1. Introduction

Cornea is crucial for the focusing ability of the human eye, contributing to about two-thirds of its optical power. However, serious eye diseases such as keratoconus, corneal ectasia, hyperopia, recurrent corneal erosion, and certain corneal dystrophies directly impair corneal function. To rectify these diseases, it is often needed to locally deliver heat to diseased regions of the cornea through such heat-induced refractive therapies as thermokeratoplasty [

1,

2,

3] and photorefractive keratectomy [

4,

5]. Thermal treatments reshape the cornea’s curvature and enhance tissue stability by inducing collagen contraction and new cross-linking bonds, which reorganize the collagen fibers into a more stable structure, thereby correcting refractive errors and improving the cornea’s optical properties. These advanced surgeries, including laser-based refractive interventions, heavily depend on comprehensive sensing of the cornea’s mechanical and optical properties at elevated temperatures relevant for these therapies [

6,

7,

8].

From a materials science perspective, the cornea is an organic composite material, with its stroma predominantly composed of densely arranged collagen. Collagen undergoes a thermally triggered phase change from its triple helical structure to a random coil configuration, a transformation that is intimately linked to tissue contraction [

9]. Observed phase change from the random coil state to a gel-like condition is often referred to as hyalinization [

10]. This process is believed to involve the breaking of covalent or peptide bonds within the collagen molecules. The hyalinized state is thought to be connected with the stress relaxation of the contracted corneal tissue [

11].

Historically, the analysis of collagen denaturation has relied on bulk analytical methods, such as differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) [

12,

13]. Due to the challenges in performing localized thermal measurements and minimizing the material volume analyzed, microthermal local analysis is achieved by

contact-based thermally controlled atomic force microscopy [

14]. However, the technique is invasive and lacks sensitivity, failing to produce signals at

< 60°C. To probe biomechanics

non-invasively, a Brillouin light scattering (BLS) spectroscopic sensing via detection of inelastically scattered light from thermal hypersonic acoustic waves propagating in the probed biological media, is typically employed [

15,

16,

17,

18], including non-contact monitoring heating-induced phase transitions in globular proteins [

18] and flesh tissues [

15].

Using BLS microscopy, the corneal biomechanics was thoroughly studied earlier, but at ambient (room temperature) conditions [

19], elucidating critical aspects of biomechanical properties of healthy and keratoconus affected cornea tissues [

20,

21], including their depth-dependent mechanical properties and the impact of various corneal cross-linking (CXL) protocols on enhancing corneal stiffness [

22,

23]. Notably, their investigations revealed significantly lower measured Brillouin shifts in keratoconic corneas compared to healthy ones, indicating a lower elastic modulus and, by extension, decreased biomechanical stability [

22]. The efficacy of CXL treatments by BLS has provided valuable insights into the biomechanical reinforcement these treatments offer, especially in the anterior portion of the cornea [

23].

Our current study focuses on non-invasive optical biosensing of the ovine cornea across heat-driven phase transitions via monitoring its temperature-dependent GHz viscoelastic properties using BLS spectroscopy, which have never been explored before on corneal tissues. This research direction is critical for a deeper understanding of how temperature variations impact corneal biomechanics. Insights gained from this study are poised to influence the development and refinement of therapeutic interventions such as thermokeratoplasty and laser-assisted procedures, which depend on precise thermal modulation of corneal tissues. We also explore how heat-driven phase transitions in cornea affect such mechanical properties as hypersonic velocity and attenuation, compressibility, complex longitudinal modulus and apparent viscosity.

Central to this study is the utilization of Brillouin light scattering (BLS) spectroscopy as a biosensing technique that enables non-invasive, real-time assessment of biomechanical properties at a microscopic level. BLS spectroscopy stands out for its unique ability to detect subtle mechanical changes within biological tissues under various physiological and pathological conditions. Unlike traditional biomechanical testing methods, which often require tissue deformation or destruction, Brillouin spectroscopy provides a contactless alternative that preserves tissue integrity. This feature is particularly advantageous in ophthalmic applications where minimal disruption is crucial. The sensitivity of BLS to changes in mechanical properties at different temperatures makes it an ideal tool for monitoring the dynamic viscoelastic behavior of the cornea during thermal treatments. By integrating BLS into our study, we aim to advance the field of corneal biosensing, offering a sophisticated technique that enhances our understanding of tissue mechanics and aids in the development of targeted, efficacious therapeutic interventions.

2. Materials and Methods

This section provides a comprehensive overview of the materials, the Brillouin elastic modulus, the cornea samples utilized, and the experimental setup employed in this study.

2.1. Brillouin Elastic Modulus

BLS spectroscopy is an optical analytical technique that probes inelastic light scattering from thermal acoustic waves within interrogated medium. In the context of a 180° backscattering arrangement as implemented in this research, by applying the principles of energy and momentum conservation to the scattering process, it is revealed that the relationship between the hypersound velocity, denoted as

, and the frequency shift of the incoming light, denoted as

, is given by the following equation:

Here, represents the wavelength of the incident light, and stands for the refractive index of the medium through which the light travels.

The longitudinal kinematic viscosity can be described as the sum of its shear and bulk viscosity components. Here, the viscosity

η is a combination of shear

and bulk

viscosities. This is connected to the linewidth of the Brillouin scattering peak at half maximum,

, which is a characteristic of the attenuation in acoustic waves propagating through the cornea [

24]:

where

ρ = corneal density,

κ = thermal conductivity, and

γ is the ratio of specific heats at constant pressure and volume. Often, the term involving thermal conductivity is omitted for simplicity, leaving only the viscosity-dependent part in the consideration of corneal mechanics [

25]. Then the viscosity

η, which is crucial for the cornea’s biomechanical behavior especially in response to intraocular pressure changes and external forces, is determined by:

where the linewidth

is linked to the hypersound (viscous) dissipation due to thermal density fluctuations within the corneal tissue, serving as an indicator of the cornea’s viscoelastic properties and its health [

26].

The complex modulus of a material, also known as the complex longitudinal modulus, is tied to the frequency shift and linewidth, expressed as [

27]:

where

M′ is the storage modulus, which quantifies the elastic energy stored within the material.

