1. Introduction

The use of colour in interior architecture is a crucial factor that affects the user experience within the spaces they occupy most (homes, offices, schools, etc.). Numerous research studies have demonstrated the effects of individual colours, colour combinations, and their interaction with other architectural elements (such as materials) on the interior experience. Besides the shapes on interior walls also contribute significantly to the overall user experience. Shape associations have been of interest to many disciplines, and interesting phenomena were recorded, such as bouba-kiki effect, in which ‘non-word names are assigned to abstract shapes in systematic ways (e.g., rounded shapes are preferentially labelled bouba over kiki)’ (Cuskley et al., 2017, p. 119). The relationship between colours and basic shapes is a well-studied area in psychology, with numerous researchers exploring the topic (Bar & Neta, 2006; Albertazzi et al., 2013; Makin & Wuerger, 2013). Although colour-shape preferences have not yet been explored in interior architecture, they have been of interest to the art and design fields. Wassily Kandinsky, a Russian artist, who conducted his studies in Bauhaus (Albertazzi et al., 2013), proposed a correspondence theory based on his empirical-spiritual experiments (Kharkhurin, 2012). He believed in an inner necessity that there is a natural connection between primary colours and shapes such as triangles, squares, and circles due to their angles: specifically, he associates acute angles with warmth, right angles with coolness, and obtuse angles with coldness (Kharkhurin, 2012). According to this Bauhaus artist, the colours associated with geometric shapes are yellow for triangles, red for squares, and blue for circles based on their angles (Kharkhurin, 2012). Makin and Wuerger (2013) stated that Kandinsky’s associations became even more integrated into Bauhaus due to the inclusion of a yellow triangle, a red square, and a blue circle in its poster, which was developed by Herbert Bayer (exhibited in Stuttgart in 1968).

Chen et al. (2015a) suggest that colour-shape associations are rooted in universal and cultural components. It is not hard to agree that the sun is associated with yellow as a universal component, or maybe orange or red (Fox, 2021), an example of ecological basis and world knowledge for colour-shape associations. Jacobsen (2002, p. 911) mentioned everyday world knowledge associations such as warning sign-red triangle and sun-yellow circle and indicated that there are no cardinal rules we can generalise over generations and for different cultures. For instance, traffic signs were unavailable in 1923 for Kandinsky’s participants; however, today, they are ‘in primary colours, internationally standardised, and omnipresent’ (Jacobsen, 2002, p.912). Since it is essential for life, the sun can be visually available for the next generations, but such associations are limited. Even the most fundamental colour-shape associations might be questionable. Therefore, they should be studied within their respective cultures. Moreover, like the meaning of white in the West (purity) vs India (mourning) (Holtzschue, 2006), many colour associations are learned associations and are related to the culture; thus, colour-shape associations are affected by universal and cultural components of human experience. They can also be sourced from very cultural components and an association shared by a small group of people like art students at a school. For instance, Albertazzi et al. (2013) stated that Kandinsky conducted his experiments on the Bauhaus population, who were avant-garde elite artists (Jacobsen, 2002) and were familiar with his correspondence theory (Kharkhurin, 2012). Kharkhurin (2012) discussed several empirical studies and showed that although non-specialists (non-experts) and art professionals (experts) unfamiliar with Kandinsky’s theory show different results, both groups’ results do not correspond to Kandinsky’s theory, showing Kandisky’s results might reveal associations of a very specific group in Bauhaus.

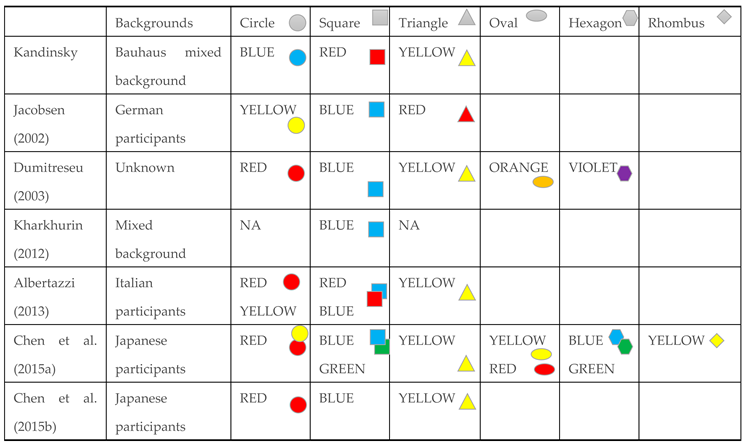

Recent research studies have challenged Kandinsky's empirical-spiritual experiment and have not been able to support his colour-shape associations (see

Table 1). His claim that universal colour-shape associations dominate cultural and personal differences is so alluring that many researchers seek his correspondence theory in their respective contemporary societies. Despite only a few have partially succeeded (Dumitreseu, 2003; Albertazzi, 2013). Both direct and indirect methods prove colour shape associations (Chen et al., 2015b), whereas explicit and implicit testing conditions in these direct and indirect methods do not support Kandinsky’s findings (Kharkhurin, 2012). Although Jacobsen (2002) employed a modified Kandinsky questionnaire, their study results could not align with Kandinsky’s results. Ultimately, these studies concluded that no universal colour-shape associations are embedded in the human brain as aesthetic universal; nevertheless, some may be rooted in an ecological basis (Makin & Wuerger, 2013). These research studies have demonstrated the existence of non-random associations between colour and shape (Sommers et al., 2004; Kharkhurin, 2012; Albertazzi, 2013), which are rooted in ecological basis, culture, and world knowledge (Makin & Wuerger, 2013; Chen et al., 2015a; Chen et al., 2015b; Jacobsen, 2002), not from universal rules embedded in the human brain.

Kharkhurin (2012) and Makin and Wuerger (2013) further discussed that Kandinsky might have had synesthetic experiences, resulting in powerful associations between these colours and shapes for himself. Kharkhurin (2012) claimed that if Kandinsky’s correspondence theory was rooted in associations embedded in the human brain as he proposed, empirical studies, which employ implicit testing, could find similar results. Nonetheless, their implicit testing only reveals square-blue preference consistently and no correspondence to Kandinsky’s theory. Dumitreseu (2003) stated that finding universal rules surpassing cultural barriers was a modernist dream that contemporary interior architects could share. Bauhaus had aimed to discover the basic principles of art and design and perfect the use of primary colours and forms, revealing a ‘universal ideal visual language’ for visual communications (Jacobsen, 2002, p. 903). But in 21st-century artists/designers/architects and also users are aware that design elements are context and culture-dependent, although there are some universally shared elements for design disciplines, for example, some universal material (Hekkert & Karana, 2014; Karana et al., 2009) and colour associations (Ulusoy & Olguntürk, 2017).

Albertazzi et al. (2013) conducted two experiments with 12 shapes and 40 colours (yellow, green, blue and red) in which the results (see Table-1) refer to naturally biased associations of colours and shapes which appear consistently in the population. Their study did not show any significant effect of ‘size, area/perimeter, and stability of shapes’ (Albertazzi et al., 2013, p. 44) and ‘conclude that shape contributes to the choice of hue’ (Albertazzi et al., 2013, p. 45). Chen et al. (2015a) stated that, in line with Albertazzi et al. (2013)’s results, colour associations of shapes might be based on lines and angles but not like Kandinsky’s association. Instead, they can be related to world knowledge like sun-circle-yellow (Kharkhurin, 2012) and sharp-danger (Sommer et al., 2004). Chen et al. (2015a) stated that curved lines (circle, oval, truncated cone) are warm and thus are related to RR (red), YY (yellow), and YR (orange); sharp lines (triangle, rhombus, cone, pyramid) are related to YY, whereas square, parallelogram, hexagon, trapezium, truncated pyramid, which are neither sharp nor curve, are cold thus they are associated with BB (blue), BG (blue-green), and GG (green). In an empirical study, participants were asked to create a ‘cute’ rectangle, and they ended with a more light-coloured rectangular than the reference one (Cho et al., 2020). Another previous research study shows that there is a correlation between colour and shape preferences: participants who preferred simple shapes also tended to prefer light or warm colours, while those who preferred complex shapes showed a tendency towards dark or cold colours (Chen et al., 2015c, p. 188) claiming that these preferences are rooted in the semantic information associated with visual stimuli. These studies show that people can associate shapes and colours to induce meanings which can be applied to interiors.

