1. Introduction

The presence of porphyrins in myriad biological systems, coupled with the ability to finely tune their chemical and physical properties, position both free base porphyrins and metalloporphyrins as adaptable materials and as crucial for scientific investigations. The deep-rooted biological importance of these tetrapyrrolic macrocycles and their exceptional electronic and structural properties have spurred their widespread utilization, encompassing their use as photosensitizers in photodynamic therapy[

1,

2] and in functionalization reactions[

3,

4], as sensors[

5,

6], in solar cells[

7,

8], and more recently, as organocatalysts[9-13] and as photoredox catalysts[

4,

14,

15]. The availability of a large number of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins in these applications is made possible mainly thanks to the work of Adler and Longo[

16] and of Lindsey[

17,

18], who uncovered simple methods for the preparation of free porphyrins with acceptable yields.

In this last decade, several research groups, including our own, have undertaken a number of investigations on the use of porphyrins and metalloporphyrins as antioxidant and antifungal agents[

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. In this work we report on the synthesis, full spectroscopic characterization, and photophysical studies of a previously unknown free base

meso-tetraarylporphyrin: porphyrin-5,10,15,20-tetrayltetrakis(2-methoxybenzene-4,1-diyl) tetraisonicotinate, H

2TMIPP (

1). The molecular structure of compound

1 was determined by single crystal X-ray diffraction of a

n-hexane monosolvate. The antioxidant, antimicrobial and antifungal properties, as well as the allelopathic potential, of H

2TMIPP (

1) have been examined.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of H2TMIPP (1).

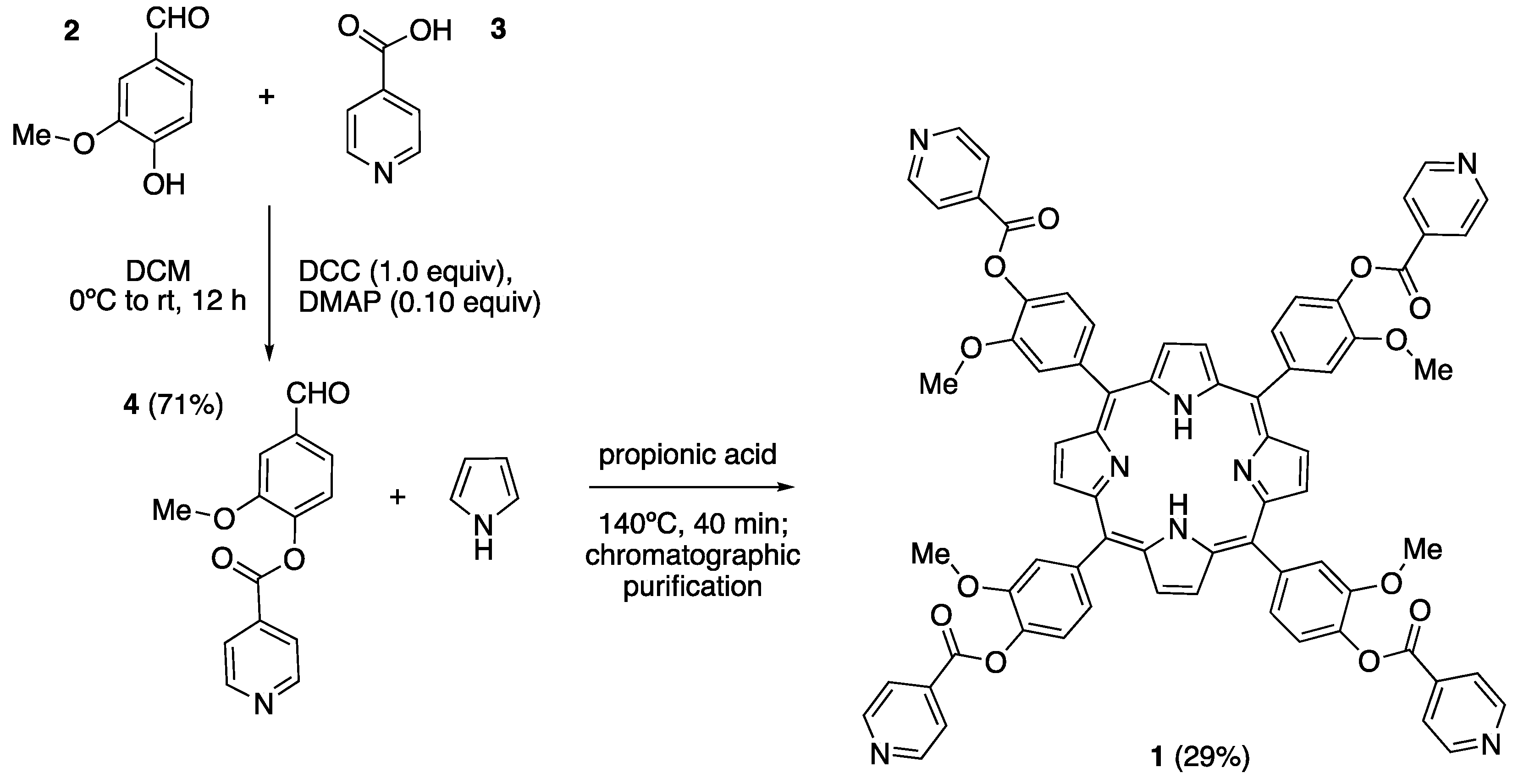

The isonicotinate derived free-base porphyrin

1 was synthesized in two steps from commercially available vainillin (

2) and isonicotinic acid (

3) (

Scheme 1). On the first place, vainillin was directly acylated with isonicotinic acid in dichloromethane solution, using

N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) as a coupling agent in the presence of 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) as a catalyst (10 mol%). In this way, the desired formylisonicotinate

4 was obtained in 71% yield, without need of chromatographic purification, at the multigram scale. This procedure is somewhat more practical than the one described a few years ago by V. I. Potkin and co-workers [

24], that involves the previous preparation of isonicotinoyl chloride hydrochloride. Spectroscopic data for

4 (

1H and

13C NMR, HRMS-ESI) fully coincided with those in the literature [

24]. Condensation of this aldehyde with freshly distilled pyrrole was performed according to the Adler and Longo method (reflux in propionic acid under open air, followed by chromatographic purification; silica gel, DCM/methanol 93:7)[

16], afforded the free base porphyrin

1 in a remarkable 29% yield.

This compound was fully characterized by IR, 1H-NMR, and 13C-NMR spectroscopy, and by HRMS-ESI spectrometry. A detailed discussion of its spectroscopic properties can be found in the Supporting Information.

Recrystallization of 1 from DCM/hexane (diffusion method) afforded a single crystal that was suitable for X-ray diffraction analysis. The molecular structure of 1 showed it had crystallized with a n-hexane solvent molecule, a point that was also confirmed by elemental analysis.

Crystal Data for C

78H

64N

8O

14, H

2TMIPP·C

6H

14 (M = 1305.37 g/mol): monoclinic, space group

P21/c (no. 14), a = 14.9807(16) Å, b = 14.9439(16) Å, c = 14.9053(15) Å, β = 92.393(4)°, V = 3333.9(6) Å3, Z = 2, T = 150(2) K, μ(CuKα) = 0.089 mm

-1, Dcalc = 1.300 g/cm

3, 22628 reflections measured (1.926° ≤ 2Θ ≤ 25.000°), 5858 unique (R

int = 0.0596) which were used in all calculations. The final R

1 was 0,1102 (I > 2σ(I)) and wR

2 was 0.2811(all data) [

25].

