1. Introduction

The importance of assessing nurse’s workload, relies essentially in the opportunity of its management, allowing the contribution to improved health outcomes and care processes [

1], leading to fewer adverse events, fewer ethical and legal implications and lower costs [

2,

3] and, for nurses, reduces professional dissatisfaction, with increased levels of health and well-being at work [

4].

However, the concept of nursing workload isn’t clearly defined, and it’s used with different meanings, from: intensity of care, dependence, severity of health condition or complexity of care. Although many of these terms are used in a similar way, they tend to represent different aspects of the essence of care provided by nurses [

5]. Furthermore, the scope of this concept is not limited to direct care, but also includes other types of care: indirect care and professional development activities or organizational tasks [

6]. However, there is consensus that they all globally influence nurse’s workload [

7].

Therefore, challenges persist in the assessment of nurses’ workload. First, because it’s almost impossible to measure all nursing interventions. That makes it difficult to adopt a single method for determining workload. Workload assessment can thus be defined as a method of quantifying the activities, processes and time spent by nurses to provide care [

5].

Although there’s no ideal method for assessing nursing workload, the emotional aspects of work, should not be overlooked, because their potential usefulness seems to be important in the global assessment of workload [

7]. Therefore, workload assessment instruments must allow to identify and evaluate, in the most comprehensive way possible, without compromising their feasibility, the different variables that contributes to workload and, ultimately, enable the assessment of their impact.

The attempts, described in the literature, to assess nurses’ workload are essentially focused on the hospital environment, particularly in those with high differentiation of care, such as intensive care [

8,

9]. Furthermore, they focus essentially on direct care and usually include a prior assessment of both the clients’ dependence and complexity of care associated [

4].

However, for family nurses these metrics are not appropriate, either due to the diverse profile of clients to whom they provide care, or due to the lack of consensus regarding the essential characteristics associated with the workload concept in primary care. The aspects that seem to contribute to family nurse’s workload still remain unclear, with insufficiently studied variables persisting, which makes its assessment difficult [

5].

The comprehensive assessment of workload should incorporate the global care provided by family nurses, accommodating, among others, the aspects inherent to both the characteristics of the clients and nurses, the complexity of nursing interventions, the level of demand and the organizational environment [

10].

Furthermore, the association between workload and some of these aspects, specially, complex nursing diagnosis, the organizational workflow of care processes or the availability of resources, have not yet been studied in detail, within the scope of family nursing care.

Therefore, the ideal metrics to be used in family nurse’s workload assessment do not seem to be completely revised, in those that are traditionally the instruments used in hospital settings, thus requiring the identification of instruments and methodologies that more accurately reflect the contribution of several aspects of the family nurse’s workload [

4]. Knowledge in this area is, therefore, insufficient, and there are few studies focusing on evaluating nurse’s workload in the specific context of family health nursing.

Aware of this problem, we carried out a preliminary search in MEDLINE (via Pubmed), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Joanna Briggs Institute, Evidence Synthesis, PROSPERO, and Open Science Framework, which revealed a lack of literature reviews, published or to be carried out, in this specific problematic.

Since published studies on this topic are scarce and are dispersed in the literature, making it difficult to formulate precise questions, we decided to carry out a scoping review, with the aim of mapping the existing knowledge about the instruments to evaluate family nurse’s workload.

Specifically, this review aims to answer the following questions: “What instruments allows the workload assessment of family nurses?” and “What dimensions and variables are present in the workload assessment instruments of family nurses?”

Knowing the answers to these questions, will present fundamental contributions to the construction of workload assessment methodologies for family nurses.

2. Materials and Methods

This scoping review followed the methodological guidelines proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) [

11], and used Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [

12]. It was carried out over five stages: (1) definition of research strategy; (2) identification of relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) data extraction; and (5) presentation and discussion of results.