These previous studies about colour-shape associations uncover non-random, naturally biased colour-shape associations, albeit they cannot prove Kandinsky’s correspondence theory. Besides, they conclude that colour-shape associations are culturally diverse. Although some universal rules (e.g., world knowledge) might affect some associations, Table-1 demonstrates that colour-shape associations vary even with basic shapes and colours. When discussing a topic of preference, it is important to mention preference-for-harmony (Palmer & Griscom, 2013) and factor-t (Eysenck, 1940), which refer to an inner factor that motivates people to prefer harmonical and aesthetical stimuli. In Eysenck’s (1940) study, even odours in addition to a visual stimulus (colours, polygons, several visuals from portraits to masks, etc.) were studied, and the author concluded that there is a factor-t in which ‘t’ stands for ‘general factor of aesthetic appreciation’ (p. 101). Therefore, although generalisations should be avoided, research studies can uncover that factor and help interior architects during their design process to decide how to combine colours and shapes to satisfy their clients’/users’ needs and improve user experience in interiors. Considering it is not possible to find universal colour-shape associations, research studies need to find colour-shape preferences/semantics in interiors for their respective contemporary societies. Although there are previous studies about the effects of colours in interiors and basic colour-shape connotations in psychology studies independently, there is a gap in the literature about colour-shape preferences in interiors. Thus, this study investigates colour-shape preferences with colour-shape semantic associations and preferred colours and shapes on bedroom walls as a private residential interior (RI) in addition to favourite colours and shapes and colour-shape associations without context. In this study, colour-shape associations without context refer to matching shapes and colours without considering any particular design, while colour-shape preferences and colour-shape semantic associations refer to their preferences and meanings for an interior context and are investigated by image-based questions.

2. Colour-Shape Preferences in Residential Interiors

Before the COVID-19 pandemic shed light on our residential interiors, their colour applications were not investigated as much as other typologies because of their domestic nature. Spörrle and Stich (2010) rightfully mentioned that there are not enough scientific research studies about bedrooms in the interior architecture discipline, although people spend a third of their lives in them. Nevertheless, the interiority of a space is based on surface applications, which turn a house into a home (Ionescu, 2018). Considering today’s housing crisis in the UK (Brookfield, 2023), many people see their houses as an asset instead of a utility, so their users (tenants in most cases) aim to leave these interiors without any trace to save their deposits (Johnson-Schlee, 2022). These financial and social realities for housing encourage the current study to investigate how preference works in residential interiors, particularly on small-scale colour applications. Understanding colour preference on walls (full wall, half wall, shapes, etc.) can result in a better interior experience, enabling interiority. Users can enjoy their homes as personal spaces instead of houses, which are their landlords’ assets, by employing small-scale, affordable colour applications.

Some associations, sun-circle-yellow (Kharkhurin, 2012), might be sourced from universal elements; however, unlike Kandinsky’s claim, ecological bases, culture, and world knowledge affect colour-shape associations, and colour-shape preference/semantic associations are expected to be context-dependent. Bar and Neta (2006) revealed some aspects of these context-dependent differences: sharp objects are induced by semantic meaning and low-level perceptual properties: sharp-knife and sharp-countered watches are not preferred, except sometimes their affective value overrides their contour’s associations, such as snake-curve and chocolate bar-sharp corners. Previous studies about colour preferences/semantics (Taft, 1997; Kaya & Crosby, 2006; Van der Voordt T et al., 2017; Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) showed that colour associations are context-dependent, and people prefer different colours for different building/interior typologies. Considering we can prefer a colour for a textile design (a jumper) or a product design (a notebook) but not on our living room walls is logical. Therefore, colour-shape associations should be studied in interiors exclusively since generalising findings of psychology studies without context could not represent interior preferences.

In a colour shape preference study, Chen et al. (2015c) stated that GY (green-yellow) is the least preferred colour because of its associations with sickness and immaturity, while blue is the most preferred colour related to calmness and cleanness. Another previous study (Valdez et al., 1994, p. 394) revealed that yellow and yellow-green are the least pleasant colours, whereas ‘blue, blue-green, green, red-purple, purple, and purple-blue were the most pleasant’. Previous studies in the UK revealed that green has important associations such as life, growth, and spring (Hutchings, 2004) and as a wall colour: calm and home (Ulusoy & Olguntürk, 2017). In the context of residential buildings, according to Kaya and Crosby (2006), purple is the least favourite colour for residential building types, whereas blue (because of its calming associations such as tranquillity and relaxation) or red (due to past encounters of their participants with brick colours) are the most preferred colours. Purple is related to entertainment buildings and shopping malls since it is associated with creativity and fun (Kaya & Crosby, 2006). Güneş and Olguntürk (2020) showed that living rooms are associated with ‘disgust and happiness’, ‘happiness’, and ‘neutral’ with red, green, and blue, respectively. On the other hand, a recent study (Yıldırım et al., 2021) explored semantic aspects of shapes on bedroom walls and concluded that a circle, with its positive associations like warm, calming, etc., is the most preferred shape. Another previous study (Chen et al., 2015c) reported that a circle is the most preferred shape without interior context.

Colour preferences/semantics studies in RI revealed colour charts for bedroom interiors. In a previous study (Van der Voordt et al., 2017), which also investigated bedrooms whilst employing solely colour names without presenting any colour, white was the most preferred colour for all typologies (bedroom, living room, office, and meeting room), whereas brown is highly preferred following white for living rooms. The authors discussed that might result from stereotypical answers and/or habituation. Hence, this inspired more recent studies (Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) to exclude achromatic colours, which ended colour charts for RIs by exploring colour semantics in residential interior types (RITs) (e.g., bedroom, kitchen, etc.) with single (full-wall application) and paired colours (half-wall application). Ulusoy et al. (2020) reported different colour associations in different RITs. Their findings showed that some orange colours are consistently associated with negative meanings, thus revealing orange-loud and purple-cold associations for bedrooms. In a successive study, Ulusoy et al. (2021) stated that beige could be a colour with a positive meaning for most RI interiors and found that orange also has some negative position in paired colours. Purple was selected less and with mostly negative meanings (Ulusoy et al., 2020). However, in the colour pair study purple aroused positive meanings in some colour pairs (with red or blue) in some RITs (kids’ room, toilet, and bathroom), which concluded that its positive meanings depend on RITs in which it is applied as a wall colour in a pair and the other colours it is paired (Ulusoy et al., 2021).

There are colour preference/semantics studies in interiors. However, shape associations on bedroom walls have not been investigated in-depth until Yıldırım et al.’s (2021) study. Although they have investigated fewer shapes without colours and have slightly different approaches to methodology, the existence of these two studies proves the need in the discipline, which has evolved to a level of sophistication that requires in-depth research for shape applications in interiors. Research studies have a consensus that there are non-random colour and shape associations, and both universal and cultural components constitute them. This study aims to explore these associations in interiors in terms of preferences and semantics. The study embraced fluency theory which stated that people prefer visual stimuli that they perceive as easy to process and understand (Reber et al., 1998), leading participants to pick the most preferred colour-shape pairs for themselves.

The main aim of this study is to reveal colour-shape preferences for interior walls of bedrooms as a private RI. It was hypothesised that (1) colour preferences of geometric shapes on bedroom walls vary and (2) colour-shape preferences are expected to be context-depended so they follow neither previous psychology studies nor Kandinsky’s associations.