M′′, on the other hand, is the loss modulus, indicative of the hypersound energy (viscous) dissipation within the material. These components are calculated based on the hypersound velocity and the apparent viscosity, as detailed in the referenced Equations (1) and (3). For corneal tissue, where the structure is inherently heterogeneous, the Brillouin scattering frequency shifts are typically observed at 5 - 10 GHz [

19,

28], corresponding to an elastic modulus spanning from 2 to 6 GPa. To determine the elastic modulus from the Brillouin shift, one needs to take into account the refractive index-density factor

of the cornea, which can be affected by its non-uniform refractive index and density. These inconsistencies are due to hydration levels [

29,

30] and the concentration of water/protein content [

31,

32] within the corneal tissue. The refractive index,

, can be expressed as a function of corneal hydration, and the

is a sum of the density of the tissue’s dry state and the hydration. Since the changes in

are only 0.3%, a constant average value of 0.57g/cm

3 for

is used in analyses [

19].

The hypersound absorption coefficient, which does not depend on frequency, can also be extracted from measured Brillouin peak frequency shift

and linewidth

through the following relationship [

24]:

This allows us to determine such important mechanical properties as hypersound velocity, apparent viscosity, complex longitudinal modulus, and the sound absorption coefficient.

2.2. Cornea Samples

Whole eyes from approximately 1 year old ten ewes were acquired within 2 to 4 hours postmortem from a local slaughterhouse. These specimens were stored on ice during transportation and prior to experimentation. To enable optical illumination and detection, each whole eye was positioned within a chamber holder and flattened over a plastic dish. Notably, the flattening process did not induce alterations in the mechanical properties of the cornea. This was confirmed through control experiments involving unflattened eyes suspended in a bath of mineral oil [

20]. For the BLS measurements, we opted for silicone oil instead of mineral oil due to its superior temperature stability alongside its neutrality. All experiments were executed within 2 hours of receiving the tissue samples. Brillouin measurements were conducted immediately following the respective treatments, with each sample typically requiring approximately 2 hours for data collection.

2.3. BLS Sensing

For measurement of longitudinal (compressional) acoustic waves in studied samples, the BLS spectra were collected using a 180-degree backscattering configuration as described in [

33]. Incident light of wavelength

= 532 provided by a Coherent Verdi G2 solid-state laser operating in a single longitudinal mode was employed. The laser beam was focused onto the cornea samples using a 20× objective lens of a confocal microscope (Mitutoyo, WD = 20 mm, NA = 0.42), maintaining an average non-invasive optical power of 10 mW incident at the samples. The inelastically Brillouin scattered light from the samples was collected and focused using a high-quality anti-reflection-coated camera lens with a focal length of 5 cm, followed by a 40 cm lens directing the light onto a 150 μm-diameter input pinhole of an actively stabilized 3+3 pass tandem Fabry-Perot interferometer (JRS Scientific Instruments). This interferometer, set to a free spectral range of 20 GHz and a finesse of approximately 100, was used for frequency analysis of scattered light. The light transmitted through the interferometer was further directed onto a 700 μm pinhole and detected by a low-dark count photomultiplier tube (≲ 1 s

−1), which converted it into an electrical signal for subsequent computer storage and display.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Brillouin Spectra of Cornea and Silicone Oil

Direct BLS measurement from dry cornea typically alters its biomechanical property, as it is significantly influenced by the level of hydration in the cornea [

34,

35]. Silicone oil was selected for its known and stable viscoelastic properties across various temperatures and immiscibility to water over studied temperature range [

36,

37]. This strategy enhances the accuracy of detecting specific biomechanical changes within the cornea, especially under temperature variations, by providing a comparative baseline that underscores the importance of hydration in the accurate assessment of tissue biomechanics.

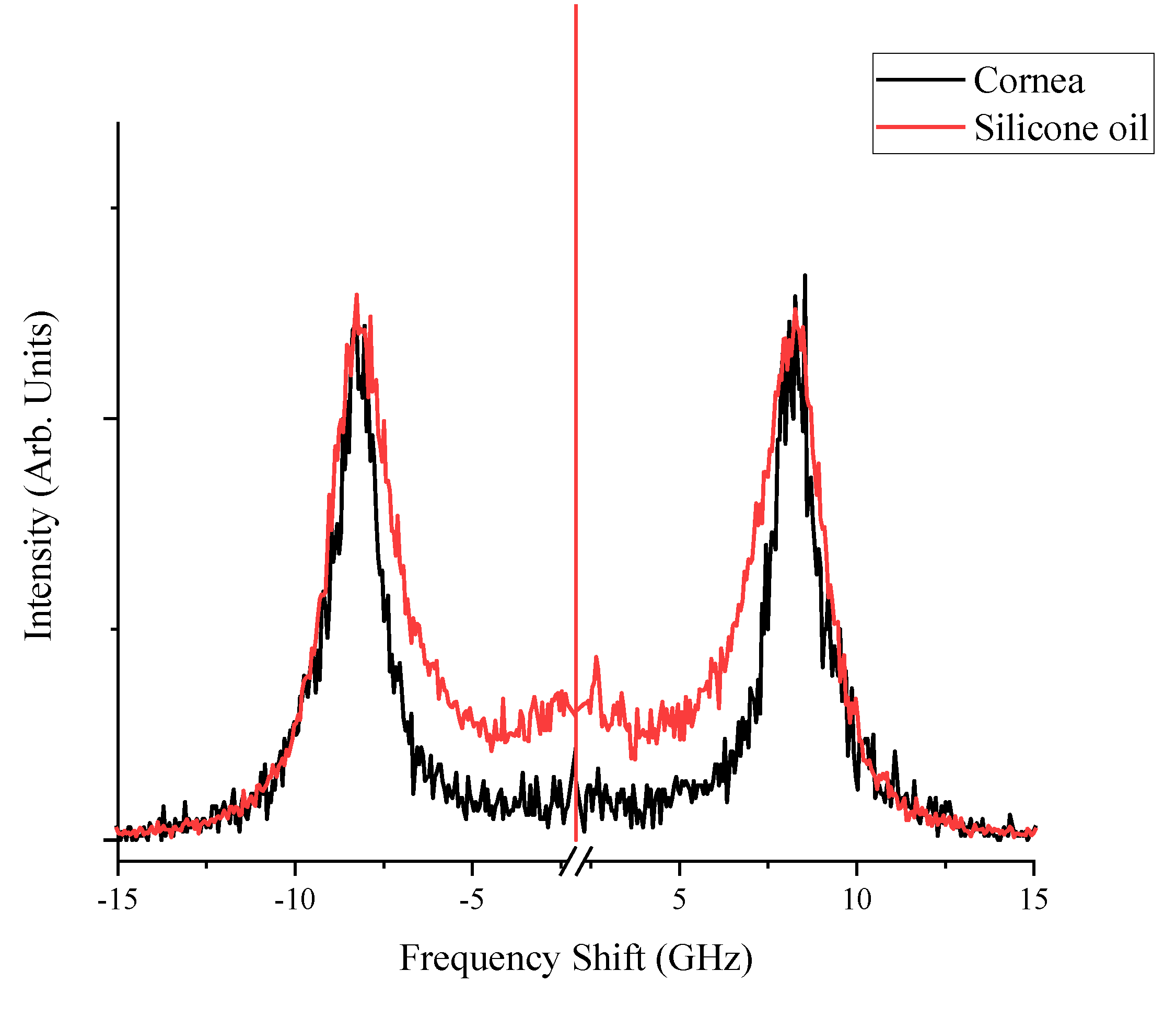

The Brillouin spectra collected at room temperature for corneal tissue and silicone oil, as shown in

