1. Introduction

Motivation is a vital element for academic achievement and general well-being among students. While some students may be motivated by external factors such as career advancement or financial stability, a subset of mature students are driven by intrinsic motivations [

1]. Intrinsic motivation is defined as the drive to engage in an activity for its own sake rather than for external rewards or pressures. When intrinsically motivated, students are more likely to demonstrate initiative, persistence, and creativity in their learning journey. This contrasts with extrinsic motivation, which involves external rewards or consequences to driving behaviour [

2]. Research has shown that intrinsic motivation is key to student success and academic achievement. Intrinsically motivated students are more likely to set challenging goals, be actively engaged in their learning, and exhibit higher levels of persistence when faced with obstacles. In contrast, extrinsically motivated students may only perform well when there is a reward or punishment involved, leading to surface-level learning and a lack of true understanding [

3]. Within the intricate tapestry of motivation lies a theory that beckons us to delve deeper: Self-determination theory (SDT), as articulated by Ryan and Deci in 2000. At its core, SDT illuminates the concept of autonomous intrinsic motivation—engaging in an activity for its inherent purpose or the sheer joy and fulfilment it brings. Picture students who immerse themselves in reading not out of external obligation but driven by a genuine interest—an inner flame of intrinsic motivation. Motivation is multifaceted. When tasks are undertaken purely for pragmatic reasons, devoid of inherent value, they become tethered to external factors. Ryan and Deci aptly label this as extrinsically motivated behaviour. But what about the quiet pull—the intrinsic desire—that beckons us to create, explore, and learn? Research consistently reveals that this intrinsic motivation is intricately woven into our mental well-being. It forms the connective thread between our autonomy, happiness, and personal fulfilment, ultimately shaping our overall quality of life [

4].

In this context, consider mature students—the seasoned learners navigating the educational landscape. Their intrinsic motivation becomes a compass, guiding them toward success and well-being. As educators and policymakers, we hold the key to nurturing this flame. By identifying the elements that fortify intrinsic motivation, we can foster a positive learning environment where mature students thrive both in the United Kingdom and beyond [

5]. But there’s more: the symbiosis between intrinsic motivation and effective teaching. Understanding this intrinsic drive becomes paramount as future educators prepare for their roles. It’s the heartbeat of a vibrant teaching-learning process, where passion fuels growth and curiosity ignites transformation [

6].

Understanding the relationship between intrinsic motivation and mental well-being among mature students is crucial to support their academic success and overall well-being [

7]. Intrinsic motivation plays a crucial role in promoting mental well-being among mature students in higher education. By providing autonomy, fostering competence, and enhancing relatedness, intrinsic motivation empowers mature students to thrive in their academic pursuits and maintain positive mental health [

8]. The study of intrinsic motivation and its impact on the mental well-being of mature students holds significant importance. These students, typically aged 25 years and older, face unique challenges as they return to college or university after a hiatus from full-time study [

9]. Balancing multiple responsibilities related to work, family, and finances adds complexity to their academic journey. It is crucial to understand the factors contributing to their success and overall well-being [

10]. Mental well-being encompasses an individual’s psychological functioning, life satisfaction, and capacity to cultivate mutually beneficial relationships. It extends beyond the mere absence of disorders. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), mental well-being signifies a state where individuals realise their potential, effectively cope with life’s stresses, contribute productively to their communities, and work fruitfully (WHO, 2004). Stewart-Brown [

10] states, “Mental well-being relates to a person’s psychological functioning, life satisfaction, and ability to develop and maintain mutually beneficial relationships.” Wellness encompasses diverse and interconnected physical, mental, and social dimensions extending beyond the traditional definition of health. It includes choices and activities aimed at achieving physical vitality, mental agility, social satisfaction, a sense of accomplishment, and personal fulfilment [

11].

Over time, mental health professionals have recognised that their efforts should focus on both preventing mental illness and enhancing mental health. The terms “positive mental health” and “mental well-being,” both positively oriented and interchangeable, have gained prominence among contemporary scholars. Even though a person has a mental health illness of any kind, these positive phrases are typically seen as desirable qualities. Various psychological and social markers can be used to evaluate well-being, which is more than just the absence of mental disease. These markers include happiness, life satisfaction, depression, anxiety, and self-esteem [

12].

