Submitted:

24 May 2024

Posted:

27 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

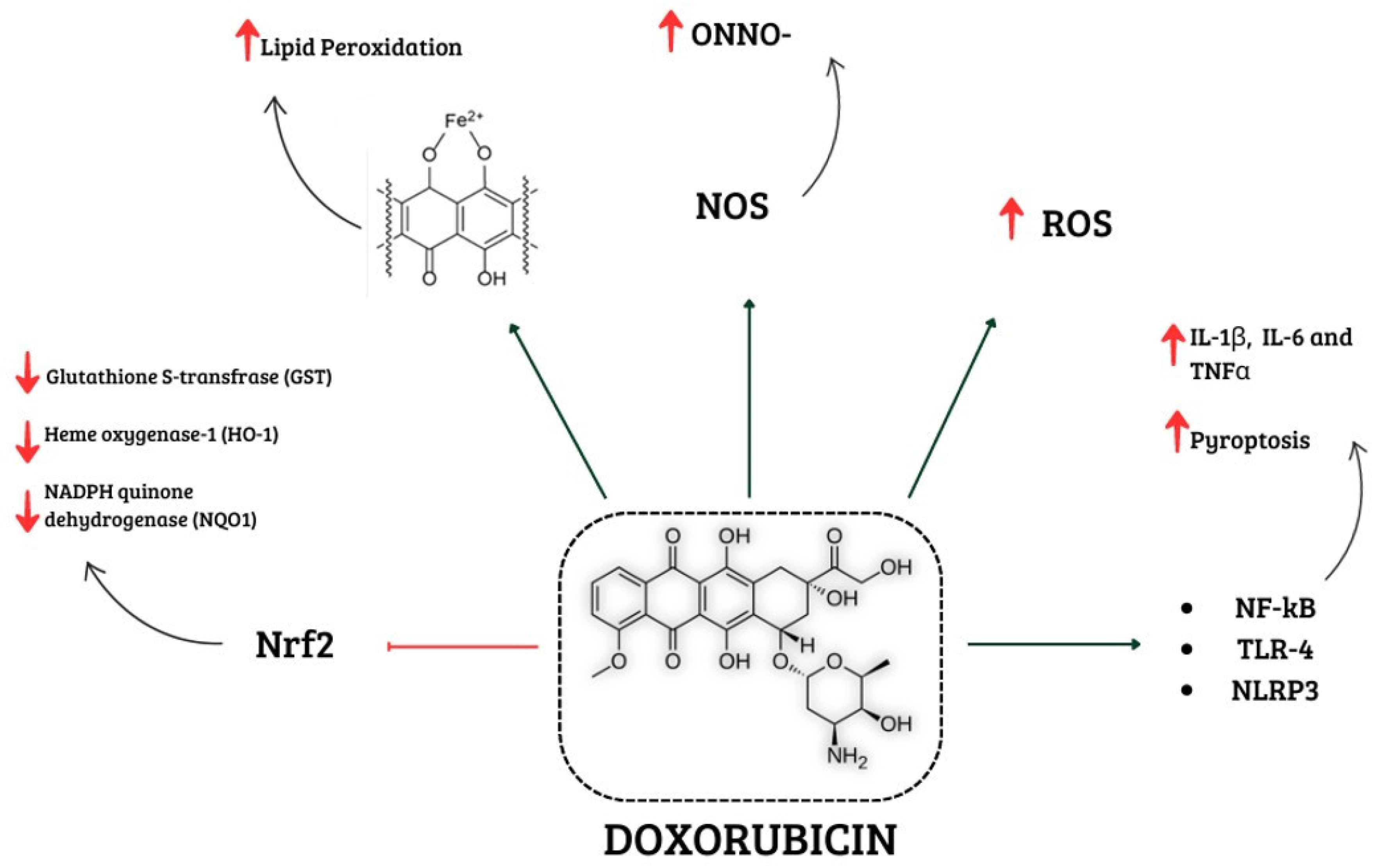

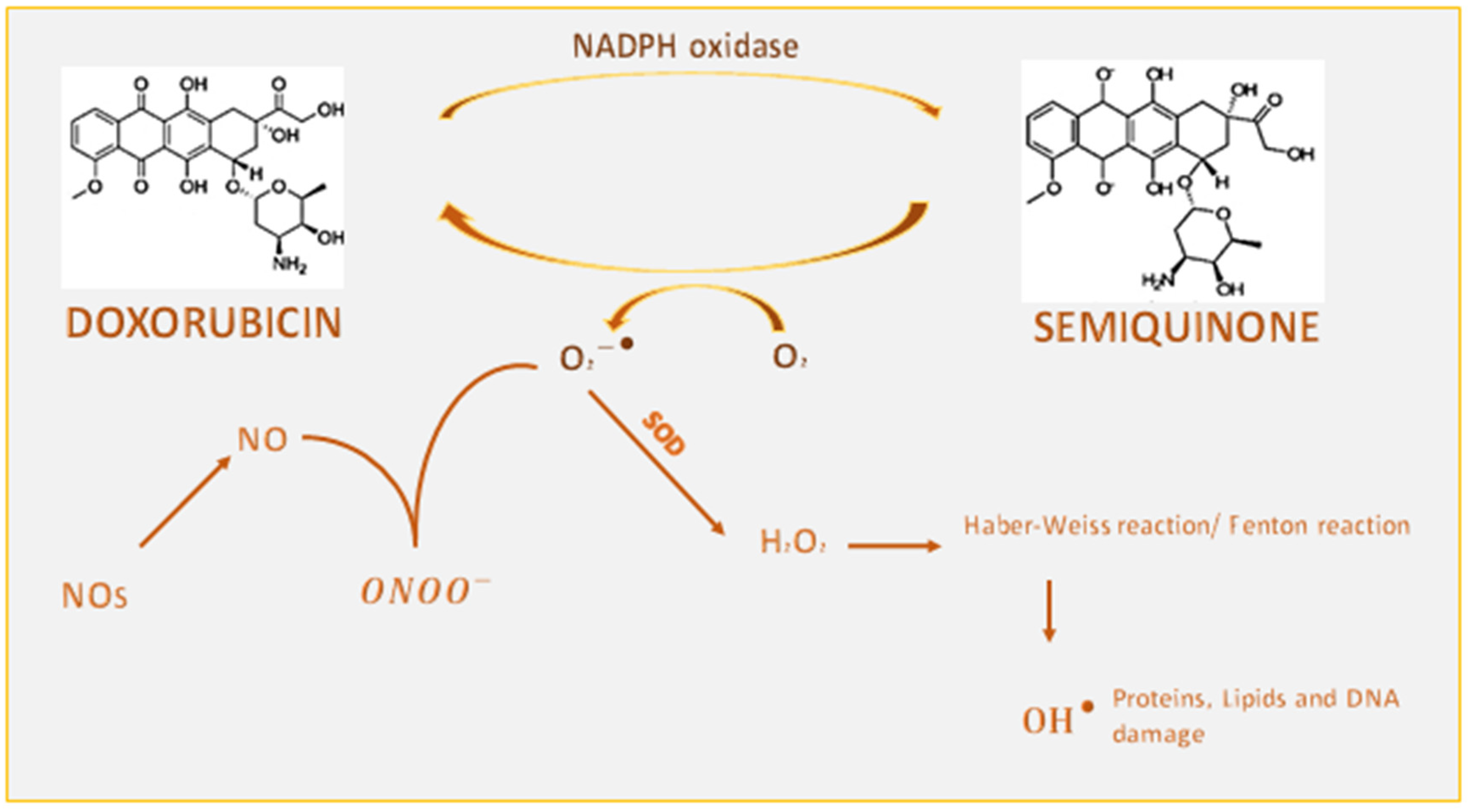

1.1. Involvement of Oxidative Stress in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

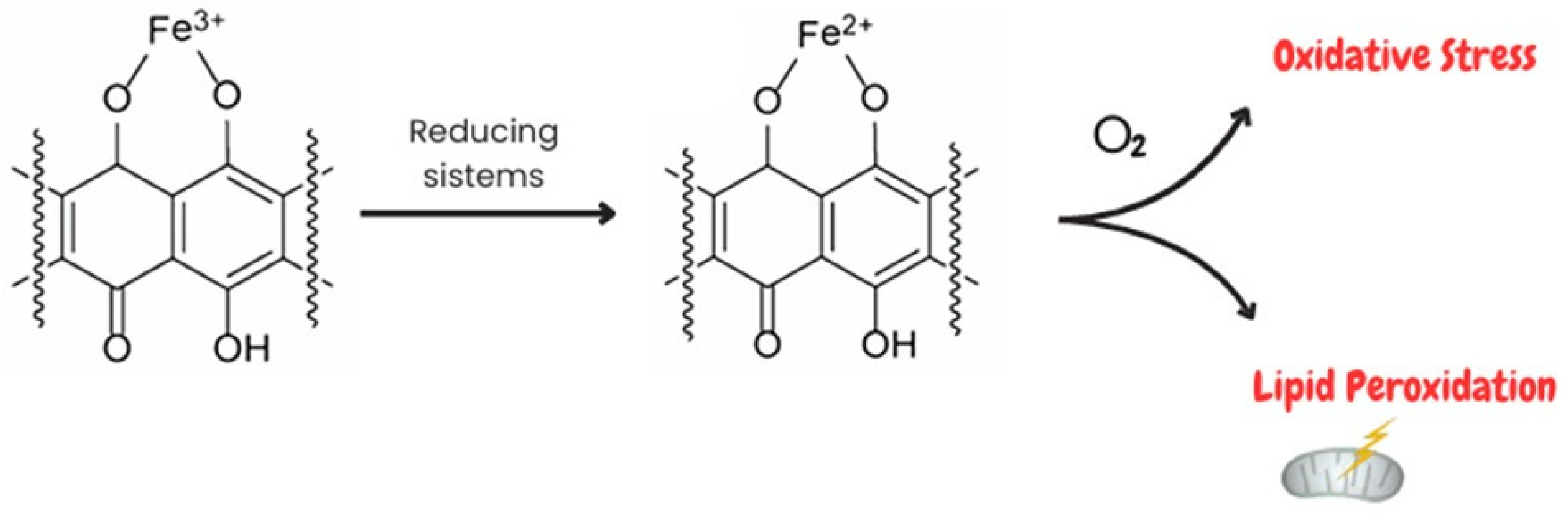

1.1.1. Interference of Doxorubicin with Redox Cycling and Iron Metabolism

1.2. Effects of Doxorubicin on Mitochondria

1.3. Effects of Doxorubicin on NOX Signalling

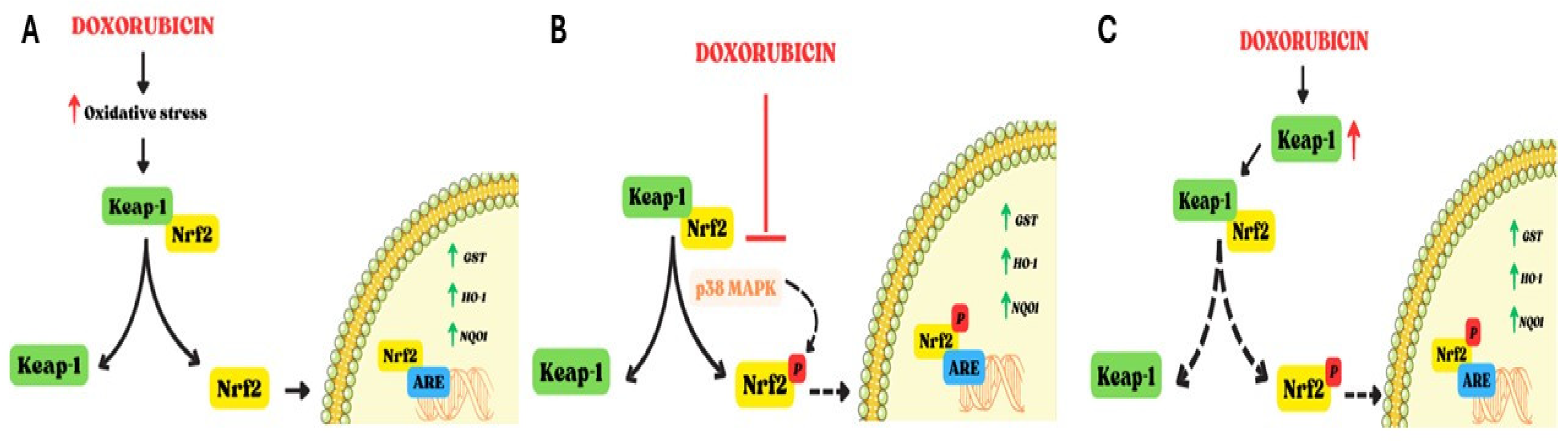

1.4. Effects of Doxorubicin on Nrf2

1.5. Involvement of Nitrosative Stress in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

2. Involvement of Inflammation in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

3. Therapeutic Strategies to Counteract Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity

5. Conclusions

References

- Curigliano, G.; Cardinale, D.; Dent, S.; Criscitiello, C.; Aseyev, O.; Lenihan, D.; Cipolla, C.M. Cardiotoxicity of anticancer treatments: Epidemiology, detection, and management. CA Cancer J Clin 2016 66 (4): 309-25. [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Wagle, N.S.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2023 73 (1): 17-48. [CrossRef]

- Hershman, D.L.; Neugut, A.I. Anthracycline cardiotoxicity: one size does not fit all! J Natl Cancer Inst 2008 100 (15): 1046-7.

- Angsutararux, P.; Luanpitpong, S.; Issaragrisil, S. Chemotherapy-Induced Cardiotoxicity: Overview of the Roles of Oxidative Stress. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2015 2015:795602.

- Timm, K.N. and Tyler, D.J. The Role of AMPK Activation for Cardioprotection in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2020 34 (2): 255-269. [CrossRef]

- Schirone, L.; D’Ambrosio, L.; Forte, M.; Genovese, R.; Schiavon, S.; Spinosa, G.; Iacovone, G.; Valenti, V.; Frati, G.; Sciarretta, S. Mitochondria and Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy: A Complex Interplay. Cells 2022 11 (13): 2000. [CrossRef]

