Introduction

Emotional intelligence (EI) stands as a cornerstone in the domain of nursing leadership, exerting a profound influence on organizational dynamics, team cohesion, and ultimately, the delivery of superior patient care (Coronado-Maldonado & Benítez-Márquez 2023). Over time, there has been an increasing acknowledgment of the indispensable role EI plays in sculpting effective leadership paradigms within healthcare contexts. The contemporary healthcare milieu necessitates leaders who not only possess clinical acumen but also exhibit a heightened sense of emotional intelligence. Nurses, serving at the forefront of healthcare delivery, uniquely straddle the realms of technical proficiency and compassionate patient-centricity (Almutari & Almutairi, 2023; Germain, & Cummings, 2010). Thus, grasping the intricacies of emotional intelligence assumes paramount importance in nurturing adept nursing leadership.

The Problem

Despite the widely recognized significance of emotional intelligence, a notable void persists in our comprehension of its precise ramifications on nursing leadership dynamics, particularly within the domain of Primary Health Care (PHC). This gap in the literature underscores the need for further exploration into how emotional intelligence intersects with leadership models specifically tailored to PHC nurses. Fundamental questions endure regarding the degree to which emotional intelligence shapes effective leadership practices in PHC settings and its correlation with critical outcomes such as team cohesion, job satisfaction, and patient well-being.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this study was to record, investigate and evaluate the EI of PHC nurses and the leadership models adopted in PHC units, after educational intervention or not.

Research Cases

Hypothesis 1: Nurses undergoing the educational intervention will demonstrate a significant increase in emotional intelligence scores compared to those in the control group.

Hypothesis 2: The intervention group will show greater adoption of transformational leadership styles compared to the control group after the educational intervention.

Materials & Methods

Research Design

This study employed a longitudinal experimental design to investigate the impact of an educational intervention on EI and leadership among nurses working in PHC structures in Greece. The survey questionnaire was distributed to nurses in both the intervention and control groups. For the intervention group, nurses completed the questionnaire before and after the educational intervention within a week. In contrast, nurses in the control group completed the questionnaire twice, with no intervention, within one month. Sampling employed proportional stratified and simple random sampling methods to ensure representativeness across different regions of Greece.

The study consisted of two phases conducted over a period from May 2022 to December 2022. A probability sample of nurses was randomly assigned to either the intervention group or the control group.

Participants

The study included 101 higher education nurses from various PHC facilities across Greece, selected through proportional stratified and simple random sampling to ensure representation from both urban and provincial settings. Participants were divided into two groups: 50 in the intervention group and 51 in the control group. According to the power analysis, for this particular survey design it was estimated that the total number of participants should be at least 100 (50 per group), which provides 90% power with an effect size equal to 0.30 for the between-group comparison, 95% power with an effect size equal to 0.18 for the comparison between two time points, and 95% power with an effect size equal to 0.18 to control for the interaction term. Eligible participants were active nursing practitioners in PHC settings, fluent in Greek, with a tertiary education degree in nursing, and provided voluntary consent to participate. Exclusion criteria encompassed non-nursing paramedical staff, nursing assistants with less than three years of training, individuals employed in secondary or tertiary health institutions, and those unwilling to participate, ensuring the sample's homogeneity and alignment with the study's objectives.

