Submitted:

28 May 2024

Posted:

29 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Type and Location

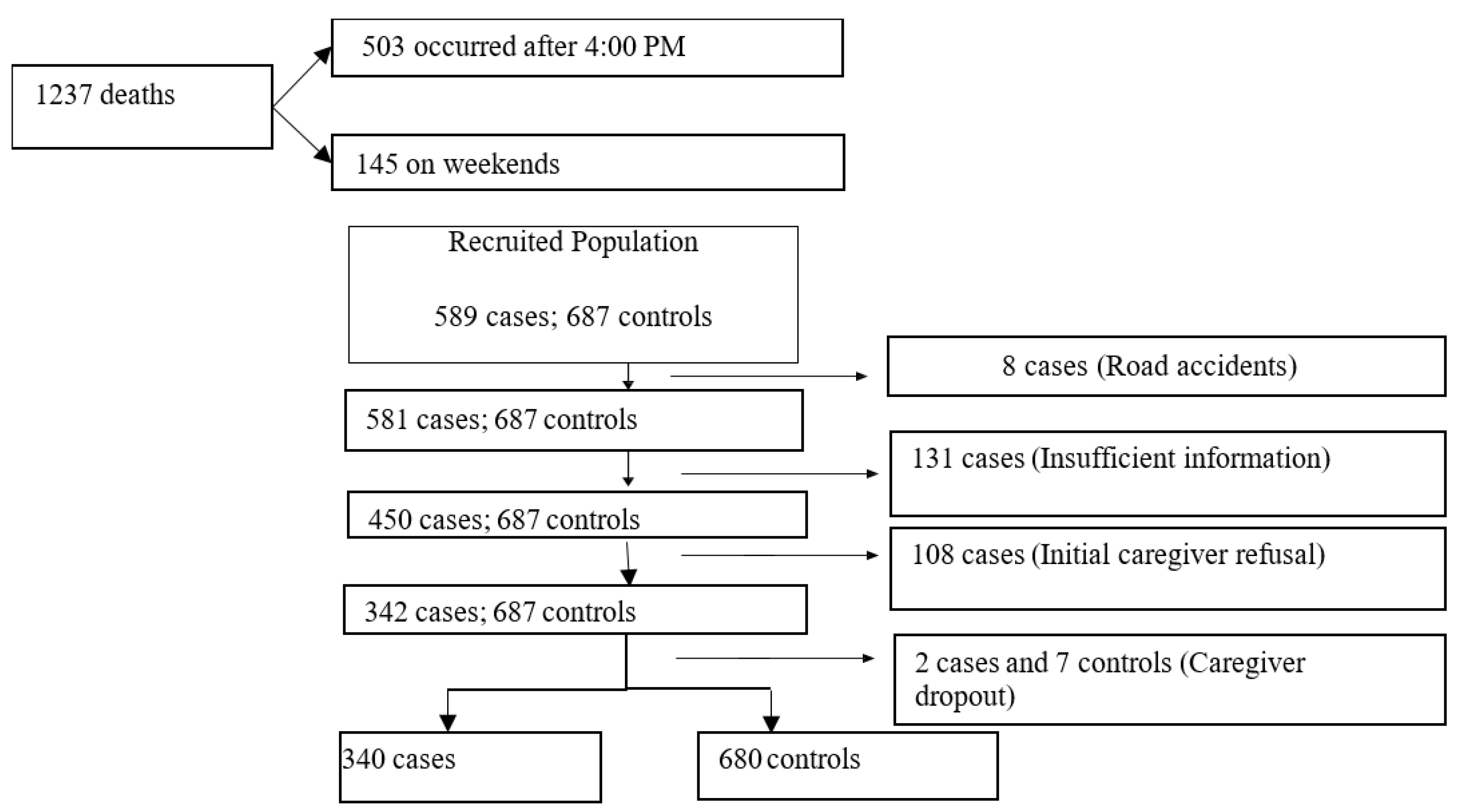

2.2. Population and Sample

2.3. Procedures and Data Collection Instrument

2.4. Definition and Categorization of Variables

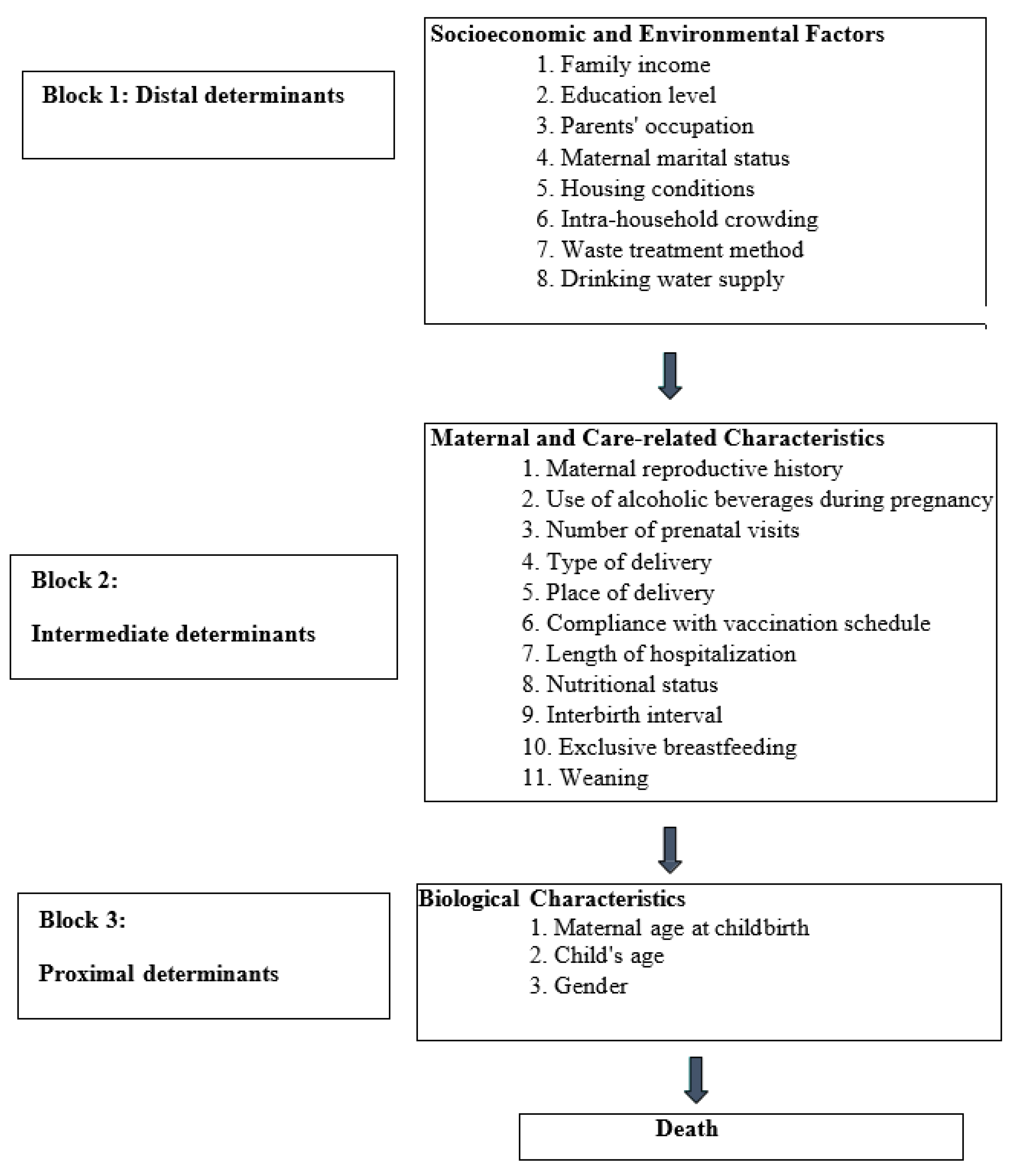

- Family income: average earnings of the family in the three previous months. Categorized into minimum wages (MW): up to 1.0 MW; 2.0-3.00 MW; 3.01-4.00 MW; > 4.0 MW. Assessed by the respondent; considering the national minimum wage at the time of data collection [15]. For stratified analysis, categorized as ≤ 1 MW; 2-3 MW; and ≥ 4 MW.

