1. Introduction

Energy consumption is a fundamental driver of the global climate crisis. The twenty-first century has witnessed extensive discussions, both in academic circles and political arenas, about transitioning from fossil fuels to cleaner energy sources. Yet, a persistent global tension exists between the urgent need for climate action and the continued reliance on conventional energy systems (Newell, 2021; Svobodova et al., 2020). On one hand, we face the critical challenge of developing a clean energy economy that leaves no one behind, especially the most vulnerable populations, both locally and globally (Carley & Konisky, 2020; Gatto & Busato, 2020; Villavicencio Calzadilla & Mauger, 2018). On the other hand, questions arise regarding the sufficiency of renewable and cleaner energy sources in sustaining national and global economies (Guo et al., 2023; Halkos & Gkampoura, 2020).

Thus, the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), otherwise known as the Global Goals, place emphasis on 17 crucial areas necessary to attain sustainable development in the world. Of all these, Quality Education is aimed at ensuring that individuals have equal opportunities to learning and become enlightened to make critical and informed choices that can change their lives, their local communities, and the world in general. This goal underpins the acceleration towards achieving other SDGs, such as Affordable and Clean Energy, Climate Action, and Reduced Inequalities.

Consequently, as the world strives to balance economic development with environmental sustainability, the role of education in promoting energy literacy becomes even more critical, highlighting the interconnectedness of the SDGs and the collective action required to achieve them. Indeed, informed societies are better equipped to advocate for and implement sustainable energy solutions, address climate change proactively, and champion the rights and needs of the underprivileged, ensuring a holistic approach to sustainability (Cordero et al., 2020; Gibellato et al., 2023; Molthan-Hill et al., 2022).

Therefore, the transition to cleaner energy sources represents not just a technical shift, but a profound transformation of economic structures, cultural norms, and political systems, which involves reimagining and restructuring the ways energy is produced, distributed, and consumed, with the aim of minimizing ecological footprints. This transition is essential to mitigating climate change, yet its success hinges on widespread societal support and engagement (Ghorbani et al., 2024; Papadis & Tsatsaronis, 2020; Vanegas Cantarero, 2020).

Moreover, the principle of energy justice introduces an ethical dimension to the energy transition. It demands that the benefits and burdens of energy production and consumption are distributed fairly, ensuring that marginalized and vulnerable communities are neither disproportionately harmed by the negative impacts of traditional energy systems nor excluded from the opportunities presented by renewable energy (Finley-Brook & Holloman, 2016; Lewis et al., 2020).

1.1. Literature Review

The literature on energy literacy and energy justice spans a wide array of perspectives, highlighting the multifaceted nature of these concepts and their critical importance in guiding equitable energy transitions globally. Terms such as ‘justice’, in the environmental realm, have been associated with empowerment, struggle, and community (Pulido et al., 2016). Energy justice, as an emerging academic concept, seeks to address the unjust actions and consequences within the energy sector by integrating philosophical, legal, and social science perspectives. It emphasizes the need for a sustainable and equitable distribution of energy benefits, guided by ethical considerations (McCauley et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the literature also points to significant gaps in addressing energy justice, particularly in the context of China, where the application of Western justice principles may not fully capture the unique regional disparities and urban-rural inequalities (Wang & Lo, 2023). Similarly, in Sweden, there is a noted lack of explicit focus on energy justice, with issues of distributional justice being most raised, while procedural and recognition justice are often conflated (Ramasar et al., 2022). This suggests a broader need for a more nuanced understanding and application of justice principles that are sensitive to local contexts. Meanwhile, Gladwin et al. (2022) argue for a collaborative, global effort to promote sociocultural aspects of energy literacy as a foundation for energy and climate justice, based on research from an international educational project.

Moreover, the intersection of energy justice with broader developmental and environmental concerns is explored in the literature. For instance, the review of energy systems in least-developed countries emphasizes the centrality of energy access to development processes and calls for a pluralistic approach to research and policy at the nexus of energy justice and development (Kirshner & Omukuti, 2023). Furthermore, Elmallah et al.’s (2022) review of visioning documents from non-profits and frontline communities in the United States, highlights principles for a just energy future that include place-based approaches, addressing the root causes of inequality. The systematic review on energy poverty by (Guevara et al., 2023) explores the interconnectedness of energy poverty with climate justice and social development, pointing to the need for a more profound debate on justice to understand energy poverty’s role in society and development.

Consequently, the politics of achieving just outcomes in energy transitions are scrutinized by Shelton and Eakin (2022), who examine the role of advocacy in pushing for equitable policies and practices in the energy sector. Their findings suggest that advocacy is often driven by concerns over environmental degradation and the inaccessibility of governance processes, highlighting the need for more inclusive and equitable decision-making frameworks. In summary, the literature on energy literacy and energy justice presents a complex picture of the challenges and opportunities in achieving equitable energy transitions. It calls for a more integrated and context-sensitive approach to justice, emphasizing the importance of education, public engagement, and advocacy in shaping sustainable and just energy futures.

1.2. Rationale

On November 16, 2023, we had the privilege of participating in a significant event organized by Energy Dialogues in Baton Rouge, Louisiana (see

https://energy-dialogues.com/louisiana-energy-dialogues/). This exclusive event, part of the City Series, serves as a mobile think tank dedicated to fostering closed-door, in-depth discussions on energy-related topics, in collaboration with leading academic institutions across the nation. This invite-only gathering convened a diverse group of prominent figures from the energy sector, including students, policy advisors, industry executives, and scholars, for a day filled with rigorous discussions and business-oriented networking. The aim was to explore and forge new directions in a critical period of energy transition.

The agenda of the conference was robust, featuring discussions and keynotes on a variety of pertinent issues such as the future of lower-carbon fuels in Louisiana and their implications for balancing environmental justice, energy security, and the ongoing energy transition. Other notable topics included Louisiana’s role as a leader in the energy transition, the industry’s performance against current benchmarks and standards for tracking progress in energy transition, and the critical importance of community engagement and coastal restoration efforts in enhancing social acceptance and generating tangible, measurable benefits. The conference also delved into regional initiatives and best practices necessary for developing lower-carbon infrastructure, expanding transportation capacity, and ensuring regional energy proficiency.

Amidst the wealth of discussions, we noted a conspicuous absence of dialogue surrounding energy education or literacy. While community engagement was sporadically addressed, it largely diverged from our collective understanding as authors of the broader implications of such engagement. It was within the rich context of this conference that the initial idea for our study began to crystallize. We observed a critical need for energy literacy–the education that equips ‘all’ stakeholders with the knowledge of energy systems and the interconnections with all aspects of their quotidian existence, including transitions, consumption, fair distribution, as well as the associated socio-economic and environmental costs, and the importance of their involvement in the discourses surrounding them.

This study therefore systematically explores the interplay between energy literacy, transition, and justice as presented in scholarly works, while touching base with a crucial governmental source of information and an exemplary oil-producing region, with the goal of providing perspectives on advancing energy literacy and justice. The methods used are provided in

Section 2. Preliminary findings and supplemental insights are presented and discussed in

Section 3, while conclusions are provided in

Section 4.

2. Materials & Methods

We conducted a comprehensive search using the Scopus database, targeting documents containing ‘Energy Literacy,’ ‘Energy Transition,’ or ‘Energy Justice’ in their title, abstract, or keywords. This search was restricted to publications spanning from 2001 to 2023, yielding a total of 17,773 documents. Subsequent refinement within the results involved employing the search query ‘Energy Literacy’ OR ‘Energy Education’ AND ‘Energy Transition’ AND ‘Energy Justice,’ resulting in the retrieval of 48 documents. Following this, a bibliometric analysis was conducted, eliminating all publication types except original research articles, resulting in 33 documents. A thorough review of the full text for the concurrent use of the keywords led to the identification of 11 research articles, indicating a scarcity in the concurrent usage of the energy terms in scholarly works.

The bibliometric analysis of the 48 documents was followed by a thematic analysis of the 11 research articles. The thematic analysis involved reviewing the literature and exploring answers to key questions such as:

- 1)

What are the factors driving current energy transitions?

- 2)

What are the case studies of successful and ongoing energy transitions?

- 3)

What are the roles of energy literacy and justice in fostering energy transitions?

This was followed by analysis and synthesis into themes and subthemes. The major limitations in the reviewed literature are also discussed. Software packages such as Python, R, VOSviewer were used for analysis and visualization. Furthermore, we explored the YouTube channel owned by the United States Department of Energy (U.S. DOE) to corroborate perspectives on the study. Finally, we offer new insights, introducing the COMPEL Justice framework, for advancing energy literacy and justice, addressing critical gaps, and suggesting practical pathways for policy and community engagement.

3. Results & Discussion

3.1. Bibliometric Survey

Forty-eight documents from the years 2017 to 2023 were analyzed. The following subsections report findings from the keyword co-occurrence, co-authorship-by-country, and document type analyses.

