1. Introduction

Green leaf volatiles (GLV) are a group of plant compounds that are typically associated with damage. Most people have experienced these molecules when mowing their lawns and recognize them as the typical “green” smell of plants. For more than 20 years now GLV have come to our attention as volatile signals within and between plants that communicate damage, usually caused by insect herbivores, but also by microbial infections [

1]. In doing so, GLV were found to not only provide immediate protection by activating defensive measures, but also to prepare or prime receiver plants against the threat of impending damage [

2,

3]. Generally, priming may initially trigger only a minor part of a defence response which then leads to an increase in the plant’s ability to defend itself against future antagonists (for example herbivores or pathogens) resulting in a faster, stronger, or more enduring response when actually being attacked [

4]. Fittingly, GLV have their own defense-related biological activity, which is however considered to be rather weak when compared to responses signaled for example by jasmonic acid, which is the major defense hormone that regulates responses to herbivory and necrotrophic pathogens. Nonetheless, defense priming by GLV appears to be strongly connected to the jasmonate pathway in that signaling through it becomes more intense [

2,

3]. Still, little is known about how defense priming actually works. It seems clear that some memory is conserved after the first exposure to a priming agent including the accumulation of mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPK) that remain inactive until triggered by a threat, or epigenetic changes [

4]. However, with regard to priming by GLV no such mechnisms have been reported with sufficient evidence to accept them as possible regulators of priming.

While most reports on GLV in the past have focused on their role in mediating biotic interactions, GLV have more recently been found to provide protection to receiver plants against abiotic stresses, either directly or by priming for them. This included protection against various stresses including cold, drought, salt, and high light. Still, very little is known about the mechanisms by which GLV act in mediating abiotic stress protection. In this review I will therefore summarize GLV-induced protective activities related to abiotic stresses that are signaled by this group of compounds and provide some insight into potential mechanisms by which they may achieve this .

2. Green Leaf Volatiles and Abiotic Stress

The Biosynthesis of Green Leaf Volatiles

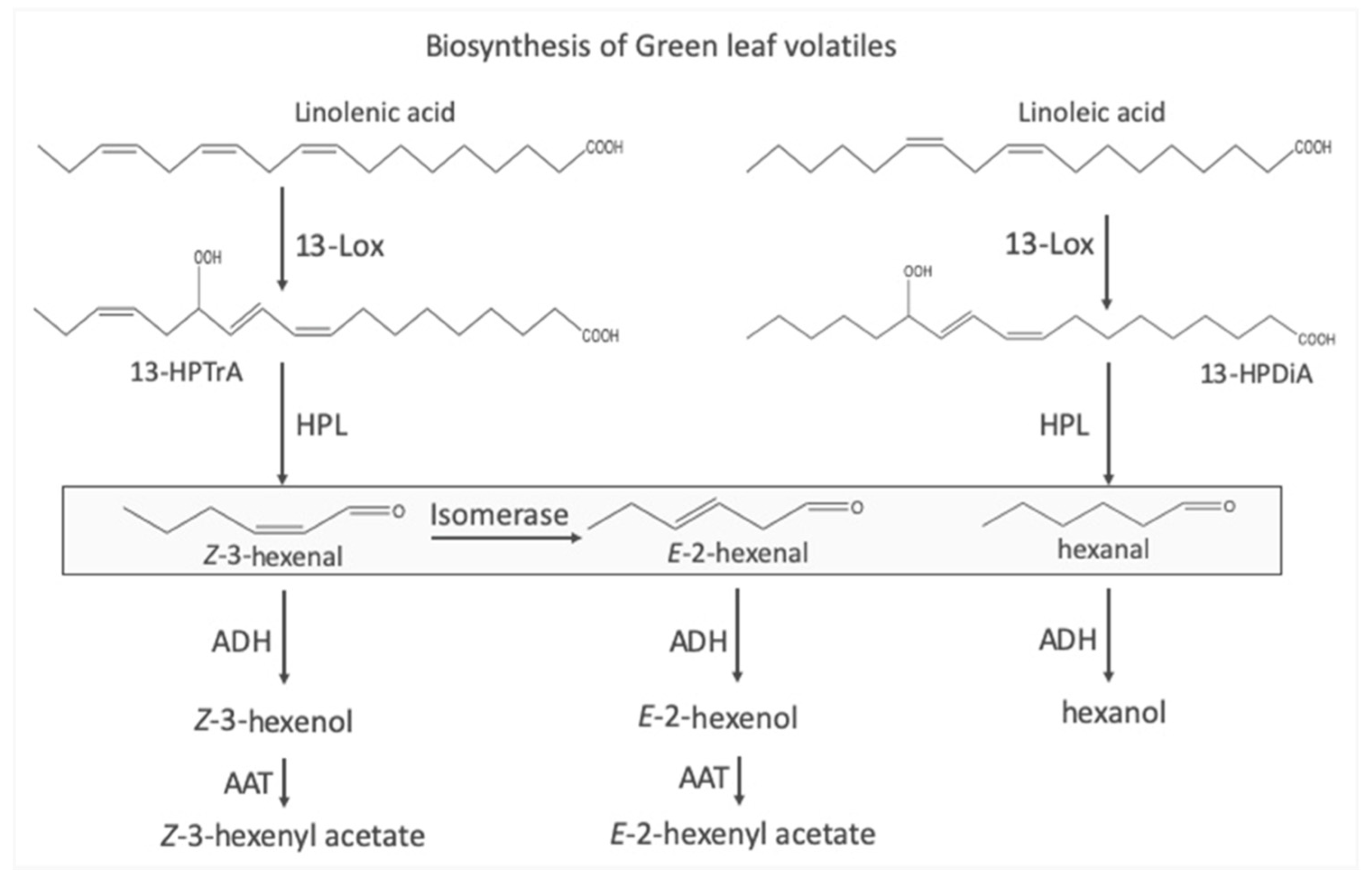

The biosynthesis of GLV is rather straight-forward starting mainly with linolenic acid, either in its free form, but also as part of typical membrane lipids (