Figure 1, exhibit similar peak shifts that are reflective of the intrinsic mechanical properties of each material. The corneal tissue presents peaks approximately at ±8.0 GHz, consistent with its known biomechanical properties, while silicone oil demonstrates a distinct linewidth pattern which is consistent with [

38], evidencing its unique viscous characteristics. During the thermal treatment, the sample was set on a temperature-controlled plate, which was thermally linked to a Peltier device via silver paste (Linkam PE120, Linkam Scientific Instruments, UK). This setup was then positioned on a confocal microscope, allowing for measurements to be conducted throughout the heating process. The temperature of the sample was determined based on the temperature voltage calibration of the Peltier element. The spectra were fitted with multiple Lorentzian functions on the Stokes and anti-Stokes peaks, which yielded peak parameters such as linewidths defined as the full width at half maximum (FWHM), frequency peak positions (Brillouin shifts), and integrated peak intensities. The FWHM values for each complex spectral shape were aggregated to quantify the cumulative linewidths, capturing the behavior of the samples under varying thermal conditions.

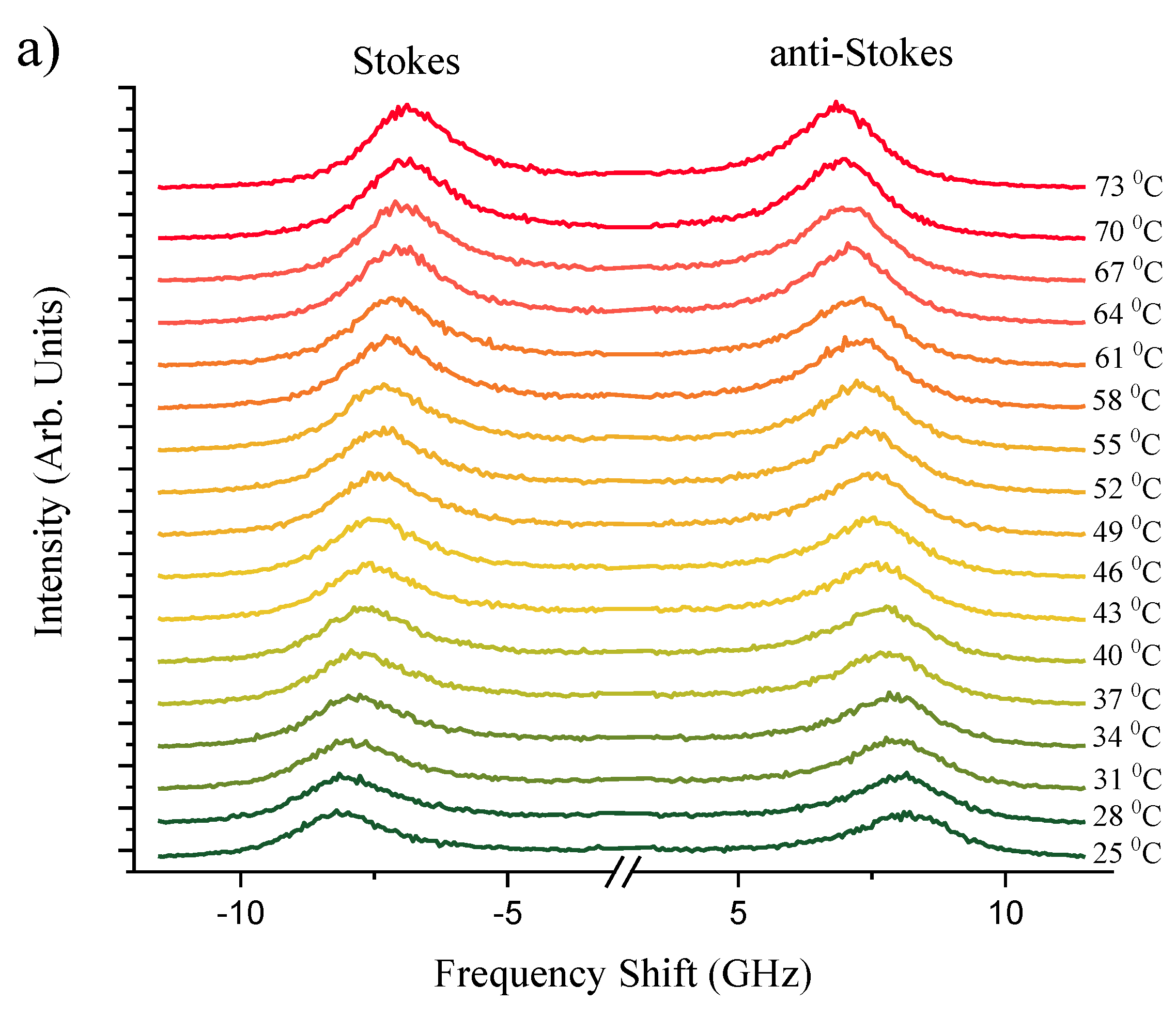

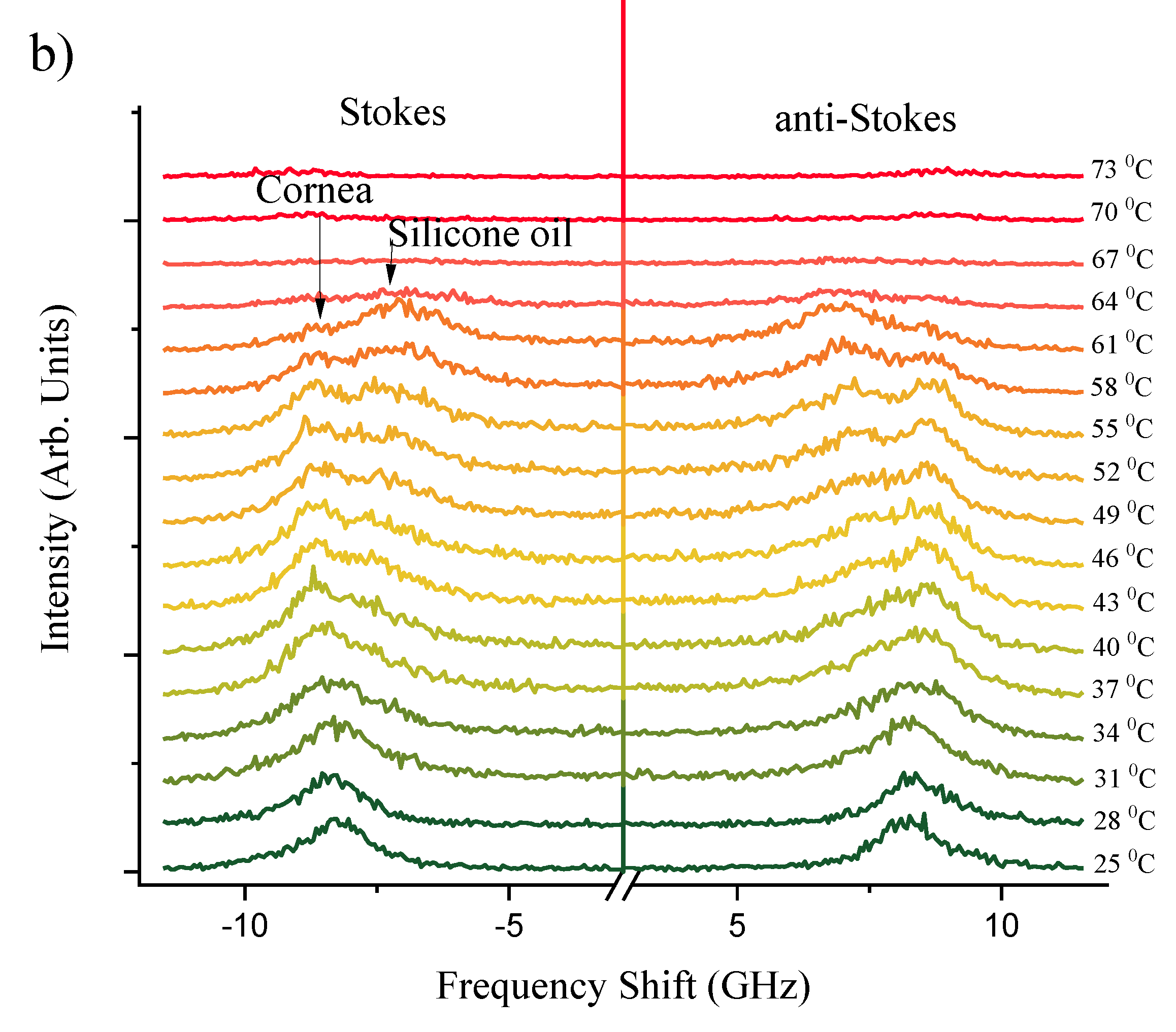

Figure 2a,b present a series of Brillouin spectra of silicone oil and corneal tissue submerged in silicone oil, respectively. This comparison spans a temperature range of

= 25 - 73°C. The distinct spectral splitting of the Brillouin peaks observed for silicone oil and corneal tissue at approximately 40°C suggests the initial thermal destabilization of corneal collagen. This unfolding is in line with findings of Leikina

