1. Introduction

Lately, the tobacco industry has been actively engaged in the development and promotion of novel products that could be viewed as potentially less harmful to health compared to traditional cigarettes [

1]. These alternative options to smoking are gaining exceptionally high popularity among adolescents.

Snus is a moist, smokeless oral tobacco product from Sweden, where it is widely used. Usually, it is placed behind the upper lip for a while, varying from a few minutes to even more than an hour, typically many times a day [

2,

3]. Nicotine is absorbed from the smokeless tobacco through the oral mucosa, and the harmful components dissolving in saliva will be absorbed from the intestinal walls, reaching circulation [

4]. Loose and portioned sachets are available forms of snus. The production and sale of snus is forbidden in almost all members of the European Union. Sweden is the single country that holds a special exception among the member countries of the European Union (EU) from the legislation; however, it is neither illegal, for instance, in non-European Union member Norway [

5]

Despite the prohibition, crowds consume snus; not only grown-ups but also adolescents highly prefer it. Besides the original Swedish snus, other similar products are created. There are entirely artificial substitute products that do not contain tobacco at all. Thus, their sale is legal – further on, this article considers the two types identical under the name "snus." Our study focuses on a highly exposed group of young ice hockey and football players. Snus use is presumably higher than the estimated European and Hungarian population, as they can contact Swedish or other snus user role model players.

Even though the harmful effects of cigarette smoking are generally known, the negative effects of snus, especially the oral effects, are rarely mentioned. Moreover, snus usage is sometimes even encouraged as a less harmful alternative to smoking despite the fact that it also has a carcinogenic effect and is associated with several health complications and numerous oral symptoms [

6,

7].

As the snus gets in contact with the oral mucosa for a longer time, usually in the exact same spot, the oral cavity is the most affected organ impaired by the side effects of snus. The utilization of the snus significantly elevates the likelihood of developing mucosal lesions [

8,

9]. It was also described that smokeless tobacco use is associated with oral potentially malignant lesions (e.g.: leukoplakia and erythroplakia) and different types of oral carcinomas [

10]. In addition, some other oral consequences could be gingival recession, plaque accumulation, and gingivitis, leading to periodontitis [

9,

11,

12]. Also, it was associated with a higher incidence of caries and abrasion, it causes discoloration of teeth, and regular consumers tend to have more tooth loss; however, results are still contradictory [

13,

14]. However, with primer prevention, the irreversible changes of the aforementioned oral diseases can be avoided.

Moreover, the available literature is very contradictory and deficient compared to smoking, and without long follow-up studies, we cannot consider it as a safe choice over smoking.

Hence, the aim of this study is to assess the oral consequences of snus (as a smokeless tobacco) use among young athletes who have significant exposure to snus. Our goal was to raise awareness and educate the participating adolescents, as all prevention methods are most beneficial in childhood.

2. Material And Methods

2.1. Participants

The sample of this study were Hungarian adolescent athletes, ice hockey and football players from Hungary, playing in the national team program of the respective federation and in a football academy in a major city. The adolescents were interviewed and their health status was screened in their summer preparation sports camps. The participants and their legal guardians gave consent to participate in the study. The recommendations of the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational studies in Epidemiology) guidelines were followed [

15]

2.2. Setting and Study Design

Our study was an observational study, which consisted of two individual parts.

The first part was an interactive prevention presentation by young dentists to gain the adolescents' trust. The presentation included the definition of snus, the prevailing legal frameworks, and a comprehensive display with pictures about the effect of snus on sports performance and oral health. The presentation also considered addiction and quitting, and interactive games were used to help the children memorize the information.

After the presentation, each participant underwent an individual dental screening, and young evaluators administered a thorough questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of 83 questions and gathered data on the socio-demographic status, oral hygiene habits, addictions (smoking habits, alcohol or drug consumption), factors to start using snus and current snus use habits of patients, and their awareness of the adverse effects of snus use. Disposable dental mirrors, probes, and forceps were provided for the dental screening, and each tooth was examined. The number of teeth, gum bleeding, fluorosis and erosion were recorded. The oral mucosa was also evaluated, and any soft tissue lesion was indicated. The participants were categorized into three groups based on their admitted snus use habits: regular users, occasional users, and never used snus. We categorized them into the aforementioned groups based on self-certificate answers. Those who admitted they had tried snus but denied being regular users, were considered the occasional users. Those who admitted regular use ever in their lifetime constructed the regular user group, while some adolescents stated they had never tried snus. The questionnaire contained questions to evaluate the snus use habits, which had to be completed only by the regular users. Based on their oral hygiene habits, the participants were categorized into two groups: those who brush their teeth at least twice a day and those who brush only once or less.

2.3. Statistics

We used the R version 4.1.0 summary package for the statistical evaluation [

16]. We compared the results of different groups based on the frequency of snus use and oral hygiene habits. We summarised categorical variables as frequencies and percentages and tested dependence using Pearson’s Chi-squared test[

17]. or Fisher's exact test for sparse data [

18]. Statistical significance was considered if the p-value < 0.05.