Furthermore, the study aims to reveal:

Colour-shape semantics with six adjective pairs (see

Appendix B) on bedroom walls,

Surface colour preferences and surface shape preferences on bedroom walls, independently,

Favourite colours and favourite shapes without interior context, independently,

Colour-shape associations without interior context.

Following these aims, it was hypothesised that:

Positive colour-shape semantic associations follow colour-shape preferences results in this study.

For bedroom walls circle is preferred over other shapes, and warm colours are preferred over other colours,

Favourite colours and favourite shapes differ from surface colour preferences and surface shape preferences on bedroom walls,

Without assigning them to interiors, in the light of the previous studies, colour shape associations follow square, circle and triangle would be associated with blue, red, and yellow, respectively. In parallel to their shapes and edges, hexagons might be related to blue/bluish colours, ovals might be associated with red/reddish colours, and rhombi might be related to yellow/yellowish colours.

3. Materials and Methods

The aim of the study is to explore the relationships between surface colours and surface shapes with regard to preferences and semantics in RIs. An online questionnaire was deployed through Google Surveys for this purpose. Google Surveys was chosen because it can randomise questions and their multiple choices. Participants were recruited from Amazon MTurk and were given a $0.5 incentive for their participation. They were only paid if they confirmed their Amazon ID and answered all required questions, providing a survey code proving they were human beings. To be eligible, participants had to self-identify as UK citizens over 18 years old, not colour-blind, and wearing corrective lenses if necessary. Amazon MTurk briefly explained the study, followed by a complete participant information form before obtaining their consent. This information form detailed the requirements for eligibility in the study. In order to begin the questionnaire, participants were required to confirm that they met all the requirements outlined in the information form. This included providing consent and verifying their eligibility to participate. The study had already received ethical approval under project ID xxxx. (removed for peer review). Once these initial steps were completed, participants could proceed with answering demographic questions such as age and education.

To prevent biases, the questions in each section were presented randomly, and their options were randomised. This ensured that participants could not select the same answer by simply choosing the first option and eliminated any potential order effect to contaminate the results. Because the main aim of this study is to reveal colour-shape preferences on bedroom walls, the first section contained imaged-based colour-shape preference questions, and the order of sections was not randomised. The survey consisted of four sections following the demographic questions, arranged as follows: image-based preferences, image-based semantics, preference questions without images, and follow-up questions. During the image-based preference section of the study, participants were given seven images asking them to choose one colour from a selection of options (red, blue, yellow, green, purple, brown, pink, and orange) for seven different surface shapes (square, circle, triangle, hexagon, rhombus, oval, and wind rose) displayed on a bedroom wall (see

Figure 1). Participants were allowed to choose only one colour for each shape and were free to select the same colour for more than one or all of the shapes. Following the preference questions with images, participants were instructed to match colours and adjectives (see

Appendix B for the adjective pairs) to the shapes. Adjective pairs are preferred to reflect on the previous studies (Taft, 1997; Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) The same images were employed for this section (see

Figure 1). This was done to uncover the interior semantics using the same methodology. In the third section of the survey, respondents were asked to select their preferred colour (from the same eight options) and shape (from six options without a wind rose) separately. This was specifically for bedroom walls without any accompanying images. During the last section of the study, participants were given open-ended questions to share their favourite colours and shapes independently. They were also asked to match eight different colours with six shapes without any interior context and were allowed to choose the same colour multiple times. Participants were explicitly instructed to respond solely based on their colour and shape associations without considering any interior and/or design elements.

In this study, colour names are employed without physical/digital colour samples as in the previous studies on colour preference (Van der Voordt T et al., 2017), which showed that colour names could substitute colours in interior colour preference studies. This methodology is preferred, under COVID-19 restrictions, because different screens might present digitally coloured images significantly differently. Albertazzi et al. (2013) reported that the hue of a shape affects preferences, whereas the size, area, and perimeter of the shape are not significant; thus, colour names can be used for colour-shape studies. Besides, Serra et al. (2022) showed that chromaticness of bedroom walls plays a crucial role in colour preferences for bedrooms: similar chromaticness on a colour chart with low chromaticness preferred more. Therefore, the study primarily concentrates on hue as a colour attribute, whose data can be collected through colour names, as the first attempt to investigate the colour-shape applications in interiors. However, it is essential to acknowledge the lack of colour samples in this study, which should be addressed in future studies with further investigation of other colour attributes, such as saturation and lightness. Nevertheless, the previous studies reported slight differences for real versus virtual interiors (Yıldırım et al., 2021) and photographs versus 360 VR interior spaces (Serra et al., 2022), leading the discussion that future studies of interior architecture should revisit their methodology according to the intended sample group in order to be more inclusive. Online methods enable different participants to contribute to the results, which can lead to a more diverse and well-rounded outcome. It allows individuals from different backgrounds and experiences to share their opinions and insights, eventually leading to a more comprehensive understanding of the topic. Referring back to Kharkhurin’s (2012) results on the difference between non-expert and expert colour-shape associations, including participants from different disciplines and backgrounds, it is important to reflect on user demographics.

Red, blue, yellow, green, purple, brown, pink, and orange, which are basic colour terms for all sophisticated languages according to Berlin and Kay's theory (1969), were preferred for more straightforward associations for participants. Achromatic colours of Berlin & Kay’s 11 basic colour terms (white, black, and grey) were excluded to avoid any contamination effect of habitation or stereotypical answers that had been mentioned by Van der Voordt et al. (2017). Seven achromatic images with mid-grey were created to present a bedroom interior with no contaminated variable (see

Figure 1): only the surface shapes of the wall behind the bed change in all images. There were no constraints on participants’ creativity and selection when making their design choices. There are no preconceived fashion or design restrictions that hinder them, and they can easily associate the images with their existing bedroom or their envisioned ideal bedroom. Three basic shapes (square, circle, and equilateral triangle) were used in addition other three shapes (hexagon, oval, and rhombus) that were mentioned in the previous study (Chen et al., 2015a) since they might be used in interior walls of a bedroom. Previous studies have utilised shapes such as semi-circle (Sommers et al., 2004) or truncated pyramids (Chen et al., 2015a), but they are not as commonly used in RIs as the six shapes mentioned. Therefore, it is possible that using these shapes could negatively impact participants’ attention. However, these shapes may be considered for inclusion in future studies. Furthermore, a wind rose design was formed using right-angled isosceles triangles to explore the potential differences between intricate wall designs and simpler shapes. Previous study results (Albertazzi et al., 2013) found that size, area, and perimeter did not significantly impact the concept, but the choice of hue is affected by shape. Nevertheless, each image of the bedroom has twelve shapes within the same area (as square meter) on the back wall to maintain a consistent design language (see

Figure 1) in order to avoid contaminating effects. Initially, a pilot study was conducted with fifteen participants, and since no amendments were necessary, an additional 85 participants were invited to participate, bringing the total number of participants to 100.

The students of Bauhaus were from various countries but were likely driven to study colours, forms, and other artistic elements (Jacobsen, 2002). Despite their differences in nationality, age, and gender, they developed a shared culture within the Bauhaus community that might result in Kandinsky’s colour-shape associations. In this study, considering Kharkhurin’s (2012) results, participants were asked about their experience with colours, their education, age, and gender. This ensured that the sample group was representative of individuals with varying levels of experience with colour. Nevertheless, the experienced group was not excluded or was not analysed separately. This is because experts and non-experts are users of residential interiors, and they can be a target group separately or in combined groups for bedroom designs. For instance, a couple may consist of one colour expert and one beginner. When conducting interior architecture studies, it is important to be reluctant while excluding experts or non-experts from participation, as they may represent a significant portion of the target user group. For this study, individuals of all gender identities and age groups (over 18 years old) who are UK citizens were invited to participate.

