Tong, Z. Critical exponents for sol–gel transition in aqueous alginate solutions induced. Carbohydr. Polym. 2006, 65, 544–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, S.K.; Kouvelos, E.P.; Favvas, E.P.; Sapalidis, A.A.; Romanos, G.E.; Katsaros, F.K. Metal–carboxylate interactions in metal–alginate complexes studied with FTIR Spectroscopy. Carbohydr. Res. 2010, 345, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omidian, H.; Rocca, J.G.; Park, K. Advances in superporous hydrogels. J. Control. Release. 2005, 102(1), 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, S.; Šegota, S.; Vinceković, M. Influence of surface morphology and structure of alginate microparticles on the bioactive agents release behavior. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 218, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, H.G.; Zheng, J.N; Li, X,X.; Liu, X.D.; Zhu, J.; Wang, F.; Xie, W.Y.; Ma, X.J. Effect of surface morphology and charge on the amount and conformation of fibrinogen adsorbed onto alginate/chitosan microcapsules. Langmuir. 2010, 26(8), 5587-5594. [CrossRef]

- Roy, A.; Singh, S.K.; Bajpai, J.; Bajpai, J.K. Controlled pesticide release from biodegradable Polymers. Cent. Eur. J. Chem. 2014, 12, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, A.; Egan, S.J.; Bakalis, S.; Zhang, Z. Determination of microcapsule physicochemical, structural, and mechanical properties. Particuology. 2016, 24, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Dunn, P.F.; Brach, R.M. Surface roughness effects on microparticle adhesion. J. Adhesion. 2002, 78, 929–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rolando, C.; Somchit, C.; Bader, M.K-F.; Fraser, S.; Williams, N. Can Copper Be Used to Treat Foliar Phytophthora Infections in Pinus radiata? Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 1809-2147. [CrossRef]

- Leick, S.; Kott, M.; Degen, P.; Henning, S.; Päsler, T.; Suter, D. et al., Mechanical properties of liquid-filled shellac composite capsules. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. PCCP 2011, 13, 2765–2773. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malektaj, H.; Drozdov, A.D.; deClaville Christiansen, J. Mechanical Properties of Alginate Hydrogels Cross-Linked with Multivalent Cations. Polymers. 2023, 15, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siepmann, J.; Siepmann, F. Modeling of diffusion controlled drug delivery. J. Control. Release. 2012, 161, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinceković, M.; Jurić, S.; Đermić, E.; Topolovec Pintarić, S. Kinetics and Mechanisms of Chemical and Biological Agents Release from Biopolymeric Microcapsules. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65(44), 9608–9617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talevi, A.; Ruiz, M.E. Korsmeyer-Peppas, Peppas-Sahlin, and Brazel-Peppas: Models of Drug Release. In: The ADME Encyclopedia. Springer, Cham. 2021, pp. 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Vigata, M.; Meinert, C.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Bock, N. Hydrogels as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of Current Characterization and Evaluation Techniques. Pharmaceutics. 2020, 12(12), 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elad, Y.; Vivier, M.; Fillinger, S. Botrytis, the Good, the Bad and the Ugly. In: Fillinger, S.; Elad, Y. (eds.) Botrytis – the Fungus, the Pathogen and its Management in Agricultural Systems. Springer, Cham. 2016, pp. 1-15. [CrossRef]

- De Miccolis Angelini, Pollastro, S.; Faretra, F. Genetics of Botrytis cinerea. In: Fillinger, S., Elad, Y. (eds) Botrytis – the Fungus, the Pathogen and its Management in Agricultural Systems. Springer, Cham. 2016, pp. 433-55. [CrossRef]

- Notte, A.M;. Plaza, V.; Marambio-Alvarado, B.; Olivares-Urbina, L.; Poblete-Morale.s M.; Silva-Moreno, E.; Castillo L. Molecular identification and characterization of Botrytis cinerea associated to the endemic flora of semi-desert climate in Chile. Curr. Res. Microb. Sci. 2021 2, 100049. [CrossRef]

- CABI. Cercospora beticola (cercospora leaf spot of beets). Invasive Species, Compendium. 2022, https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/12191 - 16.07.2022.

