1. Introduction

Resilience is often described as the ability to anticipate, adapt, and recover from adversity [

1] incorporating climate adaptation, responsible use of resources, healthy and inclusive environments, and participation [

2] enabling people to plan their environment as best suited for their needs. Other definitions claim that resilient systems have the capacity to adapt and evolve following disturbances, resulting in a state that differs from the condition prior to the disruption, which ensures the preservation of essential functions and the restoration of distinctive structures [

3]. Some authors highlight the importance of collective knowledge, digital citizen participation or crowdsourcing and efficient emergency response mechanisms as a tool for enhancing urban resilience [

4]. The notion of community is also considered as a valuable social structure in the context of achieving resilience, as it functions best in the context of “collectivist, small scale societies … living in harmony with their environments” [

5] which may well be attributed to a mid-war European example of Cvjetno housing estate. These theoretical perspectives can be evaluated through concrete case studies, such as the Cvjetno housing estate, to understand resilience in practice.

Cvjetno housing estate is often referred to as a unique and highly valuable mid-war example of a well-planned settlement based on the principles of CIAM (

Congrès internationaux d’architecture modern). It is protected as a cultural and historical complex listed in the Register of Cultural Property of the Republic of Croatia [

6,

7]. Consequently, it has been extensively studied in numerous academic publications [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. However, there is limited research focusing on the concept of resilience at this protected site, which could provide insights into the various dimensions of resilience, including resilience to natural disasters, financial and economic resilience, and social resilience. The concept of resilience is closely related to the other concepts such as sustainability, degrowth theory and cradle-to-cradle strategies which propose and encourage a green, caring, and communal economy [

19,

20].

2. Materials and Methods

The research delves into an analysis of the historical context and physical characteristics of Cvjetno estate, drawing insights from archival documents, historical records, and previous studies. Primary data sources comprised archival documents sourced from the National Archives in Zagreb, encompassing planning and construction records of Cvjetno housing estate, including architectural plans, construction documentation, and correspondence. Additionally, valuable visual insights were derived from historic photographs obtained from the Zagreb City Museum.

To augment the archival data, field research was conducted to evaluate the contemporary state of the estate and its buildings. This entailed on-site observations focused on the street facades of houses, facilitating a comparison between the current condition and the original plans and projects.

The study examines the concept of resilience in scientific literature and draws new insights using Cvjetno estate as an example of mid-war architecture and planning. The research particularly examines its planned resilience to natural hazards such as flooding from the nearby river Sava and seismic risks due to its location in a seismically active area. By analyzing past instances of flooding and earthquakes in Zagreb, the research evaluates the estate’s adaptive capacity and its role in mitigating risks to residents.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Natural Hazards as Context for Establishing Resilient Communities

Considering the challenges in our real environment closely linked to climate change, natural hazards, economic uncertainty, and social crises, planning procedures should aim to incorporate the concept of resilient communities, which could provide the appropriate framework for ensuring future spaces of quality living.

In the context of resilient communities, the Cvjetno housing estate serves as a notable example, particularly due to its location just 300 meters from the south-flowing river Sava. This proximity underscores the importance of addressing natural hazards, including not only flooding but also the risk of earthquakes, in Zagreb. The river Sava has a history of flooding the southern parts of Zagreb with the first recorded flooding occurring in the 1890s when the river overflowed into the Trnje district up to Vukovarska Street on the north. Subsequently, the river flooded five more times between 1923 and 1936 (in 1923, 1925, 1930, 1933, and 1936), solidifying its reputation as a significant natural threat [

21]. Efforts to protect the area from flooding began in the late 19th century with the first regulations of the Sava River and continued into the mid-war period with the partial construction of the Sava embankment [

22,

23].

The most extensive flooding in Zagreb happened in late October 1964 when the river surged beyond its banks, inflicting substantial damage to the embankment along the Sava River. Consequently, a portion of the embankment suffered partial destruction, leading to the inundation of over 6,000 hectares of the city [

22]. This flooded area encompassed approximately one-third of all residential apartments in Zagreb and was home to as many as 180,000 people. It was after the flood of 1964 that the extension of the embankment was built, along with an efficient flood defense system for the wider Zagreb area [

21,

24].

