1. Introduction

In the rapidly evolving landscape of technology, the Internet of Things (IoT) has emerged as a foundational element, transforming various sectors by enabling the interconnectivity of physical devices through the internet. These devices, ranging from simple sensors to complex systems, collect and exchange data, facilitating a smarter and more responsive environment. Concurrently, Machine Learning (ML) has seen remarkable advancements, enhancing the capability of systems to learn from data, predict outcomes, and make informed decisions without explicit programming. The integration of ML with IoT has unlocked a vast of opportunities, automating tasks traditionally requiring human intervention and offering more insightful and predictive analytics.

The fusion of IoT with ML presents a transformative potential for developing intelligent solutions across diverse domains, including predictive maintenance, anomaly detection, and smart transportation. This integration, however, introduces a critical challenge for developers: the selection of the appropriate development approach for ML-based features within IoT solutions. The dilemma stems from a choice between leveraging traditional, high-level programming languages and libraries that simplify ML model development and opting for more specialized, low-level programming for nuanced control and customization. This decision is pivotal, impacting not only the feasibility and performance of the solution on the intended hardware but also its energy efficiency, execution time, and overall carbon footprint.

Despite the clear benefits of integrating ML into IoT-based solutions, developers face significant hurdles in selecting the most suitable development approach for ML models. This challenge is compounded by the need to balance ease of development, performance requirements, hardware compatibility, and sustainability concerns. There is a conspicuous gap in guidance for developers navigating these complex considerations, leading to potential inefficiencies and suboptimal solutions.

To address this challenge, we have proposed the development of a decision support system designed to aid developers in selecting the most appropriate approach for developing ML models within IoT-based solutions. This system will be grounded in an exhaustive comparison of available solutions, taking into account various problem-specific and environmental factors. Through a comprehensive experimental framework, we have assessed different ML development libraries across multiple dimensions, including performance metrics, execution time, memory utilization, power consumption, CPU temperature, and carbon footprint. This approach will enable the identification of trade-offs and optimal paths for different IoT-ML application scenarios.

Our research contributes to the field of IoT and Machine Learning integration in several significant ways:

Comparative Analysis of ML Development Libraries: We have provided an extensive comparative analysis between high-level and low-level programming libraries for developing ML models, catering to a range of IoT machine learning tasks. This analysis leverages two distinct datasets, each aligned with a common IoT ML image classification objective.

Green Carbon Footprint Calculation Algorithm: A novel algorithm has been introduced to calculate the carbon footprint associated with the execution of ML training codes. This algorithm incorporates a comprehensive set of parameters, including execution time, memory utilization, power consumption, and CPU temperature.

Decision Support System: Based on the exhaustive experimental findings, a decision support system has been synthesized, presenting key insights and recommendations for developers. This system aids in navigating the complex landscape of IoT-ML integration, highlighting optimal development approaches that balance performance, hardware compatibility, and environmental sustainability.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. First, the existing literature related to our work and their limitations are discussed in

Section 2. Then, our detailed methodology is outlined which includes the selection of datasets and machine learning models in

Section 3. Subsequently, the experimental setup configuration and evaluation metrics are briefed. Results of the experiments are interpreted in

Section 4. Two case studies are then compared side by side against the green carbon footprint algorithm we have proposed in

Section 5. Finally, we have explored potential future research in

Section 6 and we have elaborated on the final scope of our work in

Section 7.

2. Literature Review

The Raspberry Pi has revolutionized single-board computing because of its affordability and versatility. The selection of programming language on the device considerably affects elements like execution speed, energy efficiency, and code complexity. This literature assessment explores the studies landscape concerning Raspberry Pi and programming languages, inspecting how language choice affects performance, complexity, and energy consumption. Early studies laid the foundation for comparing the performance of compiled and translated languages. Compiled languages, such as C and C++, exhibit better execution speeds due to direct interpretation in machine code, while interpreted languages, such as Python, rely on runtime interpretation, and slower performance occurs for tasks that require more computation [

1,

2,

3]. Furthermore, the analysis of image classification methods revealed the computational efficiency of the C# implementation on Python, albeit at a higher computational cost [

2]. Beyond the compiled vs. interpreted arguments, recent research has delved into the performance differences between specific programming languages. Comparative analyses consistently showcase the faster execution speed of C++ over Python, attributing this difference to C++’s lower-level nature [

4]. Empirical comparisons between various languages emphasize scripting languages’ development speed advantage, albeit with increased memory consumption [

5]. Attempts to analyze energy consumption in programming languages find that compiled languages are more energy efficient than interpreted languages. Source code optimization emerges as an important factor affecting energy efficiency and performance [

6]. The complexity of development is another factor to consider. Python appears as the simplest and easiest language, while C++ and Java are considered the most complex [

7]. Optimization of energy efficiency and performance is important when it is a resource-constrained environment like IoT devices and microcontrollers. Edge machine learning techniques and advances in tinyML computer vision applications provide promising ways to achieve this goal [

8,

9]. Studies focusing on Raspberry Pi applications underscore the importance of more efficient and effective code for these devices[

10,

11,

12]. Manual optimization methods are often more effective than automated compiler optimization, emphasizing the need for customized methods [

13]. For performance-critical tasks, studies suggest that compiled languages like C or C++ might be preferable. Moreover, using optimization techniques and energy-efficient languages are recommended when energy consumption is a concern [

14]. Performance analysis in microcontrollers reveals the capabilities of programming languages for data processing tasks. C and C++ has better performance than other languages, while MicroPython exhibits slower execution times, limiting its suitability for high-performance applications [

15].

Noticeable trends in the literature emphasize the importance of resource-constrained environments such as IoT devices. Pre-trained models and edge machine learning techniques offer promising approaches to improve energy efficiency and reduce communication costs in these environments [

15,

16]. Furthermore, the concept of "green coding"[

17,

18] and "carbon footprint"[

19] emphasizes the need for sustainable coding practices to reduce the environmental impact of computers. This is focusing on the importance of considering energy efficiency and environmental sustainability in software development[

15,

20,

21].

Table 1 presents a gap analysis comparing existing works with the contributions of our study.