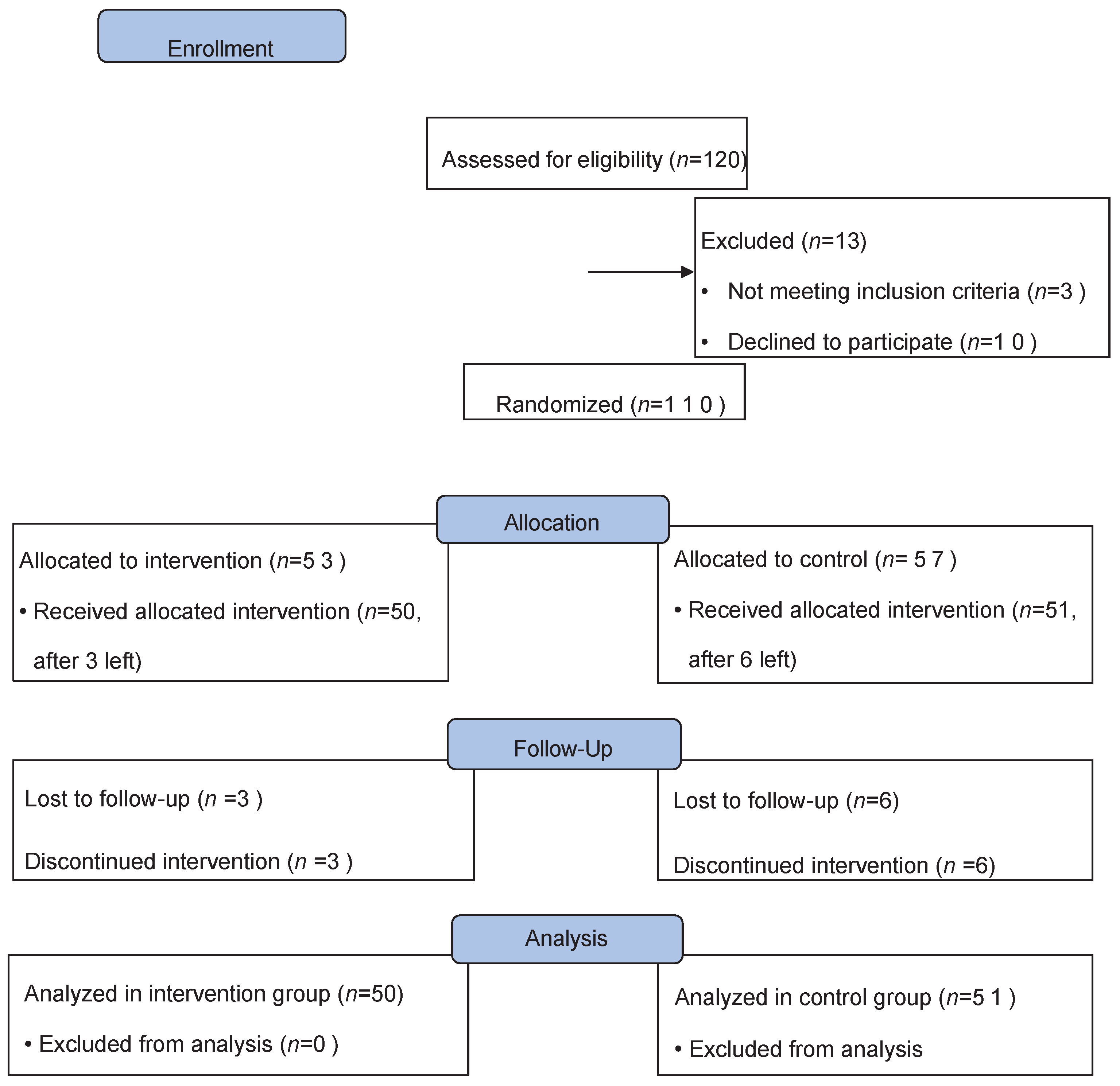

The CONSORT flowchart illustrates the progression of study participants through phases of the randomized trial, from assessment of eligibility to analysis. Exclusions, allocations to intervention/control groups, follow-up and final analysis numbers are detailed in the chart below (

Figure 1):

Educational Intervention

The educational intervention delivered to the intervention group aimed to enhance participants' understanding of EI and its implications for leadership in healthcare settings. The intervention covered topics such as the importance of EI in personal and professional contexts, various leadership models, and the correlation between EI and effective leadership. Case studies were presented to facilitate reflection and discussion among participants.

The intervention for the intervention group included a one-hour session covering EI, its advantages, typical leadership styles, and the noted link between EI and leadership based on existing research.

Statistical Methods:

The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (version 26.0) (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences). Descriptive statistics, such as means, standard deviations, frequencies, and percentages, summarized participant characteristics and questionnaire responses. Inferential statistics, including t-tests and correlation analyses, examined differences between groups and relationships between variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Any missing data or outliers were addressed using appropriate techniques to ensure the integrity of the analysis. Additionally, multivariate analyses were undertaken to comprehensively explore the interplay of multiple variables within the dataset, further enhancing the depth of the statistical examination.

Quantitative variables were expressed as mean values (SD), while qualitative variables were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. For the comparison of proportions chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used. Independent samples Student’s t-tests were used for the comparison of mean values between the two groups. Repeated measurements analysis of variance (ANOVA) was adopted to evaluate the changes observed in MLQ and EI scores between control and intervention group over the follow up period as well as between employees and supervisors of the intervention group.