A comprehensive approach to mental health incorporates a range of ideas and theoretical stances from various disciplines, including anthropology, education, psychology, sociology, religion, social work, personality, clinical psychology, and developmental psychology [

13]. Researchers now consider mental well-being from two significant perspectives, namely the subjective experience of happiness (affect) and life satisfaction (the hedonic perspective); and positive psychological functioning, good relationships with others and self-realisation (the eudaimonic perspective) [

14,

15,

16]. In developed nations like the UK, the importance of mental health for mature students is increasingly recognised as a vital component of their educational journey. Mature students—those who typically enrol in higher education after turning 21—often face specific challenges that can impact their mental well-being while pursuing their academic goals.

The main objectives of this study are to determine the relationship between intrinsic motivation and mental well-being among mature students and to confirm the factor structure of both the intrinsic motivation scale and the mental well-being scale. Research questions of the study are: What is the relationship between intrinsic motivation and the mental well-being of mature students? How stable is the factor structure of both the intrinsic motivation scale and the mental well-being scale?

3. Results

In the Results section, we present compelling evidence of a significant positive correlation between intrinsic motivation and the mental well-being of mature students. The results are presented below.

The univariate descriptive statistics concerning continuous variables show that the mean score of mental well-being was higher (M=28.86; SD=5.50) among students than intrinsic motivation (M=16.82; SD=2.94) (

Table 1). Moreover, there were more male participants (52.4%) than females (47.6%) in the study. The majority of participants were first-year students (56.9%) and in the age range 36-45 years (37.1%) (

Table 2).

Pearson correlation analysis was conducted before performing linear regression. It is common practice to explore the relationship between variables using correlation analysis before moving on to regression analysis. Pearson correlation measures the strength and direction of a linear relationship between two continuous variables. By calculating the correlation coefficient, we can determine whether there is a significant association between the variables and the direction of the relationship (positive or negative) [

17].

The Pearson correlation coefficient among the continuous variables under study revealed a significant positive relationship (

Table 3). According to the correlation results, intrinsic motivation is positively associated with mental well-being. This finding supports hypothesis 1, indicating a significant correlation between intrinsic motivation and the mental well-being of mature students. Specifically, we observed a moderate correlation (r = 0.537, n = 248, p = 0.005) between mature students' intrinsic motivation and mental well-being.

3.1. Further Analysis: Simple Linear Regression

A linear regression model was run, considering intrinsic motivation as a predictor of mental well-being (criterion). The obtained results indicate that intrinsic motivation significantly predicts mental well-being (R² = 0.35, F(1,246) = 99.82, p < 0.01). Specifically, intrinsic motivation explains 35% of the variance in mental well-being among mature students, and this relationship is statistically significant at the p < 0.01 level. The F-statistic value of 99.82 with degrees of freedom (1,246) suggests that the regression model is statistically significant. The p-value is less than 0.01, which signifies that the relationship between intrinsic motivation and mental well-being is statistically significant at a level of p < 0.01. Thus, our findings support hypothesis 2, suggesting that the regression coefficient for predicting mental well-being based on intrinsic motivation is nonzero. In other words, the slope of the regression line is not zero, and changes in the predictor variable (intrinsic motivation) lead to corresponding changes in the criterion variable (mental well-being) by approximately β = 0.59 units. Additionally, Cohen’s effect size value (f² = 0.54) indicates a moderate strength of association between intrinsic motivation and mental well-being in mature students.