3. Methodology

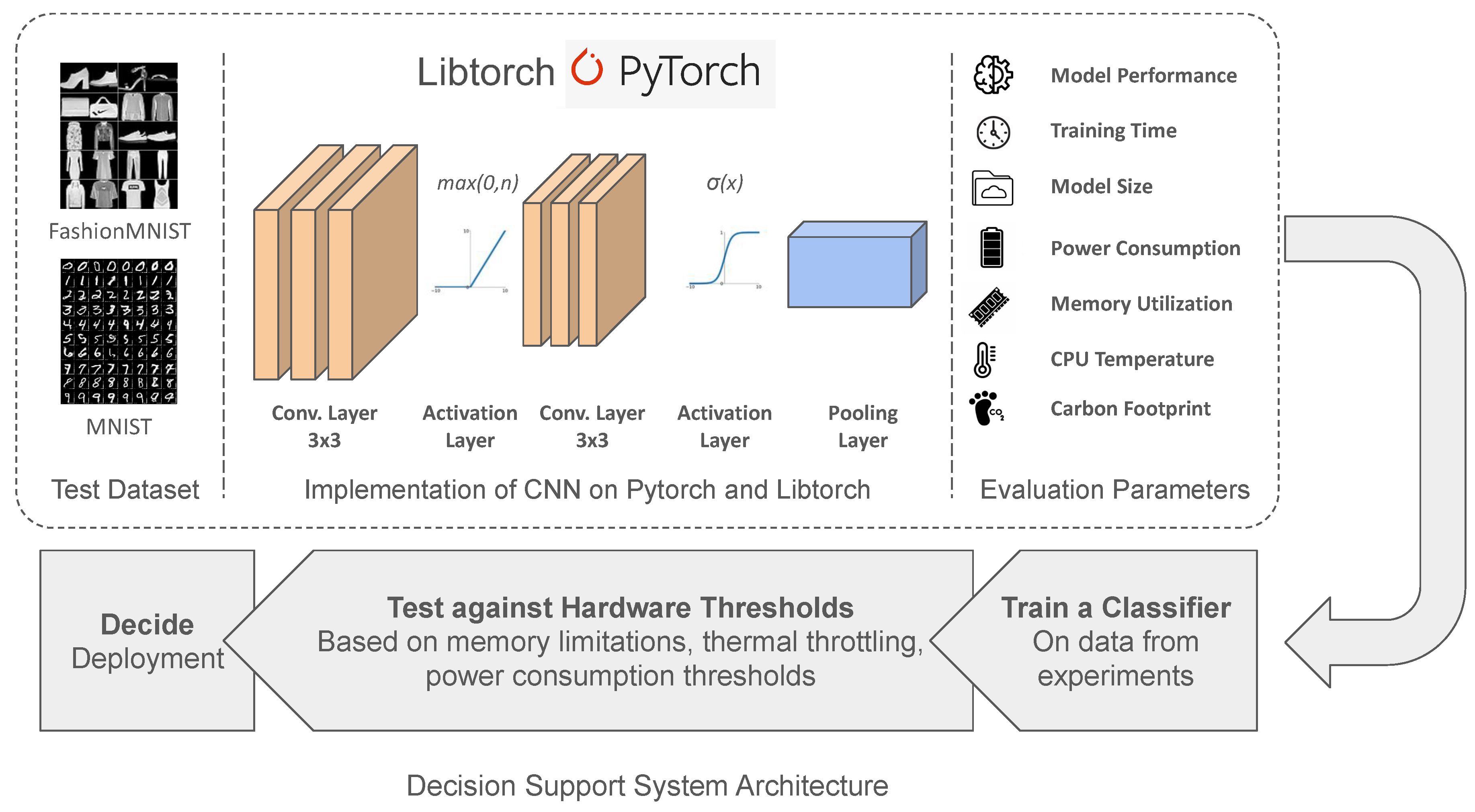

Figure 1 depicts our proposed methodology. This section outlines the methodology employed to assess the impact of ML libraries on the carbon footprint of IoT solutions. Our approach encompasses the selection of datasets and ML models, the choice of programming libraries, and the calculation of carbon footprint through a novel algorithm.

3.1. Selection of Dataset and Model

In our study, we have selected two standard benchmarking datasets that is symbolic of common tasks in IoT machine learning, pairing each with a model best suited to its characteristics for an insightful comparative analysis. we select the FashionMNIST dataset, which comprises 60,000 grayscale images of 10 fashion categories, each of size 28x28 pixels, we have utilized a Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) model. This choice was driven by the CNN’s proven capability in handling image data, particularly its effectiveness in discerning patterns and features essential for classifying different types of clothing and accessories. In addition, we also opt for the MNIST dataset which is the predecessor of the FashionMNIST dataset. It consists of 60,000 grayscale images of the english digits (i.e. from 0 to 9) having the same resolution as the FashionMNIST. The architecture of the CNN, tailored to efficiently process the varying shapes, and styles present in the FashionMNIST and the MNIST dataset, enables accurate and rapid image classification, making it an ideal match for this type of visual data common in e-commerce and fashion industry applications.

3.1.1. Convolutional Neural Network

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) are deep learning models commonly used for computer vision. They consist of layers that can detect features using a process known as convolution. It uses activation layers to bring out more relevance to these features and pooling to reduce the dimensions for faster inference.

We have used a basic convolutional neural network for both Pytorch and Libtorch to keep our experimental setup uniform. The architecture is as follows:

3.2. Selection of Programming Libraries

Python has primarily been the language of choice when it comes to machine learning, with libraries such as TensorFlow, Keras, PyTorch and scikit-learn used for its ease of use and extensive support for deep learning models. With more resource constrained devices and a shift to computation on edge devices, the overhead of the Python environment has diverted attention to lower level languages such as C, C++ and Rust.

We have chosen Python and C++ to implement the models as mentioned earlier for comparison between libraries with regards to energy efficiency. The library selected for C++ will be Libtorch, a deep learning framework that is compatible with PyTorch, with the methods and functions being similar as well as models built on PyTorch being able to be run with Libtorch. The library we have selected for Python will be PyTorch to be as close as possible with our Libtorch configuration.

3.3. Measuring Green Carbon Footprint

The Green Software foundation’s implementation of calculating carbon intensity of software[

27] is defined as follows:

Where SCI is Software Carbon Intensity, E is energy consumed, I is carbon emitted per unit of energy, M is the embodied emissions of a software system and R is the functional unit of the piece of software. This functional unit may be API calls or training runs for an ML model. Carbon emissions per kWh are a location based parameter, and can be found through reports from government agencies[

28]. We have considered the number of epochs per training session as the functional unit, and the embodied emissions of the Raspberry Pi as the standard embodied emission of a smartphone.

To evaluate the environmental impact, we have introduced an additional algorithm to calculate the green footprint of training machine learning models, beyond just carbon emissions. The algorithm considers multiple operational factors including execution time, memory utilization, power consumption, and CPU temperature. Distinct from existing methodologies, this algorithm is designed to provide a more holistic view of environmental impact by integrating these diverse metrics, thereby offering a comprehensive assessment of sustainability.

Furthermore, this algorithm is structured to enhance the ecological aspects of machine learning applications, making it substantially greener compared to conventional approaches. It encourages the adoption of more sustainable practices in the development and deployment of machine learning models by quantifying the carbon emissions and thereby enabling developers to make informed decisions aimed at reducing the ecological footprint.

|

Algorithm 1 Calculate Carbon Footprint |

-

Require:

-

Ensure:

-

-

-

-

-

▹ Define based on empirical data -

-

return

|

3.3.1. Mathematical Representation

The green carbon footprint (GCF) is calculated as follows:

where:

P = Power consumption (in kW)

T = Execution time (in hours)

= Power to Carbon Conversion Factor

M = Memory utilization (in kB)

= Memory to Carbon Conversion Factor

= Temperature Cost, a function of CPU temperature

3.4. Experimental Setup

To conduct our experiments a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B is considered as the IoT device.