RESULTS

2.4. Demographics

248 (12-20 years) ice hockey players and footballers participated in our study. 206 male and 42 female Hungarian students attended, mostly living in a city or capital city (78%). In the self-certificate questionnaire, 20 (8.1%) of the participants considered themselves regular snus users, 36 (15%) admitted that they consume snus occasionally, and 192 (77%) stated that they have never tried snus. Only three responders admitted regular use of any other tobacco products, and three permitted occasional use of cannabis. (

Supplementary Table S1)

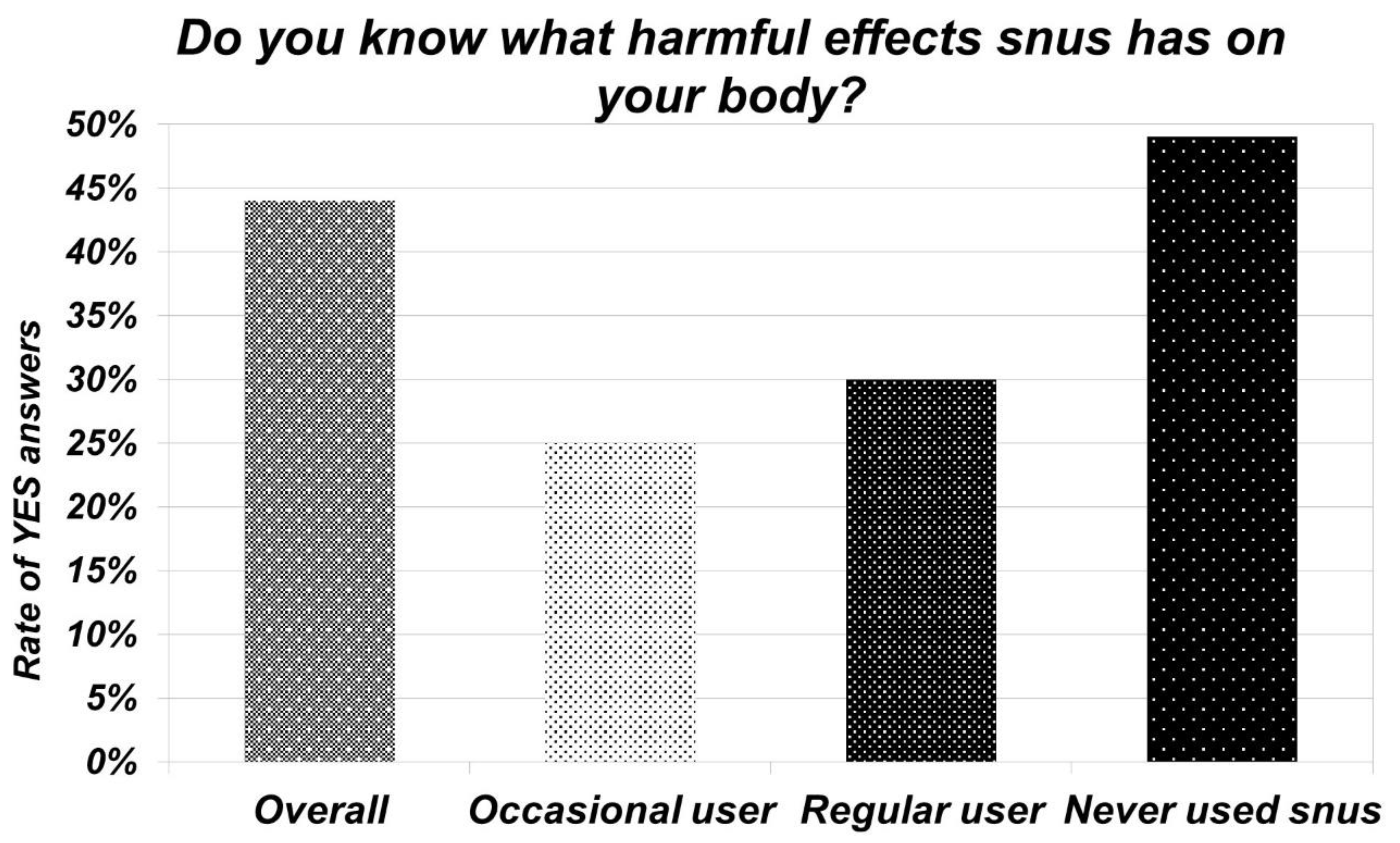

2.5. Knowledge about Snus

The questionnaire also aimed to test the adolescents’ knowledge about the negative effects of snus. The participants should answer this question in their own words. 19 (44%) could specify some of the negative effects. The most widely known was the carcinogenic effect. Besides the defined oral impacts (gum and enamel-damaging effect, oral hygiene deterioration, mucosal effect, tooth loss), systemic and addictive effects were also listed. Of those who have used snus, only 15 (27%) knew about its harmful effects. In contrast, half of the group who admitted they had never tried snus were aware of its negative effects.