et al. [

39] that Type I collagen undergoes a thermal transition towards a less ordered state at physiological temperatures. Silicone oil, with its viscosity decreasing at higher temperatures, exhibits a more significant shift in Brillouin frequency, corresponding to the decrease in its longitudinal elastic modulus. The corneal tissue, while also affected, shows a lesser frequency shift due to its greater structural rigidity. However, at

> 63°C, corneal samples become white and opaque, indicative of

protein denaturation [

40], which leads to significant attenuation of the Brillouin scattering and disappearance of peaks at higher temperatures. These observations are clearly indicative of Brillouin spectroscopy sensitivity to biomechanical heat driven structural phase transformations within studied biological corneal tissues.

The separation between the corneal and silicone oil peaks is significant as temperature increases, as previously illustrated in

Figure 1. This distinction at elevated temperatures is crucial; the sole silicon oil acts as a reference, allowing for a clearer identification of the corneal tissue’s spectral signature even as thermal effects become more evident. Understanding this separation is pivotal for distinguishing between the Brillouin shifts of the cornea and the silicone oil, which may converge under different experimental conditions. The ability to differentiate between these two materials is of particular importance in high-temperature environments, where the physical properties of the cornea may undergo changes, and the presence of silicone oil can protect and maintain the cornea’s structure.