2.1. Search Strategy and Study Identification

In accordance with the JBI methodology, eligibility criteria were defined based on participants, concept and context (PCC). Regarding participants (P), studies were considered if focusing on family nurses who assume responsibility for providing global nursing care to individuals and families, threw out all stages of the life cycle. Regarding concept (C), we included studies that presented instruments that allowed the assessment of family nurses workload. As for the context (C), studies carried out within the scope of primary health care were included, particularly in practice environments of family nurses.

Regarding the type of study, we only considered primary and secondary quantitative studies, that used objective workload assessment instruments, excluding qualitative or mixed studies that described subjective assessment methodologies, such as interviews. Additionally, literature reviews, reports, thesis and dissertations, as well as gray literature, were considered. No time limit was defined as the aim was to encompass the entire corpus of knowledge on this issue.

Regarding the research strategy and identification of studies, the electronic databases CINAHL Complete (via EBSCOhost), MEDLINE (via Pubmed) and Scopus were used, given their relevance and, as they comprehensively cover the literature on this subject. The search for unpublished studies included the Portuguese Open Access Scientific Repository.

The search strategy aimed to locate published and unpublished studies and was carried out in three stages.

Initially, a conventional search was carried out, limited to the MEDLINE (via PubMed) and CINAHL Complete (via EBSCOhost) databases, to identify the ideal search terms.

Based on these terms and through the analysis of the words contained in the title, abstract and keywords, used to describe the articles found in the initial search, a complete search strategy was adopted. Using a process of gradual refinement, the aim was to combine the identified keywords and descriptors, adjusted according to the specificities of each database/repository included in the review, using boolean phrases to carry out the research. Combinations of MeSH descriptors were used using the boolean operators: “OR”, “AND” and the “*” tool, which enhanced the search by creating new variations of the same words. An example is shown in

Table 1

In the third stage, we analyzed the references list of all studies selected for critical evaluation in order to verify the existence of additional eligible studies.

We considered search for keywords in title and abstract in Portuguese, Spanish or English language publications, in full text, that identified instruments that evaluated the family nurse’s workload.

Because this scoping review is a secondary study, for which scientific evidence is made available in the public domain and, therefore, not involving human beings, it wasn’t considered necessary to request an opinion from an Ethics Committee.

2.2. Study Selection

After carrying out the search, all study titles were extracted and stored, using the Rayyan

® platform (

https://rayyan.qcri.org). Duplicate studies were eliminated and, subsequently, all titles and abstracts were read and analyzed, with the purpose of validating their relevance. Relevant full studies were retrieved, strictly following the review’s inclusion and exclusion criteria. Subsequently, the full text of the studies was evaluated in detail. With regard to identifying studies from reference lists, the same procedure was followed.

In case of doubt or disagreement, the full article was retrieved to decide about inclusion. Abstracts and posters published at conferences, as well as opinion articles, were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction

The extraction of specific details relating to the title, name of authors, country of origin, year of publication, objectives, type and design of the study, sample, characteristics of reported instruments (dimensions, variables and items), form of reporting and relevant results, was carried out using an extraction instrument built by the researchers, in accordance with the objectives and questions of this review.