2.6. Snus Habits

The vast majority of regular snus users became addicted between the ages of 14 and 16 and are regular users for 1 or 2 years. However, two claimed they are regular users since age 12, and 1 has been a snus user for six years. Furthermore, 9 (45%) use snus multiple times a day.

Portion snus was the preferred type among regular users. Most of the participants - 9 (45%) - keep, on average, the snus in their mouth for 10-30 minutes. However, the duration of use can vary from a few minutes to more than half an hour. 6 (30%) stated they usually keep multiple portions in their mouth at once. (

Supplementary Table S3)

2.7. Oral Hygiene and Dental Status of Participants

40 (15,8%) teenagers brush their teeth only once or less daily. Only 33 (14.2%) stated they use floss or interdental brush to clean the interdental areas. 121 (48.2%) use only electric or manual toothbrushes or both. Other participants use other tools, namely mouthwash or toothpick, besides the previously mentioned interdental brushes or floss. 91 (37%) patients reported that they experience gum bleeding regularly when brushing their teeth. Even so, only 5 (2%) patients know about some kind of gum disease.

By the dental examination, 118 participants were diagnosed with caries. Only 80 (32%) had healthy teeth. 62 patients recalled that they experienced toothache in the previous half year. The dental problems the responders experienced were a white coating on the tongue, sore gums, a bad taste, a sharp burning sensation, and a dry mouth. Some of the examined oral mucosal lesions were aphthous lesions, decubitus and signs of morsicatio, most occurring at the buccal vestibule.

Most responders (88%) do not use any mouthguards. Those who use them use thermoplastic ones, and only a few use mouthguards made by specialists. (

Supplementary Table S4)