3.1.1. Keyword Co-Occurrence Analysis

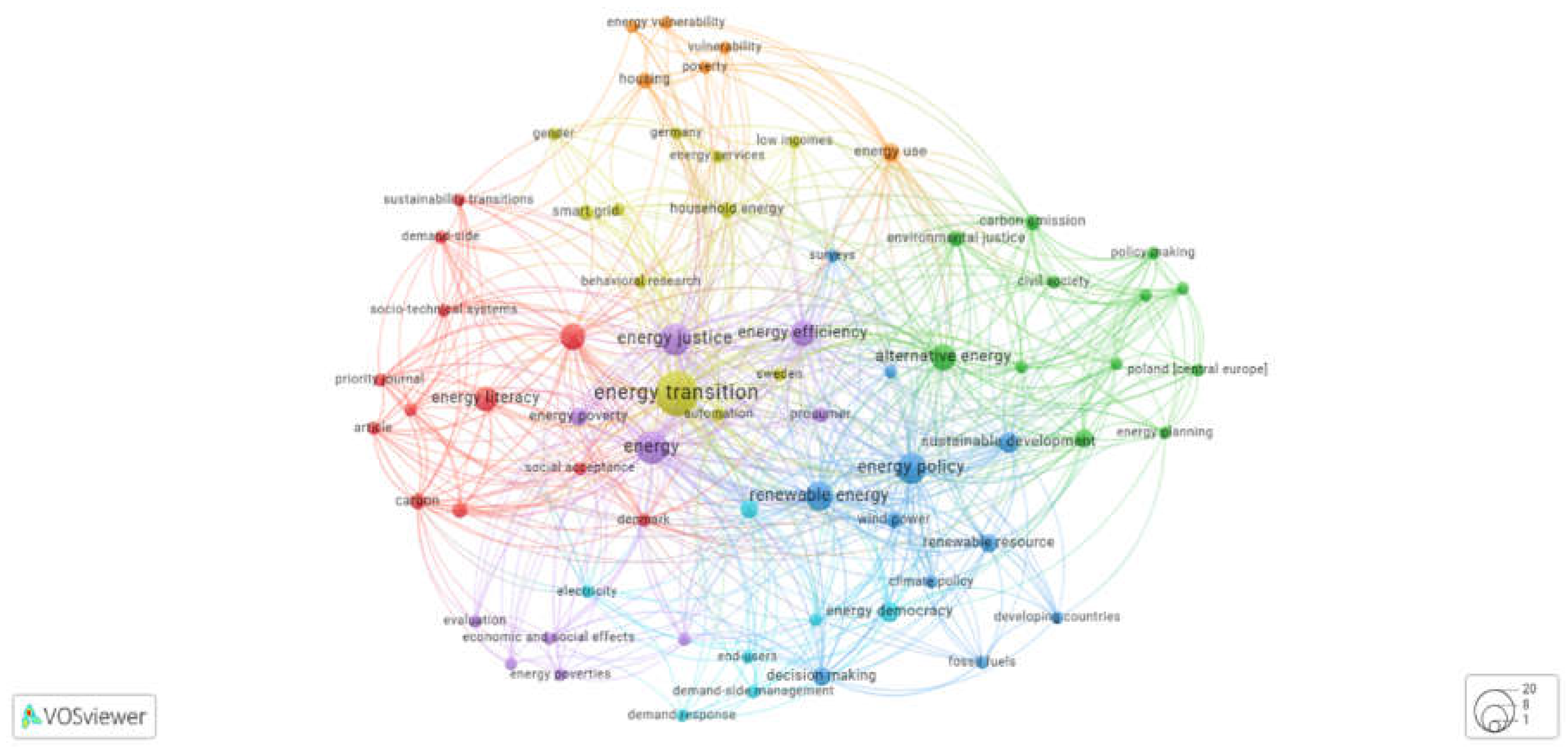

Lemmatization was initially employed to reduce repetition and redundancy, consolidating terms such as ‘renewable energies,’ ‘energy transitions,’ and ‘energy justices’ into their singular forms. From the initial set of 391 keywords—comprising both author and indexed terms—only 69 met the minimum occurrence threshold of two.

Figure 1 illustrates a bibliometric network where each keyword is represented by a node, with node size indicating keyword frequency. The strands between nodes signify co-occurrence. Notably, ‘energy transition’ is both the most frequently occurring and the most co-occurring keyword, followed by the generic term ‘energy.’ Although ‘energy justice’ records a slightly higher occurrence than ‘energy policy,’ it is surpassed by the latter in terms of co-occurrence.

In general, the publications around energy are highly interconnected and indicate a complex and closely linked research landscape in the field.

3.1.2. Co-Authorship-by-Country Analysis

Collaboration patterns and average citation counts among researchers from various countries are depicted in

Figure 2. The United Kingdom exhibits the highest number of research outputs, surpassing Germany and Denmark, which lead other 32 countries involved in the study. These countries also demonstrate significant international collaboration, as indicated by the connecting strands. In terms of average citations, the United Kingdom is followed by Germany, Norway, and Denmark. Further analysis reveals a positive correlation (r = 0.56) between average citations and the extent of collaboration, suggesting that higher citation rates are associated with greater collaborative efforts.

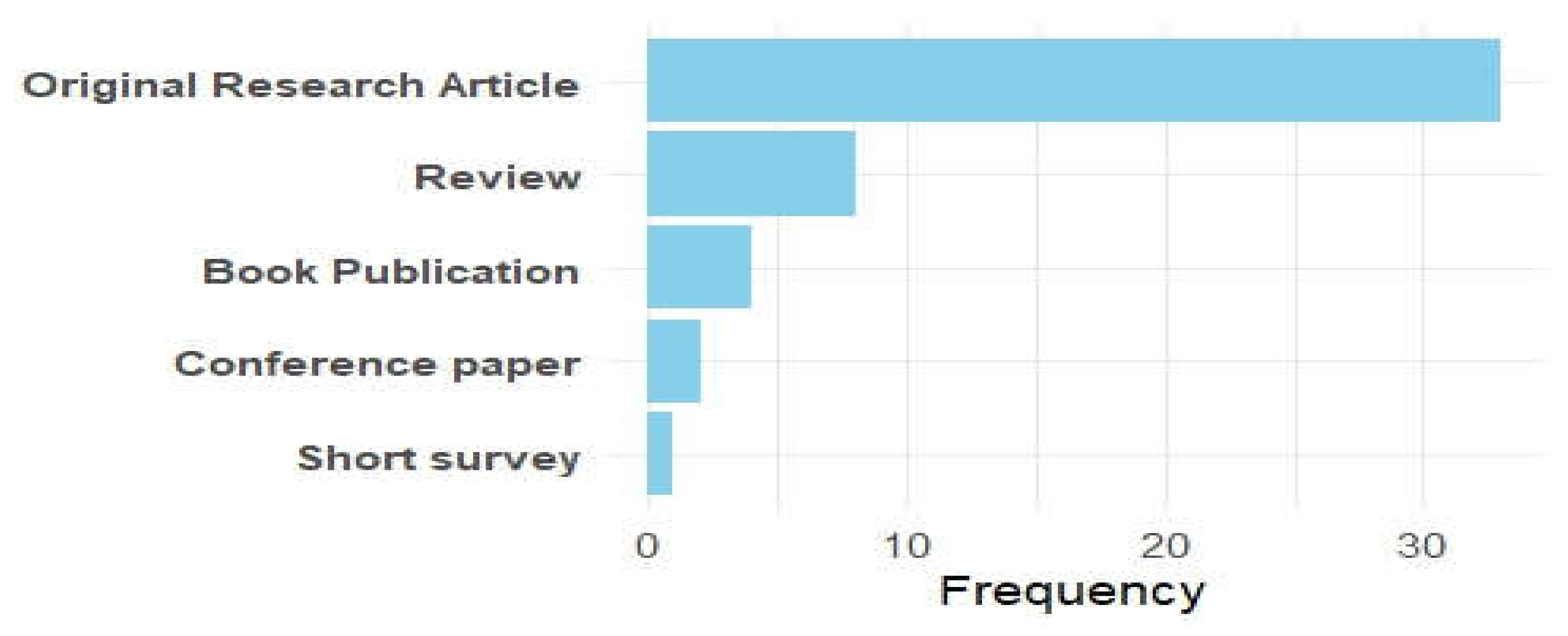

3.1.3. Document Type Analysis

The bibliography encompasses a diverse range of document types, including original research articles, literature reviews, conference contributions, and book publications (see

Figure 3). Original research articles constitute the majority at 68.8%, underlining their primary role in advancing knowledge in the field. Reviews account for 16.7% and are pivotal in synthesizing existing research, providing valuable insights for both researchers and practitioners. In contrast, conference papers make up only 4.2% of the bibliography, indicating a lesser impact from conference proceedings on the scholarly discourse surrounding energy literacy, transition, and justice

3.2. Thematic Analysis

This section delves into two pivotal themes: ‘Energy Transition and Issues of Energy Justice’ and ‘Energy Literacy: Concept, Challenges, and Opportunities,’ each encompassing various subthemes. These themes are intricately linked and essential for comprehending and facilitating the necessary shifts towards sustainable and equitable energy systems. Initially, we explore the dynamics of energy transitions and the embedded justice concerns that influence these shifts. Subsequently, the critical role of energy literacy in empowering individuals to engage actively and effectively in these transitions is examined.

3.2.1. Energy Transitions and Issues of Energy Justice

3.2.1.1. Dynamics of Energy Transition

The historical evolution of energy systems, from reliance on traditional biomass and manual labor to the adoption of sophisticated, technology-driven sources such as fossil fuels, nuclear energy, and renewables, underscores the transformative role of energy transitions in societal and environmental landscapes. These transitions are not merely technological shifts but encompass a broad spectrum of societal engagement, policy evolution, and the drive towards sustainability, aiming to decarbonize the economy while addressing energy justice issues (Sovacool, 2017). The movement towards decentralized energy systems, highlighted by the emergence of renewable energy prosumers, exemplifies the transformative potential inherent in energy transitions. These processes are complex and multifaceted, requiring meticulous planning, stakeholder involvement, and a dedicated focus on justice concerns, including job displacement and broader social impacts (Snow et al., 2022; Sovacool, 2017; Szulecki, 2018). Moreover, the interconnection between technological advancements and societal shifts forms the backbone of energy transitions, shaping new political subjectivities and influencing socio-political dynamics, thereby emphasizing the crucial role of education on energy ethics to engage stakeholders fully (Szulecki, 2018).