A detailed discussion of the molecular structure of the hexane monosolvate of 1 can be found in the Supporting Information.

2.2. Photophysical Properties of H2TMIPP (1).

2.2.1. UV/Vis Spectroscopy

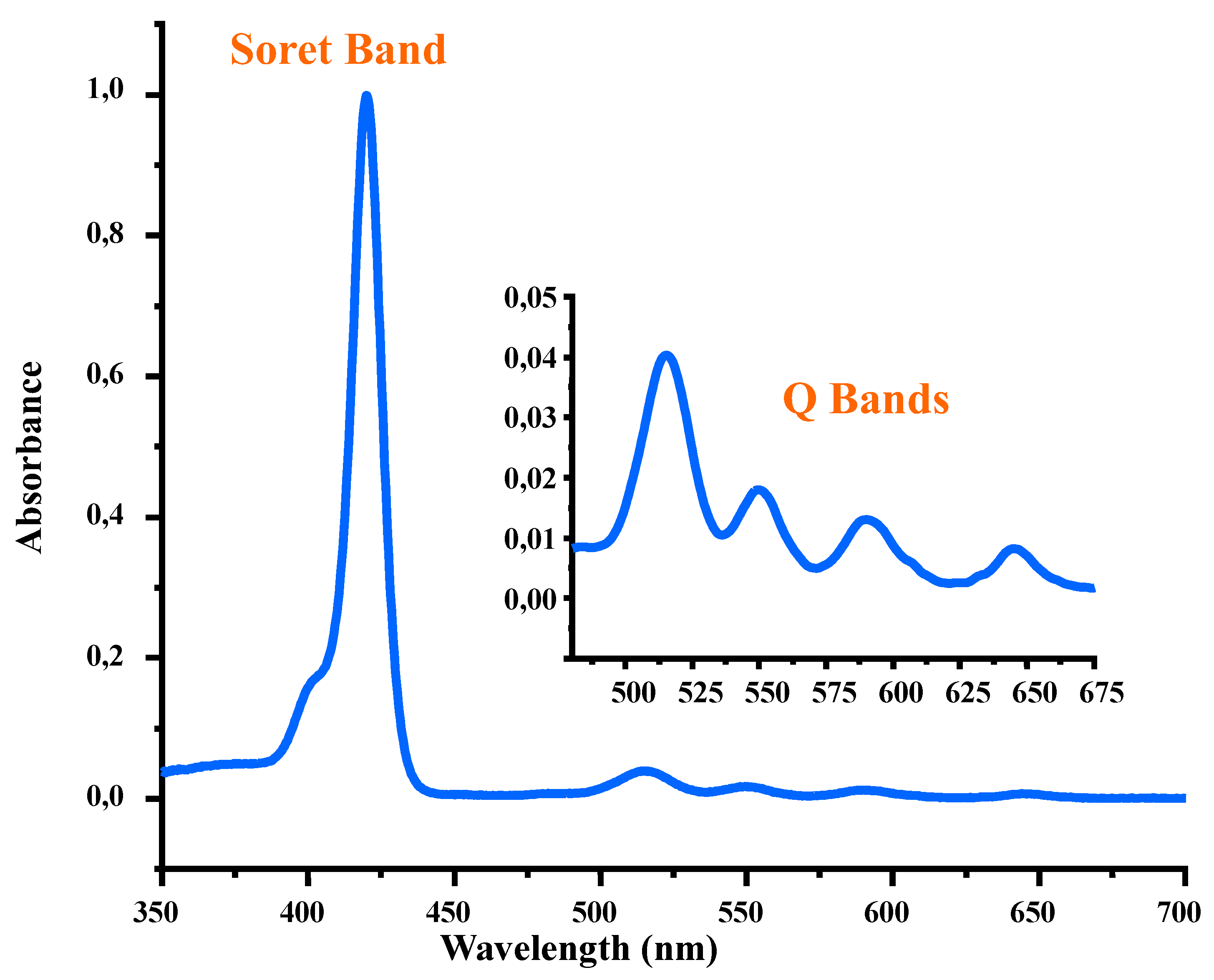

The electronic spectrum of the H

2TMIPP (

1) free base porphyrin in DCM solution is represented in

Figure 1, and the UV/Vis data of this

meso-tetraarylporphyrin, as well as those reported for structurally related compounds, are summarized in

Table 1. The λ

max value of the Soret band of compound

1 is 420 nm and those of the Q bands are 516, 551, 591 and 647 nm, respectively. These values are very close to those of the known

meso-tetraarylporphyrins (

Table 1)[19,26-29] which is an indication that all

meso-tetraarylporphyrins exhibit very similar UV/Vis spectra irrespectively of the nature of the substituents in the

ortho-, meta- or

para- positions of the phenyl rings in these systems.

On the other hand, we determined the optical gap energy (Eg-op) of H

2TMIPP (

1) by means of the Tauc plot method[

30]. The measured value, 1.881 eV, is typical for a free base

meso-tetraarylporphyrin.