3. Results

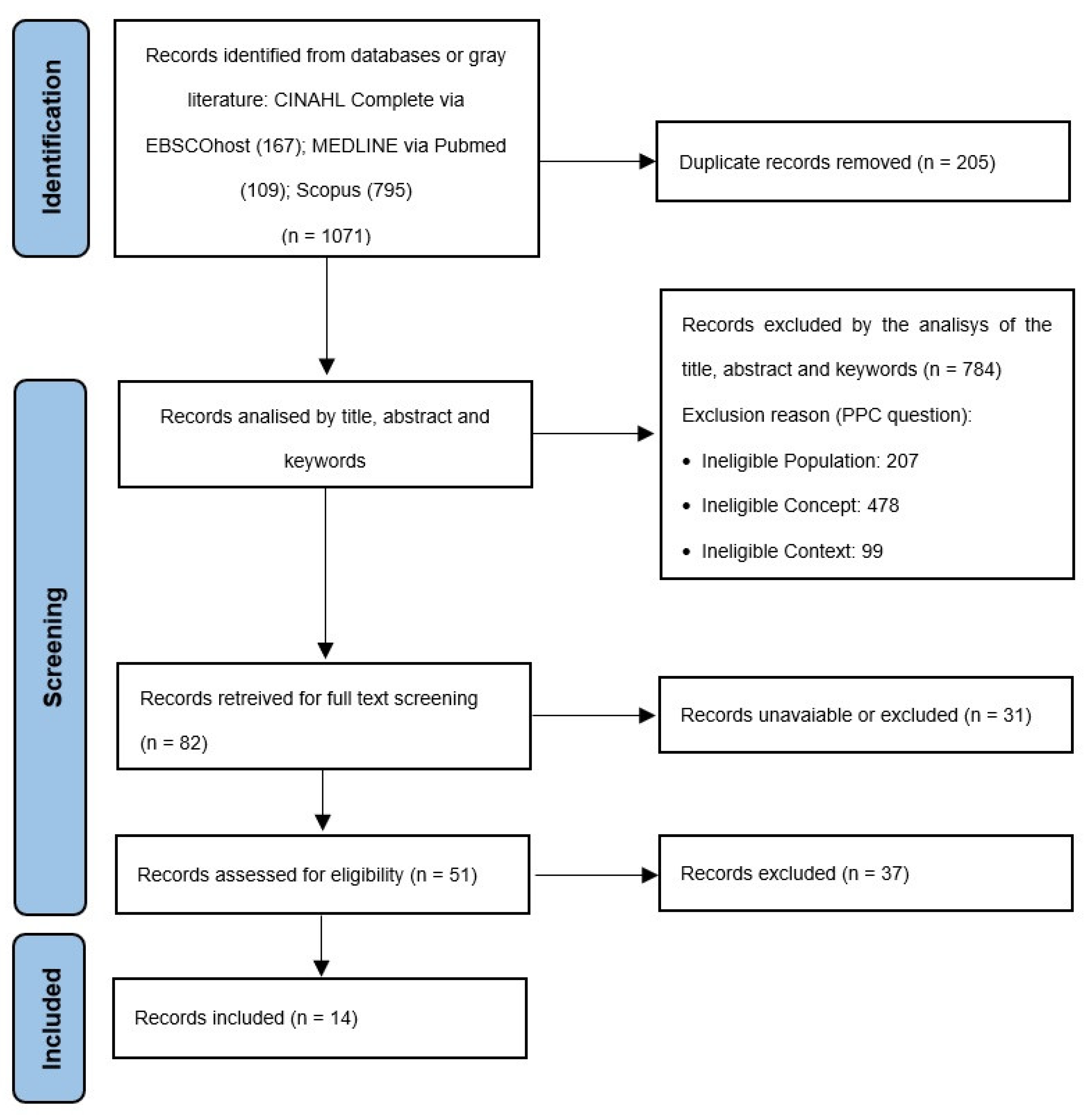

As shown in

Figure 1, the search identified 1071 potentially relevant studies, coming from the previously defined databases, with no studies being identified from gray literature search. Of these, 205 were excluded for being duplicates and, among the remaining 866 studies, 784 were removed after analyzing the title and abstract and 37 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria after reading the full text. In the end, 14 studies were included in the review.

Five studies originate in Spain and two in South Africa. The countries of origin of one study are also: Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Lithuania, Taiwan, India, United Arab Emirates and China. The publication of the included studies occurred between 2002 and 2021. There is an intensification of studies in more recent years, with 2018 having the highest concentration of included studies, with three studies. Ten studies are in English language, three in Spanish and one in Portuguese. Regarding the methodological design, eight included studies were correlational, three were descriptive, one was methodological, one was a cohort study and one was an integrative literature review.

The number of nurses that embodies the samples of the included studies totals 4304 nurses, whose main activity focuses on caring for families, with the smallest sample comprising 64 nurses and the largest comprising 969 nurses.

