1. Introduction

With global warming, frequent natural disasters, resource shortages, and other environmental issues becoming increasingly prominent, green development has garnered widespread consensus within the international community. Consequently, the concept of green development has been further integrated into the supply chain field. In 2018, the Notice on the Pilot Project on Supply Chain Innovation and Application underscored the importance of developing the entire process and linkages within the green supply chain system. Moreover, with the rapid expansion of the e-commerce industry, numerous enterprises have established online direct sales channels, fostering a dual-channel sales model that encompasses both online and offline channels. Notable examples include IBM, Apple, Nike, and Haier, among others.

However, as enterprises explore new channels and ramp up green product production, the financial strain on these businesses has significantly intensified. Certain manufacturers in such dual-channel supply chain may lack the capital to support production. For instance, Tesla, as a green enterprise, has resorted to fundraising methods such as stock and bond issuance, as well as loans, to support its electric vehicle production and solar product development. Moreover, in day-to-day operations, the uncertainty of the market environment coupled with the intricacies of dual-channel dynamics pose challenges. Compared to conventional products, green products may exhibit lower cost performance, and consumer inclination to purchase them might not be as robust, resulting in actual market demand falling below projections. Consequently, all supply chain members encounter a range of potential risks. The diverse risk attitudes among decision-makers profoundly influence their choices. Particularly for manufacturers grappling with financial constraints, a shortage of funds is more likely to foster risk aversion. This not only impacts the decision-making processes within the enterprise itself but also has a ripple effect throughout other supply chain members and the entire supply chain ecosystem.

Alongside, the rise in per capital disposable income and the increasing popularity of environmental consciousness, consumers are becoming more mindful of environmental protection. Their purchasing decisions are no longer solely influenced by price, they also consider the environmental impact of products and whether they contribute to environmental harm. Green preferences directly shape consumers' buying behavior, consequently impacting enterprise production. For instance, in the first half of 2020, Toyota Motor Corporation and BYD Company limited collaborated to establish a joint-venture automobile research and developing company. Their focus was on technology investment and leveraging the expertise of both China and Japan to advance electric vehicle development and enhance the friendliness of the electric vehicle industry. However, it's important to note that not all consumers are willing to pay a premium for green products. Preferences vary among consumers. Additionally, the advent of e-commerce has revolutionized product transaction methods and purchase channels. Consumers now have the option to experience products firsthand in offline stores or conveniently purchase them online. Consumers’ choice of purchase channel depends on individual circumstances. Consumers who prefer online shopping tend to prioritize factors like product prices, online reviews, and popular recommendations (Mazaheri et al., 2011). However, they miss out on the tactile experience of inspecting the quality of purchased items in person, leading to a diminished shopping experience online (Kim and Han, 2023).

Accordingly, we extend the current dual-channel supply chain by considering consumer preferences and risk aversion, involving both a retailer and a capital-constrained manufacturer. The manufacturer specializes in producing green products, distributing them through both online and offline channels, while the retailer focuses solely on offline sales. Addressing the manufacturer’s capital constraints, we consider two financing strategies. In the bank loan strategy, the manufacturer seeks external funding to cover its production costs, whereas in the trade credit strategy, the retailer offers trade credit to the manufacturer. Driven by this setting, our motivation stems from the interest in answering the following questions: (a) What are firms' equilibrium decisions under each financing strategy in the dual-channel green supply chain? (b) How do consumer preferences and risk aversion influence the equilibrium outcomes?

To address these questions, we initially construct game models to characterize the interactions between the retailer and the manufacturer and derive equilibrium decisions under the two distinct financing strategies. Concurrently, we analyze the effects of consumer preferences and risk aversion on equilibrium through numerical analysis. An intriguing observation is that each equilibrium solution decreases with increasing manufacturer risk aversion. Moreover, an increase in consumer preferences for online shopping is associated with higher product greenness and wholesale price, while the sale price is also influenced by consumer green preferences. Additionally, our comparative analysis of the two financing strategies reveals that the trade credit strategy outperforms bank loans.

In summary, our main contributions are as follows. First, this study innovatively considers consumer preferences in the dual-channel green supply chains with capital constraints. Furthermore, it identifies the impact of consumer preferences on firms' equilibrium decisions. Second, in addition to examining the trade-off between trade credit and bank loan under capital limitations, this study innovatively incorporates the risk aversion of manufacturers into the competition model. We further investigate how this risk aversion influences firms' equilibrium decisions. Finally, through comparative studies on various financing strategies, our conclusions offer important theoretical guidance for retailers and manufacturers in selecting financing strategies.

The rest of this paper is structured as follows:

Section 2 presents a literature review of related studies.

Section 3 introduces the model description and assumptions.

Section 4 develops and analyzes the Stackelberg game model of manufacturer-retailer under bank loan and trade credit financing models.

Section 5 conducts numerical simulations under the two strategies, and section 6 concludes.

2. Literature

As an increasing number of enterprises in dual-channel supply chains face funding shortages, scholars have begun to investigate the impact of capital constraints on corporate financing. However, existing research primarily focuses on traditional retail channel environments, leaving a scarcity of literature on supply chain financing within dual-channel contexts. Xu and Birge (2008) were pioneers in utilizing the Newsvendor model to explore how capital constraints affect company inventory levels, with particular attention to the influence of capital constraints and structure. In recent years, an expanding body of literature has delved into the preferences between bank credit and trade credit for financing. Some studies suggest that trade credit offers more advantages over bank loans due to its role in alleviating double marginalization (Tang et al., 2018; Yang et al., 2017; Alex et al., 2018). Kouvelis and Zhao (2016) emphasized that trade credit serves as a significant source of short-term financing between enterprises. Compared to bank financing, internal financing from suppliers often benefits retailers more. Xiao et al. (2017) investigated coordination issues in dual-channel supply chains when manufacturers borrow from banks and provide trade credit to retailers. Li et al. (2020) examined three financing methods adopted by capital-constrained manufacturers to address financing challenges: trade credit, bank loans, and mixed financing. Their findings suggest that when the proportion of equity financing is either large or small, trade credit emerges as the balanced strategy. Conversely, when the proportion of equity financing is moderate, consumer preferences and loan rates determine the equilibrium between trade credit and mixed financing. Cao et al. (2019), considering uncertain demand and customer preferences for low-carbon products, analyzed the financing preferences of banks and suppliers. They concluded that regardless of whether manufacturers invest in emissions reduction, trade credit financing remains the superior choice for manufacturers. Qin et al. (2020) investigated a supply chain model under both prepaid and non-prepaid financing conditions when manufacturers have ample funds. They compared bank financing with mixed financing when manufacturer capital is constrained. Kouvelis and Zhao (2018) assumed capital constraints for both retailers and suppliers, exploring inventory financing responsibility and the appropriate interest rates considering varying credit ratings among supply chain participants.

As market instability and competition intensify, businesses become increasingly sensitive to risk, and their risk-averse behavior influences relevant decisions. Therefore, when studying issues in green supply chains, the risk-averse behavior of supply chain members is also an important factor to consider. Although existing literature has examined the risk-averse characteristics of members in capital-constrained supply chains, such as references (Yan et al., 2019; Yan et al., 2020; Qi et al., 2020), there is a lack of research simultaneously considering the risk-averse characteristics of members and capital constraints in the field of green supply chains, especially regarding their impact on supply chain operations, financing, and decision-making. Zhou et al. (2018) conducted a comparative analysis of static and dynamic risk-averse behavior on supply chain operations. Cao et al. (2022) focused on the impact of manufacturer risk aversion on product green levels and pricing decisions, finding that manufacturer risk aversion increases retailer profits but decreases the greenness of the product. Cai et al. (2022) established centralized and decentralized decision-making green supply chain models, analyzing the impact of member risk-averse characteristics on them. The study found that in a centralized supply chain, enterprise risk-averse behavior leads to decreases in product green levels and sale price, while in a decentralized supply chain, enterprise risk-averse behavior results in decreases in wholesale prices and sale price. Huang et al. (2020) studied the coordination and risk-sharing issues of supply chains composed of retailers and risk-averse manufacturers, proposing a combined contract model including options and cost-sharing. The research results indicate that combined contracts can coordinate the supply chain, but coordination can only be achieved when the manufacturer's risk aversion is low, with the manufacturer's risk aversion being an important factor in contract design and profit distribution. Kang et al. (2022) investigated financing strategy selection and coordination issues in a capital-constrained supply chain between risk-neutral retailers and risk-averse suppliers. The study found that the supplier's risk aversion level critically influences the choice of financing strategy and proposes providing different financing strategy recommendations to retailers based on risk attitude and profit-sharing coefficient. Ke et al. (2018) studied the closed-loop supply chain pricing problem of two competitively risk-sensitive retailers in an uncertain environment. The results show that when either of the two retailers becomes risk-averse, their profits decrease, while the manufacturer's profit increases.

While the literature discussed above contributes significantly to understanding pricing decisions in green supply chains under capital constraints, it primarily focuses on the perspective of supply chain members. However, consumers, as the ultimate end-users and primary consumption source, are a crucial link in this chain. Therefore, exploring pricing decisions in green supply chains from the standpoint of consumer preferences is of paramount importance.

While the literature discussed above contributes significantly to understanding pricing decisions in green supply chains under capital constraints, it primarily focuses on the perspective of supply chain members. However, consumers, as the ultimate end-users and primary consumption source, are a crucial link in this chain. Therefore, exploring pricing decisions in green supply chains from the standpoint of consumer preferences is of paramount importance.

Consumer environmental awareness significantly influences the decision-making and evolution of green supply chains. As the preference for green products grows, consumers are increasingly concerned about the environmental impact of their purchases. According to Consumer Reports, 51% of Americans are willing to pay a premium for green products, and 67% consider the purchase of environmentally friendly products important. As consumer environmental consciousness continues to rise, the competitive advantage of businesses will be directly influenced by the degree of product sustainability. Zhang et al. (2015) proposed a return contract for a two-stage supply chain to explore how consumer preferences for green products affect channel coordination within the supply chain. Du et al. (2016) examined pricing and production decisions of manufacturers under the assumption that consumers value green products more than traditional ones, providing insights into the conditions under which manufacturers are inclined to produce green products. Li et al. (2023) suggested that the increasing preference for green products among consumers and their growing acceptance of remanufactured products positively impact the profits of manufacturers, retailers, and the entire supply chain. Thus, investigating the influence of consumer environmental awareness on green supply chains emerges as a pivotal area of research.

