Submitted:

21 May 2024

Posted:

22 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. An Age of Climate Emergency

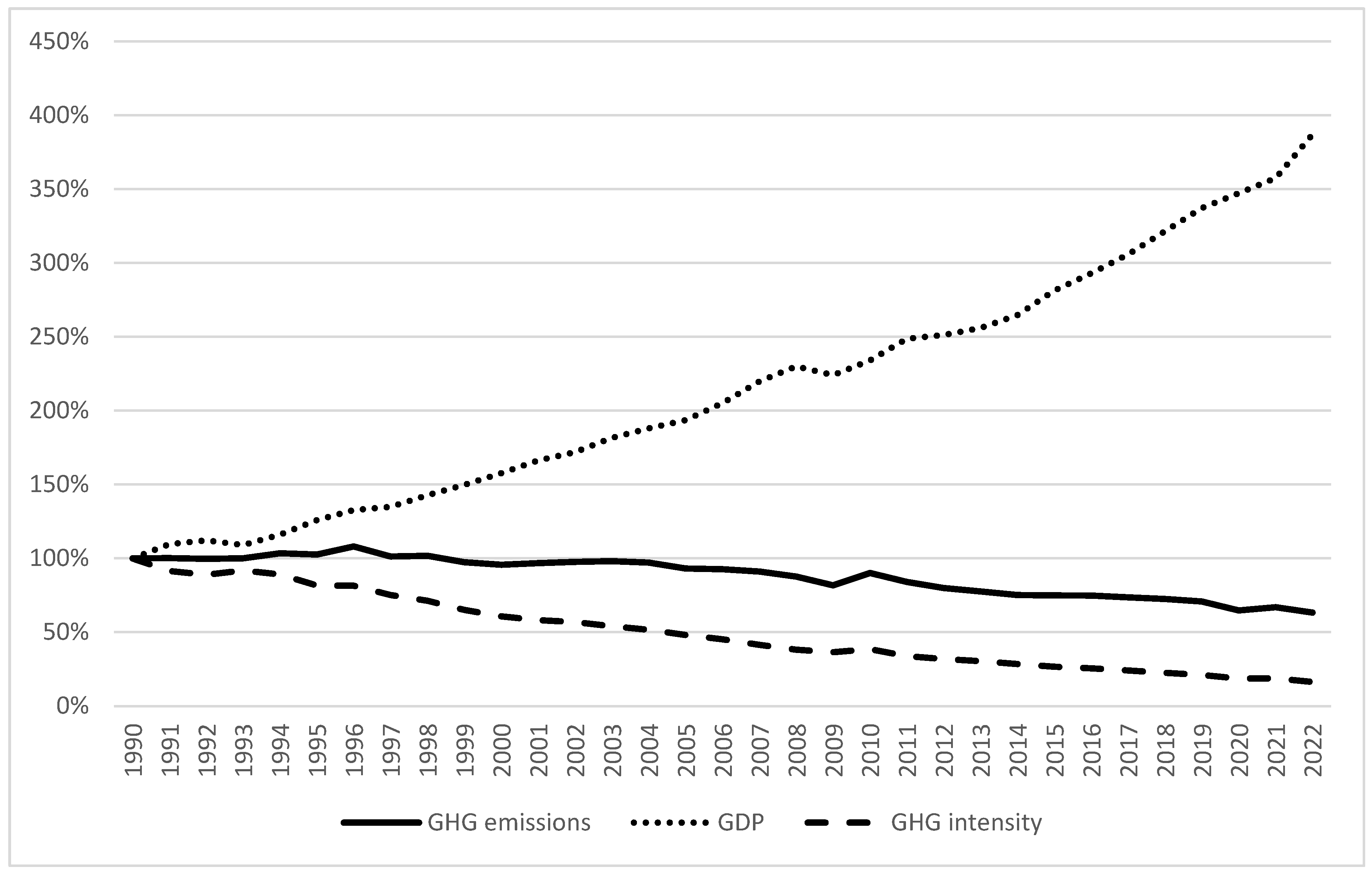

1.2. Sweden – A Role Model on Decline

- a target that Sweden should have net-zero emissions of GHGs and be climate neutral by 2045 the latest.

- a Climate Act,1 stating that the government must present policies for reaching the target, present to the Riksdag annual climate reports in the budgetary bill and a Climate Action Plan (CAP) at the latest the calendar year after general elections to the Riksdag, and

- the establishment of the Swedish Climate Policy Council (SCPC)2, an independent, interdisciplinary expert body of distinguished researchers on climate change and climate policy tasked with evaluating how well the government’s overall policy is aligned with the climate target of net-zero GHG emissions by 2045.

- Emissions in 2020 should be 40 per cent lower than emissions in 1990 (target achieved),

- Emissions in 2030 should be 63 per cent lower than emissions in 1990,

- Emissions from domestic transport, excluding domestic aviation, should be at least 70 per cent lower by 2030 compared to 2010, and

- Emissions in 2040 should be 75 percent lower than emissions in 1990.

1.3. Aim of the Paper

- RQ1

- How does the M-KD-L-SD climate policy impact democratic norms such as legitimacy, accountability and justice in democratic climate governance?

- RQ2

- How can potential democratic deficits of the M-KD-L-SD strategies be explained?

