1. Introduction

Social innovation is directed change. However, this is determined by both exogenous and endogenous factors [

1,

2,

3]. Although exogenous conditions in the vast majority of cases constitute an independent variable in relation to the social or organisational context analysed, endogenous conditions are usually influenced by participants in organisational activities. The article will devote more attention to the endogenous conditions of innovative processes in the area of activity of non-governmental organisations. The literature on the subject contains several conceptualisations on endogenous determinants of innovation development, including social innovations [

4,

5,

6,

65]. Key determinants are generally considered: organisational culture, the potential for social and creative capital, the aspirations and educational needs of the community, in addition to ensuring the possibility of their continuous satisfaction by the educational system, and the quality of local public institutions (including non-governmental organisations) that create the institutional microenvironment of innovation [

7].

Barriers to agency resulting from faculty activities in the area of innovation in the organisation will be analysed from a specific cognitive perspective. First, from the point of view of people defined in the conceptual convention of Margaret Archer's morphogenetic theory as collective subjects of action, that is, participants of organisations with a high potential for agency, as opposed to the perspective of primary subjects of action, that is, participants of organisations with a low potential for agency [

8,

9,

10,

11]. The agency of executive entities has subjective and intentional characteristics that should be associated with their reflexivity. Hence, following Archer, he uses the concept of communicative reflexivity, focused on maintaining the existing social status quo, and autonomous reflexivity, focused on change. At the same time, the agency is determined and conditioned by the environment, its structural and cultural properties [

12,

13,

14,

15]. The constitutive feature of agency understood in this way is not only the ability of the entity to act, but is expressed in the very existence of this entity [

8,

16,

17]. The agency understood in this way creates conditions for innovation. It leads to innovation, provided that the appropriate structural and cultural conditions are met. This is a necessary but not sufficient condition for innovation to occur. It is important to determine under what structural and cultural conditions and under what type of reflexivity and the related agency of the entities studied that such innovation occurs.

The authors distinguish two types of agency barriers: structurally conditioned (objectified) and awareness barriers. The first type of barriers is determined by the contexts resulting from the infrastructural, economic, intellectual, communication and digital potential of the members of the surveyed non-governmental organisations. Barriers of the second type concern the respondents' state of mind, attitudes towards undertaking social innovations (pro- and anti-innovation), attitudes towards innovation participants (e.g. trust and normative community or distance and jealousy), attitudes towards the need to build social ties in micro, meso, and macroenvironment. (bridging or link social capital). Effective implementation of innovations requires special involvement of innovators, users, and recipients, positive feedback between these entities. In other words, the interaction between the conscious component and the objectified agency and the structural and cultural conditions. In the surveyed nongovernmental organisations, the above requirements are ensured thanks to the pro-sumer attitude of their leaders and members. The agency of individuals and social groups, deprived of adequate resources of economic, social and cultural capital sufficient for their organisational agency, is inhibited by these emergent properties.

To examine the functioning of the Polish civil society, including its most institutionalised form, nongovernmental organisations, it is necessary to take into account the existing elements of both bridging and binding social capital. Perhaps defining the role of the latter is the key to explaining the Polish specificity of civic participation, also in the sphere of nongovernmental organisations. Based on our own previous research and the existing literature on the subject, it seems advisable to present a thesis on the existing type of social capital as a key cultural condition shaping the functioning of Polish civil society [

18,

19,

20,

21].

There are many empirical sources justifying the thesis on the dominance of social relations based on the binding rather than the bridging type of social capital in Polish society. As shown by many years of research (including CBOS, GUS, Social Diagnosis), in Poland since the political transformation [

20,

21,

22], despite a several-fold increase in GDP per capita and a relatively high level of schooling rates, or, more broadly, human capital, there has been no increase in the level of social capital, especially its pro-innovation and inclusive nature. Varieties [

23]. Research published in 2020 by the Central Statistical Office, in which associational (bridging) and informal capital (family, neighbourhood, and social capital, i.e., defined as applicable in Putnam's conceptual convention) were analytically distinguished, shows that only 12% of respondents aged 16 and over declared that they belonged to or identified with nongovernmental organisations. Much more of the respondents' declarations, 82%, concerned the components of informal (family) capital, measured mainly by the degree of emotional bond, frequency of contacts, and the degree of mutual help and support. Hence, the conclusion that in Poland the strongest element of network social capital is bond capital, or more precisely, its family component. Second, in maintaining social networks, are the elements of bonding capital in one's neighbourhood and social diversity (approximately 62% of responses). Its bridging type has the smallest contribution to building social capital (e.g. measured by the level of participation in social organisations and the degree of generalised trust in people) [

21,

22,

23].

These observations are also confirmed by comparative research from the European Social Survey [

24]. The level of general trust of citizens and the scale of their membership in nongovernmental organisations, as the main indicators of bridging social capital in Poland in relation to analogous indicators in other European Union and OECD countries, has remained one of the lowest for years and usually amounts to 10-15 percent. It seems reasonable to learn what types of social capital dominate among people actively involved in the activities of nongovernmental organisations.

Research on institutionalized manifestations of the functioning of civil society was carried out in a specific region of Poland. Upper Silesia is the most urbanised part of Poland, whose population lives mainly in large and medium cities (over 100,000 inhabitants). The population of the region is diverse both in terms of nationality and ethnicity. In a cultural sense, it constitutes the Polish-German-Czech border. Until recently, it was the largest industrial region in the country, dominated by heavy industry (metallurgy, machinery, and armaments) and energy industry, based on the mining and refining of hard coal and metal ores. Currently, it is moving more and more towards a post-industrial area and is undergoing intensive restructuring towards Economy 4.0 and Society 5.0. Non-governmental organizations are also developing dynamically in the region. However, lasting processes of political transformation are accompanied by social tensions characteristic of a society entering the postmodern phase and are reflected in socioeconomic relations in public institutions, enterprises, and organisations operating in the region.

With reference to the presented data and observations, the authors will attempt to diagnose two endogenous conditions shaping the causative and innovative possibilities in the state of organisational morphostasis (contextual continuity) and morphogenesis (contextual discontinuity) of collective action entities from selected Silesian nongovernmental organisations: (1) potentials of binding and bridging capital social (in the area of trust, norms, and connections), (2) types of reflexivity, and the nature of agency related to them.

2. Literature on the Subject: Social Capital, and Innovation

From a sociological point of view, the key factor determining the innovation potential of a given group or organisation is its social capital potential. This is an important conceptual category, both in the theoretical and operational dimensions, for analysing the relationship between structural and cultural conditions and the agency of the researched entities affected by the contexts and effects of ressentiment. Therefore, the concept of social capital and the operationalisation of the key variables that describe it will be conceptualised. The components of social capital existing in a given cultural context constitute, in Archer's approach, the cultural system (ideas) and its sociocultural, interactive manifestations (actions). Pattern forms of social capital developed over time, such as generalised trust and a community of values, are a component of the cultural system, that is, a set of ideas. They can be treated as social facts. However, sociocultural interactions and activities undertaken should take into account the remaining element of the definition of social capital, conceptualised after James S. Coleman [

25], i.e., social connections and networks. This last definitional element, i.e. connections and networks, simultaneously belongs to and characterises the structural and cultural properties of a given community, because on the one hand, it indirectly reflects the position of individuals in access to power, possession, and prestige, and on the other hand, it reflects the specificity of socio-cultural interactions related to the implementation of specific ideas and values (cultural system) in action. Therefore, the relationships that connect the social capital potentials of selected nongovernmental organisations with the structural and cultural contexts (barriers) that determine their morphogenetic abilities, including the innovative ones, will be characterised. The authors also intend to demonstrate that the quality of specific forms of social capital (trust, norms, and connections) determines the effects of social innovations.

Social capital resources, in addition to human and economic capital and, to a lesser extent, cultural capital [

23], are widely believed to play a decisive role in the sustainable development of local communities, regions, and societies, but also strengthen innovative processes, including social innovation [

26,

27,

28,

29]. The literature on the subject contains several dozen ways of defining social capital, the sources of which can be traced back to the beginning of the twentieth century [

30,

31]. The main macrostructural theoretical paradigms include two dominant concepts of this concept: conflict theory and functionalism. The first emphasises the importance of individual resources and exclusive group resources (environmental, social, corporate), which testify to existing structural conditions, divisions, inequalities, tensions, and conflicts, and not to a community of values or interests. Social capital understood in the convention of the conflict paradigm according to Pierre Bourdieu [

32] are resources that an individual acquires during participation in more or less institutionalised groups that provide their members with support in the form of a lasting network of relationships based on knowledge and mutual relations. recognition. According to Bourdieu, the position of an individual in the social structure is also determined by other types of capital: economic, cultural, and the resulting symbolic capital [

32].

Today, more and more researchers are emphasising the particular importance of the social relations network for multiplying individual resources of social capital. These are resources embedded in a social network, understood as part of the structural context [

33]. Janine Nahapiet and Sumantra Ghoshal define social capital as the sum of current and potential resources resulting from the network of connections that connect operating entities [

34]. According to Lin, social capital is both the resources that specific individuals or groups have in the network and the structure of their contacts. In other words, Lin sees social capital as an attribute of the social structure: "resources built into the social structure that can be achieved or mobilised through purposeful action" [

35]. Social capital understood in this way has its roots in social networks and relationships. However, Burt claims that the network consists of positions and social relationships in the network that provide access to specific resources and their flow within the social structure [

36,

37]. Both resources and relationships are important for a comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon of social capital. Therefore, it seems appropriate to clarify that these resources, as the results of individual or group activities in the network, are of a material (wealth), cultural (prestige), or political (power) nature. They have the potential to consolidate the existing social status quo (morphostasis) and introduce changes (morphogenesis).

The second theoretical trend in research on social capital emphasises the importance of generalised trust and collective actions based on it, which are socially resource-creating, integrating, inclusive, building bonds, and networks of connections, created on the basis of an axionormative community. Contemporary integrative concepts of social capital, most often drawing on the "associative" inspirations of A. de Tocqueville, focus mainly on finding answers to the question about the sources of the effectiveness of social institutions and identifying ways that allow given communities to solve problems, encounter innovations, and implement them. Coleman was one of the first to emphasise the integrative aspect of social capital. Already in the 1980s, in parallel with P. Bourdieu, the creator of the oppositional conceptualisation of social capital, introduced the above concept to the resources of sociological theories.

According to Coleman, the strength and scope of the bonds and networks of social relationships are determined by trust between actors of social, economic, and public life, the normative community and institutional, group and personal connections [

38]. By analogy to material or human capital (e.g. know-how), he stated that social capital is productive because it enables the achievement of social goals to a greater extent than when it is unavailable. He claims that in addition to knowledge and skills, a significant part of human potential is the ability to create groups to achieve a set goal. In turn, the ability to form groups depends on the extent to which a given community recognises and shares a set of norms and values and on the extent to which members of this community are willing to sacrifice part of their individual good for the common good. Sharing the same views and values is the basis of trust, "social capital, which often translates into economic capital" [

39].

Robert Putnam, also a classic, understands social capital in a functionalist and integrative way. Refers to features of social organisation, such as networks, norms, and social trust, that facilitate coordination and cooperation within networks. Explains the concept of social capital in the context of rational choice theory, or rather overcoming the dilemmas of collective action. He distinguishes two basic strategies of social action that lead to balance, self-sufficiency, and durability of social systems. The first strategy is "never cooperate", and the second strategy is the opposite, "collaborate". Strategy 2, in which 'social capital activities such as trust, norms, and networks of associations tend to be self-reinforcing and cumulative. Positive feedback leads to social balance characterised by high levels of cooperation, social trust, reciprocity, civic participation, and shared prosperity [

40]. These characteristics define a civic community. Both positive and negative relationships determine the functioning of specific communities, but the level of effectiveness of each of them varies.