- Rangel, L.I.; Spanner, R.E.; Ebert, M.K.; Pethybridge, S.J.; Stukenbrock, E.H., de Jonge, R. et al. Cercospora beticola: The intoxicating lifestyle of the leaf spot pathogen of sugar beet. Mol. Plant Pathol, 2020, 21, 1020–1041. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Mazakova, J.; Ali, A.; Sur, V.P.; Sen, M.K.; Bolton, M.D.; Manasova, M.; Rysanek, P.; Zouhar, M. Characterization of the Molecular Mechanisms of Resistance against DMI Fungicides in Cercospora beticola Populations from the Czech Republic. J. Fungi. 2021, 7, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coque, J.J.R.; Álvarez-Pérez, J.M.; Cobos, R.; González-García, S.; Ibáñez, A.M.; Diez Galán, A.; Calvo-Peña, C. Advances in the control of phytopathogenic fungi that infect crops through their root system. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 2020, 111, 123–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grünwald, N.J.; Goss, E.M. Press CM. Phytophthora ramorum: a pathogen with a remarkably wide host range causing sudden oak death on oaks and ramorum blight on woody ornamentals. Mol Plant Pathol. 2008, 9(6), 729-40. [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance copper compounds copper(I), copper(II) variants namely copper hydroxide, copper oxychloride, tribasic copper sulfate, copper(I) oxide, Bordeaux mixture. EFSA Journal, 2018, 16, e05152. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salah, I.; Parkin, I.O.; Allan, E. Copper as an antimicrobial agent: recent advances. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 18179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mularczyk-Oliwa, M.; Bombalska, A.; Kaliszewski, M.; Włodarski, M.; Kwaśny, M.; Kopczyński, K.; Szpakowska, M.; Trafny, E.A. Rapid discrimination of several fungus species with FTIR spectroscopy and statistical analysis. Biuletyn WAT. 2013, 62, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, A.; Pomerantz, A. Tsror, L.; Lapidot; I.; Moreh, R.; Mordechai, S.; Huleihel M. Utilizing FTIR-ATR spectroscopy for classification and relative spectral similarity evaluation of different Colletotrichum coccodes isolates. Analyst. 2012, 137(15), 3558-64. [CrossRef]

- Skolik, P.; Morais, C.L.M.; Martin, F.L.; McAinsh, M.R. Attenuated total reflection Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy coupled with chemometrics directly detects pre- and post-symptomatic changes in tomato plants infected with Botrytis cinerea. Vib .Spectrosc. 2020, 111, 103171. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/vibrational-spectroscopy.

- Wittayapipath, K.; Laolit, S.; Yenjai, C.; Chio-Srichan, S.; Pakarasang, M.; Tavichakorntrakool, R.; Prariyachatigul, C. Analysis of xanthyletin and secondary metabolites from Pseudomonas stutzeri ST1302 and Klebsiella pneumoniae ST2501 against Pythium insidiosum. BMC Microbiol. 2019, 19(1), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, A.; Lapidot, I.; Pomerantz, A.; Tsror, L.; Shufan, E.; Moreh, R.; Mordechai, S.; Huleihel, M. Identification of fungal phytopathogens using Fourier transform infrared-attenuated total reflection spectroscopy and advanced statistical methods. J. Biomed. Opt. 2012, 17(1), 017002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Szeghalmi, S.: Kaminskyj, K.M.; Gough, A synchrotron FTIR microspectroscopy investigation of fungal hyphae grown under optimal and stressed conditions. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 1779-1789. [CrossRef]

- Synytsya, A.; Novak, M. Structural analysis of glucans. Ann. Transl. Med. 2014, 2(2), 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, Y.; Tao, Q. J.; Zheng, X.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Z.; Gong, G. Phenotypic and Genetic Characterization of Botrytis cinerea Population from Kiwifruit in Sichuan Province, China. Plant Dis. 2019, 103, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oerke, E.C.; Leucker, M.; Steiner, U. Sensory assessment of Cercospora beticola sporulation for phenotyping the partial disease resistance of sugar beet genotypes. Plant Methods. 2019, 15, 133 (2019). [CrossRef]

- Grünwald, N.J.; Goss, E.M. Press CM. Phytophthora ramorum: a pathogen with a remarkably wide host range causing sudden oak death on oaks and ramorum blight on woody ornamentals. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2008, 9(6), 729-40. [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Rusyn, I.; Dmytruk, O.V.; Dmytruk, K.V.; Onyeaka H, Gryzenhout M, Gafforov Y. Filamentous fungi for sustainable remediation of pharmaceutical compounds, heavy metal and oil hydrocarbons. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 1106973. [CrossRef]