Table 2 lists the specification of the specific version of the device used. A custom OS image is burnt in a 32 GB SD card and inserted in the Raspberry Pi’s storage slot. For interacting with the device we have used PuTTY; an open-source software that utilize the SSH protocol to remotely access IoT device. Experiments are conducted under controlled conditions, with each Machine Learning model trained on its respective dataset using the selected libraries. Performance metrics, execution time, memory utilization, power consumption, and CPU temperature are recorded for individual experiment.

3.5. Evaluation Metrics

The evaluation of our machine learning models encompasses a holistic approach, considering a broad spectrum of metrics to assess both traditional performance and environmental impact. This comprehensive evaluation ensures a nuanced understanding of each model’s effectiveness and its sustainability within IoT applications.

Performance Metrics on Test Data: The evaluation metrics for model performance on test data include accuracy, F1-score, precision, and recall. These metrics provide a multifaceted view of the model’s effectiveness.

Accuracy: Defined as the ratio of correctly predicted observations to the total observations.

Precision: The ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to the total predicted positive observations. It reflects the model’s ability to return relevant results.

Recall (Sensitivity): The ratio of correctly predicted positive observations to the all observations in actual class - yes. It measures the model’s capability to find all relevant cases.

F1 Score: The harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. This score takes both false positives and false negatives into account, making it a better measure of the incorrectly classified cases than the Accuracy metric alone.

These performance metrics offer a comprehensive assessment of the model’s predictive accuracy and its ability to manage trade-offs between precision and recall, essential in applications where the cost of false positives differs from that of false negatives.

Computational and Environmental Impact Metrics: Additionally, the evaluation includes metrics such as execution time, memory utilization, power consumption, and CPU temperature. These metrics are pivotal for assessing the model’s computational efficiency, resource demands, and environmental impact, guiding towards sustainable ML deployment in IoT systems. When applicable, we have used command line utilities to remain programming language agnostic.

Execution Time: Measures the total time taken by the machine learning model to complete its training process. A shorter execution time is generally preferable, indicating an efficient model capable of learning quickly, which is crucial in time-sensitive or resource-limited environments. In Python, the execution time can be accurately measured using the time library.

Memory Utilization: Reflects the amount of memory required by the machine learning models during their execution. Effective memory management is critical, especially in environments with limited memory resources such as IoT devices. The command line utility free is used to monitor and optimize memory consumption during model training.

Power Consumption: Indicates the electrical power used by the computing device while running the machine learning model. Energy efficiency is paramount in scenarios where power availability is constrained, such as mobile or embedded systems. Power consumption is typically measured using a USB power meter or multimeter to track the voltage and current draw of a device, like a Raspberry Pi, thus allowing calculation of power usage in watts. Power draw can be estimated using powertop. The command also logs CPU usage.

CPU Temperature: Monitoring CPU temperature is essential for maintaining system stability and efficiency. High temperatures may suggest excessive computational demand or inadequate cooling, potentially leading to hardware throttling or failure. Temperature can be tracked using the vcgencmd utility on the device, which allows real-time temperature monitoring. This will allow us critical data for managing thermal conditions during intensive computational tasks.

3.6. Decision Support System Framework

Based on the experimental results we have proposed a theoretical decision support system for the developers. It can aid in choosing a suitable approach for addressing a specific problem set. First of all, we have taken the type of data associated with the target scenario under consideration which can be image data or other types of data. Then, our focus is shifted to the minimum threshold for certain parameters that are dependent on the problem at hand. Some of the parameters are hardware specific like CPU utilization, CPU and memory consumption. Other parameters include model-specific parameters like model accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-Score.

This structured methodology provides a comprehensive framework for assessing the environmental impact of ML models in IoT applications, offering insights into the trade-offs between ease of development, performance, and sustainability.

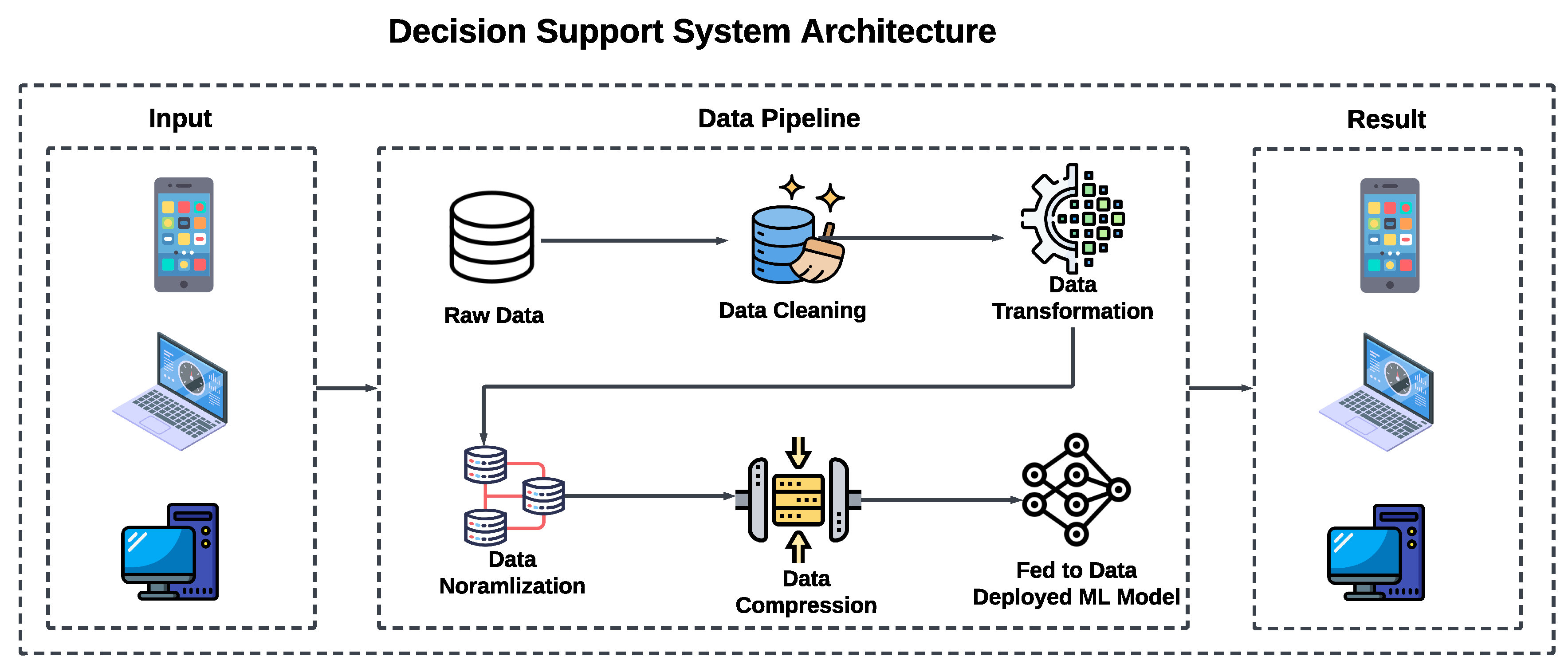

The pipeline in the decision support system follows a sequential process to handle data from its raw form to the deployment of a machine learning model. This process is detailed below:

Raw Data Collection: Gathering unprocessed data from various sources relevant to the application domain.