However, floods are not the sole natural hazards posing a threat to the city of Zagreb. Situated in a region prone to earthquakes due to its location in a seismically active area, the City of Zagreb is encompassed by multiple epicentral areas renowned for seismic activity, with the most notable being the Medvednica epicentral area, just north of the city. The second-to-last significant earthquake struck on November 9th, 1880, registering a magnitude of 6.3 on the Richter scale. During this event, two fatalities were recorded, with 29 individuals sustaining serious injuries. Additionally, a total of 3,830 residential and commercial buildings were damaged, with churches bearing the brunt of the destruction. Alongside churches and chapels, numerous large state buildings were also affected. In total, 1,758 houses in Zagreb were damaged during the earthquake, excluding those whose damages were not formally reported to the expert commission [

25].

The most recent significant earthquake, registering a magnitude of 5.5 on the Richter scale, struck on March 22nd, 2020. It was succeeded by 1,650 aftershocks within a span of two months, the most powerful of which measured 4.9 in magnitude. This seismic event resulted from a significant displacement along the primary fault line, triggering the intricate network of faults in the northeastern part of Zagreb. The earthquake was so intense that its effects were felt within a radius of 1,000 kilometers. Resulting in one fatality and damaging over 25,000 buildings, the earthquake’s toll could have been higher if not for strict pandemic measures enforced just days earlier, compelling nearly all citizens to remain indoors. The most damage was caused in the oldest parts of the city – the Upper and Lower City, as well as the areas north and east from the city center [26]. Trnje district suffered relatively minor damage, and there were no significant reports of damage in the Cvjetno estate (

Figure 1).

3.2. The Concept of Resilient Communities and Its Characteristics

Resilient communities possess the capacity to resist, absorb, adapt to, and recover from the effects of hazards swiftly and efficiently. This entails being flexible, robust, interconnected, independent, and inclusive [

28,

29]. Accordingly, a resilient community should foster persistence and sustainability in social, economic, and ecological dimensions through thoughtful planning and design, while considering future community needs and quality of life amidst multiple crises arising from natural disasters, climate change, and socio-economic shifts.

The social fabric conducive to such communities could be founded on the concept of community envisioned as "local loops" and "empathetic communities" [

30], wherein most of the population’s needs are fulfilled within the community itself. This entails the shared and responsible utilization of local resources, energy autonomy, and reduced dependence on global production and distribution networks. It involves robust local supply chains and proximity to social, health, economic, cultural, and public facilities, ultimately fostering community resilience in the face of crises stemming from socio-economic and climate-ecological changes.

Drawing from the analysis of four case studies, Wang et al. identify eight key characteristics of resilient urban communities: 1. Multifunctionality of space; 2. Adaptability of spatial processes; 3. Interactive facilities; 4. Diverse components; 5. Intelligence of public services; 6. Human-centricity of public services; 7. Predictive management concepts and 8. Collaborative governance. These characteristics can be grouped into two categories based on their systemic qualities. The first group encompasses multifunctionality, adaptability, interactivity, and diversity, which are inherent features facilitating the system’s operation during non-crisis periods. The second group involves adaptive qualities of urban communities such as intelligence, human-centricity, predictiveness, and collaboration, which contribute to resilience during crises [

31].

3.3. The Urbanization of Trnje and the Origins of Cvjetno Housing Estate

Cvjetno housing estate – described as “the greatest accomplishment of Croatian urban planning in the interwar period” [

18] (p. 279) – is situated in Trnje, a district located south of Zagreb’s city center, bordered by the railway to the north and the river Sava to the south. During the construction of Cvjetno estate, this area on the periphery of Zagreb experienced frequent flooding and was characterized by small to medium-sized industries, along with unplanned houses resulting from "wild" construction. Croatian writer Miroslav Krleža vividly described Trnje in 1937: “[…] instead of the facade of the city being built over the mirror of the river, there in the middle is all the misery and all the stench and poverty. It’s still here: Trnje…” [

32].

The urbanization and industrialization of the Trnje area began in the second half of the 19th century with the construction of industrial complexes like “Paromiln”, and the first planned workers’ settlement in Zagreb, Strojarničko estate. During the mid-war period Zagreb, like many cities, faced a housing crisis, leading to intensified construction in Trnje with the development of additional industrial facilities and housing complexes to accommodate the growing workforce.