2. Climate Governance and Democracy

2.1. Theories on the Environment–Democracy Nexus

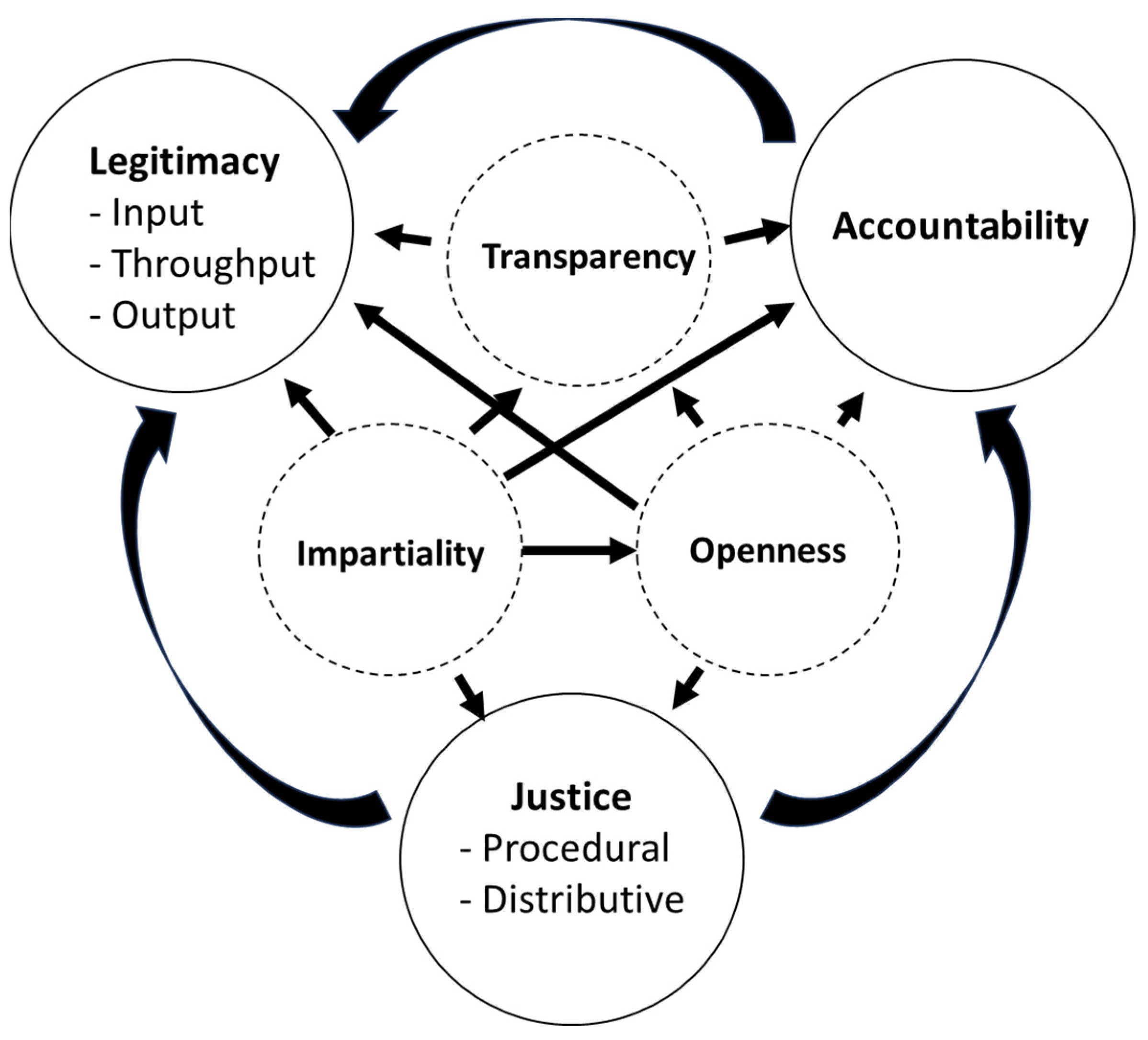

2.2. Democratic Norms and Principles

2.2.1. Legitimacy

2.2.2. Accountability

2.2.3. Justice

2.2.4. Potential Conflicts between Democratic Norms

3. Method and Material

4. Swedish Climate Governance with the Tidö Government

4.1. Recent Policy Changes and Proposals

- ensure access to fossil-free electricity (including a strong expansion of the electrical system with expanded nuclear power), charging infrastructure and power grids to enable new connections of fossil-free facilities and charging of electric vehicles, and meet the expected increased demand for fossil-free electricity and power throughout the country,

- price GHG emissions, and

- provide incentives for negative emissions including biofuel carbon capture and storage.

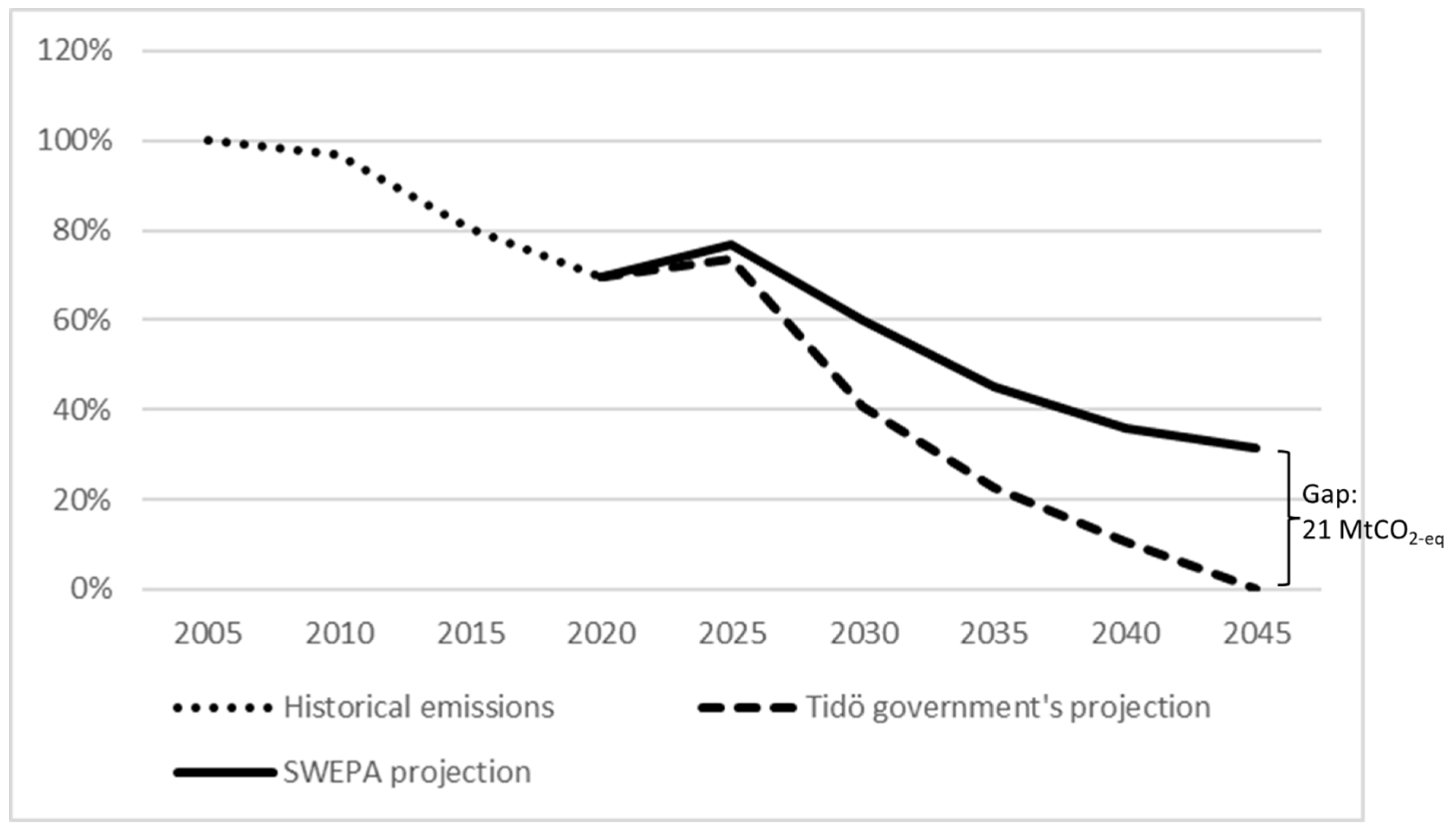

4.2. Entrepreneurial Strategies

- To have time to implement its policy reforms during the 2022–2026 mandate period, the Tidö government often applies shortened periods for official inquiries and referral times in public consultations, from the normal three months down to as little as half a working day. Prime Minister Kristiansson has told that inquiries should be made in half the time since the paradigm shift is urgent and that “accuracy is no excuse for slowness. On the contrary, speed has its own value. Not only in sports and in business. We must show that change is entirely possible”.35 As an example, the proposal to repeal the climate-smart travel tax deduction was submitted for two weeks consultation in October 2022. A more blatant example is the consultation of documentation in December 2022 for a bill on changed confidentiality linked to the handling of electricity subsidies for households. In both cases, the opportunity for those concerned to analyse and provide substantiated answers to the government’s proposals was reduced. But after the widespread critique of the CAP, the government buried climate policy to reach short term targets in an public inquiry that will present its findings and proposals only in 2027, after the next elections to the Riksdag and with very little time for implementing policies that must reduce GHG emissions more drastically, and to a higher cost. The Tidö parties will delay climate action at least four years.

- Decisions, proposals and actions that limit citizen’s rights in various ways or undermine important principles in the rule of law. An example in the climate area is the changed criminal classification of traffic blockades carried out by climate activists at demonstrations, employed by prosecutors and courts since 2023, from ‘disobedience to law enforcement’ to ‘sabotage’.36 This change was advocated by then legal policy spokespersons Tobias Andersson (SD) and Johan Forsell (M) already in 2022, before the new practice in the judicial system. It has later been supported by minister of justice Gunnar Strömmer (M)37, saying that the actions of climate activists must be seen as sabotage so that they can be sentenced to prison.

