1. Introduction

To effectively reduce morbidity and mortality due to cervical cancer, early diagnosis and treatment of grade 3 Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN3) of the uterine cervix is necessary.

CIN3/HSIL represents the true preneoplastic lesion of cervical carcinoma, it is a lesion typical of young women who are often still nulliparous and eager to have children, so using a therapeutic technique that preserves the functionality of the cervix is of fundamental importance. Excision is the treatment indicated by the American Society Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology (ASCCP): surgical excision (cold blade conization) or LEEP (Large loop excision procedure).[

1] There is an important difference between the two techniques, surgical conization removes a greater quantity of tissue from the uterine cervix, putting a future pregnancy at risk, so today it is preferred to use LEEP. The problem with LEEP is given by the fact that there is a high percentage of positive margin and persistence of the viral lesion, which the literature has identified as risk factors for residual disease. [

2,

3,

4] Previous studies have shown that menopausal status also represents a risk factor for residual or occult disease. Cervical atrophy secondary to the lack of estrogen induces the ascent of the entire transformation zone (Type 3 Transformation Zone), making both cytology and colposcopy ineffective [

5,

6]. The cervixes of these women are often small and with an unexplorable cervical canal, so it can also be difficult to perform a LEEP, the cone of which should be longer (15-20mm) than in young women (7-10mm). [

7] This specific group of post-menopausal patients needs more attention during treatment. Although European guidelines and the ASSCP deem the use of hysterectomy in the treatment of CIN3 unacceptable, many clinicians are more inclined to propose hysterectomy to postmenopausal women diagnosed with CIN3, considering it as a definitive intervention. The literature has demonstrated that the therapeutic efficacy of LEEP is almost identical to hysterectomy, with less morbidity. [

8] The risk of occult cervical cancer in hysterectomy specimens may explain the reason why some gynecologists, especially for post-menopausal women or those who do not desire further reproduction, resort to hysterectomy for the treatment of CIN3. Furthermore, the literature considers hysterectomy for CIN3 as a known risk factor for the subsequent development of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN). [

9,

10]. High-grade VaIN is a preneoplastic lesion of the vagina, a precursor of squamous cell carcinoma, HPV-related and whose incidence has been reported to be 100 times lower than that of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). [

11] According to the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology and the College of American Pathologists, vaginal dysplasia can be classified as low-grade vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN) and high-grade VaIN [

12]. Studies have revealed that the prevalence of HPV is equal in hysterectomized and non-hysterectomized women. [

13] VaIN often exists in conjunction with vulvar and cervical intraepithelial lesions [

14]. It is hypothesized that the hysterectomy procedure may be a cause of increased incidence of VaIN in the hysterectomized woman. There are few studies addressing this issue and they show conflicting results. [

9,

15]

This study aimed to study the incidence of high-grade VaIN in the population of women undergoing hysterectomy for CIN3 or for benign uterine pathology, to illustrate the therapeutic options and follow-up