The fourteen studies included refer to ten self-report assessment instruments. Nine of these instruments analyze workload as a component or dimension, of a broader instrument, whose main objective was to evaluate another conceptual construct, such as stress, moral stress, burnout, quality of professional life or professional satisfaction, presenting heterogeneous structures.

Only two studies refer to the same instrument (Quantitative workload inventory) which focuses exclusively on workload and even in these cases, as an integrating part of a multidimensional questionnaire whose objective was to assess family nurses burnout.

The number of items in the instruments included varies between 5 and 12 and the most common response format is the five-point Likert scale.

No studies comparing instruments were found.

The different studies analyzed are summarized in

Table 2.

4. Discussion

The studies included in this review allow us to state that there is still a gap in evidence regarding family nurse’s workload assessment [

1,

13,

18,

19,

24,

25]. Given the differences in nature of the care provided by family nurses, particularly when compared with the care provided in hospitals, we must use with caution the conclusions obtained from previous studies that analyze workload, as being a phenomenon with similar characteristics to these two care settings [

26,

27,

28].

The small number of studies included in this scoping review, when compared with other similar reviews for other care settings [

4,

28,

29,

30], seems to clearly demonstrate the lack of specific instruments for evaluate the family nurse’s workload.

This difficulty is due, in part, to the great latitude regarding the family nurses’ scope of action. The analyzed studies reported, in a heterogeneous way, a diverse range of professional skills of family nurses, which means that the skills, professional roles and competencies of Portuguese family nurses, that we considered as a basis for formulating our research questions, in accordance with the portuguese legal and normative framework [

31,

32,

33], may be configured differently in other countries and health systems [

34], which can be seen as a limitation to the present review.

Several studies included reflect this aspect in the instruments used [

1,

16,

18,

20,

24], making clear the wide range of skills, roles, competencies, and care performed by family nurses, introducing heterogeneity in the items that make up the workload assessment instruments.

In Portugal, family nurses, integrated into multidisciplinary health teams, assume responsibility for providing global nursing care to a limited group of families, in all the life-cycle health processes, in the various community settings, and each family nurse is entrusted to care around 300/400 families in a given geographical area.

The evolution of primary care in the United Kingdom, for example, allowed a stratification of care by settings, compartmentalizing nurses’ professional skills [

34,

35], referring to school nurses, health visitor nurses or district nurses. Other studies [

36,

37,

38] refer to public health nurses or, community nurses as professionals whose skills represent the core of nursing care provided at the primary health care level. The differences go beyond terminology, as they tend to reflect the philosophy present in each healthcare system, for primary health care nurses and the way they view family care. These differences also extend to the operationalization of health systems and the organization and planning of how care reaches populations, families or individuals in primary health care.

The realities are, therefore, unique. However, in this review, we seek the rigor of reporting studies that are aligned with the reality of nursing care provided to families in Portugal and that allow us to identify a great professional affinity in terms of autonomy, responsibilities and professional skills, with the role of family nurses in Portugal.

This review also identified, as reflected in the instruments that evaluate the family nurses perceived workload, the polysemy of this concept, confirming its wide range of coverage, which seems to point out to the need of a more globalizing and integrating perspective of the different aspects that are conceptually close and relevant to the workload construct. The operative definitions contained in the instruments are not consensual and, despite not being antagonistic, they refer to an overlap of premises or aspects that characterize them. The reviewed studies include a wide range of concepts that may not be directly related to each other, being conceptually independent, but that indirectly make up the overall perceived workload [

1,

13,

15,

16,

19,

22,

24]. An example of this, are instruments that point out factors such as: work pressure [

1,

13,

15,

17,

24], the pace of work [

16,

19], the time available to provide care [

1,

13,

15,

17,

24], the impact of work on family life [

21,

22,

23], staffing/professional ratios [

1,

13,

15,

17], carrying out administrative or non-care-related tasks [

13], physical, cognitive and emotional effort [

22] or, the availability of resources [

1,

25]. Some of these aspects are more prevalent in the revised instruments, however it’s premature to conclude that these are more significant than others for evaluating the family nurse’s workload.