Putnam introduces an important theoretical and analytical distinction between two types of social capital: bonding and bridging, which will be helpful in the morphogenetic causal analyses of the emergence of the effects of resentment presented below. Bond capital is characterised by primary groups: families, neighbourhood groups, social groups, and exclusive groups connecting individuals with similar sociodemographic characteristics who have personal trust in each other, excluding different people. Bridging capital is more universal. Connects people and groups with various sociodemographic characteristics. It allows you to build lasting bonds and networks of supragroup and intergroup ties. This is particularly important for building communities, organisations, and public institutions open to broadly understood innovations. The authors briefly and precisely describe its role: "Broadband capital can expand the boundaries of individuality (identity) and reciprocity" [

40].

F. Fukuyama looks at society from a similarly integralist perspective. Author of the work Trust. Social capital and the path to prosperity claim that the economic prosperity of nations and the ability to compete on the global market are conditioned by one cultural feature, the level of social trust of individual actors (individual or collective) in each other in a given society. However, social capital, i.e., norms of reciprocity, moral obligations, and trust, is based on custom, not rational calculation. Social capital is renewable, but only if it is culturally and normatively based [

41].

The literature on the subject also includes concepts critical of the functionalist trend, defining the effects of too strong social ties and resources; e.g., as negative social capital or the concept of two types of social capital resulting from rootedness and autonomy [

42,

43], which appeared in the context of criticism of Putnam's approach [

44]. These concepts are based on a critique of the position that social capital is a common good that positively affects all areas of social life: human capital, productivity, economic success, democratic governance, and individual well-being, in general speaking, all aspects of human life [

45]. The allegations are based on premises that may arise as a result of a level too high of one type of social capital in particular. They concern, among others, discrimination of individuals outside the dominant group, resulting from the process of favouring participants of a given social structure, which has too much potential to bind social capital [

46]. Pragmatics that limit freedom, innovation, entrepreneurship, and creativity also play an important role due to the excess of bonding social capital existing in closed, traditional or extremely fundamentalist groups [

47]. It is also important to limit the access of people outside the group to resources, to appropriate certain goods, to demand a share of profits by demanding the employment of relatives and friends (nepotism), and to risk perceiving individual success as a threat to group cohesion [

48,

49].

Too large resources of binding social capital also favour the occurrence of amoral professionalism, which involves applying to external individuals rules that go beyond moral and ethical norms and differ from those prevailing within the group (e.g. mafia activities, discrimination of ethnic minorities, manipulation of access to information to achieve one's own benefits etc.) [

50]. In addition, they promote corruption in enterprises, including organising tenders or conducting activities that favour stakeholder groups that practise hiding information from other participants. This phenomenon is associated with a high level of trust, leading to a greater sense of security and information retention within the group [

51,

52,

53]. There are also pathological lobbying behaviours, such as interest groups seeking to shape legislation and placing their own benefits ahead of the good of society as a whole, including trade unions, professional corporations, lobbying groups [

54].

Taking into account the dysfunctional elements of trust capital, bonds, and social norms that are not resource-generating for a given community allows us to avoid accusations of a one-dimensional image of reality levelled against representatives of purely integrative concepts. Therefore, a distinction is made between opposing forms of social capital: those that create resources and those that do not create resources.

The author's operational definition of the concept of innovation is based on a pragmatic approach to truth. It accepts as true what works through its practical consequences. It is close to being identified with the effectiveness, efficiency and adequacy of satisfying human needs in a specific situational context. Pragmatically understood, social innovation emphasizes the importance of the effects of social activities, the importance of activities focused on action research, i.e. research, action and cooperation [

2,

7,

68]. The above-mentioned approach to social innovation includes the diagnosis of reality, identification of the problem, initiation, testing, implementation and possibly validation of the final product of the innovation (i.e. product, service, model), which in effect leads to a permanent and significantly predicted change in a specific environment, social group, or organisation. It is achieved through cooperation and mutual inspiration of innovators, users, and recipients.

This understanding of social innovation is the basis of operational applications. A social innovation is defined as an activity/model/service that is characterized by at least most (i.e. 5 out of 9) of the following features: intersectorality, openness and cooperation, prosumption and co-production, interdependence, creation of new social roles and relationships, bottom-up, more effective use of means and resources, development of new resources and opportunities, use of ICT technologies and tools in social and organizational communication.

3. Methodological Assumptions, and Framework of the Research Procedure

With reference to the above conceptualisations of social capital and selected assumptions of Margaret Archer's morphogenetic theory of structure and agency, two research questions were asked: (1) What elements of bonding and bridging social capital (in the area of trust, norms, and connections) determine innovative activity in the state of morphostasis (contextual continuity) of selected nongovernmental organisations? (2) What type of reflexivity and the related nature of agency dominates when undertaking innovative activities among entities operating in the surveyed nongovernmental organisations?

The results were analysed and interpreted in relation to the following research questions according to the scheme: 1) organising raw data, i.e., creating an integrated text document from interview transcripts, 2) data descriptions (coding and creating a code family), 3) interpretation of the code family's perceptual maps. The sequence of research within the interview method used, the qualitative technique, the focus group interview (FGI), was determined through a focus group scenario in which the main research questions were operationalised. The interviews were conducted in the form of discussions under the supervision of a moderator and focused on the main thematic threads determined by the research questions.

An inductive method of analysing the collected research material was used. Therefore, no preliminary assumptions were made regarding the nature of the relationships between the variables, and no hypotheses were formulated that could be verified during focus groups. The Atlas.ti computer programme was used to analyse the collected empirical data, which allowed us to graphically present the frequency distributions of opinion categories appearing in FGI and the connections between them.

The selection of people for the research groups was purposeful. This means that obtaining fully representative statistically significant distributions of sociodemographic characteristics in the composition of individual focus groups was not as important as saturation with people with the most diverse and well-established attitudes, knowledge, judgments, and opinions on the scope of agency and innovative activities in the studied groups. Nongovernmental organisations, limitations in communication within the organisation, and building relationships with the environment. It was also assumed, in accordance with the principles of grounded theory, that the data collected in individual groups would be continuously compared with each other to extract codes from the focus groups that organise and interpret the research material. More general categories were then constructed (through grounding in similar cases) to show the connections between the categories [

55,

56].

Focus groups were held in 2022. They covered 48 Silesian NGOs. A total of 48 focus group interviews were conducted with representatives of each of the organisations surveyed separately. Purposive selection was applied to the research sample, in such a way that in each focus group there were equal proportions of representatives of both the management board and the rank and file members. 192 people participated in the qualitative study of the FGI, including 96 leaders (presidents and board members of nongovernmental organisations) and 96 members of nongovernmental organisations. When selecting nongovernmental organisations for the research sample, an equal percentage of organisations from metropolitan (cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants), urban (from 30,000 to 100,000 inhabitants) and small-town and rural (less than 30,000 inhabitants) environments were taken into account. Respectively, rural environments and small town environments were represented by organisations from Poręba, Łazy, Wojkowice, Lubliniec and Mikołów, from medium-sized cities, organisations from Tarnowskie Góry, Mysłowice, Zawiercie, Piekary Śląskie, and as representatives of metropolitan environments, respondents came from Katowice, Sosnowiec, Gliwice, Bytom, Chorzów, Rybnik. Furthermore, the configuration of the research sample included a variable: the main area of activity of the organisation. Therefore, nongovernmental organisations were selected in equal proportions for the focus research, four organisations each from the six areas of activity most frequently represented among all Polish nongovernmental organisations, ie, from the area of charity and health promotion activities, education and education, sports and recreation, religious organisations, and communities (incl. including parish), local governments (districts, housing estates, housing communities) and animal care [

22].

An additional criterion for selecting a given organisation for the research was its documented implementation of at least one social innovation in the last two years before the start of the research.

Such innovation should be characterised by at least five of the nine parameters: cross-sectorality, openness and cooperation, prosumption and co-production, interdependence, creation of new social roles and relationships, bottom-up, more efficient use of means and resources, development of new resources and opportunities, use of ICT technologies and tools. A social innovation was granted the status of implemented when a given project underwent a final external evaluation, e.g., carried out by an intermediate body representing the European Union or national authorities, appointed to distribute funds for individual social programmes.

The group interview scenario included questions about the type of barriers and conflicts hindering the introduction of innovations in the organisation and its environment, the importance of personal and group jealousy and distrust in the implementation of innovations, the existence of social capital components (connecting and bonding diversity), such as trust in generalised others, the nature of connections with the socioeconomic environment, local government authorities, the way of understanding the common good. The main scope of issues constituting the FGI scenario is presented in the Appendix.

In the following, the elements of the morphogenetic causal analysis model will be presented, constructed based on the assumptions of Archer's theory of structure and agency and conclusions from the research of nongovernmental organisations [

3,

11]. It explains the course of two scenarios of working through the structural and cultural context by the participants of the studied nongovernmental organisations: morphostatic (durability) and morphogenetic (changes). Provided a general methodological framework for synthesising and interpreting qualitative data on structural barriers and awareness to agency. It will be used to determine what type of reflexivity and the related nature of the agency dominate when respondents undertake innovative activities.

Morphostatic scenario

The distribution of structural, cultural, and agency forces contributes to organisational morphostasis when there is compliance of actors in terms of existing relationships between the structural context (group interests) and the cultural context (dominant ideas and values focused on the survival of a social group) or there is acceptance of tensions between structural and cultural contexts. This division blocks the development of new collective entities and changes in the continuity of organisational contexts.

In the case of an organisation in a state of morphostasis, that is, the persistence of the basic interests and values of its members, the existing structural and cultural contexts limit the emergence of innovations (an indicator of the state of morphostasis are attitudes focused on maintaining the organisational status quo).

Indication of the dominant type of reflexivity. The course and effects of potential innovative activities are also the result of the reflexivity of organisation members who make decisions in the context of an individual approach to their practical projects in relation to existing contexts.

The morphostatic experience of contextual continuity is perpetuated by the dominance of the communicative type of reflexivity. An indicator of the existence of communicative reflexivity is that respondents emphasise the importance of structurally determined barriers more than possibilities of overcoming them by members of the organisation; lack of trust in the external environment, domination of bonding elements of social capital, i.e., based on family, neighbourly, and friendly ties.

Reconciling mutual relations between operating entities in the structural and cultural context blocks changes to the organisational status quo and innovation.

Morphogenetic scenario

The distribution of structural, cultural, and agency forces leads to organisational morphogenesis when conflict arises between the main actors regarding the distribution of structural and cultural resources and/or new collective actors emerge (new differences of interests, new ideas, and values) that challenge the existing structural context and culture of the organisation.

In a state of contextual discontinuity, interpersonal tensions that arise in the past (emotional traumas and conflicts) activate new actors, thus facilitating organisational changes (positive function of conflict) and conditioning the course of innovation processes.

The factor that dynamizes the organisational morphogenesis described above is a type of autonomous reflexivity that spreads in a state of context discontinuity. This manifests itself in an increasingly critical approach to individual aspects of organisational life. It develops at the expense of the previously dominant type of communicative reflexivity.