In the early 1930’s, an international competition for Zagreb’s extension identified Trnje as an area of great urban potential [

11,

14,

33,

34,

35,

36,

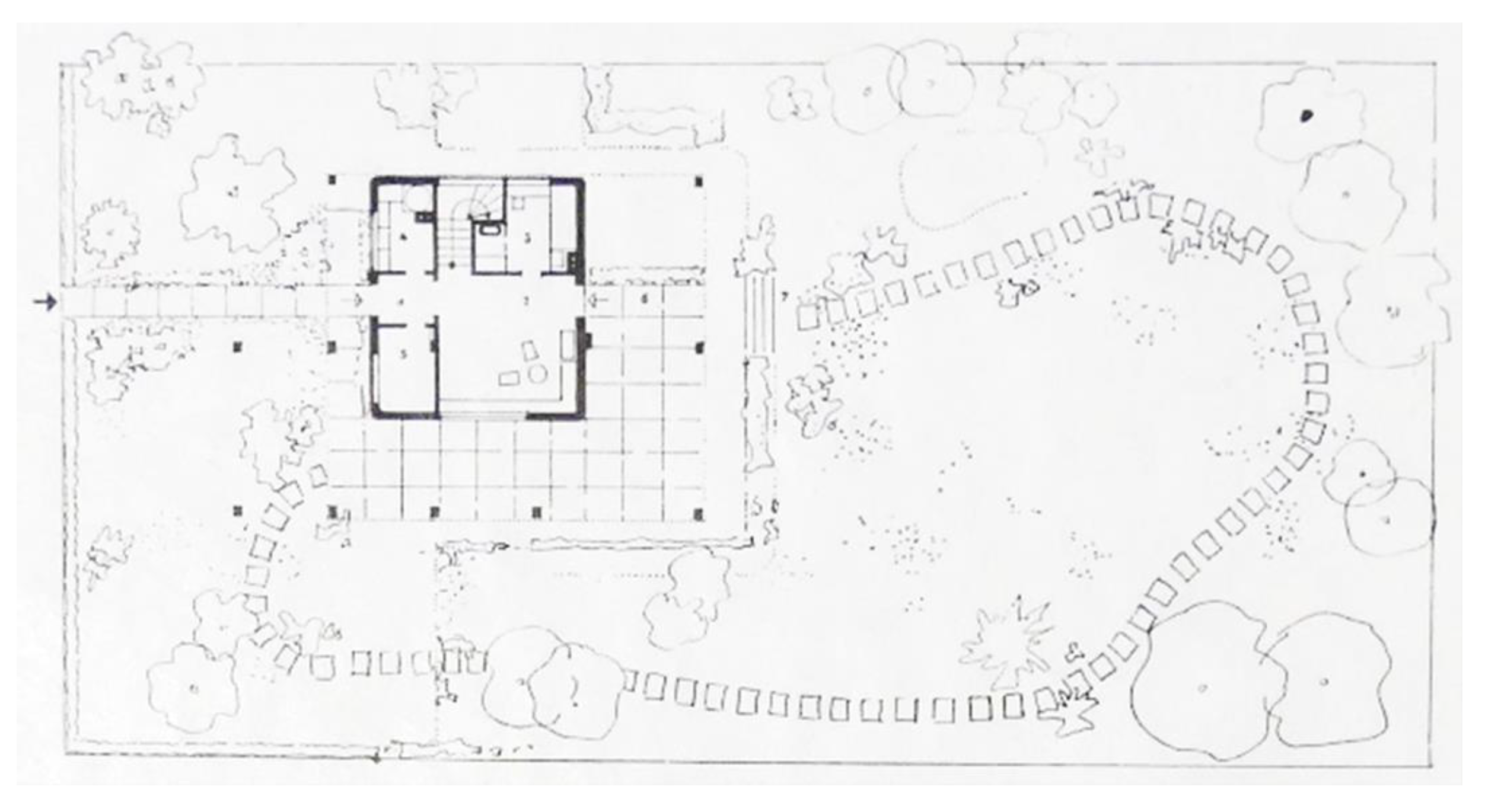

37], leading the way for new planned construction. In 1939, Croatian urban planner and architect, Vladimir Antolić planned the construction of Cvjetno housing estate in the southwest corner of Trnje area (

Figure 2). The estate was intended for city officials lacking building capital, therefore it was the architect’s objective to find a way to address all related financial matters, including “loan supply, building costs and payment of loan” [38]. The city officials were then able to acquire homes through loans that they paid off monthly over the course of 10 years. The loan rate was approximately equivalent to one-third of an official’s salary [

38].