Data Transformation: Applying transformations to the raw data to convert it into a more manageable or suitable format for analysis.

Data Normalization: Normalizing data to ensure that the model is not biased towards variables with larger scales.

Data Cleaning: Removing or correcting data anomalies, missing values, and outliers to improve data quality.

Data Compression: Reducing the size of the data through various compression techniques to enhance storage efficiency and speed up processing.

Feeding Data to Model: Inputting the processed data into the machine learning model for training.

Model Deployment: Deploying the trained model into a real-world environment where it can provide insights or make decisions based on new data.

This comprehensive pipeline not only optimizes the data handling and model training processes but also ensures that the deployed models are robust, efficient, and suitable for the intended IoT applications.

Figure 2 shows the architecture for our Decision Support System.

4. Result Analysis

In this section, we have analyzed our findings from two distinct perspectives. First of all, the model’s performance and report of the traditional evaluation metrics namely accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-Score is presented. We have compared these metrics between the ML libraries that have been in our experimented. Secondly, the various metrics associated with the computational and environmental impact of the model like resource consumption and the model’s carbon footprint are measured. All of the model training are done for 10 epochs to conduct a fair comparison. Finally, validate our novel Green Carbon Footprint Algorithm.

4.1. Training on FashionMNIST

Table 3 lists the traditional performance metrics for training an image classifier on the FashionMNIST dataset using the PyTorch and Libtorch libraries.

Analyzing the performance of PyTorch and Libtorch on the FashionMNIST dataset reveals distinct advantages for each framework. Both PyTorch and Libtorch performed in a similar manner in terms of model’s prediction capability. Nonetheless, Libtorch had slightly better results while taking shorter time for training the model.

Moreover, Libtorch showcases advantages in training efficiency and resource management. It completes training faster by approximately 7% and utilizes less memory and power, which could be crucial in resource-constrained or energy-sensitive environments. Additionally, Libtorch operates at a slightly lower CPU temperature, suggesting more efficient resource use and potentially lower environmental impact. Further comparisons may be drawn with

Table 3 and

Table 4, where Libtorch has far more optimised and uniform memory utilisation and Pytorch slightly more sporadic in CPU calls over time.