Ethical Considerations

Upon request, the conduct of the research was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica in Greece (No.Prot.: 12758-16/02/2022) and by the scientific councils of all the Health Regions of Greece. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their involvement in the study. The confidentiality and anonymity of participant data were rigorously upheld throughout all stages of the research process, ensuring compliance with ethical standards and safeguarding participant privacy and rights.

In addition to obtaining ethical approval and informed consent, the study was registered in a public registry that aligns with WHO criteria. The trial details, including Trial ID 75188, are accessible in the IRCT registry, ensuring transparency and adherence to ethical standards.

Results

The results section contains five tables summarizing the findings of the study.

Table 1 provides demographic and job-related characteristics of the study participants, divided into control and intervention groups.One hundred and one participants were entered in the study (50 in the intervention group and 51 in the control one). It includes data on gender, age, family status, educational level, specialty, working position, type of primary care facility, employment status, working shift, years of nursing experience, and job satisfaction levelsNo significant differences were found between the two groups as far as their characteristics is concerned.

Table 2 focuses on the changes in emotional intelligence subscales measured before and after the intervention, comparing control and intervention groups. It evaluates four key areas: self-emotion appraisal, emotion appraisal of others, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion. For each subscale, mean scores before and after the intervention, the change observed, and p-values indicating the significance of these changes are presented. This table shows how the intervention group experienced statistically significant improvements in their emotional intelligence capabilities compared to the control group. The degree of change of all EI scores differed significantly between the two groups, since only in the intervention group significant increases were detected.

Table 3 examines changes in leadership styles and outcomes, utilizing the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) framework. It looks at transformational, transactional leadership styles, management by exception, passive & laissez-faire leadership, extra effort, effectiveness, and satisfaction with leadership. Pre- and post-intervention mean scores, the change between these two points, and p-values are reported, indicating the impact of the educational intervention on leadership behaviors and perceptions among the nurses.

At baseline no significant differences were found between the two groups. However, at follow-up the intervention group had significantly greater score in Management by exception Passive & Laissez-Faire Leadership compared to the control group. Also, there was a significant increase in the Management by exception Passive & Laissez-Faire Leadership style score of the intervention group at follow-up compared to baseline measurement. The degree of change was similar in Transformational and Transactional styles but in the Management by exception – Passive & Laissez-Faire Leadership styles it differ significantly between the two groups.

Initially, extra effort and satisfaction with the leadership scores were significantly greater in the intervention group, while at follow-up no significant differences were found between the two groups. Significant time differences were not found in the leadership outcomes as well as significant differences in the degree of their change.

Table 4 delves into specific elements of leadership measured by the MLQ, such as idealized influence (attributed and behavior), inspirational motivation, intellectual stimulation, individual consideration, contingent reward leadership, and management by exception (active and passive). Like the previous tables, it compares the pre- and post-intervention scores and changes for both groups, providing insights into the nuanced ways in which the intervention influenced various aspects of leadership.

At baseline, the intervention group had significantly greater Inspirational Motivation score compared to the control group. All other scores were similar at baseline between the two groups. At follow-up no significant differences were found between the two groups. When, scores were compared through time, it was found that only Management – by exception (Passive) and Laissez-Faire Leadership scores were increased at follow-up and specifically only in the intervention group.

Focusing exclusively on the intervention group,

Table 5 analyzes changes in emotional intelligence and leadership styles based on the participants' working positions (employees vs. supervisors). It covers management by exception (passive), laissez-faire leadership, and a combined score for these two styles, in addition to self-emotion appraisal, emotion appraisal of others, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion. The table presents mean scores before and after the intervention, changes observed, and p-values to evaluate the differential impact of the intervention on employees and supervisors.

Score in “management – by exception (Passive)” increased significantly at follow-up only in participants who were supervisors, while scores in Laissez-Faire Leadership element, Management by exception – Passive & Laissez-Faire Leadership style and almost all EI subscales (except for Regulation of emotion) increased significantly at follow-up only in participants who were not supervisors. At baseline, supervisors had significantly lower scores in “management – by exception (Passive)”. Also, supervisors had significantly lower scores in Management by exception – Passive & Laissez-Faire Leadership style at both measurements.