- Gow, N.A.R.; Lenardon, M.D. Architecture of the dynamic fungal cell wall. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 248–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGowan, J.; Fitzpatrick, D.A. Chapter Five - Recent advances in comycete genomics. Adv. Genet. 2020, 105, 175–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dusengemungu, L.; Kasali, G.; Gwanama, C.; Ouma, K.O. Recent Advances in Biosorption of Copper and Cobalt by Filamentous Fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 582016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jurić, S.; Tanuwidjaja, I.; Fuka, M.M.; Vlahoviček-Kahlina, K.; Marijan, M.; Boras, A.; Kolić, N.U.; Vinceković, M. Encapsulation of two fermentation agents, Lactobacillus sakei and calcium ions in microspheres. Colloids Surf. B. 2021, 197, 111387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wargenau, A.; Fleissner, A.; Bolten, C.J.; Rohde, M.; Kampen, I.; Kwade, A. On the origin of the electrostatic surface potential of Aspergillus niger spores in acidic environments. Res. Microbiol. 2011, 162(10), 1011–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, C.A.; Biresaw, G.; Jackson, M.A. Hydrophobic and electrostatic cell surface properties of blastospores of the entomopathogenic fungus Paecilomyces fumosoroseus. Colloids Surf. B. Biointerfaces. 2005, 46(4), 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Gong, G.; Zha, J. Microbial cell surface engineering for high-level synthesis of bio-products. Biotechnol. Adv. 2022, 55, 107912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicedo, B.; de la O Leyva, M.; Flors, V.; Finiti, I.; Del Amo, G.; Walters, D.; Real, M.D.; García-Agustín, P.; González-Bosch, C. Control of the phytopathogen Botrytis cinerea using adipic acid monoethyl ester. Arch. Microbiol. 2006, 184(5), 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Youssef, K.; de Oliveira, A.G.; Tischer, C.A.; Hussain, I.; Roberto, S.R. Synergistic effect a novel chitosan/silica nanocomposites-based formulation against gray mold of table grapes and its possible mode of action. Int. J. Biolog. Macromol. 2019, 141, 247–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasina, D.V.; Antonova, N.P.; Shidlovskaya, E.V.; Kuznetsova, N.A.; Grishin, A.V.; Akoulina, E.A.; Trusova, E.A.; Lendel, A.M.; Mazunina, E.P.; Kozlova, S.R.; et al. Alginate Gel Encapsulated with Enzybiotics Cocktail Is Effective against Multispecies Biofilms. Gels. 2024, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Ramos, F.; Briones-Labarca, V.; Plaza, V.; Castillo, L. Iron and copper on Botrytis cinerea: new inputs in the cellular characterization of their inhibitory effect. PeerJ. 2023, 11, e15994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.F.; Xue, X.J.; Yu, Y.; Xu, M.M.; Lu, C.C.; Meng, X.L.; Zhang, B.G.; Ding. X.H.; Chu, Z.H. Copper ions suppress abscisic acid biosynthesis to enhance defence against Phytophthora infestans in potato. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21(5), 636-651. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of ALG/Cu microspheres prepared at initial Cu2+ concentration: 8 mmol dm-3 (Sample 1), 12 mmol dm-3 (Sample 2) and 16 mmol dm-3 (Sample 3).

Figure 1.

FTIR spectra of ALG/Cu microspheres prepared at initial Cu2+ concentration: 8 mmol dm-3 (Sample 1), 12 mmol dm-3 (Sample 2) and 16 mmol dm-3 (Sample 3).

Figure 2.

SEM microphotographs of copper alginate microspheres (a) Sample 1, (b) Sample 2 and (c) Sample 3. Bars are indicated. The EDX analysis (expressed as atomic weight percentage) of the surface layers is shown on the right side next to the corresponding microspheres.

Figure 2.

SEM microphotographs of copper alginate microspheres (a) Sample 1, (b) Sample 2 and (c) Sample 3. Bars are indicated. The EDX analysis (expressed as atomic weight percentage) of the surface layers is shown on the right side next to the corresponding microspheres.

Figure 3.

AFM micrographs of analyzed samples-top view of 2D-height data and 3D—height data of (a) Sample 1, (b) Sample 2, and (c) Sample 3, from top to down presented higher magnifications.

Figure 3.

AFM micrographs of analyzed samples-top view of 2D-height data and 3D—height data of (a) Sample 1, (b) Sample 2, and (c) Sample 3, from top to down presented higher magnifications.

Figure 4.

Amplitude sweep tests (G′ (■) and G″ (▲) values) of Sample 1 (red), Sample 2 (green), and Sample 3 (blue) were determined at a constant angular frequency of 5 rad/s at 25°C.

Figure 4.

Amplitude sweep tests (G′ (■) and G″ (▲) values) of Sample 1 (red), Sample 2 (green), and Sample 3 (blue) were determined at a constant angular frequency of 5 rad/s at 25°C.

Figure 5.

Frequency sweep test (G′ (■) and G″ (▲) values) of Sample 1 (red), Sample 2 (green), and Sample 3 (blue) at a strain of 0.1 % and 25 °C.