The estate (

Figure 3) covers a surface area of 0.10 km2 and is situated north of the river Sava and its embankment, with its southern edge on Prisavlje Street, northern along Zagreb Avenue, eastern boundary along Cvjetno naselje IV Street, and western boundary along Cvjetna and Odranska Street. The orthogonal plan of the site adheres to the CIAM principles, ensuring adequate sunlight, living space and greenery in individual parcels. The ties between CIAM and Antolić were very close as Antolić was a member of the national CIAM group for Yugoslavia – Work Group Zagreb and contributed to preparing the materials for the 4th CIAM congress in Athens, “The Functional City” [

39,

40].

Antolić collaborated with another member of the Work Group Zagreb, architect and structural engineer Zvonimir Kavurić, to design four types of houses. The main distinction among the types was the number of floors and inhabitable surface area. There were three two-story types with 95, 110 and 140 m2 (A 95, A 110, A 140); and one three-story type of 170 m2 (B 140) [

14,

18,

38,

42].

The estate was designed as an “independent unit” [

38] (p: 2) with four north-to-south residential streets – now known as Cvjetno naselje I, II, III, IV – connected by a west-to-east pedestrian street with greenery running approximately through the middle of the estate (now Vladimir Antolić Alee). In addition to the residential area, Antolić planed social and public areas around the estate. On the western side, from north to south, he planned a playground, school, and a school playground, while on the eastern side, he designated a market and public buildings (

Figure 4). The estate was intended to accommodate 70 family houses, described as “modern pile dwellings” on reinforced concrete columns [

38], situated on elongated east-to-west rectangular parcels 20 X 40 meters on both sides of the streets.

The housing units were set back 8 meters from the street border, providing a relatively large front garden area with lawns, bushes, uniform hedges, and fences. They were positioned 3 meters from the northern border of the parcel and 7 meters from the southern border, maximizing the sunny space of the parcel. Each house featured a spacious backyard with an orchard, vegetable garden and lawns as shown on

Figure 5 [

38].

The ground floor of the units was designated for auxiliary rooms, and the upper floor(s) served as residential living areas with bedrooms, kitchens, living rooms, and bathrooms ensuring habitability even during floods. The treatment of certain exterior elements, such as the roof with a mild slope and concrete columns, were determined by a regulation [

14,

18,

38], and these became characteristic elements of the settlement that contribute significantly to its identity.