- Housing condition: A housing score adapted from Ludermir AB (16) was used, considering the components of the residence, to which a score was assigned. Thus, the wall was scored as 1 or 0 depending on whether it was made of brick or other material; the roof was assigned a score of 1 and 0 (tile/slab and other material); floor: 2-ceramic/wood, 1-cement, 0-dirt; water supply: 3-public network, 2-fountain, 1-well or spring, 0-other water supply forms; sewage system: 2-public network, 1-septic tank, 0-no sewage system. The arithmetic mean of the sum of each item was calculated, and individuals with a value below the mean were classified as having poor housing conditions; those with a value around the mean (mean ± 1 standard deviation (SD)), as medium, and those above the mean + 1 SD, as having good conditions. Stratified in the analysis into two categories: not precarious (good and medium) and precarious;

- Household overcrowding: The overcrowding index proposed by Hill et al. [17] was used, considering three categories: 1- no overcrowding: fewer than four people per household and fewer than two people per room; 2- moderate overcrowding: fewer than four people per household and two or more people per room, or four or more people per household but fewer than two per room; 3- intense overcrowding: four or more people per household and at least two per room. For analysis, two categories were considered: no overcrowding and overcrowded (moderate/intense).

- Nutritional status: The weight-for-age anthropometric index was used, calculated at the time of inclusion in the study using the table recommended by the WHO [18]. For analysis, children with nutritional deficits were considered those who had two z-scores below the median value of the reference population in this index; and those without nutritional deficits were those who had two or more z-scores above the median reference value.

- Maternal education: Number of years of completed education. Stratified into: level 1 (no formal education and/or unable to read or write, except for own name); level 2 (able to read and write and/or up to six years of schooling); level 3 (seven to 12 years of schooling); level 4 (>12 years of schooling).

- Frequent alcohol use was considered the consumption of at least one alcoholic drink, equivalent to 10 or 12g of alcohol [19], per week during pregnancy.

2.5. Data Analysis Strategy: Hierarchical Modeling

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characterization

| ICD-10 | Diagnosis | Discharge status | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Case | ||||||

| No | % | No | % | No | % | ||

| R10.0 | Acute abdomen | 5 | 0,7 | 5 | 1,5 | 10 | 1,0 |

| D64.9 | Severe anemia | 23 | 3,4 | 21 | 6,2 | 44 | 4,3 |

| Q20 –Q26 | Congenital heart disease | 20 | 2,9 | 10 | 2,9 | 30 | 2,9 |

| E43 | Severe unspecified protein-energy malnutrition | 137 | 20,1 | 50 | 14,7 | 187 | 18,3 |

| A09 | Diarrhea and Presumed Infectious Gastroenteritis | 53 | 7,8 | 32 | 9,4 | 85 | 8,3 |

| G00-G09 | Inflammatory diseases of the central nervous system | 22 | 3,2 | 26 | 7,6 | 48 | 4,7 |

| J00 - J99 | Acute Respiratory Infections | 215 | 31,6 | 62 | 18,2 | 277 | 27,2 |

| D57 | Sickle cell disease | 20 | 2,9 | 9 | 2,6 | 29 | 2,8 |

| K92.2 | Upper gastrointestinal bleeding | 2 | 0,3 | 4 | 1,2 | 6 | 0,6 |

| G91 | Hydrocephalus | 19 | 2,8 | 5 | 1,5 | 24 | 2,4 |

| L08.9 | Localized infection of skin and subcutaneous tissue | 13 | 1,9 | 2 | 0,6 | 15 | 1,5 |

| T18 | Foreign body ingestion | 8 | 1,2 | - | - | 8 | 0,8 |

| B50.8 | Unspecified malaria by Plasmodium falciparum | 104 | 15,3 | 74 | 21,8 | 178 | 17,5 |

| Q44 | Congenital malformations of the gallbladder, bile ducts, and other unspecified liver diseases | 1 | 0,1 | 4 | 1,2 | 5 | 0,5 |

| C80 | Malignant neoplasm, unspecified site | 3 | 0,4 | - | - | 3 | 0,3 |

| P20-P29;M069;E10;A35;G81.0;B05;K40; I27 | Others: Hypoxia, Arthritis, Diabetes, Tetanus, Non-specific flaccid paralysis, AIDS, Measles, Hernia, and Pulmonary Hypertension | 15 | 2,2 | 10 | 2,9 | 25 | 2,5 |

