Submitted:

24 May 2024

Posted:

27 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

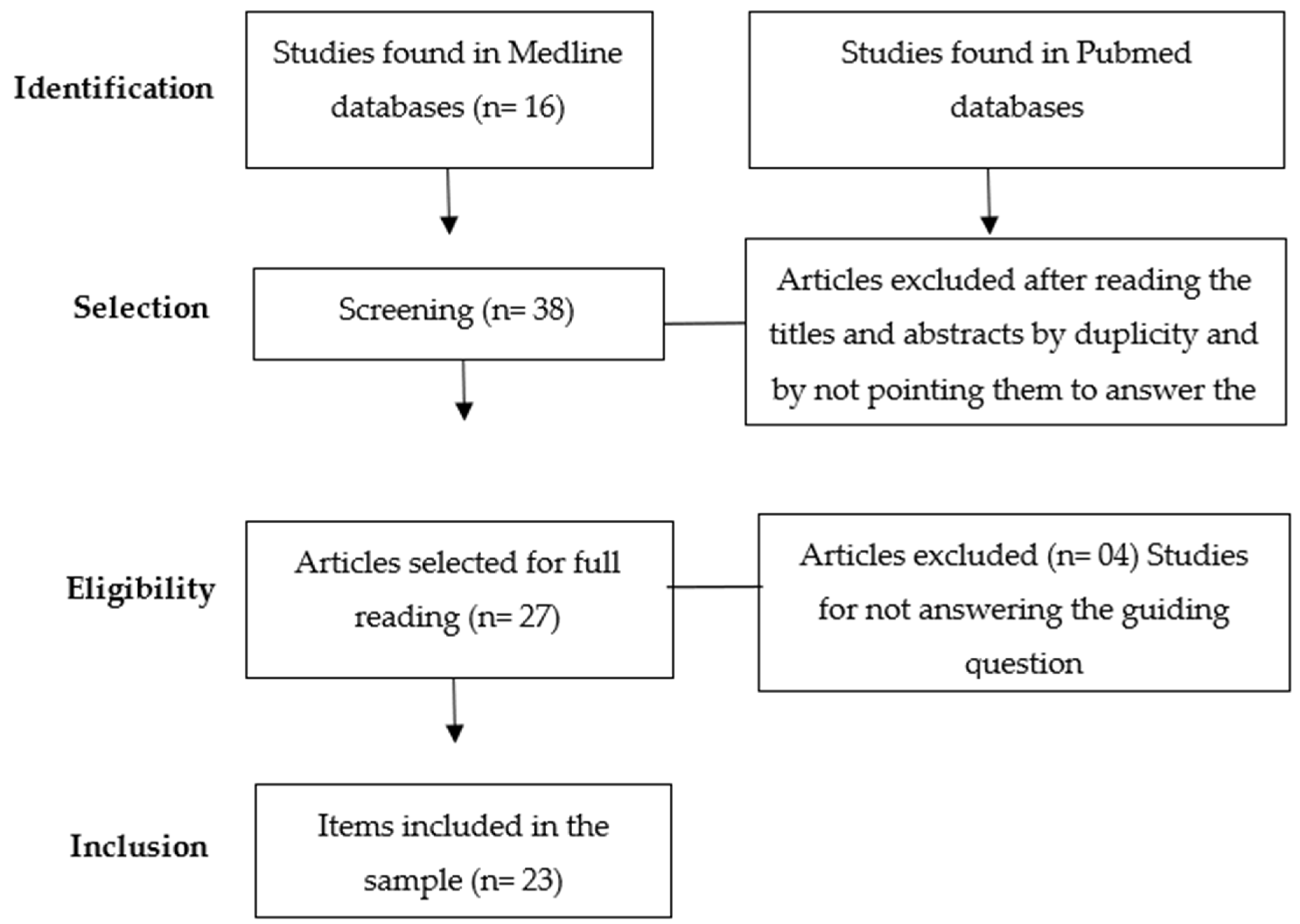

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Biological, Behavioral and Environmental Risk Factors for the Development of Chronic Non-Communicable Diseases in Long-Haul Truck Drivers

4.2. General Recommendations to Promote Physical, Cognitive and Emotional Health in Long-Haul Truck Drivers

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Contributions to Practice and Future Studies:

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bispo Júnior, J.P.; dos Santos, D.B. COVID-19 as a syndemic: a theoretical model and foundations for a comprehensive approach in health. Cad Saude Publica 2021, 37, e00119021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Word Health Organization. Discussion Paper on the development of an implementation roadmap 2023-2030 for the WHO Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2023-2030). 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/implementation-roadmap-2023-2030-for-the-who-global-action-plan-for-the-prevention-and-control-of-ncds-2023-2030 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- International Labour Organization. Advancing the global agenda on prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases 2000 to 2020: looking forwards to 2030. 2023. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/370425/9789240072695-eng.pdf?sequence=1 (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Cardoso, M.; Fulton, F.; Callaghan, J.P.; Johnson, M.; Albert, W.J. A pre/post evaluation of fatigue, stress and vigilance amongst commercially licensed truck drivers performing a prolonged driving task. Int J Occup Saf Ergon 2019, 25, 344–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Josseran, L.; Mcneill, K.; Fardini, T.; Sauvagnac, R.; Barbot, F.; Salva, M.A.Q.; Bowser, M.; King, G. Smoking and obesity among long-haul truck drivers in France. Tob Prev Cessat 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shattell, M.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S.; Griffin, M. Occupational stressors and the mental health of truckers. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2010, 31, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pega, F.; Náfrádi, B.; Momen, N.C.; Ujita, Y.; Streicher, K.N.; Prüss-Üstün, A.M.;... & Woodruff, T. J. Global, regional, and national burdens of ischemic heart disease and stroke attributable to exposure to long working hours for 194 countries, 2000–2016: A systematic analysis from the WHO/ILO Joint Estimates of the Work-related Burden of Disease and Injury. Environ Int, 2021, 154, 106595. [CrossRef]

- Gragnano, A.; Simbula. S.; Miglioretti, M. Work–life balance: Weighing the importance of work–family and work–health balance. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17, 907. [CrossRef]

- UnitedNations. Sustainable Development Goals Report. 2021. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/ (accessed on 21 May 2024).

- Dhollande, S.; Taylor, A.; Meyer, S.; Scott, M. Conducting integrative reviews: a guide for novice nursing researchers. J Res Nurs 2021, 26, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B.M.; Fineout-Overholt, E. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. 3rd ed.; Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2011.

- Ouzzani, M.; Hammady, H.; Fedorowicz, Z.; Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan — a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J. McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, L.H.; Lichtenstein, B.; St Lawrence, J.S.; Murray, M.; Russell, G.B.; Hook III, E.W. Health risks of American long-haul truckers: results from a multi-site assessment. J Occup Environ Med 2018, 60, e349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, B.; Heaton, K.; Raju, D.; Vance, D.E.; Sieber, W.K. A descriptive study of musculoskeletal injuries in long-haul truck drivers: a NIOSH national survey. Workplace Health Saf 2018, 66, 475–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatami, A.; Vosoughi, S.; Hosseini, A.F.; Ebrahimi, H. Effect of co-driver on job content and depression of truck drivers. Saf Health Work, 2019, 10, 75-79. [CrossRef]