Figure 1) [

5,

6]. In a first step a lipoxygenase (LOX) inserts molecular oxygen at position 13 of the fatty acid. A hydroperoxide lyase (HPL) then cleaves the fatty acid into a 6-carbon compound, Z-3-hexenal (Z3al), and a 12-carbon unit, that, after a minor conversion, results in traumatin, a molecule that has been recognized as a wound hormone capable of inducing callus formation [

7]. The 6-carbon unit Z3al is then reduced to its corresponding alcohol (Z-3-hexenol (Z3ol)), which can then be further modified into various esters, mostly into Z-3-hexenyl acetate (Z3ac). Additionally, some plants also have an isomerase that can quickly convert Z3al into E-2-hexenal (E2al) [

8,

9], which can also be transformed into the corresponding E-2- alcohol and esters. While LOX and HPL are commonly localized in chloroplasts, all other enzymes including the isomerase are cytoplasmic. However, upon damage LOX and HPL become activated resulting in the rapid production of Z3al. If cells contain an isomerase, it will also become highly active in the damaged tissue and almost instantly transforms Z3al into E2al. In contrast to these initial steps of GLV biosynthesis, all other reactions require intact cells, which take up the aldehydes and transform them into the corresponding alcohols and esters [

10].

Plants can produce significant quantities of GLV within seconds to minutes after damage, some up to almost 100µg per gram fresh weight [

1,

11]. This substantial and rapid production makes them ideal volatile signaling molecules for either distant parts of the same plant or other plants in the vicinity. While little is known about how exactly Z3al is made in damaged tissue and what regulates the process, we found that even at temperatures far below 0 ºC damaged plant tissues can still produce significant amounts of Z3al under those conditions [

12], while the alcohols and esters are barely detectable mainly because most cells under these conditions have died and can no longer produce these compounds. However, while basically all plants produce GLV in various quantities and qualities upon damage and other treatments, most experiments to date have been done by using pure chemicals that are commercially available, which allows for a more controlled application of these volatiles compounds. The experimental risk here is that the concentrations used may not correlate with what can be found in nature and may produce artifacts. Often, nano- to low micromolar concentrations have been found to sufficiently signal GLV activities. Yet, plants may also experience much higher concentrations upon damage, particularly in the immediate vicinity of the damaged tissue [

2,

10]. It is therefore often impossible to assess the biological activities of these compounds in context with high concentrations being experienced locally, but low concentrations serving as a volatile signal over relatively long distances.

Nonetheless, signaling pathways related to GLV activities are currently being elucidated at various levels. Exposure to GLV for example can cause rapid changes in membrane potentials and cytosolic Ca

2+ concentrations [

13,

14]. It has been argued that GLV themselve cause this depolarization directly due to their hydrophobic character and potential interaction with membranes. However, the distinct set of genes that are induced by GLV and the specificity of the primed responses argues for a more regulated signaling pathway. However, since no receptor has been identified to date, neither mechanism can be excluded.

It further appears that Z3ol is the major biologically active form of GLV [

15]. In a series of experiments performed by Cofer et al. it was shown that after mutating several enzymes involved in the hydrolyzation of GLV esters like Z3ac, the overall activity of these compounds was dramatically reduced, clearly pointing towards Z3ol as the main active molecule. Furthermore, certain GLV seem to activate a MAP kinase signaling pathway in tomato [

16]. Interestingly, the same MAP kinase pathway is normally used after pathogen infection. In support of these findings we found in a microarray study that one MAP kinase was significantly induced in maize plants treated with Z3ol, suggesting that it might be a GLV-specific response [

17]. Yet, it is still unclear if this is a common signaling pathway that is recruited by GLV or if and what other signaling pathways might be involved in regulating responses to these compounds. The activation of the MAP kinase pathway could however provide a link to the priming responses and the associated memory effects as described above [

4], a hypothesis that still needs to be tested, though.

Green Leaf Volatiles in the Atmosphere

As mentioned before, the bioactive roles of GLV have mostly been studied in the context of plant-insect and plant-pathogen interactions, both of which were also shown to cause the release of significant quantities of GLV not only from the damaged tissues, but also from undamaged parts of the same plant [

1,

2,

18]. It was further found that treatment of plants with GLV often prepared or primed them against the impending threat resulting in a stronger and/or faster response when actually attacked [

2,

3,

19,

20,

21,

22]. This led to the assumption that GLV have mainly a role in the defense against biotic threats. However, in recent years several reports showed the potential for GLV also being involved in regulating abiotic stresses. Initial reports came from studies investigating the lower atmosphere of the earth. There, large quantities of so-called biogenic compounds were detected and their effect on the chemistry of the atmosphere studied [

23,

24]. While the majority of these biogenic volatile compounds were found to be isoprene-related, which are usually emitted in large quantities under heat and high light stress, where they provide cooling as well as help in the recovery of photosynthetic performance, significant amounts of GLV were also detected. Since it is unlikely that herbivory or pathogen infections are the sole cause of the presence of GLV in the atmosphere, other factors like grass harvesting for hay in agriculture as well as abiotic stresses need to be taken into consideration. Proof of the latter came for example from a study by Karl et al. [