- Fabiani, I.; Aimo, A.; Grigoratos, C.; Castiglione, V.; Gentile, F.; Saccaro, L.F.; Arzilli, C.; Cardinale, D.; Passino, C.; Emdin, M. Oxidative stress and inflammation: determinants of anthracycline cardiotoxicity and possible therapeutic targets. Heart Fail Rev 2021 26 (4): 881-890. [CrossRef]

- Stěrba, M.; Popelová, O.; Vávrová, A.; Jirkovský, E.; Kovaříková, P.; Geršl, V.; Simůnek, T. Oxidative stress, redox signaling, and metal chelation in anthracycline cardiotoxicity and pharmacological cardioprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013 18 (8): 899-929. [CrossRef]

- Hrdina, R.; Gersl, V.; Klimtová, I.; Simůnek, T.; Machácková, J.; Adamcová, M. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity. Acta Medica (Hradec Kralove) 2000 43(3):75-82. PMID: 11089274.

- Kong, C.Y.; Guo, Z.; Song, P.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.P.; Teng. T.; Yan, L.; Tang, Q.Z.; Underlying the Mechanisms of Doxorubicin-Induced Acute Cardiotoxicity: Oxidative Stress and Cell Death. International Journal of Biological Sciences 2022 18(2) :760-770. [CrossRef]

- Octavia, Y.; Tocchetti, C.G.; Gabrielson, K.L.; Janssens, S.; Crijns, H.J.; Moens, A.L. Doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2012 52 (6): 1213-25. [CrossRef]

- Milczarek, A.; Starzyński, R.R.; Styś, A.; Jończy, A.; Staroń, R.; Grzelak, A.; Lipiński, P. A drastic superoxide-dependent oxidative stress is prerequisite for the down-regulation of IRP1: Insights from studies on SOD1-deficient mice and macrophages treated with paraquat. PLoS One 2017 12 (5): e0176800. [CrossRef]

- Kciuk, M.; Gieleci’nska, A.; Mujwar, S.; Kołat, D.; Kałuzi´nska-Kołat, Z.; Celik, I.; Kontek, R. Doxorubicin—An Agent with Multiple Mechanisms of Anticancer Activity. Cells 2023 12, 659. [CrossRef]