On the other hand, Technological advancements have expanded the channels through which people purchase goods. Nowadays, products are not only available in physical stores but also through online shopping platforms. In the realm of dual-channel supply chains, scholars have classified consumers' arbitrary choices between different channels as subjective preferences for those channels. When examining the impact of consumer channel preferences on dual-channel supply chains, scholars have predominantly investigated research from the perspectives of pricing decisions, production decisions, and the effects on the profits of supply chain members. Wang at al. (2022) investigated the pricing strategies of retailers in a dual-channel supply chain based on consumer channel preferences. They found that as consumers lean towards online shopping, the profits of manufacturers and the overall supply chain increase, while the profits of retailers remain unchanged. Ngoh et al. (2024) explored the effects of retailers transitioning from multi-channel to single-channel on consumer retailer and channel selection. Their results indicate that consumers with a strong preference for online shopping will choose to shop online when resistance is low. Xu et al. (2022) integrated consumer channel preferences with free-riding behavior to study decision-making under centralized and decentralized scenarios. Zhang et al. (2021) analyzed manufacturers' channel selection decisions across three different channel strategies based on consumer channel preferences. The research findings suggest that manufacturers' channel preferences depend not only on channel operating costs and consumer channel preferences but also on the influence of competitors' channel strategies. In addition to studying individual consumer preferences, most other literature combines consumer green preferences with channel preferences. Meng et al. (2021) delved into product synergistic pricing policies within a dual-channel green supply chain based on consumer green and channel preferences. The study found that government subsidies play a vital role in meeting consumer green demands, especially when consumer green preferences are high or offline channel preferences are low, leading to increased demand for green products. Li et al. (2016) investigated consumer dual preferences, establishing a dual-channel supply chain model and examining the circumstances under which manufacturers choose direct sales channels. Their findings revealed that manufacturers refrain from opening direct sales channels when the investment cost of green manufacturing is high. However, they may choose to do so when consumers' preference for retail channels aligns with the manufacturer's green manufacturing costs under certain conditions. Similarly, Ji et al. (2017) developed a model considering consumer dual preferences and analyzed the factors influencing manufacturers' decisions to open direct sales channels. They highlighted the importance of consumer preferences in determining when manufacturers opt for direct sales channels, emphasizing the need for specific conditions to be met. Rahmani and Mohammad (2019) explored the scenario of manufacturers embracing green manufacturing while also factoring in demand disruptions in their study on consumer dual preferences. The research indicates that when manufacturers have lower green manufacturing costs and consumers exhibit reduced preferences for retail channels, market demand increases. This, in turn, stimulates the enhancement of product greenness and leads to increased profits for supply chain members.

Existing literature has extensively researched green supply chain pricing, consumer preferences, and risk mitigation. However, there is still ample scope for further exploration. Specifically, one area worthy of attention is the impact of government subsidies and power structures. While current research predominantly examines how government subsidies, power dynamics, and other variables affect the pricing decisions of dual-channel green supply chains, few studies have addressed the influence of financial constraints on such decisions. Additionally, a comprehensive investigation into the combined effects of factors like financial constraints, consumer green preferences, and channel preferences is lacking. Moreover, while considerable attention has been devoted to studying dual-channel green supply chains and their coordination strategies, there has been limited consideration given to the influence of member risk aversion characteristics on supply chain pricing decisions. Although existing research acknowledges the importance of member risk attitudes in practical scenarios, their direct impact on pricing decisions has not been extensively explored. Hence, this article aims to extend current research by considering consumer green preferences and channel preferences, taking into account scenarios where manufacturers are engaged in green production but face financial constraint. Through a comprehensive analysis of these factors, this study seeks to explore pricing issues within dual-channel green supply chains, aiming for a more thorough understanding of the factors influencing supply chain pricing decisions.

Table 1.

Literature review.

Table 1.

Literature review.

| Literature |

Dual-channel |

Green supply chain |

Financial constraints |

Risk attitude |

Consumer

preference |

| Cao et al. |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

| Kouvelis et al. |

√ |

|

√ |

|

|

| Huang et al. |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

| Kang et al. |

|

|

√ |

√ |

|

| Meng at al. |

√ |

√ |

|

|

√ |

| Rahmani et al. |

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

| Ji et al. |

|

√ |

|

|

√ |

| Ngoh et al. |

√ |

|

|

|

√ |

| Qin et al. |

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

|

| Cai et al. |

|

√ |

√ |

√ |

|

| This study |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

√ |

3. Conditional Assumption

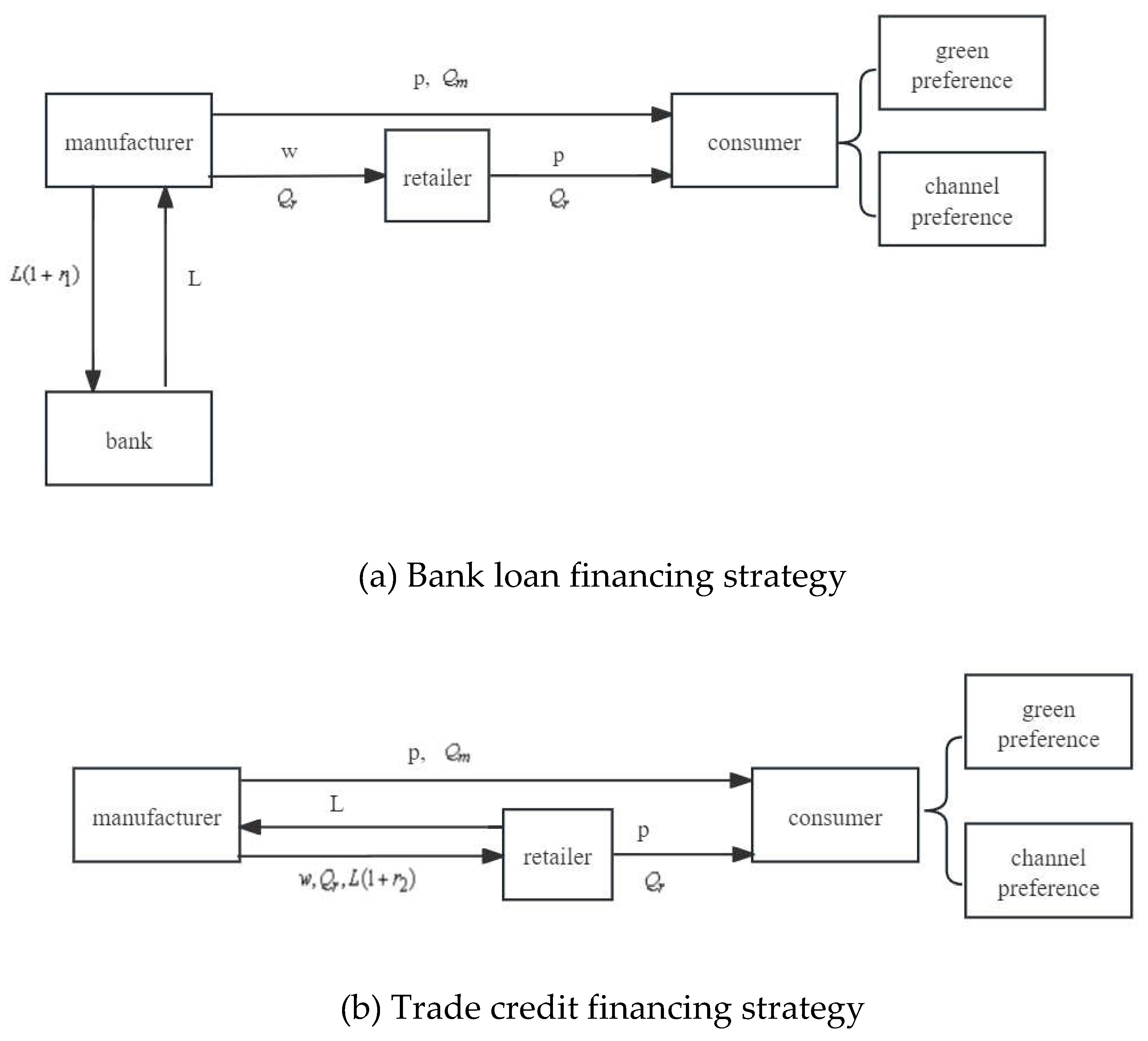

This paper investigates a dual-channel green supply chain, comprising one retailer and one capital-constrained manufacturer. The manufacturer produces green products with a long lead time in production and sells the products not only to the retailer but also to the consumers directly. Consumers may purchase the products from retailer channel or direct online channel according to their preferences. It is assumed that when the manufacturer encounters financial constraints, it can choose bank loan financing or trade credit financing to secure funds (see

Figure 1) :(a) bank loan financing strategy, in this case, the manufacturer obtains a loan from the bank at an interest rate

to acquire the necessary production funds. At the end of the sale cycle, the manufacturer promises to repay the borrowed funds with interest to the bank. (b) trade credit financing strategy, in this case, the retailer pays part of the partial payment in advance so that the manufacturer can finance their production activities.

In order to elucidate the research problem in this paper, the following basic assumptions are posited.

Assumption 1: The manufacturer, as the primary decision-maker, determines both the wholesale price and the greenness of the product, while the retailer collaborates in setting the sale price based on the manufacturer's decisions.

Assumption 2: The pricing for the product line and offline sales remains consistent, without accounting for the effects of dual-channel differential pricing.

Assumption 3: Market demand is stochastic, with denoting the demand

for the online channel and denoting the demand

for the retail channel, respectively.

where

denotes sale price,

denotes the basic market demand of the product and is a constant,

denotes the casual demand due to market uncertainty and

,

denotes the degree of consumer preferences online market and

denotes the degree of preference in the offline market,

denotes the coefficient of green preference of the consumer, and

denotes the greenness of the product.

Assumption 4: Suppose that the manufacturer’s R&D investment for improving the greenness of the product is , where denotes the green input cost coefficient.

Assumption 5: The manufacturer's unit cost of production is assumed to be , the wholesale price offered by the manufacturer to the retailer is , and the cost of goods sold by both the manufacturer and the retailer is assumed to be 0. To ensure that the demand of profits gained by the manufacturer and the retailer become non-negative, must be satisfied.