In the morphogenetic scenario, in conditions of contextual discontinuity, associated with the predominance of autonomous reflexivity; surveyed organisation members (e.g. in the SWOT analysis) emphasise the opportunities to overcome structurally determined barriers to a greater extent than the limitations and threats resulting from them; There are manifestations of bridging social capital among the members of the organisation, i.e., declarations of trust in colleagues, participation in the network of organisational connections, acceptance of the introduction of horizontal structures in management, declarations of openness and willingness to cooperate with the environment.

Participation in the study was based on voluntary and informed consent. Moderators informed respondents in an understandable way about what the study was about, by whom it was conducted, and how its results would be made public and used. Respondents were informed of the right to refuse to participate in the study and the right to withdraw consent at any stage of the study, without giving a reason. Separate and express consent was obtained for the use of sound recording devices. Participants were informed of their rights regarding protection of personal data and copyright protection. Subjects were also provided with the highest possible level of anonymity, comfort, and safety at the research centre.

4. Social Capital and Innovation in a State of Organisational Morphostasis

At the beginning of the second subchapter, references were made to Coleman's three forms of social capital, which are expressed, respectively: 1) trust, or more precisely obligations, expectations and trust conducive to obtaining help from others, 2) norms and effective sanctions associated with them, and 3) connections, that is, access to information and social networks [

57]. The forms of social capital presented that directly refer to the above conceptualisation will be defined as resource creation, in contrast to the forms that are sometimes referred to in the literature as negative, negative, dirty, and non-resource creation [

58,

59].

The proportions existing in a given social context between the level of resource-creating and non-resource-creating capitals (in the dimensions of trust, norms, and connections) and the component of bridging and bonding capital will determine the potential of social and non-resource-creating capital. organisational innovation of a given community, enterprise, or organisation. Therefore, it is important to diagnose the type of social capital that dominates in a given social and organisational context: binding, related to the traditionally understood community, or bridging, which is based on generalised trust and task-orientated and instrumental activities.

The place in the appropriate network of connections and access to the resources of bridging (generalised) social capital, which is associated with a given network of social connections, determine the possibilities of effectively undertaking a specific social or organisational innovation. According to the Global Preferences Survey [

60] conducted on a sample of 80,000 respondents from 76 countries with 90% of the population and the share of these countries' GDP in global GDP, social trust, which is a key component of bridge capital, is statistically significantly correlated with broadly understood economic development.

Cultural morphostasis (normative status quo) is maintained in Polish reality by the established, often taking the normative form of a social fact, domination of patterns of behaviour, and relationships based more on binding (community, family and social, exclusive) than on bridging (social, task-orientated, inclusive) social capital, as well as a normatively grounded orientation towards the group good (not the common good). Its dysfunctional manifestations for the social system are most visible in institutionalised interpersonal relationships, including: among employees, petitioners, clients and stakeholders of offices and institutions, enterprises, and members of nongovernmental organisations. Wherever the presence of elements of social capital is indicated for sustainable socioeconomic development and the building of long-lasting and depersonalised networks of relationships based on generalised trust or a culture of trust [

46]. Its existence in a given context helps eliminate tensions and social distances resulting from strong and exclusive social bonds [

18,

19].

The level of trust between individual and collective actors is crucial, both in theoretical and applied contexts, i.e., when undertaking specific social innovations. Therefore, during group interviews, the respondents were asked the following question. Who should be trusted first when introducing innovations: a) members of the organisation, friends, family, or maybe b) all people equally?

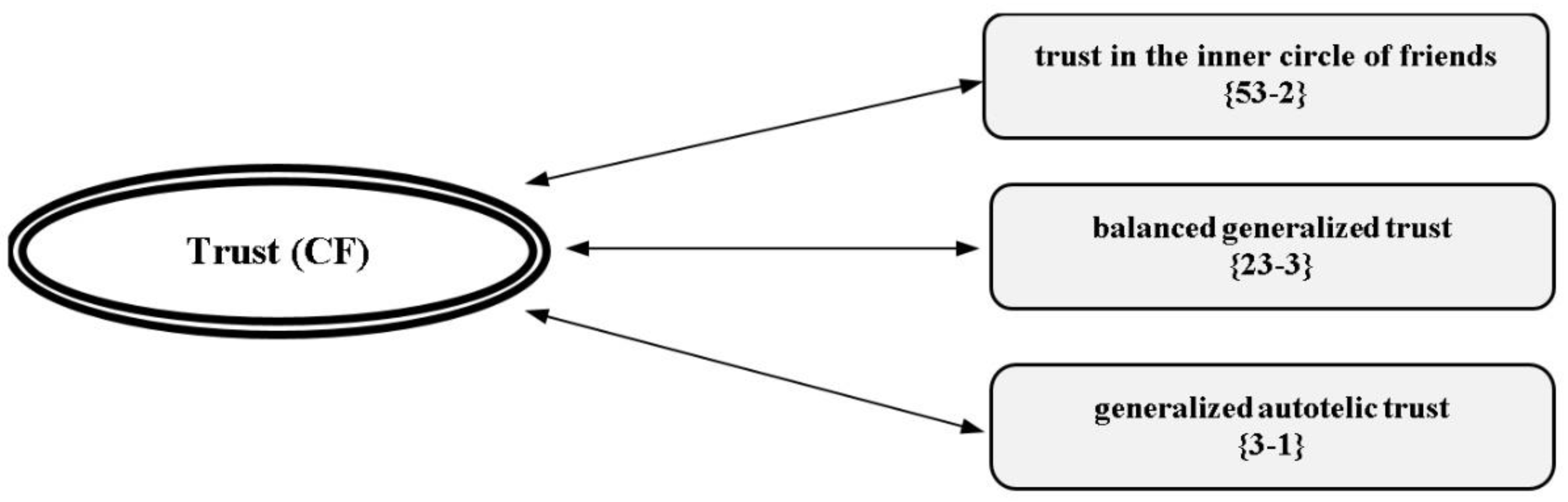

When undertaking innovative activities, approximately two-thirds of the active participants in group interviews declared that they trusted primarily their closest colleagues, friends, and family [code: trust in the inner circle of friends {53-2}]. She based her trust mainly on people in her closest circle of relatives and friends. It built social relations primarily within its primary groups on the binding, not the bridging, component of social capital.

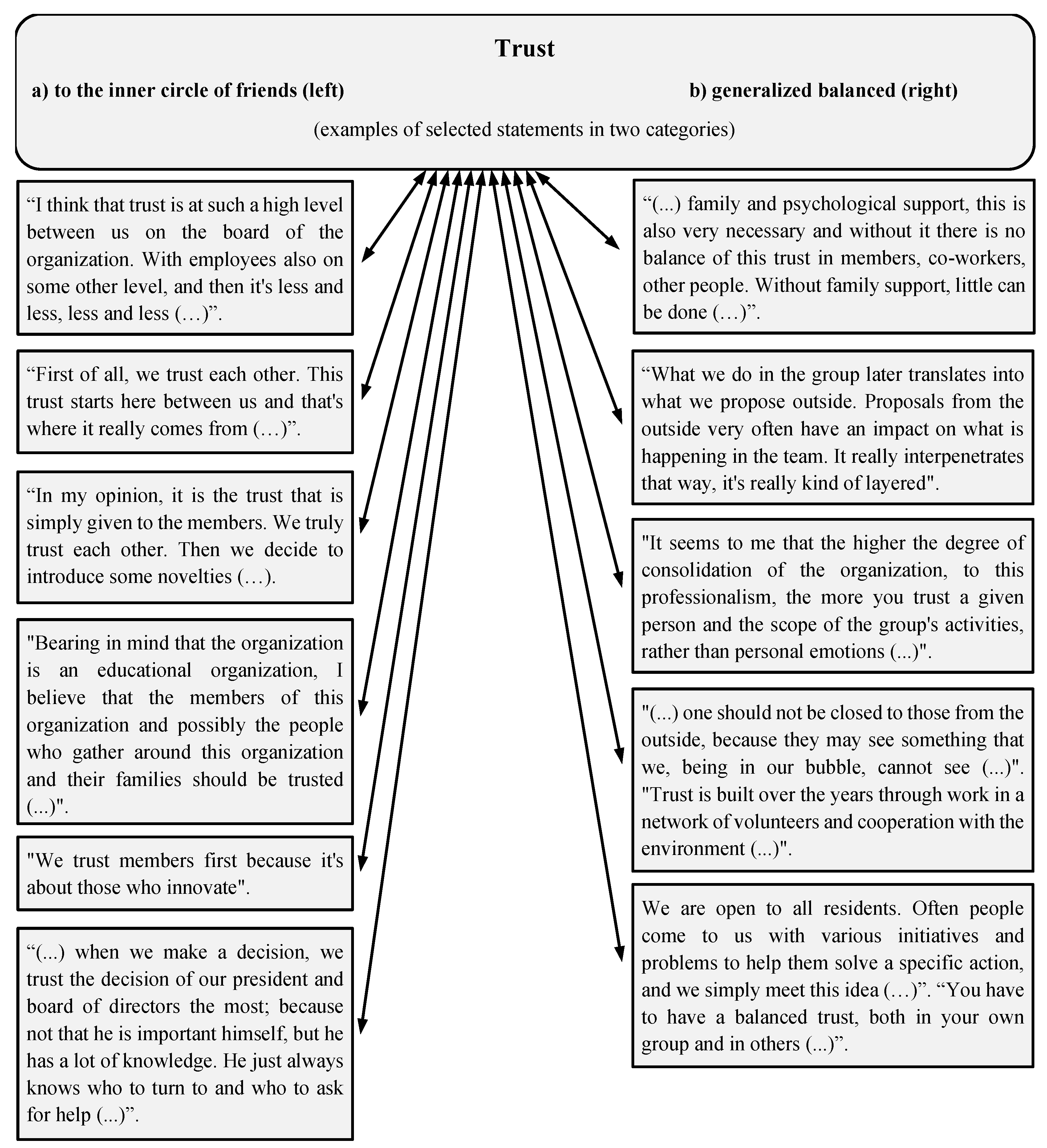

This type of relationship is reflected in a number of statements below. The president of the management board of an organisation supporting the education of children and youth from communities at risk of social exclusion states: "... I think that the trust between us on the management board of the organisation is at such a high level, first of all with the employees, also at some other level, and then less and less". A similar opinion was expressed by a member of the board of an association whose aim is to support young people at risk of diabetes: "First of all, we trust each other, this is the first thing that trust starts here between us, and everything actually comes from there". Another participant in the same focus group states that: “I think it is actually obvious. Well, that is the kind of... trust that is just put in the members. But like, well, we know that then we will decide to introduce some innovations. When it comes to the school principal, we trust that the people who will use it, the people managing the school, we simply trust... Conscientious manner. However, scout activist from a medium-sized city-state: "Taking into account the fact that the organisation is an educational organisation, I believe that we should trust the members of this organisation and possibly people gathered around this organisation and their families, etc.".

Figure 1.

Perceptual map: Types of trust of NGO members surveyed when introducing innovations. Source: own work (The perceptual map (see

Figure 1) contains analyses of transcriptions of focus group interviews obtained using the Atlas.ti programme; concerns the types of trust of the surveyed NGO members when introducing innovations. This tool enabled the generation of codes and their families, presenting the main categories of responses that allowed for a transparent presentation of the research results. For example, one of the codes was called "trust in the inner circle of friends" {53-2} and consists of two elements: the first one is the degree of grounding (53), that is, the number of links between the code and quotations within the text document, and the second one (2) is coherence, that is, the connection of a given code with other codes. This code has been included in the code family (CF): trust).