This conceptual polysemy seems to dictate the difficulty of identifying specific instruments for evaluating workload in this care context.

All studies included in the present review mainly aimed to evaluate various aspects other than specifically family nurse’s workload, with this concept being assessed by two different ways: (1) with its own instrument (integrating a multidimensional questionnaire) or, (2) as a component of another instrument (in the form of a dimension), in a specific workload sub-scale. In fact, the instruments included aim to assess a varied set of constructs, such as: professional stress [

13,

14,

18,

19,

24], burnout [

1,

17], job satisfaction [

15,

21,

22,

23,

24] or, the quality of professional life [

16,

20,

25]. All of them are intended to represent dimensions of the family nurses care practices, which also includes workload.

Thus, the family nurse concept of workload encompasses a double scope, as it reveals itself to be a broad construct composed of several aspects and can also be seen as an essential component (together with others) in the assessment of even broader constructs, which contribute to defining and characterizing different dimensions of family nurses’ care practice.

The review carried out also allows us to list, as a result of the number of correlational studies included [

13,

15,

17,

18,

19,

22,

24,

25], the relationship between family nurses’ perception of workload and its main consequences. Burnout stands out [

17], professional dissatisfaction [

15,

22,

24], illness and professional absenteeism [

13,

18], the intention to leave the current workplace or even nursing [

19,

24] were the major workload consequences depicted in studies included in our review. The integrative review included [

1], also demonstrates the relationship between workload and the quality and safety of care provided by family nurses.

It should also be noted that, in some studies [

13,

15,

16], indirect care (non-patient related activities) contributes largely to the perception of workload, but is very difficult to assess, due to the subjectivity they involve. They ‘re even called the hidden or submerged face of workload [

10,

39,

40]. Among them, documentation of care stands out [

13] and also, carrying out administrative tasks [

15,

16].

In the instruments analyzed, a heterogeneous and diversified structure is evident which, despite not being the objective of this study, makes the comparison of studies unfeasible. We can therefore state that this fact attests to the absence of a standard instrument to assess the workload of family nurses. Even so, each instrument has advantages and disadvantages, therefore, it is important to highlight that, for the appropriate choice of an instrument, the focus must be on the assessment of the overall workload.

It also becomes evident, with the findings of this review, that the studies included are not based on a clearly defined theoretical framework. Only one study [

20] refers to Karasek ‘s Demand and Control Model as the conceptual framework used.

There are several theories and models that explain workload [

41]. Many of them dedicated to health settings [

42,

43]. Its focus of analysis varies between ergonomics and the impact of the volume of work on the physical and psychological conditions of workers, especially those more exposed to risk factors associated with the provision of care [

44]; the mental load associated with the complexity of tasks carried out [

45] and; the relationship between the demand for care and the availability of resources [

46]. It should be noted that there is today a tendency towards an integrative or globalizing perspective of the different dimensions that can shape workload perception, including in the same theoretical perspective: supply and demand, the cognitive complexity associated with the provision of care, the physical and emotional burden, the availability of resources and, among these, the time to perform care, as a broad, comprehensive and global perspective of the aspects that embody nurses workload assessment.

In conclusion, we consider that the set of studies included in the present review allow us to conclude that the multiplicity of professional skills of family nurses, exercised in highly diverse care environments, in the health systems where they operate, associated with the conceptual diversity of the workload concept, and the absence of a clearly defined theoretical framework, makes it difficult to identify unique or consensual instruments that allows family nurses workload assessment. It should be noted that these findings are congruent with existing evidence in this area [

26,

27,

28] and are in line with authors [

47] who stated that the complexity of nursing care and technological advances highlight the need to review and update workload quantification systems.