| P07 | Prematurity | - | - | 6 | 1,8 | 6 | 0,6 |

| A41.9 | Unspecified sepsis | 7 | 1,0 | 13 | 3,8 | 20 | 2,0 |

| S09.9 | Traumatic brain injury | 13 | 1,9 | 7 | 2,1 | 20 | 2,0 |

| Total | 680 | 100,0 | 340 | 100,0 | 1020 | 100,0 | |

| Level 1 | Case: n (%) | Control: n (%) | OR (CI 95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal education | ||||

| No schooling | 97(44,7) | 120(55,3) | 10,5(4,5-22,7) | |

| ≤6 years | 157(38,2) | 254(61,8) | 7,7(3,5-17,0) | |

| 7 – 12 years | 79(27,5) | 208(72,5) | 4,7 (2,1-10,6) | |

| >12 years | 7(7,4) | 87(92,6) | 1,0 | |

| Maternal marital status | ||||

| Single | 158(37,4) | 264(62,6) | 1,4(1,1-1,8) | |

| With partner | 182(30,4) | 416(69,6) | 1,00 | |

| Housing conditions | ||||

| Precarious | 136(35,5) | 247(64,5) | 1,2(0,3-1,5) | |

| Non-precarious | 204(32,0) | 433(68,0) | 1,00 | |

| Family income | ||||

| Unknown | 493(66,5) | 248(33,5) | 1,2(0,7-2,0) | |

| ≤ 1 MW | 20(62,5) | 12(37,5) | 1,4 (0,6-3,4) | |

| 1,01 - 3 MW | 107(66,0) | 55(34,0) | 1,2(0,7-2,2) | |

| ≥ 3,01 MW | 60(70,6) | 25(29,4) | 1,00 | |

| Intra-household crowding | ||||

| Moderate to intense crowding | 340(35,0) | 632(65,0) | 0,7(0,6-0,7) | |

| No crowding | -- | 48(100,0) | 1,00 | |

| Caregiver’s integration into the workforce | ||||

| Unemployed | 137(30,6) | 311(69,4) | 0,8(0,6-1,0) | |

| Not unemployed | 203(35,5) | 369(64,5) | 1,00 | |

| Household waste collection and treatment | ||||

| Inappropriate | 180(30,3) | 415(69,7) | 1,4(1,1-1,8) | |

| Appropriate | 160(37,6) | 265(62,4) | 1,00 | |

| Source of drinking water | ||||

| Not appropriate | 324(34,5) | 614(65,5) | 2,2(1,2-3,8) | |

| Appropriate | 16(19,5) | 66(80,5) | 1,00 | |

| Level 2 | Cases: n (%) | Controls: n (%) | OR (CI 95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parity | |||

| ≥ 3 | 151(33,1) | 305(66,9) | 1,0(0,8-1,3) |

| ≤ 2 | 189(33,5) | 375(66,5) | 1,00 |

| Alcohol consumption during pregnancy | |||

| Yes | 222(48,5) | 236(51,5) | 3,5(2,7-4,7) |

| No | 118 (21,0) | 444(79,0) | 1,00 |

| Number of prenatal visits | |||

| ≤ 5 | 219 (33,7) | 430(66,3) | 1,1(0,8-1,4) |

| ≥ 6 | 121 (32,6) | 250(67,4) | 1,00 |

| Type of delivery | |||

| Cesarean | 13(19,1) | 55(80,9) | 0,5(0,2-0,8) |

| Vaginal | 327(34,3) | 625(65,7) | 1,00 |

| Place of delivery | |||

| Non-Hospital | 106(38,0) | 173(62,0) | 1,3(1,0-1,8) |

| Hospital | 234(31,6) | 507(68,4) | 1,00 |

| Length of hospital stay: | |||

| ≤ 24h | 70(76,1) | 22(23,9) | 7,8(4,7-12,8) |

| >24h | 270(29,1) | 658(70,9) | 1,00 |

| Nutritional status | |||

| With nutritional deficit | 202(39,1) | 314(60,9) | 1,7(1,3-2,2) |

| No nutritional deficit | 138(27,4) | 366(72,6) | 1,00 |

| Vaccination schedule | |||

| Incomplete for the age | 88(39,5) | 135(60,5) | 1,4(1,0-1,9) |

| Complete for age | 252(31,6) | 545(68,4) | 1,00 |

| Interbirth interval | |||

| ≤ 24 months | 113 (39,9) | 170(60,1) | 2,0(1,4-2,8) |

| >24 months | 85(25,2) | 252(74,8) | 1,00 |

| Level 3 | Case: n (%) | Control: n (%) | OR (CI95%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 190(33,3) | 380(66,7) | 1,0(0,8-1,3) |