Jacobsen (2002) concluded that no colour-shape associations can be universally applied across all cultures. Likewise, Cho et al. (2020) noted that the perception of cuteness in a rectangle shape depends on interdependent cultural self-construct related to their culture. Moreover, Albertazzi (2013) and Chen et al. (2015a) uncovered similarities and differences between Italian and Japanese participants in their respective studies. The influence of culture on these associations was found to be significant. According to Jacobsen (2002, p. 912), factors that affect colour-shape associations are ‘historical and cultural changes, individual education and experience, fashion, and the presence and strength of the individual, group-specific and social motifs’ ergo the shared cultural background of participants is decisive. To maintain consistency with their shared cultural background, participants in this study were requested to be UK citizens, with no inquiry about their race. This refers to participants who were either born in the UK or have family roots in the UK or have resided in the UK for at least six years to obtain UK citizenship. Regardless of their race, religion, or place of birth/residence, they can share a common culture. It is important to note that the questionnaire was only offered in English, meaning that participants must have proficiency in the language.

4. Results and Discussion

The study's results were analysed using Microsoft Excel and IBM SPSS 25. The participants' demographic data revealed their educational backgrounds, with 73% holding a university degree or higher, 19% possessing a master's or PhD degree, and 8% having a high school diploma or equivalent. The majority of participants (63%) fell into the 25-34 age group, while the remaining participants were split between the 18-24 (5%), 35-44 (24%), 45-54 (7%), and 55-64 (1%) age ranges. Male participants outnumbered female participants at 63%, and 59% of all participants reported intermediate experience levels with colours, with 22% being beginners and 19% being advanced. An independent samples t-test was used to analyse demographic variables, and only a few shapes for some variables showed statistically significant differences (see

Appendix A). However, caution should be exercised when interpreting results for groups with a low number of participants, such as the 55-64 age group.

Colour-shape preferences were analysed based on the first four highest percentages, representing at least 60% of all responses as the high level of agreement among participants (see

Table 2). Levels of agreement of these preferences included circle (61%), oval (67%), square (65%), hexagon (66%), triangle (61%), rhombus (66%), and wind rose (61%). Colours ranked 5th or lower cannot account for more than 40% of combined preferences, indicating a lower level of preference in this population. According to Albertazzi et al. (2013), their participants had not seen any perplexity or difficulty understanding their task. In a similar vein, the comments part, which was an optional open-ended question at the end of the questionnaire, indicated enjoyment of the study with positive comments.

4.1. Colour-Shape Preferences

The primary objective of this study is to investigate colour preferences for various geometric surface shapes on bedroom walls. The preference data is collected from the first section of the online survey by randomised questions and choice orders, which ensures unbiased colour-shape preferences for bedroom walls. The study findings showed that, although purple is the most preferred colour for five shapes, there is considerable diversity in colour-shape preferences regarding bedrooms (see

Table 2); thus, the first hypothesis cannot be rejected. According to the findings, the colour-shape preferences in bedrooms do not align with Kandinsky’s results and only partially align with previous psychology studies (e.g., hexagon-violet) (Dumitreseu, 2003), showing that colour-shape preference is -context-dependent. Therefore, the second hypothesis cannot be rejected as well. With the exception of the wind rose shape, purple is the most favoured colour for other geometrical shapes, followed closely by brown or blue. This contrasts with the findings of previous studies, such as Kaya and Crosby’s (2006) research, which found that purple was the least popular colour for residential buildings, and Ulusoy et al. (2020) noted a negative association in bedrooms as a purple-cold, making it less preferable in bedrooms. However, a recent study (Ulusoy et al., 2021) showed that purple hold neither positive nor negative meaning in most RITs. In fact, it can have positive connotations when paired with certain colours in certain RITs. These differences between studies may be due to cultural differences (UK citizens vs Turkey or U.S.A. residents), or purple might be preferred as an accent colour on bedroom walls. Accents are ‘more saturated or complementary colors that are used to a much lesser extent or to highlight particular aspects or details. They act as the counterpoint for the composition’ (Lluch, 2019, p. 254). Purple might be related to different meanings on different surface percentages: a small wall application is desirable, whereas a full wall is cold in bedrooms.

According to previous studies (Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021), orange is not a favourable choice for bedroom walls when used as a full- or half-wall application. In this study, it might be preferred for circle and triangle shapes, with the lowest percentage for rhombus and low percentages for other shapes. These findings are consistent with Taft’s findings (1997) that orange is the ugliest and loudest colour in a product design study. Additionally, colour semantics studies (Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) suggest that certain shades of orange may arouse negative associations in RITs, such as being loud in bedrooms as a single colour or being unpleasant and uncomfortable as a paired colour. The authors note that these negative connotations may not be context-dependent and could be generalised. It is worth noting that according to Mahnke (1996), bright orange can be used as an accent colour but not on walls (not just limited to RIs). The current study’s findings support this notion that orange is not associated with a positive experience on interior walls, particularly on RIs, and that very few exceptional applications (on circles and triangles) are preferable. It is possible that orange has negative connotations or associations that are not suitable for a bedroom. However, individuals may prefer it as an accent colour on bedroom walls, but only in specific surface shape applications. For the circle, orange has a higher percentage that competes with purple and brown, which might relate to sun-circle associations, considering it is followed by yellow. Similarly, yellow is highly preferred for triangles, aligning with psychology studies (see

Table 1). However, further investigation is needed to uncover the semantic associations’ effects on the colour preference of surface shapes.

According to the study findings, blue and brown have very high percentages after purple. Comparing these results, brown is highly preferred for surface shapes, to previous study results (Ulusoy et al., 2021), which stated that beige is a desirable colour for paired colours on RITs’ walls, it can be discussed that earth tones might be suitable choices for bedroom walls for various applications. Similarly, Van der Voordt et al. (2017) showed that brown is the second most preferred colour after white for living rooms. Moreover, Kaya and Crosby (2006) claimed that blue is the most preferred colour in residential buildings. In addition, Chen et al. (2015c) stated that blue is desirable due to its calmness and cleanness associations, which correspond to the results of this study. It was also noted that blue is preferred with high percentages for most shapes except circle and rhombus, whereas green tends to be in the middle range for all shapes. In addition to Hutchings’s findings (2004), another previous study in the UK (Ulusoy & Olguntürk, 2017) showed that the green colour on entire interior walls is associated with positive meanings such as calming and home. However, green as a shape colour does not have a high preference in the current study. These findings indicate that preference for colours on full- or half-wall applications and surface shapes, such as green vs purple, may differ significantly. In this study, the wind rose shape, which presented more sophisticated design choices on wall applications than other geometrical shapes, has blue as the most preferred colour. That might be interpreted as when there are more complicated and sophisticated applications on bedroom walls, users might prefer slightly different colours because purple is still the second most preferred colour (see

Table 2). More complex wall applications require further investigation in order to clarify their preferred colours with colour semantics.

Yellow, which follows orange, has the lowest percentage for wind rose shapes. Nonetheless, yellow falls in the middle range for hexagons, but orange is preferred less. Pink is preferred more for hexagons, rhombi and wind rose shapes than other shapes, for example, the lowest percentage for triangles. Red has very low percentages except for rhombi; its lowest percentages are for circles, ovals, and squares, so it is not recommended for most of these shapes on bedroom walls (see

Table 2). It is interesting to note that hexagons, rhombi, and wind rose shapes have more pink selections than others, triangles have less brown, and rhombi have more red selections than other shapes. These differences show that although purple is the preferred surface shape colour, followed by brown and blue, there are differences between shapes. Moreover, yellow is preferred more for circles and triangles, while green is preferred more for ovals and squares, which shows that it is not possible to predict colour preferences according to corners and angles of shapes for bedroom interiors.