2. Materials and Methods

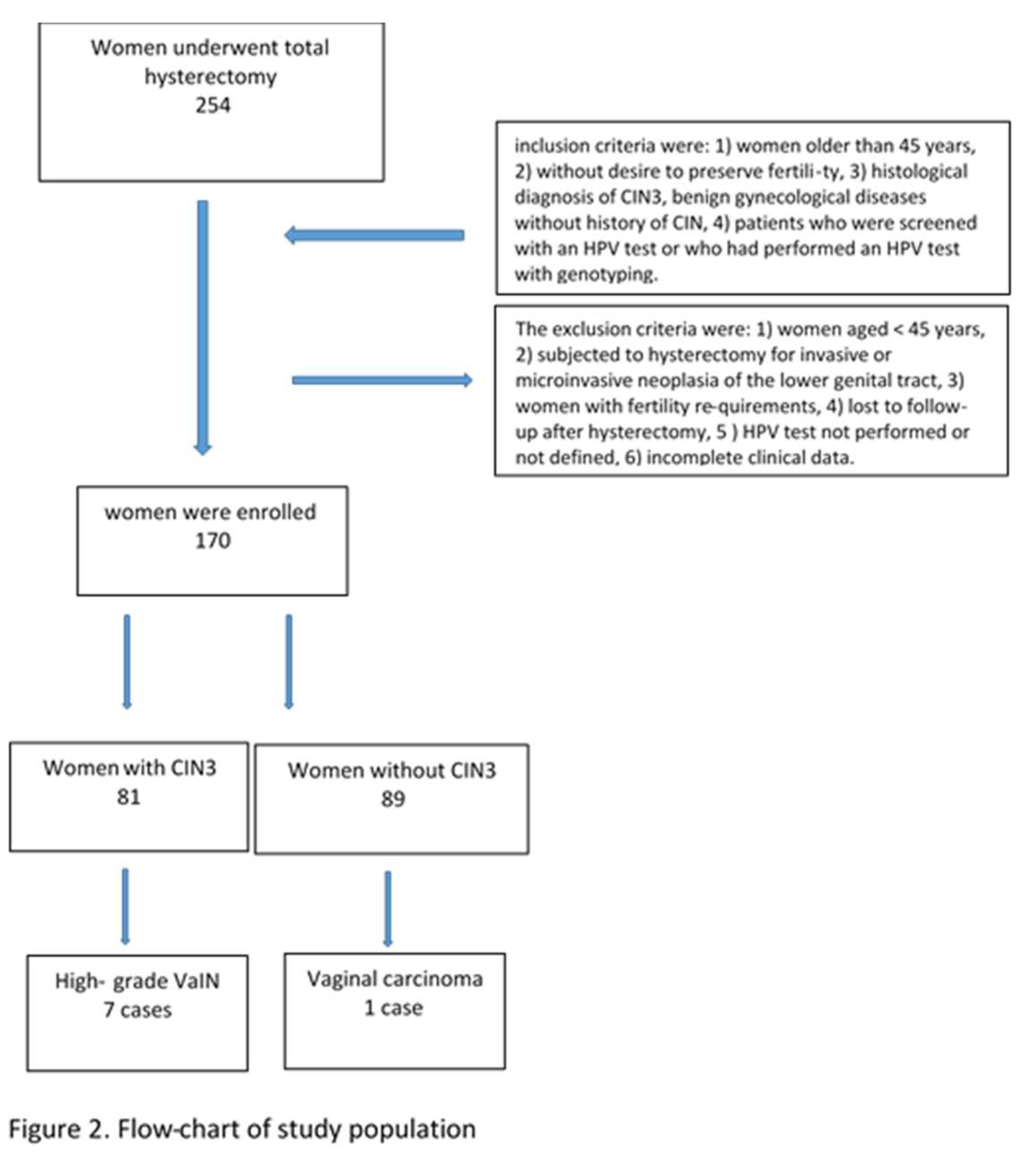

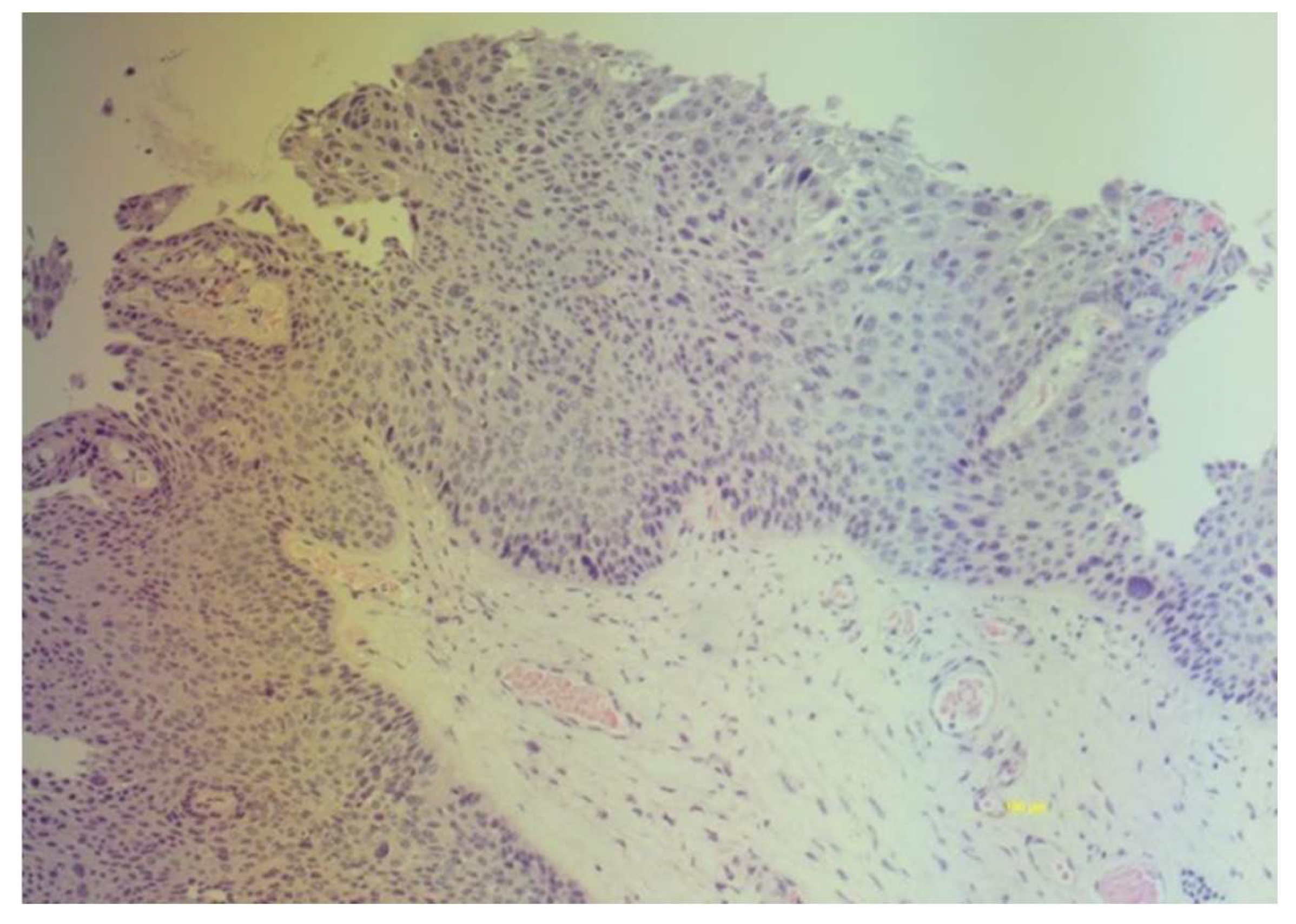

This retrospective study included patients who underwent total hysterectomy from January 2019 to December 2022 at two second-level centers for the diagnosis and treatment of HPV lesions and cervical cancer: Gynecology and Obstetrics Unit, Rodolico University Hospital, Department of General Surgery and Medical- Surgical Specialties of the University of Catania; Gynecological Oncology Unit, Humanitas Hospital, Catania, Italy. The medical records of 254 women screened for cervical cancer with primary HPV testing, unvaccinated and undergoing laparoscopic hysterectomy were studied. The women in the cohort were grouped as follows: women hysterectomized for CIN3 and women hysterectomized for benign gynecological pathology (uterine fibroma, adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia). The inclusion criteria were: 1) women older than 45 years, 2) without desire to preserve fertility, 3) histological diagnosis of CIN3, benign gynecological diseases without history of CIN (e.g. uterine fibroid, endometriosis), 4) patients who were screened with an HPV test or who had performed an HPV test with genotyping. The exclusion criteria were: 1) women aged < 45 years, 2) subjected to hysterectomy for invasive or microinvasive neoplasia of the lower genital tract, 3) women with fertility requirements, 4) lost to follow-up after hysterectomy, 5 ) HPV test not performed or not defined, 6) incomplete clinical data. The histological diagnosis of high-grade VaIN was defined as the presence of moderate or severe vaginal intraepithelial dysplasia originating in the native squamous epithelium of the vagina, without invasion. (

Figure 1)

All women underwent laparoscopic hysterectomy. The follow-up strategy included performing a cotest and colposcopy with biopsy if necessary. The first follow-up was performed six months after hysterectomy. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating patients regarding the use of the data for scientific purposes.

The University Hospital’s ethics committee waived the requirement for ethical approval and informed consent because this study used previously archived data, according to current legislation (20 March 2008), AIFA. According to Italian law, patient consent was not mandatory in a retrospective study [

16]

2.1. HPV Test and Genotyping