2.8. Oral Effects of Snus

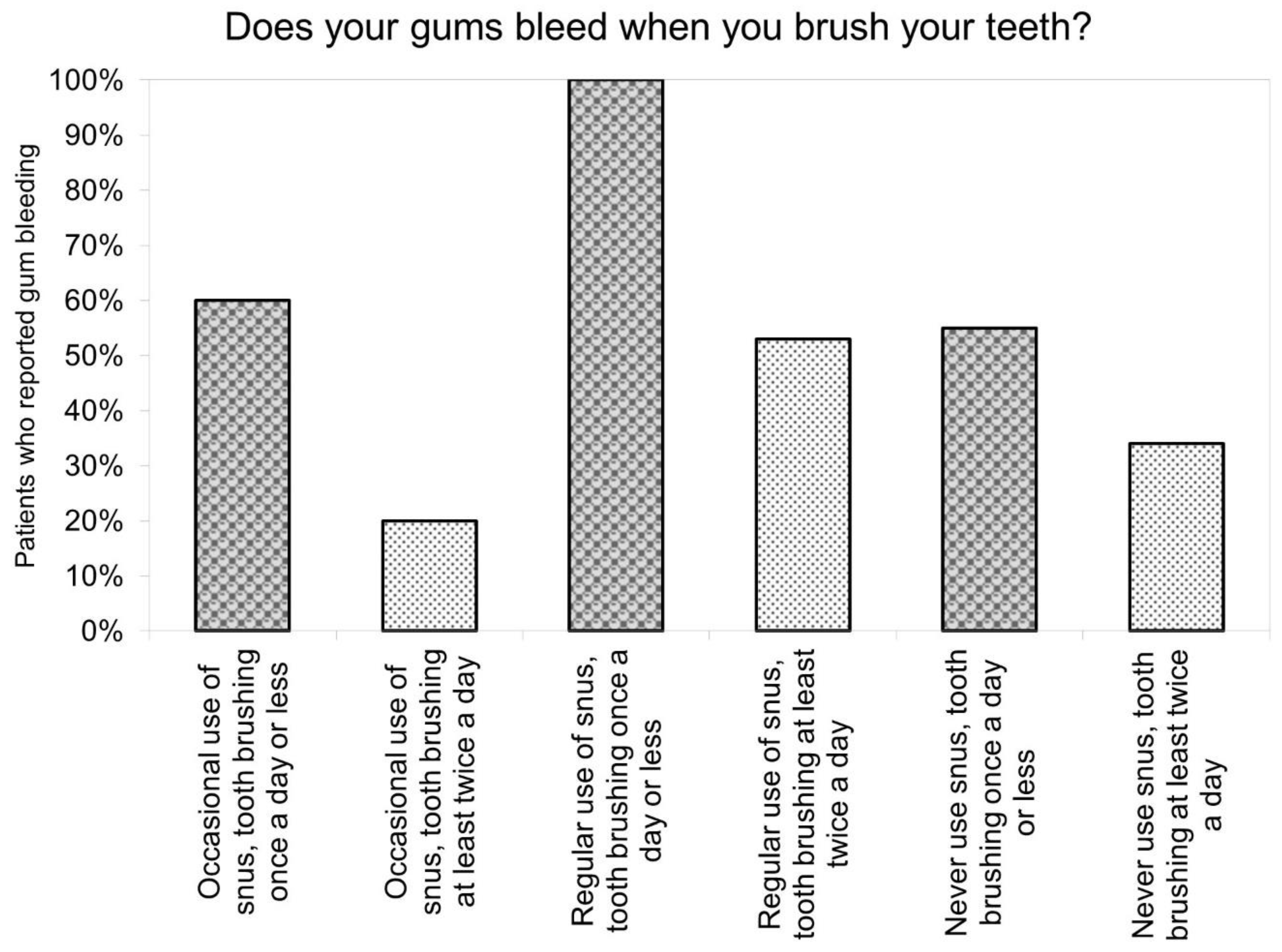

The participants were asked if they experienced gum bleeding. The highest amount of gum bleeding was measured in the regular snus user group (60%), while in the never-used group, it was 37%, and the difference is statistically significant (p=0.040). (

Table 1)

The combined effect of oral hygiene habits and snus usage was also evaluated.

100% of those who admitted regular snus usage and brushing their teeth only once or less reported they experienced gum bleeding. Of those regular snus users who wash their teeth more appropriately, only 53% recalled gum bleeding. This value is very similar to the value measured in the group who have never used snus, although have inappropriate oral hygiene. If we compare only adolescents with proper oral hygiene, those who are regular users in these groups experience gum bleeding the most compared to the other two groups. Those reported gum bleeding the least from all six groups, who have never used snus and brushed their teeth twice or more. (

Figure 2 and

Supplementary Table S5)

