1. Introduction

Fermented foods have a long history and have been developed in various ways around the world, but Korean fermentation is unique in that it is a natural fermentation using complex bacteria. The typical starter for spontaneous fermentation is nuruk, which involves complex microorganisms such as bacteria, yeast, and fungi [

1]. The first time nuruk (Japanese: koji, Chinese: Jiuqu) appears in historical records is in the ‘Offices of Summer and Minister of War’ chapter of the ‘Rites of Zhou’ compiled by the Chinese Zhou dynasty in the 2nd century BC. Here, it is recorded that thinly sliced meat was dried in the sun, mixed with salt and nuruk, and aged in jars for 100 days to produce a liquor [

2,

3,

4]. The nuruk used was made from sorghum (millet). The discovery of this nuruk was a monumental event in East Asian food culture, as this fermentation technique became the cornerstone of later fermented food cultures.

Even today, fermented foods such as makgeolli, vinegar, ganjang (soy sauce), soju, and sake are made using nuruk, a complex of microorganisms, as a starter. The reason for using nuruk as a fermentation starter is to produce amylase, a saccharification enzyme secreted by the microbial complex. There are many forms of nuruk, but in the case of makgeolli, a traditional Korean alcoholic beverage, it is usually made from ground wheat and rice [

5,

6]. It is when they are properly kneaded and agglomerated into a disc-shaped lump, which is then suspended in natural air, that the microorganisms that produce starch-degrading enzymes are cultivated. Since there are countless spores of microorganisms floating in the air, the temperature and humidity can be controlled to selectively cultivate the dominant species and create a stable nuruk [

7,

8]. As a volcanic island with little fertile farmland and limited access to the mainland, Jeju Island had to rely on food produced on the island itself, so its fermentation culture is quite different from that of the mainland. As a prime example of this, the nuruk is made from barley grown on the island, as opposed to the rice and wheat produced on the mainland [

9,

10].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) generates large numbers of sequences at an unprecedented rate. Amplicon analysis is commonly used to study the microbiome and has been used in large-scale projects, including the Human Microbiome Project [

11,

12]. The 16S rRNA gene, which is used to analyze these microbial communities, is highly conserved among bacteria and is commonly used to distinguish bacteria at the taxonomic level, while internal transcribed spacers (ITSs) in nuclear ribosomal DNA are commonly used in fungal studies [

13,

14]. Advances in NGS technology are enabling researchers to study and understand the microbial world from a broader and deeper perspective, and indeed, many studies have applied NGS technology to examine the microbiomes of fermented foods such as cheese, kimchi, and sausages. Even now, NGS technology is advancing at a rapid pace, continually improving in terms of quality and cost, and is having a major impact on a wide range of disciplines, including food microbiology [

15,

16,

17,

18].

Stevia rebaudiana, commonly known as stevia, is a plant native to South America and is known for containing natural sweetening compounds called steviol glycosides; stevioside and rebaudioside A are the most abundant, and these glycosides are much sweeter than sucrose but contain no calories, making stevia an attractive natural sweetener for people who are trying to reduce their calorie intake or manage their blood sugar levels. They are often used as a natural sweetener to replace sugar in the manufacturing of a variety of foods and beverages. Steviol is the parent of the diterpene compounds found in the leaves of Stevia rebaudiana, acting as a precursor to a variety of steviol glycosides that are responsible for the plant’s intense sweetness, including stevioside, rebaudioside A, rebaudioside O, and dulcoside A [

19,

20,

21].

This study aimed to evaluate the antioxidant, antiobesity, and anti-inflammatory properties of stevia leaves, which are famous as a natural sweetener, by fermenting them using barley yeast, a traditional fermentation starter on Jeju Island, and to identify changes in microbial communities as well as metabolites during the fermentation process. Additionally, for application on human skin, the study also conducted a human skin primary irritation test in accordance with the ethical principles of medical research under the Declaration of Helsinki.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The tryptic soy broth (TSB) medium and sucrose used for stevia fermentation were purchased from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA) and Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd. (St. Louis, MO, USA), respectively, and the fermentation starter, barley nuruk, was purchased from Dongmun Traditional Market, Jeju Island, Korea. The 2,2-disphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl, 2,2-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulphonic acid) diammonium salt, potassium persulfate, and L-ascorbic acid used in the antioxidant capacity assay were from Sigma-Aldrich Co., Ltd. (St. Louis, MO, USA). The α-glucosidase, sodium phosphate, pNPG, Na2CO3, and acarbose used for antiobesity measurements were from Sigma-Aldrich Co, Ltd. (St. Louis, MO, USA). Murine macrophage RAW 264, used for anti-inflammatory capacity experiments, was purchased from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea); lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli and modified Griess reagent were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT); dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was purchased from Biosesang (Seongnam, Gyeonggi-do, Korea); Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) and penicillin–streptomycin were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA); and fetal bovine serum (FBS) was purchased from Merck Millipore (Burlington, MA, USA). All reagents used were of the highest-quality analytical grade. The instruments used in this experiment were an ELISA reader (Epoch, Biotech Instruments, Vermont IL, USA), a freeze dryer (Ilshin, Korea), a microscope (Olympus Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), a rotary vacuum evaporator (EYELA N-1210B, Sunil Eyela Co., Ltd., Sungnam, Korea), a digital reciprocating shaker (Daihan Scientific Co., Ltd., Gangwon, Korea), and a humidified incubator (NB-203XL, N-BIOTEK, Inc., Bucheon, Korea).

2.2. Preparation of Stevia Ferments and Extracts

Fermentation broth and extract were prepared using organically grown stevia leaves from Jeju Cacao Smart Farm as follows: 10 g of barley nuruk and 10 g of stevia ethanol extract were added to 100 mL of TSB medium or sucrose solution and fermented in an incubator at 30 degrees for 1, 3, and 5 days, and 100 mL of acetone was then added to each fermentation broth to prepare a 50% acetone extract, which was extracted for 24 hours at room temperature, concentrated under reduced pressure, and lyophilized.

2.3. Antioxidant Capacity

The antioxidant capacity of the stevia ferment was tested using 1,1, diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) and ABTS free radical scavenging assays as follows: DPPH· is itself a very stable free radical and has a purple color. When DPPH· reacts with substances with antioxidant activity, it turns yellow as the radical is scavenged; therefore, the degree of radical scavenging can be measured spectrophotometrically to indirectly assess the antioxidant capacity of the sample. DPPH radical scavenging activity was measured by applying the Munteanu method [

22]. Then, 20 μL of the extract of each concentration of stevia ferment was incubated with 180 μL of 0.2 mM DPPH solution for 10 min, and the absorbance was measured at 515 nm. On the other hand, when ABTS

+, which is blue-green in color, reacts with substances with antioxidant activity, it is decolorized by scavenging radicals, and the degree of radical scavenging can be measured spectrophotometrically to indirectly evaluate the antioxidant capacity of the sample. ABTS radical scavenging activity was measured by applying the method of Re et al. Prior to the antioxidant capacity measurement, an ABTS

+ solution was prepared by mixing 14 mM ABTS and 4.9 mM potassium persulfate and diluted with 95% EtOH to 0.65-0.70 at 700 nm after 24 h of dark reaction. The antioxidant capacity was measured by adding 180 μL of ABTS

+ solution to 20 μL of the extract of each concentration of stevia ferment and dark reacting for 15 min and then measuring the absorbance at 700 nm. Ascorbic acid was used as a positive control for DPPH and ABTS radical scavenging activity. IC

50 values (concentration of sample required to inhibit 50% of DPPH radicals) were estimated from a regression analysis. Based on these IC50 values, the antioxidant capacity was evaluated.

2.4. Antidiabetic Capacity

The antidiabetic capacity of the stevia ferment was tested using an α-glucosidase inhibition assay as follows: The inhibition of the α-glucosidase enzyme was measured in a 100 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH of 6.8, by reacting 750 mU/mL α-glucosidase with 100 μL of 1.5 mM pNPG in the absence or presence of stevia ferment at 37°C in a final reaction volume of 200 μL. The reaction in the presence of acarbose was used as a positive control. The reaction was initiated by adding pNPG, and after a reaction time of 10 min, 60 μL of a stop solution, 1 M Na2CO3, was added and the released pNPs were determined by measuring the absorbance at 405 nm using a spectrophotometer. For accurate inhibitory activity measurements, background readings were removed by subtracting the absorbance of the α-glucosidase-free mixture. Inhibition assays (using different concentrations of inhibitor) were also used to determine the concentration of stevia ferment that resulted in 50% inhibition (IC50 value) compared to acarbose. All measurements were performed in triplicate.