After cytological sampling for HPV DNA, samples were sent to the laboratory for DNA extraction and viral DNA genotyping via genetic amplification, followed by hybridization with genotype-specific probes capable of identifying most of the HPV genotypes of the genital region—13 high-risk HPV genotypes (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 53, 56, 58, 59), 11 low-risk genotypes (6, 11, 40, 43, 44, 54, 70, 66, 68, 73, 82), and 3 undefined-risk genotypes (69, 71, 74). The commercial method used was the MAG NucliSenseasy system (bioMérieux SA, Marct l’Etoile, France). The technique used was described previously [

17].

3. Results

Of the 254 patients, only 170 met our requirements: the study sample consisted of a group of 81 women hysterectomized for CIN3 and 89 hysterectomized for benign gynecological pathology (uterine fibroma, adenomyosis, endometrial hyperplasia).

Figure 2 shows the flow-chart of study population

High-grade VaIN was found in 8 patients after hysterectomy (4.7%). The incidence rates of VaIN in patients with and without a history of CIN were significantly different (8.6%, 7/81, vs 1.2%, 1/89); OR=8.32(CI95% 1.00-69.21) p= 0.03. (

Table 1)

.

The rates of hr-HPV infection after hysterectomy of patients with and without a history of CIN were 12.4% (10/81) and 7.8% (7/89), respectively. (

Table 2)

The incidence of VaIN in patients with persistent hr-HPV infection and in those with and without a history of CIN was 70% (7/10) and 14.2% (1/7), respectively, P =0.001

In particular, seven cases of high-grade VaIN of the vaginal vault were diagnosed in women hysterectomized for CIN3 and one invasive vaginal carcinoma in women hysterectomized for benign pathology.

Hysterectomized women with CIN3 showed an 8 times greater risk than hysterectomized women with benign pathology of developing high-risk VaIN, OR=8.32(CI 95% 1.00-69.21) p=0.03. The risk of VaIN is low in women hysterectomized for benign pathology, OR=0.12(CI 95% 0.01-1.00 p=0.02. The risk of developing VaIN is greater in women with viral persistence, OR =14.00 (CI 95% 1.14-172.65) p=0.02.

The median time between primary treatment and diagnosis of high-grade VaIN was 18 (range: 6-45) months. All cases of high-grade VaIN occurred in women with persistent HPV infection. The most frequent genotype was 16 followed by HPV31. Women with high-grade VaIN were positive for genotype 16, in one case there was HPV16,52.