25] and Jardine et al. [

26]. Karl et al. [

25] found increased GLV levels in frost-damaged meadows in the alps with Z3al being the major compound. Jardine et al. [

26] analyzed the composition of the air surrounding the canopy region of rain forests in South America. The authors not only detected large quantities of GLV, but also found a clear correlation between the amount of GLV and abiotic stresses like drought and heat and concluded that atmospheric GLV could be used as a chemical stress sensor. Similar results were provided by Turan et al. [

27] when they investigated the effects of heat on tobacco leaves. When plants were exposed to 52 ºC they produced large quantities of E2al and Z3ol, but very few terpenes. This production of GLV under heat stress indicates that some kind of membrane damage or at least disturbance occurs resulting in the activation of enzymes in their biosynthetic pathway. Since Z3ol was among the detected compounds it can also be concluded that even at those high temperatures intact cells are still abundant and can convert the aldehydes into the alcohols. Based on these clear correlations between abiotic stresses and GLV release, it can be assumed that there should also be a functional connection. However, at the time little was known about how GLV might contribute to the protection against these stresses.

Green Leaf Volatiles and Cold Stress

Cold stress poses a serious threat to plants. While it is often a seasonal issue, it can still affect plants in regions closer to the poles or at higher altitudes even during the summer. However, the highest risk for plants to experience cold stress is usually during spring time in temperate climates, when they germinate, and in the fall, when they are usually harvested. Cold stress can cause significant changes in the general physiology of plants. Cold stress may generally reduce enzyme activities, can cause cell membrane damage through altered membrane fluidity and lipid composition, decreases water potential, reduce ATP supply, and may bring about imbalanced ion distribution and solute leakage (Theocharis et al. [

28]. This does often result in reduced growth and yield. It is therefore important for plants to have mechanisms in place that help to prevent severe consequences of this stress.

Karl et al. [

25], as described above, provided first insight that GLV might be a part of such a strategy since cold-damaged plant emitted significant quantities of these compounds. Likewise, Copolovici et al. [

29] found that cold stress caused the release of large quantities of GLV in cold-stressed, but also in heat-stressed tomato (

Solanum lycopersicum) plant. Similar to Jardine et al. [

26], the authors proposed the use of these volatile organic compounds as indicators to characterize the severity of the stress. Yet again, no studies were performed that would test for a protective role of GLV under those conditions.

In 2013 we published a microarray study on the effects of Z3ol in particular on general gene expression in maize [

17]. We focused on early events and identified distinct expression patterns, many of which were likely related to defense reactions to insect herbivores. Unfortunately, at the time many genes on the microarray were still unknown or mislabeled (about 40%). Later, we identified several genes that were typically associated with water stress in plants including dehydrins, low temperature inducible protein and several others [

30]. This pointed towards a potential role of GLV in protecting cellular integrity since these types of proteins are usually involved in stabilizing cell structures including membranes. When further analyzing the effects of GLV on cold stress protection, we found that the expression of the identified protective genes was not only induced by GLV but also that their expression levels were primed when they were placed in the cold about 2h after GLV treatment. This resulted in significantly reduced ion leakage [

12,

31], less damage, and a growth spurt in the days after the cold stress treatment. Aside from providing immeditate protection this also indicated an effect of GLV on the general physiology of the plant, which allowed it to compensate for a loss of growth during cold. We also found that maize plants do still produce GLV, in particular Z3al, at temperatures well below 0 ºC [

12]. Furthermore, Z3al was able to increase transcript accumulation of those protective genes even when applied during cold stress [

12]. This proved that GLV can protect plants against cold stress even when perceived during a cold episode and also provides a potential mechanism by which this might be achieved, i.e. the activation of cell protective proteins and thus, the maintenance of cellular integrity. This is essential since it allows cells to continue to function properly even under potentially damaging stress conditions.

Green Leaf Volatiles and Drought Stress

Drought is defined as an absence of water (

https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/monitoring/dyk/drought-definition). However, an absence or shortage of water can also be the result of high salt concentrations or the abundance of other water-capturing chemicals, all of which result in a dramatic change in the water potential of plants. While early effects of drought and salt stress are very similar, both stresses act through distinct signaling pathways. Additionally, salt may also have a toxic ion effect and can lead to nutritional imbalances in plants [

32,

33]. This makes it more difficult for the plant to maintain a constant transpirational stream, which can lead to overheating of leaves, but also to a reduced uptake of nutrients. Consequently, plants exposed to drought grow less and provide much lower yield. Water scarcity is therefore one of the most pressing issues when growing plants in a natural environment or in an agricultural setting.

The potential role of GLV in drought stress responses was initially provided by Jardine et al. [

26] through their analysis of the atmosphere of the forest canopy in the rain forest, in which they found a clear correlation between drought, temperature, and GLV. This was a first clear indication that GLV may play a role in the regulation of drought and heat stress in a natural system. However, at the time it was unclear if there might also be a protective role that GLV play in this context since studies in a natural system are difficult to perform due to the myriad of other environmental factors that may interfere. In a related study by Catola et al. [

34] it was further shown that drought stress affects the capacity to produce GLV in leaves of the pomegranate (

Punica granatum L.), further supporting an involvement of GLV in the response to drought stress. Yet again, no further studies were performed to evaluate a potential protective role of GLV.

