Submitted:

23 May 2024

Posted:

24 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

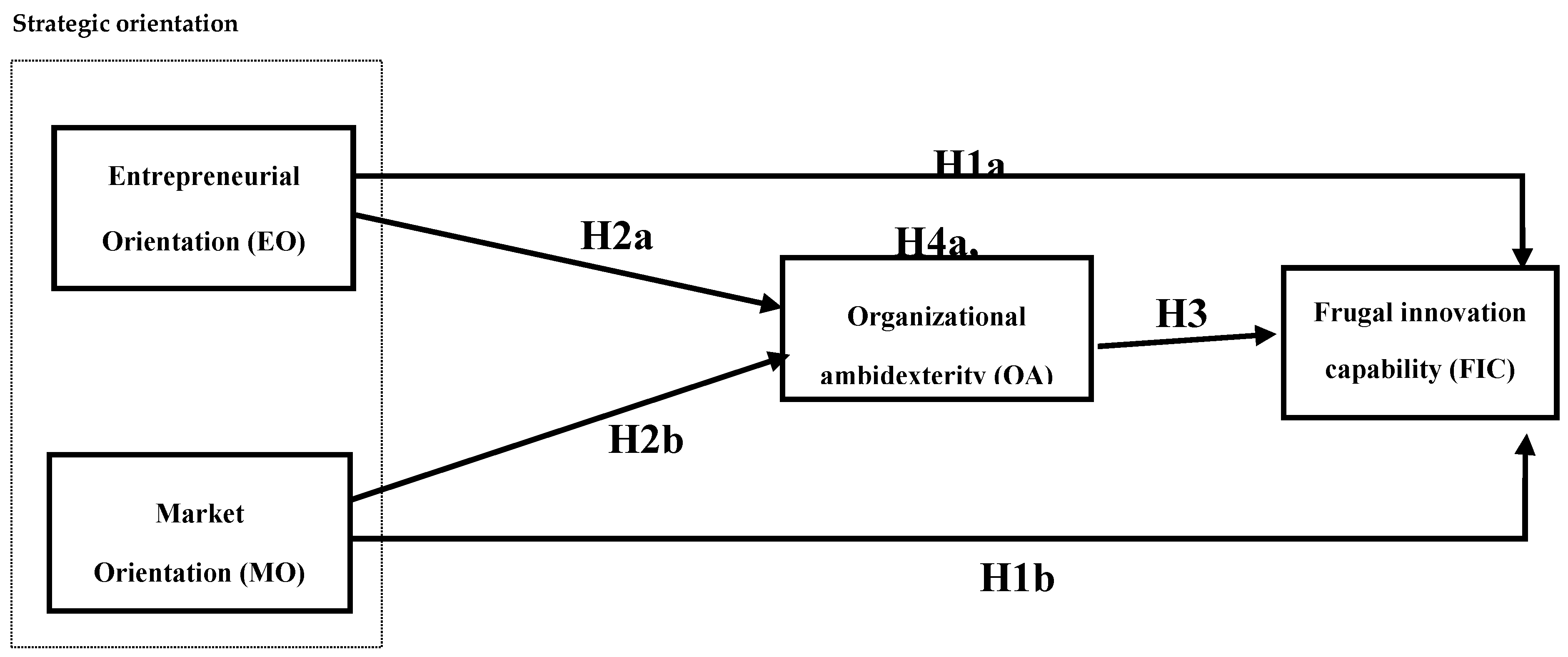

2. Literature Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Frugal Innovation

2.2. Strategic Orientation

2.2.1. Entrepreneurial Orientation

2.2.2. Market Orientation

2.3. Organizational Ambidexterity

2.4. Strategic Orientation and Frugal Innovation Capability

2.5. Strategic Orientation and Organizational Ambidexterity

2.6. Organizational Ambidexterity and Frugal Innovation Capability

2.7. Mediating Effect of Organizational Ambidexterity

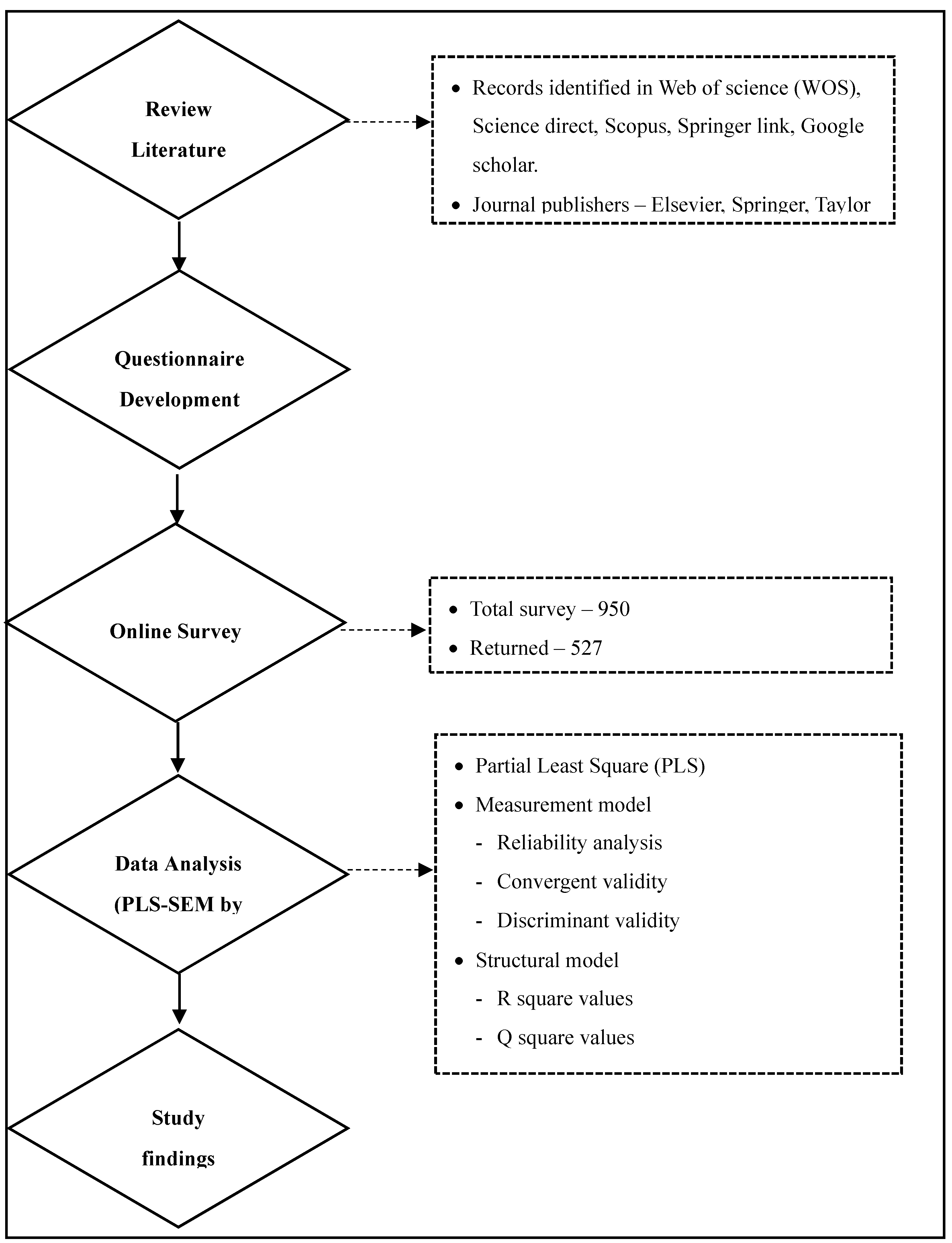

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design and Data Collection Method