In the group of women who underwent hysterectomy for benign uterine pathology and without a history of CIN, the average age was 54 years (range 45-62), they had participated in the screening for cervical cancer with primary HPV and 11 women were HPV positive. After hysterectomy only 7 women were still HPV positive and one of them developed squamous cell carcinoma of the vagina. In the latter case the genotyping highlighted genotype 16. Unfortunately we did not have the cytology results of all the HPV positive women nor can we talk about genotyping in this group because the screening uses partial genotyping.

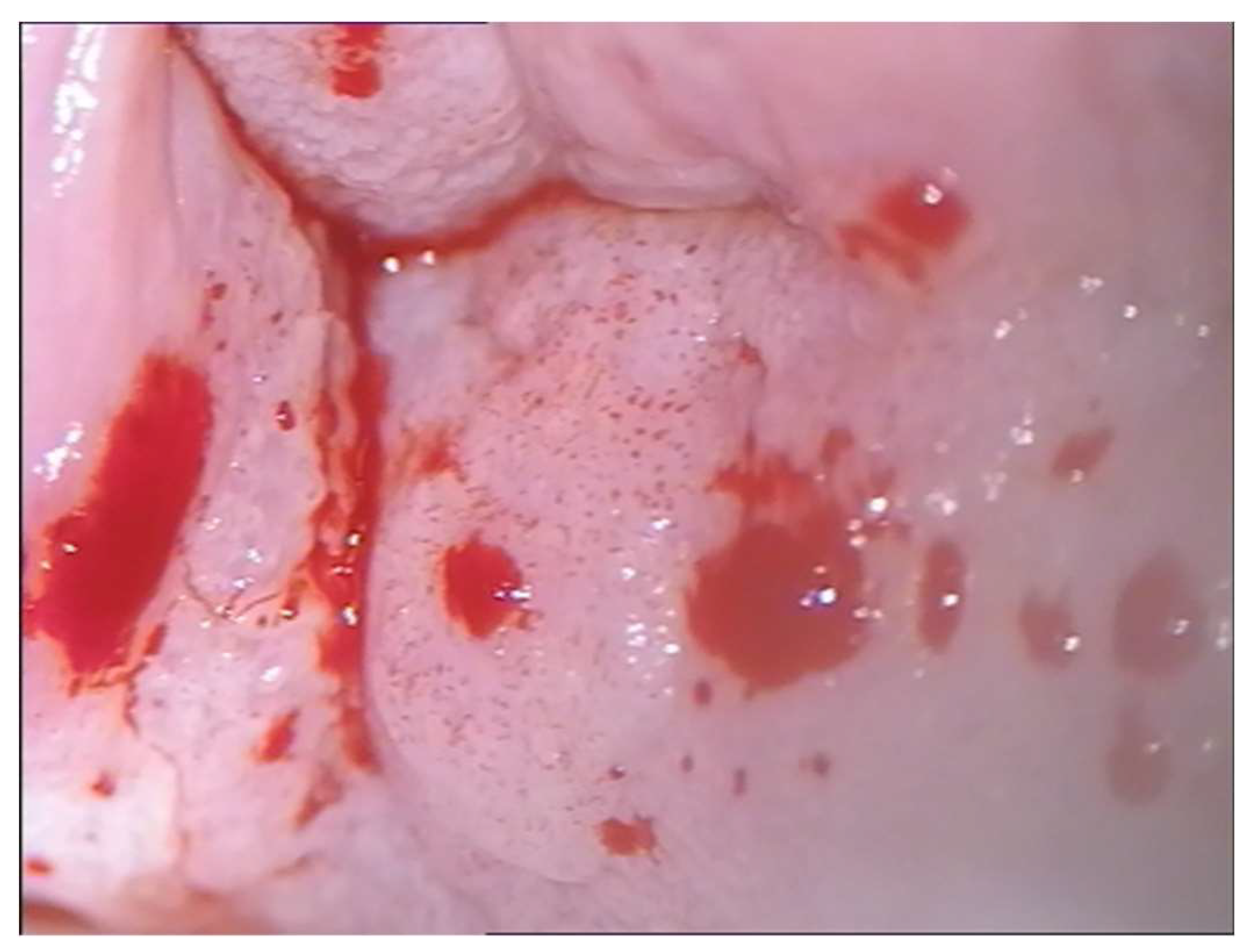

Positive cytology for ASCUS in cases of high-grade VaIN and frankly neoplastic in the case of vaginal carcinoma led us to subject women to colposcopy. The colposcopic examination highlighted areas of thickened acid-positive epithelium with irregular punctate appearances in correspondence of the vaginal dome towards the posterior wall in two cases, confirmed histologically. (

Figure 3) In three cases the colposcopic examination highlighted thickened acid-positive epithelium multifocal. Two cases of high-grade VaIN always affected the vaginal dome but were not very extensive and had the colposcopic appearance of leukoplakia. The responsible genotypes were HPV 16 in all cases, in one case genotype 52 was associated..