2.2.2. Fluorescence Spectroscopy

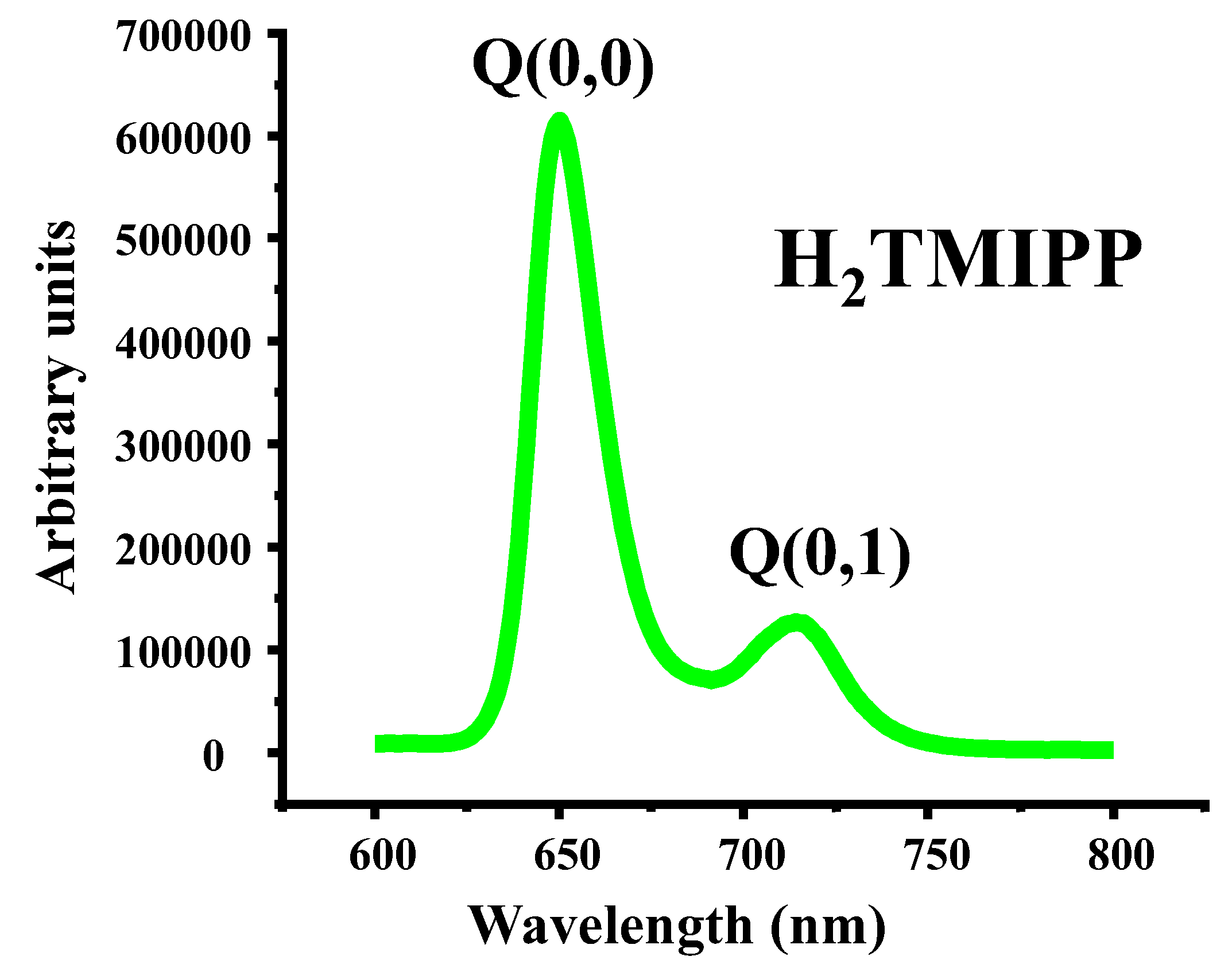

The emission spectrum of compound

1 is depicted in

Figure 2, while in

Table 2 are summarized the emission band maxima (λ

max), the fluorescence quantum yields (φ

f) and lifetime (τ

f ) values of our free base porphyrin (

1), together with those corresponding to a selection of

meso-tetraarylporphyrins.

An inspection of

Table 2 shows that for all

meso-arylporphyrins reported in this Table, including our synthetic free base porphyrin

1, the λ

max values of the Q(0,0) band are around 655 nm while the λ

max values of the Q(0,1) band are close to 716 nm. This is an indication that the positions of the Q(0,0) and Q(0,1) emission bands are independent from the type of the substituent in the

para positions of a

meso-arylporphyrin. Concerning the fluorescence quantum yields (φ

f), the value of the unsubstituted

meso-tetraphenylporphyrin (H

2TPP) is the highest (φ

f = 0.11), while the substituted

meso-tetrarylporphyrins exhibit smaller values of the fluorescence quantum yields. This could be explained by the quenching effect of

para-phenyl substituents of a

meso-arylporphyrin.

2.3. Biological Properties of H2TMIPP (1).

2.3.1. Antioxidant Activity

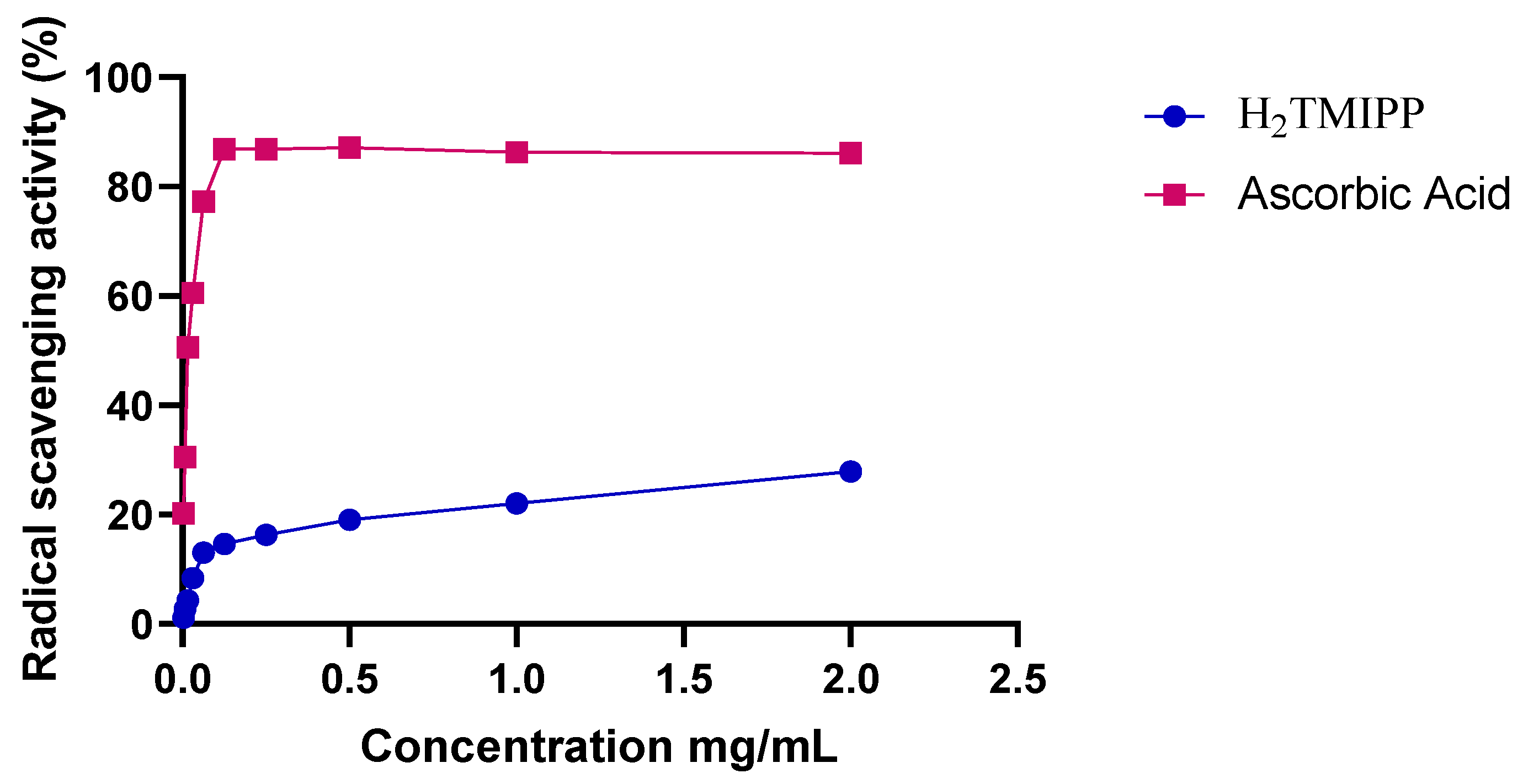

To evaluate the antioxidant properties of the free base porphyrin H

2TMIPP (

1) we used the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical assay. The stable DPPH nitrogen-centered radical exhibits a characteristic absorption pattern that diminishes in the presence of antioxidants [

31]. By reacting with hydrogen-donating functionalities, the color of the DPPH changes from purple to yellow and the intensity of the color change is related to the number of electrons captured[

32].

