Submitted:

18 May 2024

Posted:

21 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

- Background

- Problems of defining ‘homelessness’

- Challenges of YEH in EAP and rationale for the review

2.Methods

- Databases and search strategy

- Screening process

- Analysis

3. Results

- Study selection

- Study characteristics

Study designs

Outcome measures

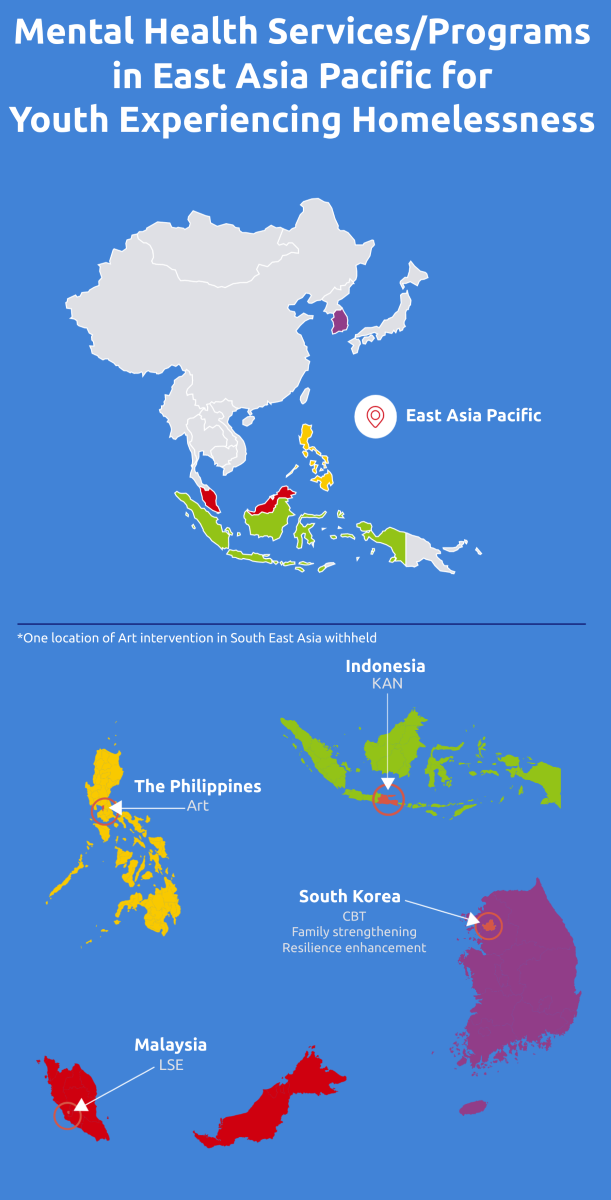

- Mental health interventions/programs

- cognitive behavioural therapy: an intervention that targets negative emotional states and cognitive distortions by developing coping strategies[27];

- life skills education: interventions that equip YEH with essential practical abilities in the real world[69];

- resilience enhancement: an intervention to improve protective factors associated with resilience[70];

- family strengthening: interventions that explicitly target families in the program as a key focus that fosters positive relationships and support networks[71];

4. Discussion

- Exploring mental health interventions and programs

- Art

- CBT

- LSE

- Resilience enhancement

- Family strengthening

- Government interventions/services

- Limitations

- Implications for future research, policy, and practice

Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # |

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 2 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 4–5 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 5 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 5 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 5 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 5–6 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 6 |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 6 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | 6 |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | 8 |