Figure 1.

Perceptual map: Types of trust of NGO members surveyed when introducing innovations. Source: own work (The perceptual map (see

Figure 1) contains analyses of transcriptions of focus group interviews obtained using the Atlas.ti programme; concerns the types of trust of the surveyed NGO members when introducing innovations. This tool enabled the generation of codes and their families, presenting the main categories of responses that allowed for a transparent presentation of the research results. For example, one of the codes was called "trust in the inner circle of friends" {53-2} and consists of two elements: the first one is the degree of grounding (53), that is, the number of links between the code and quotations within the text document, and the second one (2) is coherence, that is, the connection of a given code with other codes. This code has been included in the code family (CF): trust).

Figure 2.

Code citation map: trust in two categories: a) to the inner circle of friends (left), b) generalised balanced (right). Source: own work.

Figure 2.

Code citation map: trust in two categories: a) to the inner circle of friends (left), b) generalised balanced (right). Source: own work.

However, among the remaining (approximately one third) active focus group participants, manifestations of generalised balanced trust were observed, i.e., to a similar extent towards members of their primary and other generalised groups, as well as several statements representing generalized autotelic trust, uncritical towards "others" [code: balanced generalised trust {23-3}], i.e. to a similar extent towards members of one's primary and other generalised groups, and several statements representing generalized autotelic trust, uncritical towards "others" [code: generalised autotelic trust {3-1}]. This group of respondents declared, unlike the majority mentioned above, full trust in external participants in innovative activities. Such attitudes are an example of the evolution from community bonds typical of bonding capital to a relative balance between the components of bonding and bridging capital. For example, the president of an association whose goal is to activate disabled people from a large Silesian city states: "I believe that no innovation will be introduced if members and volunteers are not trusted, that is, first of all. You can count on them and have faith in them. However, family support, as psychological support, is also very, very necessary for me, and without a balance of trust in members, colleagues, and family support, there is little that can be done at least in my opinion, in my opinion".

In mature and effective organisations, both structurally and functionally, rooted in a broader sociocultural environment, there is a process of limiting emotional bonds in relationships between members in favour of instrumental and task-orientated bonds, depersonalisation of bonds. An eloquent declaration was made by a member of the management board of an association that integrates local communities through historical reconstructions: "It seems to me that the higher the level of foundation of the organisation and its own professionalism, the greater the trust in a given person and the scope of people's activities, greater than personal ones" and “... what we do in the group translates later into what we propose externally". And inquiries from outside...? Proposals from outside often also influence what is happening in the team. The balance of both types of bond and trust among members of nongovernmental organisations is also evidenced by the statement of the president of a student organisation that operates both in its micro-, meso-, and macro-environment: "I assume that it is worth trusting people who are just in it or they were there some time ago... but in order not to go too far in this direction, we should not close ourselves off to those from the outside, because they can see something that we, being inside ourselves, the bubble, do not see". Balanced in this way, social capital, containing both a bonding and a bridging element, has been built over the years through painstaking work on the network of volunteers and cooperation with the broadly understood environment of the organisation.

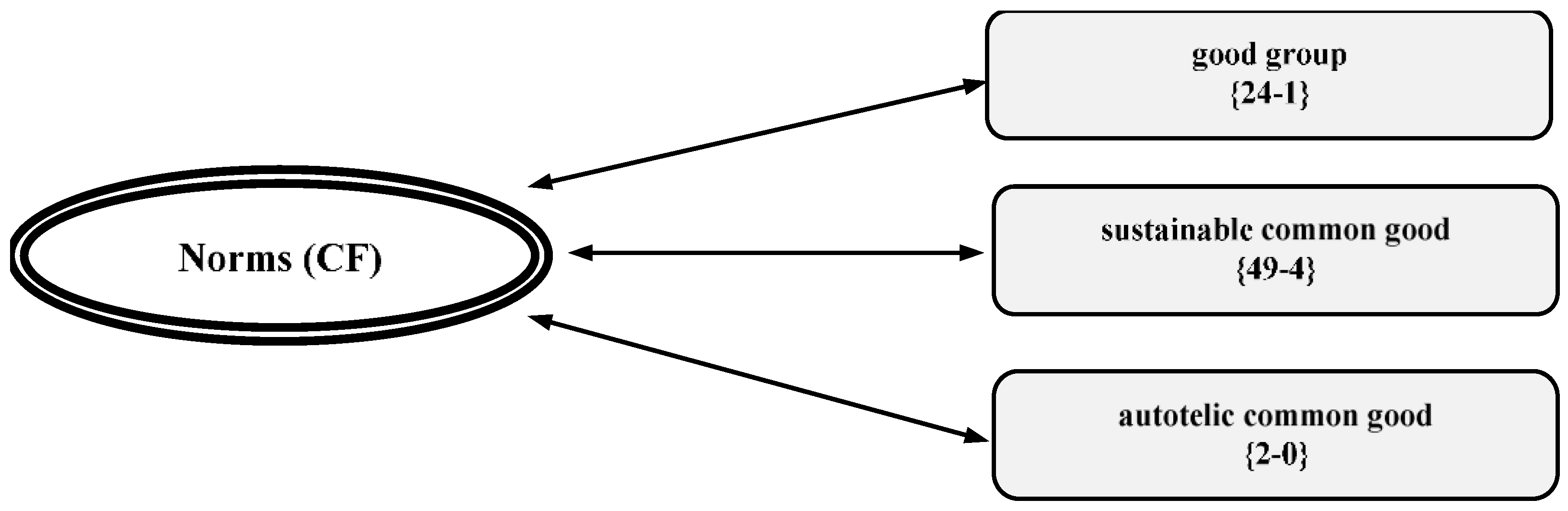

The second classic component of social capital from a functionalist perspective is norms, i.e., a set of common norms and values. The need to participate in the life of the local community, implementation of the principle of reciprocity in social life or the principle of subsidiarity, a sense of identification with the private and ideological homeland, and acceptance based on the internalisation and externalisation of the existing axiology, the normative or legal-political order is resource-creating and is socially established as a norm. Implementing the above normative elements equally determines the social situations in which bridging and bonding capital occurs. However, it seems important to isolate the parameters of the normative component, which will be more strongly assigned to particular types of social capital and pro-innovation attitudes. Hence, in the presented research, it was operationalised as the respondents' attitude towards the opposition: group good versus common good. Hence, the question in the interview scenario is as follows. Does the organisation focus more on activities and matters within its members, or is it more open to the affairs of all residents of the city/municipality/region?

Figure 3.

Perceptual map: Types of norms preferred by respondents as a component of social capital. Source: own work (The perceptual map (see

Figure 3) concerns norms and values as a component of the social capital of the surveyed NGO members. For example, one of the codes is called "common good" {21-1} and consists of two elements: the first is the degree of grounding (24), i.e. the number of links between the code and quotations within the text document, the second (1) is cohesion, i.e. linking a given code with other codes. This code is included in the code family (CF): Norms).

Figure 3.

Perceptual map: Types of norms preferred by respondents as a component of social capital. Source: own work (The perceptual map (see

Figure 3) concerns norms and values as a component of the social capital of the surveyed NGO members. For example, one of the codes is called "common good" {21-1} and consists of two elements: the first is the degree of grounding (24), i.e. the number of links between the code and quotations within the text document, the second (1) is cohesion, i.e. linking a given code with other codes. This code is included in the code family (CF): Norms).

Among the representatives of the surveyed organisations, three types of orientation toward normative opposition were noticed: group good (i.e. primarily the needs of the organisation's members) versus common good (primarily the needs of all inhabitants of the city, region, country, generalised "other"), which concerned making decisions about innovative activities. In addition, two orientations focused on the common good were distinguished. The first, much more common, is a balanced orientation, trying to combine the needs of both the general public and members of nongovernmental organisations, and the second, which treats the common good as an autotelic value, not taking into account the needs of members of one's own group [code: sustainable common good {49-4}], the second treating the common good as an autotelic value, not taking into account the needs of members of one's own group [code: autotelic common good {2-0}].

An example of a sustainable orientation is the following statement: "This organisation is open to all residents. Yes, it is not closed” or “We are open to all residents. People often come to us with various initiatives and problems that are supposed to help them solve a specific action, and we simply come up with this idea” and "The organisation plays a role mainly towards the city's inhabitants, it activates the inhabitants of our city. However, it also takes certain actions for itself and its members...". The following statement by the respondents is an example of autotelic orientation: "... we act for others in practically every possible way, wherever we are... I don't know. Well, we are based in Gliwice and operate throughout Poland and, if we take into account the Internet, throughout the world”.

The orientation towards the good of the group remained in the minority, with less than every third respondent identified [code: group good {24-1}]. The president of the management board of one of the associations surveyed states: "The organisation focused more on activities within its own members and did not reach other residents among other nongovernmental organisations". In a similar vein, the normative orientation of an organisation whose statutory activity is aimed at the civic activation of city residents is assessed by a member of its management board: "In our case, let us say, the first place was always the organisation, the most committed people, and the rest of the members".

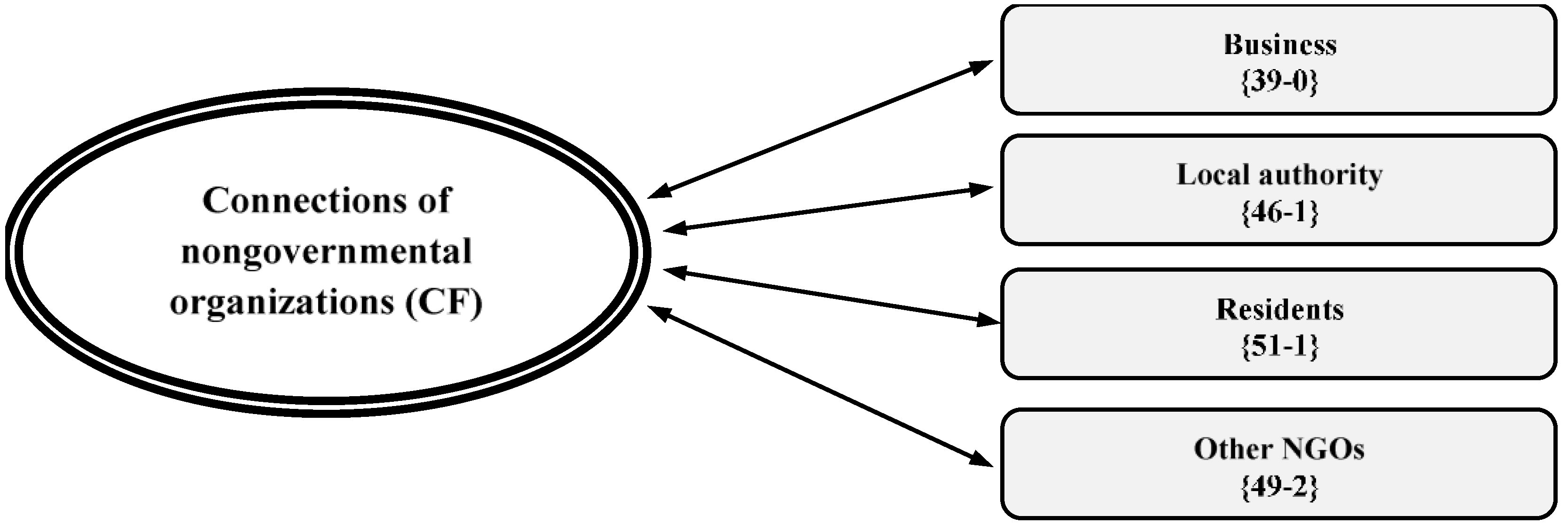

The third form of social capital, understood in Coleman's approach, is connections, which are usually defined as the scope of access to information and the degree of participation in industry, local, regional, national, and international cooperation networks. Belonging or not belonging to a network of third sector institutions (NGO), having or, respectively, lack of cooperation with residents of the local community, local government authorities, and representatives of local or regional business communities, is a manifestation of the functioning of a network of connections that, in the first case, build, and in the second case weaken the resources of social capital (question in the FGI scenario: What is the organisation's cooperation with: a) city/municipal authorities? b) with the inhabitants of the city/municipality? c) with business? d) with other non-governmental organisations?