- Bhagat, A.; Shrestha, P.; Kleinerman, E.S. The Innate Immune System in Cardiovascular Diseases and Its Role in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity. Int J Mol Sci 2022 23 (23): 14649. [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.H.; Fefelova, N.; Pamarthi, S.H.; Gwathmey, J.K. Molecular Mechanisms of Ferroptosis and Relevance to Cardiovascular Disease. Cells. 2022 11(17):2726. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Zhong, T.; Ma, Y.; Wan, X.; Qin, A.; Yao, B.; Zou, H.; Song, Y.; Yin, D. Bnip3 mediates doxorubicin induced cardiomyocyte pyroptosis via caspase-3/GSDME. Life Sci. 2020 242:117186.

- Zilinyi, R.; Czompa, A.; Czegledi, A.; Gajtko, A.; Pituk, D.; Lekli, I.; Tosaki, A. The Cardioprotective Effect of Metformin in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: The Role of Autophagy. Molecules 2018 23 (5): 1184. [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Chen, Y.; Luo, Z.; Nie, G.; Dai, Y. Role of oxidative stress and inflammation-related signaling pathways in doxorubicin-induced cardiomyopathy. Cell Commun Signal 2023 21 (1): 61. [CrossRef]

- Aryal, B.; Rao, V.A. Deficiency in Cardiolipin Reduces Doxorubicin-Induced Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage in Human B-Lymphocytes. PLoS One 2016 11 (7): e0158376. [CrossRef]

- Christidi, E.; Brunham, L.R. Regulated cell death pathways in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Cell Death Dis 2021 12 (4): 339. [CrossRef]

- Ruggeri, C.; Gioffré, S.; Achilli, F.; Colombo, G.I.; D’Alessandra, Y. Role of microRNAs in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: an overview of preclinical models and cancer patients. Heart Fail Rev 2018 23 (1): 109-122. [CrossRef]

- Panpan, T.; Yuchen, D.; Xianyong, S.; Meng, L.; Ruijuan, H.; Ranran, D.; Pengyan, Z.; Mingxi, L.; Rongrong, X. Cardiac Remodelling Following Cancer Therapy: A Review. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2022 22 (9): 771-786. [CrossRef]