- Proposals and actions that attack public service and independent media and can discourage critical scrutiny of power. For example, repealing of press support, i.a. to independent media that review climate and environmental policy. In addition, a review of guidelines for public service, with SD being critical towards public service. According to the review of public service, journalism in the future must be evaluated by external reviewers, among other things based on how they manage to reach the groups where trust is currently at its lowest, i.e. SD voters (Swedish government, 2024b). This means that public service may have to adapt the content to a certain type of political opinion. This goes against basic journalistic principles of impartiality, neutrality of consequences and truth-seeking (Bjereld, 2024). In early February 2024, the Swedish far-right movement protested outside the headquarters of Swedish public service television and radio, accusing them of not being versatile enough – not giving space and time to conspiracy theories.38 As a response, Swedish public service television SVT refused to report from the largest ever climate action in Sweden, organized by Mother Rebellion, a subgroup of XR, in April 2024. 39 Contrary to the second largest television company in Sweden, privately owned TV4, and written media, they claimed that there was no news value, despite a quite spectacular action where 3 500 women each had knitted a 1.5 metre red scarf that were put together and wrapped around the Riksdag building to remind politicians of the global 1.5 degree target (Eckerman, 2024). SVT claimed that they only report from demonstrations and actions if they are violent.

- The government has been accused of not letting journalists with focus on environment, sustainability and climate take part in ‘open’ meetings with ministers, or not being able to pose questions to or interview the ministers, particularly climate minister Pourmokhtari40 – an accusation she has recently confirmed.41 In response to a feature on the government’s climate policy in Swedish public service radio on 11 February 202442, Pourmokhtari’s press secretary posted on X/Twitter: “Incredibly negative feature about climate policy on Sveriges Radio today where the environmental debater Karlsson got a lot of space”. She manipulatively called Karlsson an ‘environmental debater’ even though he is no longer chair of SANC, but associate professor in environmental science, doing active research on climate leadership. To give a more ‘nuanced’ representation of the Tidö government’s climate policy, the press secretary referred to statistics from the European Commission showing that Sweden is number one in EU regarding renewable transport fuels in 2022. But this was also an act of manipulation, since the statistics shows the ranking before the entry into force of the Tidö government, who in 2023 deliberatively repealed the policy instruments that made Sweden number one.43

- Proposals and actions that risk reducing trust in society and increased mistrust between citizens, for example the Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson’s (M) statement in social media44 in October 2023 that XR is “totalitarian” and “poses a threat to Swedish democratic political processes”, something he was sharply criticized for by independent liberal media45. Later, two members of the Riksdag representing M accused on social media XR and other climate activists of being terrorists.46 Both the Prime Minister and climate minister accuse XR of “pretending to care for the climate and just want to destroy the democratic discussion in an illegal way”.47

- In April 2024, a civil servant at the Swedish Energy Agency got fired because of sharing posts from climate activists on social media and for attending a peaceful action organized by Mother Rebellion. Minister of civil defence Carl-Oskar Bohlin (M) bragged on social media about his contacts with the agency’s director general to get confirmed that case was handled appropriately, raising questions in media and trade unions about ministerial ruling, which is forbidden in Sweden. As a result, MP and V have reported minister Bohlin to the Riksdag’s Constitution Committee for potential ministerial ruling48 and a trade union has reported the Swedish Energy Agency to the Chancellor of Justice, serving as ombudsman in the supervision of authorities and civil servants.

- Proposal and decision to drastically reduce the financing of SWEPA, the national expert agency on environment and climate policy (Riksdagen, 2023c), which has notified 65 employees (10 per cent of the staff) of layoffs as of 2025, 13 of which are working with policy instruments, including on climate policy.

- In late 2023, the government assigned Svenska kraftnät, the operator of the national power grid, to propose new rules and guidance on requests for connection to the power grid. A draft version was presented in December 2023 and a final version in January 2024. Before the final version was presented, the state-owned power company operating the power grid in the actual region decided, with reference to the new rules, not to assign grid connection and power supply to an industrial company producing green steel despite them being first in line and having a mature project. In addition, a state-owned company producing iron pellets and sponge iron claimed it would not sell iron to the new company, only to the state-owned competitor in producing green steel, located in the same region. However, the power company decided to connect the two state-owned companies to the grid. The Swedish Energy Markets Inspectorate decided not to process the appeal made by the private company. Claims have been made by the minister responsible for state-owned companies that green steel production by the state-owned company must proceed, since it would be the only project that would render large GHG emission reductions to meet the Swedish climate target.

5. Analysis and Discussion

5.1. Impacts on Democratic Norms and Principles

5.1.1. Legitimacy and Accountability

5.1.2. Output Legitimacy and Distributive Justice

5.2. Explaining the Democratic Deficits

5.2.1. Neo-Corporatism and Ecological Modernization

5.2.2. Populism and Autocratization

6. Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Disclosure statement

References

- Ackrill, R. & Kay, A. (2011) Multiple streams in EU policy-making: The case of the 2005 sugar reform, Journal of European Public Policy, 18(1), 72-89. [CrossRef]

- Arnold, G. (2021) Does entrepreneurship work? Understanding what policy entrepreneurs do and whether it matters, Policy Studies Journal, 49(4), 968-991. [CrossRef]

- Aviram, N.F., Cohen, N. & Beeri, I. (2019) Wind(ow) of change: A systematic review of policy entrepreneur characteristics and strategies, Policy Studies Journal, 48(3), 612-644. [CrossRef]

- Bäckstrand, K., Zelli, F. & Schleifer, P. (2018) Legitimacy and accountability in polycentric climate governance, In: Jordan, A., Huitema, D., van Asselt, H. & Forster, J. (eds.), Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action? Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 338-356.

- Baard, P., Melin, A. & Magnusdottir, G.L. (2023) Justice in energy transition scenarios: Perspectives from Swedish energy politics, Etikk i Prakis / Nordic Journal of Applied Ethics, early view. [CrossRef]

- Bailey, I., Gouldson, A. & Newell, P. (2011) Ecological modernisation and the governance of carbon: A critical analysis, Antipode, 43(3), 682-703. [CrossRef]

- Baker, S. (2007) Sustainable development as symbolic commitment: Declaratory policy and the seductive appeal of ecological modernisation in the European Union, Environmental Politics, 16(2), 297-317. [CrossRef]

- Barker, R. (1980) Political Legitimacy and the State, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Bauer, T. (2014) Responsible lobbying: A multidimensional model, The Journal of Corporate Citizenship, 53, 61-76. https://www.jstor.org/stable/jcorpciti.53.61.

- Bauer, M.W. & Becker, S. (2014) The unexpected winner of the crisis: The European Commission’s strengthened role in economic governance, Journal of European Integration, 36(3), 213-229. [CrossRef]

- Becker, S. (2024) Supranational entrepreneurship through the administrative backdoor: The Commission, the Green Deal and the CAP 2023–2027, Journal of Common Market Studies, 62, 13522. [CrossRef]

- Becker S., Bauer M.W., Connolly S. & Kassim H. (2016) The Commission: boxed in and constrained, but still an engine of integration, West European Politics, 39(5), 1011-1031.

- Beetham, D. (1985) Max Weber and the Theory of Modern Politics, Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Beetham, D. (1991) The Legitimation of Power, London: Macmillan.

- Berglund, O. & Schmidt, D. (2020) Extinction Rebellion and Climate Change Activism: Breaking the Law to Change the World, London: Palgrave Macmillan. [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, S. (2001) The Compromise of Liberal Environmentalism, New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

- Biermann, F. & Gupta, A. (2011) Accountability and legitimacy in earth system governance: A research framework, Ecological Economics, 70(11), 1856-1864. [CrossRef]

- Bitonti, A. (2017) The role of lobbying in modern democracy: A theoretical framework, In: Bitonti, A. & Harris, P. (eds.), Lobbying in Europe: Public Affairs and the Lobbying Industry in 28 EU Countries, London: Palgrave Macmillan; 17-30.

- Bjereld, U. (2024) SD:s hat påverkar public service framtid, Konkret, 14 May 2024. https://magasinetkonkret.se/sds-hat-paverkar-public-service-framtid/.

