Sustainable finance has achieved remarkable growth over the past decade. Assets under management with a sustainability label are expected to represent more than one-third of total assets under management globally by 2025 (Bloomberg, 2022). This growth has been led by rising social demands related to sustainability, regulations, and an evolution of the concept of fiduciary duty for asset managers (Redondo Alamillos & Mariz, 2022). However, the growth of sustainable finance has come with concerns around greenwashing, defined as an intentional or negligent “misrepresentation of the sustainability characteristics of a financial product and/or of the sustainable commitments and/or achievements of an issuer” (ICMA, 2023b). Sustainable finance faces the challenge of reaching scale while maintaining integrity. Scale is needed, since reaching the UN SDGs will require $3 to $5 trillion annually by 2030 (United Nations Global Compact, n.d.). Integrity hinges on public and private sector collaboration to provide evidence of material impact and will require pricing mechanisms for sustainability to tackle imperfect markets (Glisovic et al., 2012).

In the context of rising public debt levels, nations must explore alternative capital sources and innovative financing mechanisms to bridge the investment gap in climate finance. This paper focuses on sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs), assessing their effectiveness in the realm of sustainable financing. SLBs are “any type of bond instrument for which the financial and/or structural characteristics can vary depending on whether the issuer achieves predefined Sustainability/ ESG objectives” (ICMA, 2021). SLBs differ from use-of-proceeds bonds such as green bonds, which have funds earmarked for environmentally beneficial projects. SLBs are an innovative financial product that translates a sustainability benefit into an explicit and quantifiable financial cost or benefit for the issuer. Following an initial strong success, SLBs have been met with skepticism. The paper delves into SLB characteristics, their advantages and limitations. Furthermore, the paper proposes potential design improvements to enhance SLBs’ effectiveness and improve investor confidence. Through those enhancements, SLBs can illustrate how material ESG topics impact the financial sustainability of companies and potentially their credit ratings.

The paper draws on a mixed methods approach, including a thorough literature review encompassing academic sources, practitioner sources and market data. The paper presents the most up-to-date considerations on SLBs through semi-structured interviews with 14 sustainable finance experts gathered via an online multiple-choice survey. Eight experts were based in North America, six in Latin America and one in Europe. Two detailed interviews of experts were also conducted.

In the first section, the paper analyses the promise of SLBs and explores why linking a sustainability outcome with a financial cost for the issuer is a very significant mechanism, albeit not new. Second, the paper explores the limitations and criticisms applicable to SLBs. In a third section, based on insights gathered from two detailed expert interviews and 14 semi-structured interviews, the paper proposes measures for enhancing SLB design and investor trust.

1. Financial Innovation with a Purpose: Sustainability-Linked Bonds

Finance can serve sustainability in several ways: through funding of businesses that have a positive environmental and social contribution, such as renewable energy or inclusive financial platforms enabled by FinTech (de Mariz, 2020); or via innovative financial instruments, such as labelled bonds (Deschryver & de Mariz, 2020; Bosmans & de Mariz, 2023). Several of these instruments define an explicit price to reward the sustainable aspect of an economic activity or punish the lack thereof. Green bonds are the most well-known sustainable debt instrument. They carry a green premium although it is not guaranteed (Flammer, 2021). Furthermore, this “greenium” is rarely the main factor for an issuer to abide by the Green Bond Principles (Mao, 2023).

In contrast, four types of instruments carry a pre-defined, explicit and enforceable price for sustainable characteristics: carbon credits, renewable energy certificates (RECs), contracts with sustainability clauses, and sustainability-linked bonds (SLBs) or loans (SLLs). Carbon credits relate to financial rewards or penalties tied to the externality of greenhouse gas emissions, in the voluntary or compliance market. RECs represent certificates granting legal ownership of a unit of electricity derived from renewable sources to corporations. Contractual agreements, such as social impact bonds, debt-for-nature swaps, pay-for-results or pay-for-outcome contracts link explicitly a payment, reward or penalty to the achievement of a pre-defined outcome with a clear positive impact on sustainability (de Mariz & Savoia, 2018).

Sustainability-Linked Bonds as a Financial Innovation

SLBs are fixed-income securities whose structural characteristics depend on the issuer’s ability to meet predetermined key performance indicators (KPIs) and sustainability performance targets (SPTs). Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) serve as metrics used to measure and evaluate the issuer’s performance. Sustainability Performance Targets (SPT) represent specific, quantifiable targets that the issuer commits to achieving over the life of the bond. Failure to meet the targets represents a trigger event and may result in financial consequences. SLBs possess a forward-looking nature and bring credibility to an issuer’s sustainability commitment, making them more adept at influencing a shift in corporate behavior. SLBs distinguish themselves from the green, social, and sustainability bonds by adopting a “target-based” approach as compared to the “use-of-proceeds” model. Use-of-proceeds refers to a bond issuance structure where the funds raised are specifically earmarked for a particular purpose or set of projects or specific expenditures. On the other hand, SLB issuers have the flexibility to use the bond proceeds for general purposes. SLB issuers commit to achieving predetermined sustainable targets, which are measured with the help of pre-established key metrics. This feature makes SLBs accessible to a wider range of issuers, especially in hard-to-abate sectors.

If an issuer fails to meet a SPT, they risk facing financial consequences. The most common mechanism is a step-up on the coupon paid. Once an issuer fails to meet the specified target by a specified date, the interest rate on the bond increases, leading to higher costs for the issuer. Step-down mechanisms also exist, albeit less frequently, and work in the opposite manner (IFC, 2023). Under this approach, if an issuer successfully meets its targets, the coupon rate of the SLB decreases, rewarding the issuer with reduced interest costs upon reaching their sustainability goals. The alteration of the bond mechanism linked to a KPI can happen at the target observation date, which is the particular date on which the performance of each KPI is assessed against predefined SPT. The trigger event is the result of the observation outcome of whether a KPI has achieved or not a given predefined SPT. This event may lead to alterations in the financial and/or structural attributes of the bond (ICMA, 2023a). The prevailing market practice involves a step-up of 25 basis points to the bond coupon, with the average step-up amounting to 10% of the original coupon, with a “wide spectrum of variation” (LSEG, 2023). The level of ambition of targets together with the materiality of the step-up represent strong signals of the issuer’s commitment to sustainability and materiality of KPIs.

Many SLB issuers employ third-party verification to independently assess and confirm their achievement of sustainability targets, enhancing credibility and fostering trust among investors and stakeholders.

Evolution of the SLB Market

The world’s first private sector SLB was launched in September 2019 by Enel, a multinational utility based in Italy. At present, cumulative issuance has surpassed USD 250 billion, and represents 7 percent of the overall labeled bond universe (LSEG, 2023). SLBs took only four years to hit USD 250 billion, a milestone that took green bonds a decade to achieve so. While SLBs benefitted from the ecosystem established by green bonds, SLBs also possess distinct characteristics that explain their appeal to issuers and investors alike. SLBs are more prevalent in the private sector than with sovereign borrowers. That said, Chile and Uruguay were the first countries to launch SLBs linked to their Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) in 2022. Both bonds were oversubscribed and attracted new investors (The World Bank Group, 2023), indicating investors’ strong interest and confidence in this asset class, and setting a precedent for other countries.

SLBs are still in their early stages of development, and while studies have explored the presence of a premium for SLBs in the form of a lower price paid by SLB issuers, the available data is not extensive enough to draw definitive conclusions. A comparison with conventional bonds reveals that the average coupon rate of SLBs is 14 basis points lower, and the yield at the time of issue is 9 basis points lower (Kölbel & Lambillon, 2023). This indicates that SLB issuers can potentially benefit from a premium. Moreover, Mielnik and Erlandsson (2022) demonstrated that issuers may experience a notably reduced yield, when the penalty for non-performance is substantial, front-loaded, and sustainability targets are ambitious (Bruegel, 2023).

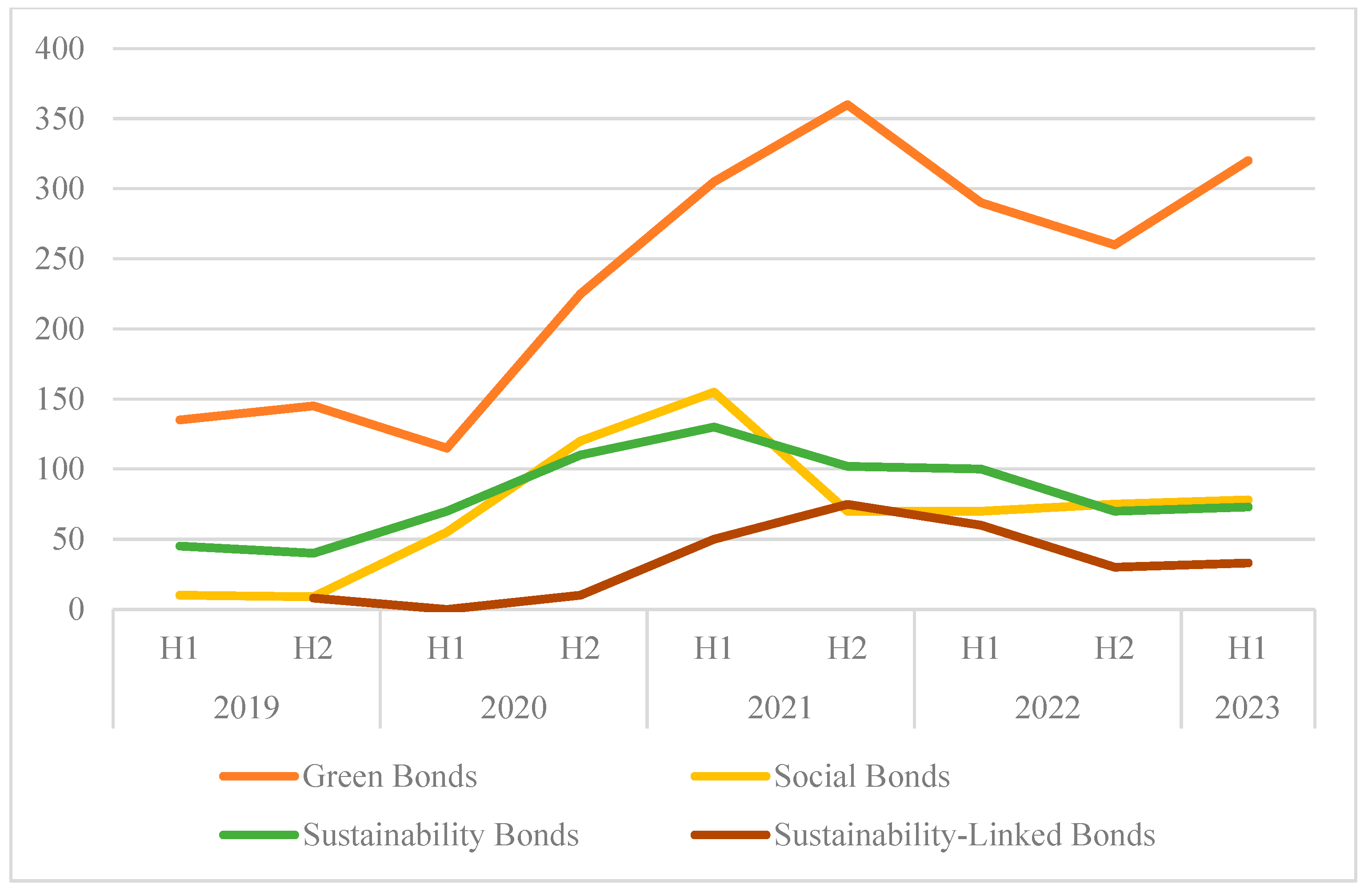

2022 posed challenges for the global capital markets, in particular with tighter monetary policies and heightened geopolitical tensions. In the Green, Social, Sustainable, and Sustainability-Linked Bonds (GSSS) segment, there was a 13% (IFC, 2023) annual decline in issuance, marking the first decrease since the launch of green bonds [

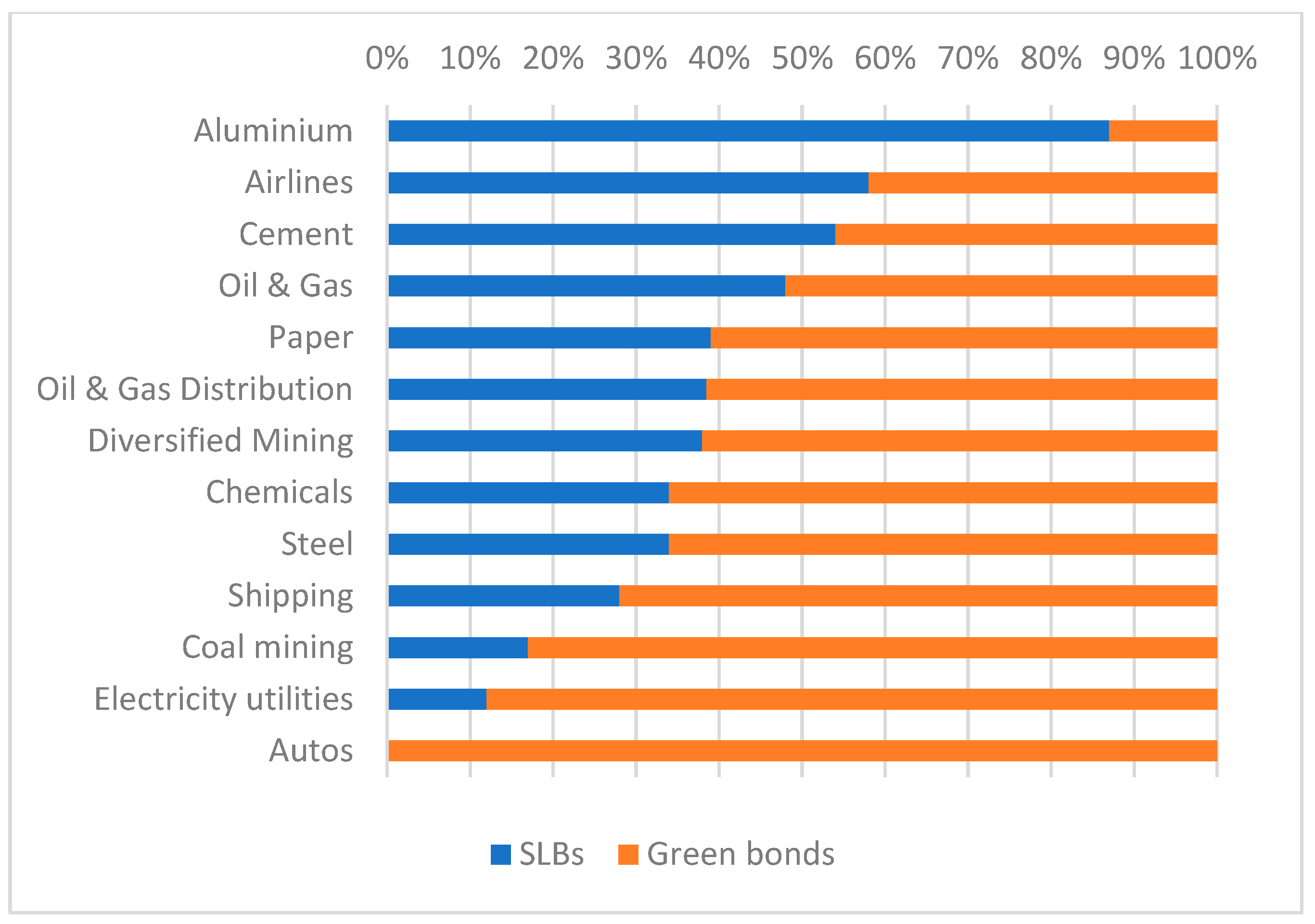

Figure 1]. Despite this contraction, the GSSS segment fared better than the broader fixed-income market, which experienced a more substantial reduction of 26%. Notably, SLB issuances saw a 22% (IFC, 2023) decline in 2022, followed by a recovery in 2023. The SLB market presents a higher proportion of high-yield issuers (28% for SLBs compared to 4% for green bonds), making them especially susceptible to the challenging conditions posed by higher rate levels (LSEG, 2023). SLBs have a higher acceptance than green bonds in hard-to-abate sectors such as aluminum and airlines [

Figure 2]. Indeed, the flexible allocation of proceeds in SLBs significantly broadens the pool of issuers compared to use-of-proceeds bonds.