- Perfettini, J.L.; Roumier, T.; Kroemer, G. Mitochondrial fusion and fission in the control of apoptosis. Trends Cell Biol. 2005 Apr;15(4):179-83. [CrossRef]

- Corrado, M.; Scorrano, L.; Campello, S. Mitochondrial dynamics in cancer and neurodegenerative and neuroinflammatory diseases. Int J Cell Biol. 2012 2012:729290. [CrossRef]

- Aung, L.H.H.; Li, R.; Prabhakar, B.S.; Li, P. Knockdown of Mtfp1 can minimize doxorubicin cardiotoxicity by inhibiting Dnm1l-mediated mitochondrial fission. J Cell Mol Med. 2017 Dec; 21(12):3394-3404. [CrossRef]

- Antonny, B., Burd, C., De Camilli, P., Chen, E., Daumke, O., Faelber, K., Ford, M.; Frolov, V.A.; Frost, A.; Hinshaw, J.E.; Kirchhausen, T.; Kozlov, M.M.; Lenz, M.; Low, H.H.; McMahon, H.; Merrifield, C.; Pollard, T.D.; Robinson, P.J.; Roux, A.; Schmid, S. Membrane fission by dynamin: What we know and what we need to know. EMBO J. 2016 35 (21): 2270–2284. [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, A.; Fu, M.; Dong, Z.; Hu, K.; Yang, X.; Zou, Y.; Sun, A.; Qian, J.; Ge, J. LCZ696 improves cardiac function via alleviating Drp1-mediated mitochondrial dysfunction in mice with doxorubicin-induced dilated cardiomyopathy. Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology. 2017 108: 138-148. [CrossRef]

- Miyoshi, T., Nakamura, K., Amioka, N., Hatipoglu, O. F., Yonezawa, T., Saito, Y., Yoshida, M.; Akagi, S.; Ito, H. LCZ696 ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte toxicity in rats. Sci. Rep. 2022 12 (1), 4930. [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Niu, M.; Hu, X.; He, Y. Targeting mitochondrial dynamics proteins for the treatment of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2023 10: 1241225. [CrossRef]

- Bell, E. L., and Guarente, L. The SirT3 divining rod points to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 2011 42 (5): 561–568. [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liu, F.; Li, J. Mitochondrial Sirtuins and Doxorubicin-induced Cardiotoxicity. Cardiovasc Toxicol 2021 21 (3): 179-191. [CrossRef]

- Wallace R. Fractured Symmetries: Information and Control Theory Perspectives on Mitochondrial Dysfunction. Acta Biotheor. 2021 69(3):277-301. [CrossRef]

- Wallace, K.B.; Sardão, V.A.; Oliveira, P.J. Mitochondrial Determinants of Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Circ Res. 2020 126 (7): 926-941. [CrossRef]

- Marechal, X.; Montaigne, D.; Marciniak, C.; Marchetti, P.; Hassoun, S.M.; Beauvillain, J.C.; Lancel. S.; Neviere, R. Doxorubicin-induced cardiac dysfunction is attenuated by ciclosporin treatment in mice through improvements in mitochondrial bioenergetics. Clin Sci (Lond) 2011 121 (9): 405-13. [CrossRef]

- Gilleron, M.; Marechal, X.; Montaigne, D.; Franczak, J.; Neviere, R.; Lancel, S. NADPH oxidases participate to doxorubicin-induced cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 2009 388 (4): 727-731. [CrossRef]

- Brandes, R.P.; Weissmann, N.; Schröder, K. Nox family NADPH oxidases in mechano-transduction: mechanisms and consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal 2014 20 (6): 887-98. [CrossRef]

- Efentakis, P.; Doerschmann, H.; Witzler, C.; Siemer, S.; Nikolaou, P.E.; Kastritis, E.; Stauber, R.; Dimopoulos, M.A.; Wenzel, P.; Andreadou, I.; Terpos, E. Investigating the Vascular Toxicity Outcomes of the Irreversible Proteasome Inhibitor Carfilzomib. Int J Mol Sci 2020 21 (15): 5185. [CrossRef]

- Sirker, A.; Zhang, M.; Shah, A.M. NADPH oxidases in cardiovascular disease: insights from in vivo models and clinical studies. Basic Res Cardiol 2011 106 (5): 735-747. [CrossRef]

- Tayeh, Z.; Ofir, R. Asteriscus graveolens Extract in Combination with Cisplatin/Etoposide/Doxorubicin Suppresses Lymphoma Cell Growth through Induction of Caspase-3 Dependent Apoptosis. Int J Mol Sci 2018 19 (8): 2219. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, P.S.; Jaiswal, A.; Khurana, A.; Bhatti, J.S.; Navik, U. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: An update on the molecular mechanism and novel therapeutic strategies for effective management. Biomed Pharmacother 2021 139: 111708. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; McLaughlin, D.; Robinson, E.; Harvey, A.P.; Hookham, M.B.; Shah, A.M.; McDermott, B.J.; Grieve, D.J. Nox2 NADPH oxidase promotes pathologic cardiac remodeling associated with Doxorubicin chemotherapy. Cancer Res 2010 70 (22): 9287-97. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.G.; Kong, C.Y.; Wu, H.M.; Song, P.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, Y.P.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.Z. Toll-like receptor 5 deficiency diminishes doxorubicin-induced acute cardiotoxicity in mice. Theranostics 2020 10 (24): 11013-11025. [CrossRef]

- Graham, K.A.; Kulawiec, M.; Owens, K.M.; Li, X.; Desouki, M.M.; Chandra, D.; Singh, K.K. NADPH oxidase 4 is an oncoprotein localized to mitochondria. Cancer Biol Ther 2010 10 (3): 223-31. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liao, J.; Luo, Y.; Li, M.; Su, X.; Yu, B.; Teng, J.; Wang, H.; Lv, X. Berberine Alleviates Doxorubicin-Induced Myocardial Injury and Fibrosis by Eliminating Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Damage via Promoting Nrf-2 Pathway Activation. Int J Mol Sci 2023 24 (4): 3257. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2013 53 :401-26. [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Venkannagari, S.; Oh, K.H.; Zhang, Y.Q.; Rohde, J.M.; Liu, L.; Nimmagadda, S.; Sudini, K.; Brimacombe, K.R.; Gajghate, S.; Ma, J.; Wang, A.; Xu, X.; Shahane, S.A.; Xia, M.; Woo, J.; Mensah, G.A.; Wang, Z.; Ferrer, M.; Gabrielson, E.; Li, Z.; Rastinejad, F.; Shen, M.; Boxer, M.B.; Biswal, S. Small Molecule Inhibitor of NRF2 Selectively Intervenes Therapeutic Resistance in KEAP1-Deficient NSCLC Tumors. ACS Chem Biol 2016 11 (11): 3214-3225. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Feng, C.; Jiang, H. Novel target for treating Alzheimer’s Diseases: crosstalk between the Nrf2 pathway and autophagy. Ageing Res Rev. 2021 65:101207.