- Hege, A.; Lemke, M.K.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S. Occupational health disparities among US long-haul truck drivers: the influence of work organization and sleep on cardiovascular and metabolic disease risk. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0207322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iseland, T.; Johansson, E.; Skoog, S.; Dåderman, A.M. An exploratory study of long-haul truck drivers’ secondary tasks and reasons for performing them. Accid Anal Prev 2018, 117, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemke, M.K.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Hege, A.; Newnam, S.; Sönmez, S. Can subjective sleep problems detect latent sleep disorders among commercial drivers? Accid Anal Prev 2018, 115, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pylkkönen, M.; Tolvanen, A.; Hublin, C.; Kaartinen, J.; Karhula, K.; Puttonen, S.; Sivola, M.; Sallinen, M. Effects of alertness management training on sleepiness among long-haul truck drivers: A randomized controlled trial. Accid Anal Prev 2018, 121, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodrigues, L.F.S.; Avelar, G.G.; Toledo, J.O.; Camargos, E.F.; Nóbrega, O.T. Perfil de sono, variáveis clínicas e jornada de trabalho de caminhoneiros idosos e de meia-idade em rodovias. Geriatr Gerontol Aging 2018, 2, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bschaden, A.; Rothe, S.; Schöner, A.; Pijahn, N.; Stroebele-Benschop, N. Food choice patterns of long-haul truck drivers driving through Germany, a cross sectional study. BMC Nutrition 2019, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hege, A.; Lemke, M.K; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Sönmez, S. The impact of work organization, job stress, and sleep on the health behaviors and outcomes of US long-haul truck drivers. Health Educ Behav 2019, 46, 626–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hege, A.; Lemke, M.K.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Whitaker, B.; Sönmez, S. Work-life conflict among US long-haul truck drivers: Influences of work organization, perceived job stress, sleep, and organizational support. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019, 16, 984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lalla-Edward, S.T.; Fischer, A.E.; Venter, W.D.F.; Scheuermaier, K.; Meel, R.; Hankins, C.; Gomez, G.; Klipstein-Grobusch, K.; Draijeer, M.; Vos, A.G. Cross-sectional study of the health of southern African truck drivers. BMJ open 2019, 9, e032025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendall, M.C.; McCosker, L.K.; Ahmed, R.; Crane, P. Truckies’ nutrition and physical activity: a cross-sectional survey in Queensland, Australia. Int J Occup Environ Med 2019, 10, 145–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crizzle, A.M.; Mclean, M.; Malkin, J. Risk factors for depressive symptoms in long-haul truck drivers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kagabo, R.; Thiese, M.S.; Eden, E.; Thatcher, A.C.; Gonzalez, M.; Okuyemi, K. Truck drivers’ cigarette smoking and preferred smoking cessation methods. Subst Abuse 2020, 14, 1178221820949262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, J.M.; Heaton, K.; Shattell, M. Mindfulness, sleep, and post-traumatic stress in long-haul truck drivers. Work 2020, 67, 103–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crizzle, A.M.; Malik, S.S.; Toxopeus, R. The impact of COVID-19 on the work environment in long-haul truck drivers. J Occup Environ Med 2021, 63, 1073–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemke, M.K.; Oberlin, D.J.; Apostolopoulos, Y.; Hege, A.; Sönmez, S.; Wideman, L. Work, physical activity, and metabolic health: Understanding insulin sensitivity of long-haul truck drivers. Work 2021, 69, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roche, J.; Vos, A.G.; Lalla-Edward, S.T.; Venter, W.D.F.; Scheuermaier, K. Relationship between sleep disorders, HIV status and cardiovascular risk: cross-sectional study of long-haul truck drivers from Southern Africa. Occup Environ Med 2021, 78, 393–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, M.S.; Nelon, J.L.; Lemke, M.K.; Sönmez, S.; Hege, A.; Apostolopoulos, Y. Exploring the Role of Social Network Structure in Disease Risk among US Long-haul Truck Drivers in Urban Areas. Am J Health Behav 2021, 45, 74–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Useche, S.A.; Alonso, F.; Cendales, B.; Llamazares, J. More than just “stressful”? Testing the mediating role of fatigue on the relationship between job stress and occupational crashes of long-haul truck drivers. Psychol Res Behav Manag 2021, 14, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Modjadji, P.; Bokaba, M.; Mokwena, K.E.; Mudau, T.S.; Monyeki, K.D.; Mphekgwana, P.M. Obesity as a Risk Factor for Hypertension and Diabetes among Truck Drivers in a Logistics Company, South Africa. Appl. Sci 2022, 12, 1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Vred, C.; Xia, T.; Collie, A.; Pritchard, E.; Newnam, S.; Lubman, D.; Lubman, I.D.; Almeida Neto, A.; Iles, R. The physical and mental health of Australian truck drivers: a national cross-sectional study. BMC public health 2022, 22, 464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author/year | Country | Objective | Type of study | Main results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observational (n) |

Experimental (n) |

||||

| BACHMAN et al., 2018 [14]. | USA | Evaluate the general and sexual health of long-haul truck drivers in the United States. | X 266 |

Higher cholesterol levels and higher rates of smoking, obesity and diabetes were identified than the US average. 17.3% reported having had at least one STI in the previous year, the most frequent was gonorrhea (63.6%). STD/HIV infection rates were lower than the US average. | |

| COMBS et al., 2018 [15]. | USA | Investigate work-related musculoskeletal injuries in long-haul truck drivers. | X 1,265 |

The majority of lesions were on the arm (26.3%) and back (21.1%). Musculoskeletal injuries were most frequently caused by falls (38.9%) and contact with an object or equipment (33.7%), resulting more commonly in sprains (60%). | |

| HATAMI et al., 2018 [16]. | Iran | Investigate the effect of co-pilots on depression and occupational stress in truck drivers. |

X 70 drivers (33 drivers with co-pilot – intervention group. 37 drivers without co-pilot – control group) |