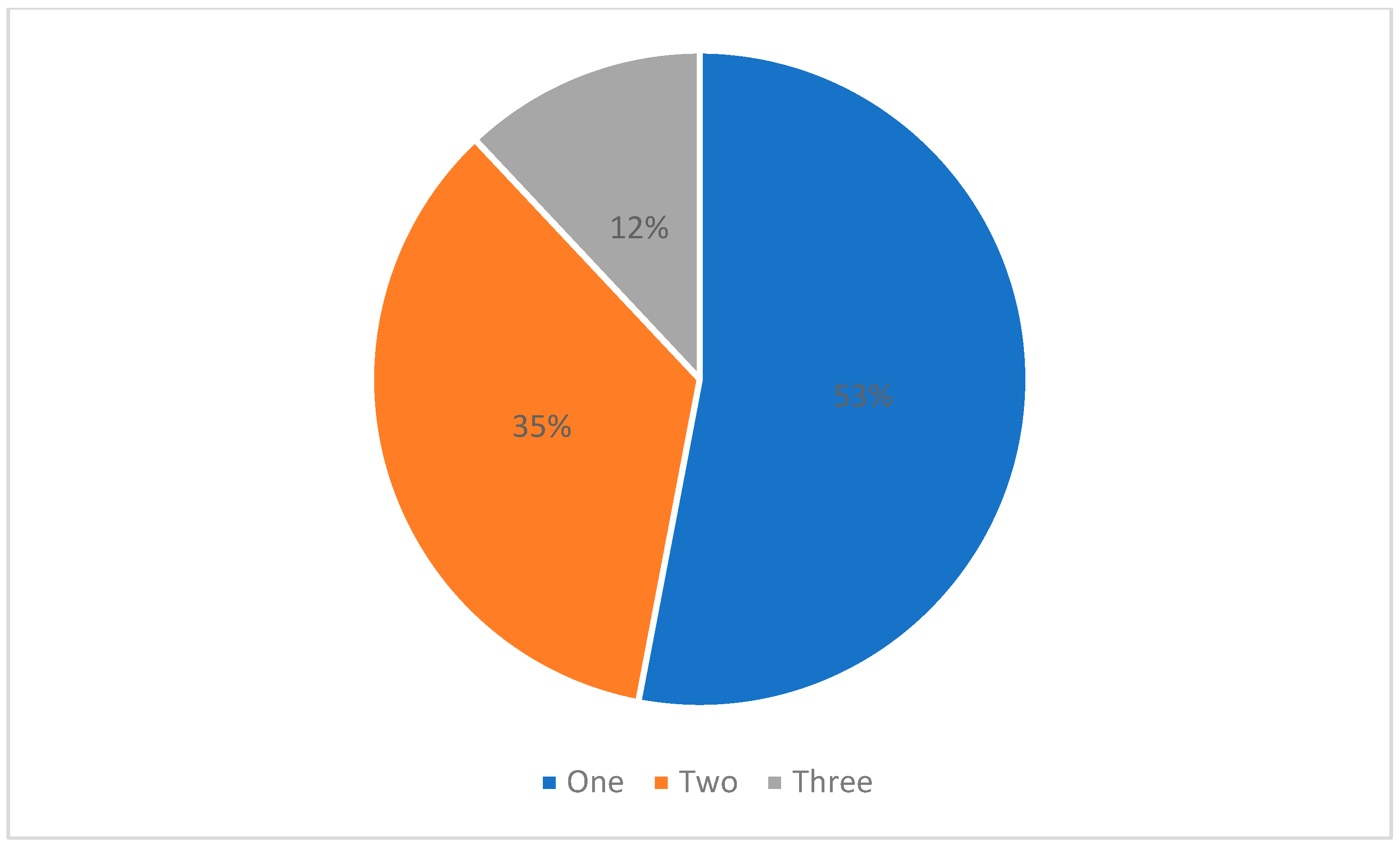

Market data analysis shows that SLBs issued so far relied on one KPI in 53% of the issuances, two KPIs for another 35% of issuance, and three KPIs in 12% [

Figure 3]. As demand grows for a more measurable and less complex SPT mechanism, SLBs with just one KPI may prove more popular with a growing investor base than SLBs with a higher number of SPTs. A preference for a smaller number of SPTs goes hand in hand with a preference for SPTs that are science-based. For example, the European Central Bank (ECB) includes in its asset purchase program only those SLBs connected to SPTs with environmental goals like addressing climate change or environmental harm, excluding enhancements in ESG ratings or scores as valid SPTs. As the SLB market evolves, KPIs may become narrower in range and predominantly focused on environmental elements (S&P Global, 2021a).

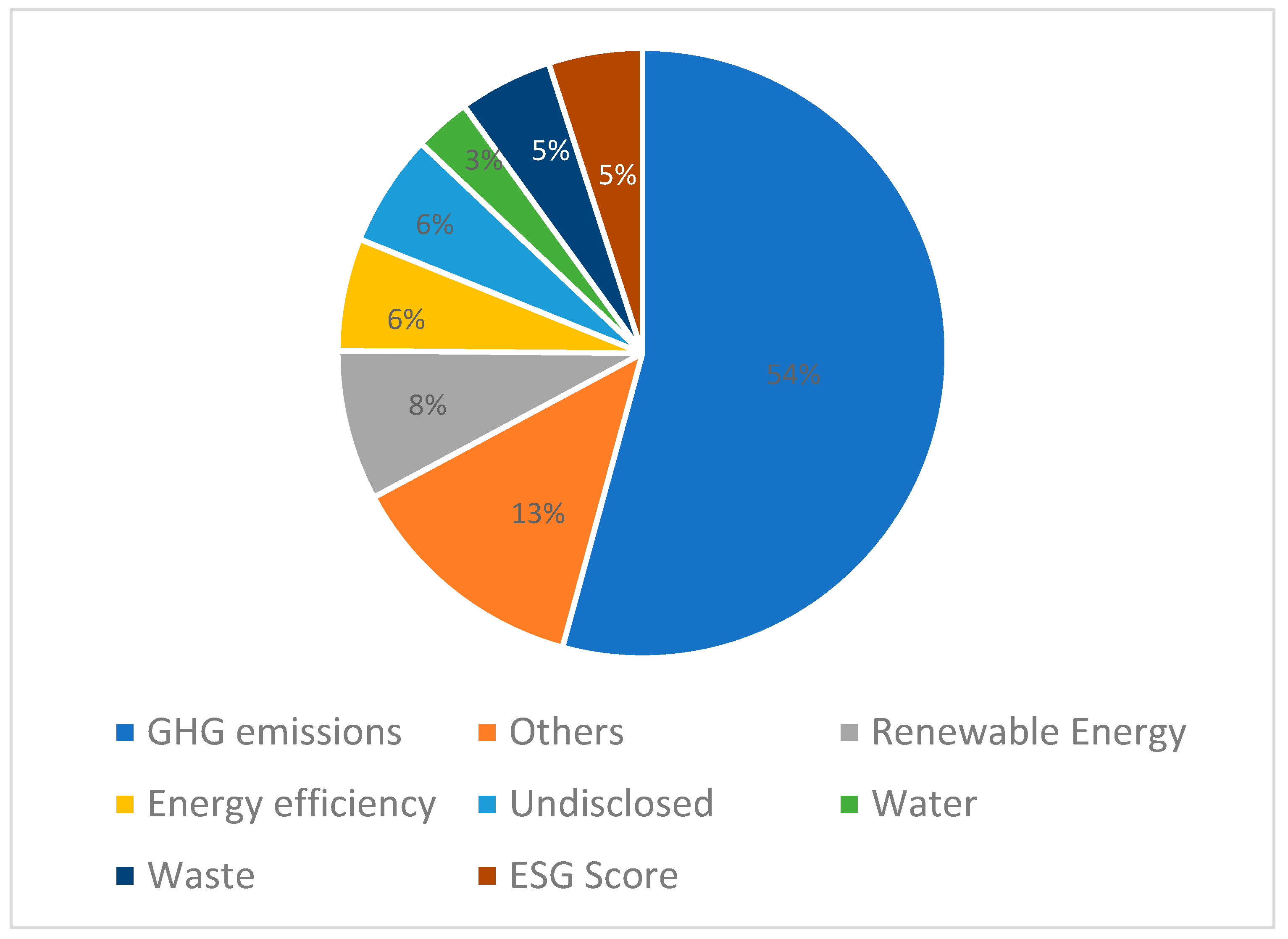

A diverse array of KPIs has been employed in SLB issuance, from greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, ESG score, Waste, Water, Renewable Energy, and Energy Efficiency (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2022). GHG emissions have become the dominant KPI, with approximately 54% of total SLB issuance [

Figure 4]. However, GHG inventory coverage is not sufficiently thorough for the purpose of KPIs (Sustainalytics, 2023). Indeed, in 2022, 33% of KPIs relative to GHG emissions included only Scope 1 emissions, while 44% included two scopes, and 22% three scopes (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2022).

Metrics for carbon emissions KPIs can be categorized as either absolute or intensity-based. Absolute emissions KPIs track total emissions over a time period, targeting a definitive reduction. Intensity emissions KPIs, on the other hand, divide emissions by economic or production output. An intensity-based KPI might offer comparability against other companies or a benchmark.

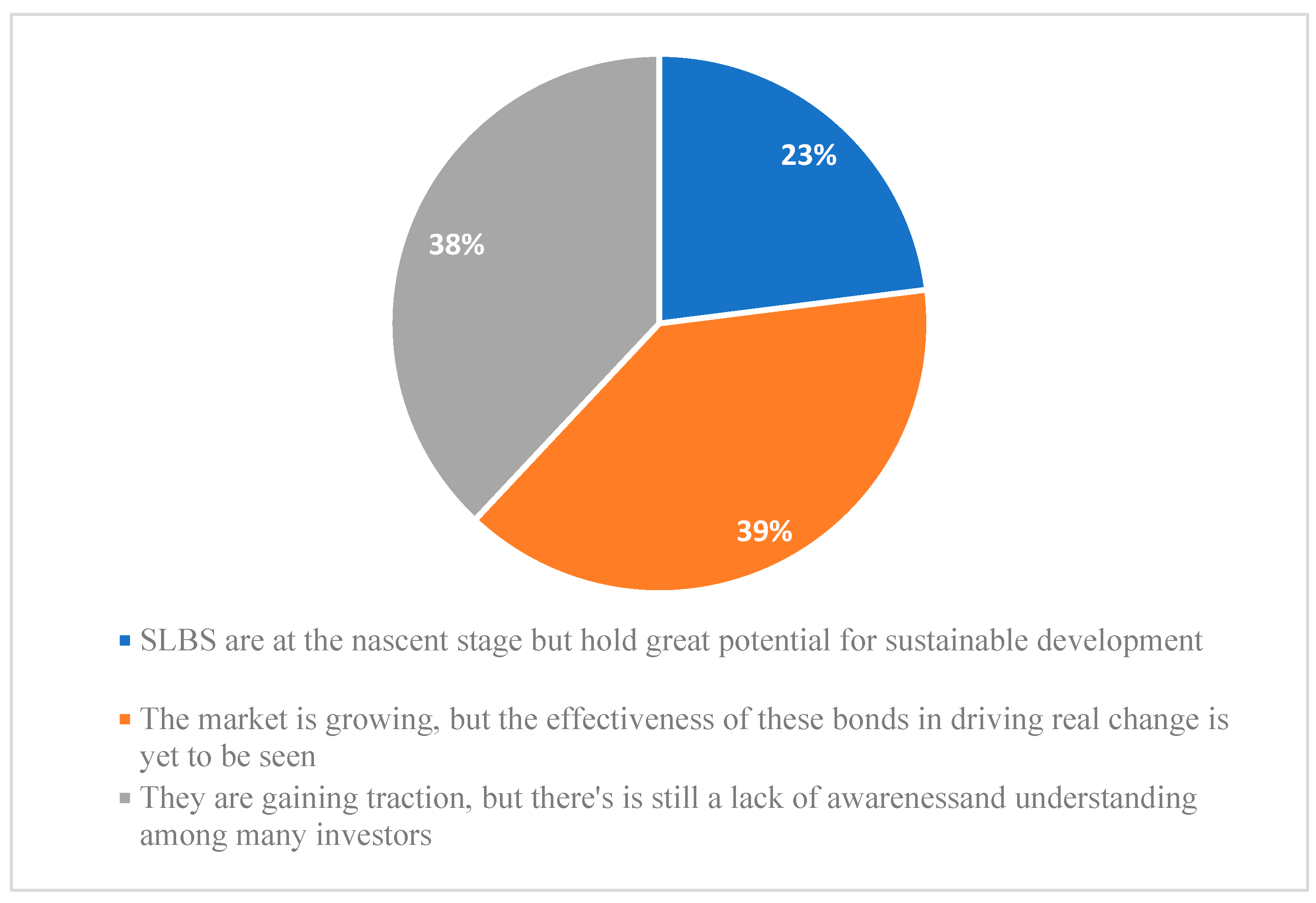

SLB market outlook and potential. In semi-structured interviews conducted with 14 industry experts, when asked about the general impressions about the current state and adoption of SLBs, 39% of respondents claimed that “the market is growing, but the effectiveness of these bonds in driving real change is yet to be seen”. 38% highlighted that SLBs “are gaining traction, but there is still a lack of awareness and understanding among many investors”. An additional 23% mentioned that “SLBs are at a nascent stage but hold great potential for sustainable development” [

Figure 5]. Therefore, respondents present a cautiously optimistic view of the instrument.