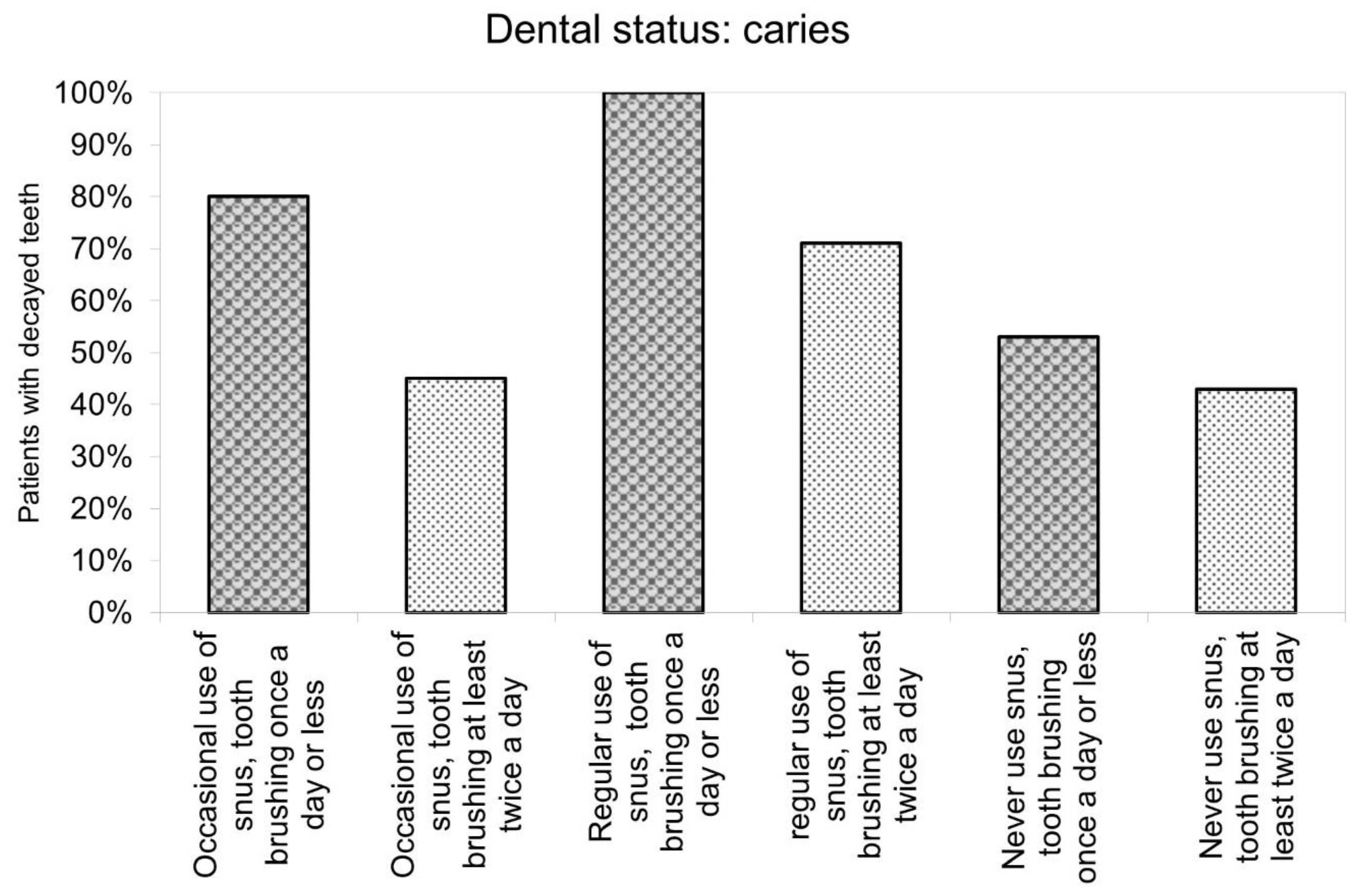

The sequence of the number of patients with untreated caries is similar to those mentioned above. 100% of regular snus users who have inappropriate oral hygiene had carious lesions. In those groups, where participants were either regular users or washed their teeth only once or less, more than half of the adolescents had teeth with caries. The lowest rate of carious teeth was measured in the group who had never used snus and brushed their teeth twice or more. (

Figure 3 and

Supplementary Tables S6 and S7)

Regular snus users were asked if they had experienced ulcerative lesions in their mouth, and 30% reported that they had. 5 reported that the location of the ulcerative lesion coincides with the site where the mucosa comes into contact with snus regularly, and 1 reported a lesion elsewhere. They could also supplement the questionnaire with their own words if they have experienced other symptoms associated with snus. 30% stated they have, and the specified symptoms were a sharp burning sensation in the mouth, a sore in the gum, a coated tongue, and a bad taste in the mouth.

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary of Main Findings

This study investigates the relationship between snus consumption and oral health, specifically focusing on gum bleeding and caries, within a cohort of adolescent athletes. Notably, our findings reveal a statistically significant difference in gum bleeding during toothbrushing among groups categorized by their snus consumption habits.

The cumulative effect of inadequate oral hygiene and regular snus use is implicated in increased gum bleeding. However, only trends could be identified due to the limited number of participants in separate snus user groups.

Oral Health Implications: While a worse cariological status is associated with snus usage, statistically insignificant results still indicate a clinically relevant difference. The prevalence of gum bleeding in our investigated population aligns with global adolescent groups, emphasizing the significance of preventive dental care in averting complications related to gingivitis and caries. Likewise, understanding the adverse impacts of snus is of paramount importance, as individuals who have never tried snus have a higher awareness of its negative effects than regular users. Raising awareness is a crucial part of effective prevention methods; therefore, adolescents should be educated about the effects of snus.

While the study identifies a statistically significant association between snus use and gum bleeding, that correlation does not imply causation. Several other factors could also affect our results, like oral hygiene practices, dietary habits, other modifying factors, and systemic diseases, to mention some examples. Also, due to the objective of the study, it is of an observational type.

Even though our study cannot be considered representative, these associations can be observed by a special highly exposed group.

3.2. Importance of Prevention in Periodontitis and Oral Cancer

Gum bleeding is the primary sign of endemic gingivitis, which affects billions of people, including adolescents worldwide [

19]. In our special investigated population, 37% of all participants experience gum bleeding, similar to other adolescent groups measured worldwide. The prevalence of gum bleeding measured in a Polish adolescent group was 37,4%[

20], while in another study carried out in China, 29.6 % had gingivitis [

21]. Gingivitis is characterized by the inflammation of the gum, which is caused by the accumulation of bacterial biofilm and plaque on the teeth due to inadequate oral hygiene [

22]. The main symptoms of gingivitis include gingival swelling, redness and bleeding [

23]. Even though gingivitis is an entirely reversible process, without remaining damage, once the dental biofilm is removed with thorough oral hygiene methods, which include professionally administered plaque control, mechanical plaque removal with adequate toothbrushing technique and use of interdental brushes regularly at home [

24,

25]

Although gingivitis is still reversible, chronic onset has been linked to the development of periodontitis. If left untreated for years, in susceptible hosts, gingivitis can progress into periodontitis, which is characterized by irreversible attachment loss [

26,

27,

28,

29]. It is the major cause of tooth loss in adults worldwide [

30]. As it is irreversible, the primary prevention of disease development is essential.

Oral mucosal changes could be examined in the participants' mouths; some also reported that they noticed them in their oral cavities. Oral mucosal changes, including ulcerous lesions, white plaque-like lesions and leukoplakia associated with snus use, raise concerns about possible links to oral cancer. Also, some reported that this was associated with the regular site of snus in the mouth. Recurring ulcerous lesions and leukoplakia, which are considered precancerous lesions, may lead to oral cancer [

31,

32]. Oral cancer may occur in different parts of the oral cavity, such as the surface of the tongue, palate, inside of the cheeks, gingiva or lips [

33].