Assumption 6: This paper employs the mean-variance method to evaluate the risk aversion in green supply chain members (Zhang et al., 2022). Additionally, when the manufacturer exhibits a risk-averse attitude, its utility is defined as , Where , indicates the degree of risk aversion of the maintains a risk-neutral attitude, while signifies that the manufacturer exhibits a risk-averse tendency. The greater the value of ,the more risk-averse the manufacturer becomes.

The following notations are defined to model the problem.

Table 2.

Notations.

| Notation |

Explanation |

|

basic market demand |

|

stochastic demand |

|

standard deviation |

|

wholesale price |

|

sale price |

|

consumer’s online channel preference |

|

consumer’s offline channel preference |

|

consumer’s green preference |

|

greenness of the product |

|

green input cost |

|

production cost per unit of product |

|

manufacturer risk aversion factor |

|

retailer risk aversion factor |

|

profit, |

|

expected profit, |

|

expected utility, |

4. Model Construction and Solution

4.1. Baseline Model

To compare the impacts of financing constraints and different financing models on pricing decisions in a dual-channel green supply chain. We first investigate the manufacturer without financial constraints as a baseline case. Following the Stackelberg game, in the dual-channel green supply chain, the risk-averse manufacturer as the leader determines the wholesale price in the retailer channel and the greenness of the product, while the risk-neutral retailer acts as the Stackelberg follower determines the sale price of the two channels. The profit function of the manufacturer is determined by

and the profit function of the retailer is determined by

According to the assumptions, the risk-neutral retailer’s expected profit functions can be obtained

The variance of the manufacturer’s profit when there is risk aversion is

Given the assumptions, the utility function for the manufacturer’s profit can be obtained

Adopt the inverse induction method to solve, we first take the second-order partial derivative of the expected profit function of the retailer

with respect to the sale price

in Eq. (5), we have

, indicating that

is a strictly concave function on

.Let the first partial derivative of the retailer’s expected profit function be 0, we get

Substituting Eq. (8) into Eq. (7), the Hessian matrix of Eq. (7) is found as follows

For

, the Hessian matrix is negative definite when it satisfies

, i.e.,

, which is

, i.e.,

is a concave function with respect to

, and there exists a unique optimal solution.

By simultaneously solving the first-order conditions of the manufacturer's profit function with respect to the wholesale price of the product and the greenness of the product, and setting their first partial derivatives to 0, we can derive the manufacturer's optimal decision.

Proposition 1. With sufficient capital, the manufacturer's profit function is concave with respect to

, implying the existence of a unique sale price, wholesale price of the product, and degree of greenness that maximizes the profit. The manufacturer's optimal decision is given by

Substituting Eq. (9) and Eq. (10) into Eq. (8), the optimal sale price of the product is given by

Corollary 1. When there is sufficient capital and the manufacturer is risk-averse, product greenness, wholesale price, and sale price are negatively related to the degree of manufacturer risk aversion.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivative of Eq. (9) to Eq. (11) with respect to the manufacturer’s risk aversion

, we get

Since , we get , indicating that the manufacturer's wholesale price, sale price, and the greenness of the product all decrease as the manufacturer's risk aversion factor increases.

Corollary 1 indicates that in a manufacturer-dominated dual-channel supply chain, when the manufacturer exhibits risk aversion, the greenness of the product, wholesale price, and sale price all diminish as the manufacturer's risk-aversion coefficient increases. The underlying reason for manufacturer risk aversion is the uncertainty in market demand. A larger manufacturer risk-aversion coefficient indicates a greater disparity between demand and expectation. Consequently, an escalation in the manufacturer’s risk-aversion coefficient corresponds to a decline in expected demand. This prompts the manufacturer to decrease investment in green technology, resulting in diminished the greenness of the product. Additionally, to avert inventory accumulation and enhance sales volume, the manufacturer reduces both wholesale and sale price.

Corollary 2. With sufficient funds, the optimal wholesale price, sale price, and the greenness of the product all increase with the consumer green preference.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivatives of Eq. (9) to Eq. (11) with respect to consumer green preference

, we have

For , it follows that .

Corollary 2 indicates that stronger consumer preferences for green products leads to increased demand for such products, thereby motivating enterprises to invest in green product R&D to capitalize on the potential for higher revenue. As demand for green products escalates, manufacturers raise sale price to maximize profits. Concurrently, due to heightened R&D expenditures, wholesale price also increases accordingly.

Corollary 3. With sufficient funds, both the optimal wholesale price and the greenness of the product increase with consumer online preference.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivatives of Eq. (9) to Eq. (11) with respect to consumer channel preference

,we have

For ,it follows that .

Corollary 3 indicates that when consumers prefer to satisfy their demand for green products through the online channel, the manufacturer holds a channel advantage. In an effort to maximize revenue, the manufacturer will increase the wholesale price of the product, resulting in improved profit margins. Furthermore, recognizing the growing consumer demand for green products, the manufacturer will allocate higher investment in R&D costs to cater to this demand and subsequently boost sales volume. This demonstrates that consumer channel preferences play a significant role in determining the decision-making authority of supply chain members, ultimately influencing the profitability of these members. Supply chain members with channel advantages possess more autonomy in determining green investment strategies and pricing decisions.

4.2. Pricing Decisions under Manufacturer's Capital Constraints

4.2.1. Bank Loan Financing

In this subsection, we consider the situation where the manufacturer encounters capital constraints, that is, its own funds are insufficient to sustain the current production of the firm's products, it chooses to obtain a loan from the bank at an interest rate to acquire the necessary production funds. The manufacturer commits to repaying the borrowed funds to the bank with interest at the conclusion of the sales cycle. We assume the initial capital is and the manufacturer needs to borrow from the bank.

The profit functions of the manufacturer and the retailer could be expressed as follows, respectively

Based on the assumed conditions, the expected profit function for a risk-neutral retailer can be derived as

Given the assumptions, the utility function for the risk-averse manufacturer’s profit can be obtained

The inverse induction method is used to solve the model. First, the second-order partial derivative of the retailer's expected function with respect to the sale price

is calculated for Eq. (12), we get

, indicating that

is a strictly concave function with respect to

. From the first-order condition

of the retailer's expected function

with respect to the sale price

, we get

Substituting Eq. (14) into Eq. (13), the Hessian matrix of Eq. (13) can be expressed as follows

For

,the Hessian matrix is negative definite when it satisfies

,i.e.,

,which is

,i.e.,

is a concave function with respect to

,and there exists a unique optimal solution.

By simultaneously solving the first-order conditions of the manufacturer's profit function with respect to the wholesale price of the product and the greenness of the product, and setting their first partial derivatives to 0, we can derive the manufacturer's optimal decision under the available bank loan financing model.

Proposition 2. In the decentralized decision-making model, when the manufacturer faces capital constraints and employs the financing model of borrowing from the bank, the manufacturer's profit function is concave with respect to

. Consequently, there exists a unique combination of sale price, wholesale price, and the greenness of the product that maximizes profit. The optimal values of the greenness of the product and wholesale price are determined as follows

Substituting Eq. (15) and Eq. (16) into Eq. (14), the optimal sale price is given by

Corollary 4. When the manufacturer faces financial constraints and resorts to borrowing from the bank, the degree of risk aversion influences the wholesale price, sale price, and the greenness of the product in a similar manner as when the manufacturer is well-capitalized. Specifically, when the manufacturer borrows from the bank, the wholesale price is lower than when the manufacturer is well-capitalized ; the sale price is also lower than when the manufacturer is well-capitalized ; and the greenness of the product is reduced .

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivative of Eq. (15) to Eq. (17) with respect to the manufacturer’s risk aversion

, we get

Since ,we have , indicating that the manufacturer's risk aversion coefficient increases, the wholesale price, sale price, and product greenness all decrease.

According to ,it is shown that the greenness of a product is reduced when a manufacturer takes out a bank loan to finance it; according to

. It can be deduced that when a manufacturer opts for bank financing, it tends to lower both the wholesale and sale prices of the product.

Corollary 4 indicates that when faced with financial constraints, manufacturers resorting to bank loans may compromise the greenness of their products, along with reducing wholesale and sale price. This is driven by the manufacturer's risk aversion, leading to decreased input in green production to mitigate potential losses, as well as lowering prices to alleviate inventory backlogs and bolster sales.

Corollary 5. Under the bank loan financing model, the optimal wholesale price, sale price, and the greenness of the product all rise with consumer preferences for environmental protection products.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivatives of Eq. (15) to Eq. (17) with respect to consumer green preference

, we get

Corollary 5 indicates that as consumer preferences for environmental protection products rises, they become more willing to pay higher prices for such products, leading to increased sale prices for green products. Consequently, manufacturers and retailers can enhance profitability by investing more in research and development of green products, thereby increasing both the wholesale price and the greenness of the product.

Corollary 6. Under the bank loan financing model, the optimal wholesale price of the product and the greenness of the product increase with consumer preferences for online consumption.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivatives of Eq. (15) to Eq. (17) with respect to consumer’s channel preference

, we have

Corollary 6 indicates that as consumer preferences for online shopping increases, there is a corresponding surge in the demand for green products online. Consequently, manufacturers will ramp up their R&D investment to produce more environmental protection products, meeting consumer demands and enhancing the greenness of their product offerings. Simultaneously, manufacturers will boost their revenue by hiking the wholesale price, thereby limiting the supply to offline channels and catering more effectively to online demand.

4.2.2. Trade Credit Financing

In this subsequent section, we could like to analyze the application of trade credit by the manufacturer to address financial constraints. We assume the retailer possesses sufficient funds to make partial advance payments to the manufacturer, the manufacturer may incentivize retailers to participate in financing by offering early payment price discounts denoted as . When the retailer is unaffected by any loss of self-interest, have adequate funds and wish to mitigate the risk of channel stockouts, it is inclined to provide the manufacturer with early payment financing. The process unfolds as follows: at the outset of production, the manufacturer extends financing to the retailer at .Subsequently, the retailer procures the product from the manufacturer at ,at the wholesale price , entitling the retailer to an additional wholesale discount compared to those retailers who did not engage in trade credit. The model is solved as follows.