3.2. Sampling Method and Sample Size Determination

3.3. Measurement of Constructs

3.3.1. Strategic Orientation

3.3.2. Organizational Ambidexterity

3.3.3. Frugal Innovation Capability

3.4. Model Specification and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

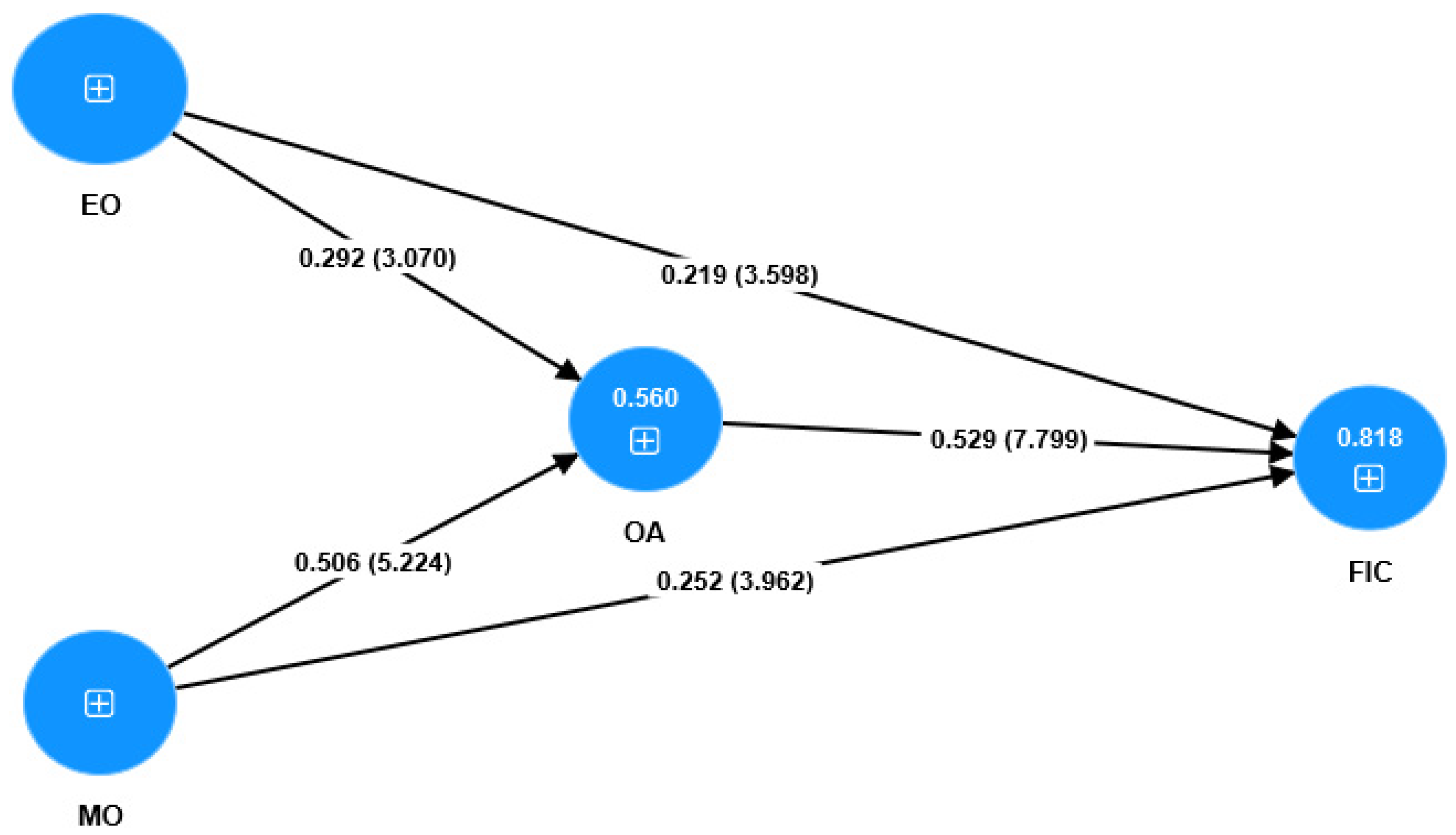

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Mediation Role of Organizational Ambidexterity

5. Discussion and Conclusion

5.1. Discussion

5.2. Conclusion

6. Implications and Avenues for Future Research

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Avenues for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Code | Items | Sources |

| Indicate to which extent you agree with the following statements about your company | |||

| Entrepreneurial Orientation | INN1 | In the past three years, our company introduced and encouraged novel ideas, products or services. | [81] |

| INN2 | In general, our company favor a strong emphasis on R&D, technological leadership, and innovations. | ||

| INN3 | in our company changes in product or service lines have usually been quite dramatic. | ||

| RISK1 | Our company tends to strongly favor high-risk projects (with chances of very high returns). | ||

| RISK2 | Owing to the nature of the environment, our company favors bold and wide-ranging actions to achieve its fixed objectives. | ||

| RISK3 | When confronted with decisions involving uncertainty, our company typically adopts a bold posture in order to maximize the probability of exploiting opportunities. | ||

| PRO1 | In general, our company have a strong tendency to be ahead of others in introducing novel ideas or products. | ||

| PRO2 | In dealing with competitors, our company is very often the first business to introduce new products/services, administrative techniques or operating technologies. | ||

| PRO3 | In dealing with competitors, our company typically initiate actions that competitors respond to. | ||

| Indicate to which extent you agree with the following statements about your company | |||

| Marketorientation | CUSTO1 | Our company objectives are driven primarily by customer satisfaction | [86,154,155] |

| CUSTO2 | We constantly monitor our level of commitment and orientation to serving customers’ needs | ||

| CUSTO3 | Our strategy for competitive advantage is based on our understanding of customers’ needs | ||

| CUSTO4 | Our company strategies are driven by our beliefs about how we can create greater value for customers | ||

| CUSTO5 | We measure customer satisfaction systematically and frequently | ||

| CUSTO6 | We give close attention to after-sales service | ||

| COMPO1 | Our salespeople regularly share information within our company concerning competitors’ strategies | ||

| COMPO2 | We rapidly respond to competitive actions that threaten us | ||

| COMPO3 | We regularly discuss competitors’ strengths and strategies | ||

| COMPO4 | We target customers where we have an opportunity for competitive advantage | ||

| Indicate to which extent you agree with the following statements about your company | |||

| Organizational ambidexterity | AL1 | The management systems of our company work coherently to support the overall objectives of the company. | [89] |

| AL2 | Employees of our company work toward the same goals because our management systems avoid conflicting objectives | ||

| AL3 | The management systems of our company prevent wastage of resources on unproductive activities. | ||

| AD1 | The management systems of our company encourage employees to challenge outmoded traditions/practices | ||

| AD2 | The management systems of our company are flexible enough to allow quick response to changes in our market. | ||

| AD3 | The management systems of our company evolve rapidly in response to shifts in our business priorities. | ||

| Indicate to which extent did your company assigned great important in the development of products/services | |||

| FrugalInnovationcapability | CF1 | Core functionality of the product rather than additional functionality | [157] |

| CF2 | Ease of product use | ||

| CF3 | The question of the durability of the product (does not spoil easily) the durability of the product | ||

| SCR1 | Solutions that offer “good-value” products | ||

| SCR2 | Cost reduction in the operational process | ||

| SCR3 | Savings of organizational resources in the operational process | ||

| SCR4 | Rearrangement of organizational resources in the operational process | ||

| SSE1 | Efficient and effective solutions to customers’ social/environmental needs | ||

| SSE2 | Environmental sustainability in the operational process | ||

| SSE3 | Partnerships with local companies in the operational process | ||

References

- Immelt, J.R.; Govindarajan, V.; Trimble, C. How GE is disrupting itself. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2009, 87, 56–65.