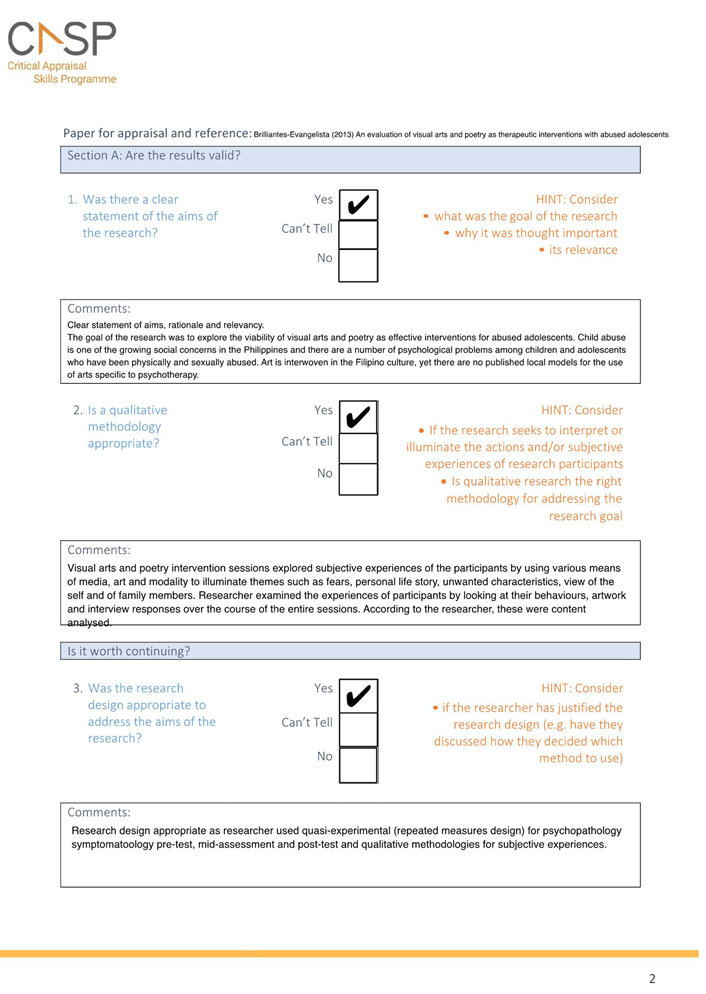

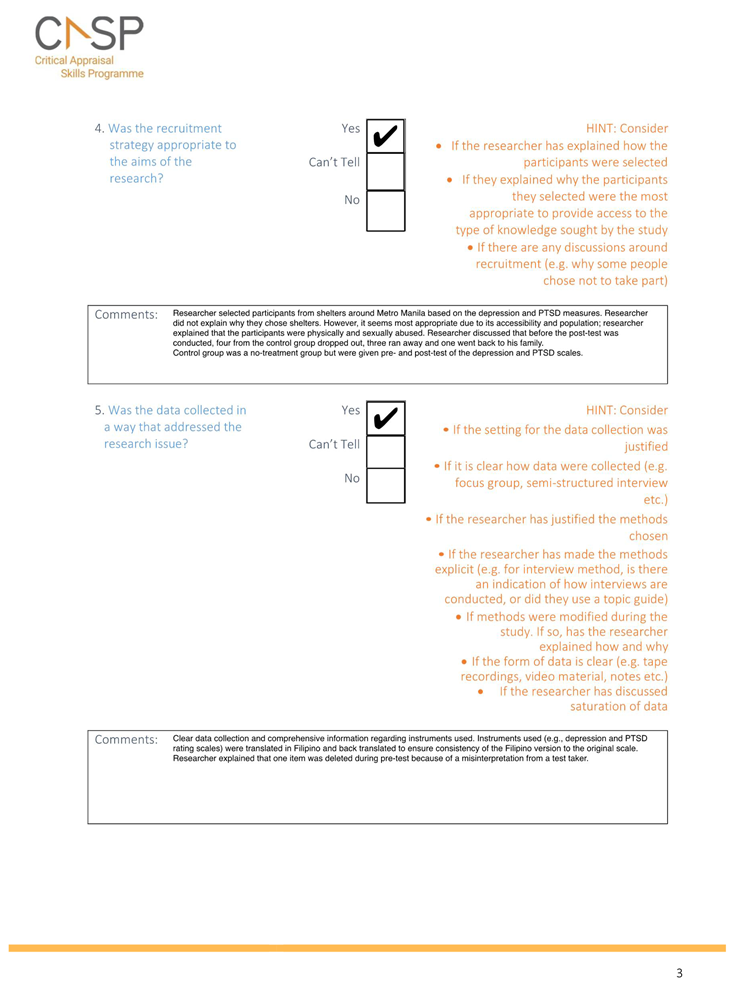

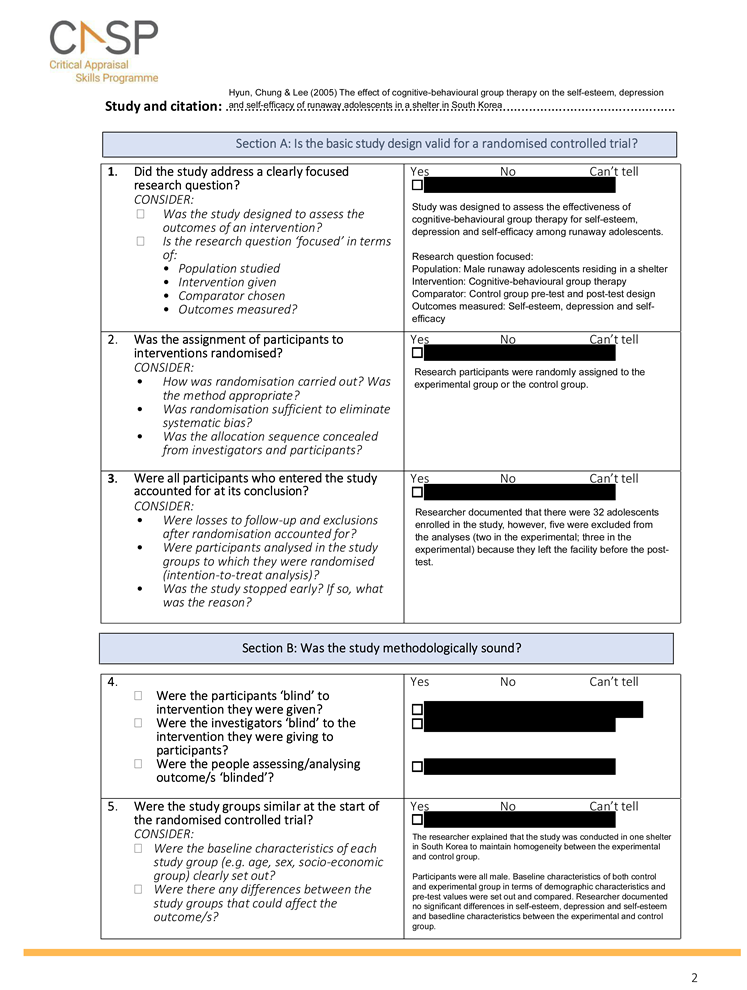

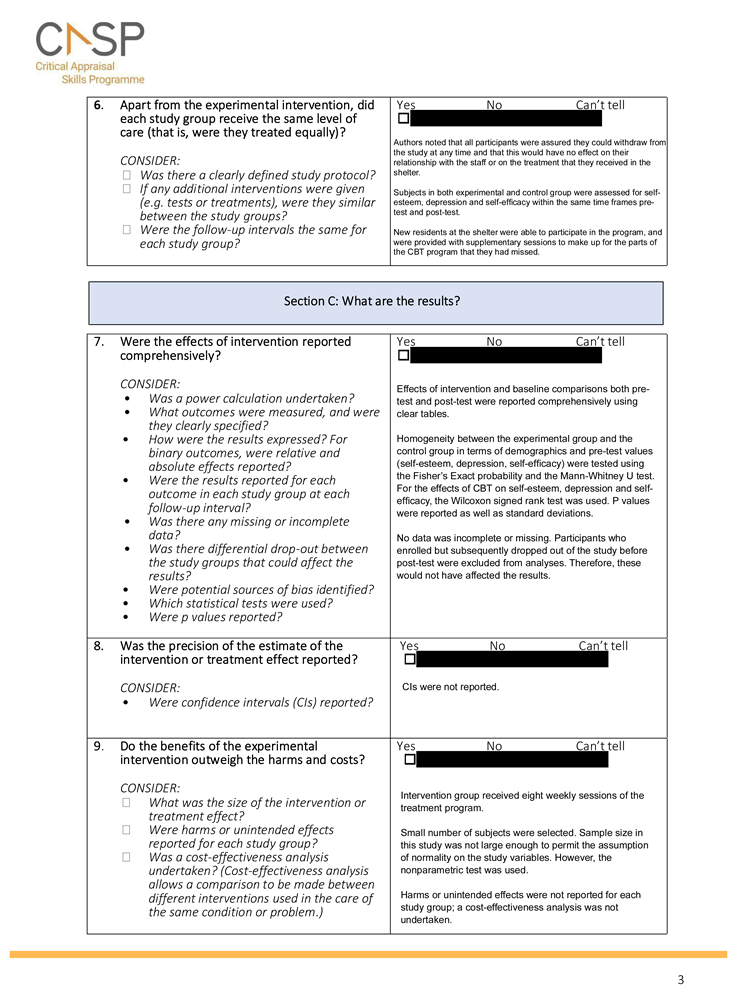

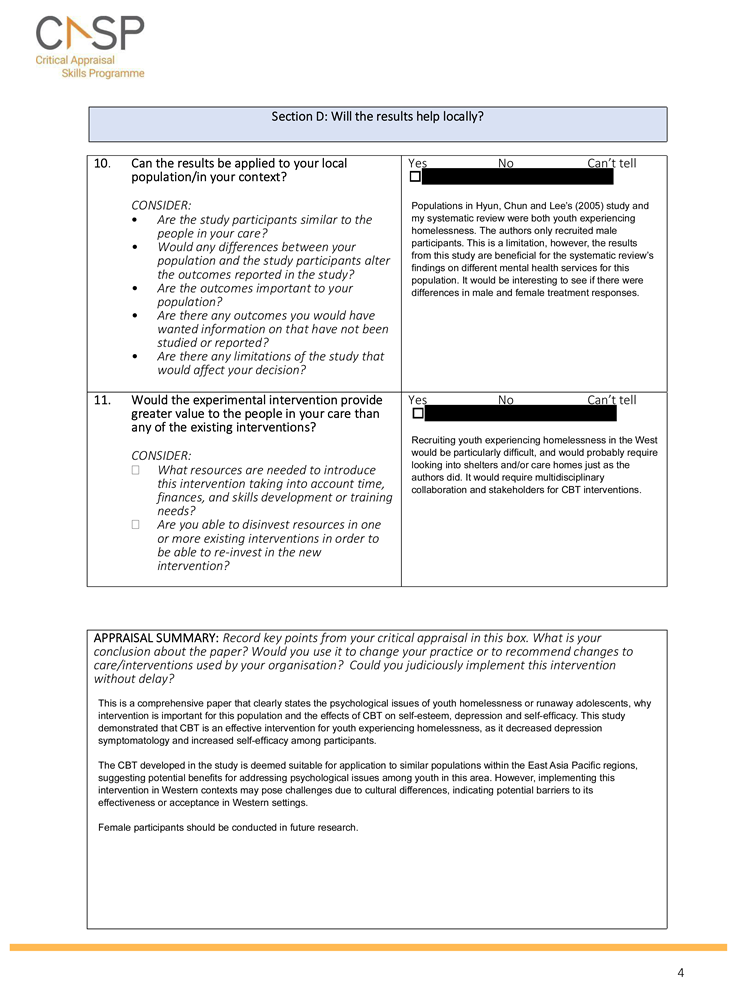

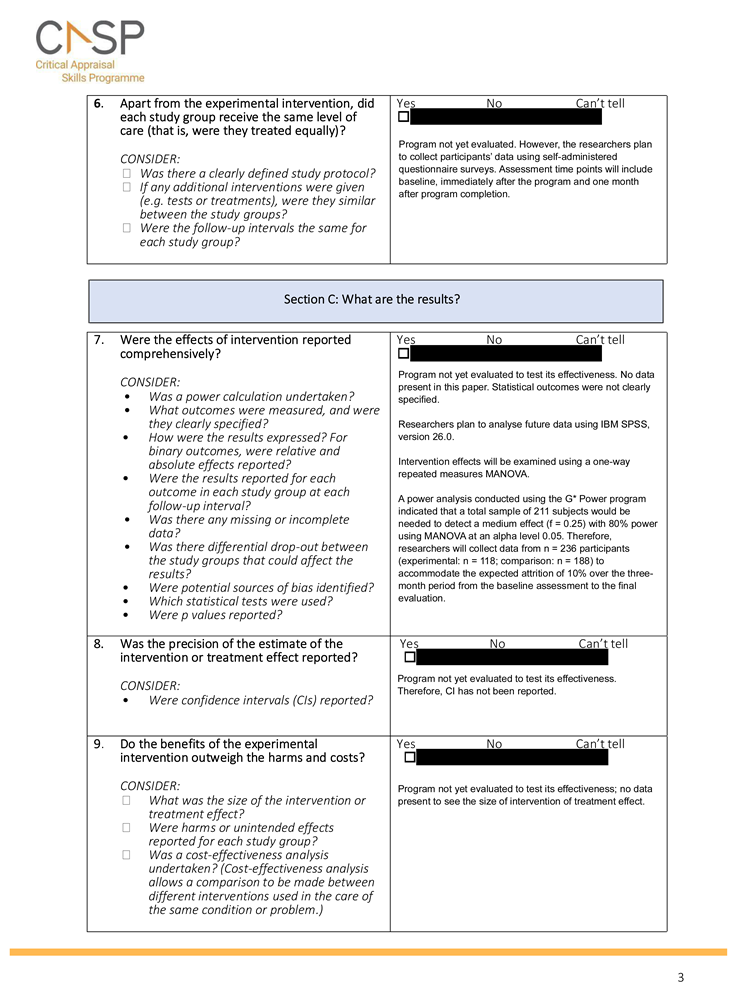

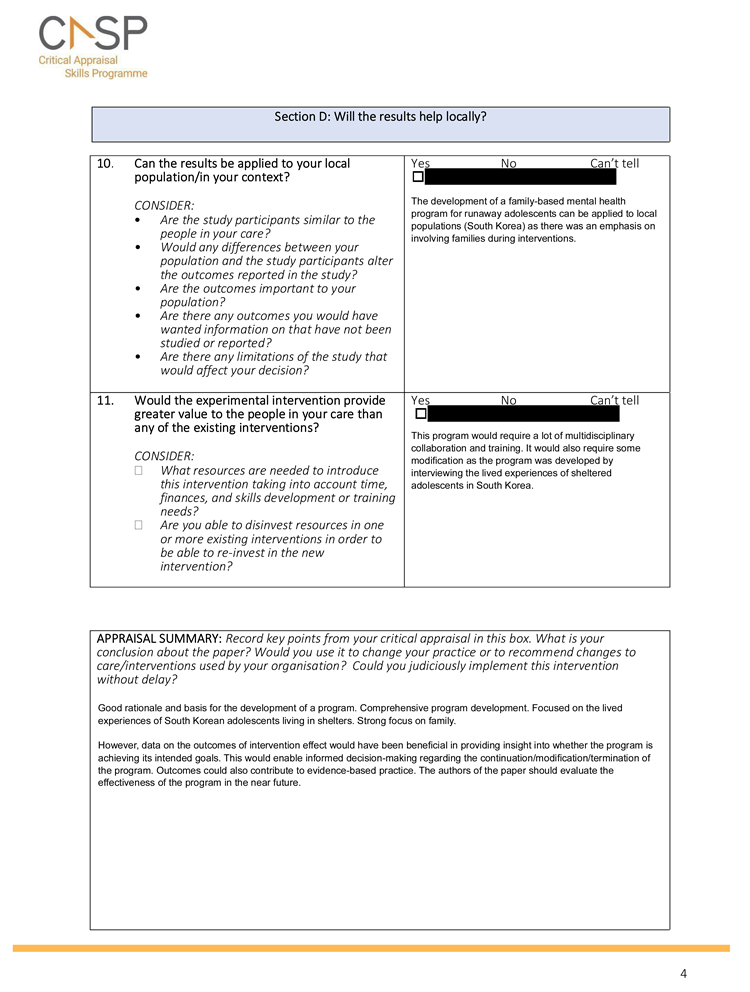

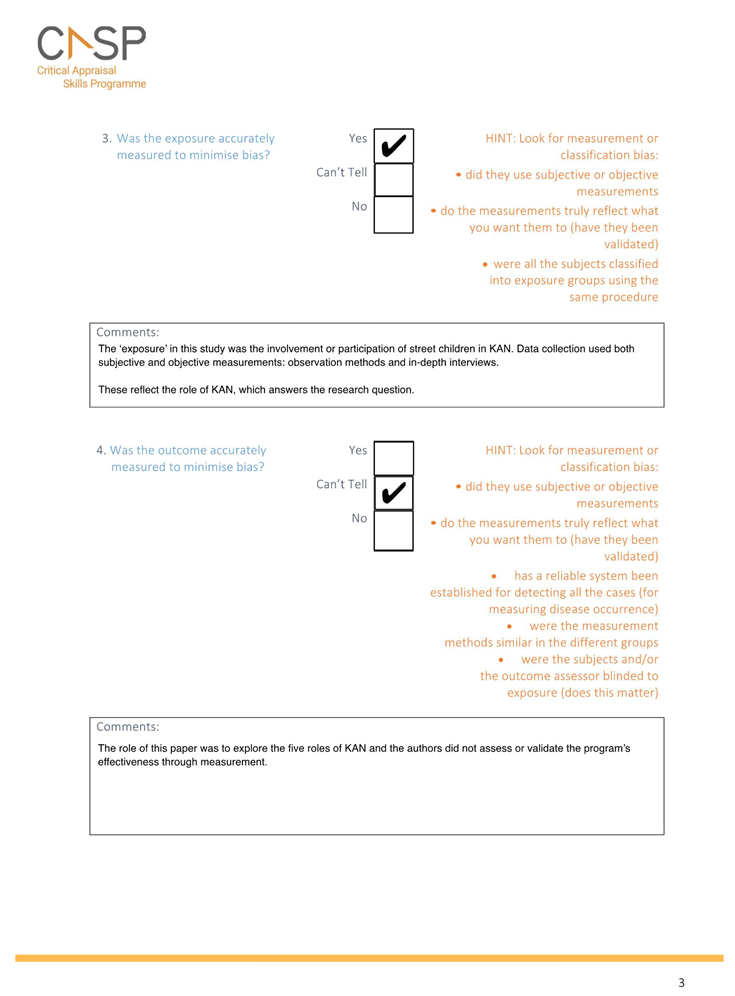

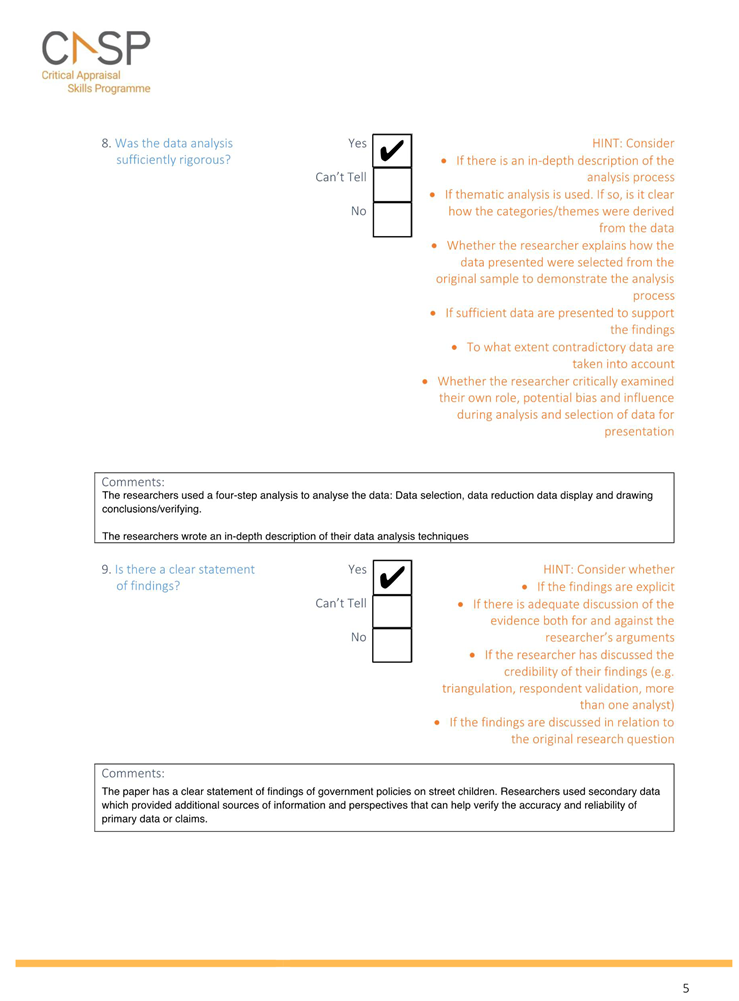

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | 6 |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 7 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 7–8 (Table 3) |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 8 (Table 4) |