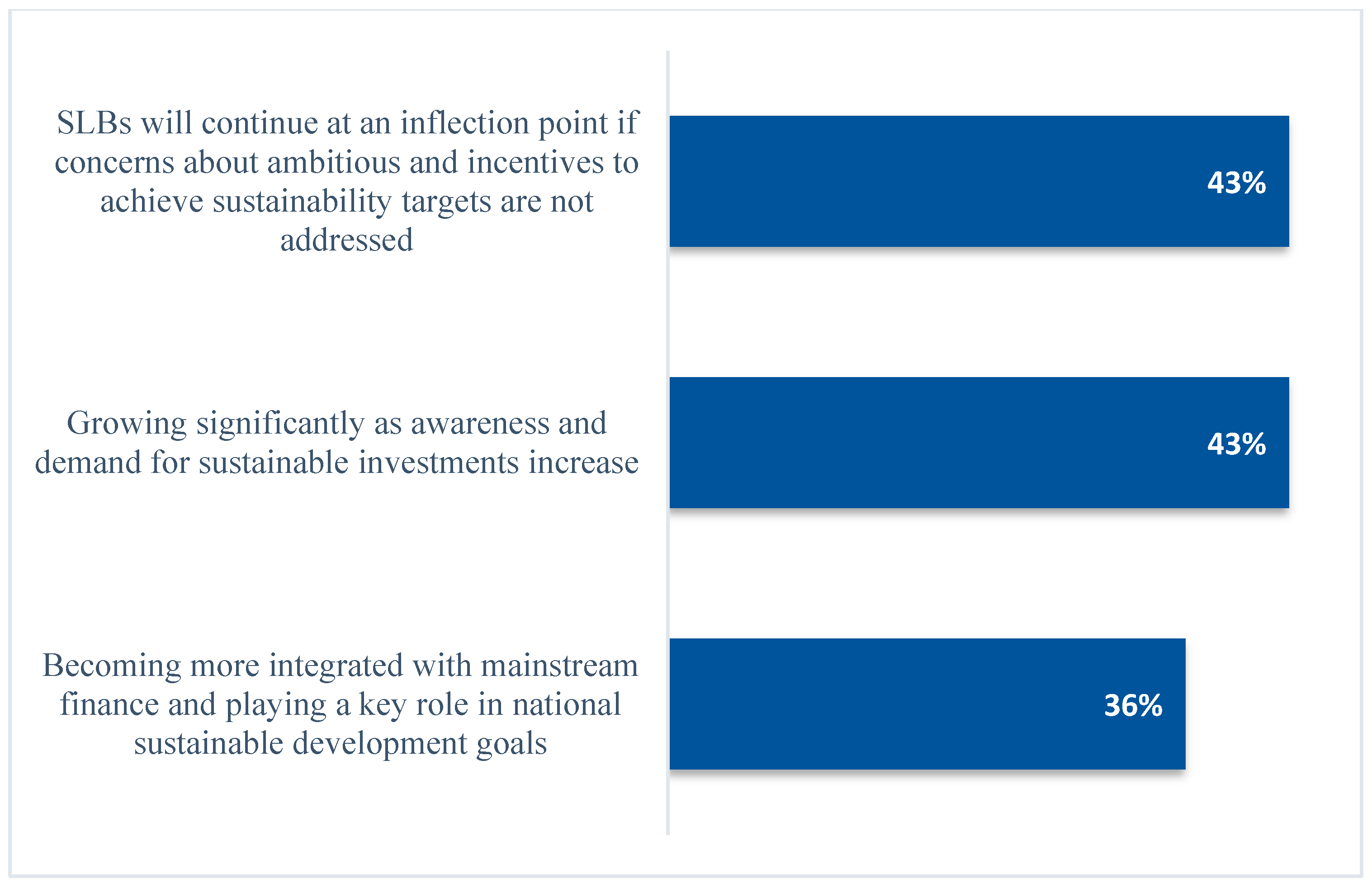

When asked about “where [they] see the market for Sustainability-Linked Bonds in the next five to 10 years”, responses were relatively balanced. 43% of respondents claimed that “SLBs will continue at an inflection point if concerns about ambitions and incentives to achieve sustainability targets are not addressed”. 43% expected SLBs “growing significantly as awareness and demand for sustainable investments increase”. 36% mentioned SLBs “becoming more integrated with mainstream finance and playing a key role in national sustainable development goals” [

Figure 6].

2. Limitations of SLBs

SLB design flexibility is currently perceived to have shortcomings, each of which can lead to greenwashing concerns for both issuers and investors. A literature review has highlighted SLB limitations across five categories: KPI selection, SPT calibration, bond characteristics, reporting and verification, and costs of issuance (ISS Insights, February 2022) (Burke, 2023) (S&P Global, 2023) (Segal, 2023) (Ritchi & Tugwell, 2022) (World Economic Forum, 2022). Authors have mentioned shortcomings in “data transparency, disclosure, adoption of global standards and the lack of international rating” (Pianese, 2023). A review of the literature points to five shortcomings of SLBs.

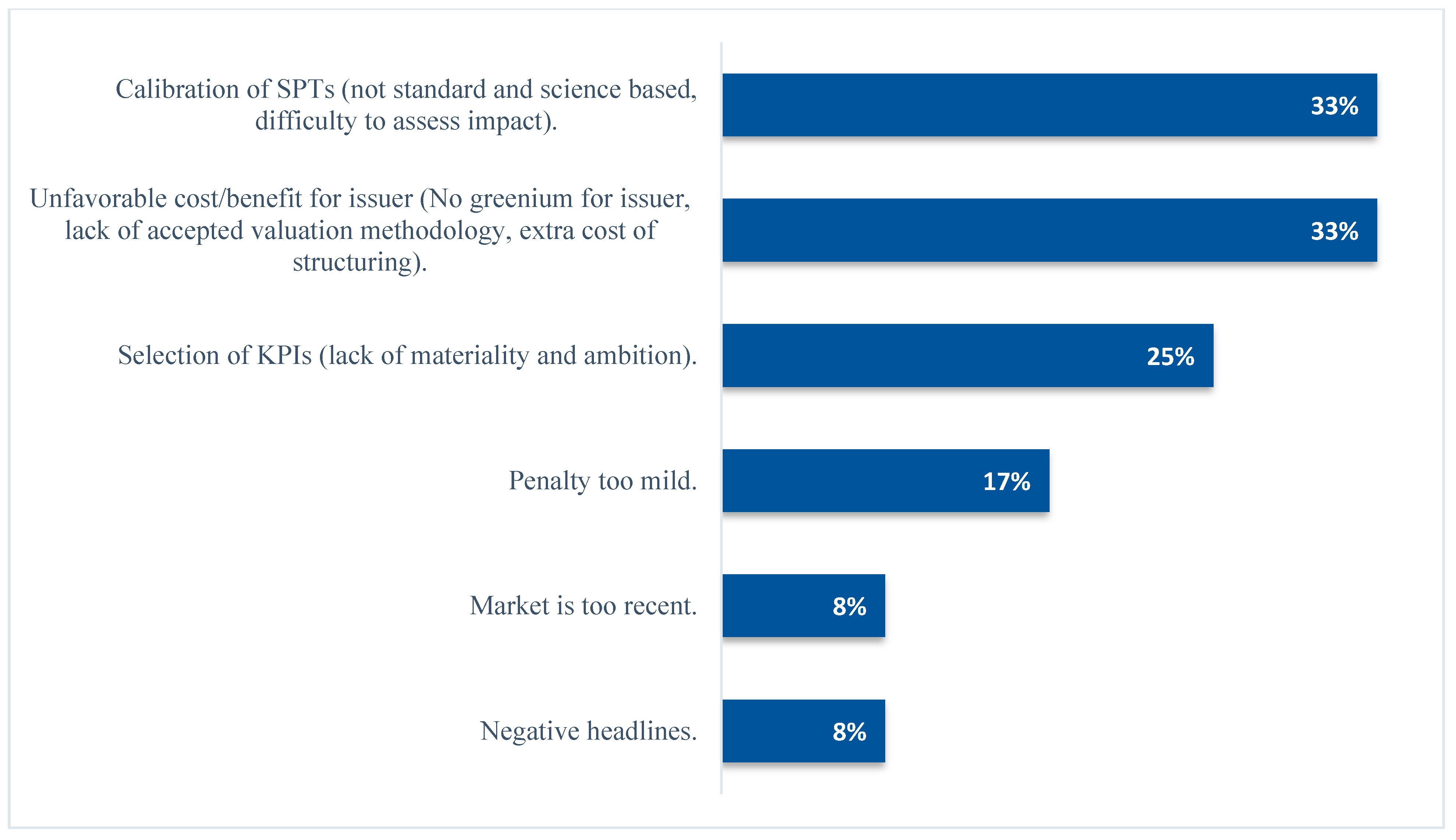

The semi-structured interviews with experts reinforced and prioritized the list of limitations and criticisms [

Figure 7]. 33% emphasized concerns with the calibration of SPTs, in particular the fact that targets are not standardized and not always science-based, or that it is difficult to assess impact, especially to determine whether SLBs could be fit for impact-focused investment strategies and article 9 funds under SFDR regulation. 33% percent noted an unfavorable cost-benefit for the issuer, with a lack of financial benefit for issuers and an additional cost for structuring SLBs, with no clear greenium or reduction in yield at the time of issuance, especially driven by a lack of consensus on the valuation methodology tailored to SLBs. 25% percent of respondents pointed to concerns with the selection of KPIs, such as their lack of ambition, or materiality. 17% noted that penalties (coupon step-up) defined in the bond mechanism are too mild. Finally, other concerns included the fact that this market is still new and will need more proof of concept, and negative headlines with select corporations missing their targets at the observation date.

Bond Characteristics

SLB characteristics– including an observation date too close to maturity, the callable nature of bonds and a mild penalty – is sometimes a cause of concern for markets. In certain instances, the financial penalty for not meeting predetermined targets may lack the material impact needed to motivate the entity to achieve its goals. A study from IFC has found that SLBs are approximately three times more likely to be callable (65% of instances) than corporate green bonds (23%) and approximately five times more likely than conventional corporate bonds (12% of instances) (IFC, 2023). Mild penalties for unmet goals and well as callable options on bonds may suggest issuers are not committed to their sustainability goals. Prominent early investors in green bonds have criticized SLBs for their lack of transparency regarding how proceeds contribute to improvements in issuers' sustainability performance, the potential “gaming” of SPTs to make them easily achievable, and the insufficient incentivization provided by performance-based coupon adjustments (Vulturius, Maltais, & Forsbacka, 2022). In contrast, select penalties might be seen as too high, especially in a context of rising rates for companies with strained cash flows, potentially putting additional pressure on issuers’ credit risk (Hermes Investment, 2022). The European Banking Authority, cited by S&P Global (S&P Global, 2023), notes that concerns over coupon rates highlight the complications of step-ups for issuers’ debt management offices. While KPIs and SPTs evidence flexibility and allow for innovation, research has pointed the lack of customization of SLBs step-up mechanisms, illustrated by limited correlation of coupon step-up and credit ratings, as noted in the Fitch Sustainability-Linked Bond Progress Report. Markets have customarily implemented a one-size-fits-all step-up mechanism of 25 basis points for most issuers.

Reporting and Verification

The need for reporting and performance assurance is a consensus (Climate Bonds Initiative, 2023a). The reliability of issuer performance against set targets is frequently dependent on self-reporting and unaudited practices. Consequently, performance may not be consistently or reliably reported. However, third-party verification as a mechanism is now being adopted by several issuers to provide more credibility to their issuances. In some countries such as Brazil, auditing baseline is a requirement for new SLBs, which goes beyond ICMA rules that only recommend a verification of baseline (de Mariz, 2022).

In order to obtain assurance, timely data availability is critical. Indeed, data should be accessible at a reasonable cost; attributable (“plausibly associated with […] interventions”; recent (“current and produced with enough frequency”); regular (“provided in sequence with equal intervals between them over a long period of time”); and comparable across countries (The World Bank Group, 2021). Those principles are largely aligned with ICMA’s reporting guidelines, in which: SLBs should have “up-to-date” performance information, “verification assurance report” relative to SPTs outlining KPI performance, information available for investor’s assessment of KPI level of ambition (ICMA, 2023a).

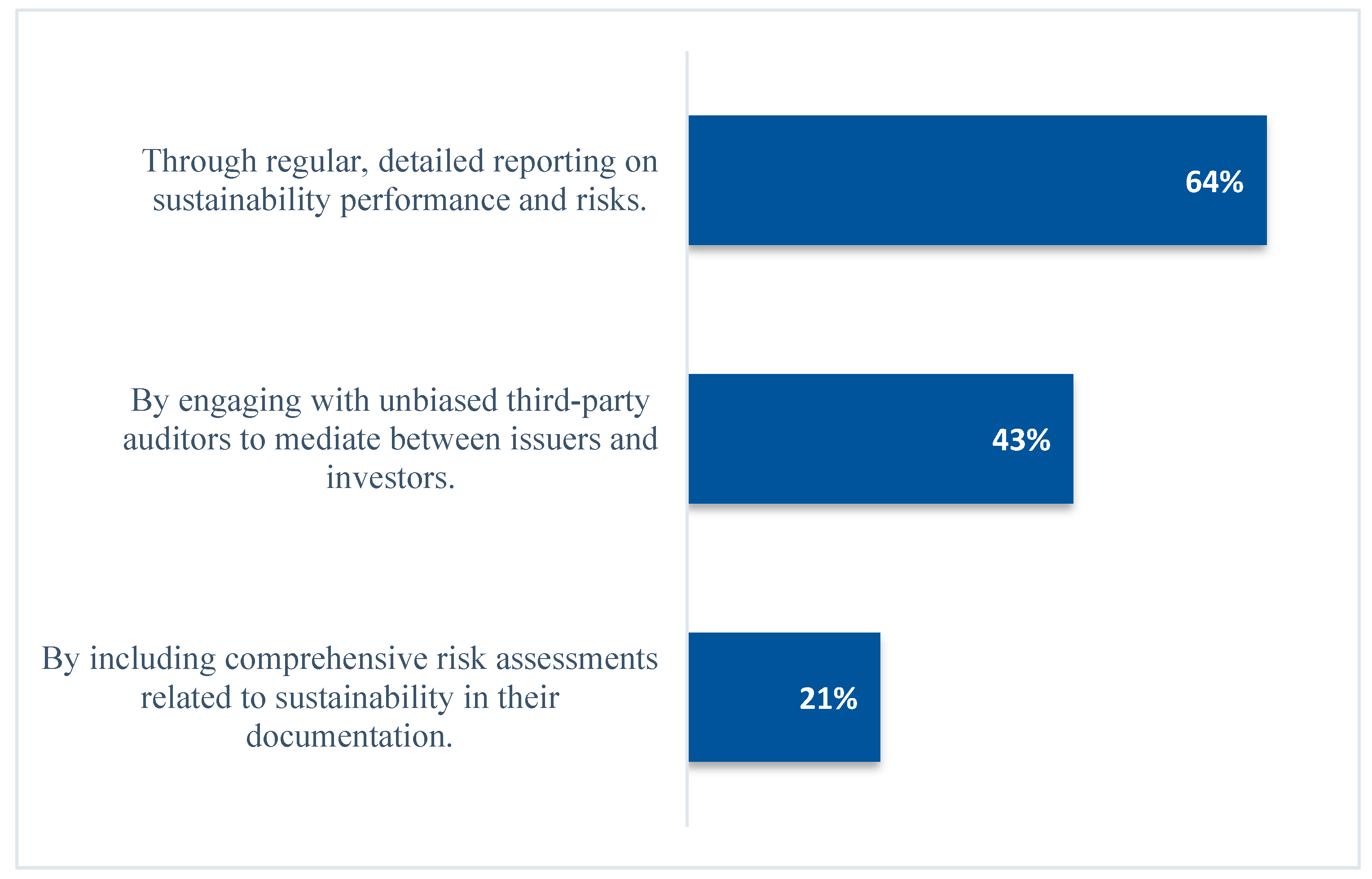

When asked how SLBs could be better designed to address sustainability-related risks, 64% of respondents mentioned “regular, detailed reporting on sustainability performance and risks”. 43% emphasized the opportunity to “engage with unbiased third-party auditors”, while 21% noted the role of “including comprehensive risk assessments related to sustainability in their documentation” [

Figure 10]. Responses therefore combined pre-issuance risk assessment, third-party assurance as well as post-issuance reporting and disclosure, providing transparency to investors.

