Submitted:

30 May 2024

Posted:

31 May 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Experimental Setup and Data Acquisition

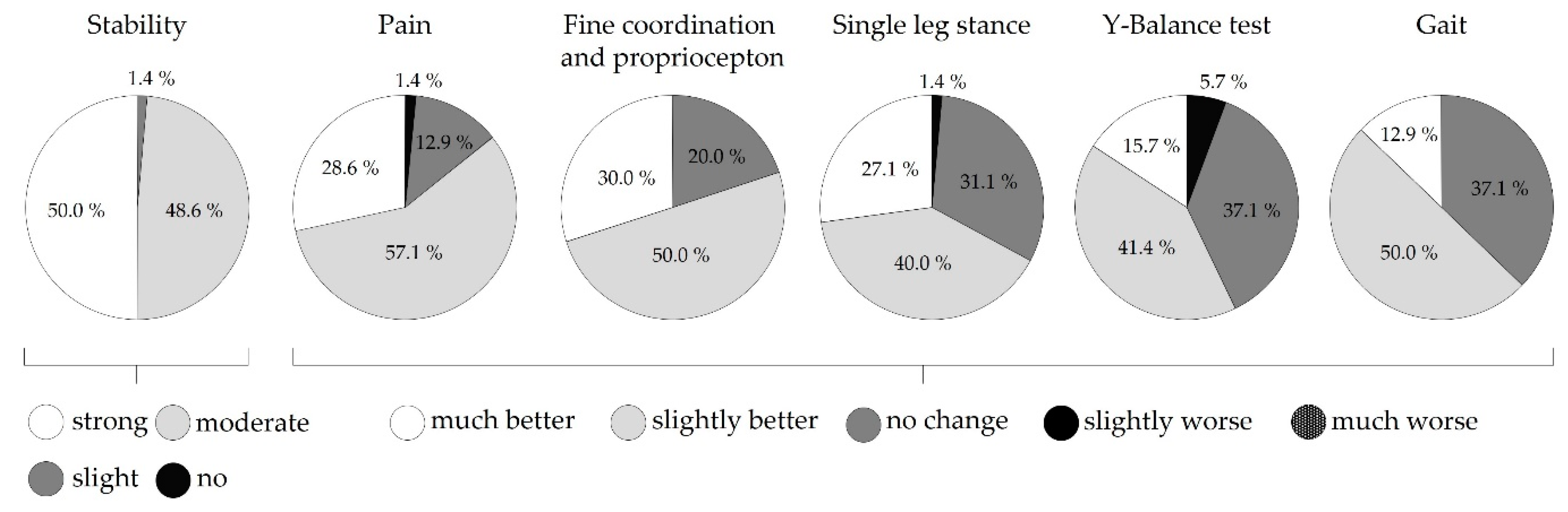