- Black, J. (2008) Constructing and contesting legitimacy and accountability in polycentric regulatory regimes, Regulation & Governance, 2(2), 137-164. [CrossRef]

- Boasson, E.L. & Huitema, D. (2017) Climate governance entrepreneurship: Emerging findings and a new research agenda, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(8), 1343-1361. [CrossRef]

- Boese, V.A., Edgell, A.B., Hellmeier, S., Maerz, S.F. & Lindberg, S.I. (2021) How democracies prevail: Democratic resilience as a two-stage process, Democratization, 28(5), 855-907. [CrossRef]

- Boese, V.A., Lundstedt, M., Morrison, K., Sato, Y. & Lindberg, S.I. (2022) State of the world 2021: Autocratization changing its nature? Democratization, 29(6), 983-1013. [CrossRef]

- Böhmelt, T., Böker, M. & Ward, H. (2015) Democratic inclusiveness, climate policy outputs, and climate policy outcomes, Democratization, 23(7), 1272-1291. [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S. (2014) Energy poverty in the European Union: Landscapes of vulnerability, WIREs Energy and Environment, 3(3), 276-289. [CrossRef]

- Bouzarovski, S. (2022) Just transitions: A political ecology critique, Antipode, 54(4), 1003-1020. https://doi.ovrg/10.1111/anti.12823.

- Bouzarovski, S., Thomson, H. & Cornelis, M. (2021) Confronting energy poverty in Europe: A research and policy agenda, Energies, 14(4), 858. [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, S. & Huitema, D. (2018) Policy entrepreneurs and strategies for change, Regional Environmental Change, 18, 1259-1272. [CrossRef]

- Brown, K., Mondon, A. & Winter, A. (2023) The far right, the mainstream and mainstreaming: towards a heuristic framework, Journal of Political Ideologies, 28(2), 162-179. [CrossRef]

- Burns, T.R. & Carson, M. (2002) European Union, neo-corporatist, and pluralist governance arrangements: lobbying and policy-making patterns in a comparative perspective, International Journal of Regulation and Governance, 2(2), 129-175. [CrossRef]

- Buzogány, A. & Scherhaufer, P. (2022) Framing different energy futures? Comparing Fridays for Future and Extinction Rebellion in Germany, Futures, 137, 102904. [CrossRef]

- Capetola, T. (2008) Climate change and social inclusion: Opportunities for justice and empowerment, Just Policy: A Journal of Australian Social Policy, 47, 23-30. https://search.informit.org/doi/abs/10.3316/INFORMIT.022539616245453.

- Caramani, D. (2017) Will vs. reason: The populist and technocratic forms of political representation and their critique to party government, American Political Science Review, 111(01), 54-67. [CrossRef]

- Cassegård, C. & Thörn, H. (2017) Climate justice, equity and movement mobilization, In: Cassegård, C., Soneryd, L., Thörn, H. & Wettergren, Å. (eds.) Climate Action in a Globalizing World, London: Routledge; 33-56.

- Castelli Gattinara, P. & Pirro, A.L.P. (2019) The far right as social movement, European Societies, 21(4), 447-462. [CrossRef]

- Civil Rights Defenders (2023) Ett år med Tidöavtalet: Det är helheten som oroar (One year with the Tidö Agreement: It is the overall pattern that worries), Stockholm: Civil Rights Defenders Sweden. https://crd.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/Civil-Rights-Defenders-granskning-Ett-ar-med-Tido.pdf.

- Cohen, J. (1996) Procedure and substance in deliberative democracy, In: Benhabib, S. (ed.) Democracy and Difference: Contesting the Boundaries of the Political, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 67-94.

- Coleman, E.A., Harring, N. & Jagers, S.C. (2023) Policy attributes shape climate policy support, Policy Studies Journal, 51(2), 419-437. [CrossRef]

- Copeland, P. & James, S. (2014) Policy windows, ambiguity and Commission entrepreneurship: Explaining the relaunch of the European Union’s economic reform agenda, Journal of European Public Policy, 21(1), 1-19. [CrossRef]

- Crespy, A., & Munta, M. (2023) Lost in transition? Social justice and the politics of the EU green transition, Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 29(2), 235-251. [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, K., Hix, S., Dennison, S. & Laermont, I. (2024) A Sharp Right Turn: A Forecast for the 2024 European Parliament Elections, Berlin: European Council on Foreign Relations. https://ecfr.eu/publication/a-sharp-right-turn-a-forecast-for-the-2024-european-parliament-elections/.

- Dalton, R.J., Recchia, S. & Rohrschneider, R. (2003) The environmental movement and the modes of political action, Comparative Political Studies, 36(7), 743-771. [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S. (2012) The insuperable imperative: A critique of the ecologically modernizing state¸ Capitalism Nature Socialism, 23(2), 31-50. [CrossRef]

- De Moor, J., De Vydt, M., Uba, K. & Wahlström, M. (2020) New kids on the block: taking stock of the recent cycle of climate activism, Social Movement Studies, 20(5), 619-625. [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. (2001) Legitimacy and economy in deliberative democracy, Political Theory, 29(5), 651-669. [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. (2014) The deliberative democrat’s idea of justice, European Journal of Political Theory, 12(4), 329-346. [CrossRef]

- Dryzek, J.S. & Stevenson, H. (2011) Democracy and global earth system governance, Ecological Economics, 70(11), 1865-1874. [CrossRef]

- Dupont, C., Moore, B., Boasson, E. L., Gravey, V., Jordan, A., Kivimaa, P., Kulovesi, K., Kuzemko, C., Oberthür, S., Panchuk, D., Rosamond, J., Torney, D., Tosun, J., & von Homeyer, I. (2023). Three decades of EU climate policy: Racing toward climate neutrality? WIREs Climate Change, 15(1), e863. [CrossRef]

- Eckersley, R. (2004) The Green State: Rethinking Democracy and Sovereignty, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Eckersley, R. (2019) Ecological democracy and the rise and decline of liberal democracy: looking back, looking forward, Environmental Politics, 29(2), 214-234. [CrossRef]

- Eckerman, I. (2024) SVT bojkottar kvinnors fredliga demonstrationer, Konkret, 2 May 2024. https://magasinetkonkret.se/svt-bojkottar-kvinnors-fredliga-demonstrationer/.

- Etzioni, A. (2010) Is transparency the best disinfectant? Journal of Political Philosophy, 18(4), 389-404. [CrossRef]

- European Commission (2019) The European Green Deal, COM(2019) 640 final, Brussels: European Commission. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/european-green-deal-communication_en.pdf.

- European Commission (2021) Fit for 55: Delivering on the proposals, Brussels: European Commission. https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/delivering-european-green-deal/fit-55-delivering-proposals_en.

- EU (2021) Regulation (EU) 2021/1119 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 June 2021 establishing the framework for achieving climate neutrality and amending Regulations (EC) No 401/2009 and (EU) 2018/1999 (‘European Climate Law’), Official Journal of the European Union, OJ L 243, 9.7.2021, pp. 1–17. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021R1119 (Last accessed 13 May 2024).

- Evans, G. & Phelan, L. (2016) Transition to a post-carbon society: Linking environmental justice and just transition discourses, Energy Policy, 99, 329-339. [CrossRef]

- Ewald, J., Sterner, T. & Sterner, E. (2022) Understanding the resistance to carbon taxes: Drivers and barriers among the general public and fuel-tax protesters, Resource and Energy Economics, 70, 101331. [CrossRef]

- Filgueiras, F. (2016) Transparency and accountability: Principle and rules for the construction of publicity, Journal of Public Affairs, 16, 192-202. [CrossRef]

- Finkel, S.E. & Lim, J. (2021) The supply and demand model of civic education: evidence from a field experiment in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Democratization, 28(5), 970-991. [CrossRef]

- Fiorino, D.J. (1990) Citizen participation and environmental risk: A survey of institutional mechanisms, Science, Technology, and Human Values, 15(2), 226-243. https://www.jstor.org/stable/689860.