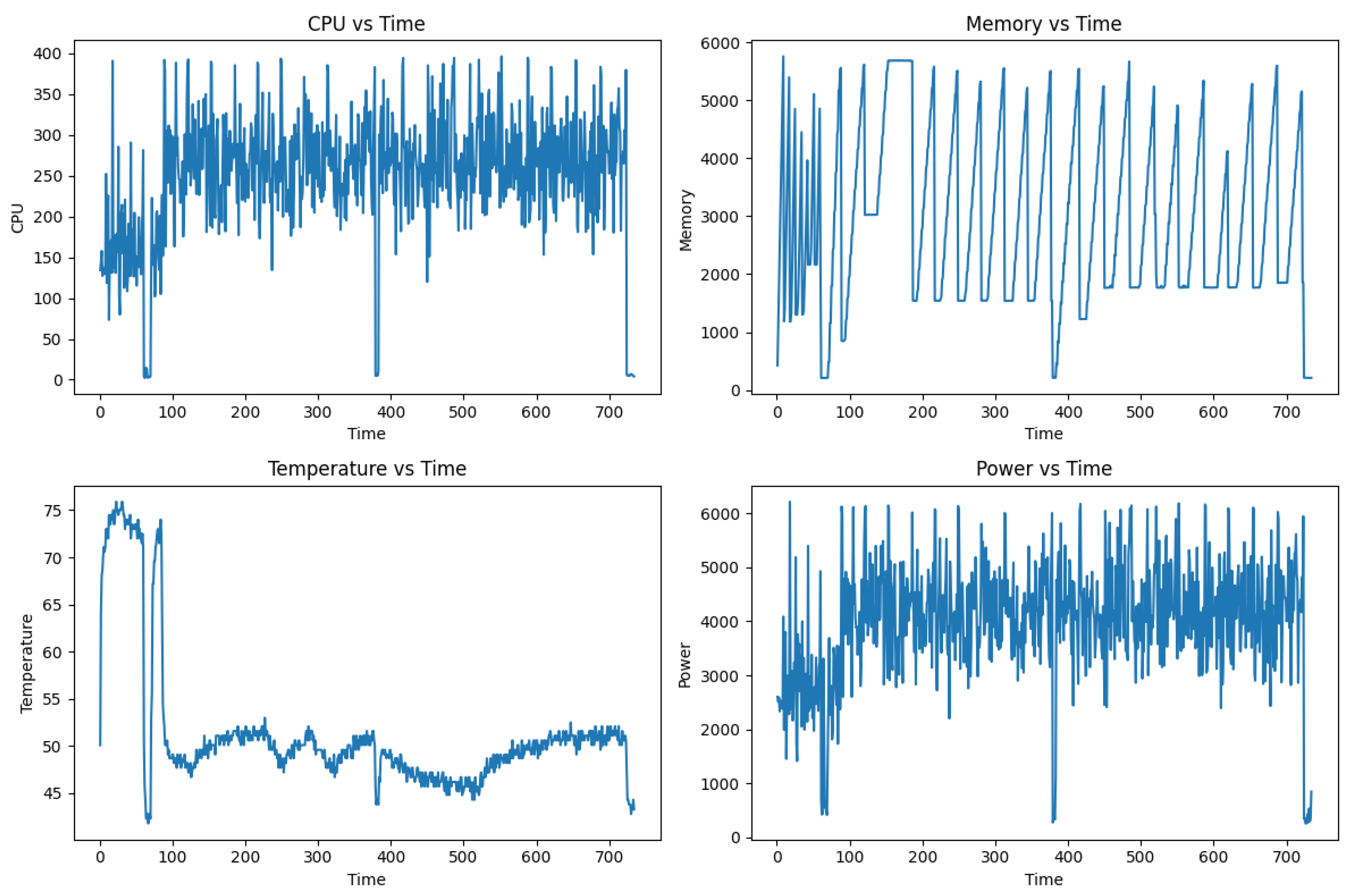

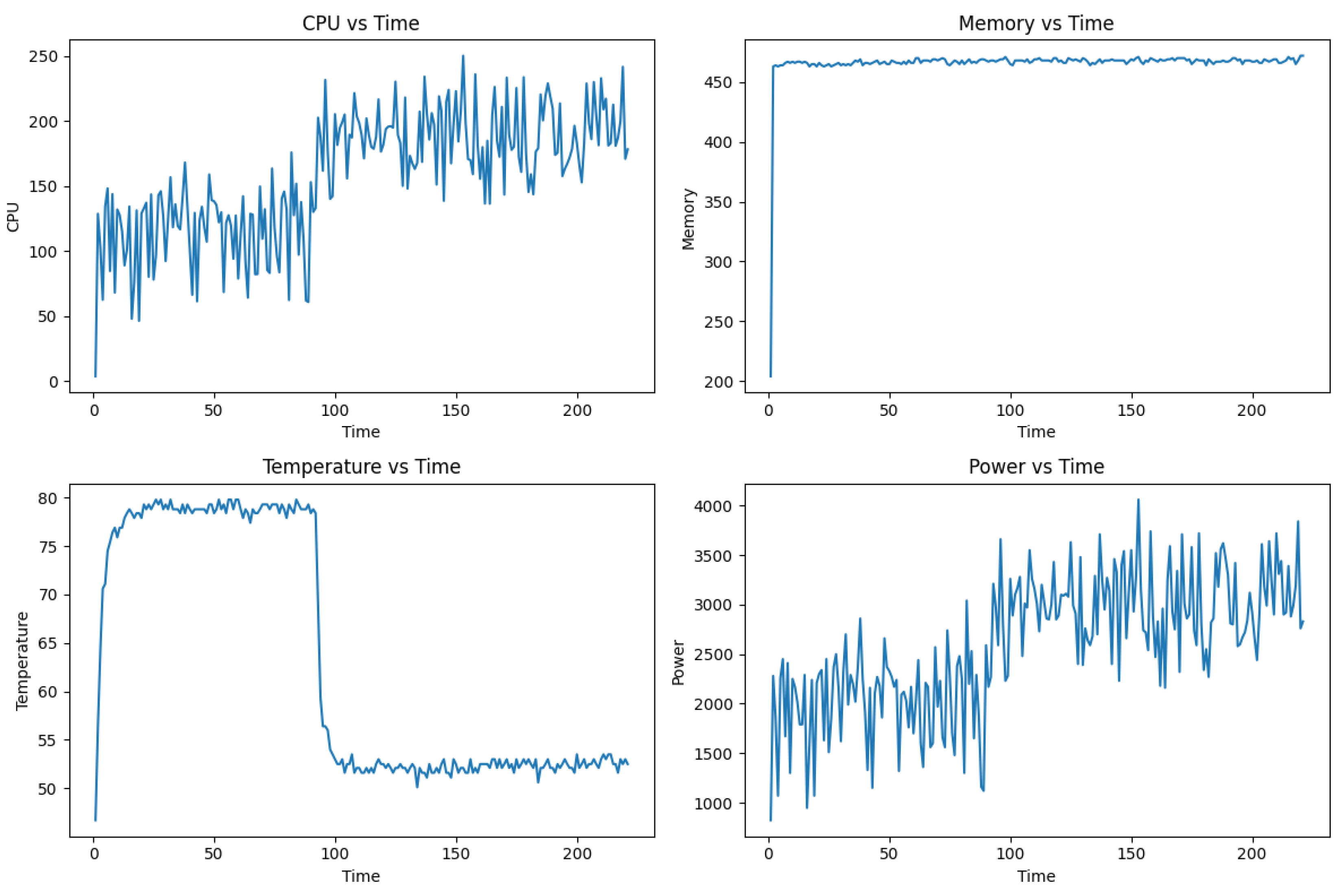

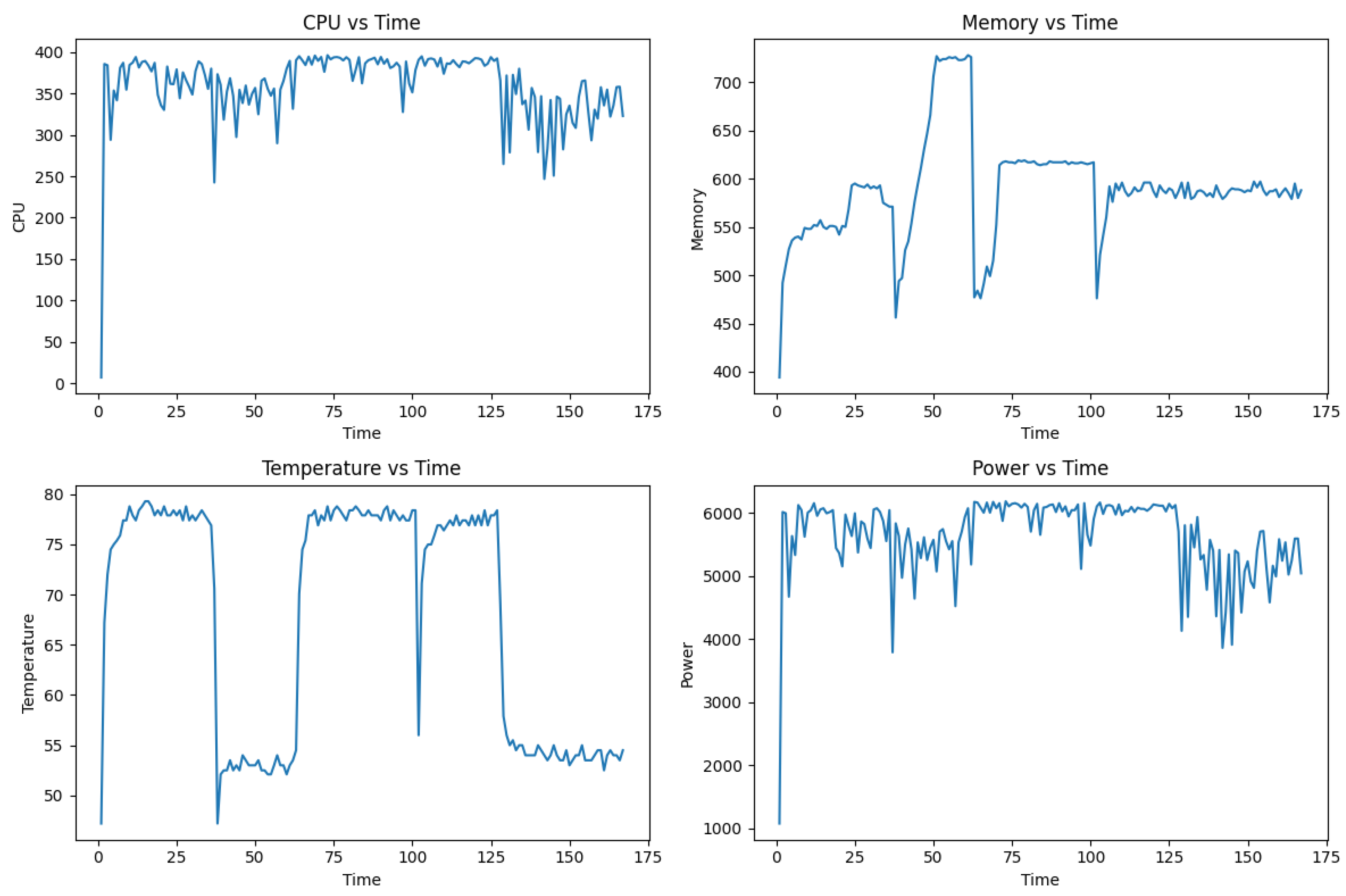

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 depicts the continuous tracking of the external factors for the duration of training the model on the FashionMNIST dataset. The metrics are reported every 60 seconds in a CSV file and then plotted using the