The profit functions

and

for the manufacturer and retailer are defined as follows, respectively

Based on the assumed conditions, the expected profit function for a risk-neutral retailer can be given by

The profit utility function of risk-averse manufacturer is further given by

Then, adopt the inverse induction method to solve. We first take the second-order partial derivative of the expected profit function of the retailer

with respect to the sale price

in Eq. (18),we have

, indicating that

is a strictly concave function on

. Let the first partial derivative of the retailer’s expected profit function be 0, we get

Substituting Eq. (20) into Eq. (19), the Hessian matrix of Eq. (19) can be found as follows

Given that

, the Hessian matrix is negative definite when satisfying

, i.e.,

, there exists a unique optimal solution for

with respect to the strictly joint concave function of

.

By simultaneously solving the first-order conditions of the manufacturer's profit function with respect to the wholesale price of the product and the greenness of the product, and setting their first partial derivatives to 0, we can achieve the manufacturer's optimal decision under the available trade credit financing model.

Proposition 3. In a decentralized dual-channel green supply with trade credit financing, the optimal decisions of the manufacturer are as follows

Corollary 7. The degree of risk aversion in manufacturers with capital constraints who choose trade credit financing affects wholesale price, sale price, and the greenness of the product.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivative of Eq. (21) to Eq. (23) with respect to the manufacturer’s risk aversion

, we have

Due to , we have ,this shows that as the risk aversion coefficient of the manufacturer increases, the greenness of the product, wholesale price, and sale price all decrease.

Corollary 7 reveals that as a manufacturer's risk aversion increases, the manufacturer invests less in green R&D, which reduces the greenness of the product. At the same time, the manufacturer chooses to set lower wholesale price and sale price, thereby increasing demand and achieving a thinner profit margin, as a means to avoid unsold goods.

Corollary 8. Under the trade credit financing model, the optimal wholesale price, sale price, and the greenness of the product all increase as consumer preferences for green products increase.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivatives of Eq. (21) to Eq. (23) with respect to consumer green preference

, we have

Corollary 8 reveals that as consumer preferences for green products increase, manufacturers will produce more environmental protection products to meet the growing demand. Consequently, the greenness of the product will also rise. Simultaneously, the surge in green preference implies that consumers are willing to pay a premium for environmental protection products. Given that the development of green products entails additional costs, manufacturers tend to adjust their wholesale and sale price upward to cover these expenses and increase revenue.

Corollary 9. Under the trade credit financing model, when , both the optimal wholesale price of the product and its greenness increase with consumer channel preference.

Proof. Solve the first-order partial derivatives of Eq. (21) to Eq. (23) with respect to consumer channel preference

, we get

Corollary 9 indicates that as consumers' inclination towards online shopping, particularly for green products, rises, manufacturers adjust their strategies. This shift includes enhancing the green attributes of their products to attract online consumers. Moreover, manufacturers increase wholesale prices to offset the research and development costs associated with green products, thereby capitalizing on the potential for increased revenue.

4.3. Comparative Analysis of Decision-Making in the Two Financing Models

By solving for the two single financing models above, it is easy to obtain the wholesale price, greenness, and sale price of the manufacturer's products when the dual-channel manufacturer faces financial constraints by adopting different single financing methods, and the following conclusions can be drawn from this.

Proposition 4. When , ,we have .

Proof. When

, from Eq. (15) and Eq. (21), Eq. (16) and Eq. (22), and Eq. (17) and Eq. (23), we have

Because ,therefore , , .

Proposition 4 indicates that when the interest rates for bank loans and trade credit as equal, implying identical financing costs for the manufacturer across both financing modes, the capital-constrained manufacturer will select the financing mode that maximizes its own profit. Consequently, the manufacturer will make corresponding pricing and financing decisions. Under this circumstance of equivalent financing costs, the wholesale price, the greenness of the product, and sale price of the product are higher under the trade credit financing mode compared to the bank loan financing mode. Importantly, the relative difference in each decision remains consistent regardless of consumer online consumption preferences.

5. Numerical Analysis

In this section, we provide some numerical analyses to demonstrate the theoretical results. To illustrate the effects of the risk aversion, consumer green preference and consumer channel preference on the optimal pricing in both different financing models, some numerical experiments are carried out. Following Cai et al. (2019), it is assumed that the related parameters are as follows.

5.1. Impact of Level of Risk Aversion on Decision-Making

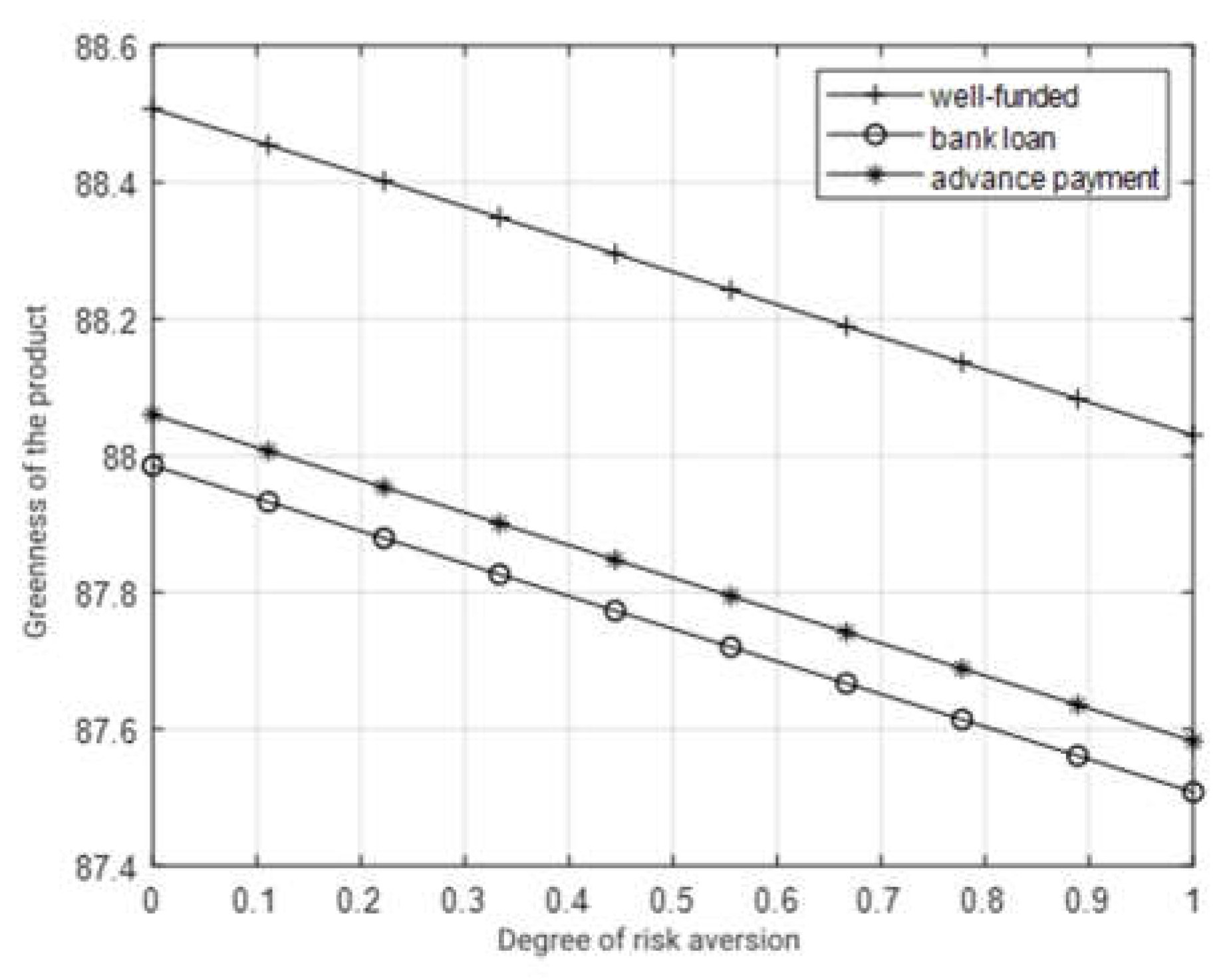

We first want to examine the effects of the level of risk aversion on the dual-channel green supply chain’s optimal decisions. Thus, we assume .Other parameters are kept unchanged in both cases and enable us to compare two cases.

Figure 3 illustrates the impact of the manufacturer's level of risk aversion on the greenness of the product. It can be observed that when the manufacturer exhibits risk aversion, the greenness of the product diminishes. The relationship between the manufacturer's risk aversion and the greenness of the product is inversely correlated, indicating that higher degrees of risk aversion correspond to lower levels of the greenness of the product. This phenomenon is understandable, as suppliers, demonstrate reduced tolerance towards market demand uncertainty, leading them to avoid market risks by decreasing the level of green inputs to minimize associated input costs. Furthermore, when comparing the greenness of the product under different financing modes while the manufacturer is risk averse, it is evident that the greenness of the product under the trade credit financing mode surpasses that under the bank loan financing strategy but falls below that of the unfunded situation. This suggests that when manufacturers face financial constraints, they tend to decrease their costs in green products, consequently diminishing the greenness of their products.