- Prahalad, C.K. The fortune at the bottom of the pyramid: eradicating poverty through profits; Revised and updated 5th anniversary ed.; Wharton School Pub: Upper Saddle River, N.J, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-700927-5.

- Zeschky, M.; Widenmayer, B.; Gassmann, O. Frugal Innovation in Emerging Markets. Res.-Technol. Manag. 2011, 54, 38–45. [CrossRef]

- London, T.; Hart, S.L. Reinventing strategies for emerging markets: beyond the transnational model. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2004, 35, 350–370. [CrossRef]

- Ranta, V.; Aarikka-Stenroos, L.; Väisänen, J.-M. Digital technologies catalyzing business model innovation for circular economy—Multiple case study. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 164, 105155. [CrossRef]

- LESTARI, S.D.; LEON, F.M.; WIDYASTUTI, S.; BRABO, N.A.; PUTRA, A.H.P.K. Antecedents and Consequences of Innovation and Business Strategy on Performance and Competitive Advantage of SMEs. J. Asian Finance Econ. Bus. 2020, 7, 365–378. [CrossRef]

- Nie, P.; Yang, Y. Innovation and competition with human capital input. Manag. Decis. Econ. 2023, 44, 1779–1785. [CrossRef]

- Khanna, T.; Palepu, K.G. Winning in Emerging Markets: A Road Map for Strategy and Execution; Harvard Business Press, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4221-5786-2.

- Peng, M.W.; Luo, Y.; Sun, L. Firm growth via mergers and acquisitions in China. Fish. Coll. Bus. Ohio State Univ. 1999.

- Peng, M.W.; Khoury, T.A. Unbundling the Institution-Based View of International Business Strategy. In The Oxford Handbook of International Business; Rugman, A.M., Ed.; Oxford University Press, 2008; pp. 256–268 ISBN 978-0-19-923425-7.

- Winterhoff, M.; Boehler, C. Simple, Simpler, Best: Frugal innovation in the engineered products and high tech industry. Roland Berg. Strategy Consult. 2014.

- Wooldridge, A. The world turned upside down: A special report on innovation in emerging markets; The Economist: London, 2010.

- Hossain, M. Frugal innovation: A review and research agenda. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 926–936. [CrossRef]

- Asakawa, K.; Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Un, C. Frugality-based advantage. Long Range Plann. 2019, 52. [CrossRef]

- Bernardes, R.; Borini, F.; Figueiredo, P.N. Innovation in emerging economy organizations. Cad. EBAPE BR 2019, 17, 886–894. [CrossRef]

- Weyrauch, T.; Herstatt, C. What is frugal innovation? Three defining criteria. J. Frugal Innov. 2016, 2, 1. [CrossRef]

- Lim, C.; Han, S.; Ito, H. Capability building through innovation for unserved lower end mega markets. Technovation 2013, 33, 391–404. [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.C. How disruptive is frugal? Technol. Soc. 2013, 35, 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Bhatti, Y.; Ramaswami Basu, R.; Barron, D.; Ventresca, M.J. 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press, 2018; ISBN 978-1-316-98678-3.

- Hossain, M. Frugal innovation: Conception, development, diffusion, and outcome. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 262, 121456. [CrossRef]

- Barney, J.B. Gaining and sustaining competitive advantage; 2. ed.; Prentice Hall: Upper Saddle River, NJ, 2002; ISBN 978-0-13-030794-1.

- Penrose, E.T. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm; Oxford University Press, 1959; ISBN 978-0-19-957384-4.

- Peng, M.W. Institutional Transitions and Strategic Choices. Acad. Manage. Rev. 2003, 28, 275–296. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Yim, C.K. (Bennett); Tse, D.K. The Effects of Strategic Orientations on Technology- and Market-Based Breakthrough Innovations. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 42–60. [CrossRef]

- Shivdas, A.; Barpanda, S.; Sivakumar, S.; Bishu, R. Frugal innovation capabilities: conceptualization and measurement. Prometheus 2021, 37. [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C.E.; Finkelstein, S.; Mitchell, W.; Peteraf, M.; Singh, H.; Teece, D.; Winter, S.G. Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Change in Organizations; John Wiley & Sons, 2007; ISBN 978-1-4051-8206-5.

- Griffith, D.A.; Harvey, M.G. A Resource Perspective of Global Dynamic Capabilities. J. Int. Bus. Stud. 2001, 32, 597–606. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How strategic orientations influence the building of dynamic capability in emerging economies. J. Bus. Res. 2010, 63, 224–231. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.Z.; Li, C.B. How does strategic orientation matter in Chinese firms? Asia Pac. J. Manag. 2007, 24, 447–466. [CrossRef]

- Day, G.S. The Capabilities of Market-Driven Organizations. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 37–52. [CrossRef]

- Gatignon, H.; Xuereb, J.-M. Strategic Orientation of the Firm and New Product Performance. J. Mark. Res. 1997, 34, 77–90. [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J. Organizational Ambidexterity: Antecedents, Outcomes, and Moderators. J. Manag. 2008, 34, 375–409. [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.; Amankwah-Amoah, J.; Lew, Y.K.; Puthusserry, P.; Czinkota, M. Strategic ambidexterity and its performance implications for emerging economies multinationals. Int. Bus. Rev. 2022, 31, 101762. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wood, G.; Chen, X.; Meyer, M.; Liu, Z. Strategic ambidexterity and innovation in Chinese multinational vs. indigenous firms: The role of managerial capability. Int. Bus. Rev. 2020, 29, 101652. [CrossRef]

- Birkinshaw, J.; Zimmermann, A.; Raisch, S. How Do Firms Adapt to Discontinuous Change? Bridging the Dynamic Capabilities and Ambidexterity Perspectives. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2016, 58, 36–58. [CrossRef]

- Vahlne, J.-E.; Jonsson, A. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability in the globalization of the multinational business enterprise (MBE): Case studies of AB Volvo and IKEA. Int. Bus. Rev. 2017, 26, 57–70. [CrossRef]

- Popadiuk, S.; Luz, A.R.S.; Kretschmer, C. Dynamic Capabilities and Ambidexterity: How are These Concepts Related? Rev. Adm. Contemp. 2018, 22, 639–660. [CrossRef]

- Tidd, J.; Bessant, J.R. Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change; John Wiley & Sons, 2009; ISBN 978-1-119-71330-2.