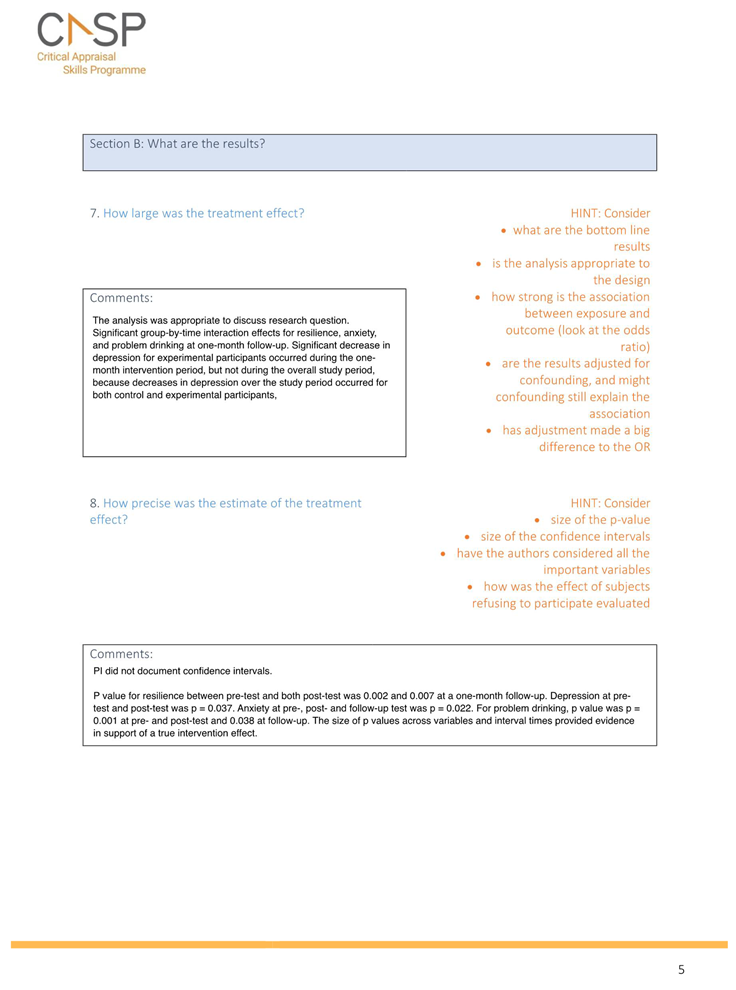

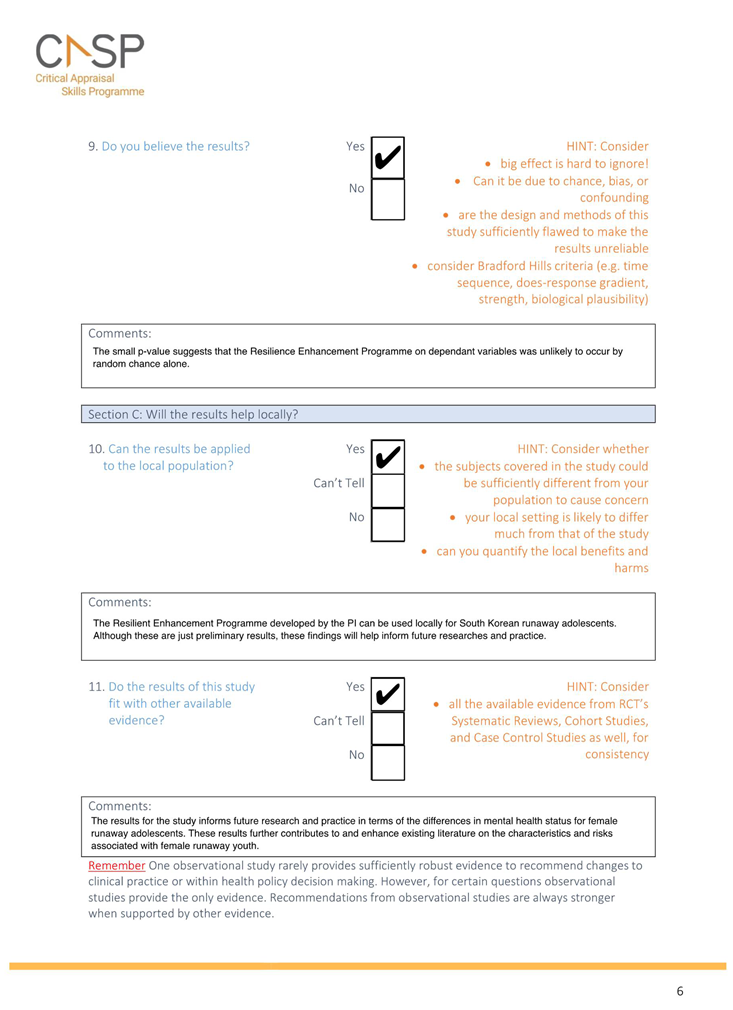

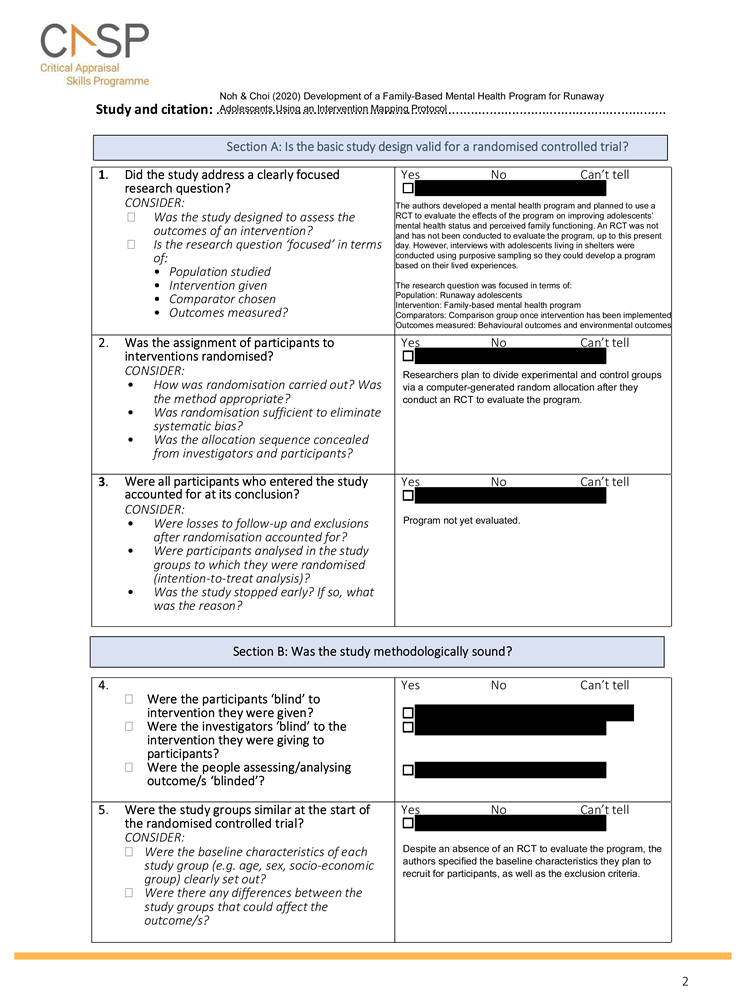

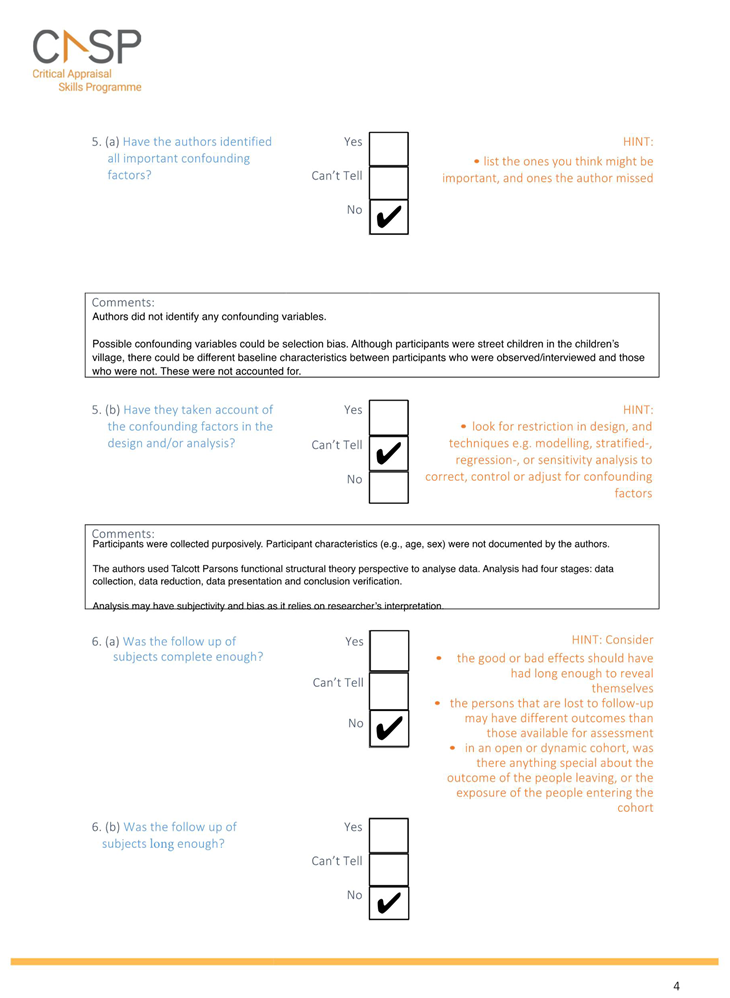

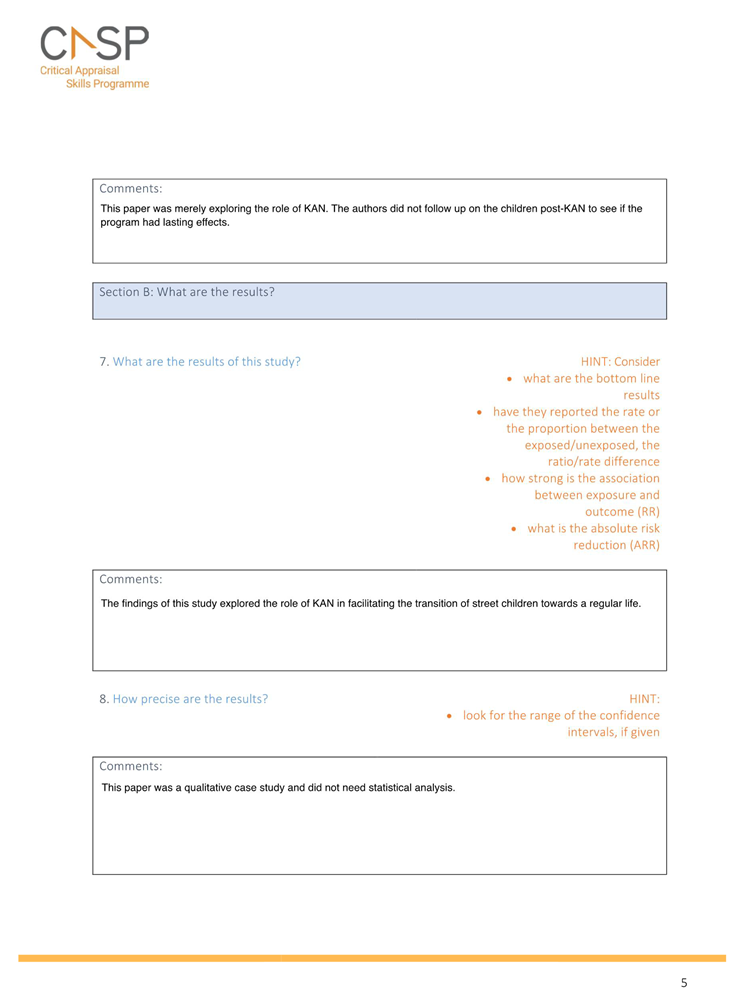

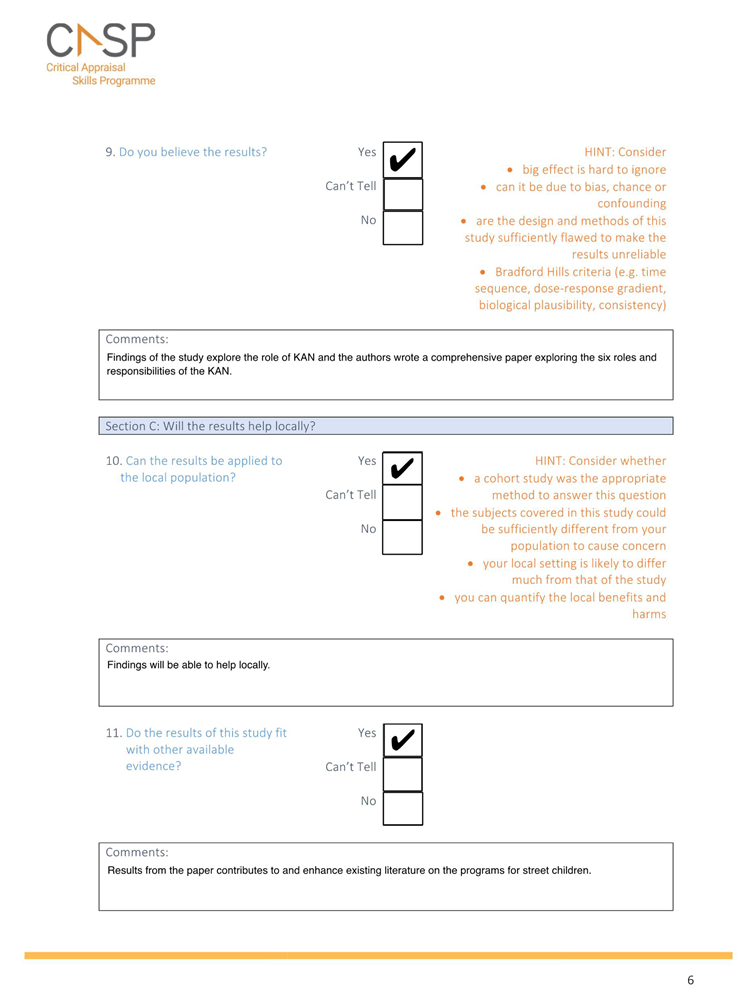

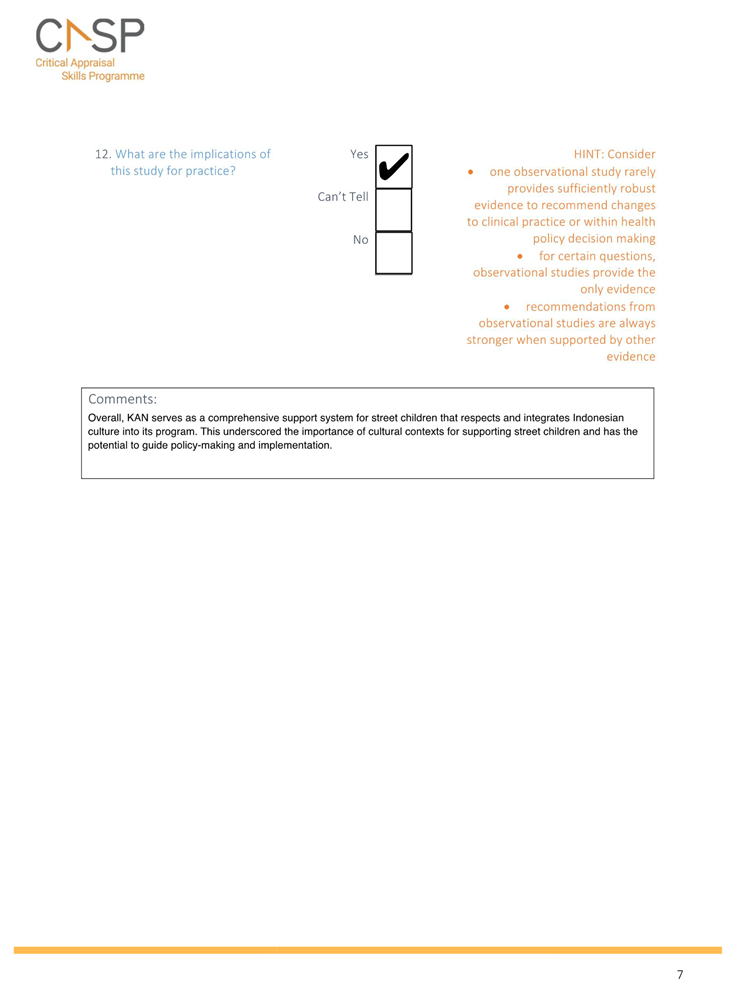

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | 6–11 (Appendix C) |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 8 (Table 4) |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 8–12 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 12–13 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 17 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 18–19 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 20 |

| JBI = Joanna Briggs Institute; PRISMA-ScR = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews. * Where sources of evidence (see second footnote) are compiled from, such as bibliographic databases, social media platforms, and Web sites. † A more inclusive/heterogeneous term used to account for the different types of evidence or data sources (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy documents) that may be eligible in a scoping review as opposed to only studies. This is not to be confused with information sources (see first footnote). ‡ The frameworks by Arksey and O’Malley (6) and Levac and colleagues (7) and the JBI guidance (4, 5) refer to the process of data extraction in a scoping review as data charting. § The process of systematically examining research evidence to assess its validity, results, and relevance before using it to inform a decision. This term is used for items 12 and 19 instead of "risk of bias" (which is more applicable to systematic reviews of interventions) to include and acknowledge the various sources of evidence that may be used in a scoping review (e.g., quantitative and/or qualitative research, expert opinion, and policy document). From: Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMAScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–473. | |||