5. Conclusions

Workload assessment is an important factor that can contribute to improving the quality of nursing care provided. This review focused on existing instruments in the literature, which allows the assessment of family nurses workload, establishing a starting point for the analysis and systematization of the main evidence available on this area.

This review intends to contribute, as a preliminary exercise, to the identification of gaps in the literature that encourage carrying out future primary studies, optimizing research designs and methodologies, that justifies the formulation of new questions, and that way promoting the development of knowledge in Nursing, in this matter.

Our review demonstrates that, in addition to the heterogeneity and the small number of instruments that quantitatively assess the workload of family nurses, there’s no broad consensus on which instrument is best, making comparison of results unfeasible.

For this reason, this review intends to establish a guide, as it highlights the importance of deepening the knowledge on this issue to obtain reliable, broad and integrative instruments of the overall care provided by family nurses, which allows an inclusive and comprehensive portrayal of the care provided, clarifying which dimensions of workload are most relevant to be measured by nurses in the practice scenario in question.

As limitations to the present review, we can state that the literature on workload is complex, with a wide variety of constructs and operationalizations to represent it, often with little coherence in the use of terminology. This means that there may be terms that belongs to the workload domains that we did not included in the search. As a result, there are instruments that may have been overlooked by the procedures we followed. Likewise, our results may also be influenced by a certain degree of reporting bias, as researchers may be less willing to publish unfavorable results in terms of the psychometric properties of an instrument.

Another of the limitations that we can point out, refers to the lack of studies focusing on the professional settings of family nurses, since the existing evidence seems to still be scarce, particularly when compared to that produced in the hospital setting. It is therefore evident that this issue is still little explored, reflecting a gap to be filled with future research.

The authors of the proposed study reveal that they have no relationship with funding institutions or others that may benefit from their results and that could generate potential conflicts of interest.

Public Involvement Statement:

No public involvement in any aspect of this research.

Guidelines and Standards Statement:

This manuscript was drafted according to the recommendations of The Joanna Briggs Institute for scoping review research.

Use of Artificial Intelligence:

AI or AI-assisted tools were not used in drafting any aspect of this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.D., B.A., and E.J.; methodology, A.D., B.A., and E.J.; Results, A.D.; Discussion, A.D., B.A., and E.J.; Conclusion, A. D.; writing—original draft preparation, A.D.; writing—review and editing, A.D., B.A., and E.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Pérez-Francisco, D.; Duarte-Clíments, G.; Del Rosario-Melián, J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Romero-Martín, M.; Sánchez-Gómez, M. Influence of Workload on Primary Care Nurses' Health and Burnout, Patients' Safety, and Quality of Care: Integrative Review. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland) 2020, 8, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holland, P.; Tham, T.L.; Sheehan, C.; Cooper, B. The impact of perceived workload on nurse satisfaction with work-life balance and intention to leave the occupation. Appl. Nurs. Res. 2019, 49, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegney, D.G.; Rees, C.S.; Osseiran-Moisson, R.; Breen, L.; Eley, R.; Windsor, C.; Harvey, C. Perceptions of nursing workloads and contributing factors, and their impact on implicit care rationing: A Queensland, Australia study. J. Nurs. Manag. 2019, 27, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, P.; Saville, C.; Ball, J.; Jones, J.; Pattison, N.; Monks, T. Nursing workload, nurse staffing methodologies and tools: A systematic scoping review and discussion. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2020, 103, 103487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alghamdi, M.G. Nursing workload: a concept analysis. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, R.; MacNeela, P.; Scott, A.; Treacy, P.; Hyde, A. Reconsidering the conceptualization of nursing workload: literature review. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 57, 463–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.; Rogers, C.; King, C. Safety culture and an invisible nursing workload. Collegian 2019, 26, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, P.; Kiliç, I. The Psychometric Properties of the Turkish Version of Individual Workload Perception Scale for Medical and Surgical Nurses. J. Nurs. Meas. 2022, 30, 778–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habbab, M. S. , Martín G. I., Vilamala, I. R., Llorente, S., Díaz, C. R., & Calero, M. F. (2020). Análisis de las cargas de trabajo de las enfermeras en la UCI gracias a la escala NAS. Enfermería En Cardiologia, 27(81), 32–37.