Numerous studies have investigated the association between regular snus use and oral cancers; however, there is still an unmet need for more studies to establish a conclusive link between snus use and oral mucosal lesions and oral cancer. Yet there is no conclusion, as some studies could identify a possible risk for oral cancer in snus users, whereas some concluded different results [

34,

35,

36,

37]. This reflects the ongoing debate in the scientific community about the health effects of smokeless tobacco products. Nevertheless, more studies could establish a link between oral mucosal lesions and snus usage [

9,

38]. These mucosal changes are also preventable if the triggering cause (snus) is omitted [

38]. Though not all types of oral cancer can be eliminated by avoiding carcinogenic habits, the vast majority of them are preventable. The etiologic factors for squamous cell carcinoma, which accounts for approximately 90% of all oral malignancies, are tobacco intake (including both smoking and smokeless tobacco products) and alcohol consumption [

33]. Therefore, primary prevention, most wished before adulthood, is the key to avoiding oral cancers.

Most of the regular users in this sample have been users for 1 or 2 years; however, some participants have been users for 4 or 6 years. Miluna et al. confirmed in their study that there is a statistically significant correlation between how many years tobacco products were used and mucosal changes that could be seen in patients using tobacco products for 5-10 years [

39]. It would be essential to educate teenagers at in early age about the negative effects of snus, as the duration of regular usage is crucial in developing irreversible changes.

In summary, we can conclude that the battle against addictions – drugs, alcohol, and different types of tobacco products - can be the most successful with primary prevention methods in childhood. Therefore, most desirable, the manifestation of irreversible consequences can be avoided.

3.3. Efficacy Of education

Prevention is a complex mission; one of its keystones is raising awareness through education. Our main goal was to educate the adolescents with an entertaining presentation, maintain their attention, and pass on as much information as possible. Even though the questionnaire was administered after the presentation, 56% of the participants admitted they did not know any negative effects of snus use. Efforts to raise awareness among adolescents about snus-related health risks reveal gaps in knowledge, indicating a need for more effective educational strategies. It is often a huge challenge to preoccupy teenagers with a presentation, as they quickly get bored with lots of information. The potential incorporation of gamification in presentations is proposed to enhance engagement and information retention. It was shown that students tend to participate more in lectures, which are gamified, become more proactive, and find the material easier to learn than conventional courses. [

40]

Additionally, the promotion of snus is very harmful, as young people tend to believe advertisements and regular use of snus might become a gateway to cigarette addiction. Therefore, with the opposite effect, it will not be the planned "healthy alternative of cigarettes[

41,

42]

3.4. Special Population Characteristics

Our sample's unique composition adds value to our findings. The sample contains athletes, ice hockey players and footballers, who are more exposed to snus. Some camps take place in Sweden, and their role models could be Swedish ice hockey players, where snus usage is widespread and legal. Consequently, the prevalence of regular snus use is highly above the European estimated average (1.1%), even above the Swedish general population average (12.3%) [

43]. However, caution is advised in interpreting prevalence rates due to the potential underreporting influenced by legal restrictions as snus trade is illegal in European Union members, except Sweden [

5]. The tobacco-free nicotine pouches, as substitutes for snus products, are widely advertised and sold, or can be purchased online easily – their effect is considered identical in this article, but the legal environment is different for these products. Nevertheless, it should be mentioned that it can be suspected that also in our examined sample, in reality, even more teenagers use snus, than who admitted, due to the fear of punishment.

3.5. Strengths and Limitation

Regarding the strengths of our analysis, we highlight the population selection: the study focuses on a specific population—adolescent athletes—who are highly exposed to snus, providing a unique perspective on the impact of snus on oral health in this particular group. It is a cohort where diseases are still preventable due to the young ages of participants.

Reliability: The sample size of almost 250 adolescents adds credibility to the results, and the involvement of young resident doctors and dental students in administering the questionnaire enhances participant trust. Also, the presentation was interactive to involve the adolescents.

Clear presentation of findings: We could identify a statistically significant association between snus usage and gum bleeding. Moreover, we investigated the cumulative effect of inadequate oral hygiene and snus usage, which both worsen gum bleeding and caries index.

Considering the limitations of this work, a limited representation of regular snus users was observed, limiting the ability to draw firm conclusions about this subgroup. Therefore, only tendencies could be examined from the results of this subgroup. Furthermore, the snus use frequency groups were created based on their self-judgment. Presumably, there is an overlap between regular and occasional user groups. For instance, some adolescents consider themselves occasional sus users since they consume snus only at social gatherings. However, later on, they admitted they participate in several parties each week, therefore it could also be considered regular snus usage.

Challenges in differentiation and simplification of oral hygiene categories: It is very challenging to differentiate patients with adequate and inadequate oral hygiene due to various factors that can influence (e.g.: frequency of toothbrushing and the used instruments and techniques) making it complicated to categorize based on oral hygiene habits. Therefore, the categorization of participants was based solely on toothbrushing frequency, which simplified the assessment of oral hygiene habits, potentially overlooking other relevant factors.