| Female | 150(33,7) | 300(66,7) | 1,00 |

| Child’s age | |||

| ≤ 12 months | 152(33,3) | 305(66,7) | 1,0(0,8-1,3) |

| >12 months | 188(33,4) | 375(66,6) | 1,00 |

| Maternal age at delivery | |||

| 10-19 Years | 142(46,0) | 167(54,0) | 2,5(1,9-3,4) |

| 20 -34 Years | 152(25,3) | 449(74,7) | 1,00 |

| ≥35 Years | 46(41,8) | 64(58,2) | 2,1(1,4-3,2) |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO. Child mortality (under 5 years): WHO; 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/levels-and-trends-in-child-under-5-mortality-in-2020.

- Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Okonofua F, Uthman OA. Under five mortality patterns and associated maternal risk factors in sub-Saharan Africa: A multi-country analysis. PloS one [Internet]. 2018 Pmc6201907]; 13(10):[e0205977 p.]. Available from: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0205977.

- Jeffrey D. Sachs GL, Grayson Fuller, Drumm aE. SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2023. Paris: Dublin University Press, 2023 Contract No.: 10.25546/102924.

- Van Malderen C, Amouzou A, Barros AJD, Masquelier B, Van Oyen H, Speybroeck N. Socioeconomic factors contributing to under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa: a decomposition analysis. BMC public health. 2019;19(1):760.

- Shoo R. Reducing child mortality: the challenges in Africa. UN Chron [Internet]. 2007 [cited 2023 05/November]. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rumishael-Shoo/publication/265619672_Reducing_Child_Mortality_The_Challenges_in_Africa/links/54cb56470cf2517b7561885b/Reducing-Child-Mortality-The-Challenges-in-Africa.pdf.

- e Pinto EA, Alves JG. The causes of death of hospitalized children in Angola. Tropical doctor [Internet]. 2008 Jan [cited 2023 05/November]; 38(1):[66-7 pp.]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18302879/.

- Rosário EV, Costa D, Timóteo L, Rodrigues AA, Varanda J, Nery SV, et al. Main causes of death in Dande, Angola: results from Verbal Autopsies of deaths occurring during 2009-2012. BMC public health [Internet]. 2016 Aug 4 [cited 2023 05/November]; 16:[719 p.]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27491865/.

- Rodrigues EC, Alves BdCA, da Veiga GL, Adami F, Carlesso JS, dos Santos Figueiredo FW, et al. Mortalidade neonatal em Luanda, Angola: o que pode ser feito para sua redução? Journal of Human Growth and Development [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 09/November]; 29(2):[161 p.]. Available from: https://scholar.google.com.br/scholar?hl=pt-BR&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=Mortalidade+neonatal+em+Luanda%2C+Angola%3A+o+que+pode+ser+feito+para+sua+redu%C3%A7%C3%A3o%3F&btnG=.

- Angola MdPedDTM. Inquérito de Indicadores Múltiplos e de Saúde (IIMS) - 2015-2016. Final report. Angola: Instituto Nacional de Estatística, Ministério da Saúde (MINSA), 2015-2016 2017. Report No.: Contract No.: 01.

- Federation, R. Voluntary National Review on the Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Analytical Center under the Government of the Russian Federation: Moscow, Russia [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 10/Novenmer]. Available from: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/286012021_VNR_Report_Angola.pdf.

- Mosley WH, Chen LC. An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. 1984. Bulletin of the World Health Organization [Internet]. 2003 [cited 2023 10/November]; 81(2):[140-5 pp.]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12756980/.