Cost Related to SLB Pre- and Post-Issuance

Finally, pre-issuance and post-issuance of SLBs represent an extra cost for issuers, in the form of monetary expense and resource allocation. In particular, before the issuance takes place, issuers need to disclose a SLB framework, hire a second-party opinion to provide an expert’s view on this framework, define and audit a baseline. After the issuance takes place, the issuer will need to maintain frequent disclosure of its evolution toward the achievement of its targets. Moreover, the flexibility in KPIs and SPTs, while positive for issuers, can represent an additional operational burden or challenge for asset managers and investors who need to familiarize themselves with new targets. However, we note that this extra cost, either monetary or not, is not different from what is observed in use-of-proceeds instruments, such as green bonds.

3. Enhancing SLB Design to Strengthen Market Trust

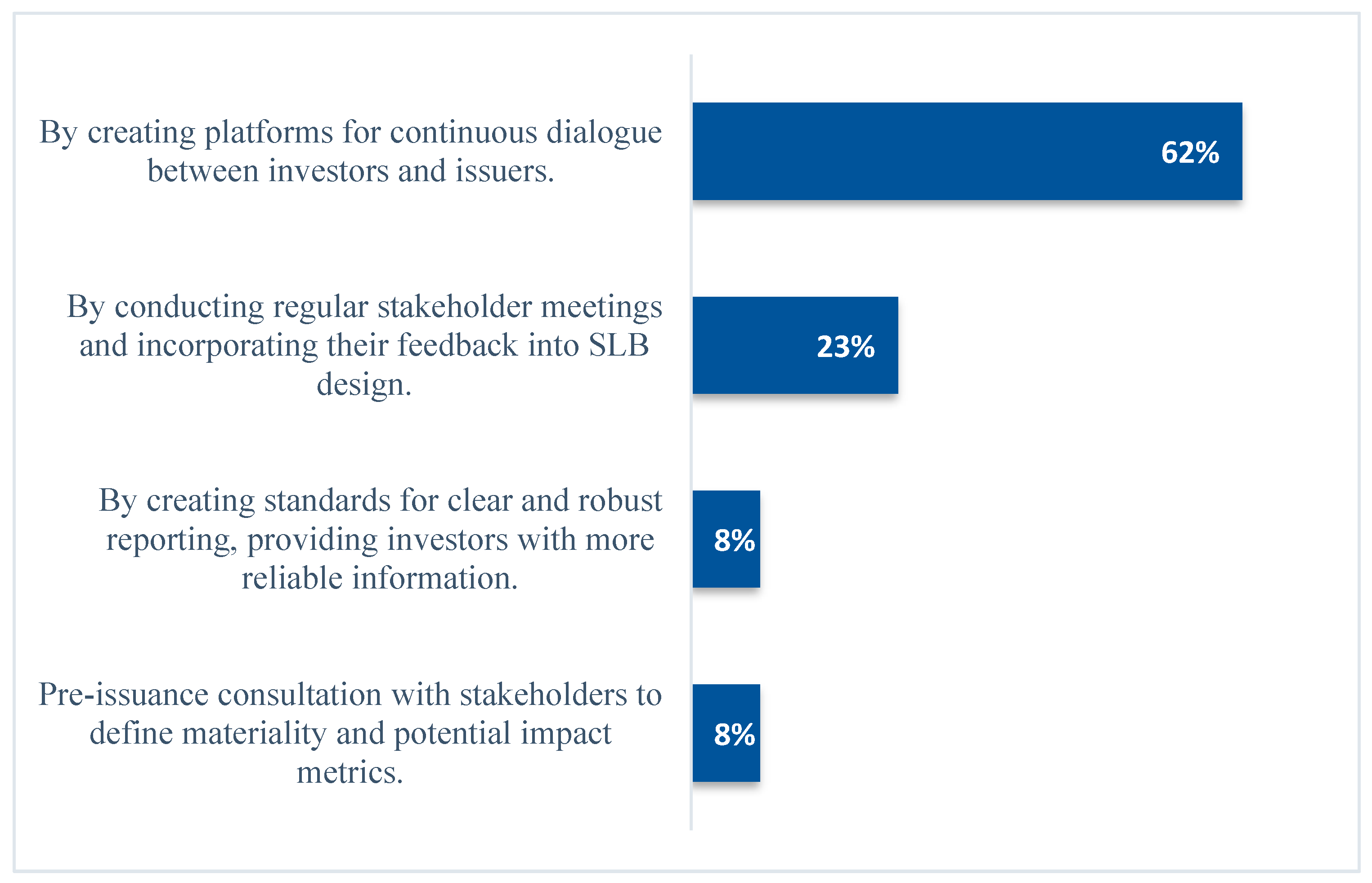

This section of the paper details what actions can be taken to address the concerns described in the previous section, to enhance SLB design and support investor trust in this innovative financial instrument. An overall way to enhance SLBs is to engage stakeholders in its design. Drawing on semi-structured expert interviews, 62% of respondents emphasized the role of “creating platforms for continuous dialogue between investors and issuers” [

Figure 12]. 23% percent noted the importance of “conducting regular stakeholder meetings and incorporating their feedback into SLB design”. Finally, 8% highlighted the role of standard reporting and another 8% the role of pre-issuance consulting with investors to define materiality and KPIs. Overall, responses evidenced a preference for board industry platforms, such as investors’ groups, followed by one-on-one tailored interactions between prospective issuers and investors.

Selection of KPIs

The lack of standardization in metrics presents issuers and investors with reputational risks. Aligning performance indicators with recognized reporting standards and external benchmarks will facilitate their broader adoption in SLBs (The World Bank Group, 2021). For greater clarity and reliability, KPIs should be externally verifiable and disclosed frequently. This alignment is essential to validate the issuer’s ambition. In fact, issuers are expected to transparently articulate the selection process of KPIs, detailing the underlying logic and materiality assessment. A comprehensive explanation encompassing the baseline data, calculation methods, and eligibility criteria is necessary to meet industry standards (ICMA, 2023b). Collaboration with key stakeholders including ICMA, credit rating agencies, or external sustainability experts to support the selection of KPIs based on an issuer’s sustainability theme is also advised. KPIs need to be relevant, aligning with UN SDGs and the Paris Climate Agreement (The World Bank Group, 2021). The ICMA's new KPI registry (Chesné, 2022), offering 300 pre-validated KPIs across 22 sectors complete with sector materiality matrices, serves as a resource for issuers to align their KPIs with their strategic goals. Although participation is voluntary, this registry is poised to become a cornerstone for third-party verification, potentially addressing the issue of insufficient investor trust.

Calibration of SPTs

The lack of comparability of performance targets between issuers and how trigger events can lead to financial impact for issuers can lead to information asymmetry in the market, which is negative to investor trust (LSEG, 2023). SPTs projected a decade into the future mirror current expectations around sustainability. However, the absence of a midway assessment point can lead to these targets becoming less relevant or challenging as time progresses, especially in cases where the targets are tied to external ESG scores or indices, which may evolve over time. ICMA (2022) recommends issuers to incorporate an intermediate assessment date for their performance targets.

The case of Suzano, a global pulp & paper company headquartered in Brazil, offers a compelling example of a successful implementation of the ICMA principles. Suzano raised SLBs worth USD 2.75 billion in SLBs, reflecting the company’s commitment to align its funding needs with the sustainability targets integrated in their core strategy (Mielnik & Erlandsson, 2022). Suzano's 2020 SLB, distinguished as the "Sustainability-Linked Bond of the Year" in 2021 by Environmental Finance, set a notable precedent as the first globally to secure a voluntary second-party opinion (Environmental Finance, n.d.). This pioneering step underlines two critical aspects for the analysis of SLBs. First, it underscores the paramount importance of having precise and readily available data for the accurate pricing of options. In the context of SLBs, providing comprehensive datasets for investors is crucial yet not a standard practice. Such transparency can substantially reduce the uncertainty premium that investors might otherwise require due to unclear dynamics of KPIs. Second, the valuation of the SLB is significantly influenced by the assumptions made about the company's potential performance trajectory had it not issued the SLB. This aspect of 'counterfactual' analysis is vital. By presenting a well-founded scenario for these counterfactuals, issuers like Suzano can mitigate the uncertainty premiums. This approach is akin to the established norms in Credit Default Swap (CDS) pricing, where certain recovery values are conventionally accepted (Mielnik & Erlandsson, 2022). This strategic combination of data transparency and robust counterfactual reasoning plays a key role in the successful issuance and reception of SLBs like that of Suzano.

Bond Characteristics

The Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) Invest published guidelines on how to advance SLB design. The guidelines recommend trigger events to occur well before the bond’s maturity or call date. Additionally, to counter the misuse of voluntary call options, contractual terms should ensure that any early calls include the coupon step-up if KPIs are not met. According to the IFC (2023), there is already a growing trend towards using contractual terms more rigorously. Lastly, "KPI restatement mechanisms" need clearer constraints – any such changes should require bondholder approval (Cavosoglu, Oldani, Paris, Pamponet Moura, & Carillo Sosa, n.d.). Sixty-four percent emphasize that increased mandatory transparency and consistent reporting standards would bolster investor confidence in SLBs, and 50% advocate for third-party verification (Burke, 2023) to strengthen credibility.

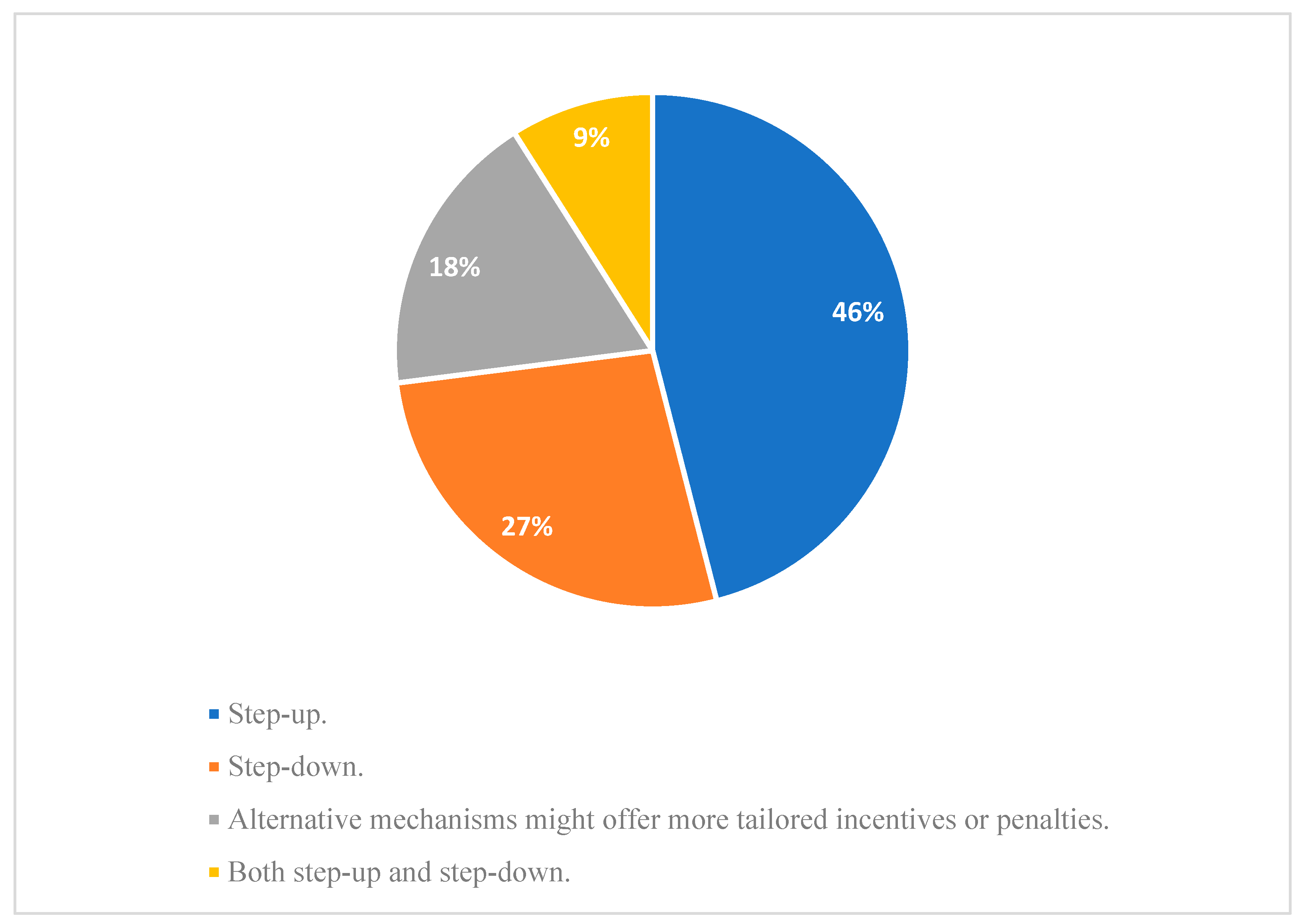

When asked about the type of bond mechanisms, 46% showed a preference for step-up mechanisms. Surprisingly, the difference with other mechanisms was not as large as current market practice may have suggested. 27% mentioned step-downs, and 9% mentioned both step-up and step-down mechanisms should be used in an issuance. Finally, just 18% suggested to use other tailored mechanisms, showing a clear preference for simple and relatively standardized mechanisms [

Figure 13].