Figure 5.

Frequency sweep test (G′ (■) and G″ (▲) values) of Sample 1 (red), Sample 2 (green), and Sample 3 (blue) at a strain of 0.1 % and 25 °C.

Figure 6.

Fraction of released copper (fCu) with time (t) from (ALG/Cu) microspheres prepared at initial Cu2+ concentration: 8 mmol dm-3 (Sample 1), 12 mmol dm-3 (Sample 2) and 16 mmol dm-3 (Sample 3). Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the means.

Figure 6.

Fraction of released copper (fCu) with time (t) from (ALG/Cu) microspheres prepared at initial Cu2+ concentration: 8 mmol dm-3 (Sample 1), 12 mmol dm-3 (Sample 2) and 16 mmol dm-3 (Sample 3). Error bars indicate the standard deviation of the means.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of fungal mycelium: P. ramorum (black line), B. cinerea (red line) and C. beticola (blue line). Regions attributed to fatty acids (I), amide I and II (II) and polysaccharides (III) are denoted.

Figure 7.

FTIR spectra of fungal mycelium: P. ramorum (black line), B. cinerea (red line) and C. beticola (blue line). Regions attributed to fatty acids (I), amide I and II (II) and polysaccharides (III) are denoted.

Figure 8.

Microphotographs of (a) B. cinerea, (c) C. beticola and (e) P. ramorum spores obtained by optical microscope (OM) and (b) B. cinerea, (d) C. beticola and (f) P. ramorum spores, condiospores and hyphae obtained by scanning electron microscope (SEM). The bars are indicated.

Figure 8.

Microphotographs of (a) B. cinerea, (c) C. beticola and (e) P. ramorum spores obtained by optical microscope (OM) and (b) B. cinerea, (d) C. beticola and (f) P. ramorum spores, condiospores and hyphae obtained by scanning electron microscope (SEM). The bars are indicated.

Figure 9.

Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) element mapping images of mycelium (a) B. cinerea (C, O, Au and K distribution) (b) C. beticola (C, O, N and K distribution) and (c) P. ramorum (C, O, Au and Na distribution) and elemental analysis (expressed in the atomic weight percent) using dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Bars are indicated.

Figure 9.

Energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) element mapping images of mycelium (a) B. cinerea (C, O, Au and K distribution) (b) C. beticola (C, O, N and K distribution) and (c) P. ramorum (C, O, Au and Na distribution) and elemental analysis (expressed in the atomic weight percent) using dispersive X-ray spectroscopy. Bars are indicated.

Figure 10.

Variation of (a) the average zeta potential (ζ) and (b) the mean hydrodynamic diameter (d) of suspended fungal spores with copper cation concentration (cCu / mol dm-3).

Figure 10.

Variation of (a) the average zeta potential (ζ) and (b) the mean hydrodynamic diameter (d) of suspended fungal spores with copper cation concentration (cCu / mol dm-3).

Figure 11.

Length of B. cinerea germ tubes after incubation for 18 hours in (a) control and (b) with copper alginate microspheres (Sample 3) at 20x magnification.

Figure 11.

Length of B. cinerea germ tubes after incubation for 18 hours in (a) control and (b) with copper alginate microspheres (Sample 3) at 20x magnification.

Figure 12.

(a) The control with P. ramorum and rhododendron leaves and (b) microphotograph of P. ramorum mycelium (20x magnification).

Figure 12.

(a) The control with P. ramorum and rhododendron leaves and (b) microphotograph of P. ramorum mycelium (20x magnification).

Figure 13.

Leaves of Rhododendron sp. (a) incubated for 7 days in water (control) and (b) with Samples 1, 2 and 3.

Figure 13.

Leaves of Rhododendron sp. (a) incubated for 7 days in water (control) and (b) with Samples 1, 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Surface roughness values determined for copper alginate microspheres prepared at initial Cu2+ concentration: 8 mmol dm-3 (Sample 1), 12 mmol dm-3 (Sample 2) and 16 mmol dm-3 (Sample 3); average roughness (Ra), root mean square of roughness (Rq).

Table 1.

Surface roughness values determined for copper alginate microspheres prepared at initial Cu2+ concentration: 8 mmol dm-3 (Sample 1), 12 mmol dm-3 (Sample 2) and 16 mmol dm-3 (Sample 3); average roughness (Ra), root mean square of roughness (Rq).

| ALG/Cu |

Ra / nm |

Rq / nm |

| Sample 1 |

23.89 |

29.45 |

| Sample 2 |

18.04 |

20.68 |

| Sample 3 |

3.99 |

5.44 |

Table 2.