- Filipović, S., Lior, N. & Radovanović, M. (2022) The green deal – just transition and sustainable development goals Nexus, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 168, 112759. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, A., Joosse, S., Strandell, J., Söderberg, N., Johansson, K. & Boonstra, W.J. (2023) How justice shapes transition governance – a discourse analysis of Swedish policy debates, Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, preprint. [CrossRef]

- Forst, M. (2024) State repression of environmental protest and civil disobedience: a major threat to human rights and democracy, Position Paper by UN Special Rapporteur on Environmental Defenders under the Aarhus Convention, February 2024, Geneva: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe. https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-02/UNSR_EnvDefenders_Aarhus_Position_Paper_Civil_Disobedience_EN.pdf.

- Green, J.F. (2017) Policy entrepreneurship in climate governance: Toward a comparative approach, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(8), 1471-1482. [CrossRef]

- Greenpeace Sweden (2023) Rött ljus: En granskning av Tidöpartiernas klimat- och miljöpolitik under deras första år vid makten, Stockholm: Greenpeace Sweden. https://www.greenpeace.org/static/planet4-sweden-stateless/2023/10/197bfe6d-regeringslogg.pdf.

- Gullers (2021) Allmänheten om klimatet 2021, Stockholm: Gullers grupp. https://www.naturvardsverket.se/4ac4dd/contentassets/6ffad3e6018c47cea06e6402f0eea066/rapport-allmanheten-klimatet-2021.pdf.

- Gutmann, A. & Thompson, D. (1990) Moral conflict and political consensus, Ethics, 101, 64-88. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2381892.

- Gutmann, A. & Thompson, D. (1996) Democracy and Disagreement, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Haas, T., Syrovatka, F. & Jürgens, I. (2022) The European Green Deal and the limits of ecological modernisation, Culture, Practice & Europeanization, 7(2), 247-261. [CrossRef]

- Habermas, J. (1979) Communication and the Evolution of Society, Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Habermas, J. (1996) Between Facts and Norms. Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy, Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Håkansson, C. (2023) The New Role of the European Commission in the EU’s Security and Defence Architecture: Entrepreneurship, Crisis and Integration, Doctoral dissertation, Malmö, SE: Malmö University. http://mau.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1807190/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Hassler, J., Krusell, P. & Nycander, J (2016) Climate policy, Economic Policy, 31(87), 503-558. [CrossRef]

- Held, D. (2006) Models of Democracy, Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Holman, C. & Luneburg, W. (2012) Lobbying and transparency: A comparative analysis of regulatory reform, Interest Groups & Advocacy, 1, 75-104. [CrossRef]

- Hunold, C. (2002) Corporatism, pluralism, and democracy: Toward a deliberative theory of bureaucratic accountability, Governance, 14(2), 151-167. [CrossRef]

- IPCC (2023a) Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report, Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. [CrossRef]

- IPCC (2023b) Climate Change 2023: Summary for Policymakers, Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- International Energy Agency (2019) Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency: From “Hidden Fuel” to “First Fuel”, Paris: International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/reports/multiple-benefits-of-energy-efficiency.

- International Energy Agency (2021) How Energy Efficiency Will Power Net Zero Climate Goals, Paris: International Energy Agency. https://www.iea.org/commentaries/how-energy-efficiency-will-power-net-zero-climate-goals.

- Jänicke, M. (2020) Ecological modernisation – a paradise of feasibility but no general solution, In: Metz, L., Okamura, L. & Weidner, H. (eds.), The Ecological Modernization Capacity of Japan and Germany: Energy Policy and Climate Protection, Wiesbaden: Springer Nature; 13-23. [CrossRef]

- Jarrodi, H., Byrne, J. & Bureau, S. (2020) A political ideology lens on social entrepreneurship motivations, In: Farias, C., Fernandez, P., Hjorth, D. & Holt, R. (eds.) Organizational Entrepreneurship, Politics and the Political, London: Routledge; 29-50.

- Jordan, A. & Huitema, D. (2014) Policy innovation in a changing climate: Sources, patterns and effects, Global Environmental Change, 29, 387-394. [CrossRef]

- Jordan, A.J., Huitema, D., Hildén, M., van Asselt, H., Rayner, T.J., Schoenefeld, J.J., Tosun, J., Forster, J. & Boasson, E.L. (2015) Emergence of polycentric climate governance and its future prospects, Nature Climate Change, 5, 977-982. [CrossRef]

- Jylhä, K.M., Strimling, P. & Rydgren, J. (2020) Climate change denial among radical right-wing supporters, Sustainability, 12(23), 10226. [CrossRef]

- Kamali, M. (2024a) Visitationszoner skapar ett övervakningssamhälle, Konkret, 1 March 2024. https://magasinetkonkret.se/visitationszoner-skapar-bara-ett-overvakningssamhalle/.

- Kamali, M. (2024b) Socialdemokraternas vandring mot nyliberalism, Konkret, 26 April 2024. https://magasinetkonkret.se/socialdemokraternas-vandring-mot-nyliberalism/.

- King, L.A. (2003) Deliberation, legitimacy, and multilateral democracy, Governance, 16(1), 23-50. [CrossRef]

- Kronsell, A., Khan, J. & Hildingsson, R. (2019) Actor relations in climate policymaking: Governing decarbonisation in a corporatist green state, Environmental Policy & Governance, 29(6), 399-408. [CrossRef]

- Krüger, T. (2022) The German energy transition and the eroding consensus on ecological modernization: A radical democratic perspective on conflicts over competing justice claims and energy visions, Futures, 136, 102899. [CrossRef]

- Kuyper, J.W., Linnér, B.O. & Schroeder, H. (2018) Non-state actors in hybrid global climate governance: justice, legitimacy, and effectiveness in a post-Paris era, WIREs Climate Change, 9, e497. [CrossRef]

- Laebens, M.G. & Lührmann, A. (2021) What halts democratic erosion? The changing role of accountability, Democratization, 28(5), 908-928. [CrossRef]

- Lagerkvist, S. (2024) Så snabbt kan vår demokrati avskaffas, Syre, 23 March 2024. https://tidningensyre.se/2024/23-mars-2024/sa-snabbt-kan-var-demokrati-avskaffas/.

- Lai, Y.Y., Christley, E., Kulanovic, A., Teng, C.C., Björklund, A., Nordensvärd, J., Karakaya, E. & Urban, F. (2022) Analysing the opportunities and challenges for mitigating the climate impact of aviation: A narrative review, Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 156, 111972. [CrossRef]

- Lidskog, R. & Elander, I. (2012) Ecological modernization in practice? The case of sustainable development in Sweden, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 14(4), 411-427. [CrossRef]

- Lijphart, A. (1977) Democracy in Plural Societies: A Comparative Exploration, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lijphart, A. (1999) Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in Thirty-Six Countries, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Lipset, S.M. (1955) The radical right: A problem for American democracy, British Journal of Sociology, 6(2), 176-209. [CrossRef]

- Lipset, S.M. (1959) Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy, American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69-105. [CrossRef]

- Lock, I. & Seele, P. (2016) Deliberative lobbying? Toward a noncontradiction of corporate political activities and corporate social responsibility? Journal of Management Inquiry, 25(4), . [CrossRef]

- Lührmann, A. (2021) Disrupting the autocratization sequence: towards democratic resilience, Democratization, 28(5), 1017-1039. [CrossRef]

- Lührmann, A., Gastaldi, L., Hirndorf, D. & Lindberg, S.I. (2020) Defending Democracy Against Illiberal Challengers: A Resource Guide. Gothenburg: V-Democracy Institute/University of Gothenburg. https://www.v-dem.net/documents/21/resource_guide.pdf.

- Lundqvist, L.J. (2004) ‘Greening the people’s home’: The formative power of sustainable development discourse in Swedish housing, Geography, Urban Studies & Planning, 41(7), 1283-1301. [CrossRef]

- Mackenzie, C. (2010) Policy entrepreneurship in Australia: A conceptual review of application, Australian Journal of Political Science, 39(2), 367-386. [CrossRef]

- Maestre-Andrés, S., Drews, S. & van den Bergh, J. (2019) Perceived fairness and public acceptability of carbon pricing: a review of the literature, Climate Policy, 19(9), 1186-1204. [CrossRef]

- Mair, P. (2013) Ruling the Void: The Hollowing of Western Democracy, London: Verso.