Appendix B

| Category | Search terms |

| YEH | ((homeless* and (child* or youth* or adolescen* or teen* or young person* or young people*)) or street child* or street sleep* or "homeless* youth" or ill-housed person* or rough sleeper* or railway boy* or street dweller* or refugee*) (Homeless persons or Homelessness or Homeless family or Homeless Shelters or Homeless Youth or Homeless single person or "outreach to the homeless" or homeless mentally ill or homeless shelter resident or Homeless Health Concerns) (Runaways or Runaway children or Street Youth) |

|

AND |

|

| Mental health intervention | (mental health service* or therapeutic support* or counselling or counseling or housing program* or temporary shelter* or homeless shelter* or psychological counseling or psychological counselling or short-term temporary care or short-term care or youth homeless* shelter or non government* organisation* or non government* organization* or non-government* organisation* or non-government* organization* or NGO* or mental health care or mental health support* or cognitive behavioural therap* or cognitive behavioral therap* or CBT* or substance abuse therap* or outreach program* or outreach support* or mental health intervention* or mental health* or life counseling or life counselling or overcrowded or refugee* or emergency accommodation* or homeless* facilit* or rehabilitation* or prevention approach* or social work* or therap*) Mental Health Services/ or Child Guidance/ or Community Mental Health Services/ or Counseling/ or Emergency Services, Psychiatric/ or Social Work, Psychiatric/ (health service, mental or health services, mental or hygiene service, mental or hygiene services, mental or mental health service or mental health services or mental hygiene service or mental hygiene services or service, mental health or service, mental hygiene or services, mental health or services, mental hygiene) |

|

AND |

|

| EAP countries | (east asia* pacific or east asia* pacific countr* or cambodia* or china or chinese* or hong kong or indonesia* or japan* or south korea* or lao* pdr or macau or macanese or malaysia* or mongolia* or myanmar or pacific island* or papua new guinea or papuans or philippin* or filipin* or the philippine* or singapore* or taiwan* or thai or timor-leste or vietnam*) exp Cambodia/ or exp Indochina/ or exp Indonesia/ or exp Laos/ or exp Malaysia/ or exp Myanmar/ or exp Philippines/ or exp Singapore/ or exp Thailand/ or exp Timor-Leste/ or exp Vietnam/ or exp China/ or exp Japan/ or exp Korea/ or exp Mongolia/ or exp Taiwan/ or exp Indonesia/ or exp Japan/ or exp Macau/ or exp Philippines/ or exp Taiwan/ |

| Results: 120 |

| Category | Search terms |

| YEH | ((homeless* and (child* or youth* or adolescen* or teen*)) or street child* or street sleep* or ill-housed person* or rough sleep* or street dwell* or railway boy*) (child, homeless or child, street or children, homeless or children, street or homeless child or homeless children or homeless youth or homeless youths or runaway or runaways or street child or street children or street youth or youth, homeless or youth, street or youths, homeless or youths, street) |

|

AND |

|

| Mental health intervention | (mental health service* or therapeutic support* or counselling or counseling or housing program* or temporary shelter* or homeless shelter* or psychological counseling or psychological counselling or short-term temporary care or short-term care or youth homeless* shelter or non government* organisation* or non government* organization* or non-government* organisation* or non-government* organization* or NGO* or mental health care or mental health support* or cognitive behavioural therap* or cognitive behavioral therap* or CBT* or substance abuse therap* or outreach program* or outreach support* or mental health intervention* or mental health* or life counseling or life counselling or overcrowded or centre base* or center base* or emergency accommodation* or homeless* facilit* or food bank* or rehabilitation* or prevention approach* or social work* or therap*) (Rehabilitation Counseling or School Counseling or Aftercare or School Counseling or Mental Health Services or Community Mental Health Services or Early Intervention or Family Intervention or School Based Intervention or Mental Health Programs or Crisis Intervention Services or Hot Line Services or Suicide Prevention Centers or Home Visiting Programs or Suicide Prevention Centers) |

|

AND |

|

| EAP countries | (east asia* pacific or east asia* pacific countr* or cambodia* or china or chinese* or hong kong or indonesia* or japan* or south korea* or lao* pdr or macau or macanese or malaysia* or mongolia* or myanmar or pacific island* or papua new guinea or papuans or philippin* or filipin* or the philippine* or singapore* or taiwan* or thai or timor-leste or vietnam*) (Pacific Islanders or Asia Southeastern or Asia Eastern) |

| Results: 153 |

| Category | Search terms |

| YEH | (((((((((((((homeless*)) AND (child*)) OR (youth*)) OR (adolescen*)) OR (teen*)) OR (ill-housed person*)) OR ("homeless teen")) OR ("street sleeper"[tiab:~0])) OR ("children of the street"[tiab:~0])) OR ("street youth")) OR ("runaway* child*")) OR ("runaway* adolescen*")) OR ("street child*") |

| AND | |

| Mental health intervention | ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((mental health service*) OR (therapeutic support*)) OR (counselling)) OR (counseling)) OR ("housing program*")) OR ("temporary shelter*")) OR ("homeless shelter*")) OR ("psychological counseling")) OR ("psychological counselling")) OR ("temporary care")) OR ("short-term care")) OR ("youth homeless* shelter"[tiab:~10])) OR ("non government* organisation")) OR ("non government* organization")) OR ("non-government* organisation")) OR ("non-government* organization")) OR ("NGO"[tiab])) OR ("mental health care")) OR ("mental health support*")) OR ("cognitive behavioural therap*")) OR ("cognitive behavioral therap*")) OR (CBT[tiab])) OR ("substance abuse therap*")) OR ("outreach program*")) OR ("outreach support*")) OR ("mental health intervention")) OR ("rehabilitation counseling")) OR ("community mental health service*")) OR ("family intervention*")) OR ("mental health program*")) OR ("crisis intervention service*")) OR ("hot line service*")) OR ("suicide prevention center*") ) OR (psychotherap*)) OR ("homeless intervention*") |

| AND | |

| EAP countries | ((((((((((((((((((((((((((((east asia* pacific) OR (east asia* pacific countr*)) OR (cambodia*)) OR (china)) OR (chinese)) OR (hong kong)) OR (indonesia*)) OR (japan*)) OR (south korea*)) OR (lao* pdr)) OR (macau)) OR (macanese)) OR (malaysia*)) OR (mongolia*)) OR (myanmar)) OR (pacific island*)) OR (papua new guinea)) OR (papuans)) OR (philippin*)) OR ("the philippin*")) OR (filipin*)) OR (singapore*)) OR (taiwan*)) OR (thai)) OR (timor-leste)) OR (vietnam*)) OR ("south-east asia*")) OR ("southeast asia*")) OR ("east asia*") |

| Results: 2,546 |

| Category | Search terms |

| YEH | "homeless*" OR "homeless* youth" OR "homeless* child*" OR "homeless* adolescen*" OR "homeless* teen" OR " homeless* young person*" OR "homeless* young people*" OR "street child*" OR "street sleeper" OR "homeless* youth" OR "ill-housed person" OR "street youth" OR runaway* OR "runaway youth*" OR "street youth*" OR "rough sleep*" OR "railway boy*" OR "street dwell*" OR "refugee*” |

| AND |

|

| Mental health intervention | "mental health service*" OR "mental health intervention*" OR "psychological intervention*" OR "therap* support*" OR counseling OR “counselling” OR "psychological counseling" OR “psychological counselling” OR "short-term temporary care" OR "short-term care" OR "youth homeless* shelter" OR "homeless* shelter*" OR "non-government* organisation*" OR “non-governmen* organization” OR NGO* OR "mental health care" OR "mental health support" OR "cognitive behavioural therap*" OR “cognitive behavioral therap*” OR CBT OR "outreach program*" OR "outreach support*" OR "outreach work*" OR "homeless* policy*" OR "homeless* policies" OR "homeless* law*" OR "policies" or "policy" OR "community service*" OR "community mental health service*" OR "emergency service*" OR "family therap*" OR "family intervention*" OR "mental health program*" OR "crisis intervention* service*" OR "hotline service*" OR "school based intervention*" OR "suicide prevention cent*" OR "home visiting program*" OR "community program*" OR "family based intervention*" OR "family based intervention*" OR "emergency accommodation*" OR "homeless* facilit*" OR "food bank*" OR rehabilitation* OR "social work*" |

| AND |

|

| EAP countries | "east asia* pacific" OR "east asia* pacific countr*" OR cambodia* OR china OR chinese OR "hong kong" OR indonesia* OR japan* or "south korea*" OR "lao* pdr" OR macau OR macanese OR malaysia* OR mongolia* OR myanmar OR "pacific island*" OR "papua new guinea" OR papuans OR philippin* OR "the philippin*" OR filipin* OR singapore* OR taiwan* OR thai* OR "timor-leste" OR viet* |

| Results: 613 |

| Category | Search terms |

| YEH | ((((((((((((((((ALL=(homeless*)) AND ALL=(youth*)) OR ALL=(child*)) OR ALL=(adolescen*)) OR ALL=(teen)) OR ALL=("street child*")) OR ALL=("street sleeper")) OR ALL=("ill-housed person*")) OR ALL=("street youth*")) OR ALL=(runaway*)) OR ALL=("runaway youth*")) OR ALL=("homeless youth*")) OR ALL=("rough sleep*")) OR ALL=("railway boy*")) OR ALL=("street dwell*")) OR ALL=("refugee*")) OR ALL=("left behind child*") |

|

AND |

|

| Mental health intervention | (((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((((ALL=("mental health service*")) OR ALL=("mental health intervention*")) OR ALL=("psychological intervention*")) OR ALL=("therap* support*")) OR ALL=(counseling)) OR ALL=(counselling)) OR ALL=("psychological counseling")) OR ALL=("psychological counselling")) OR ALL=("short-term temporary care")) OR ALL=("short-term care")) OR ALL=("youth homeless* shelter*")) OR ALL=("homeless* shelter")) OR ALL=("non-government* organisation*")) OR ALL=("non-government* organization*")) OR ALL=(NGO*)) OR ALL=("mental health care")) OR ALL=("mental health support*")) OR ALL=("cognitive behavioural therap*")) OR ALL=("cognitive behavioral therap*")) OR ALL=(CBT)) OR ALL=("motivation* interview*")) OR ALL=("substance abuse therap*")) OR ALL=("outreach program*")) OR ALL=("outreach support*")) OR ALL=("outreach work*")) OR ALL=(policy)) OR ALL=("mental health*")) OR ALL=("life counseling")) OR ALL=("life counselling")) OR ALL=("overcrowded")) OR ALL=("centre based")) OR ALL=("center based")) OR ALL=("emergency accommodation")) OR ALL=("homeless* facilit*")) OR ALL=("food bank*")) OR ALL=("rehabilitation*")) OR ALL=("social work*")) OR ALL=("therap*") |

|

AND |

|

| EAP countries | (((((((((((((((((((((((((ALL=("east asia* pacific")) OR ALL=("east asia* pacific countr*")) OR ALL=(cambodia*)) OR ALL=(china)) OR ALL=(chinese)) OR ALL=("hong kong")) OR ALL=(indonesia*)) OR ALL=(japan*)) OR ALL=("south korea*")) OR ALL=("lao* pdr")) OR ALL=(macau)) OR ALL=(manganese)) OR ALL=(malaysia*)) OR ALL=(mongolia*)) OR ALL=(myanmar)) OR ALL=("pacific island*")) OR ALL=("papua new guinea")) OR ALL=(papuans)) OR ALL=(philippin*)) OR ALL=("the philippin*")) OR ALL=("filipin*")) OR ALL=(singapore*)) OR ALL=(tawain*)) OR ALL=(thai*)) OR ALL=("timor-leste")) OR ALL=(vietnam*) |

| Results: 92 |

Appendix C

References

- OECD. HC3.1. Homeless populations. https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC3-1-Homeless-population.pdf.

- United Nations. Affordable housing and social protection systems for all to address homelessness: report of the Secretary-General. 2020;

- Speak S. The state of homelessness in developing countries ‘Affordable housing and social protection systems for all to address homelessness’ United Nations Office at Nairobi. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2019/05/SPEAK_Suzanne_Paper.pdf.