However, evidence for GLV playing an active part in the protection against drought-related stresses came from a study by Yamauchi et al. [

35]. By investigating the potential for activating gene expression they tested an array of reactive leaf volatiles in a microarray assay on Arabidopsis. While the focus of the study was on reactive α, β-unsaturated carbonyls, they identified E2al as a particularly effective inducer of typical abiotic stress-related genes including those that protect against drought and salt, but also heat and cold. At the same time Z3al appeared to be quite inactive and did not show any significant induction of abiotic stress-related gene expression, which could however be a species-specific result. While this did not answer the question of whether or not GLV do actually provide protection against drought and salt stress in particular, a study by Tian et al. [

36] showed that priming with Z-3-hexenyl acetate enhanced salinity stress tolerance in peanut (

Arachis hypogaea L.). As a result they found positive effects on photosynthesis, higher water content, increased growth, and increased activity of antioxidant proteins. While this broad spectrum of protectionist measures may surprise, it actually fits into the overall picture of activities provided by GLV that have been shown for biotic stress responses [

3].

A similar study investigated the effects of Z3ol on hyperosmotic stress tolerance in

Camellia sinensis [

37]. As above, a multitude of effects were found ranging from regulating stomatal conductance, decreases in malonyl dialdehyde as an indicator of lipid peroxidation, accumulation of abscisic acid and proline, and typical stress-related gene expression. The activation of ABA and proline in particular is interesting since both are essential responses to hyperosmotic stress: ABA by acting as the major regulator of water stresses [

38] and proline as an important protector of cellular integrity [

39]. The involvement of ABA as a mediator of Z3ol-induced protection against drought and cold was further confirmed by Jin et al [

40]. They showed that Z3ol activated the glycosylation of ABA through expression of a specific glycosyl transferase. This allows ABA-glucose conjugates to be stored in the vacuole, from where they can be easily reactivated upon cold and drought stress by a glucosidase. While this provides an elegant system that helps to explain some of the biological activities of GLV (here: Z3ol), it still needs to be confirmed in other plants. Furthermore, while Z3ol was shown to be the active compound in this study, other GLV, in particular Z3al as the one compound that is instantly produced by damage including cold, also need to be tested for their specific activity towards the activation of ABA-mediated signaling as a key element in this process.

Altogether, these results clearly showed that GLV are not only released upon drought stress in significant quantities, but can also provide significant protection. Furthermore, these experimental results provide a potential mechanism by which GLV may activate these processes with ABA, the major regulatory plant hormone for water stresses, being a central target.

Green Leaf Volatiles and Photosynthesis

Light is a determining factor in the life of plants. It is the predominant energy source that is used by plants and other photosynthetically active organisms, which are transforming light from a physical power into energy-rich molecules that are essential for the vast majority of living things on earth. For plants light also serves as a signal that has a significant impact on growth in an effort to obtain a perfect position for light harvesting. However, light can also be too powerful and under those conditions, plants may sustain damage by the high energy levels that are contained in the radiation. This is, among other consequences, extremely challenging for the actual photosynthesis reaction, in particular the events that occur in photosystem II (PSII). There, the photolysis of water represents one of the main events during photosynthesis resulting in the production of electrons, protons, and eventually oxygen. Under normal light conditions this is a well-controlled process. But when light intensities increase, oxygen radicals are produced, which can cause significant harm to the whole photosystem, but also other parts of the chloroplast. And it is this process in which GLV appear to interfere by regulating the status of PSII in particular.

First indications to support a role of GLV in photosynthesis came from a study by Charron et al. [

41]. They found that increased photosynthetic photon flux and the length of the photoperiod would cause an increase of GLV production and release in lettuce. While this was mainly put in the context of growing plants in controlled environments, it was nonetheless pointing towards GLV being directly linked to light stress. Further proof came from a study on bacterial photosynthesis. Mimuro et al. [

42] investigated the effects of 1-hexanol on the optical properties of the base plate and the energy transfer in

Chloroflexus aurantiacus. In this system it was found that adding 1-hexanol caused a suppressed flux of energy from the baseplate of the chlorosome to the photosynthetic elements located in the adhering plasma membrane section. While it is still unclear whether or not bacteria can produce GLV, the results nonetheless provided evidence that these compounds can have an effect on photosynthetic reactions. Furthermore, considering that this kind of photosynthetic microbe might represent an ancestorial type of what may have eventually ended up as a chloroplast in plants, mechanisms to protect or at least alter the system may also have been already abundant.

Negative alterations of photosynthesis were further investigated by Matsui et al. [

10]. While studying the metabolism of GLV they identified key mechanisms of the biochemical pathway. As described above, the aldehydes are mainly produced in damaged tissue, whereas the corresponding alcohols and esters require intact cells to be made. Aside from identifying these mechanisms, they further investigated the toxicity of various GLV including Z3al, E2al, and Z3ol, and found that plants exposed to the compounds as pure chemicals showed a significant impact on photosynthesis with the aldehydes being much more active than the corresponding alcohol. Similar results were obtained by Tanaka et al. [

43]. Together, this led to the conclusion that plants cells have an intrinsic ability to detoxify the much more reactive aldehyde GLV into the less harmful alcohols and esters, which in turn appear to serve as the actual signaling molecules that regulate all processes attributed to GLV [

15]. At the same time plants avoid the toxic effects of the aldehydes. However, a new light was shed on this issue when Savchenko et al. [

44] studied the effect of GLV on photosynthesis. By using HPL overexpressing lines in Arabidopsis, they discovered that GLV play a major role in the protection of PSII under high light conditions by observing lower rate constants of PSII photoinhibition and higher rate constants of recovery. Furthermore, the degradation of proteins (in particular D1, but also others) during photoinhibition was significantly reduced, allowing for a more speedy recovery. Further experiments on isolated thylakoid membranes confirmed these results. In contrast to GLV, the application of other oxylipins including linolenic acid, phytodienoic acid, and jasmonates had the opposite effects, further solidifying the specificity of GLV effects on PSII. This important feature of GLV may also explain why this biochemical system is localized in chloroplasts, more specifically in the thylakoids. Reducing the uncontrolled production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) may be key in the protection of plants cells under extreme light conditions and may explain why GLV have a negative impact on photosynthesis, which, while considered toxic in the past, is actually helping to avoid damage in leaf cells.