The depression rate in drivers with co-pilot is really lower than the depression rate in drivers without co-pilot. | |

| HEGE et al., 2018 [17]. | USA | Better understand the impacts of the unique characteristics of the work organization experienced by long-haul truck drivers and better explain the disparities in the risks of cardiometabolic diseases compared to the general population of the US. | X 115 |

62.5% characterized their stress as a moderate to chronic level. 84.6% of drivers were on the road 21 or more days a month. 70% worked more than 11 hours a day and 82.7% experienced a work schedule that varies each day. 68% of drivers reported a fast pace of work and 77.7% reported having timepressures. Longer sleep duration on working days (average 8.27 on working days vs. 6.95 hours on business days). 11% diagnosis of sleep apnea. | |

| ISELAND et al., 2018 [18]. | Sweden | Investigate whether long-haul truck drivers in Sweden engage in secondary tasks while driving, what tasks are performed and how often. | X 13 |

The secondary tasks, the interaction with the cell phone was mainly for communication, entertainment (social media and music) and GPS. They referred to perform them to reduce boredom, stress. | |

| LEMKE et al., 2018 [19]. | USA | Evaluate the value of subjective screening methods to detect latent sleep disorders and identify truck drivers at risk for poor sleep health and safety. | X 260 |

Five factors of latent sleep disorder were extracted: 1) circadian rhythm sleep disorders; 2) sleep-related respiratory disorders; 3) parasomnias; 4) insomnia; 5) and sleep-related movement disorders. Patterns of associations between these factors usually corresponded to risk factors and known symptoms. One or more factors of latent sleep disorder extracted were significantly associated with all the health and safety of sleep results. | |

| PYLKKÖNEN et al., 2018 [20]. | Finland | Examine the effects of an educational intervention on the drowsiness of long-haul truck drivers at the wheel, amount of sleep between work changes and use of efficient countermeasures of drowsiness in association with night and non-night. | X 53 |

The results of multilevel regression models did not show significant improvements related to intervention in driver drowsiness, previous sleep while working in night shifts and early morning shifts compared to daytime and/or night shifts. | |

| RODRIGUES et al., 2018 [21]. | Brazil | To investigate the association of variables representative of the sociodemographic profile, the working day and of the general health conditions of freight transport professionals on highways with the reported sleep regime. |

X 367 |

Prevalence of overweight men, 26% reported being hypertensive and 9% diabetic, 32% used drugs. 30% worked more than eight hours a day. 18% smokers, 39% consumed alcohol. | |

| BSCHADEN et al., 2019 [22]. | Germany | Describe the characteristics and patterns of food choice of long-haul truck drivers while working compared to food standards at home. | X 404 |

24% had normal weight, 46% overweight and 30% obese. More than 50% reported being a smoker 32% reportedat least one chronic disease. 37% had their meals frequently or always at truck stops, 6% never did it. 73% reported eating food brought from home. The items brought at home were fruits (62%), sausages (50.6%), sandwiches (38.7%), pre-ready meals (37%), sweets (35.4%) and raw vegetables (31%). 94% had in the truck, refrigerator, 62% gas pot and 8% microwave and eat less often in the places of stopping and resting. | |

| HEGE; APOSTOLOPOULOS; SÖNMEZ, 2019 [23]. | USA | Explore the connections between the organization of long-haul truck driver work, stress at work, sleep and health. | X 260 |

More than 70% reported working more than 11 hours a day. This resulted in higher odds of high caffeine consumption, high stress at work and low sleep quality. 46% reported sleeping less than seven hours a day. 48% consumed alcohol on non-work days. 48% were smokers. | |

| HEGE et al., 2019 [24]. | USA | Investigate whether adversity in the organization of work, stress and sleep health problems among long-haul truck drivers are significantly associated with professional life conflict. | X 260 |

Stress in perceived work was the only statistically significant predictor for work-life balance. Rapid pace of work, duration and sleep quality were predictors of stress at perceived work. | |

| LALLA-EDWARD et al., 2019 [25]. | South Africa | Evaluate and describe the health information of truck drivers in South Africa. | X 614 |

86% had sex with a regular partner; 27% had a casual partner; 14% had sex with a sex worker. 50% never worked in the night shift 12% worked nights approximatelyfour times a week. 8% were HIV positive, with half taking antiretrovirals. | |

| SENDAL et al., 2019 [26]. | Australia | Examine self-reported behavior of diet and physical activity. | X 231 |

85% worked more than nine hours a day. Halfconsumed less fruits and 88% consumed less vegetables national recommendations. 63% consumed at least one harmful food a day and 65% drank at least one can of sugary drink a day. 90% of drivers had above body mass index e60% were obese. | |

| CRIZZLE; MALKIN, 2020 [27]. | Canada | Identify predictors of depressive symptoms | X 107 |