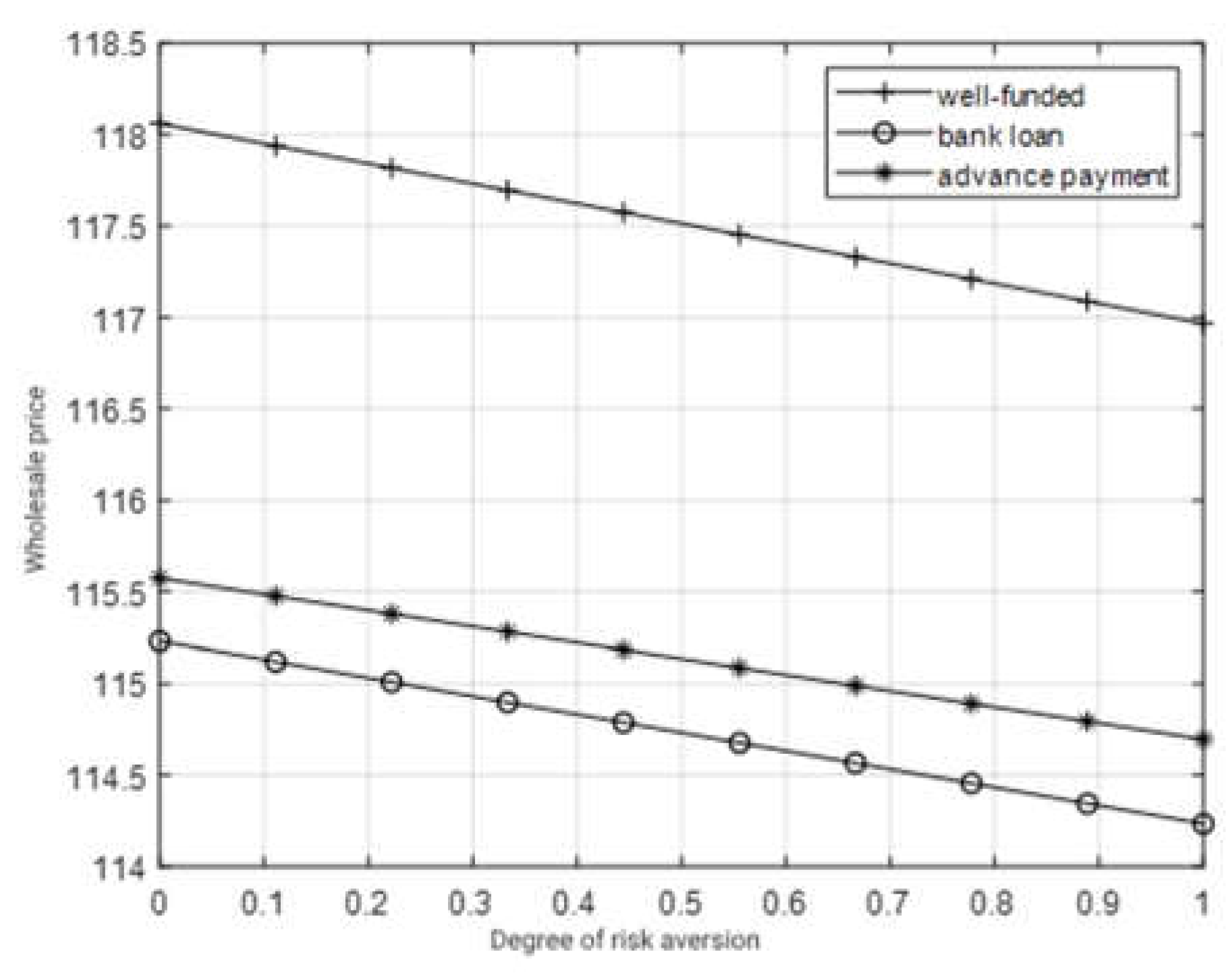

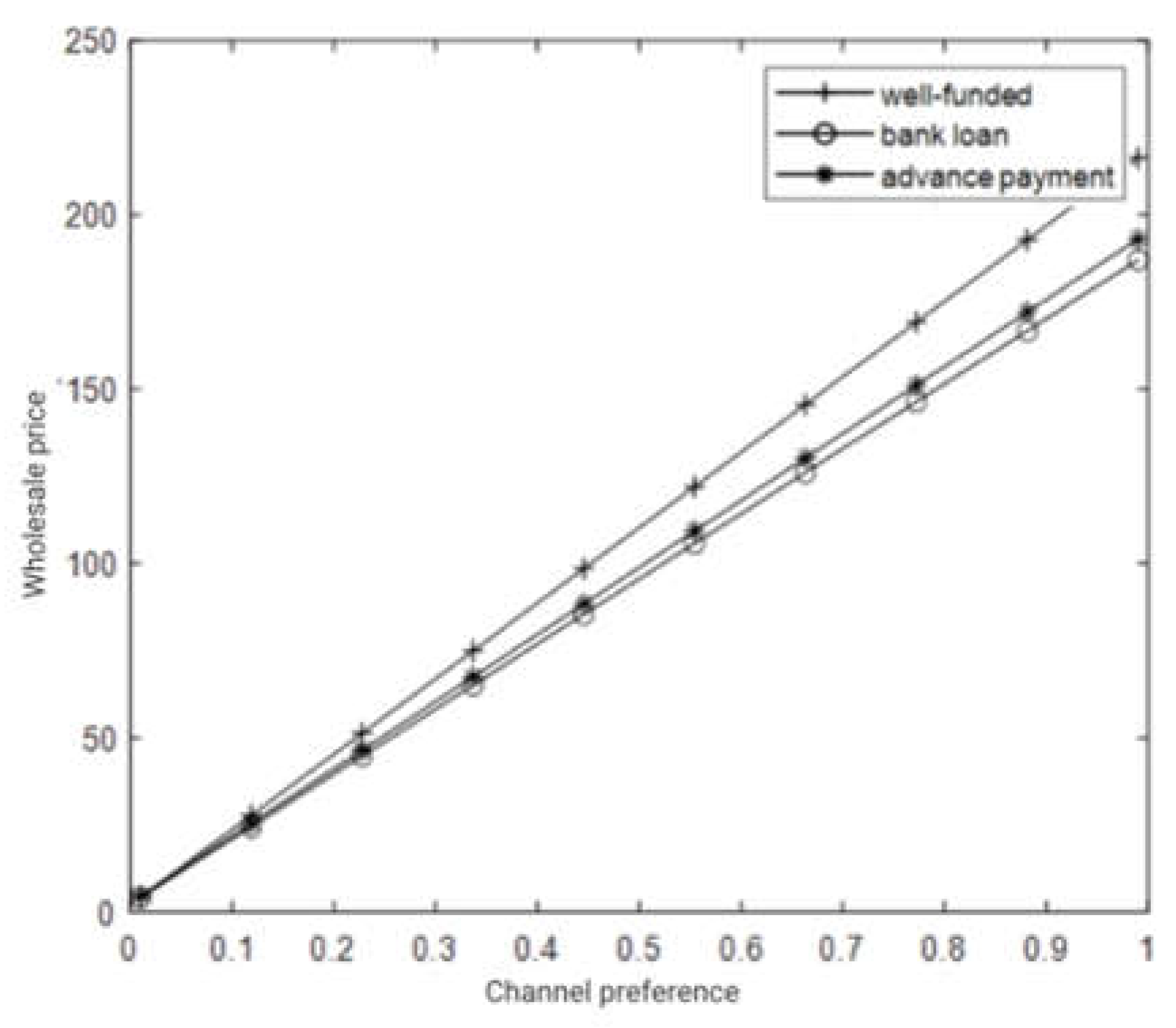

Figure 4 illustrates the impact of the degree of risk aversion on the wholesale price, revealing that the manufacturer's risk aversion leads to a decrease in the wholesale price. As observed in

Figure 3, the manufacturer's risk aversion reduces the greenness of the product, consequently lowering the wholesale price.

exhibits an inverse relationship with

, indicating that higher degrees of risk aversion correlate with lower wholesale price. Additionally, for further comparison, the wholesale price of the product in the trade credit financing mode is higher than that in the bank loan financing mode.

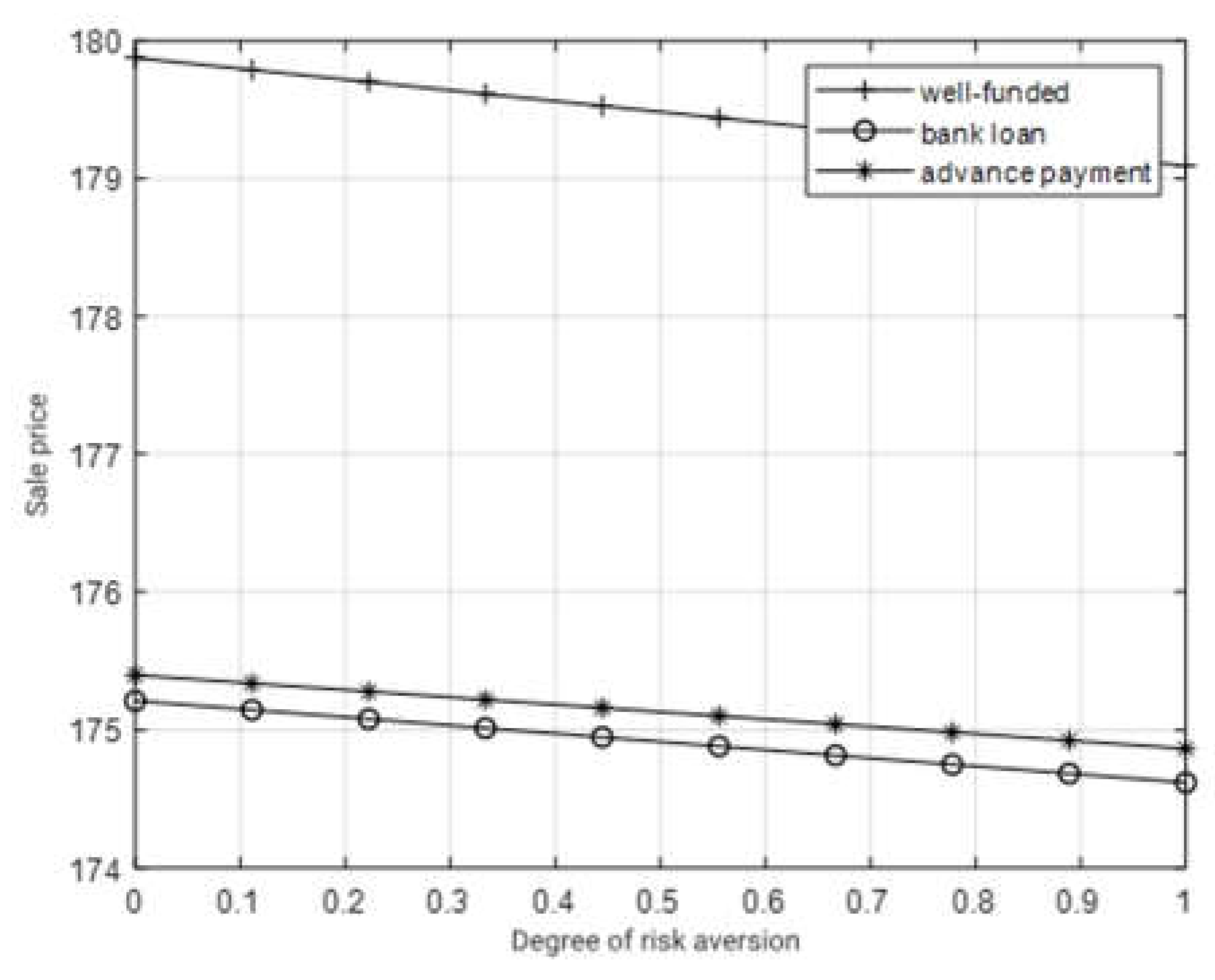

Figure 5 depicts the influence of risk aversion on the sale price, demonstrating that the manufacturer's risk aversion results in a reduction in the sale price.

is inversely proportional to

, suggesting that higher degrees of risk aversion correspond to lower sale price. When the manufacturer avoids market risks, as evidenced in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, they decrease green R&D expenses to lower the greenness of the product. Simultaneously, to boost market demand, the manufacturer chooses to reduce the sale price to promote both online and offline sales. Rational retailers similarly respond in kind.