The radical scavenging activity of H

2TMIPP (

1) and of ascorbic acid against DDPH as a function of the concentration are described in

Figure 3, which shows that the rate of free radical trapping increases with the concentration of the inclusion compound solution. We notice that the porphyrin scavenging performance on DPPH radicals increased very weakly from 27.89% (at 2 mg/mL) to 22.05% (at 1 mg/mL) and 19.07% (at 0.5 mg/mL), with a half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC

50) value of 3.6412 ± 0.4256 mg/mL, compared to 0.01321 ± 0.0062 mg/mL using ascorbic acid (reference). The fact that the H

2TMIPP free base porphyrin exhibits weak antioxidant properties could be explained by the presence of carbonyl groups and the large size of this porphyrin. Indeed, it has been observed that the presence of electron-donating substituents in the phenyl groups of a

meso-arylporphyrin increases its antioxidant activity, while electron-withdrawing substituents decrease it [

33]. Our synthetic porphyrin presents methoxy groups (MeO) which are electron donors and carboxyl groups which have strong affinity of electrons. Therefore, these carbonyl moieties will attract electrons from the methoxy groups and the H

2TMIPP free base porphyrin will behave as an electron withdrawing species leading to the decrease of the antioxidant activity or our synthetic porphyrin.

2.3.2. Antifungal Activity

2.3.2.1. The Disk Diffusion Method

The antifungal activities of the H

2TMIPP (

1) free base porphyrin were quantitatively assessed by the presence or absence of zones of inhibition against three yeast strains (

Candida albicans ATCC 90028,

Candida glabrata ATCC 64677 and

Candida tropicalis ATCC 64677). The diameters of the inhibition zones observed by the disk diffusion method are shown in

Table 3. The solvent used to prepare the porphyrin solution is dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), which showed no inhibition against the test organisms (negative control); Amphotericin B, a commercially available antifungal antibiotic, was used as a reference. The data presented in

Table 3 show that H

2TMIPP

1 gives rise to almost the same pronounced inhibition zones against

C. albicans and

C. tropicalis, where the inhibition zone is 12 ± 0.5 and 12 ± 0.4 mm, respectively, which are different from the effect of the reference drug (Amphotericin B), with an inhibition zone of 20 ± 1 and 20 ± 0.6 mm for the same fungal strains

C. albicans and

C. tropicalis, respectively. However, it is less active against

C. glabrata, with an inhibition zone of 8 ± 0.3 mm. The disk method enabled us to determine whether compound

1 had fungal potential, functioning as a screening for its antifungal activity. Indeed, this porphyrin showed moderate antifungal activity against all three

Candida species. This effect is an indication of the compound's ability to inhibit fungal growth.

2.3.2.2. The Microdilution Method

The study carried out on the antifungal activity of the free porphyrin H

2TMIPP (

1) and Amphotericin B (used as a reference), using the microdilution method, revealed significant results on three yeast strains of the

Candida genus:

Candida albicans, Candida glabrata and

Candida tropicalis. For compound

1, the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) and the minimum fungicidal concentrations (MFCs) varied depending on the strain.

Candida albicans and

Candida tropicalis showed greater sensitivity, with a MIC of 1.25 mg/L and a MFC of 2.5 mg/L, while

Candida glabrata showed greater resistance, with a MIC of 5 mg/L and a MFC greater than 5 mg/L. These results suggest a variable efficacy of our isonicotinate-derived porphyrin depending on the strain (

Table 4). For Amphotericin B, the results indicate satisfactory antifungal activity, although slightly higher concentrations are required for

Candida glabrata. These significant antifungal activities observed for our compound

1 may be due to the presence of the NH group in the porphyrin core of H

2TMIPP, which plays an important role in the antimicrobial activity. In addition, this

meso-tetraarylporphyrin skeleton also contains the phenyl isonicotinate moiety, which may also be responsible for the higher antifungal activity of this porphyrin.

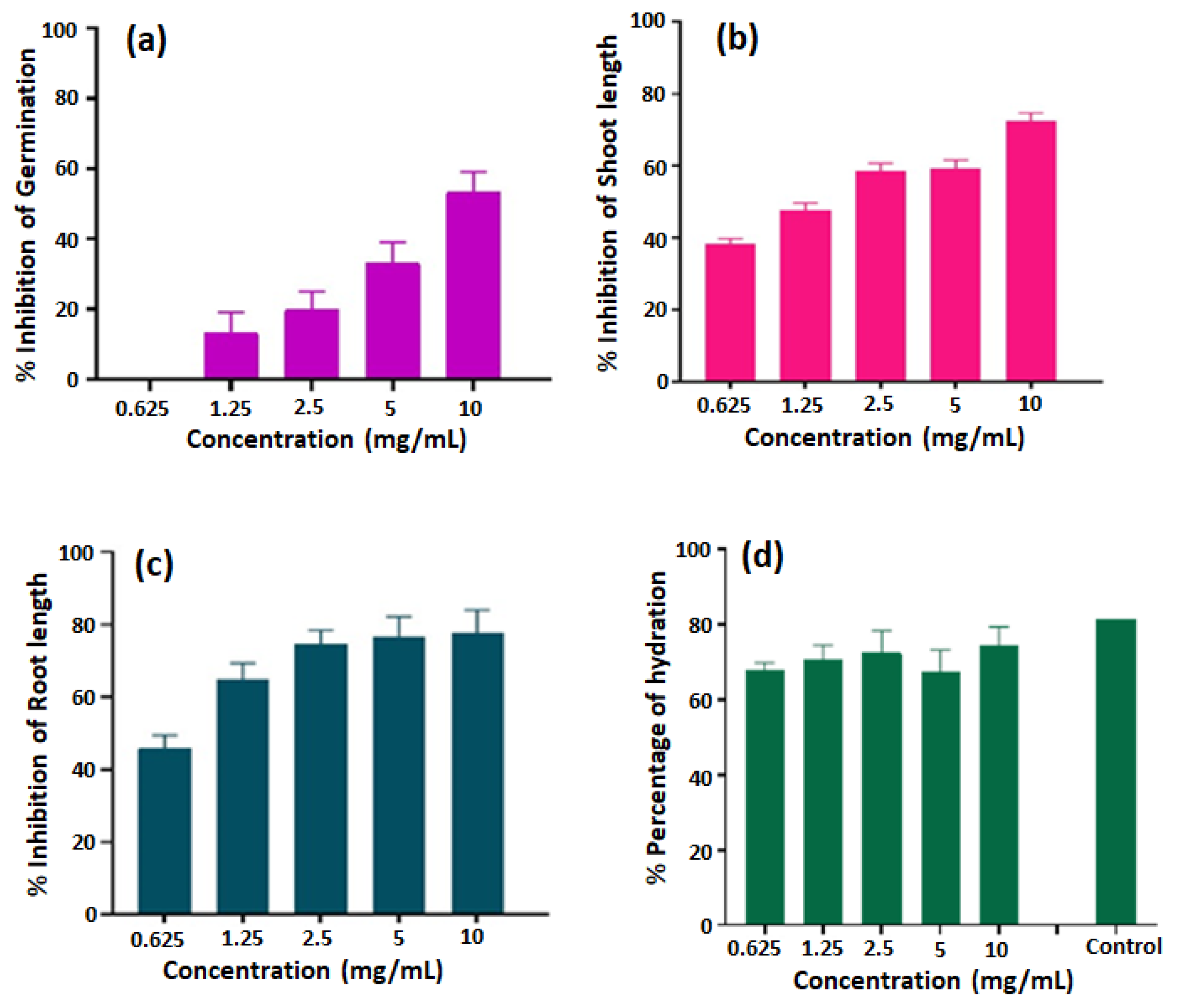

2.3.3. Allelopathic Activity

Figure 4 shows the effects of different concentrations of the free base porphyrin H