However, little is known about the actual mechanisms that are activated by GLV to protect against high light. Further studies in the area of high light protection in particular are needed to identify these mechanisms, which may in turn further help to explain the diverse and complex roles GLV play in plants.

3. Future Perspectives

The definition of GLV as the plant’s multifunctional weapon [

3] was created at a time when mainly its defensive functions were recognized. This view has now been expanded by adding a multitude of abiotic stresses that are also covered by GLV, as described herein. This extreme multifunctionality raises the question of how these compounds can be utilized to better plant protection against biotic and abiotic stresses. A summary of approaches towards the protection against biotic stresses by volatile organic compounds in general has been provided by Wang et al. [

45]. Two major paths were outlined, one using intercropping with sentinel plants, and the other using pure chemicals to help to protect plants. These approaches could also be chosen for using GLV as protectors against abiotic stresses. Intercropping would require a sentinel plant that should be more sensitive to certain abiotic stresses, in particular drought and cold, and should produce GLV upon being exposed to those stresses in sufficient quantities to protect the main crop. At the same time these sentinel plants should not take away too many of the nutrients and idealy should continue to grow even after suffering damage to allow for longer-term protection. Alternatively, pure chemicals like Z3ol or Z3ac could be deployed over fields at critical times and assist so in the protection against relevant abiotic stresses. However, there are several issues here that need to be addressed. One is costs, which could be significant. Another issue lies in the fact that these compounds are volatile and may dissipate very quickly, making it necessary to repeat the application regularly. At this time we don’t know how long a protective or priming effect against certain stresses remains active within a certain plant species, but this would be necessary information that determines how often such a treatment would have to be repeated to be effective. One solution could be the development of a slow-release mechanism for GLV or to produce a conjugate that can be taken up by the plant without dissipating as a volatile into the atmosphere. Another issue is that while GLV can protect against a variety of biotic stresses, they may very well interfere with alternative defense signaling pathways. As mentioned before, GLV appear to act through the jasmonate signaling pathway, and in doing so protect against many insect herbivores and necrotrophic pathogens. However, this does for example allow biotrophic pahogens to infect plants and thrive. For biotrophic pathogens, salicylic acid is the major defense regulator. However, its activity is down-regulated by the jasmonate pathway and vice-versa [

46]. These interactions need to be fully understood before treatments that activate one or the other pathway might be deployed. It also necessitates more studies on how GLV may interfere with other signaling pathways to avoid any negative side effects with significant impact on growth and yield. To date no such study has been performed in the area of GLV and abiotic stress responses.

Another path forward could lie in the molecular manipulation of GLV production and sensing. While we know most of the genes involved in the biosynthesis, we are still at the beginning of understanding how GLV are being sensed. But even with the biosynthesis we only have a limited understanding of the regulation of the initial steps, in particular after tissue damage, but also regarding the release of GLV from intact tissues. In this context an interesting finding has been the release of a burst of GLV at the onset of darkness. This has been described for several plant species [], but it is yet unknown why plants do this. Also, this GLV burst seems to require a rather quick transition from light to dark. However, exploring and eventually exploiting this phenomenon of potentially self-priming may provide a starting point for future manipulations resulting in a better protection of plants.

We still know very little about how plants perceive GLV as signals and exactly how they transduce it into a physiological response. Is it just the physical perturbation of membranes or are specific receptors involved? These are questions for which we don’t have any answers at this time. Once resolved, this information could provide more targeted approaches for manipulation. Increasing the sensitivity of plants for GLV might be one promising line of exploitation. Overexpressing key enzymes might be one way, but also providing the substrates for the reaction (i.e. poly-unsaturated fatty acids) may help to boost the production of these compounds. However, as mentioned above, manipulating one signaling pathway may have severe consequences for others and must therefore carefully studies with consideration of the whole plant physiology. For example, only a few studies so far have looked into the costs of GLV-activated responses [

47,

48,

49]. Surprisingly, the application of these compounds has often resulted in an increase of growth [

12,

31,

47,

48,

49]. Should this be confirmed for other plants species and stresses, it might very well justify more thorough investigations into the feasabilty of using GLV as an almost universal protection system, that would not have negative effects on other physiological responses.

However, our knowledge regarding GLV regulation is still very limited, not only with regard to the enzymes involved, but also when it comes to how different plant species regulate the process of producing and sensing these compounds. This becomes extremely clear when we look at the number of plants that have been used to provide the results presented herein. Aside from Arabidopsis, less than 10 different plant species have been used to study the effects of GLV on abiotic stress protection. Furthermore, the experimental approaches were very different depending on the goal of the respective study. I believe that a more comprehensive and coordinated approach is indeed necessary to better understand how GLV affect plants on a global scale.

4. Summary and Conclusions

While the number of publications on the topic of GLV and abiotic stress protection is far exceeded by those on GLV and biotic stresses, it cannot be denied that GLV can provide significant protection through yet to be identified signaling pathways. But even with the limited number of publications on the topic it is astounding how broad GLV can protect against a great variety of abiotic stresses. If we compare this with other plant signaling compounds including hormones like jasmonic acid, abscisic acid, salicylic acid and many others it becomes obvious how limited these are in the regulation of protective functions when compared to GLV. This broad protection makes GLV somewhat unique within the regulatory network of plant stress responses.