3.2.1.2. Drivers of Contemporary Energy Transitions and Energy Justice

Contemporary energy transitions are propelled by a confluence of technological innovations, economic dynamics, political policies, and social awareness. The reviewed literature presents case studies from various regions, such as Australia, Finland, and Sweden, demonstrating the successful harnessing of these drivers to pivot their energy systems towards greater sustainability (Snow et al., 2022; Sovacool, 2017). Conversely, Poland’s transition faces obstacles rooted in political, economic, and social spheres (Mrozowska et al., 2021), whereas the Nordic countries serve as a prime example of positive drive towards energy transitions, focusing on renewable energy sources, industrial efficiency, and robust policy support (Sovacool, 2017), thereby illustrating the diverse and interconnected drivers fueling the shift towards sustainable energy systems.

However, opposition from the fossil fuel industry retardates decarbonization efforts in the Nordic region (Sovacool, 2017). The fossil fuel sector’s resistance to change is highlighted by their continued investments in coal and oil companies, contradicting the region’s goals of achieving a fossil-free economy. Additionally, distrust in the energy sector, particularly regarding data sharing and control of energy assets, reflects skepticism towards initiatives like virtual power plants, further illustrating opposition from industry players. This opposition poses a significant challenge to the shift towards renewable energy and sustainable practices, emphasizing the need for overcoming industry barriers to achieve environmental goals in the Nordic region.

Energy justice encompasses three core tenets: distributive justice, procedural justice, and recognition justice, highlighting significant challenges such as energy poverty, unequal access to clean energy, and local community impacts of energy projects (Szulecki, 2018). The case studies illuminate the essential integration of justice considerations into energy policy and planning, advocating for a holistic approach that accounts for societal impacts and strives for distributive justice. Additionally, the literature reveals persistent challenges, including job losses, access to renewable technologies, and the impact on marginalized communities, especially in Nordic countries aiming for a virtually ‘fossil-free’ future by 2050 (Sovacool, 2017). The narrative also touches upon technological uncertainties, underscoring the ongoing need for innovation in renewable energy systems and carbon capture technologies as vital components for reducing carbon emissions.

3.2.1.3. Energy Democracy and Inclusivity in Smart Grid Design

Energy democracy emerges as a critical concept, delving into its political implications and advocating for inclusive governance and participatory decision-making processes. Defined through popular sovereignty (i.e., supremacy of the populace), participatory governance (i.e., direct involvement in decision-making procedures), and civic ownership (i.e., individual and community oversight), energy democracy presents a framework for analyzing and measuring democratic engagement in energy governance (Szulecki, 2018). This concept underscores the shift towards more democratic and participatory energy systems, highlighting the prosumer’s role as an emblematic citizen who not only consumes but also produces energy, thereby emphasizing the necessity of public influence and participation in energy decisions (Sweeney et al., 2015). The prosumer is an ideal citizen who not only consumes energy but also produces it, showcasing the shift towards more democratic and participatory energy systems (Szulecki, 2018).

The importance of inclusivity in smart grid design is addressed, pointing out the potential for exclusion without careful consideration (Tarasova & Rohracher, 2023). By integrating insights across disciplines, the literature reveals the complex layers of exclusion that can arise, advocating for designs that ensure no one is left behind. The study by Tarasova and Rohracher (2023) recommends incorporating energy-saving devices at no extra cost as a pathway towards equitable energy systems, showcasing a commitment to inclusivity in the transition towards smart energy systems.

3.2.2. Energy Literacy: Concept, Challenges and Opportunities

3.2.2.1. Energy Education vs. Energy Literacy in Context

Although energy education and energy literacy are closely related concepts within the field of energy studies, they serve distinct roles in shaping how individuals and societies engage with energy systems. Energy education primarily focuses on the structured dissemination of knowledge about energy systems to build a foundational conceptual understanding, whereas energy literacy extends this foundation into practical realms. This extension enables individuals to make informed decisions and actively participate in energy systems, enhancing efficiency and equity in energy use.

As reported in (Snow et al., 2022) which surveyed 39 Australian households with rooftop solar or battery storage, energy literacy involves possessing sufficient knowledge that empowers individuals to make informed, rational decisions about energy use. This knowledge transcends mere consumption metrics, facilitating active participation in emerging energy systems and allowing individuals to optimize their energy consumption, navigate renewable energy options, and select the best energy deals.

Consequently, high energy literacy plays a pivotal role in promoting sustainable energy behaviors (Campos & Marín-González, 2023; Szulecki, 2018).

Table 1 further delineates these differences, offering a side-by-side comparison of how energy education and energy literacy are defined, utilized, and alluded to in the reviewed literature. This comparison illustrates the transition from conceptual understanding to practical application where energy education underpins the development of energy literacy. Understanding these distinctions and interconnections is crucial for developing comprehensive energy policies and educational programs that effectively address both current needs and future challenges in energy management.

3.2.2.2. Challenges and Opportunities in Enhancing Energy Literacy

Enhancing energy literacy involves exploring a landscape riddled with obstacles, yet it also presents significant opportunities for fostering more inclusive and just energy transitions. A predominant issue is the limited knowledge among the public, leading to inequality in benefiting from advancements like smart grid developments (Snow et al., 2022). These challenges are compounded by varying levels of motivation, ability, and opportunity among individuals, which can create disparities in access and understanding, potentially hindering a successful energy transition and the realization of energy justice (Mrozowska et al., 2021; Snow et al., 2022; Tarasova & Rohracher, 2023). Additionally, potential conflicts may arise as energy literacy may not guarantee successful transition or justice, highlighting the need to address knowledge gaps for effective energy policies (Sovacool & Blyth, 2015). Energy literacy involves unpacking values and behaviors about energy, aiding in just energy transition and climate justice, potentially facing conflicts with prevailing capitalist and colonial legacies (Gladwin et al., 2022).

However, opportunities to improve energy literacy lie in increasing digital and energy competencies, engaging individuals in sustainability initiatives, and providing comprehensive support for learning about energy products and services (Fuller & Moore, 2018; Tarasova & Rohracher, 2023). Incorporating justice and ethics into energy education aligns with societal values such as fairness and transparency, enhancing user acceptance and facilitating a more inclusive and equitable energy transition (Fuller & Moore, 2018; Szulecki, 2018).

Energy literacy, successful energy transitions, and justice may occasionally find themselves at odds due to differing priorities and the complex socio-political, economic, and technological landscape. However, synergies can be achieved through inclusive governance, ethical decision-making, and targeted policies that address knowledge gaps and promote behavioral changes (Mrozowska et al., 2021; Sovacool & Blyth, 2015; Streimikiene et al., 2021). Recognizing and addressing potential conflicts while fostering synergies are crucial for navigating the ethical dimensions in energy education and ensuring a just energy transition. Meanwhile, the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration between Social Sciences and Humanities in addressing energy transition through smart consumption is emphasized (Robison et al., 2023).

3.2.2.3. Educational Approaches

Incorporating justice and ethics in energy education can enhance user acceptance by aligning with societal values such as fairness and transparency. For example, Fuller and Moore (2018) argue, following an 8-hour workshop comprising 13 college and graduate students using case studies and active learning exercises that encourage them to grapple with the ethical, justice, and societal dimensions of energy, that teaching about energy systems and transitions in a cohesive way requires diving deeply into the effects that decisions and technologies have on peoples’ lives and livelihoods. The authors also emphasized that, while transitioning away from carbon intensive industries is necessary for mitigating the effects of climate change, this transition must simultaneously take seriously the voices of those who will be impacted by the installation of new energy systems and the removal of old ones. After the workshop, students showed a stronger agreement that energy is a social problem, with six students changing their views from ‘agree’ to ‘strongly agree’ in the surveys conducted before and after the workshop.

Moreso, Living Labs offer a unique approach to making energy transitions more inclusive and responsive to societal needs by fostering a collaborative environment for innovation (Campos & Marín-González, 2023). Living Labs are like real-life classrooms where people come together to create and test new ideas, focusing on making energy use better and more sustainable by involving everyone’s opinions and ideas (Baccarne et al., 2016; Silva et al., 2019).

Similarly, the Motivation Opportunity Ability (MOA) framework developed by Snow et al. (2022) provide insights into the willingness and capability of individuals to participate in energy-saving activities, highlighting the importance of addressing values such as fairness and privacy to enhance participation in new energy technologies. The study finds that people’s decisions to share energy data or control their energy use are influenced by their values, like fairness and privacy, and that just because someone has solar panels does not mean they are comfortable with or skilled in using new energy technologies. It suggests that to get more people involved in using new energy technologies, there needs to be more effort in making these technologies familiar to them and involving them in designing future energy systems.

These approaches emphasize the need for inclusivity and engagement in designing and implementing energy systems, ensuring that the benefits of energy transitions are accessible to all.

3.3. Major Limitations in the Reviewed Studies

While the reviewed studies generally recognize the importance of advancing energy literacy and justice, they often fall short of providing a comprehensive operational framework that emphasizes these concepts universally. This oversight hampers the practical implementation and widespread adoption of initiatives crucial for systemic change.