95% of the participants were male, 44% reported symptoms of depression in the last 12 months. The results suggest that occupational stressors increase the risk of depression symptoms. There was a significant association between depressive symptoms with annual income and weeks worked. | |

| KAGABO et al., 2020 [28]. | USA | Describe the characteristics of smoking and identify their preferred methods of smoking cessation among truck drivers. | X 37 |

The reasons for smoking included staying awake, reducing stress or having something to do while driving. 68.8% were daily smokers. The average number of cigarettes per day was 15.7. 65% made at least one attempt to stop. | |

| WISE; HEATON; SHATTELL, 2020 [29]. | USA | Examine the relationship between sleep, mental health, health care use, And mindfulness on long-haul truck drivers in the United States. |

X 140 |

70% of the participants were female, 90% Caucasian, mean 37 years of age. 14% presented symptoms of depression, 10% anxiety or loneliness. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and daytime sleepiness were identified. Mindfulness was inversely correlated with the symptomatology of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder. | |

| CRIZZLE; MALIK; TOXOPEUS, 2021 [30]. | Canada | Describe and compare the working conditions of long-distance truck drivers before and during coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) and evaluate drivers’ perceptions about access to food, bathrooms and parking. | X 146 |

Participants reported problems to find parking, bathrooms and food, compared to before COVID-19, drivers worked significantly more hours and consumed more caffeine; And more than 50% reported being tired. | |

| lemke et al., 2021 [31]. | USA | Compare the insulin sensitivity of truck drivers and associations between metabolic risk and insulin sensitivity factors, with those of the general population. | X 115 |

Most of the interviewees had 47.6, were white and had a diagnosis of diabetes. 13% used diabetes medicines and 67% were obese. The average insulin concentration was higher among truck drivers but the average glucose concentrations were lower among truck drivers compared to NHANE participants. | |

| ROCHE et al., 2021 [32]. | South Africa | To assess whether sleep disorders and circadian misalignment were associated with chronic inflammation and risk of cardiovascular diseases. | X 575 |

Mean age of 37 years. 17% were at risk of obstructive sleep apnea, 72.0% had high blood pressure, 9.4% had HIV and 28.0% were obese.Sleep duration was an average of seven hours and 49.6% reported work in the night shift at least once a week. | |

| PATTERSON et al., 2021 [33]. | USA | Explore the properties of the social networks of long-haul truck drivers Potentially influencing the acquisition and transmission of Sexually Transmitted Infections. |

X 58 male truck drivers 24 sex professionals and 6 male intermediaries |

27% tested positive for STI/HIV or hepatitis. People who tested negative for an infection involved in sex and/or drug exchanges with people who tested positive, increasing their risk of infection/transmission to other contacts. | |

| USECHE et al., 2021 [34]. | Spain | To assess whether work-related fatigue is a mechanism that mediates the relationship between work stress, health indicators and occupational traffic accidents with truck drivers. | X 521 |

47.9% were male, 53% worked five to eight hours a day. The work traffic accidents of long-haul truck drivers can be explained through work-related fatigue that mediates between stress at work (stress at work), health-related factors and traffic accidents suffered during the previous two years. | |

| MODJADJI et al., 2022 [35]. | South Africa | Determine the prevalence of obesity and its association with systemic arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus. | X 96 |

The prevalence of overweight (44%) and obesity (30%), high abdominal obesity; 57% hypertensive and 14% diabetic. | |

| VREDEN et al., 2022 [36]. | Australia | To characterize the physical and mental health of Australian truck drivers in general, and to identify any differences in factors that influence the health profile of long-haul truck drivers to short-term drivers. | X 1390 |

Most respondents were overweight or obese. Almost a third reported three or more chronic health conditions such as hypertension, mental health problems. Long-haul truck drivers were more likely to be obese and reported pain lasting more than a year. Having more than one diagnosed chronic condition was associated with poor mental and physical health outcomes in long- and short-haul drivers. | |

| Domain | Risk Factor | Detail | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological (non-modifiable) | Age | (>45 years) | [14,15,17,19,21,22,23,27,30,35,36]. |

| Sex | Male | [14,15,17,18,21,22,25,27,28,30,31,32,34,36]. | |

| Female | [29]. | ||

| Race | Caucasian | [14,15,19,27,29,30,31]. | |

| Afro-descendants | [32]. | ||

| Chronic disease | Diabetes mellitus Systemic arterial hypertension Metabolic syndrome |

