Submitted:

05 October 2024

Posted:

07 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

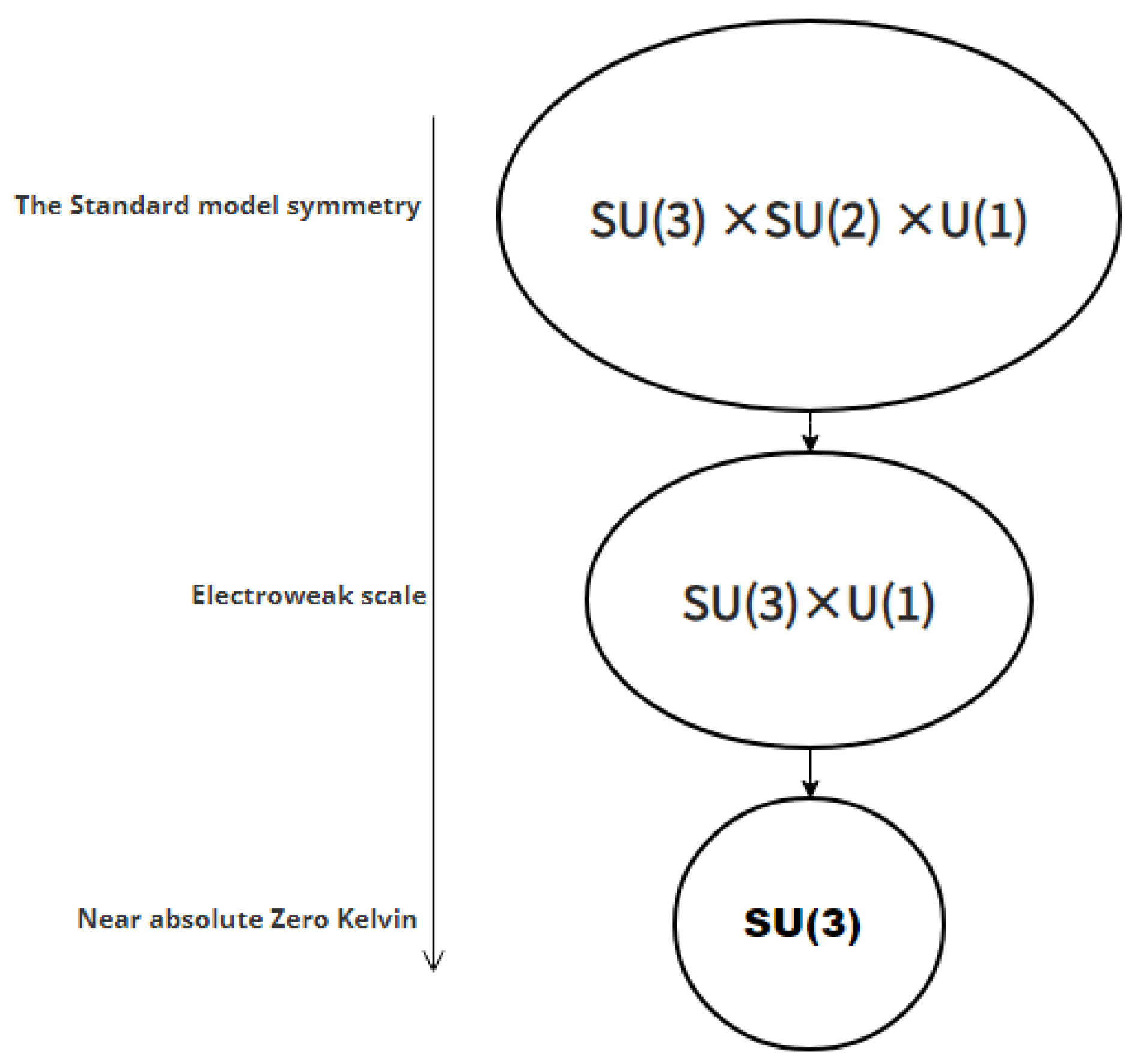

2. Manifesting Vacuum Atoms Through Symmetry Breaking

3. A Solution for the Cosmological Constant Problem

- The size of the vacuum atoms expands with the universe, keeping N constant. Assuming the proton expands at the same rate as the universe, we use the Hubble constant . Given the proton’s radius , the rate of expansion is . Over 14 billion years (universe age), the proton’s radius increases by . This scenario preserves the vacuum energy density and the cosmological constant, aligning with general relativity.