2TMIPP (

1) on the germination, above ground growth, root growth, and hydration of lentil seeds. Firstly, regarding the germination (%G) (

Figure 4-a), no inhibition is observed at a 0.625 mg/mL concentration, but from the 1.25 mg/mL concentration onwards, a progressive inhibition is observed, reaching 50% at a concentration of 10 mg/mL. This indicates that H

2TMIPP has a significant impact on lentil seed germination. Concerning the growth of the aerial part, even at a concentration of 0.625 mg/mL, a significant inhibition of 37.94% was observed, and this inhibition increases linearly with the increase in the concentration of H

2TMIPP. At a concentration of 10 mg/mL, inhibition reached 71.7% (

Figure 4-c), underlining the major impact on the growth of the aerial part of the seedlings. Similarly, root growth (

Figure 4-b) showed an increase in inhibition as the concentration of free base porphyrin

1 increased. At a concentration of 10 mg/mL, inhibition reached 74.13%, highlighting a significant impact on seedling root development. In terms of hydration (%H) of the seedlings (

Figure 4-d), the percentage of hydration ranged from 66.87% to 71.37%. This indicates that porphyrin

1 negatively affects the hydration capacity of lentil seedlings.

These results clearly reveal the allelopathic potential of H2TMIPP, suggesting that it acts as a growth-inhibiting agent in lentil seeds. As porphyrins are naturally present in plants chlorophyll, these results raise important questions about their potential role as allelopathic agents in nature. It is possible that porphyrins play a role in inter-species competition by influencing the growth of neighboring plants, which could have implications for understanding the mechanisms of interaction between plants within ecosystems.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods

Commercially available reagents, catalysts, and solvents were used as received from the supplier. Dichloromethane for porphyrin synthesis was distilled from CaH2 prior to use, and THF was dried by distillation from LiAlH4. Deuterated solvents were supplied by Merck Life Science.

Thin-layer chromatography was carried out on silica gel plates Merck 60 F254, and compounds were visualized by irradiation with UV light and/or and chemical developers (KMnO4, p-anisaldehyde, and phosphomolybdic acid). Chromatographic purifications were performed under pressurized air in a column with silica gel Merck 60 (particle size: 0.040–0.063 mm, Merck Life Science S.L.U., Spain) as stationary phase and solvent mixtures (hexane, ethyl acetate, dichloromethane, and methanol) as eluents.

1H (400 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded with a Varian Mercury 400 spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, Cal, USA). Chemical shifts (δ) are provided in ppm relative to the peak of tetramethylsilane (δ = 0.00 ppm), and coupling constants (J) are provided in Hz. The spectra were recorded at room temperature. Data are reported as follows: s, singlet; d, doublet; t, triplet; q, quartet; m, multiplet; br, broad signal. IR spectra were obtained with a Nicolet 6700 FTIR instrument (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Mass., USA), using ATR techniques. UV–vis spectra were recorded on a double-beam Cary 500-scan spectrophotometer (Varian); cuvettes (quartz QS Suprasil, Hellma, Hellma GmbH & Co. KG, Mülheim, Germany) cm were used for measuring the absorption spectra. The porphyrin solutions in water were carefully degassed by gentle bubbling a nitrogen gas stream prior to the spectrophotometric measurement.

3.2. Synthetic Procedures and Product Characterization

3.2.1. Synthesis of 4-formyl-2-Methoxyphenyl Isonicotinate 4

Isonicotinic acid

3 (6.03 g, 0.049 mol), 4-hydroxy-3-methoxybenzaldehyde

2 (7.45 g, 0.049 mol), and 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP) (0.6g, 0.0049 mol) were dissolved in dry dichloromethane (40 mL) at 0 °C. To this solution, a solution of

N,

N′-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) (10.11 g, 0.049 mol) in dry dichloromethane (25 mL) was added dropwise; when the addition was finished, and the mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h. Upon completion of the reaction, the resulting mixture was filtered, and the dichloromethane was removed by rotary evaporation. The residue was poured over water, and the solid was collected by filtration, washed with water, followed by

n-hexane, and dried under vacuum to afford a pale-yellow powder (9.0 g, yield 71.4%), whose spectral data coincided with those described in the literature[

24].

1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz): δ = 10.0 (s, 1H), 8.88 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.7 Hz, 2H), 8.01 (dd, J = 4.4, 1.6 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (dd, J = 3.4, 1.7 Hz, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 1,8 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H) 3.90 (s, 3H) ppm. 13C NMR (CDCl3, 151 MHz): δ = 190.89 (CO of CHO), 162.73 (CO of ester), 151.89, 150.86(x2), 144.51, 138.26, 136.08, 135.62, 124.68, 123.31(x2), 110.98, 56.14 (C–O of methoxy) ppm. HRMS [ESI+]: m/z calcd for C14H12NO4 [M+H] +: 258.0761 found: 258.0769.

3.2.2. Synthesis of Porphyrin-5,10,15,20-Tetrayltetrakis(2-Methoxybenzene-4,1-diyl) Tetraisonicotinate 1

H

2TMIPP (

1) was prepared by means of the Adler and Longo method[

16]. In a 250 mL three-necked flask, 4-formyl-2-methoxyphenyl isonicotinate

4 (3.72 g, 14.4 mmol) was dissolved in propionic acid (50 mL), and the open-air solution was heated under reflux at 140°C. Freshly distilled pyrrole (1.0 mL, 14.5 mmol) was then added dropwise, and the resulting mixture was stirred under reflux for another 40 min. The mixture was cooled down at room temperature. Propionic acid was distilled under vacuum and the obtained solid was dissolved in 20 mL of dichloromethane and then neutralized with a 1 M aqueous solution of ammonia. After decantation, the organic phase was concentrated, and the residue was purified by column chromatography on silica gel (dichloromethane /methanol 93/7 as eluent). A purple solid was obtained, that was dried under vacuum overnight (1.26 g, 29% yield). The single crystal X-ray molecular structure of compound

1, recrystallized from hexane/DCM, shows that it co-crystallizes with a

n-hexane solvent molecule.