For instance, Snow et al. (2022) address the integration of energy concepts within a motivational framework through their study with Australian solar panel owners. However, their methodology lacks a comprehensive approach to operationalizing these concepts across various societal layers, which is essential for universal applicability. This shortfall contributes to inconsistencies in the application and understanding of energy justice and literacy, potentially leading to uneven policy impacts and the exclusion of marginalized groups. Such limitations underscore the critical need for a framework that ensures holistic and equitable integration of these crucial energy concepts.

Furthermore, the absence of a unified framework in existing literature fosters fragmented efforts that address only isolated facets of energy literacy and justice. This fragmented approach significantly hinders the comprehensive advancement of energy policies and educational programs, adversely affecting the sustainability and inclusivity of energy transitions.

Without a clear operational framework integrating the interdependencies among energy literacy, transition, and justice, initiatives aimed at promoting these critical areas may not achieve their full potential, undermining broader energy transition goals. This oversight demonstrates a clear gap in current research and practice, highlighting the necessity for a new, holistic framework.

This new framework should not only address the conceptual and practical aspects of energy literacy and justice but also ensure their operational viability across diverse contexts. The following sections will elaborate on the importance of illustrating the linkages between the three critical energy terms—literacy, transition, and justice—and other components, setting the stage for the introduction of a comprehensive approach that can truly effect change.

3.4. Strategic Social Media and the COMPEL Justice Framework

In the contemporary digital era, social media platforms serve not only as conduits for information dissemination but also as critical tools for educational engagement and social advocacy. This section explores the strategic use of social media as a vital resource for enhancing public understanding of energy concepts, within the broader context of promoting energy literacy and justice. We analyze engagement metrics and user feedback from the DOE’s YouTube video series to offer valuable insights into how content delivery can be optimized to enhance viewer understanding and interaction.

Following the exploration of the research associated with the previously analyzed literature, we present a conceptual map that stakeholder groups may adopt to understand the interactions within the energy literacy-transition-justice nexus. We also introduce the COMPEL Justice framework, and its practical applications and implications within the context of oil-producing regions.

3.4.1. Social Media as a Critical Tool

Of the distinct types of educational systems in existence in human societies, the importance and roles of social media cannot be overemphasized. Thus, social media plays a crucial role in enhancing energy literacy and energy justice by providing a platform for information sharing, public engagement, and social perception analysis. For example, it enables the dissemination of energy-related information to citizens (Klein et al., 2023), facilitates public engagement in energy transitions (Kloppenburg & Boekelo, 2019; Mavrodieva et al., 2019), and offers insights into social perceptions on energy issues (Li et al., 2019). However, in enhancing energy literacy and justice, pedagogical methods adopted must be interestingly engaging to make the audience enduringly interested. Leveraging social media enables stakeholders to promote energy awareness, encourage collaborative impact, and share best practices for energy efficiency (Martinopoulou et al., 2023). Furthermore, social media analytics can help bridge gaps in energy markets, understand polarized social perceptions, and inform energy policies (Corbett & Savarimuthu, 2022; Li et al., 2019).

3.4.1.1. Engagement Analysis3.4.1.1.1. Engagement Metrics

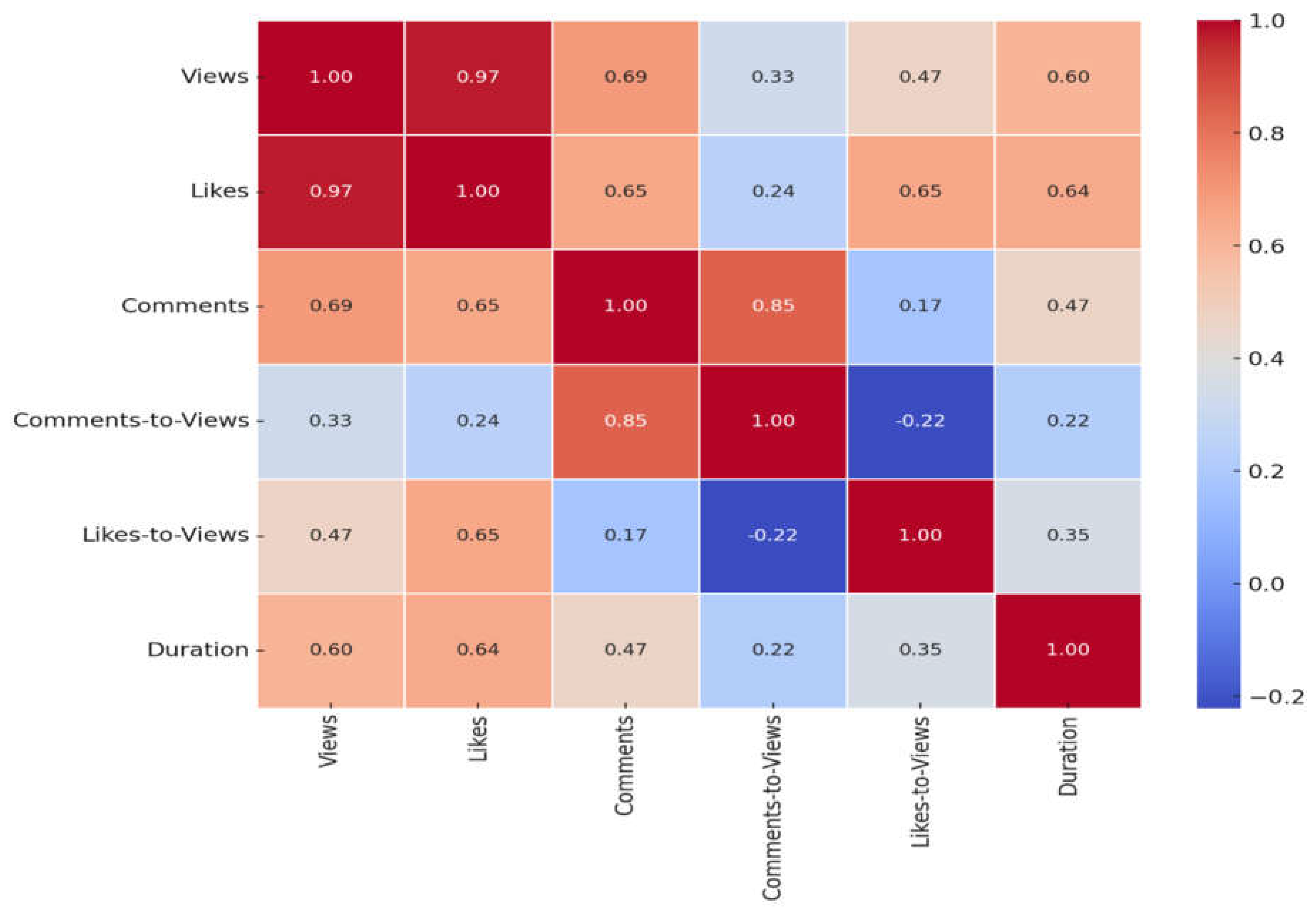

The ratios of Likes to Views and Comments to Views were calculated across all videos, serving as indicators of audience engagement.

Figure 4 displays a correlation matrix for different engagement metrics. A high correlation between Views and Likes (

r = 0.97) suggests that popular videos attract more likes. Comments also show significant correlation with Views (

r = 0.69) and Likes (

r = 0.65), with a stronger correlation observed with the Comments to Views ratio (

r = 0.85). The duration of videos shows moderate correlations with Views and Likes, indicating that video length can impact performance.

Notably, videos with more Likes tend to maintain a higher Likes to Views ratio (r = 0.65), emphasizing effective engagement in popular content. A strong correlation between higher views, likes, and comments indicates that more engaging content encourages viewers to interact more extensively.

3.4.1.1.2. Sentiment Analysis of User Comments

The sentiment analysis provides a valuable quantitative measure of how content is perceived, aiding in content refinement (Medhat et al., 2014). Using Python software, sentiment analysis was conducted on user comments, revealing a generally positive sentiment with an average score of 0.197 and a standard deviation of 0.185. This indicates a mild positive reception with moderate variability in viewer sentiment. Notably, at least 25% of comments are neutral, with a median sentiment of 0.225, suggesting mildly positive viewer feedback. Insights from sentiment analysis can guide the tone and style of future videos, ensuring content remains engaging and effectively received.

The overall mildly positive sentiment signifies that the content is well-received. However, comments, when humanly reviewed, indicate obligatory viewing (e.g., assignment from teacher to students) and concerns over background music suggest the need for strategies to enhance the intrinsic appeal of the content. While leveraging similar digital media platforms effectively can broaden outreach and enhance educational impact, continuous optimization of content presentation and format is essential to maintain and increase viewer engagement.