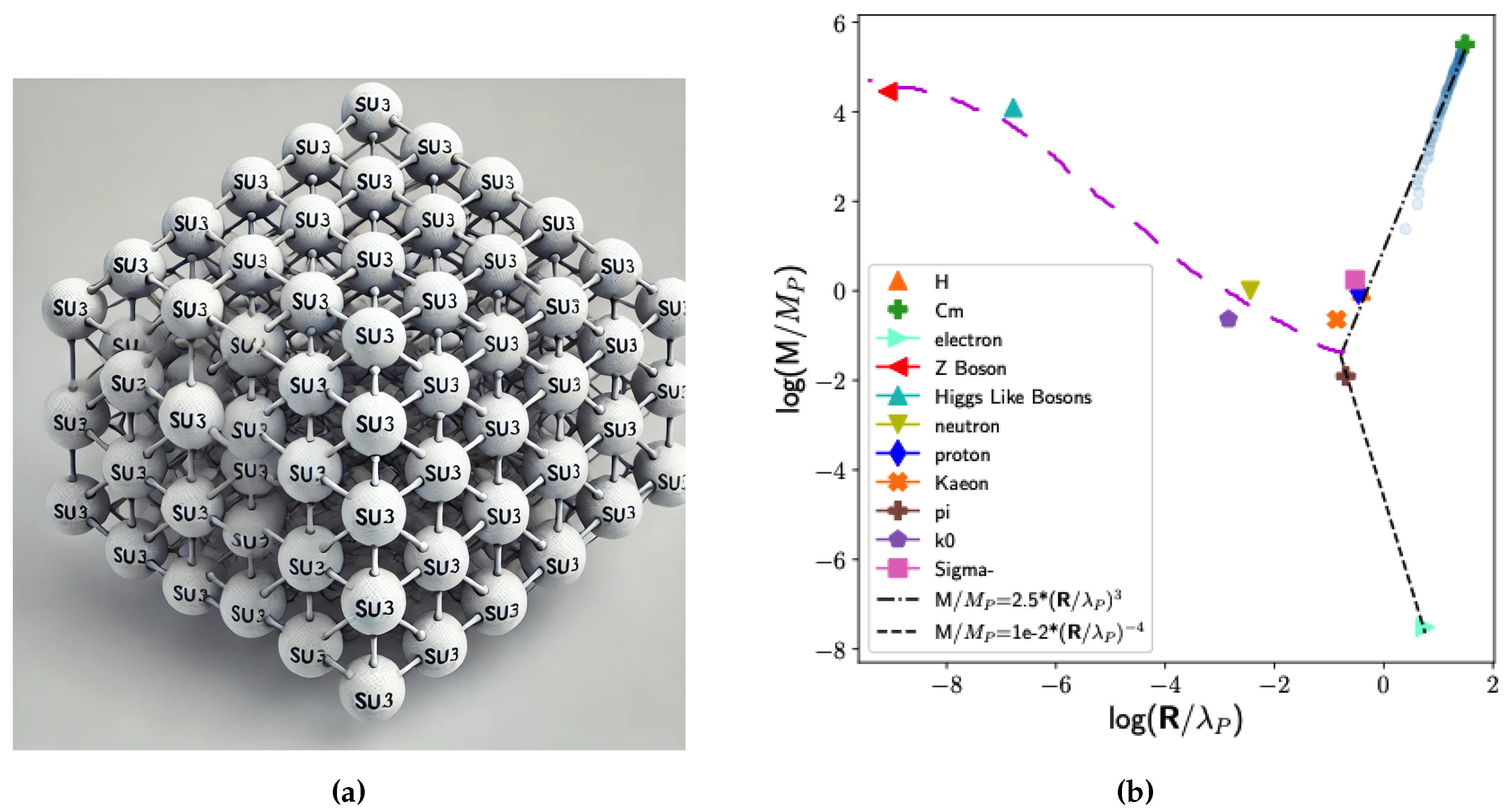

4. Vacuum Atoms/ Quantum Spacetime Correspondence

4.1. Spacetime Uncertainty: The Cause of Quantum Spacetime

4.2. Cosmological Constant in Quantum Spacetime

4.3. Geometric Implications

4.4. SU(3) Vacuum Atoms and Third Law of Thermodyanmics

4.5. Phenomenological Implications

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Glashow, S.L. Partial Symmetries of Weak Interactions. Nucl. Phys. 1961, 22, 579–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. A Model of Leptons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1967, 19, 1264–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salam, A. Weak and Electromagnetic Interactions. Conf. Proc. C 1968, 680519, 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgs, P.W. Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1964, 13, 508–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatrchyan, S.; others. Observation of a New Boson at a Mass of 125 GeV with the CMS Experiment at the LHC. Phys. Lett. B 2012, 716, 30–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfenstein, L. Neutrino Oscillations in Matter. Phys. Rev. D 1978, 17, 2369–2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheyev, S.P.; Smirnov, A.Y. Resonance Amplification of Oscillations in Matter and Spectroscopy of Solar Neutrinos. Sov. J. Nucl. Phys. 1985, 42, 913–917. [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra, R.N.; Senjanovic, G. Neutrino Mass and Spontaneous Parity Nonconservation. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1980, 44, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altarelli, G.; Feruglio, F. Discrete Flavor Symmetries and Models of Neutrino Mixing. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2010, 82, 2701–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gell-Mann, M. A Schematic Model of Baryons and Mesons. Phys. Lett. 1964, 8, 214–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Mathematical formulation of the quantum theory of electromagnetic interaction. Phys. Rev. 1950, 80, 440–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meissner, W.; Ochsenfeld, R. Ein neuer