Figure 4.

Relationships of the non-governmental organisations surveyed with the environment when introducing innovations. Source: own work.

Figure 4.

Relationships of the non-governmental organisations surveyed with the environment when introducing innovations. Source: own work.

Most of the activists surveyed were able to name many different, lasting, mutual forms of connections between their organisation and the broadly understood social environment: city/municipality residents [code: residents {51-1}], local government authorities [code: local government {46-1}], other nongovernmental organisations [code: other nongovernmental organisations {49-2}], and with business representatives [code: business {39-0}].

A member of the management board of an organisation dealing with historical reconstructions talks about connections with other nongovernmental organisations, with herself: "First of all, joint action, because when they lack people, we help them and vice versa, when, for example, we lack people for a certain performance or event, so we can also reach out to other teams and they will support us... I think it is an exchange, a two-way exchange, barter, favour for favour, and all that, that is cool too. It is valuable because we are on the same horse and we want everything to happen and people to benefit, so we help each other. The effectiveness of the actions taken increases with the development of bridging connections, embedded in a coherent system of norms and values. This aspect of the activities of nongovernmental organisations was pointed out by the president of an association focused on educating children and adolescents suffering from cancer: "At the beginning, we focused on our people, i.e., students, graduates, parents, and then we started to expand, including other people in need. Collections; twice a year, even on Christmas, some activities, e.g., collecting magnets for Sandra. Collections in Ukraine. Then there was a Department of Paediatric Oncology in Gliwice, so this activity is expanding to other cities and internationally".

The key function of nongovernmental organisations as institutions that permanently support and complement the activities of local government authorities, as well as connections and networks of mutual connections, was mentioned by a member of the management board of an organisation that undertakes charitable and inclusive activities among homeless people in one place. Larger cities of Upper Silesia: "I always say it - every nongovernmental organisation makes sure that the city engages in certain activities. They should be and are desirable because it is done with the power of people, because the city would have to perform specific tasks for which it would have to pay.

It is assumed that the high potential of social capital, especially bridging and resource-generating capital, contributes to social innovation. However, the presented results indicate the existence of deficits in bridging social capital in most of the organisations studied, in particular the lack of generalised and lasting trust. Non-resource-creating forms of social capital, especially in the dimension of trust and to a lesser extent in the dimension of norms and values, where most respondents declared an orientation towards the lasting common good and lasting social bonds and networks, constitute a significant barrier to social activities, including innovative ones. They reinforce tensions between primary actors (deprived of agency) and collective actors (socially responsible), perpetuating distance and tensions in the group and in relation to the environment.

Historically, conditioned low level of bridging social capital and generalised trust in social or organisational interaction partners constitutes a social fact in Durkheim's understanding. This is one of the key sociocultural factors that negatively determine the development of innovation in civil society, perpetuating social distance and social morphostasis [

62,

63]. As numerous studies, including ours, show, this also makes it difficult to build institutionalised networks of cooperation not only between civil society participants but also relationships with scientific and research institutions, local governments, and state administrations.

5. Types of Reflexivity and Innovation in a State of Organisational Morphostasis

What is the dominant type of reflexivity and the related nature of agency that determines the dominance of the morphostatic or morphogenetic mode of action among the members of the surveyed nongovernmental organisations? Remaining in the spirit of the assumptions of Archer's theory of structure and agency, it was assumed that the determinant of the existence of communicative (morphostatic) reflexivity is the respondents' emphasising the importance of barriers, both conscious and structural, and not the possibilities and possibilities of overcoming them by the members of the organisation; lack of trust in the external environment, domination of binding elements of social capital, i.e. based on family, neighbourly, and friendly ties, uncritical submission to management decisions, and the applicable system of organisational norms and values (axionormatic morphostasis). Indicators of autonomous (morphogenetic) reflexivity contrast with those mentioned above. The dominance of a given type of reflexivity among group members is conditioned by the perception of existing barriers to agency. In the cases examined, conscious and intra-organizational barriers to agency dominated over structural (objectified) barriers and those resulting from relations with the external environment.

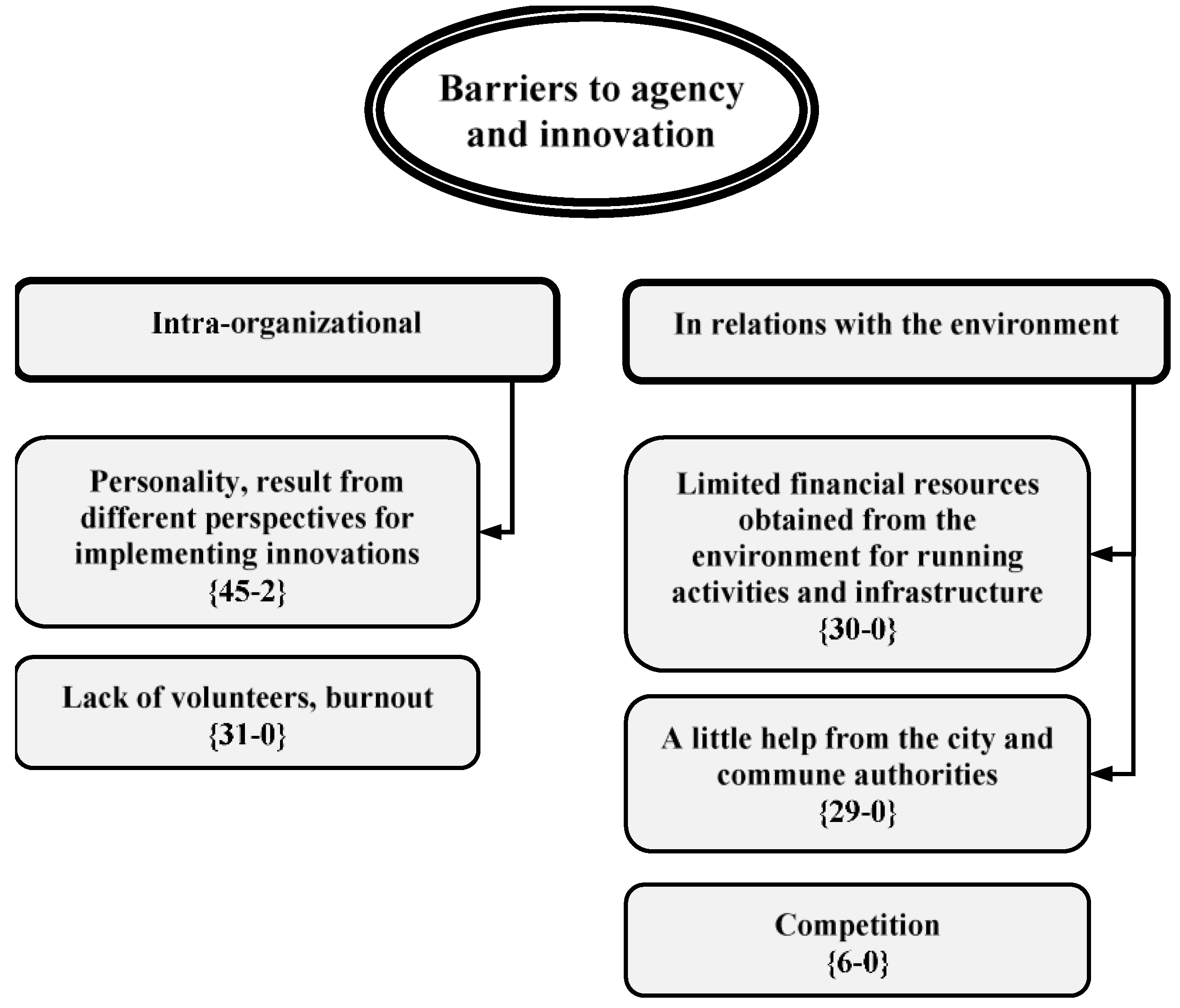

Figure 5.

Perceptual map of the code family: Barriers to agency and innovation in the studied nongovernmental organisations. Source: own work.

Figure 5.

Perceptual map of the code family: Barriers to agency and innovation in the studied nongovernmental organisations. Source: own work.

The attitude of the respondents towards maintaining contextual continuity was observed, which is reinforced by the dominance of communicative reflexivity over autonomous reflexivity [

8,

9,

12,

13,

15]. The respondents highlighted the importance of difficulties in overcoming both structural barriers [code: limited financial resources obtained from the environment to carry out activities and infrastructure {30-0}], [code: little help from the city and municipal authorities {29-0}], as well as awareness barriers of their causality. It was particularly important to pay attention to negative group emotions that block innovations, mainly group and individual jealousy [code: envy of innovators {27-1}] and personal conflicts resulting from different views on the implementation of innovations [code: personality conflicts {45-2}]. Focus group participants were also asked about the causes of conflicts and tensions in their organisations (