- Wang, C.L.; Ahmed, P.K. Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 31–51. [CrossRef]

- Voss, G.B.; Voss, Z.G. Strategic Orientation and Firm Performance in an Artistic Environment. J. Mark. 2000, 64, 67–83. [CrossRef]

- Benitez, J.; Castillo, A.; Llorens, J.; Braojos, J. IT-enabled knowledge ambidexterity and innovation performance in small U.S. firms: The moderator role of social media capability. Inf. Manage. 2018, 55, 131–143. [CrossRef]

- Han, W.; Zhou, Y.; Lu, R. Strategic orientation, business model innovation and corporate performance—Evidence from construction industry. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13. [CrossRef]

- Hult, G.T.M.; Hurley, R.F.; Knight, G.A. Innovativeness: Its antecedents and impact on business performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2004, 33, 429–438. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Coelho, A.; Moutinho, L. Dynamic capabilities, creativity and innovation capability and their impact on competitive advantage and firm performance: The moderating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Technovation 2020, 92–93, 102061. [CrossRef]

- Reinhardt, R.; Gurtner, S.; Griffin, A. Towards an adaptive framework of low-end innovation capability – A systematic review and multiple case study analysis. Long Range Plann. 2018, 51, 770–796. [CrossRef]

- Rosca, E.; Arnold, M.; Bendul, J.C. Business models for sustainable innovation – an empirical analysis of frugal products and services. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, S133–S145. [CrossRef]

- Grawe, S.J.; Chen, H.; Daugherty, P.J. The relationship between strategic orientation, service innovation, and performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 282–300. [CrossRef]

- Tutar, H.; Nart, S.; Bingöl, D. The Effects of Strategic Orientations on Innovation Capabilities and Market Performance: The Case of ASEM. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 207, 709–719. [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.C.; Gomes, G.; Borini, F.M. Exploring the antecedents of frugal innovation and operational performance: the role of organizational learning capability and entrepreneurial orientation. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Berndt, A.C.; Gomes, G.; Borini, F.M.; Bernardes, R.C. Frugal innovation and operational performance: the role of organizational learning capability. RAUSP Manag. J. 2023, 58, 233–248. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Ying, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wu, W. Innovating with Limited Resources: The Antecedents and Consequences of Frugal Innovation. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5789. [CrossRef]

- Santos, L.L.; Borini, F.M.; Oliveira, M. de M.; Rossetto, D.E.; Bernardes, R.C. Bricolage as capability for frugal innovation in emerging markets in times of crisis. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 25, 413–432. [CrossRef]

- Winterhalter, S.; Zeschky, M.B.; Neumann, L.; Gassmann, O. Business Models for Frugal Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Case of the Medical Device and Laboratory Equipment Industry. Technovation 2017, 66–67, 3–13. [CrossRef]

- Dost, M.; Pahi, M.H.; Magsi, H.B.; Umrani, W.A. Effects of sources of knowledge on frugal innovation: moderating role of environmental turbulence. J. Knowl. Manag. 2019, 23, 1245–1259. [CrossRef]

- Rao, B.C. The science underlying frugal innovations should not be frugal. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2019, 6, 180421. [CrossRef]

- Weyrauch, T.; Herstatt, C. What is frugal innovation? Three defining criteria. J. Frugal Innov. 2017, 2, 1. [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. How Frugal Innovation Promotes Social Sustainability. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1034. [CrossRef]

- Pisoni, A.; Michelini, L.; Martignoni, G. Frugal approach to innovation: State of the art and future perspectives. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 107–126. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R. A conceptual model of frugal innovation: is environmental munificence a missing link? Int. J. Innov. Sci. 2017, 9, 320–334. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Kalogerakis, K.; Herstatt, C. Frugal innovations in the mirror of scholarly discourse: Tracing theoretical basis and antecedents. In R&D Management Conference, Cambridge, UK. Available online: https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=Frugal%20Innovations%20in%20the%20Mirror%20of%20Scholarly%20Discourse%3A%20Tracing%20Theoretical%20Basis%20and%20Antecedents&author=R.%20Tiwari&publication_year=2016 (accessed on Oct 26, 2023).

- Agarwal, N.; Brem, A. Frugal and reverse innovation - Literature overview and case study insights from a German MNC in India and China. In Proceedings of the Technology and Innovation 2012 18th International ICE Conference on Engineering; 2012; pp. 1–11.

- Brem, A.; Ivens, B. Do Frugal and Reverse Innovation Foster Sustainability? Introduction of a Conceptual Framework. J. Technol. Manag. Grow. Econ. 2013, 4, 31–50. [CrossRef]

- Yasser Ahmad Bhatti What is Frugal, What is Innovation? Towards a Theory of Frugal Innovation. SSRN Electron. J. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Mourtzis, D. Design of customised products and manufacturing networks: towards frugal innovation. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2018, 31, 1161–1173. [CrossRef]

- Parashar, M.; Singh, S.K. Innovation capability. IIMB Manag. Rev. 2005, 17, 115–123.

- Teece, D.J.; Pisano, G.; Shuen, A. Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1997, 18, 509–533. [CrossRef]

- Greeven, M. Innovation in an Uncertain Institutional Environment: Private Software Entrepreneurs in Hangzhou, China; 2009; ISBN 978-90-5892-202-1.

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. Crafting High-Impact Entrepreneurial Orientation Research: Some Suggested Guidelines. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2019, 43, 3–18. [CrossRef]

- Hakala, H. Strategic Orientations in Management Literature: Three Approaches to Understanding the Interaction between Market, Technology, Entrepreneurial and Learning Orientations: Orientations in Management Literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2011, 13, 199–217. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, G.; Whittington, R.; Angwin, D.; Regnèr, P.; Scholes, K. Exploring Strategy; Pearson, 2014; ISBN 978-1-292-00701-4.

- O’Regan, N.; Ghobadian, A. Innovation in SMEs: the impact of strategic orientation and environmental perceptions. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2005, 54, 81–97. [CrossRef]

- Franczak, J.; Weinzimmer, L.; Michel, E. An empirical examination of strategic orientation and SME performance. Small Bus. Inst. Natl. Proc. 2009, 33.

- Storey, C.; Hughes, M. The relative impact of culture, strategic orientation and capability on new service development performance. Eur. J. Mark. 2013, 47, 833–856. [CrossRef]

- Baker, W.; Sinkula, J. The Complementary Effect of Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Orientation on Innovation Success and Profitability. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2006, 47, 443–464. [CrossRef]

- Indriyani, R.; Suprapto, W.; Calista, J. Market Orientation and Innovation: The Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation among Traditional Snack Entrepreneurs in Sanan, Malang, Indonesia: In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Inclusive Business in the Changing World; SCITEPRESS - Science and Technology Publications: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2019; pp. 246–253.