matplotlib library in Python. Firstly, comparing the CPU usage it is apparent that PyTorch uses more CPU computation resource consistently while Libtorch’s CPU usage remain low for the first half time and show a slight increase for the rest of the training period which is still lower than that of PyTorch. In terms of memory consumption profile, there is a drastic difference between the two libraries. The PyTorch implementation shows a sustaining fluctuation and an overall higher memory consumption. In comparison the Litorch model training shows an almost linear consumption of memory which flattens at around 460 megabytes. For the internal temperature of the CPU, PyTorch surprisingly is lower for the most of the time expect for a sharp increase right after the initial execution of the training session. Meanwhile, the CPU temperature stays around 80 degree Celsius for the half period of the training and then significantly decreases to the ambient operating temperature of the device. Finally, the power consumption profile for both the PyTorch and Libtorch shows a direct correlation with the respective CPU utilization profile for each library.

4.2. Training on MNIST dataset

Table 4 lists the traditional performance metrics for training an image classifier on the MNIST dataset using the PyTorch and Libtorch libraries.

Training on the MNIST dataset using PyTorch and Libtorch takes less time compared to the FashionMNIST experiments mainly because of the simplicity of this dataset. In terms of the models performance Libtorch outperforms PyTorch by a small magnitude. Furthermore, the device memory consumption and average temperature during the training is lower for Libtorch. However, Libtorch require slightly longer to train.

In summary, while PyTorch provides an easier approach for developing as it abstract most of the inner logic from the developers, Libtorch may be preferable for scenarios prioritizing more reliable performance and sustainability due to its lower resource consumption and energy usage. As evidenced by Tables

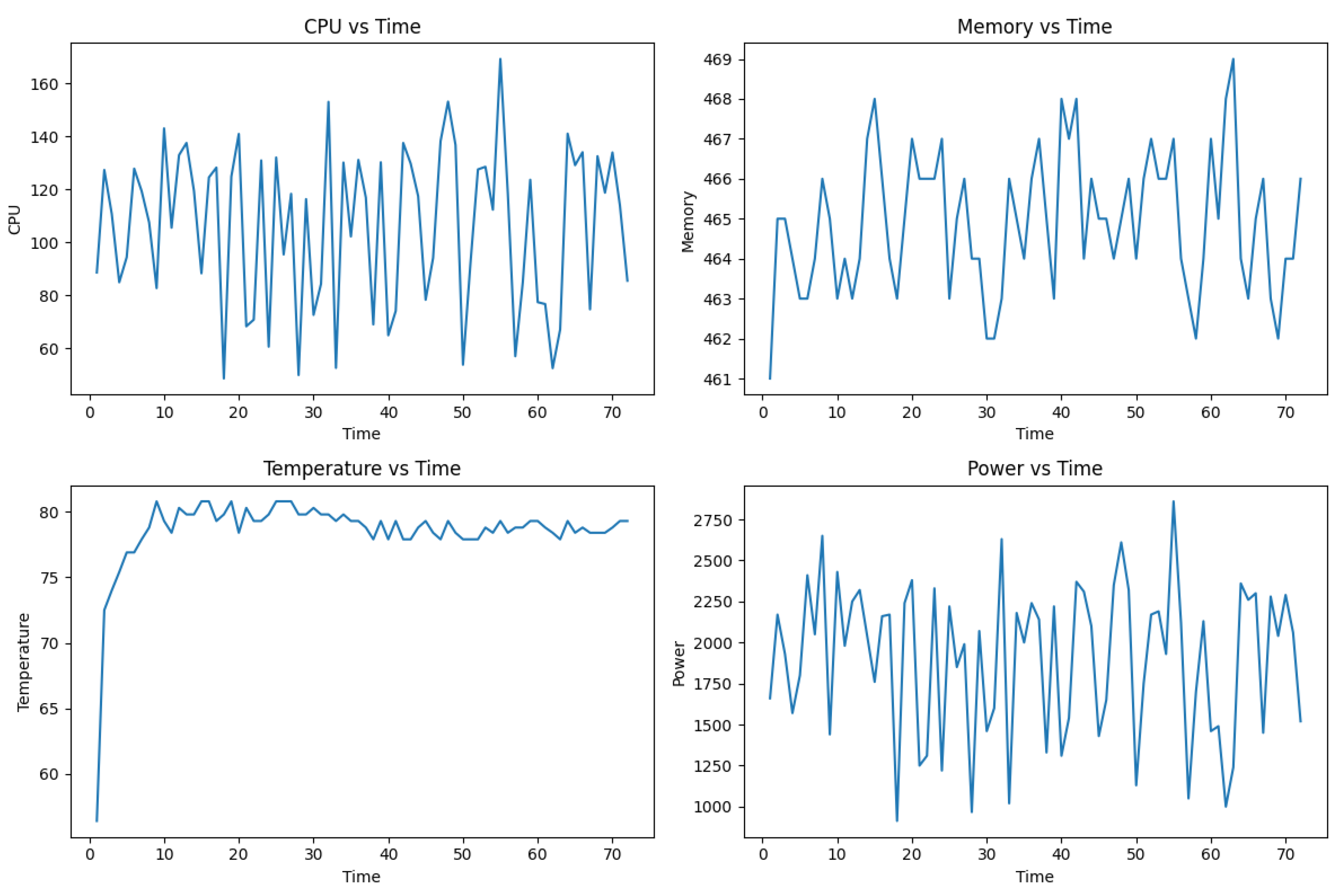

Figure 5 and

Figure 6, running code on Python significantly increases CPU and RAM utilisation, directly effecting power draw in the process. A smaller power footprint despite the longer duration for training means there may be more avenues for lowering the carbon footprint. Nevertheless, Libtorch implementation is not as widely-adapted as Pytorch and requires handling more complex coding compared to PyTorch. The choice between these frameworks would depend on the specific trade-offs between performance accuracy and operational efficiency relevant to the deployment context.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 highlight the differences of external metrics over time during model training on the MNIST dataset. Time is measured in minutes, CPU utilisation is based on number of calls at that timeframe. We can see a more uniform distribution for PyTorch, but overall lower peaks for LibTorch. Memory is measured in megabytes, where similarly LibTorch uses less memory compared to PyTorch. This is due to the overhead from the Python environment. Both temperature curves peak at around 80

oC, beyond the normal operating limit for the Raspberry Pi 4. Power consumption, measured in milliwatts, is directly related to and estimated from CPU calls, therefore we see a smaller overall footprint from

Figure 6.