2.5. Anti-Inflammatory Capacity

The anti-inflammatory activity of the stevia ferment was tested using RAW 264.7 cells, a macrophage line. RAW 264.7 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s minimal essential medium (DMEM) with 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 25% F-12 nutrient at 37°C, 5% CO2 in a humidified chamber, and passaged every 2 days. Cell viability was assessed by a 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as follows: RAW 264.7 cells were seeded at 1.5 x 105 cells/mL in 24-well plates and incubated for 24 hours, then treated with stevia ferment in a concentration-wise manner and incubated for 24 hours. After 24 hours of incubation, 400 µL of an MTT solution (0.4 mg/mL) was treated and reacted for 4 hours, and the cytotoxicity was measured. The cell culture supernatant treated with the MTT solution was removed, and the formed non-aqueous formazan precipitate was completely dissolved by adding DMSO, and the absorbance at 570 nm was measured using a microplate reader. The cytotoxicity was determined by comparing the absorbance values with the untreated sample. The inhibition of nitric oxide production was measured by measuring the amount of NO as nitrite or nitrate in the supernatant of the cells. Cell line RAW 264.7 was seeded in 96-well plates at 1×104 cells/well and incubated in an incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 hours. The cultures were then exchanged to a serum-free DMEM medium and treated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) to induce an inflammatory response. Ultimately, the cultures were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) and the respective stevia fermentations by concentration and incubated in an incubator at 37°C, 5% CO2 for 24 h. Then, 100 μL of the cell culture was transferred to a fresh 96-well plate, 100 μL of Griess reagent was added, the reaction was carried out for 10 min at room temperature, and the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using an ELISA reader.

2.6. Qualitative Analysis of the Stevia Ferments

UPLC analysis was performed using a UPLC-Q-TOF MS (Vion, Waters, Milford, MA, USA) and PDA Primaide detector (Waters, USA), with an Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (2.1 mm × 100 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters). The mobile phase consisted of water containing 0.1% formic acid (v/v, A) and 0.1% acetonitrile (B) with gradient elution: 0–2 min, 90%–75% A; 2–3 min, 75%–65% A; 3–4 min, 65%–50% A; 4–5.5 min, 50%–45% A; 5.5–7.5 min, 50%–45% A; and 7.5–10 min, 45%–35% A. The flow rate was 0.35 mL/min and 1 μL of stevia ferments was injected. The ESI source was operated in negative ionization mode with a capillary voltage of 2.5 kV, and the cone voltage was set to 20 V. The desolvation temperature was set at 400 ◦C. The desolvation gas flow rate was 900 L/h. The full-scan range of MS data acquisition was 50–1500 m/z. LockSpray and data acquisition software was leucine-encephalin (554.2615 Da) and UNIFI version 1.9.2.045 (Waters), respectively.

2.7. Amplification and Sequencing

After the above, 16S rRNA amplicons for sequencing were prepared by using a Herculase II Fusion DNA Polymerase Nextera XT Index Kit V2 for MiSeq System (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) as follows. First, DNA was extracted from the stevia ferment, quality control (QC) was performed, and libraries were constructed with the validated samples. The sequencing library was constructed by the random fragmentation of DNA samples followed by the ligation of 5′ and 3′ adapters, and then the adapter-ligated fragments were PCR-amplified and gel-purified. Next, microbial community analysis was performed by sequencing the templates with Illumina SBS technology with distinct clone clusters generated.

2.8. Human Skin Irritation Test

The primary human skin irritation test of six extracts of stevia ferment was conducted in accordance with the Korean Ministry of Food and Drug Safety (MFDS), Personal Care Products Council (PCPC) guidelines, and the standard operating procedure of Dermapro Inc. (SOP). After 24 h of application of 1 mg concentration of the test product prepared with squalane on the back of the test subjects using Van der Bend, the test product was removed and observed after 20 min and 24 h, and the evaluation criteria were evaluated according to PCPC guidelines. The skin reaction results for each test substep were calculated according to the following formula:

2.10. Statistical Analyses

All the experiment results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using Student’s t-tests or a one-way ANOVA using IBM SPSS (v. 20, SPSS Inc., Armonk NY, USA). p-values < 0.05 (*), 0.01 (**), or 0.001 (***) were marked as statistically significant.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Antioxidant and Antidiabetic Capacity of Stevia Ferments