3.4.2. Conceptual Map for Energy Literacy-Transition-Justice Nexus

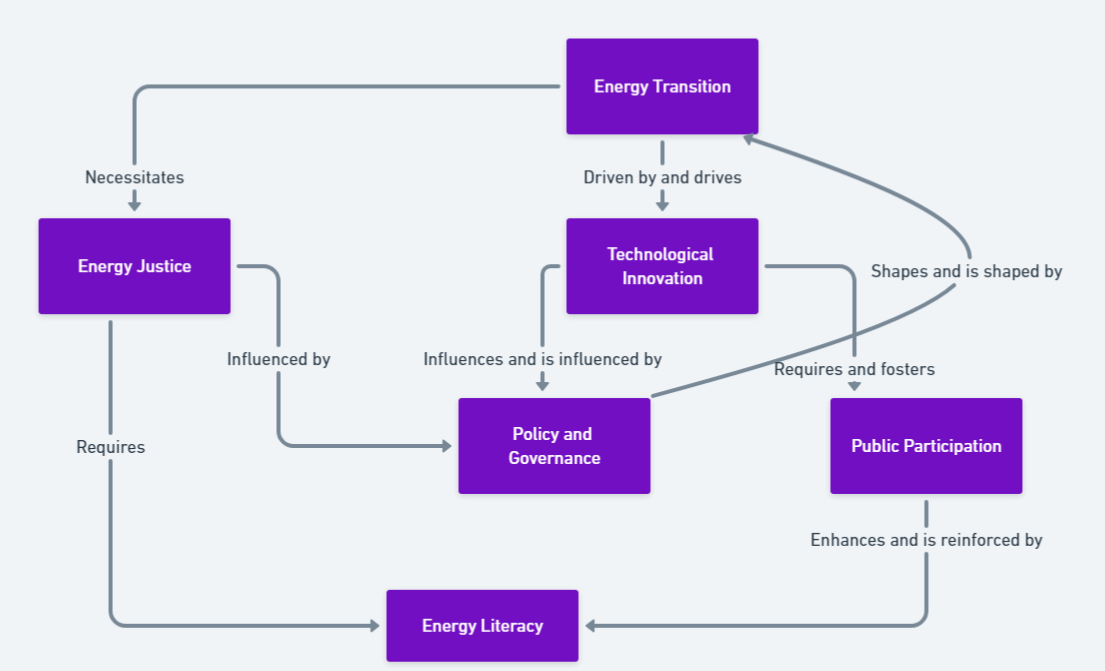

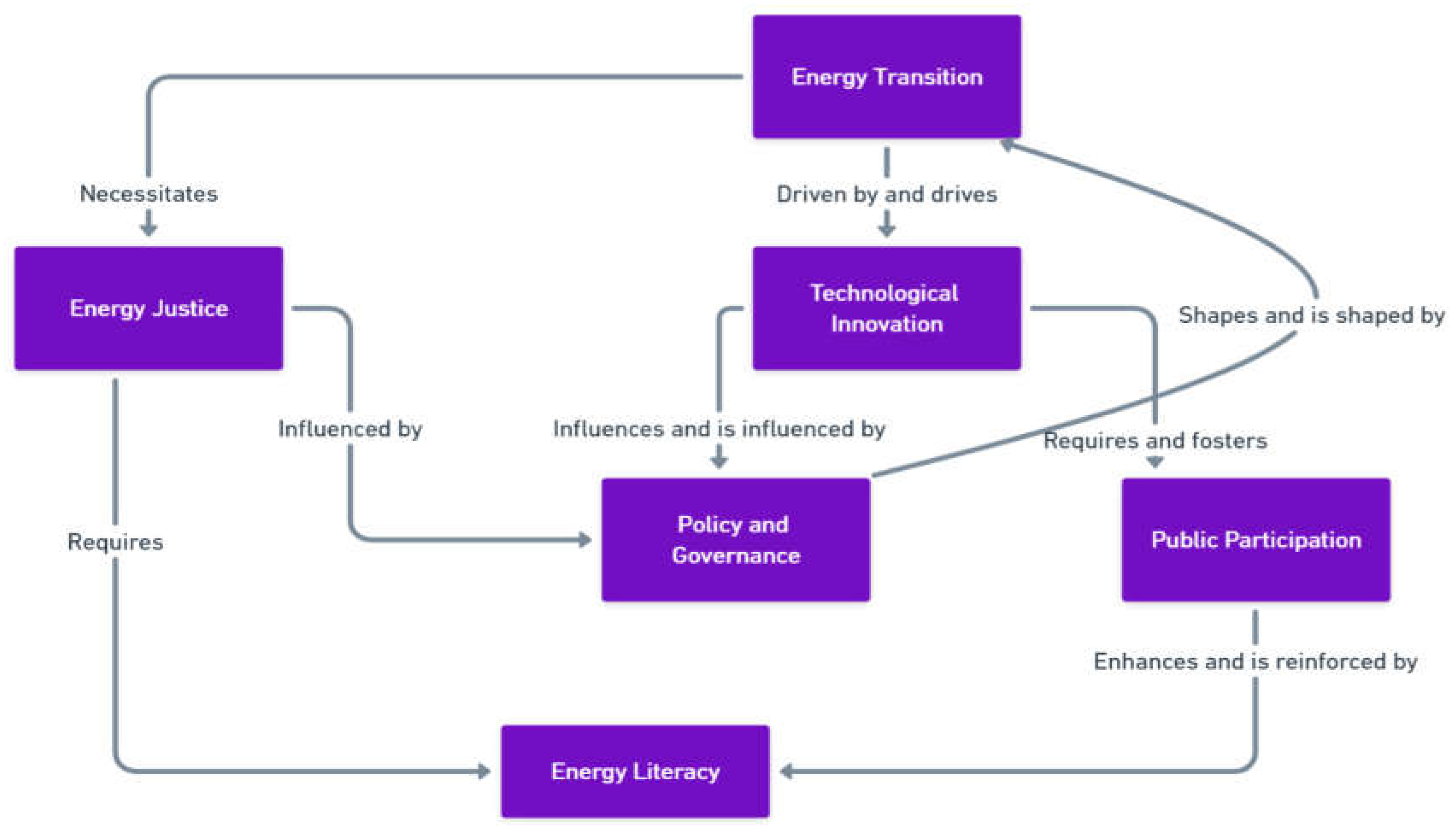

In fostering energy literacy and justice, the use of a conceptual map, as presented in

Figure 5, can offer significant benefits to various stakeholder groups. The map synthesizes the salient paradigms and emphasis enunciated in the reviewed literature. It provides a structured yet flexible approach for understanding the intricate dynamics of energy transition, facilitating cross-disciplinary communication, promoting holistic thinking, and ensuring comprehensive consideration of the facets of energy literacy and justice in decision-making and educational strategies.

Educators, for example, in primary, secondary, tertiary, and even influential yet untraditional (e.g., social media platforms), education systems are pivotal in shaping society’s understanding of energy issues. The conceptual map aids in curricular development, highlighting the interplay between energy concepts, thereby structuring lessons that foster an integrated understanding of energy transitions and their relation to technological advancements, policy formation, and societal involvement. It also serves as a benchmark to evaluate educational programs against the essential topics outlined for a sustainable energy future.

Meanwhile, activists can utilize the map to strategize their advocacy efforts, pinpointing crucial areas for impactful energy transition and justice initiatives. By conveying the interconnectedness of each element within the energy landscape, the map becomes a powerful tool for raising awareness and rallying public support for pertinent issues.

Furthermore, community leaders, tasked with the welfare and development of their constituencies, can draw upon the map for informed policy-making that encompasses the entire spectrum of considerations for an equitable energy shift. It assists in identifying priority areas for investment and resource allocation, such as educational initiatives or infrastructural innovations, and serves as a conversation starter for consensus-building with community members and other stakeholders.

Additionally, professionals in the energy sector can leverage the map to ensure new projects are conceptualized with justice and literacy in mind, resulting in outcomes that are both sustainable and community-approved. This map also emphasizes the necessity for collaboration amongst stakeholders and can catalyze stakeholder engagement by illustrating the interconnected needs and contributions of all involved in the energy ecosystem.