- Alif Jasni M, Hassan N, Ibrahim F, Kamaluddin MR, Che Mohd Nasir N. The interdepence between poverty and homelessness in Southeast Asia: The case of Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Singapore. International Journal of Law, Government and Communication. 09/09 2022;7:205-222. https://doi.org/10.35631/IJLGC.729015. [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. At the Margins: Street children in Asia and the Pacific. Asian Development Bank, Regional and Sustainable Development Department; 2003.

- Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre [IDMC]. Disaster displacement in Asia and the Pacific. [online] https://www.internal-displacement.org/sites/default/files/publications/documents/220919_IDMC_Disaster-Displacement-in-Asia-and-the-Pacific.pdf.

- Su Z, Bentley BL, Cheshmehzangi A, et al. Mental health of homeless people in China amid and beyond COVID-19. The Lancet Regional Health – Western Pacific. 2022;25doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100544. [CrossRef]

- Klatt T, Cavner D, Egan V. Rationalising predictors of child sexual exploitation and sex-trading. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014/02/01/ 2014;38(2):252-260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.08.019. [CrossRef]

- Aptekar L, Stoecklin D. Street children and homeless youth: A cross-cultural perspective. vol 9789400773561. 2013:1-240.

- Bhukuth A, Jerome B. Children of the street: Why are they in the street? How do they live? Economics & Sociology. 12/20 2015;8:134-148. https://doi.org/10.14254/2071-789X.2015/8-4/10. [CrossRef]

- Bender KA, Thompson SJ, Ferguson KM, Yoder JR, Kern L. Trauma among street-involved youth. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. 2014;22(1):53-64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1063426613476093. [CrossRef]

- Saddichha S, Linden I, Krausz MR. Physical and mental health issues among homeless youth in British Columbia, Canada: Are they different from older homeless adults? . Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;23(3):200-206.

- Yoder KA, Longley SL, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR. A dimensional model of psychopathology among homeless adolescents: Suicidality, internalising, and externalising disorders. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008/01/01 2008;36(1):95-104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9163-y. [CrossRef]

- Bender K, Begun S, Durbahn R, Ferguson K, N S. My own best friend: Homeless youths’ sesitance to seek help and strategies for coping independently after distressing and traumatic experiences. Social Work in Public Health. 2018;33(3):149--162. https://doi.org/10.1080/19371918.2018.1424062 , note = PMID: 29377774. [CrossRef]

- Falci CD, Whitbeck LB, D.R H, Rose T. Predictors of change in self-reported social networks among homeless young people. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2011;21(4):827-841.

- Kolar K, Erickson PG, Stewart D. Coping strategies of street-involved youth: exploring contexts of resilience. Journal of Youth Studies. 2012/09/01 2012;15(6):744-760. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2012.677814. [CrossRef]

- Lee S-J, Liang L-J, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Milburn NG. Resiliency and survival skills among newly homeless adolescents: Implications for future interventions. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies. 2011/12/01 2011;6(4):301-308. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2011.626468. [CrossRef]

- Lee Y, Hyoung LM. Effects of drinking, self-esteem and social networks on resilience of the homeless. Alcohol and Health Behaviour Research. 2014;15(1):51–63.

- Moskowitz A, Stein JA, Lightfoot M. The mediating roles of stress and maladaptive behaviours on self-harm and suicide attempts among runaway and homeless youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2013/07/01 2013;42(7):1015-1027. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9793-4. [CrossRef]

- Hubley AM, Russell LB, Palepu A, Hwang SW. Subjective quality of life among individuals who are homeless: A review of current knowledge. Social Indicators Research. 2014/01/01 2014;115(1):509-524. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-9998-7. [CrossRef]

- Perlman S, Willard J, Herbers JE, Cutuli JJ, Garg KME. Youth homelessness: Prevalence and mental health correlates. Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research. 2014;5(3):361-377. https://doi.org/10.1086/677757. [CrossRef]

- Slesnick N, Zhang J, Walsh L. Youth experiencing homelessness with suicidal ideation: Understanding risk associated with peer and family social networks. Community Mental Health Journal. 2021/01/01 2021;57(1):128-135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00622-7. [CrossRef]

- Tyler KA, Whitbeck LB, Hoyt DR, Cauce AM. Risk factors for sexual victimisation among male and female homeless and runaway youth. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2004;19(5):503-520. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260504262961. [CrossRef]

- Mostajabian S, Santa Maria D, Wiemann C, Newlin E, Bocchini C. Identifying sexual and labour exploitation among sheltered youth experiencing homelessness: A comparison of screening methods. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(3):363.

- Gao Y, Atkinson-Sheppard S, Yu Y, Xiong G. A review of the national policies on street children in China. Children and Youth Services Review. 2018/10/01/ 2018;93:79-87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.07.009. [CrossRef]

- Nurwati N, Fedryansyah M, Achmad W. Social policy in the protection of street children in Indonesia. Journal of Governance. 2022;7(3)doi:10.31506/jog.v7i3.16366. [CrossRef]

- Hyun M-S, Chung H-IC, Lee Y-J. The effect of cognitive–behavioural group therapy on the self-esteem, depression, and self-efficacy of runaway adolescents in a shelter in South Korea. Applied Nursing Research. 2005/08/01/ 2005;18(3):160-166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2004.07.006. [CrossRef]

- Noh D, Kim E. Experiences of family conflict in shelter-residing runaway youth: A phenomenological study. Journal of Family Issues. 2021;42(10):2335-2352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x20979624. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations demographic yearbook review national reporting of household characteristics, living arrangements and homeless households Implications for international recommendations. https://unstats.un.org/unsd/demographic-social/products/dyb/documents/techreport/hhchar.pdf.

- UN-Habitat. Homelessness and the right to adequate housing. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Housing/Homelessness/UNagencies_regionalbodies/13112015-UN_Habitat.docx.

- Iwata M. What is the problem of homelessness in Japan? Conceptualisation, research, and policy response. International Journal on Homelessness. 2021;1(1):98–124. https://doi.org/10.5206/ijoh.2021.1.13629. [CrossRef]

- Tan H. ‘We are not like them’: stigma and the Destitute Persons Act of Singapore. International Journal of Law in Context. 2021;17(3):318-335. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744552321000410. [CrossRef]

- Korea Legislation Research Institute. Acts on support for welfare and self-reliance of the homeless. elaw.klri.re.kr. https://elaw.klri.re.kr/eng_service/lawView.do?hseq=45559&lang=ENG.

- Rosenthal D, Lewis C, Heys M, et al. Barriers to optimal health for Under 5s experiencing homelessness and living in temporary accommodation in high-income countries: A scoping review. Ann Public Health Res. 2021;8(1).

- Kanehara A, Umeda M, Kawakami N, World Mental Health Japan Survey Group. Barriers to mental health care in Japan: Results from the world mental health Japan survey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015/09// 2015;69(9):523-533. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.12267. [CrossRef]

- Lasco G, Gregory Yu V, David CC. The lived realities of health financing: A qualitative exploration of catastrophic health expenditure in the Philippines. Acta Medica Philippina. 2022;56(11)doi:10.47895/amp.vi0.2389. [CrossRef]

- Martinez AB, Co M, Lau J, Brown JSL. Filipino help-seeking for mental health problems and associated barriers and facilitators: A systematic review. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2020/11/01 2020;55(11):1397-1413. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01937-2. [CrossRef]

- Cipta D, Saputra A. Changing landscape of mental health from early career psychiatrists’ perspective in Indonesia. Journal of Global Health Neurology and Psychiatry. 08/05 2022;doi:10.52872/001c.37413. [CrossRef]

- Lally J, Tully J, Samaniego R. Mental health services in the Philippines. BJPsych International. 2019;16(3):62-64. https://doi.org/10.1192/bji.2018.34. [CrossRef]

- Meshvara D. Mental health and mental health care in Asia. World Psychiatry. Jun 2002;1(2):118-20.

- Cheng L-C, Yang Y-S. Homeless problems in Taiwan: Looking beyond legality toward social issues. City, Culture and Society. 2010/09/01/ 2010;1(3):165-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2010.10.005. [CrossRef]

- Kubota H, Clandinin DJ, Caine V. ‘I hope one more flower will bloom in my life’: Retelling the stories of being homeless in Japan through narrative inquiry. Journal of Social Distress and Homelessness. 2019/01/02 2019;28(1):14-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/10530789.2018.1541638. [CrossRef]

- Biswas J, Gangadhar BN, Keshavan M. Cross cultural variations in psychiatrists’ perception of mental illness: A tool for teaching culture in psychiatry. Asian Journal of Psychiatry. 2016/10/01/ 2016;23:1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2016.05.011.

- Kirmayer LJ. The cultural diversity of healing: Meaning, metaphor and mechanism. British Medical Bulletin. 2004;69(1):33-48. https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldh006.

- Liu J, Yan F, Ma X, et al. Perceptions of public attitudes towards persons with mental illness in Beijing, China: Results from a representative survey. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2016/03/01 2016;51(3):443-453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-015-1125-z. [CrossRef]

- Yang F, Yang BX, Stone TE, et al. Stigma towards depression in a community-based sample in China. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2020/02/01/ 2020;97:152152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2019.152152. [CrossRef]

- Gopalkrishnan N. Cultural diversity and mental health: Considerations for policy and practice. Review. Frontiers in Public Health. 2018-June-19 2018;6doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00179. [CrossRef]

- Helfrich CA, Fogg LF. Outcomes of a life skills intervention for homeless adults with mental illness. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2007/07/01 2007;28(3):313-326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10935-007-0103-y. [CrossRef]

- Slesnick N, Guo X, Brakenhoff B, Bantchevska D. A comparison of three interventions for homeless youth evidencing substance use disorders: Results of a randomised clinical trial. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2015;54:1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2015.02.001. [CrossRef]

- Spiegel JA, Graziano PA, Arcia E, et al. Addressing mental health and trauma-related needs of sheltered children and families with Trauma-Focused Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (TF-CBT). Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2022/09/01 2022;49(5):881-898. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01207-0. [CrossRef]

- Altena AM, Brilleslijper-Kater SN, Wolf JRLM. Effective interventions for homeless youth: A systematic review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2010;38(6):637-645. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2010.02.017. [CrossRef]

- Morton MH, Kugley S, Epstein R, Farrell A. Interventions for youth homelessness: A systematic review of effectiveness studies. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020/09/01/ 2020;116:105096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105096. [CrossRef]

- Wang JZ, Mott S, Magwood O, et al. The impact of interventions for youth experiencing homelessness on housing, mental health, substance use, and family cohesion: A systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2019/11/14 2019;19(1):1528. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7856-0. [CrossRef]

- Centre for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa). CEBMa Guideline for Critically Appraised Topics in Management and Organisations. [online]. Centre for Evidence-Based Management. https://www.cebma.org/wp-content/uploads/CEBMa-CAT-Guidelines.pdf.

- Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2018;169(7):467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/m18-0850 %m 30178033.

- Rojon C, Okupe A, McDowall A. Utilisation and development of systematic reviews in management research: What do we know and where do we go from here? International Journal of Management Reviews. 2021;23(2):191-223. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12245. [CrossRef]

- Richardson WS, Wilson MC, Nishikawa J, Hayward RS. The well-built clinical question: A key to evidence-based decisions. ACP J Club. Nov-Dec 1995;123(3):A12-3.

- The World Bank. The World Bank In East Asia Pacific. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap/overview Accessed in May 2023 and April 2024.

- The World Bank. The World Bank in East Asia Pacific. https://www.worldbank.org/en/region/eap Accessed in May 2023 and April 2024.

- Centre for Homelessness Impact (CHI). Centre for homelessness impact. https://www.homelessnessimpact.org/.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71. [CrossRef]