- Biff, D.; de Pires, D.E.P.; Forte, E.C.N.; Trindade, L.d.L.; Machado, R.R.; Amadigi, F.R.; Scherer, M.D.d.A.; Soratto, J. Nurses' workload: lights and shadows in the Family Health Strategy. Cienc. Saude Coletiva 2020, 25, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.; Godfrey, C. , McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A., C., Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews (2020). Aromataris E, Lockwood C, Porritt K, Pilla B, Jordan Z, editors. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2024. Available from: https://synthesismanual.jbi.global. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alenezi, A.M.; Aboshaiqah, A.; Baker, O. Work-related stress among nursing staff working in government hospitals and primary health care centres. Int. J. Nurs. Pr. 2018, 24, e12676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, P.O.; Ramos, F.R.S.; Barlem, E.L.D.; Dalmolin, G.d.L.; Schneider, D.G. Validation of a moral distress instrument in nurses of primary health care. Rev. Latino-Americana de Enferm. 2018, 26, e3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bester, C.L.; Engelbrecht, M.C. (2009) Job satisfaction and dissatisfaction of professional nurses in Primary Health Care facilities in the Free State Province of South Africa. Africa Journal of Nursing and Midwifery 11(1) pp. 104-117. http://hdl.handle.net/10500/9822.

- Rubio, J.C.; Fernández, J.M.; Páez, M.M.; Muñoz, M.C.; Cobo, J.G.; Balo, A.R. Clima laboral en atención primaria: ¿qué hay que mejorar? Atencion primaria 2003, 32, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelbrecht, M.; Bester, C.; Berg, H.v.D.; van Rensburg, H. A study of predictors and levels of burnout: The case of professional nurses in primary health care facilities in the free state. South Afr. J. Econ. 2008, 76, S15–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdikienė, N.; Asikainen, P.; Balčiūnas, S.; Suominen, T. Do nurses feel stressed? A perspective from primary health care. Nurs. Heal. Sci. 2014, 16, 327–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- I, L.; Wang, H.-H. Perceived Occupational Stress and Related Factors in Public Health Nurses. J. Nurs. Res. 2002, 10, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Fernandez, J.; Gomez-Gascon, T.; Beamud-Lagos, M.; Cortes-Rubio, J.A.; Alberquilla-Menendez-Asenjo, A. Professional quality of life and organizational changes: a five-year observational study in Primary Care. BMC Heal. Serv. Res. 2007, 7, 101–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panadero, A. C. , & Madroño, M. Á. C. (2012). Work-related satisfaction of nursing professionals in Talavera de la Reina. Metas de Enfermería, 15(10), 63-68.

- Purohit, B.; Lal, S.; Banopadhyay, T. Job Satisfaction Among Public Sector Doctors and Nurses in India. J. Heal. Manag. 2021, 23, 649–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, S; Adam, S. (2020). Job Satisfaction among Nurses Working at Primary Health Center in Ras Al Khaimah, United States Emirates. International Journal of Nursing Education, 12(1).

- Tao, L.; Guo, H.; Liu, S.; Li, J. Work stress and job satisfaction of community health nurses in Southwest China. Biomed. Res. 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, A. V. , García, T., Zuzuárregui, M. S. G., Sánchez, S. S., & Conejo, R. O. (2015). Professional quality of life in workers of the Toledo primary care health area. Revista de Calidad Asistencial, 30(1), 4-9.