4. Conclusion

To summarize, snus use has a detrimental impact on oral health and is statistically significantly associated with gum bleeding. When inadequate oral hygiene practices are combined with snus use, it further exacerbates the adverse effects on oral health, particularly affecting the gums. Moreover, it's essential to recognize that oral health is closely linked to overall health and well-being. Consequently, achieving a comprehensive state of systemic health becomes challenging without proper oral health. Increasing awareness at an early age plays a vital role in reducing snus usage, and education serves as a primary means of prevention.

5. Bullet Points

Snus use negatively affects oral health and is statistically significantly associated with gum bleeding.

Insufficient oral hygiene and snus use cumulatively affects oral health, especially the gums.

Awareness contributes to reducing snus usage; therefore, early, childhood education has the leading role in prevention.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Orsolya Németh: conceptualization, project administration, formal analysis, writing – original draft; Levente Sipos: conceptualization, visualization, writing - review & editing; Péter Mátrai: conceptualization, formal analysis, data curation, writing – review & editing; Noémi Szathmári-Mészáros: conceptualization, data curation, writing - review & editing; Dóra Iványi: conceptualization, writing – review & editing; Abdallah Benhamida: methodology, formal analysis, software, writing – review & editing Fanni Simon: conceptualization, writing – review & editing; Eitan Mijiritsky: conceptualization; supervision; methodology; writing – original draft. All authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript.

Funding

No funding to declare.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The identification number of the ethical approval of this study is TUKEB IV/1433-1/2020/EKU.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study can be found in the figures, tables and supplementary materials. The whole questionnaire used in our research is also available in the

Supplementary Materials.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Conflicts of Interest

None to declare.

References

- Hatsukami, D.K.; Carroll, D.M. Tobacco harm reduction: Past history, current controversies and a proposed approach for the future. Prev Med 2020, 140, 106099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Digard, H.; Errington, G.; Richter, A.; McAdam, K. Patterns and behaviors of snus consumption in Sweden. Nicotine & Tobacco Research 2009, 11, 1175–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, P.N. Epidemiological evidence relating snus to health--an updated review based on recent publications. Harm Reduct J 2013, 10, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickworth, W.B.; Rosenberry, Z.R.; Gold, W.; Koszowski, B. Nicotine Absorption from Smokeless Tobacco Modified to Adjust pH. J Addict Res Ther 2014, 5, 1000184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The European Parliament and the Council of the European Union.Directive 2014/40/EU of the European Parliament and the Council of April 2014 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products and repealing Directive 2001/37/EC. Availabe online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32014L0040&from=EN (accessed on 27.08.).

- Clarke, E.; Thompson, K.; Weaver, S.; Thompson, J.; O'Connell, G. Snus: a compelling harm reduction alternative to cigarettes. Harm Reduct J 2019, 16, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foulds, J.; Ramstrom, L.; Burke, M.; Fagerström, K. Effect of smokeless tobacco (snus) on smoking and public health in Sweden. Tob Control 2003, 12, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallischnigg, G.; Weitkunat, R.; Lee, P.N. Systematic review of the relation between smokeless tobacco and non-neoplastic oral diseases in Europe and the United States. BMC Oral Health 2008, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopperud, S.E.; Ansteinsson, V.; Mdala, I.; Becher, R.; Valen, H. Oral lesions associated with daily use of snus, a moist smokeless tobacco product. A cross-sectional study among Norwegian adolescents. Acta Odontologica Scandinavica 2023, 81, 473–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthukrishnan, A.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral health consequences of smokeless tobacco use. Indian J Med Res 2018, 148, 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Chotai, M.; Mehmood, A.; Almas, K. Oral mucosal disorders associated with habitual gutka usage: a review. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010, 109, 857–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weintraub, J.A.; Burt, B.A. Periodontal effects and dental caries associated with smokeless tobacco use. Public Health Rep 1987, 102, 30–35. [Google Scholar]

- Hugoson, A.; Rolandsson, M. Periodontal disease in relation to smoking and the use of Swedish snus: epidemiological studies covering 20 years (1983-2003). J Clin Periodontol 2011, 38, 809–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Dietrich, T.; Bornstein, M.M.; Casals Peidró, E.; Preshaw, P.M.; Walter, C.; Wennström, J.L.; Bergström, J. Oral health risks of tobacco use and effects of cessation. Int Dent J 2010, 60, 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- RCoreTeam. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Availabe online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on.