5.2. Impact of Consumer Green Preference on Decision Making

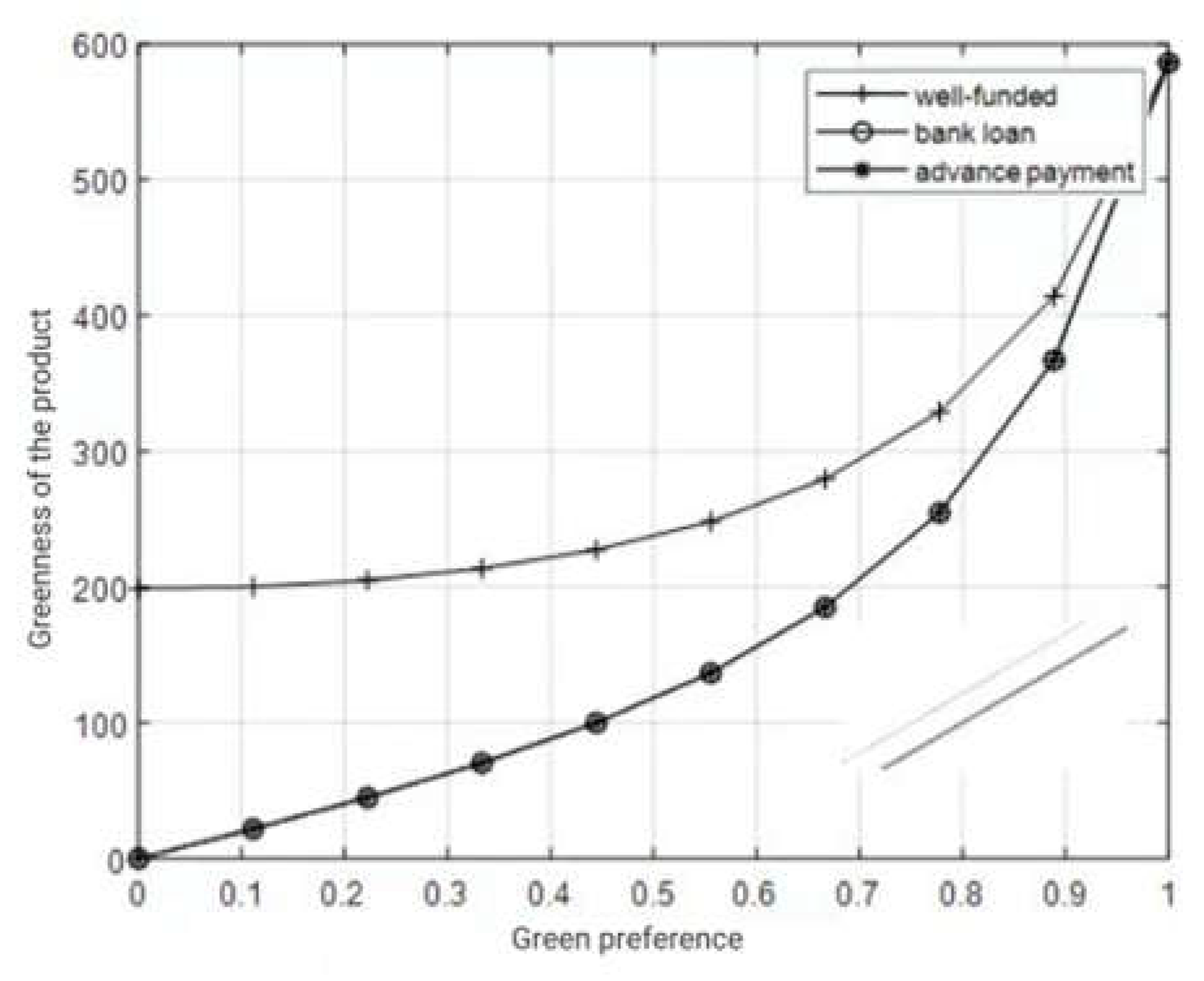

In this subsequent section, we are further interested in investigating the effects of consumer green preference on decision-making. We set and , while other parameters remain unchanged. Figures 6,7, and 8 respectively illustrate how the greenness of the product, wholesale price, and sale price vary with changes in consumer green preference.

Figure 6 illustrates the relationship between consumer green preference and the greenness of the product. It is apparent from the figure that as consumer green preference increases, so does the greenness of the product. However, regardless of the financing modes, the presence of financial constraints leads to lower the greenness of the product. This indicates a direct proportionality between the coefficient of consumer green preference and the greenness of the product. Consequently, a higher degree of consumer green preference for the product results in increased green inputs from supply chain members, thereby raising the overall greenness.