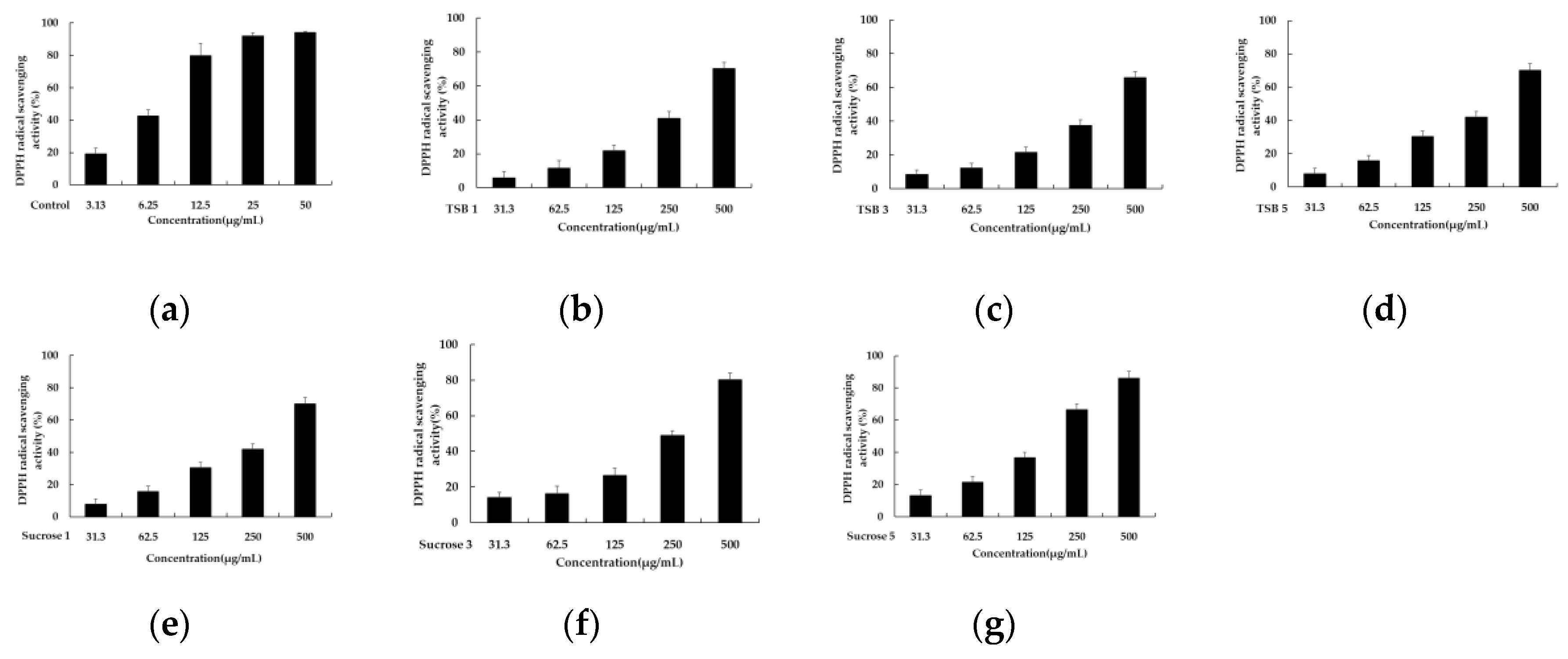

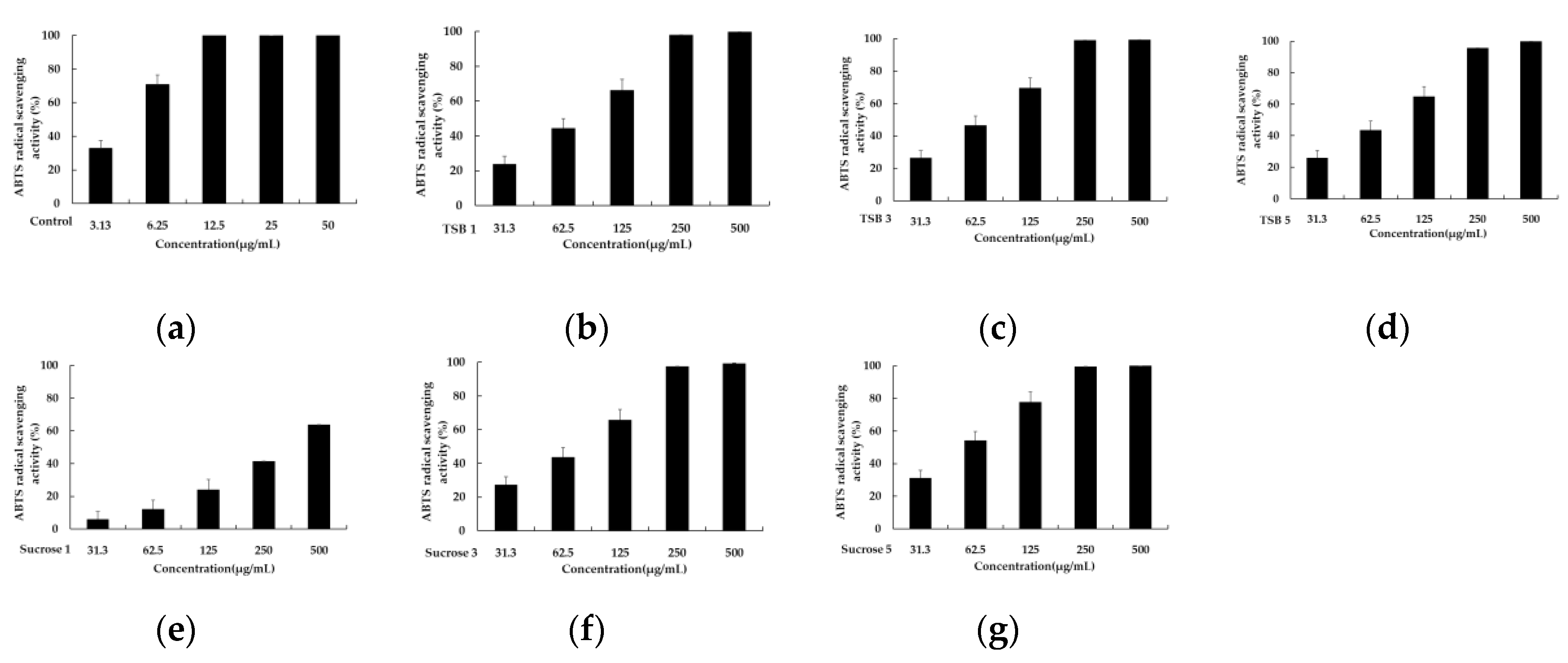

To assess the antioxidant capacity of single substances and complexes, various assays have been developed based on the ability of redox molecules to neutralize free radicals. Among these, ABTS and DPPH assays are widely utilized. These assays employ spectrophotometric measurements, each employing a distinct mechanism with which to evaluate antioxidant activity. The DPPH assay relies on antioxidants donating hydrogen atoms to scavenge DPPH radicals, leading to a color change from purple to yellow. Conversely, the ABTS assay measures antioxidant capacity by assessing the reduction of the ABTS radical cation by antioxidants, resulting in a color change from cyan to colorless. Both methods are popular due to their simplicity, speed, and sensitivity in assessing the antioxidant properties of substances. Differences in the wavelengths used to monitor radical depletion, such as 515 nm for DPPH and 700 nm for ABTS, contribute to variations in antioxidant activity assessment [

22,

23]; therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the antioxidant capacity of stevia leaf extracts fermented with barley nuruk using TSB and sucrose through ABTS and DPPH assays. Six 50% acetone extracts of stevia ferments obtained after incubation for 1, 3, and 5 days were tested at concentrations of 500, 250, 125, 62.5, and 31.25 μg/mL. As depicted in

Figure 1, fermentations with sucrose solution exhibited relatively superior antioxidant capacity compared to those with TSB, with respective IC

50 values of 914.44 ± 91.51 μg/mL, 256.56 ± 23.67 μg/mL, and 174.38 ± 16.11 μg/mL for DPPH scavenging. Additionally, the DPPH radical scavenging ability improved as the fermentation progressed. Consistent with the DPPH scavenging results, the comparison of antioxidant capacity, using an ABTS assay, also demonstrated the superiority of stevia fermentation with sucrose. The corresponding IC

50 values were 340.02 ± 46.33 μg/mL, 80.88 ± 6.49 μg/mL, and 57.98 ± 6.93 μg/mL, respectively, with ABTS radical scavenging capacity increasing as fermentation progressed (

Figure 2).

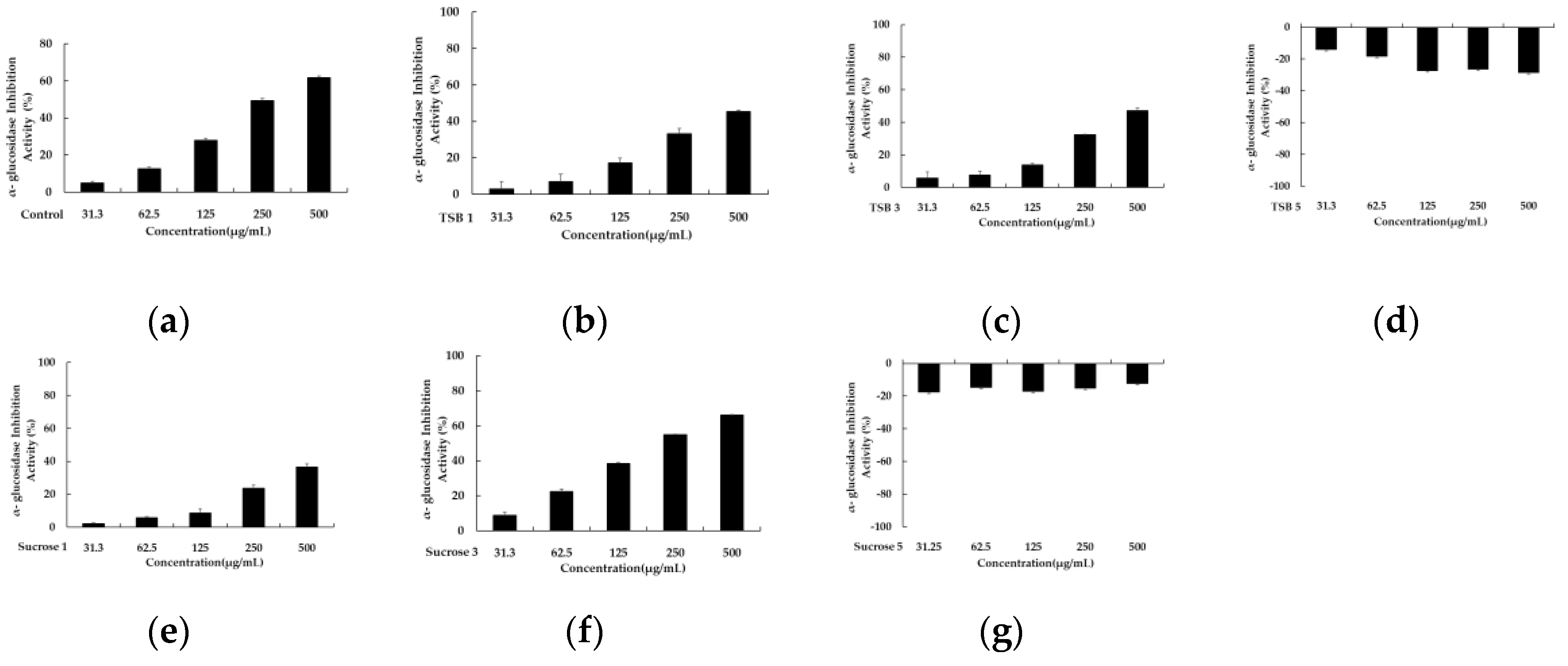

The diabetic population has witnessed a significant increase over the past two decades, establishing it as a global epidemic. One therapeutic approach to managing diabetes involves the development of α-glucosidase inhibitor drugs. These inhibitors work by impeding the hydrolysis of disaccharides into glucose monomers through reversible and competitive inhibition, thereby curtailing glucose absorption and mitigating postprandial hyperglycemic effects. Consequently, α-glucosidase inhibitors have emerged as a promising strategy for treating type 2 diabetes [

24,

25,

26]; however, synthetic α-glucosidase inhibitors often trigger gastrointestinal side effects, such as flatulence, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. Consequently, discovering effective and safe alternative α-glucosidase inhibitors devoid of side effects poses an urgent challenge. On another front, since diabetes contributes to complications stemming from free radical reactions, utilizing antioxidants in diabetes treatment can forestall diabetic complications [

27,

28,

29]. Hence, we assessed the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of stevia ferments with confirmed antioxidant capacity. As illustrated in

Figure 3, among the six stevia ferments, significant α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was only observed in the sample from the third day with sucrose. The IC

50 value of the third-day sample with sucrose was 212.81 ± 2.15 μg/mL.