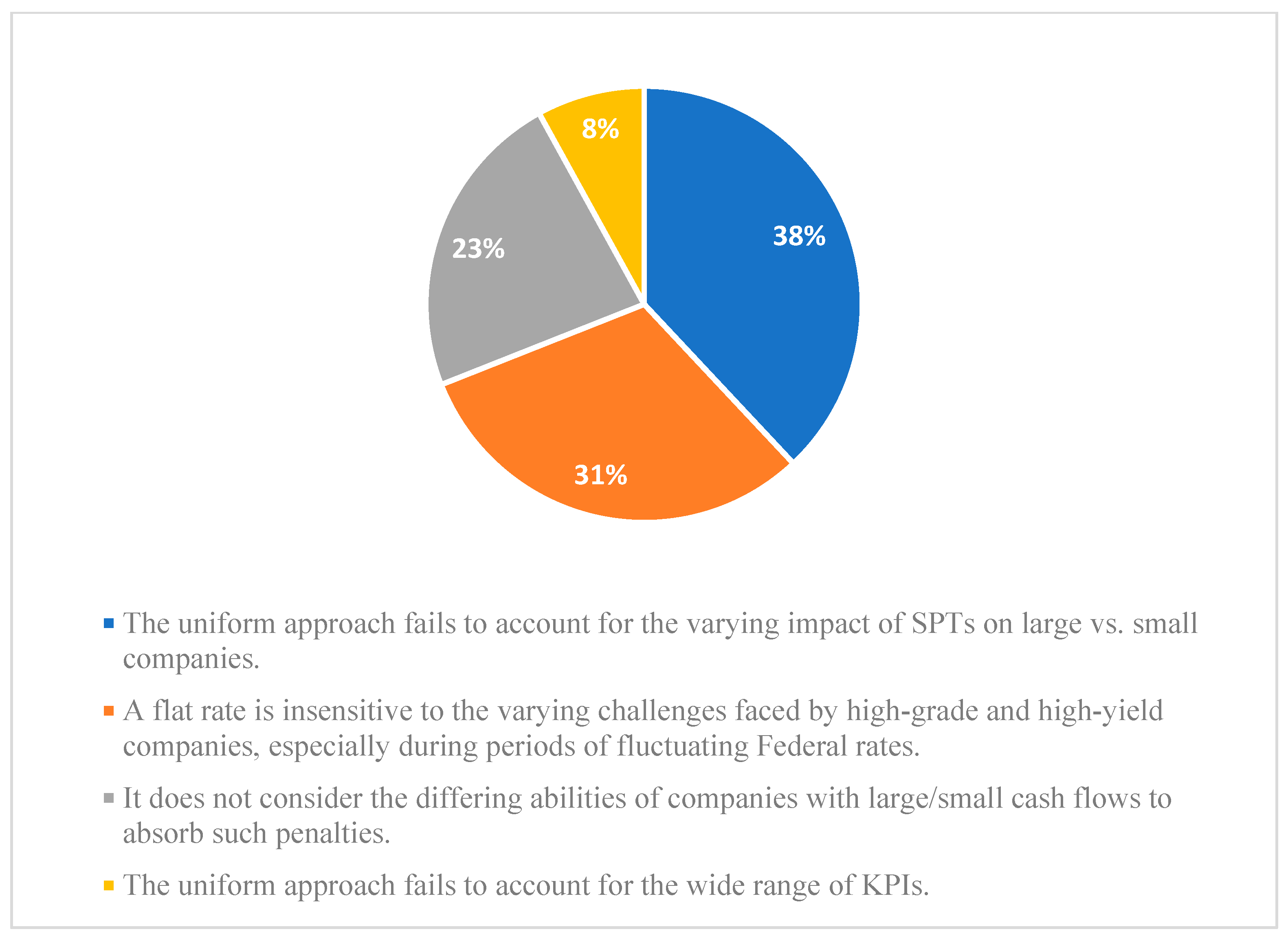

The preference for step-up mechanisms is evident. However, criticism remains on the uniform nature of the step-up mechanism, given that the majority of the market applies a 25-basis points step-up. Thirty-eight percent of respondents noted that the “uniform approach fails to account for the varying impact of SPTs on large versus small companies”. Thirty-one percent highlighted that a “flat rate is insensitive to the varying challenges faced by high-grade and high-yield companies”, especially during periods of rising rates. Twenty-three percent of respondents explained that a standard step-up does not consider the differing abilities of companies referring to their cash flows to absorb such penalties. Finally, just 8% mentioned that the standard step-up of 25 basis points “fails to account for the wide range of KPIs” [

Figure 14]. In the respondents’ words, a one-size-fits-all approach with a 25-basis points step-up mechanism has shortcomings as it ignores the size, credit quality, repayment ability of the issuer as well as the wide variety of KPIs.

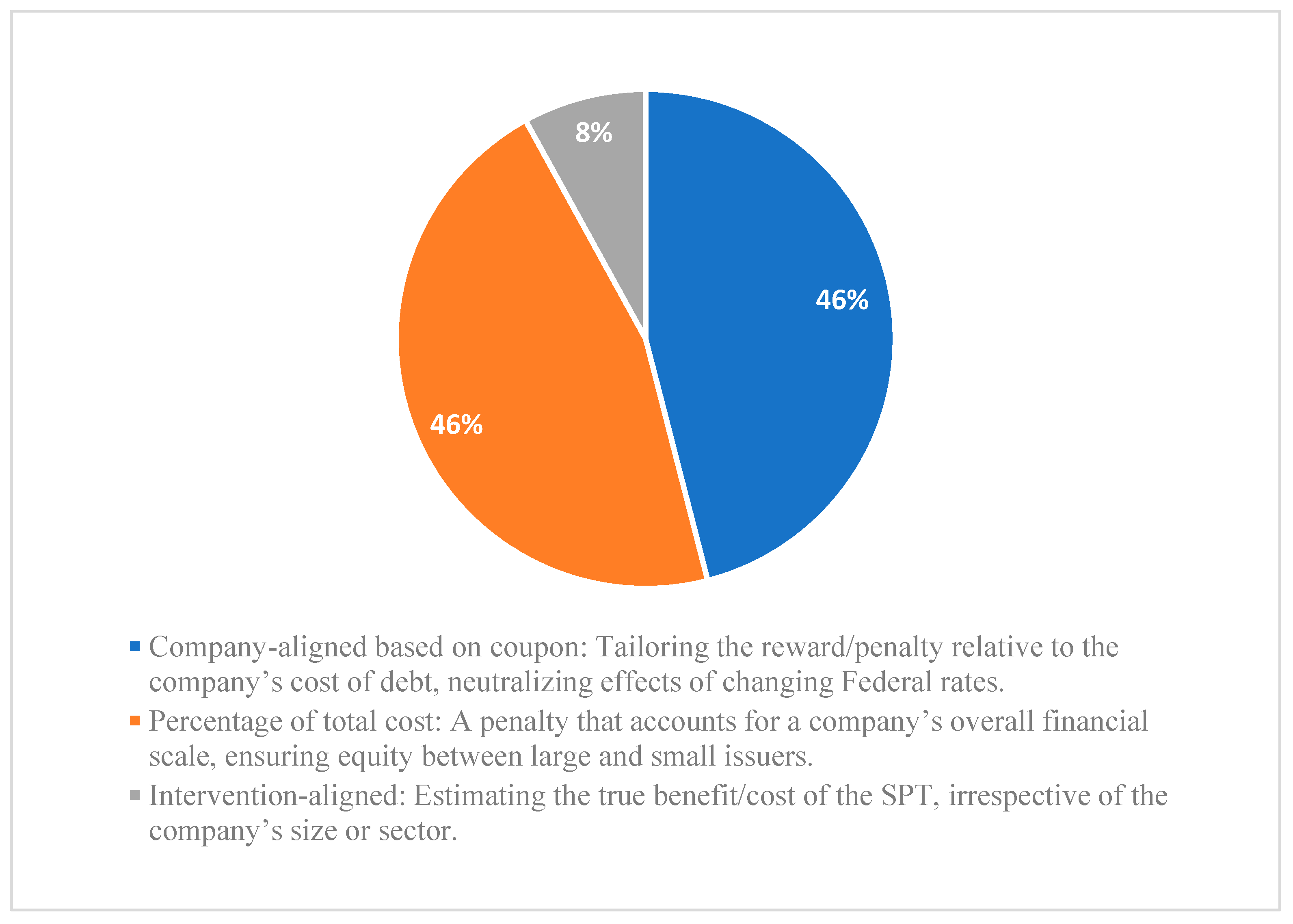

To remedy the one-size-fits-all simplification of the step-up coupon, 46% of respondents suggest that the step-up should be aligned with the coupon, “tailoring the reward relative to the company’s cost of debt”, neutralizing the effects of changing Fed fund rates. Forty-six percent believe the step-up mechanism should take into consideration the “company’s overall financial scale, ensuring equity between large and small issuers”. Finally, only 8% estimate that the step-up should be determined by the SPT, in an attempt to calculate the “true benefit/cost of the SPT”, irrespective of the issuer. Respondents showed a clear preference to anchor the definition of step-up to the total coupon of the issuance or to the total interest expense of the issuer [

Figure 15].

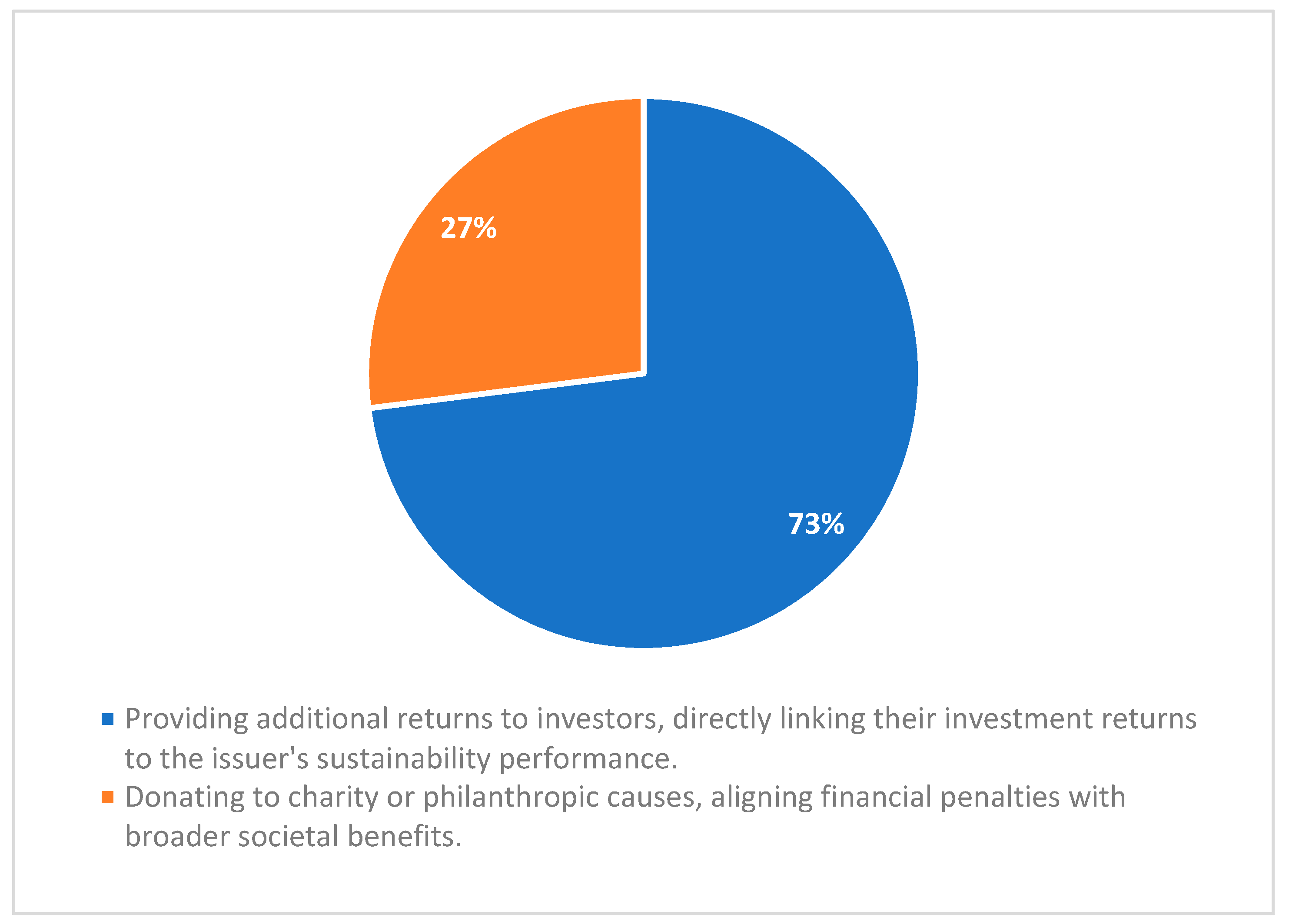

The vast majority (73%) estimate that the step-up mechanism should lead to a higher interest payment in the benefit of the investor, while 27% defend different options, such as the purchase of carbon offsets or donations to philanthropic projects, in order to avoid a perverse incentive whereby investors benefit from the non-attainment of SPTs [

Figure 16].

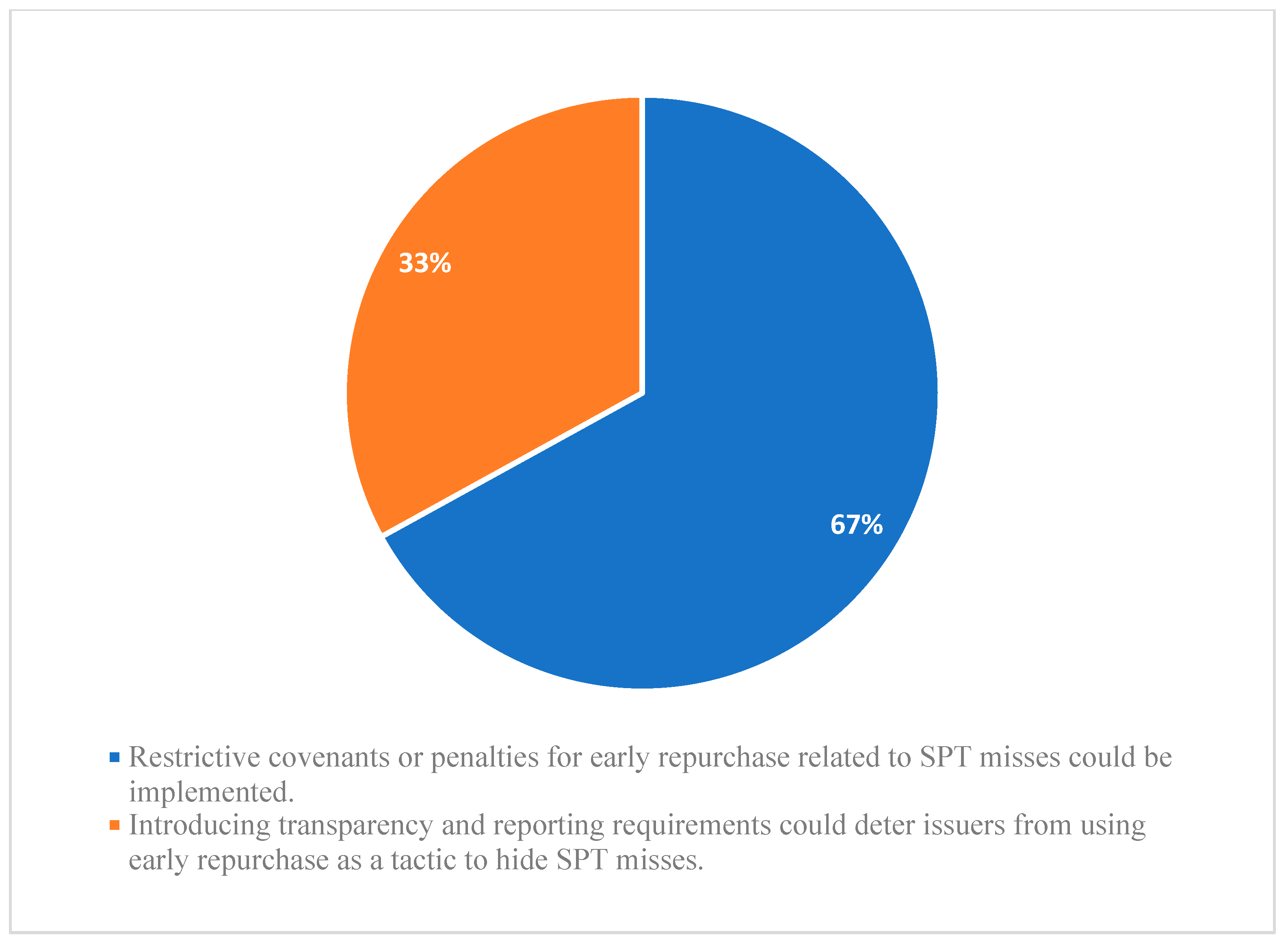

Bond mechanisms also include callable features. In order to avoid issuers using call options to conceal a missed target, 67% of respondents suggest “restrictive covenants or penalties for early repurchase”. Thirty-three percent suggest that enhanced transparency and reporting could deter issuers using the call options to hide a missed target [

Figure 17]. Respondents therefore go beyond the current market practice of limiting a target miss to reputational damage. Missing a sustainability target does not commonly constitute an event of default in bond terms.