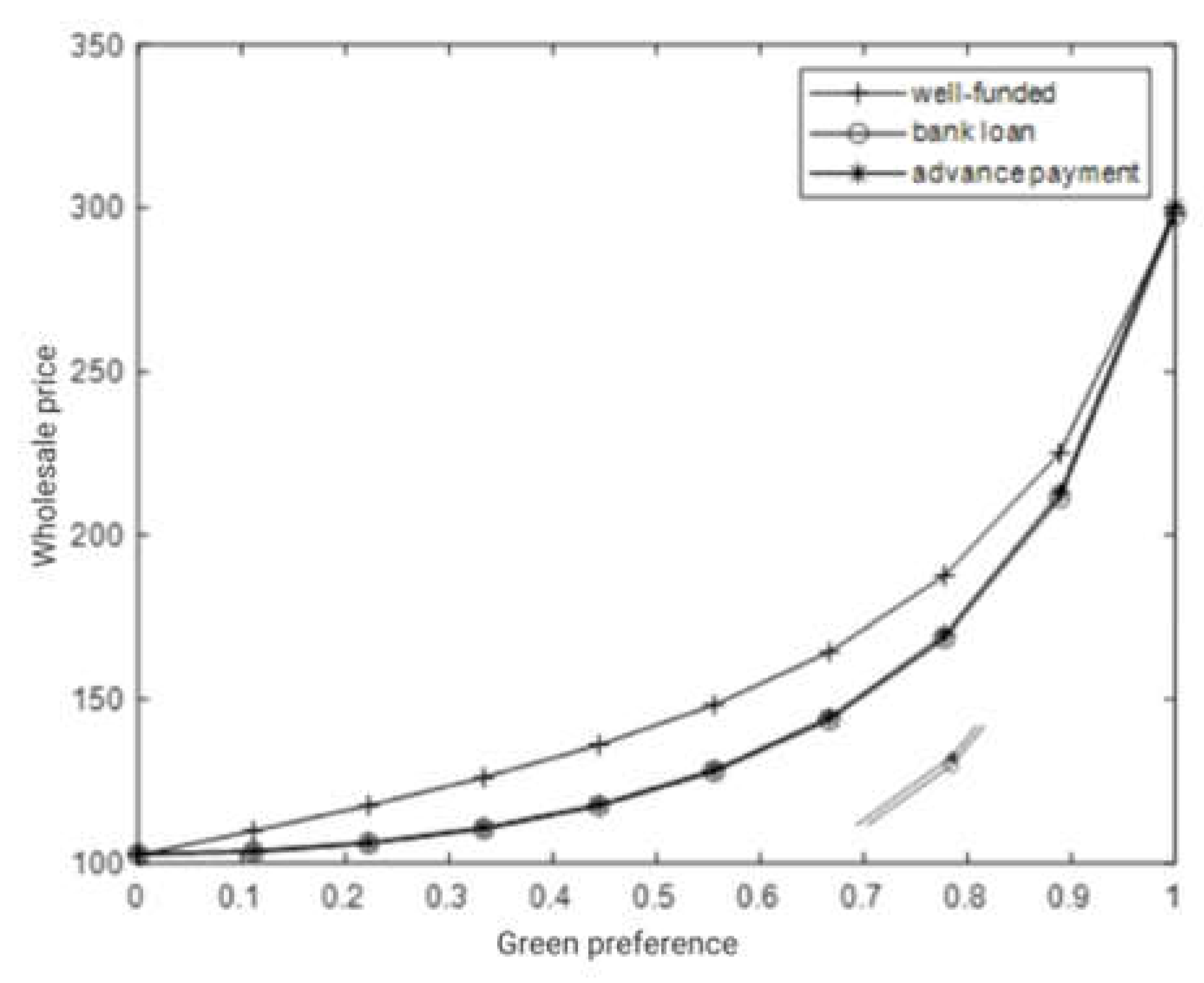

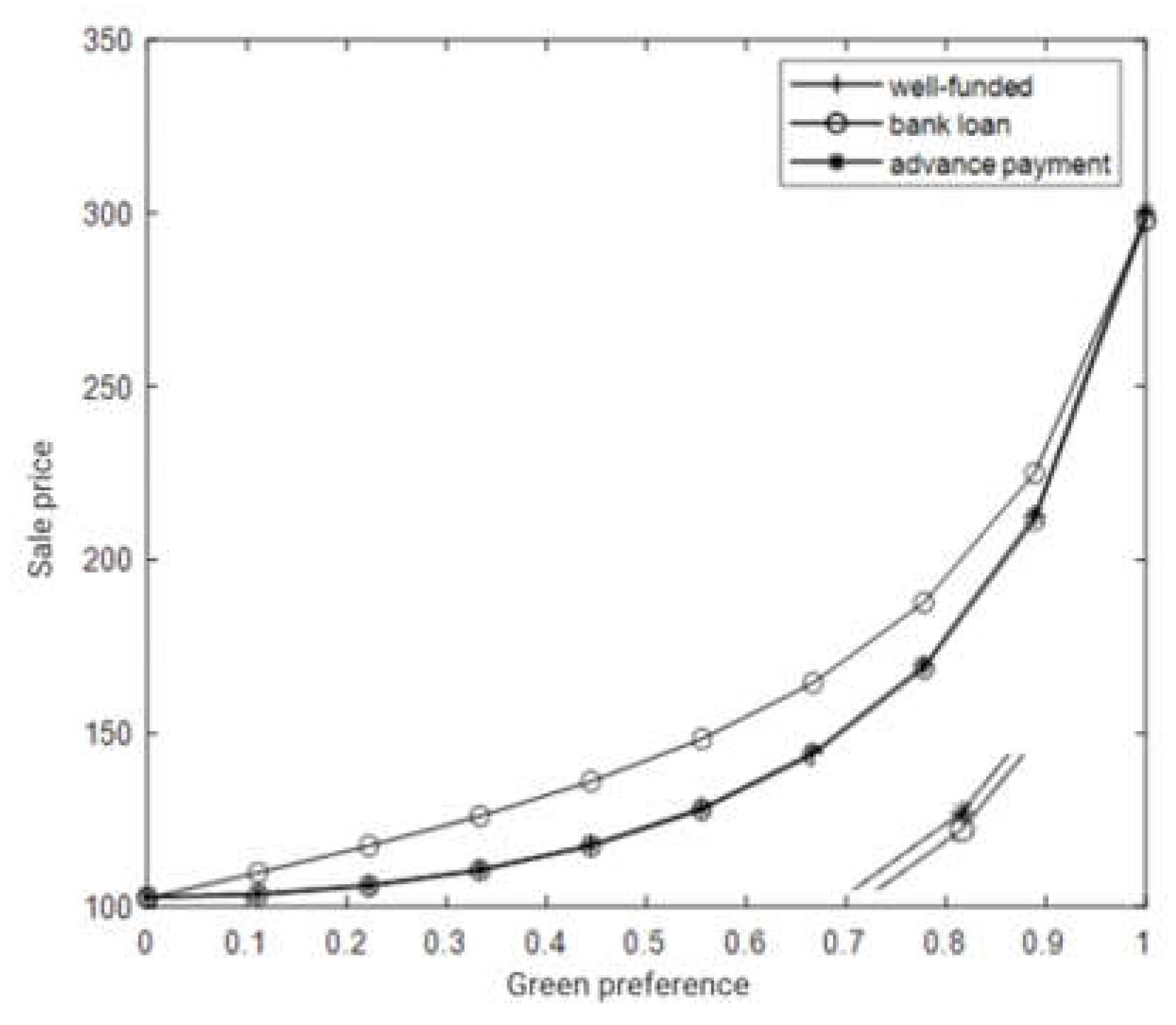

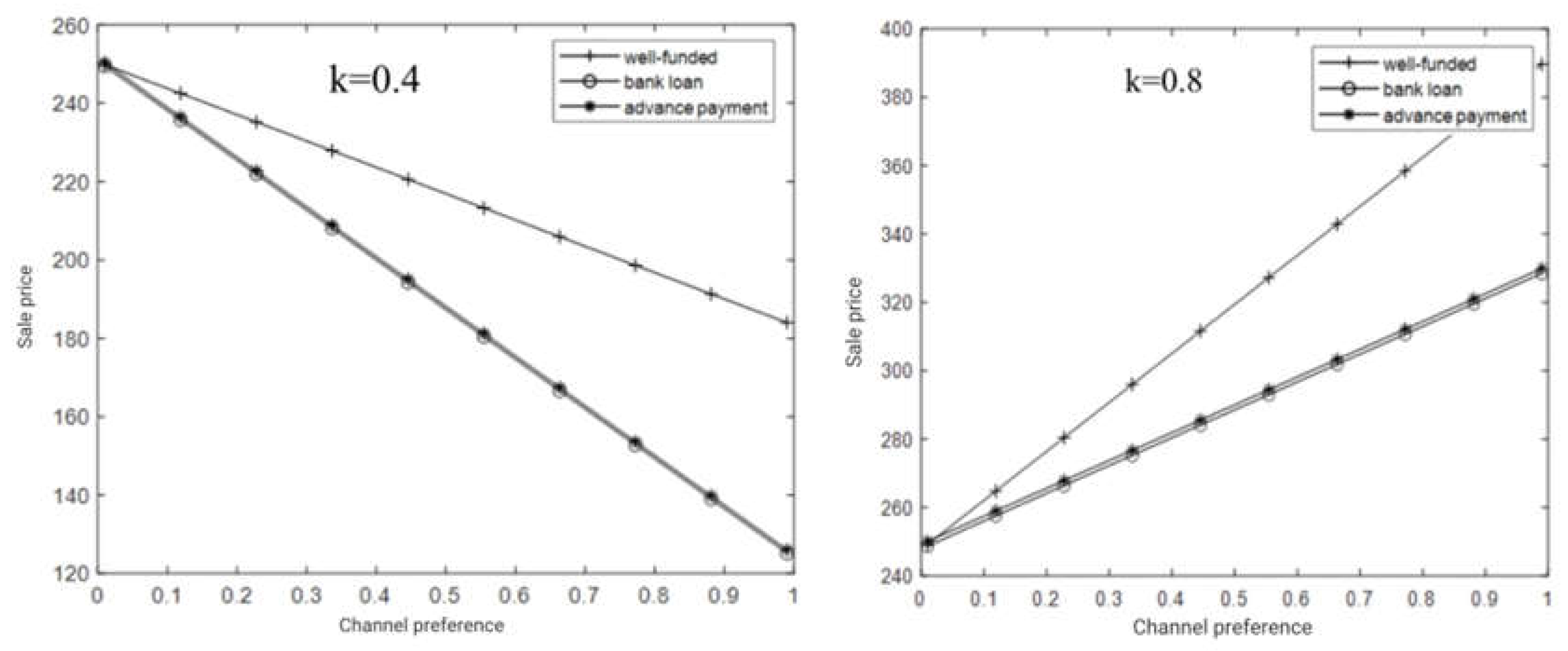

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 illustrate the effects of consumer green preference on the wholesale price and sale price, respectively. It is apparent from the figures that regardless of the financing mode and the presence of financial constraints, both the wholesale price and sale price of the product increase with higher levels of consumer green preference. This increase occurs at an accelerating rate, indicating positive impact of consumer green preference on product prices. This price escalation can be attributed to several factors. Firstly, in response to market demand for green products, manufacturers and retailers increase supply, which may entail additional investment in research and development, thereby raising production costs and the wholesale price of the product. Moreover, heightened demand for green products allows manufacturers and retailers to adjust prices to maximize profitability.

5.3. The Impact of Consumer Channel Preference on Decision Making

In this subsequent section, we delve into the impact of consumer channel preference on decision-making. With the risk aversion level set

and consumer green preference at

.

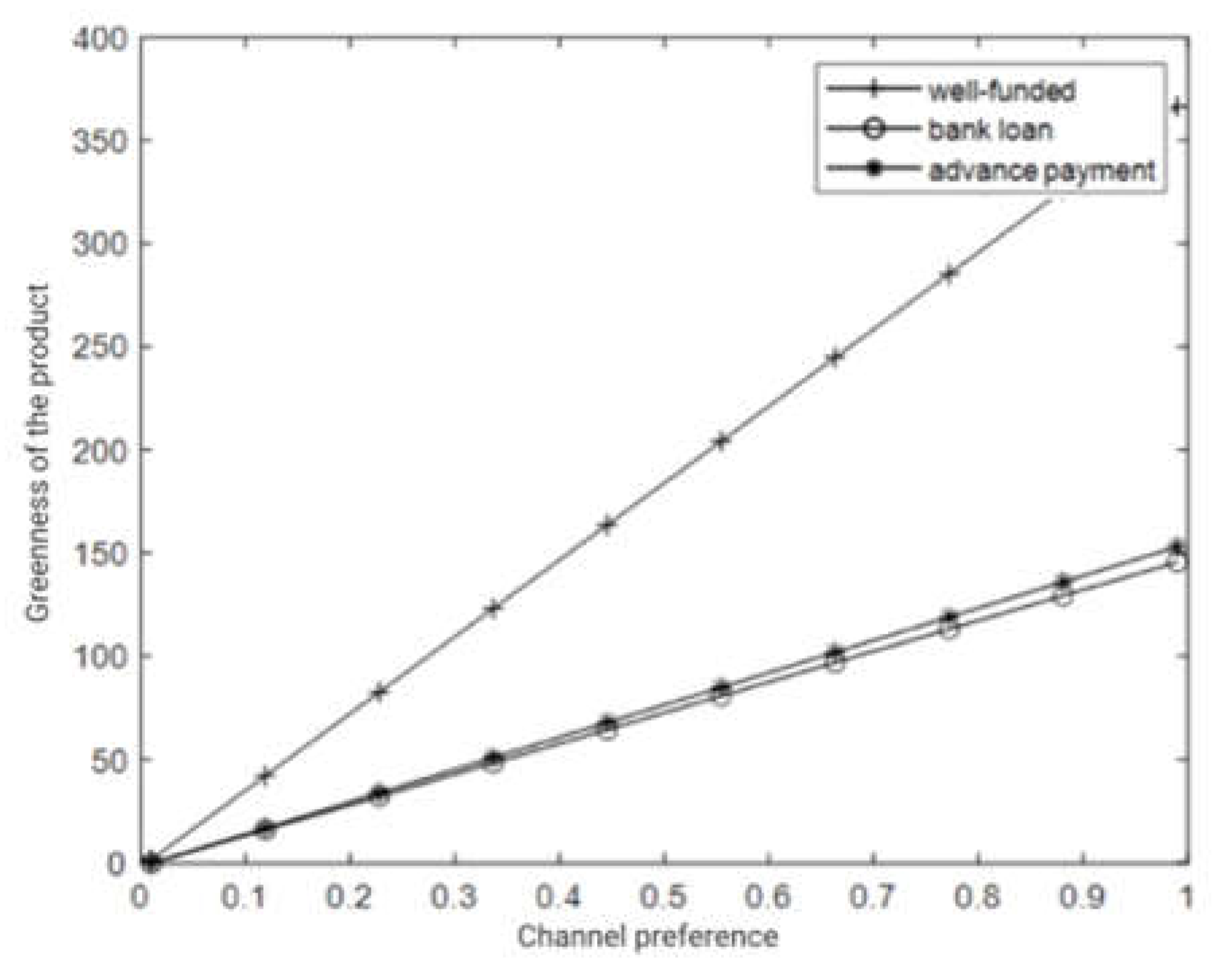

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 respectively depict how consumer channel preference influences the greenness of the product and wholesale price.