- Lima S, Carvalho ML, Vasconcelos AG. [Proposal for a hierarchical framework applied to investigation of risk factors for neonatal mortality]. Cadernos de saude publica [Internet]. 2008 Aug [cited 2023 10/November]; 24(8):[1910-6 pp.]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18709231/.

- Bizzego A, Gabrieli G, Bornstein MH, Deater-Deckard K, Lansford JE, Bradley RH, et al. Predictors of Contemporary under-5 Child Mortality in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Machine Learning Approach. International journal of environmental research and public health [Internet]. 2021 Feb 1 [cited 2023 10/November]; 18(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33535688/.

- IBGE. Indicadores IBGE. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística, 1991.

- Advogados, Sd. Actualizaçao do valor da retribuiçao mínima mensal garantida. Luanda: 2017.

- Ludermir, AB. unemplyement, informal work, gender and mental health. Cad Saúde Pública. 2000;16(3):647 - 59.

- Hill PC, Jackson-Sillah D, Donkor SA, Otu J, Richard A, Adegbola A, et al. Risk factors for pulmonary tuberculosis: a clinic-based case control study in The Gambia.. BMC Public Health. 2006;6(156).

- WHO WHO. Physical status: the use and interpretation of anthropometry.. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1995.

- World Health, O. Self-help strategies for cutting down or stopping substance use: a guide2010 2010 [cited 2023 11/Dezembro]. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44322.

- Victora CG, Huttly SR, Fuchs SC, Olinto MTA. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. International Journal of Epidemiology. 1997;26(1):224 - 7.

- Olinto, M. The role of conceptual frameworks in epidemiological analysis: a hierarchical approach. International journal of epidemiology [Internet]. 1997 [cited 2023 04/September]; 26(1):[224-7 pp.]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/ije/article/26/1/224/730584?login=true.

- Fuchs SC, Victora CG, Fachel J. Modelo hierarquizado: uma proposta de modelagem aplicada à investigação de fatores de risco para diarréia grave. Revista de Saúde Pública [Internet]. 1996 [cited 2023 04/09]; 30:[168-78 pp.]. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/rsp/a/hP6yDbh7HWXmLymbyvScBMw/?lang=pt&format=html.

- Greenland, S. Modeling and variable selection in epidemiologic analysis. American journal of public health [Internet]. 1989 [cited 2023 04/September]; 79(3):[340-9 pp.]. Available from: https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.79.3.340.

- Pinto EAE, Alves JG. The causes of death of hospitalized children in Angola. Tropical doctor [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2023 03/September]; 38(1):[66-7 pp.]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1258/td.2006.006352.

- Rosário EVN, Costa D, Timóteo L, Rodrigues AA, Varanda J, Nery SV, et al. Main causes of death in Dande, Angola: results from Verbal Autopsies of deaths occurring during 2009–2012 2016 [cited 2023 05/September]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12889-016-3365-6.

- Simão R, Gallo PR. Mortes infantis em Cabinda, Angola: desafio para as políticas públicas de saúde. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2023 03/September]; 16:[826-37 pp.]. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbepid/a/wGTtzSgJPvqXBqJjtm5kD4c/?lang=pt.

- Tette E, Nyarko MY, Nartey ET, Neizer ML, Egbefome A, Akosa F, et al. Under-five mortality pattern and associated risk factors: a case-control study at the Princess Marie Louise Children’s Hospital in Accra, Ghana. BMC pediatrics [Internet]. 2016 [cited 2023 04/September]; 16(1):[1-10 pp.]. Available from: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-016-0682-y.

- Mutombo AM, Mukuku O, Tshibanda KN, Swana EK, Mukomena E, Ngwej DT, et al. Severe malaria and death risk factors among children under 5 years at Jason Sendwe Hospital in Democratic Republic of Congo. Pan African Medical Journal. 2018;29(1):1-8.

- Tesema GA, Seifu BL, Tessema ZT, Worku MG, Teshale AB. Incidence of infant mortality and its predictors in East Africa using Gompertz gamma shared frailty model. Archives of Public Health [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2023 05/September]; 80(1):[1-12 pp.]. Available from: https://archpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13690-022-00955-7.

- GT K, C C, D B, TY T, D L. The effect of maternal education on infant mortality in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one. 2019;14(7):e0220076.