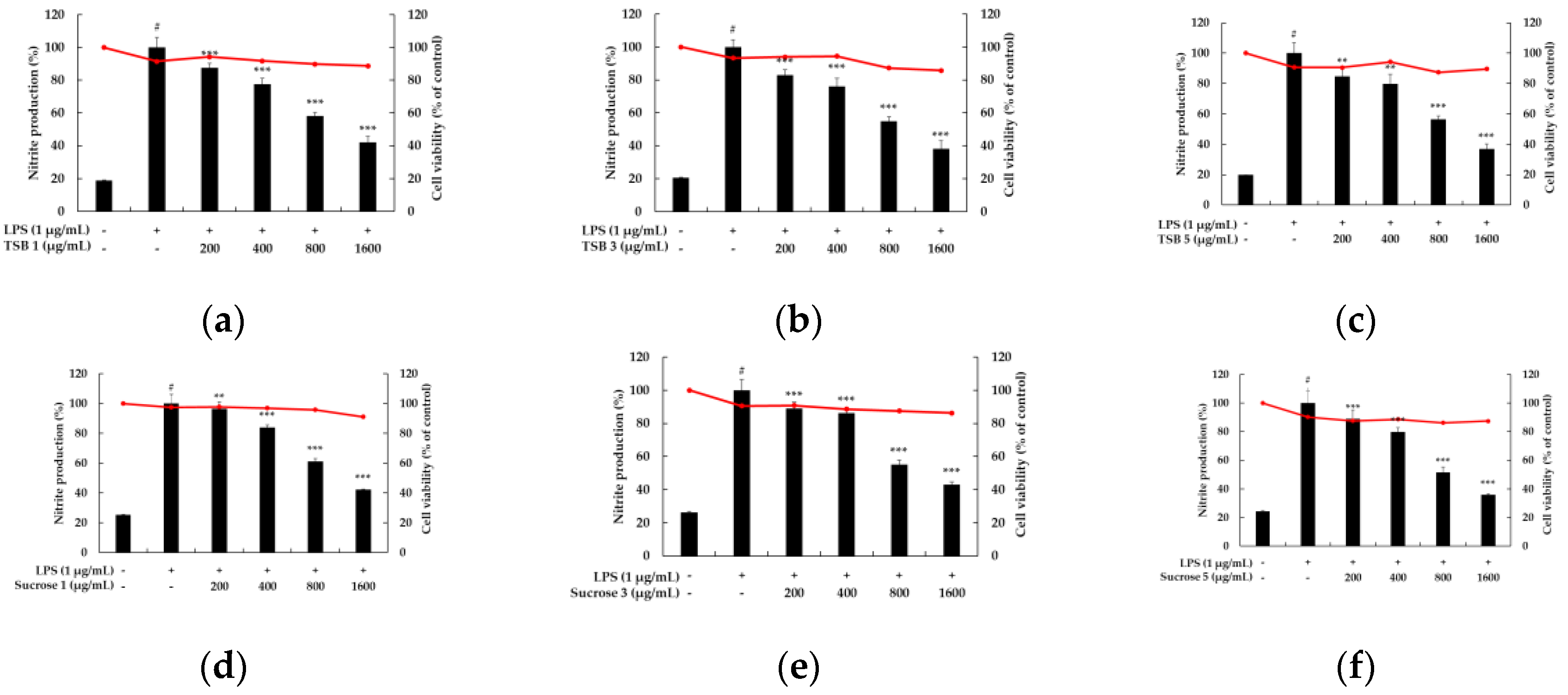

3.2. Anti-Inflammatory Capacity of Stevia Ferments

One of the most commonly utilized model systems for assessing the safety and efficacy of anti-inflammatory drugs is the RAW264.7 cell system, a murine-derived macrophage cell line that exhibits a robust inflammatory response upon exposure to inflammatory stimuli like LPS. The popularity of the RAW264.7 model system can be attributed to its commercial availability, ease of culture, and scalability for large-scale screening. Macrophages engaged in the inflammatory response are activated by various stimuli or cytokines secreted by immune cells, leading to the production of proinflammatory cytokines such as NO and prostaglandin E

2 (PGE

2). These cytokines trigger inflammatory responses such as pain, swelling, dysfunction, redness, and fever, and stimulate the migration of immune cells to the site of inflammation. Notably, NO, a highly reactive substance, is synthesized from L-arginine by nitric oxide synthase (NOS), which exists in constitutive and inducible forms (iNOS). Particularly, iNOS expression has been observed in various cells, including hepatocytes, smooth muscle cells, bone marrow cells, monocytes, and macrophages, producing substantial amounts of NO upon stimulation by external factors or inflammatory cytokines [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. Hence, we employed the RAW264.7 cell system to investigate whether stevia ferments inhibit NO production, which effectively regulates the expression of proinflammatory mediators. Initially, we assessed the cytotoxic effects of six stevia ferments using the MTT assay. For stevia ferment concentrations ranging from 200 to 1600 µg/mL, cell viability after 24 h of treatment with 1 µg/mL LPS remained above 80%, indicating no significant cytotoxicity even at 1600 µg/mL; therefore, subsequent experiments were conducted with stevia ferment concentrations up to 1600 µg/mL, and the impact of stevia ferment on NO production in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells was confirmed by using a Griess reagent assay. As depicted in

Figure 4, LPS treatment significantly elevated NO levels by up to four-fold. Conversely, treatment with the six different stevia ferments led to a concentration-dependent inhibition of NO production in LPS-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells. Collectively, these findings suggest that stevia ferments possess anti-inflammatory effects and hold potential applications in related diseases.

3.3. Qualitative Analysis of the Stevia Ferments

The stevia ferment was extracted with 50% acetone because acetone is a polar, nonprotonated solvent and can dissolve a wide range of organic compounds, including polar and nonpolar substances, and we decided to further investigate the composition of the stevia ferment extract. An analysis by UPLC-QTOF-MS revealed 23 substances related to terpenoids, flavonoids, and polyphenols. Detailed information, including relative retention time (min), react mass (Da), observed m/z, and MS fragments of chemical substances in the stevia ferment extract, is listed in