Effekt bei Eintritt der Supraleitfähigkeit. Naturwissenschaften 1933, 21, 787–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.D.; Harko, T. Superconducting dark energy. Phys. Rev. D 2015, 91, 085042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, N.; Ali, A.F.; Jusufi, K.; Yasser, A. Graviton mass due to dark energy as a superconducting medium-theoretical and phenomenological aspects. JCAP 2024, 08, 012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.S. Quantized space-time. Phys. Rev. 1947, 71, 38–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyla, P.A.; others. Review of Particle Physics. PTEP 2020, 2020, 083C01. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostriker, J.P.; Peebles, P.J.E.; Yahil, A. The size and mass of galaxies, and the mass of the universe. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1974, 193, L1–L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Einstein, A. The foundation of the general theory of relativity. Annalen Phys. 1916, 49, 769–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. The Cosmological Constant Problem. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1989, 61, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adame, A.G. others. DESI 2024 VI: Cosmological Constraints from the Measurements of Baryon Acoustic Oscillations. 2024, arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2404.03002. [Google Scholar]

- Adame, A.G. others. DESI 2024 III: Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from Galaxies and Quasars. 2024, arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2404.03000. [Google Scholar]

- Adame, A.G. others. DESI 2024 IV: Baryon Acoustic Oscillations from the Lyman Alpha Forest 2024. arXiv:astro-ph.CO/2404.03001.

- Solà Peracaula, J.; de Cruz Pérez, J.; Gómez-Valent, A. Dynamical dark energy vs. Λ = const in light of observations. EPL 2018, 121, 39001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.; Witten, E. Quantum yang-mills theory. The millennium prize problems 2006, 1, 129. [Google Scholar]

- Heisenberg, W. Letter of Heisenberg to Peierls (1930); Springer-Verlag, 1985; p. 15. [Google Scholar]