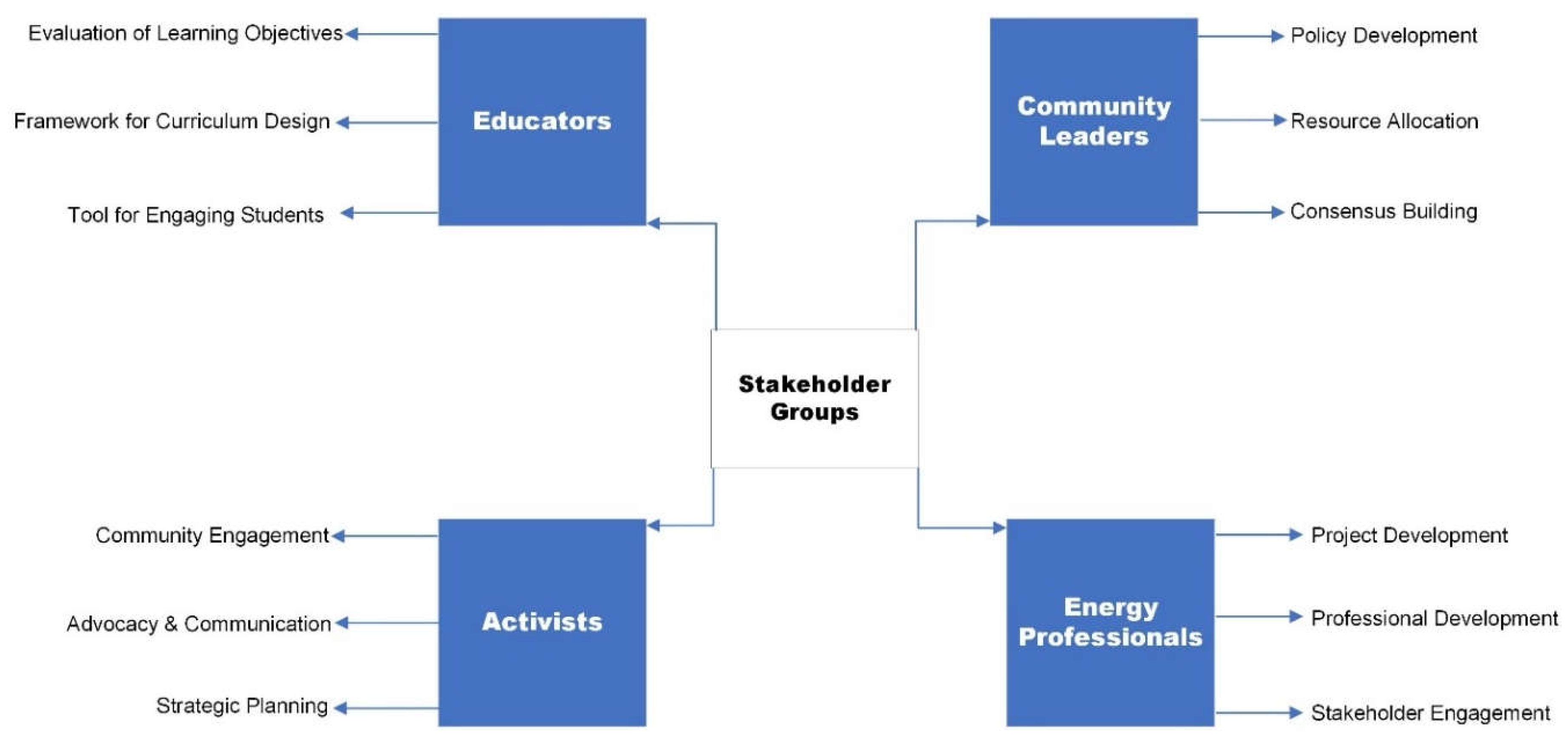

Figure 6 encapsulates the stated influencing areas the four distinct stakeholder groups can leverage the conceptual map.

3.4.3. The COMPEL Justice Framework

We propose the COMPEL Justice (Communities Prepared for Energy Literacy and Justice) framework, designed to facilitate consolidated engagement and education on energy literacy and justice, ensuring that all community members, especially those in vulnerable positions, are empowered to actively participate in energy decisions. The components of the framework (including educational initiatives, community engagement, advocacy and policy influence, stakeholder collaboration, and monitoring and evaluation) and the implementation strategy illustrated in

Figure 7, with details in Table 2, are hinged on communication and publicity, education and mobilization, and partnership, , and leadership.

Succinctly, the framework emphasizes strategies to disseminate information effectively, efforts to reach diverse community segments, actions to encourage active participation and advocacy, collaboration with stakeholders across various sectors, learning initiatives tailored to all community members, and the development of leaders within communities to sustain efforts.

In addition, it represents a structured approach to integrating energy literacy and justice into the fabric of community and policy initiatives, aiming to drive meaningful change, ensuring that advancements in energy technologies and efficiency are accessible and beneficial to all community members.

3.4.3.1. Practical Application and Implications for an Oil Producing Region

We provide practical application and implications for implementing the COMPEL Justice framework in oil-producing regions like Louisiana. This entails deploying targeted initiatives tailored to the unique environmental challenges and socio-economic dynamics of such regions. These initiatives are designed to leverage the significant economic impact of the oil industry while addressing crucial environmental and social justice issues. In Louisiana, for example, both regional and local struggles historically matched with distrust associated with government practices and the impacts of the oil industry cannot be dismissed. Thus, government endeavors as well as the industry’s preceding and foregoing activities are critical for the application of the framework as emphasized subsequently.

3.4.3.1.1. Louisiana’s Economy

Louisiana’s GDP growth and economic data reflect its economic dependency on oil, with industries related to oil production dominating its economic landscape. For instance, in 2023, Louisiana achieved a GDP valuation of $219.1 billion, marking an increase of 18,400% over 5 years from 2018 (IBIS World, 2024). This substantial growth underscores the economic dominance of industries like Petroleum Refining, Oil Drilling & Gas Extraction, and Plastic & Resin Manufacturing, which collectively account for approximately 87% of this revenue. The Baton Rouge Refinery, operated by ExxonMobil and the largest in the state, is the fifth largest in the United States and the thirteenth globally (Hemmerling et al., 2024; Scott & Upton, 2019). Such economic powerhouses illustrate the potential for impactful sustainability and justice initiatives within the sector.

Additionally, the median household income (MHI) in Louisiana stands at $57,852, with Baton Rouge slightly lower at $50,155 (US Census Bureau, 2024). The per capita incomes (PCIs) are $32,981 and $33,910, respectively, which contrasts with the national averages of $75,149 (MHI) and $41,261 (PCI) (US Census Bureau, 2024). The disparity between local income levels and national averages underscores the need for initiatives–such as the COMPEL Justice–that bridge economic gaps and promote sustainable development.

3.4.3.1.2. Exemplary Projects and Their Implications

Detailed in Table 3 are hypothetical projects demonstrating how the COMPEL Justice framework can be practically applied. These projects are designed to address specific regional challenges and leverage local industry dynamics to promote sustainable and just practices. Targeted social media campaigns, for instance, can significantly alter public perceptions by emphasizing the benefits of sustainable energy sources and the importance of energy justice. By providing accessible, relevant information through these campaigns and other initiatives, local communities are empowered to participate actively in energy-related decision-making. This enhanced engagement is expected to increase public awareness and support for policies that promote environmental sustainability and equitable energy practices.

The targeted application of the framework in Louisiana offers a model for other oil-producing regions, demonstrating how integrating energy literacy and justice into the fabric of local economies and communities can lead to substantial positive change. Moreover, this approach invites stakeholders across the energy sector to adopt and adapt these strategies, ensuring that economic growth aligns with sustainability and justice principles.

3.4.3.1.3. Historical Distrust and Community Empowerment

Considering Louisiana as an exemplary primary location of application for the framework, it is important to keep the historical context of this oil producing region central as well as the implications this history has for the practical outcomes of this framework’s application. This understanding of the historical context will highlight the importance of a just and community-centered energy transition, especially as this model is applied to other oil producing regions. With oil production also comes the danger of manmade disasters, namely oil spills, which have drastic long-term and short-term impacts not just on marine life and the local ecosystems (Kingston, 2002) but the local economy and livelihoods of those who rely on fisheries and marine ecosystems for their sustenance and household income (Andrews et al., 2021). And it is noted that the adversely impacted lived experiences of those communities rattled by oil spills can lead to distrust. In Louisiana, particularly following the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill, there has been high levels of distrust in institutional actors, both industry and government, and even distrust for scientists (Simon-Friedt et al., 2016), documented throughout Louisiana communities. These high levels of distrust for industry actors, namely BP in the case of the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill as well as federal government actors, has held steady for Louisiana communities over time (Cope et al., 2016). There was also associated distrust for scientists which stemmed from a lack of communication of the risks and life-altering information about the oil spill in fishery communities, also lending to increased risk perception by community members (Simon-Friedt et al., 2016).

Understandably, oil producing regions also experience severe natural disasters, driven by climate change and its fossil fuel drivers. Perhaps unsurprisingly, these disasters and the responses to them can lead to distrust of the same institutional entities both locally and globally (Miller, 2016), as similarly noted in oil spills. Worth mentioning is one of the largest disasters in national history, Hurricane Katrina, and the subsequent disaster responses did not bode well for Louisiana residents’ trust in government, at all levels, nor for the residents’ trust in environmental professionals (Nelson et al., 2007).

Overarchingly, communities’ historical distrust of institutions in environmental realms poses a limitation of energy literacy and justice efforts in that, dependent upon the disseminators of educational information provided to communities for the energy transition, community stakeholders may still experience hesitancy due to held distrust. This hesitancy could serve as a threat to the multiple-stakeholder cohesion necessary for the success of such a transition. However, Louisiana also offers a model of how disasters, both manmade and natural, and the resultantly exhibited distrust in institutions, make local community trust within communities ever relevant. Common among all outcomes of disaster in Louisiana, trust in fellow community members has the opportunity to flourish, especially as local communities have proven to rise, through civic duty and engagement, to address the perceived failures of their institutions. In response to increased risk perception of the BP oil spill and the distrust of scientists, communities began placing their trust within fellow community members to gauge risks more accurately (Simon-Friedt et al., 2016). Similarly, with natural disasters such as the Great Floods of 2016, Louisiana communities’ civic duty to their fellow community instilled trust within and between communities. Community organizations mobilized effectively in response to governmental inaction following the 2016 floods (Yeo et al., 2017). Hurricane Katrina was also an exemplary and catastrophic episode where community trust and reliance played a primary role in the onset of the disaster during evacuation (Eisenman et al., 2007), and during the immediate aftermath for support efforts and toward pathways to longer term survival and community revitalization (Hawkins & Maurer, 2009).

It is also important to note that with previous disasters experienced, in which institutional distrust was present, the same distrust was more likely to echo again in subsequent disasters (Darr et al., 2019). Therefore, distrust can continue based on historical experiences. Other studies have noted that, in terms of behavior change, community distrust of institutions was a primary barrier to change and that reassurance from local community members was integral to instituting and sustaining change (Brown et al., 2014). This historic institutional distrust and civic trust further highlights the importance of the COMPEL Justice framework’s community-centered components, outlined in

Table 2. and projects outlined in

Table 3., towards energy literacy and justice amid the forward-looking energy transition states.