- Lin, C.-W.; Cheng, L.K.; Wu, L.-Y. Roles of strategic orientations in radical product innovation. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2020, 39, 33–47. [CrossRef]

- Sahi, G.K.; Gupta, M.C.; Cheng, T.C.E. The effects of strategic orientation on operational ambidexterity: A study of indian SMEs in the industry 4.0 era. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2020, 220, 107395. [CrossRef]

- Rauch, A.; Wiklund, J.; Lumpkin, G.T.; Frese, M. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Business Performance: An Assessment of past Research and Suggestions for the Future. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2009, 33, 761–787. [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Wales, W.J. The Measurement of Entrepreneurial Orientation. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2012, 36, 677–702. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D.; Friesen, P.H. Archetypes of Strategy Formulation. Manag. Sci. 1978, 24, 921–933. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.S.; Kreiser, P.M.; Kuratko, D.F.; Hornsby, J.S.; Eshima, Y. Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial orientation. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1579–1596. [CrossRef]

- Di Zhang, D.; Bruning, E. Personal characteristics and strategic orientation: entrepreneurs in Canadian manufacturing companies. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2011, 17, 82–103. [CrossRef]

- Aljanabi, A.R.A. The mediating role of absorptive capacity on the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and technological innovation capabilities. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2017, 24, 818–841. [CrossRef]

- Makhloufi, L.; Laghouag, A.A.; Ali Sahli, A.; Belaid, F. Impact of Entrepreneurial Orientation on Innovation Capability: The Mediating Role of Absorptive Capability and Organizational Learning Capabilities. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5399. [CrossRef]

- Sulistyo, H.; Ayuni, S. Competitive advantages of SMEs: The roles of innovation capability, entrepreneurial orientation, and social capital. Contad. Adm. 2019, 65, 156. [CrossRef]

- Narver, J.C.; Slater, S.F. The Effect of a Market Orientation on Business Profitability. J. Mark. 1990, 54, 20–35. [CrossRef]

- Jaworski, B.J.; Kohli, A.K. Market Orientation: Antecedents and Consequences. J. Mark. 1993, 57, 53–70. [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Jing, L. Strategic orientation and performance of new ventures: empirical studies based on entrepreneurial activities in China. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2017, 13, 989–1012. [CrossRef]

- Ed-Dafali, S.; Al-Azad, Md.S.; Mohiuddin, M.; Reza, M.N.H. Strategic orientations, organizational ambidexterity, and sustainable competitive advantage: Mediating role of industry 4.0 readiness in emerging markets. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 401, 136765. [CrossRef]

- Raisch, S.; Birkinshaw, J.; Probst, G.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity: Balancing Exploitation and Exploration for Sustained Performance. Organ. Sci. 2009, 20, 685–695. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Terjesen, S.; Li, D. Enhancing effects of manufacturing flexibility through operational absorptive capacity and operational ambidexterity. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 201–220. [CrossRef]

- Jurksiene, L.; Pundziene, A. The relationship between dynamic capabilities and firm competitive advantage: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2016, 28, 431–448. [CrossRef]

- March, J.G. Exploration and Exploitation in Organizational Learning. Organ. Sci. 1991, 2, 71–87. [CrossRef]

- Tortorella, G.; Miorando, R.; Caiado, R.; Nascimento, D.; Portioli Staudacher, A. The mediating effect of employees’ involvement on the relationship between Industry 4.0 and operational performance improvement. Total Qual. Manag. Bus. Excell. 2021, 32, 119–133. [CrossRef]

- Ghantous, N.; Alnawas, I. The differential and synergistic effects of market orientation and entrepreneurial orientation on hotel ambidexterity. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102072. [CrossRef]

- Gibson, C.B.; Birkinshaw, J. The Antecedents, Consequences, and Mediating Role of Organizational Ambidexterity. Acad. Manage. J. 2004, 47, 209–226. [CrossRef]

- Alpkan, L. ütfihak; Şanal, M.; Ayden, Y. üksel Market Orientation, Ambidexterity and Performance Outcomes. Procedia - Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 41, 461–468. [CrossRef]

- Belhadi, A.; Kamble, S.; Gunasekaran, A.; Mani, V. Analyzing the mediating role of organizational ambidexterity and digital business transformation on industry 4.0 capabilities and sustainable supply chain performance. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2021, 27, 696–711. [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J.; Kraus, S.; Filser, M.; Stöckmann, C.; Covin, J.G. The status quo of research on entrepreneurial orientation: Conversational landmarks and theoretical scaffolding. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 128, 564–577. [CrossRef]

- Kiyabo, K.; Isaga, N. Entrepreneurial orientation, competitive advantage, and SMEs’ performance: application of firm growth and personal wealth measures. J. Innov. Entrep. 2020, 9, 12. [CrossRef]

- Khedhaouria, A.; Nakara, W.A.; Gharbi, S.; Bahri, C. The Relationship between Organizational Culture and Small-firm Performance: Entrepreneurial Orientation as Mediator. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2020, 17, 515–528. [CrossRef]

- Covin, J.G.; Miller, D. International Entrepreneurial Orientation: Conceptual Considerations, Research Themes, Measurement Issues, and Future Research Directions. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2014, 38, 11–44. [CrossRef]

- Wales, W.J.; Gupta, V.K.; Mousa, F.-T. Empirical research on entrepreneurial orientation: An assessment and suggestions for future research. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 357–383. [CrossRef]

- Slater, S.F.; Narver, J.C. Market Orientation and the Learning Organization. J. Mark. 1995, 59, 63–74. [CrossRef]

- Alegre, J.; Chiva, R. Linking Entrepreneurial Orientation and Firm Performance: The Role of Organizational Learning Capability and Innovation Performance. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 491–507. [CrossRef]

- Jayawarna, D.; Rouse, J.; Kitching, J. Entrepreneur motivations and life course. Int. Small Bus. J. 2013, 31, 34–56. [CrossRef]

- Otero-Neira, C.; Arias, M.J.F.; Lindman, M.T. Market Orientation and Entrepreneurial Proclivity: Antecedents of Innovation. Glob. Bus. Rev. 2013, 14, 385–395. [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.R.; Drakopoulou Dodd, S.; Jack, S.L. Entrepreneurship as connecting: some implications for theorising and practice. Manag. Decis. 2012, 50, 958–971. [CrossRef]

- Hughes, M.; Morgan, R.E. Deconstructing the relationship between entrepreneurial orientation and business performance at the embryonic stage of firm growth. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2007, 36, 651–661. [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G.T.; Dess, G.G. Clarifying the Entrepreneurial Orientation Construct and Linking It to Performance. Acad. Manage. Rev. 1996, 21, 135. [CrossRef]

- Montoya-Weiss, M.M.; Calantone, R. Determinants of new product performance: A review and meta-analysis. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1994, 11, 397–417. [CrossRef]

- Akman, G.; Yilmaz, C. Innovative capability, innovation strategy and market orientation: an empirical analysis in turkish software industry. Int. J. Innov. Manag. 2008, 12, 69–111. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.K.; Kim, N.; Srivastava, R.K. Market Orientation and Organizational Performance: Is Innovation a Missing Link? J. Mark. 1998, 62, 30–45. [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K.; Ko, A. An Empirical Investigation of the Effect of Market Orientation and Entrepreneurship Orientation Alignment on Product Innovation. Organ. Sci. 2001, 12, 54–74. [CrossRef]

- Aziz, N.A.; Omar, N.A. Exploring the effect of Internet marketing orientation, Learning Orientation and Market Orientation on innovativeness and performance: SME (exporters) perspectives. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2013, 14, S257–S278. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.; Kim, K. The role of learning capability in market-oriented firms in the context of open innovation-based technology acquisition: empirical evidence from the Korean manufacturing sector. Int. J. Technol. Manag. 2016, 70, 135–156. [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K. An Exploratory Analysis of the Impact of Market Orientation on New Product Performance. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1995, 12, 275–293. [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Su, J. How does market orientation affect product innovation in China’s manufacturing industry: The contingent value of dynamic capabilities. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2013 Conference on Education Technology and Management Science; Atlantis Press: Nanjing, China, 2013.