- Maltby, T. (2013) European Union energy policy integration: A case of European Commission policy entrepreneurship and increasing supranationalism, Energy Policy, 55, 435-444. [CrossRef]

- Matti, S., Petersson, C. & Söderberg, C. (2021) The Swedish climate policy framework as a means for climate policy integration: an assessment, Climate Policy, 21(9), 1146-1158. [CrossRef]

- Matti, S., Nässén, J. & Larsson, J. (2022) Are fee-and-dividend schemes the savior of environmental taxation? Analyses of how different revenue use alternatives affect public support for Sweden’s air passenger tax, Environmental Science & Policy, 132, 181-189. [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D. & Heffron, R. (2018) Just transition: Integrating climate, energy and environmental justice, Energy Policy, 119, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Meléndez, C. & Rovira Kaltwasser, C. (2021) Negative partisanship towards the populist radical right and democratic resilience in Europe, Democratization, 28(5), 949-969. [CrossRef]

- Merkel, W. & Lührmann, A. (2021) Resilience of democracies: responses to illiberal and authoritarian challenges, Democratization, 28(5), 869-884. [CrossRef]

- Minto, R., & Mergaert, L. (2018) Gender mainstreaming and evaluation in the EU: Comparative perspectives from feminist institutionalism, International Feminist Journal of Politics, 20(2), 204-220. [CrossRef]

- Mintrom, M. & Luetjens, J. (2017) Policy entrepreneurs and problem framing: The case of climate change, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 35(8), 1362-1377. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R.B. (2011) Transparency for governance. The mechanisms and effectiveness of disclosure-based and education-based transparency policies, Ecological Economics, 70(11), 1882-1890. [CrossRef]

- Mollona, E. & Faldetta, G. (2022) Ethics in corporate political action: can lobbying be just? Journal of Management and Governance, 26, 1245-1276. [CrossRef]

- Moravcsik, A. (1999) A new statecraft? Supranational entrepreneurs and international cooperation, International Organization, 53(2), 267-306. [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C. (2004) The populist Zeitgeist, Government and Opposition, 39(4), 541-563. [CrossRef]

- Mudde, C. (2021) Populism in Europe: An illiberal democratic response to undemocratic liberalism, Government and Opposition, 56(4), 577-597. [CrossRef]

- Müller, T. (2023) Policy Entrepreneurship in Global Institutions: How, Why, and With What Consequences, Doctoral dissertation, Munich: Technical University of Munich. https://mediatum.ub.tum.de/doc/1713197/document.pdf.

- Muñoz Cabré, M. & Vega Araújo, J. (2022) Considerations for a just and equitable energy transition. Background paper for the Stockholm+50 conference, Stockholm: Stockholm Environment Institute. https://www.sei.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/energy-transitions-stockholm50backgroundpaper.pdf.

- Newell, P. (2008) Civil society, corporate accountability and the politics of climate change, Global Environmental Politics, 8(3), 122-153. [CrossRef]

- Newell, P., Srivastava, S., Naess, L.O., Torres Contreras, G.A. & Price, R. (2021) Toward transformative climate justice: An emerging research agenda, WIREs Climate Change, 12(6), e733. [CrossRef]

- Neyer, J. (2010) Justice, not democracy: Legitimacy in the European Union, Journal of Common Market Studies, 48(4), 903-921. [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, K., Wolrath Söderberg, M., Luth Richter, J., Gross, S., Pihl, E., Kasimir, Å., Carton, W., Hahn, T. & Skelton, A. (2022) Analys av sju riksdagspartiers klimatpolitik utförd av klimat- och omställningsforskare: Sveriges klimatpolitik inför riksdagsvalet 2022, Stockholm: Researchers’ Desk, https://researchersdesk.se/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Researchers-Desk-klimatpolitik-2022.pdf.

- Nordhaus, W. (2019) Climate change: The ultimate challenge for economics, American Economic Review, 109(6), 1991-2014.

- Novus (2023) Svenskarnas syn på klimatfrågan sommaren 2023, Stockholm: Novus. https://novus.se/egnaundersokningar-arkiv/svenskarnas-syn-pa-klimatfragan-sommaren-2023/.

- O’Donnell, G. (2007) The perpetual crises of democracy, Journal of Democracy, 18(1), 5-9. https://heinonline.org/HOL/LandingPage?handle=hein.journals/jnlodmcy18&div=4&id=&page=.

- Olsson, D., Öjehag-Pettersson, A. & Granberg, M. (2021) Building a sustainable society: Construction, public procurement policy and ‘best practice’ in the European Union, Sustainability, 13(13), 7142. [CrossRef]

- Olsson Rost, A. & Collinson, M. (2022) Developing the Labour party’s comprehensive secondary education policy, 1950-1965: Party activists as public intellectuals and policy entrepreneurs, British Journal of Educational Studies, 70(5), 609-625. [CrossRef]

- Osička, J., Szulecki, K. & Jenkins, K.E.H. (2023) Energy justice and energy democracy: Separated twins, rival concepts or just buzzwords? Energy Research & Social Science, 104, 103266. [CrossRef]

- Petridou, E. & Mintrom, M. (2021) A research agenda for the study of policy entrepreneurs, Policy Studies Journal, 49(4), 943-967. [CrossRef]

- Petrova, S. & Simcock, N. (2021) Gender and energy: domestic inequities reconsidered, Social & Cultural Geography, 22(6), 849-867. [CrossRef]

- Pickering, J, Bäckstrand, K. & Schlosberg, D. (2020) Between environmental and ecological democracy: theory and practice at the democracy-environment nexus, Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 22(1), 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Pirro, A.L.P. (2023) Far right: The significance of an umbrella concept, Nations and Nationalism, 29(1), 101-112. [CrossRef]

- Rabe, B. (2004) Statehouse and Greenhouse: The Stealth Politics of American Climate Change Policy, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Riksdagen (2023a) Finansutskottets betänkande 2023/24:FiU1: Statens budget 2024 – Rambeslutet (Committee report on the budgetary bill – Frame decision), Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/16D4C2B7-DC55-4044-8D69-D12A5AC3DA96.

- Riksdagen (2023b) Näringsutskottets betänkande 2023/24:NU3: Utgiftsområde 21 Energi (Committee report on the budgetary bill – Energy), Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/betankande/utgiftsomrade-21-energi_hb01nu3/html/.

- Riksdagen (2023c) Miljö- och jordbruksutskottets betänkande 2023/24:MJU1: Utgiftsområde 20 Klimat, miljö och natur (Committee report on the budgetary bill – Climate and environment), Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/betankande/utgiftsomrade-20-klimat-miljo-och-natur_hb01mju1/html/.

- Riksdagen (2023d) Konstitutionsutskottets betänkande 2022/23:KU20: Granskningsbetänkande (Constitutional committee scrutiny report on the government), Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://data.riksdagen.se/fil/A7ADEA2E-FDB8-4136-9484-809FE4C4BD2B.

- Riksdagen (2023e) Interpellationsdebatt 17 februari 2023: Nationella åtgärder med anledning av höjda avgifter i kollektivtrafiken, Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/webb-tv/video/interpellationsdebatt/nationella-atgarder-med-anledning-av-hojda_HA10187/?pos=631&autoplay=true.

- Riksdagen (2024a) Riksdagens snabbprotokoll 2023/24:60, onsdagen den 24 januari 2024, Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://data.riksdagen.se/dokument/HB0960.

- Riksdagen (2024b) Interpellation 2023/24:539 av Elin Söderberg (MP), En graf i klimathandlingsplanen. Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/interpellation/en-graf-i-klimathandlingsplanen_hb10539/.