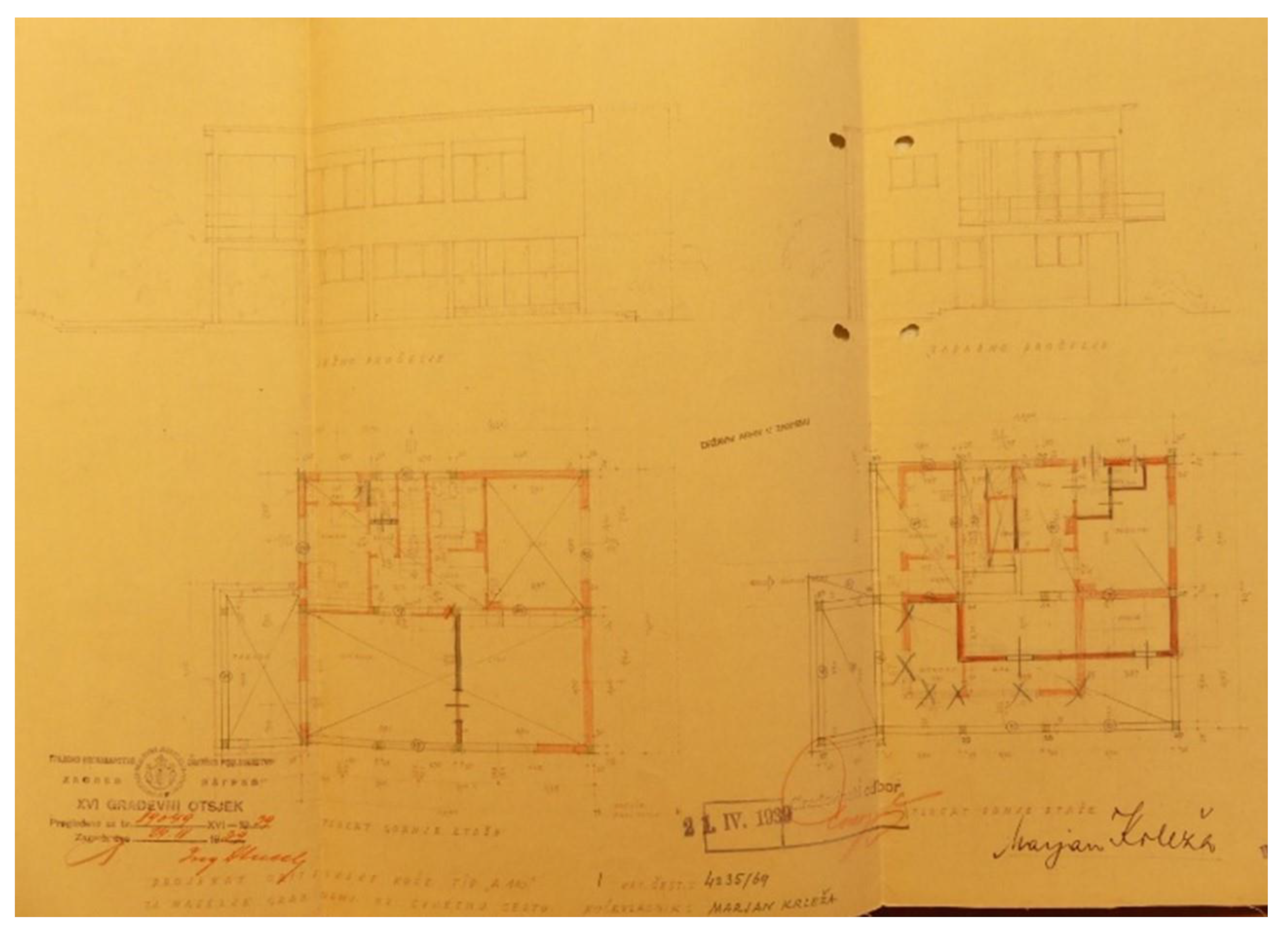

As mentioned earlier, four types of houses were designed for the estate. All houses had a reinforced concrete frame with brick filling and a sloped roof. For example, Type A 95 featured auxiliary rooms on the ground floor, and a kitchen, bathroom, living room and two bedrooms on the first floor. Type A 110 (

Figure 6 and

Figure 7) included a large porch and an additional workroom on the ground floor, with a kitchen, bathroom, living room and three bedrooms on the first floor. Type A 140 had an additional living room on the ground floor, along with a kitchen, two bathrooms, living room and three bedrooms on the first floor. The three-storied B 140 type had a large porch and a living room along with auxiliary rooms on the ground floor, and two upper floors with identical floor plans, each featuring three bedrooms, a bathroom, living room and kitchen [

12,

14,

18] (pp. 279-280).

Construction on the Cvjetno estate begun in 1939, with approximately 40 houses completed by 1940, according to Antolić [

38]. Interestingly, this early phase of development saw the first modifications to the plan and specific building projects, as prompted by the future inhabitants. Antolić himself attributed these changes to "exceptional circumstances and misunderstandings among certain plot owners" [

38]: 1). Notably, future residents largely disregarded the regulation specifying the gently sloped design of the roofs, leading to what Antolić described as a "chaotic appearance" in parts of the settlement [

38]. Originally, the plan called for a total of 70 houses arranged along four streets in six north-south rows, with additional four houses situated on the westernmost part of the estate. Each of the six rows comprised 11 houses, with six to the north of Josip Antolić Alee and five to the south, summing to a total of 66 houses. However, during the site’s development, an extra row of houses and parcels was added to the north.

As previously mentioned, in addition to the residential zone, Antolić designated spaces for public and social use on both the western and eastern sides of the estate. The only structure intended for public use that was constructed is the Primary School, designed by Croatian architect Zlatko Neumann and built from 1957 to 1962 [

44]. Positioned in accordance with Antolić’s plan on the western section of the estate, the school was, however, situated slightly farther south than originally envisioned. The market and public buildings to the east were never constructed, and instead, residential buildings now occupy that space.