- Pi, J., Bai, Y., Reece, J. M., Williams, J., Liu, D., Freeman, M. L., Waalkes, M. P. Molecular mechanism of human Nrf2 activation and degradation: Role of sequential phosphorylation by protein kinase CK2. Free Radical Biology and Medicine 2007 42(12), 1797–1806.

- Chen, W., Sun, Z., Wang, X.-J., Jiang, T., Huang, Z., Fang, D., & Zhang, D. D. Direct interaction between Nrf2 and p21Cip1/WAF1 upregulates the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. Molecular Cell 2009 34(6), 663–673.

- Ichimura, Y., Waguri, S., Sou, Y.S., Kageyama, S., Hasegawa, J., Ishimura, R., Saito, T.; Yang, Y.; Kouno, T.; Fukutomi, T.; Hoshii, T.; Hirao, A.; Takagi, K.; Mizushima, T.; Motohashi, H.; Lee, M.S.; Yoshimori, T.; Tanaka, K.; Yamamoto, M.; Komatsu, M. Phosphorylation of p62 activates the Keap1-Nrf2 pathway during selective autophagy. Molecular Cell 2013 51 (5): 618–631.

- Milani, P., Ambrosi, G., Gammoh, O., Blandini, F., & Cereda, C. (2013). SOD1 and DJ-1 converge at Nrf2 pathway: A clue for antioxidant therapeutic potential in Neurodegeneration. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2013 836760. [CrossRef]

- Su, S., Li, Q., Xiong, C., Li, J., Zhang, R., Niu, Y., Zhao, L.; Wang, Y.; Guo, H. Sesamin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: Involvement of Sirt1 and Mn-SOD pathway. Toxicology Letters 2014 224 (2): 257–263.

- Songbo, M.; Lang, H.; Xinyong, C.; Bin, X.; Ping, Z.; Liang, S. Oxidative stress injury in doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Toxicol Lett 2019 307: 41-48. [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Huang, M.; Wu, H. Protective effect of limonin against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via activating nuclear factor - like 2 and Sirtuin 2 signaling pathways. Bioengineered 2021 12 (1): 7975-7984. [CrossRef]

- Shi, K.N.; Li, P.B.; Su, H.X.; Gao, J.; Li, H.H. MK-886 protects against cardiac ischaemia/reperfusion injury by activating proteasome-Keap1-NRF2 signalling. Redox Biol 2023 62: 102706. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Ahmad, K.A.; Khan, F.U.; Yan, S.; Ihsan, A.U.; Ding, Q. Chitosan oligo saccharides prevent doxorubicin-induced oxidative stress and cardiac apoptosis through activating p38 and JNK MAPK mediated Nrf2/ARE pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2019 305: 54–65.

- Li, N.; Jiang, W.; Wang, W.; Xiong, R.; Wu, X.; Geng, Q. Ferroptosis and its emerging roles in cardiovascular diseases. Pharm Res. 2021 166: 105466.

- Pecoraro, M.; Pala, B.; Di Marcantonio, M.C.; Muraro, R.; Marzocco, S.; Pinto, A.; Mincione, G.; Popolo, A. Doxorubicin induced oxidative and nitrosative stress: Mitochondrial connexin 43 is at the crossroads. Int J Mol Med 2020 46 (3): 1197-1209. [CrossRef]

- Mukhopadhyay, P.; Rajesh, M.; Bátkai, S.; Kashiwaya, Y.; Haskó, G.; Liaudet, L.; Szabó, C.; Pacher, P. Role of superoxide, nitric oxide, and peroxynitrite in doxorubicin-induced cell death in vivo and in vitro. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2009 296 (5): H1466-83. [CrossRef]

- Neilan, T.G.; Blake, S.L.; Ichinose, F.; Raher, M.J.; Buys, E.S.; Jassal, D.S.; Furutani, E.; Perez-Sanz, T.M.; Graveline, A.; Janssens, S.P.; Picard, M.H.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Bloch, K.D. Disruption of nitric oxide synthase 3 protects against the cardiac injury, dysfunction, and mortality induced by doxorubicin. Circulation 2007 116 (5): 506-14. [CrossRef]

- Rawat, D.K.; Hecker, P.; Watanabe, M.; Chettimada, S.; Levy, R.J.; Okada, T.; Edwards, J.G.; Gupte, S.A. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase and NADPH redox regulates cardiac myocyte L-type calcium channel activity and myocardial contractile function. PLoS One 2012 7 (10): e45365. [CrossRef]

- Vásquez-Vivar, J.; Martasek, P.; Hogg, N.; Masters, B.S., Pritchard, K.A.Jr; Kalyanaraman, B. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase-dependent superoxide generation from adriamycin. Biochemistry 1997 36 (38): 11293-7. [CrossRef]

- Cappetta, D.; De Angelis, A.; Sapio, L.; Prezioso, L.; Illiano, M.; Quaini, F.; Rossi, F.; Berrino, L.; Naviglio, S.; Urbanek, K. Oxidative Stress and Cellular Response to Doxorubicin: A Common Factor in the Complex Milieu of Anthracycline Cardiotoxicity. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2017 2017: 1521020. [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Guida, F.; Paparo, L.; Trinchese, G.; Aitoro, R.; Avagliano, C.; Fiordelisi, A.; Napolitano, F.; Mercurio, V.; Sala, V.; Li, M.; Sorriento, D.; Ciccarelli, M.; Ghigo, A.; Hirsch, E.; Bianco, R.; Iaccarino, G.; Abete, P.; Bonaduce, D.; Calignano, A.; Berni Canani, R.; Tocchetti, C.G. The novel butyrate derivative phenylalanine-butyramide protects from doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Eur J Heart Fail 2019 21 (4): 519-528. [CrossRef]