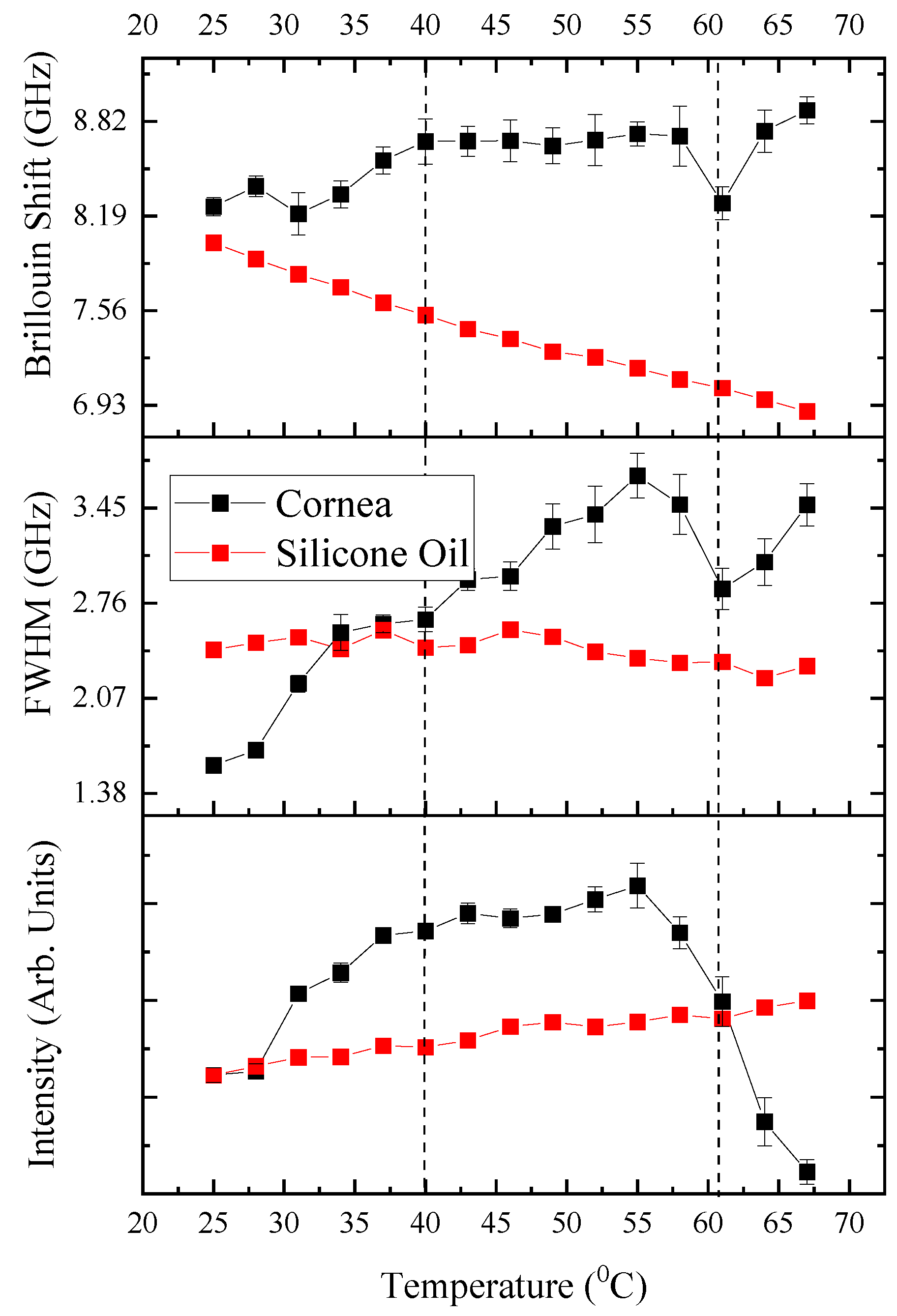

3.2. Phase Transitions: Raw Spectral Indicators

Figure 3 presents the raw spectral indicators of phase transitions in ovine corneal tissue as measured by BLS spectroscopy. It displays the relationship between temperature and the key spectral parameters—Brillouin shift, FWHM, and intensity—each fitted with multiple Lorentzian peaks to reveal the distinct transformations within the tissue’s biomechanical properties as the temperature increases. As the spectral features associated with silicone oil and corneal tissue begin to separate at

T > 40°C, a multi-peak Lorentzian fitting approach was implemented using OriginPro software. This nonlinear deconvolution analysis allowed for the precise extraction of peak positions, FWHM, and intensities for the corneal peaks within the composite spectrum, even when overlapping with the silicone oil signal. The Lorentzian fitting parameters were carefully iterated to ensure that the composite fit accurately represented the underlying raw signal. This detailed spectral analysis underpins the observed mechanical behavior changes of the cornea under progressive thermal stress, crucial for understanding its viscoelastic and phase transition properties.

The Brillouin shift, indicative of the elastic modulus of the cornea, exhibits a pronounced peak at approximately 60 - 63°C, signifying a critical change in corneal stiffness. This observation aligns with the anticipated thermal-induced denaturation of collagen, characterized by a transition from the native triple helical structure to a disordered gelatin-like arrangement, resulting in a weakened stromal network [

41]. Concurrently, the full width at half maximum (FWHM) values, which reflect the viscoelastic damping properties and acoustic phonon life cycle within the tissue, progressively increase and culminate in a marked surge at this temperature range. This pattern is a clear sign of a phase change where the cornea becomes less stiff and more flexible, which matches up with how the cornea acts when the collagen starts to break down and lose its normal structure.