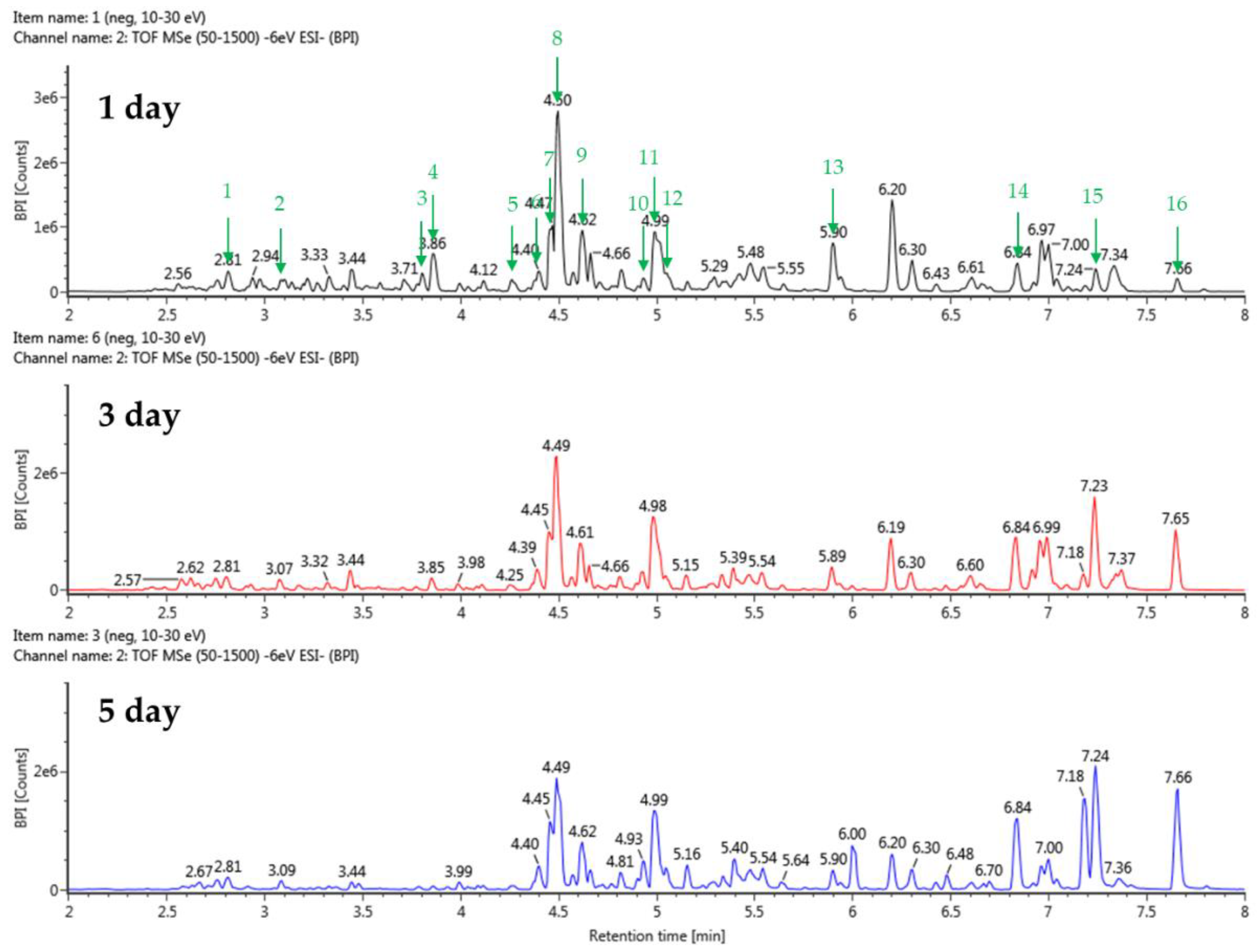

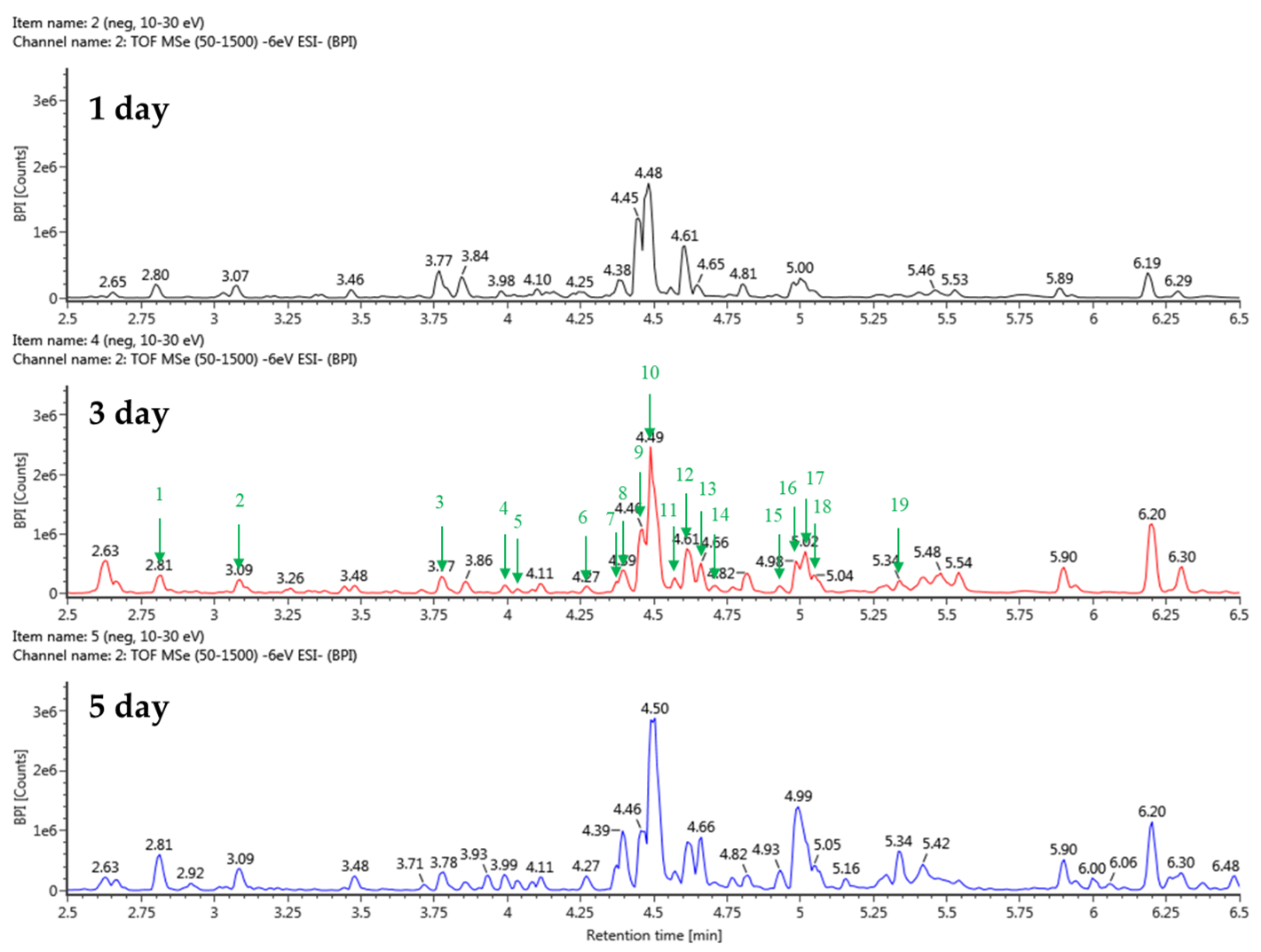

Table 2. The base peak chromatogram in negative ion mode was displayed in

Figure 3. The results indicated the presence of five flavonoids, four phenolic acids, four fatty acids, and ten terpenoids. As expected, from the fermentation with TSB and sucrose, the indicator components of stevia, rubusoside, steviolbioside, and rebaudioside derivatives, as well as dulcoside A and phlomisoside II, eluted and were identified in the chromatogram. In particular, chlorogenic acid, a phenolic compound, eluted prematurely in the chromatograms of stevia fermentations with TSB and sucrose with a reaction mass of 353.0873 Da and 353.0870 Da, respectively, at the same relative retention time of 2.81 min (

Figure 4,

Table 2). Interestingly, as shown in the figure, fatty acid compounds eluted only from the stevia fermentation with TSB, with 15,16-dihode, 10-ketostearic acid, methyl palmoxirate, and hydroxystearic acid eluting at relative retention times of 5.91 to 7.66 min in the chromatogram. Finally, a tetrahydrocortisol derivative, tetrahydro-11-deoxy cortisol 3-O-β-D-glucuronide, eluted from stevia fermentations using sucrose as a carbon source, but few bioactive studies of this compound have been reported. Tetrahydrocortisol, also known as urocortisol, is a neurosteroid and an inactive metabolite of cortisol, acting as a negative allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor, similarly to pregnenolone sulfate [

37].

Figure 5.

Total ion chromatograms in negative ion mode (from UPLC-Q-TOF-MS) of stevia ferments using barley nuruk and TSB medium.

Figure 5.

Total ion chromatograms in negative ion mode (from UPLC-Q-TOF-MS) of stevia ferments using barley nuruk and TSB medium.

Table 1.

Identification of major metabolites in stevia ferments using TSB media via UPLC-QTOF-MS.

Table 1.

Identification of major metabolites in stevia ferments using TSB media via UPLC-QTOF-MS.

| No. |

RT1

(min) |

Proposed Compound |

Exact Mass

(M-H) |

MS

Fragments |

| 1 |

2.81 |

Chlorogenic acid |

353.0873 |

191, 135 |

| 2 |

3.09 |

Patuletin-3-O-(4″-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl)-7-O-(2‴-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranoside) |

707.1832 |

191, 173, 93 |

| 3 |

3.81 |

Quercitrin |

447.0925 |

300, 151 |

| 4 |

3.87 |

Cynarine |

515.1188 |

353, 173 |

| 5 |

4.28 |

3,4,5-Tricaffeoylquinic acid |

677.1512 |

515, 353 |

| 6 |

4.41 |

Quercetin |

301.0346 |

151 |

| 7 |

4.47 |

Rebaudioside A |

965.4258 |

623 |

| 8 |

4.50 |

Rubusoside/steviolbioside |

641.3182 |

479, 317 |

| 9 |

4.63 |

Rebaudioside C |

949.4308 |

713 |

| 10 |

4.94 |

Stevioside |

803.3720 |

623 |

| 11 |

5.00 |

Rubusoside/steviolbioside |

641.3180 |

179, 317 |

| 12 |

5.06 |

Dulcoside A |

787.3773 |

625 |

| 13 |

5.91 |

15,16-Dihode/9(S)-Hpode |

311.2220 |

293, 223, 87 |

| 14 |

6.84 |

9-Hode |

295.2271 |

277, 185 |

| 15 |

7.25 |

10-Ketostearic acid/methyl palmoxirate |

297.2430 |

279, 185, 167 |

| 16 |

7.66 |

Hydroxystearic acid |

299.2586 |

281, 253, 141 |

Figure 6.