FTIR (solid, = 3316 ν(NH) (porphyrin), 2960 ν(CH) (porphyrin),1736 ν(C=O) (ester), 1263–1063,ν(C–O) (ester), 967 δ(CCH) (porphyrin). 1H NMR (CDCl3 , 400 MHz) δ (ppm): 9.0 (s, 8H, H-pyrrole), 8.97 (dd, J1 = 4.4 Hz, J2= 1.6 Hz, 8H Ar), 8.21 (dd, J1 = 4.4Hz, J2 = 1.6 Hz, 8H Ar), 7.92 (s, 4H Ar), 7.89 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H Ar), 7.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 4H Ar), 3.95 (s, 12H, 4H-OCH3 ), -2.77 (s, 2H, NH). 13C NMR (151 MHz, CDCl3) δ (ppm): 163.51, 150.87(x2), 151.5, 149.2, 141.22, 139.5, 136.77, 127.21, 123.51(x2), 121.0, 120.5, 119.3, 119.2, 56.23 ppm. HRMS [ESI+]: m/z calcd for C72H51N8O12 [M+H]+: 1219.3621 found: 1219.3617 (-0.39 ppm). UV/Vis [λmax (nm) in CH2Cl2, (log ε)]: 420 (5.73), 516 (4.33), 551 (3.97), 591 (3.87), 647 (3.68). Elemental analysis calcd (%) for C78H64N8O16 [H2TMIPPC6H14]: C 71.77, H 4.79, N 8.58; found: C 72.02, H 4.93, N 8.89.

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

The 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) scavenging activity was determined according to the method described by Hrichi

et al.[

34], with minor modifications. Both for synthetic H

2TMIPP (

1) free base porphyrin and for ascorbic acid (used as a standard), a series of dilutions were performed in ethanol to obtain 10 different concentrations, ranging from 2.00 to 0.0039 mg/mL

-1. One hundred microliter of a 0.1 mM solution of DPPH in ethanol was added to 100 µL of each concentration placed in a 96-well microplate. The mixture was shaken gently rpm and incubated in the dark for 30 minutes. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 517 nm using a microplate spectrophotometer (Multiscan FC, thermo-scientific). Ethanol was used as a reagent blank in place of the sample, the control being a DPPH/ethanol (v/v) mixture. Trials were carried out in triplicate.

The percentage of free radical scavenging by the test samples was calculated using the equation

(1):

where,

Acontrol represents the absorbance of the control sample and

Asample represents the absorbance of the sample under test. The IC

50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) value was determined as the concentration at which each sample exhibits 50% radical scavenging activity.

3.4. Antifungal Activity

Fungal strain and culture conditions:

The in vitro antifungal activities of H2TMIPP (1) and of Amphotericin B, a commercially available antifungal antibiotic used as a reference, were tested against three human yeast strains belonging to the Candida (C.) genus, obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, specifically C. albicans (ATCC 90028), C. glabrata (ATCC 64677), and C. tropicalis (ATCC 66029). Before conducting each antifungal test, these fungal strains were subcultured on Sabouraud dextrose Chloramphenicol plates (Biolife).

Disk Diffusion Method:

A two hundred micro-liter suspension of Candida spp. containing 0.5 McFarland was uniformly dispersed on the MH (Muller Hinton Agar) medium. Six-millimeter diameter paper disc was impregnated with 10 µl of 100 µg/ml porphyrin solutions, dried and placed on the MH medium previously inoculated with the Candida spp. culture. The medium was incubated at 37 °C for 24 hours and the inhibition activity was measured using the mean diameter of the inhibition zone. Standard Amphotericin B disc was used as positive control for antifungal activity.

Determination of Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) and Minimum Fungicidal Concentration (MFC)

The micro dilution technique was used to determine the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of the free base porphyrin on

Candida spp. strains according to a modified Hrichi

et al. [

35] method. Firstly, solutions of H

2TMIPP dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (w/v) were prepared and then diluted in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 2% glucose. Then, each well, 100 μL of each porphyrinic solution was dispensed at concentrations between 5 and 0.039 mg.mL

-1. Next, 90 μL of suspension adjusted to 1-2.5 x 105 CFU mL

-1 in RPMI 1640-2% glucose was added to each well. Finally, 10 μL of resazurin indicator solution (0.37g.mL

-1) was added to reach a final volume of 200 μL per well. A negative control was obtained by adding 200 μL of RPMI 1640-2% glucose to a well and a positive control by adding 100 μL of RPMI 1640-2% glucose and 100 μL of inoculum. The microplates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. For each strain tested, three replicates were performed. The MIC was considered to be the lowest concentration of porphyrinic solution at which each candida spp did not grow. To determine the FMC, 10 μL of each concentration after the concentration corresponding to the MIC was subcultured onto Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) plates and incubated at 37 °C for 72 h. As a result, the MFC was defined as the H

2TMIPP concentration that gave rise to no visible colonies or revealed three or fewer colonies, providing approximately 99-99.5% growth inhibition.

3.5. Allelopathic Activity of H2TIMPP

The allelopathic activity of the H

2TIMPP free base porphyrin was tested

in vitro, using seeds of the model plant lens culinaris Medik (lentils), according to the method described by Hrichi

et al. [

34]. Five concentrations (5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625 and 0.3125 mg.mL

-1) of each porphyrin dissolved in methanol were prepared and added to 9.0 cm diameter Petri dishes. Control tests were carried out using distilled water. After evaporation of the solvent, 10 seeds and 5 mL of distilled water were placed on the filter paper disc, thus maintaining the initial concentration. All tests were carried out in triplicate. The Petri dishes were left in ambient temperature, light, and humidity conditions in the laboratory. The data relating to seed germination, shoot length, root length and hydration were recorded after 7 days of sowing. We counted the number of germinated seeds and then determined the germination percentage using equation (2):

where NGS is the number of germinated seeds and TNS is the total number of seeds.

Germination inhibition percentages were calculated using equation (3):

The plants were carefully sampled, and the lengths of the radicles and hypocotyls were measured with a ruler and expressed in centimeters (cm). Percent elongation was determined using equation (4):

where

E is the value of the parameter studied (length of aerial part, length of root part) in the presence of the extract and

T is the value of the parameter studied (length of aerial part, length of root part) in the presence of the control (distilled water).

The fresh mass was determined by weighing the plants on an analytical balance. The plants were then dried in a forced-air oven at 60 °C for 24 hours and weighed again to obtain the dry mass.

The percentage hydration was calculated using equation (5):

where

PF is the fresh sample weight and

PS is the dry sample weight. The percentage of hydration inhibition was calculated according to equation (6):

For the % I > 0, there is inhibition and for the % I < 0, there is stimulation.

3.6. X-ray Diffraction

A dark blue prism shaped single crystal of compound

1 (co-crystal with

n-hexane) was used for an X-ray diffraction investigation. The data were collected at 150(2) K on a D8 VENTURE Bruker AXS diffractometer using Mo Kα radiation of wavelength 0.71073 Å. The SADABS program (Bruker AXS 2014) [

36] was used for the absorption correction. The SIR-2014 program was used to solve the structure of compound

1 [

37] and the SHELXL-2014 program [

38] was used to refine this structure by full-matrix least-squares techniques on F

2. During the refinements, we noticed that one arm of the porphyrin made by a phenyl, an ester, a methoxy and a pyridyl groups is disordered in two positions [(C31A-C32A-C33A-C24A-C35A-C36A-O37A-C38A-O39A-C40A-O41A-C42A-C43A-C44A-N45A-C46A-C47A) and (C31B-C32B-C33B-C24B-C35B-C36B-O37B-C38B-O39B-C40B-O41B-C42B-C43B-C44B-N45B-C46B-C47B)] with refined position occupancies of 0.590 (6) and 0.410 (6), respectively. Furthermore, the

n-hexane molecule is disordered over three positions [C48A-C49A-C50A) (C48B-C49B-C50B) and (C51-C52-C53)] with refined position occupancies of 0.236 (3), 0.265 (3) and 0.499 (3), respectively. For these two disordered moieties, the anisotropic displacement ellipsoids of the disordered atoms are very elongated, which indicates that they are statistically disordered. Consequently, for the disordered phenyl, the SIMU and PLAT restraints commands in the SHELXL-2014 software were used[

39]. The DFIX and DANG constraint commands were also used to correct the geometry of these disordered fragments[

39].