3.2. CFA and Model Fit Indices

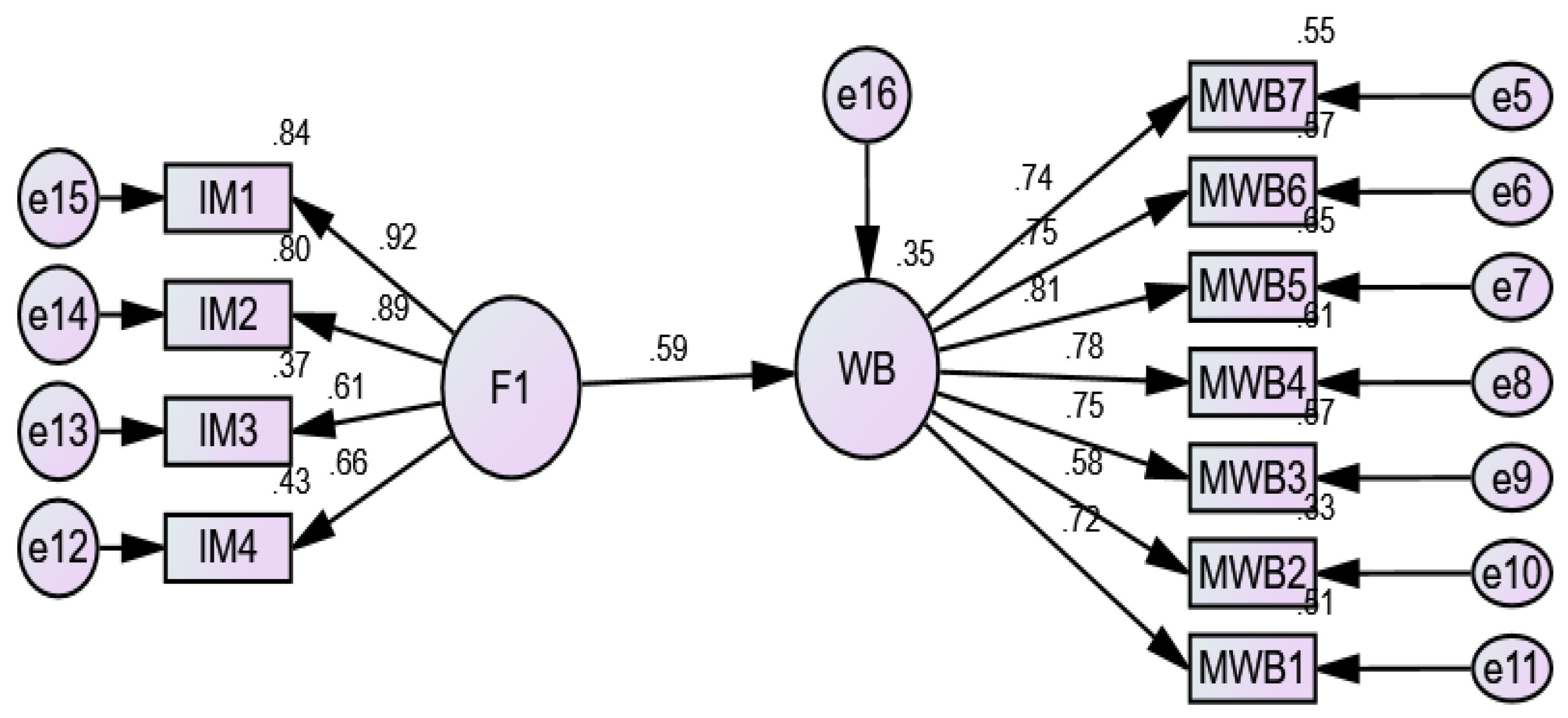

We conducted a first-order confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using the maximum likelihood method in AMOS v23.0 (

Figure 1). Multiple goodness-of-fit tests were employed to assess the model’s suitability for the data. The fit indices, including CMIN/DF, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness of Fit Index (GFI), and Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI), generally fell within acceptable ranges, indicating a good fit to the data. However, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) value was borderline, suggesting some room for improvement.

Our CFA aimed to determine whether the proposed one-factor solution adequately fit the data from a sample of 248 mature students. The indices mentioned above strongly supported the fit of the sample data to the model. Additionally, we assessed the overall convergent validity of the measurement model by calculating the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and Composite Reliability (CR) scores for the intrinsic motivation and mental well-being scales. The AVE values indicate the amount of variance captured by the latent constructs relative to the amount of variance due to measurement error. AVE values above 0.5 are generally considered acceptable for convergent validity. In our study, the AVE values for the intrinsic motivation scale (0.612) and the mental well-being scale (0.948) meet this criterion, suggesting that these constructs adequately represent their respective indicators. The CR values provide information on the internal consistency reliability of the latent constructs, with values above 0.7 typically considered acceptable. In your analysis, the CR values for intrinsic motivation (0.859) and mental well-being (0.891) indicate good reliability for both scales.

These results indicate that the measurement model exhibits strong convergent validity, with the latent constructs (intrinsic motivation and mental well-being) showing adequate variance extraction and reliability based on the AVE and CR scores, respectively.