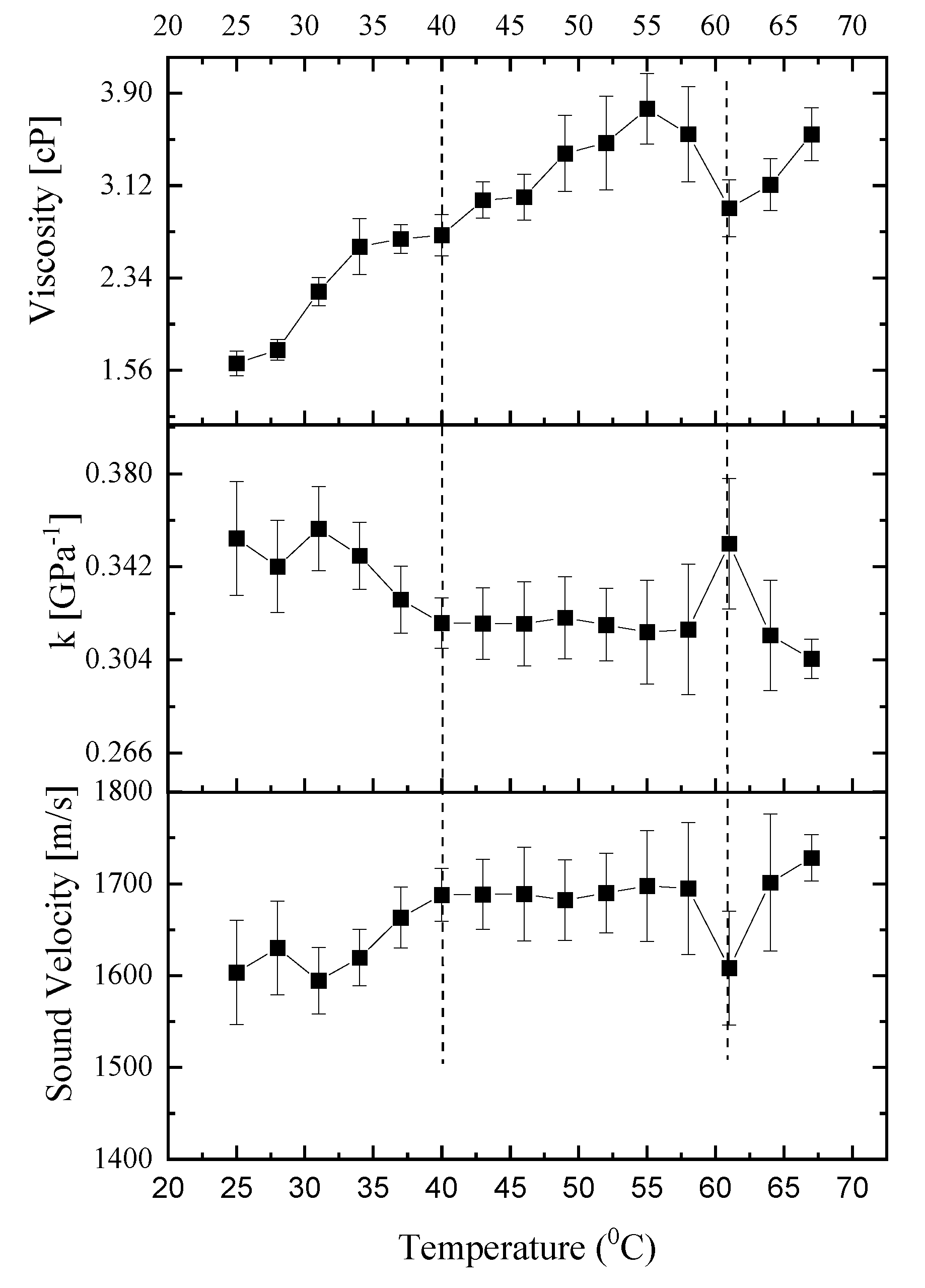

3.3. Viscoelastic Properties

Figure 4 illustrates the variations in hypersound velocity, compressibility, and apparent viscosity as a function of temperature, based on Brillouin spectroscopy measurements from a characteristic specimen. This figure elucidates how the viscoelastic characteristics of the sample change when subjected to temperatures above and below the critical phase transition threshold of

T~60-63°C. The comparative analysis of these properties across the phase transition temperature provides insight into the material’s behavior under different thermal conditions.

3.3.1. Viscosity

Figure 4 presents the correlation between temperature and the cornea’s apparent viscosity as determined by Equation (3). This figure reveals a progressive rise in viscosity up to a phase transition temperature of ~ 60-63°C, a pattern that echoes findings in collagen solutions [

42] where a temperature elevation led to increased intrinsic viscosity. The augmentation in the cornea’s intrinsic viscosity with temperature is attributed to the tendency of collagen molecules within the cornea to aggregate at elevated temperatures, facilitated by increased hydrophobic interactions among the molecules. This aggregation behavior of collagen molecules at elevated temperatures is corroborated by Na

et al. [

43], who used electrophoresis and thermal denaturation techniques to study molecular properties, and by Pederson

et al. [

44], who examined thermal responses using X-ray diffraction and calorimetry in their biomimetic studies. Beyond the phase transition temperature (>60°C), there is an apparent reduction in the cornea’s viscosity. This observation parallels findings in gelatin solutions, where intrinsic viscosity diminishes as temperature increases [

45,

46]. The decrease in corneal viscosity at elevated temperatures could be hypothesized to relate to the structural transformation of collagen into gelatin within the corneal tissue. Collagen, the primary structural protein in the cornea, undergoes denaturation at high temperatures, transitioning into gelatin—a process that could lead to the observed reduction in viscosity. This transformation suggests a breakdown or alteration of the collagen’s triple-helical structure, potentially leading to a less organized and therefore less viscous state, resembling the behavior of gelatin solutions under similar thermal conditions.

3.3.2. Hypersound Velocity and the Influence of Polymerization Temperature

The viscoelastic properties of biological tissues are known to be intricately linked to their microstructural characteristics. In the ovine cornea, the collagen network architecture, which includes factors such as network connectivity, pore size, and fiber diameter, is particularly sensitive to the polymerization temperature. Our experimental results reveal that, within the temperature range of 25°C to 40°C, the hypersound velocity of the ovine cornea exhibits an upward trend at a rate of 0.6 meters per second per degree Celsius. This observed enhancement in hypersound velocity with temperature can be partially attributed to the modifications in the degree of collagen alignment, which are dependent on the polymerization temperature [

47,

48]. Specifically, collagen matrices that were polymerized at different temperatures of 25˚C and 37˚C exhibited variations in alignment. This finding aligns with the work of Taufalele et al. [

49], who demonstrated that polymerization temperature can modify the degree of collagen alignment. Such alterations in the matrix structure could potentially enhance the efficiency of acoustic wave transmission through the tissue matrix. Viscoelastic relaxation phenomena, inherent to the cornea’s biomechanical behavior, are also temperature-dependent [

40]. Elevated temperatures may reduce the viscous component of the tissue, diminishing the energy dissipation and allowing sound waves to propagate more rapidly. Changes in the cornea’s hydration level with temperature can significantly influence hypersound velocity. As the cornea heats, alterations in water content and distribution could account for the velocity increase, considering water’s high sound speed [

50]. However, since we used silicone oil, there is little effect of hydration. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the precise microstructural alterations that contribute to the thermal behavior observed in our BLS measurements.

3.3.3. Adiabatic Compressibility & Complex Longitudinal Modulus

Table 1 displays the complex longitudinal modulus values of cornea, specifically the storage and loss moduli, at various selected temperatures. At the starting point of 25°C, the storage (bulk) modulus for the cornea is on par with that of silicone oil, marking its lowest measured value at this temperature. When the temperature reaches the physiologically relevant 37°C, the bulk modulus for the cornea is approximately 21% higher than that of silicone oil. At 25°C, the storage (bulk) modulus for the cornea is on par with that of silicone oil, marking its lowest measured value at this temperature. Upon reaching the physiologically relevant 37°C, the bulk modulus for the cornea is approximately 21% higher than that of silicone oil. Notably, the transition around 40°C represents a phase change, potentially linked to the initial unfolding of collagen, which might not significantly affect the modulus at 37°C but indicates the onset of structural changes within the corneal tissue that precede the more pronounced denaturation phase. With increasing temperature, the storage and loss moduli of the cornea increase, contrasting with the decrease observed for silicone oil. Supporting this temperature dependency, longitudinal modulus values reported by Brillouin Light Scattering in the literature for normal human corneas range from 2.74 to 2.81 GPa at room temperature in Yun et al. [

51], closely aligning with our findings of a 2.95 GPa storage modulus at 37°C. A distinct trend is observed: with rising temperature, the storage and loss moduli of the cornea increase, whereas those of silicone oil tend to decrease. Additionally, the loss modulus, which is indicative of energy loss as heat in a system, shows that lower temperatures are associated with greater energy loss, paralleling the trend seen with the full width at half maximum (FWHM) as a function of temperature.

Figure 4 shows the temperature dependence of the adiabatic compressibility of the mucus,

κs = 1/ρv. The compressibility displays a maximum at 33 °C and 63°C. Above 33 °C,

κs increases dramatically with increasing temperature, while at the transition point (63°C) it shows a sharp increase with increasing temperature. Throughout the assessed temperature range (40°C to 60°C),

κs displayed remarkable stability, suggesting that the corneal microstructure is resilient to temperature-induced changes. This consistency aligns with the cornea’s role in maintaining ocular integrity under various environmental conditions [

52]. The minor changes detected in the

κs with temperature variations can provide insights into the conformational changes that collagen fibrils experience. These changes are due to the disruption of various cross-links at the molecular level. This includes the nonenzymatic glycosylation of lysine and hydroxylysine residues at the intermolecular level, and the breaking of disulfide bridges at the intramolecular level [

53].