4.3. Validation of the Green Carbon Footprint Algorithm

In developing the Green Carbon Footprint Calculation algorithm, one of the critical steps involves fine-tuning the conversion factors that translate the operational metrics (power consumption, memory utilization, and CPU temperature) into their equivalent carbon emissions. This process is essential not only for achieving accuracy in the calculated footprint but also for ensuring that the algorithm reflects true environmental impacts, allowing for effective sustainability assessments in machine learning operations.

4.3.1. Determining Conversion Factors

The conversion factors, namely Power to Carbon Conversion Factor (PGCF), Memory to Carbon Conversion Factor (MGCF), and a factor for the Temperature Cost (based on CPU temperature), are derived from a combination of industry standards, published research, and empirical data specific to the computational resources being assessed. This multi-source approach ensures a robust basis for the conversions, reflecting variations in energy sources, efficiency of memory use, and the thermal characteristics of computing equipment.

Power to Carbon Conversion Factor (PGCF): This factor converts the energy consumed (in kWh) by the system into grams of CO2 equivalent. It is influenced by the regional energy mix and the efficiency of the power supply. To establish this factor, data from local utility companies and renewable energy contributions are considered.

Memory to Carbon Conversion Factor (MGCF): Memory utilization is converted to carbon emissions based on the energy cost of memory operations and the production impact of the memory hardware. This factor accounts for the embodied carbon of producing and maintaining memory hardware, amortized over its operational lifespan.

Temperature Cost Conversion: The CPU temperature directly affects the system’s energy efficiency and cooling requirements. A higher temperature indicates more energy-intensive cooling, translating to higher emissions. A mathematical model is developed to relate CPU temperature to carbon output, using empirical data from thermal performance studies.

4.3.2. Empirical Validation and Adjustments

To validate these factors, a series of controlled experiments and simulations are conducted. These tests involve running typical machine learning models under varied conditions to capture real-time data on power consumption, memory usage, and CPU temperatures. The resulting emissions are then calculated using the initial set of conversion factors.

4.3.3. Finalization and Implementation

Once the conversion factors are optimized and validated, they are finalized and implemented into the algorithm. Regular updates and recalibrations are scheduled based on new data and changes in technology or energy metrics, ensuring the algorithm remains accurate over time and reflective of current conditions.

This detailed approach to optimizing conversion factors underpins the reliability and ecological sensitivity of the Green Carbon Footprint Calculation algorithm, making it a vital tool for assessing the environmental impact of machine learning operations.

Using the image classification performance metrics obtained from the PyTorch and Libtorch libraries, we have validated the Green Carbon Footprint Algorithm (GCF). For this validation, we have employed the recorded training time, model size, and total power consumption, alongside a predefined temperature cost based on CPU temperature.

5. Case Studies

The validity of our algorithm from

Section 3.3.1 can be analysed from our experiemental setup. We use the data collected from

Table 3 and

Table 4 to compare the footprint of PyTorch against LibTorch. We have used an example of PyTorch trained on FashionMNIST to show the calculations. The model sizes will be used in our calculations, and are as follows:

5.1. Case Study 1: FashionMNIST with PyTorch

Using a convolutional neural network model trained on FashionMNIST based on our results from PyTorch in

Table 3 and

Figure 3, the GCF algorithm can be formulated. We have first explored the temperature cost calculation and the carbon factor adjustment for memory and power. These values have been adjusted based on the Raspberry Pi 4 and importance of factors.

5.1.1. Temperature Cost Calculation

Given the CPU temperature of

, the temperature cost (TC) is calculated using a preliminary empirical formula:

The weight of

can be adjusted based on the importance of a low thermal profile.

5.1.2. Factor Adjustment

Initial conversion factors were adjusted to align the GCF within the target range of 6 to 8 grams of CO2 equivalent. This range is calculated using the standard formula for calculating carbon footprints [

29], which is commonly employed in environmental impact assessments to ensure consistency with internationally recognized emission estimation methodologies. The factors set are:

These factors were found to work with the Raspberry Pi 4, and further adjustment will be required for other hardware.

5.1.3. GCF Calculation

Using the adjusted factors, the GCF for the training process is calculated as follows:

Since the resulting value of 10.9323 units is near our target, it confirms the algorithm’s environmental sensitivity and precision.

5.2. Case Study 2: FashionMNIST with LibTorch

The same architecture for a convolutional neural network was used within LibTorch, the underlying binary distribution for PyTorch. Being implemented in a low-level language like C++, a smaller footprint can be observed, as evidenced by the values from

Table 3 and

Figure 4. Due to Python’s reliance on a virtual environment and C++ being more inline with device archtiecture, we have seen a relatively significant difference in training time and power consumption. Furthermore, the temperature and model size on LibTorch were lower, so a smaller GCF value should be expected.

We can similarly find the factors for LibTorch, using the same conversion factors from

Section 5.1.2.

The GCF calculation will be as follows:

Repeating these steps for LibTorch model trained on FashionMNIST, we get a resulting GCF of 9.1517 units. Since the resulting GCF of 10.932355 units is higher than the corresponding value from LibTorch, it has a lower carbon footprint. Given the factors of temperature, time taken and memory space being lower, the GCF algorithm can give an overall idea of the footprint of a machine learning model.

This validation confirms the practical application of the Green Carbon Footprint Algorithm, underlining its sensitivity and precision in reflecting real-world operational carbon footprints of ML training processes. Continuous adjustments and validations are essential for maintaining the algorithm’s alignment with evolving environmental standards and operational practices.

6. Limitations and Future Works

Our future work will focus on expanding the scope of our decision support system to include additional programming libraries and platforms, thereby enhancing its utility and relevance. In addition, conducting experiments with other types of data like text, audio and structured data as used in traditional machine learning may provide further insights regarding the utility of shifting towards low-level ML libraries. We have also planned to integrate real-time data tracking and analysis features to dynamically assess the environmental impact of ML operations. This could enable more adaptive and responsive ML development practices.

The Raspberry Pi 4 is a widely supported device, but it may not be indicative of all scenarios of deployment of deep learning models. Other resource constrained devices such as the Jetson Nano and Arduino Nano BLE are lower profile compared to the Raspberry Pi, and finding limitations on those devices may yield fruitful results. Furthermore, deployed settings may have bottlenecks in communication and data transmission, not from CPU usage or time taken in training. Research in a realistic network setting is another limitation of this work.

Furthermore, there are other machine learning libraries that can be used for comparisons. On the higher end, Python has libraries in TensorFlow (particularly TensorFlow-Lite) that have similar possibilities for model training; and on the lower end there are libraries such as Candle developed by HuggingFace. Exploring more machine learning libraries on resource constrained devices is another avenue for future work.