4. Discussion

The current study aims to explore the relationship between intrinsic motivation and well-being among mature students in the UK. The objective of our study was twofold. First, we aimed to assess the relationship between intrinsic motivation and the mental well-being of mature students. Our findings revealed a significant positive correlation between these two variables. Thus, we successfully achieved our initial research objective: to determine the link between intrinsic motivation and mental well-being among mature students. Numerous studies have explored the relationship between intrinsic motivation and mental well-being among various populations, including students. Our results align with prior research, suggesting that individuals with higher levels of intrinsic motivation and recognised regulation experience more positive emotions in the classroom. Additionally, they derive greater satisfaction from their academic work and express overall contentment with their education. Consequently, these students exhibit stronger well-being than those with less autonomous motivational profiles [

18]. The study that aligns with our findings is research conducted by Ryan and Deci [

4], who proposed the self-determination theory. Research on self-determination theory looks at how society shapes psychological growth and self-motivation. It proposes three basic psychological demands that, when met, improve motivation and mental health: relatedness, competence, and autonomy. These demands are essential in many areas, including job, education, athletics, mental health, and religion. Most contemporary theories of motivation centre on objectives or results as well as the instrumentalities that lead to these intended outcomes. These theories focus on how behaviour is directed, or the mechanisms that guide behaviour towards intended goals, but they ignore why particular goals are wanted. As a result, they do not deal with the problem of behaviour energisation [

4]. According to their theory, intrinsic motivation is crucial in fostering individuals' psychological well-being and overall satisfaction with life. Another study by Carbonneau, Vallerand and Lafrenière [

19] also supports our findings. They found that intrinsically motivated individuals tend to have higher levels of well-being, including positive affect, self-esteem, and overall life satisfaction. Additionally, a study by Ng et al. [

20] specifically investigated the relationship between intrinsic motivation and mental well-being among mature students. They found that mature students who reported higher levels of intrinsic motivation also had greater mental well-being. Furthermore, a study by Gonzalez Olivares et al. [

21] found a positive correlation between students’ psychological well-being and their intrinsic motivation to start a teaching career. Burton et al.'s [

22] study explored the effects of intrinsic regulation on psychological well-being. It found that environmental cues associated with intrinsically motivated goals predict increases in psychological well-being. Based on our findings, we can conclude that intrinsic motivation plays a crucial role in the well-being of mature students. Studies have shown that individuals with higher levels of intrinsic motivation experience more positive emotions in the classroom and express greater satisfaction with their academic work and overall contentment with their education.

The second objective of our study was to validate the factor structure of the intrinsic motivation and mental well-being scales. We found that both scales confirmed a one-factor solution based on the sample data from mature students. Additionally, our results highlighted that intrinsic motivation significantly predicts mental well-being, even among non-traditional students. This finding supports our hypothesis that the regression coefficient for predicting mental well-being through intrinsic motivation would be non-zero. The regression results are consistent with existing evidence, which suggests that individuals with higher levels of self-compassion are more likely to be intrinsically motivated [

23]. Also, a study by Neff and Hsieh [

24] explores the relationship between self-compassion, intrinsic motivation, and academic performance in college students. It provides evidence that self-compassion positively influences intrinsic motivation, which aligns with our findings. Namely, the university dropout rates for mature students are a pressing concern in academia. This population of students, who are typically older and have returned to education after a significant break, faces unique challenges that can impact their ability to complete their studies successfully. These challenges may include financial constraints, family and work responsibilities, lack of academic preparedness, and feelings of isolation or disconnection from the younger student population on campus. To address these challenges and improve the retention rates of mature students, it is important to implement targeted strategies and support mechanisms. These strategies might include developing mentorship programs, flexible course schedules, and customised academic support services [

25]. Mature students tend to achieve higher academic success, which indicates their strong intrinsic drive [

26,

27]. According to previous research, mature students are more intrinsically motivated than typical students, which gives them a greater will to complete their coursework [

28] effectively. Motivation levels are a result of locus of control. Those who are motivated intrinsically have an innate desire to learn, whereas those who are motivated extrinsically seek out outside benefits to force them to do so. It is contradictory to categorise motivation levels by age, as some say that traditional students display intrinsic motivation comparable to that of their more experienced peers [

29].

Teachers have long utilised intrinsic motivation as a resource to meet needs-based objectives and serve as a natural source of learning. Certain activities are pursued not so much for the outcome as for the participant’s intrinsic fulfilment [

6]. For students to be actively engaged in the educational process, they must value learning, progress, and accomplishment—even in subjects and activities they find uninteresting. The process of internalisation and integration leads to this valuing [

30]. Interestingly, despite possessing high levels of intrinsic drive, mature students are more than twice as likely to drop out of university in their first year as traditional students [

31]. This suggests that mature students’ university experiences are unlikely solely influenced by their inherent drive. To prevent more dropouts and gain better insights, a deeper understanding of the challenges impacting students on and off campus is necessary [

32]. Therefore, the challenges faced by mature students in managing their mental health are significant, but there are also many opportunities for support and growth. By acknowledging the unique stressors faced by mature students and implementing targeted interventions, educational institutions can better support this population. Universities and colleges must provide accessible mental health resources, foster a sense of community and belonging, and offer flexibility in academic programs. Moreover, promoting open and non-judgmental discussions around mental health can help reduce stigma and encourage individuals to seek help when needed. Overall, addressing the mental health challenges of mature students not only enhances their educational experience but contributes to their overall well-being and success.