- Posch, A.; Garaus, C. Boon or curse? A contingent view on the relationship between strategic planning and organizational ambidexterity. Long Range Plann. 2020, 53, 101878. [CrossRef]

- Tuan, L.T. Organizational Ambidexterity, Entrepreneurial Orientation, and I-Deals: The Moderating Role of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 135, 145–159. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.A.; Edgar, F.; Geare, A.; O’Kane, C. The interactive effects of entrepreneurial orientation and capability-based HRM on firm performance: The mediating role of innovation ambidexterity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 59, 131–143. [CrossRef]

- Sirmon, D.G.; Barney, J.B.; Ketchen, D.J.; Wright, M.; Hitt, M.A.; Ireland, R.D.; Gilbert, B.A. Resource Orchestration to Create Competitive Advantage: Breadth, Depth, and Life Cycle Effects. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1390–1412. [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S.; Krishna Erramilli, M.; Dev, C.S. Market orientation and performance in service firms: role of innovation. J. Serv. Mark. 2003, 17, 68–82. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.C.; Krumwiede, D. The role of service innovation in the market orientation—new service performance linkage. Technovation 2012, 32, 487–497. [CrossRef]

- Gotteland, D.; Shock, J.; Sarin, S. Strategic orientations, marketing proactivity and firm market performance. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 91, 610–620. [CrossRef]

- Atuahene-Gima, K. Resolving the Capability–Rigidity Paradox in New Product Innovation. J. Mark. 2005, 69, 61–83. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-L.; Wong, P.-K. Exploration vs. Exploitation: An Empirical Test of the Ambidexterity Hypothesis. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 481–494. [CrossRef]

- Clauss, T.; Kraus, S.; Kallinger, F.L.; Bican, P.M.; Brem, A.; Kailer, N. Organizational ambidexterity and competitive advantage: The role of strategic agility in the exploration-exploitation paradox. J. Innov. Knowl. 2021, 6, 203–213. [CrossRef]

- Preda, G. ORGANIZATIONAL AMBIDEXTERITY AND COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE: TOWARD A RESEARCH MODEL. Manag. Amp Mark. - Craiova 2014, 67–74.

- van Lieshout, J.W.F.C.; van der Velden, J.M.; Blomme, R.J.; Peters, P. The interrelatedness of organizational ambidexterity, dynamic capabilities and open innovation: a conceptual model towards a competitive advantage. Eur. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 26, 39–62. [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, A.; Krishnan, T.N.; Upadhyayula, R.S.; Kumar, M. Finding the microfoundations of organizational ambidexterity - Demystifying the role of top management behavioural integration. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 106, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Chen, J. International ambidexterity in firms’ innovation of multinational enterprises from emerging economies: an investigation of TMT attributes. Balt. J. Manag. 2020, 15, 431–451. [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Luan, R.; Wu, H.-H.; Zhu, W.; Pang, J. Ambidextrous balance and channel innovation ability in Chinese business circles: The mediating effect of knowledge inertia and guanxi inertia. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2021, 93, 63–75. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Pickernell, D.; Battisti, M.; Soetanto, D.; Huang, Q. When is entrepreneurial orientation beneficial for new product performance? The roles of ambidexterity and market turbulence. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2020, 27, 79–98. [CrossRef]

- Nofiani, D.; Indarti, N.; Lukito-Budi, A.S.; Manik, H.F.G.G. The dynamics between balanced and combined ambidextrous strategies: a paradoxical affair about the effect of entrepreneurial orientation on SMEs’ performance. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2021, 13, 1262–1286. [CrossRef]

- Patel, P.C.; Kohtamäki, M.; Parida, V.; Wincent, J. Entrepreneurial orientation-as-experimentation and firm performance: The enabling role of absorptive capacity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2015, 36, 1739–1749. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D. Knowledge-based resources, entrepreneurial orientation, and the performance of small and medium-sized businesses. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 1307–1314. [CrossRef]

- Aren, S.; Şanal, M.; Alpkan, L.; Sezen, B.; Ayden, Y. Linking Market Orientation and Ambidexterity to Financial Returns with the Mediation of Innovative Performance. J. Econ. Soc. Res. 2013, 15, 31–54.

- Enkel, E.; Heil, S.; Hengstler, M.; Wirth, H. Exploratory and exploitative innovation: To what extent do the dimensions of individual level absorptive capacity contribute? Technovation 2017, 60–61, 29–38. [CrossRef]

- van Welie, M.J.; Truffer, B.; Gebauer, H. Innovation challenges of utilities in informal settlements: Combining a capabilities and regime perspective. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2019, 33, 84–101. [CrossRef]

- Lapersonne, A.; Sanghavi, N.; De Mattos, C. Hybrid Strategy, ambidexterity and environment: toward an integrated typology. Univers. J. Manag. 2015, 3, 497–508. [CrossRef]

- Herzallah, A.; Gutierrez-Gutierrez, L.J.; Munoz Rosas, J.F. Quality ambidexterity, competitive strategies, and financial performance: An empirical study in industrial firms. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2017, 37, 1496–1519. [CrossRef]

- Morelos Gómez, J.; Vargas Franco, D.; Romero Sánchez, G. The outstanding relevance of frugal innovation in the manufacturing sector of emerging economies. | Revista Electrónica Gestión de las Personas y Tecnologías | EBSCOhost Available online: https://openurl.ebsco.com/contentitem/doi:10.35588%2Fgpt.v16i48.6507?sid=ebsco:plink:crawler&id=ebsco:doi:10.35588%2Fgpt.v16i48.6507 (accessed on Mar 18, 2024).

- ITA Tanzania - Manufacturing Available online: https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/tanzania-manufacturing (accessed on Mar 19, 2024).

- Nyello, R.M.; Kalufya, N. Entrepreneurial Orientations and Business Financial Performance: The Case of Micro Businesses in Tanzania. Open J. Bus. Manag. 2021, 9, 1263–1290. [CrossRef]

- URT Small and Medium Enterprise Development Policy 2003.

- Fielding, N.; M.Lee, R.; Blank, G. The SAGE Handbook of Online Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Ltd, 2008; ISBN 978-0-85702-005-5.

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4.

- F. Hair Jr, J.; Sarstedt, M.; Hopkins, L.; G. Kuppelwieser, V. Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): An emerging tool in business research. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2014, 26, 106–121. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J. Multivariate Data Analysis: A Global Perspective; Pearson Education, 2010; ISBN 978-0-13-515309-3.