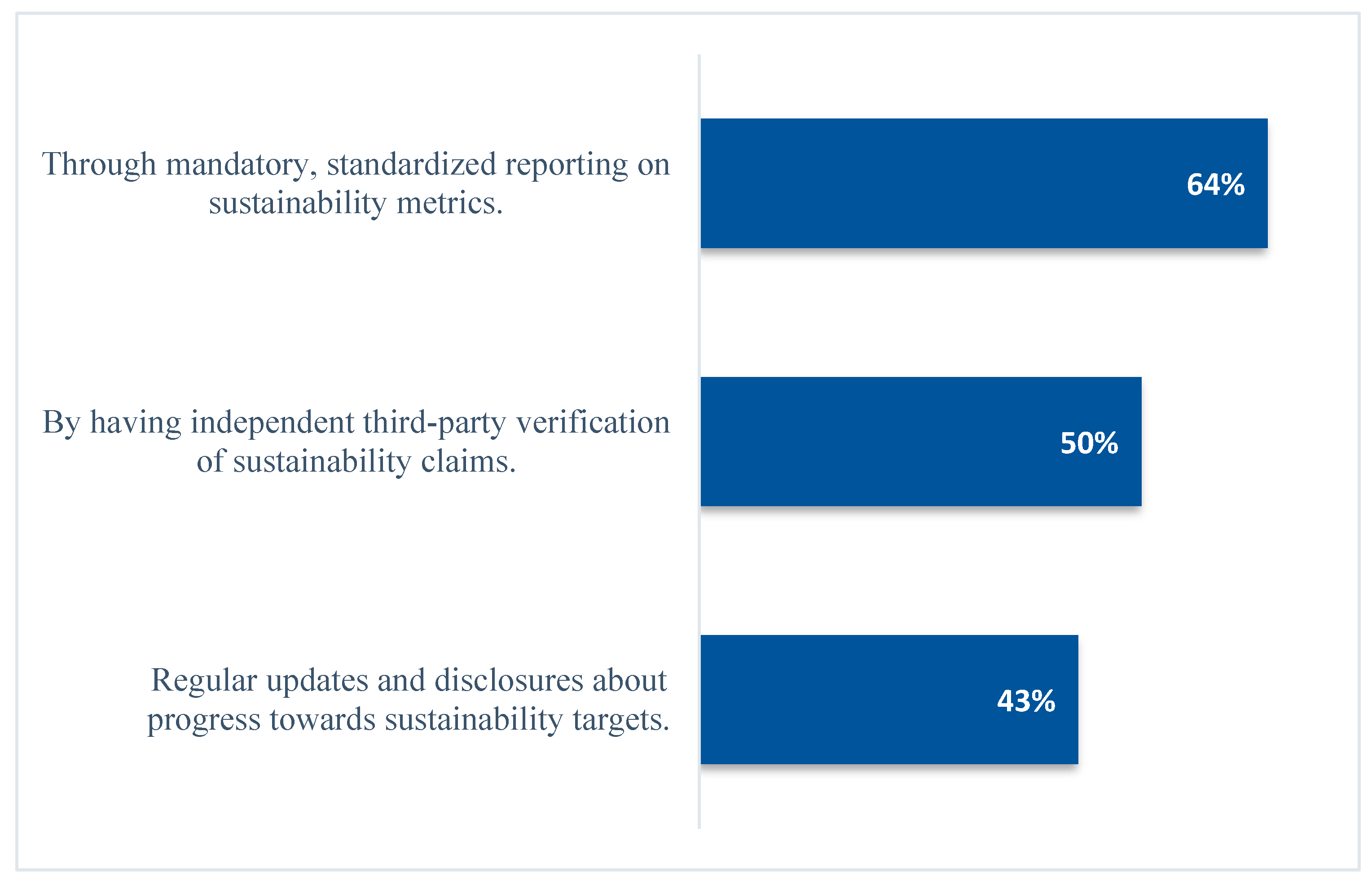

Reporting and Verification

Disclosure of advancement towards the issuer’s targets must rely on data sources that are credible and can be independently verified. To enhance transparency and reporting, 64% of respondents demand “mandatory, standardized reporting on sustainability metrics”. Fifty percent require “having independent third-party verification of sustainability claims”, while 43% mention “regular updates and disclosures about progress towards sustainability targets” [

Figure 18].

Potential for Growth

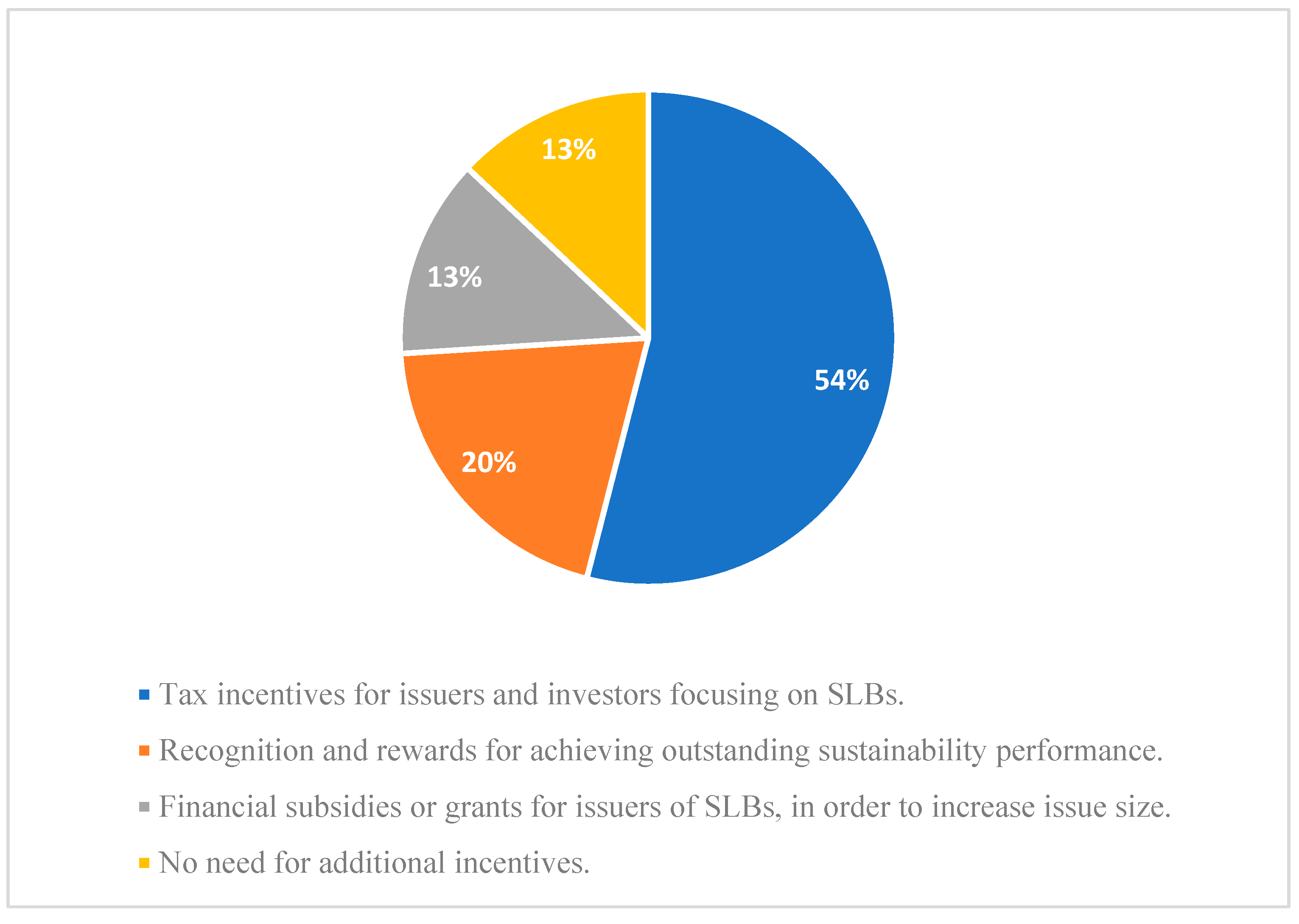

When addressing potential solutions to enhancing transparency and improving reporting, regulatory public bodies enforcing transparent SPT reporting (IFC, 2023) came to light. Fifty-four percent of our survey respondents answered that, to stimulate market participation, tax incentives for issuers and investors focusing on improving SPTs are recommended, which would offset additional reporting and third-party verification costs. Nevertheless, according to our interviews, one may argue tax incentives are not sustainable in the long-term.

When asked about potential incentives given to issuers or investors to support the SLB market, 54% mention tax incentives, 20% highlight “recognition and reward for achieving outstanding sustainability performance”, 13% would explore the potential subsidies or grants, and another 13% express there is no need for incentives [

Figure 19].

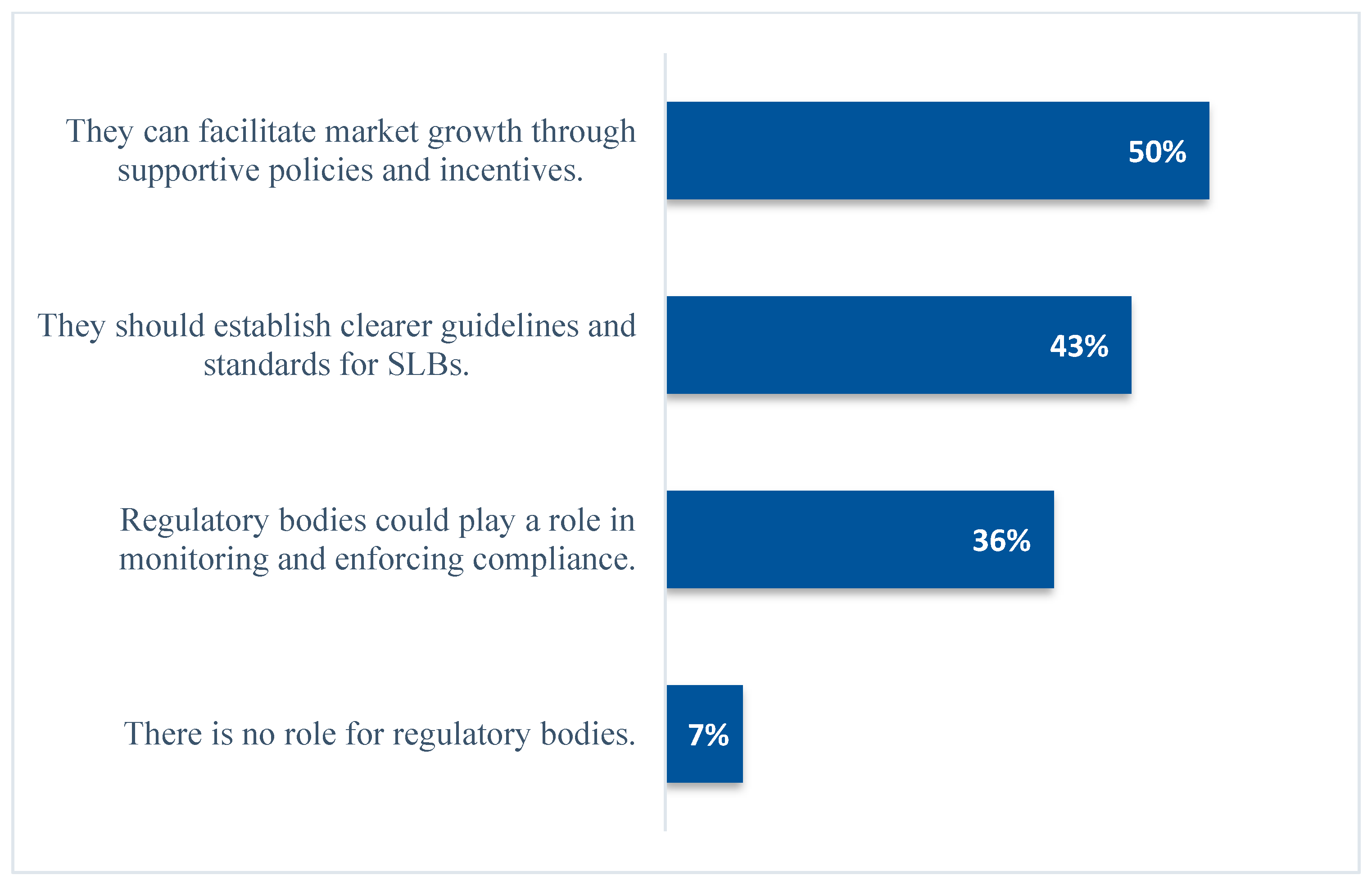

Similarly, 50% mention that regulatory bodies “can facilitate market growth through supportive policies and incentives”, while 43% defend the role of regulatory bodies as rule setters, with “clearer guidelines and standards for SLBs”. However, 36% flag the role of regulators for “monitoring and enforcing compliance”, and 7% see no role for regulators [

Figure 20].