Discussion

The discussion of our study's findings, particularly those elucidated in

Table 2 and

Table 3, reveals intriguing parallels and deviations from existing literature on EI and leadership styles in nursing. The educational intervention aimed at enhancing EI and leadership styles among Greek Primary Health Care nurses yielded significant improvements, particularly in the intervention group compared to the control group. This study, through a longitudinal experimental design, utilized the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS) and Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) to measure changes pre- and post-intervention.

Table 2 highlighted significant improvements in all four subscales of emotional intelligence for the intervention group. These enhancements in self-emotion appraisal, emotion appraisal of others, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion demonstrate the effectiveness of the intervention in bolstering the emotional competencies of nurses, critical for patient care and team dynamics.

Our analysis indicates a significant increase in emotional intelligence subscales, including self-emotion appraisal and emotion regulation, for the intervention group. This aligns with the research by Brackett, Rivers, and Salovey (2011), which emphasizes the malleability of EI through targeted educational programs. Their findings corroborate our observations that structured interventions can enhance crucial EI components among healthcare professionals, thereby supporting the hypothesis that EI is not an innate trait but can be developed through specific educational efforts. However, the shift towards more passive and laissez-faire leadership styles post-intervention presents a complex scenario. While traditional literature posits transformational leadership as the gold standard for nursing leadership due to its association with positive patient outcomes and workplace environments, our study suggests an unintended consequence of the intervention. This is somewhat reflected in the work of Skogstad et al. (2007), who explored the negative impact of laissez-faire leadership on job satisfaction and employee health, underscoring the potential challenges these leadership styles pose to effective nursing practice.

Interestingly, the increase in management by exception and laissez-faire leadership contrasts with findings from Cummings et al. (2010), who advocate for transformational leadership to enhance patient care and nursing work environments. Our study's divergence from this established narrative invites further exploration into the nature of the educational intervention and its potential biases towards fostering less proactive leadership behaviors. The consistency in emotional intelligence improvement yet variability in leadership style outcomes raises questions about the direct translation of EI gains into leadership practices. This discrepancy suggests that while EI can be enhanced, translating these improvements into desired leadership behaviors may require a more nuanced approach or additional components within educational interventions. This observation is supported by Mayer, Caruso, and Salovey (2016), who argue that the application of EI in leadership extends beyond mere capability enhancement to include the strategic deployment of these skills in leadership practices.

This shift is particularly relevant in healthcare, where leadership styles directly influence patient care quality and team cohesion (Wong and Cummings, 2009). For instance, the diversity in age, educational level, and years of experience within the sample can provide insights into how these factors might influence the receptiveness to and impact of the educational intervention. Research by Day and Carroll (2004) suggests that individual differences can significantly affect the development of EI and leadership capabilities, which might explain the variance in outcomes observed across different participant groups.

The study's findings align with existing literature on emotional intelligence (EI) and nursing leadership, as highlighted by Jiménez-Rodríguez et al. (2022), Fouad et al. (2018), and Russ et al. (2023). These studies emphasize the importance of EI training interventions in enhancing EI competencies among nursing professionals. While Jiménez-Rodríguez et al. (2022) focused on undergraduate nursing students and the effects of a non-technical skills training program on EI and resilience, Fouad et al. (2018) examined the impact of emotional intelligence training on nursing students' EI and empathy levels. Despite differences in methodologies and target populations, these studies collectively underscore the potential benefits of EI development in healthcare settings. Our study enhances emotional intelligence (EI) and leadership styles among Greek Primary Health Care nurses through educational intervention, showing significant EI improvements and a shift towards transformational leadership, aligning with Russ et al. (2023). They highlight Trait EI's critical role in healthcare leadership, emphasizing its development for leadership efficacy. Unlike Russ et al.’s broad analysis, our empirical evidence demonstrates targeted interventions' effectiveness in developing EI and leadership, supporting the notion that EI can be nurtured through specific training programs.

The comparison between our study and Imperato and Strano-Paul (2021) reveals insightful parallels and contrasts in the application and effects of educational interventions on EI, as measured by the Wong and Law Emotional Intelligence Scale (WLEIS). Both research endeavors employ the WLEIS, underscoring its utility in evaluating EI's four dimensions: self-emotion appraisal, others' emotion appraisal, use of emotion, and regulation of emotion. The interventions, aimed at enhancing EI, differ significantly in focus and structure; ours is directed at Greek Primary Health Care nurses to boost EI and leadership skills, whereas Imperato and Strano-Paul's initiative encourages reflection among medical students to augment empathy and indirectly, EI. This distinction highlights the differing impacts of the interventions; while we observed a marked improvement in EI and a shift towards transformational leadership, Imperato and Strano-Paul noted a significant rise in empathy but no change in overall EI scores.