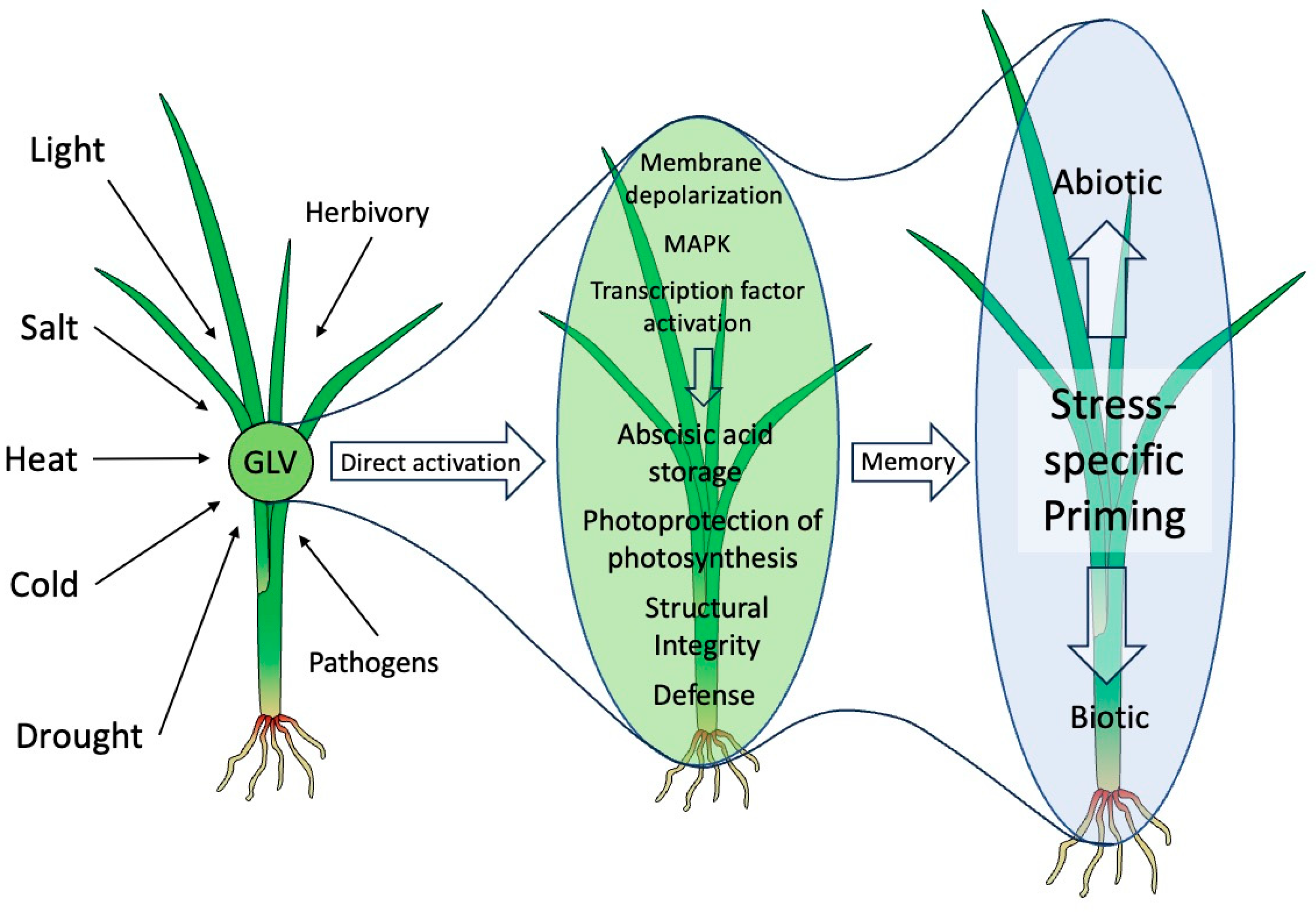

To best describe the protective roles of GLV, one has to look at what is causing damage to plants. Damage in most instances is physical and thus directly linked to water loss, which may lay at the core of GLV activities. But it clearly goes beyond that when they also protect against herbivores, pathogens, drought, cold, high light, salt, and other damaging stresses. Also, while they protect against those stresses, they are also often released by the same stresses they protect against, thereby potentially providing protection to other parts of the same plant or even other plants nearby, either by directly activating protective responses or by priming for those. This will result in a faster and/or stronger reaction should the stress actually occur. Surprisingly, all this is done with minor investments, making this a very low-cost investment on the plants side. A summary of GLV activities is shown in

Figure 2.

GLV have been labelled ‘the plants multifunctional weapon” in the past based on their multifaceted biological activities against biotic stresses in particular [

3]. It is however obvious from the findings summarized in here that we have to expand this characterization to include the protection against abiotic stresses as well. I would therefore also not describe GLV as new players in this context, but rather as very old ones, that just needs to be further studied to reveal their full potential in regulating a multitude of stress responses in plants.

To conclude, the role of GLV seem to lay in in the protection of plants against all those stresses, biotic and abiotic, that can cause damage in the widest meaning of this word. However, how these complex activities are regulated by these compounds is mostly still unknown. But the potential of GLV in protecting plants on such a broad scale are definitely worthy of further investigations.