2.2.1. Subjective Ratings

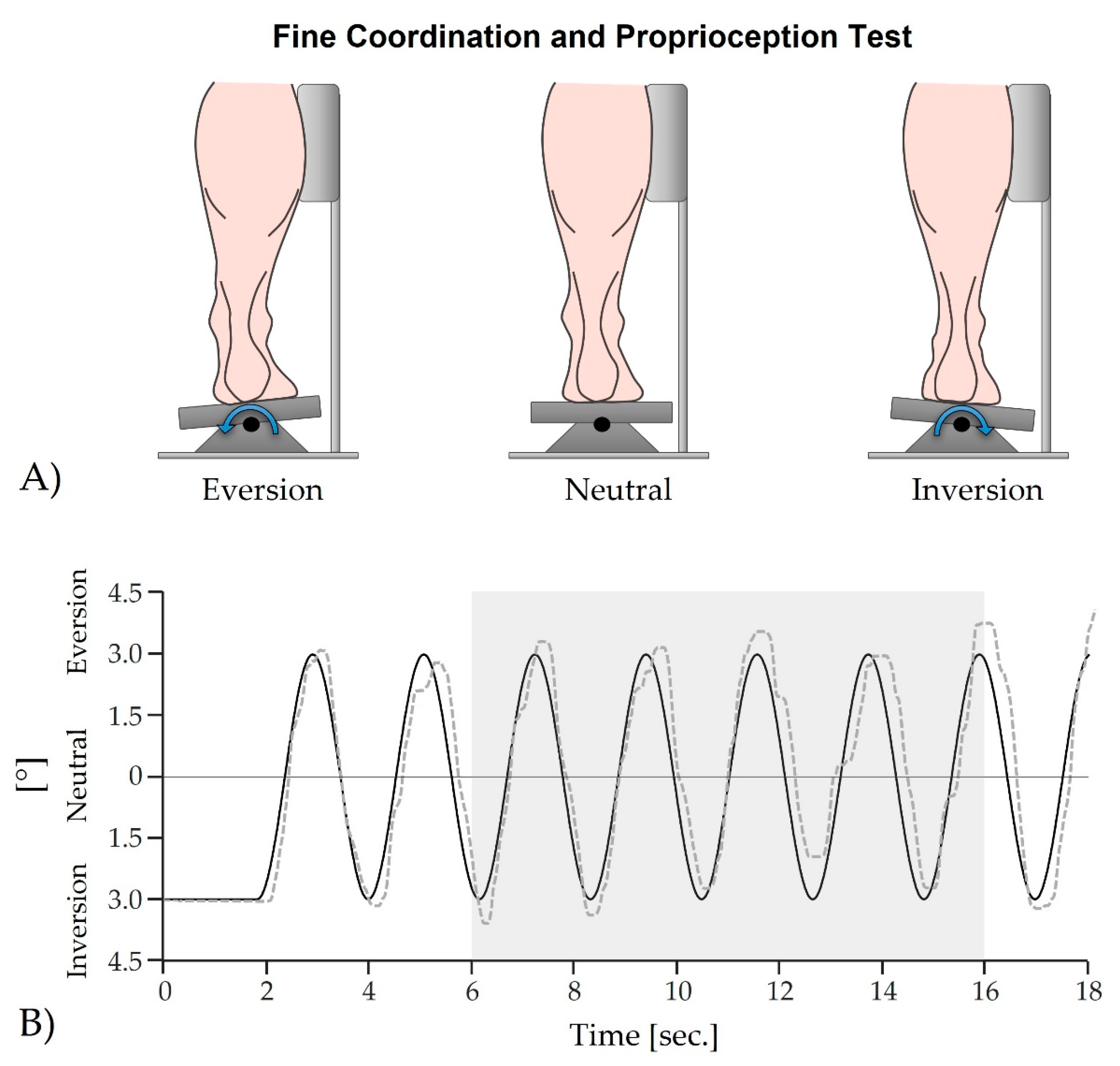

2.2.2. Fine Coordination and Proprioception Test

2.2.3. Single Leg Stance (Quasi-Static Postural Stability)

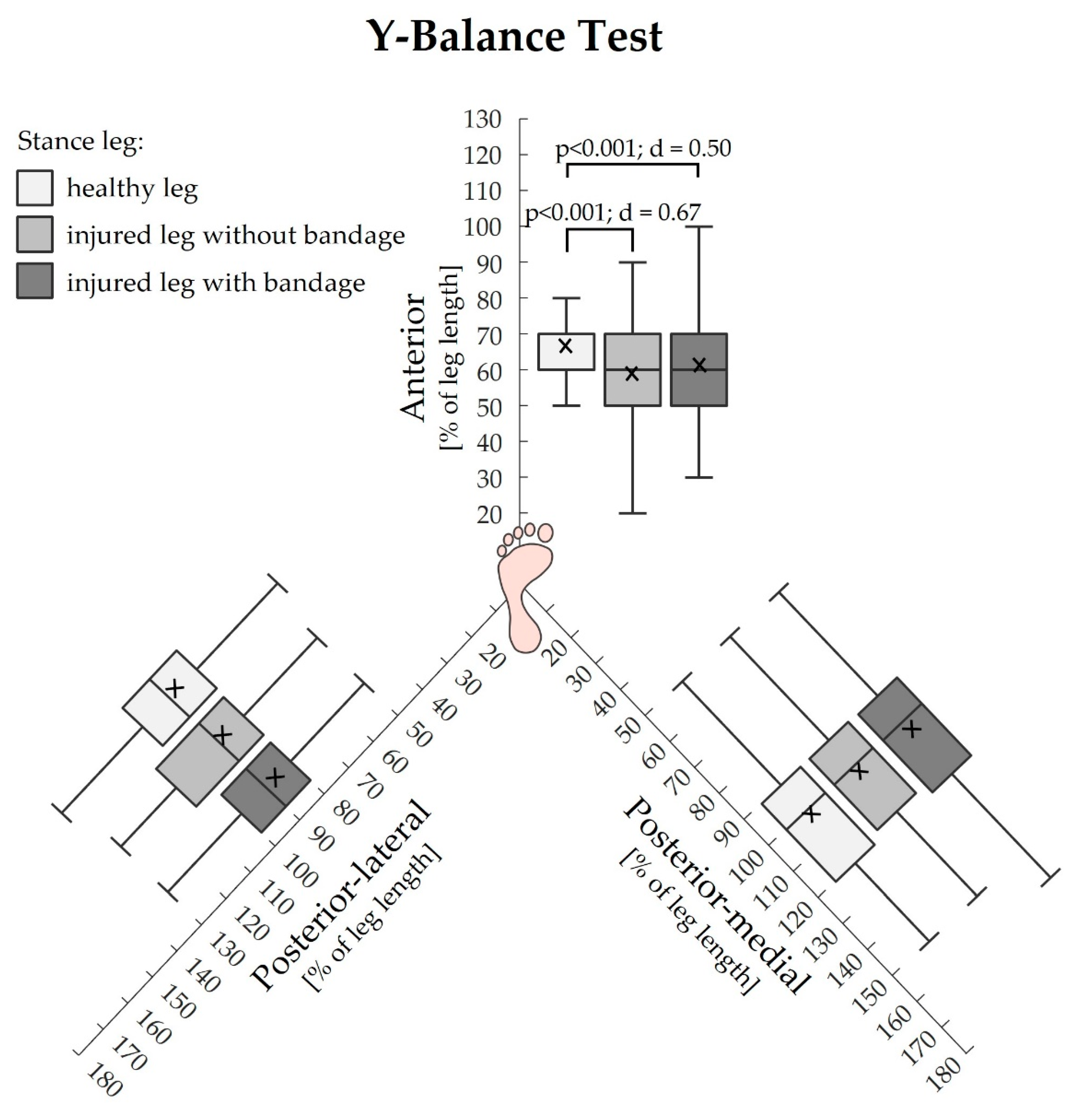