3.4. Cvjetno Housing Estate as a Resilient Community

Cvjetno housing estate stands as a testament to the principles of CIAM and anticipates some features of a resilient community long before the concept emerged in contemporary discourse. Situated in Trnje, a district historically disrupted by flooding and socio-economic challenges, Cvjetno estate was planned to mitigate these risks and foster resilience in its residents. Trnje, once characterized by industrial complexes and unplanned housing, underwent urbanization and industrialization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Facing a housing crisis during the mid-war period, Zagreb witnessed intensified construction in Trnje, leading to the development of Cvjetno housing estate. Planned by architect Vladimir Antolić in 1939, the estate acknowledges the risk of flooding and earthquakes in its planning. Antolić’s design incorporates elements such as raised housing units on reinforced concrete columns, spacious front and backyards, and a pedestrian street with greenery, ensuring habitability during floods and promoting community cohesion. The estate aimed to provide affordable homes for city officials, incorporating innovative financial plans to facilitate ownership. The estate’s design adheres to CIAM principles, ensuring ample sunlight, living space, and greenery.

The estate’s diverse housing types cater to varying family sizes and needs, reflecting the principle of adaptability. From two-story houses to three-story dwellings, each unit offers functional living spaces designed to accommodate different needs. Additionally, the planned inclusion of social and public areas, such as playgrounds, schools, markets, and public buildings, fosters community resilience by providing essential services within walking distance and promoting social interaction. While some intended public spaces were never built, the primary school constructed according to Antolić’s plan remains a vital hub for community activities.

Each house included spacious front and back gardens, promoting self-sufficiency, and enhancing community resilience. Located relatively close to the river Sava, Cvjetno estate faced the constant threat of flooding. Efforts to mitigate this risk began in the late 19th century, culminating in the construction of the Sava embankment and an efficient flood defense system after the devastating flood of 1964. Furthermore, situated in a seismically active area, the estate was designed to withstand earthquakes, ensuring the safety of its residents. The estate was planned as an "independent unit," fostering socio-economic stability within the community.

Drawing the characteristics of resilient communities from Wang et al. [31] Cvjetno estate benefits from multifunctionality and flexibility of space on the scale of the estate and particular parcels. The estate features a residential area, along with public spaces of greenery and a primary school. Although the multiple social functions of the estate were not built, the developed spaces are flexible and adaptable, and can welcome various types of functions. It also has the characteristic of a human-centered approach. The planned settlement was to have all the necessary buildings for social purposes within walking distance. On top of that, as the modern design of Antolić’s houses was not accepted by some future residents, they were able to modify the design to suite their aesthetic preferences. The estate also includes the characteristic of prediction in the structural design of specific house types that accept and are prepared for natural hazards such as floods and earthquakes.

4. Conclusions

The concept of resilient communities emphasizes their ability to withstand, absorb, adapt to, and recover from various hazards efficiently and effectively. This capacity is characterized by traits such as flexibility, robustness, interconnectedness, independence, and inclusivity. Resilient communities aim to ensure persistence and sustainability across social, economic, and ecological dimensions, even amidst crises arising from natural disasters, climate change, or socio-economic shifts. Resilient communities often rely on local resources, energy autonomy, and reduced dependence on global production and distribution networks. They foster robust local supply chains and proximity to essential facilities, enabling them to withstand and recover from crises.

The Cvjetno housing estate in Zagreb exemplifies resilience in various aspects. Situated in the Trnje district, which historically faced frequent flooding and socio-economic challenges, Cvjetno estate was meticulously planned to mitigate these risks. Its orthogonal design adheres to CIAM principles, ensuring adequate sunlight, living space, and greenery in individual parcels. The estate’s layout includes spacious front and back gardens, orchards, and vegetable gardens, providing residents with self-sufficiency in food production and contributing to the community’s resilience by enhancing food security.

Furthermore, the financial plan devised by architect Vladimir Antolić enabled city officials to acquire homes through loans, fostering socio-economic stability within the community. The estate’s design, with reinforced concrete structures, “modern pile dwellings” with sloped roofs, aimed to withstand floods and other natural hazards. Despite modifications during construction, such as deviations from the original plan regarding the number, design and layout of houses, the estate retained its resilience features.

Although some intended public spaces like markets were never built, the primary school constructed according to Antolić’s plan and Neumann’s design serves as a hub for community activities. Thus, Cvjetno housing estate exemplifies resilience through its thoughtful planning, self-sufficiency features, socio-economic stability, and adaptability to environmental challenges, making it a significant achievement in Croatian urban planning as it demonstrates the enduring relevance of modern urban planning principles in contemporary resilience discourse.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets available on request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- M. Ramsgaard Thomsen and M. Tamke, “Preface,” in Design for Resilient Communities - Proceedings of the UIA World Congress of Architects Copenhagen 2023, A. Rubbo, J. Du, M. Ramsgaard Thomsen and M. Tamke, Eds., Springer, 2023, pp. xi-xvi.