- Connes, A. Non-commutative differential geometry. Publications Mathematiques de l’IHES 1985, 62, 41–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woronowicz, S.L. Compact matrix pseudogroups. Communications in Mathematical Physics 1987, 111, 613–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connes, A.; Douglas, M.R.; Schwarz, A.S. Noncommutative geometry and matrix theory: Compactification on tori. JHEP 1998, 02, 003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seiberg, N.; Witten, E. String theory and noncommutative geometry. JHEP 1999, 09, 032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, M.R.; Nekrasov, N.A. Noncommutative field theory. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2001, 73, 977–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabo, R.J. Quantum field theory on noncommutative spaces. Physics Reports 2003, 378, 207–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amati, D.; Ciafaloni, M.; Veneziano, G. Can Space-Time Be Probed Below the String Size? Phys. Lett. B 1989, 216, 41–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.J. Quantum gravity and minimum length. Int. J. Mod. Phys. A 1995, 10, 145–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardigli, F. Generalized uncertainty principle in quantum gravity from micro - black hole Gedanken experiment. Phys. Lett. B 1999, 452, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, M. A Generalized uncertainty principle in quantum gravity. Phys. Lett. B 1993, 304, 65–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capozziello, S.; others. Generalized uncertainty principle from quantum geometry. Int. J. Theor. Phys. 2000, 39, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Vagenas, E.C. Universality of Quantum Gravity Corrections. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 221301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pikovski, I.; others. Probing Planck-scale physics with quantum optics. Nature Phys. 2012, 8, 393–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marin, F.; others. Gravitational bar detectors set limits to Planck-scale physics on macroscopic variables. Nature Phys. 2013, 9, 71–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruzziello, L.; others. Quantum gravitational decoherence from fluctuating minimal length and deformation parameter at the Planck scale. Nature Commun. 2021, 12, 4449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.P.; others. On Quantum Gravity Tests with Composite Particles. Nature Commun. 2020, 11, 3900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradpour, H.; others. The generalized and extended uncertainty principles and their implications on the Jeans mass. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2019, 488, L69–L74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, D.; Zhan, M. Constraining the generalized uncertainty principle with cold atoms. Phys. Rev. A 2016, 94, 013607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bawaj, M.; others. Probing deformed commutators with macroscopic harmonic oscillators. Nature Commun. 2015, 6, 7503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Easther, R.; others. Imprints of short distance physics on inflationary cosmology. Phys. Rev. D 2003, 67, 063508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kober, M. Gauge Theories under Incorporation of a Generalized Uncertainty Principle. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 82, 085017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossenfelder, S. Minimal Length Scale Scenarios for Quantum Gravity. Living Rev. Rel. 2013, 16, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignemi, S. Progress in Snyder model. PoS 2020, CORFU2019, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, M.V.; Meljanac, S. Modification of Heisenberg uncertainty relations in noncommutative Snyder space-time geometry. Phys. Rev. D 2009, 79, 067505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battisti, M.V.; Meljanac, S. Scalar Field Theory on Non-commutative Snyder Space-Time. Phys. Rev. D 2010, 82, 024028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, M. Quantum groups, gravity and the generalized uncertainty principle. Phys. Rev. D 1994, 49, 5182–5187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.F.; Das, S.; Vagenas, E.C. Discreteness of Space from the Generalized Uncertainty Principle. Phys. Lett. B 2009, 678, 497–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.F.; Das, S.; Vagenas, E.C. A proposal for testing Quantum Gravity in the lab. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 84, 044013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, A.D.; Hofheinz, M.; Ansmann, M.; Bialczak, R.C.; Lenander, M.; Lucero, E.; Neeley, M.; Sank, D.; Wang, H.; Weides, M.; others. Quantum ground state and single-phonon control of a mechanical resonator. Nature 2010, 464, 697–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrews, M.; Townsend, C.; Miesner, H.J.; Durfee, D.; Kurn, D.; Ketterle, W. Observation of interference between two Bose condensates. Science 1997, 275, 637–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.G.; Adelberger, E.G.; Cook, T.S.; Fleischer, S.M.; Heckel, B.R. New Test of the Gravitational 1/r2 Law at Separations down to 52 μm. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2020, 124, 101101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.J. Six easy roads to the Planck scale. Am. J. Phys. 2010, 78, 925–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regge, T. Gravitational fields and quantum mechanics. Nuovo Cim. 1958, 7, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.J.; van Dam, H. Measuring the foaminess of space-time with gravity - wave interferometers. Found. Phys. 2000, 30, 795–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, Y.J.; van Dam, H. Limitation to quantum measurements of space-time distances. Annals N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1995, 755, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christiansen, W.A.; Ng, Y.J.; Floyd, D.J.E.; Perlman, E.S. Limits on Spacetime Foam. Phys. Rev. D 2011, 83, 084003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, C.A. Possible Connection Between Gravitation and Fundamental Length. Phys. Rev. 1964, 135, B849–B862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilkovisky, G.A. Effective action in quantum gravity. Class. Quant. Grav. 1992, 9, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeWitt, B.S. Gravity: a universal regulator? Physical Review Letters 1964, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, C.A. Observable