Author Contributions

J.E. conceptualized and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded in part by USDA, NIFA, grant number 2020-65114- 30767 to JE.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ameye, M.; Allmann, S.; Verwaeren, J.; Smagghe, G.; Haesaert, G.; Schuurink, R.C.; Audenaert, K. Green leaf volatile production by plants: a meta-analysis. New Phytol. 2018, 220, 666–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, K.; Engelberth, J. Green leaf volatiles-the forefront of plant responses against biotic attack. Plant Cell Physiol 2022, 63, 1378–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scala, A.; Allmann, S.; Mirabella, R.; Haring, M.A.; Schuurink, R.C. Green leaf volatiles: A plant’s multifunctional weapon against herbivores and pathogens. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 17781–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westman, S.M.; Kloth, K.J.; Hanson, J.; Kloth, K.J.; Hanson, J.; Ohlsson, A.B.; Albrectsen, B.R. Defence priming in Arabidopsis – a Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep 2019, 9, 13309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatanaka, A. The biogeneration of green odour by green leaves. Phytochemistry 1993, 34, 1201–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K. Green leaf volatiles: Hydroperoxide lyase pathway of oxylipin metabolism. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2006, 9, 274–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmerman, D.C.; Coudron, C.A. Identification of traumatin, a wound hormone, as 12-oxo-trans-10-dodecenoic acid. Plant Physiol 1979, 63, 536–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunishima, M.; Yamauchi, Y.; Mizutani, M.; Kuse, M.; Takikawa, H.; Sugimoto, Y. Identification of (Z)-3:(E)-2-hexenal isomerases essential to the production of the leaf aldehyde in plants. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 14023–14033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spyropoulou, E.A.; Dekker, H.L.; Steemers, L.; van Maarseveen, J.H.; de Koster, C.G.; Haring, M.A.; Schuurink, R.C.; Allmann, S. Identification and characterization of (3Z):(2E)-hexenal isomerases from cucumber. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Mano, J.; Ozawa, R.; Takabayashi, J. Differential metabolism of green leaf volatiles in injured and intact parts of a wounded leaf meet distinct ecophysiological requirements. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e36433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberth, J.; Engelberth, M. Variability in the capacity to produce damage-induced aldehyde green leaf volatiles among different plant species provides novel insights into biosynthetic diversity. Plants 2020, 9, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelberth, M.; Selman, S.M.; Engelberth, J. In-cold exposure to Z-3-hexenal provides protection against ongoing cold stress in Zea mays. Plants 2019, 8, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebelo, S.A.; Matsui, K.; Ozawa, R.; Maffei, M.E. Plasma membrane potential depolarization and cytosolic calcium flux are early events involved in tomato (Solanum lycopersicon) plant-to-plant communication. Plant Sci 2012, 196, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aratani, Y.; Uemura, T.; Hagihara, T.; Matsui, K.; Toyota, M. Green leaf volatile sensory calcium transduction in Arabidopsis. Nat Commun 2023, 14, 6236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cofer, T.M.; Erb, M.; Tumlinson, J.H. The Arabidopsis thaliana carboxylesterase AtCXE12 converts volatile (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate to (Z)-3-hexenol. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tanarsuwongkul, S.; Fisher, K.W.; Mullis, B.T.; Negi, H.; Roberts, J.; Tomlin, F.; Wang, Q.; Stratmann, J.W. Green leaf volatiles co-opt proteins involved in molecular pattern signalling in plant cells. Plant Cell Environ 2024, 47, 928–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberth, J.; Contreras, C.F.; Dalvi, C.; Li, T.; Engelberth, M. Early Transcriptome Analyses of Z-3-Hexenol-Treated Zea mays Revealed Distinct Transcriptional Networks and Anti-Herbivore Defense Potential of Green Leaf Volatiles. PLoS ONE 2012, 8, e77465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röse, U.S.R.; Tumlinson, J.H. Systemic induction of volatile release in cotton: How specific is the signal to herbivory? Planta 2005, 222, 327–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelberth, J.; Alborn, H.T.; Schmelz, E.A.; Tumlinson, J.H. Airborne signals prime plants against herbivore attack. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 1781–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, A.; Halitschke, R.; Diezel, C.; Baldwin, I.T. Priming of plant defense responses in nature by airborne signaling between Artemisia tridentata and Nicotiana attenuata. Oecologia 2006, 148, 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heil, M.; Bueno, J.C. Within-plant signaling by volatiles leads to induction and priming of an indirect plant defense in nature. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 5467–5472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, C.J.; Mescher, M.C.; Dervinis, C.; Davis, J.M.; Carlson, J.E.; De Moraes, C.M. Priming defense genes and metabolites in hybrid poplar by the green leaf volatile cis-3-hexenyl acetate. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laothawornkitkul, J.; Taylor, J.E.; Paul, N.D.; Hewitt, C.N. Biogenic volatiles organic compounds in the earth system. New Phytol 2009, 183, 27–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarang, K.; Rudziński, K.J.; Szmigielski, R. Green Leaf Volatiles in the Atmosphere—Properties, Transformation, and Significance. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karl, T.; Fall, R.; Crutzent, P.J.; Jordan, A.; Lindinger, W. High concentrations of reactive biogenic VOCs at a high altitude in late autumn. Geophys Res Lett 2001, 28, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardine, K.J.; Chambers, J.Q.; Holm, J.; Jardine, A.B.; Fontes, C.G.; Zorzanelli, R.F.; Meyers, K.T.; Fernandez de Souza, V.; Garcia, S.; Giminez, B.O.; et al. Green leaf volatile emissions during high temperature and drought stress in a Central Amazon rainforest. Plants 2015, 4, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turan, S.; Kask, K.; Kanagendran, A.; Li, S.; Anni, R.; Talts, E.; Rasulov, B.; Kannaste, A.; Niinements, U. Lethal heat stress-dependent volatile emissions from tobacco leaves: what happens beyond the thermal edge? J Exp Bot 2019, 70, 5017–5030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theocharis, A.; Clement, C.; Barka, E.A. Physiological and molecular changes in plant growth at low temperatures. Planta 2012, 235, 1091–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Copolovici, L.; Kannaste, A.; Pazouki, L.; Niinemets, U. Emissions of green leaf volatiles and terpenoids from Solanum lycopersicum are quantitatively related to the severity of cold and heat shock treatments. J. Plant Physiol. 2012, 169, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, E.A.; Bailey-Serres, J.; Weretilnyk, E. Response to abiotic stresses. In Biochemistry and Molecular Biology of Plants; Gruissem, W., Buchanan, B.B., Jones, R., Eds.; American Society of Plant Physiologists: Rockville, MA, USA, 2000; pp. 1158–1249. [Google Scholar]