4.2. Colour-Shape Semantic Associations

The study aims to reveal colour-shape semantics in interiors. While some variations in meaning and shape were found, the overall results did not reveal significant correlations and were mostly aligned with colour preferences. The results (see

Appendix B) are promising, but additional research studies with larger sample sizes and varied methods are necessary. It is noteworthy that purple, brown, pink, and blue were consistently identified as the top colours associated with all shapes except for oval (green/passive, yellow/active), square (yellow/weak), hexagon (yellow/small), and rose wind (yellow/slow). Unlike the preference results, rose wind shapes were not significantly associated with blue. Furthermore, pink was more frequently linked to the colour-shape semantics when comparing these results to colour preference results. The hypothesis that positive meanings are more closely linked to preference results than negative meanings was rejected. This could be due to participants feeling overwhelmed by the questionnaire and responding based on their colour-shape preferences. Alternatively, they might consider other colour attributes (saturation and lightness) and pick hue names accordingly, resulting in the same hue names for opposite meanings, which implies that saturation and lightness might have significant effects on colour semantics for surface shapes on bedroom interiors as the previous study discussed for residential interior walls (Ulusoy et al., 2020). As a result, more research is required to explore the semantic associations between colour and shape combinations.

4.3. Colour and Shape Preferences in Bedrooms

Preference questions without images reveal that blue is the most preferred colour for bedroom walls, which rejects the hypothesis that warm colours would be preferred more (see

Table 3). This result corresponds to Kaya and Crosby’s (2006) results, which showed that blue is the most preferred colour for residential buildings. Green has a higher percentage as a wall colour in bedrooms, corresponding to previous findings (Hutchings, 2004; Ulusoy & Olguntürk, 2017; Ulusoy et al., 2020; Günes & Olguntürk, 2020). Interestingly, these results align with previous research suggesting that orange is not desirable for bedroom walls, showing full-wall and surface shape differences in this study. On the other hand, the hypothesis that a circle would be preferred more is not rejected (see Table-3). The oval shape, which resembles a circle, was also ranked highly in this study. This aligns with findings from previous studies by Chen et al. (2015c) and Yıldırım et al. (2021), which also identified the circle as the most preferred shape. These results show that purple is the preferred colour for bedroom walls which contradicts the previous studies (Kaya & Crosby, 2006; Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021). It is possible that the order effect of sections in this study (i.e., image-based colour-shape preference is the first section for all participants) could have influenced participants' opinions on full-wall colour preferences. Another possibility is that purple has a more positive connotation in the UK compared to previous studies conducted in Turkey (Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) and the U.S.A. (Kaya & Crosby, 2006).

4.4. Favourite Colours and Shapes

The participants in the study were asked to share their favourite colours and shapes. It was found that blue is the favourite colour (as mentioned by Chen et al., 2015c; Fox, 2021), followed by pink. Interestingly, despite having the lowest percentage for bedroom walls (see

Table 3), red ranked third (see

Table 4). It also had a significantly higher percentage than purple and green. This suggests that the participants understood the task, chose colours based on context, and were not fully biased by order effect. The results show that a favourite colour, preferred wall colour, and preferred colour for surface shape on walls may vary significantly, indicating that colour preference is context-dependent. Circle and oval remain the most favoured shapes, as previous studies have shown (Chen et al., 2015c; Yıldırım et al., 2021). The same order of preferred surface shapes on bedroom walls was observed: circle, oval, square, triangle, hexagon, and rhombus (see

Table 3 and

Table 4). Additionally, a few new shapes with a very low percentage were added, such as pentagons, diamonds, heart shapes, and stars. These shapes can be explored in future studies. A comparison of favourite shapes (see

Table 4.) and preferred shapes on bedroom walls (see

Table 3.) with favourite colours (see

Table 4) and preferred colours on bedroom walls (see

Table 3) indicates that shape preferences might be less context-dependent than colour preferences. The hypothesis that stated preferred surface shapes and favourite shapes should differ is rejected while preferred surface colours and favourite colours cannot be rejected.

4.5. Colour-Shape Associations without Interiors

Finally, participants were asked to match colours and shapes, with a wider range of options compared to previous studies. The colour-shape associations of this study indicated that pink, brown, and orange are mostly associated with all shapes, except rhombus, which is associated with pink, orange and yellow (see

Table 5). The hypothesis that square/hexagon, circle/oval, and triangle/rhombus would be associated with blue/bluish, red/reddish, and yellow/yellowish colours, respectively, was rejected by the findings. Although circle and oval were matched with pink, a reddish colour, red itself is the last in order. Only Dumitreseu (2003)’s oval-orange and Chen et al. (2015a)’s rhombus-yellow associations were partially recorded in these results (

Table 5). These differences with previous studies might source from cultural differences. Alternatively, they can be explained by previous studies' limited number of shapes and colours. The results can be good indicators that people tend to pick different colours when they have more choices. It is important to note that the high percentage of orange, mid percentages of purple and low percentages of blue in all shapes indicate that colour-shape associations cannot show colour-shape preferences on bedroom walls (see

Table 2). Besides, although they were asked in the same questionnaire, participants could evaluate them separately. Compared to the image-based colour preference questions in interiors, colour-shape association shows higher agreement for all shapes: circle 71%, oval 80%, square 77%, hexagon 75%, triangle 73%, and rhombus 68% (see

Table 5). That might be interpreted as colour-shape associations might be stronger when the participants are not asked to consider design/architectural context, enabling diversity.

4.6. Overall Results

The study aims to investigate colour-shape applications for the interior walls of bedrooms as private interiors. Its findings present unbiased colour-shape preferences for bedroom walls as a RIT.

Table 2 functions as a guide for professionals in the industry and future researchers. In this study, image-based preference, preferences without images, and favourite colours revealed a variety of reliable results, showing that colour preference is context-dependent and that the participants understand the tasks. Moreover, the similarities and differences between the current and previous studies (psychology and design/architecture) are discussed. The study results show that colour preference of full-wall, half-wall, and surface shapes can vary significantly in interiors, for this study, residential interiors (bedrooms). Considering this study employed mid-grey as a full wall colour, further research studies are needed to explore wall colour-shape preferences in relation to foreground-background colours. Moreover, unlike previous psychology studies, the study showed that it is not possible to predict colour-shape preferences on bedroom walls according to their corners and shapes.

Regarding image-based semantic association questions, results did not show significant differences between adjective pairs with opposite meanings. It can be interpreted as colour-shape preferences, favourite colours and shapes, and colour-shape associations are strongly related to the topic and participants paid full attention to these aspects. However, they may have struggled to focus on semantics in a preference study. On the other hand, these results might be due to the effects of saturation and lightness, whose contributions are proved in the previous studies (Kaya & Crosby, 2006; Ulusoy et al., 2020), which participants might consider during their design choices. Additional research utilising a broader range of research methods and all colour attributes is necessary to understand the semantic aspects related to colour-shape pairs in interior architecture for various typologies.

5. Conclusions

Research on colour applications in interiors has been ongoing for many years. However, recent studies by Yıldırım et al. (2021) and the current study indicate a need for further investigation into the use of colour in interior architecture with more complex elements such as surface shapes and colour-shape preferences/semantics. This will require significant effort and research to fully understand how colour can be used with other interior architectural elements. Nonetheless, the field has progressed to a point where this type of inquiry is achievable. The results have shown that selecting colours for surface shape applications on walls, choosing colours for walls and favourite colours differ. While colour preferences may vary, the desired surface shape for a wall and favourite shape may not vary as much. In regard to interior architecture, it has been found that users may have a stronger sensitivity to colour applications compared to shape applications.