- Bartesaghi, S.; Radi, R. Fundamentals on the biochemistry of peroxynitrite and protein tyrosine nitration. Redox Biol 2018 14: 618-625. [CrossRef]

- Milano, G.; Biemmi, V.; Lazzarini, E.; Balbi, C.; Ciullo, A.; Bolis, S.; Ameri, P.; Di Silvestre, D.; Mauri, P.; Barile, L.; Vassalli, G. Intravenous administration of cardiac progenitor cell-derived exosomes protects against doxorubicin/trastuzumab-induced cardiac toxicity. Cardiovasc Res 2020 116 (2): 383-392. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, H.; Qu, H.; Sun, B. Nitric oxide synthase expressions in ADR-induced cardiomyopathy in rats. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2006 39(6): 759-65. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lin, S.; Wu, W.; Tan, h.; Wang, Z., Cheng, C.; Lu, L.; Zhang, X. Ghrelin prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity through TNF-alpha/NF-kappaB pathways and mitochondrial protective mechanisms. Toxicology 2008 247 (2-3):133-8. [CrossRef]

- Pecoraro, M.; Del Pizzo, M.; Marzocco, S.; Sorrentino, R.; Ciccarelli, M.; Iaccarino, G.; Pinto, A.; Popolo, A. Inflammatory mediators in a short-time mouse model of doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 2016 293: 44-52. [CrossRef]

- Tsutsui, H.; Kinugawa, S.; Matsushima, S. Oxidative stress and heart failure. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2011 (6): H2181-90. [CrossRef]

- Shirazi, L.F.; Bissett, J.; Romeo, F.; Mehta, J.L. Role of Inflammation in Heart Failure. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2017 19 (6):27. [CrossRef]

- Bartekova, M.; Radosinska, J.; Jelemensky, M.; Dhalla N.S. Role of cytokines and inflammation in heart function during health and disease. Heart Failure Rev 2018 23 (5): 733-758. [CrossRef]

- Tavakoli, D. Z.; Singla, D.K. Embryonic stem cell-derived exosomes inhibit doxorubicin-induced TLR4-NLRP3-mediated cell death-pyroptosis. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2019 317(2): H460-H471. [CrossRef]

- Singla, D.K.; Johnson, T.A.; Tavakoli, D. Z. Exosome Treatment Enhances Anti-Inflammatory M2 Macrophages and Reduces Inflammation-Induced Pyroptosis in Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiomyopathy. Cells 2019 8(10): 1224. [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Zhang, X.; Xiamo, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y.; Ma, W., Wang, X.; Song, P.; Lai, L.; Chen, H.; Zhan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Yu, M.; Ge, C.; Li, C.; Yin, R.; Yang, X. ABRO1 promotes NLRP3 inflammasome activation through regulation of NLRP3 deuibiquitination. The EMBO Journal 2019 Mar 15;38(6): e100376. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.L.; Wei, L.; Zhang, N.; Wei, W.Y.; Hu, C.; Deng, W.; Tang, Q.Z. Levosimendan Protects against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Regulating the PTEN/Akt Pathway. Biomed Res Int. 2020 2020 :8593617. [CrossRef]

- Ni, C.; Ma, P.; Wang, R.; Lou, X.; Liu, X.; Qin, Y.; Xue, R.; Blasig, I.; Erben, U.; Qin, Z. Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity involves IFNγ-mediated metabolic reprogramming in cardiomyocytes. J Pathol 2019 247(3): 320-332. [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Shi, X.; Xu, J.; Dai, S.; Xu, J.; Fan, X.; Han, B.; Han, J. Gasdermin D mediates doxorubicin-induced cardiomyocyte pyroptosis and cardiotoxicity via directly binding to doxorubicin and changes in mitochondrial damage. Translational Research. 2022 248: 36-50. [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Wang, Y.; Huang, K.; Zeng, Q. Heat shock protein 22 attenuates doxorubicin induced cardiotoxicity via regulating inflammation and apoptosis. Front Pharm. 2020 11:257.

- D’Angelo, N.A.; Noronha, M.A.; Câmara, M.C.C.; Kurnik, I.S.; Feng, C.; Araujo, V.H.S.; Santos, J.H.P.M.; Feitosa, V.; Molino, J.V.D.; Rangel-Yagui, C.O.; Chorilli, M.; Ho, E.A.; Lopes, A.M. Doxorubicin nanoformulations on therapy against cancer: An overview from the last 10 years. Biomaterials Advances. 2022 133:112623. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.R.; Cheng, X.H.; Zhang, G.N.; Wang, X.X.; Huang, J.M. Cardiac safety analysis of first-line chemotherapy drug pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in ovarian cancer. J Ovarian Res 2022 15 (1):96. [CrossRef]

- Dempke, W.C.M.; Zielinski, R.; Winkler, C.; Silberman, S.; Reuther, S.; Priebe, W. Anthracycline-induced cardiotoxicity — are we about to clear this hurdle? European Journal of Cancer 2023 185: 94-104. [CrossRef]

- Pendlebury, A.; De Bernardo, R.; Rose, P.G. Long-term use of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin to a cumulative dose of 4600 mg/m2 in recurrent ovarian cancer: Anti-Cancer Drugs 2017 28 (7): 815-817. [CrossRef]

- Misra, R.; Das, M.; Sahoo, B.S.; Sahoo, S.K. Reversal of multidrug resistance in vitro by co-delivery of MDR1 targeting siRNA and doxorubicin using a novel cationic poly(lactide-co-glycolide) nanoformulation. International Journal of Pharmaceutics 2014 475 (1-2): 372-384. [CrossRef]

- Xing, M.: Yan, F.; Yu, S.; Shen, P. Efficacy and Cardiotoxicity of Liposomal Doxorubicin Based Chemotherapy in Advanced Breast Cancer: A Meta-Analysis of Ten Randomized Controlled Trials. PLoS ONE 2015 10(7): e0133569. [CrossRef]

- Cagel, M.; Grotz, E.; Bernabeu, E.; Moretton, M. A.; Chiappetta, D. A. Doxorubicin: nanotechnological overviews from bench to bedside. Drug Discov. Today 2017 22, 270–281.