- Cofer, T.M.; Engelberth, M.J.; Engelberth, J. Green leaf volatiles protect maize (Zea mays) seedlings against damage from cold stress. Plant Cell Environ. 2018, 41, 1673–1682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.-K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol 2002, 53, 247–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, H.; Ding, R.; Kang, S.; Du, T.; Tong, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Shukla, M.K. Chapter 3 – Drought, salt, and combined stresses in plants: effects, tolerance mechanisms, and strategies. Adv Agronomy 2023, 178, 107–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catola, S.; Marino, G.; Emiliani, G.; Huseynova, T.; Musayev, M.; Akparov, Z.; Maserti, B.E. Physiological and metabolomic analysis of Punica granatum (L.) under drought stress. Planta 2016, 243, 441–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamauchi, Y.; Kunishima, M.; Mizutani, M.; Sugimotot, Y. Reactive short-chain leaf volatiles act as powerful inducers of abiotic stress-related gene expression. Sci Rep 2015, 5, 8030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, S.; Guo, R.; Zou, X.; Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Zhan, Y.; Ci, D.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Si, T. Priming with the green leaf volatile (Z)-3-hexeny-1-yl acetate enhances salinity stress tolerance in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) seedlings. Front Plant Scie 2019, 10, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, S.; Chen, Q.; Guo, F.; Wang, M.; Zhao, H.; Wang, Y.; Ni, D.; Wang, P. (Z)-3-hexen-1-ol accumulation enhances hyperosmotic stress tolerance in Camellia sinensis. Plant Mol Biol 2020, 103, 287–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, K.; Li, G.-J.; Bressan, R.A.; Song, C.-P.; Zhu, J.-K.; Zhao, Y. Abscisic acid dynamics, signaling, and functions in plants. J Int Plant Biol 2020, 62, 25–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayat, S.; Hayat, Q.; Alyemeni, M.N.; Wani, A.S.; Pichtel, J.; Ahmad, A. Role of proline under changing environments. Plant Signal Behav 2012, 7, 1456–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Zhao, M.; Jing, T.; Wang, J.; Lu, M.; Pan, Y.; Du, W.; Zhao, C.; Bao, Z.; Zhao, W.; Tang, X.; Schwab, W.; Song, C. (Z)-3-hexenol integrates drought and cold stress signaling by activating abscisic acid glucosylation in tea plants. Plant Physiol 2023, 193, 1491–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charron, C.S.; Cantliffe, D.J.; Wheeler, R.M.; Manukian, A.; Heath, R.R. Photosynthetic photon flux, photoperiod, and temperature effects on emissions of (Z)-3-hexenal, (Z)-3-hexenol, and (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate from lettuce. J Am Soc Hortic Sci 1996, 121, 488–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mimuro, M.; Nishimura, Y.; Yamazaki, I.; Kobayashi, M.; Wang, Z.Y.; Nozawa, T.; Shimada, K.; Matsuura, K. Excitation energy transfer in the green photosynthetic bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus: A specific effect of 1-hexenol on the optical properties of baseplate and energy transfer processes. Photosyn Res 1996, 48, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, T.; Ikeda, A.; Shiojiri, K.; Ozawa, R.; Shiki, K.; Nagai-Kunihiro, N.; Fujita, K.; Sugimoto, K.; Yamato, K.T.; Dohra, H.; Ohnishi, T.; Koeduka, T.; Matsui, K. Identification of a hexenal reductase that modulates the composition of green leaf volatiles. Plant Physiol 2018, 178, 552–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savchenko, T.; Yanykin, D.; Khorobrykh, A.; Terentyev, V.; Klimov, V.; Dehesh, K. The hydroperoxide lyase branch of the oxylipin pathway protects against photoinhibition of photosynthesis. Planta 2017, 245, 1179–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M.H.; Rodriguez-Saona, C.; Lavoir, A.-V.; Ninkovic, V.; Shiojiri, K.; Takabayashi, J.; Han, P. 2024 Leveraging air-borne VOC-mediated plant defense priming to optimize Integrated Pest Management. J Pest Sci. [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Tsuda, K. Salicylic acid and jasmonic acid crosstalk in plants. Essays Biochem 2022, 66, 647–656. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Maurya, A.K.; Pazouki, L.; Frost, C.J. Primed seeds with indole and (Z)-3-hexenyl acetate enhances resistance against herbivores and stimulates growth. J Chem Ecol 2022, 48, 441–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelberth, J.; Engelberth, M. The costs of green leaf volatile-induced defense priming: temporal diversity in growth response to mechanical wounding and insect herbivory. Plants 2019, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engelberth, J. Primed to growth: a new role for green leaf volatiles in plant stress responses. Plant Sig Behav 2020, 15, 1701240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).