The study by Metwally et al., (2014) on transformational leadership within a multinational FMCG company in Egypt provides a context for comparing with our research on leadership styles in Greek Primary Health Care settings, both employing the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ). Metwally et al.'s research concentrated on how transformational leadership influences employee satisfaction in a corporate environment, affirming that dimensions like Idealized Influence and Inspirational Motivation significantly boost job satisfaction. This aligns with findings from Mohammad et al. (2011), who similarly highlighted the positive impact of transformational leadership on satisfaction and performance within organizational settings. Metwally et al. (2014) underscore the direct correlation between transformational leadership and job satisfaction, mirroring broader research that suggests engaged, visionary leadership can profoundly affect corporate morale and employee retention. In contrast, our research suggests that while similar interventions can foster positive leadership traits in healthcare, the impact on practical outcomes like patient care and team dynamics requires further exploration.

Compared to the study by Alqahtani et al. (2021), which examined leadership styles and job satisfaction among healthcare providers in primary health care centers in Saudi Arabia, our research focuses on similar themes but in a different context. Alqahtani et al. (2021) utilized a cross-sectional design, employing the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ, Form 6-S) along with a job satisfaction survey to evaluate the leadership practices of PHCC managers and assess job satisfaction among 300 healthcare providers. Their results highlighted a predominant use of transformational leadership elements like 'idealized influence' and a significant reliance on 'management by exception', while laissez-faire leadership was less common. They found varied levels of job satisfaction, with a considerable number of healthcare providers reporting ambivalence towards their jobs.

Research conducted by Tyczkowski et al. (2015) and Carragher & Gormley (2017) highlights the essential role of Emotional Intelligence (EI) in nursing leadership. These studies collectively emphasize EI's crucial role in developing effective nursing leadership, advocating for the incorporation of EI development into nursing education programs. There is a consensus among these studies that EI is a foundational component of transformational leadership, which is vital for effectively navigating the complexities of healthcare environments. A distinctive feature of our study, however, is the implementation of a specific educational intervention designed to enhance EI and investigate its direct impact on leadership styles. Whereas Tyczkowski et al. (2015) focused on establishing correlations between existing levels of EI and leadership styles, and Carragher & Gormley (2017) explored the theoretical implications of EI for leadership development, our research provides empirical evidence that supports the effectiveness of targeted interventions in simultaneously boosting EI and leadership competencies among nurses.

Sabbah et al. (2020) explored leadership styles and their impact on nurses' well-being in Lebanon using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) 5x Short Form, similarly to our study which also employed the MLQ to evaluate leadership styles in Greek Primary Health Care. In their analysis, Sabbah et al. (2020) observed that transformational and transactional leadership styles were prevalent and positively associated with nurse well-being. These findings echo our results, where transformational leadership significantly enhanced leadership behavior and effectiveness post-intervention. Similarly, transactional leadership in both studies showed a positive influence, although the specifics of impact varied, reflecting contextual differences in setting and healthcare practices.The consistent use of the MLQ across both studies provides a robust framework for comparing the direct impacts of leadership behaviors on healthcare outcomes, emphasizing the universal relevance of effective leadership in enhancing operational efficiency and employee morale in healthcare.

Cope & Murray (2017) provided an expansive overview of leadership and leadership styles relevant to nursing, advocating for the significance of effective leadership in enhancing healthcare outcomes. Their discourse on transformational and transactional leadership styles, and the necessity for nurses to develop these competencies, mirrors our study's emphasis on the educational development of EI and its impact on leadership behavior.Another distinction is the observation in our study regarding the shifts towards less effective leadership styles (management by exception and laissez-faire) in the absence of targeted interventions. This particular insight adds depth to the discourse on leadership dynamics in healthcare, highlighting the potential for educational interventions to not only promote effective leadership styles but also mitigate the drift towards less desirable leadership behaviors (Hargreaves, & Fink, 2012; Zimmerman, et al., 2015; Katigbak, et al., 2015).