As previously found, trust is integral to change. And, in this energy transition, with multiple stakeholders present for such a change, trust between those stakeholders must be assured. Community trust can serve as a pivotal point of energy transition goals, perhaps presenting an avenue of cohesion building between all stakeholders that overcomes the regionally historic tensions counterintuitive to the transition. Therefore, it is crucial that the community stakeholder engagement remain central to energy literacy and justice efforts. Maintaining community focus can aid in the success of energy transitions in oil producing regions, such as Louisiana, ensuring justice and collaboration that such a transition necessitates.

3.4.3.1.4. Decarbonization Projects: Beyond Short-Term Benefits

Louisiana, along with several other U.S. states and countries in developed economies, has set an ambitious goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050 (Chen et al., 2022; EPA, 2023). According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), this target is contingent upon deploying a diverse portfolio of low-emission technologies and extensive emissions reduction strategies across the energy sector (IEA, 2023). A critical element of this transition is the rapid increase in low-emissions electricity, coupled with a firm directive to halt the construction of new unabated coal plants beyond those already underway as of early 2023 (IEA, 2023; Kabeyi & Olanrewaju, 2022).

The pertinent roles of hydrogen and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies in mitigating emissions, particularly within the heavy industry and long-distance transport sectors have also been highlighted (Anandarajah et al., 2013; McLaughlin et al., 2023). IEA (2023) cautions that without substantial policy improvements before 2030, maintaining global temperature increases within 1.5°C by 2100 will become significantly more difficult. This would require a dramatic increase in CO2 removal from the atmosphere after 2050 (IEA, 2023).

Carbon neutrality ambitions within localities, states and countries require a great deal of stakeholder engagement, and in short, energy literacy. Therefore, decarbonization initiatives, such as CCUS, currently being advanced in Louisiana by the oil industry and agencies like the U.S. DOE (Smith, 2023), must not only communicate promises of tangible community benefits, including job creation and enhanced infrastructure, but must ensure persistent community engagement in a transparent manner. It would be advantageous to effectively determine and communicate whether potential and existing decarbonization projects and clean energy development could resolve energy inequities in the concerned communities.

Fostering energy literacy among community members is vital, as it enables them to pose critical questions during discussions and forums related to such decarbonization projects. Thus, the discourse should extend beyond short-term benefits to encompass long-term, transgenerational safety and security for everyone. Aligning decarbonization strategies closely with the principles of COMPEL Justice can ensure that energy transition in oil-producing regions like Louisiana is not only effective but also equitable and sustainable, addressing the complex needs and values of the community. Practically, all entities should recognize that in the realm of energy and environmental stewardship, everyone is a stakeholder.

4. Conclusions

This study has systematically examined the interplay between energy literacy, energy transition, and justice, providing a comprehensive analysis through a bibliometric survey and thematic exploration of existing literature. Our findings emphasize the crucial role of energy literacy in enabling informed decision-making that supports equitable energy transitions and enhances sustainability efforts globally.

In addition, the introduction of the COMPEL Justice framework represents a significant stride towards integrating energy literacy and justice into community and policy initiatives. This framework not only addresses the conceptual and practical gaps identified in the reviewed studies but also offers a robust structure for operationalizing these concepts across diverse socio-economic contexts. The focus on comprehensive community engagement and education ensures that all stakeholders, especially those in vulnerable positions, are empowered to participate effectively in energy decisions.

Furthermore, the practical application of the COMPEL Justice framework in Louisiana, as exemplified through targeted, albeit hypothetical and potential, initiatives, aims to harness the economic influence of the oil industry to foster sustainable and just energy practices, addressing both environmental challenges and socio-economic disparities.

Moreover, the study has revealed that while there is substantial progress in the areas of energy transition, significant challenges remain, particularly in achieving a cohesive integration of the crucial energy concepts in the energy literature. The disparity in energy literacy and justice across different regions emphasizes the need for a more tailored approach that considers local contexts and needs.

Future research should focus on further refining and testing the COMPEL Justice framework in various settings, exploring its adaptability and impact in different cultural and economic landscapes. Additionally, there is a need for continued advocacy to ensure that energy policies not only promote sustainability but also prioritize equity and justice. This involves engaging a broader spectrum of stakeholders, including policymakers, educators, community leaders, and the public in general, to foster a more inclusive and comprehensive approach to energy transition.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.A. and M.R.; methodology, O.A; software, O.A.; validation, O.A., formal analysis, O.A. and C.S.; investigation, O.A. and C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, O.A.; writing—review and editing, O.A. and C.S.; visualization, O.A.; supervision, M.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Trinity Johnson for insightful contributions during discussions and brainstorming sessions at the Environmental Policy Research group meetings held at Louisiana State University, which enriched the development of the exemplary projects outlined in Table 3.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anandarajah, G., McDowall, W., & Ekins, P. (2013). Decarbonising road transport with hydrogen and electricity: Long term global technology learning scenarios. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 38(8), 3419-3432. [CrossRef]

- Andrews, N., Bennett, N. J., Le Billon, P., Green, S. J., Cisneros-Montemayor, A. M., Amongin, S., Gray, N. J., & Sumaila, U. R. (2021). Oil, fisheries and coastal communities: A review of impacts on the environment, livelihoods, space and governance. Energy Research & Social Science, 75, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Baccarne, B., Logghe, S., Schuurman, D., & De Marez, L. (2016). Governing Quintuple Helix Innovation: Urban Living Labs and Socio-Ecological Entrepreneurship. Technology Innovation Management Review, 6(3), 22–30. [CrossRef]

- Brown, H. L., Bos, D. G., Walsh, C. J., Fletcher, T. D., & RossRakesh, S. (2014). More than money: how multiple factors influence householder participation in at-source stormwater management. Journal of Environmental Management and Planning, 59(1), 79–97. [CrossRef]

- Campos, I., & Marín-González, E. (2023). Renewable energy Living Labs through the lenses of responsible innovation: building an inclusive, reflexive, and sustainable energy transition. Journal of Responsible Innovation, 10(1). [CrossRef]

- Carley, S., & Konisky, D. M. (2020). The justice and equity implications of the clean energy transition. Nature Energy, 5(8), 569–577. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Msigwa, G., Yang, M., Osman, A. I., Fawzy, S., Rooney, D. W., & Yap, P. S. (2022). Strategies to achieve a carbon neutral society: a review. Environmental Chemistry Letters, 20(4), 2277-2310. [CrossRef]

- Cope, M. R., Slack, T., Blanchard, T. C., & Lee, M. R. (2016). It's not whether you win or lose, it's how you place the blame: Shifting perceptions of Recreancy in the context of the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Rural Sociology, 81(3), 295-315. [CrossRef]

- Corbett, J., & Savarimuthu, B. T. R. (2022). From tweets to insights: A social media analysis of the emotion discourse of sustainable energy in the United States. Energy Research & Social Science, 89, 102515. [CrossRef]

- Cordero, E. C., Centeno, D., & Todd, A. M. (2020). The role of climate change education on individual lifetime carbon emissions. PLoS ONE, 15(2). [CrossRef]

- Darr, J. P., Cate, S. D., & Moak, D. S. (2019). Who’ll Stop the Rain? Repeated Disasters and Attitudes Toward Government. Social Science Quarterly, 100(7), 2581-2593. [CrossRef]

- Dias, R. A., Rios de Paula, M., Silva Rocha Rizol, P. M., Matelli, J. A., Rodrigues de Mattos, C., & Perrella Balestieri, J. A. (2021). Energy education: Reflections over the last fifteen years. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 141, 110845. [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, D. P., Cordasco, K. M., Asch, S., Golden, J. F., & Glik, D. (2007). Disaster planning and risk communication with vulnerable communities: lessons from Hurricane Katrina. American journal of public health, 97(Supplement 1), S109-S115. [CrossRef]

- Elmallah, S., Reames, T. G., & Spurlock, C. A. (2022). Frontlining energy justice: Visioning principles for energy transitions from community-based organizations in the United States. Energy Research & Social Science, 94, 102855. [CrossRef]

- EPA. (2023, December 20). Louisiana Priority Climate Action Plan. https://www.epa.gov/system/files/documents/2024-02/louisiana-5d-02f36401-0-pcap-final-with-appendices.pdf.

- Finley-Brook, M., & Holloman, E. (2016). Empowering Energy Justice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(9), 926. [CrossRef]

- Fuller, J., & Moore, S. (2018). Pedagogy for the ethical dimensions of energy transitions from Ethiopia to appalachia. Case Studies in the Environment, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Gatto, A., & Busato, F. (2020). Energy vulnerability around the world: The global energy vulnerability index (GEVI). Journal of Cleaner Production, 253, 118691. [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, Y., Zhang, S. E., Nwaila, G. T., Bourdeau, J. E., & Rose, D. H. (2024). Embracing a diverse approach to a globally inclusive green energy transition: Moving beyond decarbonisation and recognising realistic carbon reduction strategies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 434, 140414. [CrossRef]

- Gibellato, S., Ballestra, L. V., Fiano, F., Graziano, D., & Luca Gregori, G. (2023). The impact of education on the Energy Trilemma Index: A sustainable innovativeness perspective for resilient energy systems. Applied Energy, 330, 120352. [CrossRef]

- Gladwin, D., Karsgaard, C., & Shultz, L. (2022). Collaborative learning on energy justice: International youth perspectives on energy literacy and climate justice. Journal of Environmental Education, 53(5), 251–260. [CrossRef]

- Guevara, Z., Mendoza-Tinoco, D., & Silva, D. (2023). The theoretical peculiarities of energy poverty research: A systematic literature review. Energy Research & Social Science, 105, 103274. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q., Abbas, S., AbdulKareem, H. K. K., Shuaibu, M. S., Khudoykulov, K., & Saha, T. (2023). Devising strategies for sustainable development in sub-Saharan Africa: The roles of renewable, non-renewable energy, and natural resources. Energy, 284, 128713. [CrossRef]

- Halkos, G. E., & Gkampoura, E.-C. (2020). Reviewing Usage, Potentials, and Limitations of Renewable Energy Sources. Energies, 13(11), 2906. [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, R. L., & Maurer, K. (2010). Bonding, Bridging and Linking: How Social Capital Operated in New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina. The British Journal of Social Work, 40(6), 1777–1793. [CrossRef]

- Hemmerling, S. A., Haertling, A., Shao, W., Di Leonardo, D., Grismore, A., & Dausman, A. (2024). “You turn the tap on, the water’s there, and you just think everything’s fine”: a mixed methods approach to understanding public perceptions of groundwater management in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, USA. Frontiers in Water, 6. [CrossRef]

- IBIS World. (2024). Louisiana - State Economic Profile.