2.2.4. Y-Balance Test (Dynamic Postural Stability)

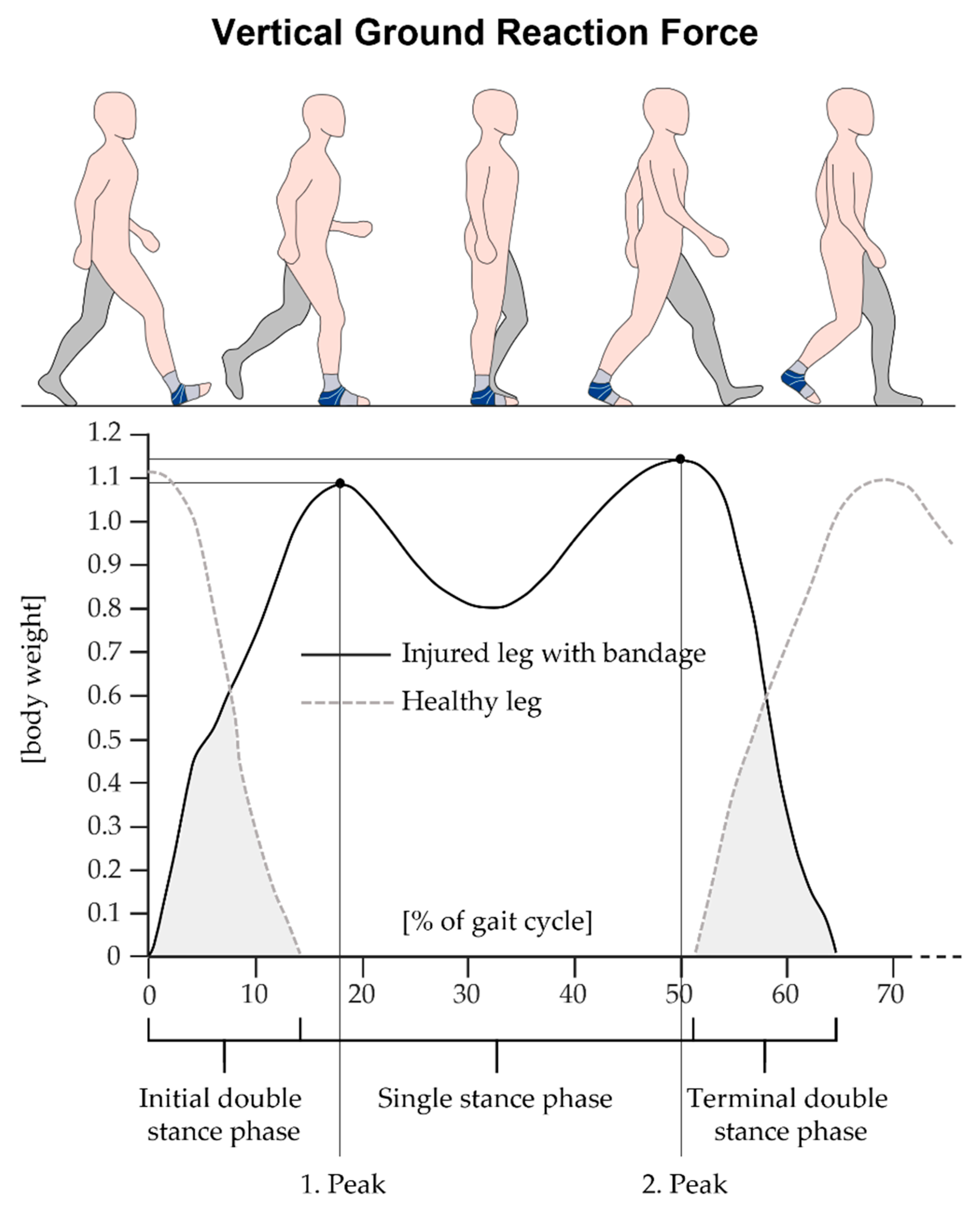

2.2.5. Gait

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical Data:

3.2. Fine Coordination and Proprioception Test:

3.3. Single Leg Stance (Quasi-Static Postural Stability):

3.4. Y-Balance Test (Dynamic Postural Stability):

3.5. Gait:

4. Discussion

4.1. Fine Coordination and Proprioception Test

4.1.1. Effects of the Injury

4.1.2. Effects of the Bandage

4.2. Motor Performance

4.2.1. Effects of the Injury

4.2.2. Effects of the Bandage

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lieberman, D.E.; Venkadesan, M.; Werbel, W.A.; Daoud, A.I.; D’Andrea, S.; Davis, I.S.; Mang’Eni, R.O.; Pitsiladis, Y. Foot strike patterns and collision forces in habitually barefoot versus shod runners. Nature 2010, 463, 531–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ericksen, H.M.; Gribble, P.A.; Pfile, K.R.; Pietrosimone, B.G. Different modes of feedback and peak vertical ground reaction force during jump landing: a systematic review. J. Athl. Train. 2013, 48, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faraji, E.; Daneshmandi, H.; Atri, A.E.; Onvani, V.; Namjoo, F.R. Effects of prefabricated ankle orthoses on postural stability in basketball players with chronic ankle instability. Asian J. Sports Med. 2012, 3, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, D.T.-P.; Hong, Y.; Chan, L.-K.; Yung, P.S.-H.; Chan, K.-M. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Med. 2007, 37, 73–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luciano, A.d.P.; Lara, L.C.R. Epidemiological study of foot and ankle injuries in recreational sports. Acta Ortop. Bras. 2012, 20, 339–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, M.C.G.; Hendler, K.G.; Kuriki, H.U.; Barbosa, R.I.; das Neves, L.M.S.; Guirro, E.C.d.O.; Guirro, R.R.d.J.; Marcolino, A.M. Influence of neoprene ankle orthoses on dynamic balance during a vertical jump in healthy individuals and with sprain history: A cross-sectional study. Gait Posture 2023, 101, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hootman, J.M.; Dick, R.; Agel, J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J. Athl. Train. 2007, 42, 311–319. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Abbasi, F.; Bahramizadeh, M.; Hadadi, M. Comparison of the effect of foot orthoses on Star Excursion Balance Test performance in patients with chronic ankle instability. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2019, 43, 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Young, S.; Wallmann, H.W.; Quiambao, K.L.; Grimes, B.M. The Effects of Whole Body Vibration on the Limits of Stability in Adults With Subacute Ankle Injury. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 749–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerkhoffs, G.M.; van den Bekerom, M.; Elders, L.A.M.; van Beek, P.A.; Hullegie, W.A.M.; Bloemers, G.M.F.M.; de Heus, E.M.; Loogman, M.C.M.; Rosenbrand, K.C.J.G.M.; Kuipers, T.; et al. Diagnosis, treatment and prevention of ankle sprains: an evidence-based clinical guideline. Br. J. Sports Med. 2012, 46, 854–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Sánchez, F.J.; Ruiz-Muñoz, M.; Martín-Martín, J.; Coheña-Jimenez, M.; Perez-Belloso, A.J.; Pilar Romero-Galisteo, R.; Gónzalez-Sánchez, M. Management and treatment of ankle sprain according to clinical practice guidelines: A PRISMA systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2022, 101, e31087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadadi, M.; Haghighat, F.; Mohammadpour, N.; Sobhani, S. Effects of Kinesiotape vs Soft and Semirigid Ankle Orthoses on Balance in Patients With Chronic Ankle Instability: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2020, 41, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vasconcelos, G.S.; Cini, A.; Sbruzzi, G.; Lima, C.S. Effects of proprioceptive training on the incidence of ankle sprain in athletes: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Rehabil. 2018, 32, 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, J.; Anson, J.; Waddington, G.; Adams, R.; Liu, Y. The Role of Ankle Proprioception for Balance Control in relation to Sports Performance and Injury. Biomed Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 842804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willems, T.; Witvrouw, E.; Verstuyft, J.; Vaes, P.; de Clercq, D. Proprioception and Muscle Strength in Subjects With a History of Ankle Sprains and Chronic Instability. J. Athl. Train. 2002, 37, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, A.S.N.; Hui-Chan, C.W.Y. Ankle joint proprioception and postural control in basketball players with bilateral ankle sprains. Am. J. Sports Med. 2005, 33, 1174–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiller, C.E.; Nightingale, E.J.; Lin, C.-W.C.; Coughlan, G.F.; Caulfield, B.; Delahunt, E. Characteristics of people with recurrent ankle sprains: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 2011, 45, 660–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerosch, J.; Prymka, M. Proprioception and joint stability. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 1996, 4, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearson, K.G. Proprioceptive regulation of locomotion. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 1995, 5, 786–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riemann, B.L.; Lephart, S.M. The Sensorimotor System, Part II: The Role of Proprioception in Motor Control and Functional Joint Stability. J. Athl. Train. 2002, 37, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Heß, T.; Milani, T.L.; Meixensberger, J.; Krause, M. Postural performance and plantar cutaneous vibration perception in patients with idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus. Heliyon 2021, 7, e05811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heß, T.; Themann, P.; Oehlwein, C.; Milani, T.L. Does Impaired Plantar Cutaneous Vibration Perception Contribute to Axial Motor Symptoms in Parkinson's Disease? Effects of Medication and Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation. Brain Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terada, M.; Pietrosimone, B.G.; Gribble, P.A. Therapeutic interventions for increasing ankle dorsiflexion after ankle sprain: a systematic review. J. Athl. Train. 