The differences between the findings of this study and previous research on the colour purple (Kaya & Crosby, 2004; Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) may be due to cultural differences. Nevertheless, it seems evident that purple is a more desirable colour when paired with certain colours in specific RITs (Ulusoy et al., 2021) and for small-scale applications such as bedroom wall surface shapes. However, it may not be as suitable for larger areas. After considering the findings of prior research (Mahnke, 1996; Taft, 1997; Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) with the current study, it has been determined that interior architects should exercise caution when applying orange to bedroom wall colour schemes. The study aims to investigate hue as the first step of elaborated colour charts for colour-shape pairs on RIT walls. It is important to note that previous studies (Kaya & Crosby, 2006; Ulusoy et al., 2020) showed that lightness and saturation of colour have effects on preference and semantics. Similarly, this study's image-based semantic association results imply some effects of all colour attributes. Future studies should be conducted to reveal how different colour attributes affect the preference/semantics of surface geometric shapes in interiors. Furthermore, the previous studies (Ulusoy et al., 2020; Ulusoy et al., 2021) excluded achromatic colours when examining RI colour charts. This study uses grey as a neutral colour for bedroom interiors to assess colour applications (of geometric surface shapes) on walls, with white and black excluded. This initiates a further investigation for chromatic-achromatic colour combinations, shape-wall colour pairs as a foreground-background relationship of colours and overall colour charts (colours of floor, furniture, etc.).

This research builds upon prior studies on colours and shapes, incorporating interior perspectives and methodological discussions. For the first time, unbiased colour-shape preferences in bedrooms are presented. The data also compares colour preferences across various contexts and discusses the previous studies' colour charts. Overall, these findings support the notion that colour preferences in interiors are context-dependent. While psychology studies can offer some valuable insights, it is crucial for the field of interior architecture to conduct extensive and well-structured research on these applications. Research studies should further investigate colour preferences and semantics to understand users' experiences, behaviours, and needs. This will benefit professionals such as interior architects, architects, interior designers, and designers and users.

According to Sommer et al. (2004), more investigation is required on this subject using a range of research techniques and resources. As a response to their call, this study aims to explore the relationship between colour and surface shape in interior architecture using online tools. Online tools have expanded the sample group beyond just undergraduate and graduate students to include the general public, despite their limitation to using hue names for colour exploration. This has had a positive effect that outweighs any negative effects. With the rise of AI, peoples’ lives will become more digitalised. From metaverse to social media and to NFTs, online tools might dominate their choices of colours and interiors in the future. Therefore, design and architecture disciplines must adapt and discover ways to communicate fluently with the new digital generations. This study contributes to this goal. The findings of this study will be beneficial to professionals and researchers in the fields of architecture, design, and psychology. Future studies should focus on colour-shape semantics and provide a more comprehensive understanding of the context-colour relationship with various shapes, colours, interior types, and methodologies.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Mr XXX for providing the visuals and to the hundred participants who generously gave their time for the empirical study. During the writing process, Grammarly generated responses to the following AI prompts: improve the text and its English grammar. The author reviewed and edited the generated responses as necessary.

Appendix A

T-test results for comparison of gender, age, education and experience groups (.07-.05 range is presented for consideration and discussion while <.05 results are statically significant – in bold).

| Variable |

Shape |

Sig. (2-tailed) |

| Gender |

Triangle |

.050 |

| Experience: beginner vs intermediate |

Oval |

.052 |

| Hexagon |

.021 |

| Experience: beginner vs advance |

Hexagon |

.047 |

| Age: 18-24 vs 25-34 |

Circle |

.012 |

| Age: 18-24 vs 45-54 |

Square |

.048 |

| Age: 18-24 vs 55-64 |

Circle |

.045 |

| Square |

.057 |

| Age: 25-34 vs 35-44 |

Circle |

.055 |

| Age: 45-54 vs 55-64 |

Rhombus |

.047 |

| Education: High School degree or equivalent vs University degree |

Triangle |

.035 |

| Education: High School degree or equivalent vs Master/Ph.D. degree |

Circle |

.051 |

| Square |

.042 |

| Triangle |

.001 |

| Education: University degree vs Master/Ph.D. degree |

Triangle |

.023 |

Appendix B

Preferred colours for shapes on bedroom walls (the study embraced colour names; the table’s colours are representative). R: Red, G: Green, Y: Yellow, Bl: Blue, O: Orange, Br: Brown, Pi: Pink, Pu: Purple