For compound

1 non-hydrogen atoms were refined with anisotropic thermal parameters whereas H-atoms were included at estimated positions using a riding model. Drawings were made using ORTEP3 for windows[

40] and MERCURY[

41].

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, we have successfully prepared a new meso-tetraarylporphyrin, namely the porphyrin-5,10,15,20-tetrayltetrakis(2-methoxybenzene-4,1-diyl) tetraisonicotinate H2TMIPP (1). The spectroscopic properties of this free base porphyrin were studied by 1H and 13C NMR, IR, UV/Vis, and fluorescence. The structure of this porphyrinic species was elicited by high-resolution ESI Mass spectrometry and by single crystal X-ray diffraction. DDPH was used to test the scavenging activity of H2TMIPP against three yeast strains (C. albicans ATCC 90028, C. glabrata ATCC 64677 and C. tropicalis ATCC 64677); this compound shows rather weak antioxidant properties compared to ascorbic acid, used as a reference. This free base porphyrin (using both the disk diffusion and the microdilution methods) showed moderate but encouraging antifungal against the same three yeast strains, activity compared to that of Amphotericin B, used as reference. The allelopathic properties of H2TMIPP were also studied on the germination, above ground growth, root growth and hydration of lentil seeds. This investigation led to the following results: (i) concerning the germination, at a H2TIMM concentration of 10 mg/mL, we got an inhibition percentage is 50%, (ii) with regard to the growth of the aerial part, for a concentration of 10 mg/mL of H2TMIM, the inhibition reached 71.7%, (iii) for the root growth of lentil seeds, for the same 10 mg/mL concentration of H2TMIPP, inhibition reached 74.13% and (iv) in terms of hydration (%H) of the seedlings, the hydration percentage is between 66.87 and 74.13%. Therefore, this new free base meso-tetraarylporphyrin exhibits very interesting allelopathic properties on lentil seeds.

Supplementary Materials

he following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Spectroscopic data for aldehyde 4 (Figures S1–S3); spectroscopic data for porphyrin 1 (Figures S4–S8); Crystal structure description of porphyrin 1 (Tables S1–S3, Figures S9–S13).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Albert Moyano and Habib Nasri; Formal analysis, Nour Elhouda Dardouri, Soukhayna Hrichi, Raja Chaâbane-Banaoues, Ilona Turowska-Tyrk, Thierry Roisnel and Hamouda Baba; Funding acquisition, Albert Moyano; Investigation, Nour Elhouda Dardouri, Pol Torres, Alessandro Sorrenti and Hamouda Baba; Methodology, Albert Moyano and Habib Nasri; Project administration, Albert Moyano; Supervision, Joaquim Crusats and Albert Moyano; Writing – original draft, Habib Nasri; Writing – review & editing, Joaquim Crusats and Albert Moyano. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FEDER, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación (MCIN), Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI): MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and ERDF funds (grant number PID2020-116846GB-C21, to AM).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

The administrative and technical support of the CCTiUB is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, J.-J.; Hong, G.; Gao, L.-J.; Liu, T.-J.; Cao, W.-J. In vitro and in vivo antitumor activity of a novel porphyrin-based photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy, J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2015, 141, 1553–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rostami, M.; Rafiee, L.; Hassanzadeh, F.; Dadrass, A.R.; Khodarahmi, G.A. Synthesis of some new porphyrins and their metalloderivatives as potential sensitizers in photo-dynamic therapy. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 10, 504–513. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Campestrini, S.; Tonellato, U. Photoinitiated Olefin Epoxidation with Molecular Oxygen, Sensitized by Free Base Porphyrins and Promoted by Hexacarbonylmolybdenum in Homogeneous Solution. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2002, 3827–3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa e Silva, R.; da Silva, L.O.; Bartolomeu, A. A.; Brocksom, T. J.; de Oliveira, K. T. Recent applications of porphyrins as photocatalysts in organic synthesis: batch and continuous flow approaches. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2020, 16, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norvaiša, K.; Kielmann, M.; Senge, M.O. Porphyrins as Colorimetric and Photometric Biosensors in Modern Bioanalytical Systems. ChemBioChem 2020, 21, 1793–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes, F.O.; Maia, L.B.; Cordas, C.; Delerue-Matos, C.; Moura, I.; Moura, J.J.G.; Morais, S. Nitric Oxide Detection Using Electrochemical Third-generation Biosensors – Based on Heme Proteins and Porphyrins. Electroanalysis 2018, 30, 2485–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, F.; Wu, J.; Lin, Z.; Wu, H.; Peng, X. A free base porphyrin as an effective modifier of the cathode interlayer for organic solar cells. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 635, 157720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brogdon, P.; Cheema, H.; Delcamp, J.H. Near-Infrared-Absorbing Metal-Free Organic, Porphyrin, and Phthalocyanine Sensitizers for Panchromatic Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. ChemSusChem 2018, 11, 86–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roucan, M.; Kielmann, M.; Connon, S.J.; Bernhard, S.S.R.; Senge, M.O. Conformational control of nonplanar free base porphyrins: towards bifunctional catalysts of tunable basicity. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 26–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlegui, A.; El-Hachemi, Z.; Crusats, J.; Moyano, A. 5-Phenyl-10,15,20-Tris(4-sulfonatophenyl)porphyrin: Synthesis, Catalysis, and Structural Studies. Molecules 2018, 23, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlegui, A.; Soler, B.; Galindo, A.; Orteaga, O.; Canillas, A.; Ribó, J.M.; El-Hachemi, Z.; Crusats, J.; Moyano, A. Spontaneous mirror-symmetry breaking coupled to top-bottom chirality transfer: From porphyrin self-assembly to scalemic Diels–Alder adducts. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 12219–12222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arlegui, A.; Torres, P.; Cuesta, V.; Crusats, J.; Moyano, A. A pH-Switchable Aqueous Organocatalysis with Amphiphilic Secondary Amine–Porphyrin Hybrids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 4399–4407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arlegui, A.; Torres, P.; Cuesta, V.; Crusats, J.; Moyano, A. Chiral Amphiphilic Secondary Amine-Porphyrin Hybrids for Aqueous Organocatalysis. Molecules 2020, 25, 3420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybicka-Jasinska, K.; Shan, W.; Zawada, K.; Kadish, K. M.; Gryko, D. Porphyrins as Photoredox Catalysts: Experimental and Theoretical Studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 15451–15458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres, P.; Guillén, M.; Escribà, M.; Crusats, J.; Moyano, A. Synthesis of New Amino-Functionalized Porphyrins: Preliminary Study of Their Organophotocatalytic Activity. Molecules 2023, 28, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, A.D.; Longo, F.R.; Finarelli, J.D.; Goldmacher, J.; Assour, J.; Korsakoff, L. A simplified synthesis for meso-tetraphenylporphine. J. Org. Chem. 1967, 32, 476–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.W.; Lawrence, D.S.; Lindsey, J.S. An improved synthesis of tetramesitylporphyrin. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987, 28, 3069–3070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, J.S.; Prathapan, S.; Johnson, T.E.; Wagner, R. W. Porphyrin Building Blocks for Modular Construction of Bioorganic Model Systems. Tetrahedron 1994, 50, 8941–8968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, N.; Taheur, F.B.; Chevreux, S.; Rodrigues, C.M.; Dorcet, V.; Lemercier, G.; Nasri, H. Syntheses, crystal structures, photo-physical properties, antioxidant and antifungal activities of Mg(II) 4,4′-bipyridine and Mg(II) pyrazine complexes of the 5,10,15,20 tetrakis(4–bromophenyl)porphyrin. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2021, 525, 120466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, B.; Peksel, A.; Avciata, U.; Gül, A. Radical scavenging and in vitro antifungal activities of Cu(II) and Co(II) complexes of the t-butylphenyl derivative of porphyrazine. J. Coord. Chem. 2010, 63, 3999–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkacher, H.; Taheur, F.B.; Amiri, N.; Almahri, A.; Loiseau, F.; Molton, F.; Vollbert, E.M.; Roisnel, T.; Turowska-Tyrk, I.; Nasri, H. DMAP and HMTA manganese(III) meso-tetraphenylporphyrin-based coordination complexes: Syntheses, physicochemical properties, structural and biological activities. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2023, 545, 121278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabli, S.; Hrichi, S.; Chaabane-Banaoues, R.; Molton, F.; Loiseau, F.; Roisnel, T.; Turowska-Tyrk, I.; Babba, H.; Nasri, H. Study on the synthesis, physicochemical, electrochemical properties, molecular structure and antifungal activities of the 4-pyrrolidinopyridine Mg(II) meso-tetratolylporphyrin complex. J. Mol. Struct. 2022, 1261, 132882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadda, A.A.; El-Gendy, E. , Refat, H.M.; Tawfik, E.H. Utility of dipyrromethane in the synthesis of some new A2B2 porphyrins and their related porphyrin-like derivatives with their evaluation as antimicrobial and antioxidant agents. Dyes Pigments 2021, 191, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potkin, V.I.; Bumagin, N.A.; Dikusar, E.A.; Petkevich, S.K.; Kurman, P.V. Functional Derivatives of 4-Formyl-2-methoxyphenyl Pyridine-4-carboxylate. Russ. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 55, 1483–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCDC 2309201 contains the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/conts/retrieving.html (or from the CCDC, 12 Union Road, Cambridge CB2 1EZ, UK; Fax: +44 1223 336033; E-mail: deposit@ccdc.cam.ac.uk).