- Kline, R.B. Software Review: Software Programs for Structural Equation Modeling: Amos, EQS, and LISREL. J. Psychoeduc. Assess. 1998, 16, 343–364. [CrossRef]

- Macfie, H.J.; Bratchell, Nicholas.; Greenhoff, Keith.; Vallis, L.V. DESIGNS TO BALANCE THE EFFECT OF ORDER OF PRESENTATION AND FIRST-ORDER CARRY-OVER EFFECTS IN HALL TESTS. J. Sens. Stud. 1989, 4, 129–148. [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM: A Full Collinearity Assessment Approach. Int. J. E-Collab. IJeC 2015, 11, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Farooq, R.; Vij, S. Toward the measurement of market orientation: scale development and validation. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 45, 1275–1295. [CrossRef]

- Siguaw, J.; A, J.; Diamantopoulos, A. Measuring Market Orientation: Some Evidence on Narver and Slater’s Three-Component Scale. J. Strateg. Mark. 1995, 3, 77–88. [CrossRef]

- Ward, S.; Girardi, A.; Lewandowska, A. A Cross-National Validation of the Narver and Slater Market Orientation Scale. J. Mark. Theory Pract. 2006, 14, 155–167. [CrossRef]

- Rossetto, D.E.; Borini, F.M.; Bernardes, R.C.; Frankwick, G.L. Measuring frugal innovation capabilities: An initial scale proposition. Technovation 2023, 121, 102674. [CrossRef]

- Ringle, C.; Wende, S.; Becker, J.-M. “SmartPLS 4.” Oststeinbek: SmartPLS GmbH, Available online: https://www.smartpls.com/ (accessed on Nov 3, 2023).

- Anderson, J.C.; Gerbing, D.W. Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 1988, 103, 411–423. [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, J.-B. Predictive vs. Structural Modeling: PLS vs. ML. In Latent Variable Path Modeling with Partial Least Squares; Physica-Verlag HD: Heidelberg, 1989; pp. 199–226 ISBN 978-3-642-52514-8.

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM); 2nd ed.; SAGE Publications, Incorporated: Thousand Oaks, 2016; ISBN 978-1-4833-7743-8.

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Danks, N.P.; Ray, S. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) Using R: A Workbook; Classroom Companion: Business; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-80518-0.

- Jr, J.F.H.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P. Advanced Issues in Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; SAGE Publications, 2017; ISBN 978-1-4833-7739-1.

- Aguirre-Urreta, M.; Rönkkö, M. Statistical Inference with PLSc Using Bootstrap Confidence Intervals. MIS Q. 2018, 42. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M.; Thiele, K.O. Mirror, mirror on the wall: A comparative evaluation of composite-based structural equation modeling methods. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2017, 45, 616–632. [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39. [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling. In Handbook of Market Research; Homburg, C., Klarmann, M., Vomberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2022; pp. 587–632 ISBN 978-3-319-57411-0.

- Hair, J.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling; Third edition.; SAGE Publications, Inc: Los Angeles London New Delhi Singapore Washington DC Melbourne, 2021; ISBN 978-1-5443-9640-8.

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; 0 ed.; Routledge, 1988; ISBN 978-1-134-74270-7.

- Chin, W.W. The Partial Least Squares Approach to Structural Equation Modeling. In Modern methods for business research; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Hillsdale, NJ, 1998; pp. 295–336.

- Tenenhaus, M.; Vinzi, V.E.; Chatelin, Y.-M.; Lauro, C. PLS path modeling. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2005, 48, 159–205. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Lynch, J.G.; Chen, Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and Truths about Mediation Analysis. J. Consum. Res. 2010, 37, 197–206. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Song, T.H.; Yoo, S. Paths to Success: How Do Market Orientation and Entrepreneurship Orientation Produce New Product Success? J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2013, 30, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Mohammad, I.N.; Massie, J.D.D.; Tumewu, F.J. THE EFFECT OF ENTREPRENEURIAL ORIENTATION AND INNOVATION CAPABILITY TOWARDS FIRM PERFORMANCE IN SMALL AND MEDIUM ENTERPRISES (Case Study: Grilled Restaurants in Manado). J. EMBA J. Ris. Ekon. Manaj. Bisnis Dan Akunt. 2019, 7. [CrossRef]

- Ribau, C.P.; Moreira, A.C.; Raposo, M. The role of exploitative and exploratory innovation in export performance: an analysis of plastics industry SMEs. Eur. J Int. Manag. 2019, 13, 224. [CrossRef]

- Cuevas-Vargas, H.; Parga-Montoya, N. How ICT usage affect frugal innovation in Mexican small firms. The mediating role of entrepreneurial orientation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 199, 223–230. [CrossRef]

- Aydin, H. Market orientation and product innovation: the mediating role of technological capability. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020, 24, 1233–1267. [CrossRef]

- Didonet, S.R.; Simmons, G.; Díaz-Villavicencio, G.; Palmer, M. Market Orientation’s Boundary-Spanning Role to Support Innovation in SMEs. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 216–233. [CrossRef]

- Cuervo-Cazurra, A.; Carneiro, J.; Finchelstein, D.; Duran, P.; Gonzalez-Perez, M.A.; Montoya, M.A.; Borda Reyes, A.; Fleury, M.T.L.; Newburry, W. Uncommoditizing strategies by emerging market firms. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2018, 27, 141–177. [CrossRef]

- Kolbe, D.; Frasquet, M.; Calderon, H. The role of market orientation and innovation capability in export performance of small- and medium-sized enterprises: a Latin American perspective. Multinatl. Bus. Rev. 2022, 30, 289–312. [CrossRef]

- Rosenbusch, N.; Rauch, A.; Bausch, A. The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Task Environment–Performance Relationship: A Meta-Analysis. J. Manag. 2013, 39, 633–659. [CrossRef]

- Lisboa, A.; Skarmeas, D.; Saridakis, C. Entrepreneurial orientation pathways to performance: A fuzzy-set analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 1319–1324. [CrossRef]

- Wiklund, J.; Shepherd, D.A. Where to from Here? EO-as-Experimentation, Failure, and Distribution of Outcomes. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2011, 35, 925–946. [CrossRef]

- Luger, J.; Raisch, S.; Schimmer, M. Dynamic Balancing of Exploration and Exploitation: The Contingent Benefits of Ambidexterity. Organ. Sci. 2018, 29, 449–470. [CrossRef]

- S. Kraft, P.; Bausch, A. How Do Transformational Leaders Promote Exploratory and Exploitative Innovation? Examining the Black Box through MASEM. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2016, 33, 687–707. [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Liu, Z. Paths to success: an ambidexterity perspective on how responsive and proactive market orientations affect SMEs’ business performance. J. Strateg. Mark. 2014, 22, 420–441. [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C.A.; Tushman, M.L. Organizational Ambidexterity in Action: How Managers Explore and Exploit. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2011, 53, 5–22. [CrossRef]

- Kusumastuti, R.; Safitri, N.; Khafian, N. Developing Innovation Capability of SME through Contextual Ambidexterity. Bisnis Birokrasi J. 2016, 22, 51–59. [CrossRef]

- Al-khawaldah, R.A.; Al-zoubi, W.K.; Alshaer, S.A.; Almarshad, M.N.; ALShalabi, F.S.; Altahrawi, M.H.; Al-hawary, S.I. Green supply chain management and competitive advantage: The mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Uncertain Supply Chain Manag. 2022, 10, 961–972. [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.-W.; Li, Y.-H. The mediating role of ambidextrous capability in learning orientation and new product performance. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 613–624. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, C. Organizational ambidexterity, market orientation, and firm performance. J. Eng. Technol. Manag. 2014, 33, 134–153. [CrossRef]