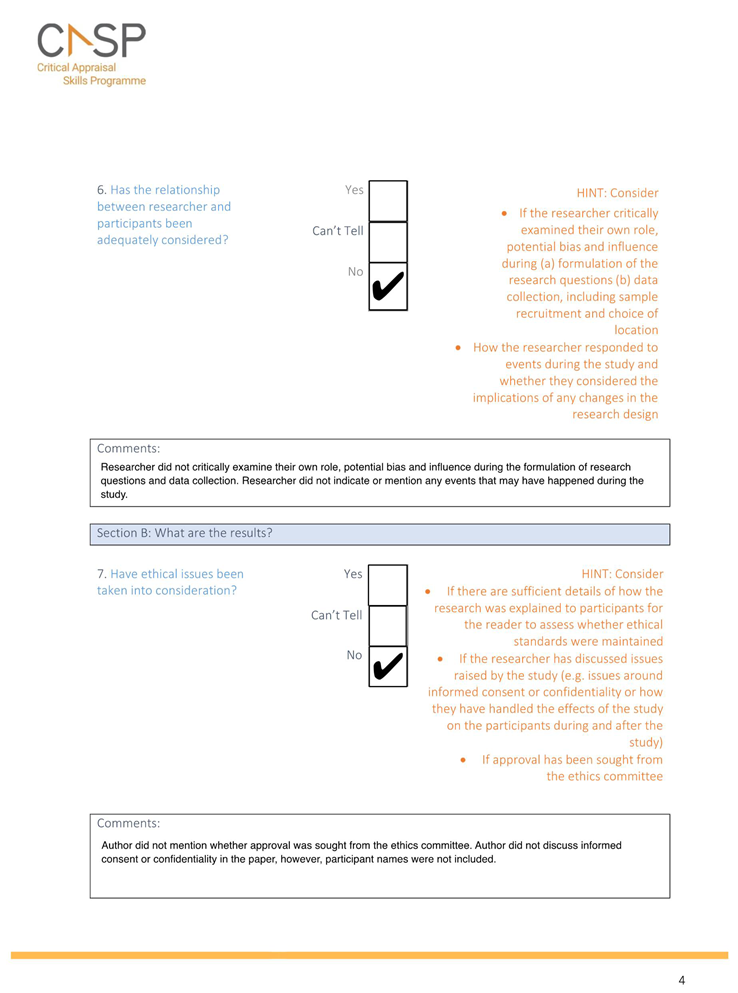

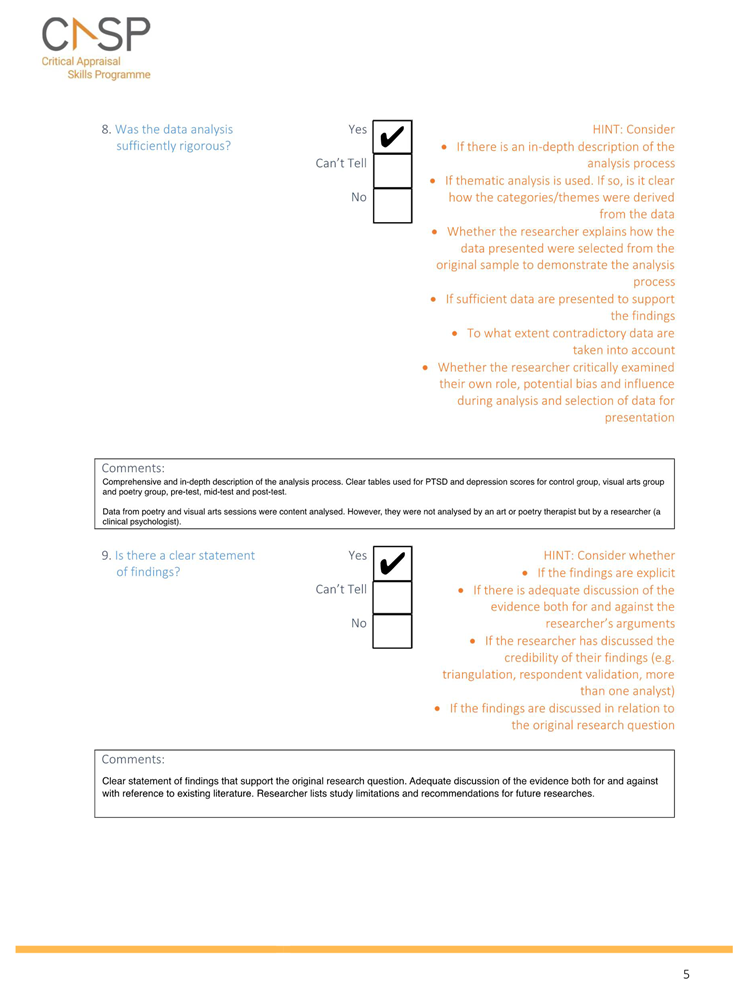

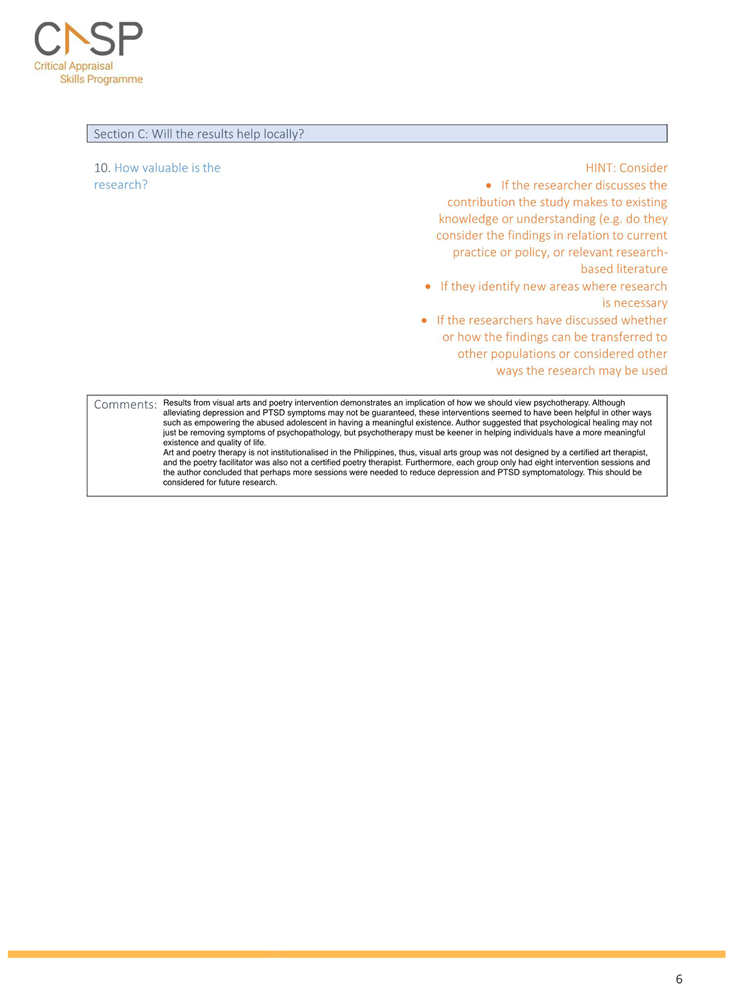

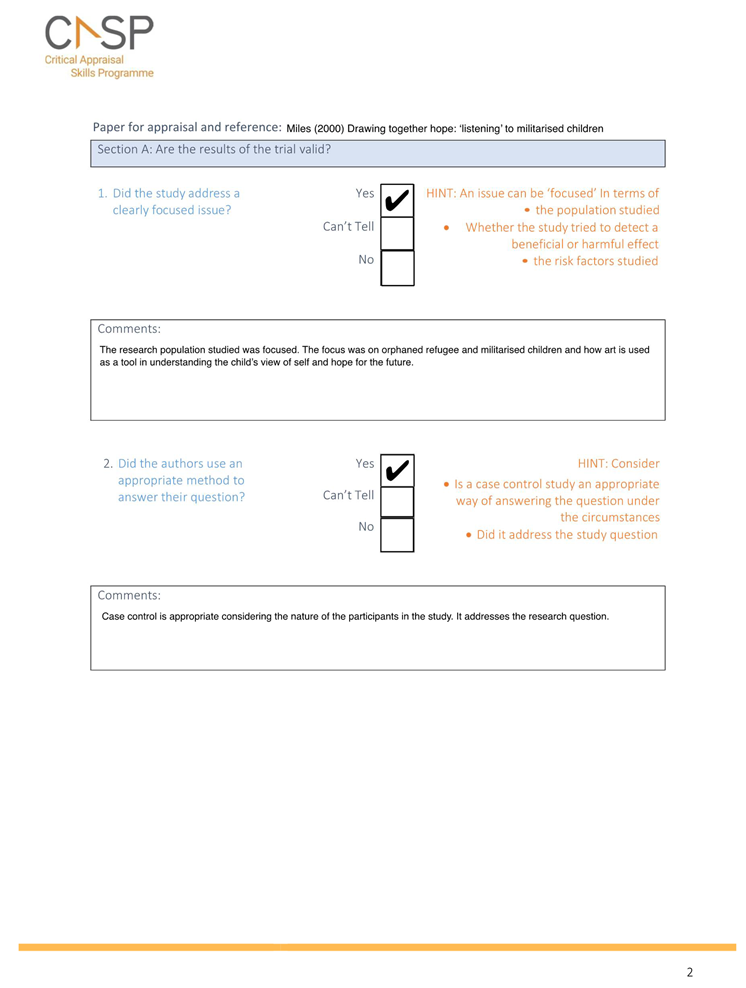

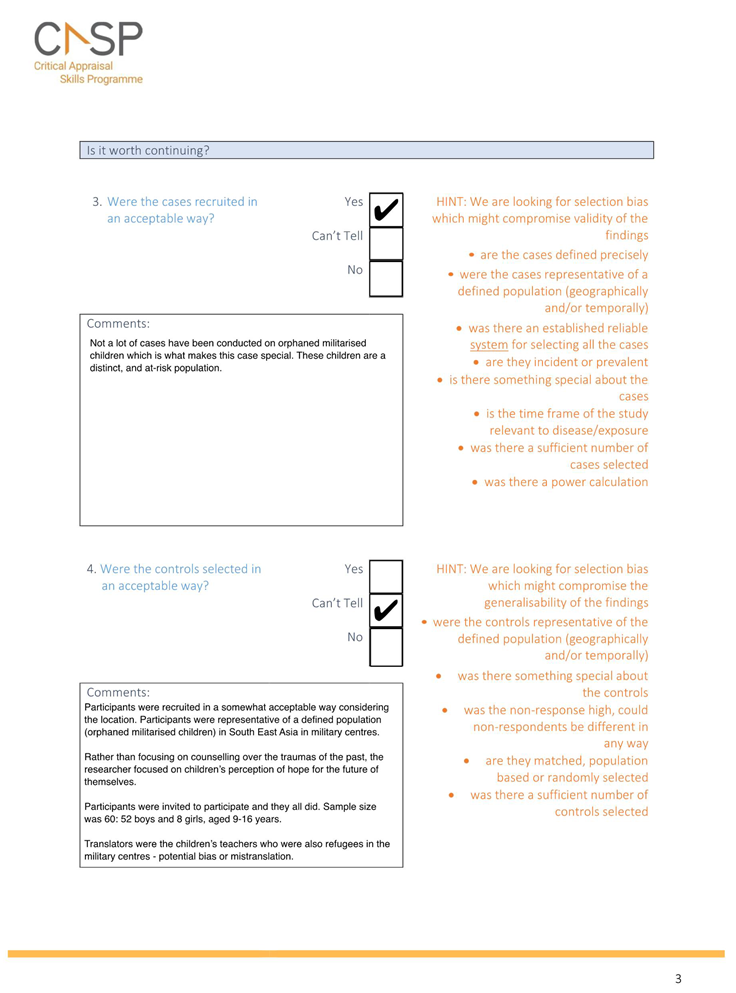

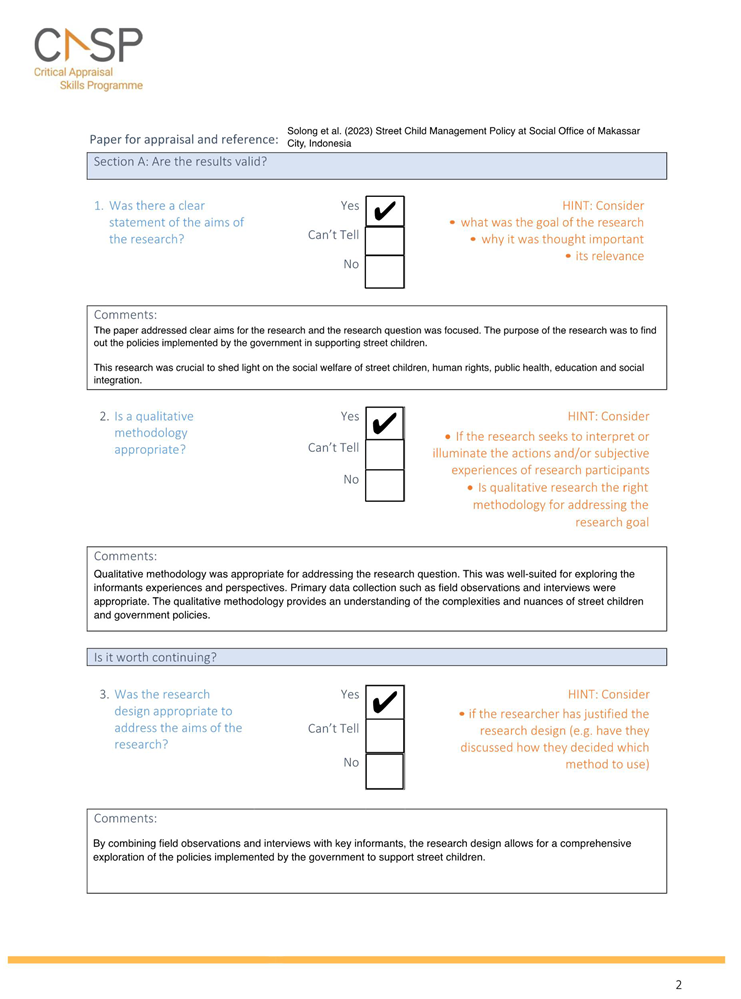

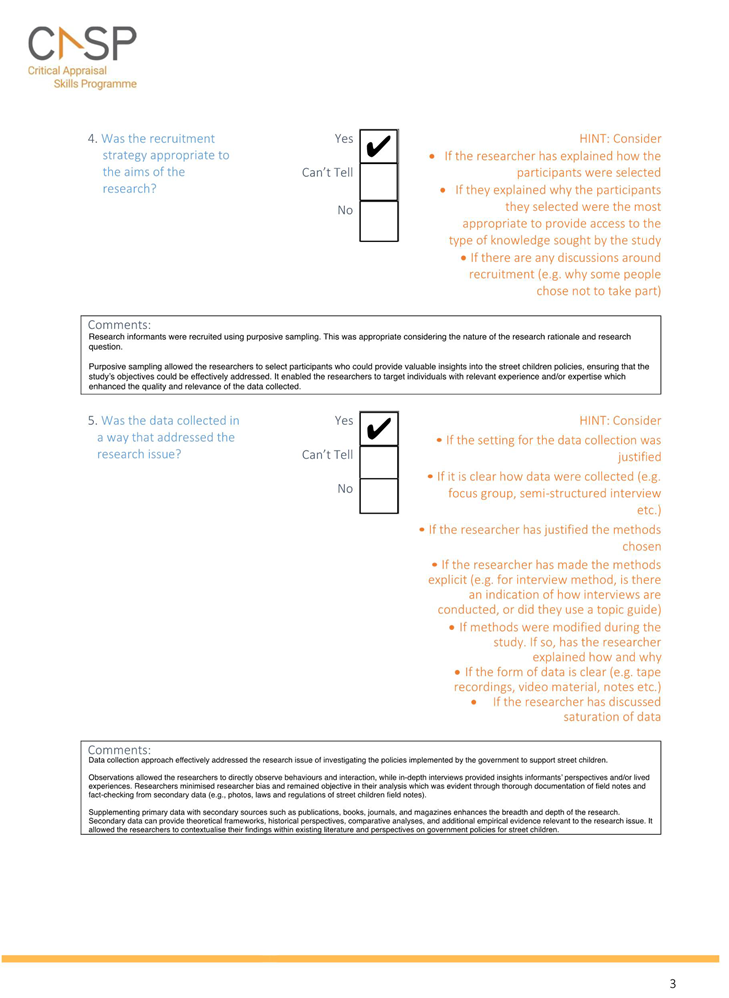

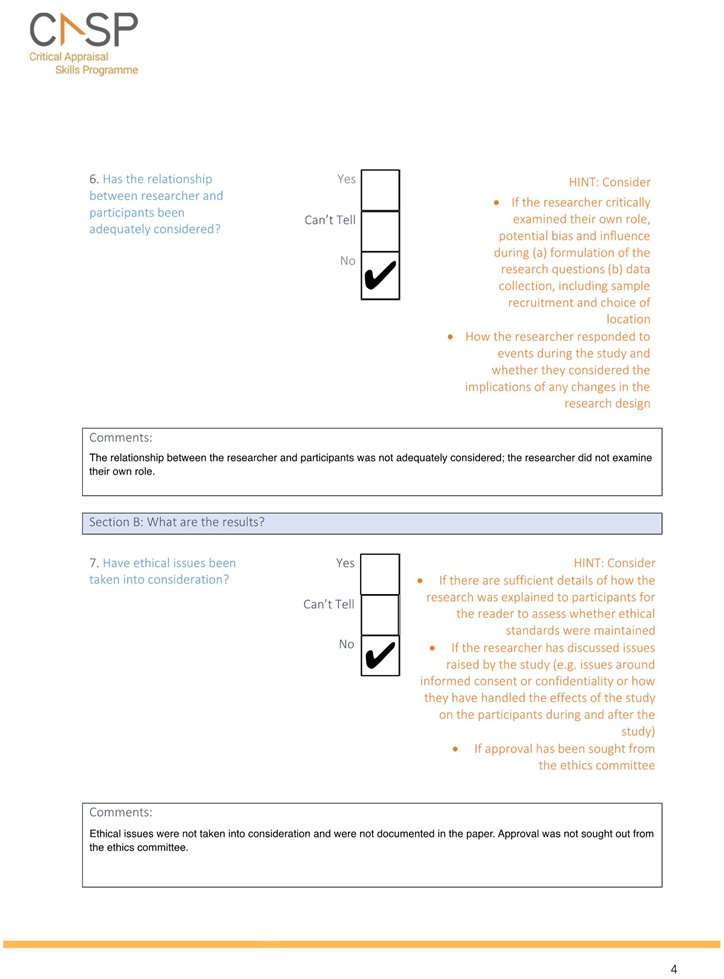

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Randomised Controlled Trial Checklist [online]. https://casp-uk.net/checklists/casp-rct-randomised-controlled-trial-checklist.pdf.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Qualitative Studies Checklist [online]. https://casp-uk.net/checklists/casp-qualitative-studies-checklist-fillable.pdf.

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Case Control Study Checklist [online]. 2018;

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP). CASP Cohort Study Checklist [online]. 2018;

- Long HA, French DP, Brooks JM. Optimising the value of the critical appraisal skills programme (CASP) tool for quality appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis. Research Methods in Medicine & Health Sciences. 2020;1(1):31-42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2632084320947559. [CrossRef]