Given that the lesions were high grade and close to the closure of the vagina, it was preferred to resort to excision of the lesion with an upper vaginectomy, to a complete diagnosis and exclude the presence of occult carcinoma. The colposcopic appearance of the vaginal carcinoma, 25 months after hysterectomy, occupied the posterior vaginal wall towards the vaginal dome, with a multipapillary appearance, easily bleeding to the touch. (

Figure 4) The histological examination confirmed the diagnosis and the genotyping highlighted the presence of HPV 16. The woman underwent radiotherapy.

Table 4 shows the personalized treatment according to age, histological grade and location of the lesion

4. Discussion

The results of the present study highlight a higher rate of high-grade VaIN in HPV-positive women with a previous history of high-grade intraepithelial lesion compared to HPV-positive women without previous neoplasia or CIN, namely 8.6% of High-grade VaIN in women hysterectomized for CIN3 and 1.2% high-grade VaIN in women undergoing hysterectomy for benign uterine pathology. This is consistent with previous studies showing that women with a history of high-grade CIN have an increased risk of subsequent high-grade anogenital intraepithelial neoplasia or cancer, and the risk is higher for vaginal cancer than for anal and vulvar cancers. [

9,

18,

19,

20]. The anatomical proximity of the vagina to the cervix makes HPV coinfection of the cervix and vagina more likely than coinfection of the cervix and vulva or the cervix and anus. [

22,

23,

24]

The study highlights a significant correlation between the incidence of high-grade VaIN and persistent HPV infection. (p<0.02). OR =14.00 (CI 95% 1.14-172.65) p=0.02. All VaINs were HPV 16 positive. These data are confirmed by the study by Bryan et al. who detected HPV infection in 96% of patients diagnosed with VaIN [

25]. Furthermore, a previous study revealed that the severity of VaIN was closely related to HPV16 [

26]. Therefore, HPV16 genotyping could be a useful tool for risk stratification of VAIN patients.

Another important result that the present study highlighted is the concordance of genotypes between high-grade VaIN and concomitant CIN3, this data was also confirmed by other authors. [

27] All these elements suggest that it is the history of HPV-related disease of the lower genital tract and viral persistence, rather than the hysterectomy itself, that should be considered as a risk factor for the development of high-grade VaIN. Persistent HPV infection after hysterectomy can develop vaginal, vulvar, and anal dysplasia which have similar risk factors.

The correlation between CIN3, high-grade VaIN and vulvar HSIL can be explained by the HPV-induced “field effect” theory [

28]. It all begins at the level of the cervix where the presence of a squamous-columnar junction area facilitates the oncogenic action of high-risk HPV genotypes where a single colony of monoclonal cells has been infected and transformed, giving rise to cervical CIN. Subsequently, pre-existing monoclonal cells spread the dysplastic cells throughout the epithelium of the genital mucosa, involving the different sites (cervix, vagina, vulva and anus), giving rise to a multifocal disease. These lesions can occur simultaneously (synchronous lesions) or even several years after the initial cervical lesion (metachronous lesions). Cervical dysplasia usually arises years earlier than vaginal or vulvar dysplasia.

The main element that emerges is that vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia is often secondary to invasive cervical or intraepithelial neoplasia. Primary vaginal carcinoma is a rare event. The neoplasm develops in the vaginal epithelium only in exceptional circumstances because the vagina, not having a squamous-columnar junction, is less susceptible to carcinogenesis than the cervix. For this reason, it is unusual for the vaginal epithelium to undergo neoplastic transformation without the coexistence of a cervical neoplasm.

The present study shows that there is also a small risk of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia or vaginal carcinoma for women after hysterectomy for benign uterine pathology, but always in HPV positive women. One possible reason may be that persistent HPV infection may progress undetected to vaginal cancer, as there is no follow-up program for these women.

This suggests that vaginal cytology follow-up may be warranted for all post-hysterectomy patients, but there is no consensus in the literature.

Approximately 10% of women who undergo hysterectomy for cervical dysplasia develop vaginal dysplasia or cancer after surgery, and women who undergo LEEP for CIN3 may have recurrence of CIN2+; whereas,, the onset of VaIN after hysterectomy in patients without a history of CIN is extremely rare. [

29,

30] In light of this, the American Society of Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology recommends that follow-up of the vagina after hysterectomy be performed only if the surgery was performed for CIN3. Our results essentially support this strategy.

After treatment of high-grade VaIN, follow-up consists of vaginal Pap testing and HPV testing every six months for at least two years and then annually for at least five to ten years. Furthermore, clinical follow-up could potentially be considered in specific high-risk populations, such as women with HPV persistence or immunosuppressed populations, such as organ transplant recipients and HIV-positive women.