- Brady, A.-M.; Byrne, G.; Horan, P.; Griffiths, C.; Macgregor, C.; Begley, C. Measuring the workload of community nurses in Ireland: a review of workload measurement systems. J. Nurs. Manag. 2007, 15, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonfim, D.; Pereira, M.J.B.; Pierantoni, C.R.; Haddad, A.E.; Gaidzinski, R.R. Instrumento de medida de carga de trabalho dos profissionais de Saúde na Atenção Primária: desenvolvimento e validação. Rev. da Esc. de Enferm. da USP 2015, 49, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swan, B.A.; Griffin, K.F. Measuring nursing workload in ambulatory care. . 2005, 23, 253–60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sousa, C.; Seabra, P. Assessment of nursing workload in adult psychiatric inpatient units: A scoping review. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Heal. Nurs. 2018, 25, 432–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwiecień, K.; Wujtewicz, M.; Mędrzycka-Dąbrowska, W. Selected methods of measuring workload among intensive care nursing staff. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Heal. 2012, 25, 209–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Despacho nº 10321/2012 de 1 de agosto. Diário da República nº 148/2012 - II Série. Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa.

- Regulamento, n. º 126/2011, de 18 de fevereiro, publicado pela Ordem dos Enfermeiros em Diário da República, 2.ª série, n.º 35.

- Decreto-Lei nº 298/2007 de 22 de agosto. Diário da República nº 161/2007-I Série A. Ministério da Saúde: Lisboa.

- Dellafiore, F.; Caruso, R.; Cossu, M.; Russo, S.; Baroni, I.; Barello, S.; Vangone, I.; Acampora, M.; Conte, G.; Magon, A.; et al. The State of the Evidence about the Family and Community Nurse: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2022, 19, 4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traynor, M.; Wade, B. The development of a measure of job satisfaction for use in monitoring the morale of community nurses in four trusts. J. Adv. Nurs. 1993, 18, 127–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, L.; Leggat, S.G.; Cheng, C.; Donohue, L.; Bartram, T.; Oakman, J. Are organisational factors affecting the emotional withdrawal of community nurses? Aust. Heal. Rev. 2017, 41, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, F.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, P.; Liang, Y. Work characteristics and psychological symptoms among GPs and community nurses: a preliminary investigation in China. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2016, 28, 709–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.R.; Davies, B.L.; Woodend, A.K.; Simpson, J.; Mantha, S.L. Impacting Canadian Public Health Nurses’ Job Satisfaction. Can. J. Public Heal. 2011, 102, 427–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, P.; Cucolo, D.F.; Perroca, M.G. Nursing workload: influence of indirect care interventions. Rev. da Esc. de Enferm. da USP 2019, 53, e03440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myny, D.; Van Hecke, A.; De Bacquer, D.; Verhaeghe, S.; Gobert, M.; Defloor, T.; Van Goubergen, D. Determining a set of measurable and relevant factors affecting nursing workload in the acute care hospital setting: A cross-sectional study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2012, 49, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funke, G.J.; Knott, B.A.; Salas, E.; Pavlas, D.; Strang, A.J. Conceptualization and Measurement of Team Workload. Hum. Factors: J. Hum. Factors Ergon. Soc. 2012, 54, 36–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Longo, L.; Wickens, C.D.; Hancock, G.M.; Hancock, P.A. Human Mental Workload: A Survey and a Novel Inclusive Definition. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 883321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Groot, K.; De Veer, A.J.E.; Munster, A.M.; Francke, A.L.; Paans, W. Nursing documentation and its relationship with perceived nursing workload: a mixed-methods study among community nurses. BMC Nurs. 2022, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, A.C. , & Noriega M. (1989). Processo de produção e saúde: trabalho e desgaste operário. Hucitec; São Paulo: Brasil.

- Silva, C.C.; de Minas, F.P.; Bonvicini, C.R. Dejours, C. , Abdoucheli, E., & Jayet, C. (2014). Psicodinâmica do Trabalho (1a ed.). São Paulo: Atlas. 2014, 4, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 2017, 22, 273–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quintana, J.C.F.; Sarmiento, M.C.; Mora, Y.; Leguizamon, L.M.T. Validación facial de la escala Nursing Activities Score en tres unidades de cuidado intensivo en Bogotá, Colombia. Enfermería Global 2017, 16, 102–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).