Although maintaining university students' well-being is a government goal, there has not been much solid data, specifically on non-traditional students. Student mental health issues can be caused by moving away from home, stress from the workload changes in finances, and other circumstances. Better mental and physical health, increased self-esteem, self-efficacy, and the ability to effectively cope are all linked to higher well-being [

33]. It has been determined that some specific student populations are more susceptible to mental health problems or suicide attempts, such as individuals from underprivileged origins are more prone to mental health problems, and these students may also have unique financial difficulties [

34]. Additionally, mature students could feel more alone because they cannot interact socially. They might also be financially strained and have childcare duties [

35]. Furthermore, mature students often face increased stress due to full or part-time work, caring responsibilities, managing long-term health conditions, and significant financial responsibilities. These factors can lead to increased stress and disruptions in their studies, potentially affecting their ability to engage in higher education [

36]. Mature students’ mental health and well-being in the UK constitute a complex and integral aspect of their academic and personal experience [

24]. It also constitutes a complex and integral aspect of their academic and personal experience [

37]. Typically defined as individuals aged 21 years or older who are embarking on higher education, mature students encounter specific challenges and opportunities that significantly impact their mental health. These students may also require support in shaping a new learner identity [

38]. Moreover, mature students often bring a wealth of resilience, motivation, and life experience to their academic endeavours [

39]. Cultivating an environment that prioritises mental wellness necessitates recognising and harnessing these attributes. Support services and educational institutions play a crucial role in addressing the unique needs of mature students. Specialised mental health programs, academic support, and community-building efforts can help them overcome obstacles.

Significantly, intrinsic motivation is influenced by various circumstances. It’s worth noting that intrinsic motivation is not exclusive to the experiences of mature students; it can also be observed in traditional student populations, albeit somewhat less [

40]. Addressing mental health issues among mature students requires a multifaceted approach that integrates academic, social, and emotional support. This includes initiatives such as campus community-building programs, peer mentorship, and easily accessible counselling services. In summary, a comprehensive approach that combines academic, social, and emotional support is vital for promoting mental health among mature students.

5. Conclusions

Our investigation into the relationship between intrinsic motivation and the mental well-being of mature students has yielded valuable insights. The positive correlation we observed underscores the importance of fostering intrinsic motivation within this demographic. As mature students navigate their educational journey, acknowledging their unique challenges and providing targeted support can significantly enhance their well-being. Prioritising mature students’ mental health and well-being in the UK is crucial for their success in postsecondary education. Creating a more welcoming and encouraging learning environment for senior students involves not only addressing their unique difficulties but also leveraging their rich life experiences and talents. By establishing supportive and inclusive learning environments, higher education institutions can contribute to the overall success of this diverse student population. As Western nations, including the UK, increasingly recognise the varied needs of their student body, implementing programs aimed at bolstering the psychological well-being of experienced learners becomes paramount. Outreach initiatives, adaptable academic systems, and specialised counselling services are essential to this holistic approach.

In conclusion, it is critical to prioritise mature students' mental health and well-being in the UK to ensure their success in postsecondary education. A more welcoming and encouraging learning environment for senior students can be achieved by acknowledging and resolving the unique difficulties they encounter and using their experiences and talents. Establishing a supportive and inclusive learning environment for mature students requires acknowledging and attending to their mental health. Higher education establishments in Western nations, such as the UK, are progressively recognising the varied requirements of their student body and executing programmes aimed at bolstering the psychological well-being of experienced learners. This involves outreach initiatives to improve social inclusion, adaptable academic systems, and specialised counselling services. Furthermore, mature students' academic progress and general well-being in Western nations, especially the UK, correlate directly with their mental health. Recognising and resolving individuals' particular difficulties and offering suitable assistance enhances their well-being and the general success of the higher education community.

It is essential to recognise the limitations of our study. First, our research focused on intrinsic motivation and mental well-being, leaving other potential factors unexplored. Future studies could delve deeper into additional variables, such as social support networks, coping mechanisms, and external stressors. Moreover, longitudinal research is necessary to understand the dynamic nature of intrinsic motivation and its impact on mental health over time. Tracking mature students’ well-being throughout their educational experience would provide valuable insights into effective interventions and support strategies.