At this point it would be useful to elaborate on the limitations faced by our research. (1) The survey was conducted amid the Covid-19 pandemic. The given moment may have affected the psychology and overall mood of nurses, stress levels, job satisfaction and working conditions, etc. The pandemic probably also affected the nursing leadership, which suddenly had to act decisively, tested, facing new and unprecedented data. Therefore, leadership models may have changed. (2) The educational intervention took place only once (duration of approximately 1 hour). A more systematic and comprehensive program of longer duration aimed at the development of emotional intelligence as well as the development and improvement of nurses' leadership skills could have been designed. (3) The WLEIS scale, which was used to measure emotional intelligence, is a self-report psychometric tool, meaning that participants subjectively rated the dimensions of emotional intelligence according to their own personal beliefs. Also, the MLQ captures the views of nurses regarding the leadership model that they consider to be applied in their workplace. (4) A scale related to nurses' job satisfaction could have been included during the research design for further investigation.

Conclusions

The study successfully addressed its main objectives by demonstrating the effectiveness of educational interventions in enhancing nurses' EI and influencing their leadership styles. Participants who underwent the intervention showed significant improvements in EI and a shift towards more transformational leadership styles, unlike the control group. These findings underscore the importance of integrating EI development into nursing education and professional training to foster compassionate care, improve team dynamics, and enhance patient outcomes.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgments

We express gratitude to Professor Mr. Kafetsios Konstantinos for granting permission to utilize the Emotional Intelligence scale. Appreciation extends to all participating nurses for their invaluable contribution to the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

Guidelines and Standards Statement

CONSORT guidelines were followed.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University of West Attica (No. Prot: 12758-16/02/2022), on the other hand by the scientific councils of all the health districts of Greece. In addition the study was registered in the Iranian Registry of Clinical Trial (IRCT) (Trial ID 75188).

Human and Animal Rights

No animals were used in this research. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

Consent for Publication

Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data are available with the corresponding author on request.

References

- Akerjordet, K., & Severinsson, E. (2010). The state of the science of emotional intelligence related to nursing leadership: an integrative review. Journal of nursing management, 18(4), 363-382.

- Alqahtani, A., Nahar, S., Almosa, K., Almusa, A. A., Al-Shahrani, B. F., Asiri, A. A., & Alqarni, S. A. (2021). Leadership styles and job satisfaction among healthcare providers in primary health care centers. Middle east journal of family medicine, 19(3).

- Almutari, M. S. W., & Almutairi, W. S. W. (2023). Nursing Leadership and Management: Theory, Practice, and Future Impact on Healthcare. Mohammed Saad WaslallahAlmutari.

- Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Transformational leadership and organizational culture. The International journal of public administration, 17(3-4), 541-554.

- Brackett, M. A., Rivers, S. E., & Salovey, P. (2011). Emotional intelligence: Implications for personal, social, academic, and workplace success. Social and personality psychology compass, 5(1), 88-103.

- Carragher, J., & Gormley, K. (2017). Leadership and emotional intelligence in nursing and midwifery education and practice: a discussion paper. Journal of advanced nursing, 73(1), 85-96.

- Codier, E., Kamikawa, C., & Kooker, B. M. (2011). The impact of emotional intelligence development on nurse managers. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 35(3), 270-276.

- Cope, V., & Murray, M. (2017). Leadership styles in nursing. Nursing Standard, 31(43).

- Cummings, G., Lee, H., MacGregor, T., Davey, M., Wong, C., Paul, L., & Stafford, E. (2008). Factors contributing to nursing leadership: a systematic review. Journal of health services research & policy, 13(4), 240-248.

- Cummings, G. G., MacGregor, T., Davey, M., Lee, H., Wong, C. A., Lo, E.,... & Stafford, E. (2010). Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: a systematic review. International journal of nursing studies, 47(3), 363-385.

- Cummings, G. G., Tate, K., Lee, S., Wong, C. A., Paananen, T., Micaroni, S. P., & Chatterjee, G. E. (2018). Leadership styles and outcome patterns for the nursing workforce and work environment: A systematic review. International journal of nursing studies, 85, 19-60.

- Coronado-Maldonado, I., & Benítez-Márquez, M. D. (2023). Emotional intelligence, leadership, and work teams: A hybrid literature review. Heliyon.

- Day, A. L., & Carroll, S. A. (2004). Using an ability-based measure of emotional intelligence to predict individual performance, group performance, and group citizenship behaviours. Personality and Individual differences, 36(6), 1443- 1458.