Total ion chromatograms in negative ion mode (from UPLC-Q-TOF-MS) of stevia ferments using barley nuruk and sucrose.

Figure 6.

Total ion chromatograms in negative ion mode (from UPLC-Q-TOF-MS) of stevia ferments using barley nuruk and sucrose.

Table 2.

Identification of major metabolites in stevia ferments using sucrose by UPLC-QTOF-MS.

Table 2.

Identification of major metabolites in stevia ferments using sucrose by UPLC-QTOF-MS.

| No. |

RT1

(min) |

Proposed Compound |

Exact Mass

(M-H) |

MS

Fragments |

| 1 |

2.81 |

Chlorogenic acid |

353.0870 |

191, 135 |

| 2 |

3.09 |

Patuletin-3-O-(4″-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranosyl)-7-O-(2‴-O-acetyl-α-L-rhamnopyranoside) |

707.1835 |

191, 173, 93 |

| 3 |

3.78 |

Cynarine |

515.1184 |

353, 173 |

| 4 |

3.99 |

Rebaudioside E/rebaudioside A |

965.4249 |

845, 641 |

| 5 |

4.04 |

Rebaudioside I/rebaudioside D |

1127.4772 |

1111, 803 |

| 6 |

4.27 |

3,4,5-Tricaffeoylquinic acid |

677.1516 |

515, 353 |

| 7 |

4.38 |

Luteolin/kaempferol |

285.0399 |

133 |

| 8 |

4.40 |

Quercetin |

301.0346 |

151 |

| 9 |

4.47 |

Rebaudioside E/rebaudioside A |

965.4256 |

623 |

| 10 |

4.50 |

Rubusoside/steviolbioside |

641.3181 |

611, 317 |

| 11 |

4.58 |

Rebaudioside F |

935.4149 |

611 |

| 12 |

4.63 |

Dulcoside A |

787.3771 |

625 |

| 13 |

4.67 |

Phlomisoside II |

625.3226 |

661, 449 |

| 14 |

4.71 |

Rebaudioside B/rebaudioside G/rubusoside |

803.3726 |

641, 611, 317 |

| 15 |

4.94 |

Rebaudioside B/rebaudioside G/rubusoside |

803.3724 |

641, 611, 317 |

| 16 |

5.00 |

Rubusoside/steviolbioside |

641.3175 |

479, 317 |

| 17 |

5.03 |

(-)-Pinellic acid |

329.2329 |

229, 211, 171, 139 |

| 18 |

5.06 |

Chrysosplenol D/jaceidin |

359.0772 |

344, 329 |

| 19 |

5.35 |

Tetrahydro-11-deoxy Cortisol 3-O-β-D-Glucuronide |

525.2702 |

317, 171 |

3.4. Raw Data Statistics

The calculated results for the total number of bases, number of reads, GC content (%), Q20 (%), and Q30 (%) for the 12 stevia ferments are shown below. Interestingly, among the stevia fermentations using a TSB medium and sucrose carbon source, the analysis using ITS primers detected microorganisms with low G + C content starting from the fifth day of fermentation in the TSB application, whereas in the sucrose application microorganisms were detected consistently from the first day of fermentation.

Table 3.

The analytical results for two types of barley-nuruk-fermented stevia by period.

Table 3.

The analytical results for two types of barley-nuruk-fermented stevia by period.

| Samples |

Total Bases (bp)1

|

Total Reads2

|

GC (%)3

|

AT (%)4

|

Q20 (%)5

|

Q30 (%)6

|

| TSB 1_16S |

62,594,154 |

207,954 |

54.85 |

45.15 |

90.08 |

79.46 |

| TSB 1_ITS |

60,307,156 |

200,356 |

50.84 |

49.16 |

88.05 |

76.64 |

| TSB 3_16S |

65,093,056 |

216,256 |

54.79 |

45.21 |

89.90 |

79.16 |

| TSB 3_ITS |

75,572,070 |

251,070 |

58.14 |

41.86 |

85.17 |

72.54 |

| TSB 5_16S |

79,682,526 |

264,726 |

54.50 |

45.50 |

89.50 |

78.75 |

| TSB 5_ITS |

93,429,798 |

310,398 |

39.35 |

60.65 |

93.20 |

84.93 |

| Sucrose 1_16S |

56,846,258 |

188,858 |

55.20 |

44.80 |

89.97 |

79.08 |

| Sucrose 1_ITS |

65,697,464 |

218,264 |

38.61 |

61.39 |

92.81 |

84.21 |

| Sucrose 3_16S |

54,704,944 |

181,744 |

53.01 |

46.99 |

90.16 |

79.60 |

| Sucrose 3_ITS |

66,342,206 |

220,406 |

38.46 |

61.54 |

92.36 |

83.00 |

| Sucrose 5_16S |

53,721,276 |

178,476 |

51.94 |

48.06 |

90.92 |

80.86 |

| Sucrose 5_ITS |

52,744,230 |

175,230 |

40.61 |

59.39 |

91.34 |

81.21 |

3.5. Analysis of Microbial Communities

To track changes in bacterial and fungal communities during the fermentation of stevia extracts with barley nuruk, microbial communities were identified through next-generation sequencing targeting the 16S rRNA gene for bacteria and internal transcribed spacer (ITS) gene sequences for fungi. As indicated in

Table 1,

Enterococcus hirae, a species seldom isolated from human clinical samples but known to cause animal infections, dominated the stevia ferment (58.93%), while

Cronobacter sakazakii prevailed (80.92%) in the day 1 culture using a TSB medium.

Cronobacter sakazakii (formerly

Enterobacter sakazakii) is a pathogenic bacterium primarily associated with diseases in infants under two months old, premature infants, and individuals with weakened immune systems or a low birth weight; however, notably, both

E. hirae and

C. sakazakii diminished as fermentation progressed, giving rise to the dominant species, human beneficial bacteria like

Pediococcus pentosaceus and

Pediococcus stilesii, particularly

P. stilesii, which accounted for 0.20%, 40.04%, and 73.37% of the fermentation, respectively. In terms of the fungal community analysis using the ITS region,

Saccharomycopsis fibuligera, categorized as a yeast rather than a fungus, dominated stevia fermentations regardless of sample type and fermentation duration, whether fed with a TSB medium or sugar solution. Specifically, fermentation with a sugar solution and barley nuruk was present in over 99% of samples after 1, 3, and 5 days of fermentation (refer to

Table 2).

S. fibuligera is known to actively accumulate trehalose from starch and secrete significant amounts of amylase, acid protease, and β-glucosidase, showcasing potential for applications in the fermentation industry [

38,

39]. In addition, 7.88% of

Monascus purpureus was present in the TSB 3 ferment. M. purpureus is utilized in the production of red rice, a staple food in Asia, and has been used in traditional Chinese medicine [

40]. In conclusion, utilizing a sucrose solution rather than a TSB medium for stevia fermentation with barley nuruk may facilitate the transformation of beneficial bacteria in the human body.

Table 4.

The analytical results for 16S rRNA primers of barley-nuruk-fermented stevia by period.

Table 4.

The analytical results for 16S rRNA primers of barley-nuruk-fermented stevia by period.

| Species |

TSB 1

(16S) |

TSB 3

(16S) |

TSB 5

(16S) |

Suc 1

(16S) |

Suc 3

(16S) |

Suc 5

(16S) |

Corynebacterium nuruki

Brachybacterium nesterenkovii

Saccharopolyspora phatthalungensis

Streptomyces cacaoi

Aerosakkonema funiforme

Bacillus inaquosorum

Bacillus velezensis

Staphylococcus gallinarum

Staphylococcus kloosii

Enterococcus gallinarum

Enterococcus hirae

Enterococcus lactis

Pediococcus pentosaceus

Pediococcus stilesii

Buttiauxella warmboldiae

Cronobacter dublinensis

Cronobacter sakazakii

Enterobacter cloacae

Enterobacter mori

Klebsiella oxytoca

Klebsiella pneumoniae

Klebsiella variicola

Kosakonia cowanii

Phytobacter diazotrophicus

Pseudescherichia vulneris

Salmonella bongori

Erwinia billingiae

Erwinia gerundensis

Erwinia persicina

Mixta calida

Pantoea agglomerans

Pantoea vagans

[Curtobacterium] plantarum

Other |

0.02%

0.01%

0.05%

0.07%

0.00%

0.00%

0.02%

0.02%

0.04%

0.09%

58.93%

0.55%

1.22%

2.58%

0.83%

0.00%

16.65%

1.04%

1.00%

0.13%

3.78%

4.79%

7.97%

0.00%

0.17%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.02%

0.00% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

2.71%

19.24%

0.08%

1.96%

13.77%

0.14%

0.00%

52.21%

0.77%

0.46%

0.03%

2.61%

2.75%

3.23%

0.00%

0.02%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

14.28%

18.06%

0.00%

1.71%

19.89%

0.17%

0.00%

33.07%

0.91%

0.52%

0.02%

4.14%

4.24%

2.86%

0.00%

0.05%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.05%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.02%