- Ezzayani, K.; Denden, Z.; Najmudin, S.; Bonifácio, C.; Saint-Aman, E.; Loiseau, F.; Nasri, H. Exploring the Effects of Axial Pseudohalide Ligands on the Photophysical and Cyclic Voltammetry Properties and Molecular Structures of Mg II Tetraphenyl/porphyrin Complexes. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 5348–5361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guergueb, M.; Nasri, S.; Brahmi, J.; Loiseau, F.; Molton, F.; Roisnel, T.; Guerineau, V.; Turowska-Tyrk, I.; Aouadi, K.; Nasri, H. Effect of the coordination of π-acceptor 4-cyanopyridine ligand on the structural and electronic properties of meso -tetra(para -methoxy) and meso -tetra(para -chlorophenyl) porphyrin cobalt(ii) coordination compounds. Application in the catalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 6900–6918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dardouri, N.E.; Mkacher, H.; Ghalla, H.; Amor, F.B.; Hamdaoui, N.; Nasri, S.; Roisnel, T.; Nasri, H. Synthesis and characterization of a new cyanato-N cadmium(II) Meso-arylporphyrin complex by X-ray diffraction analysis, IR, UV/vis, 1H MNR spectroscopies and TDDFT calculations, optical and electrical properties. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1287, 135559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasri, S.; Zahou, I. , Turowska-Tyrk, I.; Roisnel, T.; Loiseau, F., Saint-Amant, E., Nasri, H. Synthesis, Electronic Spectroscopy, Cyclic Voltammetry, Photophysics, Electrical Properties and X-ray Molecular Structures of meso -{Tetrakis[4-(benzoyloxy)phenyl]porphyrinato}zinc(II) Complexes with Aza Ligands, Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2016, 5004–5019. [CrossRef]

- Colladet, K.; Nicolas, M.; Goris, L.; Lutsen, L.; Vanderzande, D. Low-band gap polymers for photovoltaic applications. Thin Solid Films 2004, 451–452, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thangam, R.; Suresh, V.; Kannan, S. Optimized extraction of polysaccharides from Cymbopogon citratus and its biological activities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 65, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carmona-Jiménez, Y.; García-Moreno, M.V.; Igartuburu, J.M.; Garcia Barroso, C. Simplification of the DPPH assay for estimating the antioxidant activity of wine and wine by-products. Food Chem. 2014, 165, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.Y.; Nanah, C.N.; Held, R.A.; Clark, A.R.; Huynh, U.G.T.; Maraskine, M.C.; Uzarski, R.L.; McCracken, J.; Sharma, A. Effect of electron donating groups on polyphenol-based antioxidant dendrimers. Biochimie 2015, 111, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrichi, S. , Chaabane-Banaoues, R.; Bayar, S.; Flamini, G.; Oulad El Majdoub Y.; Mangraviti, D., Mondello, L.; El Mzoughi, R.; Babba, H.; Mighri, Z.; Cacciola F. Botanical and Genetic Identification Followed by Investigation of Chemical Composition and Biological Activities on the Scabiosa atropurpurea L. Stem from Tunisian Flora. Molecules 2020, 25, 5032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hrichi, S.; Chaabane-Banaoues, R.; Giuffrida, D.; Mangraviti, D.; Majdoub, Y.O.E.; Rigano, F.; Mondello, L.; Babba, H.; Mighri, Z.; Cacciola, F. Effect of seasonal variation on the chemical composition and antioxidant and antifungal activities of Convolvulus althaeoides L. leaf extracts. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 5651–5668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruker, A.; Saint, A. Inc., Madison, WI, 2004 Search PubMed; ( b) Sheldrick, G.M. A Short History of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr. A, 2008, 64, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burla, M.C.; Caliandro, R.; Carrozzini, B.; Cascarano, G.L.; Cuocci, C.; Giacovazzo, C.; Mallamo, M.; Mazzone, A.; Polidori, G. Crystal structure determination and refinement via SIR2014. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2015, 48, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT – Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Fundam. Adv. 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McArdle, P. SORTX - a program for on-screen stick-model editing and autosorting of SHELX files for use on a PC. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1995, 28, 65–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrugia, L.J. ORTEP -3 for Windows - a version of ORTEP -III with a Graphical User Interface (GUI). J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1997, 30, 565–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macrae, C.F.; Bruno, I.J.; Chisholm, J.A.; Edgington, P.R.; McCabe, P.; Pidcock, E.; Rodriguez-Monge, L.; Taylor, R. , Van De Streek, J. ; Wood, P.A. Mercury CSD 2.0 – new features for the visualization and investigation of crystal structures, J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2008, 41, 466–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).