consequences of fundamental-length hypotheses. Physical Review 1966, 143, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garay, L.J. Quantum evolution in space–time foam. International Journal of Modern Physics A 1999, 14, 4079–4120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feynman, R.P. Space-time approach to nonrelativistic quantum mechanics. Rev. Mod. Phys. 1948, 20, 367–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorji, M.A.; Nozari, K.; Vakili, B. Spacetime singularity resolution in Snyder noncommutative space. Phys. Rev. D 2014, 89, 084072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivetić, B. Diffeomorphisms of the energy-momentum space: perturbative QED. Nuclear Physics B 2024, 116692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kempf, A.; Mangano, G. Minimal length uncertainty relation and ultraviolet regularization. Phys. Rev. D 1997, 55, 7909–7920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girelli, F.; Livine, E.R. Scalar field theory in Snyder space-time: Alternatives. JHEP 2011, 03, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahns, D.; Doplicher, S.; Fredenhagen, K.; Piacitelli, G. Ultraviolet finite quantum field theory on quantum space-time. Commun. Math. Phys. 2003, 237, 221–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, P.; Das, S.; Todorinov, V. Quantum field theory with the generalized uncertainty principle I: Scalar electrodynamics. Annals Phys. 2020, 422, 168319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosso, P.; Das, S.; Todorinov, V. Quantum field theory with the generalized uncertainty principle II: Quantum Electrodynamics. Annals Phys. 2021, 424, 168350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meljanac, S.; Mignemi, S.; Trampetic, J.; You, J. Nonassociative Snyder ϕ4 Quantum Field Theory. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 045021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.N.; Minic, D.; Okamura, N.; Takeuchi, T. The Effect of the minimal length uncertainty relation on the density of states and the cosmological constant problem. Phys. Rev. D 2002, 65, 125028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.N.; Lewis, Z.; Minic, D.; Takeuchi, T. On the Minimal Length Uncertainty Relation and the Foundations of String Theory. Adv. High Energy Phys. 2011, 2011, 493514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. Geons. Phys. Rev. 1955, 97, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. On the Nature of quantum geometrodynamics. Annals Phys. 1957, 2, 604–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawking, S.W. Space-Time Foam. Nucl. Phys. B 1978, 144, 349–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlip, S. Spacetime foam: a review. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.F.; Inan, N. Unraveling the mystery of the cosmological constant: Does spacetime uncertainty hold the key?(a). EPL 2023, 143, 49001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freidel, L.; Kowalski-Glikman, J.; Leigh, R.G.; Minic, D. Vacuum energy density and gravitational entropy. Phys. Rev. D 2023, 107, 126016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zel’dovich, Y.B.; Krasinski, A.; Zeldovich, Y.B. The Cosmological constant and the theory of elementary particles. Sov. Phys. Usp. 1968, 11, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello, P.G.; Succi, S.; Bini, D.; Kauffman, S. From quantum foam to graviton condensation: The Zel’dovich route. EPL 2023, 143, 39002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.F. The Mass Gap of the Spacetime and Its Shape. Fortsch. Phys. 2024, 2024, 2200210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.P.; Pu, J.; Han, Y.; Jiang, Q.Q. A possible thermodynamic origin of the spacetime minimum length. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2020, 29, 2043022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.F.; Elmashad, I.; Mureika, J. Universality of minimal length. Phys. Lett. B 2022, 831, 137182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.F.; Mureika, J.; Vagenas, E.C.; Elmashad, I. Theoretical and observational implications of Planck’s constant as a running fine structure constant. Int. J. Mod. Phys. D 2024, 33, 2450036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhalerao, R.S. Relativistic heavy-ion collisions. 1st Asia-Europe-Pacific School of High-Energy Physics. 2014, 219–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ianni, A.; Mannarelli, M.; Rossi, N. A new approach to dark matter from the mass–radius diagram of the Universe. Results Phys. 2022, 38, 105544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritzsch, H. The size of the weak bosons. Physics Letters B 2012, 712, 231–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehnert, B. Mass-Radius Relations of Z and Higgs-Like Bosons. PROGRESS IN PHYSICS 2014, 10, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, I.; Marinova, K.P. Table of experimental nuclear ground state charge radii: An update. Atomic Data and Nuclear Data Tables 2013, 99, 69–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.M. The Large N limit of superconformal field theories and supergravity. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 231–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strominger, A. The dS / CFT correspondence. JHEP 2001, 10, 034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witten, E. Anti-de Sitter space and holography. Adv. Theor. Math. Phys. 1998, 2, 253–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubser, S.S.; Klebanov, I.R.; Polyakov, A.M. Gauge theory correlators from noncritical string theory. Phys. Lett. B 1998, 428, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnoll, S.A.; Herzog, C.P.; Horowitz, G.T. Holographic Superconductors. JHEP 2008, 12, 015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carenza, P.; Pasechnik, R.; Salinas, G.; Wang, Z.W. Glueball Dark Matter Revisited. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2022, 129, 261302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, B.S.; Fairbairn, M.; Hardy, E. Glueball dark matter in non-standard cosmologies. JHEP 2017, 07, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | In QFT, temperature corresponds to the intrinsic energy of the quantum fields themselves, expressed as . |

| Era | Temperature Range | Energy Scale | Unbroken Symmetry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiation-Dominated Era | |||

| Matter-Dominated Era | |||

| Dark Energy-Dominated Era |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).