[14,17,19,21,22,25,30,36]. | |

| Behavioral and/or environmental (modifiable) | Education | Up to eight years | [21,27]. |

| >eight years | [14,22,30]. | ||

| Physical activity | Sedentary | [17,23,25,31,32,35]. | |

| Habit of smoking | Smoking | [14,21,22,23,25,28,30,35]. | |

| Alcohol consumption | Working days/Days off | [17,21,27,30,35]. | |

| Overweight/Obesity | [14,17,21,22,25,26,27,30,32,35,36]. | ||

| Diet | Food | [22,23,26]. | |

| Socioeconomic conditions | Salary | [14,30]. | |

| Mental health | Anxiety/ stress/depression/sleep and fatigue | [16,17,19,23,25,27,29,30,36]. | |

| Occupational safety | [18]. | ||

| Working days per week/month | [22,23,25,30,34]. | ||

| Working hours per day | [21,23,25,32,34,36]. | ||

| Hours of sleep | [21,29,30,32]. | ||

| Time out of the house | Loneliness | [14,18,22,23]. | |

| Ergonomic risk | skeletal muscle injury | [15,22,25,36]. | |

| Access to health services | [14,27]. |

| Domain | Recommendation | Justification | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological | Prevent and control hypertension, diabetes mellitus and obesity | Monitor height, weight and abdominal circumference and body mass index. Supporting initiatives promoting health education, physical activity, healthy diet, opportunities for rest, sleep and access to medicines and health services, as well as reducing stress, smoking, alcohol consumption, contributes to reducing morbidity and mortality by NCD, promotes physical and mental health. | [14,23,31,32]. |

| Behavioral | Promote regular physical activity | It reduces the risk of diseases such as obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, obstructive sleep apnea, stress, fatigue, pain and anxiety. Increases safety, improves concentration and sleep. |

[14,17,23,31,32]. |

| Provide healthy eating | Decreases salt intake, saturated trans-fat contributes to reduce overweight and risk of cardiometabolic diseases. Improves memory and increases well-being. |

[14,17,22]. | |

| Provide adequate amount of sleep hours | Health education on the importance of maintaining circadian rhythm with up to eight hours of sleep and implementing measures to respect sleep and rest time can contribute to the prevention of cardiovascular diseases, decreases blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, obesity, pain, memory loss, stress and risk of depressive symptoms. Increases concentration and reaction. |

[17,19,20,27,32]. | |

| Control smoking | Decreases the risk of developing cardiometabolic disease, brain injuries and improves sleep. Increases the feeling of pleasure and reward. | [14,28]. | |

| Control alcohol/drug consumption | It reduces the risk of cardiovascular diseases, increases brain activity and favors the optimization of the sleep-wake cycle and reduces emotional problems. | [27]. | |

| Promote mental health | Promotes improvement of emotional control, cognitive and physical performance. Encouraging the practice of Mindfulness increases concentration, occupational safety and prevents stress, symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder feelings of anxiety and loneliness. |

[17,23,29,31]. | |

| Prevent Sexually Transmitted Infection (STI) | Providing health education to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted infection, HIV/AIDS and cancer. | [14,32,33]. | |

| Environmental | Promote rest with the expansion of the places of stop and rest | Decreases the risk of fatigue, pain, accidents, drowsiness, stress, symptoms of depression, overweight. Increases safety at work and sleep quality. Prevention of the risk of cardiometabolic diseases, obesity and cancer. Reduces social isolation, stress, increases well-being. |

[14,22,23,34]. |

| Health education to prevent mechanical injuries | Promotes health, management of injuries more effectively and the appropriate development of the care plan. |

[15]. | |

| Reorganize the work day | Sharing responsibilities with a co-pilot colleague - decreases the driver’s loneliness, promotes free time to plan the achievement of new goals, increases job satisfaction and well-being.Lower number of hours at the wheel - contributes to the reduction of cardiometabolic diseases, increases occupational safety, reduces the level of stress and depression.Reducing long journeys increases the time available for family life, reduces the risk of illness and death. | [16,27,34]. | |

| Promote access to health care services | It prevents chronic diseases, increases productivity, prevents depressive symptoms and improves quality of life. | [14,19,27,32]. | |

| Promote access to essential medications for the control of NCD | Decreases the risk of premature death. Increase occupational safety, concentration and reduce mood swings. | [21,31]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).