| SQUARE |

Ugly |

Beautiful |

Passive |

Active |

Weak |

Strong |

Small |

Large |

Bad |

Good |

Slow |

Fast |

| R 2 |

R 2 |

R 5 |

R 5 |

G 5 |

G 4 |

O 5 |

R 5 |

G 8 |

R 3 |

R 2 |

R 5 |

| O 9 |

Or 4 |

G 9 |

G 9 |

R 7 |

Y 7 |

R 5 |

G 7 |

R 8 |

Y 3 |

G 6 |

O 6 |

| G 11 |

G 7 |

O 9 |

Bl 10 |

O 10 |

O 9 |

Bl 8 |

P 10 |

O 9 |

G 8 |

O 10 |

Y 6 |

| Y 11 |

Y 8 |

Y 10 |

O 10 |

Pu 14 |

R 10 |

G 9 |

Y 11 |

Y 9 |

O 8 |

Y 10 |

G 10 |

| Bl 14 |

Bl 19 |

Pi 12 |

Y11 |

Pi 15 |

Br 16 |

Y 12 |

O 12 |

Bl 13 |

Bl 12 |

Br 13 |

Bl 11 |

| Pu 15 |

Br 19 |

Bl 14 |

Pi 15 |

Y 15 |

Bl 17 |

Pi 18 |

Br 15 |

Br 14 |

Br 17 |

Pi 17 |

Pi 18 |

| Pi 17 |

Pu 19 |

Br 15 |

Pu 18 |

Bl 17 |

Pu 18 |

Pu 19 |

B 16 |

Pu 19 |

Pi 18 |

Bl 18 |

Br 21 |

| Br 21 |

Pi 22 |

Pu 26 |

Br 22 |

Br 17 |

Pi 19 |

Br 24 |

Pu 24 |

Pi 20 |

Pu 31 |

Pu 24 |

Pu 23 |

| TRIANGLE |

Ugly |

Beautiful |

Passive |

Active |

Weak |

Strong |

Small |

Large |

Bad |

Good |

Slow |

Fast |

| R 3 |

Y 1 |

R 2 |

O 5 |

R 4 |

G 5 |

G 4 |

R 4 |

O 6 |

R 2 |

G 2 |

R 4 |

| O 5 |

R 2 |

O 6 |

R 5 |

G 5 |

R 7 |

O 6 |

G 7 |

R 6 |

Y 4 |

R 3 |

Y 5 |

| Bl 9 |

G 8 |

G 7 |

G 8 |

O 5 |

Y 9 |

R 6 |

O 8 |

G 8 |

O 7 |

O 7 |

G 9 |

| G 11 |

O 10 |

Y 11 |

Pi 12 |

Bl 12 |

O 10 |

Y 9 |

Y 8 |

Y 10 |

G 10 |

Bl 10 |

O 10 |

| Y 11 |

Br 16 |

Bl 12 |

Y 12 |

Y 15 |

Br 13 |

Bl 15 |

Bl 14 |

Bl 11 |

Br 15 |

Y 12 |

Bl 14 |

| Pi 13 |

Bl 20 |

Pi 13 |

Br 13 |

Br 17 |

Bl 14 |

Pi 17 |

Pi 15 |

Pi 14 |

Bl 18 |

Pi 18 |

Pi 14 |

| Br 24 |

Pi 21 |

Pu 23 |

Bl 19 |

Pi 20 |

Pi 18 |

Br 20 |

Br 16 |

Br 22 |

Pi 18 |

Br 22 |

Br 21 |

| Pu 24 |

Pu 22 |

Br 26 |

Pu 26 |

Pu 22 |

Pu 24 |

Pu 23 |

Pu 28 |

Pu 23 |

Pu 26 |

Pu 26 |

Pu 23 |

| CIRCLE |

Ugly |

Beautiful |

Passive |

Active |

Weak |

Strong |

Small |

Large |

Bad |

Good |

Slow |

Fast |

| O 5 |

R 2 |

R 2 |

R 2 |

Y 5 |

G 3 |

R 2 |

G 2 |

G 6 |

R 2 |

R 2 |

R 3 |

| R 5 |

G 4 |

O 6 |

G 7 |

R 6 |

R 5 |

O 8 |

Y 4 |

O 6 |

G 7 |

O 7 |

G 8 |

| G 6 |

O 6 |

G 8 |

Y 7 |

G 7 |

P 9 |

G 9 |

R 5 |

Y 7 |

O 9 |

G 9 |

Y 9 |

| Y 6 |

Pi 12 |

Y 9 |

Br 9 |

O 9 |

O 10 |

Y 9 |

O 7 |

R 8 |

Y 9 |

Y 12 |

O 10 |

| Bl 10 |

Y 13 |

Pu 14 |

O 9 |

Bl 13 |

Y 11 |

Bl 13 |

Pi 15 |

Bl 11 |

Bl 14 |

Bl 14 |

Pi 12 |

| Pi 18 |

Br 19 |

Bl 19 |

Bl 18 |

Br 18 |

Bl 12 |

Pi 15 |

Bl 20 |

Br 18 |

Br 18 |

Pu 17 |

Bl 16 |

| Pu 23 |

Bl 20 |

Pi 20 |

Pi 24 |

Pi 20 |

Br 14 |

Pu 21 |

Br 22 |

Pi 21 |

Pu 20 |

Pi 19 |

Br 16 |

| Br 27 |

Pu 24 |

Br 22 |

Pu 24 |

Pu 22 |

Pu 36 |

Br 23 |

Pu 25 |

Pu 23 |

Pi 21 |

Br 20 |

Pu 26 |

| HEXAGON |

Ugly |

Beautiful |

Passive |

Active |

Weak |

Strong |

Small |

Large |

Bad |

Good |

Slow |

Fast |

| R 4 |

R 2 |

R 3 |

R 4 |

R 3 |

Y 6 |

R 3 |

Y 2 |

Y 6 |

R 3 |

R 1 |

R 3 |

| G 5 |

Y 6 |

O 7 |

Y 5 |

G 7 |

G 7 |

G 7 |

R 5 |

R 7 |

O 9 |

O 4 |

G 5 |

| O 7 |

G 7 |

Y 7 |

O 9 |

O 7 |

O 10 |

Bl 8 |

Pi 7 |

G 8 |

G 10 |

G 8 |

O 8 |

| Bl 11 |

O 8 |

G 8 |

Bl 12 |

Bl 10 |

R 10 |

O 8 |

G 9 |

O 8 |

Y 10 |

Y 8 |

Y 8 |

| Y 12 |

Br 14 |

Bl 15 |

G 13 |

Y 12 |

Pi 11 |

Pi 14 |

O 9 |

Br 13 |

Bl 13 |

Bl 14 |

Pi 12 |

| Pu 16 |

Pi 16 |

Br 17 |

Br 18 |

Br 16 |

Bl 12 |

Y 16 |

Bl 16 |

Pi 15 |

Pi 14 |

Pi 16 |

Bl 13 |

| Br 21 |

Bl 22 |

Pu 21 |

Pi 18 |

Pi 21 |

Br 19 |

Pu 21 |

Br 20 |

Pu 19 |

Br 20 |

Pu 24 |

Br 25 |

| Pi 24 |

Pu 25 |

Pi 22 |

Pu 21 |

Pu 24 |

Pu 25 |

Br 23 |

Pu 32 |

Bl 24 |

Pu 21 |

Br 25 |

Pu 26 |

| RHOMBUS |

Ugly |

Beautiful |

Passive |

Active |

Weak |

Strong |

Small |

Large |

Bad |

Good |

Slow |

Fast |

| G 4 |

Y 2 |

O 4 |

R 2 |

R 3 |

G 6 |

R 5 |

R 3 |

R 4 |

R 6 |

R 2 |

R 3 |

| R 5 |

R 4 |

G 5 |

Y 8 |

G 5 |

O 7 |

O 6 |

G 7 |

G 7 |

G 7 |

Y 5 |

Y 7 |

| O 8 |

O 5 |

R 5 |

Bl 10 |

O 7 |

R 7 |

G 7 |

Y 7 |

O 8 |

O 8 |

O 8 |

O 8 |

| Bl 11 |

G 6 |

Y 5 |

G 10 |

Bl 10 |

Y 8 |

Y 13 |

Br 11 |

Y 11 |

Y 10 |

G 13 |

G 10 |

| Y 11 |

Bl 16 |

Bl 9 |

O 10 |

Y 11 |

Bl 14 |

Pi 14 |

O 12 |

Pi 15 |

Bl 13 |

Pi 13 |

Pi 11 |

| Pi 17 |

Pi 17 |

Pi 21 |

Br 14 |

Pi 20 |

Br 18 |

Bl 15 |

Bl 17 |

Bl 16 |

Br 16 |

Bl 15 |

Pu 17 |

| Pu 20 |

Br 23 |

Br 24 |

Pi 17 |

Br 22 |

Pi 19 |

Pu 19 |

Pu 18 |

Pu 19 |

Pu 17 |

Pu 20 |

Bl 19 |

| Br 24 |

Pu 27 |

Pu 27 |

Pu 29 |

Pu 22 |

Pu 21 |

Br 21 |

Pi 25 |

Br 20 |

Pi 23 |

Br 24 |

B 25 |

| OVAL |

Ugly |

Beautiful |

Passive |

Active |

Weak |

Strong |

Small |

Large |

Bad |

Good |

Slow |

Fast |

| R 4 |

R 4 |

R 3 |

R 3 |

R 5 |

R 8 |

R 1 |

G 6 |

Y 6 |

O 3 |

R 2 |

R 2 |

| O 7 |

G 6 |

Y 6 |

G 7 |

Bl 7 |

G 9 |

O 5 |

R 6 |

O 7 |

R 4 |

O 5 |

G 7 |

| Bl 9 |

O 8 |

O 7 |

O 10 |

O 8 |

Y 9 |

G 6 |

Bl 8 |

R 7 |

Y 8 |

G 8 |

O 8 |

| Y 10 |

Br 10 |

Bl 10 |

Bl 11 |

Y 12 |

O 10 |

Y 11 |

Y 9 |

G 8 |

Bl 9 |

Y 9 |

Y 9 |

| G 11 |

Y 11 |

Pi 13 |

Br 11 |

G 13 |

Br 12 |

Bl 15 |

O 10 |

Bl 15 |

G 13 |

Bl 13 |

Pi 14 |

| Pi 18 |

Bl 15 |

G 14 |

Y 13 |

Br 18 |

Bl 13 |

Pu 19 |

Pi 14 |

Br 16 |

Pi 18 |

Pi 20 |

Bl 17 |

| Br 20 |

Pi 18 |

Br 17 |

Pi 16 |

Pu 18 |

Pi 17 |

Pi 21 |

Br 17 |

Pi 20 |

Br 19 |

Br 21 |

Br 20 |

| Pu 21 |

Pu 28 |

Pu 30 |

Pu 29 |

Pi 19 |

Pu 22 |

Br 22 |

Pu 30 |

Pu 21 |

Pu 26 |

Pu 22 |

Pu 23 |

| ROSE WIND |

Ugly |

Beautiful |

Passive |

Active |

Weak |

Strong |

Small |

Large |

Bad |

Good |

Slow |

Fast |

| R 5 |

R 2 |

R 2 |

R 4 |

O 4 |

R 4 |

R 5 |

O 4 |

R 7 |

R 1 |

R 5 |

R 4 |

| Y 6 |

G 6 |

G 7 |

Y 5 |

R 7 |

Y 6 |

O 8 |

G 6 |

G 9 |

G 6 |

O 6 |

G 7 |

| G 10 |

Y 6 |

Y 10 |

G 7 |

Y 9 |

G 9 |

Y 9 |

R 6 |

O 9 |

O 8 |

G 7 |

Y 10 |

| O 11 |

O 7 |

O 12 |

O 12 |

G 10 |

O 9 |

Pi 11 |

Bl 13 |

Bl 11 |

Y 8 |

Bl 12 |

Bl 11 |

| Bl 12 |

Bl 15 |

Pi 15 |

Bl 14 |

Bl 11 |

Br 12 |

G 12 |

Y 13 |

Y 11 |

Bl 16 |

Br 12 |

Pi 12 |

| Pi 15 |

Br 16 |

Pu 15 |

Pi 15 |

Pu 13 |

Bl 17 |

Bl 15 |

Br 17 |

Pi 14 |

Br 18 |

Y 14 |

O 17 |

| Br 20 |

Pi 23 |

Bl 17 |

Br 21 |

Br 18 |

Pi 20 |

Br 19 |

Pu 19 |

Pu 14 |

Pi 20 |

Pi 18 |

Br 19 |

| Pu 21 |

Pu 25 |

Br 22 |

Pu 22 |

Pi 28 |

Pu 23 |

Pu 21 |

Pi 22 |

Br 25 |

Pu 23 |

Pu 26 |

Pu 20 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