4. Conclusions

In this study, we applied Brillouin light scattering (BLS) spectroscopic sensing to assess the GHz-frequency viscoelastic properties and phase transitions of ovine cornea, which was submerged in silicone oil to ensure consistent hydration, across a temperature spectrum of 25 to 70°C. Through our analysis, we delineated heat-driven phase transitions within the physiological temperature range of 30-40°C, attributed to alterations in molecular dynamics and intermolecular bonding within the collagen network. This transition precedes a more distinct phase shift observed between 60-63°C, marked by significant increases in Brillouin shift and linewidth, indicative of collagen fibril denaturation and the consequential breakdown of the corneal tissue’s structured integrity. The use of silicone oil for hydration maintenance was crucial in allowing the BLS spectroscopy to capture these biomechanical changes effectively.

Our findings not only shed new light on the viscoelastic properties and phase behavior of corneal stroma but also enhance the biomedical understanding of the corneal response to thermal stress. Importantly, this study underscores the utility of BLS spectroscopy as a powerful biosensing technique for non-invasive, localized measurements of biopolymers like corneal collagen. The ability to monitor optically and characterize these phase transitions in cornea at both physiological and elevated temperatures can be used to implement in-situ real-time non-invasive optical bio-sensing of mechanical properties of cornea during its refractive surgery.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.K. and Z.U; methodology, C.K; software, C.K; validation, C.K; formal analysis, C.K.; investigation, C.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.K.; writing—review and editing, C.K. and Z.U.; visualization, C.K. and Z.U.; supervision, Z.U.; project administration, C.K. and Z.U.; funding acquisition, C.K. and Z.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

CK acknowledges grant funding of the research of young scientists under the “Zhas Galym” project for 2022-2024 from the Ministry of Science and Higher Education of the Republic of Kazakhstan (grant No. AP14972763).

Data Availability Statement

The data are available by requesting the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Munnerlyn, C.R.; Koons, S.J.; Marshall, J. Photorefractive Keratectomy: A Technique for Laser Refractive Surgery. J Cataract Refract Surg 1988, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Radi, M.; Shehata, M.; Mostafa, M.M.; Aly, M.O.M. Transepithelial Photorefractive Keratectomy: A Prospective Randomized Comparative Study between the Two-Step and the Single-Step Techniques. Eye (Basingstoke) 2023, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shen, Y.; Zhou, X. Keratometry and Ultrastructural Changes after Microwave Thermokeratoplasty in Rabbit Eyes. Lasers Surg Med 2022, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomás-Juan, J.; Murueta-Goyena Larrañaga, A.; Hanneken, L. Corneal Regeneration after Photorefractive Keratectomy: A Review. J Optom 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brinkmann, R.; Koop, N.; Geerling, G.; Kampmeier, J.; Borcherding, S.; Kamm, K.; Birngruber, R. Diode Laser Thermokeratoplasty: Application Strategy and Dosimetry. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Tang, M.; Shekhar, R. Mathematical Model of Corneal Surface Smoothing after Laser Refractive Surgery. Am J Ophthalmol 2003, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karampatzakis, A.; Samaras, T. Numerical Model of Heat Transfer in the Human Eye with Consideration of Fluid Dynamics of the Aqueous Humour. Phys Med Biol 2010, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharmyssov, C.; Abdildin, Y.G.; Kostas, K. V. Optic Nerve Head Damage Relation to Intracranial Pressure and Corneal Properties of Eye in Glaucoma Risk Assessment. Med Biol Eng Comput 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimni, M.E.; Harkness, R.D. Molecular Structure and Functions of Collagen. In Collagen: Volume I: Biochemistry; 2018.

- Thomsen, S. PATHOLOGIC ANALYSIS OF PHOTOTHERMAL AND PHOTOMECHANICAL EFFECTS OF LASER–TISSUE INTERACTIONS. Photochem Photobiol 1991, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoerl, E.; Wollensak, G.; Dittert, D.D.; Seiler, T. Thermomechanical Behavior of Collagen-Cross-Linked Porcine Cornea. Ophthalmologica 2004, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knott, L.; Tarlton, J.F.; Bailey, A.J. Chemistry of Collagen Cross-Linking: Biochemical Changes in Collagen during the Partial Mineralization of Turkey Leg Tendon. Biochemical Journal 1997, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, C.A.; Chen, Y.F.; Liu, M.W. Thermal Properties Measurements of Renatured Gelatin Using Conventional and Temperature Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry. J Appl Polym Sci 2006, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozec, L.; Odlyha, M. Thermal Denaturation Studies of Collagen by Microthermal Analysis and Atomic Force Microscopy. Biophys J 2011, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurbanova, B.; Ashikbayeva, Z.; Amantayeva, A.; Sametova, A.; Blanc, W.; Gaipov, A.; Tosi, D.; Utegulov, Z. Thermo-Visco-Elastometry of RF-Wave-Heated and Ablated Flesh Tissues Containing Au Nanoparticles. Biosensors (Basel) 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akilbekova, D.; Yakupov, T.; Ogay, V.; Umbayev, B.; Yakovlev, V. V.; Utegulov, Z.N. Brillouin Light Scattering Spectroscopy for Tissue Engineering Application. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, Z.; Troyanova-Wood, M.; Traverso, A.J.; Yakupov, T.; Utegulov, Z.N.; Yakovlev, V. V. Assessing Performance of Modern Brillouin Spectrometers. Opt Express 2018, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharmyssov, C.; Sekerbayev, K.; Nurekeyev, Z.; Gaipov, A.; Utegulov, Z.N. Mechano-Chemistry across Phase Transitions in Heated Albumin Protein Solutions. Polymers (Basel) 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarcelli, G.; Pineda, R.; Yun, S.H. Brillouin Optical Microscopy for Corneal Biomechanics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcelli, G.; Kling, S.; Quijano, E.; Pineda, R.; Marcos, S.; Yun, S.H. Brillouin Microscopy of Collagen Crosslinking: Noncontact Depth-Dependent Analysis of Corneal Elastic Modulus. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcelli, G.; Besner, S.; Pineda, R.; Yun, S.H. Biomechanical Characterization of Keratoconus Corneas Ex Vivo with Brillouin Microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2014, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Roozbahani, M.; Piccinini, A.L.; Golan, O.; Hafezi, F.; Scarcelli, G.; Randleman, J.B. Depth-Dependent Reduction of Biomechanical Efficacy of Contact Lens–Assisted Corneal Cross-Linking Analyzed by Brillouin Microscopy. Journal of Refractive Surgery 2019, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarcelli, G.; Besner, S.; Pineda, R.; Kalout, P.; Yun, S.H. In Vivo Biomechanical Mapping of Normal and Keratoconus CorneasIn Vivo Biomechanical Mapping of CorneasLetters. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.H.; Lai, C.C.; Rouch, J. Experimental Confirmation of Renormalization - Group Prediction of Critical Concentration Fluctuation Rate in Hydrodynamic Limit. J Chem Phys 1977, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachev, S.N.; Bass, J.D. Brillouin Scattering Study of Pentane at High Pressure. Journal of Chemical Physics 1996, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dil, J.G. Brillouin Scattering in Condensed Matter. Reports on Progress in Physics 1982, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.; Alunni-Cardinali, M.; Correa, N.; Caponi, S.; Holsgrove, T.; Barr, H.; Stone, N.; Winlove, C.P.; Fioretto, D.; Palombo, F. Viscoelastic Properties of Biopolymer Hydrogels Determined by Brillouin Spectroscopy: A Probe of Tissue Micromechanics. Sci Adv 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randleman, J.B.; Su, J.P.; Scarcelli, G. Biomechanical Changes after LASIK Flap Creation Combined with Rapid Cross-Linking Measured with Brillouin Microscopy. Journal of Refractive Surgery 2017, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kikkawa, Y.; Hirayama, K. Uneven Swelling of the Corneal Stroma. Invest Ophthalmol 1970, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.; O’Leary, D.J.; Vaughan, W. Differential Swelling in Compartments of the Corneal Stroma. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1984, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Vasudevan, B.; Simpson, T.L.; Sivak, J.G. Regional Variation in the Refractive-Index of the Bovine and Human Cornea. Optometry and Vision Science 2008, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castoro, J.A.; Bettelheim, A.A.; Bettelheim, F.A. Water Gradients across Bovine Cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1988, 29. [Google Scholar]