- Rubbo, J. Du, M. Ramsgaard Thomsen and M. Tamke, Eds., Design for Resilient Communities - Proceedings of the UIA World Congress of Architects Copenhagen 2023, Springer, 2023.

- Palermo, L. Chieffallo and S. Virgilio, “Re-generate resilience to deal with climate change. A data-driven pathway for a liveable, efficient and safe city,” TeMA - Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, Special Issue, vol. 1, no. 2024, pp. 11-28, 2024.

- R. Pérez-Arévalo, J. Jiménez-Caldera, J. L. Serrano-Montes, J. Rodrigo-Comino, K. Therán-Nieto, Caballero-Calvo and Andrés, "Enhancing Urban Resilience: Strategic Management and Action Plans for Cyclonic Events through Socially Constructed Risk Processes," Urban Science, vol. 8, no. 43, 2024.

- D. Walters, Designing Community. Charrettes, Masterplans and Form-based Codes, Oxford: Elsevier, 2007.

- ***, "Kulturno - povijesna cjelina Cvjetno naselje," 2004. [Online]. Available: https://registar.kulturnadobra.hr/#/details/Z-1543.

- Ministarstvo kulture, "Izvod iz Registra kulturnih dobara Republike Hrvatske br. 4/2002 - Lista zaštićenih kulturnih dobara," 2004. [Online]. Available: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/2004_08_111_2128.html.

- T. Premerl, "O prostorno-urbanističkom razvoju Zagreba," Arhitektura, vol. XXIV, no. 107-108, pp. 110-115, 1970.

- T. Premerl, "CIAM i naša međuratna arhitektura," Arhitektura, Vols. XXXVII - XXXVIII, no. 189-195, pp. 50-53, 1984.

- T. Premerl, Hrvatska moderna arhitektura između dva rata, Zagreb: Nakladni zavod Matice Hrvatske, 1990.

- D. Radović Mahečić, "Socijalno stanovanje međuratnog Zagreba," Radovi Instituta za povijest umjetnosti, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 141-155, 1993.

- D. Radović Mahečić, "Šutljiva zagrebačka arhitektura," Čovjek i prostor, vol. XXXXI, no. 5-6, pp. 20-25, 1994.

- D. Radović Mahečić, Socijalno stanovanje međuratnog Zagreba, Zagreb: Horetzky, 2002.

- D. Radović Mahečić, “Činovničko stambeno naselje - Cvjetno naselje,” in Moderna arhitektura u Hrvatskoj 1930-ih, D. Radović Mahečić, Ed., Zagreb, Institut za povijest umjetnosti & Školska knjiga, 2007, pp. 441-446.

- Mlinar and M. Trošić, “Parkovi zagrebačkih stambenih naselja izgrađenih između dva svjetska rata,” Prostor : znanstveni časopis za arhitekturu i urbanizam, vol. 12, no. 1, pp. 31-44, 2004.

- E. Blau and I. Rupnik, Project Zagreb: Transition as Condition, Strategy, Practice, Barcelona: Actar D, 2007.

- Maroević, "Cvjetno naselje - put prema nestanku," in O Zagrebu usput i s razlogom. Izbor tekstova o zagrebačkoj arhitekturi i urbanizmu (1970.-2005.), Zagreb, Institut za povijest umjetnosti, 2007, pp. 355-357.

- V. Ivanković, "Arhitekt Vladimir Antolić − zagrebački urbanistički opus između dva svjetska rata," Prostor : znanstveni časopis za arhitekturu i urbanizam, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 268-282, 2009.

- S. J. Coyle, Sustainable and Resilient Communities: A Comprehensive Action Plan for Towns, Cities, and Regions, Chichester: Wiley, 2011.

- G. Kallis, F. Demaria and G. D’Alisa, “Degrowth,” in International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed., vol. 6, J. D. Wright, Ed., Oxford, Elsevier, 2015, pp. 24-30.

- T. Anić, “Društvena povijest Trnja u prvoj polovini dvadesetog stoljeća,” in Trnje - prostor i ljudi, K. Strukić, Ed., Zagreb, Muzej grada Zagreba, 2020, pp. 85-108.