By continually updating our framework to reflect the latest advancements in technology and sustainability metrics, our aim is to contribute significantly to the reduction of the ecological footprint of machine learning globally.

7. Conclusion

In conclusion, our research provides a comprehensive analysis of the environmental implications of selecting between high-level and low-level programming libraries in IoT machine learning implementations. While the high-level programming library has proven to be more developer friendly by abstracting most of the inner logic that are close to hardware, the low-level libraries allow for more custom build of the compiled program for training the machine learning model. Hence, both approaches require sacrificing either the time required to develop if low-level library is used or the environmental surplus if the high-level library is used. By developing a novel algorithm to quantify the carbon footprint of training ML models, we have offered a practical tool for developers to make more informed decisions that prioritize sustainability alongside performance and ease of use. The comparative study between libraries like PyTorch and Libtorch sheds light on the nuanced trade-offs involved in library selection, influencing both computational efficiency and environmental impact.

Acknowledgments

Funded by Institute for Advanced Research Publication Grant of United International University, Ref. No.: IAR-2024-Pub-032

References

- Rysak, P. Comparative analysis of code execution time by C and Python based on selected algorithms. Journal of Computer Sciences Institute 2023, 26, 93–99. [CrossRef]

- Salihu, B.; Tafa, Z. On Computational Performances of the Actual Image Classification Methods in C# and Python. 2020 9th Mediterranean Conference on Embedded Computing (MECO). IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–5.

- de la Fraga, L.G.; Tlelo-Cuautle, E.; Azucena, A.D.P. On the execution time of a computational intensive application in scripting languages. 2017 5th International Conference in Software Engineering Research and Innovation (CONISOFT). IEEE, 2017, pp. 149–152.

- Zehra, F.; Javed, M.; Khan, D.; Pasha, M. Comparative Analysis of C++ and Python in Terms of Memory and Time. 2020. Preprints.[Google Scholar] 2020.

- Prechelt, L. An empirical comparison of c, c++, java, perl, python, rexx and tcl. IEEE Computer 2000, 33, 23–29. [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, S.; Kechagia, M.; Spinellis, D. Analyzing programming languages’ energy consumption: An empirical study. Proceedings of the 21st Pan-Hellenic Conference on Informatics, 2017, pp. 1–6.

- Onyango, K.A.; Mariga, G.W. Comparative Analysis on the Evaluation of the Complexity of C, C++, Java, PHP and Python Programming Languages based on Halstead Software Science 2023.

- Mengistu, D.; Frisk, F. Edge machine learning for energy efficiency of resource constrained IoT devices. SPWID 2019: The Fifth International Conference on Smart Portable, Wearable, Implantable and Disabilityoriented Devices and Systems, 2019, pp. 9–14.

- Lu, Q.; Murmann, B. Enhancing the energy efficiency and robustness of TinyML computer vision using coarsely-quantized log-gradient input images. ACM Transactions on Embedded Computing Systems 2023. [CrossRef]

- Blum, R.; Bresnahan, C. Python Programming for Raspberry Pi.

- Kesrouani, K.; Kanso, H.; Noureddine, A. A preliminary study of the energy impact of software in raspberry pi devices. 2020 IEEE 29th International Conference on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises (WETICE). IEEE, 2020, pp. 231–234.

- Ghael, H.D.; Solanki, L.; Sahu, G. A review paper on raspberry pi and its applications. International Journal of Advances in Engineering and Management (IJAEM) 2020, 2, 4.

- Corral-García, J.; González-Sánchez, J.L.; Pérez-Toledano, M.Á. Evaluation of strategies for the development of efficient code for Raspberry Pi devices. Sensors 2018, 18, 4066. [CrossRef]

- Abdulkareem, S.A.; Abboud, A.J. Evaluating python, c++, javascript and java programming languages based on software complexity calculator (halstead metrics). IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. IOP Publishing, 2021, Vol. 1076, p. 012046.

- Plauska, I.; Liutkevičius, A.; Janavičiūtė, A. Performance evaluation of c/c++, micropython, rust and tinygo programming languages on esp32 microcontroller. Electronics 2022, 12, 143. [CrossRef]

- Besimi, N.; Çiço, B.; Besimi, A.; Shehu, V. Using distributed raspberry PIs to enable low-cost energy-efficient machine learning algorithms for scientific articles recommendation. Microprocessors and Microsystems 2020, 78, 103252. [CrossRef]

- Lannelongue, L.; Grealey, J.; Inouye, M. Green algorithms: quantifying the carbon footprint of computation. Advanced science 2021, 8, 2100707. [CrossRef]

- Herelius, S. Green coding: Can we make our carbon footprint smaller through coding?, 2022.

- Pandey, D.; Agrawal, M.; Pandey, J.S. Carbon footprint: current methods of estimation. Environmental monitoring and assessment 2011, 178, 135–160. [CrossRef]

- Vieira, G.; Barbosa, J.; Leitão, P.; Sakurada, L. Low-cost industrial controller based on the raspberry pi platform. 2020 IEEE international conference on industrial technology (ICIT). IEEE, 2020, pp. 292–297.

- Abdulsalam, S.; Lakomski, D.; Gu, Q.; Jin, T.; Zong, Z. Program energy efficiency: The impact of language, compiler and implementation choices. International Green Computing Conference. IEEE, 2014, pp. 1–6.

- Shoaib, M.; Venkataramani, S.; Hua, X.S.; Liu, J.; Li, J. Exploiting on-device image classification for energy efficiency in ambient-aware systems. Mobile Cloud Visual Media Computing: From Interaction to Service 2015, pp. 167–199.

- Benavente-Peces, C.; Ibadah, N. Buildings energy efficiency analysis and classification using various machine learning technique classifiers. Energies 2020, 13, 3497. [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, M.U.; Chun, D.; Han, H.; Jeon, G.; Chen, K.; others. A review of the applications of artificial intelligence and big data to buildings for energy-efficiency and a comfortable indoor living environment. Energy and Buildings 2019, 202, 109383. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wang, Y.; Shi, W. {pCAMP}: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Packages on the Edges. USENIX workshop on hot topics in edge computing (HotEdge 18), 2018.

- Oliveira, L.P.; Santos, J.H.d.S.; de Almeida, E.L.; Barbosa, J.R.; da Silva, A.W.; de Azevedo, L.P.; da Silva, M.V. Deep learning library performance analysis on raspberry (IoT device). International Conference on Advanced Information Networking and Applications. Springer, 2021, pp. 383–392.

- Foundation, G.S. Software Carbon Intensity Standard, 2021.

- Climate Transparency Report 2022, 2022.

- Dodge, J.; Prewitt, T.; Tachet des Combes, R.; Odmark, E.; Schwartz, R.; Strubell, E.; Luccioni, A.S.; Smith, N.A.; DeCario, N.; Buchanan, W. Measuring the carbon intensity of ai in cloud instances. Proceedings of the 2022 ACM conference on fairness, accountability, and transparency, 2022, pp. 1877–1894.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).