- IEA (2023). Net Zero Roadmap A Global Pathway to Keep the 1.5 °C Goal in Reach https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/9a698da4-4002-4e53-8ef3-631d8971bf84/NetZeroRoadmap_AGlobalPathwaytoKeepthe1.5CGoalinReach-2023Update.pdf.

- Kabeyi, M. J. B., & Olanrewaju, O. A. (2022). Sustainable energy transition for renewable and low carbon grid electricity generation and supply. Frontiers in Energy research, 9. [CrossRef]

- Kingston, P. F. (2002). Long-term Environmental Impact of Oil Spills. Spill Science & Technology Bulletin, 7(1-2), 53–61. [CrossRef]

- Kirshner, J., & Omukuti, J. (2023). Energy justice and development. In Handbook on Energy Justice (pp. 79–93). Edward Elgar Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Klein, L., Kumar, A., Wolff, A., & Naqvi, B. (2023). Understanding the role of digitalization and social media on energy citizenship. Open Research Europe, 3, 6. [CrossRef]

- Kloppenburg, S., & Boekelo, M. (2019). Digital platforms and the future of energy provisioning: Promises and perils for the next phase of the energy transition. Energy Research & Social Science, 49, 68–73. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, J., Hernández, D., & Geronimus, A. T. (2020). Energy efficiency as energy justice: addressing racial inequities through investments in people and places. Energy Efficiency, 13(3), 419–432. [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Crowe, J., Leifer, D., Zou, L., & Schoof, J. (2019). Beyond big data: Social media challenges and opportunities for understanding social perception of energy. Energy Research & Social Science, 56, 101217. [CrossRef]

- Martinopoulou, E., Dimara, A., Tsita, A., Gonzalez, S. L. H., Marin-Perez, R., Segado, J. A. S., Fraternali, P., Krinidis, S., Anagnostopoulos, C.-N., Ioannidis, D., & Tzovaras, D. (2023). A Novel Social Collaboration Platform for Enhancing Energy Awareness (pp. 195–206). [CrossRef]

- Mavrodieva, Rachman, Harahap, & Shaw. (2019). Role of Social Media as a Soft Power Tool in Raising Public Awareness and Engagement in Addressing Climate Change. Climate, 7(10), 122. [CrossRef]

- McCauley, D., Ramasar, V., Heffron, R. J., Sovacool, B. K., Mebratu, D., & Mundaca, L. (2019). Energy justice in the transition to low carbon energy systems: Exploring key themes in interdisciplinary research. Applied Energy, 233–234, 916–921. [CrossRef]

- Medhat, W., Hassan, A., & Korashy, H. (2014). Sentiment analysis algorithms and applications: A survey. Ain Shams Engineering Journal, 5(4), 1093–1113. [CrossRef]

- McLaughlin, H., Littlefield, A. A., Menefee, M., Kinzer, A., Hull, T., Sovacool, B. K., ... & Griffiths, S. (2023). Carbon capture utilization and storage in review: Sociotechnical implications for a carbon reliant world. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 177, 113215. [CrossRef]

- Miller, D. S. (2016). Public trust in the aftermath of natural and na-technological disasters: Hurricane Katrina and the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear incident. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 36(5/6), 410-431. [CrossRef]

- Molthan-Hill, P., Blaj-Ward, L., Mbah, M. F., & Ledley, T. S. (2022). Climate Change Education at Universities: Relevance and Strategies for Every Discipline. In Handbook of Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation (pp. 3395–3457). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Mrozowska, S., Wendt, J. A., & Tomaszewski, K. (2021). The challenges of poland’s energy transition. Energies, 14(23). [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M., Ehrenfeucht, R., & Laska, S. (2007). Planning, plans, and people: Professional expertise, local knowledge, and governmental action in post-Hurricane Katrina New Orleans. Cityscape, 9(3), 23-52. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1090161.

- Newell, P. (2021). Power Shift (1st ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Papadis, E., & Tsatsaronis, G. (2020). Challenges in the decarbonization of the energy sector. Energy, 205, 118025. [CrossRef]

- Pulido, L., Kohl, E., & Cotton, N. (2016). State Regulation and Environmental Justice: The Need for Strategy Reassessment. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 27(2), 12-31. [CrossRef]

- Ramasar, V., Busch, H., Brandstedt, E., & Rudus, K. (2022). When energy justice is contested: A systematic review of a decade of research on Sweden’s conflicted energy landscape. Energy Research & Social Science, 94, 102862. [CrossRef]

- Robison, R., Skjølsvold, T. M., Hargreaves, T., Renström, S., Wolsink, M., Judson, E., Pechancová, V., Demirbağ-Kaplan, M., March, H., Lehne, J., Wallenborn, G., & Wyckmans, A. (2023). Shifts in the smart research agenda? 100 priority questions to accelerate sustainable energy futures. Journal of Cleaner Production, 419. [CrossRef]

- Scott, L. C., & Upton, G. B. (2019). Louisiana Economic Outlook: 2020 and 2021.

- Shelton, R. E., & Eakin, H. (2022). Who’s fighting for justice?: advocacy in energy justice and just transition scholarship. Environmental Research Letters, 17(6), 063006. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L. M. da, Bitencourt, C. C., Faccin, K., & Iakovleva, T. (2019). The Role of Stakeholders in the Context of Responsible Innovation: A Meta-Synthesis. Sustainability, 11(6), 1766. [CrossRef]

- Simon-Friedt, B. R., Howard, J. L., Wilson, M. J., Gauthe, D., Bogen, D., Nguyen, D., Frahm, E., & Wickliffe, J. K. (2016). Louisiana residents’ self-reported lack of information following the Deepwater Horizon oil spill: Effects on seafood consumption and risk perception, Journal of Environmental Management, 180(15), 526-537. [CrossRef]

- Smith, C. (2023, May 9). Cox, Crescent Midstream, Repsol US Gulf CCS project gets DOE funding. Oli & Gas Journal. https://www.ogj.com/energy-transition/article/14293569/cox-crescent-midstream-repsol-us-gulf-ccs-project-gets-doe-funding.

- Snow, S., Chadwick, K., Horrocks, N., Chapman, A., & Glencross, M. (2022). Do solar households want demand response and shared electricity data? Exploring motivation, ability and opportunity in Australia. Energy Research and Social Science, 87. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B. K. (2017). Contestation, contingency, and justice in the Nordic low-carbon energy transition. Energy Policy, 102, 569–582. [CrossRef]

- Sovacool, B. K., & Blyth, P. L. (2015). Energy and environmental attitudes in the green state of Denmark: Implications for energy democracy, low carbon transitions, and energy literacy. Environmental Science and Policy, 54, 304–315. [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D., Kyriakopoulos, G. L., Lekavicius, V., & Siksnelyte-Butkiene, I. (2021). Energy Poverty and Low Carbon Just Energy Transition: Comparative Study in Lithuania and Greece. Social Indicators Research, 158(1), 319–371. [CrossRef]

- Svobodova, K., Owen, J. R., Harris, J., & Worden, S. (2020). Complexities and contradictions in the global energy transition: A re-evaluation of country-level factors and dependencies. Applied Energy, 265, 114778. [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, S., Benton-Connell, K., & Skinner, L. (2015). Power to the People. Toward Democratic Control of Electricity Generation. Trade Unions for Energy Democracy (TUED), Working Paper, 4, 571–610.

- Szulecki, K. (2018). Conceptualizing energy democracy. Environmental Politics, 27(1), 21–41. [CrossRef]

- Tarasova, E., & Rohracher, H. (2023). Marginalising household users in smart grids. Technology in Society, 72. [CrossRef]

- US Census Bureau. (2024). QuickFacts Baton Rouge city, Louisiana; Louisiana; United States. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/batonrougecitylouisiana,LA,US/PST045223.

- Vanegas Cantarero, M. M. (2020). Of renewable energy, energy democracy, and sustainable development: A roadmap to accelerate the energy transition in developing countries. Energy Research & Social Science, 70, 101716. [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio Calzadilla, P., & Mauger, R. (2018). The UN’s new sustainable development agenda and renewable energy: the challenge to reach SDG7 while achieving energy justice. Journal of Energy & Natural Resources Law, 36(2), 233–254. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Lo, K. (2023). Energy and Environmental Justice in China: Literature Review and Research Agenda. Journal of Asian Energy Studies, 7, 91–106. [CrossRef]

- Yeo, J., Knox, C. C. & Jung, K. (2018). Unveiling cultures in emergency response communication networks on social media: following the 2016 Louisiana floods. Quality & Quantity, 52, 519–535. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).