Figure 11 illustrates the variations in product sale price based on changes in consumer channel preference across different levels of consumer green preference.

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 demonstrate a positive correlation between the greenness of the product, its wholesale price, and consumer channel preference, regardless of financial constraints and financing modes. In other words, stronger consumer channel preference leads to increase the product and its wholesale price. However, when financial constraints are present, both the greenness of the product and its wholesale price are lower compared to scenarios without such constraints. In response to consumer preference for online channels, which drives demand for green products, manufacturers intensify research and development efforts and increase production to meet online demand. This results in a rise in the greenness of the product. Simultaneously, increased demand through online channels leads to a reduction in offline purchases. To address this shift, manufacturers decrease offline retailer purchases by raising wholesale price, thereby catering to more offline retailers. Consequently, manufacturers increase wholesale price to reduce offline retailers' purchasing volumes and meet the growing demand for online direct sales channels.

Figure 11 illustrates the impact of consumer channel preference on sale price. Sale price of products show a negative correlation with consumer online preference when their green preference is low, and a positive correlation when their green preference is high. When consumers prioritize price over green attributes, especially through offline channels, manufacturers lower prices to attract this segment of consumers to online shopping, thus increasing sales volume. Conversely, when consumers highly value eco-friendly products, manufacturers primarily sell green products online. As consumers' online preference grows, manufacturers set higher prices for green products sold online to cater to this demand and attract environmentally conscious consumers.

6. Conclusion

This paper investigates the pricing and financing decisions in a dual-channel green supply chain with one capital-constrained manufacturer and one retailer. We discuss how to achieve the optimal decisions when two different financing methods are adopted. We further construct the incorporating adequate funding, bank loans, and trade credit models. After that we analyze and compare pricing decisions under different modes and discuss the impact of risk aversion and consumer preferences on equilibrium outcomes, supplemented with numerical examples.

First, we find that in a dual-channel green supply chain, manufacturers' risk aversion behavior significantly affects the environmental sustainability level of the supply chain, resulting in a reduction in the greenness of the product, wholesale price, and sale price. Specifically, wholesale price, sale price, and the environmental sustainability of products all decrease with increasing degrees of risk aversion. This implies that to mitigate losses, risk-averse manufacturers typically adopt lower wholesale pricing strategies and attract consumers by reducing sale price to increase sales volume.

Second, we comparatively analyze the two strategies of bank loan financing and trade credit financing. The results show that when manufacturers face financial constraints, the greenness of the product, wholesale price, and sale price all increase in response to consumer green preference, regardless of whether bank loan financing or trade credit financing strategies are adopted. However, decisions made under the trade credit financing strategy result in higher levels of greenness, wholesale price, and sale price compared to those made under bank loan financing. This suggests that internal financing through trade credit is superior to external financing through bank loans and helps reduce unnecessary losses in the supply chain.

Finally, we analyze the impact of consumer preferences on the equilibrium outcomes of financing strategies. The paper suggests that as consumer channel preference increase, wholesale prices and product greenness also rise. When consumer green preference is low, sale price is directly proportional to channel preferences. Conversely, when consumer green preference is high, sale price is directly proportional to channel preference. This indicates that sale price is influenced by both consumer green preference and channel preference. Therefore, manufacturers need to consider both factors when making decisions. Furthermore, all parties in the supply chain should carefully take into account each member's risk preference when making pricing and other strategic decisions to achieve more favorable outcomes.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant Nos. (72061007,71961004, 71461005), Social Science Fund of Jiangsu Province under Grant No 22GLB009, Philosophy and Social Science University of Jiangsu Province under Grant No.2022JSZD064, Science Foundation of Suzhou University of Science and Technology Grant Nos.(332111807, 332111801).

References

- Cai, J., Lin, H., &Hu, X. (2022). Green supply chain game model and contract design: risk neutrality vs. risk aversion. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 29(34), 51871-51891.

- Cao, E.; Du, L.; Ruan, J. Financing preferences and performance for an emission-dependent supply chain: Supplier vs. bank. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2019, 208, 383–399,. [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Mei, Y. Green Supply Chain Decision and Management under Manufacturer’s Fairness Concern and Risk Aversion. Sustainability 2022, 14, 16006–16026,. [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, P.; Mou, J. Coordination mechanism for a remanufacturing supply chain based on consumer green preferences. Supply Chain Forum: Int. J. 2023, 24, 406–427,. [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Tang, W.; Song, M. Low-carbon production with low-carbon premium in cap-and-trade regulation. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 134, 652–662,. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; He, J.; Lei, Q. Coordination in a retailer-dominated supply chain with a risk-averse manufacturer under marketing dependency. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 27, 3056–3078,. [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. Carbon emission reduction decisions in the retail-/dual-channel supply chain with consumers' preference. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 852–867,. [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Lu, T.; Zhang, J. Financing strategy selection and coordination considering risk aversion in a capital-constrained supply chain. J. Ind. Manag. Optim. 2022, 18, 1220–1246,. [CrossRef]

- Ke, H.; Wu, Y.; Huang, H. Competitive Pricing and Remanufacturing Problem in an Uncertain Closed-Loop Supply Chain with Risk-Sensitive Retailers. Asia-Pacific J. Oper. Res. 2018, 35, 185003–185023. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-J.; Han, S.M. Uncovering the reasons behind consumers’ shift from online to offline shopping. J. Serv. Mark. 2023, 37, 1201–1217,. [CrossRef]

- Kouvelis, P.; Zhao, W. Supply Chain Contract Design Under Financial Constraints and Bankruptcy Costs. Manag. Sci. 2016, 62, 2341–2357,. [CrossRef]

- Kouvelis, P.; Zhao, W. Who Should Finance the Supply Chain? Impact of Credit Ratings on Supply Chain Decisions. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2018, 20, 19–35,. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Zhu, M.; Jiang, Y.; Li, Z. Pricing policies of a competitive dual-channel green supply chain. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 2029–2042,. [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Wu, H.; Xiao, S. Financing strategies for a capital-constrained manufacturer in a dual-channel supply chain. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2020, 27, 2317–2339,. [CrossRef]

- Mazaheri, E.; Richard, M.-O.; Laroche, M. Online consumer behavior: Comparing Canadian and Chinese website visitors. J. Bus. Res. 2011, 64, 958–965,. [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Li, M.; Liu, W.; Li, Z.; Zhang, J. Pricing policies of dual-channel green supply chain: Considering government subsidies and consumers' dual preferences. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2021, 26, 1021–1030,. [CrossRef]

- Ngoh, C.-L.; Mellema, H.N. B2C multi- to single-channel: the effect of removing a consumer channel preference on consumer retailer and channel choice. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2024, 39, 53–65,. [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Liu, L.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, W. Optimal Operation Strategies under a Carbon Cap-and-Trade Mechanism: A Capital-Constrained Supply Chain Incorporating Risk Aversion. Math. Probl. Eng. 2020, 2020, 1–17,. [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Han, Y.; Wei, G.; Xia, L. The value of advance payment financing to carbon emission reduction and production in a supply chain with game theory analysis. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2020, 58, 200–219,. [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, K.; Yavari, M. Pricing policies for a dual-channel green supply chain under demand disruptions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2019, 127, 493–510,. [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.S.; Yang, S.A.; Wu, J. Sourcing from Suppliers with Financial Constraints and Performance Risk. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2018, 20, 70–84,. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhou, X.; Li, B. Pricing strategy of dual-channel supply chain with a risk-averse retailer considering consumers’ channel preferences. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 309, 305–324,. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Sethi, S.P.; Liu, M.; Ma, S. Coordinating contracts for a financially constrained supply chain. Omega 2017, 72, 71–86,. [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Tang, H.; Lin, Z.; Lu, J. Pricing and sales-effort analysis of dual-channel supply chain with channel preference, cross-channel return and free riding behavior based on revenue-sharing contract. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2022, 249, 108506–108625. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Birge, J.R. Operational Decisions, Capital Structure, and Managerial Compensation: A News Vendor Perspective. Eng. Econ. 2008, 53, 173–196,. [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; He, X.; Liu, Y. Financing the capital-constrained supply chain with loss aversion: Supplier finance vs. supplier investment. Omega 2019, 88, 162–178,. [CrossRef]

- Yan, N., Yu, X., Zhong, H., & Xu, X. (2020). Loss-averse retailers’ financial offerings to capital-constrained suppliers: loan vs. investment. International Journal of Production Economics, 227, 107665-107687.

- Yang, H.; Zhuo, W.; Shao, L. Equilibrium evolution in a two-echelon supply chain with financially constrained retailers: The impact of equity financing. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 185, 139–149,. [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, Q.; Ji, J. Pricing and carbon emission reduction decisions in supply chains with vertical and horizontal cooperation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2017, 191, 286–297,. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.A.; Birge, J.R. Trade Credit, Risk Sharing, and Inventory Financing Portfolios. Manag. Sci. 2018, 64, 3667–3689,. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; You, J. Consumer environmental awareness and channel coordination with two substitutable products. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2015, 241, 63–73,. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hezarkhani, B. Competition in dual-channel supply chains: The manufacturers' channel selection. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2021, 291, 244–262,. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chan, C.K.; Wong, K.H. A multi-period supply chain network equilibrium model considering retailers’ uncertain demands and dynamic loss-averse behaviors. Transp. Res. Part E: Logist. Transp. Rev. 2018, 118, 51–76,. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sethi, S.P.; Choi, T.; Cheng, T. Pareto optimality and contract dependence in supply chain coordination with risk-averse agents. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2022, 31, 2557–2570,. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).