- Riksdagen (2024c) Skriftlig fråga 2023/24:502 av Rickard Nordin (C): Regeringens ökning av de fossila subventionerna, Stockholm: Swedish Riksdag. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-och-lagar/dokument/skriftlig-fraga/regeringens-okning-av-de-fossila-subventionerna_hb11502/.

- Rothstein, B. (2009) Creating political legitimacy: Electoral democracy versus quality of government, American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 311-330. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein, B. (2023) The shadow of the Swedish right, Journal of Democracy, 34(1), 36-49. [CrossRef]

- Rydgren, J. & van der Meiden, S. (2016) Sweden, Now a Country Like All the Others? The Radical Right and the End of Swedish Exceptionalism, Sociology Working Paper Series 25, Stockholm: Stockholm University. https://su.figshare.com/ndownloader/files/26487815.

- Saetren, H. (2016) From controversial policy idea to successful program implementation: the role of the policy entrepreneur, manipulation strategy, program design, institutions and open policy windows in relocating Norwegian central agencies, Policy Sciences, 49, 71-88. [CrossRef]

- Sato, Y., Lundstedt, M., Morrison, K., Boese, V. & Lindberg, S. (2022) Institutional Order in Episodes of Autocratization, V-Dem Working Paper 133, Gothenburg, SE: V-Dem Institute. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4239798.

- Scharpf, F.W. (1999) Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? New York: Oxford University Press.

- Schlembach, R. (2011) The transnationality of European nationalist movements, Revue Belge de Philosophie d’Histoire, 89, 1331-1350. https://www.persee.fr/doc/rbph_0035-0818_2011_num_89_3_8359.

- Schlosberg, D. (1999) Environmental Justice and the New Pluralism: The Challenge of Difference for Environmentalism, Cary, NC: Oxford University Press.

- Schlosberg, D. & Collins, L.B. (2014) From environmental to climate justice: climate change and the discourse of environmental justice, WIREs Climate Change, 5(3), 359-374. [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.A. (2006) Democracy in Europe: The EU and National Polities, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Schmidt, V.A. (2013) Democracy and legitimacy in the European Union revisited: Input, output and ‘throughput’, Politics, Public Administration & International Relations, 61(1), 2-22. [CrossRef]

- Schneider, M. & Teske, P. (1992) Towards a theory of the political entrepreneur: Evidence from local government, American Political Science Review, 86(3), 737-747. [CrossRef]

- Scott, W.R. (2001) Institutions and Organizations, 2nd ed., Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- SCPC (2024) Klimatpolitiska rådets rapport 2024 (Annual report 2024 of the Climate Policy Council), Stockholm: Swedish Climate Policy Council. https://www.klimatpolitiskaradet.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/klimatpolitiskaradetsrapport2024.pdf.

- SFPC (2024) Svensk finanspolitik: Finanspolitiska rådets rapport 2024 (Annual report 2024 of the Finance Policy Council), Stockholm: Swedish Finance Policy Council. https://www.fpr.se/download/18.2d63770418f379d56435cd1/1714722716776/Svensk%20finanspolitik%202024.pdf.

- Shepard, P.M. & Corbin-Mark, C. (2009) Climate justice, Environmental Justice, 2(4), 163-166.

- Silander, D. (2024) Problems in Paradise? Changes and Challenges to Swedish Democracy, Leeds, UK: Emerald.

- Singleton, B.E., Rask, N., Magnusdottir, G.L. & Kronsell, A. (2022) Intersectionality and climate policy-making: The inclusion of social difference by three Swedish government agencies, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 40(1), 180-200. [CrossRef]

- Somer, M., McCoy, J.L. & Luke, R.E. (2021) Pernicious polarization, autocratization and opposition strategies, Democratization, 28(5), 929-948. [CrossRef]

- Spaargaren, G. & Mol, A.P.J. (1992) Sociology, environment, and modernity: Ecological modernization as a theory of social change, Society & Natural Resources, 5(4), 323-344. [CrossRef]

- Staff, H. (2018) Partisan effects and policy entrepreneurs. New Labour’s impact on British law and order policy, Policy Studies, 39(1), 19-36. [CrossRef]

- Statistics Sweden (2024) National accounts: GDP from the consumption side (ENS2010), supply balance, seasonally adjusted current prices, MSEK by consumption and quarter 1980Q1–2023Q3, Stockholm: Statistics Sweden. https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__NR__NR0103__NR0103B/NR0103ENS2010T10SKv/.

- Stevenson, H. & Dryzek, J. (2014) Democratizing Global Climate Governance, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stewart, B. (2020) The rise of far-right civilizationism, Critical Sociology, 46(7-8), 1207-1220. [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. (1995) Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches, Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 571-610. [CrossRef]

- Swedish Government (2023a) Regeringens skrivelse 2023/24:59: Regeringens klimathandlingsplan – hela vägen till nettonoll (Government’s letter on a Climate Action Plan), Stockholm: Swedish government. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/990c26a040184c46acc66f89af34437f/232405900webb.pdf.

- Swedish Government (2023b) Regeringens proposition 2023/24:1: Budgetpropositionen för 2024 (Government’s budgetary bill for 2024), Stockholm: Swedish government. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/e1afccd2ec7e42f6af3b651091df139c/budgetpropositionen-for-2024-hela-dokumentet-prop.2023241.pdf.

- Swedish government (2024a) Energipolitikens långsiktiga inriktning, Prop. 2023/24:105 (Government’s long-term energy policy bill), Stockholm: Swedish government.

- Swedish government (2024b) Ansvar och oberoende – public service i oroliga tider, SOU 2024:34, Stockholm: Swedish government, Ministry of Culture. https://www.regeringen.se/contentassets/e5718396c8b74e59b18bc52420332a14/sou-2024_34_pdf-a_webb.pdf.

- Swedish Legislative Council (2022) Sekretess vid Försäkringskassans handläggning av ärenden om elstöd och slopad kontrolluppgiftsskyldighet (Legislative Council report on secrecy on electricity support), Stockholm: Swedish Legislative Council. https://www.lagradet.se/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Sekretess-vid-Forsakringskassans-handlaggning-av-arenden-om-elstod-och-slopad-kontrolluppgiftsskyldighet.pdf.

- SWEPA (2023) Press release: Swedish GHG emissions reduced with 5 per cent in 2022, Stockholm: Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.naturvardsverket.se/om-oss/aktuellt/nyheter-och-pressmeddelanden/2023/juni/sveriges-klimatutslapp-minskade-med-fem-procent-under-2022/.

- SWEPA (2024) Naturvårdsverkets underlag till regeringens klimatredovisning 2024 (Input from the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency to the government’s climate report 2024), Stockholm: Swedish Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.naturvardsverket.se/49732a/globalassets/amnen/klimat/klimatredovisning/naturvardsverkets-underlag-till-regeringens-klimatredovisning-2024.pdf.

- Swyngedouw, E. (2011) Depoliticized environments: The end of nature, climate change and the post-political condition, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement, 69, 253-274. [CrossRef]

- United Nations Association of Sweden (2023) Varningslampor blinkar för demokratin i Sverige (Flashlights are warning about Swedish democracy), Stockholm: United Nations Association of Sweden. https://fn.se/aktuellt/varldshorisont/varningslampor-blinkar-for-demokratin-i-sverige/.

- Thomson, H. & Bouzarovski, S. (2019) Addressing Energy Poverty in the European Union: State of Play and Action, Brussels: European Commission, EU Energy Poverty Observatory. https://energy-poverty.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2022-04/paneureport2018_updated2019.pdf.

- Thörn, H. & Svenberg, S. (2016) ‘We feel the responsibility that you shirk’: movement institutionalization, the politics of responsibility and the case of the Swedish environmental movement, Social Movement Studies, 15(6), 593-609. [CrossRef]

- Tidö Parties (2022) Tidöavtalet: En överenskommelse för Sverige (The Tidö Agreements: An agreement for Sweden), 14 October 2022, Tidö, SE: Moderaterna, Kristdemokraterna, Liberalerna, Sverigedemokraterna. https://www.liberalerna.se/wp-content/uploads/tidoavtalet-overenskommelse-for-sverige-slutlig.pdf.