- Masa’deh, R.; Al-Henzab, J.; Tarhini, A.; Obeidat, B.Y. The associations among market orientation, technology orientation, entrepreneurial orientation and organizational performance. Benchmarking Int. J. 2018, 25, 3117–3142. [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Prijadi, R.; Kusumastuti, R.D. Strategic orientations and firm performance: the role of information technology adoption capability. J. Strategy Manag. 2022, 15, 691–717. [CrossRef]

- Prifti, R.; Alimehmeti, G. Market orientation, innovation, and firm performance—an analysis of Albanian firms. J. Innov. Entrep. 2017, 6, 8. [CrossRef]

- Soares, M. do C.; Perin, M.G. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: an updated meta-analysis. RAUSP Manag. J. 2020, 55, 143–159. [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, Q.; Ahmad, N.H.; Li, Z. Frugal-based innovation model for sustainable development: technological and market turbulence. Leadersh. Organ. Dev. J. 2021, 42, 396–407. [CrossRef]

- D’Angelo, V.; Magnusson, M. A bibliometric map of intellectual communities in frugal innovation literature. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2020, 68, 653–666. [CrossRef]

| Characteristics | Frequency | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 243 | 62.95 |

| Female | 143 | 37.05 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Years of services in the current organization | ||

| 1 to 3 years | 113 | 29.27 |

| 4 to 6 years | 205 | 53.11 |

| more than 6 years | 68 | 17.62 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Designation | ||

| Owner/CEO/General Manager | 158 | 40.93 |

| Production/ Operations Manager | 80 | 20.73 |

| Marketing Manager | 74 | 19.17 |

| Finance Manager | 39 | 10.1 |

| HR Manager | 35 | 9.07 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Firm sub-sector in Manufacturing industry | ||

| Fashion (Textile, footwear and apparel) | 125 | 32.38 |

| Food (Food processing, alcoholic & non-alcoholic beverage, dairy products) | 133 | 34.46 |

| Furniture and fittings, plastic, chemical and metal products | 128 | 33.16 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Number of years since establishment | ||

| Below 5 | 110 | 28.5 |

| Between 5 to 10 | 176 | 45.6 |

| Above10 | 100 | 25.91 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Firm location | ||

| Dar es Salaam city | 248 | 64.25 |

| Arusha city | 138 | 35.75 |

| Total | 386 | 100 |

| Constructs | Items | Loading | Cronbach’s Alpha (α) | rho_A | Composite reliability (CR) | (AVE) | VIF |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | EO1 | 0.835 | 0.942 | 0.944 | 0.951 | 0.684 | 2.703 |

| EO2 | 0.830 | 2.576 | |||||

| EO3 | 0.832 | 2.743 | |||||

| EO4 | 0.855 | 2.931 | |||||

| EO5 | 0.825 | 2.604 | |||||

| EO6 | 0.804 | 2.457 | |||||

| EO7 | 0.815 | 2.485 | |||||

| EO8 | 0.842 | 2.804 | |||||

| EO9 | 0.804 | 2.371 | |||||

| Market orientation | MO1 | 0.761 | 0.936 | 0.936 | 0.946 | 0.636 | 2.040 |

| MO2 | 0.803 | 2.347 | |||||

| MO3 | 0.811 | 2.460 | |||||

| MO4 | 0.840 | 2.805 | |||||

| MO5 | 0.793 | 2.333 | |||||

| MO6 | 0.822 | 2.700 | |||||

| MO7 | 0.836 | 2.814 | |||||

| MO8 | 0.794 | 2.469 | |||||

| MO9 | 0.805 | 2.476 | |||||

| MO10 | 0.704 | 1.691 | |||||

| Organizational ambidexterity | AD1 | 0.803 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.910 | 0.626 | 2.117 |

| AD2 | 0.772 | 1.855 | |||||

| AD3 | 0.786 | 1.982 | |||||

| AL1 | 0.798 | 2.138 | |||||

| AL2 | 0.809 | 2.142 | |||||

| AL3 | 0.780 | 1.947 | |||||

| Core functionality | CF1 | 0.891 | 0.866 | 0.866 | 0.918 | 0.788 | 2.258 |

| CF2 | 0.884 | 2.204 | |||||

| CF3 | 0.888 | 2.260 | |||||

| Substantial cost reduction | SCR1 | 0.878 | 0.881 | 0.881 | 0.910 | 0.626 | 2.249 |

| SCR2 | 0.894 | 2.316 | |||||

| SCR3 | 0.852 | 1.786 | |||||

| Sustainable shared engagement | SSE1 | 0.893 | 0.907 | 0.909 | 0.935 | 0.781 | 2.869 |

| SSE2 | 0.856 | 2.313 | |||||

| SSE3 | 0.906 | 3.044 | |||||

| SSE4 | 0.880 | 2.610 |

| CF | EO | MO | OA | SCR | SSE | |

| CF | 0.815 | |||||

| EO | 0.673 | 0.804 | ||||

| MO | 0.694 | 0.565 | 0.766 | |||

| OA | 0.699 | 0.636 | 0.579 | 0.81 | ||

| SCR | 0.618 | 0.523 | 0.689 | 0.525 | 0.863 | |

| SSE | 0.675 | 0.689 | 0.587 | 0.571 | 0.652 | 0.794 |

| Construct | R-square | Q-square | R-square adjusted |

| Frugal innovation capability | 0.818 | 0.660 | 0.817 |

| Organizational ambidexterity | 0.560 | 0.466 | 0.557 |

| Hypothesis | Path | Beta Coefficients (β) | T statistics (t-value) | p-values | Results |

| H1a | EO → FIC | 0.219 | 3.598 | 0.000*** | Supported |

| H1b | MO → FIC | 0.252 | 3.962 | 0.000*** | Supported |

| H2a | EO → OA | 0.292 | 3.070 | 0.002*** | Supported |

| H2b | MO → OA | 0.506 | 5.224 | 0.000*** | Supported |

| H3 | OA → FIC | 0.529 | 7.799 | 0.000*** | Supported |

| Second Order Construct (Frugal innovation capability) | |||||

| CF → FIC | 0.833 | 24.922 | 0.000*** | ||

| SCR → FIC | 0.861 | 36.918 | 0.000*** | ||

| SSE → FIC | 0.890 | 24.675 | 0.000*** | ||

| Hypothesis | Path | Beta Coefficients (β) | T statistics (t-value) | p-values | Confidence interval | Decision | |

| 0.025 | 0.975 | ||||||

| H4a | EO → OA → FIC | 0.155 | 2.944 | 0.003 | 0.052 | 0.258 | Supported |

| H4b | MO → OA → FIC | 0.268 | 4.204 | 0.000 | 0.151 | 0.403 | Supported |

| Variance Accounted for (VAF) of the Mediator Variable for OA | |||||||

| IVs | Mediator | DV | Indirect effect | Total effect | VAF (%) | Type of mediation | |

| EO | OA | FIC | 0.155 | 0.373 | 41.6 | Partial complementary | |

| MO | OA | FIC | 0.268 | 0.520 | 51.5 | Partial complementary | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).