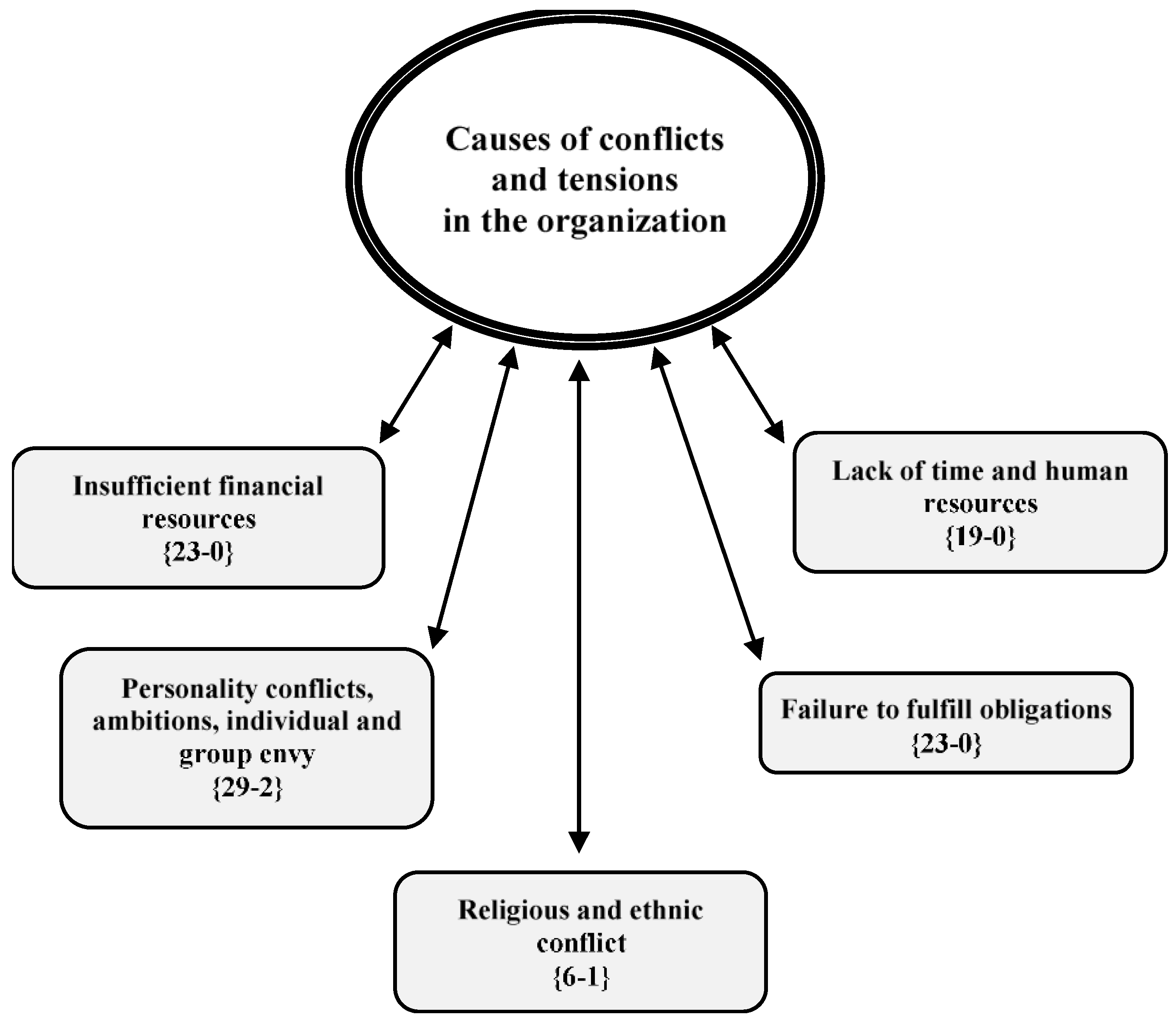

Figure 6). Understanding the areas of personal and group development tensions allows you to diagnose barriers to the agency of entities operating in the organisation. Also, in this area, respondents emphasised the predominance of conscious barriers limiting their organisational agency over structural (objectified) barriers. Among the awareness barriers, personal conflicts turned out to be particularly important due to differences in the ways of defining strategic goals and methods of achieving them, but also the accompanying excessive personal ambitions and jealousy [code: personality conflicts, ambitions, individual and group jealousy {29-2}] and difficulties resulting from selective, unreliable involvement of members [code: default {23-0}].

Figure 6.

Perceptual map of the code family: causes of conflicts and tensions in the organisation. Source: own work.

Figure 6.

Perceptual map of the code family: causes of conflicts and tensions in the organisation. Source: own work.

The areas of generating negative emotions, mainly individual and group jealousy, included the sphere of organisational power [code: hierarchical structure of the organisation {25-0}] and [code: dominant role of the leader {18-0}] and the unrealized need for social prestige [code: none own ideas and simultaneous lack of acceptance of ideas of others {16-0}] and [code: too high ambitions of members {19-1}]. In other words, the generation of negative group emotions (e.g. resentment and jealousy) occurs in two of Weber's three dimensions of social differentiation, i.e., power and prestige (status). However, no tensions were noted in access to economic goods, which may indicate the dominant axionormative community among respondents, members of organisations focused on Pro Publico Bono activities. The agreement on basic values is an element of organisational morphostasis. The above categories of statements are a manifestation of the implementation of the morphostatic type of innovation community by most of the respondents. Perception maps indicate the existence of serious deficits in agency, mainly in the conscious dimension of the entities examined. Therefore, it seems reasonable to say that most of them undertake innovative activities in a conservative and conformist way toward the existing structural and cultural context. It supports their communication reflectivity, maintaining the organisational status quo.

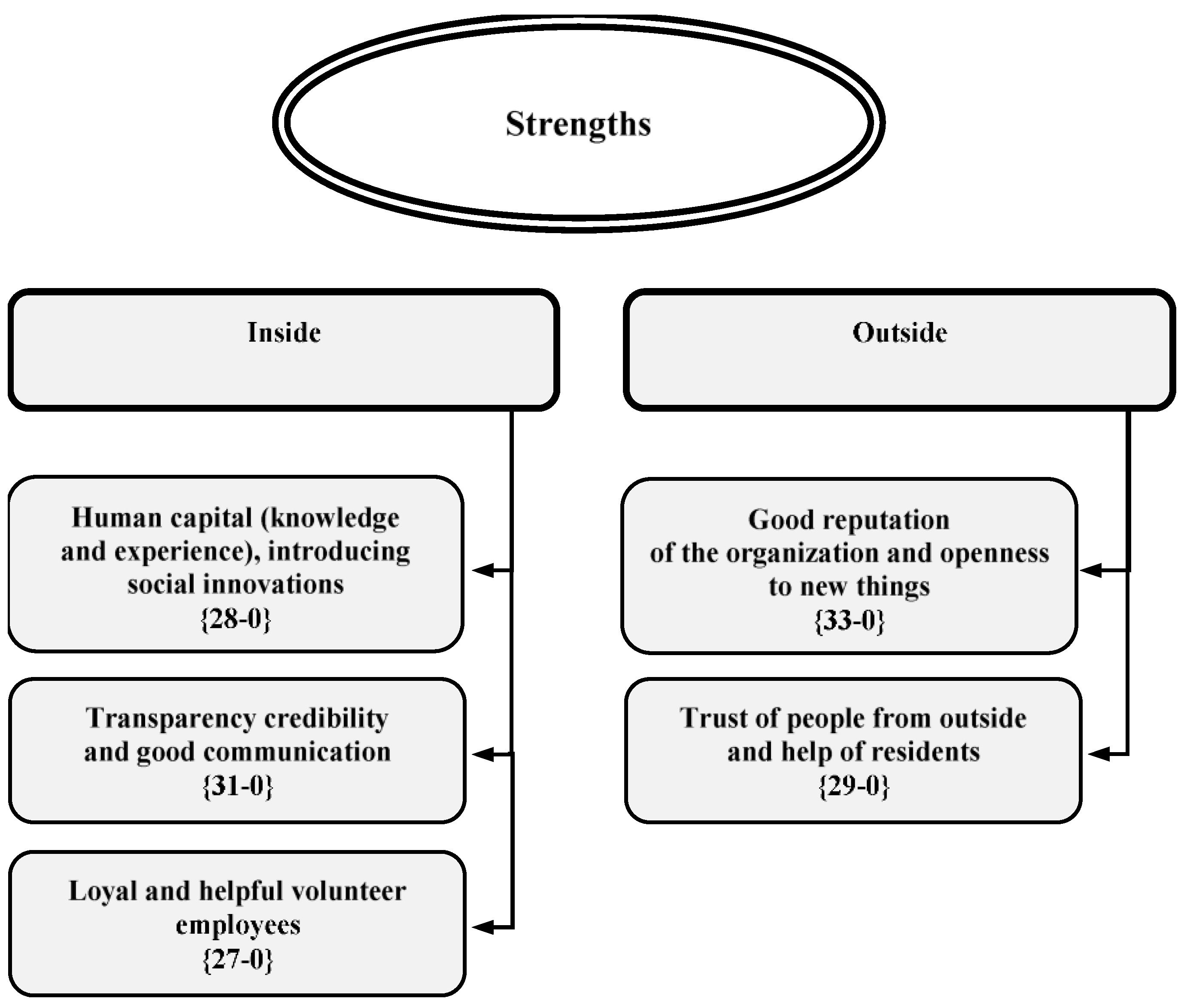

Figure 7.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, strengths of the surveyed NGOs. Source: own work.

Figure 7.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, strengths of the surveyed NGOs. Source: own work.