- Marušić, “Stručni prikaz: 55 godina od katastrofalne poplave Zagreba krajem listopada 1964.,” Hrvatske vode, vol. 27, no. 110, pp. 347-354, 2019.

- Marušić, “Iz povijesti vodnog gospodarstva: Studija regulacije i uređenja rijeke Save,” Hrvatske vode, vol. 30, no. 121, pp. 255-259, 2022.

- N. Šimetin Šegvić and I. Šute, ""Pola grada pod vodom". Zbrinjavanje stradalih od poplave u Zagrebu 1964. godine, te plan za daljnju obnovu," Ekonomska i ekohistorija, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 66-82, 2021.

- ***, "Procjena rizika od velikih nesreća za područje Grada Zagreba," Gradska skupština Grada Zagreba, Zagreb, 2019.

- T. Bonevska, M. Grlić, M. Horvat, L. Miholić and I. Martinić, "Zagrebački potres 22. ožujka 2020.," Geografski horizont, vol. 66, no. 2, pp. 21-32, 2020.

- ***, "ARIA Damage Proxy Map," 2020. [Online]. Available: https://maps.disasters.nasa.gov/arcgis/home/webmap/viewer.html?layers=db20d487cee24810bd7b8cc96ccbcf3b.

- UN HABITAT, Trends in Urban Resilience, 2017.

- E. Braì, G. Mangialardi and D. Scarpelli, "Circular living. A resilient housing proposal," Tema. Journal of Land Use, Mobility and Environment, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 447-469, 2022.

- SPREAD 2050, Scenarios for Sustainable Lifestyles 2050: From Global Champions to Local Loops, 2012.

- Y.-c. Wang, J.-k. Shen, W.-n. Xiang and J.-Q. Wang, "Identifying characteristics of resilient urban communities through a case study method," Journal of Urban Management, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 141-151, 2018.

- Doklestić, "Grad na Savi," in Zagrebačke urbanističke promenade, Zagreb, Dominović d.o.o., 2010, p. 161.

- T. Jukić, I. Mlinar and M. Smokvina, Zagreb - Stanovanje u gradu i stambena naselja, Zagreb: Sveučilište u Zagrebu, Arhitektonski fakultet, Zavod za urbanizam, prostorno planiranje i pejsažnu arhitekturu ; Grad Zagreb, Gradski ured za strategijsko planiranje i razvoj Grada, 2011.

- Mlinar, "Urbanizacija i arhitektura Trnja," in Trnje - prostor i ljudi, K. Strukić, Ed., Zagreb, Muzej grada Zagreba, 2020a, pp. 42-64.

- Mlinar, "Urbanističko-arhitektonski leksikon Trnja," in Trnje - prostor i ljudi, K. Strukić, Ed., Zagreb, Muzej grada Zagreba, 2020b, pp. 133-158.

- Strukić, "Kvartovske priče iz Trnja," in Trnje - prostor i ljudi, K. Strukić, Ed., Zagreb, Muzej grada Zagreba, 2020, pp. 11-41.

- Podnar, "Identity Reevaluation of a Place on the Example of Cvjetno Naselje in Zagreb," Defining the Architectural Space - Avant-garde Architecture, vol. 4, pp. 69-80, 2022.

- Antolić, "Cvjetno naselje u Zagrebu," Inženjer, Vols. 3-4, pp. 1-4, 1940.

- ***, "Vlado Antolić," Arhitektura, vol. LI, no. 214, pp. 67-68, 1998.

- T. Bjažić Klarin, "Radna grupa Zagreb - osnutak i javno djelovanje," Prostor : znanstveni časopis za arhitekturu i urbanizam, vol. 13, no. 1, pp. 41-51, 2005.

- ***, "Digitalne zbirke Nacionalne i sveučilišne knjižnice u Zagrebu," [Online]. Available: https://digitalna.nsk.hr/?pr=i&id=574136. [Accessed 29 April 2024].

- Haničar Buljan, "Prilog za biografiju arhitekta Zvonimira Kavurića (1901. - 1944.)," Radovi Instituta za povijest umjetnosti, vol. 30, pp. 281-297, 2006.

- Državni arhiv u Zagrebu, HR-DAZG-1122-620/1.

- Khale, "Architect Zlatko Neumann - Works after the Second World War (1945-1963)," Prostor : znanstveni časopis za arhitekturu i urbanizam, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 172-187, 2016.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).