- Cummings, G., Lee, H., MacGregor, T., Davey, M., Wong, C., Paul, L., & Stafford, E. (2008). Factors contributing to nursing leadership: a systematic review. Journal of health services research & policy, 13(4), 240-248.

- Germain, P. B., & Cummings, G. G. (2010). The influence of nursing leadership on nurse performance: a systematic literature review. Journal of nursing management, 18(4).

- Farghally, S. M., Nabawy, Z. M., & Osman, L. H. (2015). The Relationship between Emotional Intelligence and Effective Leadership of the First-Line Nurse Managers. Alexandria Scientific Nursing Journal, 15(2), 30-54.

- Fouad, N. M., Gamal Al Dean, A. M., Lachine, O. A., & Moussa, A. A. (2018). Effect of Emotional Intelligence Training Intervention on Nursing Students’ Emotional Intelligence and Empathy Level. Alexandria Scientific Nursing Journal, 20(2), 97-114.

- Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2012). Sustainable leadership. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kafetsios, K., &Zampetakis, L. A. (2008). Emotional intelligence and job satisfaction: Testing the mediatory role of positive and negative affect at work. Personality and individual differences, 44(3), 712-722.

- Imperato, A., & Strano-Paul, L. (2021). Impact of reflection on empathy and emotional intelligence in third-year medical students. Academic Psychiatry, 45, 350-353.

- Jiménez-Rodríguez, D., Molero Jurado, M. D. M., Pérez-Fuentes, M. D. C., Arrogante, O., Oropesa-Ruiz, N. F., &Gázquez-Linares, J. J. (2022, May). The effects of a non- technical skills training program on emotional intelligence and resilience in undergraduate nursing students. In Healthcare (Vol. 10, No. 5, p. 866). MDPI.

- Katigbak, C., Van Devanter, N., Islam, N., & Trinh-Shevrin, C. (2015). Partners in health: a conceptual framework for the role of community health workers in facilitating patients' adoption of healthy behaviors. American journal of public health, 105(5), 872- 880.

- Kooker, B. M., Shoultz, J., &Codier, E. E. (2007). Identifying emotional intelligence in professional nursing practice. Journal of professional nursing, 23(1), 30-36.

- Mayer, J. D., Caruso, D. R., & Salovey, P. (2016). The ability model of emotional intelligence: Principles and updates. Emotion Review, 8(4), 290–300. [CrossRef]

- Metwally, A. H., El-Bishbishy, N., & Nawar, Y. S. (2014). The impact of transformational leadership style on employee satisfaction. The Business & Management Review, 5(3), 32-42.

- Mohammad, S., Ibraheem, S., AL-Zeaud, H., &Batayneg, A. M. (2011). The relationship between transformational leadership and employees' satisfaction at Jordanian private hospitals. Business and Economic Horizons (BEH), 5(2), 35- 46.

- Russ, S., Perazzo, M. F., & Petrides, K. V. (2023). 11. The role of trait emotional intelligence in healthcare leadership. Research Handbook on Leadership in Healthcare, 188.

- Sabbah, I. M., Ibrahim, T. T., Khamis, R. H., Bakhour, H. A. M., Sabbah, S. M., Droubi, N. S., &Sabbah, H. M. (2020). The association of leadership styles and nurses well- being: a cross-sectional study in healthcare settings. Pan African Medical Journal, 36(1).

- Skogstad, A., Einarsen, S., Torsheim, T., Aasland, M. S., & Hetland, H. (2007). The destructiveness of laissez-faire leadership behavior. Journal of occupational health psychology, 12(1), 80.

- Tyczkowski, B., Vandenhouten, C., Reilly, J., Bansal, G., Kubsch, S. M., &Jakkola, R. (2015). Emotional intelligence (EI) and nursing leadership styles among nurse managers. Nursing administration quarterly, 39(2), 172-180.

- Wong, C. A., & Cummings, G. G. (2009). The influence of authentic leadership behaviors on trust and work outcomes of health care staff. Journal of Leadership Studies, 3(2), 6-23.

- Zimmerman, E. B., Woolf, S. H., & Haley, A. (2015). Understanding the relationship between education and health: a review of the evidence and an examination of community perspectives. Population health: behavioral and social science insights. Rockville (MD): Agency for Health-care Research and Quality, 22(1), 347-84.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).