- Gallo, E.; Diaferia C.; Rosa, E.; Smaldone, G.; Morelli, G.; Accardo, A. Peptide-Based Hydrogels and Nanogels for Delivery of Doxorubicin. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2021:16 1617–1630.

- Li, J.; Mooney, D.J.Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nat Rev Mater. 2016;1:16071.

- Norouzi, M.;Yathindranath, V.; Thliveris, J.A.; Kopec, B.M.; Siahaan, T.J.; Miller, D.W. Doxorubicin-loaded iron oxide nanoparticles for glioblastoma therapy: a combinational approach for enhanced delivery of nanoparticles Scientific RepoRtS 2020 10:11292 | . [CrossRef]

- Mu, Q.; Kievit, F.M.; Kant, R.J.; Lin, G.; Jeon, M.; Zhang, M. Anti-HER2/neu peptide-conjugated iron oxide nanoparticles for targeted delivery of paclitaxel to breast cancer cells. Nanoscale. 2015;7(43):18010-4.

- Norouzi, M., Nazari, B. & Miller, D. W. Injectable hydrogel-based drug delivery systems for local cancer therapy. Drug Discov. Today 2016 1(11), 1835–1849.

- Zhu, L.; Wang, D.; Wei, X.; Zhu, X.; Li, J.; Tu, C.; Su, Y.; Wu, J.; Zhu, B.; Yan, D. Multifunctional pH-sensitive superparamagnetic iron-oxide nanocomposites for targeted drug delivery and MR imaging. J Control Release. 2013;169(3):228-38.

- Chang, Y.; Li, Y.; Meng, X.; Liu, N.; Sun. D.; Wang, J. Dendrimer functionalized water soluble magnetic iron oxide conjugates as dual imaging probe for tumor targeting and drug delivery. Polym Chem. 2013, 4, 789-794.

- Shen, B.; Ma, Y.; Yu, S.; & Ji C. Smart multifunctional magnetic nanoparticle-based drug delivery system for cancer thermo chemotherapy and intracellular imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2016 , 24502–24508.

- Weiss, G.; Loyevsky, M.; Gordeuk, V.R. Dexrazoxane (ICRF-187). Gen Pharmacol 1999 32 (1): 155-8. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, K.K.; Siddeek, H.; Franco, V.I.; Lipshultz, S.E. Prevention of cardiotoxicity among survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017 83(3): 455-465. [CrossRef]

- Kourek, C.; Touloupaki, M.; Rempakos, A.; Loritis, K.; Tsougkos, E.; Paraskevaidis, I.; Briasoulis, A. Cardioprotective Strategies from Cardiotoxicity in Cancer Patients: A Comprehensive Review. J Cardiovasc Dev Dis 2022 9(8):259. [CrossRef]

- Yue, T.L.; Cheng, H.Y.; Lysko, P.G.; McKenna, P.J.; Feuerstein, R.; Gu, J.L.; Lysko, K.A.; Davis, L.L.; Feuerstein, G. Carvedilol, a new vasodilator and beta adrenoceptor antagonist, is an antioxidant and free radical scavenger. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992 263(1):92-8. PMID: 1357162.

- Spallarossa, P.; Garibaldi, S.; Altieri, P.; Fabbi, P.; Manca, V.; Nasti, S.; Rossettin, P.; Ghigliotti, G.; Ballestrero, A.; Patrone, F.; Barsotti, A.; Brunelli, C. Carvedilol prevents doxorubicin-induced free radical release and apoptosis in cardiomyocytes in vitro. J Mol Cell Cardiol 2004 37 (4): 837-46. [CrossRef]

- Tashakori Beheshti, A.; Mostafavi Toroghi, H.; Hosseini, G.; Zarifian, A.; Homaei Shandiz, F.; Fazlinezhad, A. Carvedilol Administration Can Prevent Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: A Double-Blind Randomized Trial. Cardiology 2016 134(1):47-53. [CrossRef]

- Abuosa, A.M.; Elshiekh, A.H.; Qureshi, K.; Abrar, M.B.; Kholeif, M.A.; Kinsara, A.J.; Andejani, A.; Ahmed, A.H.; Cleland, J.G.F. Prophylactic use of carvedilol to prevent ventricular dysfunction in patients with cancer treated with doxorubicin. Indian Heart J 2018 Dec; 70 Suppl 3: S96-S100. [CrossRef]

- Moustafa, I.; Connolly, C.; Anis, M.; Mustafa, H.; Oosthuizen, F.; Viljoen, M. A prospective study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of vitamin E and levocarnitine prophylaxis against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in adult breast cancer patients. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2024 Mar; 30(2): 354-366. [CrossRef]

- Riad, A.; Bien, S.; Westermann, D.; Becher, P.M.; Loya, K.; Landmesser, U.; Kroemer, H.K.; Schultheiss, H.P.; Tschöpe, C. Pretreatment with statin attenuates the cardiotoxicity of Doxorubicin in mice. Cancer Res 2009 69(2):695-9. [CrossRef]

- Dadson, K.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Hauck, L.; Grothe, D.; Azam, M.A.; Stanley-Hasnain, S.; Mahiny-Shahmohammady, D.; Si, D.; Bokhari, M.; Lai, P.F.H.; Massé, S. Nanthakumar, K.; Billia, F. Statins Protect Against Early Stages of Doxorubicin-induced Cardiotoxicity Through the Regulation of Akt Signaling and SERCA2. CJC Open 2022 4 (12): 1043-1052. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Lu, X.; Liu, Z.; Du, K. Rosuvastatin reduces the pro-inflammatory effects of adriamycin on the expression of HMGB1 and RAGE in rats. Int J Mol Med 2018 42 (6): 3415-3423. [CrossRef]