- Akilbekova, D.; Ogay, V.; Yakupov, T.; Sarsenova, M.; Umbayev, B.; Nurakhmetov, A.; Tazhin, K.; Yakovlev, V. V.; Utegulov, Z.N. Brillouin Spectroscopy and Radiography for Assessment of Viscoelastic and Regenerative Properties of Mammalian Bones. J Biomed Opt 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seiler, T.G.; Shao, P.; Frueh, B.E.; Yun, S.H.; Seiler, T. The Influence of Hydration on Different Mechanical Moduli of the Cornea. Graefe’s Archive for Clinical and Experimental Ophthalmology 2018, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shao, P.; Seiler, T.G.; Eltony, A.M.; Ramier, A.; Kwok, S.J.J.; Scarcelli, G.; Pineda, R.; Yun, S.H.A. Effects of Corneal Hydration on Brillouin Microscopy in Vivo. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2018, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darracq, G.; Couvert, A.; Couriol, C.; Amrane, A.; Thomas, D.; Dumont, E.; Andres, Y.; Le Cloirec, P. Silicone Oil: An Effective Absorbent for the Removal of Hydrophobic Volatile Organic Compounds. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology 2010, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatami-Marbini, H.; Rahimi, A. Effects of Bathing Solution on Tensile Properties of the Cornea. Exp Eye Res 2014, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Huang, X.; Wang, J.; Yao, M.; Wang, K.; Huang, F.; Han, B.; Zhou, Q.; Li, F. Acoustic and Elastic Properties of Silicone Oil under High Pressure. RSC Adv 2015, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leikina, E.; Mertts, M. V.; Kuznetsova, N.; Leikin, S. Type I Collagen Is Thermally Unstable at Body Temperature. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kampmeier, J.; Radt, B.; Birngruber, R.; Brinkmann, R. Thermal and Biomechanical Parameters of Porcine Cornea. Cornea 2000, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, Q.; Yu, S.M.; Li, Y. The Chemistry and Biology of Collagen Hybridization. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Qiao, C.; Shi, L.; Jiang, Q.; Li, T. Viscosity of Collagen Solutions: Influence of Concentration, Temperature, Adsorption, and Role of Intermolecular Interactions. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B: Physics 2014, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, G.C. Monomer and Oligomer of Type I Collagen: Molecular Properties and Fibril Assembly. Biochemistry 1989, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pederson, A.W.; Ruberti, J.W.; Messersmith, P.B. Thermal Assembly of a Biomimetic Mineral/Collagen Composite. Biomaterials 2003, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, X.; Qiao, C.; Li, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, T. Viscometric Study of the Gelatin Solutions Ranging from Dilute to Extremely Dilute Concentrations. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B: Physics 2011, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrusci, C.; Martín-González, A.; Del Amo, A.; Corrales, T.; Catalina, F. Biodegradation of Type-B Gelatine by Bacteria Isolated from Cinematographic Films. A Viscometric Study. Polym Degrad Stab 2004, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raub, C.B.; Suresh, V.; Krasieva, T.; Lyubovitsky, J.; Mih, J.D.; Putnam, A.J.; Tromberg, B.J.; George, S.C. Noninvasive Assessment of Collagen Gel Microstructure and Mechanics Using Multiphoton Microscopy. Biophys J 2007, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, K.A.; Licup, A.J.; Sharma, A.; Rens, R.; MacKintosh, F.C.; Koenderink, G.H. The Role of Network Architecture in Collagen Mechanics. Biophys J 2018, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taufalele, P. V.; VanderBurgh, J.A.; Muñoz, A.; Zanotelli, M.R.; Reinhart-King, C.A. Fiber Alignment Drives Changes in Architectural and Mechanical Features in Collagen Matrices. PLoS One 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Ma, J.; Zhao, J.; Qi, P.; Li, M.; Lin, L.; Sun, L.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y. Corneal Hydration Assessment Indicator Based on Terahertz Time Domain Spectroscopy. Biomed Opt Express 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, S.H.; Chernyak, D. Brillouin Microscopy: Assessing Ocular Tissue Biomechanics. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2018, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurpakus-Wheater, M.; Kernacki, K.A.; Hazlett, L.D. Maintaining Corneal Integrity How the “Window” Stays Clear. Prog Histochem Cytochem 2001, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, C.A.; Bailey, A.J. Thermal Denaturation of Collagen Revisited. Proceedings of the Indian Academy of Sciences: Chemical Sciences 1999, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).