- Tobin, P.A. (2015) Blue and yellow makes green? Ecological modernisation in Swedish climate policy, In: Bäckstrand, K. & Kronsell, A., (eds.) Rethinking the Green State: Environmental Governance Towards Climate and Sustainability Transitions, Abingdon, UK: Earthscan; 141-155.

- Urban, F., Nordensvärd, J. & Kulanovic, A. (2024) Sustainable energy transitions in aviation, In: Urban, F. & Nordensvärd, J. (eds.), Handbook on Climate Change and Technology, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 196-204.

- V-Dem Institute (2024) Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot: Democracy Report 2024, Gothenburg, SE: University of Gothenburg. https://v-dem.net/documents/43/v-dem_dr2024_lowres.pdf.

- Vahter, M. & Jakobson, M.L. (2023) The moral rhetoric of populist radical right: The case of the Sweden Democrats, Journal of Political Ideologies, preprint. [CrossRef]

- van Bommel, N. & Höffken, J. (2023) The urgency of climate action and the aim for justice in energy transitions – dynamics and complexity, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 48, 100763. [CrossRef]

- van den Dool, A. & Schlaufer, C. (2024) Policy process theories in autocracies: Key observations, explanatory power, and research priorities, Review of Policy Research, 41, early view. [CrossRef]

- van den Hove, S. (2000) Participatory approaches to environmental policy-making: the European Commission climate policy process as a case study, Ecological Economics, 33(3), 457-472. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2023a) First and last and always: Politics of the ‘energy efficiency first’ principle in EU energy and climate policy, Energy Research & Social Science, 101, 103126. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F (2023b) Tales of creation: Advocacy coalitions, beliefs and paths to policy change on the ‘energy efficiency first’ principle in EU, Energy Efficiency, 16, 10168. [CrossRef]

- von Malmborg, F. (2024a) Regeringens klimatpolitik är populistisk, Konkret, 12 March 2024. https://magasinetkonkret.se/regeringens-klimatpolitik-ar-populistisk/.

- von Malmborg, F. (2024b) Tidöpolitiken hotar både klimatet och demokratin, Syre, 6 April 2024. https://tidningensyre.se/2024/06-april-2024/tidopolitiken-hotar-bade-klimatet-och-demokratin/.

- von Malmborg, F., Rohdin, P. & Wihlborg, E. (2023) Climate declarations for buildings as a new policy instrument in Sweden: A multiple streams perspective, Building Research & Information, 51, 2222320. [CrossRef]

- von Platten, J., Mangold, M. & Mjörnell, K. (2020) A matter of metrics? How analysing per capita energy use changes the face of energy efficient housing in Sweden and reveals injustices in the energy transition, Energy Research & Social Science, 70, 101807. [CrossRef]

- von Platten, J., Mangold, M., Johansson, T. & Mjörnell, K. (2022) Energy efficiency at what cost? Unjust burden-sharing of rent increases in extensive energy retrofitting projects in Sweden, Energy Research & Social Science, 92, 102791. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X. & Lo, K. (2021) Just transition: A conceptual review, Energy Research & Social Science, 82, 102291. [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. (1994) Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 2nd ed., London: Sage.

- Zahariadis, N. (2003) Ambiguity and Choice in Public Policy: Manipulation in Democratic Societies, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- Zeilinger, B. (2021) The European Commission as a policy entrepreneur under the European semester, Politics and Governance, 9(3), 63-73. [CrossRef]

| Types of sources | Interviews and documents |

|---|---|

| Interviews | IP1. Policy officer, Government Offices of Sweden, Ministry of Climate and Enterprise (December 2023) IP2. Policy officer, Government Offices of Sweden, Ministry of Rural Affairs and Infrastructure (December 2023) |

| Policy documents |

|

| Government authority documents |

|

| Newspapers and magazines |

|

| Blogs |

|

| National television |

|

| National radio |

|

| Actor | Attention- and support seeking strategies | Linking strategies | Relational management strategies | Arena strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sweden Democrats 2006–2023 |

Problem framing, idea generation, strategic use of information (manipulation and strategic manoeuvring), rhetorical persuasion, protests, media attention | Coalition building with M, KD and L, linking climate policy to economic welfare of households | Networking by using social acuity at local and regional level | Timing, venue shopping, focus on local and regional communities, courts |

|

Swedish government 2022–2023 |

Problem framing, idea generation, strategic use of information (manipulation and strategic manoeuvring), rhetorical persuasion, avoiding media attention | Focus on energy policy and EU policy instruments, coalition building with SD and industry, linking climate policy to business competitiveness | Networking with industry, avoiding critical voices from academia, social movements and media | Timing, venue shopping, choosing its own meetings, avoiding critical voices from academia, social movements and media |

| Legitimacy | Accountability | |

|---|---|---|

| Transparency |

Input legitimacy Limited disclosure by the Swedish government and the Sweden Democrats on considerations for the Climate Action Plan. Reduced time for inquiries, with limited possibilities to analyse consequences, and for stakeholders to analyse and respond to public consultations. Violation to the Swedish constitution. No disclosure by the prosecutors, judiciaries, the government or the Sweden Democrats on suggestions for stricter charges and repression of climate activists. Active choice by the minister for climate and environment not to talk to environmental press. Abolishment of financial support to independent media and civil society organizations. Restricted possibilities to scrutinize the government’s climate policy and facilitate education and preparation on policy issues. Manipulation of data concerning potential GHG emission reductions of policies in the CAP. |

|

| Openness and impartiality |

Throughput legitimacy Government consultations with targeted stakeholders only. Discrimination of climate scientists, environmental media and environmental movements. Climate scientists and the environmental and climate justice movements actively excluded by the Swedish government from consultations on the Climate Action Plan. Prime Minister and minister for climate and environment smearing and delegitimizing the climate justice movement as being ‘totalitarian’ and a ‘threat to Swedish democratic political processes’. Members of M in the Riksdag accusing climate activists of being ‘terrorists’. The government and the Sweden Democrats called for and welcomed that climate activists temporarily blocking the traffic are charged for sabotage and sentenced to prison. Active choice by the minister for climate and environment not to talk to environmental journalists restricts possibilities to scrutinise the government’s climate policy. Abolishment of financial support to civil society organizations restricts possibilities to facilitate education and preparation on policy issues. An employee at the Swedish Energy Agency was fired because of being a peaceful climate activist and sharing climate activist posts on social media. |

|

| Justice |

Throughput legitimacy: procedural justice Structural entrepreneurship, aimed at enhancing power of the Sweden Democrats and Swedish government by altering the distribution of formal authority and factual and scientific information. Structural entrepreneurship, aimed at silencing media and critics of the Swedish government’s climate policy by altering the distribution of formal authority and factual and scientific information. |

Government consultations with targeted stakeholders only. Structural entrepreneurship, aimed at silencing media and critics of the Swedish government’s climate policy by altering the distribution of formal authority and factual and scientific information. Prime Minister and minister for climate and environment smearing and delegitimizing the climate justice movement as being ‘totalitarian’ and a ‘threat to Swedish democratic political processes’. The government and the Sweden Democrats welcomed that climate activists temporarily blocking the traffic are charged for sabotage and sentenced to prison. |

|

Output legitimacy: distributional justice Redefinition of the concepts of legitimacy and climate justice to serve the purpose of the Tidö parties and make them look democratic. Swedish government and the Sweden Democrats favour citizens using private cars before public transport. Disregards energy poverty, humans in other countries, future generations, non-human beings. Lack of policies which would make industry invest in the green transition, despite the claim by the Prime Minister that industry would gain competitiveness from first mover advantage. |

||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).