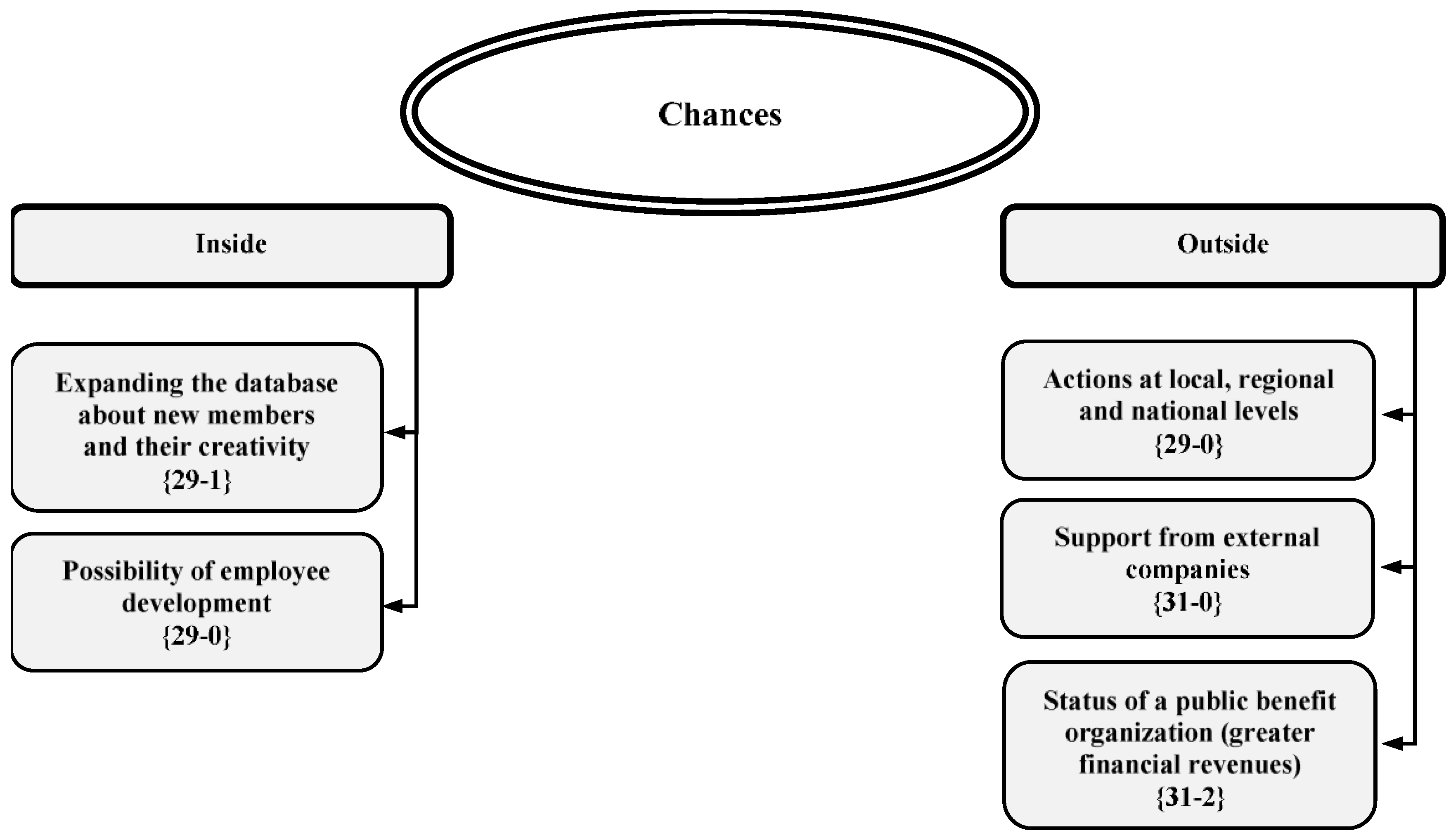

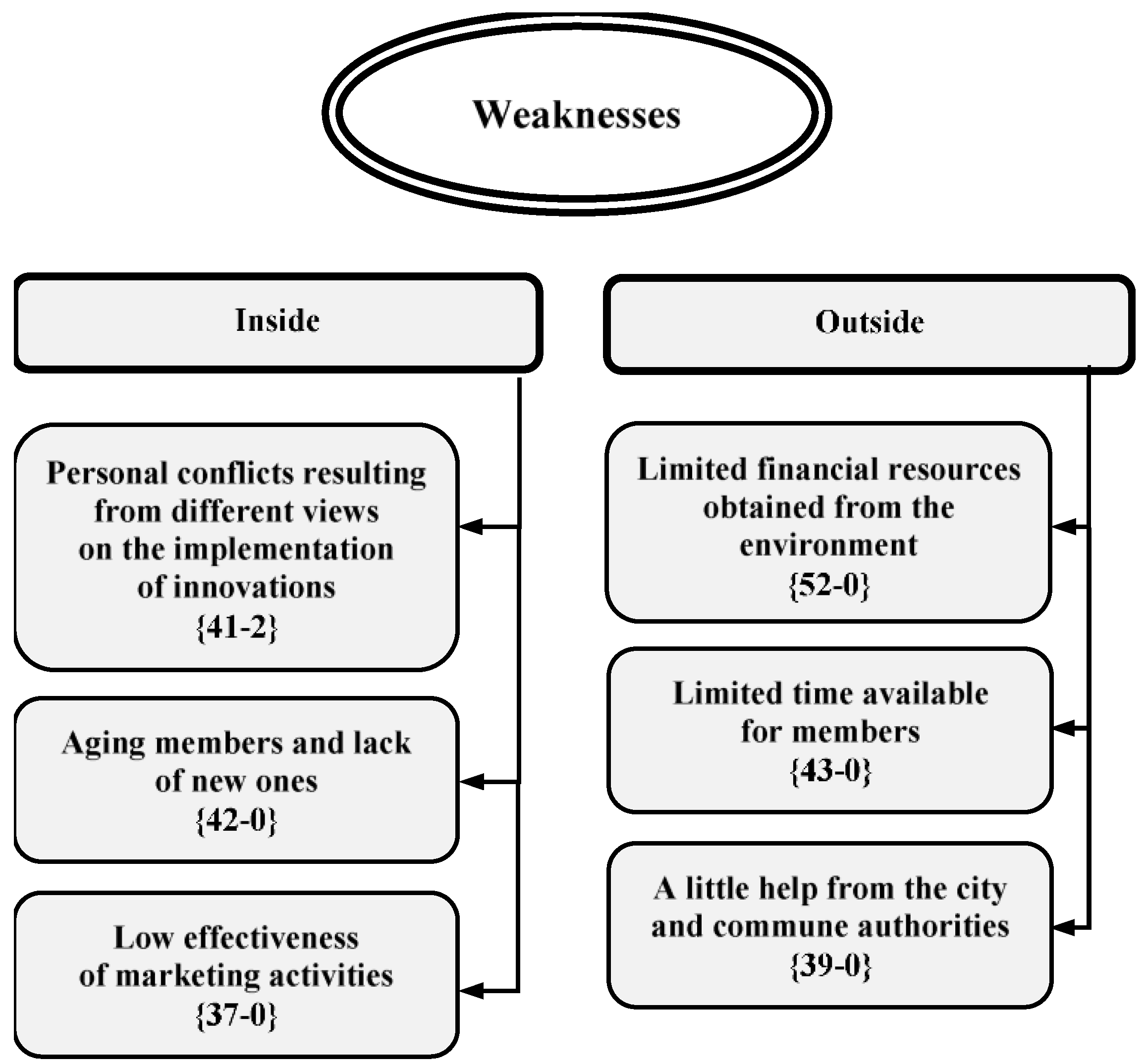

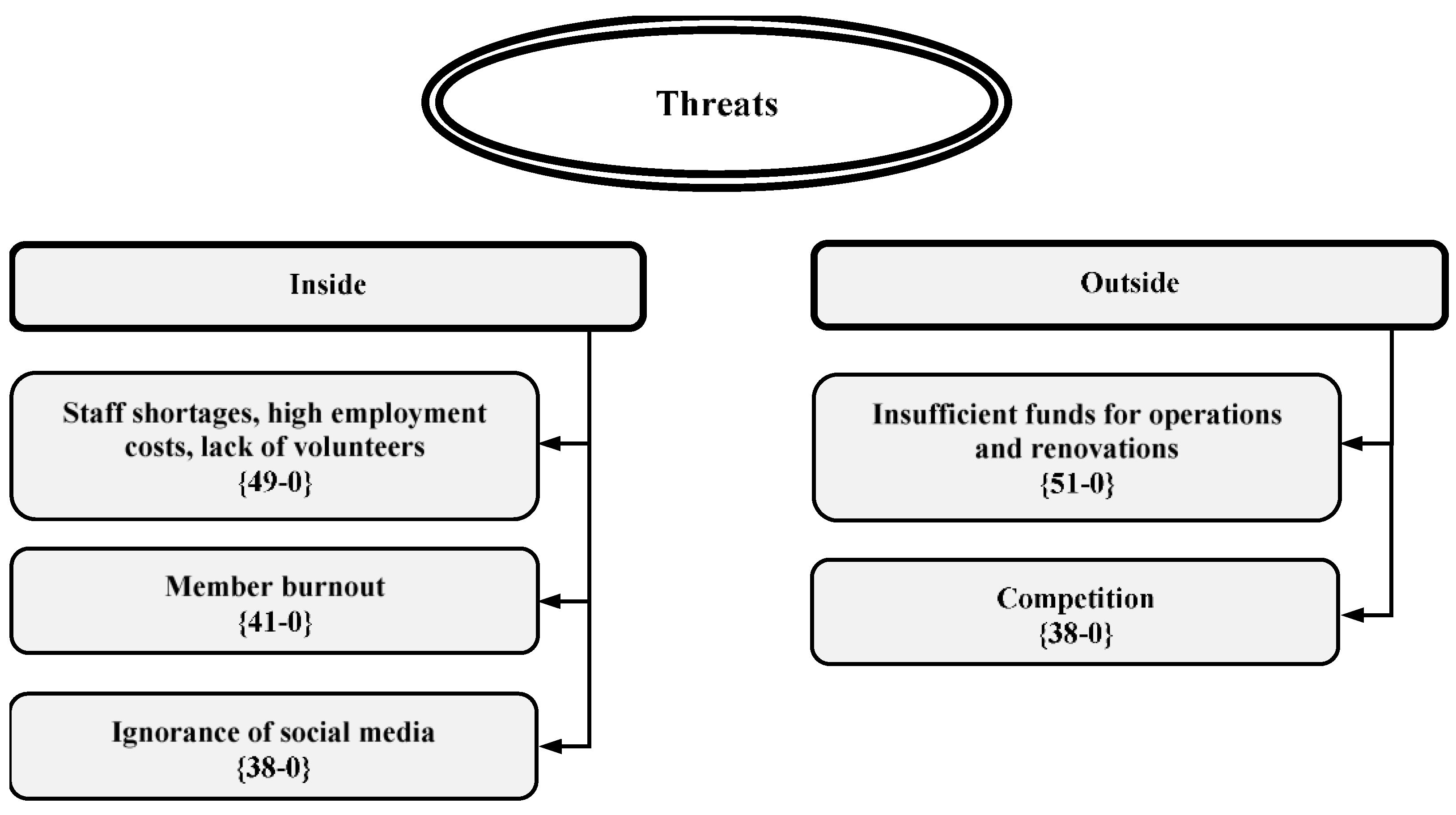

The above observations are also confirmed by the analysis of SWOT questionnaires, which were an integral part of the documentation prepared by the respondents as part of the project. Among the SWOT questionnaires analysed, most of the respondents emphasised the weaknesses of their organisation and existing and potential development threats that limit their ability to act (see

Figure 8 and

Figure 9) more often than the strengths of the organisation and the internal and external opportunities they perceived (see

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). The presented perception maps clearly show that the predominance of the indicated passive voices is manifested in both the scope and frequency of the indicated categories (codes).

Figure 8.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, opportunities of the surveyed SMEs. Source: own work.

Figure 8.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, opportunities of the surveyed SMEs. Source: own work.

Figure 9.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, weaknesses of the surveyed NGO’s. Source: own work.

Figure 9.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, weaknesses of the surveyed NGO’s. Source: own work.

Figure 10.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, dangers of the surveyed NGO’s. Source: own work.

Figure 10.

Perceptual map of the code family: part of the SWOT analysis, dangers of the surveyed NGO’s. Source: own work.

The presented results of qualitative research prove the acceptance of the existing organisational status quo among members of most of the organisations surveyed. They demonstrate a desire to maintain the continuity of structural and cultural contexts in the examined nongovernmental organisations. The resources of a structural agency possessed by the respondents, i.e. relatively positive relations with local government authorities, knowledge of law, the ability to obtain funds from EU funds and local business, or in short know-how, constitute a smaller obstacle to undertaking innovations. The problem, however, is the deficits in conscious agency that inhibit the above-mentioned processes. Undertaking innovative activities among representatives of most of the surveyed nongovernmental organisations is limited by the predominance of elements of communicative reflexivity over autonomous reflexivity. Below, we summarise the results of research on the indicators of two opposing types of reflexivity, which constitute two types of agency that determine the morphostatic or morphogenetic mode of organisational activities. The communicative type of reflexivity (morphostatic) that dominates among the respondents (about two-thirds of non-governmental organisations) is manifested by a more frequent pointing to barriers and threats resulting from structural conditions within the organisation and its environment, rather than to the opportunities and opportunities related to them; acceptance of the organisation's status quo, limited trust in the external environment, fear of change. The above type of agency is also associated with the predominance of elements of binding social capital, i.e., based on exclusive family and social ties; selective connections with the socioeconomic and local government environment. Representatives of the communicative type of reflexivity more often prefer a vertical management style, are characterised by reluctance to delegate responsibility, limited trust in external collaborators, lack of permanent communication channels, direct consultations with rank-and-file employees, among others. in matters of innovation, which results in limited opportunities to articulate the interests and values of rank-and-file employees who are members of the organisation. However, the autonomous (morphogenetic) type of reflexivity, the manifestations of which were observed in representatives of approximately one third of the surveyed nongovernmental organisations, is characterised by noticing chances and opportunities, not barriers and threats, more often inside than outside the organisation. Organisational members representing autonomous reflexivity may observe a growing critical attitude towards particular aspects of organisational life, declarations of commitment to changes in the organisation, and perceiving change as an opportunity. Among them, the most dominant manifestations are bridging social capital, i.e. generalised, balanced trust, trust in entities and institutions in the external environment, declarations of support for the idea of the common good, strong, and extensive connections with the environment. Moreover, they are characterised by the acceptance of a democratic, horizontal management style, the use of delegation of responsibility, the existence of permanent communication channels, and direct consultations with rank-and-file employees, including: in matters of innovation, articulating the interests and values of employees. The autonomous type of reflexivity and agency develops in opposition to the previously dominant communicative type

6. Results and Conclusions

The article sought answers to two complementary research questions. First, what elements of binding and bridging social capital (in the area of trust, norms, and connections) determine innovative activity in the state of morphostasis (contextual continuity) of selected non-governmental organisations? Second, what type of reflexivity and the related nature of agency dominates when undertaking innovative activities among entities operating in the studied nongovernmental organisations? Answering the first question, it should be stated that if there is a greater level of trust among the members of a given group or organisation in the circle of family, neighbours, and friends than in others, focussing on achieving the group's goals to a greater extent on the good than on the common good and developing a network of connections social, more personal, and emotional than depersonalised and instrumental, the potential of bonding capital outweighs the potential of bridging capital. These social relations, which were aimed at maintaining the existing social and organisational status quo (morphostasis), occurred in approximately two-thirds of the nongovernmental organisations surveyed. However, if in the examined group or organisation trust prevails in generalised "others" - those outside the circle of family, neighbours and friends; that is, to partners in the socioeconomic environment; normative dimension, focussing on the implementation of the common good, sustainable to a greater extent than the group good, and there is an extensive and balanced network of connections with the environment of a task-instrumental nature, it can be concluded that the resource which determines the nature of existing social relations (including pro-innovation ones) more bridging capital than bonding capital. In the above morphogenetic way, social relations occurring among approximately one third of the examined nongovernmental organisations were diagnosed.