0.01%

0.03%

0.00%

0.05%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.63%

0.00%

13.25%

0.20%

0.00%

0.15%

80.92%

0.30%

0.17%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

1.70%

0.02%

0.00%

0.00%

0.42%

0.02%

0.04%

0.10%

0.08%

1.72%

0.10%

0.01% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

0.06%

0.04%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.06%

0.00%

29.38%

40.04%

0.00%

0.08%

29.12%

0.18%

0.10%

0.00%

0.21%

0.17%

0.43%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.04%

0.00%

0.05%

0.05% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

22.71%

73.37%

0.00%

0.00%

2.98%

0.14%

0.05%

0.00%

0.35%

0.39%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01% |

3.6. Human Skin Primary Irritation

Thirty female volunteers, aged 20–50 years (mean age of 43.33 ± 7.03 years, range of 22–50 years), with no history of irritant and/or allergic contact dermatitis, participated in the skin patch test. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Dermapro Inc. in accordance with the ethical principles of medical research in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and was conducted after written informed consent was obtained from each volunteer (IRB no. 1-220777-A-N-01-DICN21249). As shown in

Table 5, the test results indicated that the high-concentration extracts (1 mg/mL) of the six stevia ferments were hypoallergenic in terms of primary irritation to human skin.

Table 5.

The analytical results for ITS primers of barley-nuruk-fermented stevia by period.

Table 5.

The analytical results for ITS primers of barley-nuruk-fermented stevia by period.

| Species |

TSB 1

(ITS) |

TSB 3

(ITS) |

TSB 5

(ITS) |

Suc 1

(ITS) |

Suc 3

(ITS) |

Suc 5

(ITS) |

Other

Stemphylium sp.

Aspergillus sp.

Aspergillus amstelodami

Aspergillus flavus

Monascus purpureus

Thermomyces sp.

Hyphopichia burtonii

Millerozyma farinosa

Kodamaea ohmeri

Issatchenkia orientalis

Candida parapsilosis

Saccharomycopsis fibuligera

Trichomonascus ciferrii

Lichtheimia corymbifera

Rhizomucor pusillus

Rhizopus microsporus |

0.03%

0.00%

0.50%

0.60%

0.00%

1.82%

0.00%

0.08%

0.01%

0.07%

0.00%

0.00%

96.37%

0.01%

0.47%

0.05%

0.00% |

0.08%

0.02%

1.93%

2.72%

0.00%

7.88%

0.03%

0.14%

0.00%

0.15%

0.00%

0.12%

86.14%

0.00%

0.79%

0.00%

0.00% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.14%

0.19%

0.00%

0.12%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00%

99.54%

0.00%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.09%

0.03%

0.13%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

99.69%

0.00%

0.02%

0.00%

0.04% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.01%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

99.99%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00% |

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.33%

0.00%

99.67%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00%

0.00% |

4. Conclusions

Riding the health winds that have been blowing across society during the pandemic and post-pandemic, organic and herbal products, as well as natural functional products that use fermented ingredients to increase absorption and functionality compared to existing products, have gained prominence. Similarly, interest in natural sugars derived from stevia, which is 200 to 300 times sweeter than sucrose and is famous for its low calorie content, is also increasing. In this study, six stevia ferments (TSB 1, TSB 2, TSB 3, Sucrose 1, Sucrose 2, and Sucrose 3) were prepared by fermenting stevia leaf extract with barley nuruk, a traditional fermentation starter on Jeju, and TSB, a commercial medium, for 1, 3, and 5 days, and analyzing the microbial communities and metabolites for their potential to promote human health. TSB 3 and Sucrose 3 were superior in antioxidant efficacy using DPPH and ABTS scavenging capacity, and Sucrose 3 had relatively better radical scavenging capacity than TSB 3. Only Sucrose 2 had anti-obesity efficacy when using an α-glucosiadase inhibition test. Furthermore, all six stevia ferments inhibited the production of NO in a concentration-dependent manner in LPS-induced mouse macrophage 264.3 cells. Further UPLC-QTOF-MS analyses identified 23 compounds, including five flavonoids, four phenolic acids, and four fatty acids, including ten terpenoids, including the stevia indicator rebadioside derivatives and dulcoside A. Interestingly, the sample fermented for 1 day using a TSB medium and sucrose was dominated by the pathogens Enterococcus hirae (58.93%) and Cronobacter sakazakii (80.92%), but as the fermentation progressed, the microbial community changed, with the pathogens disappearing and lactic acid bacteria such as Pediococcus stilesii (73.37%) dominating the stevia ferment. On the other hand, a microbial community analysis using ITS primers showed that Saccharomycopsis fibuligera, which is classified as a yeast, dominated all six stevia ferments regardless of the fermentation period, especially Sucrose 1, Sucrose 2, and Sucrose 3, which were dominated by S. fibuligera by more than 99%. Finally, a skin irritation test was performed for the topical application of stevia ferments to human skin, and the results showed that the high-concentration extracts (1 mg/mL) of all six stevia ferments were hypoallergenic. Taken together, these results suggest that barley nuruk fermentation with sucrose from stevia leaves offers promise as a natural ingredient for functional foods and cosmetics.

Table 6.

Results of human skin primary irritation test (n = 30).

Table 6.

Results of human skin primary irritation test (n = 30).

| No |

Test

Sample |

No. of

Responder |

20 min After

Patch Removal |

24 hr After

Patch removal |

Reaction Grade (R) |

| +1 |

+2 |

+3 |

+4 |

+1 |

+2 |

+3 |

+4 |

| 1 |

TSB 1 (1mg/mL)

|

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 2 |

TSB 3 (1 mg/mL) |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0.4 |

| 3 |

TSB 5 (1 mg/mL) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 4 |

Suc 1(1 mg/mL) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 5 |

Suc 3(1 mg/mL) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| 6 |

Suc 5 (1 mg/mL) |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.G.H. and C.S.S.; methodology, H.J.H. and M.N.K.; software, H.J.H.; validation, H.J.H. and M.N.K.; formal analysis, H.J.H. and M.N.K.; investigation, H.J.H. and M.N.K.; writing—original draft preparation, C.G.H.; writing—review and editing, C.G.H.; supervision, C.G.H.; project administration, C.G.H.; funding acquisition, C.G.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy, Korea, under the “Regional Innovation Cluster Development Program (Non-R&D, P0024160)” supervised by the Korea Institute for Advancement of Technology (KIAT).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the ethics committee of Dermapro Co. Ltd. for studies involving humans (IRB no. 1-220777-A-N-01-DICN21249).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Jeong, D.M.; Kim, H.J.; Jeon, M.S.; Yoo, S.J.; Moon, H.Y.; Jeon, E.J.; Jeon, C.O.; Eyun, S.I.; Kang, H.A. Genomic and functional features of yeast species in Korean traditional fermented alcoholic beverage and soybean products. FEMS Yeast Res. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.H. Study on the Dietary Culture of Confucism; Sauge-Zeuhn Rites in Korea, China and Japan. J. Korean Soc. Food Cult. 1997, 12, 155-172.