- Ezeh OK, Agho KE, Dibley MJ, Hall JJ, Page AN. Risk factors for postneonatal, infant, child and under-5 mortality in Nigeria: a pooled cross-sectional analysis. BMJ open [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 05/September]; 5(3):[e006779 p.]. Available from: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/bmjopen/5/3/e006779.full.pdf.

- Yaya S, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Seidu A-A, Darteh EKM, Adjei NK. Proximate and socio-economic determinants of under-five mortality in Benin, 2017/2018. BMJ global health [Internet]. 2020 [cited 2023 05/September]; 5(8):[e002761 p.]. Available from: https://gh.bmj.com/content/5/8/e002761.abstract.

- Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Budu E, Armah-Ansah EK, Agbaglo E, Adu C, et al. Proximate, intermediate, and distal predictors of under-five mortality in Chad: analysis of the 2014-15 Chad demographic and health survey data. BMC public health. 2020;20(1):1873.

- Bohland AK, Gonçalves AR. Mortalidade atribuível ao consumo de bebidas alcoólicas. SMAD, Revista Electrónica en Salud Mental, Alcohol y Drogas [Internet]. 2015 [cited 2023 06 Dezembro]; 11(3):[136-44 pp.]. Available from: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/803/80342807004.pdf.

- Grinfeld, H. Consumo nocivo de álcool durante a gravidez. Álcool e suas consequências: uma abordagem multiconceitual São Paulo: Manole [Internet]. 2009 [cited 2023 06 Dezember]; 8(3):[179-99 pp.]. Available from: https://www.saudedireta.com.br/docsupload/1333063336alcoolesuasconsequencias-pt-cap9.pdf.

- Ahumada LA, Anunziata F, Molina JC. Alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Archivos argentinos de pediatria [Internet]. 2021 Feb [cited 2023 08/September]; 119(1):[6-8 pp.]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33458973/.

- Pinto, E. Perfil epidemiológico, clínico e fatores associados ao óbito em crianças internadas no hospital pediátrico de referência de Angola: um estudo transversal: Doctoral Dissertation. Instituto Materno Infantil Professor Fernando Figueira; 2005.

- Organization WH. Report of a WHO technical consultation on birth spacing: Geneva, Switzerland 13-15 June 20052007 [cited 2023 05/September]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665 /69855/WHO_RHR_07.1_eng.pdf?sequence=1.

- Sharaf MF, Rashad AS. Socioeconomic inequalities in infant mortality in Egypt: analyzing trends between 1995 and 2014. Social Indicators Research [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 06/September]; 137:[1185-99 pp.]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11205-017-1631-3.

- Molitoris J, Barclay K, Kolk M. When and where birth spacing matters for child survival: an international comparison using the DHS. Demography [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 05/September]; 56(4):[1349-70 pp.]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6667399/.

- Greenberg JA, Bell SJ, Guan Y, Yu Y-h. Folic acid supplementation and pregnancy: more than just neural tube defect prevention. Reviews in obstetrics and gynecology [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2023 06/September]; 4(2):[52 p.]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3218540/.

- Garenne M, Aaby P. Pattern of exposure and measles mortality in Senegal. Journal of infectious diseases [Internet]. 1990 [cited 2023 06/September]; 161(6):[1088-94 pp.]. Available from: https://academic.oup.com/jid/article-abstract/161/6/1088/905326?login=false.

- Molitoris, J. Breastfeeding during pregnancy and its association with childhood malnutrition and pregnancy loss in low-and middle-income countries. Lund Papers Econ Demogr [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2023 06/September]; 3:[1-81 pp.]. Available from: https://www.ed.lu.se/media/ed/papers/working_papers/LPED%202018%203.pdf.

- Gibbs CM, Wendt A, Peters S, Hogue CJ. The impact of early age at first childbirth on maternal and infant health. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2012;26 Suppl 1(0 1):259-84.

- Finlay JE, Özaltin E, Canning D. The association of maternal age with infant mortality, child anthropometric failure, diarrhoea and anaemia for first births: evidence from 55 low- and middle-income countries. BMJ Open. 2011;1(2):e000226.

- Sinha S, Aggarwal AR, Osmond C, Fall CH, Bhargava SK, Sachdev HS. Maternal Age at Childbirth and Perinatal and Under five Mortality in a Prospective Birth Cohort from Delhi. Indian pediatrics. 2016;53(10):871-7.