- Neilan, T.G.; Quinaglia, T.; Onoue, T.; Mahmood, S.S.; Drobni, Z.D.; Gilman, H.K.; Smith, A.; Heemelaar, J.C.; Brahmbhatt, P.; Ho, J.S.; Sama, S.; Svoboda, J.; Neuberg, D.S.; Abramson, J.S.; Hochberg, E.P.; Barnes, J.A.; Armand, P.; Jacobsen, E.D.; Jacobson, C.A.; Kim, A.I.; Soumerai, J.D.; Han, Y.; Friedman, R.S.; Lacasce, A.S.; Ky, B.; Landsburg, D.; Nasta, S.; Kwong, R.Y.; Jerosch-Herold, M.; Redd, R.A.; Hua, L.; Januzzi, J.L.; Asnani, A.; Mousavi, N.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M. Atorvastatin for Anthracycline-Associated Cardiac Dysfunction: The STOP-CA Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2023 Aug 8; 330(6): 528-536. [CrossRef]

- Makhlin, I.; Demissei, B.G.; D’Agostino, R.; Hundley, W.G.; Baleanu-Gogonea, C.; Wilcox, N.S.; Chen, A.; Smith, A.M.; O’Connell, N.S.; Januzzi, J.; Lesser, G.J.; Scherrer-Crosbie, M.; Ibáñez, B.; Tang, W.H.W.; Ky, B. Statins Do Not Significantly Affect Oxidative Nitrosative Stress Biomarkers in the PREVENT Randomized Clinical Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2024 Apr 4. [CrossRef]

- Tatlidede, E.; Sehirli, O.; Velioğlu-Oğünc, A.; Cetinel, S.; Yeğen, B.C.; Yarat, A.; Süleymanoğlu, S.; Sener, G. Resveratrol treatment protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by alleviating oxidative damage Free Radic Res 2009 43(3):195-205. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Chen, M.; He, Y.; Zhang, H.; Han, D.; Zheng, L. Resveratrol protects against doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity by attenuating ferroptosis through modulating the MAPK signaling pathway. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2024 Jan; 482:116794. [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Kilany, O.E.; Khalifa, H.A.; Ahmed, A.A.M. Allicin ameliorates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity in rats via suppression of oxidative stress, inflammation and apoptosis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol 2017 80(4):745-753. [CrossRef]

- Ky, B.; Vejpongsa, P.; Yeh, E.T.; Force, T.; Moslehi, J.J. Emerging paradigms in cardiomyopathies associated with cancer therapies. Circ Res 2013 113 (6): 754-64. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yu, P.; Gou, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Z.H.; Tian, J.W.; Jiang, Y.T.; Fu, F.H. Cardioprotective Effects of 20(S)-Ginsenoside Rh2 against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity In Vitro and In Vivo. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012 2012: 506214. [CrossRef]

- Priya, L.B.; Baskaran, R.; Huang, C.Y.; Padma, V.V. Neferine ameliorates cardiomyoblast apoptosis induced by doxorubicin: possible role in modulating NADPH oxidase/ROS-mediated NFκB redox signaling cascade. Scientific Reports 2017 7(1) :12283. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Wang, Q.; Sun, S.; Xu. G.; Wu, Q.; Qi, M.; Bai, F.; Yu, J. Astragaloside IV promotes the eNOS/NO/cGMP pathway and improves left ventricular diastolic function in rats with metabolic syndrome. Journal of International Medical Research 2019 48 (1): 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Afsar, T.; Razak, S.; Batoo, K.M.; Khan, M.R. Acacia hydaspica R. Parker prevents doxorubicin-induced cardiac injury by attenuation of oxidative stress and structural Cardiomyocyte alterations in rats. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017 17(1):554. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, M.; Liu, J.; Ye, J.; Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Ye, D.; Li, D.; Wan, J. Resolvin D1 Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity by Inhibiting Inflammation, Oxidative and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress. Front Pharmacol 2022 12: 749899. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, D.; Chen, L.; Tu, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, Q.; Meng, L.; Li, Z.; Yu, Q. Protective effects of valsartan administration on doxorubicin induced myocardial injury in rats and the role of oxidative stress and NOX2/NOX4 signaling. Mol Med Rep. 2020 22(5): 4151-4162. [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, P.L.; Chu, P.M.; Cheng, H.C.; Huang, Y.T.; Chou, W.C.; Tsai, K.L.; Chan, S.H. Dapagliflozin Mitigates Doxorubicin-Caused Myocardium Damage by Regulating AKT-Mediated Oxidative Stress, Cardiac Remodeling, and Inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2022 23(17):10146. [CrossRef]

- Draginic, N.; Jakovljevic, V.; Andjic, M.; Jeremic, J.; Srejovic. I.; Rankovic, M.; Tomovic, M.; Nikolic, Turnic T.; Svistunov, A.; Bolevich, S.; Milosavljevic, I. Melissa officinalis L. as a Nutritional Strategy for Cardioprotection. Front Physiol. 2021 12: 661778. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.F.; Tang, F.; Chen, L.; Tan, Y.Z.; Rao, C.L.; Ao, H.; Peng, C. Panax ginseng and its ginsenosides: potential candidates for the prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced side effects. J Ginseng Res. 2021 Nov;45(6):617-630. [CrossRef]

- You, J.S.; Huang, H.F.; Chang, Y.L. Panax ginseng reduces adriamycin-induced heart failure in rats. Phytother Res 2005 19 (12): 1018-22. [CrossRef]

- Syahputra, R.A.; Harahap, U.; Dalimunthe, A.; Nasution, M.P.; Satria, D. The Role of Flavonoids as a Cardioprotective Strategy against Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity: A Review. Molecules 2022 27 (4): 1320. [CrossRef]

- Yu,W.; Sun, H.; Zha, W.; Cui, W.; Xu, L.; Min, Q.; Wu, J. Apigenin Attenuates Adriamycin-Induced Cardiomyocyte Apoptosis via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR Pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2017 2017: 2590676. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, J.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.; Ren, J.; Yang, J. Rutin attenuates doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity via regulating autophagy and apoptosis. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis 2017 Aug; 1863 (8): 1904-1911. [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.B.; Lu, Z.Y.; Yuan, W.; Li, W.D.; Mao, S. Selenium Attenuates Doxorubicin-Induced Cardiotoxicity Through Nrf2-NLRP3 Pathway. Biol Trace Elem Res 2022 200 (6): 2848-2856. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).