- Xia, Y.; Luo, H.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, W. Microbial diversity in jiuqu and its fermentation features: saccharification, alcohol fermentation and flavors generation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 107, 25-41. [CrossRef]

- Allwood, J.G.; Wakeling, L.T.; Bean, D.C. Fermentation and the microbial community of Japanese koji and miso: A review. J. Food Sci. 2021, 86, 2194-2207. [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.; Park, S.E.; Kim, E.J.; Seo, S.H.; Cho, K.M.; Kwon, S.J.; Lee, M.H.; Son, H.S. Effects of saccharification agents on the microbial and metabolic profiles of Korean rice wine (makgeolli). Food Res. Int. 2023, 172, 113367. [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.; Muchangi, K.; Quach, E.; Chen, T.; Owens, A.; Otter, D.; Phillips, M.; Kam, R. Characterisation of Korean rice wine (makgeolli) prepared by different processing methods. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2022, 6, 100420. [CrossRef]

- Bal, J.; Yun, S.H.; Yeo, S.H.; Kim, J.M.; Kim, B.T.; Kim, D.H. Effects of initial moisture content of Korean traditional wheat-based fermentation starter nuruk on microbial abundance and diversity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 2093-2106. [CrossRef]

- Jung, M.J.; Nam, Y.D.; Roh, S.W.; Bae, J.W. Unexpected convergence of fungal and bacterial communities during fermentation of traditional Korean alcoholic beverages inoculated with various natural starters. Food Microbiol. 2012, 30, 112-123. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.B.; Hyun, C.G. Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Their Correlation with Microbial Community of Shindari, a Traditional Jeju Beverage. Fermentation 2020, 6, 87. [CrossRef]

- Chung, Y.C.; Ko, J.H.; Kang, H.K.; Kim, S.; Kang, C.I.; Lee, J.N.; Park, S.M.; Hyun, C.G. Antimelanogenic Effects of Polygonum tinctorium Flower Extract from Traditional Jeju Fermentation via Upregulation of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase and Protein Kinase B Activation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2895. [CrossRef]

- Salvadori, M.; Rosso, G. Update on the gut microbiome in health and diseases. World J. Methodol. 2024, 14, 89196. [CrossRef]

- Malakar, S.; Sutaoney, P.; Madhyastha, H.; Shah, K.; Chauhan, N.S.; Banerjee, P. Understanding gut microbiome-based machine learning platforms: A review on therapeutic approaches using deep learning. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2024, 103, e14505. PMID: 3849181. [CrossRef]

- Kahraman-Ilıkkan, Ö. Microbiome composition of kombucha tea from Türkiye using high-throughput sequencing. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1826-1833. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; D’Amico, D.J. Composition, Succession, and Source Tracking of Microbial Communities throughout the Traditional Production of a Farmstead Cheese. mSystems 2021, 6, e0083021. [CrossRef]

- Seo, H.; Lee, S.; Park, H.; Jo, S.; Kim, S.; Rahim, M.A.; Ul-Haq, A.; Barman, I.; Lee, Y.; Seo, A.; Kim, M.; Jung, I.Y.; Song, H.Y. Characteristics and Microbiome Profiling of Korean Gochang Bokbunja Vinegar by the Fermentation Process. Foods 2022, 11, 3308. [CrossRef]

- Park, D.G.; Ha, E.S.; Kang, B.; Choi, I.; Kwak, J.E.; Choi, J.; Park, J.; Lee, W.; Kim, S.H.; Kim, S.H.; Lee, J.H. Development and Evaluation of a Next-Generation Sequencing Panel for the Multiple Detection and Identification of Pathogens in Fermented Foods. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2023, 33, 83-95. [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Heo, S.; Na, H.E.; Lee, G.; Kim, J.H.; Kwak, M.S.; Sung, M.H.; Jeong, D.W. Bacterial Community of Galchi-Baechu Kimchi Based on Culture-Dependent and - Independent Investigation and Selection of Starter Candidates. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2022, 32, 341-347. [CrossRef]

- Song, E.J.; Lee, E.S.; Park, S.L.; Choi, H.J.; Roh, S.W.; Nam, Y.D. Bacterial community analysis in three types of the fermented seafood, jeotgal, produced in South Korea. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 1444-1454. [CrossRef]

- Schiatti-Sisó, I.P.; Quintana, S.E.; García-Zapateiro, L.A. Stevia (Stevia rebaudiana) as a common sugar substitute and its application in food matrices: an updated review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1483-1492. Epub 2022 Mar 2. [CrossRef]

- Hollá, M.; Šatínský, D.; Švec, F.; Sklenářová, H. UHPLC coupled with charged aerosol detector for rapid separation of steviol glycosides in commercial sweeteners and extract of Stevia rebaudiana. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 207, 114398. [CrossRef]

- Mert Ozupek, N.; Cavas, L. Modelling of multilinear gradient retention time of bio-sweetener rebaudioside A in HPLC analysis. Anal. Biochem. 2021, 627, 114248. [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [CrossRef]

- Echegaray, N.; Pateiro, M.; Munekata, P.E.S.; Lorenzo, J.M.; Chabani, Z.; Farag, M.A.; Domínguez, R. Measurement of Antioxidant Capacity of Meat and Meat Products: Methods and Applications. Molecules 2021, 26, 3880. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Xie, T.; Wu, Q.; Hu, Z.; Luo, Y.; Luo, F. Alpha-Glucosidase Inhibitory Peptides: Sources, Preparations, Identifications, and Action Mechanisms. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4267. [CrossRef]

- Kumari, S.; Saini, R.; Bhatnagar, A.; Mishra, A. Exploring plant-based alpha-glucosidase inhibitors: promising contenders for combatting type-2 diabetes. Arch. Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 28, 1-16. [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Ji, N.; Zhu, Y. Research Progress of α-Glucosidase Inhibitors Produced by Microorganisms and Their Applications. Foods 2023, 12, 3344. [CrossRef]

- Han, X.; Choi, S.I.; Men, X.; Lee, S.J.; Oh, G.; Jin, H.; Oh, H.J.; Kim, E.; Kim, J.; Lee, B.Y.; Lee, O.H. Radical Scavenging-Linked Anti-Obesity Effect of Standardized Ecklonia stolonifera Extract on 3T3-L1 Preadipocytes and High-Fat Diet-Fed ICR Mice. J. Med. Food. 2023, 26, 232-243. [CrossRef]

- Chaipoot, S.; Punfa, W.; Ounjaijean, S.; Phongphisutthinant, R.; Kulprachakarn, K.; Parklak, W.; Phaworn, L.; Rotphet, .;, Boonyapranai, K. Antioxidant, Anti-Diabetic, Anti-Obesity, and Antihypertensive Properties of Protein Hydrolysate and Peptide Fractions from Black Sesame Cake. Molecules 2022, 28, 211. [CrossRef]

- Peng, M.; Gao, Z.; Liao, Y.; Guo, J.; Shan, Y. Development of Citrus-Based Functional Jelly and an Investigation of Its Anti-Obesity and Antioxidant Properties. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022, 11, 2418. [CrossRef]

- Bae, S.; Hyun, CG. The Effects of 2′-Hydroxy-3,6′-Dimethoxychalcone on Melanogenesis and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 10393. [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Hyun CG. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Psoralen Derivatives on RAW264.7 Cells via Regulation of the NF-κB and MAPK Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 5813. [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S.B.; Chung, Y.C.; Hyun, C.G. Nojirimycin suppresses inflammation via regulation of NF-κ B signaling pathways. Pharmazie 2020, 75, 637-641. [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.K.; Hyun, CG. 4-Hydroxy-7-Methoxycoumarin Inhibits Inflammation in LPS-activated RAW264.7 Macrophages by Suppressing NF-κB and MAPK Activation. Molecules 2020, 25, 4424. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.S.; Park, J.S.; Chung, Y.C.; Jang, S.; Hyun, C.G.; Kim S.Y. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Formononetin 7-O-phosphate, a Novel Biorenovation Product, on LPS-Stimulated RAW 264.7 Macrophage Cells. Molecules 2019, 24, 3910. PMID: 31671623. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, W.J.; Moon, J.Y.; Song, G.; Lee, Y.K.; Han, M.S.; Lee, J.S.; Ihm, B.S.; Lee, W.J.; Lee, N.H.; Hyun, C.G. Artemisia fukudo essential oil attenuates LPS-induced inflammation by suppressing NF-kappaB and MAPK activation in RAW 264.7 macrophages. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2010, 48, 1222-1229. [CrossRef]

- Yoon, W.J.; Ham, Y.M.; Yoo, B.S.; Moon, J.Y.; Koh, J.; Hyun, C.G. Oenothera laciniata inhibits lipopolysaccharide induced production of nitric oxide, prostaglandin E2, and proinflammatory cytokines in RAW264.7 macrophages. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2009, 107, 429-438. [CrossRef]

- Penland, S.N.; Morrow, A.L. 3alpha,5beta-Reduced cortisol exhibits antagonist properties on cerebral cortical GABA(A) receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004, 506, 129-132. [CrossRef]

- Farh, M.E.; Abdellaoui, N.; Seo, J.A. pH Changes Have a Profound Effect on Gene Expression, Hydrolytic Enzyme Production, and Dimorphism in Saccharomycopsis fibuligera. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 672661. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, E.; Trinh, T.N.; Son, H.; Lee, Y.W.; Seo, J.A. Comprehensive analysis of fungal diversity and enzyme activity in nuruk, a Korean fermenting starter, for acquiring useful fungi. J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 357-365. [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.S.; Chiu, S.H.; Chen, C.C.; Lin, C.H. Investigation of monacolin K, yellow pigments, and citrinin production capabilities of Monascus purpureus and Monascus ruber (Monascus pilosus). J. Food Drug Anal. 2023, 31, 85-94. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).