- Cavazos-Rehg PA, Krauss MJ, Spitznagel EL, Bommarito K, Madden T, Olsen MA, et al. Maternal age and risk of labor and delivery complications. Maternal and child health journal. 2015;19(6):1202-11.

- Lima LCd. Idade materna e mortalidade infantil: efeitos nulos, biológicos ou socioeconômicos? Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 07 Dezembro]; 27:[211-26 pp.]. Available from: https://www.scielo.br/j/rbepop/a/79fgFBtcB5VgRqshmTkBC9K/.

- Chirwa GC, Mazalale J, Likupe G, Nkhoma D, Chiwaula L, Chintsanya J. An evolution of socioeconomic related inequality in teenage pregnancy and childbearing in Malawi. PloS one. 2019;14(11):e0225374.

- Atuyambe L, Mirembe F, Tumwesigye NM, Annika J, Kirumira EK, Faxelid E. Adolescent and adult first time mothers’ health seeking practices during pregnancy and early motherhood in Wakiso district, central Uganda. Reproductive health [Internet]. 2008 Dec 30 [cited 2023 08/September]; 5:[13 p.]. Available from: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/pamj/article/view/176605.

- Yaya S, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Seidu AA, Darteh EKM, Adjei NK. Proximate and socio-economic determinants of under-five mortality in Benin, 2017/2018. BMJ global health. 2020;5(8).

- Fall CH, Sachdev HS, Osmond C, Restrepo-Mendez MC, Victora C, Martorell R, et al. Association between maternal age at childbirth and child and adult outcomes in the offspring: a prospective study in five low-income and middle-income countries (COHORTS collaboration). Lancet Glob Health [Internet]. 2015 Jul [cited 2023 07 Dezembro]; 3(7):[e366-77 pp.]. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25999096/.

| Factors | β | S.E | Wald | Df | Sig. | OR (CI 95%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver’s occupation (unemployed) | -0,8 | 0,3 | 10,1 | 1 | 0,001 | 0,4(0,3-0,7) | |

| Marital status (without a partner) | -0,1 | 0,3 | 0,3 | 1 | 0,580 | 0,9(0,5-1,4) | |

| Maternal education | |||||||

| No education | 1,5 | 0,7 | 4,9 | 1 | 0,027 | 4,3(1,2-15,7) | |

| ≤6 Years | 1,2 | 0,7 | 3,5 | 1 | 0,060 | 3,4-(1,0-12,1) | |

| 7-12 Years | 1,1 | 0,7 | 2,9 | 1 | 0,087 | 3,1(0,9-11,5) | |

| >12 Years | 5,4 | 3 | 0,144 | ||||

| Frequent alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Yes) | 1,4 | 0,2 | 38,0 | 1 | 0,001 | 3,8(2,5-5,9) | |

| Type of delivery (cesarean section) | -1,4 | 0,8 | 3,3 | 1 | 0,071 | 0,3(0,1-1,1) | |

| Length of hospital stay (≤24 hours) | 2,6 | 0,4 | 40,7 | 1 | 0,001 | 13,8(6,2-30,8) | |

| Nutritional status (with deficit) | 0,8 | 0,2 | 12,3 | 1 | 0,001 | 2,1(1,4-3,2) | |

| Interbirth interval (≤24 months) | 0,5 | 0,2 | 6,1 | 1 | 0,014 | 1,7(1,1-2,5) | |

| Maternal age at the time of delivery | |||||||

| ≤19 Years | 1,7 | 0,3 | 27,4 | 1 | 0,001 | 5,6(3,0-10,8) | |

| 20 a 34 Years | 30,5 | 2 | 0,001 | ||||

| ≥35 Years | 0,8 | 0,3 | 7,4 | 1 | 0,006 | 2,1(1,2-3,7) | |

| Constant | -3,5 | 0,7 | 28,4 | 1 | 0,001 | 0,03 | |

| Model 1 = caregiver’s education + marital status + caregiver’s occupation; Model 2 = Model 1 + alcohol consumption during pregnancy + type of delivery + length of hospital stay + nutritional status + interpregnancy interval; Model 3 = Model 2 + maternal age at time of pregnancy | |||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).