2013, 48, 696–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delahunt, E.; Bleakley, C.M.; Bossard, D.S.; Caulfield, B.M.; Docherty, C.L.; Doherty, C.; Fourchet, F.; Fong, D.T.; Hertel, J.; Hiller, C.E.; et al. Clinical assessment of acute lateral ankle sprain injuries (ROAST): 2019 consensus statement and recommendations of the International Ankle Consortium. Br. J. Sports Med. 2018, 52, 1304–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roos, K.G.; Kerr, Z.Y.; Mauntel, T.C.; Djoko, A.; Dompier, T.P.; Wikstrom, E.A. The Epidemiology of Lateral Ligament Complex Ankle Sprains in National Collegiate Athletic Association Sports. Am. J. Sports Med. 2017, 45, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otsuka, S.; Papadopoulos, K.; Bampouras, T.M.; Maestroni, L. What is the effect of ankle disk training and taping on proprioception deficit after lateral ankle sprains among active populations? - A systematic review. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2022, 31, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Röpke, M.; Piatek, S.; Ziai, P. Akute Sprunggelenkinstabilität durch Distorsion. Arthroskopie 2015, 28, 116–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stürmer, K.M.; Rammelt, S.; Richter, M.; Walther, M. Frische Außenbandruptur am Oberen Sprunggelenk. Leitlinien Unfallchirurgie 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alghadir, A.H.; Iqbal, Z.A.; Iqbal, A.; Ahmed, H.; Ramteke, S.U. Effect of Chronic Ankle Sprain on Pain, Range of Motion, Proprioception, and Balance among Athletes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, D.T.-P.; Man, C.-Y.; Yung, P.S.-H.; Cheung, S.-Y.; Chan, K.-M. Sport-related ankle injuries attending an accident and emergency department. Injury 2008, 39, 1222–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKay, G.D.; Goldie, P.A.; Payne, W.R.; Oakes, B.W. Ankle injuries in basketball: injury rate and risk factors. Br. J. Sports Med. 2001, 35, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Best, R.; Böhle, C.; Schiffer, T.; Petersen, W.; Ellermann, A.; Brueggemann, G.P.; Liebau, C. Early functional outcome of two different orthotic concepts in ankle sprains: a randomized controlled trial. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2015, 135, 993–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuerst, P.; Gollhofer, A.; Wenning, M.; Gehring, D. People with chronic ankle instability benefit from brace application in highly dynamic change of direction movements. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2021, 14, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartsell, H.D.; Spaulding, S.J. Effectiveness of external orthotic support on passive soft tissue resistance of the chronically unstable ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 1997, 18, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheuffelen, C.; Rapp, W.; Gollhofer, A.; Lohrer, H. Orthotic devices in functional treatment of ankle sprain. Stabilizing effects during real movements. Int. J. Sports Med. 1993, 14, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halseth, T.; McChesney, J.W.; Debeliso, M.; Vaughn, R.; Lien, J. The effects of kinesio™ taping on proprioception at the ankle. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2004, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Perlau, R.; Frank, C.; Fick, G. The effect of elastic bandages on human knee proprioception in the uninjured population. Am. J. Sports Med. 1995, 23, 251–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandacoomarasamy, A.; Barnsley, L. Long term outcomes of inversion ankle injuries. Br. J. Sports Med. 2005, 39, e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safran, M.R.; Benedetti, R.S.; Bartolozzi, A.R., 3rd; Mandelbaum, B.R. Lateral ankle sprains: A comprehensive review: part 1: Etiology, pathoanatomy, histopathogenesis, and diagnosis. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, S429–S437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, M.S.; Chan, K.M.; So, C.H.; Yuan, W.Y. An epidemiological survey on ankle sprain. Br. J. Sports Med. 1994, 28, 112–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilper, A.; Lederer, A.-K.; Niklaus, L.; Milani, T.; Langenhan, R.; Schütz, L.; Reimers, N. Heilungsverlauf und Behandlungsergebnisse nach akutem Supinationstrauma des oberen Sprunggelenkes. Sports Orthopaedics and Traumatology 2023, 39, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hintermann, B.; Boss, A.; Schäfer, D. Arthroscopic findings in patients with chronic ankle instability. Am. J. Sports Med. 2002, 30, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hupperets, M.D.W.; Verhagen, E.A.L.M.; van Mechelen, W. Effect of unsupervised home based proprioceptive training on recurrences of ankle sprain: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009, 339, b2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, P.; Mei, Q.; Xiang, L.; Fernandez, J.; Gu, Y. Differences in the locomotion biomechanics and dynamic postural control between individuals with chronic ankle instability and copers: a systematic review. Sports Biomech. 2022, 21, 531–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nelson, S.; Wilson, C.S.; Becker, J. Kinematic and Kinetic Predictors of Y-Balance Test Performance. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2021, 16, 371–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, C.; Bleakley, C.; Hertel, J.; Caulfield, B.; Ryan, J.; Delahunt, E. Dynamic balance deficits in individuals with chronic ankle instability compared to ankle sprain copers 1 year after a first-time lateral ankle sprain injury. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2016, 24, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, C.; Bleakley, C.; Hertel, J.; Caulfield, B.; Ryan, J.; Delahunt, E. Dynamic Balance Deficits 6 Months Following First-Time Acute Lateral Ankle Sprain: A Laboratory Analysis. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 45, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriner, M.L.; Houston, M.N.; Kirby, J.L.; Hoch, M.C. Contributing factors to star excursion balance test performance in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Gait Posture 2015, 41, 912–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, L.C.; Carcia, C.R.; Hertel, J.; Shultz, S.J. Efficacy of the Star Excursion Balance Tests in Detecting Reach Deficits in Subjects With Chronic Ankle Instability. J. Athl. Train. 2002, 37, 501–506. [Google Scholar]