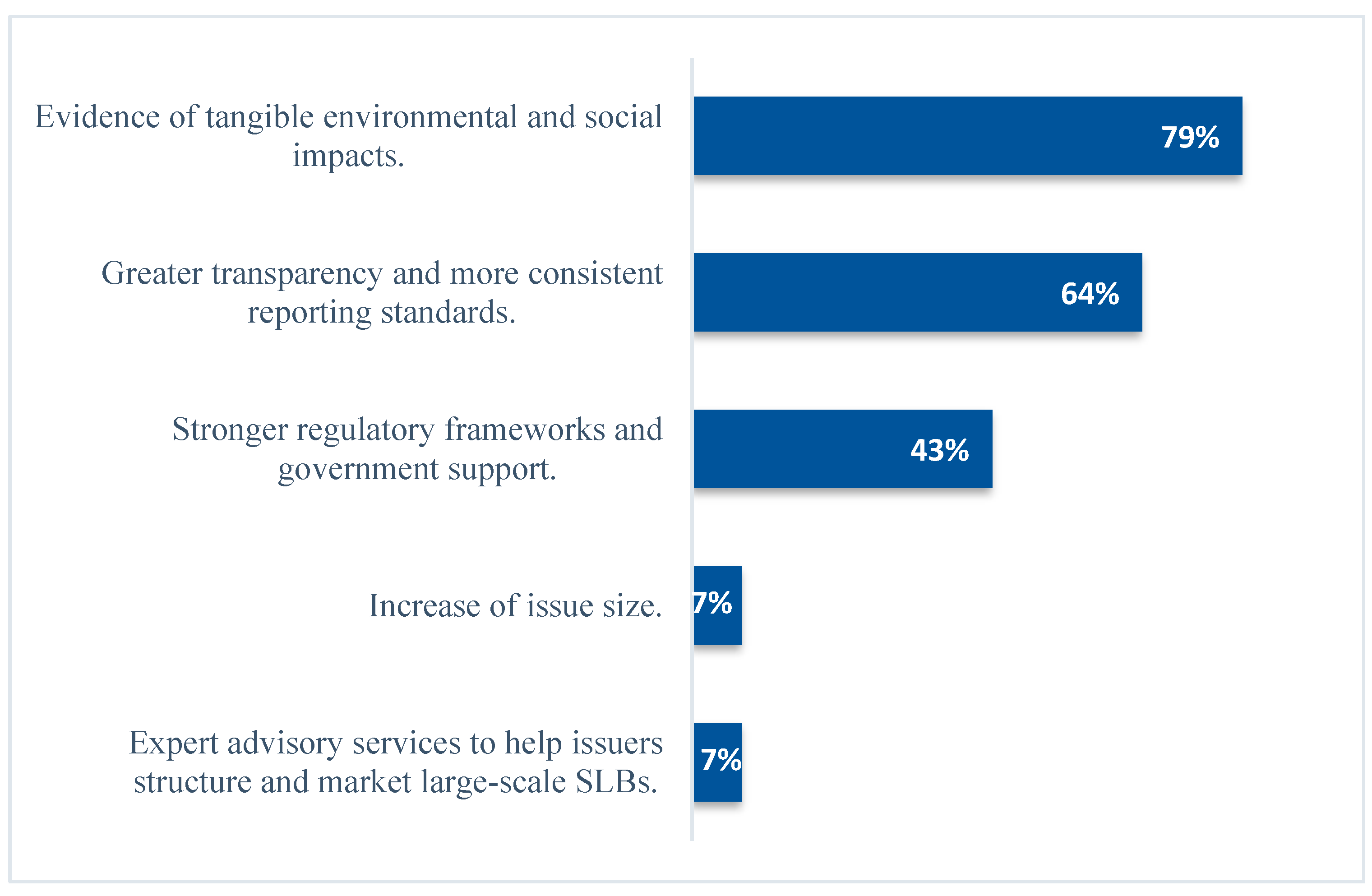

The majority (79%) of respondents note that critical importance of showing “evidence of tangible environmental and social impacts” to increase investor confidence in SLBs, while 64% focus on transparency and disclosure, and 43% focus on the role of regulators [

Figure 21].

Conclusions

SLBs have emerged as a transformative financial instrument, establishing a link between cost of funding and predefined sustainability objectives. Their design can lend credibility to issuers and foster innovation, and the flexibility of its proceeds explain their popularity in hard-to-abate sectors. Initially more prevalent in the private sector, SLBs are gaining ground in sovereign markets. Despite their success, SLBs have encountered skepticism, evidenced by a setback in the market in 2022 relative to other sustainable debt instruments. This juncture marks a crucial turning point, introducing uncertainty about the future trajectory of the SLB market. The maturation of SLBs, coupled with efforts to enhance trust, will shape its trajectory in the financial landscape.

The paper pinpointed limitations in five pivotal areas related to SLBs. First, KPIs may currently lack comparability and materiality. Second, SPTs may not be calibrated based on science, and as such can be less credible. Third, SLB’s characteristics raise questions about how issuers can avoid penalties by calling bonds. Fourth, reporting and verification may not be as regular or detailed as required to instill trust. Finally, SLBs require more monetary and talent resources than plain vanilla bond issuances.

To enhance the design of SLBs and foster market trust, recommendations consist in standardizing KPI selection with a focus on clear logic, comparability, and materiality assessments. Second, a better design includes calibrating SPTs by integrating targets into core strategies, demonstrating material improvement, and incorporating intermediate assessments. Third, bond characteristics should be enhanced through the closure of callable loopholes and contextually tailored step-up mechanisms. Finally, reporting practices should be improved through the utilization of credible and verifiable data sources.

This paper endeavors to facilitate an ongoing dialogue between investors and issuers, providing a platform for the continual development of SLBs, ultimately contributing to a more sustainable and trustworthy financial environment.

References

- Bloomberg, 2022. ESG May Surpass $41 Trillion Assets in 2022, But Not Without Challenges, Finds Bloomberg Intelligence. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/company/press/esg-may-surpass-41-trillion-assets-in-2022-but-not-without-challenges-finds-bloomberg-intelligence/.

- Bosmans, P.; de Mariz, F., 2023. The Blue Bond Market: A Catalyst for Ocean and Water Financing. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2023, 16, 184. [CrossRef]

- Burke, J. February, 2023. Sustainability Linked Bonds: Overview and Disclosure Guidelines. ESGReportingHub. Retrieved from https://www.esgreportinghub.org/article/disclosures-for-sustainability-linked-bonds.

- Cavosoglu, N., Oldani, B., Paris, S., Pamponet Moura, A., & Carillo Sosa, D., n.d.. Three Ways to Protect the Sustainability-Linked Bond Market. IDB Invest. Retrieved from https://idbinvest.org/en/blog/investment-funds/three-ways-protect-sustainability-linked-bond-market.

- Chesné, L. August, 2022. ICMA’s newly released KPI registry to discipline SLB issuances. Natixis. Retrieved from https://gsh.cib.natixis.com/our-center-of-expertise/articles/icma-s-newly-released-kpi-registry-to-discipline-slb-issuances.

- Climate Bonds Initiative, 2022. Sustainable Debt Global State of the market 2022. Retrieved from https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_sotm_2022_03e.pdf.

- Climate Bonds Initiative, 2023a. 101 Sustainable Finance Policies for 1.5 °C. Retrieved from https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_101_policyideas.pdf.

- Climate Bonds Initiative, 2023b. Sustainable Debt Market Summary H1 2023. Retrieved from https://www.climatebonds.net/files/reports/cbi_susdebtsum_h12023_01b.pdf.

- de Mariz, F., 2022. The Promise of Sustainable Finance: Lessons From Brazil. Georgetown Journal of International Affairs 23(2), 185-190. [CrossRef]

- de Mariz, F., 2020. Fintech for Impact: How Can Financial Innovation Advance Inclusion? Included in Global Handbook of Impact Investing: Solving Global Problems Via Smarter Capital Markets Towards A More Sustainable Society, Wiley, Ed. Elsa De Morais Sarmento, R. Paul Herman, ISBN: 978-1-119-69064-1, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3715785.

- de Mariz, F., Savoia, J. R. F., 2018. Chapter 13: Financial innovation with a social purpose: the growth of Social Impact Bonds. In Research Handbook of Investing in the Triple Bottom Line, Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Deschryver, P.; de Mariz, F., 2020. What Future for the Green Bond Market? How Can Policymakers, Companies, and Investors Unlock the Potential of the Green Bond Market? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2020, 13, 61. [CrossRef]

- Enel, 2023. A new framework for even more sustainable finance. Enel. Retrieved from https://www.enel.com/company/stories/articles/2023/02/new-framework-sustainable-finance-group.

- Environmental Finance, n.d.. Sustainability-linked bond of the year: Suzano. Environmental Finance's Bond Awards 2021. Environmental Finance. Retrieved from https://www.environmental-finance.com/content/awards/winners/sustainability-linked-bond-of-the-year-suzano.html.

- Fitch, 2022. Sustainability-Linked Bond Progress Report. Fitch, 1-7. Retrieved from https://www.sustainablefitch.com/fund-asset-managers/sustainability-linked-bond-progress-report-22-09-2022.

- Flammer, C., 2021. Corporate Green Bonds. Journal of Financial Economics Volume 142, Issue 2. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0304405X21000337?casa_token=9azwFVXJnc4AAAAA:A_gsDRcJXgcRbmeiZ57ovP2zk_XeiyTuDL2ls8t_fL-G_OG4dAB-8u_tXVEFBnNptJmR0OOqAWc.

- Glisovic, J., Gonzalez, H., Saltuk, Y., de Mariz, F., 2012. Volume Growth and Valuation Contraction, Global Microfinance Equity Valuation Survey 2012. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2625221. [CrossRef]

- ICMA, 2023a. Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles Voluntary Process Guidelines. ICMA, 2-9. Retrieved from https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2023-updates/Sustainability-Linked-Bond-Principles-June-2023-220623.pdf.

- ICMA, 2023b. Market integrity and greenwashing risks in sustainable finance. ICMA. Retrieved from https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/Market-integrity-and-greenwashing-risks-in-sustainable-finance-October-2023.pdf.

- ICMA, 2022. Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles Related Questions. ICMA. Retrieved from https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/2022-updates/SLB-QA-CLEAN-and-FINAL-for-publication-2022-06-24-280622.pdf.

- ICMA, 2021. Sustainability-Linked Bond Principles Related questions. ICMA. Retrieved from https://www.icmagroup.org/assets/documents/Sustainable-finance/Sustainability-Linked-Bond-Principles-Related-questions-February-2021-170221v3.pdf.

- IFC, 2023. Making Sustainability-Linked Bonds More Impactful. IFC. Retrieved from https://www.ifc.org/en/insights-reports/2023/making-sustainability-linked-bonds-more-impactful.

- ISS Insights. February, 2022. Sustainability-linked Bonds and Loans: Avoiding Greenwash. ISS Insights. Retrieved from https://insights.issgovernance.com/posts/sustainability-linked-bonds-and-loans-avoiding-greenwash/.

- Kölbel, J. F., & Lambillon, A.-P. January 31, 2023. Who pays for sustainability? An analysis of Sustainability Linked Bonds. Swiss Finance Series Research Paper series N°23-07.

- Bruegel, 2023. The potential of sovereign sustainability-linked bonds in the drive for net-zero. Bruegel. Retrieved from https://www.bruegel.org/policy-brief/potential-sovereign-sustainability-linked-bonds-drive-net-zero.

- LSEG (London Stock Exchange Group), August, 2023. Meng, A. Sustainability-linked bonds: a nascent market that is gaining traction. Retrieved from https://www.lseg.com/en/insights/ftse-russell/sustainability-linked-bonds-nascent-market-gaining-traction.

- Mao, Y., 2023. Decoding Corporate Green Bonds: What Issuers Do With the Money and Their Real Impact. SSRN. Retrieved from https://ssrn.com/abstract=4599395 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4599395. [CrossRef]

- Mielnik, S., & Erlandsson, U., 2022. An option pricing approach for sustainability-linked bonds. Anthropocene Fixed Income Institute, 14-19. Retrieved from https://img1.wsimg.com/blobby/go/946d6aac-e6cc-430a-8898-520cf90f5d3e/AFII%20SLB%20option%20pricing%20approach.pdf.

- Pianese, B. October, 2023. Latam innovates on sustainability, but impact assessment is key. The Banker. Retrieved from https://www.thebanker.com/Latam-innovates-on-sustainability-but-impact-assessment-is-key-1696318214.

- Redondo Alamillos, R.; de Mariz, F., 2022. How Can European Regulation on ESG Impact Business Globally? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2022, 15, 291. [CrossRef]

- Hermes Investment, 2022. Do Sustainability-linked bonds have a Step-up problem? Hermes Investment, 2-8. Retrieved from https://www.hermes-investment.com/uploads/2022/04/15b2244e2bdb60da605fa8d00413bd1e/fhi_credit_take-note_sustainability-linked-bonds_march-2022-v2.pdf.

- Ritchi, G., & Tugwell, P., 2022. Global ESG-Linked Bond Market Faces Its First Set of Penalties. Bloomberg. Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-11-17/global-esg-linked-bond-market-faces-its-first-set-of-penalties.

- Segal, M., 2023. Sustainability-Linked Bonds Need to Address Credibility Issues to Resume Growth: S&P. S&P Global. Retrieved from https://www.esgtoday.com/sustainability-linked-bonds-need-to-address-credibility-issues-to-resume-growth-sp/.

- S&P Global, 2021a. Environmental, Social, And Governance: How Sustainability-Linked Debt Has Become A New Asset Class. S&P Global. Retrieved from https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/210428-how-sustainability-linked-debt-has-become-a-new-asset-class-11930349.

- S&P Global, 2021b. The Fear Of Greenwashing May Be Greater Than The Reality Across The Global Financial Markets. S&P Global. Retrieved from https://www.spglobal.com/ratings/en/research/articles/210823-the-fear-of-greenwashing-may-be-greater-than-the-reality-across-the-global-financial-markets-12074863.

- S&P Global, 2023. Higher costs loom for sustainability-linked bonds issuers as deadlines approach. S&P Global. Retrieved December 4, 2023, from https://www.spglobal.com/marketintelligence/en/news-insights/latest-news-headlines/cpil-2709806-article_news_title-textbox-higher-costs-loom-for-sustainability-linked-bond-issuers-as-deadlines-appro-75516523.

- Sustainalytics, 2023. Sustainability-Linked Financial Instruments: Creating Targets and Measuring Your Company's Performance. Sustainalytics. Retrieved from https://www.sustainalytics.com/esg-research/resource/corporate-esg-blog/sustainability-linked-financial-instruments-creating-targets-and-measuring-your-company's-performance.

- The World Bank Group, 2023. Green, Social, and Sustainability (GSS) Bonds Market Update - January 2023. The World Bank. Retrieved from https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/98c3baab0ea4fc3da4de0e528a5c0bed-0340012023/original/GSS-Quarterly-Newsletter-Issue-No-2.pdf.

- The World Bank Group, 2021. Striking the Right Note: Key Performance Indicators for Sovereign Sustainability-Linked Bonds. World Bank Group, 7-61. Retrieved from https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/935681641463424672/pdf/Striking-the-Right-Note-Key-Performance-Indicators-for-Sovereign-Sustainability-Linked-Bonds.pdf.

- United Nations Global Compact, (n.d.). Sustainable Finance: Corporate finance and investments as a catalyst for growth and social impact. Retrieved from https://unglobalcompact.org/sdgs/sustainablefinance.

- Vulturius, G., Maltais, A., & Forsbacka, K., 2022. Sustainability-linked bonds – their potential to promote issuers’ transition to net-zero emissions and future research directions. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment. 14:1, 116-127. [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum, 2022. What are sustainability linked bonds and how can they support the net-zero transition. World Economic Forum. Retrieved from https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/11/cop27-sustainability-linked-bonds-net-zero-transition/.

Figure 1.

Semi-annual issuance of the Labelled Bond Market (in USD billion). Source: Authors, adapted from LSEG 2023.

Figure 1.

Semi-annual issuance of the Labelled Bond Market (in USD billion). Source: Authors, adapted from LSEG 2023.

Figure 2.

SLBs popular in hard-to-abate sectors.Source: Authors, adapted from LSEG 2023.

Figure 2.

SLBs popular in hard-to-abate sectors.Source: Authors, adapted from LSEG 2023.