- Sarmini M, Sukartiningsih S. From the road to the arena: The role of Kampung Anak Negeri for street children. Atlantis Press; 2018:1572-1577.

- Solong A, Rahman M, Aras D, Alim A. Street child management policy at social office of Makassar City, Indonesia. International Journal of Research 2023;11(4):33-50. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v11.i4.2023.5128. [CrossRef]

- Mohammadzadeh M, Awang H, Hayati K.S, Ismail S. The effects of a life skills-based intervention on emotional health, self-esteem and coping mechanisms in Malaysian institutionalised adolescents: Protocol of a multi-centre randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Educational Research. 2017/01/01/ 2017;83:32-42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2017.02.010. [CrossRef]

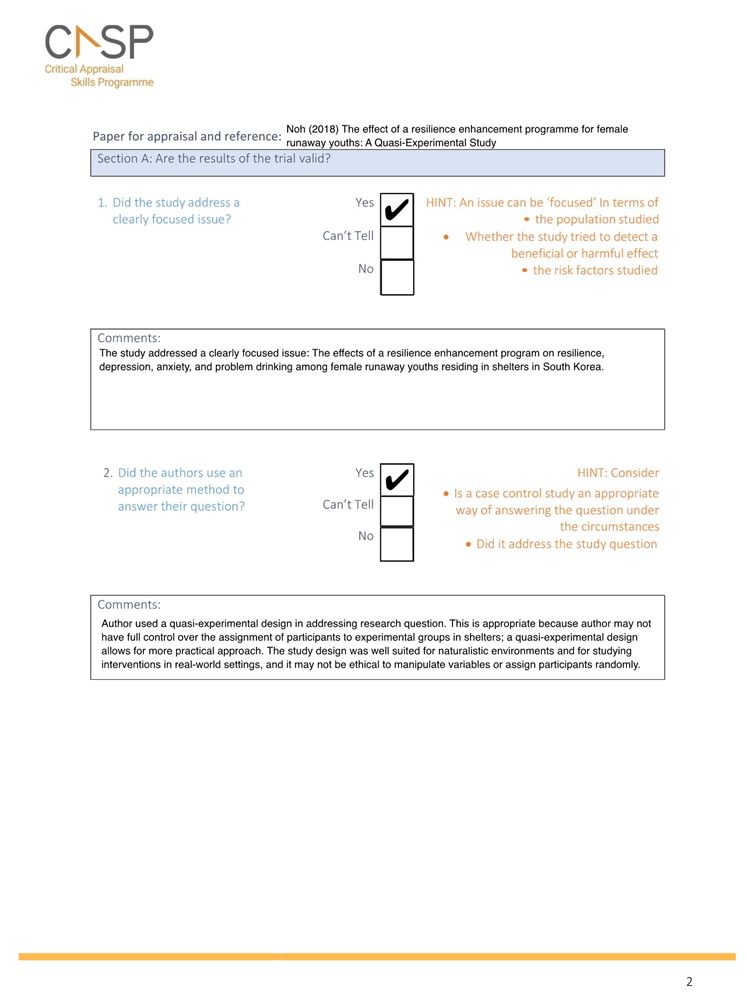

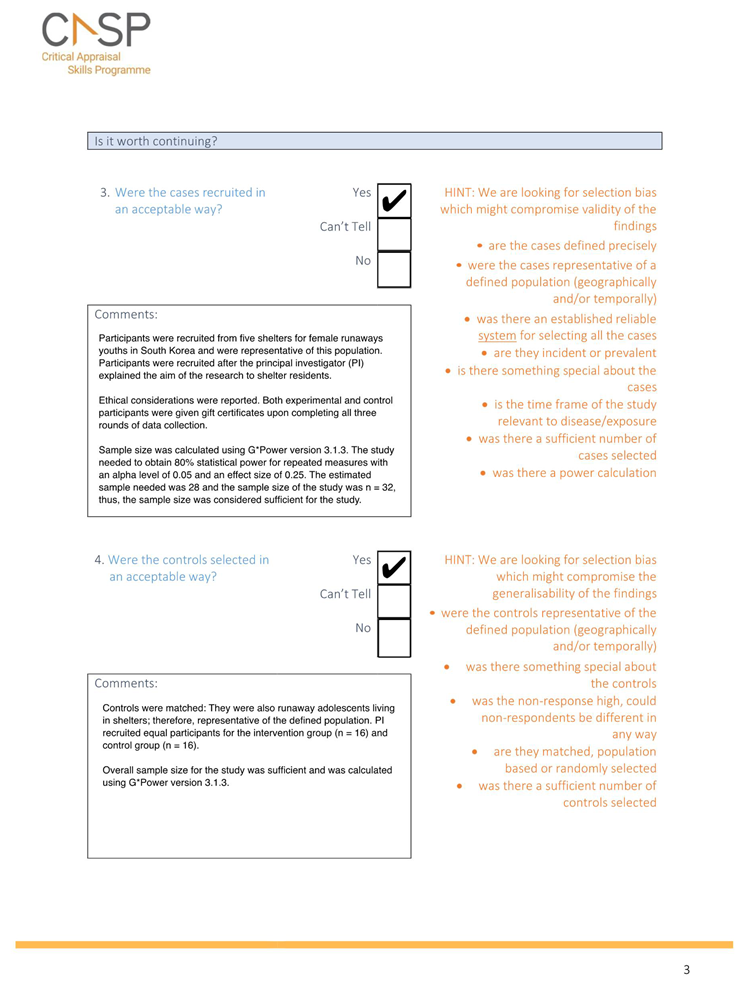

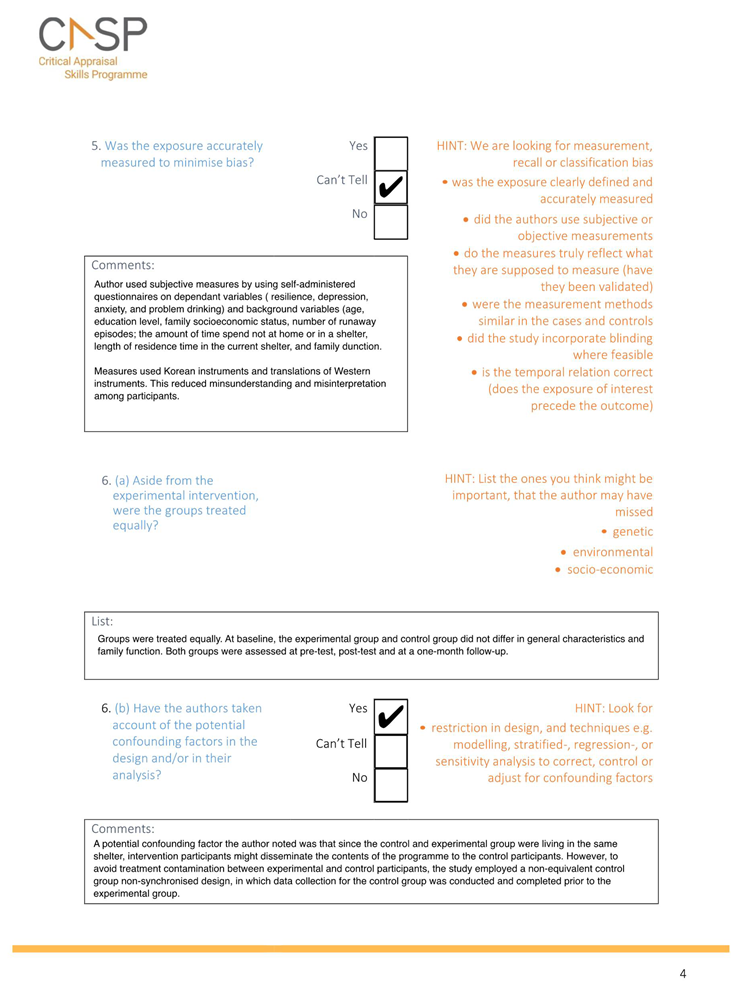

- Noh D. The effect of a resilience enhancement programme for female runaway youths: A quasi-experimental study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2018/09/02 2018;39(9):764-772. doi:10.1080/01612840.2018.1462871. [CrossRef]

- Noh D, Choi S. Development of a family-based mental health program for runaway adolescents using an intervention mapping protocol. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(21):7794.