Treatment of high-grade VaIN is a very delicate topic due to the thinness of the vaginal wall, with its close proximity (5 to 7 mm) to the urethra, bladder, Douglas and rectum, the standard surgical procedures and radiotherapy risk morbidity. There is no consensus on the optimal treatment modality for women with high-grade VaIN. Current treatment methods for VaIN include surgical excision, ablative therapy, and topical treatment. Surgical excision is the primary therapeutic approach, particularly when infiltration cannot be excluded. [

31,

32] However, regardless of the treatment modality, patients with high-grade VaIN are at high risk of recurrence and are at risk of developing invasive disease [

33,

34]. Upper vaginectomy is considered the treatment of choice for high-grade VaIN or apical VaIN in the vaginal cuff scar region in women hysterectomized for cervical cancer [

35]. It also lends itself to a better evaluation of the margins and to exclude invasion.

The use of CO2 laser vaporization has been reported for lesions at sites other than the apex, as well as for the need for continued sexual function in sexually active young women. However, some studies have suggested that the use of laser ablation for the treatment of vaginal HSIL is not very effective, especially for post-hysterectomy vaginal cuff, because of the possibility of latent invasive cancer [

36]. Latent cancers have been reported in 6.8 %–18.6 % of vaginal HSIL patients [

37,

38] In case of multifocal conditions or lesions involving the lower third of the vagina, upper vaginectomy can be combined with laser vaporization [

39]. Although upper vaginectomy and total vaginectomy can be considered effective treatments, they do not prevent recurrences.

VaIN should be preventable or diagnosed at an early stage. A colposcopy of the upper vagina for a coexisting vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia would be indicated, prior to hysterectomy for CIN. Furthermore, attention should be paid to the time of closure of the vagina during hysterectomy since it is possible that some vaginal tumors may originate from occult foci of neoplastic epithelium buried in the vaginal cuff, and to avoid "trapping" the neoplastic epithelium in the scar.

Some authors suggest to detect VaIN or early invasive vaginal cancer, performing transvaginal suturing of the stump, allowing a thorough examination of the vaginal epithelium by colposcopy. When suturing the vagina laparoscopically and abdominally, it is important not to suture both ends of the vaginal apex to the stump of the cardinal ligament, as this can lead to the formation of vaginal crypts, which cause difficulties in subsequent colposcopy and biopsy.[

40]

Precisely women with persistent HPV infection after hysterectomy for CIN2+ who are at high risk of developing vaginal, vulvar and anal dysplasia represent the optimal target for the indication of postoperative HPV vaccination. Results observed among patients undergoing treatments for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia highlighted that vaccination could reduce the risk of recurrence. Although these data need to be validated in patients with vaginal dysplasia, we might expect similar results

The limitations of the present study are represented by its retrospective nature, which does not allow a complete data analysis and the small sample under study, forced by the rarity of the pathology. Another important limitation was the limited follow-up of the study population. Only 8,6% of women appeared to have high-grade VaIN, while less than 1,2% of cases revealed vaginal cancer, but the short follow-up -up does not allow definitive conclusions to be drawn.

5. Conclusions

Importantly, approximately 1% to 7% of patients undergoing hysterectomy for CIN or cervical cancer may develop VaIN, typically within a 2-year period. [

41,

42]

A vaginal wall biopsy under colposcopy is recommended to be routinely performed before surgery for patients undergoing hysterectomy for CIN3 or stage IA cervical cancer, which helps determine the necessary extent of vaginal resection during the procedure. After hysterectomy, patients with a history of CIN should undergo annual screening with vaginal dome cytology and HPV testing.

In conclusion, our study provides further support for the central role of hrHPV, particularly HPV16, in the development of high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia and vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer.[

43]

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Maria Teresa Bruno; Data curation, Francesco Sgalambro and Miriam Previti; Formal analysis, Marco Marzio Panella, Gaetano Valenti, Salvatore Di Grazia and Jessica Farina; Investigation, Gaetano Valenti; Software, Marco Marzio Panella, Salvatore Di Grazia, Francesco Sgalambro and Jessica Farina; Supervision, Maria Teresa Bruno and Liliana Mereu; Validation, Liliana Mereu; Writing – original draft, Maria Teresa Bruno; Writing – review & editing, Maria Teresa Bruno.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Based on Italian law, University Hospital’s ethics committee (Catania 2) waived the requirement of ethical approval and informed consent because the study used previously archived data, according to current legislation (20 March 2008) (AIFA).

https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2008/03/31/08A02109 (accessed on 10 April 2024). .

Informed Consent Statement

Based on Italian law, patient consent was not mandatory in a retrospective study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the Scientific Bureau of the University of Catania for the language support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Perkins, R.B.; Guido, R.C.; Castle, P.H.; Chelmow, D.; Einstein, M.H.; Garcia, F.; Huh, W.K.; Kim, J.; Moscicki, A.B.; Nayar, R.; et al. The 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines Committee 2019 ASCCP Risk-Based Management Consensus Guidelines for Abnormal Cervical Cancer Screening Tests and Cancer Precursors. J. Low Genit. Tract. Dis 2020, 24, 102–131.

- Ayhan, A.; Tuncer, H.A.; Reyhan, N.H.; Kuscu, E.; Dursun, P. Risk Factors for Residual Disease after Cervical Conization in Patients with Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Grades 2 and 3 and Positive Surgical Margins. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2016, 201, 1–6.