Figure 3.

Number of KPIs used in SLBs. Source: Authors, adapted from AIFC.

Figure 3.

Number of KPIs used in SLBs. Source: Authors, adapted from AIFC.

Figure 4.

Most commonly used KPIs in SLBs. Source: Authors, adapted from Climate Bonds Initiative (2023b).

Figure 4.

Most commonly used KPIs in SLBs. Source: Authors, adapted from Climate Bonds Initiative (2023b).

Figure 5.

“What are your general impressions about the current state and adoption of Sustainability-Linked Bonds?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 5.

“What are your general impressions about the current state and adoption of Sustainability-Linked Bonds?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 6.

“Where do you see the market for Sustainability-Linked Bonds in the next five to 10 years?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 6.

“Where do you see the market for Sustainability-Linked Bonds in the next five to 10 years?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 7.

“What do you perceive as the main factors that inhibit SLB market growth?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 7.

“What do you perceive as the main factors that inhibit SLB market growth?”. Source: Authors.

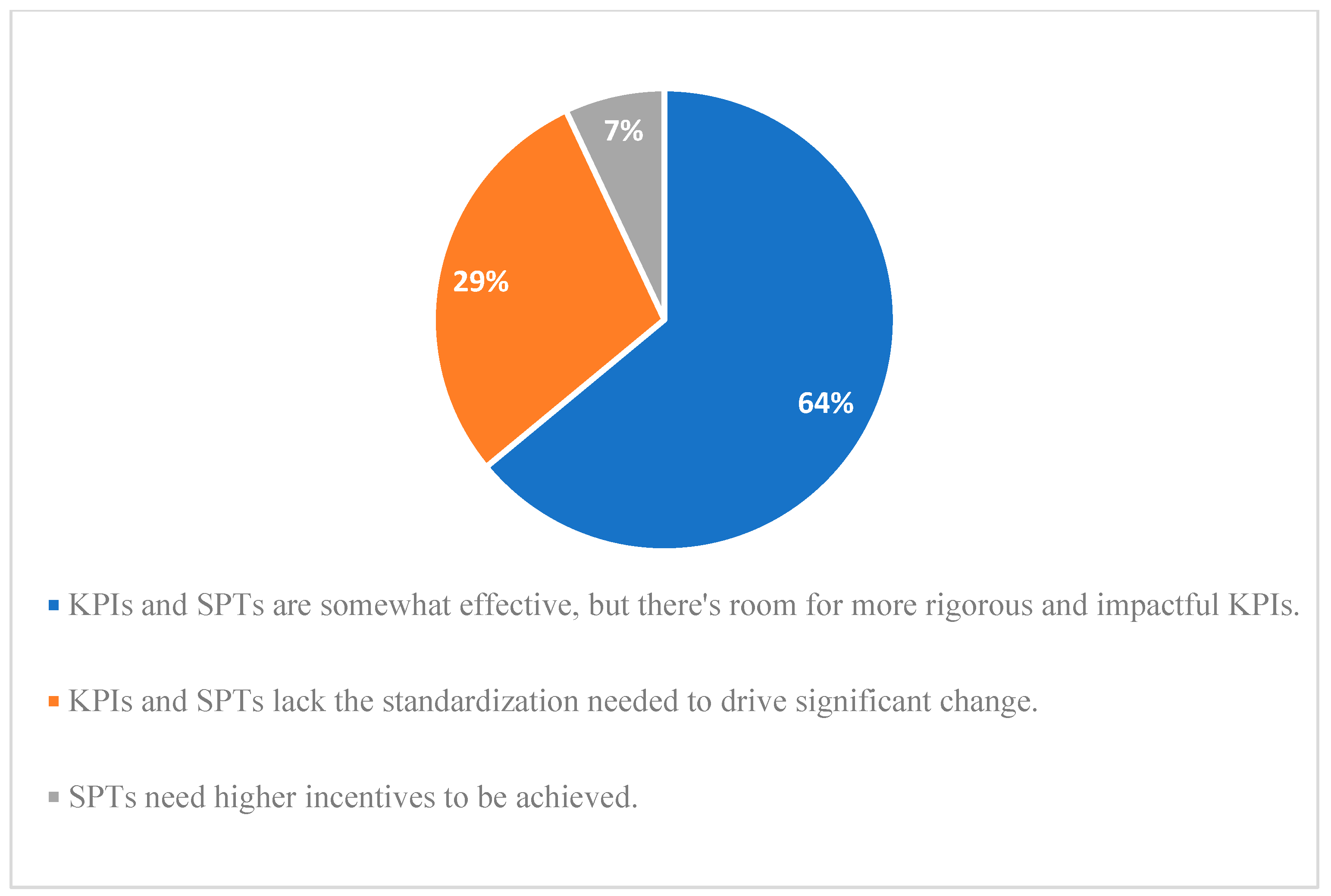

Figure 8.

“How effective are the current SPTs and KPIs in driving social and environmental impact?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 8.

“How effective are the current SPTs and KPIs in driving social and environmental impact?”. Source: Authors.

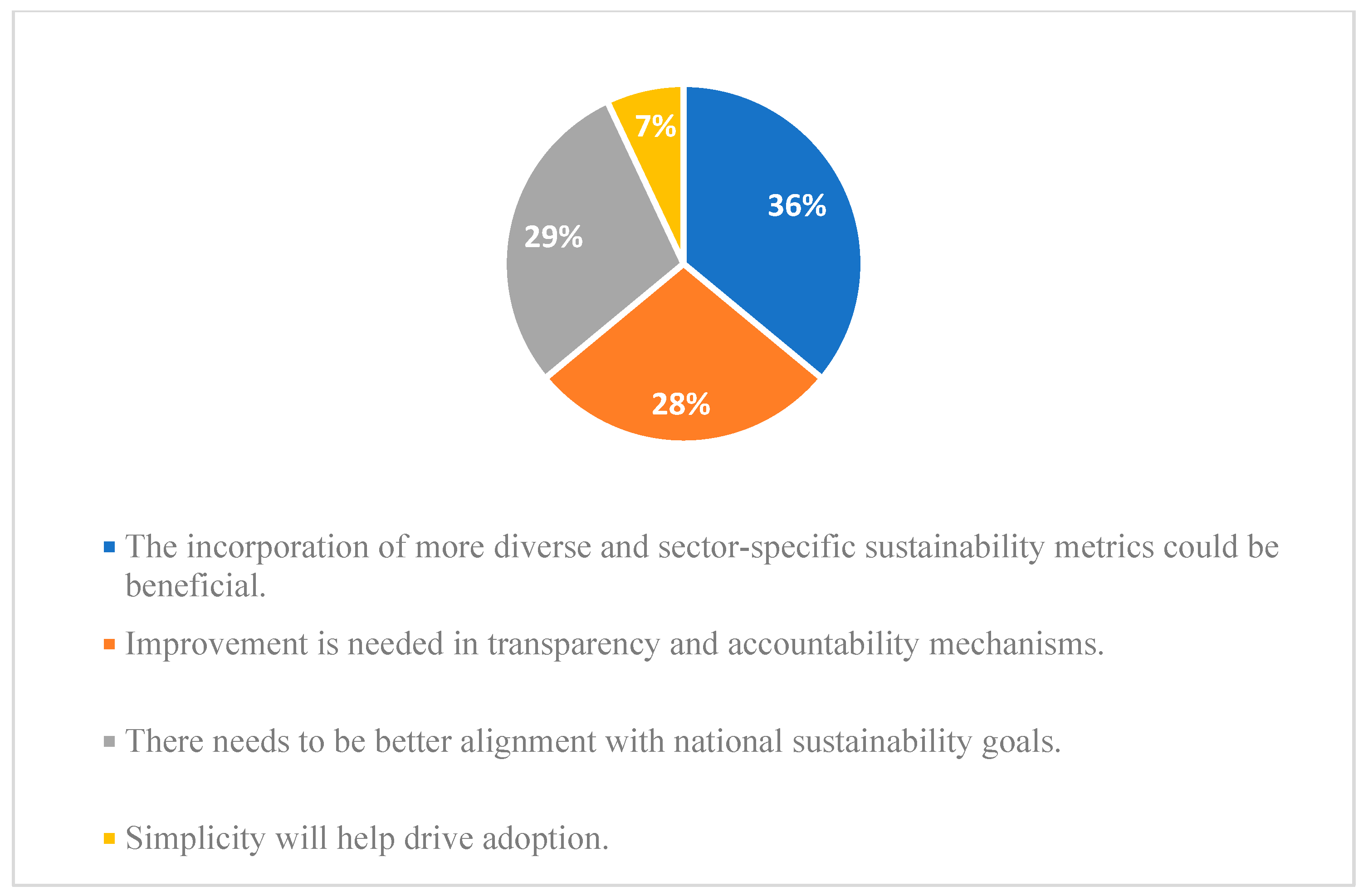

Figure 9.

“Concerning SPTs and KPIs, what areas do you think require improvement in the design of SLBs to enhance their impact?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 9.

“Concerning SPTs and KPIs, what areas do you think require improvement in the design of SLBs to enhance their impact?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 10.

“How can SLBs be designed to better address sustainability-related risks?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 10.

“How can SLBs be designed to better address sustainability-related risks?”. Source: Authors.

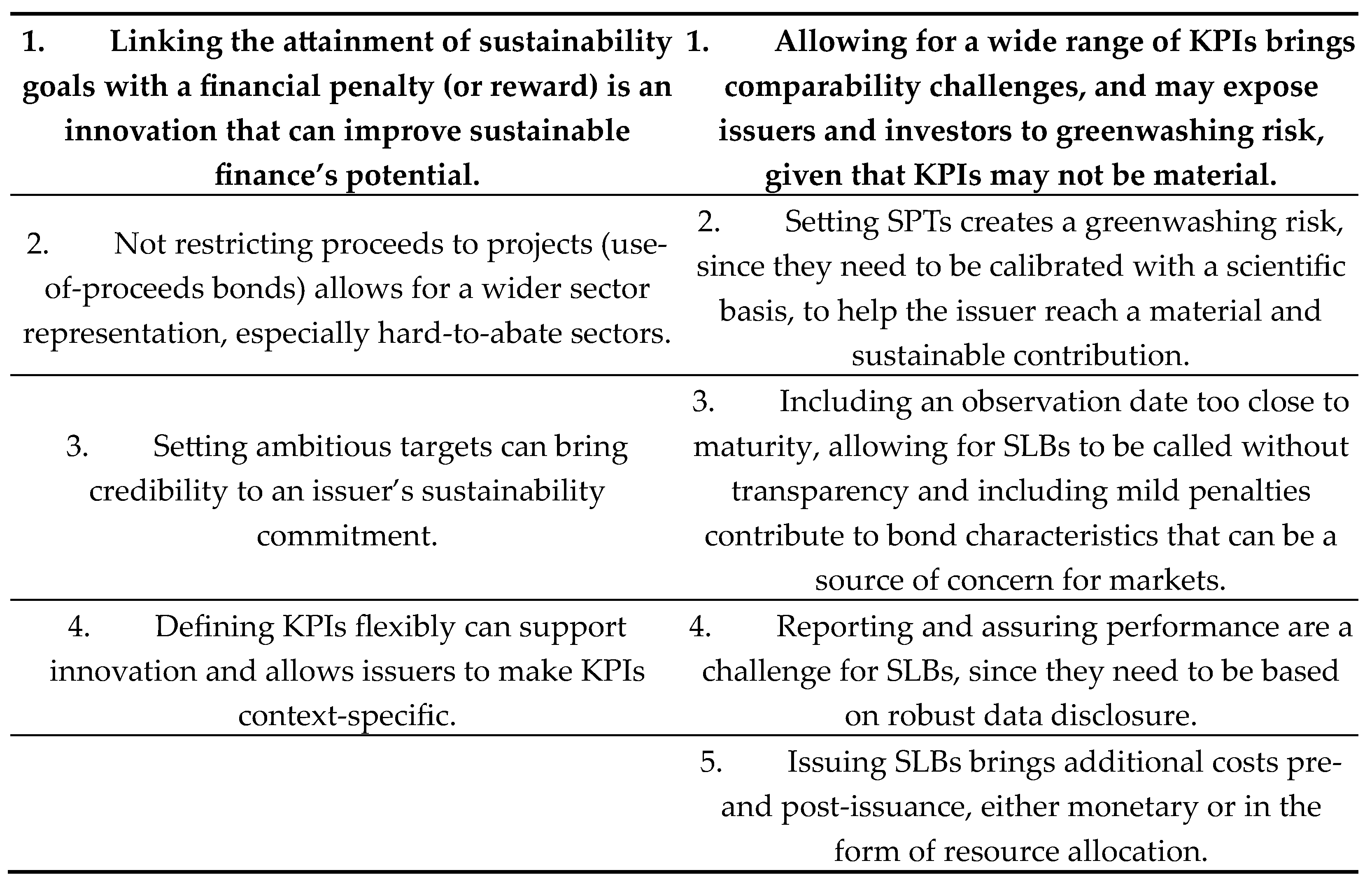

Figure 11.

Key advantages and limitations of SLBs. Source: Authors.

Figure 11.

Key advantages and limitations of SLBs. Source: Authors.

Figure 12.

“How do you think stakeholder could be engaged in the structuring of SLBs?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 12.

“How do you think stakeholder could be engaged in the structuring of SLBs?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 13.

“Should the mechanism for adjusting interest rates in response to missed or reached SPTs be a step-up, step-down, or another mechanism?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 13.

“Should the mechanism for adjusting interest rates in response to missed or reached SPTs be a step-up, step-down, or another mechanism?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 14.

“What are the most relevant criticisms of using a uniform 25bps coupon step-up across different situations, and why?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 14.

“What are the most relevant criticisms of using a uniform 25bps coupon step-up across different situations, and why?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 15.

“What should be the basis for defining a just financial reward/penalty in SLBs?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 15.

“What should be the basis for defining a just financial reward/penalty in SLBs?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 16.

“How should the step-up penalties in SLBs be applied?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 16.

“How should the step-up penalties in SLBs be applied?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 17.

“How can one ensure that issuers do not repurchase bonds early to conceal a miss in SPTs, given the higher likelihood of repurchase in SLBs compared to traditional bonds?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 17.

“How can one ensure that issuers do not repurchase bonds early to conceal a miss in SPTs, given the higher likelihood of repurchase in SLBs compared to traditional bonds?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 18.

“How can transparency and reporting practices be enhanced to boost the credibility of SLBs? “. Source: Authors.

Figure 18.

“How can transparency and reporting practices be enhanced to boost the credibility of SLBs? “. Source: Authors.

Figure 19.

“What kind of incentives could be introduced to encourage more issuers and investors to participate in the SLB market?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 19.

“What kind of incentives could be introduced to encourage more issuers and investors to participate in the SLB market?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 20.

“What role do you see for regulatory bodies in shaping the future of SLBs?”. Source: Author.

Figure 20.

“What role do you see for regulatory bodies in shaping the future of SLBs?”. Source: Author.

Figure 21.

“What are the key factors that, in your opinion, would increase investor confidence in SLBs?”. Source: Authors.

Figure 21.

“What are the key factors that, in your opinion, would increase investor confidence in SLBs?”. Source: Authors.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).