Answering the second research question requires a more multidimensional approach. Based on the adopted theoretical assumptions and the results of the presented focus group studies and previous own research [

3,

62], it was found that organisational morphostasis occurs with the cooccurrence of the following endogenous conditions, limiting the innovative activity of members of the studied nongovernmental organisations: (1) there is a predominance of elements of bonding social capital over bridging ones, (2) agency members are based to a greater extent on communicative rather than autonomous reflexivity, (3) lack of new collective entities of action in nongovernmental organisations questioning the existing status quo, i.e. the existence of contextual continuity (structural and/or cultural), (4) community inscribed in the above structural and cultural state petrifies social and organisational morphostasis (structural and cultural continuity of nongovernmental organisations), (5) also, the predominance of the components of bonding social capital maintains the existing contextual continuity and the level of social tensions and distances, and also limits innovation.

Organisational morphogenesis occurs with the co-occurrence of the following endogenous conditions stimulating the activities of the examined nongovernmental organisations: (1) the domination of the components of bridging social capital over the binding social capital, (2) the organisational agency of the organisation's members is based to a greater extent on autonomous rather than communicative reflexivity, (3) shaping the emergence of new collective actors, and more precisely, new interests (structural conditions) and group values (cultural conditions), i.e./or cultural discontinuity; (4) group tensions and traumas inherent in the above structural and cultural contexts dynamize the process of organisational morphogenesis; the predominance of bridging components of social capital facilitates overcoming the existing status quo in the organisation, introducing innovations, and in the case of contextual discontinuity (structural and/or cultural changes) it facilitates overcoming awareness barriers caused by envy and resentment.

The results presented prove the existence of relatively large potentials of bonding social capital and deficits of bridging capital in the organisations studied. The potential of the trust component turned out to be particularly important, as two thirds of respondents emphasised the importance of trust in the inner circle of friends (members of the management board of their own organisation, friends and family), while the potential for generalised trust was low. The results presented reflect broader social processes. Historically conditioned by the loss of its own statehood (1795-1918), consolidated during the period of communist rule (1945-1989), the low level of bridge social capital and generalised trust in social or organisational interaction partners is a social fact in Poland in the Durkheim sense [

63]. It normatively regulates social and organisational relations through a universally observed directive: cooperate with those you know, trust your own people, and do not trust strangers. The mentioned social fact also permanently determines today's Polish economic, social, and political reality. This is one of the key sociocultural factors negatively determining development, including social innovation in civil society and perpetuates existing social distances. As numerous studies, including ours, show [

62], this also makes it difficult to build institutionalised networks of cooperation not only between members of nongovernmental organisations, but also relationships with scientific and research institutions, local government, and state administration.

7. Discussion and Future Research

In the end of the article, there is space for minor conceptual and methodological comments and a presentation of future research plans. The aim of the article was to diagnose two endogenous determinants of innovation in organisational states and change in selected Polish (Silesian) non-governmental organisations. An attempt was made to determine what internal factors determine the processes of innovation and social and organisational changes (morphogenesis), i.e., the dominant forms of social capital (in terms of trust, norms, values and networks of connections), as well as the types of reflexivity and the types of agency related to it. Taking into account elements of trust capital, bonds, and social norms that are dysfunctional for a given community allowed us to avoid accusations of a one-dimensional image of reality levelled against representatives of purely integration concepts, including: Putnam or Coleman. Therefore, a distinction was made between opposing forms of social capital: those that create resources and those that do not create resources. Example: a nonresource-generating form of social capital (in terms of norms) manifests itself in patterns of social nonparticipation and disbelief in agency, both at the local and national levels.

In future research, in order to determine the endogenous conditions of agency and innovation of members of non-governmental organisations, it will be advisable, in addition to diagnosing the potential of social capital, to determine the scope of occurrence of two opposing types of reflexivity: communicative and autonomous, and to determine what structural and cultural conditions favour the emergence of resentmental tensions in a given organisation and how existing group resentmental tensions determine the agency of collective entities, including innovative activities, in a state of morphostasis (contextual continuity) and morphogenesis (contextual discontinuity), respectively. Moreover, it will be cognitively important to determine what deficits in access to important places in the network of connections and the lack of resources (trust and being embedded in a common system of norms and values favouring group action) cause a sense of alienation, powerlessness and exclusion among potential innovators [

31,

65,

68]; Does a given organisational context create resentmental potentials in the sense of Max Scheler [

64], when grassroots, innovative social and organisational activities, which have declared acceptance by representatives of organisational authorities, collide with barriers resulting from the deficit of the network of social connections, generalised trust, and the existence of individual and group jealousy? The next challenge remains to conduct the above research, this time quantitative, on a representative random sample for the entire set of Polish nongovernmental organisations and, in the longer term, to undertake international comparative research [

67].

Appendix A

FGI Scenario "Social Innovation". The main questions that make up the focus group interviews (FGIs):

References

- Murray, R.; Caulier-Grice, J.; Mulgan, G. Open Book of Social Innovation; Young Foundation: London, UK, 2010; pp. 22–23.

- Mulgan, G.; Tucker, S.; Ali, R.; Sanders B. Social Innovation: What It Is, Why It Matters, How It Can Be Accelerated; The Young Foundation: Oxford, UK, 2007; pp. 22–23.

- Weryński, P.; Dolińska-Weryńska, D. Agency barriers of members of senior Silesian NGOs in the implementation of social innovation (Poland). Sustainability 2021, 13, p. 734. [CrossRef]

- Cooter, R.D.; Schaefer, H.B. How Law Can End the Poverty of Nations. Conference, Searle Centre, Northwestern Law School, 11-12.12.2008.

- Bendyk, E. Kulturowe i społeczne uwarunkowania innowacyjności. In Innowacyjność 2010, Raport; PARP: Warszawa: PARP, 2010.

- Goldmann, M. Multilevel Education Assessments by Private and Public Institutions, Holding Governments Accountable through Information. Available online: https://www.mpil.de/en/pub/news.cfm (accessed on 19 September 2023).

- Lubimow-Burzyska, I. Proces tworzenia innowacji społecznych. In Innowacje społeczne w teorii i praktyce, Wyrwa, J, Ed.; PWE: Warszawa, 2014; pp. 83–88.

- Archer, M. Structure, Agency and the Internal Conversation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2003; pp. 342–361.

- Archer, M. Człowieczeństwo. Problem Sprawstwa; Zakład Wydawniczy NOMOS: Cracow, 2013; pp. 22–25, 311–316.

- Archer, M., Ed. Morphogenesis and the Crisis of Normativity. In Introduction, Does Social Morphogenesis Threaten the Rule of Law?; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016.

- Archer, M. Morfogeneza: Ramy wyjaśniające realizmu. Uniwersyteckie Czasopismo Socjologiczne UKSW 2015, 10, pp. 16–46.

- Archer, M. Can Reflexivity and Habitus Work in Tandem? In: Conversations About Reflexivity; Archer, M.; Routledge: London/New York, 2010; pp. 123–143.

- Archer, M. Conversations About Reflexivity; Routledge: London/New York, 2010.

- Archer, M. The Reflexive Imperative in Late Modernity; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 2012.

- Archer, M. Structural Conditioning and Personal Reflexivity. In Distant Markets, Distant Harms: Economic Complicity and Christian Ethics, Finn, D.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2014.

- Archer, M. Structure, Culture, and Agency. In The Blackwell Companion to the Sociology of Culture; Jacobs, M., Hanrahan, N.; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, 2005.

- Archer, M. How Agency is Transformed in the course of Social Transformation: Don't forget the double morphogenesis. In Generative Mechanisms Transforming the Social Order; Archer M.; Springer: New York, 2015.

- Theiss, M. Krewni – znajomi – obywatele. Kapitał społeczny a lokalna polityka społeczna. Adam Marszałek: Toruń, 2007.

- Štremfelj, L.R.; Žnidaršič, J.; Marič, M. Government-Funded Sustainable Development and Professionalisation of NGOs. Sustainability 2020, 12(18), p. 7363. [CrossRef]

- Czapiński, J.; Panek, T., Eds.; Diagnoza społeczna i jakość życia Polaków. Available online: http://www.diagnoza.com/pliki/raporty/Diagnoza_raport_2015.pdf.

- Analizy Statystyczne GUS, Jakość życia i kapitał społeczny w Polsce. Wyniki badania spójności społecznej 2018. GUS, 2020; pp. 141-156. Available online: https:/www.stat.gov.pl.

- Feliksiak, M. Aktywność w organizacjach obywatelskich. CBOS, Komunikat z badań, 2022; p. 41.

- Czapiński, J. Kapitał ludzki i kapitał społeczny a dobrobyt materialny. Polski paradoks. Zarządzanie Publicznie 2008, 2(4), pp. 5–28.

- European Social Survey [dataset], 2022. Available online: www. europeansocialsurvey.org.

- Coleman, J.S. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. The American Journal of Sociology 1988, 94, Supplement, Organizations and Institutions: Sociological and Economic Approaches to the Analysis of Social Structure. The University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

- Bartkowski, J. Kapitał społeczny i jego oddziaływanie na rozwój w ujęciu socjologicznym. In Kapitał ludzki i kapitał społeczny a rozwój regionalny; Herbst, M., Ed.; Scholar: Warszawa, 2007.

- Herbst, M. Kapitał ludzki, dochód i wzrost gospodarczy w badaniach i empirycznych. In Kapitał ludzki i kapitał społeczny a rozwój regionalny; Herbst, M., Ed.; Scholar: Warszawa, 2007.

- Batorski, D. Polacy wobec technologii cyfrowych - uwarunkowania dostępności i sposobów korzystania (PL). Contemporary Economics 2013, 7(3.1). University of Economics and Human Sciences: Warsaw.

- Giza-Poleszczuk, A.; Włoch, R. Innowacje a społeczeństwo. In Świt innowacyjnego społeczeństwa. Trendy na najbliższe lata; Zadura-Lichota, E., Ed.; PARP: Warszawa, 2013.

- Adler, P.; Kwon, S.-W. Social capital; the good, the bad ugly. In Knowledge and social Capital, Foundation and Application; Lesser, E., Ed.; Butterworth-Heineman: Boston, 2000; p. 93.