- Perry. Gait Analysis: Normal and Pathological Function, 2nd Edition; Slack Incorporated, 2010. ISBN 978-1-55642-766-4.

- Hadadi, M.; Haghighat, F.; Mohammadpour, N.; Sobhani, S. Effects of Kinesiotape vs Soft and Semirigid Ankle Orthoses on Balance in Patients With Chronic Ankle Instability: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Foot Ankle Int. 2020, 41, 793–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konradsen, L.; Magnusson, P. Increased inversion angle replication error in functional ankle instability. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2000, 8, 246–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alawna, M.; Unver, B.; Yuksel, E. Effect of ankle taping and bandaging on balance and proprioception among healthy volunteers. Sport Sci Health 2021, 17, 665–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punt, I.M.; Ziltener, J.-L.; Laidet, M.; Armand, S.; Allet, L. Gait and physical impairments in patients with acute ankle sprains who did not receive physical therapy. PM R 2015, 7, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hubbard, T.J.; Cordova, M. Mechanical instability after an acute lateral ankle sprain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2009, 90, 1142–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabbaligere, R.; Lee, B.-C.; Layne, C.S. Balancing sensory inputs: Sensory reweighting of ankle proprioception and vision during a bipedal posture task. Gait Posture 2017, 52, 244–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, Q.; Sun, W.; Song, Q. Balancing sensory inputs: somatosensory reweighting from proprioception to tactile sensation in maintaining postural stability among older adults with sensory deficits. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1165010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavailler, S.; Hintzy, F.; Horvais, N.; Forestier, N. Cutaneous stimulation at the ankle: a differential effect on proprioceptive postural control according to the participants' preferred sensory strategy. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2016, 9, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alawna, M.; Mohamed, A.A. Short-term and long-term effects of ankle joint taping and bandaging on balance, proprioception and vertical jump among volleyball players with chronic ankle instability. Phys. Ther. Sport 2020, 46, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refshauge, K.M.; Raymond, J.; Kilbreath, S.L.; Pengel, L.; Heijnen, I. The effect of ankle taping on detection of inversion-eversion movements in participants with recurrent ankle sprain. Am. J. Sports Med. 2009, 37, 371–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refshauge, K.M.; Kilbreath, S.L.; Raymond, J. The effect of recurrent ankle inversion sprain and taping on proprioception at the ankle. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2000, 32, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spanos, S.; Brunswic, M.; Billis, E. The effect of taping on the proprioception of the ankle in a non-weight bearing position, amongst injured athletes. The Foot 2008, 18, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerosch, J.; Hoffstetter, I.; Bork, H.; Bischof, M. The influence of orthoses on the proprioception of the ankle joint. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 1995, 3, 39–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thonnard, J.L.; Bragard, D.; Willems, P.A.; Plaghki, L. Stability of the braced ankle. A biomechanical investigation. Am. J. Sports Med. 1996, 24, 356–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monaghan, K.; Delahunt, E.; Caulfield, B. Ankle function during gait in patients with chronic ankle instability compared to controls. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 2006, 21, 168–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.J.; Liu, W. Possible factors related to functional ankle instability. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2008, 38, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohrer, H.; Nauck, T.; Gehring, D.; Wissler, S.; Braag, B.; Gollhofer, A. Differences between mechanically stable and unstable chronic ankle instability subgroups when examined by arthrometer and FAAM-G. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2015, 10, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertel, J.; Denegar, C.R.; Buckley, W.E.; Sharkey, N.A.; Stokes, W.L. Effect of rearfoot orthotics on postural sway after lateral ankle sprain. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2001, 82, 1000–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pourkazemi, F.; Hiller, C.; Raymond, J.; Black, D.; Nightingale, E.; Refshauge, K. Using Balance Tests to Discriminate Between Participants With a Recent Index Lateral Ankle Sprain and Healthy Control Participants: A Cross-Sectional Study. J. Athl. Train. 2016, 51, 213–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitchell, A.; Dyson, R.; Hale, T.; Abraham, C. Biomechanics of ankle instability. Part 2: Postural sway-reaction time relationship. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2008, 40, 1522–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heß, T.; Oehlwein, C.; Milani, T.L. Anticipatory Postural Adjustments and Compensatory Postural Responses to Multidirectional Perturbations-Effects of Medication and Subthalamic Nucleus Deep Brain Stimulation in Parkinson's Disease. Brain Sci. 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintsaar, A.; Brynhildsen, J.; Tropp, H. Postural corrections after standardised perturbations of single limb stance: effect of training and orthotic devices in patients with ankle instability. Br. J. Sports Med. 1996, 30, 151–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullock-Saxton, J.E. Local sensation changes and altered hip muscle function following severe ankle sprain. Phys. Ther. 1994, 74, 17–28, discussion 28-31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKeon, P.O.; Hertel, J. Systematic review of postural control and lateral ankle instability, part I: can deficits be detected with instrumented testing. J. Athl. Train. 2008, 43, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, S.E.; Guskiewicz, K.M. Examination of static and dynamic postural stability in individuals with functionally stable and unstable ankles. Clin. J. Sport Med. 2004, 14, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCann, R.S.; Crossett, I.D.; Terada, M.; Kosik, K.B.; Bolding, B.A.; Gribble, P.A. Hip strength and star excursion balance test deficits of patients with chronic ankle instability. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2017, 20, 992–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pozzi, F.; Moffat, M.; Gutierrez, G. NEUROMUSCULAR CONTROL DURING PERFORMANCE OF A DYNAMIC BALANCE TASK IN SUBJECTS WITH AND WITHOUT ANKLE INSTABILITY. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2015, 10, 520–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaber, H.; Lohman, E.; Daher, N.; Bains, G.; Nagaraj, A.; Mayekar, P.; Shanbhag, M.; Alameri, M. Neuromuscular control of ankle and hip during performance of the star excursion balance test in subjects with and without chronic ankle instability. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0201479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basnett, C.R.; Hanish, M.J.; Wheeler, T.J.; Miriovsky, D.J.; Danielson, E.L.; Barr, J.B.; Grindstaff, T.L. Ankle dorsiflexion range of motion influences dynamic balance in individuals with chronic ankle instability. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2013, 8, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Terada, M.; Harkey, M.S.; Wells, A.M.; Pietrosimone, B.G.; Gribble, P.A. The influence of ankle dorsiflexion and self-reported patient outcomes on dynamic postural control in participants with chronic ankle instability. Gait Posture 2014, 40, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosik, K.B.; Johnson, N.F.; Terada, M.; Thomas, A.C.; Mattacola, C.G.; Gribble, P.A. Decreased dynamic balance and dorsiflexion range of motion in young and middle-aged adults with chronic ankle instability. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2019, 22, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dundas, M.A.; Gutierrez, G.M.; Pozzi, F. Neuromuscular control during stepping down in continuous gait in individuals with and without ankle instability. Journal of Sports Sciences 2014, 32, 926–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenenbaum, S.; Chechik, O.; Bariteau, J.; Bruck, N.; Beer, Y.; Falah, M.; Segal, G.; Mor, A.; Elbaz, A. Gait abnormalities in patients with chronic ankle instability can improve following a non-invasive biomechanical therapy: a retrospective analysis. J. Phys. Ther. Sci. 2017, 29, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigi, R.; Haim, A.; Luger, E.; Segal, G.; Melamed, E.; Beer, Y.; Nof, M.; Nyska, M.; Elbaz, A. Deviations in gait metrics in patients with chronic ankle instability: a case control study. J. Foot Ankle Res. 2015, 8, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spaulding, S.J.; Livingston, L.A.; Hartsell, H.D. The influence of external orthotic support on the adaptive gait characteristics of individuals with chronically unstable ankles. Gait Posture 2003, 17, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koldenhoven, R.M.; Hart, J.; Saliba, S.; Abel, M.F.; Hertel, J. Gait kinematics & kinetics at three walking speeds in individuals with chronic ankle instability and ankle sprain copers. Gait Posture 2019, 74, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delahunt, E.; Monaghan, K.; Caulfield, B. Altered neuromuscular control and ankle joint kinematics during walking in subjects with functional instability of the ankle joint. Am. J. Sports Med. 2006, 34, 1970–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louwerens, J.W.; van Linge, B.; de Klerk, L.W.; Mulder, P.G.; Snijders, C.J. Peroneus longus and tibialis anterior muscle activity in the stance phase. A quantified electromyographic study of 10 controls and 25 patients with chronic ankle instability. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1995, 66, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doherty, C.; Bleakley, C.; Hertel, J.; Caulfield, B.; Ryan, J.; Delahunt, E. Locomotive biomechanics in persons with chronic ankle instability and lateral ankle sprain copers. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2016, 19, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyska, M.; Shabat, S.; Simkin, A.; Neeb, M.; Matan, Y.; Mann, G. Dynamic force distribution during level walking under the feet of patients with chronic ankle instability. Br. J. Sports Med. 2003, 37, 495–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witchalls, J.B.; Waddington, G.; Adams, R.; Blanch, P. Chronic ankle instability affects learning rate during repeated proprioception testing. Phys. Ther. Sport 2014, 15, 106–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, A.J.Y.; Lin, W.-H. Twelve-week biomechanical ankle platform system training on postural stability and ankle proprioception in subjects with unilateral functional ankle instability. Clin. Biomech. (Bristol, Avon) 2008, 23, 1065–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaes, P.; Duquet, W.; van Gheluwe, B. Peroneal Reaction Times and Eversion Motor Response in Healthy and Unstable Ankles. J. Athl. Train. 2002, 37, 475–480. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wikstrom, E.A.; Naik, S.; Lodha, N.; Cauraugh, J.H. Bilateral balance impairments after lateral ankle trauma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gait Posture 2010, 31, 407–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadadi, M.; Abbasi, F. Comparison of the Effect of the Combined Mechanism Ankle Support on Static and Dynamic Postural Control of Chronic Ankle Instability Patients. Foot Ankle Int. 2019, 40, 702–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baier, M.; Hopf, T. Ankle orthoses effect on single-limb standing balance in athletes with functional ankle instability. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 1998, 79, 939–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskiewicz, K.M.; Perrin, D.H. Effect of orthotics on postural sway following inversion ankle sprain. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 1996, 23, 326–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orteza, L.C.; Vogelbach, W.D.; Denegar, C.R. The effect of molded and unmolded orthotics on balance and pain while jogging following inversion ankle sprain. J. Athl. Train. 1992, 27, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- Janssen, K.; van den Berg, A.; van Mechelen, W.; Verhagen, E. User Survey of 3 Ankle Braces in Soccer, Volleyball, and Running: Which Brace Fits Best? J. Athl. Train. 2017, 52, 730–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, C.; Stotz, A.; Gmachowski, J.; Rahlf, A.L.; Hamacher, D.; Hollander, K.; Zech, A. Is an Elastic Ankle Support Effective in Improving Jump Landing Performance, and Static and Dynamic Balance in Young Adults With and Without Chronic Ankle Instability? J. Sport Rehabil. 2020, 29, 789–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpes, F.P.; Mota, C.B.; Faria, I.E. On the bilateral asymmetry during running and cycling - a review considering leg preference. Phys. Ther. Sport 2010, 11, 136–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helme, M.; Tee, J.; Emmonds, S.; Low, C. Does lower-limb asymmetry increase injury risk in sport? A systematic review. Phys. Ther. Sport 2021, 49, 204–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadopoulos, E.S.; Nicolopoulos, C.; Anderson, E.G.; Curran, M.; Athanasopoulos, S. The role of ankle bracing in injury prevention, athletic performance and neuromuscular control: A review of the literature. The Foot 2005, 15, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Age [years] | Height [cm] |