References

- Albertazzi, L., Da Pos, O., Canal, L., Micciolo, R., Malfatti, M., & Vescovi, M. (2013) The hue of shapes, Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 39(1), 37. [CrossRef]

- Bar, M., & Neta, M. (2006) Humans prefer curved visual objects, Psychological science, 17(8), 645-648. [CrossRef]

- Berlin, B., & Kay, P. (1969) Basic color terms: Their university and evolution, California UP.

- Brookfield, K., Dimond, C., & Williams, S. G. (2023) Selling city centre flats in uncertain times: findings from two English cities, Housing Studies, 1-27.

- Chen, N., Tanaka, K., Matsuyoshi, D., & Watanabe, K. (2015a) Associations between color and shape in Japanese observers, Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 9(1), 101-110. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0038056.

- Chen, N., Tanaka, K., & Watanabe, K. (2015b) Color-shape associations revealed with implicit association tests, PloS one, 10(1), e0116954. [CrossRef]

- Chen, N., Tanaka, K., Matsuyoshi, D., & Watanabe, K. (2015c) Cross preferences for colors and shapes, Color Research & Application, 41(2), 188-195. [CrossRef]

- Cho, S., Dydynski, J. M., & Kang, C. (2020) Universality and specificity of the kindchenschema: A cross-cultural study on cute rectangles, Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 16(4), 719–732. [CrossRef]

- Cuskley, C., Simner, J., & Kirby, S. (2017) Phonological and orthographic influences in the bouba–kiki effect, Psychological research, 81, 119-130. [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, A. (2003) Study on relationship between elementary geometric figures and basic colours, University" Politehnica" of Bucharest Scientific Bulletin, Series D: Mechanical Engineering, 65(1), 77-90.

- Eysenck, H. J. (1940) The general factor in aesthetic judgements 1. British Journal of Psychology, General Section, 31(1), 94-102.

- Fox, J. (2021) The world according to colour: a cultural history, Penguin UK.

- Güneş, E., & Olguntürk, N. (2020) Color-emotion associations in interiors, Color Research & Application, 45(1), 129-141. [CrossRef]

- Hekkert P., & Karana E. (2014) Designing material experience, Karana, E., Pedgley, O., & Rognoli, V. (Eds.) (2014) Materials experience: Fundamentals of materials and design, Butterworth-Heinemann, p 3–11.

- Holtzschue, L. (2006) Understanding Color: An Introduction for Designers, Hoboken NJ: Wiley.

- Hutchings, J. (2004) Color in folklore and tradition - The principles. Color Research & Application, 29: 57–66. [CrossRef]

- Ionescu, V. (2018) The interior as interiority, Palgrave Communications, 4(1), 1-5. [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, T. (2002) Kandinsky's questionnaire revisited: fundamental correspondence of basic colors and forms?, Perceptual and Motor Skills, 95(3), 903-913. [CrossRef]

- Johnson-Schlee, S. (2022) Living Rooms, Peninsula Press, London.

- Karana, E., Hekkert, P., & Kandachar, P. (2009) Meanings of materials through sensorial properties and manufacturing processes, Materials & Design, 30(7), 2778-2784. [CrossRef]

- Kaya, N., & Crosby M. (2006) Color associations with different building types: An experimental study on American college students, Color Research & Application, 31(1): 67–71. [CrossRef]

- Kharkhurin, A. V. (2012) Is triangle really yellow? An empirical investigation of Kandinsky's correspondence theory, Empirical Studies of the Arts, 30(2), 167-182. [CrossRef]

- Lluch, J. S. (2019) Color for Architects (Architecture Brief), Chronicle Books.

- Mahnke, F. H. (1996) Color, environment, and human response: an interdisciplinary understanding of color and its use as a beneficial element in the design of the architectural environment, John Wiley & Sons.

- Makin, A. D., & Wuerger, S. M. (2013) The IAT shows no evidence for Kandinsky's color-shape associations, Frontiers in psychology, 4, 616. [CrossRef]

- Palmer, S. E., & Griscom, W. S. (2013) Accounting for taste: Individual differences in preference for harmony, Psychonomic bulletin & review, 20, 453-461. [CrossRef]

- Reber, R., Winkielman, P., & Schwarz, N. (1998) Effects of perceptual fluency on affective judgments, Psychological science, 9(1), 45-48. [CrossRef]

- Serra, J., Gouaich, Y., & Manav, B. (2022) Preference for accent and background colors in interior architecture in terms of similarity/contrast of natural color system attributes, Color Research & Application, 47(1), 135-151. [CrossRef]

- Sommer, R., Sommer, B. A., & Cho, J. H. (2004) Color–Shape Connotations of Geometric Figures, Journal of Interior Design, 30(3), 41-50. [CrossRef]

- Spörrle, M., & Stich, J. (2010) Sleeping in safe places: An experimental investigation of human sleeping place preferences from an evolutionary perspective, Evolutionary Psychology, 8(3). [CrossRef]

- Taft, C. (1997) Color meaning and context: comparisons of semantic ratings of colors on samples and objects, Color Research & Application, 22(1), 40-50. [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, B., & Nilgün, O. (2017) Understanding responses to materials and colors in interiors, Color Research & Application, 42(2), 261-272. [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, B., Olguntürk, N., & Aslanoğlu, R. (2020) Colour semantics in residential interior architecture on different interior types, Color Research & Application, 45(5), 941-952. [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, B., Olguntürk, N., & Aslanoğlu, R. (2021) Pairing colours in residential architecture for different interior types, Color Research & Application, 46(5), 1079-1090. [CrossRef]

- Valdez, P., & Mehrabian, A. (1994) Effects of color on emotions, Journal of experimental psychology: General, 123(4), 394. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0096-3445.123.4.394.

- van der Voordt, T., Bakker, I., & de Boon, J. (2017) Color preferences for four different types of spaces, Facilities, 35(3/4), 155-169. [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, K. , Müezzinoğlu, M. K. & İnan, B. (2021) Yatak Odalarında Farklı Geometrik Formların Kullanıldığı Duvar Panellerinin Kullanıcıların Algısal Değerlendirmeleri Üzerindeki Etkisi, Journal of Architectural Sciences and Applications, 6 (2) , 662-675 . Retrieved from https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/mbud/issue/66280/975412.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).