- Brillantes-Evangelista G. An evaluation of visual arts and poetry as therapeutic interventions with abused adolescents. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 2013/02/01/ 2013;40(1):71-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2012.11.005. [CrossRef]

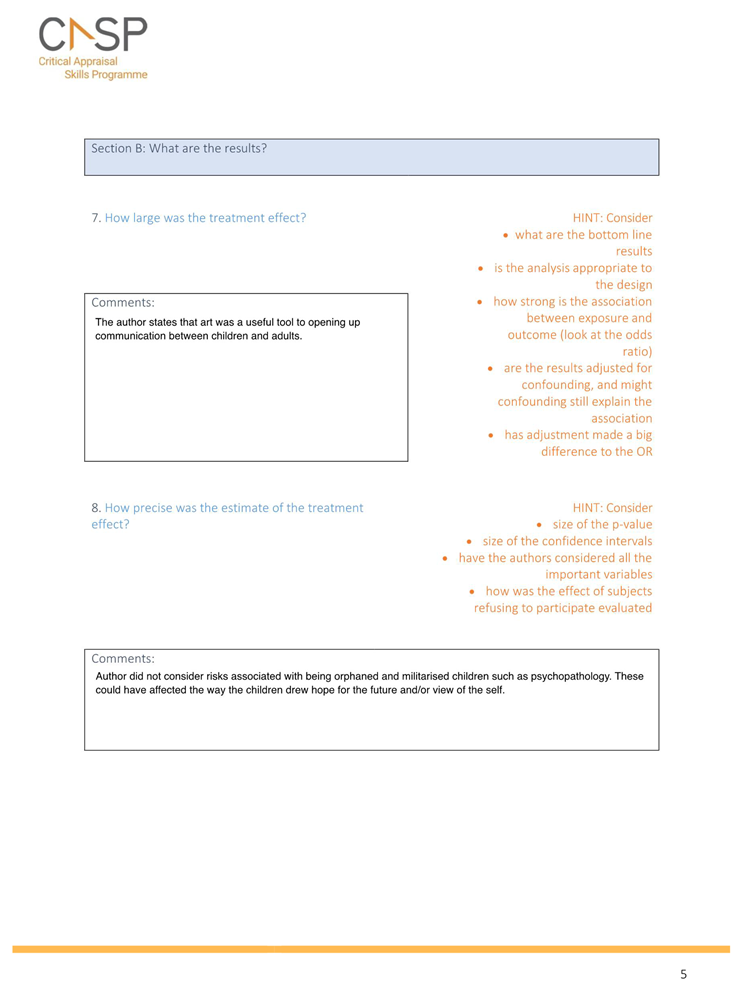

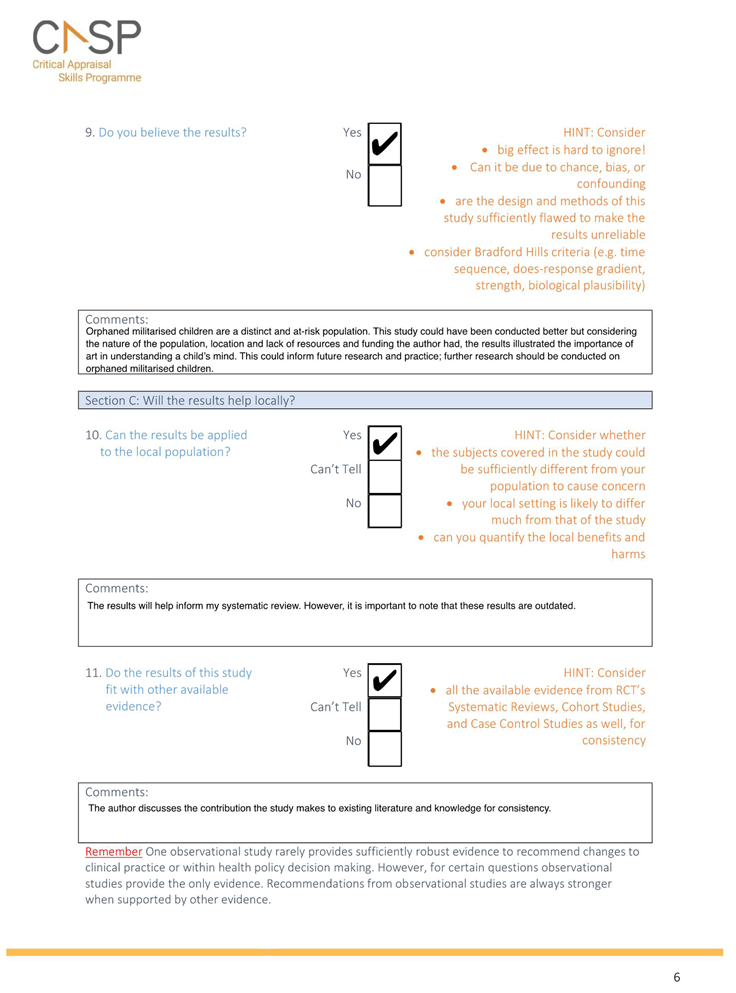

- Miles GM. Drawing together hope: 'listening' to militarised children. Journal of Child Health Care. 2000;4(4):137-142. https://doi.org/10.1177/136749350000400401. [CrossRef]

- The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ‘Southeast Asia, 1900 A.D.–present.’ In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/11/sse.html.

- The World Bank. Southeast Asian countries reach milestone agreement to strengthen resilience. https://www.worldbank.org/en/events/2017/05/05/southeast-asian-countries-reach-milestone-agreement.

- Corcoran K, Fischer J. Measures for clinical practice and research: A sourcebook. 3 ed. Simon & Schuster Inc. ; 2000.

- WK Z. A self-rating depression scale. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1965;12(1):63-70. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1965.01720310065008. [CrossRef]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. Jun 1961;4:561-71. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [CrossRef]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behav Res Ther. Mar 1995;33(3):335-43. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-u. [CrossRef]

- Greenwald R, Rubin A. Assessment of posttraumatic symptoms in children: Development and preliminary validation of parent and child scales. Research on Social Work Practice. 1999;9(1):61-75. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973159900900105. [CrossRef]

- Coopersmith S. The antecedents of self-esteem. Series of books in behavioral science. W.H. Freeman; 1967.

- Chang D. The effects of parent’s nurturing behaviour on self-esteem of children. Kyungbuk University; 1984.

- Lee Y, Song J. A study of the reliability and the validity of the BDI, SDS, and MMPI-D scales. Korean J Clin Psychol. 1991;10:98–113.

- Sherer M, Maddux JE, Mercandante B, Prentice-Dunn S, Jacobs B, Rogers RW. The self-efficacy scale: Construction and validation. Psychological Reports. 1982;51(2):663-671. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1982.51.2.663. [CrossRef]

- Oh H. Health promoting behaviours and quality of life of Korean women with arthritis. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. University of Texas, Austin; 1993.

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press; 1965.

- Jamil Mohd Y, Mohd B. Validity and reliability study of Rosenberg self-esteem scale in Seremban school children. Malaysian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;15:35-39.

- Smilkstein G. The family APGAR: a proposal for a family function test and its use by physicians. J Fam Pract. Jun 1978;6(6):1231-1239.

- Kang S, Yoon B, Lee H, Lee D, Shim U. A study of family APGAR scores for evaluating family function. Korean Academy of Family Medicine. 12 1984;5(12):6-13.

- Shin W, Kim M, Kim J. Developing measures of resilience for Korean adolescents and testing cross, convergent, and discriminant validity. Studies on Korean Youth. 2009;20(4):105–131.

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown G. Beck Depression Inventory–II (BDI-II) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. 1996;doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/t00742-000. [CrossRef]

- Kim J-H, Lee E-H, Hwang S-T, Hong S-H. Manual for the Korean BDI-II. Korea Psychology Corporation; 2014.

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, Steer RA. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J Consult Clin Psychol. Dec 1988;56(6):893-7. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.56.6.893. [CrossRef]

- Kim J-H, Lee E-H, Hwang S-T, Hong S-H. Manual for the Korean BAI. Korea Psychology Corporation; 2014.

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791-804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Life skills education for children and adolescents in schools: Introduction and guidelines to facilitate the development and implementation of life skills programme.

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer publishing company; 1984.

- Willis A, Isaacs T, Khunti K. Improving diversity in research and trial participation: The challenges of language. The Lancet Public Health. 2021;6(7):e445-e446. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00100-6. [CrossRef]

- Malchiodi CA. Art therapy, attachment, and parent-child dyads. Creative arts and play therapy for attachment problems. The Guilford Press; 2014:52-66. Creative arts and play therapy.

- Allen JD, Carter K, Pearson M. Frangible emotion becomes tangible expression: Poetry as therapy with adolescents. 2019:.

- Bowman DO, Halfacre DL. Poetry therapy with the sexually abused adolescent: A case study. The Arts in Psychotherapy. 1994/01/01/ 1994;21(1):11-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4556(94)90032-9. [CrossRef]

- Moula Z, Aithal S, Karkou V, Powell J. A systematic review of child-focused outcomes and assessments of arts therapies delivered in primary mainstream schools. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020/05/01/ 2020;112:104928. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104928. [CrossRef]

- Hackett SS, Ashby L, Parker K, Goody S, Power N. UK art therapy practice-based guidelines for children and adults with learning disabilities. International Journal of Art Therapy. 2017/04/03 2017;22(2):84-94. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1319870. [CrossRef]

- Rohde P, Clarke GN, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Kaufman NK. Impact of comorbidity on a cognitive-behavioural group treatment for adolescent depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40(7):795-802. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200107000-00014. [CrossRef]

- Shein-Szydlo J, Sukhodolsky DG, Kon DS, Tejeda MM, Ramirez E, Ruchkin V. A randomized controlled study of cognitive–behavioural therapy for posttraumatic stress in street children in Mexico City. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2016;29(5):406-414. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22124. [CrossRef]

- Ghodousi N, Sajedi F, Mirzaie H, Rezasoltani P. The effectiveness of cognitive-behavioural play therapy on externalising behaviour problems among street and working children. Original Research Articles. Iranian Rehabilitation Journal. 2017;15(4):359-366. https://doi.org/10.29252/nrip.irj.15.4.359. [CrossRef]

- Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A. The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy and Research. 2012/10/01 2012;36(5):427-440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-012-9476-1. [CrossRef]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191. [CrossRef]

- Kolubinski DC, Frings D, Nikčević AV, Lawrence JA, Spada MM. A systematic review and meta-analysis of CBT interventions based on the Fennell model of low self-esteem. Psychiatry Research. 2018/09/01/ 2018;267:296-305. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.025. [CrossRef]

- Falk CF, Heine SJ. What is implicit self-esteem, and does it vary across cultures? Personality and Social Psychology Review. 2015;19(2):177-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544693. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y, Ollendick TH. A cross-cultural and developmental analysis of self-esteem in Chinese and Western children. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2001/09/01 2001;4(3):253-271. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017551215413. [CrossRef]

- Bockting CL, Hollon SD, Jarrett RB, Kuyken W, Dobson K. A lifetime approach to major depressive disorder: The contributions of psychological interventions in preventing relapse and recurrence. Clinical Psychology Review. 2015/11/01/ 2015;41:16-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.02.003. [CrossRef]

- Yadav P, Iqbal N. Impact of life skill training on self-esteem, adjustment and empathy among adolescents. Journal of the Indian Academy of Applied Psychology. 01/01 2009;35(10):61-70.

- Winarsunu T, Iswari Azizaha BS, Fasikha SS, Anwar Z. Life skills training: Can it increases self esteem and reduces student anxiety? Heliyon. 2023;9(4)doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15232. [CrossRef]

- Maryam E, Davoud MM, Zahra G, somayeh B. Effectiveness of life skills training on increasing self-esteem of high school students. Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences. 2011/01/01/ 2011;30:1043-1047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.203. [CrossRef]

- Shin J, Baek J. The effect of self-esteem and social support on depression for middle-aged and elderly male homeless. Journal of the Korea Gerontological Society. 2010;30(4).

- Development Services Group Inc., & Child Welfare Information Gateway. Promoting protective factors for in-risk families and youth: A guide for practitioners U.S Department of Health and Human Services, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau; 2015.

- Lightfoot M, Stein JA, Heather T, Preston K. Protective factors associated with fewer multiple problem behaviours among homeless/runaway youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2011/11/01 2011;40(6):878-889. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.614581. [CrossRef]

- Hamdani SU, Zill e H, Zafar SW, et al. Effectiveness of relaxation techniques ‘as an active ingredient of psychological interventions’ to reduce distress, anxiety and depression in adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems. 2022/06/28 2022;16(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00541-y. [CrossRef]

- Alvord MK, Zucker BG, Grados JJ. Resilience Builder Program for children and adolescents: Enhancing social competence and self-regulation—A cognitive-behavioral group approach. 2011:.

- Swahn MH, Culbreth R, Tumwesigye NM, Topalli V, Wright E, Kasirye R. Problem drinking, alcohol-related violence, and homelessness among youth living in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2018;15(6):1061.

- Tyler KA, Johnson KA. Pathways in and out of substance use among homeless-emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2006;21(2):133-157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558405285494. [CrossRef]

- Rew L, Powell T, Brown A, Becker H, Slesnick N. An intervention to enhance psychological capital and health outcomes in homeless female youths. Western Journal of Nursing Research. 2016; 39(3):356–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945916658861. [CrossRef]

- Bandura A, Caprara GV, Barbaranelli C, Regalia C, Scabini E. Impact of family efficacy beliefs on quality of family functioning and satisfaction with family life. Applied Psychology: An International Review. 2011;60(3):421-448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2010.00442.x. [CrossRef]

- Pinto AC, Luna IT, Sivla Ade A, Pinheiro PN, Braga VA, Souza AM. Risk factors associated with mental health issues in adolescents: An integrative review. Rev Esc Enferm USP. Jun 2014;48(3):555-64. Fatores de risco associados a problemas de saúde mental em adolescentes: revisão integrativa. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0080-623420140000300022. [CrossRef]

- Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ. Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behaviour: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998/03/01 1998;1(1):61-75. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021800432380. [CrossRef]

- Centrepoint. Independent living programme. https://centrepoint.org.uk/what-we-do/independent-living-programme.

- Centrepoint. How we can end youth homelessness. 2024;

- World Health Organisation. Traditional medicine in the WHO South-East Asia Region: Review of progress 2014–2019. World Health Organisation. Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2020.

- Johnson RB, Onwuegbuzie AJ, Turner LA. Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):112-133. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224. [CrossRef]

- Abramovich I. LGBTQ youth homelessness in Canada: Reviewing the Literature. Canadian Journal of Family and Youth/Le Journal Canadien de Famille et de la Jeunesse. 2012;4(1):29-51. https://doi.org/10.29173/cjfy16579. [CrossRef]

- OHCHR. Equal Asia Foundation’s inputs to the UN special rapporteur on housing. Understanding the sheltering and housing needs of LGBTIQ+ persons in Asia. https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/issues/housing/climate/submissions/2022-10-24/Submission-ClimateChange-CSO-EqualAsiaFoundation_0.docx.

- Feng Y, Lou C, Gao E, et al. Adolescents' and young adults' perception of homosexuality and related factors in three Asian cities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(3):S52-S60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.12.008. [CrossRef]

- United Nations. End of mission statement to Republic of Korea. UN Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner. https://www.ohchr.org/en/statements/2018/05/end-mission-statement-republic-korea?LangID=E&NewsID=23116.

- United Nations Department of Economics and Social Affairs. Sustainable Development Goals. (2023) https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).