Weight [kg] |

Gender | Side of the injured leg |

Pain rating |

Instability rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 34.8±11.8 | 173.3±10.1 | 78.7±16.4 | male 36; female 34 | left 32; right 38 | 1.6 ± 1.3 | 3.0 ± 2.2 |

| Injured structures of the ankle joint | n | Relative n to total number of subjects (70) [%] | ||||

| Anterior talofibular ligament | 54 | 84.4 | ||||

| Posterior talofibular ligament | 31 | 48.4 | ||||

| Calcaneofibular ligament | 38 | 59.4 | ||||

| Swelling | 53 | 82.8 | ||||

| General complaints | 61 | 95.3 | ||||

| pain | walking barefoot | standing barefoot | walking in shoes | standing in shoes | walking with bandage | standing with bandage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean ± SD | 1.60 ± 1.58 | 1.13 ± 1.45 | 1.69 ± 1.45 | 1.09 ± 1.27 | 1.18 ± 1.46 | 0.88 ± 1.25 |

| range [Min Max] |

[0 7] | [0 7] | [0 6] | [0 5] | [0 6] | [0 6] |

| Parameter | healthy leg |

Injured leg without bandage | Injured leg with bandage | p-value | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean deviation [°] | 1.30 ± 0.5 | 1.26 ± 0.5 | 1.20 ± 0.5 | 0.078 | - |

| Parameter | healthy leg |

Injured leg without bandage | Injured leg with bandage | p-value | d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COP length [mm] | 470.0 ± 115.9 a |

548.8 ± 145.1 a;b |

477.5 ± 106.7 b |

< 0.001 a < 0.001 b < 0.001 |

1.1 a 0.60 b 0.56 |

| COP 95% confidence area [mm²] | 217.6 ± 101.5 | 238.2 ± 91.1 | 216.3 ± 79.0 | 0.263 | - |

| Parameter | Walking injured leg without bandage | Walking injured leg with bandage | p-value | d | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| gait velocity [km/h] | 3.98 ± 0.67 | 4.01±0.59 | 0.251 | - | ||

| rel. double stance phase [% of gait cycle] |

29.17 ± 4.20 | 29.46 ± 4.22 | 0.121 | - | ||

| Parameter | healthy leg |

Injured leg without bandage | healthy leg |

Injured leg with bandage | p-value | d |

| rel. single stance phase [% of gait cycle] |

65.3 ± 2.7 a |

64.1 ± 2.5 a;b |

65.4 ± 3.2 c |

64.7 ± 2.9 b;c |

a < 0.001 b 0.018 c 0.013 |

a 0.46 b 0.22 c 0.24 |

| step length [cm] | 57.7 ± 6.1 a;b |

61.1 ± 7.8 a |

61.1 ± 8.5 b |

61.0 ± 7.3 |

a < 0.001 b < 0.001 |

a 0.49 b 0.46 |

| 1. Peak of the vertical force [body weight] |

1.07 ± 0.07 a |

1.05 ± 0.06 a;b |

1.07 ± 0.07 |

1.07 ± 0.07 b |

a 0.004 b 0.004 |

a 0.31 b 0.31 |

| 2. Peak of the vertical force [body weight] |

1.11 ± 0.07 a;b |

1.08 ± 0.07 b;c |

1.13 ± 0.06 a;d |

1.11 ± 0.06 c;d |

a 0.039 b < 0.001 c < 0.001 d 0.001 |

a 0.31 b 0.43 c 0.33 d 0.31 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).