- Bruno, M.T.; Bonanno, G.; Sgalambro, F.; Cavallaro, A.; Boemi, S. Overexpression of E6/E7 mRNA HPV Is a Prognostic Biomarker for Residual Disease Progression in Women Undergoing LEEP for Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia 3. Cancers 2023, 15, 4203. [CrossRef]

- Ouh, Y.-T.; Cho, H.W.; Kim, S.M.; Min, K.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Song, J.-Y.; Lee, J.-K.; Lee, N.W.; Hong, J.H. Risk Factors Type-Specific Persistence of High-Risk Human Papillomavirus and Residual/Recurrent Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia after Surgical Treatment. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2020, 63, 631–642. [PubMed].

- Bruno, M.T.; Guaita, A.; Boemi, S.; Mazza, G.; Sudano, M.C.; Palumbo, M. Performance of p16/Ki67 Immunostaining for Triage of Elderly Women with Atypical Squamous Cells of Undetermined Significance. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3400. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson L., Sparen S., Gustafsson M., et al. Low efficiency of cytologic screening for cancer in situ of the cervix in older women. Int J Cancer, 1995, 63,6: 804-809.

- Bruno, M.T.; Valenti, G.; Cassaro, N.; Palermo, I.; Incognito, G.G.; Cavallaro, A.G.; Sgalambro, F.; Panella, M.M.; Mereu, L. The Coexistence of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia (CIN3) and Adenocarcinoma In Situ (AIS) in LEEP Excisions Performed for CIN3. Cancers 2024, 16, 847. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.B., Roh, J.W., Kim, J.W., Park NH , Song YS, Lee HP. A comparison of the therapeutic efficacies of large loop excision of the transformation zone and hysterectomy for the treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia III. Int J Gynecol Cancer,2001, 11: 387-391.

- Schockaert S. and Poppe W. And ArbynM. and Verguts T., Verguts J,. Incidence of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia after hysterectomy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a retrospective study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2008, 199, 2, 113.e1-113.e5.

- Strander B, Hallgren J, Sparen P. Effect of ageing on cervical or vaginal cancer in Swedish women previously treated for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: population based cohort study of long term incidence and mortality. BMJ 2014; 348: f7361.

- Sillman FH, Fruchter RG, Chen YS, Camilien L, Sedlis A, McTigue E. Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: risk factors for persistence, recurrence, and invasion and its management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176:93–99. [PubMed].

- Darragh TM, Colgan TJ, Thomas Cox J, Heller DS, Henry MR, Luff RD, McCalmont T, Nayar R, Palefsky JM, Stoler MH, Wilkinson EJ, Zaino RJ, Wilbur DC; Members of the LAST Project Work Groups. The lower anogenital squamous terminology standardization project for HPV-associated lesions: background and consensus recommendations from the College of American Pathologists and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2013; 32:76–115.

- Castle, P. Schiffman, M., Bratti, M. C., Hildesheim, A., Herrero, R., Hutchinson, M.L., Rodriguez, A. C., Wacholder, S., Sherman, M. E.,Kendall, H., Viscidi, R.P., Jeronimo, J., Schussler, J. E.,Burk, R. D.A Population-Based Study of Vaginal Human Papillomavirus Infection in Hysterectomized Women. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2004, 190,3:458-467.

- Kesic V, Carcopino X, Preti M et al (2023) The European Society of Gynaecological Oncology (ESGO), the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD), the European College for the Study of Vulval Disease (ECSVD), and the European Federation for Colposcopy (EFC) consensus statement on the management of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Int J Gynecol Cancer 33(4):446–461.

- Stokes-Lampard H, Wilson S, Waddell C, Ryan A, Holder R, Kehoe S. Vaginal vault smears after hysterectomy for reasons other than malignancy: a systematic review of the literature. BJOG 2006; 113: 1354–65.

- https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2008/03/31/08A02109/sg.

- Bruno, M.T., Caruso, S., Bica, F. et al. Evidence for HPV DNA in the placenta of women who resorted to elective abortion. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 21, 485 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Kim MK, Lee IH, Lee KH (2018) Clinical outcomes and risk of recurrence among patients with vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: a comprehensive analysis of 576 cases. J Gynecol Oncol 29(1):e6.

- Sand, F.L., Munk,C., Jensen S.M., Svahn M.F., Frederiksen K., Kjaer S.K.. Long-term risk for noncervical Anogenital Cancer in women with previously diagnosed high-grade cervical intraepithelial Neoplasia: a Danish Nationwide cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev., 2016, 25, 7:1090-1097.

- Ebisch, R.M.F., Rutten D.W.E., IntHout j., Melchers W.J.G., Massuge l., Bulten j., Bekkers R L M., Siebers A. G. Long-lasting increased risk of human papillomavirus-related carcinomas and premalignancies after cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3: a population-based cohort study. J. Clin. Oncol., 35 (22) (2017), pp. 2542-2550.