- Pearson, K. X. On the criterion that a given system of deviations from the probable in the case of a correlated system of variables is such that it can be reasonably supposed to have arisen from random sampling. The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science 1900, 50, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.A. On the Interpretation of χ<sup>2</sup> from Contingency Tables, and the Calculation of P. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 1922, 85, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mühlemann, H.R.; Son, S. Gingival sulcus bleeding--a leading symptom in initial gingivitis. Helv Odontol Acta 1971, 15, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olczak-Kowalczyk, D.; Gozdowski, D.; Kaczmarek, U. Oral Health in Polish Fifteen-year-old Adolescents. Oral Health Prev Dent 2019, 17, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, W.; Liu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Li, J.; Huang, S. Epidemiology and associated factors of gingivitis in adolescents in Guangdong Province, Southern China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loe, H.; Theilade, E.; Jensen, S.B. EXPERIMENTAL GINGIVITIS IN MAN. J Periodontol (1930) 1965, 36, 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trombelli, L.; Farina, R.; Silva, C.O.; Tatakis, D.N. Plaque-induced gingivitis: Case definition and diagnostic considerations. J Periodontol 2018, 89 (Suppl. 1), S46–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murakami, S.; Mealey, B.L.; Mariotti, A.; Chapple, I.L.C. Dental plaque-induced gingival conditions. J Periodontol 2018, 89 (Suppl. 1), S17–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapple, I.L.; Van der Weijden, F.; Doerfer, C.; Herrera, D.; Shapira, L.; Polak, D.; Madianos, P.; Louropoulou, A.; Machtei, E.; Donos, N.; et al. Primary prevention of periodontitis: managing gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol 2015, 42 Suppl 16, S71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löe, H.; Anerud, A.; Boysen, H.; Morrison, E. Natural history of periodontal disease in man. Rapid, moderate and no loss of attachment in Sri Lankan laborers 14 to 46 years of age. J Clin Periodontol 1986, 13, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, R.C.; Kornman, K.S. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: an introduction. Periodontol 2000 1997, 14, 9–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schätzle, M.; Löe, H.; Bürgin, W.; Anerud, A.; Boysen, H.; Lang, N.P. Clinical course of chronic periodontitis. I. Role of gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol 2003, 30, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, N.P.; Schätzle, M.A.; Löe, H. Gingivitis as a risk factor in periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol 2009, 36 Suppl 10, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Availabe online: https://www.nidcr.nih.gov/research/data-statistics/periodontal-disease (accessed on 24.09.).

- Warnakulasuriya, S.; Johnson, N.W.; van der Waal, I. Nomenclature and classification of potentially malignant disorders of the oral mucosa. J Oral Pathol Med 2007, 36, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilligan, G.; Piemonte, E.; Lazos, J.; Simancas, M.C.; Panico, R.; Warnakulasuriya, S. Oral squamous cell carcinoma arising from chronic traumatic ulcers. Clin Oral Investig 2023, 27, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, P.H.; Patel, S.G. Cancer of the oral cavity. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2015, 24, 491–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johansson, S.L.; Hirsch, J.M.; Larsson, P.A.; Saidi, J.; Osterdahl, B.G. Snuff-induced carcinogenesis: effect of snuff in rats initiated with 4-nitroquinoline N-oxide. Cancer Res 1989, 49, 3063–3069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roosaar, A.; Johansson, A.L.; Sandborgh-Englund, G.; Axéll, T.; Nyrén, O. Cancer and mortality among users and nonusers of snus. Int J Cancer 2008, 123, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenquist, K.; Wennerberg, J.; Schildt, E.B.; Bladström, A.; Hansson, B.G.; Andersson, G. Use of Swedish moist snuff, smoking and alcohol consumption in the aetiology of oral and oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. A population-based case-control study in southern Sweden. Acta Otolaryngol 2005, 125, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boffetta, P.; Aagnes, B.; Weiderpass, E.; Andersen, A. Smokeless tobacco use and risk of cancer of the pancreas and other organs. Int J Cancer 2005, 114, 992–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallischnigg, G.; Weitkunat, R.; Lee, P.N. Systematic review of the relation between smokeless tobacco and non-neoplastic oral diseases in Europe and the United States. BMC Oral Health 2008, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miluna, S.; Melderis, R.; Briuka, L.; Skadins, I.; Broks, R.; Kroica, J.; Rostoka, D. The Correlation of Swedish Snus, Nicotine Pouches and Other Tobacco Products with Oral Mucosal Health and Salivary Biomarkers. Dentistry Journal 2022, 10, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barata, G.; Gama, S.; Jorge, J.; Goncalves, D. Engaging Engineering Students with Gamification. In Proceedings of 2013 5th International Conference on Games and Virtual Worlds for Serious Applications (VS-GAMES), 11-13 Sept. 2013; pp. 1–8.

- Guggenheimer, J. Implications of smokeless tobacco use in athletes. Dent Clin North Am 1991, 35, 797–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daniel Roth, H.; Roth, A.B.; Liu, X. Health Risks of Smoking Compared to Swedish Snus. Inhalation Toxicology 2005, 17, 741–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, M.E.; Lugo, A.; Boffetta, P.; Gilmore, A.; Ross, H.; Schüz, J.; La Vecchia, C.; Gallus, S. Smokeless tobacco use in Sweden and other 17 European countries. Eur J Public Health 2016, 26, 817–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).