- Dodge JA, Eltabbakh GH, Mount SL, Walker RP, Morgan A. Clinical features and risk of recurrence among patients with vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Gynecol Oncol 83: 363-369, 2001.

- Edgren, P. Sparen. Risk of anogenital cancer after diagnosis of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a prospective population-based study.The Lancet Oncology, 8 (4) (2007), pp. 311-316.

- I. Kalliala, A. Anttila, E. Pukkala, P. Nieminen. Risk of cervical and other cancers after treatment of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: retrospective cohort study. The BMJ, 331 (7526) (2005), pp. 1183-1185.

- A.B. Moscicki, M. Schiffman, A. Burchell, G. Albero, A.R. Giuliano, M.T. Goodman, et al. Updating the natural history of human papillomavirus and anogenital cancers. Vaccine, 30 (Suppl. 5) (2012), pp. F24-F33.

- Bryan S, Barbara C, Thomas J et al (2019) HPV vaccine in the treatment of usual type vulval and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: a systematic review. BMC Women Health. 19(1):3.

- Ao M, Zheng D, Wang J et al (2022) A retrospective study of cytology and HPV genotypes results of 3229 vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia patients. J Med Virol 94(2):737–744.

- Cao D , Wu D , Xu Y. Neoplasia intraepiteliale vaginale in pazienti dopo isterectomia totale . Curr Probl Cancro . 2021 ; 45 ( 3 ):100687.

- Vinokurova, S.,Wentzensen, N,,Einenkel, J.,Klaes, R.,Ziegert, C.,Melsheimer, P.,Sartor, H.,Horn, L., Höckel, M., von Knebel Doeberitz, M. Clonal History of Papillomavirus-Induced Dysplasia in the Female Lower Genital Tract,2005, 2005/12/21. 10.1093/jnci/dji428. JNCI: Journal of the National Cancer Institute. J Natl Cancer Inst.

- WP. Soutter. The treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia after hysterectomy. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 95 (1988), pp. 961-962.

- Bruno, M.T.; Valenti, G.; Ruggeri, Z.; Incognito, G.G.; Coretti, P.; Montana, G.D.; Panella, M.M.; Mereu, L. Correlation of the HPV 16 Genotype Persistence in Women Undergoing LEEP for CIN3 with the Risk of CIN2+ Relapses in the First 18 Months of Follow-Up: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. Diagnostics 2024, 14, 509. [CrossRef]

- Zeligs KP, Byrd K, Tarney CM, Howard RS, Sims BD, Hamilton CA, et al. Uno studio clinicopatologico sulla neoplasia intraepiteliale vaginale. Obstet Gynecol. 2013; 122:1223–1230.

- Ratnavelu N, Patel A, Fisher AD, Galaal K, Cross P, Naik R. Neoplasia intraepiteliale vaginale di alto grado: possiamo essere selettivi su chi trattiamo? BJOG. 2013; 120:887–893.

- Hodeib M, Cohen JG, Mehta S, Rimel BJ, Walsh CS, Li AJ, et al. Recidiva e rischio di progressione verso tumori maligni del tratto genitale inferiore nelle donne con VAIN di alto grado. Ginecol Oncol. 2016; 141:507–510.

- Sopracordevole F, Moriconi L, Di Giuseppe J, Alessandrini L, Del Piero E, Giorda G, et al. Trattamento escissionale laser per neoplasia intraepiteliale vaginale per escludere l'invasione: qual è il rischio di complicanze? J Dis. tratto genitale basso. 2017; 21:311–314.

- Atay V, Muhcu M: Treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancer Therap 5: 19-28, 2007. Google Scholar.

- Hoffman MS, Roberts WS, LaPolla JP, Fiorica JV, Cavanagh D. Laser vaporization of grade 3 vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991 Nov;165(5 Pt 1):1342-4. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rome RM., England P.G.,. Management of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: a series of 132 cases with long-term follow-up.Int J Gynecol Cancer, 2000, 10: 38.

- Cong, Qing MD; Fu, Zhongpeng MD; Zhang, Di MD; Sui, Long MD Importance of colposcopy impression in the early diagnosis of posthysterectomy vaginal Cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis, 2019,23,1:13-.

- Indermaur MD, Martino MA, Fiorica JV, Roberts WS, Hoffman MS: Upper vaginectomy for the treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005, 193(2): 577-580.

- Wei, J., Wu, Y. Comprehensive evaluation of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia development after hysterectomy: insights into diagnosis and treatment strategies. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yu D, Qu P, Liu M. Clinical presentation, treatment, and outcomes associated with vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia: a retrospective study of 118 patients. J Obstetr Gynaecol Res 2021, 47(5):1624–1630.

- Kim J, Kim J, Kim K et al Risk factor and treatment of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia after hysterectomy for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. J Low Genit Tract Dis 26(2):147.

- Bruno, M., Cassaro, N., Garofalo, S. et al. HPV16 persistent infection and recurrent disease after LEEP. Virol J 16, 148 (2019). [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).